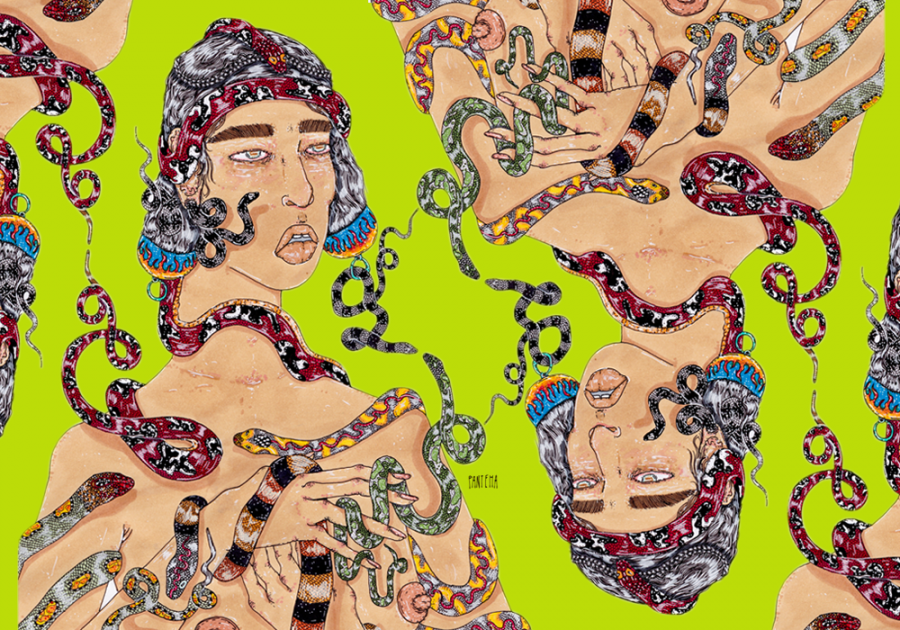

Contemporary disabled artist Panteha Abareshi illustrates "Indigenous Chronic Pain" (above) by surrounding a multiplied human with rattlesnakes. Abareshi, a Persian-Jamaican artist, sees her work as rooted in her "existence as a body with sickle cell zero beta thalassemia, a genetic blood disorder that causes debilitating pain and bodily deterioration" (para. 1). 1 The illustrated figure artwork carries the rattlesnakes—which seem to represent the embodiment of pain—delicately and without apparent fear; they may even serve as sources of power. The image recalls the "rattlesnake stories" of Cherokee and Laguna Pueblo writer Leslie Marmon Silko (94). In her memoir The Turquoise Ledge, Silko reflects upon seeing twin rattlesnakes that embody her grief, for she understands the snakes to be reincarnations of her late mother. Despite occasional fright, Silko also cares for her rattlesnake friend, Evo, as kin. 2

Historically, white Americans might have reacted to the rattlesnakes depicted above with incredulity, violence, and disgust. In an earlier North America as today, Euro-American settlers interpreted rattlesnakes as dangerous pests and "burn[ed] them alive in the name of Christianity" (Silko 110-111). Meanwhile, the great range of meanings and stories that diverse Native peoples applied to rattlesnakes was too "complex, varied, and at odds with how most Europeans saw them" for settlers to grasp (Levy 155). 3 For many Native nations, different snakes hold varied and particular meanings, but rattlesnakes often feature specially as "spiritual ancestors," powerful "skin-shedding warriors," (Levy 156), "divine messengers," and "bringers of rain" (Silko 110).

This essay attends to diverse meanings of rattlesnakes by first examining historical Western practices of exclusion and extermination and then (a few of many) Indigenous perspectives with an emphasis on Hopi communities' interrelationships with disabled, animalized beings. Such perspectives may invite (especially non-Native) disability scholars to embrace kinships with beings that Western culture has deemed pestilent, pitiful, and dangerous to human life but that many Indigenous cultures have understood to be empowering.

On record since at least the mid-eighteenth century and across the nineteenth century, white Euro-American settlers continuously essentialized Indigeneity as disability; characterized disability as animalistic; rendered Native people as animal-like and disabled; and depicted disabled Natives with particular animosity. 4 The relationship between disability and animality is, in literary studies scholars David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder's terms, "a strained one," for disabled people are sometimes oppressed through comparisons to the animal (1433). 5 Disability and environmental studies scholar Sunaura Taylor explains that many people want to distance themselves from both disability and animality due to "an urgent need among dehumanized populations (including disabled people) to challenge animalization and claim humanity" (20). Nevertheless, as Taylor argues, disability and animal justice must be incorporated into other liberation movements so that ableism and speciesism do not remain unchallenged tools used by systems of oppression. This essay responds to Taylor's claims, demonstrating that disability studies and Native American and Indigenous Studies have much to offer each other through attention to anti-ableist frameworks for valuing human and nonhuman life. 6 Further, the essay suggests that animal studies can more wholly connect these fields by challenging inextricably connected oppressions towards racialized, disabled, and animalized beings.

The historical and ongoing mistreatment of rattlesnakes (often performed in service of Western settlement) demonstrates that ableism adversely impacts all beings, as Indigenous perspectives make clear. Taylor wonders if it is safe yet to fully consider animals "as kin" (107), then asks if we can we make examining animals in relationship to disability "enriching, productive, and insightful?" (114). While specifically discussing Dakota personhood, Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate scholar of racial politics and technoscience Kim TallBear makes a statement that can almost be read as a response to Taylor's question. She writes: "Indigenous peoples have never forgotten that nonhumans are agential beings engaged in social relations that profoundly shape human lives…Indigenous approaches clearly link violence against animals to violence against particular humans who have historically been linked to a less-than-human or animal status" (231, my italics). 7 Indigenous approaches—specifically, practices that entangle human and rattlesnake bodies, as in the artwork above—might strengthen disability studies' efforts to challenge the harm ableism does to beings whose lives have been interpreted in terms of pain and animality.

Race, Disability, Animality in Early America

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, numerous white Euro-American authors compared Native people to Indigenous American animals. American animal comparisons hold distinctive meanings, for European authors argued that beings native to the Americas were inferior in body and mind to those native to Europe. American animals were said to have "deficiencies" of size and variety and were of "an inferior race"; some authors deduced that "human life had degenerated in the continents to match the low quality of its animals," for the American climate produces minds not suited to continued thought (quoted in Messer 604, my italics). As disability studies scholar Ellen Samuels shows, nineteenth-century anthropologists depicted Native Americans as examples of inferior human development, assessments which accompanied claims that intellectually disabled people represented a prior stage in human evolution. Samuels argues that the common philosophical ground in discourse was the "conflation of disability and Native blood with a presumed irrational animalism" (168). Native people were compared to animals, including buffalo—characterizations that drew upon discourses about civilization and disability to justify oppression. 8

White people fearfully killed the rattlesnakes indigenous to the Americas, representing the animals in terms of disability and as objects of fascination, disgust, and terror. 9 In a sense, rattlesnakes were interpreted as disabled; they were (and still are) represented as visually impaired, deaf, limbless, and slow of movement (Messer 607). Even their characteristic rattles were thought to disable them because the sound gave their locations away to settlers who then killed them (607). Several nineteenth-century white physicians incorrectly believed that rattlesnakes did not experience pain as other beings do and studied the animals as fascinating unfeeling objects. 10 Rattlesnakes were also seen as disabling—"terrifyingly dangerous" pests that posed a "wholly new terror" to the bodies of settlers (Levy 144). 11 Early Euro-American settlers performed community snake‐killings, killing hundreds of rattlesnakes at a time. 12 Travelers burned nests to make "Western settlement"—in other words, the possession of Native lands—"a little less dangerous" (Schuster 26). In the 1850s, eliminations migrated into a laboratory when white physician Silas Weir Mitchell killed 150 rattlesnakes to develop a venom antidote. 13 Seemingly both disabled and disabling, rattlesnakes were killed with fearful abandon.

Native peoples have often challenged white ableist violence towards rattlesnakes. To offer one of many examples: when white traveler James Adair and his (unnamed) Chickasaw traveling companion encountered a rattlesnake on the trail in the mid-eighteenth-century, his Chickasaw partner covered himself in snake root, removed the rattlesnake's fangs, then "tenderly" moved the snake away (quoted in Levy 301). 14 Adair promptly killed the rattlesnake. Adair rationalized this violence, arguing that since the animal had no more fangs, "'common pity should induce one to put it out of its misery'" (302). For disability scholars, this claim might strike a familiar chord. The rattlesnake was deemed pitiful because it was defanged and, in a sense, disabled. It was killed because it could not kill—a colonialist interpretation of the necessity of violence. As Taylor asserts, "the assumptions and prejudices we hold about disabled bodies run deep—so deep that we project this human ableism onto nonhuman animals" (23). 15 This "we" does not apply universally, however: the Chickasaw man "made his anger and objections known" for he knew "that such snakes required and deserved respect" (Levy 302). The Chickasaw man's actions—defanging to reduce potential harm to humans, and then defending the defanged rattlesnake as having a life worthy of life—revised Adair's assumptions about the necessity of killing nonhuman animals that are viewed as disabled.

Euro-American culture has conflated and systematically devalued Indigenous and animal lives, especially disparaging disabled Indigenous life. These violent sentiments prevail in the work of white traveler Francis Parkman, who, in his 1849 book The Oregon Trail, describes killing "four or five" rattlesnakes a day (133). Although Parkman orally dictated The Oregon Trail while he himself was visually impaired, he mocks both sighted and blind Oglala people through rattlesnake comparisons. He calls Oglala people "snake eyed," (13, 112, 132), complaining that he was "infested" by them (294), and he suggests that their impairments were caused by "savage" exposure to the sun (111). Parkman laughingly relates that when an elderly, blind Oglala woman "writhed" in pain—a term which evokes serpentine movement—a white physician purposefully burned her with a red-hot brand (137). Parkman represents his own visual disability as distinct (and less animalistic) from that of the Native people. His text offers a striking example of the ways white supremacist thought collapses Indigeneity with animality—and aligns Indigeneity with disability, as a "savage" state.

Interpretations of the Hopi Snake Dance in the nineteenth century further dramatize the differences between white and Native perspectives towards the kinds of interpersonal relationships between humans and rattlesnakes. During the nine-day ceremony, Hopi dancers carry live rattlers' heads in their mouths while performing ceremonial dances (as explained in 2008 by a member of the Hopi nation, Honvantewa Terrance Talaswaima, 64). In the late 1890s, journalists, cartoonists, and anthropologists depicted the ceremony in ways that reinforced notions of Native barbarism. Hopis were not necessarily portrayed as rattlesnake-like, but because "the rattlesnake's mouth was always a source of nervous attention" (Levy 147) for nineteenth-century white Americans, journalists in the 1890s interpreted the ceremony as "sexually-suggestive" (147) and cartoonists drew pictures of Hopis frowning while dancing "hysterically" with the rattlesnakes hanging from their mouths (Sakiestewa Gilbert 21). 16 Throughout the final decades of the nineteenth century, journalists implied that the ceremony was irrational, claims which evoke the "racially charged associations of feeblemindedness with animalism, brutishness, and primitiveness, qualities also inherent in many Euro-American characterizations of Indians" (Carlson 140). As I next discuss, Hopi beliefs about the value of disabled and animal life counter settler impulses to be afraid, to mischaracterize, and to destroy. The Snake Dance especially invites new ways of interpreting human and nonhuman, disabled and nondisabled, limbed and limbless movement.

Rattlesnakes and the Hopi Way 17

Hopis, who are indigenous to the northeastern Arizona mesas, aspire to treat human and nonhuman beings as empowered residents of the natural landscape. 18 According to Hopi scholar Sheilah E. Nicholas, the Hopi way is a "moral fiber manifest in communal attitudes and behaviors of industry, self-discipline, reciprocity, respect (naakyaptsi, self-respect, and tuukyaptsi, respect for others), responsibility, and obligation" (126, original italics). Disabled people are habitually included in Hopi communities, rather than ostracized, for communal attitudes of interdependency are fundamental to the Hopi way. 19

Respect and responsibility characterize most Hopi relationships with animals. Leslie Marmon Silko reflects that survival in an austere, hot environment depends "upon harmony and cooperation not only among human beings, but among all things—the animate and the less animate" (84). 20 The Hopi way values the "interaction and interrelationships with all beings above all else….Each ant, each lizard, each lark is imbued with great value simply because the creature is there, simply because the creature is alive in a place where any life at all is precious…Every possible resource is needed, every possible ally—even the most humble insect or reptile" (94). Because of this focus on allyship, rattlesnakes are only killed out of great need and with respect.

White Americans have displayed intense fear of debilitation, which culminates in violence towards animals. However, for Hopis, injuring animals without apology, or ridiculing an animal's weakness, could cause disharmony manifested in the body. As Native American education and wellness scholar Carol Locust (Eastern Cherokee) relates, one Hopi woman "was born with a club foot because her father had trapped a porcupine and cut off its forefeet" (2013, 132). Mistreatment of an animal brought about physical changes—the punishment for deviating from the Hopi way (Nielson 5). Disability becomes a moral punishment, an interpretation that many disability studies scholars consider problematic. 21 However, the Hopi view of disability differs from white settler views. The Hopi way emphasizes the importance of harmony between human and nonhuman animals—not nondisabled human supremacy. Disability is not universally celebrated in Hopi culture, but it is also not deemed less-than-human; animal lives also are not less valuable than those of humans.

In fact, the Hopi Snake Dance ceremony treats rattlesnakes not as pests, not even as pets, but as kin—and as part of the human body. Members of the Hopi Snake Clan make regular pilgrimages to gather snakes for the ceremony, and Hopi land use has been built, in part, around these gatherings (Bernardini 485). This ceremony then benefits Hopis through "weather control, fertility, and health" (Udall 23). Courage is significant to Hopi culture, and so during the ceremony Hopis treat rattlesnakes with respect while placing the snakes' mouths into their own mouths (Honvantewa 64). The rattlesnakes are sometimes defanged, but Hopis have largely kept methods for completing this ceremony—without harm to human or rattlesnake—private (65). The Snake Dance celebrates a nonviolent merging of humans with limbless and venomous nonhumans, destabilizing white settler constructed categories by temporarily reconfiguring the boundaries of the body. The Hopi treat rattlesnakes as empowered beings—not as animals deserving of extermination—a perspective that might be empowering, as well, for disability scholars fighting on behalf of those whose lives are devalued in white Western culture. The Hopi Snake Dance ceremony incorporates rattlesnakes within the boundaries of the human, a merging which invites reconsideration of "'radical valuing'—of bodies and nature, of bodily natures" (Alaimo 30).

The ritual of carrying the formidable mouths of rattlesnakes within their own mouths entails a merging between human and snake. This concept is found in the work of Natalie Diaz, a Mojave and Akimel O'odham poet whose volume Postcolonial Love Poem (2020) explores the pleasurable and painful embodied experiences of diverse Indigenous peoples. In "Snake-Light," Diaz calls the rattlesnake with its Mohave name hikwiir and voices a visceral critique of American rattlesnake round-ups. Part of the poem reads:

You can't know the rattlesnake's power

if you've never felt its first name form in your mouth—

like making lightning, unfolding fangs

from the soft palate of your jaw (84).

Diaz's poem evokes the fearlessness that might result from voicing—and becoming—the dangerous body of an animal white Americans have abused in fear. 22 For Diaz, speaking hikwiir engenders power with which to combat that white supremacist violence.

The rattlesnake holds a multiplicity of meanings in diverse Native views as spiritual ancestor, debilitating threat, and symbol for bridging the distance between body and word. These meanings offer opportunities for us to navigate the disparate disciplines of Native American and Indigenous studies, disability studies, and animal studies with grace. Indigenous understandings of kinship with animals offer the potential for co-existence, a rendering that might help scholars to imagine kinship more broadly, rather than selectively—and to challenge systems of ableism, speciesism, and racism while we reenvision the boundaries of the bodies we claim as our own.

Acknowledgement

I am very grateful to the early readers of this essay and to the DSQ reviewers and editors for their guidance. Thank you as well to Jean Franzino for offering insightful comments and feedback.

Works Cited

- "About Panteha Abareshi." Panteha Abareshi, Accessed 7 May 2021. https://www.panteha.com/about-panteha-abareshi.

- Alaimo, Stacy. Disability Studies and the Environmental Humanities: Toward an Eco-Crip Theory. U of Nebraska P, 2017.

- Altschuler, Sari. The Medical Imagination, Literature and Health in the Early United States. U of Pennsylvania P, 2018. https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812294743

- Arena, Phillip C. et al., "Rattlesnake Round-ups." Wildlife and recreationists: coexistence through management and research, edited by Richard L. Knight and Kevin Gutzwiller, Island Press, 1995, pp. 313-322.

- Bernardini, Wesley. "Identity as History: Hopi Clans and the Curation of Oral Tradition," Journal of Anthropological Research, vol. 64, no. 4, 2008, pp. 483-509. https://doi.org/10.3998/jar.0521004.0064.403

- Carlson, Licia. "Docile bodies, docile minds: Foucauldian reflections on mental retardation." Foucault and the Government of Disability, edited by Shelley Tremain, U of Michigan P, 2005, pp. 133-152.

- Chen, Mel Y. Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect. Duke UP, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11vc866

- Deerinwater, Jen. "Checkbox Colonization: The Erasure of Indigenous People in Chronic Illness." Bitch Media. June 8, 2018. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/in-sickness/checkbox-colonization-erasure.

- Diaz, Natalie. Postcolonial Love Poem. Graywolf, 2020.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. Columbia UP, 1997.

- Geroux, Robert. "Introduction to the Special Issue on Indigeneity and Animal Studies." Humanimalia, vol. 10, no. 2, 2019. https://doi.org/10.52537/humanimalia.9499

- Honvantewa (Terrance Talaswaima). "The Hopi Way: Art as Life, Symbol, and Ceremony." Hopi Nation: Essays on Indigenous Art, Culture, History, and Law, edited by Edna Glenn et al, 2008, pp. 65-74.

- Jaffee, Laura, and Kelsey John. "Disabling bodies of/and land: Reframing disability justice in conversation with indigenous theory and activism." Disability and the Global South, vol. 5, no. 2, 2018, pp. 1407-1429.

- Jones, David E. Poison Arrows: North American Indian Hunting and Warfare. U of Texas P, 2007.

- Kuppers, Petra. "Decolonizing Disability, Indigeneity, and Poetic Methods: Hanging Out in Australia." Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2013, pp. 175-193. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2013.13

- – "Edges of Water and Land: Transnational Performance Practices in Indigenous/Settler Collaborations." Journal of Arts & Communities, vol. 6, 2014, pp. 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaac.6.1.5_1

- –"Tiresian Journeys." TDR, vol. 52, no. 4, 2008, pp. 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.2008.52.4.174

- Levy, Philip. Fellow Travelers: Indians and Europeans Contesting the Early American Trail. UP of Florida, 2007.

- Locust, Carol. The Piki Maker: Disabled American Indians, Cultural Beliefs, and Traditional Behaviors. Native American Research and Training Center, U of Arizona, 1994.

- Lovern, Lavonna and Carol Locust. Native American communities on health and disability: A borderland dialogues. Springer, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137312020

- Messer, Peter C. "Republican Animals: Politics, Science and the Birth of Ecology." Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies, vol. 33, no. 4, 2010, pp. 599-613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-0208.2010.00325.x

- Mieder, W. "'The Only Good Indian Is a Dead Indian': History and Meaning of a Proverbial Stereotype." The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 106, no. 419, 1993, pp. 38–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/541345

- Mitchell, David T., and Sharon L. Snyder. "Precarity and Cross-Species Identification: Autism, the Critique of Normative Cognition, and Nonspeciesism." Disability Studies and the Environmental Humanities: Toward an Eco-Crip Theory, edited by Sarah Jaquette Ray and Jay Sibara, 2017, pp. 1432-84.

- Mitchell, Silas Weir. Researches Upon the Venom of the Rattlesnake: With an Investigation of the Anatomy and Physiology of the Organs Concerned. Smithsonian Institution, 1860. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.45454

- Nagy, Kelsi and Phillip David Johnson II, editors. Trash Animals: How We Live with Nature's Filthy, Feral, Invasive, And Unwanted Species. U of Minnesota Press, 2013.

- Nicholas, Sheilah. "Language, Epistemology, and Cultural Identity: 'Hopiqatsit Aw Unangvakiwyungwa' ('They Have Their Heart in the Hopi Way of Life')." American Indian culture and research journal, vol. 34, no. 2, 2010, pp. 126-142. https://doi.org/10.17953/aicr.34.2.2241355780153270

- Nielsen, Kim E. A Disability History of the United States. Beacon P, 2012.

- Otjen, Nathaniel. "Indigenous Radical Resurgence and Multispecies Landscapes: Leslie Marmon Silko's The Turquoise Ledge." Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 31, no. 3-4, 2019, pp. 135-157. https://doi.org/10.5250/studamerindilite.31.3-4.0135

- Parkman, Francis. The Oregon Trail. Edited by Elmer N. Feltskog. U of Nebraska P, 1994.

- Polish, Jennifer. "Decolonizing Veganism: On Resisting Vegan Whiteness and Racism." Critical Perspectives on Veganism, edited by J. Castricano and R. Simonsen, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 373-391. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33419-6_17

- Robles, Whitney Barlow. "The Rattlesnake and the Hibernaculum: Animals, Ignorance, and Extinction in the Early American Underworld." The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 1, 2021, pp. 3–44. https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.78.1.0003

- Samuels, Ellen. Fantasies of Identification: Disability, Gender, Race. NYU Press, 2014.

- Schipani, Sam. "At Rattlesnake Roundups, Cruelty Draws Crowds." Mar 10, 2018. Sierra Club. https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/rattlesnake-roundups-sweetwater-texas-cruelty. Accessed 4 May 2021.

- Schuster, David G. Neurasthenic Nation: America's Search for Health, Happiness, and Comfort, 1869-1920. Rutgers UP, 2011.

- Silko, Leslie Marmon. The Turquoise Ledge: A Memoir. Penguin, 2010.

- —Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit. Simon and Schuster, 2013.

- TallBear, Kim in Sam Spady, "Reflections on late identity: In conversation with Melanie J. Newton, Nirmala Erevelles, Kim TallBear, Rinaldo Walcott, and Dean Itsuji Saranillio." Critical Ethnic Studies, vol. 3, no.1, 2017, pp. 101. https://doi.org/10.5749/jcritethnstud.3.1.0090

- TallBear, Kim. "An Indigenous Reflection on Working Beyond the Human/Not Human." GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 21, no. 2-3, 2015, pp. 230-235.

- Taylor, Chloë, and Kelly Struthers Montford, eds. Colonialism and Animality: Anti-Colonial Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies. Taylor & Francis, 2020.

- Taylor, Sunaura. Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation. The New Press, 2017.

- Udall, Sharyn R. "The Irresistible Other: Hopi Ritual Drama and Euro-American Audiences." TDR, vol. 36 no. 2, 1992, pp. 23-43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1146193

- Weeks, Charles A. "Of Rattlesnakes, Wolves, and Tigers: A Harangue at the Chickasaw Bluffs, 1796." The William and Mary Quarterly , vol. 67, no. 3, 2010, pp. 487. https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.67.3.487

- Yava, Albert. Big Falling Snow, edited by Harold Courlander. U of New Mexico P, 1978.

Endnotes

-

Abareshi does not identify as Indigenous; this artwork seems to have been created for inclusion in an article by Cherokee writer Jen Deerinwater. See "Checkbox Colonization: The Erasure of Indigenous People in Chronic Illness." Bitch Media, June 8, 2018. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/in-sickness/checkbox-colonization-erasure.

Return to Text -

Silko is a mixed-race writer of Laguna Pueblo Indian, Cherokee, and Mexican American heritage. See Leslie Marmon Silko, The Turquoise Ledge: A Memoir. Penguin (2010). For scholarly work on the memoir, see Nathaniel Otjen's "Indigenous Radical Resurgence and Multispecies Landscapes: Leslie Marmon Silko's The Turquoise Ledge." Studies in American Indian Literatures vol. 31, no. 3-4 (2019), pp. 135-157.

Return to Text -

Speaking broadly of various tribes, Levy explains that rattlesnakes "were part of a world in which spirits, dead relations, distant ancestors, and god-like beings moved between the seen and unseen worlds. In that world all animals required respect if one were to live harmoniously with them…A snake could be an incarnation or representation of an animal spirit bearing a specific encoded message, a powerful force holding the keys to a trip's success or failure, or a lost friend or family member bearing news or advice" (155).

Return to Text -

For more on the ways settler colonialism continues to place Indigeneity on one side of a culture/nature binary that is toxic and harmful, but nevertheless demonstrates recognition of an unbroken humanimal bond, see Robert Geroux, "Introduction to the Special Issue on Indigeneity and Animal Studies" (2019). For more on eighteenth and nineteenth century characterizations that essentialize Indigeneity as disability, and disability as animalistic, see Ellen Samuels, Fantasies of Identification: Disability, Gender, Race (NYU Press, 2014). See histories of eighteenth-century written representations of Natives and animals in Philip Levy, Fellow Travelers: Indians and Europeans Contesting the Early American Trail (UP of Florida, 2007).

Return to Text -

Much contemporary scholarship still reads the "human" as the barometer of dignity and value. For more on the limits of the human, see Jennifer Polish, "Decolonizing Veganism: On Resisting Vegan Whiteness and Racism." In J. Castricano and R. Simonsen (eds), Critical Perspectives on Veganism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). Mel Y. Chen adds that when humans are compared to animals, they are not being compared "to that class of creatures that includes humans but quite the converse, the class against which the (often rational) human with inviolate and full subjectivity is defined" (95). See also the discussion of new perspectives on animality and disability in Colonialism and Animality: Anti-Colonial Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies. Chloë Taylor, and Kelly Struthers Montford, eds. (Taylor & Francis, 2020).

Return to Text -

As Laura Jaffee and Kelsey John argue, disability scholarship has too often neglected intersectional approaches and can learn much from Indigenous theory (2018).

Return to Text -

TallBear adds, "You do not get Indigenous peoplehood if you are only human-centric," and, "I think that is about being cut off from place that people forget we are not who we are just because of what is in our body, what is in our human kinship circles, but we are who we are in part because of where we have come from" (2017, pp. 101).

Return to Text -

To offer one of many comparisons of Native people to animals: Josiah Nott made the 1854 contention that "To one who has lived among American Indians, it is vain to talk of civilizing them. You might as well attempt to change the nature of the buffalo" (quoted in Samuels 175).

Return to Text -

For more about early rattlesnake killings, see Whitney Barlow Robles, "The Rattlesnake and the Hibernaculum: Animals, Ignorance, and Extinction in the Early American Underworld." The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 1, (2021), pp. 3-44.

Return to Text -

Nineteenth-century physicians including Oliver Wendell Holmes, Richard Harlan, and Silas Weir Mitchell grappled with questions about pain and its usefulness after the discovery of anesthesia. They turned to rattlesnakes as objects of study, influenced by Robley Dunglison's Human Physiology, which claimed that rattlesnakes lived "'largely without feeling'" (Altschuler 178). Claims that the animals feel little to no pain might relate to (but are not equivalent to) early American assertions that black people do not feel pain as white people do—a reminder of the animalizing approach white physicians have taken to black people in America (Samuels 14).

Return to Text -

Western views present "pest" animals (animals deemed harmful to human) as creatures devoid of subjective and emotional lives. As "pests," rattlesnakes are often placed low on constructed hierarchies of animacy. Mel Y. Chen describes "[w]hat linguists call an animacy hierarchy, which conceptually arranges human life, disabled life, animal life, plant life, and forms of nonliving material in orders of value and priority" (28). For more on violence against pests, see Kelsi Nagy, and Phillip David Johnson II, eds. Trash Animals: How We Live with Nature's Filthy, Feral, Invasive, And Unwanted Species. U of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Return to Text -

Comparable rattlesnake round-ups continue today, mainly in Oklahoma and Texas .Today's rattlesnake round-ups are justified by the popular quote "the only good snake is a dead snake" (Arena 313; Schipani, para. 4). This phrase quite clearly mimics the slur "the only good Indian is a dead Indian" repeated since at least the mid nineteenth century (Mieder 38).

Return to Text -

Mitchell's experiments led to the first major scandal surrounding large-scale animal experimentation in the U.S., largely because he also killed dogs and cats. His critics often admitted that rattlesnake killings could be justified or ignored, but saw dogs and cats as having subjective lives (Schuster 26).

Return to Text -

Like many other groups across the continent, the Chickasaw people used the herbs known as "snake root" to prevent and heal rattlesnake bites and to placate the animals. Europeans "quickly adopted" herbal cures and preventatives from Native people, "but they did not adopt the idealized relationship with rattlesnakes," nor did they see "methods of snake placating as a useful corollary" (Levy 299). Levy discusses this in his chapter on rattlesnakes in Fellow Travelers, which explores relationships between Native and white travelers in early America. The Chickasaw people recognized and appreciated the danger posed by rattlesnakes; moreover, in the late eighteenth century, Chief Ugulayacabé of the Chickasaw Nation represented white settlers as dangerously rattlesnake-like—a reversal of white comparisons of Native people to animals (Weeks 487).

Return to Text -

Taylor does acknowledge that representations of, and approaches to, disability "are not universal—they compound and shift across nationality, racial, gender, and class differences" (12-13). The Chickasaw man's actions might offer a specific example.

Return to Text -

For more on Euro-American readings of Hopi ceremonies, see Sharyn R. Udall, "The Irresistible Other: Hopi Ritual Drama and Euro-American Audiences." TDR (1988), vol. 36 no. 2 (1992), pp. 23-43. These journalists' depictions also might recall the work of Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, who discusses the ways (dis)abled people of color were brazenly compared to and treated as animals in nineteenth and early twentieth-century American and European sideshows. See Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (New York: Columbia UP, 1997).

Return to Text -

The phrase the Hopi Way is explained in the work of Sheilah E. Nicholas's "Language, Epistemology, and Cultural Identity: 'Hopiqatsit Aw Unangvakiwyungwa' ('They Have Their Heart in the Hopi Way of Life')." American Indian culture and research journal, vol. 34, no. 2, 2010, pp. 126-142.

Return to Text -

The Hopi are a self-identifying, geographically and socially discrete group with deep history, recounted from the perspectives of more than sixty different groups that are not homogenous. For more on Hopi history and culture, see Wesley Bernardini, "Identity as History: Hopi Clans and the Curation of Oral Tradition," Journal of Anthropological Research vol. 64, no. 4 (2008): pp. 483-509, and Albert Yava, Big Falling Snow, edited by Harold Courlander (University of New Mexico Press, 1978).

Return to Text -

For more on disability specifically in Hopi communities, see Lavonna Lovern and Carol Locust's Native American Communities on Health and Disability: A Borderland Dialogues (Springer 2013), and Locust's The Piki Maker: Disabled American Indians, Cultural Beliefs, and Traditional Behaviors (U of Arizona, 1994).

Return to Text -

While Silko is discussing Pueblo communities more generally (there are twenty Pueblo groups in the southwestern United States including Laguna and Hopi). these groups have some shared cultural stories: "We were not relocated like so many Native American groups who were torn away from their ancestral land. And our stories are so much a part of these places that it is almost impossible for future generations to lose them—there is a story connected with every place, every object in the landscape" (59).

Return to Text -

For example, Nancy L. Eiesland, The Disabled God: Toward a Liberatory Theology of Disability (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994); Edward Wheatley, Stumbling Blocks before the Blind: Medieval Constructions of a Disability (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010); Candida Moss and Jeremy Schipper, eds. Disability studies and biblical literature (New York: Springer, 2011).

Return to Text -

White disability studies scholars have also found in the Hopi celebration of rattlesnakes' limbless and venomous power a figure for more expansive ways to move through the world. Reflecting on Hopi rattlesnake stories, disability studies scholar and dancer Petra Kuppers observes: "Words bring us into the compass of experience: that is what a crip who cannot scale the hill can take from a poetics of the world, stepping with other feet" (181). For Kuppers's work on disability and Indigeneity, see "Edges of Water and Land: Transnational Performance Practices in Indigenous/Settler Collaborations." Journal of Arts & Communities vol. 6 (2014), pp. 5-28 and "Decolonizing Disability, Indigeneity, And Poetic Methods: Hanging Out in Australia." Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, vol. 7, no. 2 (2013), pp. 175-193.

Return to Text