Between the popularization of Helen Keller's autobiography, The Story of My Life (1903), and the cinematic dramatization of The Miracle Worker (1962), scenes of Keller's early life and education have served as touchstones through which nondisabled Americans have imagined disability's history and narrowed its political possibilities: toward the conditional dispersal of access based on individual acts of overcoming. Yet, if Keller's story has played an outsize role in consolidating disability's history and politics, it is also a site of profound racial occlusion. The context of Keller's early life on the Keller plantation in Tuscumbia, Alabama is largely absent from her popular legacy. With the disappearance of this context, the black people who facilitated Keller's disabled coming of age have also fallen away, as well as the history of slavery and Indigenous removal that made her life story possible. This void—at the locus of perhaps the most hegemonic origin story of American disability history—is cause for critical race inquiry. This essay traces the relationship between the material background of Keller's autobiography and its imaginative foreground; from her family's role in settler conquest and slavery in the Alabama Muscle Shoals, to Keller's status as a transcendent icon of disability. Reading between the plantation and the plot of Keller's Story while locating both beside the Tennessee River's shoals, this essay turns to theories of cartography and narrative authored by Sylvia Wynter and Tiffany Lethabo King for insight into a critical paradox: the antiblack and anti-Indigenous structure of ableism, and the whiteness of disabled representation. By resituating Keller's iconicity in relation to conquest, slavery, and their afterlives, this essay locates the problems and possibilities of narrating black and Indigenous disability history from the Keller plantation's surround. Yet, while invested in unsettling the landscape, I neither recover these stories nor entomb them as untellable. Instead, I write toward further investment in black and Indigenous counter-archives that have complicated who has been—and who remains—the imaginable and politically traction-able subject of disability.

In what is perhaps the most repeated and remembered scene of The Miracle Worker (1962), Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan, played by Patty Duke and Anne Bancroft, are alone together at a water pump. 1 The bodies of the white woman and the white girl tangle in a physical performance that tautens the underlying struggle between them and the central plot of the film. As teacher, Sullivan's task is to facilitate Keller's reconnection with the English language as a deaf and blind seven-year-old. Until this moment, Sullivan has failed. In the film's few remaining minutes, everything—or, Keller's future in the hearing and seeing world, and Sullivan's employment—hinges on her ability to make the pump make meaning: to get Keller to register that the substance rushing from the spout, and the letters she manually spells into Keller's hand—"w-a-t-e-r"— are a referent and its word; and that, through the use of the manual alphabet, she could communicate about any referent around her. Releasing over an hour of dramatic tension, these connections align suddenly for Keller, the "miracle" crossing Duke's face like a shadow lifting.

Focalizing Keller's moment of comprehension, The Miracle Worker's scene at the pump instilled another set of connections for its audience: it rendered the water pump an index for Keller, and Keller, an icon of American disability history. 2 However much it elevated Keller's story to a dramatic height, the film did not conjure its miracle on its own; it drew its most famous scene from Keller's own narration, set down in her first autobiography, The Story of My Life (1903):

Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly, I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten—a thrill of returning thought; as somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that 'w-a-t-e-r' meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away. 3

Whomever the "some one" drawing the water is, they are immediately swept away by the drama that unfolds after their mention. And indeed that drama is immense: it is the event in Keller's memoir that initiates what Keller deems her "restor[ation] to [her] human heritage," and the end of the "silence and darkness" with which she characterizes her earlier childhood. 4 It is the moment that solidifies her relationship with Sullivan, the teacher later known as Keller's "valiant companion." 5 And it is the pivot in The Story where Keller turns from describing the frustrated, unruly, and violent child she once was, toward writing the self she becomes: the curious and perceptive subject who is recognizable as the autobiographer. Giving structure to Keller's disabled coming of age, the scene at the pump staged Keller's command of her own story, and, by its repetition by others, it helped to solidify Keller as a paradigmatic subject of American disability history. Yet if disability history has been popularly focalized through Keller—and Keller through this story—diverting attention from the story's central plot and toward its surroundings might elucidate something else: an entirely different history of disability; one where the unnamed "some one" in Keller's background not only gains description but critical importance.

Despite its overburdened meaning, the water pump itself can orient toward this other history. In the present, the hallowed pump serves to consecrate Ivy Green, the museum operating from Keller's childhood home in Tuscumbia, Alabama. Drawing visitors as the font of Keller's miracle, the pump also forms a point of departure for mapping the landscape that surrounds it. From the pump, lines between the original Keller dwelling, its several adjacent buildings, and out across the property's expansive lawn make the backdrop to Keller's moment of comprehension legible: as the Keller plantation. Indeed, located an equal distance between the home in which Keller was born in 1880 and a rough looking structure called the "cook's house," the pump diagrams the place of black workers beside and beneath Sullivan's miracle work. Once understood in this relation, the unnamed "some one" who drew the water for Keller and Sullivan gains legibility, too: as one among of the corp of black laborers who cultivated the Keller land and kept their home across Helen's 1880s childhood; and as part of the longer lineage of black laborers, enslaved and free, who had done the same for two generations.

Neither Keller's Story of My Life nor The Miracle Worker hide the presence of black labor, nor the plantation as landscape. In fact, as the enabling role of the water drawer suggests, The Story and the film betray a reliance on the plantation's laborers to bring Keller's subjectivity into coherence, layering a figurative dependence on blackness atop the Keller family's material dependence on black people. Despite the plantation's status as both the formative and preserved background to Keller's story, the Keller plantation has not been acknowledged as a site of critical import in studies of Keller and her iconicity, even as the problem of that iconicity has been grounds for robust and longstanding critique.

Keller's story—of adversity's overcoming and individual advancement in the nondisabled world—has often, and easily, been appropriated to serve a narrow disability politics centered on neurotypical individual rights, conditional accommodations, and the deferral of demands for structural access. 6 For these reasons, Keller's iconicity has been widely understood as problematic: disabled, Deaf, and Deaf/Blind communities, and the field of disability studies, have deconstructed the use of Keller's life story for, rather than against, ableist political projects; moreover, they have also drawn attention to the problem of Keller's own politics: her alignment with the oralist attempt to eradicate Deaf culture, and her involvement in eugenics. 7 Yet if Keller's "southern ties" have occasionally been mentioned as a facet of her identity, the material history of slavery and Indigenous genocide out of which her life, and life story, derived, have remained unregarded. 8

Against this quiescence and toward a reckoning with its racial stakes, I argue that the Keller plantation is key to understanding Keller's representational iconicity, and with it, the representational problem of whiteness in, and as, disability history. A sustained critique of white disabled representation and of disability studies' whiteness in the three decades since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) has exposed the stakes of these interlocking problems; indeed, scholars and disability justice activists such as Christopher Bell, Patty Berne, and Leroy Moore have shown that whiteness has not only limited who is seen as disabled—and thus able to claim the narrow rights afforded by the ADA— but also what political demands can be mobilized through disability as a framework. 9 As scholars of black and Indigenous disability studies including Sami Schalk, Therí Pickens, Helen Meekosha, and Siobhan Senier have written, the framing of disability as an individual, and implicitly white, identity has failed to account for disability's uneven production through structural violence, state policy, medical abuse, and environmental racism, or, the unending legacies of colonialism and slavery. 10 A problem for the present, the bind of whiteness and disability has also rendered colonialism and slavery strangely illegible as disability history, even as their violence lies at the root of ableism, its value system, and its bodily effects. 11

Coupled together, the whiteness of disability and the antiblackness of ableism have made blackness and disability incommensurable in their present and historical intersection, despite their entanglement. This occlusion, moreover, bears intersecting relation to the obfuscation of Indigeneity and disability along similar lines and against shared numerical predominance. 12 Telling, performing, and listening to black and Indigenous stories and theorizations of disability has been, for this reason, vital political work, sustained by black and Indigenous disability justice organizers for decades. 13 Writing as a nondisabled black scholar within black studies, I place this essay behind this work, as an offering from the perspective of cultural history, and as an excavation of what underlies disability's paradigmatic whiteness. I argue that to unsettle the whiteness of disability, we must attend to the material and cultural landscape in which it was established: the plantation and its plot. Tracing disability's white overrepresentation through the history of the Keller plantation, this essay takes guidance from black and Native studies criticism that locates the stakes of any narrative in its setting as much as in its central story.

The setting of story, and the colonial power of cartography, have long been sites of critical geographic intervention in both fields. Through the work of Sylvia Wynter, Katherine McKittrick, Denise Ferreira da Silva, Tiffany Lethabo King, Jodi Byrd, Mishuana Goeman, and others, black studies and Native studies have identified the function of cartography to materially impose settler dominance, and too, to narratively foreclose black and Indigenous people's knowledge, imagination, and counter-navigation of the landscape, past and present. 14 If disability studies' whiteness can be described as a misrepresentation with material effects, taking a critical geographic approach to the Keller plantation reveals the imbrication of the material in the representational, and even more importantly, the specific role of the plantation in structuring what, and whose, stories can be represented on colonized ground.

In her 1971 essay, "Novel and History, Plot and Plantation," Sylvia Wynter identifies the emergence of the novel as the integral corollary to the rise of plantation slavery's socio-economy. In the essay and beyond it, Wynter designates the novel—and literature more broadly—as humanism's autopoietic mechanism, wherein humanism's subject—the Human—plotted, synthesized, and experienced his individuality out of, and above, the conditions of slavery and colonization that produced him. 15 As I argue in this essay, Keller's Story of My Life was deeply enmeshed in the novel's production of liberal individual subjecthood—indeed, Keller's "restor[ation] to [her] human heritage" served as her claim upon a form of subjectivity otherwise disallowed to her as a deaf blind white woman. The coherence of the subjectivity Keller claimed, however, depended materially and figuratively on the histories of Indigenous removal and chattel slavery on which the Keller plantation was built, and on the regime of racial terror that sustained it in the post-Reconstruction period. It also rendered these histories—the conditions of black and Indigenous sickness, injury, death, and life—incoherent in relation to the subject of disability it produced.

Yet, as Wynter writes, and as Katherine McKittrick extends, the logic, or central plot, of the plantation was always internally vulnerable to its marginal plots: areas of land used by enslaved people to sustain themselves in contravention of the plantation's racial economy. 16 The history of the Keller plantation in Tuscumbia, Alabama—on the banks of the Tennessee River where the Muscle Shoals divert its flow—offer minor plots and other features of land and water that can alter the dominant history of disability produced there. Considering plots of enslaved remembrance tended by black residents of the Muscle Shoals area alongside the geological shoals of the region's namesake, this essay advances Wynter's critique of plot and plantation by locating shoals as a third locus, and Tiffany Lethabo King as the theorist of their cartographic intervention. 17 For King, a shoal not only serves "as a site of disruption, a slowing of momentum, and a process of rearrangement," but also as a site that, amidst the water, "enable[s] something else to form, coalesce, and emerge." 18 This essay posits that the history of the now-submerged Muscle Shoals—accretions in the river that troubled white navigation—can surface different meanings in the water spelled and spilt into Keller's hand: both its flow across the plantation, and the violence of Indigenous removal beneath it. 19 Like the shoals, this history asserts itself despite its engineered submergence; it might also form a site for black and Indigenous histories of disability to converge.

Tracing the white supremacist attempt to remove Indigenous life and secure black labor to the land, this essay plots against the absenting of black and Indigenous figures beneath Helen Keller's iconicity. Indeed, allowing the minor plots and shoals of slavery, Indigenous removal, and their afterlives to throw the narrative and material terms of Keller's life story into crisis, this essay reevaluates racialized expendability as the crux of disability history itself, not as its backdrop. Revisiting Keller's central narrative and visiting her landscape, this essay ultimately turns to minor plots of black and Indigenous life, labor, and death in Keller's surround, as histories of disability that can unsettle whiteness, and that might pull ableism up from the same ground.

The Story and Her Life

Helen Keller exists as both a historical subject—whose life can be reconstructed through a series of events between her birth in 1880 and death in 1968—and as a narrative protagonist, whose life has been schematized as a series of scenes that, like the drama at the pump, have been adapted and acted out across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. 20 Indeed, Keller's dual cultural life continues in the present and extends to the future—in the 2021 PBS documentary, "Becoming Helen Keller," and in the forthcoming film, Helen and Teacher. 21 And if The Miracle Worker still claims an outsize dominion over Keller's cultural memory, the film's viability only followed from Keller's renown as both a biographical subject and world-traveling speaker during the middle twentieth century; and too, from the circulation of previous stories told about her, including the play by the same name, and the 1919 film, Deliverance. 22

Behind both her fictional and biographical stature, however, was her turn-of-the-century memoir, The Story of My Life. A text that hews closely to the conventions of the bildungsroman as both the paradigmatic arc of the novel and the structure of memoir, Keller's disabled coming-of-age story established the narrative basis out of which her public iconicity grew. 23 Chronicling scenes of the "darkness" before Sullivan's arrival and then enacting the educational "miracle" by which Sullivan "set [her] spirit free;" The Story propels Keller in widening circles of "worldly [and] sentimental education," that eventually deliver the young adult narrator who writes from Radcliffe College, and who, through her reflections, offers audiences the story of triumph that has been so often retraced. 24

Locating the source of Keller's legacy in her own writing as a twenty-two-year-old overstates her agency in the complex formation and appropriation of her iconicity; it also misses how her Story, and its popularity, were built from the interplay of her original writerly voice and the familiar subjectivity she captured through it. 25 Keller's disabled coming-of-age story poses both a radical challenge to the presumed nondisabled, male subject of the bildungsroman, at the same time that it cultivates a conventional "mode of humanness produced through inequalities," and "set free to realize [its] individuality by the 'liberal' values" supported by those inequalities; race, chiefly among them. 26 Indeed, Keller's memoir fulfills the "plantation['s] logic" and its owner-class arc. The Story produces Keller as a protagonist able to transcend the plantation's geography and to traverse the wider world, ultimately enabling the plantation's obfuscation as the site from which its plot arises. 27 Yet if the Keller plantation fades from popular recollections of Keller much as it fades into the background of The Story, it necessarily reappears in each retelling. It is the landscape in which Keller's struggle for selfhood unfolds. It is the site of the miracle. And it remains a physical "shrine" to her memory. 28

In its current manifestation as a museum, Ivy Green operates less as an evidentiary appendix to The Story than as the narrative's materialization. Ivy Green's promotional texts and guided tour keep close to the arc, anecdotes, and language of Keller's memoir; and indeed, the fictive and material bounds of Ivy Green dissolve more fully under the pressure of The Miracle Worker, performed each year on its grounds. 29 To visit Ivy Green is not to encounter a census of the plantation or its people during Keller's childhood, but to visit the setting and select characters of Keller's early life, calibrated somewhere between Keller's telling and others' retellings. Though, where The Story and The Miracle Worker both invoke named and unnamed black laborers as caretakers, cooks, and keepers of the Keller house, the only black laborer memorialized at Ivy Green by name—and first name only—is Viney, who stands in for all.

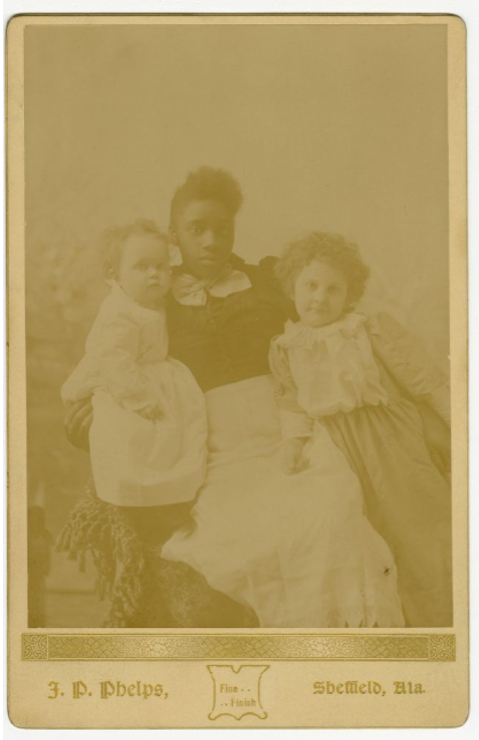

The "cook's house," a structure of an adjoined bedroom and kitchen behind the Keller home, is said to have been Viney's dwelling. Viney is also housed in a different sense within the Keller home, immortalized in a glass-encased photograph of a black woman holding Helen's younger siblings, Mildred and Phillips Brooks, on her lap (figure 1). 30 Beyond Viney, there are no other direct representations of black labor at Ivy Green. Yet the few unlabeled cabins dotting the acreage are a suggestion of what the census confirms: that at the time of her birth in 1880, Helen's father, Arthur Keller, employed a fulltime corp of black laborers to cultivate his five acres of cotton, keep his fruit orchards, raise his fourteen cows, nineteen pigs, and twenty chickens; to tend his two mules and horse, chop his timber, and to otherwise sustain the plantation's operations. 31

Stretching Viney's presence across this wide and diversely-skilled assembly of black workers obscures the labor and presence of others, such as Sophia Napier Watkins, who is remembered by her descendant, Tom McKnight, as the Keller's cook. 32 It also obscures Viney herself. The woman called Viney in Helen's Story, played by (the uncredited) Beah Richards in The Miracle Worker, and remembered as the cook, housekeeper, and nurse at Ivy Green in the present, bears fictive relation to Viney Kee Murphy, whose descendants, Carolyn Lewis and Donna Cooley Vinson, have done careful work to reconstruct her life. 33 Born enslaved in 1857, Viney Kee married William Murphy, and worked for the Kellers across the 1880s and 1890s. Based on Lewis and Vinson's research, it does not seem that she inhabited the cook's house, but that she lived nearby in her own home on Cave Street. And if the "cook's house" did not house her, the photograph might not, either. Viney was the mother to several children, including Ella Murphy, who may have been Ella, the "young nurse" that Helen recalls in her memoir. 34 Indeed, given the likeness of the photograph to Viney—but the portrait sitter's very youthful appearance— it may be Ella who looks back from the photograph, not her mother. 35 Just as depictions of Viney may conceal as much as they clarify, other portraits in Ivy Green offer similar suggestions while withholding definitive histories.

Hanging on Ivy Green's second floor landing, portraits of President George Washington and First Lady Martha Washington recall the presence of another Martha Washington whom Keller drafted into a pivotal role in her Story. 36 A young black girl, Martha Washington, acts as Keller's central playmate and target of abuse before Sullivan's arrival. However important to the story, Washington proves archivally enigmatic: because Martha Washington was not the name of a real girl, but a pseudonym for Mariah Watkins. 37 Where details of the real Viney Kee Murphy demystify the plantation's mythologies, the fiction that covers Watkins is a guide of a different kind: to the plantation imaginary that Keller drew upon to write her memoir, and to its racial scripts: of white and black girlhood, of precious and expendable bodies, and of immanent and transcendent subjectivities. As rendered by Keller, Washington surfaces Ivy Green's literary, not historical, genealogy:

Two little children were seated on the veranda steps one hot July afternoon. One was black as ebony, with little bunches of fuzzy hair tied with shoestrings sticking out all over her head like corkscrews. The other was white, with long golden curls. One child was six years old, the other two or three years older. The younger child was blind—that was I—and the other was Martha Washington. 38

Though Keller locates this scene in Alabama in 1886, it might have been 1850 in Louisiana, imagined by Harriet Beecher Stowe in her 1852 novel. For, in picturing the whiteness of her girlhood beside the abject blackness of Martha Washington's, Keller called up Uncle Tom's Cabin's iconic racial dyad of Eva St. Clare and Topsy: "The fair, high-bred child, with her golden head, her deep eyes, her spiritual, noble brow, and prince-like movements; and her black, keen, subtle, cringing, yet acute neighbor." 39 Eva and Topsy's cultural life across the late nineteenth century—in caricature, on stage, in song, and in material culture—would not likely have missed Keller's notice, nor could their usefulness in setting a plantation scene. 40

Keller quickly plunges this couplet of racial representation into confusion, however. Filled with mischief, Keller "turn[s] [her] attention"—and sharp scissors—to Washington's hair. Though Washington "object[s]," she eventually "submit[s]" to Keller. 41 When Washington attempts to "cut off one of [Keller's] curls," however, Keller's golden head is saved by her mother's arrival. 42 Temporarily embodying the "wickedness" associated with Topsy, the scene nevertheless ends with the protection of Keller's golden hair, white body, and "racial innocence;" in so doing, it anticipates the memoir's reinstatement of Keller in Eva's place, as well as her Eva-like cultural ascent. 43

Uncle Tom's Cabin does not figure in the literary autobiography that Keller supplies at the end of her memoir, where she credits works from Little Lord Fauntleroy, and The Scarlet Letter, to the Odyssey in shaping her imagination. 44 This intertextual mapping, however, functions less as a key to Keller's allusions than as a canonical lineage out of which her voice emerges both legitimate and original. Indeed, Keller's discussion of her reading is undertaken in explicit regard to questions of her authorial legitimacy, following from her pained disclosure of the cruel and humiliating consequences that befell her at the age of twelve, when a story she published, "The Frost King," was interrogated for plagiarism. 45

Keller's statement, that "even now I cannot be quite sure of the boundary line between my ideas and those I find in books," admits her ongoing unease (or perceptive awareness) of the porousness of imagination, even as The Story performs her mastery of the authorial "I." 46 Keller's worrying over her own permeability— and her achievement of a singular Life Story—triangulates the immense demand on Keller to prove her self-possessed individuality as a disabled writer. It also points to how she satisfied that demand: through the use and disposal of Topsy and Eva both.

Just as Keller assembles her tableau of black and white girlhood only to unsettle it, Eva and Topsy's broader use in her memoir is not in their stability, but in their motion. Despite Keller's contention that she inhabited a "still, dark world," the kinesthetics of black and white girlhood predominate her early chronicles, rendered in Keller's narration of her outbursts at Washington, and magnified on screen in Deliverance, where Keller's attack on Washington creates a blur between the two girls (figure 2). 47 In fact, this variegation runs more deeply through the plot; it externalizes Keller's internal struggle in her "darkness," where she inhabits the status, vulnerability, and appearance of Eva, yet acts with the reckless physical excess associated with Topsy. And if this struggle is only an overture to her memoir's larger account of her life, it is the central struggle dramatized to excess in The Miracle Worker, where Duke's portrayal of Keller's physicality is the object of the camera's unceasing interest. 48 While long recognized as a crude depiction of a disabled body as always, and in all ways, excessive, Duke's excess should also be recognized as racialized—drawn from Topsy's cultural repertoire. Duke lines this out in the tap-dance-like choreography of a pivotal scene, and marks it again when she smears black ink upon her face. 49

Keller's return to her "human heritage,"—in both memoir and film—washes away the darkness, resettling her into Eva's embodied whiteness and bodily transcendence. In the memoir, Keller's eyes fill with tears and her heart with empathy; in the film, she embraces her family, teacher, and the word "love." Yet if Keller becomes more synchronous with Eva's innocent white girlhood, she does not, importantly, come to Eva's end. Eva plays her part in Stowe's plot by dying of her illness; she ascends as an effigy, not in the action of a protagonist. Keller, for her part, takes Eva's mantle of innocent, disabled white girlhood to inhabit it differently: she survives, speaks, and comes of age. She turns her empathy and innocence outward toward her family and her landscape—taking in the plantation's "daisies and buttercups," "warm fields," "gracious shade," and "bursting cotton bolls," as "first lessons in the beneficence of nature." 50 Overcoming the status of a plantation fixture herself, Keller makes herself the plantation's surveyor, and in so doing, begins her protagonist's journey.

Martha Washington, Viney, and the other black characters who populate Keller's darkness disappear from The Story at this juncture. Even Nancy—Keller's ragdoll who takes abuse Washington escapes— deflates into a "formless heap of cotton." 51 If Nancy was only a doll, and Martha Washington not a real depiction of Mariah Watkins, the receding profile of black figures into the landscape still warrants inquiry, exemplifying the harvesting of plantation for plot that Wynter theorizes, and echoing Toni Morrison's identification of "playing in the dark" as the white protagonist's staging ground. 52 Yet, because The Story is a memoir—where fictive and material plantation histories cross—both the disappearance of Washington, and the caricaturing of Watkins, demand a different curiosity.

It takes nothing away from Keller, except innocence, to notice the black people exploited in the making, and telling, of her life story. For indeed, it was not just Keller's Story that arose from the plantation's figurative economy, it was her life that was sustained, and her education first funded, therein. If we account for the labor beneath Keller's self-making—not only acting as her playmate and taking her abuse, but also preparing her family's food, keeping their house, hauling their water, and picking their cotton for generations— the plantation's effects on black laborers bodies, minds, reproductive lives, sense of safety, and futures—rises up from the background of Keller's individual story as a question: could one write a story of disability wherein slavery's afterlife—the conditions that shaped the lives of Kee Murphy, Watkins, and Keller—was legible as the plot? If reading for figures in the background of Keller's Story suggests the presence of alternative stories but cannot produce them, the history beneath the plantation—of conquest, settlement, slavery, and post-slavery terror, distills meaning from what Keller's story blurs.

Under the Ivy Green

The inability to read Keller's life story and the afterlife of slavery as the same story is the result of sedimented obfuscation: by Keller's narrative omissions, by biographers' selections, and by mingled neglect and forgetting. This obfuscation is even abetted by the architecture of Ivy Green. Looking at Ivy Green's face in a photograph, or even positioned before it, the white clapboard house appears diminutive: a cottage, entirely lacking the columned grandeur that makes other plantations of the Muscle Shoals recognizable as such. 53 From the outside looking on, Ivy Green does not give itself away as a seat of slaveholding power. Yet, positioning oneself on Ivy Green's steps and turning outward provides a reorientation for understanding. The lawn sprawling before and behind the house, the smaller buildings in its background, and the massive magnolia trees that flank it begin to intimate the home's history as a compound of white wealth. Indeed, if the house appears small, it is in part by comparison to the massive size of its original allotment: the over six hundred acres on which the house was built in 1820. 54 By entering the home, the wealth produced across that acreage becomes vividly condensed as luxury. The home's two-stories and high ceilings, drawing rooms, fire places, dining room, and three bedrooms communicate that profit was pulled up from the land and channeled into the family by speculation and slavery. Moreover, the Cherokee or Chickasaw materials found under and around Ivy Green—a clay pipe and a dozen arrowheads now housed in its "museum case"—underscore that speculation and slavery succeeded rapidly from conquest and Indigenous removal. 55

The verdant survey of Ivy Green that Keller sets as the backdrop to her lessons with Sullivan delineates this history. Keller's description of walking her pony through Ivy Green's pastures, of "men […] preparing the earth for seed," of the "large, downy peaches," growing in its orchard, of horses in the stable, of cows giving milk, and of travels to her family's Fern Quarry, suggest the diverse agriculture undertaken by the plantation's black workers. 56 And too, Keller's stories of "play[ing] at learning geography" by building "dams of pebbles, ma[king] islands and lakes, and diggings river-beds," at "Keller's landing" produces a miniature survey of intergenerational relation to the surveys that brought her family, among other white settlers, to the Tennessee River's banks. 57

Helen's grandfather, David Daniel Keller, staked his claim by the Tennessee River's bend in the immediate aftermath of a survey conducted there in 1817, which was itself only the quickening of the much longer Anglo-American militarized expansion into lands of Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek, and Yuchi peoples. 58 Purchasing some of the earliest tracts sold by the U.S. Government in what became the northwest corner of the state of Alabama in 1819, Keller participated in the expanding empire of Andrew Jackson's material, political, and personal investment. Indeed, Jackson had initiated the survey, and following its findings, he purchased 642 acres of land for himself. 59 John Coffee, whom Jackson tasked as surveyor, went on to become a major agent of Chickasaw removal, and one of the wealthiest planters on their former land. He was also, not incidentally, Jackson's relative. 60 Though never reaching the scale of the Coffee plantation, Keller also intended for his roughly 640 acres to be worked by enslaved people. According to the census, he succeeded in this ambition, enslaving at least forty-nine people by 1830. 61 Chronicles of the Kellers note that David Keller "sold his farm" to become a railroad superintendent before his death in 1836. 62 However, the land still owned, and the people still enslaved, by the Kellers across the middle century suggests, at least, a more complex picture. In 1850, sixteen black people were still enslaved on the Keller plantation, with Mary Keller, David's widow, listed as their "owner." 63

Though the names of these people are not given in the ledgers that list them as property, the census identifies that the youngest person enslaved by the Kellers in 1850 was a six-month-old girl; the eldest, a forty-five-year-old man. 64 Little else in this record individuates these people, or the lives or subjectivities of the fourteen others beside them. However, placing those enumerated but unnamed in the 1850 census in relation to names that appear in 1880 provides some indefinite suggestion of life beyond slavery's ledgers. In 1880, the Keller family into which Helen was born was listed as living near five other households with the last name Keller, all of them black. Among them was Alfred Keller, who was forty and "worked on a farm," and sixty-five-year-old Nancy Keller, listed as widowed and "disabled." 65

The Keller name alone tells little about the lives, work, or disabilities of Alfred or Nancy. But the history of plantation slavery that tied their names together offers more. Indeed, identifying what grew at that history's center—cotton—gives dimension to the speculative dream and brutal regime into which David Keller invested his, and others, lives. Hundreds of miles from Alabama's black belt, the Muscle Shoals region was nevertheless involved in cotton's interconnected economy, generation of white wealth, and grueling enslaved labor regime. This economy, and the desire to stake a claim in it, was what spurred the largescale migration of white settlers into Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana; it was the prospect at the base of Jackson's empire, and it was made possible by the violent removal of Indigenous people—whose involvement in slavery white settlers had first helped to instill, and then sought to eradicate. 66 Requiring initial brutality for its establishment, the "Cotton Kingdom" depended equally on extremely brutal labor conditions for stability. 67

As Walter Johnson has detailed, planting, picking, cleaning, packing, and shipping cotton was punishing work for the enslaved people who did it, from very young ages to very old. Economized into "full hands" and fractions of "hands" based on age, gender, and apparent "soundness," enslaved people lived and worked under a rubric for the abled body that was distinct in its exploitability and fast expiration. 68 Indeed, the history of ableism is both stretched to excess and collapsed by the history of conquest, cotton, and slavery's other monocultures, which obsessively evaluated the bodies of the enslaved while placing them on what Stefanie Hunt-Kennedy has called the continuum "between fitness and death." 69 As Hunt-Kennedy elaborates, this history disrupts the story of the able, normal, or ideal body narrated through white wage labor or middle class leisure. When read through the enforced fungibility of black life and the attempted eradication of Indigenous life, as opposed to the value—even exploited— of white life, race appears not as a weight altering ableism's scales, but as its underlying logic.

By finely calibrating the expenditure of enslaved labor and its limit, slaveholders used those they enslaved to extract as much value from the land as possible, and then to move as much of that value as they could to market. 70 Planters in the Muscle Shoals believed they had calculated well, for not only was the soil "deep and fertile and particularly suited for cotton growing," but the land's place on "the Tennessee River held forth […] the vision of cheap transportation to the primary market of New Orleans." 71

The cotton economy was buoyed, and vexed, by the flow of water in the Muscle Shoals. From the outset of their arrival white settlers attempted to engineer a thoroughfare for steamboats to move goods between the Tennessee and Mississippi Rivers. The shoals, however, got in the way. Large accretions of limestone, sandstone, shale, and chert laying in the middle of the river like semi-hidden islands, the shoals persistently imperiled cargo vessels and spurred decades of projects to submerge them—all unsuccessful until the construction of massive dams in the 1920s and 1930s. 72 Materially disruptive to the vision of settler planters, the shoals can also intervene in how we read the history of their vision. As King theorizes, shoals impede the "narrativity" of white progress itself, surfacing "a tension and a friction" of that which was subjected, yet not subdued, beneath it. 73

In the midst of this history and its faltering, Keller's childhood play at dam-building was both backward and forward facing; she learned her region's geography in a time when speculator's first vision for the river's "improvement" had been dashed—by the shoals and black Emancipation—and before the twentieth-century's second vision—for massive energy-generating dams—had begun. 74 Though poised between the two, the region was not static in the post-Reconstruction period; Helen's family lived atop wealth while still generating more profit. After serving as a captain in the Confederate army, Arthur Keller returned to his inherited land and status to establish himself as a lawyer, real-estate broker, and as editor of the North Alabamian. 75 And, during Helen's childhood, he added an additional 120 acres to his property. 76 Indeed, though he died in debt in 1896, the plantation that Helen was born into in 1880 was not a decadent outpost of the Lost Cause as has often been suggested; it was a site of white wealth's recuperation and the recapture of black labor after slavery's end. 77

"Strange, Wonderful Fruit"

"To-morrow, to the chase!" was the "good-night shout" of the white men who "whiled away" hours in "talk and sport" at Fern Quarry with Keller's father in her recollection. 78 A vision of comradery and of Keller's enjoyment among the hunting party, this scene unfolds as another vignette in Keller's loving and lush recollection of her childhood landscape. Not taking part in the hunt, Keller's joy does not arise from the sport of the kill, but from the time spent at the "rough camp" with the Confederate men "among oaks and pines." 79 Indeed, the hunt ends without bloodshed, as the men come back without any prey. The scene, nevertheless, teems with an undercurrent of violence, intimated not in the hunt, but in the relations of the white men to the black workers who attend them in the woods. Keller's mention of the "negroes" standing "[a]round the fire," to "driv[e] away the flies with long branches," from the "savoury" meat they prepared for the hunting party raises a startling diagram beneath the trees and below The Story's central plot. 80 Not only does this scene convey the contrast between white leisure and black labor, it also begins to surface another history between white propertied men and black laborers among the trees.

During the period chronicled in Keller's memoir, there were five (recorded) lynchings of black men by white mobs in and around Tuscumbia. The names of those murdered were Tony Wilson, Thomas Black, John Williams, Jesse Underwood, and Oscar Coger. In almost all of these killings, "attempted arson" was offered as a justification. 81 In the case of nineteen-year-old Underwood, the supposed crime for which he was murdered was indecency toward a white girl. 82 These killings were not unusual, but part of a history of lynching in the Muscle Shoals that stretched back at least to the murder a black and Cherokee preacher, Reverend Robin Lightfoot in 1864, and forward to killings in the twentieth century. 83 There is no record of Keller's knowledge of this history, nor of her experience of these murders, nor is there a precise way of measuring Keller's physical or affective distance from them.

Yet, even without assigning an indexical relationship between Keller's recollections and these murders, it remains possible to read Keller's attention to her landscape in tandem with the history of lynching that conditioned the material, aesthetic, and affective qualities of that landscape—both for the black people targeted by terror, and for the white owner class whose power was secured by it. Lynching established white household security by creating a climate where black social or labor unrest was deadly. As Sandy Alexandre has written, enforcing the outside-yet-suspended place of black people through each spectacle, lynching aestheticized the inability of black people to claim the land or stand on the ground. 84 And, as Virginia Thomas writes, while lynching's location outside affirmed "white land ownership and control," it also demarcated the interior space of white families as a sanctum defended by any means. 85 As Thomas continues, to be among the trees, to climb them, or to represent them—on landscapes where trees were "scaffold[s]" to lynching violence—became an articulation of racial power, whether implicitly or explicitly registered. 86

Keller's rowdy forest banquet, her memoir's mapping of the "wild cherry tree a short distance from [her] house," her refuge taken beneath a "wild tulip tree," and her climb up the plantation's "mimosa tree," take on meaning as deposits of an available lynching imaginary and landscape in context of this. 87 Indeed, through her vividly rendered trees, Keller extends and alters Jacqueline Goldsby's argument that lynching structured the visual field, with Keller marking lynching's wider aesthetic and sensory reach. 88 If deciding Keller's consciousness of lynching, or its aesthetics, is beside the point of this essay, the presence of lynching violence—especially as apposite to The Story's "great event[s]"—presents a problem central to this essay's interest in elucidating the plantation as it has structured what is known of, and as, disability history. 89

Nowhere does this problem rise to more striking disturbance than in a scene of Keller's utmost childhood enjoyment: "the first Christmas after Miss Sullivan came to Tuscumbia," in 1887, described with anticipation and "greatest delight." 90

Every evening, seated round a glowing wood fire, we played our guessing game, which grew more and more exciting as Christmas approached. […] On Christmas Eve the Tuscumbia schoolchildren had their tree, to which they invited me. In the centre of the schoolroom stood a beautiful tree ablaze and shimmering in the soft light, its branches loaded with strange, wonderful fruit. It was a moment of supreme happiness. I danced and capered round the tree in an ecstasy. 91

Puncturing the quiet after Christmas, and on the second day of the new year, white men of the Tuscumbia area murdered a forty-five-year-old black man named Oscar Coger. Helen may not have known of this. But her father certainly did, as he included a one sentence report on Coger's murder in his newspaper: "Oscar Coger, colored, was lynched at Cherokee, Ala on the 2d." 92 The brevity of the notice, and its placement among the week's "Condensed Telegrams," underscores the status of the murder as an event, and at the same time, the need for no elaboration. In its lack of description of Coger and its avoidance of naming his killers, the notice suggests itself as a complete entry, requiring no further reporting or action. It tells nothing of Coger's supposed crime, and nothing of Coger, who is not afforded the status as a victim; and who, in other reports, is cast as a punished perpetrator. 93 But Coger can be glimpsed in partial view through other records: as a farmer who married a woman named Clara Vaughn in 1881, and as the father of Basha Coger, who would have been the same age as Helen in 1888, when Coger was murdered. 94

Whether Keller knew any of this, she did not write it into her Story, nor did she leave a record elsewhere. Indeed, Keller's Story describes nothing of January 1888 except the death of her pet bird. For Keller, "The next important event in [her] life was [her] visit to Boston in May, 1888," which opens the next chapter in her education. 95 Yet, if the space between Keller's Christmas chronicle and the new year's killing of Coger cannot be bridged through her writing, their connection nevertheless existed in her social and affective surround. Keller's evocative description of white children dancing with "supreme happiness" around a blazing Christmas tree—its "branches loaded with strange, wonderful fruit," may have been an unconscious invocation of lynching aesthetics, or an accidental one. Regardless of her intent, the scene she describes of ecstatic white children encircling a decorated tree inside was connected to the scene of a white mob encircling another laden tree outside. They were populated by parents and children of the same community and history, inflecting different shades of the same sublime. 96

In the absence of extant black testimony about Coger and his death, Arthur Keller's authority as editor, and Helen Keller's as author, would have effectively maintained the gap between these two scenes, and even widened it. Indeed, Arthur Keller's attribution of the killing to the (nearby) area of Cherokee—discrepant with other reports that place it in Tuscumbia—creates further distance. Yet the murder, and the landscape of racial terror which produced it, rises almost to the surface of Keller's story. Like the shoals in the water, the killing of Oscar Coger catches at the bottom of Keller's language, revealing itself as only ever just submerged.

Indeed, once recognized, more details accumulate in this submerged story. Other newspapers offered two details about Coger's murder that Arthur Keller left out. The first, that Coger's killers took his life, like the lives of several others, for the supposed crime of attempted arson; the second, that "the negroes [we]re indignant over the lynching," and that "there [wa]s considerable excitement." 97 If the second statement reveals outrage, grief, and potential action taken by Coger's community, the mention of attempted arson, too, reveals something. The claim that Coger and many other lynching victims sought to burn white property—even understood as a fabrication—diagrams the sanctity of white property and its monopolization under white supremacy, as well as the danger faced by black people willing to struggle over it. This danger and struggle continued. In 1894, a "regular correspondent" from Tuscumbia intimated both under another thin veil:

About 100 colored families left here last night for Texas, Louisiana and other points Southwest. Fully 500 colored farmers have left our county since Christmas. Our people continue to follow strange gods. […] The negro has only been free a few years, and yet some are seemingly anxious to put themselves under task masters. Our people have got to learn that there is more to be gained by economy and earnest labor than by running from place to place looking for rich soil and easy living. 98

Three months later, a band of white men—supposed avengers of another attempted arson— orchestrated the triple murder of Tony Wilson, Thomas Black, and John Williams over the Tennessee River. 99

What was "easy living" in the context of this terror? Or in a place where former enslavers, whose ancestors had taken hundreds of acres of "rich soil" by conquest, made land ownership precarious or dangerous for the formerly enslaved? These fragments of antiblack violence and black labor history reveal that there was a pitched struggle over life, and its value, taking place in the background of the struggle that drives Keller's memoir. What has maintained the distance between this history and Keller's Story is the sense that they are about different things: one pertaining to race, the other to disability; one specific to this place, the other transcendent above it. These distinctions not only conceal the enmeshment of Keller's disabled white life within the terrain of racial struggle; they also cede the terms, subject, and plot of disability to Keller's Story entirely. Yet if we unhinge disability history from "life story" as its plot, we can admit black death as part of it. Moreover, if we recognize on whom a life story's subject has depended for coherence, we can begin to reckon with whiteness where it undermines, rather than merely overrepresents, what we tell of disability's history.

To reconnect the plot and plantation of disability history requires unsettling Keller's place in it. But not removing her from it. Indeed, this essay does not propose to replace Keller's story with another. Not because black and Indigenous disabled people did not live alongside Keller, for they certainly did. Nor because their stories are impossible to decipher, though they certainly are more difficult to find in full. Rather, this essay forgoes telling an alternative life story in order to remain with the critical impasse presented by black death as it subtends Keller's Story, and with the problem of white disabled representation, as it has both relied on and disappeared disabled black and Indigenous life. Rather than leave Keller behind, we might instead follow her leaving—North, toward education and greater individual access—as it runs in tension with other departures from her landscape: West and South West, toward reservations in Oklahoma and toward different "task masters" in Louisiana and Texas. If these journeys spatialize the major plot of disability history as it attempts to leave the plantation behind, the plantation's remaining minor plots might tell us something, too.

Plots of Remembrance, Deposits in the Water

Extending Wynter's "Novel and History, Plot and Plantation," to the question of "Plantation Futures," McKittrick has drawn out the spatial and temporal impossibility of leaving the plantation behind, living, as we do, in the afterlife of slavery. 100 And while she does not discretely name ableism in her discussion of antiblackness, her emphasis on the present soundness of the plantation underscores the incompleteness of each aforementioned departure, as well as the need to return to the plantation to decipher how its major plot acts on disability history in the present. McKittrick also reminds us, however, that in and around this major plot, minor plots have been planted, sustained, kept, and remembered. Referring, like Wynter, to the plots used by enslaved people to grow food, McKittrick points too, to the plantation's figuratively disruptive plots, or, where the plantation system and "a creative space to challenge this system," arise simultaneously. 101 These self-exposing stories housed within the dominant one might take several forms: like the description of "strange, wonderful fruit" on a Christmas tree; or like arrowheads found under, and encased within, a plantation museum; or like portraits of George and Martha Washington hung on its walls. Considering these as manifestations of what McKittrick calls "plot-life," I turn, at this essay's end, to consider plot-life for the dead; the ongoing remembrance of slavery and Indigenous removal in the Muscle Shoals; and the shoals in the water themselves. 102

Though Keller is the principal subject enshrined in Tuscumbia, residents in the surrounding area continue to tend to other histories less widely known or named. Like those who uplift the local memory of black composer, W.C. Handy, and like Lewis and Vinson, who have kept Viney Kee Murphy's history from fading into her effigy, other residents have worked to maintain histories of lesser known enslaved and free black people against their submergence. Across the water from Ivy Green, the Armistead Cemetery in Florence, Alabama, comprises a small, shaded plot filled with stone graves and many crosses made from PVC pipes. The crosses—nearly fifty—were made and placed by Jessie Smith, a black Vietnam war veteran, who, as vice president of the Armistead Cemetery Foundation, works alongside other Armistead descendants to keep the remembrance of ancestors who lived and died on the Armistead plantation. 103 A few miles away in another clearing, a small fence demarcates the resting place of roughly 130 enslaved people, who lay in minimally marked graves beside the ornate graveyard of their enslaver, John Coffee—the surveyor who reshaped the Muscle Shoals for white empire, cotton, and capital. Now, both his graveyard and the graves of those he enslaved lay in the shadow of capital in the present: a Walmart constructed against opposition by Coffee's descendants and other residents who sought to maintain the resting place. 104

Like the overruled resistance to Walmart, these minor plots of remembrance do not necessarily alter the course of the plantation's dominant plot. Nor are they interventions in Keller's Story in particular. Nevertheless, these plots of remembrance act upon, and in, the landscape; they produce a different story beside Keller's, and they raise notable relations of entanglement, interdependence, and contrast in the collective and individual lives they mark. These plots of remembrance offer cause for traversing a different geography around the Keller shrine; and indeed, the trip I made with a friend to visit Keller's site was crossed by the massive course of another sojourn of remembrance: that of thousands of motorcyclists who rumbled the asphalt and altered traffic patterns as part of the annual Trail of Tears Ride, commemorating the forced departures of Cherokee and Chickasaw people from Waterloo, Alabama. 105 Complex in its own formation of politics, identities, and histories, the massive movement of bodies and machines across the Muscle Shoals nevertheless intervened in our intended itinerary around Keller, making it impossible to visit her memory without perceiving what else filled her surround.

Other things remained harder to perceive: the shoals themselves. Placing ourselves on the Tuscumbia side of the Tennessee River, what we witnessed below were not the shoals, but the massive Wilson Dam which had covered them. A project begun in 1919 to generate power for an Ammonium Nitrate plant, and completed in the 1930s for the Tennessee Valley Authority's hydroelectric system, the Wilson Dam represents the colossal engineering, labor, and skill of the area's black and white workers, and bears its own twentieth-century history of race, labor, environment, and disability. In the present, small rocky islands rise from the low water immediately beneath the dam. Scrutinizing them, my friend and I asked each other if they might be part of the shoals. We left unsure. And when we asked local residents if, and where, we could find the shoals, they returned gentle but amazed responses: didn't we know, we were in the Shoals? In the course of this history, and in the aftermath of their damming, the Muscle Shoals—word and referent—have largely lost their connection.

Even if we did not identify them, reconnecting the meaning of the place and its namesake remains important for surfacing the history that runs through the water. Submerged under the flow of white projects of empire, slavery, capital, labor, and life; the shoals were also deposits in the water that troubled those projects. In that way, their meaning and their materiality are deeply entwined; as is their relationship to Keller's history and Story. For this reason, we must, at last, return to the water pump. Despite its status as a tired representation of Keller's place within disability history, the pump is also an index of a story that has not been told, and that could not be told, as long as Keller was its sole subject, protagonist, and icon. But there was, and remains, another story to be drawn from the water. When we recognize the "some one" else at the pump, we can begin to tell it. 106

figure 1. Viney Kee Murphy (or Ella Murphy) with Phillips Brooks Keller and Mildred Keller, 1893. A black woman sits at the center of the photograph. She is holding a white baby in one arm, and a white child is leaning on her other side. The woman is wearing a dark dress with a large light-colored bow at her neck, and a white apron from her waist down. The photograph is on a yellowing cabinet card, and the image is framed by text beneath it: "F.P. Phelps, Sheffield, Ala." (Courtesy of Perkins School for the Blind, Watertown, Ma).

figure 2. "Martha Washington" and Helen Keller, from Deliverance (1919). A black and white image of two blurred figures. One figure is a black girl (Washington) wearing a white dress, the other is a white girl (Keller) whose arms are outstretched toward Washington's head. You cannot see either girl's face. Porch steps and tangled tree branches fill their background. (Library of Congress Online. https://www.loc.gov/item/mbrs00093858/).

Endnotes

-

The Miracle Worker, directed by Arthur Penn (Playfilm Productions, 1962).

Return to Text -

Mary Klages, Woeful Afflictions: Disability and Sentimentality in Victorian America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 197. https://doi.org/10.9783/9781512807899

Return to Text -

Keller, The Story of My Life (New York: Signet Classics, 2010) 16. [Doubleday Page & Co, 1903].

Return to Text -

Keller, The Story, 11; 5.

Return to Text -

Helen E. Waite, Valiant Companions: Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy (Philadelphia: McRae Smith, 1959).

Return to Text -

Georgina Kleege, "Helen Keller and the Empire of the Normal," American Quarterly 52 no. 2 (2000): 322-325. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2000.0018

Return to Text -

Katie Booth, The Invention of Miracles: Language, Power, and Alexander Graham Bell's Quest to End Deafness (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021), 301-306; Georgina Kleege, Blind Rage: Letters to Helen Keller (Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 2006).

Return to Text -

Kim Nielsen, "The Southern Ties of Helen Keller," Journal of Southern History 73 no. 4 (2007), 783-784, https://doi.org/10.2307/27649568. See also: Andy Prettol, "Racism, Disable-ism, and Heterosexism in the Making of Helen Keller," Comparative Literature and Culture 10 no. 2 (2008): 2-9, https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1353

Return to Text -

Christopher Bell, "Introducing White Disability Studies: A Modest Proposal," The Disability Studies Reader, 2nd edition, edited by Lennard J. Davis (New York: Routledge, 2006); Patty Berne, Aurora Levins Morales, and David Langstaff, Sins Invalid, "Ten Principles of Disability Justice," Women's Studies Quarterly 46, no. 1-2 (2018) 227-230, https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2018.0003; Leroy Moore, Jr. "Black Disability: from Hiding to Displaying," in "Developing and Reflecting on a Black Disability Studies Pedagogy: Work from the National Black Disability Coalition," Disability Studies Quarterly, 35 no. 2 (May 2015), https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4637

Return to Text -

Sami Schalk, Black Disability Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022), 2, 6-7, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478027003; Dea Boster, African American Slavery and Disability: Bodies, Property, and Power in the Antebellum South, 1800-1860 (New York: Routledge, 2013), 2; Helen Meekosha, "Decolonising Disability: Thinking and Acting Globally," Disability & Society, 26 no. 6 (2011): 667-682, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.602860; Therí Pickens, "Blackness and Disability: The Remix," CLA Journal 64 no. 1 (2021):3-10, https://doi.org/10.1353/caj.2021.0004; Siobhan Senier, "Disability in Indigenous Literature," The Routledge Companion to Literature and Disability (New York: Routledge, 2020), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315173047-3

Return to Text -

Juliet Larkin-Gilmore, Ella Callow, and Susan Burch, "Indigeneity & Disability: Kinship, Place, and Knowledge-Making," Disability Studies Quarterly 41 no. 4 (Fall 2021). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v41i4.8542

Return to Text -

Between a quarter to a third of black and Native adults in the U.S. have a disability, a significantly higher proportion than adults of other "racial and ethnic" groups tracked by the CDC. "Adults with Disabilities: Ethnicity and Race," www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/materials/infographic-disabilities-ethnicity-race.html.

Return to Text -

For one lineage of this work, see Sins Invalid, Skin, Tooth, and Bone: The Basis of Movement is People, A Disability Justice Primer, 2nd edition (2019); Shaydah Kafai, Crip Kinship: The Disability Justice and Art Activism of Sins Invalid (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021).

Return to Text -

Critical geography encompasses a range of methodological and ethical interventions across black and Indigenous studies, within and beyond the field of geography itself. As one non-exhaustive lineage, I cite Sylvia Wynter, "Novel and History, Plot and Plantation," Savacou, no. 5 (June 1971): 95-102; Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006); Denise Ferreira da Silva, Toward a Global Idea of Race (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); Jodi Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (University of Minnesota Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816676408.001.0001; Mishuana Goeman, Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations (University of Minnesota Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816677900.001.0001; and Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Duke UP, 2019).

Return to Text -

Sylvia Wynter, "Novel and History, Plot and Plantation," Savacou, no. 5 (June 1971): 95-102.

Return to Text -

Katherine McKittrick, "Plantation Futures," Small Axe 17, no 3 (November 2013), 10. https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-2378892

Return to Text -

Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 21.

Return to Text -

King, 31; 11.

Return to Text -

King, 35.

Return to Text -

Klages, Woeful Afflictions, 197.

Return to Text -

American Masters, episode 35, "Becoming Helen Keller," directed by Michael Pressman, aired October 19, 2021, PBS; "Millicent Simmonds and Rachel Brosnahan Are the Iconic Duo Helen & Teacher," Vulture, October 14, 2021, Vulture.com.

Return to Text -

Deliverance, directed by George Foster Platt (1919), Library of Congress.

Return to Text -

John Frow, Melissa Harie, and Vanessa Smith, "The Bildungsroman: Form and Transformations," Textual Practice 34 no. 12 (Fall 2020): 1905-1910. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2020.1834692

Return to Text -

Keller, 5.

Return to Text -

Klages, 189.

Return to Text -

McKittrick, "Plantation Futures," 9; Wynter, "Novel and History," 97.

Return to Text -

McKittrick, 11; Wynter, 97.

Return to Text -

"Ivy Green: Helen Keller Birthplace," Visit Florence, https://www.visitflorenceal.com/directory/ivy-green-helen-keller-birthplace/

Return to Text -

"Ivy Green: Helen Keller Birthplace," Visit Florence, https://www.visitflorenceal.com/directory/ivy-green-helen-keller-birthplace/

Return to Text -

The photograph's label at the Keller Birthplace reads: "Philips Brooks Keller, brother of Helen; Viney, nurse; Mildred Keller, sister of Helen," [undated].

Return to Text -

Arthur Keller employed an exclusively "colored" workforce all fifty-two weeks of 1979-1880. Enumerations of the plantation's value, acreage, crops, and livestock appear under "Arthur Keller," 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Schedule 2, Productions in Agriculture in Township 4, Range 11, in the County of Colbert, State of Alabama. Enumerated 12-14, June 1880, Ancestry Library Edition.

Return to Text -

Sophia Napier Watkins, "Helen Keller Family Cook," African American Local History Collection, Florence Lauderdale Public Library. On the extensive research of Watkins's descendant, Tom McKnight, see also "Closure on 109 Years: Two Headstones Recognize Fred and Sophia Watkins," Courier Journal (Florence, AL), June 2, 2020.

Return to Text -

Carolyn Lewis and Donna Cooley Vinson have done extensive research to reconstruct Viney Kee Murphy's life and family. I spoke with Lewis and Vinson by phone on September 20, 2021.

Return to Text -

"Viney Kee Murphy," 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Schedule 1. Inhabitants in South Florence [illeg] in the United States in the County of Colbert in the State of Alabama, June 1, 1880. Ancestry Library Edition; conversation with Carolyn Lewis and Donna Cooley Vinson, September 20, 2021.

Return to Text -

Ella would have been fourteen in 1893; Viney, thirty-six. I make this speculation (of my own) based on the 1893 photograph's resemblance to another known photograph of Viney.

Return to Text -

The portraits are not original to the house.

Return to Text -

Helen names Washington as the daughter of "the cook." This was likely Mariah Watkins, (or Maria), Sophia Napier Watkins's niece. See "Maria Watkins," 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Schedule 1, Inhabitants of Township 4, Range 11, in the County of Colbert, State of Alabama. Enumerated 22-23, June 1880, Ancestry Library Edition. See also Tom McKnight, "A Genealogy Journey of 14,496 Miles in 86 Days, Part II," Reconnected Roots (Blog), June 9, 2010.

Return to Text -

Keller, 8.

Return to Text -

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin, Or Life Among the Lowly (New York: Penguin, 1998) [1852], 268.

Return to Text -

On Eva and Topsy's cultural life, see Robin Bernstein, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: New York University Press, 2011), 30-32.

Return to Text -

Keller, 8.

Return to Text -

Keller, 8.

Return to Text -

Bernstein, 113-127.

Return to Text -

Keller, 78-79.

Return to Text -

Keller, 46-48.

Return to Text -

Keller, 47.

Return to Text -

Keller, 15-16.

Return to Text -

Klages, 205.

Return to Text -

On Topsy's repertoire, see Jayna Brown, Babylon Girls: Black Women Performers and the Shaping of the Modern (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 67.

Return to Text -

Keller, 17, 19, 24.

Return to Text -

Keller, 32.

Return to Text -

Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (New York: Random House, 1992), 6, 13.

Return to Text -

For instance, the columned structures of Belle Mont in Tuscumbia, and the remains of Forks of Cypress, in Florence.

Return to Text -

Margaret Mathews Cowart, Old Land Records of Colbert, County, Alabama, (Huntsville, AL: M.M. Cowart, 1985), 67, 75-77.

Return to Text -

Labeled "Indian Peace Pipe," and "Indian Artifacts," the specific tribal origins of these arrowheads and the clay or catlinite pipe are, at this time, still unclear to me.

Return to Text -

Keller, 7; 17; 24-25.

Return to Text -

Keller, 17; 25.

Return to Text -

J. Haden Alldredge, Mildred Burnham Spottswood, Vera V. Anderson, John H. Goff and Robert M. La Forge. A History of Navigation on the Tennessee River System; an interpretation of the economic influence of this river system on the Tennessee valley. Transportation economics division, Tennessee valley authority. (Washington, U.S. Govt. printing office, 1937), 3. Box 31, Folder 1.7, William Lindsey McDonald Papers, Collier Library, University of North Alabama.

Return to Text -

Cowart, Old Land Records, 68.

Return to Text -

"John C. Coffee," 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Schedule 2, "Slave Inhabitants," Ancestry Library Edition. See also Amanda Page, Fuller Bumpers, and Daniel Littlefield Jr., Chickasaw Removal (Ada, Oklahoma: Chickasaw Press, 2010), 25; 35-38.

Return to Text -

"David Puller [David Keller]," 1830 United States Federal Census, Tuscumbia, Franklin County, Alabama, Ancestry Library Edition.

Return to Text -

Arthur Keller, "History of Tuscumbia," in Northern Alabama, Historical and Biographical Illustrated, edited by T. A. DeLand and A. Davis Smithy (1888).

Return to Text -

"Mary Keller," 1850 United States Federal Census, Schedule 2, "Slave Inhabitants," Tuscumbia, Franklin County, Alabama, Ancestry Library Edition.

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

"Alfred Keller"; "Nancy Keller," in 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Schedule 1, Inhabitants of Township 4, Range 11, in the County of Colbert in the State of Alabama, enumerated, June 1, June 3, 1880, Ancestry Library Edition.

Return to Text -

Barbara Krauthamer, Black Slaves, Indian Masters: Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 6-7; 31-35.

Return to Text -

Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013), 4-8. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjsf5q7. Page et al, Chickasaw Removal, 25.

Return to Text -

Johnson, 152-154.

Return to Text -

Stefanie Hunt-Kennedy, Between Fitness and Death: Disability and Slavery in the Caribbean (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2020), 10; 71. https://doi.org/10.5622/illinois/9780252043192.001.0001

Return to Text -

Johnson, 244-250.

Return to Text -

Alldredge et al, 40.

Return to Text -

Alldredge et al, 60-64; W.F. Prouty, "Geology of the Muscle Shoals Area, Alabama," Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 38, no. 1/2 (1922), 88-89; Nancy Grant, TVA and Black Americans: Planning for the Status Quo (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990).

Return to Text -

King, 21; 114.

Return to Text -

Alldredge, et al., 145.

Return to Text -

The 1880 census lists Keller's ownership of an agricultural estate and printing (newspaper) business. Keller advertised for his real estate firm in the newspaper. See [Advertisement] "Rather, Keller, and Johnson," North Alabamian, December 16, 1888, Microfiche, Florence-Lauderdale Public Library.

Return to Text -

Cowart, 89.

Return to Text -

"Arthur Keller U.S. Wills and Probate Record," August 27, 1896, Ancestry Library Edition. PBS's 2021 documentary Becoming Helen Keller contends that: "they were not rich." See also Neilsen, 784.

Return to Text -

Keller, 37.

Return to Text -

Keller, 37.

Return to Text -

Keller, 38.

Return to Text -

"An Incendiary Lynched," Atlanta Constitution, Jan 3, 1888, ProQuest; "Around in Alabama," Columbus Daily Enquirer, June 29, 1891, Readex; "Triple Alabama Lynching," Courier Journal (Louisville, KY), April 23, 1894, ProQuest.

Return to Text -

"Around in Alabama," Columbus Daily Enquirer, June 29, 1891, Readex.

Return to Text -

An account of Reverend Lightfoot's killing in 1864 appears in the personal diary of a Mrs. Eliza Bedford Weakley, in Sallie Independence Foster Collection, University of North Alabama. On the murder of Sam Davenport in 1909, see "Negro is Lynched for Barn Burning," Atlanta Constitution, January 25, 1909, ProQuest.

Return to Text -

Sandy Alexandre, "Out on a Limb: The Spatial Politics of Lynching Photography," Mississippi Quarterly, 61 no.1 (2008): 76, 89.

Return to Text -

Virginia Thomas, "Black Tree Play: learning from anti-lynching ecologies in the 'Life and Times' of an American Called Pauli Murray," feminist review, no. 125 (2020), 77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141778920918582

Return to Text -

Thomas, "Black Tree Play," 80.

Return to Text -

Keller, 18, 19.

Return to Text -

Jacqueline Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 280-281. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226791982.001.0001

Return to Text -

Keller, 29.

Return to Text -

Keller, 29.

Return to Text -

Keller, 29.

Return to Text -

"Condensed Telegrams," North Alabamian, January 6, 1888, Microfiche, Florence-Lauderdale Public Library.

Return to Text -

"They Swung him Up," Austin Daily Statesman, January 3, 1888, ProQuest; "A Negro Fire-bug," Courier Journal (Louisville, KY), January 3, 1888, ProQuest.

Return to Text -

"Oscar Coger," 1880 Federal Census, Schedule 1, Chickasaw, Colbert County, Alabama, Ancestry Library Edition; Marriage License of Oscar Coger and Clara Vaughn, Colbert County, State of Alabama, July 4, 1881, Ancestry Library Edition.

Return to Text -

Keller, 31.

Return to Text -

On lynching and the sublime, see Goldsby, 221; 281.

Return to Text -

"They Swung him Up," Austin Daily Statesman, January 3, 1888, ProQuest.

Return to Text -

"Tuscumbia Notes," Huntsville Gazette, January 27, 1894, Readex.

Return to Text -

"Triple Alabama Lynching," Courier Journal (Louisville, KY), April 23, 1894, ProQuest.

Return to Text -

McKittrick, 2.

Return to Text -

McKittrick, 10-11.

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

I learned about the work of the Armistead Cemetery Foundation from Jessie Smith on September 16, 2021. We spoke again on March 15, 2022. Professor George Makowski also offered invaluable insight about work done by community members and University of North Alabama students and faculty to locate and protect this gravesite and others. We spoke on March 24, 2022. See also, Kendyl Hollingsworth, "Research Leads to Discovery of Former Slaves Burial Site," Times Daily, https://www.timesdaily.com/news/research-leads-to-discovery-of-former-slaves-burial-site/article_a90170d6-31e6-55d3-878f-a3149baed38a.html.

Return to Text -

Robbie Brown, "Slave Graves, Somewhere, Complicate a Walmart's Path," New York Times, May 15, 2012; Russ Corey, "City resident concerned about upkeep at Coffee slave cemetery," February 10, 2022, Times Daily, https://www.timesdaily.com/news/city-resident-concerned-about-upkeep-at-coffee-slave-cemetery/article_12399160-160e-538f-9e61-ad37353ed8db.html.

Return to Text -

The ride has drawn thousands since 1994. See Zak Sos, "Trail of Tears Ride Commemorates Dark Days in Native American History," WHNT News 19, September 19, 2021, whnt.com/news/trail-of-tears-ride. See also: "Trail of Tears Motorcycle Ride," https://www.al-tn-trailoftears.net/the-ride/introduction.

Return to Text -

Thank you to the anonymous reviewers of this essay for your insight, and to the special issue editors for your guidance. Thank you, as well, to Virginia Thomas, for your presence and support; and to Rachel Kolb, for many conversations. And deepest appreciation to Carolyn Lewis, Donna Cooley Vinson, and Jessie Smith, whose knowledge and generosity made my writing possible.

Return to Text