Photo 1: A rolling field, edged with trees, on a sunny morning in Umoⁿhoⁿ Reservation. December 2017.

All is Kin

Morning in Umoⁿhoⁿ Territory, December 1, 2017. This is a sacred landscape, a place of ancestors and kin, of low and rolling hills, of life abundant, dark golden grasses and grey poplars. Fall is gone now, and the jagged trees are wiry, strong, and bare. Some sway in crowds on the ridges of the hills. Some prefer to be in pairs, even alone, standing on the distant horizon, or straining against a bit of barbed wire fence. The day is clear and very bright, so bright that sky seems to shift between whites and blues, and the sun flares out the camera lens. The trees and grass are bathing in the brief, raw heat, and the wind calls with a hollow, constant voice. Winter should be here; it is nearly here, though it comes later and milder now than it did in generations past.

Nothing in this landscape lives alone. Each tree, each blade of grass, the wind, the sun, the photographer, are bound together and belong to Wakoⁿ'da, the life force that animates all living things. Can there be such a thing as disability in this place? In'aska (Dennis Hastings) and Margery Coffey (Mi'oⁿbathiⁿ) explain that "all of this affluence came from the soil, the mother of all who walked upon her skin, or danced in celebration circles under her sacred trees, or slept in nests amid the grasses that formed her hair along the shorelines of the rivers and creeks that carried her life-giving blood to all who had need of it." 2 Disablement needs two parts: human difference and human contempt. It is a human decision to label a difference as less-than, a problem in need of fixing, an unwanted dependence. But this landscape, this mother, these spiny trees and vivid skies, Wakoⁿ'da, they could not know such a thing. All is one, and all is kin.

In this Umoⁿhoⁿ space and Umoⁿhoⁿ culture, there might be injury and illness, age and frailty, but nothing that could be called disability, at least not in any sense that separated some people from the rest of Creation. Before the settlers came, the weak or sick were never dismissed. Washna, a tender part of the buffalo intestine, was reserved for old people who had but few teeth; young people learned that if they ate it for themselves, dogs would bark at them during their excursions. 3 Those who could not participate in the annual hunt were known as he'begthiⁿ, "those who sit half-way." They stayed at home, guarding the village and watching the corn and squash grow taller and wider and yield bounty for a grateful people. 4 When a child reached the age of three or four and could go in whatever direction they pleased, the nation recognized them as an individual and they were inducted fully into the community. The ceremony included the community's hope that the child might reach the stage of life when they would "be bowed over," leaning on a staff. 5 Independence and dependence wove in and out of one another.

Dr. Francis La Flesche, Esq., an Umoⁿhoⁿ ethnographer, wrote in the early twentieth century that "[t]he white people speak of the country at this period as a 'wilderness,' as though it was an empty tract without human interest or history. To us Indians it was as clearly defined then as it is to-day; we knew the boundaries of tribal lands, those of our friends and those of our foes; we were familiar with every stream, the contour of every hill, and each peculiar feature of the landscape had its tradition. It was our home, the scene of our history, and we loved it as our country." 6 Elsewhere he explained that "[t]he people who made their homes on these streams had no printed literature, but the land itself was their book upon which was written the story of each tribe, full of human pathos." 7 The land, in the Umoⁿhoⁿ understanding, was stitched over with life and care and story. The history of disability and Indigenous peoples must be understood through this deep connection of peoples and landscapes, of human worth measured in the endurance of relation.

Competent and Incompetent

A deeply rutted dirt road on the bluffs of the Missouri river tells of a different people, of a landscape cut up and remade, of a love of economic productivity, of dirt bled dry. It carves through the leafless December trees, which cast long shadows at the close of day. Here, along the river, the settlers came. First were traders—and diseases—and in 1846 the Presbyterians set up a permanent mission on these same bluffs. But still the settlers wanted more. In the fall of 1853, they pressed the Umoⁿhoⁿ to agree to a treaty that would confine them to a reservation. A few days after the official signing the following spring, Commissioner of Indian Affairs George Manypenny wrote a ceremonial letter to one of the Umoⁿhoⁿ leaders, Joseph La Flesche. "On your return to the Omahas," it read, "you will find many perplexities and difficulties; but by constant perseverance and a firm determination to do right at all times and under all circumstances, you will be sustained in all your efforts for the civilization of your people; and it may be allotted to you to yet see them in an advanced state of intellectual improvement and each family comfortably situated." He recommended that La Flesche continue to enjoin his people in "habits of industry" and teach them to "abhor idleness," a "great responsibility" that, ironically, would never have needed to exist without the United States government's violent acquisitiveness. 8

The settlers called it the "removal of the Indian barrier," taking Indigenous land and insisting on the inferiority and termination of Indigenous culture. 9 As Ellen Samuels notes, they and their science viewed Indigenous people in terms that overlapped tightly with disability. This was, she explains, "not so much analogizing Indian minds to those of developmentally disabled individuals as merging the two into a flexible category of mental immaturity and incapacity." 10 For the Umoⁿhoⁿ, this was the beginning of disablement. Their minds and bodies and lifeways were judged and found wanting, and the government's policies only made things worse. Confinement to a reservation made them ill from hunger and anguish. The crops the Agents made them grow often failed, and the buffalo were unaccountably disappearing. Some relations were fracturing, and the land, too, would be fractured. In 1882, the federal government passed an Act to allot the Omaha reservation. They believed that by giving every head of a family, unmarried adult, and child his or her own plot of land to farm, they could press the Umoⁿhoⁿ to move forward toward assimilation, individualism, and citizenship. Each plot would be held in trust for twenty-five years, and the Agent, in consultation with his colleagues in Washington, would supervise any leases or sales until the Umoⁿhoⁿ had achieved what they termed, entirely without irony, "competence."

These government men did not know the soil, the mother of all; they knew only lucre and acreage, "self-reliant" farm families and balance sheets of debts and assets. Ableism's most potent work was to try to remake lands and bodies alike into a productive conformity. To break relation with the natural world and replace it with dominion. To deny both lands and peoples alternative ways of being and believing by condemning them as wild and incompetent. To rupture and injure, all to reify the rightness of Euro-American ideology.

With the allotments came a new centre for the reservation, as the settlers sought to move people closer to the new railroad some fifteen miles west of the river. 11 "[I]f the Indians obtained their patents and were to prosper," wrote the allotment officer, Alice Fletcher, "they must abandon their little fields in the bluffs of the Missouri and begin afresh on these fertile lands," and she remarked that "a considerable exodus from the bluffs was secured." 12 But it would not last. On the edges of the wide river, sacred ways persisted. Umoⁿhoⁿ ignored the government's categories of competence, its culture of ableism. Families lived together in community, caring for one another as they had in times past. 13 Though the land might be fenced, and deep roads might cut through it, relation with the earth and with one another could not be broken so easily.

An Umoⁿhoⁿ Healer

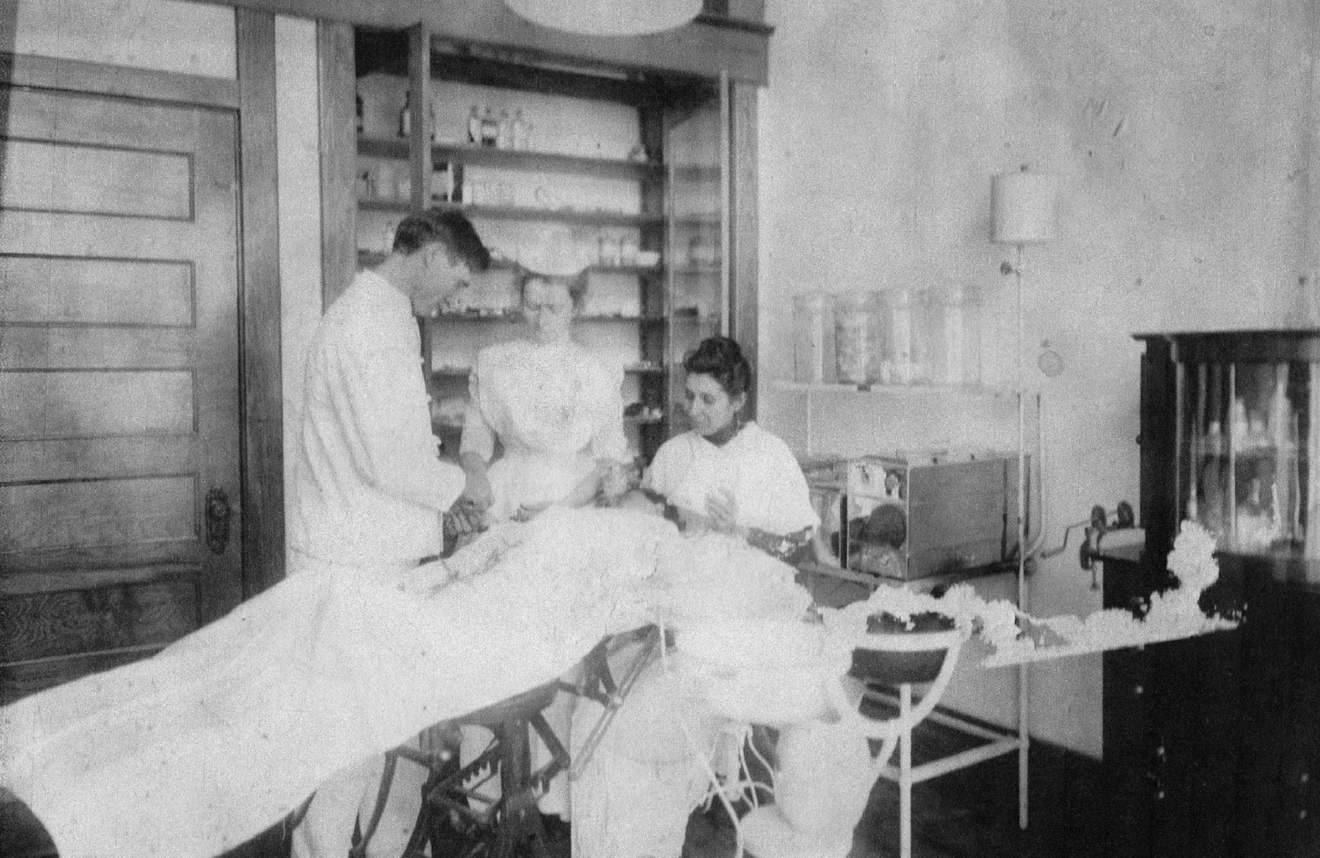

The first Indigenous physician in the United States, Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte was the daughter of Joseph La Flesche and half-sister of Francis La Flesche. She was an ardent Presbyterian and a committed student, and after she graduated from the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1889, she returned to the reservation on which she was born. A contemporary photo shows her operating on a patient, assisted by two other people. She sits serenely, her hair piled on top of her head, the latest in medical equipment behind her.

Photo 4: The clapboard building, now greyed with age, where Dr. Sue used to work. Walthill, Nebraska

A new hospital opened in Walthill in 1913, but many Umoⁿhoⁿ did not feel welcome in the space, and for much of her career Dr. Sue worked from a wooden outbuilding now used as a garage. Its boards are greyish, the door hinges rusted. It is tucked behind a large Edwardian house near the centre of town that once belonged to Dr. Sue's sister. Truly, the whole reservation was her hospital: Dr. Sue met people on their lands, sitting alongside Umoⁿhoⁿ as they gave birth and passed away in the places they loved and that loved them in return.

Though some on the reservation resented her piety and her interference, many turned to her, finding peace in the relation that settler-colonialism tried so hard to deny them. After she died in 1915, the Presbyterian Assembly Herald said that "[s]he often gave herself to the task of relieving others with what almost amounted to reckless regard for her own health and comfort." 14 Dr. Sue herself experienced chronic ear and mastoid infections and hearing loss, and she had numerous surgeries. In defiance of Euro-Americans' sexism and racism and ableism, she was a healer. She was needed, and she recognized, perhaps, that care was more important than cure.

Smoky Water

The Missouri River has been dammed up and reshaped, and her banks host a park on the reservation. There are paths and roads and poles strung with chains marking the drop down to her waters. But she still drifts, broad and blue, with tall cottonwoods still standing alongside her. She is a source of life for the Umoⁿhoⁿ: their name itself means "upstream people," a testament to the nation's kinship with her.

Sunaura Taylor writes that "ableism is a force that expands beyond disabled people. All bodies are subjected to the oppression of ableism." 15 What might it mean to consider the body of the land, the mother of all? "Disability studies and activism," Taylor also argues, "call for recognizing new ways of valuing life that aren't limited by specific physical or mental capabilities." 16 Indigenous relation sees such value in the landscape, too. For the Umoⁿhoⁿ, this includes Nishu'de Ke, Smoky Water, the Missouri River. She is kin, a source of life. Should she not share our same rights? In March 2017, New Zealand officially granted the Whanganui River the rights of personhood, able to stand in court through a committee of representatives and be protected from projects that might threaten its wellbeing. 17 Why should ableism diminish Nishu'de Ke and make less of her than of we who stand on her banks and breathe in her coolness, watch the light dapple over her beauty, drink freely of her waters, drift over her length to visit friends downstream? She is of us, and we of her.

Nishu'de Ke is kin, and she has been misused and underestimated, polluted and dammed up, disabled under settler governance and its ableist disregard for her wisdom and dignity and life. Indigenous disability studies and disability history know that difference and vulnerability should not compromise relation and worth, whether of people or the earth that sustains them. Notions like competent or incompetent, productive or unproductive, disabled or cured, have been used to hurt and carve up and separate people and landscapes alike. Liberation requires us to throw off the ableism that fractures the bonds of care and relation between people and with the earth, and know instead their sacred, inseparable connection.

Endnotes

-

Funding for Caroline Lieffers was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation, and Yale University.

Return to Text -

In'aska (Dennis Hastings) and Margery Coffey (Mi'oⁿbathiⁿ), "Grandfather Remembers: Broken Treaties/Stolen Land: The Omaha Land Theft," PhD dissertation, Western Institute for Social Research, 2009, 38.

Return to Text -

Alice C. Fletcher and Francis La Flesche, "The Omaha Tribe," in 27th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1905-1906 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1911), 331. We use the spellings provided by Fletcher and La Flesche.

Return to Text -

Fletcher and La Flesche, "Omaha Tribe," 99.

Return to Text -

Fletcher and La Flesche, "Omaha Tribe," 118.

Return to Text -

Francis LaFlesche, The Middle Five: Indian Boys at School (Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1901), xvii.

Return to Text -

Francis La Flesche, Ke-ma-ha: The Omaha Stories of Francis La Flesche, edited by James W. Parins and Daniel F. Littlefield Jr. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 32-33.

Return to Text -

Letter from George Manypenny to E-Sta-mah-za or Joseph La Flesche, March 20, 1854, in Omaha Reading Notes file, Box 22, MS 4558, Papers of Alice Fletcher and Francis La Flesche, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Return to Text -

Letter from Stephen A. Douglas to J.H. Crane, D.M. Johnson, and L.J. Eastin, December 17, 1853, published in the St. Joseph Gazette, March 15, 1854, in James C. Malin, "The Motives of Stephen A. Douglas in the Organization of Nebraska Territory: A Letter Dated December 17, 1853," Kansas Historical Quarterly 19 (November 1951): 352.

Return to Text -

Ellen Samuels, Fantasies of Identification: Disability, Gender, Race (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 178. Samuels is referring specifically here to the work of Samuel Morton.

Return to Text -

Alice Fletcher, Life Among the Indians: First Fieldwork among the Sioux and Omahas (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 321. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1ddr7sx

Return to Text -

Letter from Alice Fletcher to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, October 6, 1890, pages 2-3, letter 31703, Box 669, Letters Received, 1881-1907, RG 75 Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC.

Return to Text -

Mark J. Swetland, "'Make-Believe White-Men' and the Omaha Land Allotments of 1871-1900," Great Plains Research 4, no. 2 (1994): 230; 232, citing F.D. McEvoy, "A Thesis: Reservation Settlement Patterns of the Omaha Indians, 1854-1930," unpublished Honors Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1963.

Return to Text -

D.E. Jenkins, "Medical Mission Work Among the Omaha Indians," The Assembly Herald 22 (February 1916): 86.

Return to Text -

Sunaura Taylor, Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation (New York: The New Press, 2017), 21.

Return to Text -

Taylor, Beasts of Burden, 57.

Return to Text -

Mihnea Tanasescu, "When a River is a Person: From Ecuador to New Zealand, Nature Gets its Day in Court," Open Rivers: Rethinking Water, Place & Community 8 (2017), http://editions.lib.umn.edu/openrivers/article/when-a-river-is-a-person-from-ecuador-tonew-zealand-nature-gets-its-day-in-court/ and Kayla DeVault, "What Legal Personhood for U.S. Rivers Would Do," Yes! Magazine, September 12, 2017, https://www.yesmagazine.org/issues/just-transition/corporations-have-legal-personhood-but-rivers-dont-that-could-change-20170912 .

Return to Text