The problem of urban accessibility for persons with mobility restrictions has been for some years a subject of discussion both within academic communities and communities of physically restricted transit users. Some have argued the issue lies within the spaces created by those whose experience of the city is dependent on transit rather than automobile use, or who use wheelchairs rather than walk. This paper attempts to advance what has been a largely experiential literature into a more sustained argument that develops a program to describe the altered spaces created by different transit modalities for users with different abilities. With a review of the literature it begins with the author's own experience and the means by which it led to a new transit initiative focused upon surface analytics in transit analysis rather than a more traditional mode of consideration.

Keywords: automobile, bus, disability, surface analysis, transit systems

Introduction

I saw him as I limped up the short, ten-degree grade that leads from the bookstore to the department of geography at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. There was a tinge of envy as I watched this young fellow in his 20's drive his convertible into a parking space perhaps 5 meters from where I rested on my cane. This was six months after total hip replacement surgery required by my osteoarthritis. His door flew open and, reaching around, the driver flung out a wheelchair into which he slid, rolling away far faster than I could walk.

"Who is disabled, here?" I muttered. The paraplegic drove and I cannot, having given up my motor vehicle license 20 years earlier because of vision deficits. He rolled quickly, and probably without pain, where I limped slowly with chronic pain. Yes, my prognosis was good, there would be a day when I didn't use a cane and there would not be one where he gave up his wheelchair. On this day, however, the world seemed more difficult, more restricted for me than for him.

Making my way slowly toward the geography building I wondered about the nature of impairments and the limits they impose, the world they create. What did it mean to be a 20-something, wheelchair-mobile car driver in a city; how was that different from being a middle-aged, sight-impaired fellow with a cane? Was my world in fact restricted because I cannot drive? Is it in some way limited by my reliance on transit?

Having written about disability ethics I was familiar with the broad arguments of both physical limits and their social construction (Koch 2001; 2006a; 2006b). Here, however, the broad issues were focused in the built environment and there the data seems … sparse. The problem is clear: "people adjust their preferences to what they think they can achieve" (Nussbaum 2006, 73). But to what extent might my impairments limit what I saw as achievable. How is being unable to drive, and perhaps to use a bus, a limit that forces us to adjust our goals and does that limit our lives?

The more I looked the more I came to understood that the real problem in thinking about this problem is the method in which we think about transit, the methodology constructed to frame questions and seek answers about accessibility. Understanding, and perhaps reconstructing, our view of the environment as a traversable surface became the goal of a project whose origins were personal and broadly conceptual but whose end is concrete and pragmatic.

Literature: Geography

There are two pertinent literatures here, one is geographic and the other a "disability literature." Many have described in a general way the affect of physical limits on urban access and mobility, the broad differences between "enabling" (Gleeson 2002, 201) and conversely inhibiting environments. Eric Britton described the changing circumstances of his mother's life as her Parkinson's disease progressed (Britton 2002); I described the limits — social and physical — my father experienced in a "geriatric decline" (Koch 1990). Reginald Golledge has written extensively, alone and with others, on "disability, barriers, and discrimination," from the perspective of the blind (Golledge 1994, Marston, Golledge and Costanzo 1997).

Within this broad literature is a subset concerning limits on urban accessibility based not on the physical characteristics of the person alone but on the structure of transport systems that connect the built environments in which we live. The consensus seems to be that what Porter called "the simplistic equation of impairment with disability" is unsustainable when, as she discovered, a quadriplegic with a motorized wheelchair and adapted motor van was more mobile and "independent" than many with less extreme physical limits (Porter 2002, 12). My observation, clearly, was not unique.

What Porter calls "transit disability" defines in a general way limits to urban access based on one's mode of transportation and the inability of some bus travel, for example, to match the access of others, especially automobile use. But what is meant by this, and how it is to be understood, is unclear in Porter's work or that of other researchers. The problem was framed in a general way in 1993 by Golledge who suggested, as Church and Marston have noted, that "even when considering the exact same geographic space, people with differing abilities must use, access, and travel through that environment using different routes, such that the conception and use of that space is 'transformed' for different users" (Church and Marston 2003, 12). The problem, therefore, is not simply in the location of this or that barrier but in the space created by different routes and different modes of travel for users with different capabilities.

While this makes intuitive sense, it flies in the face of decades of transportation studies. There space is assumed to be democratically uniform and constant irrespective of the mode of transportation or the abilities of users. Its topology is typically expressed as a collection of lines (streets, bus routes, airline routes) and points (street intersections, bus stops, airline terminals) that permit regular access to and egress from across the regular and unchanging space of the city or state (Taffe and Gauthier 1973).

The systems we use to design urban systems and measure their accessibility all rely on this idea of a space that can be measured in simple and regular units of time and distance such that ten miles will take twice as long to travel as five miles. By the late 1960s, a series of algorithms had been developed in which graph theoretic modeling was employed to design interactive systems at a range of scales (the city, the nation, and the world) based on this idea of a single and regular space accessible by all (Haggett 1967). Those equations remain the very essence of our thinking today (for a review see Church and Marston 2003).

But what if persons with mobility disorders, and persons who cannot drive, in fact are relegated by the transit system to a very different space? How might this different space be understood, its origins described? Geographies of disability, while rich in "the everyday geographies of people with disability, chronic illness, and psychiatric problems" ( Dyck and O'Brien 2003) hold no answers to the broader problem.

This paper details an attempt to come to grips with this idea of non-regular spaces as a function of mobility limits and transit systems. It offers no answers and is less a report of "work-in-progress" than a pre-study whose outcome is a proposed means of defining a methodology that might better express the variable spaces in which we live. This paper describes the first stage of a research initiative, one that grounded in individual experience will lead, hopefully, to a more complete and complex spatial metric capable of describing transit modalities and the method they construct different spaces affecting users differently. Through a careful consideration of a single case, questions are raised and methodologies proposed for future application.

Disability and Impairment

While concrete and geographic in its subject and analysis, the result will certainly bear upon the greater issues of social exclusion and inclusion of persons of difference. For more than a generation debate has continued over the degree to which physical limits and the social context in which they are enacted influence daily life activities and life quality. A "social disability model" argues, to paraphrase Tremain, "disablement is nothing to do with the [physical] body, impairment is nothing less than a description of the body" (Tremain 2005, 9). My impairments — low vision and mobility restrictions — are physical realities but any limits they present in daily life, in this trope, result form a failure in social infrastructure support, the real "disablement." In considering the space created by transit modalities, the nature of that infrastructure itself becomes the subject.

Once a principal proponent of the social disability model, British sociologist Tom Shakespeare recently has argued the dichotomies of disablement/impairment, of physical realities and social barriers, are too simple. "Disability studies would be better off without the social model, which has become fatally undermined by its own contractions and inadequacies" (Shakespeare 2006, 28). It is not that social realities are unimportant, Shakespeare insists, but that they exist within a context in which the physical difference is real and not necessarily society's responsibility to address. A vast literature has grown around the poles of disability and impairment, of clinical reality and social responsibility, one rich in theory if not in pragmatic answers (for a review see, for example, Koch 2006a, 2006b).

The technical literature in this area typically takes an "activity-based approach" (Marston, Golledge, and Costanzo 1997). Grounded in the regular space of classical transportation modeling in which space is constant and regular, Kwan, among others, has experimented with network-based approaches that develop space-time accessibility measures, a point-based approach in which travel networks are divided into origins and destinations, points on a map or graph, between which distance is calculated in one or another metric (time travel, cost of travel, etc.) (Kwan 1988).

Two problems were immediately apparent. First, the assumption has been that while travel across existing urban networks may be more expensive or more time consuming for some the system is accessible to all. Whether that is true is unclear, however. One may as easily argue that physical limits create absolute barriers, spaces that cannot be traveled. Methodologically, an activities-based approach — trips to the doctors, to shop, to the record store — is necessarily individualistic and therefore eccentric. While useful as a starting point, the goal must be a broader analytic whose subject is general and not specific. How might that broader analytic be expressed? Thus, the study of an individual case or cases should serve not as a description of "transportation disability" but as a springboard to a general problem of "transportation space" as eccentric and fluid. How might that transposition from individual to general be achieved?

Urban Barriers

One stream of work seeks to identify barriers to access in the local environment, those elements — high curbs, busy traffic intersections, steep slopes — that impede access for those with mobility limits. An example of this focused, large-scale approach is a study by Kitchen in association with members of an Irish "pan-disability organization" (Kitchen 2002). Working with the Newbridge (Ireland) Access Group, Kitchen developed a map of largely preventable environmental barriers — gradients, ground surfaces, high curbs etc — that impeded travel on individual streets and the buildings in them. The collaborative project involved contributors with various physical distinctions who together categorized the urban barriers that were mapped within a small, eight-block area. The focus of their investigation was not access to the area but accessibility of buildings and sidewalks within it.

The goal of the work, and similar projects elsewhere, was to identify those local, micro-geographic barriers that made otherwise accessible places inconvenient or inaccessible. "Overcoming space requires expenditure of resources, energy, and time, a charge that nature (including humans) attempts to minimize subject to constraints and other objectives" (Miller 2007, 203). Even if access is theoretically possible — if getting there is too time consuming, too expensive, or too arduous — those places are, effectively, "off the map." This work is typically restricted to a fine scale of concern, a few city streets and their buildings. Its relation to the city-at-large might be supposed but was unconsidered.

A research program emerged that would use mapping technologies as one of its tools. First, it would be useful to carefully record my daily travel patterns, the "daily activities" and the times and methods of travel to work, stores, leisure destinations. Secondly, these origin-destination records could be compared both to my own, pre-surgical patterns of activity and to the travel times, as a measure of accessibility, of the average, motorized Vancouverite. This data would hopefully would lead to a more rigorous, general analysis of "transit disability" and what it means, a new way to make concrete the broad problem of accessibility and distance barriers.

Daily Activities Listing

Between 2002 and 2005 a series of recurring destinations were recorded in my daily travel journals. These included travel time from home to the Dept. of Geography, University of British Columbia, where I served as an adjunct professor of medical geography, and to Simon Fraser University's downtown campus where I was an adjunct professor of gerontology. There were as well trips to the food markets on Fourth Avenue (I lived on Thirteenth), Granville Island, and Commercial Drive. At another scale entirely daily activities included trips to a local coffee shop, neighborhood supermarkets, and other non-work locations frequently visited prior to my osteoarthritis.

As a non-driver, these trips were largely undertaken on the public transit system except for a period of seven months in which post-surgical limits made bus travel on crutches impossible. During that time I was unable to get on local buses whose entry steps were too high for me to use. In Greater Vancouver the Coast Mountain Bus Company operates an integrated system of bus and electric trolley services under the provincially funded Translink agency serving the 21-municipality region that is Vancouver and its suburbs. Across the region the bus system is linked to an expanding light rail transit system with stations in downtown Vancouver and on Vancouver's Commercial Drive.

On the general bus route two or three different styles of bus are in use, some with steep steps, some that kneel, making access easier, and others with full wheelchair capability. A subset of bus routes at the time of this work was wheelchair accessible. Since the study began in 2002 the number of kneeling and wheelchair accessible buses has increased on an annual basis and the number of wheelchair accessible routes has slowly expanded.

The first map, therefore, would have to be blank, a map of the city I could not access except by taxi because I was unable to use public transit and cannot drive. Once I could both walk four blocks to the nearest bus stop and board the bus on crutches, the travel journal that would provide the data for my maps could be constructed. For each trip made I noted (a) walking time to a bus stop (b) time waiting for a bus (c) time traveling on a bus and (d) time from the destination stop to the destination itself. While on crutches, and then on a cane, my walking was approximately a third slower than that of the average walker. Informants walking the same route at the same time of day required an average of 6.5 minutes to walk from Arbutus and 13th to Arbutus and 9th (Broadway), I required 9.5 minutes to traverse that same distance. Later testing with others — including a person with familial dystonia — found the one-third time differential a fairly constant difference although several seniors on four-pronged walkers I timed took even longer.

For comparison, I used bicycle travel time based on my own, prior travel journals and those of an assistant as well as travel time by automobile recorded by an assistant. The automobile is the assumed mode of travel in Vancouver although efforts are made to wean drivers from their cars to public transit. The bicycle was included as a potentially important indicator of the argument some might make that poverty is itself a disability as real as any physical limit. For those without the $2.25 (Canadian) one-way fare price, and without a car, the bicycle provides an alternative form of transportation. While extremely coarse, it serves as a first measure of the mundanely-abled for whom automobile use and transit use were unavailable.

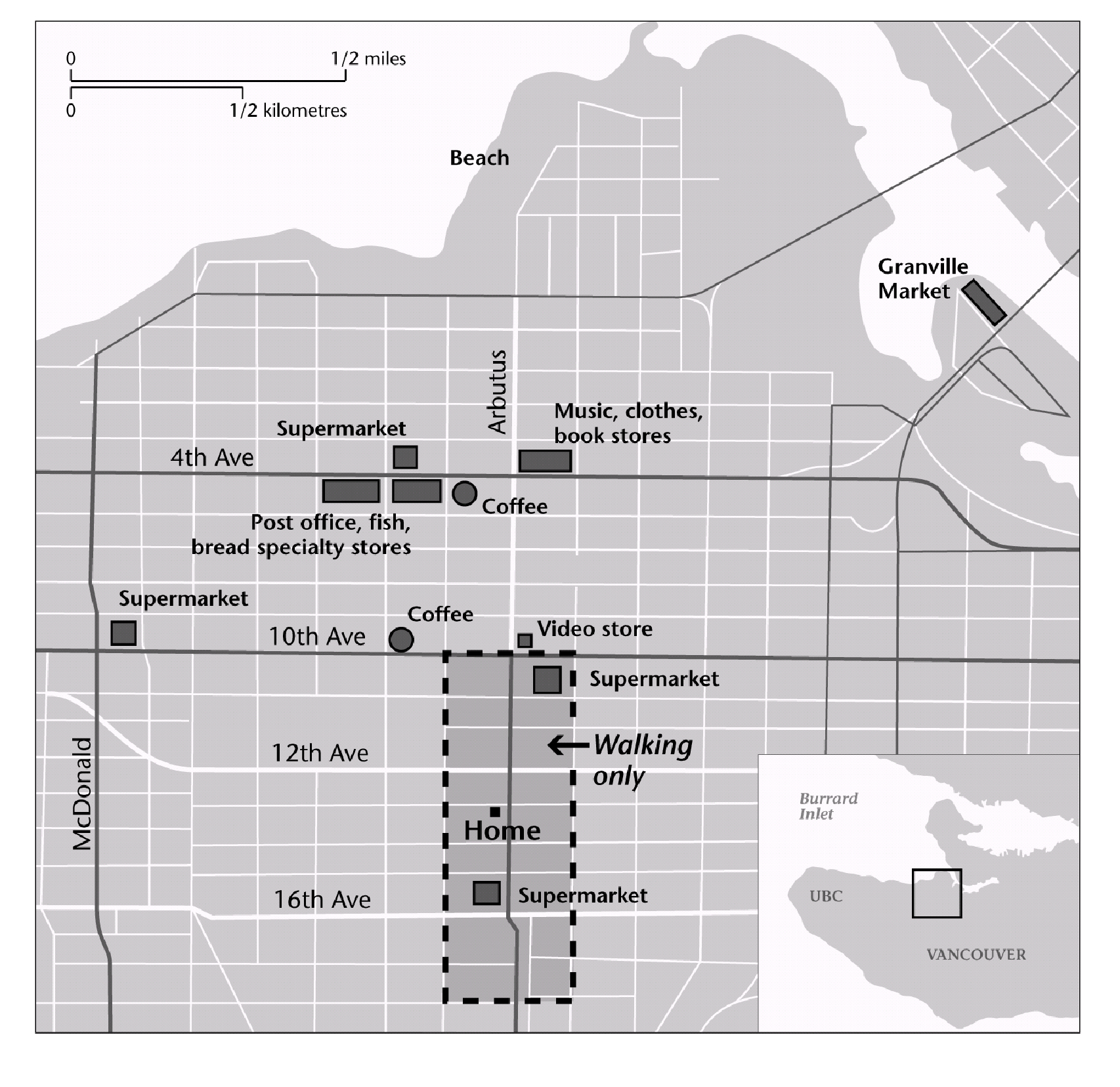

Differences were quickly evident at two very different scales of concern. These included variable access ranges at both the level of the metropolis and the level of the immediate neighborhood. The first involved non-neighborhood trips to work and other more distant locations. The second occurred at the very fine scale of the neighborhood. At this scale the result was a series of substitutions in which formerly frequented locations were abandoned for other, closer stores within a maximum four-block radius.

The Metropolitan Scale

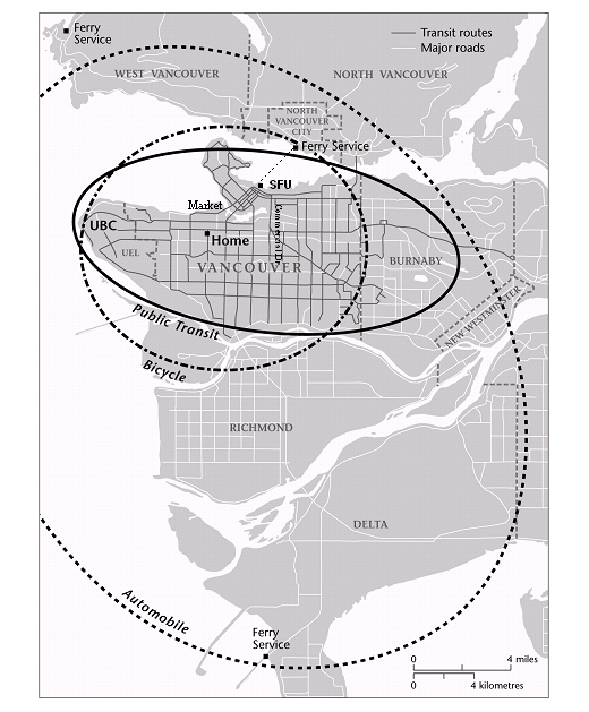

Within an hour driving time of my home accessibility reached from the southern ferry terminal in Tsawassen, British Columbia's Gulf Islands, to the northern terminal at Horseshoe Bay that serves Bowen Island in How Sound, the Sunshine Coast, and Nanaimo on central Vancouver Island. Bus and bicycle ranges were more restricted, permitting access only to the central city. The oval shape of the transit systems general reach reflects the light rapid system that stretches from east Vancouver, a 32-38 minute bus trip from my house, to eastern suburbs. The more regular range of the bicycle commuting circle is based on my own cycling records, those of bicycle commuting friends, and a general assumption of an average speed of twenty to twenty five kilometers an hour in non-rush hour traffic.

The conclusion is presented in Figure 1, a map of coarse ranges, based on an hour's travel time, for the three transportation modalities. Clearly, these reflect different access potentials. Destinations include, to the west, the University of British Columbia, and to the east, Commercial Drive shopping area from which the light rail transit system can be accessed. To the north of the central city are Simon Fraser University's Downtown Campus and the maritime Seabus terminal permitting access to North Vancouver. Included as gray lines are the major bus routes that traverse the city it symbolized with gray lines. Major roads not covered by the system are symbolized with white lines.

Figure 1. A map of coarse ranges, based on an hour's travel time, for the three transportation modalities.

The map serves as an imprecise if useful descriptor of the variable effect of transportation modalities across the urban system. It does not propose different spaces but rater suggests relative ranges based on transportation modes within a single constant space. As Kwan has claimed, "Individual accessibility is determined not by how many opportunities are located close to the reference location, but how many opportunities are within reach given the particularities of an individual's life situation and adaptive capacity" (1999, 212). Clearly, transit modality defines accessibility, providing predictably greater access within a finite time frame to a larger range of places than the bicycle or the public transit route. Thus, while reflecting my own eccentric travel the general differences in range at least theoretically serve to identify general differences from any point in the system for the varying travel modalities, the specific range shifting east or west, north or south, depending on the originating location.

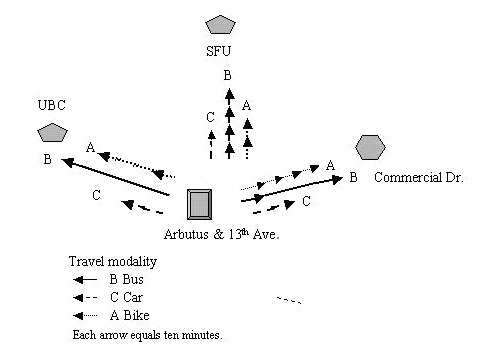

The simple transit modality range map does not express differences in travel time between locations embedded in the map, however. Implicit in the range map is one of travel time as a constant, albeit occurring at different but still constant rates (30 km. an hour for cars, perhaps 20 km. an hour for buses, and less for the bicycle). The daily activities log showed distance when measured by time to be a non-linear, complex space, however. Figure 2 is a table that catalogues the differences in travel time between representative locations in these ranges by modality. Reported times reflect the average duration of multiple trips from my home at Arbutus and Thirteenth Avenues based on my own and my informants' travel. Interestingly, within the immediate neighborhood represented by the Granville Island Market and those on Fourth Avenue the difference between car and bike was relatively minor. Between car and bus, however, the difference at the local scale was significant.

| TO | Car | Bus | Bike |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBC office | 14 min. | 55 min. | 38 min. |

| SFU (or ferry) | 12 min. | 40 min. | 20 min. |

| Commercial Dr. | 16 min. | 35 min. | 40 min. |

| Market (Granville) | 10 min. | 35 min. | 14 min. |

| Markets (Fourth Ave.) | 6 min. | 28 min. | 8 min. |

In effect, the inability to drive meant that what for others would be brief excursions — for example to Fourth Avenue markets — became, for me, significant trips requiring significant expenditures of time. Further, these locations assumed an ability to walk at least four blocks with minimal discomfort. While on crutches, however, and on the first months with a cane, this assumption was unrealized. The approximately six-block distance from the nearest bus stop to the Granville Island market was too great to be attempted safely. It was added to the list only after post-operative recovery was well advanced.

The difference in travel modalities are expressed graphically in Figure 3 through a simple scaling technique that gives some idea of the effect of travel modality on trip times. Each single arrow is ten minutes travel and multiple arrows are additives of ten minutes, or a fraction of it. Everything is close when travel is by automobile, further when travel is by bus. The bicycle is a surprisingly effective substitute for the automobile for short-range trips, albeit one that was unavailable to me.

Figure 3. Scaling of travel time by bus (B), bar (C) and bicycle (A) from 13th and Arbutus to three different city locations.

Effectively, travel time constraints permitted, at most, one interurban trip by normal transit — for example to UBC or to SFU or to Commercial Drive. That time, with chores as the destination, effectively made a trip that might be for a car driver a brief expedition an expedition that was, for me, at least a half-day round-trip. While travel across the system was possible in theory, travel time became a prohibitive in trips outside of the core city, for example to the Tsawassen (southern terminal, figure 1) or Horseshoe Bay (northwestern figure 1) ferry terminals.

More importantly, the result presented a time-space that was not smooth and constant but wrinkled and irregular. The local coffee shop I had patronized, one a few minutes from my house, became a more distant destination, for example. At issue was not raw accessibility — I could get there by a bus using two transfers —but the distance in time was far more complex, and variable (less constant), than a Euclidian space measured in kilometers would have predicted.

Neighborhood Scale

The effect on daily living patterns was especially notable in the neighborhood I had, prior to surgery, unthinkingly inhabited. During much of the study period my walking time was a third that of average citizens and limited to a range of four to a maximum of five city blocks. Any distance farther than four blocks required a several-minute rest period to permit the pain to decrease. Within Greater Vancouver that made some destinations, while theoretically accessible, practically unavailable. Included in the list of inaccessible sites would be those homes or shops on slopes greater than perhaps 8 degrees. While relatively few, they were still noticeable — for example the home of a friend at Third and Yew a block north of the Fourth Avenue coffee shop. Included as well were a large part of Pacific Spirit Park and homes on Eighth to Six Streets between Granville and Cambie, principal homes and commercial areas of the city.

Figure 4. Preoperative travel range included shops on Fourth Avenue and the Granville Market. Post-operative travel was largely limited to a four-block area centered on the home, a mobility range of approximately four blocks in 9.3 minutes.

More importantly, perhaps, because of limits in walking distance or cycling, neighborhood shopping that had required little time now required a 28-32 minute bus trip. Because no bus runs along Arbutus to Fourth Avenue, for example, it was necessary to travel west to Broadway and Alma to transfer to an eastbound bus or to Granville and Fifth for a westbound bus. Thus to travel to the stores previously patronized required two buses, with their attendant waiting times, and one transfer.

As a result, my daily purchase patterns shifted from Fourth Avenue to Broadway Avenue stores near Arbutus, from small specialty stores to a single supermarket for food. Travel to Commercial Drive, Granville Market, and the North Shore became full day trips rather than afternoon excursions. In effect, my travel range for daily necessities was altered, restricted by the time a bus-transfer trip would require for food, shopping, afternoon coffee, etc. At night, when transit is less frequent, the situation worsened. The shifting range of transport disability is graphically described in Figure 4 where shops on Fourth Avenue and the Granville Market are shown outside a darker, home-centered rectangle that was the post-operative travel range.

Discussion

All of this may seem obvious, confirming what is known, and certainly commonsensical. Inability to drive is in this study certainly a disadvantage — it takes longer to get there from here — exacerbated by ambulatory limits. Travel took longer and not all equidistant points were equally accessible: some places came off my daily map because of distance from a transit stop, or became excursions rather than simple trips. For those who are wheelchair users in my neighborhood, the lack of accessible stops would be, at least for those who do not drive, not disadvantageous but disastrous.

There is no wheelchair access to the transit system within 1.5 kilometers of the Arbutus and Thirteenth Avenue epicenter of this study. In a wheelchair, or again with limited mobility on crutches, one is literally off the map. Equally disadvantaged are those whose poverty inhibits both transit use and automobile ownership although for some the bicycle may serve as a local-and mid-distance substitute. Whether the result is "disabling" depends as much on one's understanding of the adjective "disability" as it does on the limits of either the transit system or the potential transit rider him or her self.

In a similar vein, this experience affirmed the observation by Golledge (1993) quoted earlier, and more recently rephrased by others, that differing abilities require people to move differently through the environment which is transformed by individual capabilities (Church and Marston 2003, 9096). Automobile drivers, irrespective of other impairments, access the city in a way that I — and others without cars — could not. Persons with mobility limits who have a limited range have different access levels than those whose ambulation is more or less mundane.

Not obvious either in the maps or the literature is what all this means. If "transit disability" is embedded in the system then how can it be defined and expressed across the system? The experiences detailed in this paper, and by others with mobility limits, suggests a difference space in which the regular metrics of time-distance transit planning are modified or suspended in the reality of daily use. In the design of urban systems we assume distance is a constant that expands in a regular and consistent, linear fashion. If it is five minutes to "x" location at this speed; a distance twice as far requires twice as much time. And while that may be generally true for some, the reality experienced here was different. Space is in effect wrinkled, an irregular surface in which hills of time create barriers for some that for others are simple planes of distance. In addition, mobility limits may impose absolute barriers for some — for example a 6-block walk for me — that for others are not impediments at all.

Like all very personal studies the results are limited to the nature of the individual experience. Even if one accepts the commonality of my experience, what is the reality of those who require wheelchair access to the transit system? Not all paraplegics can drive. Nor can all those who require scooters and other motorized ambulatory aides. Within Greater Vancouver transit access for those who use wheelchairs is restricted not only by temporal wrinkling but by the system itself. They are limited absolutely to a small number of routes that permit access at specific times of the day. The question of wheelchair users is not simply one of a distinct range but of accessibility itself.

Clearly, simple mapping of eccentric daily activity routes do not serve to express the general reality experienced here. More fundamentally, the traditional assumptions of transportation and urban analysis reflected in this paper's map, assumptions of distance measured in time as a regular constant, require a different analytic. How does one argue a "wrinkled" space that is generally non-constant and in parts practically inaccessible even if system maps make the systems that traverse them appear accessible to all?

Future Works

First, there would need to be a map depicting the lines and stops of the system. Those would become the raw data from which travel time surfaces based on different travel modalities would be developed. Centered on a single location, what was required was a surfacing of the space-time of the city for different travel modalities if a very plastic and variable travel space based on modality were to be created.

In future studies automobile use would be the necessary travel mode against which other travel spaces were measured. This would require either a number of drivers logging travel points from the central location to all other locations, or a travel-time algorithm that would generate those points. In comparison, a time accessibility analysis based on transit system lines would need to be generated in a manner that reflected real travel time, including time walking from the origin point to transit access nodes, time waiting at access nodes and transfer points, and time walking to destinations. Finally, a parallel study based on transit accessibility and time for wheelchair accessible transit routes would need to be created for the region.

Surface analysis uses data points to generate a continuous space in which a single variable — travel time, cost, etc. — can be created across an area in which origin and destination points can be identified. This inverts traditional transit mapping in which such points are the focus within a space that is assumed to be constant and linear. Developing the data to map a complex surface on the basis of cost, time, or some other variable is not a trivial problem. It requires first a well-developed dataset and secondly a method of testing the accuracy of the resulting surface. As a first step, I applied for and received from Coast Mountain Bus Company (CMBC) map files that described all routes within the Greater Vancouver Regional District and all bus, trolley, and light rapid transit system within the region. CMBC officials also provided the location of individual transit stops on each route. Online schedules for the period of December 2006 to April 2007 permitted travel time and transfer time to be added to all routes.

To analyze this data, and develop an approach that would serve for the various modalities, I applied for assistance to several colleagues. They include, to date: adjunct professor of geography Ray Torchinsky, Simon Fraser University (Vancouver, BC); University of British Columbia transport and urban geographer Ken Denike, and Simon Fraser University transportation and urban geographer Warren Gill. Together we created the Vancouver Transit Access Study Consortium, to develop a system of accurately assessing the relative accessibility of the city by varying modalities for persons with different physical limits.

Aware that all travel is dependent on traffic levels, we decided to begin by limiting our work to non-peak travel hours during the weekday. To date a tentative system of mapping has been developed that permits surface maps analyzing travel time for automobile, transit, and wheelchair transit use. A second task, not yet complete, is to add to these transit maps multi-modal capabilities, including for example the time it takes to walk or wheel to and from a transit stop. Also to be added will be surface contours permitting streets with specific gradients to be taken off the map of mobility limited users

Generation of the maps is only part of the exercise. The maps are the workbenches on which we hope to generate more precise mathematic descriptors of relative accessibility of these interrelated but distinct travel systems. We believe the methodologies evolving from this work will permit an accurate portrait of mobility constrained, locational accessibility measures for critical urban locations — city hall, hospitals, shopping malls, universities, etc. — as well as a general portrait of modal inaccessibility. In other words, we will be able not only to map generalities but specifics, to ask whether Vancouver City Hall is accessible to all or is its accessibility limited, and if so to what degree, to certain classes of citizens who can drive, afford a bus, or find wheelchair routes from home to the City Hall. This degree of specificity will require an analytic sufficiently flexible to focus on a wide variety of central points and to refashion the mapped perspective from a range of origins and destinations.

The research is academic to the extent that it seeks to find a consistent methodology encouraging the investigation of urban accessibility both in terms of characteristics of different modes of travel and of constraints on the mobility of individuals. It is academic in its critique of an existing assumption of space. The goal, however, is practical, activist, and local. The hope is to develop a methodology by which debates over urban accessibility can be pursued in a climate not simply of political dissent (See, for example, Imrie and Edwards 2007; Valentine 2003; Gleeson 2000) but instead grounded in clear expressions of concrete differences. The hope is that development of this approach will serve both local communities of difference and transit officials who are making a strong, good faith effort to expand their service to assure the greatest possible ridership.

At this writing the first surface models of the variable systems are being generated. Attempts to expand them to include more variables — including the effect of slope on walking, of absolute walking limits, speed variation and non-linearity of walking times, etc. — are soon to be begun. So, too, we hope to develop general algorithms that may modify those currently employed on the assumption of special regularity. That, however, is for the future.

The program has to date received no outside funding. Nor has any been applied for. We believed it important to first investigate the potential of our approach before seeking support for further research. This report therefore presents a first statement of the pre-test and early modeling rather than of the results of our efforts. We hope within six months to a year to be able to begin a series of more detailed reports expanding the eccentric and personal critique presented here into a more general, system-wide exploration whose methodology encompasses the traditional planner's focus on locations of origin and destination in a general surface analytic we believe will best serve to express the effect of physical limits on urban access using different transportation modalities. We believe with that the need to equal the playing field to assure equal access to all will be not simply a political ideal but a social goal in transit planning.

Author's note:

The author expresses his gratitude to Raymond Torchinsky and other members of the Vancouver Transit Access Consortium for their contributions to this project and the article describing its genesis. He also acknowledges the comments and suggestions of both peer reviews and journal editors that have assisted in the transformation of an earlier draft into this paper.

Bibliography

- Britton, E. 2002. Toward a new world of fair nobility: Or … Is it true you can't get there, until you have been there? World Transit Policy and Practice 8:2, 5-8.

- Church, R. L. and J. R. Marston. 2003. Measuring accessibility for people with a disability. Geographical Analysis 35:1, 83-96.

- Golledge, R. G. 1993. Geography and the disabled — a survey with specific reference to vision impaired and blind populations. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 18, 63-85.

- Golledge, R. .G. 1994. Disability, barriers, and discrimination. Paper presented at the New Distributional Ethics: Differentiation and Discrimination Conference, Boston, MA. November 7-9.

- Gleeson, B. 2000. Enabling geography: Exploring a new political-ethical ideal. Ethics, Place and Environment 3:1, 65-69.

- Gleeson, B. 1997. Community care and disability: The limits of justice. Progress in Human Geography 21:2, 199-224.

- Imrie, R. And C. Edwards. 2007. The Geographies of disability: Reflections on the development of a sub-discipline. Geography Compass 1: 1-11.

- Kitchen, R. 2002. Participatory mapping of disabled access. Cartographic Perspectives 42, 50-60.

- Koch, T. 2006a. Bioethics as ideology: Conditional and unconditional values. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 51:251-267.

- Koch, T. 2006b. Bioethics as ideology: Conditional and unconditional values Journal of Medicine & Philosophy 31:3, 351-268.

- Koch, T. 2001. Equality and disability symposium: Disability and difference: balancing social and physical constructions, Journal of Medical Ethics 27:5, 370-76.

- Koch, T. 1990. Mirrored lives: Aging children and elderly parents. Westport, CT: Praeger Books.

- Kwan, M. 1999. Gender and individual access to urban opportunities: A study using space-time measures. Professional Geographer 51:2, 210-227.

- Kwan M. 1998. Space-time and integral measures of individual accessibility: A Comparative analysis using a point-based framework. Geographical Analysis 30:3: 191-217.

- Marston, J. R. Golledge, R. G. and C. M. Costanzo. 1997. Investigating travel behavior of non-driving blind and vision impaired people: The role of public transit. Professional Geographer 29:2, 235-245.

- Miller, H. 2007. Place-based versus people-based geographic information science. Geographic Compass 1: 3, 503-535.

- Porter, A. Compromise and constraint: Examining the nature of transport disability in the context of local travel. World Transport Policy and Practice 2, 9-16.

- Shakespeare, T. 2007. Disability rights and wrongs. NY: Routledge.

- Taffe, E. J. and H. L. Gauthier, Jr. Geography of transportation. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Tremain, S. 2005. Foucault, govermentality, and critical disability theory. In, Tremain, S. Editor. Foucault and the government of disability. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Valentine, G. 2003. Geography and ethics: In pursuit of social justice — ethics and emotions in geographies of health and disability. Progress in Human Geography 28:3, 420-432.