In 1887, U.S. Deputy Marshall Dan Maples was shot and killed in Tahlequah, Indian Territory, and the capital of the Cherokee Nation. Despite there being no evidence, the blame fell upon the traditionalist Keetoowah Cherokee Councilman Nede Wade "Ned" Christie. Posses hounded Ned and his family for five years before one blew up his Wauhillau cabin and shot him to death. After Ned's demise in 1892, newspapers around the country printed hundreds of fraudulent stories about Ned and his family—and they still appear today. The fabricated image of Ned as a hulking, merciless desperado has inspired countless western movie characters. No proof exists that Ned murdered Maples, nor that he committed any of the other myriad invented crimes attributed to him and his "gang." Nevertheless, the Cherokee Ned Christie remains an iconic symbol of Wild West violence and Native savagery. 1

The story of Ned Christie illustrates the powerful influence of settler violence and the ongoing process to erase and replace Indigenous histories and peoples. What happened to his cousin Arch Wolfe epitomizes how those with anti-Indian sentiments leveraged ableism and Western medical diagnoses to support their interventions. At the time of Christie's death, newspapermen demonized Ned's teenaged cousin, Arch Wolfe. Arch had been living with Ned but was not present at the murder. Nevertheless, Arch was charged with assault with intent to kill posse members. The only evidence against Arch was a letter written by William Adair, a man whose ex-wife Nancy had married Ned. In that letter, Adair falsely claimed that Arch had tried to kill him and that Ned had amassed a large following of reprobates to assist him in killing lawmen. 2 Eager to punish anyone associated with Ned Christie, in 1893, the "Hanging Judge," Judge Isaac Parker, at Fort Smith Arkansas, sentenced Arch to two years of hard labor for the crime of assault with intent to kill, another eighteen months for the misdemeanor of "retail liquor distributing," and another eighteen months for "introducing spirituous liquor." 3 He was imprisoned almost 1400 miles away from his family and home, at the Kings County Penitentiary in Brooklyn.

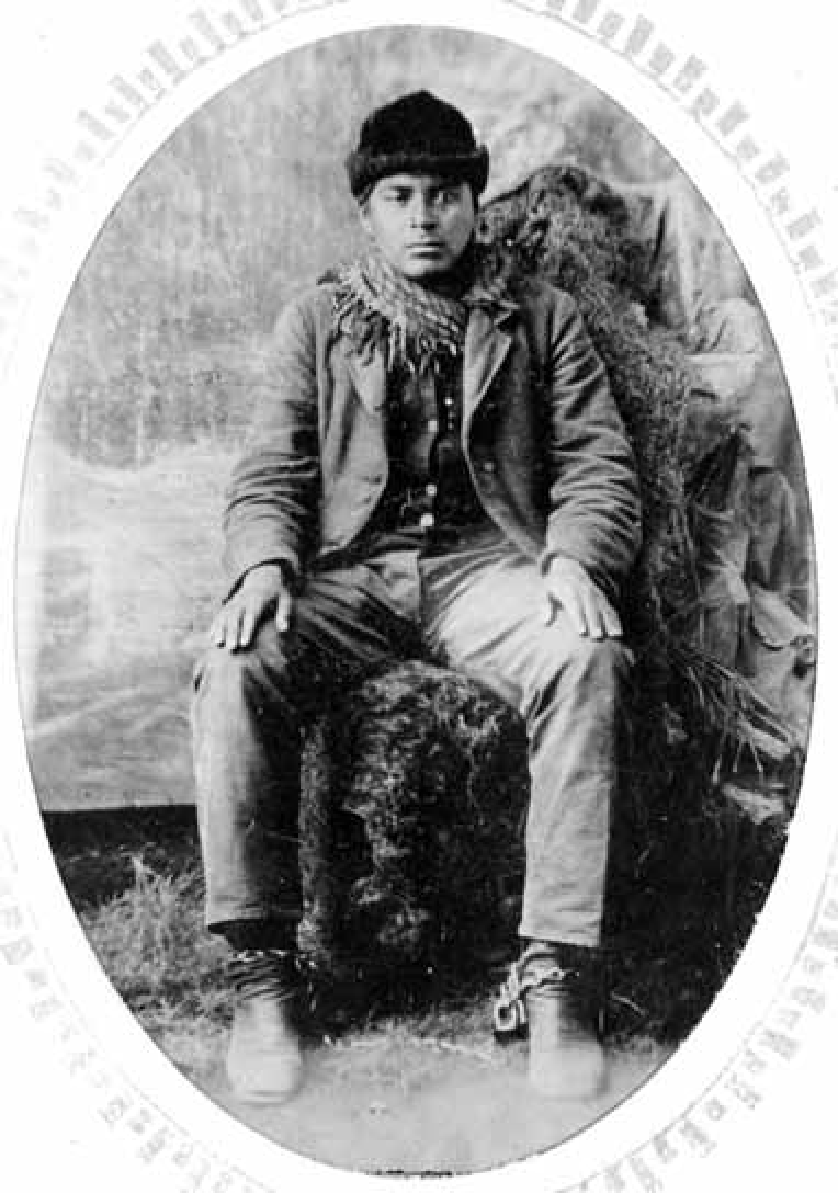

Photo of Arch Wolfe in shackles circa 1893. (Courtesy of the Cherokee National Historical Society, Tahlequah, Oklahoma).

On August 29, 1895, after fifteen months at Kings County Penitentiary, twenty-one-year-old Arch was transferred to the Government's first Hospital for the Insane (later named St. Elizabeths Hospital) in Washington, D.C. 4 The attending physician stated that "prison life" caused Arch to suffer from "acute melancholia." 5 No doubt Arch had become homesick and depressed. He did not speak much English and had no one to speak Cherokee with him. He still reeled from the trauma of losing his role model Ned and had suffered for months in the "Hell on the Border" prison at Fort Smith prior to his trial. 6

What subsequently happened to Arch is pieced together from brief letters from his family. Just one month after admitting him for "melancholia," St. Elizabeths physician Dr. H.W. Godding wrote to Arch's family, claiming that Arch was in "critical condition" and "not likely to recover," with no other descriptors. Alarmed at this news, Arch's family wrote back for more information. 7 They did receive at least one letter from Arch during the next year, because in 1896 they wrote to Godding, asking when he would come home because "last time we heard from him was getting better." 8 Having received no response to that, the family attorney followed up, requesting that Arch be returned home for treatment at the Cherokee Asylum for the Deaf, Dumb, Blind, and Insane, a tribally-run institution established by the Cherokee National Council that opened in March 1877. The Cherokee Asylum was located six miles south of Tahlequah—nearer to Arch's family—and university-trained Cherokee physicians administered the institution. 9 Ned Christie's brother, Senator Jim Christie, sat on the Insane Asylum committee. Cherokee language, culture, and histories connected asylum staff and institutionalized people, distinguishing this asylum from all others at the time. 10

Godding must have somewhat agreed with the family's request, because less than a year after Arch's arrival at St. Elizabeths in 1895, he sent Arch's file to the Department of the Attorney General, requesting that Arch either be returned to jail or to be released to the Cherokee Nation Asylum. The request landed on the desk of President Grover Cleveland who denied the request, stating that, "If this convict is still insane as appears to be the case, he perhaps ought not to be discharged in any event." 11 That statement, "as appears to be the case," suggests that Godding stated in his letter that Arch was "insane."

Godding's and Cleveland's assessments of Arch reflect the notions of the day about mental health. The definition of insanity in 1895 varied depending on who used it. Courts could declare a problem person "insane," while doctors defined the term more broadly to include persons who were depressed, or those who were labeled "idiots" and "deranged." Some declared those with epilepsy or "mutism" that is, not speaking at all or not speaking to anyone besides oneself, to be insane. 12 St. Elizabeths ward notes on Arch from November 1900 to December 1903do not reveal anything medically exceptional about this young Native man who had been confined to an institution far from his tribe and who had experienced significant emotional trauma. The almost-daily log about Arch could be about almost any person experiencing a bout of depression. Throughout 1902, St. Elizabeths observers wrote that Arch slept well, cleaned his area, helped around the hospital, walked outside, and did not talk much. Most days he was "doing nicely" and his condition "remains unchanged." 13

He was, nevertheless, given almost daily doses of strychnine, lapactic pills, castor oil, whiskey, and colocynth, or "Blue Mass," the latter causing consistent vomiting, dehydration, and constipation. Blue mass also had been prescribed for Abraham Lincoln for his "hypochondriasis," a wide-ranging term that included everything from melancholia to constipation. A main component of blue mass was mercury, and it is probable that mercury poisoning accounted for Lincoln's "bizarre behavior," that is, extreme mood swings, tremors, and conversations with himself. 14 Indeed, the ward notes reveal that Arch suffered from excessive vomiting, bloody coughs, cracked lips, and self-discussions.

The archival record suggests that authorities presumed Arch was insane but mostly manageable within institutional confines. Discharge in this context would have been achievable if unlikely, but settler politics foreclosed that option in general and the possibility of transferring Arch to the Cherokee Asylum specifically. President Cleveland likely was aware of the outrageous stories about Ned Christie that by that time appeared weekly in national papers. It would not be politically advantageous for Cleveland to exonerate someone close to the "notorious outlaw." Cleveland certainly did not want Arch back among his people who might allow him to leave the Asylum. Further, by 1896, the Cherokee Nation government—as well as the governments of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muskogee-Creek, and Seminole Nations—was headed for dissolution. In 1893, opportunistic "Sooners" on their land run had filled the Cherokee Outlet in what is now considered northwestern Oklahoma. Although the Curtis Act, which provided for the division of tribally held lands into individual allotments and the sale of "surplus" lands to settlers, would not be passed until 1898, the federal government already had planned to take complete control of the tribe. And that would include the Cherokee Asylum.

Ever-expanding networks of psychiatric institutions also influenced choices and outcomes in Arch's life. At the turn of the century, Congress became convinced of the need for a separate Indian asylum after a survey of forty-three Indian agents stated they observed fifty-five "insane" Indians and fifteen to twenty "idiotic Indians." 15 The commissioner of Indian Affairs voiced approval of an asylum specifically for Indians, although Dr. Godding at St. Elizabeths argued that such a building was unnecessary. After all, he had only five insane Indian patients at St. Elizabeths (one was Arch) and he believed an asylum for "African citizens" more important. 16 Advocates for the Indian Asylum ultimately prevailed and the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians (nicknamed the Hiawatha Asylum by non-Native townspeople) opened in December 1902. Congress and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which oversaw the institution, was eager to fill its locked wards with those individuals whom Indian agents deemed "insane" Indians. 17 Transferring Native people to South Dakota additionally freed up space for additional people to be detained at the federal psychiatric facility, St. Elizabeths, which buttressed settler colonial and ableist aspirations to confine and oversee nonconforming people. Arch, along with several other Native men and women were moved from St. Elizabeths to Canton in January 1903.

In August 1903, Oscar S. Gifford, the Superintendent and Special Disbursing Agent at Canton, provided a summary of the first patients, rationalizing that, "Some of these unfortunate people have no relatives nor friends who are responsible, either legally or morally, for their care or support, and some Indians are quite superstitious regarding insanity and will have nothing to do with an insane relative or friend, except to get rid of them in the quickest and easiest manner possible." He added that, "They were a great burden to their relatives or friends, or to the agency or school officers, as the case might be, or they were neglected altogether." 18

In regard to Arch Wolfe, this claim could not be further from the truth. While this might have been true among some groups, the Cherokees had an Insane Asylum and Arch had many relatives and friends. His family repeatedly wrote letters reflecting their anxiety over information about him. They pleaded for his return to the Cherokee Nation. This brings into stark relief the settler logic that Native people were deficient as caregivers, leveraging ableism to sustain anti-Indian practices, including institutionalization.

There is no daily log of Arch's life at Canton. In 1907, however, a short description of Arch reads: "Arch Wolfe 34 Cherokee 1/03 Union Paranoia (Terminal Stage) Systematized delusions of expansive tendency, incoherent, has parole, causes no trouble, but potentially dangerous." 19 Arch had not been diagnosed as paranoid, delusional, or dangerous at St. Elizabeths; yet, Canton physician, Dr. John F. Turner declared him so.

Asylum medical staff assertions that Arch was "incoherent," was observed "muttering" or "talking quietly" to himself, and that he seemed "very childish in manner and habits" raises multiple possibilities. Arch spoke Cherokee, none of the staff understood him. 20 They read him through a pathological lens because he was Indigenous and detained in an insane asylum. Such was the malleability of diagnostic labels and the power of Western biomedicine and settler institutions. If he spoke Cherokee, then he would definitely be "incoherent" to those who did not understand his language. It also was a convenient way to what Canton scholar Susan Burch describes as "pathologize any Native language use." 21 Defining Arch as "incoherent" also allowed politicians with ties to Oklahoma (that became a state in 1907) to keep him incarcerated. The added assertion that Arch was "potentially dangerous" came from the reality that he was sent to prison years prior on the questionable accusations of assault with intent to kill. He exhibited no signs of violent tendencies while St. Elizabeths and even the Canton description of him across subsequent years includes the statement, "causes no trouble" and "has parole," meaning, he had "parole of grounds." 22

As with most people detained at Canton Asylum, institutionalization was a life sentence. On July 2, 1912, Canton's Dr. Harry Hummer wrote that Arch succumbed to diabetes mellitus and pulmonary tuberculosis. 23 The tuberculosis diagnosis fits a larger pattern; many people held at Canton also died from T.B. 24 The diabetes diagnosis, however, is unlikely. According to Canton records, the ten-acre farm supplied the kitchen with a variety of plant foods, milk and meat. And, records reveal that the only person who had diabetes in 1910 was Arch, which raises the strong possibility that Hummer assigned a false diagnosis. 25 This matches a different pattern: settler authorities imposed pathological labels on Native people as a means of justifying wide-ranging interventions, including confinement and sustained exiles, and rationalizing harmful outcomes. One could argue that everyone incarcerated at the Indian Asylum experienced this practice.

As Pemina Yellow Bird (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara) and other researchers of Canton have argued, it is evident that Indians deemed troublemakers were redefined as "mentally ill" by Indian agents. 26 Almost two decades after Arch's death in 1912, Dr. Samuel Silk, a staff member at St. Elizabeths who inspected Canton in 1929 and 1933, came to the same conclusion about the men, women, and children held in the locked wards, stating that there was no justification to merit keeping many of them imprisoned. He asserted what many descendants already know: that some people were there because they had an argument with a white man, a spouse, or they were deemed troublesome to an Indian agency. 27 Arch Wolfe had been unfairly convicted of assault with intent to kill and whiskey selling and had been sentenced to prison for only five years, yet his medicalized incarceration extended to thirteen more years—his lifetime. No Christie or Wolfe family members have stated that Arch was mentally unwell. It was not until he was unfairly incarcerated that he became depressed and white authorities' pathologizing assessments led to his continued confinement and death at Canton. Arch was, in fact, a political prisoner and his incarceration was an attack on tribal self-determination. He had no right to defend himself and indeed, there are no records to tell us his perspective. And, in spite of Superintendent Gifford's absurd claim about Canton's residents, that, "None of them were wanted anywhere, nor by anybody," Arch's desperate family and attorneys who wanted him home had no power, either.

Settlers' denial of Indigenous self-determination and healing practices rings loudly in this context as well. No member of Congress nor the administrators in charge of St. Elizabeths or Canton considered if tribes had tribal healers (often known as medicine men or women, those revered people who treated physical and mental ailments) who could best address what the agents deemed to be mental illnesses. Ned Christie's maternal grandmother was a healer and he had been counseled by his brother-in-law (also a healer) during the time he was hunted by Fort Smith posses. Both could have tended to Arch. And, had Arch been sent to the Cherokee Asylum he would not have experienced the extreme confinement commonplace in other asylums; the administrators of the Cherokee Asylum did not forcibly detain inmates. Those who were desperate to leave could do so. 28

Arch was not the only Christie associate to be conveniently dispatched after Ned's death. A year after the posse killed Ned, his son James was beaten, stabbed, and almost decapitated. 29 The husband of a cousin was murdered and left on the side of a road. After the death of Ned's widow Nancy and the deaths of her sons, the white man who bought their land bulldozed their graves—bodies and all—into a lake. 30 There are countless examples of how Indians were erased during this time period. Arch's death at Canton is another one of them.

Sadly, Arch ended up spending seventeen years—almost half his life—in insane asylums. He arrived as a homesick and despondent Cherokee who was a victim of racism and political maneuvering. At Canton, Arch and other inmates found themselves prisoners of weaponized Western medicine. Even their families and attorneys were powerless to save them. Those at fault for Arch's forced dislocation from his home, as well as for his and his family's despair, were all white men: spiteful lawmen, newspaper writers with a flair for sensationalism, the unforgiving Judge Isaac Parker, Dr. W.W. Godding who misinformed President Grover Cleveland, the incompetent Superintendent Oscar Gifford and his arrogant predecessor Harry Hummer, and the misguided Bureau of Indian Affairs. They—and many others then and since—leveraged ableism to extend violent settler goals of dismantling, erasing, and replacing Native people, nations, and history.

In 1912, Canton staff buried Arch in the asylum cemetery, a site whose layers are saturated with settler violence and white privilege. For decades, the former grounds of the asylum have functioned as the Hiawatha Municipal Golf Course. The cemetery is situated between the fourth and fifth holes. Families of those who perished at Canton must watch for wayward golf balls when they visit. There are more than 120 people buried at this gravesite. Arch lies in plot #27, between a Tohono O'odham from Sells, Arizona, and a Chippewa from Leech Lake, Minnesota. His location is described as in "Tier Number 4, fourth row from west side, beginning at north and Canton Asylum Cemetery." 31 Much to the dismay of family members, there are no individual grave markers.

Arch Wolf's experiences of medicalized incarcerations make clear that Western biomedical diagnoses reflect specific cultures and values, serve various purposes, and have material consequences. These are realities that community members and scholars in Native American Indigenous Studies and Disability studies have long acknowledged but rarely engage collectively. Placing stories of institutionalized Native people into their actual broader histories—of settler colonialism, weaponized medicine, and denial of self-determination embody meanings that (mostly non-Native) scholars in disability studies typically have not considered. Considering more directly how ableism functions (including the eclipsing power of Western biomedicine over other ways of thinking about and responding to bodyminds) offers American Indian and Indigenous studies scholars additional approaches to critiquing the reach of settler colonialism.

Endnotes

-

See Devon A. Mihesuah, Ned Christie: The Creation of an Outlaw and Cherokee Hero (University of Oklahoma Press, 2018); for information on Arch Wolfe, see pp. 117-138.

Return to Text -

Criminal Defendant Case Files for Tom Wolfe and Arch Wolfe, 1892, jacket no. 479, National Archives, Southwest Region. See also "United States v. Arch Wolfe," indictment 2881, November 9, 1894, Common Law Record Books, 1855-1959, p. 394, WAR16, file unit from Record Group 21: Records of the District Courts of the United States, U.S. District Court for the Fort Smith Division of the Western Division of Arkansas, National Archives, Southwest Region, On the other matter of being charged with attempting to kill Gideon White: "United States v. Arch Wolfe," indictment 2898, November 9, 1893, Common Law Record Books, 1855-1959, p. 395, WAR16, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)-Southwest Region.

Return to Text -

"Criminal Defendant Case File for Arch Wolfe," indictments 3196, 3197, Liquor Jacket no. 479, file unit from Record Group 21: Records of the District Courts of the United States, U.S. District Court for the Fort Smith Division of the Western Division of Arkansas, NARA- Southwest Region.

Return to Text -

Arch Wolfe, Case File #9653, folder 418.4.1: "Records of the Medical Records Branch," Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital, Federal Records, Record Group (RG) 418, NARA-DC.

Return to Text -

"Two Insane federal Prisoners Leave Penitentiary," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 29, 1895, 2.

Return to Text -

Anna Dawes, A United States Prison, 143; Testimony of William M. Cravens, and comments of Judge Isaac Parker, June 3 and 4, 1885, in "Report of the Committee on Indian Affairs," 390; 401.

Return to Text -

Arch Christie to Dr. C.H. –- [indecipherable], n.d. in "Arch Wolfe," Case File, #9653, St. Elizabeths Hospital, RG 418, NARA-DC.

Return to Text -

Young to Godding, January 6, 1896, in "Arch Wolfe," Case File, #9653.

Return to Text -

For a summary article of the Asylum, see Carl T. Steen, "The Home for the Insane, Deaf, Dumb and Blind of the Cherokee Nation," Chronicles of Oklahoma 21 (December 1943): 402-419.

Return to Text -

The physicians also tended to students at the Cherokee Female and Male Seminaries, sophisticated tribal schools that opened in the 1850s, offering physics, chemistry, foreign languages, and literature. Devon Mihesuah, Cultivating the Rosebuds: The Education of Women at the Cherokee Female Seminary, 1851-1909 (Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 1993), idem; Devon Mihesuah, "Out of the Graves of the Polluted Debauches: The Boys of the Cherokee Male Seminary," American Indian Quarterly 15 (Fall 1991): 503-521. https://doi.org/10.2307/1185367

Return to Text -

"One Sentence Commuted; But the President Declines to Intervene in Twelve Cases," New York Times, June 30, 1896; William C. Endicott, Jr. to Dr. W.W. Godding, June 29th, 1896, in "Arch Wolfe," Case File, #9653.

Return to Text -

See for example, Bernard Hart, The Psychology of Insanity (London: Cambridge University Press, 1929), 111. https://doi.org/10.1037/11409-000

Return to Text -

Arch Wolfe, Record Group 418, Case File #9653 in 418.4.1: "Records of the Medical Records Branch," Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital, Federal Records, Washington, D.C.

Return to Text -

Hirschlorn, Norbert, Robert G. Feldman, and Ian Greaves," Abraham Lincoln's Blue Pills: Did Our 16th President Suffer from Mercury Poisoning?" Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 44, no. 3 (Summer 2001): 315-32. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2001.0048

Return to Text -

Untitled List, Box 2, Canton Asylum, CCF 1907-39, Record Group 75, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Return to Text -

Asylum for Insane Indians, U.S. Senate Report No. 567 on S 2042. 55th Cong., 2d sess., February 11, 1898.

Return to Text -

Asylum for Insane Indians, U.S. Senate Report No. 567 on S 2042. 55th Cong., 2d sess., February 11, 1898.

Return to Text -

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1903, 325.

Return to Text -

Untitled list, Box 2, Canton Asylum, CCF 1907-39, RG 75, NARA-DC.

Return to Text -

Arch Wolfe, Case File #9653 in 418.4.1: "Records of the Medical Records Branch," Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital, Federal Records, RG 418, NARA-DC.

Return to Text -

Susan Burch, personal communication, November 30, 2015.

Return to Text -

H.R. Hummer to Commissioner, July 2, 1912, Box 19, Canton Asylum, CCF 1907-39, RG 75, NARA-DC.

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

Bradley Soule and Jennifer Soule, "Death at the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians," South Dakota Journal of Medicine 56, no.1 (January 2003): 17-18.

Return to Text -

Bureau of Indian Affairs: Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, Canton, S.D.: decimal correspondence file, 1914 to 1934; Letters Received from the Commissioner, 1916 to 1930, RG 75, NARA-Kansas City.

Return to Text -

Pemina Yellow Bird, "Wild Indians: Native Perspectives on the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians," http://www.power2u.org/downloads/NativePerspectivesPeminaYellowBird.pdf; Susan Burch, Committed: Remembering Native Kinship in and beyond Institutions (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021); idem, "'Dislocated Histories': The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians," Women, Gender, and Families of Color 2, no. 2 (Fall 2014): 141-162. https://doi.org/10.5406/womgenfamcol.2.2.0141; Carla Joinson, Vanished in Hiawatha: The Story of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016). https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1d4v02q; Scott Riney, "Power and Powerlessness: The People of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians," South Dakota History 27 (1997): 47-8.

Return to Text -

Samuel Silk, Report to Commissioner through Dr. White, October 3, 1933, 9, Folder 4, Box 3600B, H83-1, Canton Asylum, South Dakota State Archives; Records Relating to the Department of the Interior, 1902-1943: records of St. Elizabeths Hospital, RG 418, NARA-DC, 325-7; "Memorandum for the Press," October 15, 1933, PI-163-E-121, HM2003, Box 3, Canton Asylum, CCF 1907-1939, RG 75, NARA-DC.

Return to Text -

Julie Reed, Serving the Nation: Cherokee Sovereignty and Social Welfare, 1800–1907 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016); Carl T. Steen, "The Home for the Insane, Deaf, Dumb and Blind of the Cherokee Nation," Chronicles of Oklahoma 21 (December 1943): 402-419.

Return to Text -

Cherokee Advocate, July 8, 1893; Cherokee Advocate, July 29, 1893; Cherokee Advocate, August 26, 1893; Cherokee Advocate, October 7, 1893.

Return to Text -

Roy Hamilton, descendant of Ned Christie, personal communication. See also Mihesuah, Ned Christie, 115-116.

Return to Text -

Cemetery Ledger, Box 4, Canton Asylum, CCF 1907-39, RG 75, NARA-DC.

Return to Text