Using data from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, this paper explores disabled transgender sex working college students' experiences within sex work economies and within other paid labor force economies, experiences while in/at college, and self-reported health outcomes. Findings indicate that disabled transgender college students experience far-reaching discrimination, harassment, violence, and economic precarity while in school. At least 11% have engaged in sex work economies, and this may partly be explained by their violent labor force and educational experiences. The discussion highlights specific implications for and suggestions about how to improve college campus and off-campus collaborative Identity-Based services (e.g., LGBTQ Centers, Race/Ethnicity-Based Centers, Religious Centers, Student Disability Services, Financial Aid, etc.), Health-Based services (e.g., Student Health, Counseling Services, Wellness Center, etc.), and Administrative and Policy-Based services (e.g., Dean of Students, Student Conduct, Career Service, etc.). We conclude that our work sheds light on how all students, but particularly disabled trans sex working students, would benefit from being better economically resourced, with stronger administrative support via cross-collaborative partnerships and programming, and informed and competent service providers, who work together—and not in isolation—to provide education to the broader campus community and outreach directly for sex positive student sexual health.

Introduction

The concept of sex work is a dynamic one, especially in a time where the digital consumption and production of sex is ever evolving. As an umbrella term, sex work encompasses numerous forms of erotic labor. The Internet has reshaped existing sex industries and led to the creation of new ones (Attwood 2010; Paasonen 2011; Jones 2015, 2020a). Today, we see a variety of digital sexual economies, including individuals producing commercial sexual content (clipstores, camming), engaging in commercial sexual relationships (such as sugarbabying or within the dynamics of professional Bondage & Discipline, Dominance & Submission, and Sadism & Masochism (BDSM)), and continuing in more traditional commercial sex industries (e.g., stripping). Despite the proliferation of cybermediated sex work and digital sexual fields, there remains a dynamic community of in-person sex workers, including strippers, lifestyle and pro-Dominants, and full-service providers, even during the past two years of the global Covid-19 pandemic (see a summary of research on in-person sex work since the onset of COVID-19 in Hamilton, Barakat, & Redmiles, 2022).

Despite a prominent and stigmatizing focus on the risks of sex work (deficits, disorders, and disease syndemics), numerous scholars have recently pointed to sex workers' desires to claim a singular, authentic selfhood (e.g., not keep their sex work a secret (Simpson & Smith, 2021)) and situate their sexual labor alongside, rather than outside, of more traditional forms of work (e.g. that sex work is not the only form of labor open to them (Glover, 2021)). This emerging scholarship calls into question the normative assumptions about and moral objection to sex, sexuality, and embodied and affective labor; and, with an emerging focus on pleasure, "has the potential to subvert hegemonic discourses about gender" that constrain all people's sexuality (Jones, 2016).

This paper is exploratory and seeks to expand what we descriptively know about the experiences of college-aged, disabled, transgender sex workers, specifically. As others have pointed out before us, and as we will explore in more detail below, a majority of the literature on sex work to date has focused narrowly on cisgender women, with more recent expansion by public health experts and criminologists on detailing the experiences of transgender women of color. While the women featured in this existing research may be disabled, we assume that most of the time, questions related to disability are either not asked by the researchers conducting the work (or, if it is, it is rarely reported in the findings). Centering our exploration on college students–or those recently enrolled but forced out–is intentional: the COVID-19 pandemic has re-invigorated discussions about college students' financial precarity, access to resources, and overall well-being. Although we use data from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, we hope that the findings will inform current conversations about how to best show up for, actively resource, and improve the long-term health outcomes of disabled transgender students.

Before detailing what we do know about disabled transgender college students' engagement in sex work, we want to take a moment to discuss some of our language and conceptual choices. These choices are informed largely by the first author's positionality–as a trans, neuroqueer, cripple punk–and training–as a quantitative social scientist. First, language. The language best used to describe disability is "currently the subject of intense and passionate debate" (Fletcher-Watson and Happé, 2019). While there is no single consensus as to whether identity-first language (IFL) ('a disabled person') or 'person-first language' (PFL) ('a person with disabilities') should be used, much of the available research, narratives, and conversations happening in disabled communities indicates that identity-first is not only preferred (Kenny et al., 2016; Sinclair, 2013) but also far less stigmatizing than person-first language (Andrews et al., 2019; Gernsbacher, 2017). While it is important not to prescribe one over another for universal use, we will henceforth use the language the first author also uses for themself: identity-first (disabled first).

Second, a word on the conceptual definitions of disability. We would like to note that the Healthy People 2020 questions—often touted as the gold standard for survey data collection on the incidence and prevalence of disability, and standardized and validated across diverse contexts and cultures—are limited, and rely on a medical model of disability. To be more specific, not all individuals who affirmatively answer yes to questions about "functional limitations" or "impairments in daily life activities," would self-identify as disabled if asked a specific question about identity. There are numerous reported reasons for this disjuncture, including sociocultural factors (Cameron, 2007; Miller, Wynn, & Webb, 2019), lack of knowledge about and/or connection to disability communities (Dunn & Burcaw, 2013; Gill, 1997), the internalization of social stigma or shame (Onken & Slaten, 2000; O'Toole, 2013), and/or the expectation of bias, violence, or retribution, such as job loss, upon disclosure (Gignac et al., 2021).

That said, the inclusion in this paper of folks who do not self-identify as disabled, but who do report the structural inaccessibility of everyday life, is intentional. The authors of this piece, who did not conceive of this survey, choose its disability-related questions, nor collect the data itself, want to affirm that disability is not a personal limitation nor a disease/burden to be "cured." Disability is constructed within and in response to the ableist and sanist 1 interpersonal, communal, and structural barriers found within everyday life and social institutions. At the same time–and much like our decision to use identity-first language, due to the first author's own personal experiences–we felt it essential to highlight the experiences of all folks who might encounter educational and occupational discrimination/bias, exclusion from social spaces due to inaccessibility, and requests for (and denials of) accommodations requests at work/in school, regardless of their self-identification. We acknowledge that this decision is not without its own set of consequences for how it informs future work and suggest that scholars look at disparities between these two groups, as their data allows.

Literature Review

Sex Work - A Brief Overview

For the purposes of this paper, sex work is presented as a broad and inclusive category of erotic labor. In order to challenge what the sociological literature describes as "anti-sex work bias," we call into question and challenge the assumption that individuals are not able to engage in consensual and pleasurable erotic labor (Jackson, 2016; Lerum & Brents, 2016, p. 19; O'Brien, 2015). Indeed, sex work is often conflated with sex trafficking, and gendered and racialized "victim" frames often describe all sex work as coercive, forceful, and violent labor (Jackson, 2016; O'Brien, 2015; Schwarz et al., 2017; Weitzer, 2010). By naming sexual labor as patriarchal violence against women, this framework overlooks important complexities and nuance, such as the numerous and diverse pathways into sex work economies. In many ways, this framework is, in itself, violent; denying agency to both those who engage in erotic labor consensually and those who do so under conditions of coercion (Dennis, 2008; Jackson, 2016; Levy & Jakobsson, 2013; Stabile, 2020; Worthen, 2011).

This victim-frame leads to harmful social stigma and detrimental policy outcomes, rather than empowering or supporting people's lived realities; and this is especially true for those who experience multiplicative minoritization at the nexus of ableism, cissexism, racism, and other forms of oppression (Bettio et al., 2017; Kulig & Butler, 2019). Policies constructed to mobilize the carceral and police state to protect "victims" often utilize dubious and sensational statistics and are perceived by many to primarily function as a vehicle of "punishment and control" for sex workers (Augustín, 2007; Brooks, 2020, p. 516; Hagen, 2018; Lerum & Brents, 2016; O'Brien, 2015; Weitzer, 2014). Policies aimed at stopping sex trafficking expand the ability of the state to criminally punish erotic labor of all kinds (Sagar et al., 2015a; Stabile, 2020).

It is also critical to highlight how the institutions of psychiatry and biomedicine have often acted as another extension of the carceral state, criminally punishing "non-normative" (so framed by those institutions) sexual desires, behaviors, and identities (Das, 2016; Kirkup, 2018; Smilges, 2022; Vogler, 2019). This includes a long, eugenicist history of the denial of disabled and neurodivergent people's sexual desires, sexual agency, and sexual citizenship, including the general assumption that disabled and neurodivergent people are non-sexual or undesiring of sexual relationships and experiences (Brown, 2017). This history also includes targeted efforts to "cure" gay and lesbian individuals of their sexual desires via conversion "therapy" techniques such as castration, bladder washing, and rectal massage. Even after those techniques were proven not to work, psychologists, psychiatrists, and other medical professionals continued the implementation of electroshock therapy and lobotomies, then more recently aversive techniques via behavioral therapy (Graham, 2018). Finally, we see continued and sustained efforts to legislate trans people out of existence by limiting their access to gender-affirming care, criminalizing the doctors who choose to continue offering that care, and, in some instances, aiming to incarcerate the parents of trans children who consent to their care (Witt & Medina-Martinez, 2022).

In this way, we know that to understand trans disabled sex workers' choices and lives fully, we must challenge the pleasure/danger dichotomy (Vance, 1984), or the assumption that full sexual pleasure is only possible in the complete absence of sexual danger. This binary understanding of sexuality obscures the possibilities of everyone's sexual agency and choice, and is largely unproductive, given that many people find pleasure in sex work and their "context-specific agency and survival," while locating danger specifically in the "looming forces of the security state, criminality, and structural inequalities" (Schwarz et al., 2017: 1).

Transgender Sex Workers

The literature on transgender individuals' engagements in sex work is heavily skewed towards examinations of transgender women's HIV and STI risk prevalence and incidence, substance use, and experiences of both intimate partner violence and violence from clients; this includes a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on this HIV syndemic (Baral et al., 2013; Becasen et al., 2018; Cotaina et al., 2022; Operario, Soma, & Underhill, 2008), as well as on health outcomes (such as depression and suicidality) and health behaviors/barriers to care among trans sex workers (Brookfield et al., 2020; Pellicane & Ciesla, 2022; Platt et al., 2018) The majority of this work comes out of public health and medical sciences, and disappointingly, but largely unsurprisingly, researchers in these fields often study cisgender men and transgender women as if they are the same target population: "male sex workers" (see Perez-Brumer et al., 2016; Jones, 2020b).

Ultimately, the foundation of research in this area is focused on "survival" and "street-based" sex work, often framing transgender women as "victims" to poverty, joblessness, and other discriminatory housing and employment policies, forced into erotic labor (Rev & Geist, 2017). The hyperfocus on trans women as survival sex workers contributes to the "walking while trans" (Mogul et al. 2011: 61) phenomenon, describing how "transgender women, particularly transgender women of color, are… frequently perceived to be sex workers by police," to the extent that "transgender women cannot walk down the street without being stopped, harassed, verbally, sexually and physically abused and arrested, regardless of what they are doing at the time" (61).

If we look at studies using U.S. based samples, there are only a few, recent deviations from this stigmatizing frame; but what does exist has offered that sex work provides the monetary ability to take better care of oneself (Orchard et al., 2020), the freedom to set one's own hours of labor and terms of labor production (Glover & Glover, 2019), produces affirming feelings vis-à-vis being desirable/desired (Capous-Desyllas & Loy, 2020), and is a space that allows for joy in fulfilling people's fantasies (Del Rio & Pezzutto, 2020). There is still almost no research on the experiences of trans men and non-binary/genderqueer/gender expansive sex workers (see Jones, 2022).

Disabled Sex Workers

In contrast to the literature on trans individuals' experiences with(in) sex work, where disabled individuals are included, they are most often represented as the consumers of erotic labor (Earp & Moen, 2016; Freckelton, 2013; Mannino et al., 2017; Thomsen, 2015; Wotton & Isbister, 2017). In particular, scholars often focus on the ethics of "sexual surrogacy," and sometimes, research concludes that there should be a legal exception for disabled people in the prohibition of buying erotic labor (Yau, 2013). Much like the literature on trans sex work focuses nearly exclusively on trans women (primarily trans women of color), the research on disabled consumers of sex work focuses almost entirely on cisgender disabled men (Jeffreys, 2008; Jones, 2013; Liddiard, 2014; Sanders, 2007).

There is, overall, a dearth of literature on disabled sex workers. Indeed, you are likely to find fewer than 15 articles on Google Scholar if you search (in quotations) "disabled sex worker" (we found 13 at the time of writing this piece), and fewer than 60 for "disabled sex workers" (54 at the time of writing), not all of which are empirical or include the voices of disabled sex workers themselves. This is likely due to the dominant presumption, made by scholars, clinicians, and not-disabled others who misunderstand and often misrepresent disabled sex and sexuality, that disabled people are asexual or non-sexual (Brown, 2017). Asexuality is a valid sexual identity, and yet sexuality studies scholars and broader U.S. culture still often assumes alosexuality, and a superiority of being sexual shapes conversations about sexual identities. This largely erases the legitimacy of asexuality, and it is not true that a majority of disabled people are asexual (Brown, 2017; Rembis, 2010). It is through this lack of acknowledgment of disabled desire, pleasure, and erotic labor, that the scholarship in this area has (whether intentional or not) positioned disabled people as incapable of sexual agency and sexual self-determination (Tepper, 2000).

What's more, in the few circumstances where disabled individuals are represented as workers, they are uncomplicatedly discussed within the victim-frame (Dick-Mosher, 2015; Kuosmanen & Starke, 2011). Disabled people are also included in ethical and theoretical debates about minoritized sex workers' rights (Laws & Drew, 2022; Russo, 2019; Sanders, 2007). Like the literature on trans women sex workers, disabled workers are often described in terms of their relation to drug use and HIV/STIs (see Blewett, 2019; Rugoho, 2019). Though still primarily oriented towards sexual surrogacy, Fritsch et al. (2016) consider the links between sex workers, disabled people, and disabled sex workers, finding them all seeking to "legitimize a range of forms of marginalized, stigmatized, and erased sexuality" (92).

College Student Sex Workers

Scholarship surrounding the engagement of college students in paid erotic labor is mostly concentrated outside of the United States (Betzer et al., 2015; Ernst et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2007; Sagar et al., 2015, 2016; Sanders & Hardy, 2015; Simpson & Smith, 2019, 2021; Wylęgły, 2019). A number of these pieces are written with the intent of considering the characteristics of students who engage in sex work, such as personality traits, substance use, financial circumstances, sexuality, and gender (binarily–and often sex assigned at birth–defined) (Betzer et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2007; Wylęgły, 2019). Some work on cisgender women college student populations considers their attitudes towards sex work, but without apparent attention to whether participants might be engaged as sex workers (Long et al., 2012). Other scholarship considers more closely the experiences and motivations of college students engaged in sex work, but does not attend to the needs or experiences of trans and/or disabled students (Haeger & Deil-Amen, 2010; Sagar et al., 2016; Simpson & Smith, 2019, 2021; Upadhyay, 2021).

We know from this existing literature that financial circumstances are essential to motivating students to engage in sex work, but it is not the only factor at play; students describe varying degrees of enjoyment, flexibility, and the benefits of alternative employment. For instance, cis women sex workers in college report that even if their role is temporary, it may become an important and positive part of their identity (Simpson & Smith, 2021). Moreover, camming, specifically, may be an important axis through which college sex workers fulfill desire and experience pleasure (Jones 2020a). It has also been theorized that cultures of consumption in college student populations have "mainstreamed" the idea of engaging in sex work (Sanders & Hardy, 2015). Lastly, college sex workers describe stigma as a primary cost of their role, rather than the risk of violence, as the victim-frame might suggest (Haeger & Deil-Amen, 2010).

Our Contribution

Methods

Building on this existing literature, our paper focuses primarily on describing the population of disabled transgender college students who engage in sex work economies. Utilizing the U.S. Transgender Discrimination Survey (USTS 2015; N = 27,715), we focus on a few key areas that have not been explored adequately in the literature, in the hopes that we might not only illuminate some of the pathways trans disabled college students take into sex work, but also highlight the need for comprehensive, holistic, competent, sex-positive and disability justice-oriented college student services. Our key areas of inquiry include detailing the 1) demographic characteristics of sex working disabled transgender students, 2) their experiences within other labor forces, 3) their experiences while in/at college, and 3) some of their self-reported health-related outcomes. You can find more detailed information on each of these areas, including sampling techniques, survey items that constitute our key variables of interest, and related documentation in our methodological addendum.

Participants

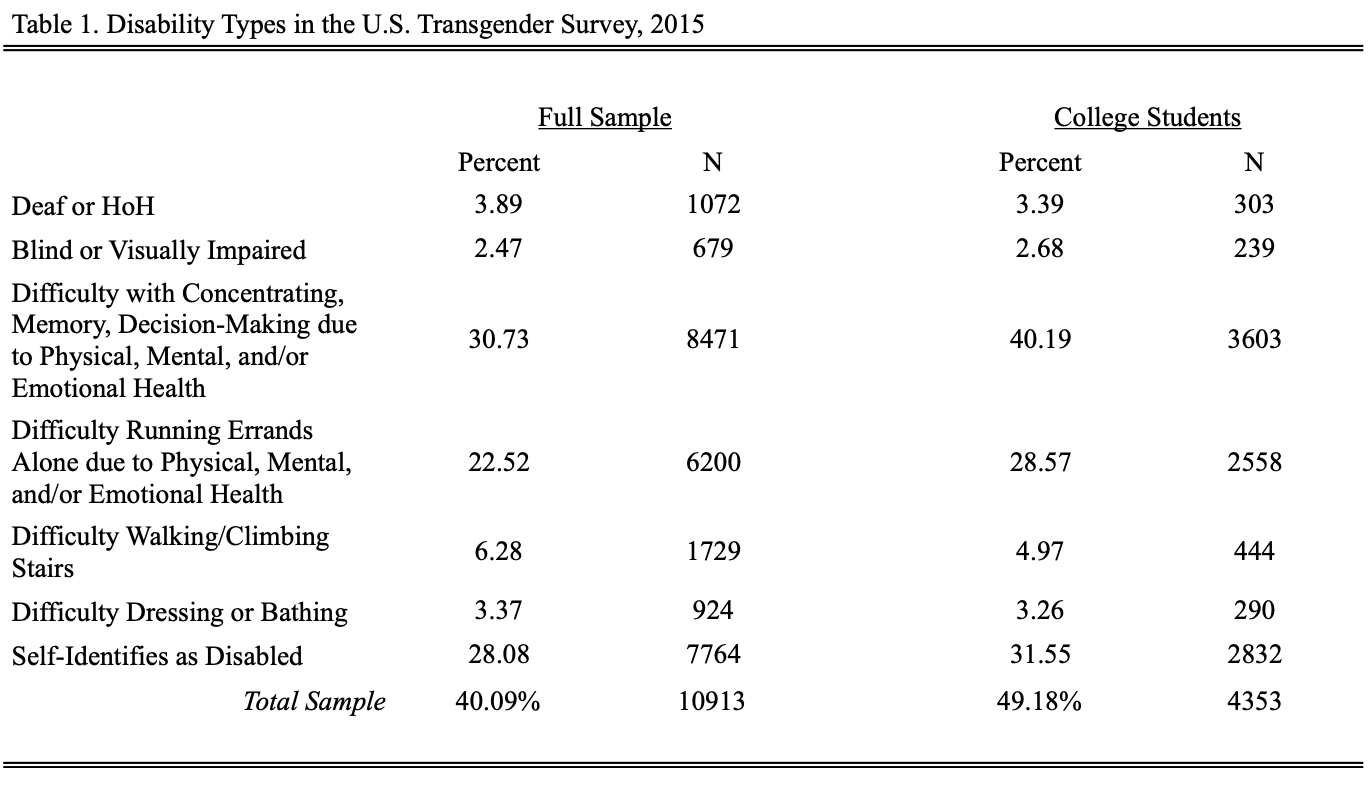

Disability is measured in various ways. There is an option to self-identify as "disabled," as well as answer affirmatively to one or more standardized questions validated by Healthy People 2020 that are meant to identify disabled adults. In the USTS sample, 40.09% (N = 10,913) of transgender adults are categorized as disabled, while around 28% of the sample self-identify as disabled. 2 As Table 1 (below) shows, more college students self-identify as disabled than the general sample (nearly 32%), with 10% more reporting difficulty concentrating, remembering things, and/or making decisions. In total, nearly half of the transgender college student sample meets the criteria for disability.

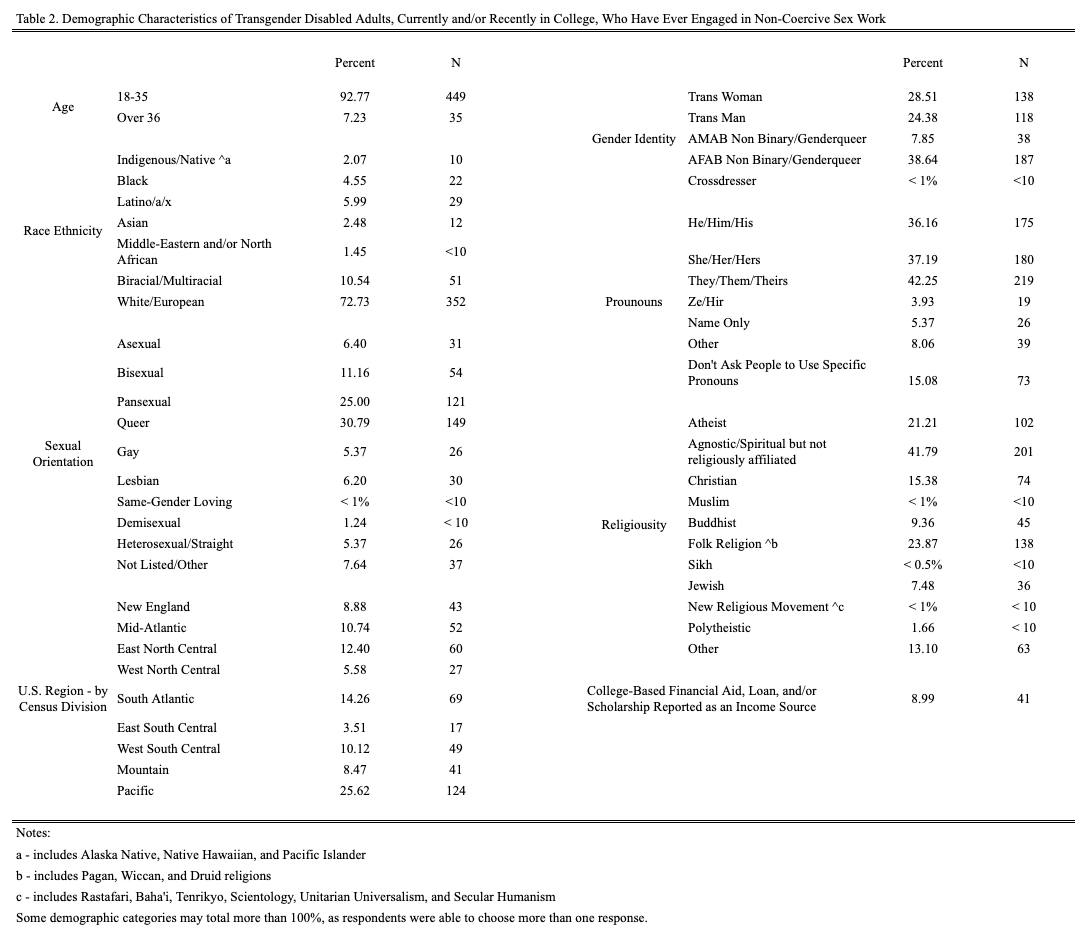

Despite the USTS's efforts to avoid internet survey sampling biases, (Table 2, below), the sample of disabled college students is predominately white (73%), with the largest geographic representation coming from the Pacific (26%) Census division (California, Oregon, and Washington). Additionally, participants are largely non-binary and assigned female at birth (40%), queer (31%) or pansexual (25%), under 35 years old (95%), and variably religious.

Measures

Experiences within sex work economies. Multiple questions assessed whether or not a participant had ever and/or in the past year "engaged in sex or sexual activity for money (sex work) or worked in the sex industry (such as erotic dancing, webcam work, or porn films)", and using specific follow-up questions on the type of sex work (e.g., pornography, webcam work, street-based sex work, including a qualitatively recoded variable that the participant was "forced to" and/or was "underage at the time") and the purpose of sex work (e.g., for fun, for income, or for survival (food, shelter, drugs)), we were able to construct variables that examined sex work both outside of and within "the home" and exclude participants who indicated they were forced or coerced into sex work.

Experiences within the labor force. Given that disabled students may find (certain forms of) sex work more accessible to their labor force participation, and given that we know both disabled people and LGBTQIA+ people experience workplace harassment and discrimination that impact their labor force participation, we also examined disabled trans college student sex worker's experiences within the labor force. A series of questions assessed whether or not a trans person had ever and/or in the past year been fired from, lost a job, was denied a promotion, or was not hired. Additionally, participants were asked if they had experienced verbal, physical, and/or sexual assault(s) at work in the past year, due to gender identity, and whether or not the person, to avoid further discrimination, had quit a job within the past year.

Experiences while in college. It is important for numerous student resource representatives and staff to know the breadth and depth of experiences that their college students face. We also wanted to examine some of their experiences while in/at college. Within this category, we looked at a handful of questions: "How many current classmates know you're trans", with responses of All, Most, Some, None; "On average, how supportive are your classmates with you being trans?", very supportive and/or supportive (0), neither supportive nor unsupportive (1), unsupportive and/or very unsupportive (2); "What are the main reasons that you don't live full-time in a gender that is different from the one assigned to you at birth?", the response I might face mistreatment at school; "Were you harassed (verbally, physically, or sexually) at college or vocational school because people thought or knew you were trans?", response yes/no; and three questions that assessed the location ("at my school") of the participants' reported verbal, physical, and/or sexual assault in bathrooms.

Health Outcomes. Lastly, and primarily as a way to describe some of the outcomes of the above experiences of school and job-based discrimination, harassment, and violence, we detail some of the various self-reported health indicators of disabled trans college students currently engaged in sex work economies: including self-rated overall health (fair or poor vs. excellent or very good), suicidal ideation (yes, no), suicide attempt (yes, no), and suicide attempts while in college (yes, no). Additionally, the Kessler-6 Psychological Distress Scale was included, which asks participants how often, in the past 30 days, they felt "so sad that nothing could cheer you up", "nervous," "restless or fidgety," "hopeless," "that everything was an effort," and "worthless." Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale from "All of the time (4)" to "None of the time (0)". Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with scores above 13 indicating serious psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2010).

A note about race and racism. As scholars, we affirm the need to account for structural/systemic racism and/or the outcomes of racialization in our analyses. In the tradition of QuantCrit, which integrates Critical Race Theory with quantitative methodology (Garcia et al., 2018; Gillborn et al., 2018), we believe that racism is firmly entrenched aspect of everyday social life and that statistical analyses have often been used to reinforce white supremacist hierarchies of oppression and violence. In the analyses that follow, we comparatively examine the reported experiences of white disabled trans students and Black, Indigenous, and other students of color (BIPOC students). However, because of sample sizes, we were unable to adequately account for the unique experiences of our students of color. We acknowledge that while some experiences under white supremacy will be similar, experiences of racism are not uniform across identities, cultures, and contexts.

It's also important to note that there were no reported differences, in any of our analyses below, that reached statistical significance thresholds. In mathematical terms, this means that any differences in raw percentages or means are theorized as attributable to sampling error; and that, if we sampled again and again, up to some nationally representative sample size, we would find all reported rates and percentages between white and BIPOC students to be the same. But, we want to be clear: this does not mean that there are not very real consequences to racism and white supremacy for these students, nor that we might also find the opposite of what is theorized to be true, should we sample more BIPOC trans people (e.g., that there are statistically significant differences between these groups, due to systemic racism).

These are noted limitations of this paper. As this dataset is secondary to us, we thus encourage researchers in the future to employ all of the recommended QuantCrit techniques, at every stage of the research process, from conception to design to data collection, and beyond (see Suzuki, Morris, & Johnson, 2021). This includes ensuring that samples are meaningfully diverse in lived experience, such that scholars might be able to assess the role of racism and racialization in reported outcomes adequately; and, that sample sizes are large enough to perform recommended mixture modeling, instead of relying, as we do here, on binary between-group differences.

Analysis

The analyses in this paper were conducted with Stata/MP 14 quantitative data analysis software for large datasets, and we primarily engaged with descriptive statistics and a series of chi-square analyses. Descriptive statistics include the reporting of percentages and means (such as rates of "yes" or "no" responses to particular questions). At the same time, chi-square tests determine if there are significant differences between one or more of the groups (disabled vs. not-disabled, sex worker vs. not a sex worker, etc.) in their reported college experiences, economic experiences, and sex work experiences. To assess which group is contributing most to any significant chi-square result, adjusted standardized Pearson residuals are computed. A standardized or Pearson residual is calculated by dividing the raw residual by the square root of the expected proportion, as an estimate of the raw residual's standard deviation. According to Agresti, "a[n adjusted] standardized residual having an absolute value that exceeds about 2 when there are few cells or about 3 when there are many cells indicates lack of fit of H0 in that cell" (1997: 38).

Experiences in Sex Work Economies

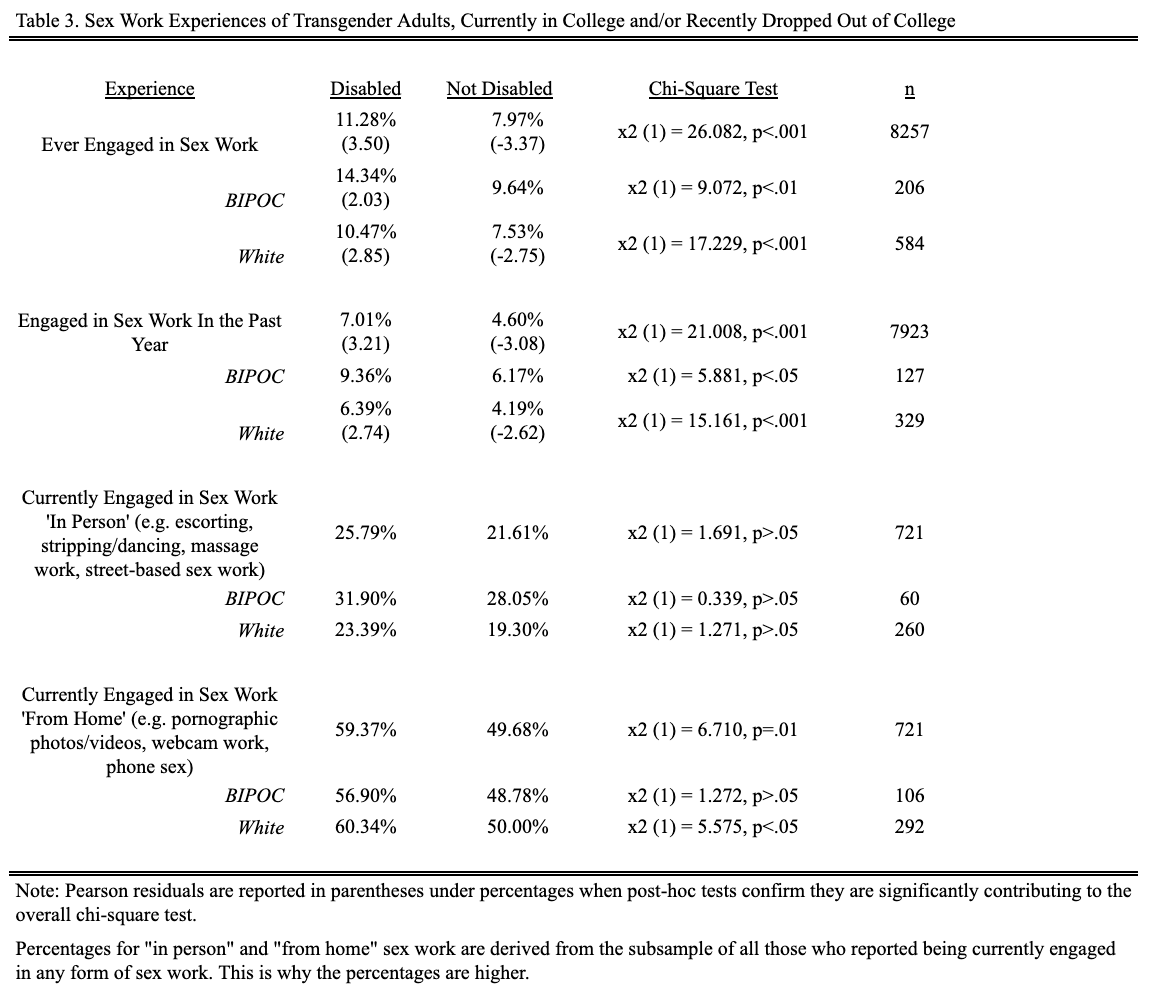

Table 3 (below) highlights that disabled trans college students are significantly more likely than their not-disabled peers to have ever engaged in sex work (11.28% vs. 7.97% respectively) and to have engaged in sex work in the past year (7.01% vs. 4.60% respectively). Of those who were sex workers in the past year, most worked "from home" (that is, engaged in video or photographic pornography, webcams, and/or phone sex), with significantly more disabled students reporting this type of work (59.37% vs. 49.68%). About one-quarter of all sex workers worked "in person" (e.g., street-based sex work, escort services, dancing, massage).

What's more, Black, Indigenous, and other students of color (BIPOC) are, on average, more likely than white students to have ever engaged in sex work and to have engaged in the last year. This is true for both disabled and not-disabled BIPOC trans students. Interestingly, while BIPOC trans disabled students are more likely than white trans disabled students to report being engaged in sex work "in person" (31.90% vs. 23.39%), the opposite is true for sex work from home: white trans disabled students are more likely to report being engaged in sex work from home than BIPOC trans disabled students (60.34% vs. 56.90%). Post-hoc chi-square tests show that all of these percentage differences are not statistically significant within this sample.

Experiences in Other Labor Force Economies.

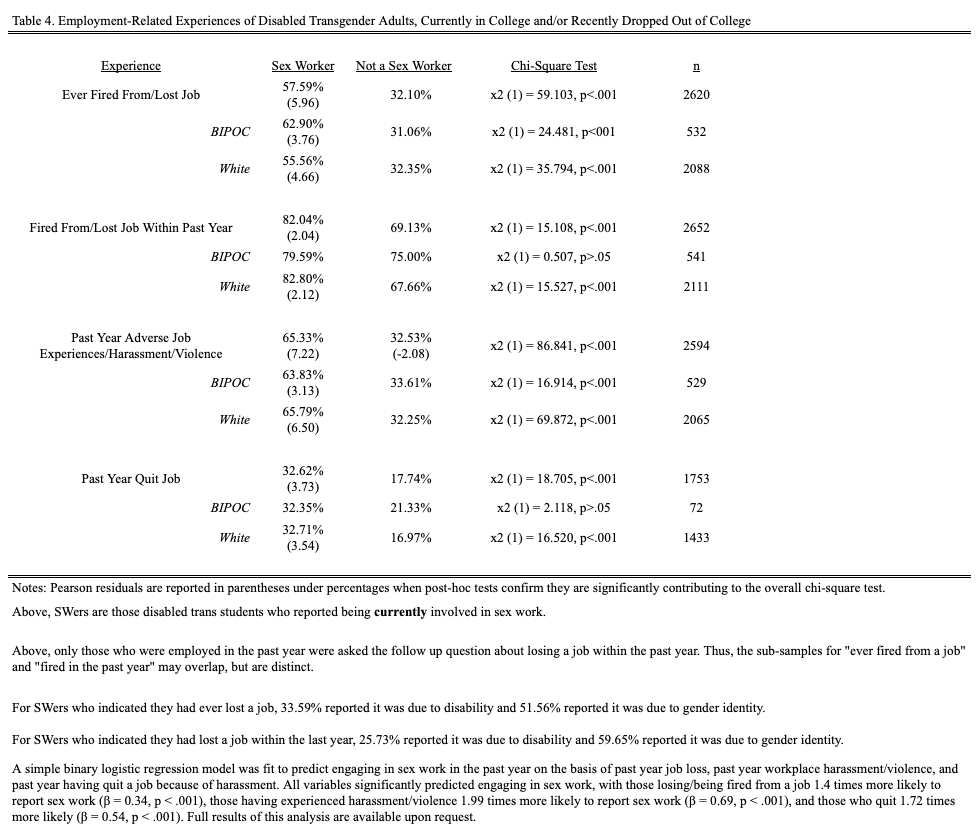

It is suspected that one potential reason for disabled trans students' higher engagement in sex work, particularly sex work from home and/or in which they have control over its production and distribution, is the multiplicative potential for discrimination, harassment, and bias in other labor force economies (on the basis of not only gender identity and younger age, but also disability status and race and ethnicity). Table 4 (below) suggests that this is a likely impetus for many of them. Disabled trans college students who engaged in sex work in the past year are significantly more likely than those not engaged in sex work to report lifetime job loss (57.59% vs. 32.10%), with over one-third reporting they believe they were fired, passed over for promotion, denied a job, or fired from a job because of their disability status and over half reporting they believe it was because of their gender identity. Unsurprisingly, we also find that those engaged in sex work in the past year, who were also engaged in other labor economies, are also significantly more likely to report past year job losses (82.04% vs. 69.13%), past year workplace harassment and/or violence (65.33% vs. 32.53%), and having quit a job in the past year because of discrimination, bias, harassment, and/or violence (32.62% vs. 17.74%).

BIPOC disabled trans students currently engaged in sex work are slightly more likely than white disabled students to report lifetime job losses, but nearly equivalently likely to report past year job loss, past year adverse job experiences, and past year quitting due to adverse experiences. However, again, post-hoc chi-square tests show that these differences are not statistically significant.

A simple binary logistic regression model was fit to investigate the above results further, predicting engaging in sex work in the past year based on past year job loss, past year workplace harassment/violence, and past year having quit a job because of harassment. All variables significantly predicted engaging in sex work in the past year, with those losing a job being 1.4 times more likely to report sex work (β = 0.34, p < .001), those having experienced harassment/violence being 1.99 times more likely to report sex work (β = 0.69, p < .001), and those who quit being 1.72 times more likely to report sex work (β = 0.54, p < .001). Full results of this analysis are available upon request.

Experiences of Bias While in College

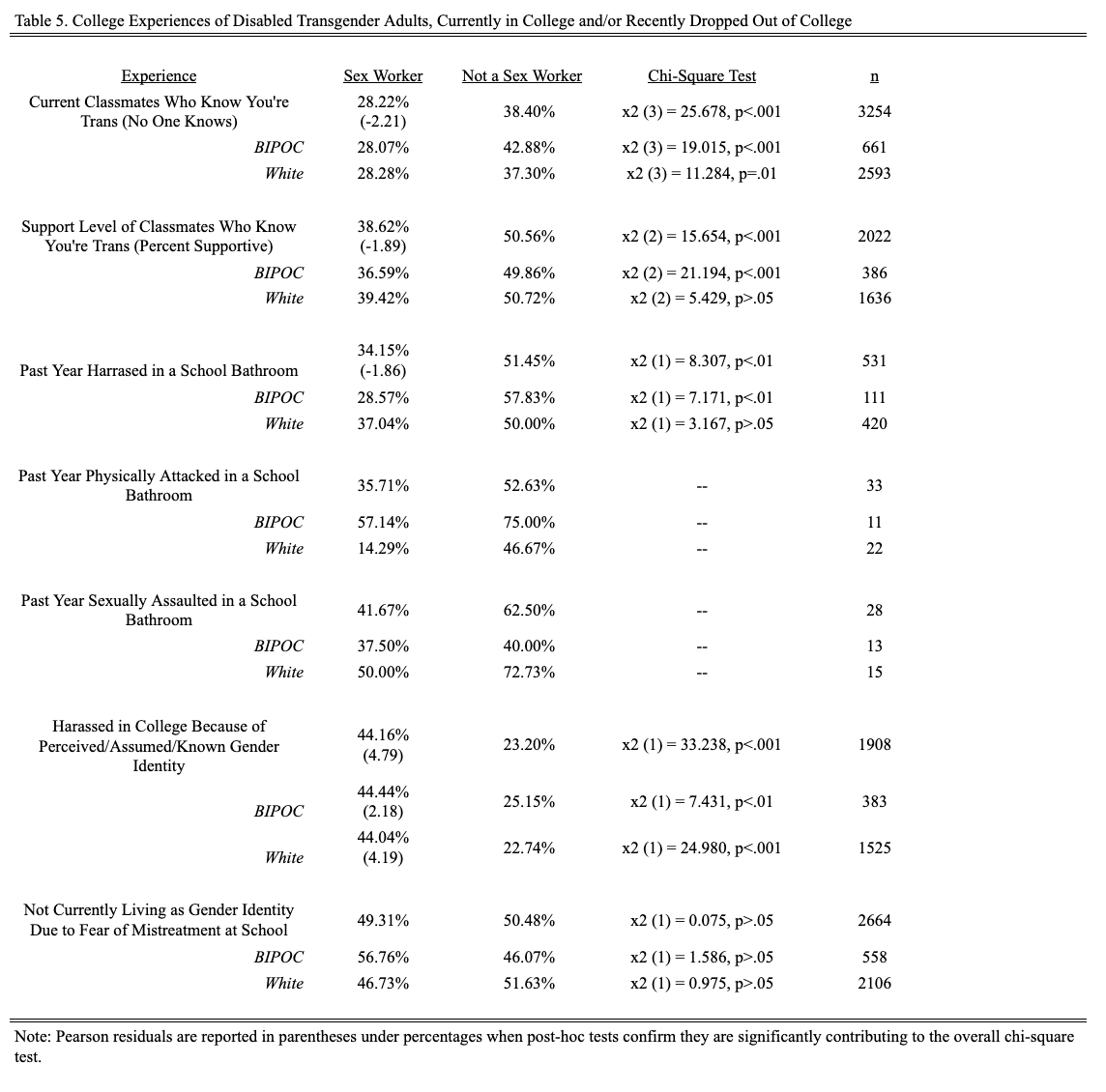

Table 5 (below) shows the complex experiences of disabled trans college students while they were/are in college. Interestingly, disabled trans students currently engaged in sex work are significantly more likely than those not engaged in sex work to report that all of their classmates know they're transgender. However, they're also significantly more likely to report that those classmates are unsupportive. These results remain consistent regardless of racial ethnic identity.

Some, if not most, of this fear may have to do with previous experiences of harassment and/or violence from peers and/or faculty/staff. For instance, between one-third to three-quarters of disabled trans students report being verbally, physically, and/or sexually assaulted in a college bathroom in the past year, and 44% of current sex workers, nearly twice as many as those not engaged in sex work, reported harassment (verbal, physical, and/or sexual) in college in other settings. Though the sample sizes were too small to run significance tests, BIPOC disabled trans students reported much higher physical violence rates in college bathrooms than white disabled trans students. What's more, around half of all disabled trans students are not currently living full time as their gender identity because of fear of mistreatment at school.

Health Outcomes

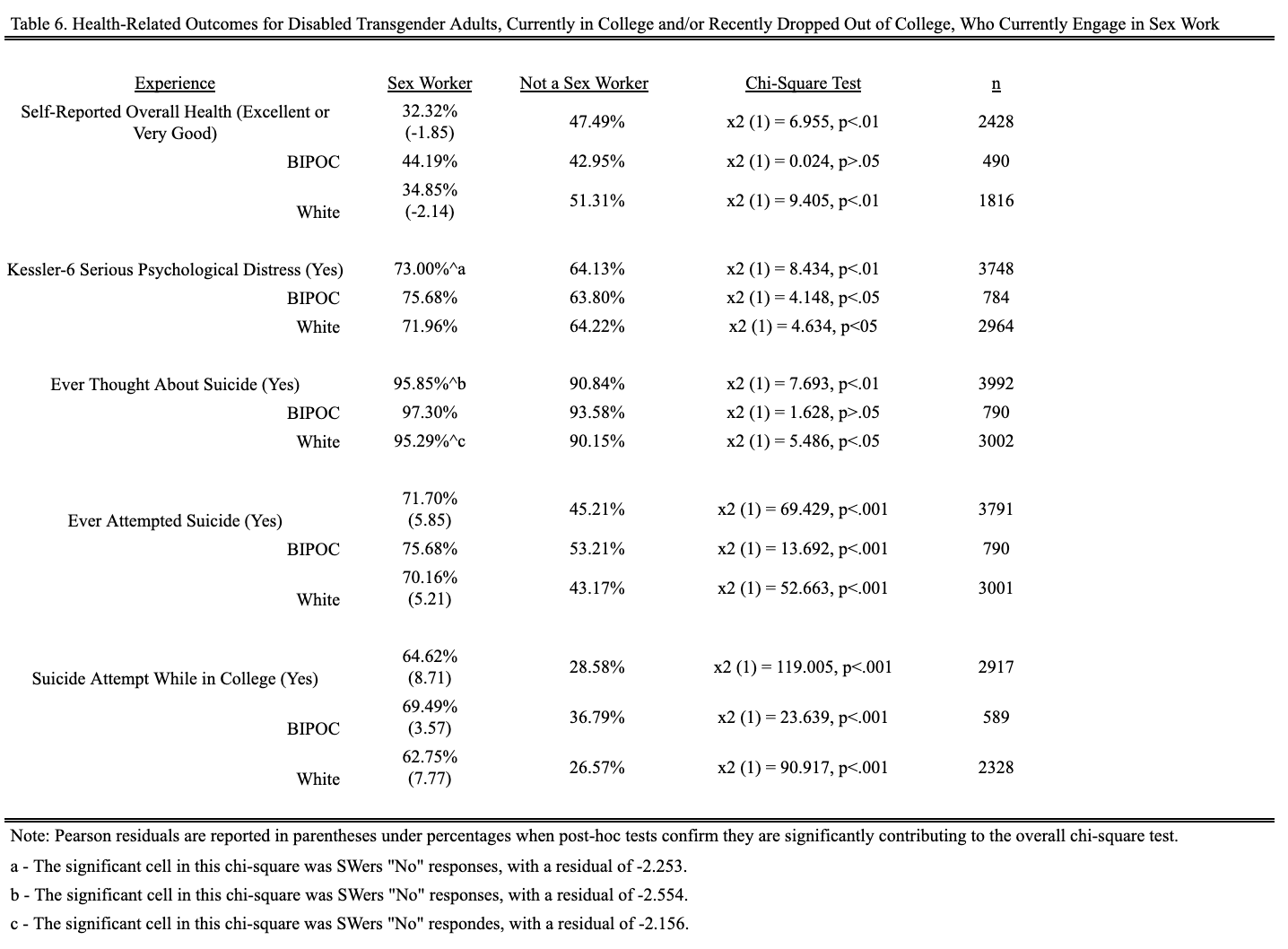

It's a stressful and traumatic lived reality to be both "out" to more people at school and also face lacking support of peers and harassment, violence, and discrimination from multiple fronts; as such, we detail (in Table 6 below) some of the various health related outcomes disabled trans college student sex workers report. Those currently engaged in sex work are significantly less likely to rate their current overall health as very good or excellent, significantly more likely to meet the criteria for serious psychological distress in the past 30 days, and significantly, but only marginally meaningfully, more likely to have experienced lifetime suicidal ideation. Perhaps most starkly, disabled trans student sex workers are 1.6 times more likely to report having ever attempted suicide (71.70% vs. 45.21%) and nearly 2.3 times more likely to report that their most recent attempt happened while they were in college (64.62% vs. 28.58%). Post-hoc chi-square tests do not indicate significant differences between white and BIPOC disabled trans students.

Key Takeaways

The Incidence and Prevalence of Disability Among Transgender College Students

Contrary to what some might assume about the nature of disability, the transgender emerging adult (under 35) college student population is more likely to report various types of disabilities and more likely to self-identify as disabled than older folks. This paper finds that, in the U.S. Transgender Survey (2015), 49.18% of trans college students report a specific disability and/or identify as disabled. While there is no "cisgender" sample of college students to compare our data to (because national surveys use "male" and "female," and most primary data collected on college students doesn't survey gender identity and disability), we do know that approximately 19% of college students meet the Healthy People 2020 standardized disability assessment threshold (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2021). There are numerous reasons why we might see higher rates of disability in this survey, versus general education statistics data collection. The first is that the Department of Education data does not include the option to self-identify, while ours does. Because over 30% of trans college students self-identify, we might be seeing "elevated" rates of disability that reflect a diagnostic change and/or reduction in stigma over time, rather than a prevalent increase in disability itself. Another explanation might be that the size of the trans college student population is not large enough to greatly impact the Department of Education averages, but that if we did collect data on gender identity, we would see higher rates among our trans students.

Disabled Transgender College Student Wellbeing

Importantly, for our trans college student population, the nature of their disabilities is most frequently invisible to those around them (e.g., 40.19% of trans college students report difficulty concentrating, memory, and decision-making). Invisible disabilities are often seen by and framed, interpersonally and socially, as "illegitimate" or "made up," and result in bias, stigma, and internalized shame (Kreider, Benedixen, & Lutz, 2015; Olkin et al., 2019; Ysasi, Becton, & Chen, 2018). This may be one reason for the significantly high psychological distress and suicidality rates among disabled trans college students. Regardless of engagement in sex work, no fewer than 64% of disabled trans college students met the criteria for serious psychological distress; meaning, 64-76% of disabled trans college students experience feelings of nervousness, hopelessness, restlessness, worthlessness, and depression that is not impacted by the efforts of others around them, most or all of the time in the past 30 days. In general U.S.A. college student samples (that use the Kessler-6 Distress Scale used in this study, but that do not assess gender identity), rates of serious psychological distress hover around 9% (Knowlden, Hackman, & Sharma, 2016; Shafer, Koenig, & Becker, 2017), with one more recent study from one mid-sized, four-year, public institution finding rates of 21.4% (Becerra & Becerra, 2020).

Moreover, an overwhelming 90% or more of disabled trans students reported lifetime suicidal ideation, with sex working students significantly more likely to report lifetime suicide attempts and suicide attempts while in college; specifically, two-thirds (65%) of disabled trans sex working college students report attempts while enrolled in their degree-seeking programs, a rate that is twice that of their non-sex working peers. While most of the data on transgender mental health aligns with our findings here (e.g., high rates of suicidality), it should be noted that a recent meta-review of the literature found that lifetime suicidal ideation among college students in the U.S.A is 22.3%, lifetime suicide attempt is 3.2%, and past-year suicide attempt is 1.2% (Mortier et al., 2018). This means that disabled trans college students are, on average, approximately four times more likely to report lifetime suicidal ideation than the general college student population and 13-23 times more likely to report a lifetime suicide attempt. To the authors' knowledge, there are no other studies that assess suicide attempts while enrolled in college (typically, surveys assess lifetime and/or past 12-month rates), but given that past-year attempts usually fall between 1-2% for the college student population, we wouldn't expect to see rates close to those we see for disabled trans students here (e.g., 65%).

The Systemic and Structural Nature of Health Disparities

These mental health outcomes are significantly higher for disabled trans student sex workers, which may be partially explained by the other forms of systemic exclusion and violence those students face. For instance, disabled trans sex working students are significantly more likely to report having been fired from or lost a job in their lifetime–many indicating that gender identity and/or disability-based prejudice and bias was the reason–with BIPOC students reporting the highest levels of lifetime job loss. Additionally, nearly twice as many sex working students indicated they experienced past-year job harassment/violence, compared to non sex-working students. Perhaps the prevalence of harm in the workplace is one of the reasons, if not a primary reason, that approximately 33% of disabled trans sex working students decided to quit their jobs in the past year.

Moreover, while a majority of disabled trans students are "out" to their peers in school, most students report that their peers are not supportive; indeed, while about half of non-sex working disabled trans student population say their peers are supportive, only 37% of sex working students report such support. Interestingly, we do find that sex working students are less likely to report past year harassment and physical/sexual assault in bathrooms, even though they report nearly double the amount of harassment in other situations (e.g. extracurriculars, by peers in the classroom, by faculty, by support staff). In total, and likely due to the overwhelmingly high numbers of harassment, discrimination, and violence faced by disabled trans students, about half are not living full time as their gender identity, specifically because of fear of mistreatment at school, unsupportive peers, fear of mistreatment by peers, and past year harassment/violence in college. The impacts of this mistreatment are likely pronounced for many BIPOC students, who–despite our not having the sample size to confirm statistically–preliminarily report much higher rates of past year physical assault in bathrooms.

Compounding the effects of job loss and violence at work, unsupportive peers, and violence at school, we must also consider how the "risk" and "deviance" discourse further stigmatizes disabled trans students (Dir et al., 2015; Dir et al., 2018; Ingram et al., 2019; Liong & Cheng, 2019; Reyns et al., 2014; Strassberg et al., 2017). Although trans disabled people engaged in this work may not be seeking to be clearly and publicly visible, negative visibility of being a sex worker (related to stigma) and the invisibility of engaging in sex work from home–particularly as a trans person who may or may not have told peers or family they are trans–has the potential to create environments of isolation and exclusion that contribute to the negative health outcomes previously discussed (Hamilton, Barakat, & Redmiles, 2022).

Main Conclusions

Disabled and transgender college students experience far-reaching discrimination, harassment, violence, and economic precarity while in school. At least 11% of disabled transgender college students have engaged in sex work during their college career. For those students, the consequences of structural and interpersonal violence and economic precarity are concerning: nearly 70% report poor health, 96% reported distress levels so high it resulted in seriously considering suicide, and 65% have attempted suicide while in college. Given this, the mental, emotional, psychological, social, and economic health and well-being of disabled transgender college students must be a central priority for all faculty, staff, administrative decision-makers, and student resource service providers.

Indeed, several implications for student service providers on college campuses emerge from our findings, which bolster the nascent research of Stewart (2021), who found that sex working college students experienced high levels of distrust and fractured confidence in faculty and staff, leading to the experience of institutional betrayal. For this study, we have broken student services into three main categories: Identity-Based (e.g., LGBTQ Centers, Race/Ethnicity-Based Centers, Religious Centers, Student Disability Services, Financial Aid, etc.), Health-Based (e.g., Student Health, Counseling Services, Wellness Center, etc.), and Administrative and Policy-Based (e.g., Dean of Students, Student Conduct, Career Service, etc.).

Implications for Identity-Based Student Services Providers

Given the demographics of our sample population being relatively diverse regarding sexual orientation, gender identity, and religiosity, it's safe to assume that students are coming into contact with a large number of identity-based student resources and student service providers such as student disability services, women's centers, LGBTQ+ centers, multicultural centers, religious groups, and other affinity groups. Students who live at the intersection of multiple minoritized identities (e.g., BIPOC, disabled, trans sex workers) are often left with a number of student service offices to choose from, each one only engaging one facet of their identity (for example, an LGBTQ+ student center, disability services office, Black Student Association, etc.). As these multiply-minoritized students have the potential to utilize any one of these identity-based resources, student service providers must challenge themselves to understand the populations they serve through the lens of intersectionality and not just their specific competency area. As Duran, Pope, and Jones (2020: 521) pointedly ask, "How do educators attend to the unique experiences of individuals while also considering larger structures of inequality in which people reside, institutional policies are created, and the disproportionate ways structures and policies impact certain groups?"

Further, student service providers' general lack of awareness and information regarding sex working students (Sagar et al., 2015b; Stewart, 2022) poses a significant barrier in approaching the needs of today's college students. As engagement in sex work becomes more common and normalized among college students, student affairs professionals must educate and adapt to avoid further stigmatization, pathologization, and/or criminalization. The Student Sex Work Project Report's Key Recommendations is a great place to start (Sagar et al., 2015b: 39), as it outlines key professional development, staffing, and policy-related decisions universities should engage in for the well-being of their student sex worker population.

Implications for Health-Based Student Services Providers

Student service providers positioned in health-based offices, such as counseling, wellness, and student health centers, face specific issues with LGBTQ+ students' concerns involving confidentiality, sensitivity, and discrimination (Reeves et al., 2021), all of which create a level of mistrust and act as barriers to entry for disabled trans students. This is magnified for BIPOC students, who often experience structural racism in health care settings, and report microaggressions, model-minority stereotypes, and a lack of cultural competence around familial and spiritual influences on their mental health from psychological student service providers (Hingwe, 2020). To counteract this level of uncertainty and mistrust, health-based student services must continue and enhance their outreach efforts, programming, and staff specialization regarding serving minoritized populations. We believe that psychological and health-based student services offices should hire, and work to retain, adequately compensated, diverse staff and clinicians. More than that, as health providers continue to enhance the pipelines that bring in a diverse range of students, providers are then ethically obligated to expand their current level of knowledge and practice to provide culturally and clinically competent care to the students that they serve, which includes educating themselves and implementing evidence-based practices.

Specific to this study, the increased experiences of psychological distress, thoughts of suicide, and suicide attempts among disabled trans students engaging in sex work suggest that all health providers meeting with trans students and/or disabled students must be well-versed in suicide assessment and safety planning, as well as how psychological distress and suicidality impact and are magnified by other aspects of identity and structural inequality. Once more, it's also crucial for health service providers to understand student engagement in sex work from a sex-positive perspective. Sex work is no more emotionally taxing to person's overall well-being than any other job, including psychology/psychiatry (Russell & Garcia, 2014), and sex work is not an inherently unhealthy choice. Rather, it is "whore stigma" (Benoit et al., 2018) itself that is the culprit of sex workers' differential working conditions and health outcomes (Krüsi et al., 2018).

Implications for Administrative and Policy-Based Student Services Providers

Those professionals operating in administrative or policy-oriented roles such as career centers, Dean of Students' offices, or conduct offices need to recognize that no policy or practice will affect every student in the same way, many policies act as "double-edged swords" that bring both benefit and cost to students, and some policies are simply enacted for show, without any adequate enforcement or regulation. For example, though the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requirements create "protections" for disabled individuals in schools and workplaces—much like anti-discrimination laws say they protect transgender people–they often ultimately provide more decision-making power to the state or institution, than to the individual (Spade, 2015). Transgender people already face many challenges to their identities via the legal system. Disability, and the way it interacts with the law, multiplies these effects. With regards to employment, trans people notably have their gender policed by identity documentation requirements, which creates a barrier to employment, and, in this way, employers can fairly easily choose to not hire and/or fire trans people, whose documents do not align with their identities (Spade, 2015: 80).

Similarly, career services or career centers at colleges and universities need to consider who their practices benefit. First, the damaging stigma regarding sex work must be challenged by providers in these settings. Providers must also be willing to validate the legitimacy of sex work as work. The "professionalism" idealized in career counseling has harmful roots in white supremacy - which is inextricably linked to heterosexism, transphobia, classism, and ableism (Cumberbatch, 2021; Gray, 2019; Marom, 2019; McCluney et al., 2021; Small, 2021). Without critical consideration of the realities of disabled trans sex working students, career counseling practices may ask already minoritized students to engage in a politics of respectability that intensifies their health-related outcomes and compounds harm.

Lastly, existing sex trafficking policies at the state and federal levels often have a disproportionately negative impact on sex workers, trans folks, and disabled people, which we've found in this analysis are prominently overlapping groups of students (Brooks, 2020: 516; Hagen, 2018; O'Brien, 2015, Stabile, 2020). Colleges and universities should take strong stances of support for sex working students, just as they often do (and, if not, should) for Black, Indigenous, and other students of color, disabled students, and trans students.

Implications Across Student Services Providers

Cross-functional collaboration (i.e., collaboration across and between student services offices, faculty, and the university community) has become an increasingly popular theoretical approach to providing student services (Kezar, 2006). Cross-functional collaboration lends itself to an intersectional ontology. It challenges student service providers with different content areas (e.g., development, health, administrative and policy-based) to work together to understand the needs of the "whole" student, rather than the individual facet of the student's identity. If given space, usually through task forces or working groups, identity-based student service providers could talk with students about their lived experiences and shape policy decisions and cross-sector collaboration around the findings

Here, we can look to the work of Trueman, Hagelberg, and Sanders (2020), at the University of Leicester, who suggest not only education and cultural competency trainings for staff, but also challenging university policy reporting procedures (e.g., challenging mandatory reporting requirements that break student confidentiality and trust), challenging university "decency" policies (that would see "outed" sex workers expelled for ruining a university's reputation), not involving the police in any matters regarding students, and utilizing a harm reduction approach that does not reinforce the "victim" narrative. Additionally, specific services that sex working students request in Stewart (2021), include: free sexually-transmitted infection (STI) testing, increased access to birth control and contraceptives, comprehensive sexual health education, staffing a diverse (e.g., not cisgender men, not white women) counseling services center, specific emergency financial aid/loan programs, food banks or free food resources, putting on sponsored events (speakers, programs, workshops, tabling) through key offices on/by/for sex workers (from an accepting and competent, not stigmatizing perspective), and inclusion on institutional messaging, advertising, websites, and brochures.

A Call to Action: Student Services for Disabled Trans Sex Workers

The theorized increasing involvement of college students in sex work puts pressure on institutions of higher education to pay attention to these issues (Ernst et al., 2021). Colleges and universities are already tasked with supporting diverse student populations and student needs, which manifests itself in identity-based resource centers (e.g., "LGBTQ+" Student Centers, Student Disability Centers, Office of Multicultural Student Affairs offices, etc.). To the authors' knowledge–and based on extensive searching online and via our shared community networks–there are currently no official (e.g., school-sanctioned) sex worker affinity groups or student services offices at any U.S.A. college or university. About Sex Work AU (American University) is a student-run club, that started as a group project for an AU Professor's experiential learning course, and is aimed at the destigmatization of sex work through education and outreach; but it is not, to our knowledge, run by and/or for sex workers.

As this piece details, there is likely a sizable disabled transgender sex working student body on most college campuses; and, as such, we turn our attention to the limitations and possibilities of campus-based resources and support systems in the discussion. However, it's important to note that campus-based supports are not always as diverse, inclusive, and equitable as they aim or claim to be. Despite the increasing presence of LGBTQ+ student centers across U.S. college and university campuses (Marine, 2011; Patton, 2010), for instance, little is known about the impact they have on the students that they serve. Marine & Nicolazzo (2014) highlight the limitations of LGBTQ+ centers to serve all sexual and gender minoritized students, specifically trans students and students whose identities aren't readily identified within the "LGBT" acronym (e.g., pansexual, demisexual, nonbinary, ace). In one of the only studies to explore sex working students' experiences with student services and the faculty and staff responses to those students, Sagar et al. (2015b) describe that, while some student services staff members work with students who disclose their participation in sex work, those staff members often lack the tools and information to address the students' needs appropriately. A recently completed thesis also outlines how, specifically, Black registered student organizations on U.S. college campuses reproduce White respectability politics, that disenfranchise Black sex workers on campus (Morrow, 2021). Thus, it seems that there are clear access limitations for students who exist at the intersection of two or more minoritized identities (Harley et al., 2002), and, without a clear sense of where to go, these students may choose not to go anywhere (Stewart, 2021).

As such, we support Stewart's (2021) conclusion that, if educators, faculty, staff, and student service providers "have any interest in seeking to support college student sex workers, then we must think about and implement programs and initiatives that sex workers can take advantage of that (a) benefit many students broadly—but sex workers specifically (b) because this allows them to never have to come forward." We call all student services providers back into action, encouraging colleges and universities everywhere to consider creating official offices and/or service provider programs for sex working students, as well as allow the formation of sanctioned—and therefore benefitted—sex working affinity groups, such as Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP) chapters.

Our work sheds light on how all students, but particularly disabled trans sex working students, would benefit from being better economically resourced, with stronger administrative support via cross-collaborative partnerships and programming, and informed and competent service providers, who work together—and not in isolation—to provide education to the broader campus community and outreach directly for sex positive student sexual health. In the end, we must empower students to be their whole selves during their time in college, and provide opportunities for them to live flourishing, pleasurable lives once outside of our ivory walls.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this paper were not funded for this project. However, the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) reported the following in regards to the collection of the 2015 National Transgender Discrimination Survey: "NCTE would like to express special appreciation to an anonymous donor for providing the largest share of the funds needed to conduct and report on the U.S. Transgender Survey. Other important funders were the Arcus Foundation, the Gill Foundation, the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, and the David Bohnett Foundation. NCTE is also grateful to its other funders, many of which supported this project through general operating support, including the Ford Foundation, the Evelyn & Walter Haas, Jr. Fund, and the Tides Foundation."

References

- Agresti, A. (1997). A model for repeated measurements of a multivariate binary response. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92(437), 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1997.10473629

- Agustín, Laura Maria. 2007. Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry. London: Zed Books. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350222496

- Andrews, E. E., Forber-Pratt, A. J., Mona, L. R., Lund, E. M., Pilarski, C. R., & Balter, R. (2019). # SaytheWord: A disability culture commentary on the erasure of "disability". Rehabilitation psychology, 64(2), 111. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000258

- Attwood, Feona. 2010. Porn.Com: Making Sense of Online Pornography. New York: Peter Lang.

- Baral, S., Todd, C. S., Aumakhan, B., Lloyd, J., Delegchoimbol, A., & Sabin, K. (2013). HIV among female sex workers in the Central Asian Republics, Afghanistan, and Mongolia: contexts and convergence with drug use. Drug and alcohol dependence, 132, S13-S16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.004

- Becasen, J. S., Denard, C. L., Mullins, M. M., Higa, D. H., & Sipe, T. A. (2019). Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006–2017. American journal of public health, 109(1), e1-e8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304727

- Becasen, J. S., Morris, J. D., Denard, C. L., Mullins, M. M., Kota, K. K., & Higa, D. H. (2022). HIV care outcomes among transgender persons with HIV infection in the United States, 2006–2021. AIDS, 36(2), 305-315. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003109

- Becerra, M. B., & Becerra, B. J. (2020). Psychological distress among college students: role of food insecurity and other social determinants of mental health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114118

- Benoit, C., Jansson, S. M., Smith, M., & Flagg, J. (2018). Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4-5), 457-471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652

- Bettio, F., Giusta, M. D., & Tommaso, M. L. D. (2017). Sex Work and Trafficking: Moving beyond Dichotomies. Feminist Economics, 23(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2017.1330547

- Betzer, F., Köhler, S., & Schlemm, L. (2015). Sex Work Among Students of Higher Education: A Survey-Based, Cross-Sectional Study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(3), 525–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0476-y

- Blewett, L. (2019). Disability and sexual health: a critical exploration of key issues. Disability & Society, 34(5), 850-851. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1589746

- Brookfield, S., Dean, J., Forrest, C., Jones, J., & Fitzgerald, L. (2020). Barriers to accessing sexual health services for transgender and male sex workers: a systematic qualitative meta-summary. AIDS and Behavior, 24(3), 682-696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02453-4

- Brooks, S. (2020). Innocent White Victims and Fallen Black Girls: Race, Sex Work, and the Limits of Anti–Sex Trafficking Laws. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 46(2), 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/710816

- Brown, C. C., Conner, S., & Vennum, A. (2017). Sexual Attitudes of Classes of College Students Who Use Pornography. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 20(8), 463–469. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0362

- Brown, L. X. Z. (2017). Ableist shame and disruptive bodies: Survivorship at the intersection of queer, trans, and disabled existence. In Religion, disability, and interpersonal violence (pp. 163-178). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56901-7_10

- Cameron, C. (2007). Whose problem? Disability narratives and available identities. Community Development Journal, 42(4), 501-511. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsm040

- Capous‐Desyllas, M., & Loy, V. (2020). Navigating intersecting identities, self‐representation, and relationships: A qualitative study with trans sex workers living and working in Los Angeles, CA. Sociological Inquiry, 90(2), 339-370. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12350

- Cotaina, M., Peraire, M., Boscá, M., Echeverria, I., Benito, A., & Haro, G. (2022). Substance use in the transgender population: a meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 12(3), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12030366

- Cumberbatch, S. (2021). When Your Identity Is Inherently" Unprofessional": Navigating Rules of Professional Appearance Rooted in Cisheteronormative Whiteness as Black Women and Gender Non-Conforming Professionals. JCR & Econ. Dev., 34, 81.

- Das, G. (2016). Mostly normal: American psychiatric taxonomy, sexuality, and neoliberal mechanisms of exclusion. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(4), 390-401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-016-0259-4

- Del Rio, K., & Pezzutto, S. (2020). Professionalism, pay, and the production of pleasure in trans porn. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 7(2), 262-267. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-8143435

- Dennis, J. P. (2008). Women are victims, men make choices: The invisibility of men and boys in the global sex trade. Gender Issues, 25, 11-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-008-9051-y

- Dick-Mosher, J. (2015). Bodies in contempt: Gender, class, and disability intersections in workplace discrimination claims. Disability Studies Quarterly, 35(3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i3.4928

- Dir, A., Cyders, M., Dir, A. L., & Cyders, M. A. (2015). Risks, Risk Factors, and Outcomes Associated with Phone and Internet Sexting Among University Students in the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(6), 1675–1684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0370-7

- Dir, A. L., Riley, E. N., Cyders, M. A., & Smith, G. T. (2018). Problematic alcohol use and sexting as risk factors for sexual assault among college women. Journal of American College Health, 66(7), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1432622

- Dunn, D. S., & Burcaw, S. (2013). Disability identity: exploring narrative accounts of disability. Rehabilitation Psychology, 58(2), 148. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031691

- Earp, B. D., & Moen, O. M. (2016). Paying for sex - Only for people with disabilities? Journal of Medical Ethics, 42(1), 54–56. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2015-103064

- Ernst, F., Romanczuk-Seiferth, N., Köhler, S., Amelung, T., & Betzler, F. (2021). Students in the Sex Industry: Motivations, Feelings, Risks, and Judgments. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 326. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.586235

- Fletcher-Watson, S., & Happé, F. (2019). Autism: a new introduction to psychological theory and current debate. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315101699

- Foubert, JohnD., Brosi, MatthewW., & Bannon, R. S. (2011). Pornography Viewing among Fraternity Men: Effects on Bystander Intervention, Rape Myth Acceptance and Behavioral Intent to Commit Sexual Assault. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 18(4), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2011.625552

- Freckelton, I. (2013). Sexual Surrogate Partner Therapy: Legal and Ethical Issues. Psychiatry, Psychology & Law, 20(5), 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2013.831725

- Friedman, M. (2015). "Epidemic of Neglect: Trans Women Sex Workers and HIV." In $PREAD: The Best of the Magazine That Illuminated the Sex Industry and Started a Media Revolution, edited by Aimee, Rachel, Kaiser, Eliyanna, and Ray, Audacia, 235–43. New York: Feminist Press.

- Fritsch, K., Heynen, R., Ross, A. N., & van der Meulen, E. (2016). Disability and sex work: Developing affinities through decriminalization. Disability & Society, 31(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2016.1139488

- Garcia, N. M., López, N., & Vélez, V. N. (2018). QuantCrit: Rectifying quantitative methods through critical race theory. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(2), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2017.1377675

- Gernsbacher, M. A. (2017). Editorial perspective: The use of person-first language in scholarly writing may accentuate stigma. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(7), 859-861. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12706

- Gignac, M. A., Bowring, J., Jetha, A., Beaton, D. E., Breslin, F. C., Franche, R. L., … & Saunders, R. (2021). Disclosure, privacy and workplace accommodation of episodic disabilities: organizational perspectives on disability communication-support processes to sustain employment. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 31(1), 153-165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09901-2

- Gill, C. J. (1997). Four types of integration in disability identity development. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 9(1), 39-46. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-1997-9106

- Gillborn, D., Warmington, P., & Demack, S. (2018). QuantCrit: Education, policy, "Big Data" and principles for a critical race theory of statistics. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(2), 158–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2017.1377417

- Glover, J. K. (2021). Customer Service Representatives: Sex Work among Black Transgender Women in Chicago's Ballroom Scene. South Atlantic Quarterly, 120(3), 553-571. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-9154913

- Glover, S. T., & Glover, J. K. (2019). " She Ate My Ass and My Pussy All Night": Deploying Illicit Eroticism, Funk, and Sex Work among Black Queer Women Femmes. American Quarterly, 71(1), 171-177. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2019.0010

- Graham, T. C. (2018). Conversion therapy: A brief reflection on the history of the practice and contemporary regulatory efforts. Creighton L. Rev., 52, 419.

- Gray, A. (2019). The Bias of 'Professionalism' Standards. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_bias_of_professionalism_standards

- Haeger, H., & Deil-Amen, R. (2010). Female College Students Working in the Sex Industry: A Hidden Population. NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education, 3(1), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.2202/1940-7890.1039

- Hagen, J. J. (2018). Compounding Risk for Sex Workers in the United States. NACLA Report on the Americas, 50(4), 395–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2018.1550984

- Hamilton, V., Barakat, H., & Redmiles, E. M. (2022). Risk, Resilience and Reward: Impacts of Shifting to Digital Sex Work. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.12728.

- Hardesty, M., & Gunn, A. J. (2019). Survival sex and trafficked women: The politics of re-presenting and speaking about others in anti-oppressive qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 18(3), 493–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325017746481

- Harley, D. A., Nowak, T. M., Gassaway, L. J., & Savage, T. A. (2002). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender college students with disabilities: A look at multiple cultural minorities. Psychology in the Schools, 39(5), 525–538. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10052

- Hingwe, S. (2021). Mental Health Considerations for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color: Trends, Barriers, and Recommendations for Collegiate Mental Health. In College Psychiatry (pp. 85-96). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69468-5_6

- Ingram, L. A., Macauda, M., Lauckner, C., & Robillard, A. (2019). Sexual Behaviors, Mobile Technology Use, and Sexting Among College Students in the American South. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117118779008

- Jackson, C. A. (2016). Framing Sex Worker Rights: How U.S. Sex Worker Rights Activists Perceive and Respond to Mainstream Anti–Sex Trafficking Advocacy. Sociological Perspectives, 59(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121416628553

- Jeffreys, S. (2008). Disability and the male sex right. Women's Studies International Forum, 31(5), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2008.08.001

- Jones, A. (2015). Sex work in a digital era. Sociology Compass, 9(7), 558-570. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12282

- Jones, A. (2016). "I get paid to have orgasms": Adult webcam models' negotiation of pleasure and danger. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 42(1), 227-256. https://doi.org/10.1086/686758

- Jones, A. (2020a). Camming: Money, power, and pleasure in the sex work industry. NYU Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479842964.001.0001

- Jones, A. (2020b). "It's Hard Out Here for a Unicorn": Transmasculine and Nonbinary Escorts, Embodiment, and Inequalities in Cisgendered Workplaces. Gender & Society, 0891243220965909. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243220965909

- Jones, A. (2022). 'People need to know we exist!': an exploratory study of the labour experiences of transmasculine and non-binary sex workers and implications for harm reduction. Culture, health & sexuality, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2021.2018500

- Jones, C. (2013). Paying for sex; the many obstacles in the way of men with learning disabilities using prostitutes. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2012.00732.x

- Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442-462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315588200

- Kessler, R. C., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Bromet, E., Cuitan, M., … & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2010). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 19(S1), 4-22. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.310

- Kezar, A. J. (2006). Redesigning for Collaboration in Learning Initiatives: An Examination of Four Highly Collaborative Campuses. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(5), 804–838. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2006.0043

- King, M., & Bearman, P. (2009). Diagnostic change and the increased prevalence of autism. International journal of epidemiology, 38(5), 1224–1234. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp261

- Kirkup, K. (2018). The origins of gender identity and gender expression in Anglo-American legal discourse. University of Toronto Law Journal, 68(1), 80-117. https://doi.org/10.3138/utlj.2017-0080

- Knowlden, A. P., Hackman, C. L., & Sharma, M. (2016). Lifestyle and mental health correlates of psychological distress in college students. Health Education Journal, 75(3), 370-382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896915589421

- Kreider, C. M., Bendixen, R. M., & Lutz, B. J. (2015). Holistic needs of university students with invisible disabilities: A qualitative study. Physical & occupational therapy in pediatrics, 35(4), 426-441. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2015.1020407

- Krüsi, A., Kerr, T., Taylor, C., Rhodes, T., & Shannon, K. (2016). 'They won't change it back in their heads that we're trash': the intersection of sex work‐related stigma and evolving policing strategies. Sociology of health & illness, 38(7), 1137-1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12436

- Kulig, T. C., & Butler, L. C. (2019). From "Whores" to "Victims": The Rise and Status of Sex Trafficking Courts. Victims & Offenders, 14(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2019.1595242

- Kuosmanen, J., & Starke, M. (2011). Women and men with intellectual disabilities who sell or trade sex: Voices from the professionals. Journal of social work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 10(3), 129-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/1536710X.2011.596424

- Laws, G., & Drew, E. (2022). 7 Crippling (Homo) nationalism. Homonationalism, Femonationalism and Ablenationalism: Critical Pedagogies Contextualised, 154.

- Lerum, K., & Brents, B. G. (2016). Sociological Perspectives on Sex Work and Human Trafficking. Sociological Perspectives, 59(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121416628550

- Levy, J., & Jakobsson, P. (2013). Abolitionist feminism as patriarchal control: Swedish understandings of prostitution and trafficking. Dialectical Anthropology, 37(2), 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10624-013-9309-y

- Liddiard, K. (2014). 'I never felt like she was just doing it for the money': Disabled men's intimate (gendered) realities of purchasing sexual pleasure and intimacy. Sexualities, 17(7), 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460714531272

- Liong, M., & Cheng, G. H.-L. (2019). Objectifying or Liberating? Investigation of the Effects of Sexting on Body Image. Journal of Sex Research, 56(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1438576

- Liu, C. H., Stevens, C., Wong, S. H. M., Yasui, M., & Chen, J. A. (2019). The prevalence and predictors of mental health diagnoses and suicide among U.S. college students: Implications for addressing disparities in service use. Depression and Anxiety, 36(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22830

- Long, S., Mollen, D., & Smith, N. (2012). College Women's Attitudes Toward Sex Workers. Sex Roles, 66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0088-0

- Mannino, G., Giunta, S., & Fiura, G. (2017). Psychodynamics of the Sexual Assistance for Individuals with Disability. Sexuality & Disability, 35(4), 495–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9491-y

- Marine, S. B. (2011). Stonewall's legacy: Bisexual, gay, lesbian, and transgender students in higher education. ASHE Higher Education Report, 37, 4.

- Marine, S. B., & Nicolazzo, Z. (2014). Names that matter: Exploring the tensions of campus LGBTQ centers and trans inclusion. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(4), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037990

- Marom, L. (2019). Under the cloak of professionalism: Covert racism in teacher education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 22(3), 319-337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2018.1468748

- McCluney, C. L., Durkee, M. I., Smith II, R. E., Robotham, K. J., & Lee, S. S. L. (2021). To be, or not to be… Black: The effects of racial codeswitching on perceived professionalism in the workplace. Journal of experimental social psychology, 97, 104199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104199

- Miller, R. A., Wynn, R. D., & Webb, K. W. (2019). "This really interesting juggling act": How university students manage disability/queer identity disclosure and visibility. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(4), 307. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000083

- Mogul, J. L., Ritchie, A. J., & Whitlock, K. (2011). Queer (in) justice: The criminalization of LGBT people in the United States (Vol. 5). Beacon Press.

- Morrow, R. N. (2021). The whores left behind: Black sex workers' college navigation & loneliness (Doctoral dissertation).

- Nellis, A. (2021). The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project.

- O'Brien, E. (2015). Prostitution Ideology and Trafficking Policy: The Impact of Political Approaches to Domestic Sex Work on Human Trafficking Policy in Australia and the United States. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 36(2), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2015.1019277

- Olkin, R., Hayward, H. S., Abbene, M. S., & VanHeel, G. (2019). The experiences of microaggressions against women with visible and invisible disabilities. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 757-785. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12342

- Onken, S. J., & Slaten, E. (2000). Disability identity formation and affirmation: The experiences of persons with severe mental illness. Sociological Practice, 2(2), 99-111. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010136801075

- Operario, D., Soma, T., & Underhill, K. (2008). Sex work and HIV status among transgender women: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 48(1), 97-103. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816e3971

- Orchard, T., Salter, K., Bunch, M., & Benoit, C. (2020). Money, agency, and self-care among cisgender and trans people in sex work. Social Sciences, 10(1): 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10010006

- O'Reilly, S., Knox, D., & Zusman, M. E. (2007). College Student Attitudes Toward Pornography Use. College Student Journal, 41(2), 402–406. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA163679010&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=01463934&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7E628e24c

- O'Toole, C. J. (2013). Disclosing Our Relationships to Disabilities: An Invitation for Disability Studies Scholars. Disability Studies Quarterly, 33(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v33i2.3708