Networking on the community level, pooling resources, avoiding the duplication of services, education, and cooperation with community leaders are crucial for a broadly based disability network to emerge. This essay presents two models that might serve as inspiration for the creation of community-focused initiatives in the field of disability, namely Kwale Health Forum and Kwale District Eye Centre. Both models address the need to connect with the grassroots community, a relationship that is acknowledged as currently lacking in the "Strategic Plan" of Kenya's National Council for Persons with Disabilities. The discussion shows that a community-based network for disability-related needs has the potential to allow for the identification of disabled individuals; facilitate their access to medical services; provide access to education; and, last but not least, assist in educating caregivers and the larger community, an aspect that is crucial to improving the situations of persons with disabilities.

An ever-growing chorus of scholars and practitioners emphasize the importance of local knowledge in carrying out human-centered development projects in Africa.1 Considering the role of indigenous knowledge systems is essential not only to the success of initiatives that are primarily instigated by external agencies, such as the United Nations or international nongovernmental or faith-based organizations, but also to new projects initiated by Kenyans themselves.2 While it may not be surprising that non-Kenyans often lack knowledge about the local infrastructure and social networks crucial to implementing projects successfully, coordinators of Kenyan-initiated projects often seem equally disinclined to consider the reality of local conditions. Alternatively, some initiatives being led by non-Kenyans have incorporated strategies that pay considerable attention to the social fabric of the environment in which they work. The situation facing persons with disabilities in Kenya provides an excellent opportunity to consider the role of local knowledge in development planning.

Following passage of the "Persons with Disabilities Act, 2003," the question of how it would be implemented remains unclear. The workshop on "Disability, Human Rights and Networks" held in Nairobi in June 2007 reflected the wide range of issues involved in improving the situation of persons with disabilities. While the objectives of rights-based disability initiatives are easy to articulate, deciding how they will be implemented poses considerable challenges. In its "Strategic Plan: 2006-2009" the National Council for Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD) states that "the NCPWD currently has no representation at the grassroots level" (8). This separation from the local community has serious consequences, and while the problem is acknowledged by the NCPWD, strategies to address the situation are only tangentially mentioned in its three-year plan. Here I will present two models that might serve as inspiration for the establishment of community-focused initiatives in the field of disability. Both models are distinguished by their emphasis on connecting those undertaking the project with those who will be affected by it at the grassroots level: the first is a networking organization that improved health-related services in Kwale District, the second an eye clinic operating in the same area that works successfully with local communities.

In 2005 I conducted a study of Kwale Health Forum (KHF), a network of then nearly thirty health-related member organizations and an additional twenty collaborating partners that addressed health care-related needs of about 600,000 people living in Kwale District. Individual member and associated organizations united under the KHF umbrella differed widely in terms of their organizational structure and constituency. Some organizations were strictly locally based; others belonged to regional, national, and international organizations. Their legal status differed as well; they included community-based organizations, or CBOs (Diani-Ukunda CBO cluster group; South Coast Residents' Association); faith-based organizations, or FBOs (Digo Language and Literacy Project; Muslim Council of Imams, Kwale; Catholic Secretariat); nongovernmental organizations or NGOs (Centre for Humanitarian Outreach and Intercultural Exchange); government-to-government bodies (DANIDA-Health Services Project); the Government of Kenya (Ministry of Health (MoH); various line ministries); and private sector organizations (Verkaart Trust Foundation; Rotary Club of Diani). Some of these member organizations have a specific focus — for example, dealing with issues concerning women (East African Women's League, Maendeleo Ya Wanawake), children (Plan Kenya, United Nations Children's Fund), epilepsy (Diani/Ukunda Epilepsy Clinic), the physically disabled (Association for Physically Disabled of Kenya), eye-related diseases (Kwale District Eye Centre), and rural areas (Coastal Rural Support Programme). In addition to its member organizations and collaborating organizations, KHF maintained contact and networks with a range of relevant organizations in and around the area.

Through networking, assessment, and the creation of specific action plans, employing a wide range of communications media and information technologies, KHF avoided duplication of services and improved the accessibility of a range of health care services to the people of Kwale District. My study of KHF activities showed that the network fostered a more active and informed civil society, and its success confirms the findings of other studies of recent Kenyan community-based organizations that document the growing number of thriving community-based initiatives (Ahuya et al. 2005; Ellis et al. 2006; Haro et al. 2005; Maalim 2006; Muraya 2006). In their recent analysis of the health care sector in Kenya, Mbatia and Bradshaw argue that "better health care would be realized if NGOs and the Kenyan government would pool their resources" (88). KHF facilitated such a process, successfully reaching a large segment of the community and involving local actors from all areas of life.

KHF was founded in late 1998, and while its relationship to the Ministry of Health was at times difficult, its successes led to the adoption of its principles by the MoH. In October 2004 the health ministry published "Guidelines for the Establishment and Operation of the District Health Stakeholders' Forum." These guidelines describe a type of organization that is modeled after KHF and thus implicitly acknowledge KHF as a role model in the health care sector. In the guidelines published by the ministry, however, the secretary is the district medical officer of health by virtue of office, the steering committee does not mandate representation of nongovernmental stakeholder organizations, and the District Health Management Board is given ultimate oversight (Ministry of Health 2004: 14-15; Ministry of Health 2005: 17-18). Several District Health Stakeholders' Forums were established in Kenya, for example in Nakuru and Kajiado. In June 2007, KHF was reorganized and folded into the new governmental structure. It remains to be seen whether this government-developed model confirms past experience in which successful community-based models of development were derailed by government intervention (Were 2002).

For our purposes, however, the success of this networking model in improving health-related services may serve as an inspiration to disability-related initiatives. The establishment of a similar networking model, perhaps named "District Disability Stakeholders' Forum," may facilitate the effort to improve the situation of persons with disabilities by fostering networking strategies that avoid duplication, pool resources, and potentially reach a larger group of persons in need of services.

Two key aspects of the study I conducted of KHF in 2005 are also relevant with regard to disability-related initiatives, particularly in rural areas. The first concerns the connection of any health or disability initiative to the communities, and the second relates to the tension between indigenous and Western medicine. With regard to the connection between clinics, dispensaries, and local communities, the existing network of village health committees and village health workers functions only with varying degrees of success. Matomora (1989a) and Kaler and Watkins conducted studies on the difficult role of community health workers. The director of Aga Khan Health Services in Mombasa, in my conversation with him, referred to a follow-up study that revealed that over time 50 percent of trained village health workers had dropped out of programs (pers. comm., August 4, 2005). Suggestions have been made for how to remedy the high dropout rate of village health workers (Johnson et al.; Mburu), how to increase community interest in development projects (Jacobson et al.), and how to institutionalize projects within communities rather than through outside organizations (Kaseje and Sempebwa; Rono and Aboud; Schafer; Thomas-Slayter). Consideration of these studies may allow community-based health and disability networks to optimize their efforts.

In addition, my study confirmed that the role of indigenous health care providers is crucial. Eighty percent of the citizens of Kwale District, for example, continue to use the services of indigenous medicine practitioners (Ministry of Gender, Sports, Culture and Social Services: 1). Whereas access and cost play a role in explaining this situation, cultural factors weigh more heavily. In any case, the vital function of indigenous medicine practitioners in local communities is a fact, and proclaiming that "people should stop believing and practicing witchcraft" is simply not an effective way to change beliefs and practices (33). Health workers and social workers trained in Western medicine/paradigms need to acknowledge that indigenous healers provide crucial services in light of the fact that the Western-based health care system is often not available, remains too costly, or is culturally off-putting to some members of the population.

No substantial success can be achieved regarding the overall improvement of health services unless a dialogue is established with these practitioners. This dialogue will only be successful, however, if it speaks a language of respect that allows indigenous medicine practitioners to save face. Otherwise, neither side will be able to absorb new knowledge. Several health workers I interviewed shared anecdotes regarding the disrespect that Western-based medical workers showed for indigenous medicine workers by, for example, cutting off charms that people had received from healers. Several organizations, such as Plan Kenya, Action Aid, and Aga Khan Health Services, have piloted collaborative and educational projects involving these indigenous medicine practitioners, and some report that the programs have been successful. As one health care worker put it, referring to indigenous medicine practitioners, "the system is incomplete without them" (pers. comm., August 10, 2005). Questions remain, however, about the lasting impact of the programs as well as developing ways to measure that impact.

Several representatives I interviewed in 2005 lamented the fact that the Ministry of Health was not willing to collaborate with indigenous medicine healers. This dismissive attitude was confirmed, for example, in the MoH's 2005 "Annual Expenditure Review," which studied the current situation and articulated goals for the future. In this report the MoH ignores indigenous medicine as a useful resource in addressing the present crisis. The representatives I interviewed also remarked that some of the international organizations did not fully comprehend local conditions, cultural specificity, and indigenous practices, and that this lack of understanding had a detrimental impact on health care in the area, including the collaborative projects. Furthermore, the majority of MoH workers in Kwale are from the up-country areas and, as one person put it, "don't mesh with local folks" (pers. comm., August 10, 2005). Although the problem is not primarily a result of linguistic or religious differences, MoH workers' unfamiliarity with local culture and disparities between these workers and those they serve in terms of education (which reflect differences in social class as well as different views about Western medicine) make communication between MoH workers and the local population difficult. A consistent theme in my conversations was that policy developed abroad or in Nairobi led to "a waste of resources" because it was not based on local knowledge.

In my view a real breakthrough in combating diseases and also in bettering the situation for persons with disabilities will only be achieved if a collaborative relationship develops between indigenous medicine practitioners, village health committees, and health workers trained in Western medicine. As one person put it, "Traditional healers are leaders in their communities; they listen to the people and are respected" (pers. comm., August 10, 2005). If health workers lack respect for members of the local community who are revered by most of the area's citizens, efforts at collaboration will certainly be impeded. The humiliation people experience as a result of the disrespect they receive for adhering to local cultural norms aggravates their relationship with health workers trained in Western medicine. As a result, they hesitate to seek the services of the conventional health system.

Several studies suggest productive ways in which indigenous medicine may be incorporated into national health care policy (Harrell-Bond; Nyaoro). Indeed, in some cases indigenous and Western medicine have been successfully integrated (Klaub; McMillen; Nyamongo; Nyamwaya). Involving indigenous medicine practitioners in various initiatives may be an important step toward developing a more broadly community-based and integrative health care model.

Clearly, the question of how to collaborate with indigenous medicine workers and village elders is especially difficult in the field of disability, as beliefs regarding disability as a curse or a case of being possessed by a negative spirit continue to abound. Most contributions collated in this issue of Disability Studies Quarterly provide ample evidence for the perceived connection between curses and disability. One such area in which people turn to supernatural explanations for illness is the field of epilepsy. El Sharkawy et al. have shown that parents of children with epilepsy perceive the illness as related, among other explanations, to spirit possession, witchcraft, and the work of the devil (204). The perceived causes of the illness further determine the measures undertaken for treatment, which are predominantly rooted in indigenous practices. They include urinating on the child, pouring paraffin or water on the child, and making burns on the head (206). These beliefs and practices, in addition to cost factors and questions of access, determine the choice of services: most parents will consult with the local indigenous healer, which results in an underutilization of available medical services. In spite of evidence showing a preference for traditional approaches to dealing with epilepsy among the local population, many individuals expressed a willingness to try using drugs prescribed by a doctor as well as a desire for further education (208). El Sharkawy et al. conclude that

for medical services to be more widely used in Kilifi, they should be decentralized and accessible. They need to be monitored in relation to local practices so that they can be developed to compete with the more popular traditional and religious services. At the same time, community education programs should be used to sensitize Kilifi residents to Western knowledge on epilepsy and how to treat it. (211)

Their study shows that beliefs regarding epilepsy continue to structure people's attitudes toward and practices for dealing with this particular disability and makes the case for the importance of fostering a dialogue that seeks creative solutions that are sensitive to existing practices and beliefs.

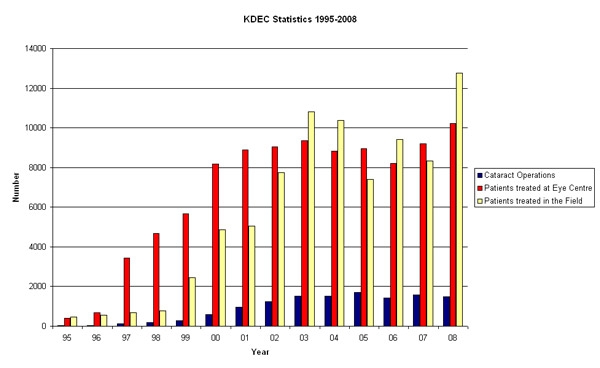

My second model of a community-focused health care initiative is exemplary with regard to its level of cooperation with village elders, women's groups, and health committees. Kwale District Eye Centre (KDEC) is a successful model for community-based health care networking. It was established in 1993 by ophthalmologist Dr. E. Helen Roberts in response to the fact that one out of one hundred residents living in Kwale District is blind due to diseases that are 80 percent curable or preventable and mostly due to poor nutrition. The Centre quickly grew into a successful operation, expanding from its original single room into a large facility, with the number of patients growing exponentially: while in 1995 less than one hundred surgeries per year were performed, by 2005 this figure had risen to over fifteen hundred. According to a brochure I was given during a follow-up visit to the Kwale District Eye Centre in June 2007, "in 2006 alone, we performed 1,797 operations; 1,423 were cataract operations with lens implants. 317 people were totally blind before surgery and can now see! More significant in terms of blindness, in 2006, 19 children had their sight restored through the work of KDEC." By 2008 further increases in terms of the number of surgeries and treatments were recorded:

("Statistics," Eyes for East Africa).

The Centre works closely with the MoH and trains ministry staff but receives no government funding and has maintained complete financial independence through creative fund-raising strategies inside and outside the country. One key reason for the Centre's success, and central to my argument, is the fact that its workers go out into the community; of the presently 49 people employed by the Centre, 18 are field-workers (including rehabilitation officers and vision therapists) and other community-based staff members.3 In addition, almost the entire staff is Kenyan, which seems to be central to facilitating successful community-based work (Hoenig 15-16). The Centre is keenly aware of the factors, particularly cultural factors, that typically keep people from seeking medical help. It addresses this cultural and psychological dimension by sending its field-workers directly to the villages to educate people and identify patients. KDEC staff members cover the entire region of Kwale District (and even beyond); a map on display in the Centre's main office lists relevant data, such as the number of irreversibly blind persons, village health committees, and women's groups in various sections of the district. KDEC collaborates primarily with village health committees and women's groups.

Staff members hold public awareness meetings and conduct screenings. Because of their willingness to engage with traditional healers, these health workers have become accepted and respected within the communities in which they work. KDEC staff members have developed creative ways of collaborating with traditional healers; for example, they bring healers to the operating theaters and explain what happens during surgery. They have devised a referral system based on collaboration in which they educate traditional healers to distinguish between diseases that they can treat successfully and those that need to be referred to the clinic. They have also developed a lexicon that is geared toward diminishing fears that locals might have. Rather than talking about surgery, for example, they use the Swahili word kusafisha, which means "to clean" (the eye), in order to describe what will happen during surgery.

In June 2007 I attended a screening in the Tiwi area.4 The screening, which is held once a month in different locations of the area assigned to the particular field-worker, had been announced a few days earlier through loudspeakers and pamphlets. It consisted of three components: registration, visual testing, and an examination of the inner parts of the eye. Following registration, in which name, location, age, and gender were recorded, the individual underwent a vision test, which used one chart with letters for those who were literate and another chart with symbols for illiterate individuals. Next, the inner parts of the eye were examined, the final step in determining whether an individual needed treatment. Those requiring treatment and surgery (typically about 5 to 15 people) were brought to the clinic immediately after the screening. About 95-120 people are screened in one day. It should be noted that the MoH also offers screenings, but the trip to the Kwale Assessment Centre is too expensive for many individuals; thus, KDEC reaches the population more effectively than the MoH. The numbers speak for themselves: "To date more than 95,000 patients have been treated at the Centre, over 12,000 cataract operations have been carried out and some 81,000 patients have been treated in the field" ("Statistics"). Not only the high figure documenting treatment in the field, but also the high number of surgeries and treatment at the Centre can be attributed to KDEC's successful community-based approach.

The Kwale District Eye Centre offers an admirable paradigm, drawing successfully on Western-based medicine, indigenous medicine, and community networking. The community-centred approach taken by KDEC might inspire the formation of similar models in other areas of disability. Along these lines, the networking strategies utilized by Kwale Health Forum, which has now been reorganized as the District Health Stakeholders' Forum, may serve as a blueprint for developing networks of disability-related initiatives.5 Both models address the need for establishing connections between health/social workers and local communities, a connection that is acknowledged as currently lacking in the "Strategic Plan" of the National Council for Persons with Disabilities (8). Networking on the community level, pooling resources, avoiding the duplication of services, providing education, and fostering cooperation with community leaders are crucial for a broad-based disability network to emerge. A community-based network for disability-related needs will allow for the identification of disabled individuals; facilitate their access to medical services; provide access to education; and, last not least, assist in educating caregivers and the larger community, an aspect that is crucial to the improvement of the situations of persons with disabilities (Hartley et al.; Omondi et al.).

Works Cited

- Ahuya, C. O., A. M. Okeyo, Mwangi-Njuru, and C. Peacock. 2005. "Developmental Challenges and Opportunities in the Goat Industry: The Kenyan Experience." Small Ruminant Research 60 (1-2): 197-206.

- Ellis, A. E., R. Gogel, B. R. Roman, J. B. Watson, D. Indyk, and G. Rosenberg. 2006. "The STARK Study: A Cross-Sectional Study of Adherence to Short-Term Drug Regimens in Urban Kenya." Social Work in Health Care 42 (3-4): 237-50.

- El Sharkawy, G., C. Newton, and S. Hartley. 2006. "Attitudes and Practices of Families and Health Care Personnel toward Children with Epilepsy in Kilifi, Kenya." Epilepsy and Behavior 8 (1): 201-12.

- Haro, Guyo O., Godana J. Doyo, and John G. McPeak. 2005. "Linkages between Community, Environmental, and Conflict Management: Experiences from Northern Kenya." World Development 33 (2): 285 - 99.

- Harrell-Bond, Barbara E., and Wim Van Damme. 1997. "The Health of Refugees: Are Traditional Medicines an Answer?" curare: Zeitschrift für Ethnomedizin und transkulturelle Psychiatrie / Journal of Medical Anthropology and Transcultural Psychiatry (special issue on "Women and Health: Ethnomedical Perspectives") 11:385 - 92.

- Hartley, S., P. Ojwang, A. Baguwemu, M. Ddamulira, and A. Chavuta. 2005. "How Do Carers of Disabled Children Cope? The Ugandan Perspective." Child Care Health and Development 31 (2): 167-80.

- Hoenig, Stacy L. "'Missionary' Redefined: German Mission Work in 21st-Century East Africa." Honor's Thesis, The Ohio State University, 2009.

- Jacobson, Mark L., Miriam H. Labbok, Robert L. Parker, David L. Stevens, and Susan A. Carter. 1989. "A Case Study of the Tenwek Hospital Community Health Programme in Kenya." Social Science and Medicine 28 (10): 1059 - 62.

- Johnson, Karin E., Wilson K. Kisubi, J. Karanja Mbugua, Douglas Lackey, Paget Stanfield, and Ben Osuga. 1989. "Community-Based Health Care in Kibwezi, Kenya: 10 Years in Retrospect." Social Science and Medicine 28 (10): 1039 - 51.

- Kaler, Amy, and Susan Cotts Watkins. 2001. "Disobedient Distributors: Street-Level Bureaucrats and Would-Be Patrons in Community-Based Family Planning Programs in Rural Kenya." Studies in Family Planning 32 (3): 254 - 69.

- Kaseje, Dan C., and Esther K. N. Sempebwa. 1989. "An Integrated Rural Health Project in Saradidi, Kenya." Social Science and Medicine 28 (10): 1063 - 71.

- Klaub, Volker. 1994. "Traditionelle Behandlung von Augenkrankheiten in Kenia." curare: Zeitschrift für Ethnomedizin und transkulturelle Psychiatrie / Journal of Medical Anthropology and Transcultural Psychiatry 17 (2): 149 - 60.

- Kwale District Eye Centre. 2007. "The Eye Centre with a Difference." Brochure. Kwale.

- Maalim, A. D. 2006. "Participatory Rural Appraisal Techniques in Disenfranchised Communities: A Kenyan Case Study." International Nursing Review 53 (3): 178-88.

- Matomora, M. K. S. 1989. "Mass Produced Village Health Workers and the Promise of Primary Health Care." Social Science and Medicine 28 (10): 1081 - 84.

- Mbatia, Paul N., and York W. Bradshaw. 2003. "Responding to Crisis: Patterns of Health Care Utilization in Central Kenya amid Economic Decline." African Studies Review 46:69 - 92.

- Mburu, F. M. 1989. "Wither Community-Based Health Care?" Social Science and Medicine 28 (10): 1073 - 79.

- McMillen, Heather. 2004. "The Adapting Healer: Pioneering through Shifting Epidemiological and Sociocultural Landscapes." Social Science and Medicine 59: 889 - 902.

- Ministry of Gender, Sports, Culture and Social Services, Department of Culture, Kenya. 2004. "Socio-Cultural Profile of the Digo and Duruma Communities, Kwale District: Implications for Development." Nairobi.

- Ministry of Health, Kenya. 2004. "Guidelines for the Establishment and Operation of the District Health Stakeholders' Forum." Nairobi: Health Sector Reform Secretariat, Ministry of Health.

- ---. 2005a. "Guidelines for the Establishment and Operation of the District Health Stakeholders' Forum." Nairobi: POLICY Project.

- ---. 2005b. "Public Expenditure Review." 2005. Nairobi: Ministry of Health.

- Muraya, P. W. K. 2006. "Failed Top-Down Policies in Housing: The Cases of Nairobi and Santo Domingo. Cities 23 (2): 121-28.

- Omondi, D., C. Ogol, S. Otieno, and I. Macharia. 2006. "Parental Awareness of Hearing Impairment in Their School-Going Children and Healthcare Seeking Behaviour in Kisumu District, Kenya." International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 71 (3): 415-23.

- National Council for Persons with Disabilities. N.d. "Strategic Plan: 2006-2009." N.p.

- Nyamongo, I. K. 2002. "Health Care Switching Behaviour of Malaria Patients in a Kenyan Rural Community." Social Science and Medicine 54: 377 - 86.

- Nyamwaya, David. 1987. "A Case Study of the Interaction between Indigenous and Western Medicine among the Pokot of Kenya." Social Science and Medicine 25 (12): 1277 - 87.

- Nyaoro, Wilson. 1997. "The Role of Ethnomedicine in Promoting the Health of Women in Kenya." curare: Zeitschrift für Ethnomedizin und transkulturelle Psychiatrie / Journal of Medical Anthropology and Transcultural Psychiatry (special issue on "Women and Health: Ethnomedical Perspectives") 11: 45 - 52.

- Rono, Philip K., and Abdillahi A. Aboud. 2001. "The Impact of Socio-Economic Factors on the Performance of Community Projects in Western Kenya." Journal of Social Development in Africa 16 (1): 101 - 23.

- ---. 2003. "The Role of Popular Participation and Community Work Ethic in Rural Development: The Case of Nandi District, Kenya." Journal of Social Development in Africa 18 (2): 77 - 103.

- Schafer, Mark Joseph. 2000. "Helping Ourselves: Community Organization and Family Educational Practices in Rural Malawi and Kenya." Ph.D. diss., Indiana University.

- Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books, 2000.

- ---. On Ethics and Economics. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1987.

- "Statistics." Eyes for East Africa. http://www.eyesforeastafrica.org/statistics.htm. Thomas-Slayter, Barbara P. 1991. "Class, Ethnicity, and the Kenyan State: Community Mobilization in the Context of Global Politics." International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 4 (3): 301 - 21.

- Were, Miriam K. 2002. "Kakamega, Kenya: A Promising Start Derailed." In Just and Lasting Change: When Communities Own Their Futures, ed. Daniel Taylor-Ide and Carl E. Taylor, 168 - 77. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- World Bank. "Indigenous Knowledge for Development Results." http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/EXTINDKNOWLEDGE/0,,menuPK%3A825562~pagePK%3A64168427~piPK%3A64168435~theSitePK%3A825547,00.html.

Endnotes

-

The term "development" comes with heavy ideological baggage, as it often implies change along the lines of Western models of modernity and economics. I use the term in the sense of Amartya Sen's suggestions: "Development requires the removal of major sources of unfreedom: poverty as well as tyranny, poor economic opportunities as well as systematic social deprivation, neglect of public facilities as well as intolerance or overactivity of repressive states" (Development as Freedom 3). Sen insists on the central role of ethics for economic development. He takes a cue from Aristotle who, in the Nicomachean Ethics, considers social achievement and argues: "Though it is worthwhile to attain the end merely for one man, it is finer and more godlike to attain it for a nation or for city-states" (quoted in On Ethics and Economics 4).

Return to Text -

For evidence of the growing emphasis on the importance of indigenous knowledge systems for development, see the World Bank's web site on the topic. Presently, the database for Kenya lists over fifty entries, addressing indigenous knowledge in areas such as traditional medicine, agriculture, and biodiversity. While this database is clearly rudimentary, I refer to the web site as an example of the way the idea of indigenous knowledge is increasingly being incorporated into development rhetoric. The question of whether World Bank rhetoric translates into practice and policy implementation remains to be explored. See http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/EXTINDKNOWLEDGE/0,,menuPK%3A825562~pagePK%3A64168427~piPK%3A64168435~theSitePK%3A825547,00.html.

Return to Text -

Information provided per email by Catherine Jakaiti Ogeya, August 10, 2009.

Return to Text -

I would like to thank Catherine Jakaiti Ogeya for the time she took to explain operations at the Eye Centre in July 2005 and for allowing me to attend the screening in Tiwi in June 2007. I would also like to thank Dr. Helen Roberts for providing additional information in an email exchange in August 2007.

Return to Text -

It should be noted that the establishment of KHF was based in part on the experience gained by one of the founding members, namely Eileen Willson, who worked for KDEC as a volunteer from 1994 to 2000. Mrs. Willson served as the KHF secretary and coordinator from 1998 until the organization adopted the government model in June 2007.

Return to Text