This article considers two little-noted films from the early 1970s that took up a Black politics of "mental health." Both films intervened into racial-liberalist psychiatric and social scientific discourses of "Black pathologies" by drawing from Black radical and community-organizing models to envision how to care for people in distress outside of dominant psychiatric and psychological discourses and institutions. With shared production and institutional contexts yet differing articulations of what radical forms of care looked like both in practice, in narrative, and in mediation, these two films deepen our understanding of what form a Black disability politics of mental health took in this era. They also expand how disability studies as well as disability media studies frame the connections among anti-psychiatry and mad studies movements, Black radicalism and organizing, and cultural production.

For eight weeks in 1970, an integrated film crew shot Hitch: Portrait of a Black Leader as a Young Man on location in Harlem. The film, produced and directed by mental health film director Irving Jacoby and co-written with Black Arts intellectual and artist Julian Mayfield, was made to promote the Northside Center for Child Development, a mental health services center in Harlem run by Black psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark. During those eight weeks, two Northside Center volunteers and local community organizers, Sam Gaynor and Sam Walton, accompanied the shoot, observing the process of media in the making. In the following years, Gaynor and Walton would use their newly acquired filmmaking knowledge to write, produce, and direct Sam, Sam in Harlem (1974), a documentary about their own Black self-help organization, We Care. Recovering for film and disability studies scholarship these two little-noted films, 1 this article unearths how Black cultural production intervened in the politics of mental health/illness and racial liberalism's discourse of "Black pathologies" during this era. 2 Both films advanced a Black disability politics of "mental health care." In the case of Gaynor and Walton's documentary, the film articulated such a politics to Black self-determination of media.

The recovery of these films thus expands two strands of emergent disability studies scholarship. First, these films clarify what Sami Schalk names an emergent "Black disability politics" of this era, that is, "anti-ableist arguments and actions performed by black cultural workers which address disability within the contexts of anti-black racism." 3 Schalk argues that Black activists did not express these disability politics through concepts coming to the fore in (white-centered) disability (and gay) activism (identity, pride, etc.). Indeed, the films discussed here shied away from such language entirely. In fact, even as they countered psychiatric discourse and narratives, they eschewed the rhetoric and concepts of anti-psychiatry, of the emerging psychiatric survivor groups, and of alternative therapy movements. This elision underscores that a Black disability politics focused on "mental health" had a different genealogy from these other, white-oriented movements. The Black disability politics of mental health that these films advance constitute an incipient crip-of-color critique, to draw from Jina B. Kim. 4 Being designated "mentally ill," "mad," or otherwise deviant was not an identity to reclaim. Rather, the films represented how intersections of racism, sanism, and ableism pathologized Black life and supported policies that denied life-giving resources to Black communities. These independent media makers challenged the reigning discourse of Black pathology that derived from histories of medical and psychiatric racism and from social scientific discourses of the so-called "tangle of pathology."

Second, these films add to recent discussions about cripping film and media studies and about race and nontheatrical cinema. 5 These two feature-length films implicitly responded to and countered the narratives about Black communities in state-sponsored educational films, which reproduced tropes and discourses about Blackness as pathological and gave added fuel to policies depriving impoverished communities of color of resources. Producing countervisions to such state-sponsored films was an urgent matter. These films thus add a new valence to discussions of disability and cinema. They demonstrate that the history of disability and cinema is not as white as it might seem––that in fact Black media makers, even with the extraordinary challenges in getting trained and getting employed in the media industries, developed representational and narrative strategies to articulate a Black mad politics. 6

This article begins with a brief analysis of one state-produced pedagogical film, A Day in the Death of Donny B. (1969). Then, I undertake a comparative analysis of Hitch and Sam, Sam in Harlem. A film with competing narrative and ideological dynamics, Hitch demonstrates the pressure on independent media makers to conform to tropes and motifs that would satisfy audiences of different political commitments, including potential donors. Sam, Sam in Harlem develops what I call a vernacular aesthetics of mutual aid. The documentary's aesthetics, rooted in the everyday and quotidian, refused the visual, rhetorical, and narrative logics of mental health cinema. Reading Hitch and Sam, Sam in Harlem across their different visions of Harlem and in regard to their complicated production histories, this article reveals the industrial and aesthetic pressures negotiated by Black media makers who sought to produce countervisions of mental distress and its care.

Mental hygiene cinema as state promotional film

This section briefly outlines the racializing project of state-funded mental hygiene cinema. In the post-World War II era, mental hygiene film productions soared in number. They were exhibited in classrooms, at community theaters, and as part of professional training in mental health care education. As Kirsten Ostherr has argued, health films of all sorts (public health, individual health, and mental health) "were used everywhere, encompassing a wide range of topics concerned broadly with biopower, or the management of the self for the good of society." 7

One such health film illustrates the genre's racial-pathologizing project. Funded by the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and produced for the National Institute of Mental Health by the NYC-based Ad Council, A Day in the Death of Donny B. (dir. Carl Fick, 1969) was a fourteen-minute one-reel film distributed to high schools with an accompanying teacher's guide for discussion. Figure 1 shows the film's title frame, in which a young Black man nods out in a doorframe on a city street, with cars and people passing him by. 8 Accompanied by the title's articulation of Donny B. as dying, this frame suggests congruencies among Black masculinity, the street, and death.

The film's narrative follows Donny, a young Black man, as he loiters on the streets of Harlem, nods out, hustles for money, tries (unsuccessfully) to steal, fends off dope sickness, then scores and shoots up in a ruined basement setting. These observational sequences of Donny are intercut with interviews where people talk about Donny or about addiction. Some of these people may be his friends; for example, one woman says, "I know he's killing himself, and I have a sneaking suspicion that he knows he's killing himself also." Others are state officials: a uniformed officer shows the prison cell where police lock up addicts; over shots of the city morgue, an off-screen voice presumed to be the city coroner discusses the addict's life as one of social death. While some spoken words are diegetic, some of them accompany visuals of Donny, thus serving as commentary. Donny himself never speaks. A melancholy blues song plays for the film's fourteen minutes, with a repeating chorus, "Just another dirty ole day / in the death of Donny B."

The film employs cinema verité aesthetics; as Ostherr and others have noted, health and medical films made heavy use of aesthetics from avant-garde and experimental filmmaking, to the extent that some scholars, such as Lisa Cartwright, have asserted that medical films were imbricated with avant-garde modes of visuality. 9 In the case of Donny B., I argue its cinema verité style served its public health promotional aims, granting it an aura of authenticity and "hipness" 10 that would, in effect, "sell" it to those very audiences its narrative content pathologized. Associated with "liveness" and "the real," cinema verité aesthetics suggest that the short film is an addict's day in Harlem "captured in the making," not a fictional narrative scripted by the state. Its theme song grants it a hipness atypical to anti-drug messaging, and it lacks the overarching narratorial voice (the [white male] voice of God) that often served state documentary's authorizing function. Its aesthetics of the authentic, its hip bluesy theme, and its absence of a sonorous narrator code it as representing "voices of people," rather than of the state. In this, the film hides its state work of inculcating teenage viewers into proper (sober) citizenship.

Nevertheless, the film embodies sociological discourses that constructed the Black man as pathological, dangerous, and criminal; its formal silencing of Donny, who is literally without voice, representationally enacts sociological discourses in which "the Black man" was an object of study. Not insignificantly, the film codes Donny's failure to properly enact citizenship as queering him––a potential female romantic interest spurns him, and the teaching pamphlet encouraged teachers to point out to students that men who used heroin lost their ability to sexually perform. This was typical of public health cinema more broadly, which connected proper citizenship to proper health practices to proper heterosexual relations, and it would reappear as well in Hitch. 11

Hitch: Portrait of the Black Leader as a Young Man: Mental health films during Black Power

One motivation for producing Hitch was to promote the Northside Center for Child Development, a mental health services center located in Harlem and founded and directed by Black psychologists Kenneth Clark and Mamie Clark. In their extensive history of the Northside Center, Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner emphasize that during the period of Hitch's initial conception (1967–1968) the Center was consumed with questions circulating in Black communities nationally: how could and should professional institutions respond to and incorporate principles of community action? In Markowitz and Rosner's telling, both Kenneth Clark and Mamie Clark viewed militants' skepticism of middle-class professionals as deserved, and their efforts in these years centered on navigating how the Center could incorporate community organizing rather than reproduce paternalist liberal interventionist policies. 12

Perhaps with militant skepticism in mind, Hitch's producer and director Irving Jacoby hired Black radical intellectual and artist Julian Mayfield to co-write the script; letters between the two also indicate Jacoby attempted to hire crew from the local Black film production community. Jacoby, an established mental hygiene filmmaker, had in 1949 co-founded the Mental Health Film Board, which, in consultation with prominent midcentury psychologists and psychiatrists, over the next twenty-five years produced more than fifty mental health films. By hiring Mayfield and seeking out Black crew, Jacoby intended to craft a film whose production process honored Black radicalism and the local community. 13 Although the final cut of the film veered from Mayfield's early script versions, it contains a radical narrative remarkable for mental health filmmaking, including both explicit and implicit support of Black Power. 14 I will argue below that its most radical impulses were, by its conclusion, muddled: the film's production was funded by a racially liberal philanthropic organization, and the filmmaker would need more funding for additional distribution and exhibition, a constraint on just how radical it could be. In detailing its contradictions, I set the ground for understanding just how radical were Gaynor and Walton's interventions in Sam, Sam in Harlem.

Hitch's protagonist, sixteen-year-old Hitch, arrives in Harlem from South Carolina and soon after makes two friends: Ricky, a streetwise sixteen-year-old who drops out of school, self-medicates with heroin, and goes to jail for six months; and Nevis, a bookish and unhappy girl. These three teenagers reside in the same tenement building with their different families: Hitch, with his mother and grandmother, who await Hitch's father's imminent arrival; Nevis, with her mother and a father who ultimately leaves; and Ricky, with his aunt and uncle, who sell bootleg alcohol and run numbers out of their apartment. With the rebellious Ricky as his guide to the city, Hitch tries out all it has to offer a young Black man, which it turns out, isn't much: he and Ricky hawk stolen LPs for a neighborhood black marketeer, who compensates them with marijuana rather than money; they find work at a mid-town laundry, but the owner practices wage theft; and Hitch explores the possibilities for community transformation offered by the Panthers. Throughout the film, the three teenagers often return to discussing the lack of opportunities for children and young people, which is reflected in specific scenes and interlude shots depicting their impoverished school system, their lack of open spaces to play, and a racist policing system. All three characters, particularly Nevis and Hitch, express a desire to find a way to help the community. Nevis, referred by school officials to the Northside Center for therapy, transforms, by the end of the film, into a happy young woman who organizes a tutoring program for the area's children. After Hitch's anger at racism manifests in a moment of violence, he transforms through the mentoring of his tenement's superintendent, Mr. Vance, and in the film's penultimate scene Hitch joins Nevis to lead a program that tutors children in Afrocentric history and culture, thus fulfilling the title's promise of a "Black leader." The film's final scene follows Hitch and Ricky, just released from jail, as they walk through Harlem and talk hopefully about working to transform their community.

Hitch was produced at a time when cultural discourses about what comprised a male "black leader" revolved around the supposed apposite dualism of Malcolm X as violent resistance and Martin Luther King as nonviolent resistance. This is a trope that the film's title implicitly referenced, as shown in figure 2, and the film centrally thematizes which one of these kinds of leaders Hitch will become. In other words, the film's narrative was organized around mobilizing and answering this question: will an angry Hitch follow Ricky's path into a world of deviancy? Will he follow a Black Power program of violent resistance? Or will he take a different route? A social realist film, its narrative took shape around the moral dilemma between good and bad faced by a southern-rural jejune transplanted to the northern-city. It also drew on the era's teenage rebellion films, which often couched such rebellion within the frame of the heteronormative family, but with one significant difference: where teenage rebellion films such as Rebel without a Cause (dir. Nicholas Ray, 1955) posed rebellion within a white family over-saturated with parental presence, Hitch centered on a young black man rebelling due to an absent Black father and a matriarchal Black family structure.

Its first scenes introduce the film's theme of absent Black fathers. As Mr. Vance shows the dilapidated apartment, with rodents running through cracks in the walls, to Hitch and his mother, he informs them that Hitch's father, whom they expected to meet there, has left for a job in Indiana. Fed up with his family, Hitch exits the apartment to the street, where Ricky blocks his path and confronts him. As other teenagers watch, Ricky verbally, then physically, roughs up Hitch. Hitch surprises all of them by wrestling Ricky to the ground, an act that gains their respect and acceptance. Hauling a mattress up the staircase, Hitch meets Nevis, who asks why he's moved into "this dump"; when Hitch tells her "my daddy arranged it," Nevis says dryly, "That figures." These opening scenes highlight a shared distrust of father figures, and they suggest Hitch fights in the street to express anger about his father's absence. Furthermore, Nevis's words imply that her father has disappointed her. Nevis's verbal skepticism of men, combined with her androgynous dress and hair, code her as queer. Queerness thus is linked to paternal failure.

When Hitch's father Levi eventually returns, he visits Vance in the tenement's basement. The two men catch up over drinks, and as Levi becomes visibly inebriated, he explains that after being laid off from his job he has worked as a trash collector. Embarrassed by his poverty and subsequent self-medicating, he hasn't been able to rejoin his family. "Well hell I was a good worker there … Whatever I did, I did it hard… . But hell now I can't even work… . I'm good for nothing. Picking up junk is my speed, just about." Just as Levi's face collapses in anguish, Hitch enters the basement, recognizes his father, and begs him to rejoin the family. Levi refuses, and the actor's face, tightly framed, reveals the depth of his distress and fatigue. The meeting precipitates a dark night of the soul for Hitch, who abjectly wanders the city's dark streets, and, far from home, hails a cab, which bypasses him to stop for a white passenger. Furious, Hitch grabs the driver and beats him; on the verge of choking the man, Hitch runs off, returning to Vance's, where Vance advises Hitch to find a way to channel his anger constructively.

In other words, the film mobilizes tropes of Black male pathology: the absent/failed (and deviant) father and the deviant young Black man whose deviancy arises from the father's absence. In particular, Hitch's assault on the driver reproduces cultural discourses, prevalent after the 1968 riots, of Black male violence. These tropes also parallel arguments made in Daniel Moynihan's influential The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, that racial inequality was entrenched due to the so-called failure of the Black family structure to mirror that of white middle-class family structure. 15 The film also draws on what Moynihan identified as one site of Black familial pathology, the matriarchal family structure: Hitch's family unit comprises his mother and his grandmother; and Nevis's unit is herself and her mother.

In his work on the The Negro Family and the public discussions it provoked, Kevin Mumford argues that although Moynihan's publication has become associated with its pathologization of the Black matriarchal family structure, the actual work is concerned more with the black male as a deviant subject than with the trope of the matriarchal family structure that has come to dominate how it is remembered. 16 As Mumford highlights, in the publication Moynihan described "the black man" as neurotic, engaged in immature behavior, and looking for instant gratification. By revisiting the eventual published version in the context of Moynihan's unpublished papers, Mumford convincingly argues that descriptive terms and frames for "the black man" in The Negro Family coded, and that they were code for those supposed deviant sexual behaviors that steered the black male away from assuming the normative position of manly father and breadwinner.

Taking Mumford's queer-studies–inflected reading of Moynihan's publication as a starting point, I will argue that Hitch's narrative at once attempted to de-pathologize tropes of "the tangle of pathology" yet reproduced them by connecting "mental health" to heteronormativity.

For the film explicitly narrates Hitch's reactions, Levi's situation, and Ricky's addiction as caused by experiences of racism, capitalist labor and housing exploitation, and racist educational systems. In this, the film dilutes psychologizing and pathologizing discourses that either deployed or reproduced biological racist tropes. At the same time, Hitch's anger is framed as the failure of a proper Oedipal and white middle-class family structure. In this sense, a psychiatric logic, and one that mirrors the Moynihan's Report general argument, orders the film's narrative. And perhaps most importantly, Hitch and Ricky's relationship includes moments of possible homoeroticism, including when they peep through a window to watch a neighboring woman having sex and when they relax together on a rooftop getting high. The "tangle of pathology" seemingly surrounds and tempts Hitch.

Yet the film also includes alternatives to the white liberal interventions suggested by the Report's focus on "fixing" the Black family. First, the film provides a substitute father figure in Vance. Second, the film represents the Black Panthers as an opportunity for young Black men to care for the community. Ricky and Hitch follow a group of children merrily running into a building, then observe them being cooked and fed breakfast by a Black Panther. Hitch says, "I thought they spent all their time shooting it out with the cops. What're they doing with kids?" Ricky responds, "That's part of their thing!" Hitch says he wants to think about joining them. As the audio track fills with the Panther leading the children in singing "Gimme that ole revolution!," the camera surveys an exterior wall filled with Black Power posters, zooming out to reveal it as the front of a Panther Party meeting space, from which Hitch exits––he has met with the Panthers to explore their work. This scene thus legitimates the Panthers as an organization delivering care to the community (rather than violent state confrontation) and, occurring early in the film, sets up the possibility that Hitch might become a Black leader in their style.

Then, the film's concluding scenes show Hitch's evolution into a leader who provides care to children. After Hitch accepts Nevis's invitation to join her in her tutoring program for Harlem's children, both characters are shown reading to the children, leading them in martial arts and dance, and educating them about history––specifically, about Haiti and its self-governing, Black, formerly enslaved people. The scene does not explicitly name what kind of school this is: Nevis calls it Time for Children, leaving its viewers to make extra-textual connections. If they have such knowledge, they might recognize that its curriculum is not one Nevis and Hitch devised on their own but it is modeled on the Black Panther Liberation Schools. 17 By leaving unnamed the Black radical nature of their curriculum, the film allows for different interpretations by different kinds of audiences. For some, it will be obvious that Hitch has integrated Panther teachings and is following in their path of leadership, becoming a Black radical leader. For others, Hitch and Nevis have become educators for their community, a less radical, more white-liberal friendly assumption of proper citizens engaged in the social reproduction of labor.

Here, the film evidences the tensions between the Black Marxism of the Panthers (and Julian Mayfield) and the racial liberalist stance of the film's financial backers. In 1967, Jacoby received an initial grant of $40,000 from the Grant Foundation, a philanthropic organization, and he needed an additional $80,000 to cover the film's entire budget. In late 1968, the Grant Foundation decided to provide the additional funding. In a letter to Jacoby, its director wrote, "[T]he situation in Harlem and other ghetto communities is developing so quickly that time is a very important factor." 18 It is not entirely clear what the Grant Foundation assumed the film would do to address "the situation," but it is clear that a film promoting psychiatric services to urban youth appealed to the Foundation as a means to address something––possibly the growing appeal, in 1968, of Black radicalism to young people. By the time of the film's initial exhibition in 1971, Jacoby promoted it with a press release that highlighted the racial liberal framing of art as a means to promote white people's sympathy: "There are six-million [sic] Black adolescents in America. To many Whites, this group is frightening and threatening. The film reveals Black adolescents as a source of strength and productivity." 19 The competing interpretations its final scenes make available underscore that the film negotiated this conflicted terrain.

Even as it was meant to promote the psychological services of the Northside Center, the Center never appears; instead, Nevis discusses with Hitch her experiences in therapy with a white female therapist. When Hitch expresses skepticism about discussing one's feelings with a white lady, Nevis responds that while at first she felt similarly, she ultimately found the therapist trustworthy and felt better after their sessions. The film represents Nevis's psychological improvement through changes to her appearance. She starts wearing make-up, earrings, and more feminine clothing. She also plants a kiss on Hitch's cheek, sparking an expression of romantic interest on his face, after which Hitch joins Nevis in their proxy heterosexual parental figuration as leaders of Time for Children. In other words, therapy heteronormalizes the previously queer-coded Black woman. Additionally, establishing Nevis and Hitch as heterosexual resolves the potential homoeroticism of Ricky and Hitch's relationship. In other words, because of therapy, Nevis ensures Hitch's entry into normative sexuality. We see here a very conventional psychiatric-inflected narrative as a necessary intervention into the queer pathological sexualities assumed in cultural discourses about the presumably pathological Black family and the non-normative sexualities it presumably sparked. Therapeutic intervention re-establishes the heterosexual parenting unit.

Sam, Sam in Harlem: Documentary aesthetics for mutual aid

With an understanding of how the normalizing logics of the psy-ences (both psychology and psychiatry) and their racial-liberal imperatives informed Hitch, we can turn now to the Black disability politics of Sam, Sam in Harlem. The metaphors we often use to describe one cultural text's relation to another––"revisions"; "re-envisions"––are, in this instance, as material as they are figurative, since Gaynor and Walton literally watched the film crew shooting Hitch, then, with their film, revised its cinematic vision of Harlem. In a 1976 grant application for funding for their films, they implied this re-envisioning in an articulation of their cinematic philosophy: "[We Care films] often portray subjective conflict, a thematic core of expression of the community. There is no story or plot, in the conventional sense, rather a pictorial action piece with dramatic intensity and perception of the residents rather than [of] the film maker." 20 This philosophy of documentary––capturing "subjective conflict"––and its philosophy of multifarious subjectivities in conflict as constitutive of the community's self-expression explicitly contests the narrative logics that shaped Hitch––where the filmmaker arrived on set with a preordained interpretation of the community hardened into the script, and where narrative logics of resolution worked to contain and resolve conflict. I will argue that Sam, Sam in Harlem presented the community as self-determining, engaged in its own expressions of conflict and methods of care that required neither resolution nor the state's intervention; rather, the film argues for more expressions and mediation by expanding community-determined media productions. The film adds to our understanding of how Black activists used media to engage with Black disability activism within the Black public sphere.

Both Gaynor and Walton were community residents who volunteered, in the summer of 1968, to tutor children who visited the Clarks' Northside Center. Initially hesitant to engage non-professionals, ultimately the Clarks warmed to them and helped the young men, enlisting them for their tutoring services and vouching for them with funding agencies. 21 In 1971, Gaynor and Walton proposed developing a project for youth leadership in communications media, 22 and from this, received, in 1973, limited technical support from the local ABC office as they wrote, directed, and produced this one-hour documentary about their activities as leaders of We Care. 23 It was broadcast in 1974 on the New York City ABC affiliate and shown to local Harlem audiences.

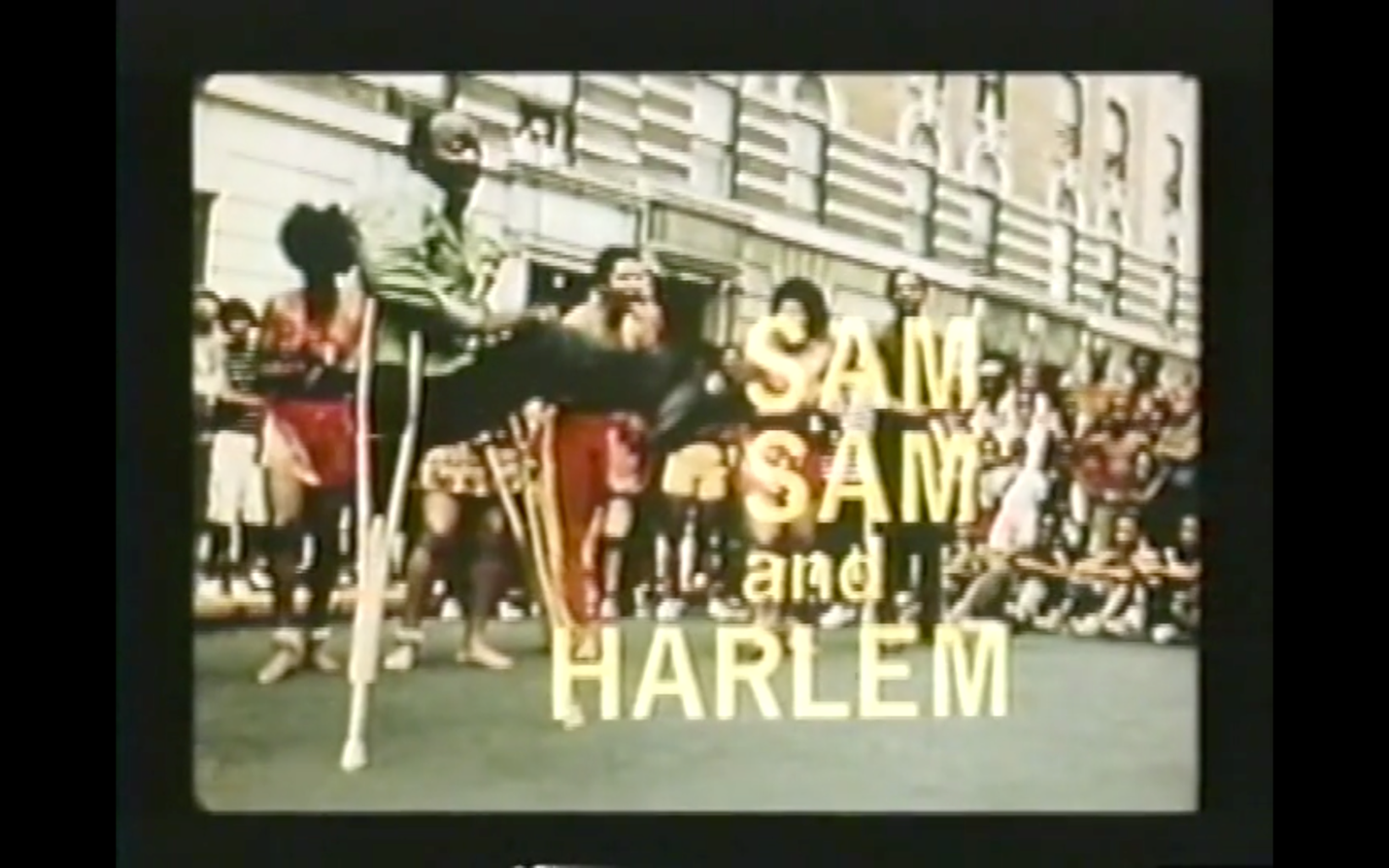

The film opens to a street fair, where young Black dancers, clothed in a dance troupe uniform, perform while drummers fill the air with rhythm. As a throng of onlookers cheer and sway, an older, one-legged man in everyday clothes enters the circle and, using his crutch for support, dances. In a freeze frame, the film's title, Sam, Sam in Harlem, appears beside this dancing man (fig. 3). This freeze frame thus foregrounds that this is a signal image for the film, that it contains the film's main themes: community cultural expression on the streets.

Following this initial sequence, a male narrator talks about the topic often used by liberal reformers as evidence of "ghetto pathology"—violence in Harlem––in a rhetoric that de-sensationalizes it. Scenes of a funeral procession entering a church are accompanied by his words, "We had a shootout here last week, a black cop and two suspects dead." As a woman in the procession falls and another woman cries, "Momma, please stop crying," the camera cuts to four black men, one looking at the camera, while the narrator says, "If you live in Harlem, you see a lot of that stuff." The heightened emotions of grief at a funeral are narrated with rhetoric that names the experience as pedestrian, a rhetorical denudation of "black-on-black" violence of its import in public discourse about Black pathology. Credits appear identifying the narrator as Arthur French; his diction is colloquial, the rhythm of his words sparse, and the voiceover is distinct from the white diction typical of news documentaries of the time, embodied in voices such as Edward R. Murrow's. 24 The next scene follows two Black men through Harlem streets as they greet people and linger to look at street vendors' wares. As they wander, the narrator says that one can get an education on the streets of Harlem, "in drugs, crime, and some other things too," and that the film's two protagonists "dropped out of school when they were sixteen, and 125th street was their college." The camera enters a bookstore, "the library for this college," and pans to the books displayed both in shelves on the sidewalk and in the store. The proprietor, Mr. Michaux, then explains that all the books in his store are about and by Black people, "save Webster's Dictionary." In this library, French narrates, Gaynor and Walton have read Black history, including Malcolm X, and it was after reading Malcolm X's printed words that they then went to listen to him speak at public appearances. 25

With a voiceover that abjures the formal diction typical of broadcast news and public television documentary as well as its theme of the street as a place of education, the film grounds itself in a knowledge-discourse distinct from that organizing mainstream representations of Black life, which relied on social-scientific knowledge-discourse that coded the ghetto as pathological. The vernacular, the quotidian, the street: these are generative of knowledge.

Multiple sequences establish Harlem streets as knowledge generating. From the bookstore as archive of knowledge and educational site, the film cuts to a sequence of public gathering spaces. This sequence begins first with a clip of Malcolm X, itself mediated (it appears to be a televised speech), exhorting a Black audience to demand that the city fund Harlem schools. This cuts to the streets of Harlem, where Black figures, each identified by caption, address crowds of people: Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., surrounded by multiple microphones and reporters; Charles Kenyatta; Lucille Levy; and finally, Pork Chop Davis. In cutting from Malcolm X's mediated event to these street scenes, the film emphasizes that a Black public sphere, electronically projected over either television in the case of Malcolm X or microphones and loudspeakers in the case of Powell and others, exists on the street. The biographical captions draw from the documentary convention of identifying authorities and thus establish these figures as Black authorities. Thus at the same time that this scene establishes Harlem residents and activists as authorities who circulate their own knowledge-discourse, its form strips official discourse of its claims to truth reiterated in broadcast media.

Scenes where Gaynor and Walton speak to people experiencing addiction 26 * on the street visually encapsulate an aesthetics of reciprocity. As seen in figure 4, four Black men sitting on a sidewalk stoop hail Gaynor and Walton, and as the two groups of men begin speaking, the camera zooms in to a close-up on the seated speaker, who wears a bandana headband and a dangling earring (fig. 5). He speaks to them with a blunt, raw attitude, saying, "I hear you all got a little thang going on, doing a little help for somebody … I'm out here man, I'm trying to get a little across, man, but I can't seem to get a play, man." The scene cuts to a mid-range close-up of Gaynor and Walton crouched down on the sidewalk. Their eyes appear to be level to the man who is speaking, and they are intently listening to the speaker (fig. 6).

Men seated on a stoop, hailing Gaynor and Walton, Sam, Sam in Harlem. Used with permission of Oren Jacoby.

Close-up shot of man with bandana and earrings addressing Gaynor and Walton, Sam, Sam in Harlem. Used with permission of Oren Jacoby.

All three men discuss the man's work history. He explains that he recently got out of jail and has been experiencing addiction for ten years. During this conversation, it is difficult to hear Gaynor and Walton; their voices are muted, the sound levels louder when the man experiencing addiction speaks. 27 This formal choice that diminishes Gaynor and Walton's words and amplifies those of the man experiencing addiction comprises a reciprocity between the voice of the man and those who seek to care for him, and it resists the conventional formal devices in non-theatrical cinema that silence those with addiction in order to let the voices of the state speak about them—the formal silencing of the man experiencing addiction in Donny B. It contrasts with Hitch too, where Ricky and the addiction he experiences, while sympathetically depicted, is constructed within a narrative that encourages speculating about causes (is it familial dysfunction? a poor educational system? a lack of opportunities?), rendering it a problem requiring psycho-sociological knowledge-discourse. When the film cuts to a different location, Gaynor and Walton talk with a woman experiencing addiction who tells them that she keeps trying to enter a rehab program but is always told the program can't help her. The scene concludes with her words: "I mean, I need help!" The denial of desired care suggests she experiences medical racism and highlights state austerity policies toward Black communities.

In another scene, the two men counsel a woman standing in front of a parked car, cars passing by behind them. Their discussion centers on gathering information from the woman so that they can figure out how to direct her to work opportunities. This emphasis on care taking place on the street itself, realized in the continued mise-en-scene of the sidewalks and streets, foregrounds the community in the street as the site of locution, as producer of meaning. (This is not to say that there aren't scenes that take place in interior spaces—in fact, some do, but such scenes concern organizing efforts, which are different than the actualization of care shown in these other street scenes.) That meaning becomes legible once the media production is spatially embedded within the street itself. The film thus eschews the social scientific gaze of "the street" common in the 1940s photo-text style that Paula Massood notes dominated magazine representations of Harlem projects and that moved into cinema through the quasi-documentary The Quiet One (dir. Sidney Meyers, 1948), a gaze derived from the knowledge-discourse of racial liberalist institutions and used for racial liberalist goals of engendering white people's understanding. 28 The film makes specific formal choices that divest "the street" of culturally hegemonic discourses; it stages itself––through its mise-en-scene, sound, and diction––as indexing Black knowledge. In doing so, its producers/subjects, Gaynor and Walton, articulated a documentary method that countered the genre's origins in ethnographic filmmaking, with its heritage of Othering its documentary subjects. They also challenged the popular genre of television documentaries about "problems of the urban ghetto," which often championed social scientific discourse and rendered "life on the streets" as a problem for liberal interventions.

In other words, the streets circulate and produce Black education and knowledge in this film, and it tracks this circulation in its organization of scenes that move between exterior spaces and interior spaces, and by describing communications media as the method by which such circulation can be accomplished. This is more than a flâneur style of filmmaking––the film is doing more than traveling and spectating: it intends its movement through the exteriors and interiors of Harlem to provide a route for the future mediamakers the film aims to engender. 29 In a sidewalk scene, Gaynor and Walton talk to a single mother who needs help, the street serving as their office, and they discuss sending her to the Northside Center for counseling and for work placement. Following this, an interior scene shows this young woman being introduced as a We Care summer worker to a switchboard operator. She sits and, as the operator explains how to work the switchboard, watches. A side-angle closeup showcases her intensity, and when the switchboard operator's arm cuts through the frame to work the machinery, our attention is directed to the communications media on which the two people work. The care Gaynor and Walton provide on the street moves the woman from the street to learning control of communications media. (And different from how Hitch frames its young Black girl and Northside Center, here counseling is an instrument for entering the workforce, not for heteroreproductivity.)

Subsequent scenes concern other We Care educational and tenant aid efforts, which culminate in scenes of community control of media. An audience of young black people listen to social workers speak about how to enter the profession; this is followed by scenes showing a We Care office meeting, then We Care working for tenants by reporting rat bites to the city and helping tenants file documents with city bureaucracies. Then, the narrator states that, to improve the poor press coverage of Harlem, Gaynor and Walton contacted United Press International, which furnished help; an interior scene shows a white journalist advising young Black people on how to interview, and the next scene shows them, outside, using microphones to interview local residents. In other words, following scenes of young people being tutored in communications media (the switchboard) and receiving educations in entering the caring professions, and scenes of We Care working to improve people's living conditions, the film climaxes in this scene of youths learning how to use mass communications to document their own community––practicing community control of representing Harlem.

The film then returns to a street, where children play hopscotch on the macadam, and Gaynor and Walton wander among them as they return, the narrator tells us, to their real education, "on the streets." This final scene shows people, including children, reading and circulating a newspaper with a headline about Harlem (presumably the one that We Care has produced). They encounter a sharply dressed man, and the narrator says, "Sometimes, you just can't make your case." They ask the man if he would consider volunteering some time to help Harlem's children, and he pushes one of the children out of his way as he struts off, saying, "I ain't got time for that… . I'm in a hurry." One of the Sams says, his tone dry and bemused, "I'll see you later Frank." The children cheer as Frank speeds off in his Cadillac. While much about Frank––his mannerisms, his attitude, how the We Care group responds to him––suggests he might be schooled in the other kinds of education the film mentions (e.g., drugs), neither the narrator nor the Sams name him as a problem. Rather than drawing on sociological discourses that might label Frank an example or a symptom of urban pathology, the film conveys the community responding to him with irony and humor, and the suggestion that they will welcome Frank should he decide to join their work of mutual aid. Here we see a clear instance of Gaynor and Walton's documentary philosophy: ""[We Care films] often portray subjective conflict, a thematic core of expression of the community." In other words, rather than elide this scene of Frank, possible symbol of pathology, from the film, and rather than fit Frank into a narrative of deviancy, the film shows the varieties of conflict – multifarious subjectivities – happening on the street. In fact, that the film comes to its conclusion with this scene, I would argue, highlights this conflict, which as Gaynor and Walton state, is, to them, a "core of expression of the community." This is a theory of mutual kinship: not of subject and object, not of wielder of knowledge and object of knowledge, but rather of mutual subjective humans in kinship (and conflict) with each other.

The film ends with a scene that returns to the street festival that opened the film. The narrator says, "It's like Pork Chop Davis says: the black man has to get organized to help his own people; that's what We Care is all about!" As shown in figure 7, this time the one-legged Black man throws his crutch away, dancing on one leg as the people raucously cheer him on. Then, with another freeze frame on his joyful figure, credits appear that thank the entire community for contributing to the making of the documentary itself.

In their history of the Clarks' Northside Center, Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner interpret this scene as a representational prosthesis, where the disabled man no longer needs his "crutch" due to the power of We Care to "make able" the Black community. 30 This does seem one possible reading, especially when the scene is considered in relation to the narrator's words. Yet as Sami Schalk argues, concepts from white disability studies, including narrative prosthesis, where race was not a constitutive underpinning of the conceptual framework, do not necessarily translate directly into racialized contexts. 31 In light of this, I want to consider other readings. 32 The film concludes with the same street celebration that began the film. The conclusion has one significant difference from the opening scene: it is not followed by a cut to a funeral for a Black cop and two Black suspects. This return to the street celebration might thus be read as a reclamation of the streets for Black male joy, rather than showing the streets as places of mourning. It might also be read as a scene of an individual "overcoming" disability, or even as inspiration porn. We might also consider the ways in which the film at certain points centers Black men and Black manhood, and that this final visual scene, combined with a narration that centers Black men, might gesture toward what others have identified as weaknesses in social movements that failed to dismantle heteropatriarchy. 33 Yet if we consider that the man is surrounded by other dancers and musicians, perhaps we might read this as an invitation to think beyond conceptual categories of disability and ability, beyond mental health and mental illness. Perhaps the final dance remarks on art itself as a form of mutual aid.

Conclusion: Objects and Orientations of Disability Media Studies

Although Gaynor and Walton's film does not explicitly address this fact, I argue that their work should be contextualized within the broader media and technological landscape of 1973: the rise of a culture of information and informatics. With its multiple media and technologies, including the switchboard, the newspaper, and filming interviews on the street, the documentary gestures to how Gaynor and Walton viewed communications media as integral to a Black-determined politics of information. Their many grant applications sought out additional funding to increase the circulation of their newsletter, City Scene, which expressly aimed to help Harlem residents with social services, health information, and understanding new city policies as they went into effect. They saw this as a form of information activism, of expanding the Black press during a time in which, at least as they argued in a grant application, an unnamed city-wide Black paper was under fire for not serving its Black community.

In Crip Genealogies, the co-editors note that "crip" serves a function as a term in opposition to how "disability" has come to serve (racial liberal) bureaucracies and their resource-appointing and -diminishing functions. 34 It could be argued that, in acting as intermediaries between Black residents and city services––in some senses, in doing the work that the state would not do––Gaynor and Walton perhaps supported the state. Yet reading their media production through the lens of Black disability studies refutes this. Theirs was a resistant practice. In their documentary, they resisted pathologizing tropes and aesthetics, including the rhetorical and aural expression of social scientific discourse typical of television documentaries about "the ghetto." They worked to construct a public sphere that could become self-sustaining in its mutual aid efforts, using whatever means available to keep a self-determined Black media and information ecosystem funded. They sought methods to make information available to all. Thus, not only do I argue that we should consider the film they made Black disability media, but I also argue that we should consider their entire project a form of crip-of-color information politics.

Jina Kim elaborates crip-of-color critique as mobilizing disability not as a noun but as a verb—drawing on Ruth Gilmore's definition of racism, Kim defines this as "the state-sanctioned disablement of racialized and impoverished communities via resource deprivation." 35 In New York, the Urban Institute's MATH microsimulation model was at the center of debates over welfare and food stamps, making headlines as state agencies instituted "policy analysis" into their decisions. 36 By elucidating structures of interdependency and mutual aid arising to combat the state's practices of debilitation that targeted Harlem and its communities of color and by eschewing state-funded service provisions, Gaynor and Walton implicitly rejected the "sciences" involved in these decisions. Through a vernacular aesthetics that similarly countered the expert, social-science derived aesthetics of mental hygiene cinema, their revisioning of caring for people in distress through community-determined media was, in essence, a practice of mutual aid through cultural production.

Endnotes

-

As far as I have been able to discern, only one of the films has received scholarly attention. Sam, Sam in Harlem is discussed in Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner's history of the Northside Center, Children, Race, and Power: Kenneth and Mamie Clark's Northside Center (New York: Routledge, 2000), 212. They do not discuss the other film made in relation to the Center, Hitch, although it is identified in the guide to their papers held at Columbia University's special collections. My own archival discovery process involved working across archival erasures: although the film is listed in their papers' finding aid, when I requested more information, the archivist at Columbia discovered the library did not actually have it. So, I returned to WorldCat, which listed the film as held by a few libraries. However, those libraries held a completely different film: the same-named film from 2005 that starred Will Smith. I then posted to a film-archivist mailing list, and an archivist at New York University unearthed the 16mm film in their holdings; I was finally able to view the film. Realizing Julian Mayfield had co-written the film, I sought out information in Mayfield's papers at the Schomburg Center; in those holdings, the film was not identified by the title Hitch but the working title Child of Anger. A print of Sam, Sam in Harlem seemed completely erased, until Rick Prelinger of the Prelinger archives suggested that I contact the son of Hitch's director Irving Jacoby, who is himself a filmmaker. It is out of a wish to honor the legacy of these filmmakers that Oren Jacoby (Irving Jacoby's son) gave me access to Sam, Sam in Harlem. Here, I would like to acknowledge and thank Oren Jacoby for his generosity in sharing the film with me. I would also like to acknowledge and thank the copyright holder for Sam, Sam in Harlem, the wife of the now-deceased Sam Walton, Sonia Walton. I would also like to emphasize that this convoluted path to finding prints of both films speaks to the archival erasure this article seeks to redress.

Return to Text -

This article uses "racial liberalism" in two senses. First, following Dennis Doyle, I use it to refer to a group of post-WWII professionals who understood psychic equality as tied to social equality and broke from the racialism of the past that ascribed biological differences to blacks and whites. Second, following Jodi Melamed, I understand it as well to be an ideology that, with its focus on normalizing presumed pathologies of black sociality, including through psychological normalizing, effaced race-radical critiques of US racialization as racial capitalism. Also following Melamed's reconstruction of the networks among robber-baron philanthropies, social scientific discourses, and "the race novel," I understand racial liberalism to support—financially and ideologically—cultural works that appeal to white people's sympathy. See Dennis Doyle, Psychiatry and Racial Liberalism in Harlem, 1936–1968 (Boydell & Brewer, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1017/9781782048442; Jodi Melamed, Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism (University of Minnesota Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816674244.001.0001

Return to Text -

Sami Schalk, Black Disability Politics (Duke University Press, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478027003

Return to Text -

Jina B. Kim, "Toward a Crip-of-Color Critique," Lateral 6, no. 1 (2017).

Return to Text -

Robert McRuer, ed., "In Focus: Cripping Cinema and Media Studies: Introduction," Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 58, no. 4 (2019): 134–39, https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2019.0042; Allyson Nadia Field and Marsha Gordon, ed., Screening Race in American Nontheatrical Film (Duke University Press, 2019).

Return to Text -

On the media industries, Black film crew, and Harlem in particular, see Noelle Griffis, "`Open the Door and I'll Get It for Myself': Minority Production Assistant Programs and the Politics of the Urban Location Shoot, 1969–1974," Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 62, no. 3 (2023): 60–85. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2023.0026.

Return to Text -

Kirsten Ostherr, Medical Visions: Producing the Patient through Film, Television, and Imaging Technologies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 81.

Return to Text -

The film can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rH6K3Lm2wZ4 and here: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/88815.

Return to Text -

Lisa Cartwright, Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine's Visual Culture (University of Minnesota Press, 1995).

Return to Text -

Ostherr, Medical Visions.

Return to Text -

See, in particular, John Parascandola, "Syphilis at the Cinema: Medicine and Morals in VD Films of the US Public Health Service in World War II," in Medicine's Moving Pictures: Medicine, Health, and Bodies in American Film and Television, ed. Leslie J. Reagan, Nancy Tomes, and Paula A. Treichler (University of Rochester Press, 2007), 71–92.

Return to Text -

Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner, Children, Race, and Power: Kenneth and Mamie Clark's Northside Center (New York: Routledge, 2000).

Return to Text -

It is entirely possible that Jacoby also wanted Black crew due to ongoing racial tensions in New York that were affecting film productions. However, there is no explicit evidence for this in the existing production notes. See Griffis, "`Open the Door.'"

Return to Text -

Portions of the script are located in the Mayfield Papers at the Schomburg Center for Research into Black Culture, New York.

Return to Text -

Daniel P. Moynihan, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (Washington, DC: Office of Policy Planning and Research, US Department of Labor, 1965).

Return to Text -

Kevin J. Mumford, "Untangling Pathology: The Moynihan Report and Homosexual Damage, 1965–1975," Journal of Policy History 24, no. 1 (2012): 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030611000376

Return to Text -

Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (University of California Press, 2016).

Return to Text -

"NCCD Film, Irving Jacoby Producer," Markowitz and Rosner Papers, Columbia University.

Return to Text -

"The Mental Health Film Board Announces the Release of Irving Jacoby's Hitch," n.d., "NCCD Film, Irving Jacoby Producer," Markowitz and Rosner Papers.

Return to Text -

Letter from Samuel Walton, Director We Care, to Linda Gillies, Director Astor Foundation, "First Draft Proposal," October 6, 1976, Vincent Astor Foundation Records, Grant Files, 1976, We Care, New York Public Library Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division.

Return to Text -

Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner, Children, Race, and Power: Kenneth and Mamie Clark's Northside Center (Routledge, 2013), 208–13. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315023106

Return to Text -

"We Care Group, 1969–1973," Ella Baker Papers, Box 13, Folder 36, Schomburg Center.

Return to Text -

Letter from Ana Maria Stephens, Director Community Relations, ABC-TV, to Sam Walton, November 21, 1973, Box 3, File 19, "NCCD – We Care Group General," Markowitz and Rosner papers.

Return to Text -

French had at this point appeared as a character in an episode of The Bill Cosby Show.

Return to Text -

The National Memorial African Bookstore was established in 1933 by Lewis Michaux, a Garveyite. Malcolm X gravitated to the bookstore and bookseller, by 1964 giving speeches outside the store. See David Emblidge, "Rallying Point: Lewis Michaux's National Memorial African Bookstore," Publishing Research Quarterly 24, no. 4 (December 1, 2008): 267–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-008-9075-x

Return to Text -

*I deliberately use the non-stigmatizing formulation "person experiencing addiction" rather than the stigmatizing (by essentializing) formulation "the addict."

Return to Text -

It is difficult to ascertain whether the sound level disjuncture happened diegetically or in post-production. In either case, it was not levelled out in post-production, indicating its deliberate use.

Return to Text -

In Making a Promised Land: Harlem in Twentieth-Century Photography and Film (Rutgers University Press, 2013), Paula Massood describes how Harlem had come to be represented through the sociological gaze, first through the photo-text genre, and then in independent films such as The Quiet One, which combined documentary and fiction.

Return to Text -

Massood, Black City Cinema: African American Urban Experiences in Film (Temple University Press, 2011), 85. Massood is discussing flaneur moments in Blaxploitation films, where the main character walks through city streets and leads viewers on a tour.

Return to Text -

Markowitz and Rosner, Children, Race, and Power, 212, drawing from David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder's influential Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse (University of Michigan Press, 2001). https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11523

Return to Text -

Sami Schalk, "Black Disability Gone Viral: A Critical Race Approach to Inspiration Porn," CLA Journal 64, no. 1 (2021): 100–120. https://doi.org/10.1353/caj.2021.0007

Return to Text -

I thank an anonymous reviewer who suggested thinking more deeply about this scene in relation to Schalk's work.

Return to Text -

Roderick Ferguson, Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique (University of Minnesota Press, 2004).

Return to Text -

Mel Chen, Alison Kafer, Eunjung Kim, and Julie Avril Minich, Crip Genealogies (Duke University Press, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478023852-001

Return to Text -

Jina Kim, "Toward a Crip-of-Color Critique: Thinking with Minich's `Enabling Whom?'," Lateral 6, no. 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.25158/L6.1.14

Return to Text -

Alice O'Connor, Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy, and the Poor in Twentieth-Century U.S. History (Princeton University Press, 2009), chap. 9.

Return to Text