This paper is rooted in my investigation of the artistic processes and practices of artists with disabilities through field observations at Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California. Through this investigation, I develop the concept of a pedagogy of waiting, which allows for a consideration of embodied differences. This pedagogy of waiting is conceptualized by and with 1) the everyday artistic processes and practices of artists at Creative Growth; 2) my positionality of being a Chinese art educator and researcher in an art studio, Creative Growth, in the United States; and 3) my conceptual and theoretical exploration with philosophers and disability studies scholars. Among the artists who informed the pedagogy of waiting is Latefa Noorzai, a native Farsi speaker and immigrant to the United States. The temporalities demonstrated through Latefa's art practice and the pedagogical practice at Creative Growth challenge the normative temporalities in art learning and art making. The pedagogy of waiting is both informed by people with disabilities and as an alternative to able-bodied and able-minded pedagogies.

"[Artist] Latefa [Noorzai] spoke about Creative Growth [Art Center] through a [Farsi-English] translator: 'I didn't go to school, I never made art, not until they brought me here. This is my home. This is my Afghanistan."

Introduction

Although disability legislation has provided increased opportunities for students with disabilities to learn art in classrooms and art centers since the 1970s, the field of Art Education has generally remained uncritical of its delimiting assumptions and pejorative representations of disability (Eisenhauer, 2007; Derby, 2011; Wexler & Derby, 2015). Art educational practice has been dominated by able-bodied and able-minded pedagogical practices. In doing so, disability experiences in art classrooms have often been overlooked or stigmatized by normative understandings of art making and art learning. To challenge ableist pedagogies, my work investigates how the nuanced experiences of people with disabilities and disability artmaking question and inform pedagogical practice.

My work comes from fieldwork I conducted for one year at Creative Growth Art Center (henceforth "Creative Growth") in Oakland, California, founded in 1974 by artist Florence Ludins-Katz and her husband, psychologist Dr. Elias Katz and considered to be one of the world's largest and oldest contemporary art spaces for adults with developmental, mental, and physical disabilities. Although scholars from the fields of Art Education and Disability Studies have acknowledged the important accomplishments of Creative Growth, namely how the artists working there are demonstrating differentiated understandings of art, disability, and teaching, their studies have thus far been limited to brief discussions of individual artists and their works and are lacking in onsite, long-term research (Siebers, 2010; Wexler & Derby, 2015; Wexler, 2016). Long-term research is needed to understand the pedagogy practiced at Creative Growth with their artists.

This paper is rooted in my investigation of the artistic processes and practices of artists with disabilities through field observations at Creative Growth. Through this investigation, I develop the concept of a pedagogy of waiting, which allows for a consideration of embodied differences. This pedagogy of waiting is conceptualized by and with 1) the everyday artistic processes and practices of artists at Creative Growth; 2) my positionality of being a Chinese art educator and researcher in an art studio, Creative Growth, in the United States; and 3) my conceptual and theoretical exploration with philosophers and disability studies scholars. Through these three elements, I argue that the pedagogy of waiting is both informed by people with disabilities and as an alternative to able-bodied and able-minded pedagogies.

My positionality of being a Chinese researcher is essential to how I understand and interpret or misunderstand and misinterpret the artistic and pedagogical practices at Creative Growth. Wu-wei (non-action or effortless action), a Daoist concept from non-western Zhuangzi philosophy (Guo,1961; Slingerland, 2003), has always been an important part of my Chinese cultural background. It has informed my way of thinking and being in the world as a researcher and educator. My embodied understanding of wu-wei affected my presence as a researcher and how I see the artistic and pedagogical practices at Creative Growth.

Among the artists who informed the pedagogy of waiting is Latefa Noorzai, a native Farsi speaker and immigrant to the United States. From my experience being with Latefa in the Creative Growth studio, I argue that her artistic practice at Creative Growth represents a coupled waiting, staff waiting for Latefa as Latefa waited on them. The temporalities demonstrated through Latefa's art practice and the pedagogical practice at Creative Growth challenge the normative temporalities in art learning and art making. The temporal aspect of their practices provides an alternative to able-bodied and able-minded pedagogies.

This article is organized as follows: In section one, "Meeting Latefa Noorzai," I introduce Latefa and describe an encounter between Latefa and former staff member Becki Couch-Alvarado at the Creative Growth Art Center. In section two, "Clock Time," I discuss how clock time or normative narratives of time are constituted as normalized scheduling and pacing that do not account for disability experiences. I also interpret the encounter between Latefa and Becki through the lens of clock time. In section three "Time as Experience," I introduce my theoretical framework of time as experience, which is beyond clock time, and discuss philosopher Henri Bergson's theorization of duration alongside crip time as theorized by disability studies scholars Alison Kafer, Margaret Price, and Ellen Samuels. I then analyze the encounter between Latefa and Becki through the framework of time as experience.

In section four, "Time as Experience, Waiting as Pedagogy," I explain the theoretical basis for what I call a pedagogy of waiting. This pedagogy is based on the time as experience framework introduced in section three and the concept of wu-wei, which goes beyond typical western theories of disability experience. I unpack the pedagogy of waiting by revisiting the encounter between Latefa and Becki and elaborating on the temporal aspect of Creative Growth's pedagogy. I argue that the pedagogy of waiting, like wu-wei, encourages educators to wait to take action and take time in acknowledging their students' differentiated ways of learning.

Figure 1: Latefa Noorzai paints in the quiet studio classroom at Creative Growth. Photo taken by Author in 2019.

Image description: Latefa, a woman wearing a dress with floral patterns in purple, green, and white, sitting in a green chair, in front of an easel with a painting and wood board attached. The painting is a figure with thin black contour lines and green brush strokes. The face and body of the figure are covered with red dots. The lip of the figure is covered with red strokes.

Meeting Latefa Noorzai

Latefa Noorzai (figure 1), who is a native Farsi speaker, started to work at Creative Growth Art Center in 2012. Latefa established herself as an identifiable artist through her portrait paintings with confident outlines and brush strokes. Her paintings are often inspired by fashion magazines (figure 2), and the figures in her paintings often have red lips and big eyes surrounded by bold eyelashes. Latefa also enjoys creating pillows (figure 3) and jewelry. During my fieldwork at Creative Growth, I had an opportunity to work closely with Latefa at a jewelry workshop provided by a textile artist who was a former instructor at Creative Growth. It was at this workshop that I first witnessed Latefa adding writings in her native language (figure 4) to her art projects.

Figure 2: Latefa Noorzai looksat a fashion magazine and drawing in the quiet studio classroom at Creative Growth. Photo taken by Author in 2019.

Image description: Two similar images of Latefa, a woman wearing a grey dress with pink and white stripes and sitting in a grey chair in front of an easel with a drawing and wood board attached. The drawing is a figure with thin black contour lines. The image on the left side is Latefa looking at a fashion magazine. The image on the right side is Latefa drawing the figure.

Figure 3: Latefa Noorzai working on her pillow project in the quiet studio classroom at Creative Growth. Photo taken by Author in 2019.

Image description: Latefa, a woman wearing a grey dress with pink and white stripes, is sitting in a green chair in front of a figure-shaped pillow project. The figure has yellow hair and a pink body. Latefa attaches multicolored cotton balls to the lower part of the figure-shaped pillow's body.

Figure 4: At a jewelry workshop in the kitchen area at Creative Growth, Latefa Noorzai works on a necklace using pieces of fabric on which she wrote Farsi. Photo taken by Author in 2019.

Image description: Latefa, a woman wearing a dress with floral patterns in purple, green, and white, is sitting in a chair and cutting through a piece of black fabric on a table. On the left side are two stacked pieces of fabric. The piece on top is purple with black handwritings in Farsi.

Latefa's primary language is Farsi and the only English words I noticed Latefa used at Creative Growth were "beautiful" and "good morning." Latefa carries on conversations with others using full sentences in Farsi. When she is not in a good mood, her Farsi could be confusing and her conversation is limited to short phrases. According to Creative Growth's records, "the mood triggers are usually in relation to her perception of whether or not she is getting attention and also if she is getting what she wants."

Latefa moved to the United States from Afghanistan two decades ago with her family. Currently, she lives in her own apartment with supportive living services and interacts with a service provider who speaks Farsi. Latefa enjoys the freedom she has staying in her apartment. At home Latefa spends her time knitting, drawing, and writing sentences and watching movies in her native language. Since language seems to be a barrier for Latefa, she does not regularly engage with the community except for walks around the neighborhood and shopping for food or personal items with her service provider. Latefa's sister visits her on occasion and she enjoys socializing with her family.

Latefa attended Creative Growth three days a week. In an interview Creative Growth had with Latefa, she requested to attend Creative Growth five days a week. Since no one at Creative Growth speaks Farsi, most conversations between the staff and Latefa consisted of staff speaking English and Latefa responding in Farsi or non-verbally with facial expressions and gestures. Latefa's service provider spent several days teaching Creative Growth staff some keywords in Farsi that they use with Latefa in the art studio. A list of those keywords was printed and hanging on the wall of a room where Latefa often worked. Because the Creative Growth staff did not speak Farsi, they primarily responded to her facial expressions which included frowning and smiling. All Center staff experimented with different modes of communication and collaborated to support Latefa's art practice.

Latefa arrived at the Creative Growth studio every morning with her walker, frowning, as she walked to her favorite spot facing a window. The staff would speak in English with her in a gentle and pleasing tone to encourage her to move to the quiet studio classroom upstairs that she was assigned to. Sometimes Latefa would frown at the staff to show her unwillingness to go upstairs. Less frequently, she would go directly to her favorite staff member without a frown. Other times, Latefa ignored the staff and returned to her preferred spot downstairs during the day. In other words, Latefa decided when and where to work on her own terms.

Although Creative Growth had classes scheduled for Latefa, her art practice and her interaction with staff depended upon Latefa's alternative arrangements for her time. At one staff meeting, all members agreed to help direct Latefa to her assigned classroom upstairs if they noticed she was alone and isolated in her favorite spot downstairs. Given Latefa's determined personality, and the language barrier, the staff's communication with her became experimental across time and space.

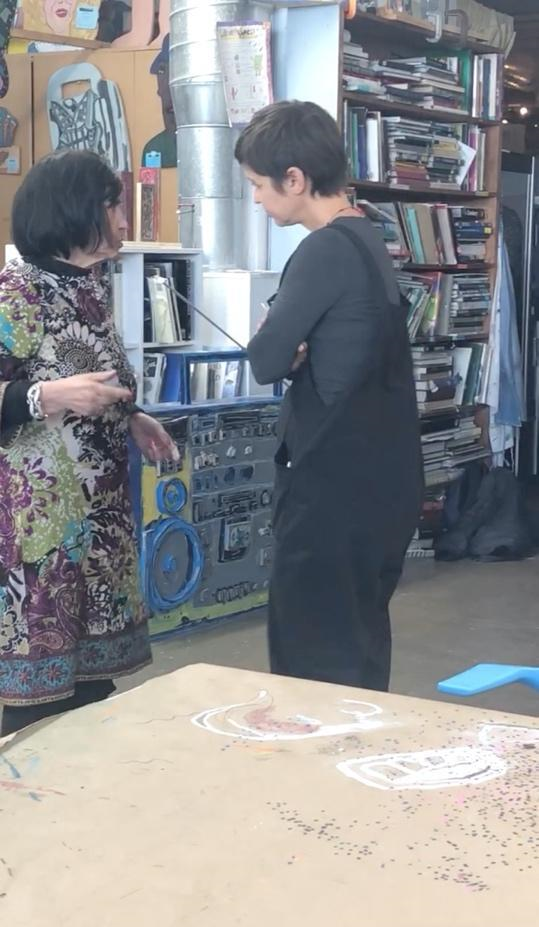

On November 30, 2018, while standing near Creative Growth's library from 2:04 pm to 2:09 pm (figure 5), artist Latefa Noorzai was speaking to Becki Couch-Alvarado, the previous Creative Growth executive director. Becki listened and waited patiently as Latefa spoke and gesticulated. Although she did not understand what Latefa said linguistically, Becki stopped at the intersection of the two hallways and listened to Latefa. Listening and being there with each other were important ways that Becki communicated with Latefa. Becki waited for Latefa as Latefa waited on her as a way to understand each other. At Creative Growth, Latefa's practice challenged normative scheduling practices and staff followed Latefa's arrangement of time. To understand her artistic practice and Creative Growth's pedagogical practice, in the following section, I discuss the first form of time, clock time.

Figure 5: Latefa and Becki stand near the Center's library at the intersection of two main hallways in the studio area at 2:04 pm on November 30, 2018.

Image Description: Latefa, a woman wearing a dress with floral patterns in purple, green, and white, and Becki, a woman, wearing a black jumpsuit and grey long-sleeve T-shirt holding a glass of wine, looking at Latefa. Latefa and Becki stood near the Center's library at the intersection of two main hallways. Behind Latifa and Becki are two artists working, a bookshelf full of books, and wood sculptures hanging on the wall.

Clock Time: Normative, Productive, and Linear Temporality

Normative narratives of time, according to gender studies scholar Jack Halberstam (2005) and disability studies scholars Margaret Price (2011), Alison Kafer (2013), and Ellen Samuels (2017), are normative expectations of when things should happen based on able-bodiedness and able-mindedness. The idea of a norm or normalcy constitutes a "common type or standard, regular, usual''; therefore, it also creates the concept of abnormal when a situation, a body, or a way of being is different from the "standard" or the average (Davis, 2017, p. 2). The norm in temporality assumes not only a linear developmental past-present-future but also an expectation of when things should happen according to clock time. Halberstam (2005) argues that normative temporality influences almost every aspect of human experience, economically and culturally, and assumes a life with "paradigmatic markers of life experience—namely birth, marriage, production, and death" (p. 2). An individual is expected to follow a linear developmental trajectory from dependent child to independent adult.

This linear chronological developmental narrative of time, according to philosopher Henri Bergson, is clock time, a "homogenous medium" that marks experience with a sign or a symbol (Bergson, 1913/2001, p. 90). Clock time, as opposed to experienced time, is thought time, where "quantity" is "projected" as a "homogenous duration," a "numerical multiplicity" (Bergson, 1913/2001, pp. 128-129). Under such temporality, experience is objectified and measured by time, and "the inner states" of experience are constituted "distinct and separate from another" (Guerlac, 2006, p. 96). In other words, there is "the linear narrative development of past-present-future" and what happened in the past is separated from the present (Guerlac, 2006, p. 66). Accordingly, time as quantity is constituted as a tool to measure experience.

Time as quantity and a tool to measure experience has dominated education. In educational contexts, clock time or normative narratives of time are constituted as normalized scheduling and pacing. In other words, educational experiences are measured based on the quantity of time. They are manifested in ways that require students to learn and "perform spontaneously in restricted time frames" (Price, 2011, p. 63). Price (2011) draws attention to how normative assumptions in academics, such as that discussion-oriented classroom settings are better for students' learning, exclude students with disabilities (p. 63). In such settings, students are expected to absorb information and participate immediately in class. Being productive and finishing assignments at "a particular speed" becomes the normal expectation in educational institutions (Price, 2011, p.108). Kafer (2013) considers how such expectations of "productivity, accomplishment, and efficiency" constitute a normality of time and do not account for disability experiences (p. 40).

When it comes to disability experience, temporal terms have always been used to define illness and disability in the medical field, like "chronic," "congenital," and "developmental" (Kafer, 2013, p. 26). Within this normative framework of clock time, disability experience is easily marked as a "delay" or a "detour" from the linear timeline and developmental progress timeline (Kafer, 2013, p.26). Students with disabilities are often described as "retarded" if they do not meet an ideal or average pace of performance. The normalized conceptualization of time influences how disability experience is understood.

With clock time, Becki and Latefa's interaction follows a linear sequence of Becki listening as Latefa speaks from 2:04 pm to 2:09 pm on November 30, 2018. Latefa speaks in Farsi, and then Becki listens, each conversational turn happening one after the other. At 2:10 pm, Latefa moved into the kitchen space alongside the textile instructor, Amy Keefer. During these five minutes, there was no developmental progress regarding communication. Becki did not understand what Latefa was expressing, and Latefa did not receive a response in Farsi. Their communication was not productive or efficient according to normative narratives of time.

As a researcher, I see Becki and Latefa's interaction as more than the clock time. Instead, their encounter demonstrated a temporality that is experience-based and affective. In the next section, I unpack the theoretical framework of time as experience.

Time as Experience: Non-normative, Affective, and Crip Temporality

"How might disability affect one's orientation to time?" Kafer (2013) asks this question in her book Feminist, Queer, Crip in challenging the normative narratives of time (p.26). In asking this question, Kafer (2013) looks for the "'elsewhen'—in which disability is understood otherwise: as political, as valuable, as integral" (p. 3). Disability is often seen as a signal of having a future with limitations "in the service of compulsory able-bodiedness and able-mindedness" (Kafer, 2013, p.27). In exploring ways of being other than the compulsory able-bodiedness and able-mindedness, the "elsewhere" and "elsewhen," it is necessary to look for alternative temporalities that do not mark disability as the "delay," "detour," or "retarded." By "elsewhen," Kafer (2013) refers to alternative temporalities that do not portray disabled people as a "sign of the future of no future" (p. 34). Kafer (2013) uses the term "curative time" to emphasize the assumption that disability always needs intervention in order to be cured (p. 27). To look for the elsewhen is to seek temporalities other than able-bodied/able-minded temporalities.

"Crip time," a term that describes the temporalities of disability, has been used in disability culture and community (Zola, 1988; Price, 2011; Kafer, 2013; Samuels, 2017). "Crip" is not only a noun and adjective but also a verb, meaning to "challenge the order of things" (McRuer, 2018, pp. 21-22). Crip time is being flexible and challenging the normative temporal standard and frames, as Kafer (2013) argues:

Crip time is flex time not just expanded but exploded; it requires reimagining our notions of what can and should happen in time, or recognizing how expectations of "how long things take" are based on very particular minds and bodies. We can then understand the flexibility of crip time as being not only an accommodation to those who need "more" time but also, and perhaps especially, a challenge to normative and normalizing expectations of pace and scheduling. Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds. (p. 27)

Bending the clock to meet disabled people's ways of being exceeds the social model of disability where disabled bodies/minds have to meet the normal standard and therefore need more time. Bending the clock to meet the disabled body/minds means reimagining the notion of time.

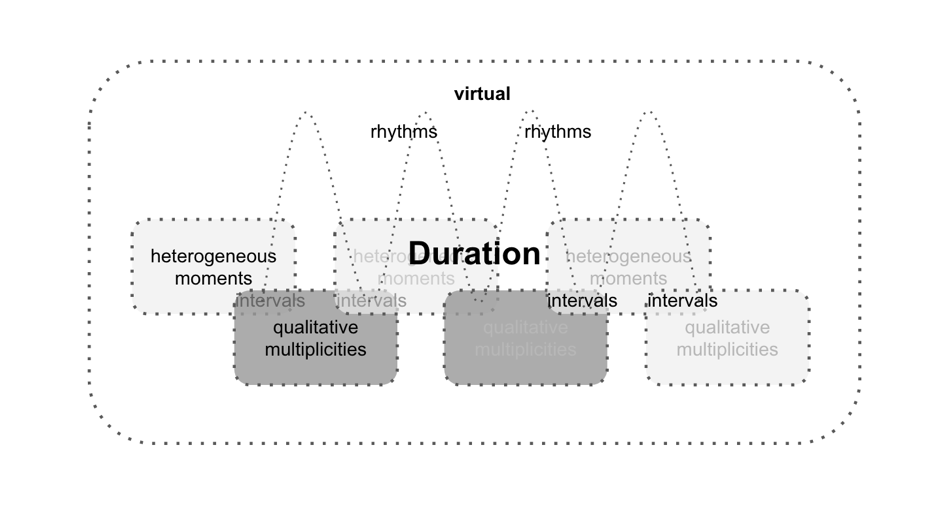

Although Bergson's conceptualization of time is not based on disabled bodies/minds, his speculations about time offer an alternative notion of time other than clock time that often only serves abled bodies/minds. Bergson distinguishes two forms of time with conceptions of multiplicity: clock time and duration. Clock time is quantified. Duration is felt time where "quality" is "produced" as a "true duration," a "qualitative multiplicity" (Bergson, 1913/2001, pp. 128-129).

In duration, Bergson (1911) argues that we live time (Bergson, 1911, p. 46). Duration is "a succession of qualitative changes" (p. 104) or a succession of "heterogeneous moments" (Bergson, 1913/2001, p. 128). For Bergson, these successive moments are not measurable moments. Rather, these changes and moments in duration "melt into and permeate one another" (Bergson, 1913/2001, p. 104). As in the illustration (figure 6), heterogeneous moments unfold and permeate one another as qualitative changes in a duration. As "the inner states" of experience, these moments "continue each other in an endless flow" (Bergson, 1911, p. 3).

Figure 6: An illustration of Henri Bergson's conceptualization of duration by author of this article.

Image description: In the center of this illustration is the word "Duration" in bold text. Behind the word "duration" is a wavy line and two words, "rhythms," "rhythms." Next to the word rhythms is the word "virtual," located at the top of this illustration. Behind the word "duration" and the wavy line are six light grey rectangular text boxes with soft edges;three boxes have the phrase "heterogeneous moments" in them, and the other three text boxes have the phrase "qualitative multiplicities."

This continuous unfolding of heterogeneous moments is time as affective. In Arranging Grief (2007), women's and gender studies scholar Dana Luciano writes about the repetitive and affective states of time. For Luciano, the "affective residue" of the past shows in the present, "permits the feeling body," and "[assesses] the ongoing significance of the past" in the present moment (Luciano, 2007, p. 2). The body becomes an "index of a temporality apart from" the linear developmental paradigm of time. Samuels (2017) contends that this affective aspect of time is consistent with the non-linear flexibility of crip time. The affective aspect of disability experience destabilizes the productivity of abled-bodies/minds (Puar, 2009, p.166).

Based on crip temporalities and time as duration, I argue for time as experience, an experience that is composed of different parts, moments, multiplicities, and rhythms in continuous movement. If time is qualitative multiplicity and we live time, different bodies and minds live time differently as heterogeneous durations; and the succession of moments constitutes disabled people's experience of time which is different from the normative experience of clock time. This form of time, living time, resonates with disability studies scholars' discussion of crip time as "a time of survival" and a time of "world making" (Samuels and Freeman, 2021, p. 249).

Through the framework of time as experience, Becki and Latefa's five minute encounter is constituted of different parts, moments, multiplicities, and rhythms in continuous movement, which is more than what is accounted for by the timestamp of 2:04 pm and 2:09 pm. In what follows, I speculate several "heterogenous moments" that penetrate Latefa and Becki's encounter to constitute duration as qualitative multiplicities (Bergson, 1913/2001, p. 104). Latefa and Becki meet across different temporalities in their waiting on each other even as they experience the encounter differently in duration. What I want to emphasize is that while having pointed out the "2:04 pm" timeframe, the encounter and each moment itself are not motionless but heterogeneous and in movement, or in Bergson's words, each moment "unfold[ing] itself gradually" as duration (Bergson, 1911, p. 9).

On November 30, 2018, Creative Growth Art Center hosted a farewell to Becki, who had served the Center for fifteen years with her last four years as executive director. At 1:10 pm, everyone got together to say farewell to Becki in the main studio on the first floor. Some artists started to hug and talk to Becki. Latefa was in the studio and was also in the group photo (figure 7) that Creative Growth artists and staff took after the farewell.

Figure 7: Creative Growth Artists and Staff Group Photo taken in the Creative Growth Art Center at the farewell to Becki Couch-Alvarado, who had served the Center for fifteen years with her last four years as Executive Director. Photo taken by Author on November 30, 2018.

Image description: A group of thirty-one people, standing and sitting behind two large tables covered with brown paper. In the background of this image are the high ceiling, windows, and lighting of a large studio.

After Latefa and Becki met each other at 2:04 pm, they continued their interaction for five minutes. Although Latefa and Becki stood at the intersection of two paths in the studio as staff and artists were passing by, Becki prioritized Latefa's desire and willingness to engage in conversation. Passersby were aware and respectful of Latefa and Becki's space and moved around them to not disturb their interaction. Since it was during afternoon break time, five artists and six staff members passed by during their conversation. Despite the movement and noise around them and their close proximity, Becki did not break her attention with Latefa (figure 8). Becki's concentrated attention to Latefa functioned as a qualitative element or change that affected the duration of their encounter. Often, Latefa placed her hands and arms on her back while talking with a focused facial expression. Other times, she touched her hair or shook her head with frowns while speaking to Becki. These gestures seemed to convey a complaint Latefa was making.

Figure 8: Latefa and Becki stand near the Center's library at the intersection of two main hallways in the studio area around 2:06 pm on November 30, 2018.

Image description: Latefa, a woman wearing a dress with floral patterns in purple, green, and white, looking at Becki, a woman wearing a black jumpsuit and a grey long-sleeve T-shirt. Latefa and Becki were standing in front of a boombox-shaped wood sculpture and a bookcase full of books.

Although it is unclear what linguistic message Latefa was trying to convey, Latefa's gestures are parts of the multiplicities that constitute their time as experience. Without linguistically understanding the message that Latefa conveyed, Becki chose to listen to Latefa with her full attention. The listening action, together with other qualitative changes in their encounter, constituted a potential to permeate and melt into Latefa's future experiences at Creative Growth; an unmeasured potential "without precise outlines, without any tendency to externalize themselves in relation to one another" (Bergson, 1913/2001, p.104). An interaction without a tendency to externalize predesigned goals is crip time, a time based on Latefa's experience. Arguably, however, this kind of interaction in mainstream educational contexts would be considered nonproductive or a wasting of time.

Time as experience means that time is an experience composed of different parts, moments, multiplicities, and rhythms in movement. The multiplicities and moments that constitute disability experiences in art classrooms have often been overlooked by normative pace, scheduling, and understanding of art learning. Students are expected to finish projects in an expected way with an expected timeline. To challenge this ableist pedagogy, it is important to account for pedagogy that is not based on clock time. I argue that because of time as experience, waiting is a pedagogy. In the next section, I discuss the pedagogy of waiting, a pedagogy informed by people with disabilities and an alternative to able-bodied and able-minded pedagogies.

Time as Experience, Waiting as Pedagogy

If disability affects one's orientation to time and time as experience, it is necessary that art educators reorient their temporality in pedagogy. To do so, educators have to explore the "non-normative temporality" in teaching that is attuned to differentiated parts, moments, multiplicities, and rhythms of students' experiences (Kuppers, 2014, p.51). An art classroom or a studio space will not be inclusive if the students or artists don't have the freedom to make art at their own pace (Gu, 2019). The pedagogical practice at Creative Growth highlights a conceptualization that time is not often practiced in most K-12 art classrooms.

Having stayed at Creative Growth for almost two months, on July 28, 2016, I interviewed Tom di Maria, the Director of Creative Growth at that time, in his office. He described how Creative Growth, as an art center for people with disabilities, supported everyone's unique voices by repeating one word: "wait, wait, wait, and wait." He explained:

We open the door (of a world of creativity), you walk into or you don't, but if you stand at the threshold and wait and not sure if you can cross the door, we (Creative Growth) just wait, wait, wait, and wait. And I've never seen anyone not enter that world (of creativity). They do. You just have to support everyone and you have to let them take the journey in their own way … So, it is difficult to allow for a different process to really evolve in a way that's timeless … A project, is like doing any kind of project, where you kind of starting from what you hope to do. The outcome is defined. We're gonna make Christmas cards … we're gonna draw on a T-shirt. [At] three o'clock we're gonna be done … that's a project ….As opposed to, in two or three years, you can sit in this room and wait, until you are ready to speak visually. (personal communication)

The ways that artists at Creative Growth wait and take their time to be "ready to speak visually" at their own pace manifest the different temporalities practiced at Creative Growth, which challenge normative narratives of time (di Maria, 2016). This practice represents a pedagogical practice that supports the framework of time as experience.

The phrase "wait, wait, wait, and wait" in di Maria's interview starts to function as an affective force to generate encounters and alliances between different elements in my research. This phrase generates connections among the artistic and pedagogical practices I observed at Creative Growth, my understanding of the Chinese philosophical concept of wu-wei, and my teaching experience in China and the United States. All these elements allow me to encounter and coin the concept of the pedagogy of waiting, which I argue captures the pedagogy of the Creative Growth Art Center.

Figure 9: After working on the second floor for a while, without the staff's instruction, Latefa Noorzai decides to crochet at a table facing the windows on the first floor of the Creative Growth studio. Photo taken by Author in 2019.

Image description: Five artists working in a studio space with several tables covered by brown paper. Latefa, a woman wearing a dress with floral patterns in purple, green, and white, is sitting in an orange chair and crocheting by herself at a table with a walker to her right side. Four other artists are working on art projects at different tables.

Wu-wei has always been an important part of my Chinese cultural background. It has informed my way of thinking and being in the world as a researcher and educator. According to Zhuangzi 1 philosophy, what is right is not based on conventional judgments but rather what is "fit" (yi 宜) for the situation at hand (Slingerland, 2003, p. 178). The characteristics of wu-wei involve following (shun 順) the situation and forgetting (wang 忘) the right/wrong judgments of the Self. I argue that when working with people with disabilities, it is important to "follow," not to hold a predetermined image, or in Tom di Maris's words, not to start from "what [we] hope to do," but to wait and allow for what is fitting in disabled peoples' situational relationships with things to emerge (personal communication, July 28, 2016). At Creative Growth, staff "follow" Latefa's alternative arrangements for her time. Sometimes during the day, Latefa would ignore the schedule Creative Growth set up for her and go to her preferred spot downstairs. She would either work on the crochet project (figure 9) she brought from home or start to draw at her favorite spot.

Wu-wei constitutes an effortless state in the very moment a doer performs an action (Slingerland, 2003, p. 7). Metaphorically, this effortless state means being tenuous and having a "lack of exertion" of conscious discriminations, cultural standards, and goal-directed activities (Slingerland, 2003, pp. 16-17). For goal-directed activities, the outcome is defined, and there is no room for experimentation, such as the example di Maria mentioned of making a Christmas card or a T-shirt in three hours in an art classroom. The effortless state that wu-wei embraces resonates with the "structure of sort of no structure" that is practiced at Creative Growth, in which the facilitators have a "lack of exertion" of expecting when an artist should finish an artwork (T. Maria, personal communication, July 28, 2016).

Zhuangzi advocates undoing (jie 解) and forgetting (wang忘) those exertions in order to "[clear] a space" for individuals to conceive of a moving force through "lodging" (yu寓), "fitting" (shi 適), and "properly dwelling" (yi 宜) in the Way 2 (Tao 道). It is the "space" that is cleared that allows unknown things and ideas to emerge. Wu-wei "waits upon (dai 待) things-in-themselves … [to] come to dwell" spontaneously (Slingerland, 2003, p. 190-191). Things-in-themselves for Zhuangzi are "patterned relationships" that constitute the Way (Slingerland, 2003, p. 190-191). I consider these things-in-themselves in wu-wei not only as they resonate with movement in experience but also as they emphasize the temporality of experience.

At Creative Growth, drawing and painting instructor Kathleen Henderson facilitated the beginning of Latefa's day with options for in-progress projects, such as sewing on fabrics and constructing textile sculptures. On each workday, Kathleen either set up an easel for Latefa to paint or suggested a project she had been working . With this suggestion, Kathleen would "wait upon (dai 待)" Latefa's response, her preference, and her "things-in-themselves" on that day at that moment. If Latefa refused the suggestion or showed less interest, Kathleen would bring out Latefa's other projects to see what she would choose to work on. All staff at the Center experimented with different modes of communication and collaborated to support Latefa's art practice. Becki and Latefa's five minute encounter, too, is a waiting that allows "patterned relationships" to emerge in between their experiences.

In applying a wu-wei perspective to researching disabled people's experiences, I must always pay attention to the things-in-disability-experiences, the "nonnormative embodiments," that cannot be recognized by the exertion of previous representations of disability experiences (Mitchell & Snyder, 2015, p. 74). Waiting upon things-in-disability-experiences in teaching sees disability embodiments as a potential for new knowledge and dynamic corporeality that produces alternative ways of being and knowing. To wait for things-in-disability-experiences to emerge in teaching and learning is to take time to acknowledge the multiplicities and histories of students' experiences.

What is happening in a waiting? Bergson (1911) uses an example to explain the atemporality of duration in waiting:

If I want to mix a glass of sugar and water, I must, willy-nilly, wait until the sugar melts. This little fact is big with meaning. For here the time I have to wait is not that mathematical time which would apply equally well to the entire history of the material world, even if that history were spread out instantaneously in space. It coincides with my impatience, that is to say, with a certain portion of my own duration, which I cannot protract or contract as I like. It is no longer something thought, it is something lived. (pp. 12-13)

We experience the "impatience" of time because "how we thought time should run" is different from the durations we are experiencing (Schweizer, 2008, p. 16). The impatience comes from one "would 'like' to lengthen or shorten" the duration they are experiencing to accommodate it (the duration) to their desire (Schweizer, 2008, p. 16). Disability experiences in art classrooms have often been stigmatized as "slow" or "retarded" by the normative desire of pace of art making and art learning. And teachers might experience impatience when working with students with disabilities.

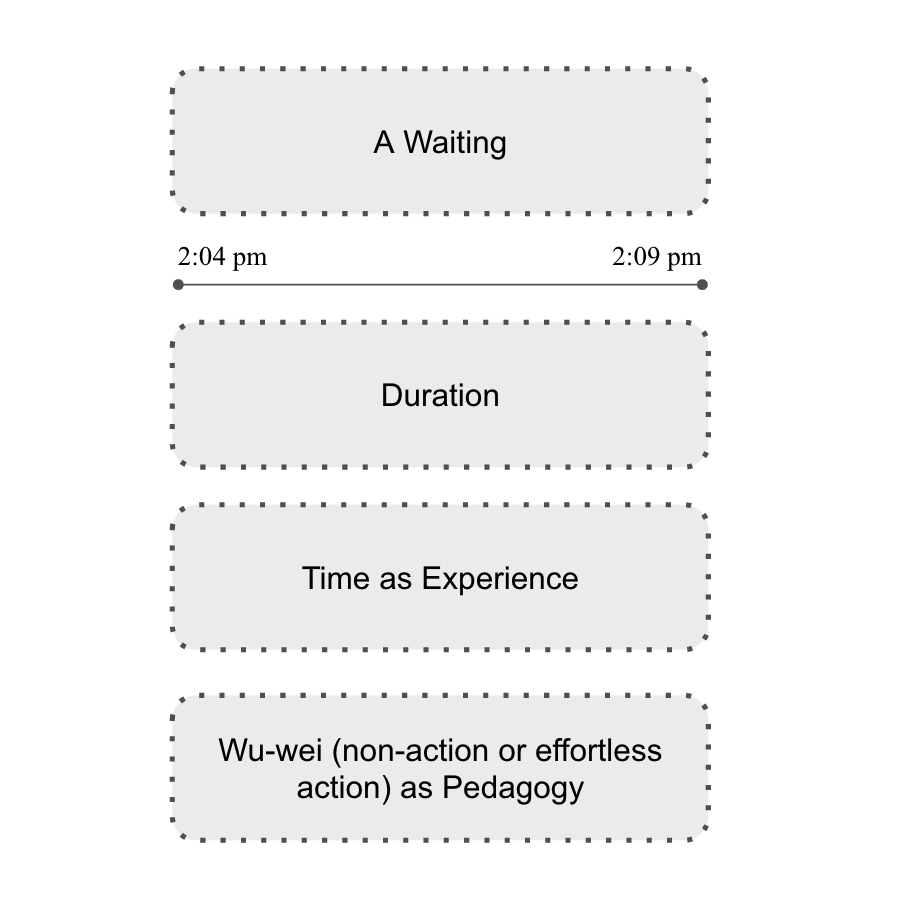

However, it is through "impatience of waiting" that educators are able to recognize normalized able-bodied and able-minded pedagogies. It is the waiting and impatience of waiting through which "the waiter becomes conscious of duration" (Schweizer, 2008, p.16). In other words, the experience of waiting signifies the durations of both the waiter and the waited for. What becomes clear is that in the documented interaction between Latefa and Becki from 2:04 pm to 2:09 pm on November 30, the five minutes that Latefa and Becki shared (figure 10) signifies different durations: Latefa's time as experience and Becki's time as experience.

Figure 10: A Waiting: 2:04 pm to 2:09 pm, November 30, 2018, the five minutes that Latefa and Becki shared together.

Image description: The illustration consists of four rectangular text boxes with soft edges and one black line with marked time stamps. The top text box has the phrase "A waiting" in it. Below this box is a black line with the time stamp "2:04 pm" on the left side and "2:09 pm" on the right side. Below this link are three rectangular text boxes that have phrases in them, "Duration," "Time as Experience" and "Wu-wei (non-action or effortless action) as Pedagogy."

Conclusion

In educational interactions, similar to Latefa and Becki's encounter, each student and each teacher relate to and orient time differently. Time as experience is time as continuous movement between different parts, moments, and multiplicities in experience. As Price (2011) emphasized, it is "flexibility (not just 'extra' time)" that constitutes the temporalities of disability (p. 62). Flex time accounts for how students take in information at different times at different paces. Bending normalized linear temporality refuses the productivity and immediacy of "the logic of capital accumulation" (Halberstam, 2005, p. 7). Beyond flexing time, it is important for educators to continuously practice "self-inquiry" as there will be teaching moments when they "don't consider the needs of all bodyminds" (Kafai, 2021, p. 60). I argue that wu-wei provides a tool for "continual self-inquiry" and the messiness we will encounter (Kafai, 2021, p. 60).

In time as experience, wu-wei offers a pedagogy (figure 9) and methodology that alerts educators to the temporal practices that only serve the able-bodied and able-minded. It encourages educators to forget (wang 忘) and undo (jie 解) those practices that are not serving disability experiences. Wu-wei also pushes teachers to follow (shun 順) the different parts, moments, multiplicities, and rhythms in time as experience.

The pedagogy of waiting, like wu-wei, is attuned to differentiated experiences of students. It encourages educators to take time in acknowledging and accommodating their students' differentiated ways of learning. Waiting constitutes unmeasured potential to encounter the not-yet-known differentiations in the "polyrhythmic movement of crip time" (Kafer, 2021, p.415). As a pedagogy, waiting allows for a consideration of embodied differences in time as experience. It is attuned to non-symbolic, not-externalized movements in bodies that celebrate a slow and sustainable "ethic of pace" that is anti-capitalistic (Bailey, 2021, p.296). It allows time and space for the recurring rhythms in artists' and students' experiences to emerge and encourages their differentiated ways of learning and being in the world.

The waiting between Latefa and Becki (figure 9) constitutes felt time, that is Latefa and Becki's respective experiences of time. Although Latefa and Becki stood at the intersection of two paths, Becki did not move but stood with Latefa. Latafa saw the way Becki nodded at her and in turn was engaged in conversation. Such caring gestures are part of the pedagogy of waiting that is practiced at Creative Growth and applicable to art education classrooms. The pedagogy of waiting respected felt time that unfolded as a relational force to enable Latefa to feel at "home" as an artist at Creative Growth: "I didn't go to school, I never made art," Latefa confided to a Farsi-English translator about Creative Growth, "not until they brought me here. This is my home. This is my Afghanistan" (Creative Growth Art Center, 2020).

When I imagine Latefa watching movies in her native language in her apartment in northern California, I wonder about the sense of being at home that she was referring to when she said, "This is my home." When she walks around her neighborhood in California and shops for food with her service provider who speaks Farsi, I wonder how the experience of time, space, and home differ or interact for Latefa across the national contexts of the United States and Afghanistan. On the one hand, Latefa's immigrant identity placed her out of step with national time given the cultural and linguistic assimilation expectations for immigrants in the United States to learn, communicate, and conduct themselves in English. And on the other, her immigrant identity complexly affected her attunement to ableist time which demands of her a particular kind of temporal assimilation to creativity and community. Considering the moment between Latefa and Becki where Latefa was speaking and gesticulating to Becki, both standing at the intersection of the two hallways at Creative Growth studio, I catch a glimpse of the relation between the two "homes" Latefa experiences. For Latefa, there is a convergence of temporalities and multiplicities in experience. Latefa's art practice and experiences gesture toward a complex intersection of immigration and disability, complexities and particularities of immigrant disablements that I will continue to research and learn with.

Reference

- Bailey, M. (2021). The ethics of pace. South Atlantic Quarterly, 120(2), 285-299. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8916032

- Bergson, H. (1998). Creative evolution (A. Mitchell, Trans.) Dover. (Original work published 1911). https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.166289

- Bergson, H. (2001). Time and free will: An essay on the immediate data of consciousness. (F. L. Pogson, Trans.). Dover. (Original work published 1913)

- Creative Growth Art Center [@greativegrowth]. (2020, April 2). After emigrating to the US from Afghanistan in 2012, #LatefaNoorzai quickly established her art practice at Creative Growth. [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/B-fYclwF_2_/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

- Davis, L. J. (2017). Introduction: Disability, normality, and power. In L. J. Davis. (Ed.), The disability studies reader (pp.1-14). Routledge.

- Gu, M. (2019). Archiving spaces: Walking, murmuring, and writing with artist Nicole Storm. IMAG. The International Society for Education Through Art.

- Guerlac, S. (2006). Thinking in time: An introduction to Henri Bergson. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501716980

- Guo, Q. 郭慶藩. (1961). Zhuangzi Jishi 莊子集釋. Zhonghua Shuju.

- Halberstam, J. (2005). In a queer time and place: Transgender bodies, subcultural lives. New York University Press.

- Kafai, S. (2021). Crip kinship: The disability justice & art activism of Sins Invalid. Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, queer, crip. Indiana University Press.

- Kafer, A. (2021). After crip, crip after. South Atlantic Quarterly, 120 (2), 415-434. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8916158

- Kuppers, P. (2014). Studying disability arts and culture: An introduction. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Luciano, D. (2007). Arranging grief: Sacred time and the body in nineteenth-century America. New York University Press.

- Ludins-Katz, F., & Katz, E. (1983). Art & disability: The Creative art center for people with disabilities. Institution of Art and Disabilities.

- McRuer, R. (2018). Crip times: Disability, globalization, and resistance. New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1pwt9nj

- Mitchell, D. T., & Snyder, S. L. (2015). Biopolitics of disability: Neoliberalism, ablenationalism, and peripheral embodiment. University Of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.7331366

- Price, M. (2011). Mad at school: Rhetorics of mental disability and academic life. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.1612837

- Puar, J. (2009). Prognosis time: Towards a geopolitics of affect, debility and capacity. Women & Performance, 19(2), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/07407700903034147

- Samuels, E. (2017). Six ways of looking at crip time. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(3) https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v37i3.5824

- Samuels, E. & Freeman, E. (2021). Introduction: Crip temporalities. South Atlantic Quarterly, 120 (2), 245-254. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8915937

- Schweizer, H. (2008). On waiting. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203927151

- Siebers, T. (2010). Disability aesthetics. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.1134097

- Slingerland, E. (2007;2003;). Effortless action: Wu-wei as conceptual metaphor and spiritual ideal in early China. Oxford University Press

- Wexler, A., & Derby, J. (2015). Art in institutions: The emergence of (disabled) outsiders. Studies in Art Education, 56(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2015.11518956

- Wexler, A. J. (2016). Re-imagining inclusion/exclusion: Unpacking assumptions and contradictions in arts and special education from a critical disability studies perspective. The Journal of Social Theory in Art Education, 36, 32–42.

- Zhuangzi, & Watson, B. (2013). The complete works of Zhuangzi. Columbia University Press.

Endnotes

-

In this paper Zhuangzi is not referring to a specific individual but to "group of minds" or philosophy revealed in the text called Zhuangzi (Zhuangzi, & Watson, 2013, p.viii).

Return to Text -

Way (Dao in Chinese or Tao in English) is the "underlying unity that embraces man, Nature, and all that is in the universe" (Zhuangzi, & Watson, 2013, p.xi).

Return to Text