This article follows American milk powder through its many iterations and afterlives: as domestic health food, militarized technology in Asia and its diaspora, and as a symbol of modern health on a global stage. What intimacies of empire might we find by following the shifting sentiments around powdered/skimmed milk consumption? Moreover, how does sifting through this minor history allow us to interrogate the politics of body sovereignty and surveillance as it is scaled transnationally. This article argues that an appetite for dairy was encouraged through various national public sensing projects that made eugenics principles accessible for ordinary audiences as an embodied science of the home. Analyzing the military and weight-loss circuits of powdered/skim demonstrates how government agencies, corporations, medical practitioners, home economists, and other public health workers conjured images of healthy nations and abled-citizens through dairy consumption—-often targeting women, children, and racialized subjects as sites of reform through weight management. Bodies that were seen as undesirable–whether too fat or too thin, too sick or too feeble–could be fixed by reforming the appetite. Reading mid-20th century dietetics, U.S. Department of Agriculture archives, and Asian diasporic literature on dairy production and consumption, the case studies in this article elucidate how U.S.-led food literacy and foreign aid campaigns, bolstered by wartime experiments, sought to expand U.S. imperial soft power through wellness technologies. "Milky Appetites" offers a study of desire for national and individual health and wellness as structures of imperialism felt on the body.

This article lingers in the odors of 1920s U.S. dairy creameries—in the stench after fat. Curdles of putrid waste from the creaming process for butter and cheese seeped across ditches, streams, and soiled patches of the American Pastoral. 1 Oozing, rotting, retching, by the 1940s the environmental damage and sensory sore from discharging waste into local waterways was so severe that the dairy industry was forced to find a solution in the form of powdered milk. 2 Skim milk's earlier entry into the market in the 1900s was met with wholesale rejection by the average American palette and used most often in livestock feed and military rations. Five decades later powdered/skim would weave its way into the fabric of American life and transnational bellies: as wellness foodstuffs, foreign aid, and filler in industrial processed foods. Powdered/skim is everywhere—from the expected places like baked goods, milk teas, nutritional supplements, and Nutella to the unexpected such as salad dressings and processed meats. With marketing sleight of hand, the once reviled skim milk has now been domesticated as a health food to strengthen the weak and help the weight-conscious shed their fat since the mid-20th century.

What intimacies of empire might we find by following the shifting sentiments around powdered/skimmed milk? Moreover, how does sifting through this minor history allow us to interrogate the politics of body sovereignty as it is scaled transnationally? This article follows American milk powder through its many iterations and afterlives: as domestic health food, militarized technology in Asia and its diaspora, and as a symbol of modern health on a global stage. I argue that an appetite for dairy (powdered/skim in particular) was encouraged through various national public sensing projects that made eugenics principles accessible for ordinary audiences as an embodied science of the home. By engaging mid-20th century dietetics, U.S. Department of Agriculture archives, and Asian diasporic literature on dairy production and consumption, my case studies elucidate how U.S.-led food literacy and foreign aid campaigns, bolstered by wartime experiments, sought to expand U.S. imperial soft power through wellness technologies and mythos while simultaneously repurposing agricultural waste.

As scholars and activists of the modern/colonial food systems note, offloading food waste onto poor and brown populations under the guise of imperial benevolence is precisely the function of industrial and processed foods. 3 Postcolonial and Asian American Food Studies has given us dynamic tools for thinking through the history of food consumption, appetite-formation, and the (un)making of the self as a not-quite-enclosed subject/object by studying the mundane forms of imperial and state violence via the stomach and the mouth. 4 Scholars have examined a range of what I call militarized foods that rose to popularity throughout Asia and the Pacific during the American century, from Spam to instant coffee. 5 Militarized foods describe both the process by which modern foods enter foodways through military interventions and foreign food aid as well as the unfolding ideology of optimization and vitality that those modern foods signify. For example, while shelf-stable foods such as canned meats and instant coffee were often consumed and reimagined into Global South cuisines out of necessity and survival, powdered/skim milk was marketed as a modern food that could fix unruly bodies and eradicate illness through ingenuity, thereby acting as a conduit for ideas of the optimized able-bodied citizen. My focus on milk and militarism traces how government agencies, corporations, medical practitioners, home economists, and other public health workers conjured images of healthy nations and citizens through dairy consumption and targeted women, children, and racialized subjects as sites of reform through weight management. Bodies that were seen as undesirable–whether too fat or too thin–could be fixed by reforming the appetite.

A Note on Unruly Methods – Food, Fat, and Disability Studies

When I started collecting what can only be described as an alarming number of milk facts for this project, which spans across decades and geopolitical locations, I was often anchored by two cereal bowls from my own girlhood. The school day breakfasts that my dad would fix for me while we were living in Bangladesh in the 90s were an attempt to replicate the foods I was familiar with back home in the States. He would mix a bowl of cereal with powdered milk, water, and sugar. Being a nine-year-old American transplant accustomed to milk coming from plastic gallons in the fridge, I would complain to him about the taste, smell, and texture–asking why we couldn't have normal milk. This is safer than the milk you can get local; it will make you big and strong, he would answer. Years later, when we returned to the U.S. and my brown body kept growing in unruly directions, I was taken to a state sponsored dietician who recommended a breakfast of ¾ cup of Special K cereal with a splash of skim milk. This will help you lose the weight if you're ready to start your life, the dietitian offered.

Powdered milk and skim, which in essence are the same substance, only processed differently, function inconsistently during these moments of bodily regulation. The first involves foreign powdered milk as an agent of purification reliant on ideas about postcolonial hygiene, health, and safety. The second offers skim milk as a training device that eliminates unruly fat from a modern American body in order to build a body and a life worth inhabiting. The unevenness of these material and affective resonances gesture to how the story of dairy and the bodies that consume it cannot be traced as linear or prescriptive. Instead, this article takes flight through vignettes organized as staged encounters– as a touching without foreclosures–which invites us to sit in the mess of our alimentary entanglements.

Fat Studies and Disability Studies have grappled with how bodies become de-naturalized through state and self-governance and are fields uniquely positioned to interrogate how the body acts as archive and index for race and empire across disciplinary fields, geopolitical locations, and political solidarities. 6 As the contributors in this special issue engage with the formation of disability knowledges from social and political peripheries to trouble fraught categories of race, gender, sexuality, and the human, "Milky Appetites" offers a study of desire for national and individual health and wellness as structures of imperialism felt on the body.

As I have written elsewhere, obesogenic researchers and food studies scholars who investigate how social and environmental conditions produce dysfunctional, fat, and sick populations overemphasize the impact of U.S. processed foods on Global South diets. 7 I have argued that a hyperfixation on the spread of fast food franchises and ob*sity mediation in the Global South reinscribes that an authentic native body of the past was inherently thin and abled. The romanticization of an uncontaminated pre-colonial body or the impetus to reform disrupted Global South appetites overshadows how the logics of healthism are also essential to settler colonial practices at the turn of the century.

"Milky Appetites" considers the obvious and the minor of milk and dairying to interrogate these settler practices—from the process of repurposing industrial waste as food in foreign and domestic aid packages, to skim's marketing as a miracle elixir for dieting middle class bodies, and milk's symbolism as a "national food" in a decolonizing world order. The first section traces how milk consumption and production in the 20th century ushers in an embodied language of eugenics that relies on settler environmental practices of extraction and produces modern knowledge around hygiene, gender, and race. This section interrogates how and why milk emerges as an affective object of empire. The second vignette considers the joint vectors and contradicting meanings of powdered/skim milk as it enters transnational foodways and American homes during the mid-century. While the allure of American powdered/skim in the Global South comes from cultivating precise knowledges about hygiene and sanitation as well as a desire to get big and strong, skim was marketed as a miracle weight-loss elixir for American women and an ob*sity-stabilizer for poor populations managed by the state.

Finally, the last section explores the rhetoric around mothering and feeding, specifically in child welfare programs, alongside queer South/Southeast Asian writers Ocean Vuong's milk vignette in his novel On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous and Vivek Shraya's She of the Mountains. This section interrogates how bodies of color and diasporic figures uncomfortably graze against codes of whiteness, citizenship, and thinness which seek to manage intimacies and desire through appetite. This article takes up milk in its many forms–liquid and powdered, material and ideological–to thread the stakes of multiple national body-projects.

Pastoral Eugenics and American Dairy

The digital art installation He Will Not Divide Us was a live stream outside the Museum of Moving Images in Queens, NY that opened in January of 2016. 8 It was designed as a public performance piece that would remain for the duration of Donald Trump's presidency, allowing anyone to walk up to the camera and express themselves. Incited by 4chan users to provoke the left and internet-illiterate media outlets by turning every day, mundane objects into white supremacist symbols– weaponizing hyperbole, exaggeration, and sarcasm– internet white supremacists took over the museum stream to chug gallons of whole milk.

There they stood: bearded, shirtless in the cold, flexing biceps, gathered in a frenzied messy theater as the men cheered and guzzled gallons of whole milk in front of the camera surrounded by a circle of onlookers and semi-participants. Mockingly, they are seen taking turns addressing the lens, close up, growling, laughing, kissing their biceps, lifting one another up in arms, and saying such things as: "hey non-whites, I can do this and you can't," "you may not like it but this is the face of white nationalism," and "Ah, an ice-cold glass of pure racism." 9 The five players at the center and the smirking crowd surrounding them share a recognition for the absurdity of this performance through laughter, belly slapping, and nonsensical chants. The tongue-and-cheek milk-chugging is meant to feel disorienting; it is experienced as non-sequitur incongruence for those not in the know on the origins of the joke and the online discursive vernacular. The joke is in your inability to accept a joke.

After the story was reported on by media outlets, whole milk quickly circulated as an alt-right meme—similar to the likes of Pepe the Frog and the 'okay' emoji 10 —through the typical online channels of 4chan, reddit, and twitter. The protest at the Museum of Moving Images was embroiled in discourse where internet-white supremacists armed themselves with race-science readings of scientific journals about lactose intolerance and the bodies genetically incapable of digesting dairy. In these forums, making much ado about whole milk meant designating skim and soy as racialized, gendered, and sexualized markers of weaker bodies. As seen in the video, one of the men grabs hold of his gallon of milk and is quick to specify: "whole milk–none of that 2% shit." 11

The fat, femme, and Asian body sits at the periphery of these white masculinist performances and the milk myths from which they deride. Skim, often associated with weight-loss, is read as effeminate, meant for those who must shrink to fit into cultural aesthetic norms, something antithetical to an expansively encroaching white heterosexual masculinity. Soy consumption, on the other hand, conjures the Asian and emasculated body. The white supremacist discourse on whole milk cites decontextualized studies about phytoestrogens found in soy assumed to cause a lower sperm count. 12 Entering "the Milk Zone" becomes an ethno-spatial mapping for a narrative of anglo-diets in contradistinction to Asian-diets heavy in soy consumption, thereby consolidating a fantasy of white male virility and supremacy in the face of increasing race anxieties over global capital.

This tension between the joke and the real and what slips outside the virtual chat room presents a vexed target of criticism, that at once demonstrates the limits of representation and the need to develop critical reading practices for modern politics of aesthetics. The meme of whole milk emojis and the theatrical performances of the alt-right might seem like an aberration, a random sequence of events that is merely a reaction to public art and a temporally specific discourse of the now meant to sit as ahistorical in the bowels of the internet. Yet, what would it matter to trace apparitions of old tropes of American nativism through these gestures? What might it mean to locate public feelings of nationalism, belonging, and exclusion through flesh and vernacular?

Our sensibilities around "milk-as-pure" are not merely an inevitable scientific discovery or a cultural-inheritance, but as a systematically curated social, economic, and political force that orders everyday life. In the past decade, a number of monographs by historians and philosophers have tracked the social history of dairying, 13 sanitation, 14 and animal containment. 15 These historical materialist projects make the case for why milk is an important site of inquiry for understanding social life in more than human worlds. 16 In one of the earlier milk monographs that takes seriously the question of whiteness, Nature's Perfect Food by Melanie DuPuis parses through the ubiquitous fantasies of milk's purity by tracing how dairy transformed from "white poison" to natural food at the turn of the century. 17 DuPuis juxtaposes our contemporary perceptions of milk as healthy and natural to how milk was often perceived in the 1800's as a lethal substance for the urban poor because it could be laced with additives like plaster of Paris or paint to achieve a white, creamy texture in instances where the fat was skimmed or where the cows were fed run-off from whiskey distilleries.

During the 19th century, the distaste for skimmed milk was so palpable, and the desire for a creamy, white texture from consumers so strong, that dairy cooperatives adopted these deadly practices of lacing milk supplies with chalk and other thickening agents for decades. DuPuis considers how this transformation from poison to national food begins through milky myths and sentiments around mother's milk, and how shifting relationships to breastfeeding along class lines created a gap for milk to become an indispensable children's food that transformed an ambivalent relationship to dairy into an entrenched one with meaning and feeling that would eventually reach a global scale. 18 Despite the lack of substantial changes to regulations for dairy distribution and sales, the white poison moniker was replaced with something more palatable for Americans: milk was food for our children; milk could secure the future of our nation.

Dupuis argues, "the perfect whiteness of this food and the white body genetically capable of digesting it…exemplifies this story of progress, perfection, and power." 19 Progress, perfection, and power: such mastery signals a visceral genealogy in the construction of white subjecthood as more than an episteme which curates particular tastes or preferences from a geographic locus—or, the collecting of social, political and economic capital afforded to the enlightened liberal human through its fleshy orientations. Rather, mastery over nature acts as the bedrock of whiteness-as-script and diet(ing)-as-culture. E.V. McCullen, a well-known nutritionist in the 1920s who held appointments at leading medical institutes such as John Hopkins (where he ran institutionally funded diet and hygiene experiments on poor, underweight children in Baltimore), makes short order of the link between dairy consumption and the rise of civilized man. Cited by the National Dairy Council in various catalogs and snippets, he writes:

The people who have achieved, who have become large, strong, vigorous people, who have reduced their infant mortality, who have the best trades in the world, who have an appreciation for art, literature and music, who are progressive in science and every activity of the human intellect are the people who have used liberal amounts of milk and its products. 20

Appetites stray to an aesthetic and affective project of bodying which extends the human vis-à-vis whiteness beyond the dermis to the eating, pleasure, sculpting, toning, disciplining of wayward flesh and wild nature. The dairy farm is a project in taming the land while milk consumption registers the body as a tool of social control.

The history of dairying demonstrates how American eugenics plays a vital role in the story of nutritional science and progressive era public health policy. Moreover, the eugenics movement developed various public sensing projects—where observing, quantifying, touching, and consuming helped train the public towards appetites and ways of knowing. One of those projects took place in the theater of the bovine trials. Breeding domesticated animals was a practice in U.S. farms since early European colonial settlements, but it was not until the shifting labor/freedom configurations of a post-emancipation America that livestock breeding became a widespread project of the state. European and U.S. scholars and scientists were engaging in public debates between Darwinists and Malthusians who believed that genetic mutations were random and based on survival (of the fittest) and the neo-Lamarckians who argued that the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain determines the course of evolution. 21 The politics of sentimentalism would see a brief rise in Europe through institutions and social program initiatives as an extension of the colonial administration project at the heart of benevolence in British imperialism. In the U.S., however, progressive era reformers often favored and popularized Darwinists understanding of genetics, capacity, and evolution.

As these debates about breeding and selection over nonhuman and human matters took place in institutions of higher learning, state houses, and scientific communities, their logics were being rehearsed to the American public through livestock educational materials and the Bovine Trials sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. 22 The early 1900s saw an explosion of pamphlets and advice columns created and distributed by researchers at the Department of Agriculture focused on animal husbandry. The most popular and requested pamphlets were written by D.S. Burch titled "Out-Line for Conducting Scrub Sire Trials," "Runts—and the Remedy," and "From Scrubs to Quality Stock." These pamphlets were specifically crafted for layperson audiences. The rhetorical structure of the documents often opened with 'letters to the editor' style advice scenarios featuring questions or stories from farmers, housewives, and up-and-coming businessmen who sought to improve their profits, community infrastructure, or the quality of food people were feeding to their families.

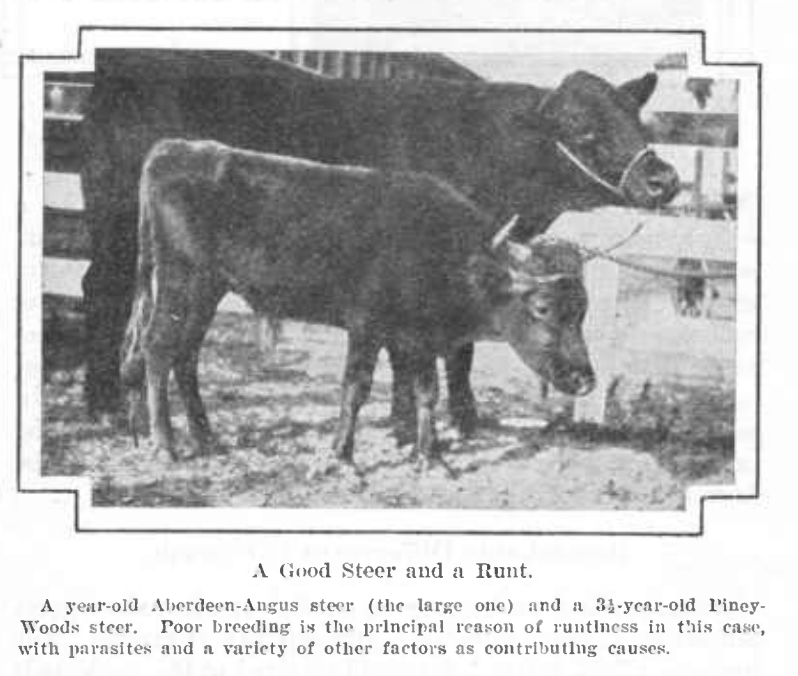

The tone of familiarity worked to make the logics of this emerging science feel accessible. Each pamphlet presented images, like baseball trading cards, with statistics and metrics written in clearly definable terms between the "runts'' and "purebreds." Alongside directives for best breeding practices that would improve communal economies and health, the images depicting "runty bulls'' were an educational tool in training people to recognize signs of ill-breeding. Taking up most of the frame in the "Runts-and the Remedy'' pamphlet is a "runt" and stats such as age, weight, and causes that produced scrub-sires, like "inferior breeding" and "poor feeding." 23 The rhetorical structures associating the visual to metrics of life-management presented modes of recognizing scales of biological difference through healthfulness. Burch believed that "like gravitation and heat, heredity is a definite force that can be utilized to serve those who understand its laws and principles" 24 and sought to make those laws and principles accessible to the American public.

Moreover, though the documents created and distributed by the Department of Agriculture focused on a range of livestock and vegetation, it was cattle-rearing that took center stage in what newspapers and political cartoons would call the Bovine Trials. According to historian Gabriel Rosenberg, the Bovine Trial pamphlets were so popular that people were tuning in across the country. 25 These pamphlets included detailed instructions on the codes of conducts for the play-judges, lawyers, and law enforcement officials, as well instructions on how to engage the humans/animals accused of scrub siring— from courtroom procedurals to the execution of cattle, to the after trial picnic in which the defendant would be served–as sentence and meal. 26 What is most interesting about this state project are the techniques deployed to engage sensory publics. The Bovine Trails were meant to be experienced as a communal affair which culminated in a picnic or banquet of sorts, involving tastes, textures, and sights wedded to the highest exemplar of reason: the rule of law. The slippage between rule of law and man's re-tooling of nature solidifies the sensorial and rhetorical relationship wherein the scrub or runt is a future that can be avoided through the force of mastery. Failure to do so is a failure of the individual in not overcoming the natural world.

Cattle rearing, consumption, and eugenics are more than tangentially related—as 20th century dieticians, agriculturalists, and historians were quick to assert. For example, Ulysses Hendricks, considered an expert horticulturist and historian of his time, wrote:

A casual look at the races of people seems to show that those using much milk are the strongest physically and mentally, and the most enduring of the peoples of the world. Of all races, the Aryans seem to have been the heaviest drinkers of milk and the greatest users of butter and cheese, a fact that may in part account for the quick and high development of this division of human beings. 27

Expelling runts, then, was not merely an economic project that would produce higher and healthier yields of dairy products and meat per capita, but urgently and fundamentally impacted human-species development along racial and ethno-national lines. The echoes of this logic haunt the "Milk Zone" forums that inspired the "Milk Boys" at the Museum of Moving Images, separating those genetically incapable of lactose digestion as less developed both physically and mentally.

The Bovine Trials served, over the course of three decades, as a widely used pedagogical tool to naturalize Darwinist philosophies with everyday habits of thought, ushering in language and iconography for governmentality that the public could witness, participate in, and develop a sensing for through the trial system. It was a theater of taxonomies translated through animal husbandry. The robust debates over public health, nutrition, and technological progress, therefore, were not only happening in formal institutions, but through the common tongue and spectacle of court cases in which average people were encouraged to participate.

…

Milk would provide a playhouse for public speculation and debates over managing hunger and fat throughout the 20th century. Fat Studies scholars have articulated how the boundaries of whiteness were negotiated through body-size anxiety at the turn of the century through a shifting relationship to racialism and labor. 28 Anxious over the flood of new settlers into American port cities, this time period saw a heightened investment in cultivating food knowledges and eating habits supported by scientific method as a way to distinguish the modern white American subject through proper body size and stature. 29 Fat historical scholarship has traced how the cult of slenderness emerged partially as a response to the influx of Eastern European settlers, whose bodies were more stout and round. 30 The investment in slenderness also extended from a colonial relationship to black bodily excess, where fatness came to represent the inferiority of the African to justify their enslavement. 31 Slenderness operated as a visual display of capacity and racialization read through the body. Fantasies around mastering the natural world included learning how to manage body size. Failure to manage fat signaled feeble-mindedness and other forms of degeneracy and dysfunction, similar to how fat bodies are seen as less uneducated and unrefined today. 32

Ideas around fat, race, and bodily management would manifest in a myriad of forms through dairy production and advertising. With the increased production, transportation, and consumption of dairy products from rural farms to urban centers, the overabundance of skim and whey run-off, typically recycled as livestock feed for smaller scale family farms prior to monoculture farming practices, was discharged into local waterways. 33 Though the practice of dumping industrial farm waste into streams and rivers was not a new one, by the 1940s the environmental damage and sensory sore was so severe that, pressured by environmental advocacy groups and consumers nauseated by the fumes, creameries were forced to take action. The dairy industry was facing a problem of appearances that broke faith with a centuries-long project of cultivating its parabolic goodness through joint processes of racialization and occupation.

The unsanitary and unsightly practices of the creameries began to undermine the wholesomeness, purity, and whiteness of dairy in the national imaginary, a mythologizing made possible by disappearing labor—from lactating mammals (both human/nonhuman), to migrant dairy workers, to the industrial infrastructures of production and transportation. With such a material legacy, the odors of the 1920s U.S. creameries presented a vexed political-ecological entanglement that posed more than a problem of waste disposal and management and would, therefore, require a re-education of appetites and senses. Ernst Kelly, an employee of the National Dairy association in 1919, noted how despite a national intolerance for waste during the interwar period Americans simply would not consume skim milk. 34 The difficulty of reconstituting the milk solids into liquid form and the negative associations with skim—between its vernacular use as lacking substance and therefore nutritional density and its primary function as livestock feed— made it particularly unappetizing. Chemurgists attempted to rebrand dairy discharge in a number of ways with varying degrees of success, as fillers in processed foods, as plastics, and even as casein fabrics for Avant Garde fashions.

Headway was made in the 1920s and newspapers began reporting on the perfected technological marvel of powdered/skim. A New York Times article from June 13, 1920 titled "Milk Powder Perfected," 35 reported that the United States Public Health Service in Boston had concluded successful experiments with dried milk powder on children in the tropics. Surgeon General H.C. Cummins is quoted saying:

Babies of the tropics are now assured of a supply of milk as wholesome as that which comes from the finest American Dairies. Aside from making possible the saving of thousands of babies' lives through[out] the world, it will enable the dairymen to use profitably large quantities of milk which formerly have been wasted. 36

Babies of the tropics acted as a laboratory for powdered milk's digestibility in bellies and the marketplace on the global stage, crafting a rhetorical motif whereby American innovation in technologies of food production are sutured with the project of the human(itarian). On the other side of the same coin, 1500 underweight school children in Baltimore were fed powdered/skim as well. The experiment, directed by E.V. McCollum, included monitoring children in their homes, "regulating hours of their sleep, and selecting their food." 37 These two projects were representative of public health research in the mid-20th century that emphasized how the lives of poor communities (of color) were meant to be surveilled and re-matriculated into more appropriate appetites and behaviors.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture and Bureau of Home Economics created a series of campaigns to spread awareness of the uses of skimmed milk that leaned into its health merits from a scientific standpoint. One such report in 1934 from the popular "Aunt Sammy" radio program, a daily, fifteen minute segment that showcased the latest tips for rural American homemakers, focused on transforming skimmed milk's image as "the step-child in the food family–misunderstood, neglected, scorned, slighted and –wasted" into a healthy, desirable food for the whole family. 38 The program focused on supplying nutritional facts, urging homemakers to shift their long held feelings about the unpleasant taste and texture of skimmed milk to instead think about economic foods and nutrient content. This content shift would lay the foundation for how skimmed and powdered milk would make its appearance during World War II and its aftermath.

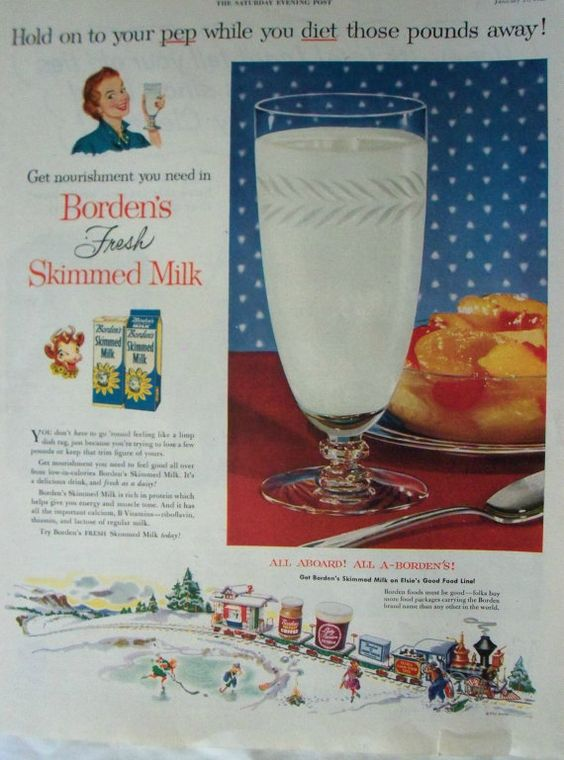

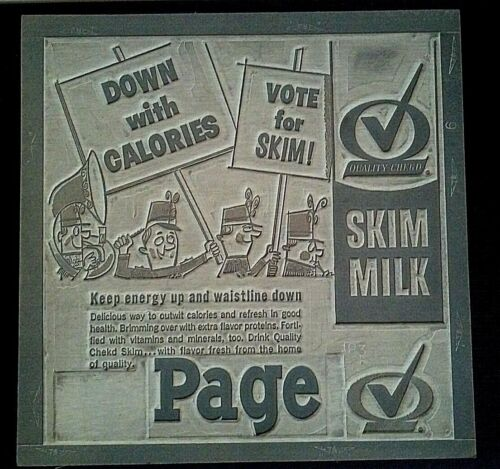

At the end of World War II, as the U.S. and its allies conducted starvation and re-feeding studies on human test subjects to determine the best course of action for offering food relief to starved European populations, 39 dairy corporations diverted all other uses of skim to its food production. While this might have posed a problem in the post-war period because Americans were still unwilling to consume skim milk, milk advertising began crafting a fantasy of skim's potential for weight loss and maintenance. Where previous dairy advertisements attempted to target mothers and their children, new marketing techniques emerged that focused on how skim could help women achieve that perfect slender physique. Shifting from iconography about nourishing the home and family, skim consumption became associated with healthy weight-loss, attractiveness, and heterosexual romance. Pulling from familiar public sentiments about the fear of fat-racial contagion, fat-free dairy products began crowding grocery shelves. While the U.S. and USSR engaged in a battle for the title of social and economic global superpower, the nuclear family emerged as a symbol of U.S. exceptionalism and managing bodies became the project of white American women. 40

Skim milk would gain traction amongst American women through an association of low-fat and low-calorie foods as necessary to maintain good health through a slim figure. Dairy corporations benefited from the work of home economists who were crafting a lexicon and image of the New American woman as a home manager responsible for curating healthy modern appetites through knowledge about nutritional science. 41 In a Page Milk Company letter press that was in use from 1950 to 1969, skim is advertised as a low-calorie dairy product that will "keep energy up and waistlines down," and that consuming skim is a "delicious way to outwit calories." The emphasis on "outwitting" the calorie, or being clever enough to eliminate fatness emphasizes the modern American woman as a manager of home and body. The rise of calorie counting allowed for skim milk to evolve from its previous image as a waste product lacking in nutrition to a valuable food substance that could keep the body thin.

Proto-Illness and the (Trans)National Body

American milk powder would have many afterlives in Asia and the Pacific—as a memory of war time hunger and a key ingredient in the transformation of global delicacies (such as Taiwanese boba milk tea in the 1980s). Powdered milk was introduced into Asian food systems during World War I and would become a staple in every U.S. military intervention thereafter. In Grace M. Cho's exquisite hybrid text, Tastes Like War: A Memoir, Cho strains a daughter's grief through a mother's madness and begins with a powdered milk story. Cho situates how aging and illness, love and loneliness make home in the stomach, through the appetites that tether the tongue to global histories in recalling the uneasy dynamics left in the wake of her Korean mother's Cold War traumas. The memoir opens with scenes from the last few years of Cho's mother's life. Cho describes the small suite her brother and sister-in-law built for their mom with a mix of affection and anxiety and a conversation she had with her mother about her lack of appetite and emaciating body:

"Mom, are you getting enough to eat?" I asked.

She nodded.

"What about protein?"

She nodded again, then snorted.

"They got me powdered milk."

"Oh yeah?" I said, feigning surprise.

She became quiet as if she had already lost her train of thought and was deep in some hallucinatory reverie.

"I can't stand the taste of it," she said. "Tastes like war." 42

This moment opens a jarring remembrance sequence for both mother and daughter, wherein technologies of militarism and empire stretch to the viscera of the stomach and tongue. Cho recalls the first time she began thinking through memory and the stomach: during an elementary school project where students were asked to make a family tree. In asking her mother about her family history, she learned that her grandfather died from stomach cancer and her mother had another sister who also died from stomach cancer. Though the official death certificates indicated "natural" causes of death outside of the immediacy of war's technologies: bombs, guns, and containment camps, the stomach maps the attendant assemblages of war through food ecologies and social welfare infrastructure. Cho traces the ephemera that is the taste of war, a hallucinatory reverie that remembers powder milk as actant and extension of the U.S. military. The primacy of her mother's memory marks an archive of war-time bodies as they are carved out by the force of food and aid.

How did skim transform from reviled food waste to innocuous health food? By World War II, milk powder had ascended to the national and global stage despite a continued distaste by the American public. As Kendra Smith-Howard meticulously details in her history of mid-20th century dairy, "skim milk entered World War II before American soldiers did. The U.S. secretary of agriculture asked for expanded production from dairy farmers in July 1941, months before the attack on Pearl Harbor." 43 Skim milk was meant to be America's contribution to the war effort and made sense as a humanitarian aid technology in the registers established by food scientists, public health officials, and dairy lobbyists at the time. Through the distribution of milk powder, skim acted as a material agent of war that warned of America's presence even in its absence of soldiers and in this moment transformed from an unwanted foodstuff into a desirable modern food. As a representation of U.S. interests— that dissolves the boundaries between humanitarian aid and U.S. military intervention—skim milk acted as a precursor for understanding modern biopedagogies of bodily and dietary surveillance.

India's Operation White and China's 1980's post-Mao dairy boom demonstrate that creating a dairy-consumer class in Asia required an amalgamation of biosocial workings: the use of transnational NGO milk powder for developing middle class stomachs for dairy, the rise of milk-and-motherhood national imagery, and the dissemination of global nutrition science discourse about citizen-bodies and digestion. Dairy development measures both the growth of a nation's economic capacity on the modern global stage as well as how well its citizen-bodies can fight the stigma of lactose intolerance as a proto-disease affecting the Asiatic figure. The fantasy of the citizen-body is policed by and created through the promise of belonging and able-bodiedness tempered by a rapid increase in dairy consumption. U.S. powdered/skim would act as the first point of entry –an intermediary–for Asia's appetite for dairy as more than a specialty health food for infants and elderly people. 44

Verghese Kurien, known as the "Milkman of Indian" and the "Father of the White revolution," envisioned Amul brand to operate as an umbrella organization for a dairy co-operative that would bring together a collection of rural farmers across the country to standardize the production, sale, and distribution of their dairy products. 45 India's Operation Flood or "The White Revolution" was a national dairy modernization project that included multiple stages that sought to develop India from a "milk deficit" country to a surplus one. 46 The first stage utilized powdered/skim milk from European and U.S. foreign aid packages to create and sustain consumer demand for cow-milk. 47 This required targeted advertisements to a middle-class consumer palette. Amul was particularly successful in their bi-lingual Hindi/English advertisements that featured mothers and their children happily consuming the powdered/skim milk products. Further, the ads complemented traditional cooking while emphasizing the innovation of powdered milk–as a stabilizing ingredient that was safer than fresh dairy and texturally better.

Powdered/skim was seen as a cleaner, more effective alternative to the fresh milk available in urban centers as the supply of fresh dairy was inconsistent in the city centers. 48 The second part of the plan was to bolster dairy sheds and scale up production with the use of European cattle that rendered higher yields–at the expense of decimating native cattle populations. 49 Simultaneously, the cooperative created a transportation grid that allowed for products from rural dairy farmers to reach urban populations. As the national dairy cooperatives and wealthy elite designed a national grid system with roads and railways linking rural farms to urban centers and processes of cooling and refrigeration throughout, the final stage of the plan was to invest in dairy infrastructure, from veterinary training and breeding techniques to feed research and education. 50

Despite critiques from environmentalists and economists about the project's inefficacy at helping the urban poor and its costly environmental impact, 51 Operation Flood supporters continued to claim that it was an unmitigated success. At the completion of the multi-year project that began in 1970 and ended in 1996, Kurien said in a speech: "Over the course of Operation Flood, milk has been transformed from a commodity into a brand, from insufficient production to self-sufficient production, from rationing to plentiful availability, from loose, unhygienic milk to milk that is pure and sure, from subjugation to a symbol of farmer's economic independence, to being the consumer's greatest insurance policy for good health." 52 The quality of life for rural poor populations did not figure into national uplift, while the language of hygiene, purity, and economic independence that Kurien characterized as part of the national dairy project would remain a container for populist affects.

…

As China opened its market borders in the 1980s after the death of Mao Zedong, powdered/skim milk began appearing in local shops as national agencies encouraged families to wean their children onto dairy from a young age in order to develop an appetite and a gut capable of digesting this "modern" food. 53 Within less than a 30 year period, a population with a 92 percent rate of lactose intolerance would become the world's second largest consumer of dairy. How and why did this happen? Historian Thomas D. DuBois argues that, despite popular historical opinion, China did have a long history of dairy consumption in certain provinces that trace moments of contact and trade between continents. He goes on to describe the processes by which modern China embraces dairy and cattle rearing, one such site being through an appeal to good health:

The appeal to good health added to milk a second layer of symbolism [aside from mother's nourishment], one that in China's fraught political climate was interpreted equally as the health of the individual and the health of the nation. In Meji Japan, many among the reforming elite had come to see an animal-based diet as the secret of Western physical and mental prowess, and advocated as a national priority the expansion of the dairy herd and dissemination of dairying skills and cooperatives. China was not far behind. 54

Mao Zedong, having been trained as a physical education student, often focused on the relationship between the strength of the body and the strength of the nation. 55 In one of his earliest student papers he writes, "The Country is being drained of strength. Public interest in martial arts is flagging. The people's health is declining with each passing day…Our country will become even weaker if things are allowed to go unchanged for long." 56 Milk finds its purchase in the Chinese imagination as the secret to Western girth and strength by pulling at existing beliefs about food, nutrition, body size, and national well-being. Hilary A. Smith notes that these beliefs were cultivated on official institutional levels through transnational organizations and government agencies where "the moralizing message that responsible citizens drink milk, and responsible officials promote it, remains strong. Milk's status as a morally good food continues to be reinforced by influential bureaucracies such as the United Nations, by patterns of trade and food aid, by the continuing growth of the Chinese dairy industry, and by scientific discourse that frames lactose intolerance as proto-disease." 57

In a 1995 article for the Sociology of Health and Illness journal, David Armstrong investigated the phenomenon of the new surveillance medicine in the 20th century and how that impacts identity formation. Armstrong writes: "the fundamental remapping of spaces of illness…[which] includes the problematisation of normality, the redrawing of the relationship between symptom, sign and illness, and the localisation of illness outside the corporal space of the body," fundamentally changes how people think about the problematization of the normal. The idea of proto-illness describes the "risk experience" or what Mikko Jauho describes as the idea that even chronically healthy people can be viewed as "patients-in-waiting." 58 Smith notes how the language of pathology developed to describe healthy adult bodies– "lactose intolerance, lactase deficiency, lactase insufficiency, hypolactasia. That lactose production usually ceases after infancy was a discovery, in other words, but 'lactose intolerance' as a medical problem was an invention." 59 Lactose intolerance was mapped as a significant marker of proto-illness in the 20th century, where the discovery of a normal and interesting variation in human biology became framed as a medical condition that required treatment to ensure the production of healthy-citizen bodies.

Following the rise of dairy production and consumption in industrializing nations is an anxious discourse about the consequences of the underdeveloped world's burgeoning taste for cow meat and milk. Media articles and public debate speculate on the environmental impact and fixate on the changing body chemistry and size of Global South peoples. For example, there has been a surge of articles about China's bottomless quench for liquid and powdered milk in recent years, ranging from a focus on mass imports of baby formula from Australia and New Zealand after several infant mortalities from tampered domestic products to heated debate over the carbon and methane emission increases via national Chinese dairy cooperatives. 60 Articles about China's appetite for milk paint a picture of a rapidly industrializing nation that articulates its sense of modernity through the appetite for traditional Western diets and narrativizes Chinese appetite for dairy as a feeling about milk as both a natural and modern food that can transform the body.

In The Guardian's piece titled "Can the World Quench Chinese Bottomless Thirst for Milk?," Felicity Lawrence details China's development history in a post-Mao national order where milk entered the cultural lexicon as a Western aesthetic long before Chinese people consumed it. Lawrence's piece essentially argues that the appetite for dairy developed from an appetite for Western fitness, muscularity, and height that stemmed from multiple factors including the broadcasting of the 1980's Olympics on home televisions and the affordability of refrigerators. She ends her article on a speculative note that stages the dire conditions of environmental degradation and rapid industrialization:

If China's demand for dairy triples again by 2050, as projected by state targets and some financial analysts, the typical Chinese person would still consume less than half of what the average European gets through. Given the size of its population, that nevertheless poses an increasingly urgent question: how many cows, and other livestock, can the world actually sustain? 61

This narrative of industrializing nations expanding too fast (in population, appetites, and body size) alerts us to an exacerbating speed of environmental collapse entrenched in ideas of bodying. Bypassing the West's own responsibilities for large scale, catastrophic ecological violence since 1492, such an analysis of ecological danger (even if justified), is the very basis of Western environmental paternalism that seeks to obscure its own unethical inaction by stoking fears of containing the excessive racial other. This narrative plays out very specifically across fatness and environmental damage. The circuits of the U.S. empire and violence remain largely invisible to most consumers of dairy. Instead, the complex feelings arise from uncomfortable attachments between the self and governance.

Minor Histories & Minor Feelings

In 2014, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) finalized a decades-long project to make 1% and non-fat skim milk the only dairy options available for WIC recipients.[lv] WIC is a supplemental food program for low-income mothers that offers vouchers for pre-approved foods to parents who have completed clinic weigh-ins as well as video courses on nutrition and childcare. Along with tracking weights for both mothers and their children, recipients are required to watch infomercial style videos to re-train parents in the early stages of child rearing and development around eating habits in order to produce healthy citizens and reduce ob*sity populations within working-poor communities. Though a number of parents and journalists have questioned the actual nutritional value of the hodgepodge of foods available through WIC—such as requiring parents to take home anywhere from 46-68oz of sugary fruit juices as a substitute for federally mandated fresh fruit allowances—the organization maintains that it is invested in a healthy America.

The announcement that WIC would only allow the purchase of 1% or non-fat milk came with little ceremony—inched forward by the desire to "end ob*sity within the next generation" while simultaneously bolstering stagnating national dairy economies—it aligned with a state commitment to stop the terror within from spreading throughout poor communities seen as more inherently susceptible to obesity-fat. Years earlier, in the midst of the "War on Terror," former Surgeon General Richard Carmona warned that obesity, if left unchecked, would be a greater threat to United States national security than terrorism: fat was the terror within. Later, former First Lady Michelle Obama would state that childhood ob*sity was not merely an economic or parental issue, but a national security threat that would impact the future of global safety. 62 In such a rendering, the fat body is at once the site of catastrophic global damage in the national imaginary and the willful, complicit, and victimized perpetrators of bodily disfiguration and dysfunction.

Policing women's reproductive health and feeding children has a genealogy for mothers of color in particular. Breast-feeding, even in our contemporary epoch, is a site of mothering-anxiety fraught with shame, guilt, obfuscation, and gender/race/class expectations. In thinking about the complex permutations of gendered care-giving and feeding through (literal) flesh economies, it is apparent that colonial socialities (mis)aligned class and race through feeding and child rearing; many of these techniques inform modern nutritional assistance programs and food educational materials today. Surveilling motherhood through economies of feeding demonstrates that what a mother chooses to feed her child is more than simple nutrients.

WIC recipients would not be the first beneficiaries of public assistance to encounter this non-fat dairy consumption mandate, despite the evidence of skim's healthfulness being quite thin. Programs like the Special Milk and Head Start Program, which offer free and reduced school meals domestically, as well as the hundreds of tons of powdered/skim milk shipped in foreign aid packages for children and families annually since the mid-20th century, also reflected the same philosophies around fat consumption and containment. These biopedagogies of dietary/ bodily surveillance and self-knowing uncritically suture an understanding of public good with the eradication of fat.lvii WIC's final rule change was the next logical step in the modern state's efforts to secure a global public health agenda and U.S. prosperity through the governance of the racialized and working-poor, of containing the threat of racial, fleshy excess by claiming the gut.

In Ugly Feelings, Sianne Ngai charts the critical productivity of dysphoric affects–what she calls minor feelings, such as envy and paranoia–as ambivalent orientations which both highlight and condense class resentiment. 63 She argues that while dysphoric affects are the very fuel of a capitalist society (i.e. how scarcity and competition both create and necessitate feelings of fear, anxiety, and envy), they also reveal how desire takes form through social and psychic processes. Moving from reading a materialist and minor history of dairy into the realm of milk's minor feelings of (dis)comfort, this section turns toward the lingering affects of American appetites on queer diasporic bodies. Practices and policies that regulate and encourage dairy consumption for populations deemed in need of reform—through various foreign and domestic aid projects— anchor themselves in how bodies come to recognize belonging in place and time. Everybody has a milk story and those stories often map feelings of comfort/discomfort, safety, and home. I sit with how discomfort manifests in the literary milk vignettes in Ocean Vuong and Vivek Shraya's queer South/Southeast Asian experimental writings. For diasporic figures and poor bodies (of color), consuming milk can be entrenched in a desire for belonging and normalcy— means of fixing the body so that it might be able to survive in a future not meant for many of us.

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous is a genre-bending novel from Vietnamese American writer Ocean Vuong. Formatted as a series of letters to little dog's "ma"—described as a woman with no soft edges who moves from a refugee camp in the Philippines to public housing in Connecticut—Vuong explores the deep gnashes that grow in the aftermath of militarism, migration, and attempts at assimilation for diasporic subjects. The text is riddled with sharp pauses filled with moments of rage, fear, loneliness, and misunderstanding. Milk appears punctuated throughout little dog's letters—in tall glasses, in pools on the tile floor, on receipts, and in plastic bags that he carries home from the corner store. It's a quiet symbol of reaching towards an American life even as that fantasy is constantly re-negotiated and in flux. In one letter, little dog writes to his mother about that time on the school bus when he was nine and a group of young white boys began harassing him. He recalls sitting on his own and the presence of his yellow body breaking the otherwise white landscape when boys on the bus began harassing: "Don't you ever say nothing? Don't you even speak English? Say something. Say my name like your mom did last night." That night, after telling his ma what happened, there was no comfort offered, just the directive to never let anyone do something like that again. He writes:

The next morning, in the kitchen, I watched as you poured the milk into a glass tall as my head.

'Drink,' you said, your lips pouted with pride. 'This is American milk so you're gonna grow a lot. No doubt about it.'

I drank so much of that cold milk it grew tasteless on my numbed tongue. Each morning after that, we'd repeat this ritual: the milk poured with a thick white braid, I'd drink it down, gulping, making sure you could see, both of us hoping the whiteness vanishing into me would make more of a yellow boy.

I'm drinking light, I thought. I'm filling myself with light. The milk would erase all the dark inside me with a flood of brightness.

'A little more,' you said, rapping the counter. 'I know it's a lot. But it's worth it.'

I clanked the glass down on the counter, beaming. 'See?' you said, arms crossed. 'You already look like Superman!'

I grinned, milk bubbling between my lips. 64

This scene is brimming with anxious feeling and want. Anxiety over mothering/feeding, the hardness of refugee positionality, and the forms of limited protection broken people can offer the ones they love. Ma cannot afford vulnerability and cannot offer little dog a soft kind of comfort. Instead, she arms in the ways she knows how, by reaching towards American milk. American milk, that touched the tongue of Asia and the Pacific through its military circuits, is the solution that little dog's mother has for his difference. American milk rings like a tinkering little anthem, identifying uneven scales of power that western foods hold in the modern global food system. The legacy in which milk production and consumption indexes the health of a nation is felt in fervent belief that little dog can alter his innermost self—a self marked as damaged because of his small, frail body and queerness through yellowness. American milk, the substance of modernity and progress, has the capacity to transform. Like my earlier reading of the white supremacist chugging gallons of whole milk, milk for little dog and his ma will wash him in masculinity; milk will temper his queer desires and fashion him into a big and strong man. Attempting to bridge a gap slashed open through borders and kinship, mother and son rehearse this ritual of drinking milk, filling his small, yellow body with the white milky myth of American masculinity.

Chugging the glass under his mother's watchful eye symbolizes the curation of a proper kind of body. That beaming boy clanking his glass on the table breathes in relief at finding futurity in a world he where he doesn't fit. The logics of milk are not only inherited through our literal gut microbes but are offered to us as fragile and feeble forms of protection from generation to generation. For those who can, becoming big and strong or thin and attractive are meant to make one's life easier in an anxious world ordered through racial capitalism and body hierarchies. It is neither about condemning nor condoning how people relate to their bodies, but about sitting in the discomfort of their wanting—that wanting is a measure of recursively recurring cultural moments. Little dog and his mother wanting the milk to rearrange his core being into someone that fits-in is soaked in histories of empire that construct able-bodiedness—as abled to do, abled to belong.

The maternal operates as a straightening device, revealing the racial and gendered dynamics of childrearing as one entrenched in producing and maintaining an abled-body. In the case of little dog, his ma hopes to minimize the discomfort he is made to feel for his difference amongst the other school children. As little dog's belly swells with glass after glass, we are made to understand that some discomforts are worth inhabiting. The maternal comes to mediate which ugly feelings the queer yellow body must endure.

This relationship between the maternal and the bodily management of the unruly brown child appears throughout Vivek Shraya's multisensory illustrated novel, She of the Mountains. Blended through reimagined Hindu creation myths and the creation myth of the diasporic "self," the novel renders, achingly, the flows of gender, sexuality, and attraction. The protagonist's sexuality and body are constantly being ordered through binary logics: gay/straight, male/female, and thin/fat. The central tension of the text expands what queer life and love can look like alongside those binaries. The protagonist doesn't offer the readers a name for himself, and instead gives us identity markers (brown, gay, fat) that his body collects over time. The moments in which the self and body arrive as subject are through sticky relations primarily in comparison and contradistinction from white kids in the neighborhood or the straight boys he grew up around. The protagonist is made to feel the discomfort of his body through the perceived normalcy of other bodies. In one story, he recalls his mother's fear and anxiety over their perceived gayness and the threat of their unmanageable appetites:

When you were little, I was so worried you would end up fat like your dad, fat like an elephant.

He had often heard about his fat childhood from his mother, about how his auntie had nicknamed him "butterball" when his ten fingers became so plump that they joined into two lumpy mounds at the base of his arms. His mom had panicked and taken heed of a co-worker's advice that she switch his milk from homo to two-percent. Although his fingers separated again, her fear loomed over his teenage years, evidenced by her frequent descriptions of his childhood body as subtle warnings for his adult body. 65

His fat childhood is an experience narrated to him through the mother. There are two monstrous terrors that his mother fears most: the animality of his father's fat living on in his future adult body, and the queerness that comes to live in the folds of his fatty arms and plump fingers. A milk free from fat, according to his mother's coworker, would change his body and tame his appetites. The legacy of skimmed milk's normative iconography around healthfulness and thin-heterofuturity act as a promise for the protagonist's fat, diasporic, queer body. Shrink into an easier future, a future in which you can reach towards humanness. "From homo to two-percent" holds sentiments and logics of racial formation and governance.

WIC's final rule change and these queer diasporic writings act as examples for the legibility of the social history of dairying and it's lingering affects on kinship and bodily relations, making visible that which has become internalized and naturalized about our phobic affinities to fat and how such sentiments are upheld through contradictory relationships to food, gender, and the racialized other.

…

Conclusion: Sensing Horizons

The visceral force of American dairy enters and influences a grammar of nation, modernity, whiteness, able-bodiedness, heterofuturity, and thinness as markers of a healthy future. Images and vocabulary around eugenics and scientific progress morphed through the dairy dramas of the Bovine Trials and public health projects targeting poor children and children of color for repurposing agricultural waste in the 20th century. The multiple registers of dairy consumption and national and class body politics bears witness to appetites and habits of empire that seal themselves as empirical fact by training us to recognize and re-collect quantifiable data on health status as representative of a nation and its people's capacity. These various modes of common sensing—felt through an aesthetics of infrastructure—surround us today from white supremacist milk chugging, to gendered advertisements for fat-free dairy products, to domestic and transnational knowledge production around children's nutrition. In highlighting the curatorial nature of that surrounding and denaturalizing our pull towards milk as anything but common, we might lean into how bodies can craft a horizon of possibility and how appetites and sensations shape the directions we move towards.

This piece of unruly writing has been nurtured by many hands and I am grateful it has found co-conspirators in this special issue of Disability Studies Quarterly. Thank you to co-editors Kelsey Henry, Sony Coráñez Bolton, and Anna LaQuawn for being such dedicated and careful readers. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Heidi Amin-Hong, Keva X. Bui, Sam Ikehara, Nicole Richards-Diop, Huan He, Ly Thuý Nguyễn, Neetu Khanna, Kyla Wazana-Tompkins, Dorinne Kondo, and Matilda Cohen for championing the ambitious scope of this research in its earliest stages. Many thanks to the incredible thinkers at the "Eggs, Milk, and Honey: Law and Global Bio-Commodities" workshop at Western Sydney University in 2018 where I received valuable feedback on the very first draft of what would later become this article. All faults are my own.

Works Cited

- Atkins, P. J. "OPERATION FLOOD: DAIRY DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA." Geography 74, no. 3 (1989): 259-.

- Atkins, P. W. Liquid Materialities: A History of Milk, Science, and the Law. Critical Food Studies. Farnham, Surrey; Ashgate, 2010.

- B S Baviskar. "Operation Flood: Reviving Debates." Economic and Political Weekly 46, no. 5 (2011): 5–5.

- Baviskar, B. S. "Milkman of India." Edited by Verghese Kurien. Economic and Political Weekly 41, no. 24 (2006): 2455–57.

- Bellur, Venkatakrishna V., Saraswathi P. Singh, Radharao Chaganti, and Rajeswararao Chaganti. "The White Revolution—How Amul Brought Milk to India." Long Range Planning 23, no. 6 (December 1990): 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(90)90104-C

- Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

- Cho, Grace M. Tastes like War: A Memoir. First Feminist Press edition. New York, NY: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2021.

- Choudhury, Athia N. "The Making of the American Calorie and the Metabolic Metrics of Empire." Journal of Transnational American Studies 13, no. 1 (2022). https://doi.org/10.5070/T813158578

- —- "Genealogies of Excess: Towards a Decolonial Fat Studies." The Fat Studies International Handbook, Edit. Caitlin Pause and Sonya Renee, Routledge. (2021)

- Deka, Ram Pratim, Johanna F. Lindahl, Thomas F. Randolph, and Delia Grace. "The White Revolution in India: The End or a New Beginning?," September 2015.

- Dirth, Thomas P., and Glenn A. Adams. "Decolonial Theory and Disability Studies: On the Modernity/Coloniality of Ability." Journal of Social and Political Psychology 7, no. 1 (April 5, 2019): 260–89. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v7i1.762

- Doornbos, Martin, Pieter van Stuijvenberg, and Piet Terhal. "Operation Flood: Impacts and Issues." Food Policy, Food Policy, 12, no. 4 (1987): 376–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-9192(87)90009-1

- DuBois, Thomas David. "China's Dairy Century: Making, Drinking and Dreaming of Milk." In Animals and Human Society in Asia: Historical, Cultural and Ethical Perspectives, edited by Rotem Kowner, Guy Bar-Oz, Michal Biran, Meir Shahar, and Gideon Shelach-Lavi, 179–211. The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019.

- DuPuis, E. Melanie. Nature's Perfect Food: How Milk Became America's Drink. New York: University Press, 2002.

- Erba, Eric M., and Andrew M. Novakovic. "The Evolution of Milk Pricing and Government Intervention in Dairy Markets," E.B., 1995.

- Farrell, Amy Erdman. Fat Shame: Stigma and the Fat Body in American Culture. New York: University Press, 2011.

- Fraser, Laura. "The Inner Corset: A Brief History of Fat in the United States." New York, USA: New York University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814777435.003.0006

- Fuller, Frank, Jikun Huang, Hengyun Ma, and Scott Rozelle. "Got Milk? The Rapid Rise of China's Dairy Sector and Its Future Prospects." Food Policy, Food Policy, 31, no. 3 (2006): 201–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2006.03.002

- Garzo M. F., Zandi, H. (2011) The modern/colonial food system in a paradigm of war. Planting Justice https://live-ethnic-studies.pantheon.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/24/mcfspw.pdf (last accessed October 12, 2023)

- Gewertz, Deborah B., and Frederick Karl Errington. Cheap Meat: Flap Food Nations in the Pacific Islands. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

- Grech, Shaun, and Karen Soldatic. "Disability and Colonialism: (Dis)Encounters and Anxious Intersectionalities." Social Identities 21, no. 1 (January 2015): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2014.995394

- Ho, Jennifer Ann. Consumption and Identity in Asian American Coming-of-Age Novels. Studies in Asian Americans. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Hu, Dinghuan, Frank H. Fuller, and Thomas Reardon. "Impact of the Rapid Development of Supermarkets on the Dairy Industry in China, The." Staff General Research Papers Archive. Staff General Research Papers Archive. Iowa State University, Department of Economics, January 1, 2004.

- Imada, Adria L. "A Decolonial Disability Studies?" Disability Studies Quarterly 37, no. 3 (August 31, 2017). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v37i3.5984

- Janer, Zilkia. "(IN)EDIBLE NATURE: New World Food and Coloniality." Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (March 2007): 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162597

- Jauho, Mikko. "Patients-in-Waiting or Chronically Healthy Individuals? People with Elevated Cholesterol Talk about Risk." Sociology of Health & Illness 41, no. 5 (2019): 867–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12866

- Jia, Xiangping, Jikun Huang, Hao Luan, Scott Rozelle, and Johan Swinnen. "China's Milk Scandal, Government Policy and Production Decisions of Dairy Farmers: The Case of Greater Beijing." Food Policy 37, no. 4 (2012): 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.03.008

- K N Nair. "White Revolution in India: Facts and Issues." Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 25/26 (1985): A89–95.

- Knight, G. Roger. Commodities and Colonialism: The Story of Big Sugar in Indonesia, 1880-1942. BRILL, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004251090

- Ku, Robert Ji-Song, Martin F. Manalansan, and Anita Mannur. Eating Asian America: A Food Studies Reader. New York, UNITED STATES: New York University Press, 2013.

- Land, Nicole. "Fat Knowledges and Matters of Fat: Towards Re-Encountering Fat(s)." Social Theory & Health 16, no. 1 (February 2018): 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-017-0044-3

- Levine, Deborah I. "The Curious History of the Calorie in U.S. Policy:" American Journal of Preventive Medicine 52, no. 1 (January 2017): 125–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.08.012

- Mannur, Anita. Intimate Eating: Racialized Spaces and Radical Futures. Durham: Duke University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478022442

- Mintz, Sidney W. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

- Mitchell, David, and Sharon Snyder. "The Eugenic Atlantic: Race, Disability, and the Making of an International Eugenic Science, 1800–1945." Disability & Society 18, no. 7 (December 2003): 843–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759032000127281

- Mollow, Anna. "Disability Studies Gets Fat." Hypatia 30, no. 1 (2015): 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12126

- Morris, Jonathan. Coffee: A Global History. Reaktion Books, 2018.

- Ngai, Sianne. Ugly Feelings. First Harvard University Press paperback. Cambridge, Mass. London: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Nimmo, Richie. Milk, Modernity and the Making of the Human: Purifying the Social. Culture, Economy and the Social. London; Routledge, 2010. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203867334

- Nützenadel, Alexander, and Frank Trentmann. Food and Globalization: Consumption, Markets and Politics in the Modern World. English ed. Cultures of Consumption Series. Oxford; Berg, 2008. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350047655

- P Sarveswara Rao and B Ramachandra Reddy. "An Overview of Dairy Industry in India." Productivity (New Delhi) 55, no. 1 (2014): 43-.

- Padoongpatt, Mark. Flavors of Empire: Food and the Making of Thai America. American Crossroads. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520293731.001.0001

- Pausé, Cat, Jackie Wykes, and Samantha Murray, eds. Queering Fat Embodiment. Queer Interventions. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2014.

- Puar, Jasbir K. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Anima. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822372530

- Rosenberg, Gabriel N. "No Scrubs: Livestock Breeding, Eugenics, and the State in the Early Twentieth-Century United States." Journal of American History 107, no. 2 (September 1, 2020): 362–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaaa179

- Roy, Parama. Alimentary Tracts: Appetites, Aversions, and the Postcolonial. Next Wave. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smk9d

- Sandiford, Keith A. The Cultural Politics of Sugar: Caribbean Slavery and Narratives of Colonialism. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Schalk, Sami, and Jina B. Kim. "Integrating Race, Transforming Feminist Disability Studies." Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 46, no. 1 (2020): 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1086/709213

- Schwartz, Hillel. Never Satisfied: A Cultural History of Diets, Fantasies, and Fat. New York: Free Press, 1986.

- Shanti George. "Operation Flood and Rural India: Vested and Divested Interests." Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 49 (1985): 2163–70.

- Shaw Nevins, Andrea. The Embodiment of Disobedience: Fat Black Women's Unruly Political Bodies. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2006.

- Shraya, Vivek. She of the Mountains. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2014.

- Smith, Hilary A. "Good Food, Bad Bodies: Lactose Intolerance and the Rise of Milk Culture in China." In Moral Foods: The Construction of Nutrition and Health in Modern Asia, n.d.

- Smith-Howard, Kendra. Pure and Modern Milk: An Environmental History Since 1900. Cary: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Sodhi, Dr R. S. "Verghese Kurien: Cooperative Spirit: Amul's Dr R.S. Sodhi Writes on the 'Milkman of India' Who Led the Cooperative Movement Ending the Dairy Drought and Spurred a Socioeconomic Revolution." India Today, New Delhi, India: Living Media India, Limited, August 30, 2021.

- Stearns, Peter N. Fat History: Bodies and Beauty in the Modern West. NYU Press, 2002.

- Strings, Sabrina. Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479891788.001.0001

- Tompkins, Kyla Wazana. Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the 19th Century. New York, UNITED STATES: New York University Press, 2012.

- Valenze, Deborah M. Milk: A Local and Global History. New Haven [Conn: Yale University Press, 2011.

- Velten, Hannah. Milk a Global History. Edible. London: Reaktion Books, 2010.

- Vuong, Ocean. On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous. New York: Penguin Press, 2019.

- White, Francis Ray. "'We're Kind of Devolving': Visual Tropes of Evolution in Obesity Discourse." Critical Public Health 23, no. 3 (2013): 320–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2013.777693

- Xu, Guoqi. Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895-2008. Harvard University Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674045422

Endnotes

-

Michels, "Wisconsin Buttermaker's Meeting," Hoards Dairyman p 36; M. Mortensen and J.B. Davidson, "Creamery Organization and Construction," Agricultural Experiment State Bulletin 139; Carmichael, "Forty Years of Water Pollution Control in Wisconsin," p 418-419.

Return to Text -

Velten, Milk a Global History.

Return to Text -

See: Garzo and Zandi, "The modern/colonial food system in a paradigm of war;" Janer, "(IN)EDIBLE NATURE: New World Food and Coloniality," 385–405, Nützenadel and Trentmann, Food and Globalization.

Return to Text -

For examples of methods of postcolonial food studies, see: Roy, Alimentary Tracts, Tompkins, Racial Indigestion, Kim, "The Postcolonial Politics of Food." For examples on Asian American Food Studies see: Ku, et al. Eating Asian America: A Food Studies Reader, Ho, Consumption and Identity in Asian American Coming-of-Age Novels; Mannur, Intimate Eating; Padoongpatt, Flavors of Empire.

Return to Text -

Gewertz and Errington, Cheap Meat; Knight, Commodities and Colonialism; Mintz, Sweetness and Power; Morris, Coffee; Sandiford, The Cultural Politics of Sugar; Sunderland, "Trading the Happy Object."

Return to Text -

For some examples of Fat Studies and Disability Studies scholarship that picks at tensions of empire see: Dirth and Adams, "Decolonial Theory and Disability Studies." Grech and Soldatic, "Disability and Colonialism." Imada, "A Decolonial Disability Studies?" Mitchell and Snyder, "The Eugenic Atlantic." Pausé, Wykes, and Murray, Queering Fat Embodiment. Puar, The Right to Maim. Mollow, "Disability Studies Gets Fat." Schalk and Kim, "Integrating Race, Transforming Feminist Disability Studies." Strings, Fearing the Black Body.

Return to Text -

I have written more extensively about Obesogenic research, Feminist Science Studies, and Food Studies investment in curing ob*sity by fixing environmental conditions of poor communities of color in "Genealogies of Excess." Obesogenic research advocates for forms of environmental and health conservation and redress that results in the hyper-surveillance of communities of color through state nutritional and health programs.

Return to Text -

The installation was created by Luke Turner, Nastja Rönko, and Shia Lebeouff. It's important to note that 4chan users were especially interested in targeting this protest installation due to Lebeouff's erratic and controversial public persona, and 4chan users dedicated many months to stalking, provoking, and ridiculing him for sport.

Return to Text -

Tekajin. (2017, Feb 5). #HWNDU SEASON 2 FINALE - [PART 2/5] MILKPARTY

Return to Text -

"OK hand sign added to list of hate Symbols" BBC News, Sept 27, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-49837898?piano-modal; "When the O.K. Sign is No Longer O.K.," New York Times, Dec 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/15/us/ok-sign-white-power.html; "How Pepe the Frog went from harmless to hate symbol," LA Times, Oct 11, 2016, https://www.latimes.com/politics/la-na-pol-pepe-the-frog-hate-symbol-20161011-snap-htmlstory.html

Return to Text -

03:39. #HWNDU SEASON 2 FINALE - [PART 2/5] MILKPARTY. (2017, Feb 5). Tekajin.

Return to Text -

Archive of 4chan thread "Entering the Milk Zone" https://archive.4plebs.org/pol/thread/111581590/

Return to Text -

Velten does this work by taking up, for example, the case of the 1850's New York City Swill Milk Scandal that resulted in over 8,000 infant mortalities (and numerous public health crises). Journalist Frank Leslie wrote several scathing exposes on the scandal, but it often fell upon deaf ears for almost two decades. Velten, Milk a Global History, 57-78.

Return to Text -

See: Nimmo, Richie. Milk, Modernity and the Making of the Human: Purifying the Social. Culture, Economy and the Social. London; Routledge, 2010. Nimmo's study of 19th century British dairy industries unfurls the story of milk as the story of modern humanism, wherein the sanitation practices of cattle-rearing and urban inspection/consumption of dairy was a means of purifying the social and restructuring the boundaries between humans and nature, urban and city life.

Return to Text -

Valenze, Milk: A Local and Global History.

Return to Text -

Atkins, Liquid Materialities looks at the relationship between sanitation practices and forms of containing disease and perfecting milk with the rise of germ theory, where the capacities of man to retool his environment designated borders between humans, animals, and nature. Both works consider how nonhuman actors like bacteria, cattle, and tuberculosis affected milk consumption, the dairy industry, and social structures at large.

Return to Text -

DuPuis, E. Melanie. Nature's Perfect Food.

Return to Text -

Leslie, F. "Starling Exposure of the Milk Trade in New-York and Brooklyn," New York Times, May 7, 1858.

Return to Text -

DuPuis, Nature's Perfect Food, page 11.

Return to Text -

The Wyoming Farm Bulletin, Vol 8. July 1918, pg 15.

Return to Text -

Mitchell and Snyder. "The Eugenic Atlantic."