My artistic practice focuses on the intersectionality of my lived experience of mental health difference as a Thai American woman who has contended with the impacts of the stigma and inequities in mental health care and access. Having been diagnosed with bipolar, I explore my way of being through my art and seek to assess and illuminate my lived experiences through the lens of disability justice and mad pride. My "archive" consists of medication guides, prescription bottles, historical and psychiatric resource materials, and medical texts that discuss mental health conditions. I use these texts and artifacts in my art and investigate systemic and historical legacies to find strength in vulnerability.

In my large scale drawings, I use charcoal because of its transformative origins from solid matter and to acknowledge that its activated form absorbs chemicals after a stomach is pumped following an overdose. The smeared charcoal emphasizes outlandishness and an unwillingness to conform, as I resist containment and being categorized. In affirming freedom and individuality, I reveal the human touch behind the marks and processes that spill off the page and ignore the margins.

Created during the pandemic, my large scale series of over 80 drawings, "What I have learned. (Fill in the blank.)" on oversized lined paper, 36" x 24," questions how we learn, who is the "educator" and how do we unlearn harm. I mine interactions, relationships and responses to my being from micro aggressions, to stigma, racism, and ableism as well as reflect on current anti-Asian violence.

By sharing these texts and images, I allow others who might identify with these experiences to enter a safe space and connect to others to build a community in pursuit of disability justice.

My art practice focuses on my lived experience of mental health difference as a Thai American woman and the impact of stigma, discrimination, and unequal access to healthcare. 1 As someone diagnosed with bipolar disorder, I explore my way of being as a way to grasp and translate the meaning of my experiences through the lens of disability justice 2 and mad pride. 3 I incorporate into my artwork an archive of medication guides, prescription bottles, historical and psychiatric resource materials, and medical texts that reflect mental health conditions and the American psychiatric system. I find strength in vulnerability.

In my large-scale drawings, I use charcoal because of its transformative origin from solid matter and its ability to absorb chemicals after a stomach is pumped from a medication overdose. The exaggerated scale is meant to draw a contrast between the documented paper trail—including material from the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), research studies, medical textbooks, and medication guides—and the lived experience. The smeared charcoal and disregard for the margins reveals the human touch behind the mark and emphasizes my refusal to conform to rigid boundaries. Collage, layered imagery, and text reconfigure into a new context. These drawings embody experiences that question the psychosocial impact of racism, stereotypes, and the American healthcare system, even as they affirm the lived experience.

Created during the pandemic, my series of over 80 drawings, "What I have learned (Fill in the blank)," on oversized lined paper, 36" x 24", questions the process of institutionalized education in the United States. The drawings ask who is the "educator" and how and when does one unlearn harmful concepts. The dotted and solid lined manila-colored paper, conventionally used to teach penmanship in elementary school, reflects this process. I unearth interactions, relationships, and responses to my being, ranging from microaggressions to stigma, racism, and ableism.

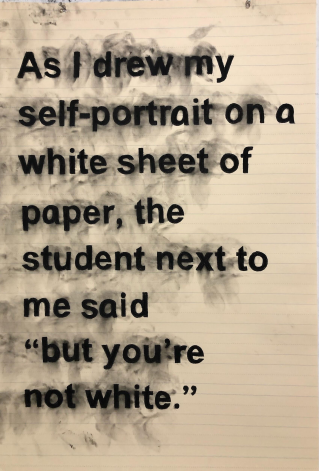

Othering — Self-Portrait in Adolescence

Fig. 1. What I have learned series (Self-Portrait in Adolescence), 2020, ID: text written in charcoal on light blue lined manila colored paper covering the entire page that is smeared reading, "As I drew myself on a white sheet of paper, the student next to me said, 'but you're not white.'" 36" x24"

One of my first experiences with difference was in elementary school when my art teacher asked the class to draw a self-portrait. As I began to draw my face on the white sheet of paper given to each pupil, the girl sitting next to me said to me, "But you're not white," as she tossed her wavy blonde hair that grazed over her peaches and cream skin, as if to mock me. Self-Portrait in Adolescence [Fig. 1] reflects this.

I internalized these slights and harsher taunts that led to painful shyness, depression, and suicidal thoughts. This process began at a tender age that developed through adolescence and into young adulthood. I longed to not be me. And stigma kept me silent.

My impressionable self unseen beyond my skin color. In this drawing, I highlight the narrative behind the formation of self as I use English text in place of my face. As bell hooks states in Teaching to Transgress, "Standard English is not the speech of exile. It is the language of conquest and domination; in the United States, it is the mask which hides the loss of so many tongues, all those sounds of diverse, native communities we will never hear with." 4

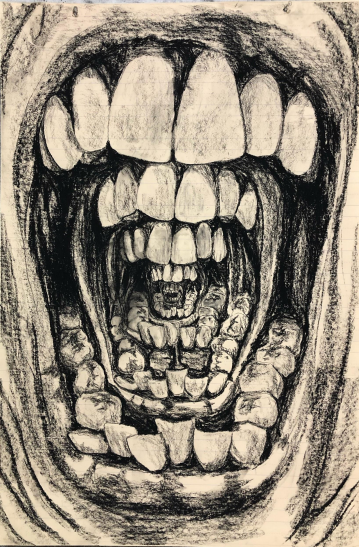

Stigma — Internalized

I withdrew and became a stranger to myself as multiple lost selves reverberated as seen in the drawing Internalized [Fig. 2].

Fig 2. What I have learned series (Internalized), 2021, charcoal drawing on light blue-lined manila paper with five gaping mouths with crooked teeth, one inside the other spanning the entire page that is smeared. 36" x24"

In Neil Marcus' Disabled Country, he declares:

If there was a country called disabled,

I would say she has immigrants that come to her

From as far back as time remembers.

If there was a country called disabled,

Then I am one of its citizens.

But what if as an Asian American, 5 you are already seen as a perpetual foreigner? I am lumped together with a population that spans over twenty countries and over 800 languages and dialects. Like many Asian Americans, I am still asked, "Where are you from?" People also declare, "You speak English so well!" The "model minority myth" expects me to excel, be polite, submit to others, focus on hard work, and not make any waves. This stereotype fails to acknowledge the diversity and complexity of individuals and disparages the disabled. If the model minority stereotype is believed, resources and social services can be withheld. 6

Belonging to Generation X, I grew up in a predominantly white town in upstate New York. My desire to assimilate during adolescence spawned internalized racism and later led to self-stigmatization as a young adult. I was in denial of not only my diagnosis of bipolar disorder but also of my lived experience of mental health difference and disability. I saw other people's version of myself and became a stranger to myself. I even accepted the regular mispronunciation of my name by teachers and friends. "In the United States today, assimilation into mainstream culture for people of color still means adopting a set of dominant norms and ideals - whiteness, heteronormativity, middle-class family values, Judeo-Christian religious traditions." 7

When I discovered Disability Studies in graduate school, I sought perspectives on disability by asking peer graduate students and professors to write the first word that came to mind when they heard the word "disability." One response I received was written in caps, "FUCKED UP." Shana Bulhan Haydock says, "Fuck normal" in fucked up / I would Always Rather Be Abnormal than Holistic: Nine Micro-Essays. I found solace in these essays located in DSM II: Asian American Edition, a part of the Open in Emergency: A Special Issue on Asian American Mental Health 2019, 8 a community of voices that explores structures of care in relation to the lived Asian American experience. As Haydock writes, "It's 'normal' to feel the wide spectrum of emotions, from manic joy to the deepest despair. It's 'normal' to obsess, to be consumed by anxiety. It's even 'normal' on some level, to have intrusive thoughts and experience psychosis." My mental health difference does not define me, but I do not deny it is a part of me, much like my Thai heritage.

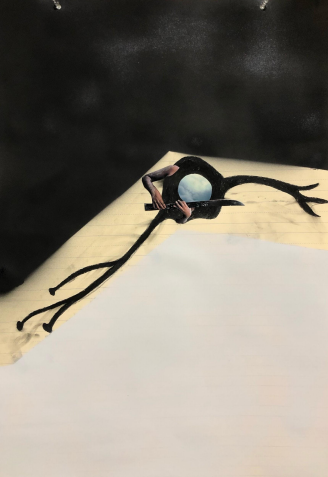

Invisibility — In Between

Fig. 3. What I have learned series (In Between), 2020, charcoal drawing on lined paper with a black spraypainted angled shape at the top and a white spraypainted angled shape on the bottom with a black, bipolar neuron drawn in charcoal in between with bare light blue-lined manila paper in the background. In the center is a collaged circle that shows clouds. Arms jut out of the neuron cradling a knife. 36" x24"

The drawing In Between reflects the invisibility of Asian Americans in studies conducted, noting disparities as the model minority myth dominates and does not acknowledge the diversity of its population. The bipolar neuron figure lies within and between a filled-in black and white spray painted line graph that captures the unemployment disparities between Black and white populations as a result of the impact of COVID-19 in 2020, the beginning of the pandemic. The bipolar neuron wields a knife in either defense or self-harm. As a temporary worker, I lost my job as an administrative coordinator, as all temporary and contracted workers were laid off at the university where I worked. Already invisible. Our labor filled the gaps. Most of us were uninsured as contracted workers, meaning we did not have access to healthcare. If we had insurance, the coverage was so minimal that we did not have access to a primary care physician or prescription medications.

In recent research, Asian Americans were found to be the most severely impacted by psychological distress following job losses during the COVID-19 pandemic. 9 In states like New Jersey (where I live), forty-nine percent of psychiatrists do not accept health insurance. 10 An American Psychological Association report found that only five percent of psychologists are Asian, 11 and a similar disparity exists among social workers and psychiatrists in the United States. This disparity makes it difficult for me to find an Asian American woman practitioner who might be able to relate to my lived experience. Suicide is the leading cause of death among Asian American youth ages 15-24 12 and for Asian American Senior women, ages 64 and older. 13 "Not all Asian Americans are depressed, but several studies have shown higher levels of social isolation and depressive symptoms among Asian American adolescents in comparison to their African American, Latinx, and white peers." 14

Self-Empowerment — Yak Within Me

As my Asian American girlfriends buy pepper spray to defend themselves against potential Anti-Asian violence and dodge tomatoes thrown at them along with racial epithets, the real fear of violence prevents some from even leaving home. This mental stress takes its toll. When former President Trump called COVID19 a "Chinese virus," I felt tense in public as I mustered up the strength to suppress every cough and sneeze with the fear of repercussions as an Asian American. One of the victims of anti-Asian violence during the pandemic was an 84-year-old Thai elder named Vicha Ratanapakdee who was attacked in 2021 just outside his home in San Francisco. 15 This hit home.

Fig. 4. What I have learned series (Yak within Me), 2021, a gaping mouth with crooked teeth drawn in charcoal on light blue lined manila paper spanning the entire page that is smeared. Inside the mouth is a yak, a mythical head of a guardian figure with beady eyes, large graphic eyebrows, with tusks with decorative elements, 36" x24"

To conjure up mental fortitude and cultural pride, I created the drawing Yak within Me, displaying the Thai guardian emerging from the wide gape of my mouth. The yak is a mythological giant that represents power and mystical protection. Contrary to the Asian American female stereotype of docility and meekness, I roar with the yak's power.

By sharing these texts and images, I invite people who might identify with these experiences to enter a safe space to share their own. I ask others to empathize and reflect. The model minority myth not only does not fit but it also generates stress and harm as it disregards mental health difference and disability. Art can empower and provide access to the discourse on race, disability, and mental health difference. Imagination is a form of resistance, potentially liberating, and is a vehicle to connect with others to form a community of collective care and mutual aid in the pursuit of disability justice.

Works Cited

-

For more about my work, visit Chanikasvetvilas.com or my Instagram @chanikasvetvilas.

Return to Text -

Sins Invalid, "10 Principles of Disability Justice, September 17, 2015, www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/10-principles-of-disability-justice.

Return to Text -

Gabrielle Glaser, 'Mad Pride' fights a Stigma, New York Times, May 11, 2008.

Return to Text -

bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress, Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 1994) 168.

Return to Text -

"Coined by Japanese American activist, Yuji Ichioka. "Asian American" is not merely a racialized category; rather, it is a political identity that recognizes a commitment to pan-ethnic movements to support the self-determination and liberation of diverse Asian American communities." "Our History," San Francisco State University: Asian American Studies, aas.sfsu.edu.

Return to Text -

I use the term Asian American in reference to how I self-identify. However, the term Asian American has evolved to be more inclusive of the diverse populations it aims to represent referred to as Asian/Pacific American (APA), Asian/Pacific Islander (API), or Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI).

Return to Text -

Maria Cohut, "The 'Model Minority Myth: Its Impact on Wellbeing and Mental Health," Medical News Today, July 31, 2020. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/the-model-minority-myth-its-impact-on-well-being-and-mental-health

Return to Text -

Eng, David L., and Shinhee Han. Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation: On the Social and Psychic Lives of Asian Americans (Duke University Press, 2019) 35. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smqsk

Return to Text -

Haydock, Shana Bulhan, "fucked up," I WOULD ALWAYS RATHER BE ABNORMAL THAN HOLISTIC: NINE MICRO-ESSAYS, DSM II: Asian American Edition, Open in Emergency: A Special Issue on Asian American Mental Health Second Edition, Asian American Literary Review, (2019):43.

Return to Text -

Livio, Susan K. "Is the doctor in? Nearly half of N.J. psychiatrists aren't accepting new patients, survey finds," NJ Advance Media, nj.com, Accessed 2,October 2014).

Return to Text -

"Lin, Luona, Karen Stamm, and Peggy Christidis, "How diverse is the psychology workforce?" Psychology 49.2 (2018): 19.

Return to Text -

"Asian American young adults are the only racial group with suicide as their leading caus of death, so why is no one talking about this?" The conversation, theconversation.com. Accessed 23 April 2021.

Return to Text -

Rivas, Jorge, "Older Asian American Women Have Highest Suicide Rate," Colorlines, https://colorlines.com/article/older-asian-american-women-have-highest-suicide-rate, Accessed 23 January 2013.

Return to Text -

Eng, David L. and Han, Shinhee. Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation (Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2019) 34. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smqsk

Return to Text -

Fuller, Thomas, "He came from Thailand to Care for Family, Then Came a Brutal Attack," New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/27/us/asian-american-hate-crimes.html, Accessed 27 February 2021.

Return to Text