This is an English translation of an article originally published in German on the T4 "euthanasia" program targeting disabled people during the Third Reich. The essay examines the contours of ableism in Germany that have allowed these killings to remain unreported and uncommemorated. The author focuses on the murder of his great-grandmother and its effects on four generations of his family. This essay provides a vital historical record as well as a model for reflecting upon and understanding the legacy of the Holocaust and the persistence of ableism.

Translator's Introduction

The history that follows honors the life of Emilie Rau and other disabled people who were killed upon the directives of Nazi Germany's medical establishment and an overwhelmingly cooperative society. Retold here in English translation, the original essay was authored, in German, by Andreas Hechler, Emilie Rau's great-grandson. It was first published in a series called Gegendiagnose. Beiträge zur radikalen Kritik an Psychologie und Psychiatrie. Psycho_Gesundheitspolitik im Kapitalismus. Vol. 1. Münster: edition assemblage. August 2015: 143-193. This original is available at: https://www.euthanasiegeschaedigte-zwangssterilisierte.de/hechler-diagnosen-von-gewicht.pdf.

In a work of painstaking scholarship, cultural theory, and personal history, Mr. Hechler focuses on the killing of his great-grandmother and its effects on four generations of his family. He illuminates these personal experiences within much larger historical and cultural contexts. Readers will learn about the T4 "euthanasia" programs in the Third Reich and the contours of ableism in post-War Germany that have allowed these killings to remain largely unreported and un-commemorated.

Although this study centers on one family's story, the essay explains the pernicious reach of ableist and "euthanistic" thinking well beyond the temporal and geographic boundaries of the Nazi era. Hechler's scrupulous research contributes vital facts and concepts to a much larger history of people with disabilities worldwide.

Among its most profound insights are those explaining why, even today, so few disabled people are recognized by name as victims of Nazi terror. Hechler shows how stigma surrounding mental illness in particular led to distancing acts and rationalization of "mercy killings" even within families. Reluctance to assert the value of life with disability contributed both to the secretive, yet systematic murder of the disabled as well as to the devastating silence surrounding their deaths. In this essay, Andreas Hechler takes up the work of re-affirming those relationships and restoring the memories of lives well worthy of living.

Many scholars and teachers of Disability Studies join Andreas Hechler in the effort to recover the suppressed history of medicalized killing. Writer Anne Finger, knowing just a bit about her friend and colleague's German-language essay, placed a call for English translations on the listserve of the Society for Disability Studies. I was not the only person to respond to that call, and it has been my honor to translate this essay. I am heartened to know how many others are prepared to translate and how many more readers are in pursuit of the knowledge such principled scholarship imparts.

Let me also recognize with appreciation my student and research assistant, Leo R. Kalkbrenner, whose good questions and reflective conversation helped this translation immeasurably. His work was supported by a grant from the Oberlin College Office of Undergraduate Research. I hope and trust that readers will find in this English version what Leo and I drew from the German: a humbling opportunity to empathize with a family suffering grave loss and injustice, a deeper understanding of the roots and legacies of state-sanctioned killing, and a sobering lesson on the costs of silence.

Diagnoses that Matter

My great-grandmother, Emilie Rau, was murdered by carbon monoxide on February 21, 1941 in the National Socialist 'euthanasia' institution at Hadamar.1

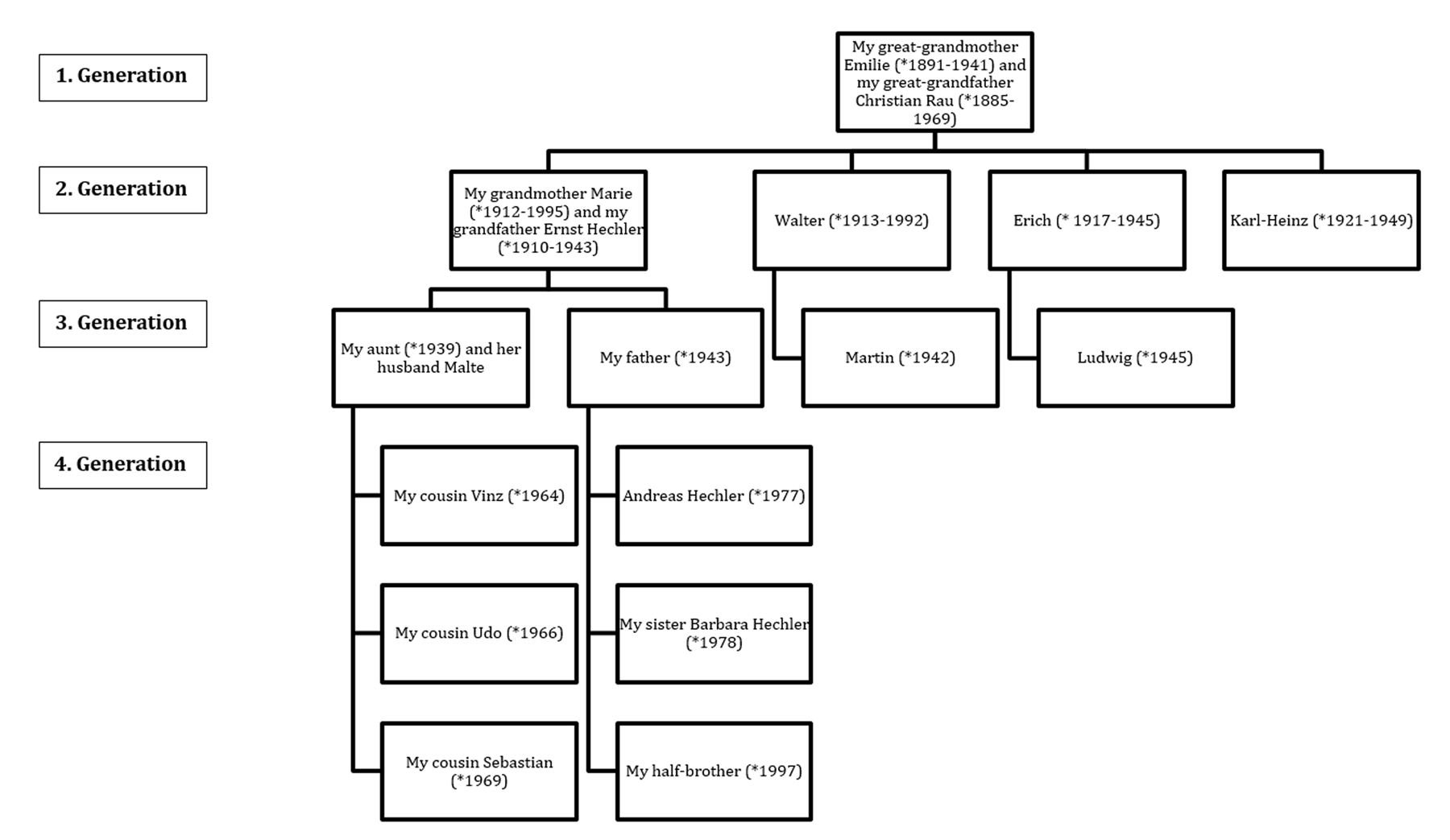

For me, the following essay is less about reconstructing the exact historical facts and more about asking what consequences her death had and still has for my family and me, including how society regarded and continues to regard her murder. I will illustrate how the diagnosis of being 'unworthy of life' has affected my family throughout at least the fourth generation. My discussion not only addresses family traditions, the handing down of information, and the consequences of each, but also examines interconnected social processes and offers a critique of enduring ableism in German society. Ableism has meant, among other things, that many families in the Federal Republic with similar family histories have decided to remain silent about their murdered relatives. I explore how victims of National Socialist 'euthanasia' have been rendered taboo in most German families, in public commemoration, and in memory politics, and their names kept secret since their murders. This situation is unthinkable for other groups who were victimized by the Nazis; for them, public commemoration by name is a key concern.

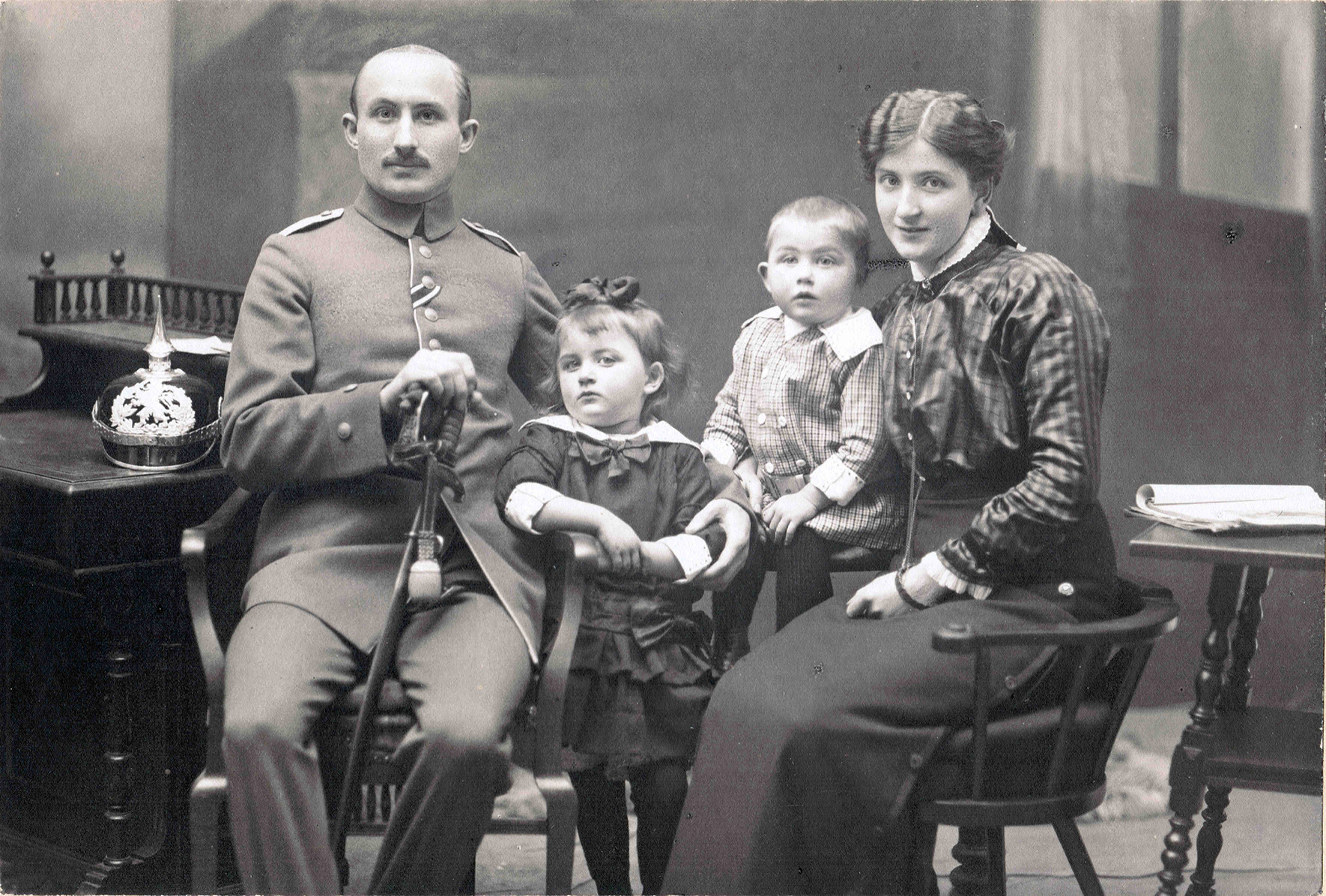

The sources for this essay are, apart from generally accessible literature, interviews from 2013 with members of the third and fourth generations of my paternal relatives (my father is the grandson of my great-grandmother); the extensive research of my grandmother (the daughter of my great-grandmother), who died in 1995; the health records of my great-grandmother; as well as official and familial writings and letters.

First I will introduce the biography of my great-grandmother, Emilie Rau, and show that she is one of the 'exemplary victims' of Nazi 'euthanasia.' My grandmother's staunch efforts contributed to this recognition, as I detail in the pages that follow. The second section, "Background about Emilie Rau and Her Murder," delves further into the life of Emilie Rau, her family, and her murder. In the next part, "Consequences for My Family," I engage with the process of handing down beliefs and knowledge within the family from the first through the fourth generation. "In the Gas Chamber" makes an example of the consequences that I experienced personally and depicts my attempt to approach the murder of my great-grandmother. The section, "Processes of Identification," delves into the politics of memory and explores who commemorates whom and who does not, including possible reasons why. Following that are discussions of "Ableism, Shame, and the Politics of Memory" in the Federal Republic of Germany, the question of naming names, and why 'shame' is not a suitable explanation either for the silence or the silencing of the victims of Nazi 'euthanasia.' The closing section, "No End," presents summarizing reflections and general observations. A chart of family relationships appears in the appendix to illustrate who is related to whom and how.

Because I often refer to ableism, my operative understanding of this term should be defined here. Ableism, writes journalist and Disability Studies scholar Rebecca Maskos in the journal arranca!, is the

term for the reduction of human beings to their—dis/abled—bodies. 'Ability' means capability and ableism the singular focus on bodily and cognitive capabilities of a person with correspondingly essentializing assessment or condemnation, each according to the characteristics of their capabilities. (Maskos 2010: 31)

She goes on to explain that the conventional (German) term for this form of thinking is not sufficient: 'hostility toward the disabled' (German: 'Behindertenfeindlichkeit') merely designates one facet of this thinking, indeed one that by no means always appears to be 'hostile' (ibid 30). Moreover the concept of 'hostility toward the disabled' neglects to problematize the structures: the step or the barrier for example can be an expression of an ableist society, but it is not an expression of 'prejudice' or 'hostility.' Ableism divides human beings into 'disabled' and 'normal' or 'healthy,' the determination of which refers foremost to capabilities. With its focus on capabilities the view of 'the disabled' turns to non-disability on the one hand and categorization processes on the other hand. Ableism affects all human beings, even those who measure up to societal norms, while the consequences for those deemed deficient are distinctly more unpleasant and ostracizing (cf. ibid.).

The spectrum of interactions between disabled people and non-disabled people can range from avoidance of contact, either ignoring or overemphasizing the disability, paternalistic care/worry, direct enmity, or even strangely emphasizing majority norms such as autonomy, efficiency, capability, and aesthetics (cf. Rommelspacher 1999: 205).

I use 'disability' as the overarching term for falling 'too far' outside of the norm of that which a body is expected to be capable of. I do not accept the differentiation between 'mentally/ intellectually ill' and 'physically disabled.' Further aspects of the concepts of 'ableism' and 'disability' will become clearer in the course of the text.

1. 'Exemplary Victim'

Emilie Rau has by now become one of the T42 'exemplary victims' in the Federal Republic. If you google 'Emilie Rau Hadamar,' you will not find a link to my great-grandmother. Shortening her last name to 'Emilie R. Hadamar' yields more results.3

In an article from the Frankfurt New Press [Frankfurter Neue Presse], written by two school students from the advanced history course at the Kurt-Schumacher School in Karben in the state of Hesse, the authors report that over 100 students from their school's graduating class toured the memorial site at Hadamar. They cite the example of Emilie R. as a T4-victim who was mentioned in a presentation for the students (cf. Weingarten/Fey 2012). The journal Information on Political Education, published by the Federal Agency for Civic Education, contains an article by the Berlin historian Michael Wildt, who cites The Fate of Emilie R. as a source text for "Murder of the Sick" (cf. Wildt 2012: 34). Thomas Lange and Gerd Steffens proceeded in exactly the same way in their sourcebook, Der Nationalsozialismus [National Socialism] (cf. Lange/Steffens 2013). The Westphalian News reports of a "special commemorative worship service" on the day of liberation from Auschwitz, at which employees and residents of the Alexianer Hospital in Münster commemorated the victims of National Socialist 'euthanasia' (cf. Kretzschmer 2008). 'Emilie R.' is mentioned as an example along with two other people murdered in Hadamar. Similarly Emilie R. is found on a private homepage where many victims of National Socialism are listed (cf. Transportliste n.d.).

'Emilie R.' is also mentioned with her biography on the homepage of the Hadamar Memorial site as the only adult non-Jewish T4-victim.4 She has her own plaque in the permanent exhibit there, which includes her photograph and significant dates from her life. She is portrayed in detail in the companion volume, Transferred to Hadamar: The Story of a Nazi 'Euthanasia' Institution, in both standard German and in simple language (cf. Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen 2002: 103ff., George/Göthling 2008: 55ff.) A citizens' initiative between 1992 and 1999 portrayed her life and her murder in the first exhibit at Pirna-Sonnenstein, which was not yet a memorial site.5 All of the quotations and articles mentioned above refer to this text, which reads:

Emilie R., born in 1891 in Alsfeld, married police secretary Christian R. in 1912. She had four children and was mentally healthy until 1931, when a state of confusion and depression surfaced. At this time, her husband was on medical leave due to a hip injury—which led to deep fears about job security and the reputation of her family. On November 30,1931, her husband brought her to the Frankfurt University Clinic for the first time, where she was diagnosed with paranoid relationship psychosis and was detained. In December she was released at the request of her husband, but was not considered to be cured. In April of 1936, Emilie R. was taken to the Frankfurt psychiatric hospital again and this time she was diagnosed with 'paranoid dementia'–Emilie R. suffered from 'delusions.' The clinic immediately proposed sterilization, despite the fact that there was no family history of mental illness and all of the children were in the best of health. Still not considered to be cured, on May 12,1936 Emilie R. was released to the State Hospital at Hadamar, where she remained for only five months. Her husband filed an application to transfer her to the denominational St. Valentinus in Kiedrich. In one of the last entries in her medical history in Hadamar, it states: "7 August, 36. Is still under the influence of her delusions. This also explains why the institution had not objected to the transfer, because Emilie R. could not be put to work. In the denominational nursing home, her relatives were mostly denied visits. Even her husband had to strive intensively for visiting rights. He was denied a walk with her to the village of Eltville on the day of their silver anniversary, because Emilie R. fell under the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring and was not sterilized. In August of 1939 she was transferred from St. Valentinus to the Eichberg institution and was brought to the Hadamar Euthanasia Center with a group transport on the 21st of February 1941. She was murdered there that same day. Her medical records were then sent to the T4 Institution Sonnenstein near Pirna and her date of death was certified as March 1, 1941. (Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen 2002: 103)

Additionally there is a 1991 British documentary by the BBC about National Socialist 'euthanasia' in which my grandmother Marie Hechler speaks about her mother, in addition to other interviews and texts.

2. My Grandmother's Diligence

We have, above all, my grandmother to thank that my great-grandmother has become so 'prominent,' 6 since she was engaged for decades in the struggle for enlightenment, recognition, and compensation for the victims of National Socialism in general and for the so-called 'forgotten victims'7 in particular. In her own words it was a matter of "restoring to those who were murdered their individual civil rights and their inalienable dignity as human beings" and "securing justice and human dignity for the forgotten groups of victims overall."

The fact that this struggle was not an easy one is made clear by her records and letters. She names various key figures who stood in her way and hindered other people who were similarly engaged. She contends that "neither today nor back then was the fight against authorities, bureaucracy, and prejudice ever easy;" complains about the "snail's pace of our public bureaucracy," and curses the Federal Republic that wants to "shirk the responsibility of paying." At the same time she encourages herself and others: "The task for all of us remains not to give up hope, even though the processing of National Socialist crimes moves so slowly."

"Mom began to research very, very early," my father remembers. "She tried to locate the doctors in Frankfurt [Main], but every avenue was always blocked off. There was even a file in the health department, but her access to it was always denied. All of the doctors who had been involved in any way up to and including Hadamar, they blocked everyone, there was simply no access. She didn't find out anything, it must have been the end of the '50s, beginning of the '60s." The Berlin historian Götz Aly describes for the 1980s how "research on euthanistic murder required considerable tenacity and investigative skills: the archives were partially closed, the files mostly unsecured and not catalogued […] From today's perspective there prevailed unimaginable conditions, mystery-mongering, incompetence, and obstreperousness" (Aly 2013: 293).

In the interview with the BBC, my grandmother explains that it "takes a long time before you can speak about it" and stop being afraid of it. That she was not the only one to feel this way was made clear by the very late establishment of the Federation of People Aggrieved by 'Euthanasia' and Forced Sterilization8 in 1987, in which she was henceforth active. There were apparently several people who had warned her earlier against speaking about her mother and the injustice towards those murder victims 'unworthy of life' and those who underwent forced sterilization. In other cases she found people who helped her "to overcome fear and paralysis. I can speak about this when I am around like-minded people, but even today I experience shocking prejudice against people who struggle with mental illness." Christine Teller "was a great spiritual help to me" she wrote about one of the publishers of the standard works on social psychiatry, To Err is Human, and she praises one of the other publishers, "Dr. Dörner,9 who encouraged me to speak up in public." She also has friendly words for Ernst Klee, who wrote the standard work on the Nazi-'Euthanasia,' "whom I knew since the Frankfurt "Euthanasia" trial from January of 1986 – May of 1987, and whom I also thank for his encouragement."

In the reconstruction, the trial in Frankfurt10 appears to have given her activities a boost, as a majority of the documents available to me come from the time of the late 1980s and early 1990s. My grandmother meticulously documented her political efforts on behalf of the victims of National Socialist psychiatry. In September of 1989 she writes: "While I was privately tracking down any trace of my poor mother in about eleven institutions and archives, I finally made a few discoveries after the end of the euthanasia trial in May of 1987. My search began in the Frankfurt city archive and ends with the letter from Dr. Kaendler from July 26, 1989."11

My grandmother followed political events closely and remained in active contact with a broad range of people and organizations. "She brought 'Meals on Wheels' to life in Bensheim, invested herself in a home for senior citizens, and was chair of Lebenshilfe,"12 my aunt reports, "and in addition to that, she invested herself with Lea Rosh13 in Berlin for the memorial to the murdered Jews and also in the effort to remove the paragraph about 'life unworthy of life' from the Basic Law." Up until her death in 1995 she was extremely active and "always at the demonstrations."

3. Background About Emilie Rau and Her Murder

Before I describe in detail how my grandmother's work affected my extended family, more discussion of Emilie Rau's life and the above-mentioned quotation about her from the exhibition catalog is warranted. Certain questions are left unaddressed in that quotation, although they are chronologically elucidated in the Hadamar exhibition and in its companion volume, namely: what are the possible reasons for Emilie's crisis? What kinds of "delusions" did she have, exactly? What was happening during visits from her husband and other relatives? Why is the diagnosis "will not be motivated to work" of the highest relevance and for what reason were the medical records after her killing sent to Pirna-Sonnenstein and the date of death falsified?

3.1 Possible Reasons for Emilie Rau's Crisis

It is at once interesting and atrocious that Emilie, because of individual, social, and institutional circumstances, veered into a crisis that was interpreted according to National Socialist ideology as biological in nature and that ultimately led to her killing. The reasons why she came into this crisis cannot be fully and definitively explained, but there are a few key points.

As mentioned above, the first instance of confusion and depression coincided with her husband's medical leave, and Emilie, a housewife with no professional education, believed that her husband could no longer support her and their four children. Added to that were two miscarriages and the circumstance that her oldest child—and at the same time, her only daughter, Marie Rau/Hechler (my grandmother)—was 19 years old in 1931 and had just completed her culminating high school exams, so it was unclear how long she would continue to live at home and help with the household.

The relationship between Emilie and Christian Rau was presumably complicated. My father explains: "My mother accused him of being part of the reason why Emilie had the psychological problems she did," and further adds, regarding Christian Rau, that he "was harsh. I believe that she [my grandmother] also said that he [Christian Rau] had beaten her [his wife, Emilie], that he was too strict, that he ranted and raged." My aunt tells almost word for word the same story about her grandfather, and that he also had fits of unfounded jealous rage. Added to the purported domestic violence that Emilie, the children, and grandchildren had to suffer was purported sexual violence, which was confirmed in the medical records. In this matter Emilie complains to a physician that "her husband even today had sexual intercourse with her" and: "The man had sex with me constantly." It is speculative whether that has a causal relationship to Emilie's crisis. It is not improbable that it at least had an impact on her. The medical records further make clear that whenever her husband "approaches her, she recoils and becomes resistant and agitated." Christian Rau is asked by the clinic in 1937 not to visit so often, because that makes his wife "very agitated and anxious." Still before her time in the various clinics, Emilie, according to my aunt, "behaved conspicuously, called the police department and shouted curses aloud." It is probably also true that Emilie once filed for divorce. The 'mania' that was directed against her husband, read in this mindset, is comprehensible and plays into the general tendency to cast female realities of life in terms of psychiatric illness and to pathologize 'normal' reactions to sexism and violence (cf. Kalkstein/Dittel 2015).

My aunt also reported that the oldest son, Walter, had severed his ties to his father, Christian Rau, holding him responsible for Emilie's crisis. My inquiry with Walter's son, Martin, Emilie Rau's grandson, partially confirms that: "Beaten? That's the first time that I'm hearing that. My father [Walter] made an allegation […] that his own father, Christian, had not advocated strongly enough for his wife. No one ever suggested that she might have been beaten."

Since my aunt, born in 1939, cannot have been aware of meeting my great-grandmother, who was murdered in 1941, she must have heard this story from her mother. My grandmother however put forth a very different hypothesis about the crisis of her mother. She expressed herself multiple times very clearly in this matter, taking it as given that this was depression linked to menopause. This question about the cause of Emilie's crisis and the enormous sense of injustice consumed my grandmother intensely.14 According to my father, my grandmother wanted "to keep the peace in the family" and therefore expressed no open criticism toward her father. Accepting the idea of menopausal depression allowed her to maintain contact with her father and to have a plausible reason for her mother's crisis.

There is another possible reason for Emilie's increasing destabilization. As noted in her medical records: "I didn't actually want to come here. I wanted to go home. The institution is too hard on me," and "I'm getting sick here and it is making me weak." Physicians note repeatedly that she asserts she is "not sick" and "insists" on "being released." Additionally, repeated notes in her records allege that she is aggressive, that she curses, and that she does not want to work. One may also infer that she was perceived to be rebellious and an 'unpleasant' patient who upset the smooth running of the psychiatric ward. One may also presume that physicians and caretakers15 had the upper hand and let her know that. This is admittedly speculative, but the overarching nature of psychiatry as a disciplining and normalizing institution is by now well known. Moreover psychiatric clinics in their history have again and again been sites that, instead of alleviating crises, instead intensify them or even cause them in the first place (cf. Foucault 1969).

3.2 Visits by Family Members

The image of Christian Rau as a battering and quick-tempered husband is somewhat mitigated or at least enlarged for me by the correspondence that I have read. Even my grandmother writes in 1982: "He loved her very much," despite the "oppressive day-to-day married life for Emilie Rau." He visited her regularly and took care of her. This is made clear, for example, in a letter to the directors of the St. Valentinus House from December 4, 1938, in which he gives detailed thought to his wife's clothing and then writes, "Furthermore I have one more request that means a lot to me. You know that my wife is pressing strongly to come home. Until now I have always upheld the story that this would happen at Christmas. Perhaps it is possible for you to move her to another room at Christmas that is sparsely occupied, so that the change alone might drive away her desperate thoughts and she would be given new hope." In addition he conveys his impression that she has been improving recently, and offers to pay more beginning next year, in the event that she can have improved living conditions.

In the years before Emilie's murder, there were real battles between Christian Rau and the various directors of the institution. His deep desire, described above, was emphatically denied, just as the desire for a walk outside of the clinic on the day of their silver anniversary, also described above, had been denied. In 1937, the medical director implored: "I would like, in the interest of your wife, to urge you to limit to the fullest extent possible your visits and those of all other relatives. It is better for your wife if she receives at most a visit every 2-3 months." Christian Rau acquiesced to this reduced schedule in the interest of his wife's recuperation, and he informed all of the relatives.

In her last card to her husband on January 26, 1941, barely one month before her murder, Emilie writes from the Eichberg sanatorium near Wiesbaden: "health wise I am still doing well, I hope that is the case for you as well." Her card allowed her family members to hope that she could soon come home again. Her husband promptly tried to receive permission for a visit. This was rejected as a matter of course. Thereupon he turned once again to the directorate of the Eichberg sanatorium. On February 24, 1941, three days after the murder of his wife—that he still did not know about at this time—he writes with a mixture of fury and astute analysis: "it is inconceivable that you will not make an exception for my wife to visit. […] After an 8-week waiting period a visit is beyond any doubt appropriate. It could be limited to a short time, in my view. But to withhold approval completely can only lead me to imagine the worst. Please consider the other family members, especially my daughter and my 3 sons, who are doing their duty for our Fatherland. […] What shall I say to my second son, who has been a soldier since the fall of 1937, who fought along in all of the battles and now has leave from the East? My wife is not without a sense of awareness […]. She is getting better again, at least to a degree that she can be at home again. I ask you, do not act more harshly than you must. Please give me an exception and approve a short visit of my wife for the first half of the month of March of this year. Heil Hitler! Chr. R."

The only response that he receives from Eichberg is the bill for the cost of medical care and the report that Emilie Rau "was transferred on February 21, 1941 upon the orders of the Defense Commissioner of the Reich." The new address is not given to the relatives; they are told that they will receive this information from the new institution. The report does indeed reach the relatives a short time later; it is news of the death of Emilie Rau.

That Emilie's husband was taking care of Emilie, just as her children were, that they visited her and wanted to have her come home are all significant factors in Emilie's murder in that she was murdered despite the care of her family. The behavior of family members was very important and was specifically factored into the T4 program by those carrying out the plans. The more isolated and lonely the patients were, the greater the danger they faced of being murdered. Many family members were not firm and clear advocates for their family members. Götz Aly estimates that 80 percent of all family members did not press the institutions for more information about where their family members were going, and also that protest was almost always successful (cf. Aly 2013). Many equivocated and were ambivalent in their posture with regard to the treatment of disabled people. This was exacerbated because of the war situation and the corresponding shortage of resources. Additionally a considerable number of parents and relatives in fact conceived of it as 'deliverance' when their disabled family members were killed. Under these conditions Emilie's husband and children unknowingly protected her, even though they were ultimately not successful.

3.3 The (In)ability to Work

What led to Emilie's assessment as 'unfit for living'? This cannot be explained with complete certainty, but there are clear indications of what would have led to it.

In October of 1939 Hitler authorized his attending physician, Karl Brandt, and the director of the Führer's counsel, Philipp Bouhler, to carry out the planning for the killing of 'life unworthy of living,' termed 'euthanasia.' Hitler pre-dated the communication to September 1, 1939, the day of the beginning of the War. Parallel to the outward declaration of war was the one directed inward (cf. Wildt 2012: fn 33). Those who wished to be the 'master race' had to optimize that race in order to be able to demonstrate and justify the desired supremacy both to the home population and abroad, the social psychologist Birgit Rommelspacher concludes (cf. Rommelspacher 1993: 7). 'Cripples' and 'idiots' have no place in the 'master race.' Mutually reinforcing practices follow from this National Socialist ideology: on the one hand is the 'building up' of the 'German Volk,' that is, putting [the Volk] in a 'higher position' and on the other hand is the 'culling' or 'expunging' [of undesirable elements] in the form of destroying 'life unworthy of living.' The program of healing and destruction consisted of simultaneously healing the 'curable' and destroying the 'terminally ill.'

Plans for a 'recovery' of the 'national community' presumed that it was inherently sick. Among the 'pathogens' were those people deemed 'racially inferior' (Jews, Slavs, Sinti and Roma, …) as well as those people classified as 'genetically inferior' (the so-called 'congenitally ill,' 'asocial,' 'criminal,' …). The Nazis pathologized and criminalized those people who were already marginalized and cast them as 'elements foreign to the community' cleared for eradication, for 'expunging.' 'Progress through annihilation' was the paradigm for the higher development of the 'German People.' This type of eugenic16 thinking was by no means new or limited to the Nazis. The difference from earlier times and from other countries is that the Nazis were more ruthless and created opportunities for scientists to apply to human beings what had been worked out decades earlier (cf. Lösch 1998; 88 n., Kater 2001: 20).

Alongside of eugenic ideology, material factors also play a significant role. Even when one was evoking 'merciful death' and 'deliverance,' the 'burden' for society was being calculated and presented in unvarnished propaganda campaigns. In the Social Darwinist 'struggle for existence' and in the hallucinated notions of 'degradation of the races' and 'degeneracy' of the 'German people,' the 'value' of the human being was computed, expressed through the sum of the revenues which a person generates minus that person's cost to society (cf. Rommelspacher 1993: 8). With the reduction of the human being to one's economic value the central criteria for the murder of disabled people was determined: no or meager productivity and the consumption of money, resources and labor.

If the inability to work was one central criterion that led a person to the gas chamber, the other was incurability (cf. Winter 1997: 472, Hamm n.d.).17 The certification by a specialist at the St. Valentinus House in Kiedrich from August 6, 1938 provided this diagnosis for Emilie Rau: "The clinical diagnosis is the paranoid form of schizophrenia, stemming from a corresponding pathological predisposition. Significant improvement for this type and duration of illness is highly unlikely." My grandmother commented in 1982 that this "cold diagnosis and prognosis of my mother's illness" served as the "basis for the subsequent euthanasia program." In addition to that were repeated entries in Emilie's medical records—"refuses again and again to engage in work"—and her statement: "Work is out of the question for me." On this point it is important to know that women's work productivity, just as women's behavior, was assessed more negatively than it was for men (c.f. Endlich et al. 2014: 96).

Unable and unwilling to work, incurable, rebellious—a clear case for the gas chamber.

3.4 Falsified Cause, Place, and Date of Death

In order to draw as little public attention and protest as possible, the 'T4 Action' was planned as a 'secret matter of the Reich' and operated by means of cover organizations and an opaque bureaucracy as an obfuscation of the murders. "Nothing was accurate: neither the place of death, nor the date of death, nor the manner of death," said my aunt, outraged, to which one must note: not even the ashes in the urn were hers; she was not cremated because of any dangers of contagion, and the doctor who signed the death certificate used an alias.

The family was informed that Emilie Rau "died unexpectedly from complications of a boil on her lip, with resulting meningeal infection." In fact the cause of death was asphyxiation from carbon monoxide gas. To erase the traces, she was immediately cremated. Since two or more corpses were always cremated together in one incinerator, Emilie Rau's ashes could not have been the only ones in 'her' urn. The falsification of the date served to keep the secret, but also prolonged the [family's] payment of medical treatment costs. This falsification secured significant profits for the Central Clearinghouse for Sanatoria and Nursing Homes, a department of the T4 program. Those paying the bills continued to pay care-giving expenses; in Emilie Rau's case, for an additional eight days: she was murdered on February 21,1941, but her death certificate shows March 1, 1941 as the date of death. In many cases the falsified dates of death amounted in contrast mostly to several weeks, as the medical historian Georg Lilienthal explains (cf. Lilienthal 2008). The dispatching of Emilie's patient records to Pirna-Sonnenstein similarly had to do with erasing tracks. Emilie came from the nearby vicinity of the killing facility, and in order to thwart investigation attempts by family members, she was officially reported to have died in a very distant facility. In this manner the system of intermediary facilities served to obscure the path of transferals of those people who were murdered—in Emilie's case, the institution at Eichberg, which was assigned to the killing facility of Hadamar.

This process was eminently effective. We may presume that many families in the Federal Republic do not know to this day that their ancestors were murdered in the National Socialist 'euthanasia.' That they possibly do not want to know is a point to which I will return. But even my grandmother, to whom it was very quickly clear that her mother had been murdered—she was already writing about "euthanasia" in 1946—only figured out the falsifications much later: "In August of 1986 during the Frankfurt Euthanasia Trials the Senior Prosecutor Eckert [said]: he recognized by the abbreviations that my mother had not been murdered in Pirna, but in Hadamar." This in turn strongly intensified her investigations and activities; she wanted to know the truth.

4. Consequences for My Family

The case of Emilie Rau looms large in my family. First and foremost are the efforts of my grandmother. In a group letter to the entire family in 1992, she wrote "Our mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother belongs to the 'forgotten' victims of Nazi crimes, which until even today have gone unexamined. Her medical history, which began in December of 1931 in the Frankfurt Psychiatric Clinic at Main-Niederrad, was only found on May 17, 1990 after searching for traces 'from below.' Her history is a mosaic stone resulting from the exhibition at Hadamar that should teach the subsequent generations. This effort 'against forgetting' is exhausting and remains a political task for the groups that have no lobby." In the "subsequent generations" in our family it has not been without consequence: "It was important to her that we all have a political awareness," said my cousin Sebastian.

To the second layer of consequences for our family belong those in the social realm, above all eugenic ideologies and ableism, which had and still have retroactive effects on us as a family. How individual family members deal with Emilie Rau varies and cannot be viewed apart from eugenic ideologies that operate on the notion that a mentally ill family member 'besmirches' an entire family. Therefore, as a result of the diagnosis of 'hereditary illness,' there were problems with marriage throughout the third generation, and there is a certain caution within the family when it comes to mental illness. I will return to these 'diagnoses that matter' in more detail in what follows. At this point it is important to me to say that a mindset that assumes that whoever is the descendent of a 'disabled person' must also somehow 'have a screw loose' is in no way outdated. The genetification18 of psychological knowledge, bound with the notion that one will never be rid of the pathologizing, contributes greatly to the taboo surrounding National Socialist 'euthanasia' victims in many families.

Figure 4. Photo: Center: Richard Listmann, Carl Listmann, and Emilie Rau (née Listmann), left: their mother (née Müller), right: their father Listmann

The third layer of consequences is clinging fast to the truth that we are still here. Again: We exist! Despite the murder of my great-grandmother, despite the eugenic ideology that 'imbeciles' continue to reproduce genetically and that this should be prevented. If my great-grandmother had not already had children, neither my family nor I would exist.

4.1 The First Generation19

On May 10, 1987, my grandmother writes on the occasion of her mother's murder: "We were paralyzed with horror and for years were fearful of further invasions of brutality into our family." Similar formulations of "shock," "horror," and "fear" pop up repeatedly in her descriptions. I am reluctant to judge the extent to which she is speaking more about herself than about her father, but it is safe to assume that at least a portion of these descriptions apply to Christian Rau. His way of dealing with the murder of his wife was, in contrast, completely different from that of his daughter: "Christian Rau said that his daughter shouldn't speak so loudly about it. He didn't want to speak about it; that could be dangerous," said my aunt. My grandmother uses words to this effect in a letter from 1982: "This sort of thing created fear and horror and paralysis deep within the families and caused psychological repression. My father, for example hid his own insecurity and fearfulness behind a rigid monument of a father, was not prepared to reconcile with his son or acknowledge his own mistakes, and considered it proper to assert his complete innocence regarding the death of his wife by writing his son out of his will." I had noted earlier that the estrangement between the first son, Walter, and his father had to do with accusations that the former made to the latter, that he had not sufficiently engaged himself in supporting his wife. Thereupon Christian Rau tried to disinherit his son.

4.2 The Second Generation

I have already written quite a lot about my grandmother Marie, the eldest child of Christian and Emilie Rau. The other three children were, as noted above, soldiers in the Wehrmacht. The youngest, Karl-Heinz, "died of severe tuberculosis after the war in 1949," according to my aunt, and the second youngest, Erich, "died in the war," according to his son Ludwig.20 The eldest son, Walter, made the murder of his mother taboo with the exception of the argument with his father.

My grandmother bore the brunt of the effects of her mother's crisis quite tangibly even during National Socialism. In 1987 she remembers, "Because of my mother's illness I wasn't able to study at the university or receive a dowry." The gravest concern of all proved to be the planned wedding with her future husband, Ernst Hechler: "We got engaged in 1937 and had to present a certificate of clearance in order to marry. For that reason, at the beginning of the year 1938 I sought out the director of the health department in Homberg, district of Kassel," Dr. H.J. Vollbrandt, whom my grandmother knew personally. "After consulting with Kiedrich, where my mother was being cared for […] he advised unconditionally that we marry although the laws of heredity health were already in effect."

Since 1935, a certificate of fitness to marry was an obligatory requirement for a marriage. The Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring forbade, as the biologist and scientific journalist Ludger Weß, writes "the marriage of the 'genetically contaminated' and the 'genetically biological inventory in the hospitals and nursing homes,' which would later form the basis for the mass extermination of psychiatric patients, was also extended for the inconspicuous relatives of the mentally ill" (Weß 1998: 32ff.). Future spouses were also examined for incurable hereditary diseases. Those wishing to marry were only given certificates of fitness to marry by the medical authorities after a successful eugenic examination and marriage counseling by the Center for Genetic and Racial Hygiene. Accordingly, the Berlin-Wilmersdorf Center for Genetic and Racial Hygiene wrote to the St. Valentinus House at Kiedrich on November 10,1938, where my great-grandmother was a patient at the time: "To clarify a genetic biological matter we ask for the release of the local medical record […] of Mrs. Elise Emilie Rau." My grandmother Marie Rau and grandfather Ernst Hechler were granted a certificate of fitness to marry after a successful examination, but were denied a 'marriage loan,' a loan from the state to newlyweds.

"We never got over the shock that our family suffered," my grandmother writes elsewhere about the murder of her mother. And it seemed to be continually reactivated as a trauma. "What made her especially bitter is the impression that for many of the perpetrators involved, there was no remorse, no understanding of the criminal aspect; they felt themselves to have been in the right," my cousin Sebastian conveys his impression. My aunt concurs with her son: "Marie was upset because those guys didn't go to jail." The murder of her mother consumed her. When the trial began in Frankfurt in 1986, "my mother traveled there on the very first day to see for herself," my aunt remembers. "She followed the trial, all she could do was cry; she heard everything." Even as the trial was going on my grandmother wrote an affidavit in 1986 in which she filed a complaint of unconstitutionality, demanding a revision of the German Restitution Laws (abbreviated in German as BEG): "The details that have since been made clear to me by witnesses and joint plaintiffs devastate me and strengthen my own evidence: The 70,000 patients and defenseless victims were placed at the mercy of a gruesome, secret technology of murder that was tested out on them and consequently used in the Holocaust against those persecuted for racial-religious or political reasons."

4.3 The Third Generation

The third generation, under consideration here, consists of my father, my aunt, Martin (Walter's son) and Ludwig (Erich's son).

Not only my grandmother, but also my aunt bore the brunt of the after-effects of psychiatry's authority over my great-grandmother at her own wedding in 1963, eighteen years after National Socialism. "The night before my wedding with Malte […], Malte was warned that there was someone in my family who was mentally ill and that that could be an inherited trait." There were many physicians in Malte's family, and his parents upbraided him strenuously on account of the "bad heritage," he remembers. His son, Vinz, adds that on his father's side of the family, "word was that […] the insanity is on the Hechler side."

There is moreover a particular alertness to psychological abnormalities within the family. In 1982 my grandmother writes an anxious letter to another family member: "Much to my horror, I ascertained in my conversations in Lauterbach that the events surrounding Emilie Rau, née Listmann, were repressed for decades, that it was not discussed thoroughly with the children, and the smallest deviation from the presumed norm would now be measured against this trauma." The person with the "deviations," referenced here, is, according to my aunt, "also mentally ill, has a persecution complex." And she follows that with: "She is the only one in the family who is unstable." It is this postscript that takes on gravity in light of the killing of Emilie Rau. The fear that something else could still be inherited, that the "insanity" is in the family, lives on and puts the family on alert. "Perhaps it will break out again in a few generations," surmised one family member whom I interviewed, mulling over whether Emilie was "congenitally ill" or not. "I do have my thoughts about it now, [but] before this I was unsuspecting" is the reaction to this article, and "because of the earlier history [the murder of Emilie Rau] this [the crisis of the "unstable" family member] takes on a whole new meaning for me." Accordingly I was asked during my research into the family not to contact the person in question nor to "address it [the murder of Emilie Rau]," since my article would "not do" her "good." At the same time this was followed up by noting that the father (a son of Emilie Rau) "took care of his own family exceptionally diligently and with greatest love, especially his sick child. I think […] that the fate of his mother was an especially formative experience for him."

My father explains, "The topic of 'euthanasia' […] in the Rau household in Lauterbach was taboo. My cousins did not know anything about it. Ten years ago [circa 2003] there was a funeral, and my cousin Martin found out about it for the very first time there. It had been hushed up. Many families are ashamed, even now." Martin agrees with him: "It does not play a role in our family." He would like to "spare" his "family and their descendants […] having to ponder that this may arise." This portion of the family has a very different way of dealing with the murder of Emilie Rau than my grandmother and her children and grandchildren have. Martin not only carries on Emilie's family name, he points out as well the difference between my father and my aunt: "They live in Berlin and are anonymous in the big city. I am not anonymous here, I stand out in Lauterbach like a multi-colored dog." He fears "sensation mongering" and "being approached about this by people with whom I have no relationship," which he does not want. In spite of the taboo with the family and outside of the family, Martin and his wife "were in Hadamar a year ago for the commemorative event. My cousin, Ludwig, was also there." Ludwig was also present with my grandmother in 1991 "in Hadamar when the memorial site was opened." He is the only one of the family members I interviewed who still has "documents about that." Marie "wrote a letter now and then and sent articles. I have kept a portion of them. I also have a portion of Emilie Rau's medical records."

4.4 The Fourth Generation

The fourth generation includes my three older cousins (my aunt's sons), my sister Barbara, who is one year younger than me, and me, Andreas. My half brother, who is twenty years younger than I am, does not know about Emilie Rau, so he will not be discussed here.

Everyone in the third and fourth generation says that they learned about Emilie in their earliest childhoods and grew up hearing about her murder. No one delved into the case much more deeply than that, though, and not everyone knows what 'T4' is. Moreover no one, with the exception of Ludwig, knows anymore where their copies of the exhibition catalog, Transferred to Hadamar are. My grandmother had distributed multiple copies among the family after its publication.

In response to my asking when she learned about Emilie Rau's murder, my aunt said "I already knew as a child, only five or six years old." My father also said "I learned in my early youth that my grandmother was murdered." It is similar in the fourth generation. My eldest cousin Vinz says "I knew for a long time that she was murdered." My second eldest cousin, Udo, answered, "I was still a kid, but I couldn't tell you how old I was." My third eldest cousin Sebastian said, "Grandma Marie told us the story of great-grandmother […] when we were kids. That's why I was already occupied with T4 at that time, because I think that many people know absolutely nothing about what 'T4' was. Grandma had many books on the subject. Back then she had always wanted us, as kids, to develop an interest in politics […] that someone from the youngest generation take notice of that."

It was somewhat different for my sister and for me. My three cousins were able to understand the connections better because they were older. Udo says: "we had more contact to Grandma and you two were too young. The trials were in the '80s." My sister, born in 1978 and one year younger than I, and I learned the story of Emilie Rau through our father and not through our grandmother. "I only grasped from the periphery that that had been a major topic," my sister explained about my grandmother. I, Andreas, also did not pick up on a lot about the activities of my grandmother, surely for the main reason that she lived in Bensheim, in southern Hesse, and only lived in Berlin, where I grew up, during the last years of her life. So for my sister, the question of where she learned about this is significantly harder to pinpoint than for my cousins: "I don't know exactly. Those are fragments of memories that are pieced together from all sorts of things. Family reunions were occasions to talk about it, but never in depth." It is much the same for me, even though there was a decisive juncture that deepened my knowledge: when the German state wanted to force me to perform compulsory military service and I wanted to refuse completely, my attorney asked me whether anyone in my family had been persecuted by the Nazi regime. I remembered vaguely what my father had told me. Only in that context did I take the text about Emilie Rau from Transferred to Hadamar in my hands. It benefited me that, thanks to my grandmother, this case was well documented and that at that point those people who suffered because of National Socialist 'euthanasia' had been at last recognized as a category21 of victims of National Socialism. With that, I was released from compulsory military service.22 The entire dimension, though, has only become clear to me through the interviews and the writing of this text.

4.5 Connection to Emilie und Passing on of Tradition

My question of whether they felt any connection to Emilie was denied by almost everyone. At the same time almost everyone had been considering how to deal with exclusion and deviance and considered those questions to be exceedingly important. Still, my aunt had "never thought about [the connection to Emilie]" and does "not care that I never got to know my grandmother. I was only sorry for my mother, because she always cried so much." My father also has "no relation to Emilie Rau." When I asked whether Emilie played a role in his life, he said "No, absolutely not. But the treatment of the sick and disabled was always an important subject at home." Interestingly, he is the only one who refers to Emilie as "Emili" and calls her his "grandma." He never got to know Emilie, but he did meet Christian Rau's second wife.

For the fourth generation, it is similar, even though somewhat more ambivalent. For my sister Barbara, "it is not an issue that I am actively dealing with." For my cousin, Udo, Emilie is also not an issue. "But […] when other people are mistreated, I am also the one who makes himself unpopular among the crowd and says that something is not in order here. […] I attribute that to how I was brought up, very much shaped by Granny, who had a strong sense of justice; she had a powerful impact on us." My cousin Vinz, who had "no relationship" to Emilie, also responds to my question in this vein, recognizing that "she is one of the most interesting people in our family, whose roots I would most like to trace." He is also the one who communicates most openly how much he is affected by the fact that National Socialist ideology lives on: "I notice that I begin to sob when I think about the fact that things happened in Germany that should never have happened. Presumably [I sob] more than others. The terrible thing is that none of this is limited to the past, but is still taking place yet today." He, too, is of the opinion that one must take a position at the cost of a personal risk and brings this directly into the context of the struggle against Nazi-ideology and injustice. At the same time, Vinz "fought with our grandmother, because I said that […] people were interested in her […] because she was such a pretty woman and looked so 'normal' but not because she was murdered. Then Granny became really upset because for her it was all about 'euthanasia' itself; she hadn't really connected it so much with Emilie. She made that documentary with Professor Dörner, where that [National Socialist 'euthanasia'] was increasingly the focus. That was the argument. I was in my early twenties."

Family members of the third and fourth generations are less interested in Emilie's life than my grandmother. So conflicts arose not only because of differing views of what might be especially interesting about Emilie or what might not be. "People were increasingly annoyed because she was constantly talking about it" said my aunt describing her own and other's reactions [to my grandmother]. Other family members found my grandmother "exhausting" at times. My mother states this in a sharp way: My aunt and my father "were not sympathetic to their mother regarding the subject of T4." Accordingly, my aunt told my grandmother many times that "she should leave 'these old things' alone, it would upset her too much, or something similar. You can't change the past." On the other hand, my mother, who married into the family, says that "nothing was kept under wraps" and that she was confronted with the facts from the beginning. "Your grandmother often spoke at family gatherings for coffee about her mother, full of outrage and near tears that she was murdered in Hadamar."

My grandmother not only involved her own children, but also her grandchildren in the history of Emilie Rau, in the struggle for a dignified commemoration and political demands. My cousin Udo "was in Berlin, when Granny was also here in Berlin. There was a meeting of the Federation of People Aggrieved by 'Euthanasia. She stayed in the Federal guest quarters. She had also been invited […] I accompanied her to a session." Together with my cousin, Sebastian, she was in Hadamar in 1983 for the opening of the exhibition in the former gas and oven chambers.

This attitude towards remembering in order to advocate for a better society is also very strong among the third and fourth generation, with the exception of Martin, who "doesn't want to burden anyone in the family," asking "whether it does anyone any good." My father said to me in a conversation: "It was important to me that you knew about it. It's important to talk about these things so that more people know what can happen if you don't talk about them." Similarly, Ludwig said: "My children know about it, yes, certainly, we've often talked about it. There's also a book, Transferred to Hadamar, which we also have. Nothing is taboo with us." My cousin Vinz handles the subject in a comparable way with his two relatively young children: "Yes, we've already talked with them about how their great-grandmother was killed, but not in the context of 'euthanasia' or 'unworthy life', but who in their family were victims and who were perpetrators." Likewise, my cousin Sebastian has addressed these issues with his children: "Yes, I've told them about it. […] The subject of Nazis is an issue. I put a lot of value on their knowing what is good and what is evil."

Among the consequences that I, in the fourth generation, face, is that I have to think about my great-grandmother whenever I read something about Hadamar or T4, that it has often happened that I cry when I speak about my great-grandmother or the 2011 legalization of pre-implantation diagnosis in the Federal Republic, which for me has a direct connection to the discussions around 'life (un)worthy of living.' The vocabulary of the T4 masterminds, such as 'defective human being,' 'empty shell of a human,' 'spiritually dead,' 'inferior,' 'ballast existences,' 'useless eater' and the like similarly evoke in me immediate images of my great-grandmother. I had to think of her as well during a continuing education course that I took part in in 2012, when in one module, a psychoanalyst spoke condescendingly of her clients and ran up and down the list of every possible personality disorder in the ICD-10 and DSM-IV. I was increasingly bothered, sat in that course with tremendous rage and turned over this phrase again and again in my mind: 'this kind of pathologizing thinking cost my great-grandmother her life.' Even during my school years, I contradicted my math teacher when he proposed an economic scenario for analysis and explained that certain costs for caring for people were unaffordable. I wrote him a long letter and enclosed a text about capitalism and neoliberal reconfiguration of society.

4.6 Victims and Perpetrators

I see my great-grandmother as a victim of the Nazis. But the deeper I delve into the case, the more confused the roles of victim and perpetrator become. They are partially fluid, which became clear during my grandmother's life during the war and also shortly thereafter, not least because her marriage, as discussed above, was to a Nazi. "My father was a Nazi. He joined the party in 1929," said my father about my grandfather, Ernst Hechler, who was also an SA Member, and who died in combat in 1943 shortly after the defeat of the Wehrmacht at Stalingrad.

Just as ambivalent is that my grandmother intervened for Dr. Vollbrandt, the physician from Homberg who helped her to procure her certificate of fitness for marriage. He pops up again in 1946, when his wife writes to my grandmother that he was imprisoned and had to face charges in front of a hearing panel.23 She wrote the letter to request that my grandmother issue a letter exonerating him, which she did in writing and also later spoke in his favor in front of a judge. In 1982 my grandmother writes in a letter that "the evil spirit of euthanasia ceased in July of '41; in the Homberg-Efze district it was halted by Dr. Vollbrandt; that was confirmed in a denazification hearing by the pastor of Homberg-Efze." Whether that is true, I cannot verify, but I am skeptical in the face of the generally quite lax manner in which the Western Allies dealt with the Nazis. That they kept an 'innocent man' in prison for such a long time is hardly probable, not least of all because Dr. Vollbrandt had an elevated position in National Socialism. Why my grandmother defended him this way probably has more to do with the fact that she knew him, he helped her, and from that time on she saw herself as indebted to him.

The role of my grandmother's sister-in-law is also ambivalent. "Aunt Ursel was a social welfare worker," said my aunt, "she made lists of mentally disabled people. The lists were used to nab people and lock them up. She first heard that people had been taken after the fact." Within our family, 'Aunt Ursel,' like my grandmother, was considered to be an upright critic of National Socialism, at least after 1945.

Christian Rau always signed his letters with "Heil Hitler!," was a Police Chief Inspector, responsible for supplies for the armed forces, and affirmed his allegiance via his three sons, who all "do their duty for our Fatherland." That might not necessarily have been out of ideological conviction, but it could also have been tactically motivated, in the interest of his wife. But I consider this theoretical intellectual game also to be highly unlikely.

And not least, Emilie Rau herself. In her medical records there are several indications that she expressed anti-Semitic ideas in conversations with doctors. She was quoted, among other things, as saying "Dr. Wahlmann in Hadamar was in my opinion, a Jew, and said that he had been reformed." She also wrote "How can my husband have encountered the Jew Lehmann, the doctor at the Frankfurt psychiatric clinic?" It is not unambiguous, but one can already tell from the special emphasis on "Jew" that the content was anti-Semitic.

And one further dimension of the subject is important. It is distinctly easier for me to identify with my great-grandmother than with her husband or with my grandfather. The identification with perpetrators is for me an impossibility, although I recognize that perpetrators, too, belong to my family history. It is often a more comfortable way out, both in terms of memory politics and within the family, to resort to identification with the victims and to airbrush the perpetrators out of sight. But my (questionable) need for clearly defined victim and perpetrator roles in my family is not satisfied by the sometimes contradictory actions of individual family members.

5. In the Gas Chamber

They are left to sit on the benches. One hides himself in the corner. Another prefers to sit on the floor. The nurses motion to 'be quiet and wait' and close the door. The patients are alone. One stands up and starts walking in her stereotypical circle. One whispers and curses at something invisible. Then it hisses. It seems the showers are on. One lets her head down on the bench and then falls headfirst onto the flagstones. The one who had walked in a circle looks up and then collapses to her knees. On the bench one leans next to the other, slide down, two together and singly, falling over each other. The 'showers' hiss. (Döblin cited in Aly 2013: 66)

Thus quotes Götz Aly from a 1946 text by Alfred Döblin in the Freiburg Badische Zeitung newspaper; Döblin, who was Jewish, was at the time an officer of the French occupation. I cannot read this text without thinking about my great-grandmother, without imagining how she was one such person whose head slumped to the floor or who collapsed. What will she have felt and thought in those last minutes before her death?

Figure 5. Photo: An enlargement of the individual Emilie Rau drawn from the group photo in Figure 4.

Also from the following text passage from the catalog accompanying the exhibition, Transferred to Hadamar, I cannot read one word without picturing my great-grandmother in my mind's eye:

Every weekday from January until August of 1941, the vehicles of the GEKRAT24 drove from Hadamar to the intermediary facilities and back: first the transport directors with the list of names of those people who were to be picked up and then the gray buses […] with the transport attendants. In Hadamar as in all of the T4 facilities, the same murderous routine prevailed: after the buses had been driven into a garage built especially for this, the patients got out and entered the ground floor through a channel hallway on the right wing. There in a large hall they were undressed by attendants. Military coats were draped around the victims and they were led single file across a hallway into the physician's examination room across the hall. The physician's room was separated by a curtain: on the one side sat a civil servant from the office who determined the identity of the victim, on the other side, the doctor, who took a brief look at the naked person briefly rendered an opinion about which of the list of 61 false causes of death would be used for the death certificate. After this 'examination' the male and female patients would be led in line into a photo room, where three photographs were taken of each person: a full-body photo, one of the upper-body, and one in profile. Besides that, they were weighed. In a room across the hall the men and women had to continue to wait […]. Two [male] nurses led the patients down the stairs into the basement, into the roughly 14-square-meter gas chamber. […] After the group of people, probably 60 at the most, was forced into the gas chamber that had been disguised as a shower room, the nurses closed the gas-tight doors. The doctor who had just minutes before carried out the 'examination' now operated the gas tap in a small room nearby and released the deadly carbon monoxide gas through a pipe leading into the gas chamber. The gas entered through the holes and caused the victims to die by asphyxiation. The cause for the carbon monoxide poisoning was oxygen deficiency. The inhalation of the gas led to hearing- and vision impairment, nausea, heart palpitations, muscle weakness, agitation, and elevated blood pressure. The doctor in charge of killing observed the deaths of the people through a small window in the wall and turned off the flow of gas when he believed that all of the patients were dead. In general the patients languished. Many who recognized what was happening screamed, raged, and pounded on the walls and doors in mortal fear. After about an hour the gas was redirected outside through the ventilation system. Following that the burners, called 'disinfectors,' began their work. They had to carry the knotted corpses out of the gas chamber and take those whose brains were marked for removal into the post-mortem room next door. There, on two autopsy tables, the brains of the victims were removed and sent 'for scientific research purposes' most likely to the University of Frankfurt's Neuroscience Clinic and the University Clinic in Würzburg. The remaining dead were transported by the burners by truck to the room where the crematoria were. There, even their gold fillings were pulled. After that the burners burned the corpses of the victims in the crematoria.25 (Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen 2002: 89)26

Only the physicians were authorized to operate the gas taps. The medical director in Hadamar from January until June of 1941 was Ernst Baumhard. He worked under the name 'Dr. Moos'27 — all of the doctors who carried out gassings used an alias. He was just 30 years old when he gassed the 49-year-old Emilie Rau. His career began in the National Socialist Student Union, which was followed by memberships in the SA (Sturmabteilung or Brownshirts) and NSDAP (Nationalsocialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, i.e. the Nazi Party). He took part in the first 'trial gassing' in January of 1940 in the T4 killing facility in Brandenburg; he selected patients from the institution Bedburg-Hau and accompanied them to the T4 killing facility in Grafeneck. After that followed Hadamar; in June of 1941 he joined the navy. On June 24, 1943, his submarine was sunk.28 I ask myself: how can a person do so much harm in only 32 years?

Between January 13, 1941 and August 24, 1941, over 10,000 people in Hadamar were murdered by carbon monoxide gas, or 'disinfected' in the words of their murderers. The staff celebrated the murder of the 10,000th person (cf. ebda. 95; Klee in Hjardeng). The exact number of murder victims remains an estimate and will probably never be known because not all of the documentation exists anymore.

Nine so-called intermediate facilities were assigned to Hadamar, where those people who were to be murdered were picked up from each individual sanatorium and brought to Hadamar, all without previously informing any family members. From there they were summoned according to the available capacity and transported off to the destination: murder.

Upon Hitler's orders, the 'T4 Action' officially ended on August 24, 1941. The official termination was directly related to the critical sermons of Münster Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen (cf. Hinz-Wessels 2008). In Hadamar, the rooms where the murders had taken place were remodeled and the evidence of the crime was systematically destroyed. The released personnel were partially relocated to the east for the 'final solution to the Jewish question.' They were accustomed to murder, knew the procedures, and had shown themselves to be 'clean,' efficient, and discrete. What began as the first industrial mass murder of the Nazis in the six killing centers in psychiatric clinics and nursing homes—Brandenburg/Havel, Bernburg, Hartheim/Linz, Pirna-Sonnenstein, Grafeneck, and Hadamar—found its personal, conceptual, and institutional continuation and expansion on the extermination camps in the East.

Murdering in Hadamar continued in the meantime without gas: through methodical and intentional starvation, overdosing of administered medication and injections. Another almost 4,500 people met their deaths this way up until the end of the war. The circle of victims broadened, as it did in many other institutions: beginning in 1943 it grew to include people who had fallen ill with tuberculosis, forced laborers who were unable to work, forced laborers with mental illness, and children with one Jewish and one 'Aryan' parent who found themselves in an institution for corrective training (cf. Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen 2002: 118 ff.).

All of the doctors who took part in the Nazi 'euthanasia' did so voluntarily, and in most cases even enthusiastically. They were neither instrumentalized nor coerced by the Nazis (cf. Gruber n.d.).

Hadamar was and is a small town, a good 70 kilometers northwest of Frankfurt am Main. It is not off the beaten track, but in the midst of the people who live(d) there. From the surrounding mountains it was possible to look down upon the buildings of the institution; they were not surrounded by a wall, and a well-traveled road led right alongside the buildings. In Transferred to Hadamar it is written:

Every day the gray busses with the victims who were to die drove through the city; every day the chimney of the crematorium billowed smoke and spread a visible, thick, dark smoke that was visible from a great distance. Even the children knew what the institution was for; they called the buses 'murder boxes' and threatened each other: 'you're going into the baking ovens of Hadamar!' (Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen 2002: 95)

The smell of burned corpses and reports of the personnel of the institution led to the conclusion that the residents of Hadamar and the vicinity at least suspected the systematic murders.

In November of 1941, a young woman from Hadamar was arrested by the Gestapo and taken to a concentration camp because she had talked about the smoking chimneys and was denounced (cf. Ebd.158). Thus there was a real threat. This should not hide the fact, however, that the murder of the sick and disabled found a great deal of support. In my aunt's judgment: "Many were happy that the Nazis did it." The question that also arises with other groups victimized by the Nazis is how widespread was the agreement? How widely were ableist ideologies shared and supported?

The vestiges of the gas chambers in Hadamar were made accessible to the public on November 16, 1983. "It was particularly interesting and ever-present to me," my cousin Sebastian explains, in answer to my question about Emilie Rau, "because I was with Grandma Marie in Hadamar in 1983 when the commemorative plaque for which she had fought so long was unveiled. There was also a ceremonial act. […] I found that difficult, or disturbing, when we stood in that room where an ancestor had been murdered, even though one might not have had a personal relationship, but was nonetheless affected."

I: "What kind of feeling was that?"

Sebastian: "Difficult to describe. Trepidation. Inability to understand, and a certain unreality. It was actually just a room with tiles, like you'd find in a basement or a cellar, which as such didn't convey much if you didn't know the story behind it. And naturally you're influenced by the fact that you're standing there with your grandmother, who is very, very emotional because of this fact. And at 14, one just isn't so sure of himself when it comes to stirrings of emotion."

6. Processes of Identification

We are possible victims of a past in which people who think differently, feel differently, and behave differently were declared to be unworthy of living. We have presented ourselves before those places that meant death for our unknown friends. We wanted to commemorate their lives in our way and be near. To allow their fate to give us the strength to fight for our right to self-determination and mental-spiritual, political participation in social processes. Each and every one of us found it difficult to take on this project. But we were able to give solace to the spirits of our kindred ancestors and make clear that they did not succeed: 'we are still alive!'

Thus reads the accompanying text to the exhibit of the initiative 'Soul Meets World' of the association Kellerkinder, according to their self-description a "consortium of people with psychological impairments, those who have experienced psychiatry, and those who face mental strife." This consortium has traveled to all T4 killing facilities and leads a "confrontation with a collective trauma." Their project is called "Encounter with a Possible Past." The identification and empathy of these disabled people with the murdered disabled people during National Socialism is abundantly clear. They understand this history as their own; there is a collective space for remembering.

There is a second group with a valid reason to identify with those persecuted people whose lives were deemed 'unworthy of living' and to commemorate their lives: their descendants. But they hardly ever do; there are only a few texts and films that address this.

Memory is not detached from its social conditions. It says something about the differentiated impact in an ableist society that one group (disabled people) often identifies with the victims of National Socialist 'euthanasia' and commemorates their lives and the other group (the descendants of NS 'euthanasia' victims) rarely does.

It is significantly more pleasant to be non-disabled than to be disabled in this society. Family members, relatives, and later generations of people who were murdered because of their disabilities usually do not see themselves as disabled. Identification with the victims appears to be more difficult for those who do not have a disability than for those who do. The non-disabled family members have the choice to out themselves as a descendant of a 'disabled' person and risk entering into the sphere of the 'not normal' and thus to be made 'disabled' themselves. According to Nazi ideology, descendants are 'hereditarily ill' and it would be foolish to presume that this ideology no longer carries weight. In this regard, non-disabled descendants of disabled people can be affected by ableism. Or they choose not to out themselves and preserve for themselves their own 'normalcy' and 'health' at the cost of denying their disabled and murdered family members. Most of them decide for the latter.

This choice is not available to 'disabled' people, that is, to those who are regularly judged on the basis of their physical or mental capabilities and are discriminated against, who decidedly fall outside of the matrix of 'normal.' The cripple movement29 has consistently raised awareness of eugenics, 'euthanasia' and the murder of sick and disabled people. The non-disabled descendants of the victims of Nazi 'euthanasia' have hardly done that. My family, especially my grandmother, is an exception in this regard.

But then again, even among disabled people this remains a questionable construction given the enormous heterogeneity of disabilities. It tends to invite more of a negative identification, that is, the group is constructed from without and welded together through the same mechanisms of discrimination and the construction by outsiders as 'disabled.' Further similarities beyond that are not necessarily givens. 'Disabled' is to a certain extent an artificial concept. But whoever lives in this society as a disabled person, to whomever the slur 'Someone forgot to gas you!' has ever been hurled (only the tip of the iceberg of daily discrimination), then for that person, identification with the victims of National Socialist 'euthanasia' is comparatively obvious and comes naturally. This circumstance is important in terms of memory policies and politics.

6.1 Who Commemorates Whom? Remembrance and Identification

Survivors and their narratives are important aspects of teaching and learning about National Socialism and the processes of memorial politics. There were virtually no survivors of the Nazi 'euthanasia.' Even if there had been, many had no access to cultural techniques such as writing or publishing of memoirs or otherwise going public as survivors because of poverty or other social deprivation. Not to mention the lack of public awareness or interest. The dearth of reports from survivors impedes learning about, identifying, and remembering those who were hunted and murdered for being 'unworthy of life.'