The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), and yet their perspectives and experiences have not been incorporated into the vast majority of research, public health plans, or social service provision. This article presents the pandemic experiences of twelve adults with I/DD living in the United States in late spring 2020. Findings include informants' uncertainty about the virus and its impacts, difficulties navigating changes to housing, employment, and schedules, increased feelings of personal responsibility, and exacerbated tensions in professional and personal relationships. I conclude with recommendations for research, policy, and practice that privilege the lived experiences of people with I/DD during times of crisis.

People with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) 1 have experienced particular harms from the COVID-19 pandemic. Examples include increased risk of complications from the virus itself and social and psychological ramifications related to social isolation and loss of services or community (Constantino, et al 2020; FAIR Health, West Health Institute, and Makary, 2020; Turk, et al, 2020). Despite this, there remains a dearth of research that collects and interprets the experiences of people with I/DD themselves. In the years since the beginning of the pandemic, a small number of qualitative studies of people with I/DD's experiences have emerged (e.g., Epstein, et al, 2021; van Holstein, et al, 2023; Carey, Miller, and Finnegan, 2021, Embregts, et al., 2022), but research has largely focused on experiences of informal caregivers (e.g., Willner et al, 2020 in the UK; Wos, Kamecka-Antczak and Szafranski, 2021 in Poland), direct support professionals (e.g., Embregts, 2020 in the Netherlands), and disabled people more broadly (e.g., Fietz, de Mello, and Fonseca, 2020 in Brazil). This body of literature remains particularly sparse in the United States. The results are a poor understanding of people with I/DD's experience of COVID-19 and its consequences. Without this knowledge, it is impossible to create social and political transformations to better respond to the needs and desires of people with I/DD both now and in future crises.

This article contributes a series of semi-structured qualitative interviews conducted with adults with I/DD in the United States about their understanding and experience COVID-19 in the early days of the pandemic. All interviews in this study were conducted in late spring 2020. This was a time of confusion, isolation, and fear as many experienced lockdowns, closures of essential resources, and limited access to information. I captured these emotional and material transformations as informants experienced them in real time, lending a richness and immediacy to these perspectives that is sometimes lost in retrospective data (Neusar, 2014).

Findings include uncertainty and confusion about the virus itself and prevention guidelines, substantial changes to living, working, and social arrangements, increased feelings of personal responsibility, and relational and emotional strain. From these findings I draw several conclusions. First, there is an urgent need to create and disseminate information that is cognitively accessible, meaning it is easily understandable to more people with I/DD. Second, people with I/DD experience a professionalization of their relationships that is inherently unbalanced, where many people they emotionally, socially, and physically rely on are paid in some capacity. As programs and services closed during the pandemic, people with I/DD felt isolated and disengaged. Finally, people with I/DD who have physical care needs or those working in "essential" positions during the pandemic faced increased risk of exposure and illness, contributing to a narrative of disposability. While many of these findings resonate with disabled and nondisabled people alike, the particular vulnerabilities people with I/DD face—such as small, dense social networks, limited employment opportunities, and the professionalization of their relationships—mean that these experiences have profound consequences. Prioritizing the perspectives of people with I/DD in narratives about their lives and their health, rather than relying on proxy perspectives, has relevance beyond COVID-19, yielding crucial knowledge for meaningful and desirable policy and practice that can be applied to future crisis-planning.

I/DD and COVID-19

Academic research published in the last several years reveals startling disparities regarding the impacts of COVID-19 on people with I/DD. Considering risk of the virus itself, evidence suggests people with I/DD are more likely than their nondisabled peers to develop complications and die from COVID-19 (Landes, et al, 2020; ; Gleason, et al, 2021). Contributing factors include higher rates of physiological risks such as respiratory disease, and sociological risks such as living in congregate settings (Landes, et al, 2020; Landes, Stevens, and Turk, 2020; Mark, et al, 2020). Congregate living such as group homes and nursing homes makes social distancing a challenge, as does the need for personal assistance.

The pandemic also exacerbated shortages in both personal protective equipment (PPE) and staff. One study found that in 2020, twenty percent of US nursing homes reported a severe shortage of PPE and some type of staff shortage (McGarry, Grabowski, and Barnett, 2020). ANCOR, a national lobbying organization for community-based providers supporting people with I/DD, noted that the direct support professional shortages worsened during the pandemic, and the profession has not yet recovered. They found that in 2022, eight out of every ten providers had stopped accepting new referrals due to limited staffing, and six out of every ten discontinued services or programs. Those figures represented an 85.3 percent increase in just the first two years of the pandemic. Such changes meant more people with I/DD were institutionalized or hospitalized due to the lack of community-based resources (ANCOR, 2022), which then further exposed people with I/DD to higher risks of infectious disease.

People with I/DD also faced unequal care in the medical system, especially as resources became scarce. In the US, medical triage and rationing plans de-prioritized acutely ill disabled patients along with other vulnerable categories of people such as older adults, making explicit the difficulties marginalized people have had in accessing appropriate healthcare (Johnston and Pollack, 2023). For example, Alabama's Emergency Operations Plan in effect at the beginning of the pandemic stated that mechanical ventilators should not be allocated to people with significant intellectual disabilities based on "expected level of recovery" (8). The plan then contradictorily acknowledged that "the average life expectancy of persons with [intellectual disabilities], now spans to the seventh decade and persons with significant neurological impairments can enjoy productive happy lives" (State of Alabama, rev. 2010, 8). 2 This dissonance—which at the same time acknowledges and undercuts the value of disabled lives—highlights an approach to the pandemic that marked disabled lives as acceptable losses.

Further, people with I/DD regularly experienced discriminatory care, including at the end of life, due to issues such as poor communication, disparities in access, and poor collaboration among support networks and service systems (Alexander, 2020). Increased inappropriate applications of "Do Not Resuscitate" orders in the UK, reports of individuals denied care in the US, and the public discourse around pre-existing conditions and acceptable deaths revealed discriminatory structures that denied people with I/DD equal access to life-saving care (Gulati, et al, 2020; Courtenay and Perera, 2020; Silverman, 2020; Abrams and Abbott, 2020).

In addition, people with I/DD are already vulnerable to social isolation, exclusion, and loneliness (Corbett, 2011), conditions that stay-at-home orders and prevention guidelines amplified (van Holstein, et al, 2023). Willner et. al. (2020) and Alexander (2020) both note that people with I/DD likely felt the mental health ramifications caused by social distancing and isolation more acutely than their nondisabled peers. Alexander further remarks that people who navigate their communities with the support of others (and therefore appear to be ignoring social distancing protocols) may have felt stigmatized, which in turn led to avoiding what few opportunities exist to be in community with others. Multiple studies corroborate these findings, showing people with I/DD reported adverse mental health effects, disruption in daily routines, loss of healthcare services, and feelings of disconnect during the pandemic (Temple, 2022). This study seeks to further nuance and deepen this literature through additional first-person accounts of the early pandemic experience.

Methodology

This research takes up an epistemological perspective informed by critical disability studies. As such, my interpretation of intellectual disability does not rely on discrete diagnostic features, but on complex and fluid social, cultural, physical, and psychological dimensions. This approach exposes systemic ableism by attending to social and political conditions and norms, relying on and privileging lived experiences (Rapley, 2004; Hall, 2019). This approach is particularly salient when considering that people with I/DD have consistently been denied credibility as knowers of themselves and their worlds (e.g. Klausen, 2019; Kalman, Lövgren and Sauer, 2016). In general, the domination of medical and individual models of disability discredits the experiential knowledge of disabled people in Western societies (Wendell, 1996; Monteleone, 2020). Beyond this, many people with I/DD face a particularly acute epistemic invalidation, in which they are often perceived as unable to contribute to discourses about themselves, their bodies, and their lives. The qualitative and inductive approach to this research, which relies solely on the narratives produced by informants with I/DD, resists the persistent and insidious exclusion of people with I/DD as knowers of their own lives and experiences.

To privilege the lived experiences of people with I/DD, I interviewed twelve adults self-identifying as having I/DD living in or around two major cities in the United States (eight in the Southwest and four in the Midwest). Informants ranged between nineteen and fifty-nine years old, with an average age of thirty-four. Five identified as male and seven as female. Ten identified as white, one as Black, and one declined to identify their race or ethnicity. Six informants acted as their own guardians while six were under guardianship arrangements, usually with a parent acting as their guardian. At the time of the interview, five informants lived with their parents and two with siblings. Three lived independently in the community, although one was in the process of moving back in with his parents. One participant lived in a specialized gated community for adults with developmental disabilities, and one lived in a ten-bed group home.

I conducted each interview using an open-ended, semi-structured interview schedule, which provided structure but allowed informants to share freely and guide the discussion. In several cases, a parent or guardian was present for the interview and provided clarifying information with the explicit permission of the participant.

I analyzed the interviews using a general inductive analytical framework (Kahlke, 2014), informed by thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2012) and hermeneutic phenomenology. Under this framework, I explicated not just the factors that mediate informants' interpretations, but my own, which are filtered through my experiences as a white, educated, neurodivergent American woman without an intellectual disability and with long-term professional and personal engagement with communities with I/DD (Laverty, 2003). Using close reading and iterative coding, I developed seven thematic categories: 1) Understanding COVID-19, 2) Prevention and Precaution, 3) Getting Information, 4) Personal Responsibility, 5) Life Transformations, 6) Emotional Impacts, and 7) Relationships. These themes are explained in detail below.

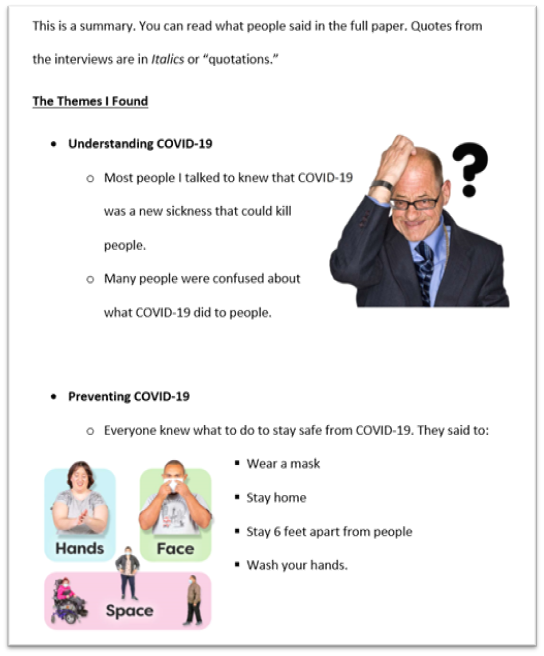

After developing and organizing themes based on this analysis, I created an Easy Read summary of the initial draft, which I sent to all informants for anonymous feedback (see Figure 1). This process, called "member checking," increases credibility and validity (Lincoln and Guba, 1986). At the time of this writing, four informants and two guardians submitted feedback. Those who responded generally affirmed that the study's findings reflected their experiences. I incorporated any requested changes into subsequent revisions. A final Easy Read summary of the study is provided in the appendix

Figure 1. Excerpt from Easy Read Study Summary Sent to Informants

Image Description: Excerpt from Easy Read document. Sans serif font on a white background reads: "This is a summary. You can read what people said in the full paper. Quotes from the interviews are in Italics or "quotations."

A new section has the bolded title: The Themes I found. Text reads:

- Understanding COVID-19

- Most people I talked to knew that COVID-19 was a new sickness that could kill people.

- Many people were confused about what COVID-19 did to people.

Next to this section is an image of a man scratching his head with a question mark next to it. The next section reads:

- Preventing COVID-19

- Everyone knew what to do to stay safe from COVID-19. They

said to:

- Wear a mask

- Stay home

- Stay 6 feet apart from people

- Wash your hands.

- Everyone knew what to do to stay safe from COVID-19. They

said to:

An image with three colorful blocks labeled "hands," "face," and "space" shows people washing their hands, covering their face, and keeping their distance from each other.

Historically, people with I/DD have been objects of exploitation and invalidation in research (McDonald, 2012). As such, I was attentive to ethical implications throughout the process. During IRB approval, I collaborated with my institution's research administrators to develop cognitively accessible and compliant informational sheets and informed consent/assent forms using simplified language and explanatory photographs. During interviews, I reviewed all consent information verbally to ensure autonomy and informed participation.

One particular area of consideration was the power dynamic between myself and informants. I had pre-existing relationships with ten of the twelve informants. As such, I was careful to reiterate the optionality of participation and that non-participation or withdrawal had no impact on any pre-existing relationship. Regardless of my attention, these pre-existing relationships likely affected the informants in this study. Literature on qualitative interviews with informants with pre-existing relationships finds that these relationships likely increase rapport and trust but lead to additional ethical concerns about the exploitation of that trust (Brewis, 2014). Giving informants an opportunity to review findings alleviates some potential for the exploitation of personal relationships Brewis and others describe. I cannot know for certain what impact my previous friendships made in the interviews, beyond the fact that these relationships certainly circumvented problems with gatekeeping that often inhibits research with people with I/DD.

"I Know It's Making People Very Sick": Understanding COVID-19

Philip, a forty-three-year-old man living in the Southwest, responded with the above quote when asked what he knew about COVID-19. Like many of the informants in this study, he knew COVID-19 was new, and he knew it could be deadly, but when it came to naming symptoms, he was less confident. He asked me during the interview, "It could be a guy that has the sickness or it could be a girl?" unsure if all genders were equally affected by COVID-19. Barbara, reading off a sheet where she had written notes about COVID-19 to prepare for the interview, noted that it was similar to colds and flus, that an infected person could be symptomless, and that it could be transmitted to animals. When asked what happened when a person contracted COVID-19, however, she responded,

I'm honestly not entirely sure. The only thing I know as I mentioned before is that you can either appear to have cold or flu symptoms followed by fever or you can be symptomless and then randomly go into much more serious conditions, but I forget what those conditions are.

This understanding of COVID-19 as both significant and difficult to describe was a common thread throughout interviews, just as it was for many without I/DD in spring 2020. Some avoided mentioning symptoms at all, instead opting to describe the virus in terms of management practices such as quarantine. While cough and fever were often cited as common symptoms, informants mentioned many other symptoms such as gastrointestinal distress, sneezing, and headache. Half of the informants emphasized the deadly nature of COVID-19, although they sometimes conflated it with other causes of death and illness. Amanda, for instance, discussed deaths from COVID-19 interchangeably with the deaths that often occurred at the assisted living facility where she worked. Philip connected the causes of COVID-19 to the summer heat in the Southwest. Tom variably related it to cancers caused by what he considered irresponsible behaviors, dementia, and ALS, the latter of which he spoke about fearfully.

Just under half of informants also acknowledged the historical significance of COVID-19. Both Robert and Jeremy brought up previous pandemics they learned about since first hearing of COVID-19. When asked to describe COVID-19, Robert spontaneously mentioned the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, implying the COVID-19 pandemic existed for similar reasons:

Way before my mom and I were born that people had the flu disaster, that people have a hard time recovering from flus and stuff like that, you know, when they are coughing and sneezing all the time, and their bodies won't be able to adjust to the cold.

These connections, along with acknowledgements of COVID-19's newness reveal an appreciation for the singularity of the virus and its impact.

"Just Be Safe and Sound": Prevention and Precaution

The rules of prevention—wearing masks, washing hands, using hand sanitizer, limiting travel, and staying six feet apart—featured largely in both descriptions of COVID-19 itself and ways to stay healthy. All informants had a clear understanding of these preventative measures, although some, like nineteen-year-old Dana, expressed confusion as to why some rules existed. She said she understood why she couldn't attend school or activities, for example, but not why she couldn't visit her relatives beyond those in her household. She shared the answers she received from the trusted adults in her life were not always satisfactory, leading to frustration.

In addition to preventative measures, five informants also mentioned general hygiene and wellness activities as important for staying healthy during the pandemic. Ellen stated she "eat[s] healthy food" and exercised regularly, resulting in "never [getting] sick in my life." Tom suggested that running, keeping clean, and regularly brushing his teeth made him less vulnerable to COVID-19. Barbara comingled COVID-19 prevention with other wellness practices, saying the steps to keeping safe include hygiene, sleep, good nutrition, taking medications, keeping the house clean, and social distancing.

There were two instances where this conflation between the COVID-19 prevention and general wellness activities yielded potentially problematic outcomes. Tom shared that he doesn't "need to wear a mask because I'm always, I always keep myself clean…because I don't have to because I'm not the guy usually catches illnesses." By equating his general cleanliness and good health with immunity to COVID-19, he could endanger himself or others by not following prevention protocols.

Conversely, Shelley conflated dirtiness with illness, leading to increased anxiety in her home. She feared that getting dirty in any way may expose her to risk of infection, sharing,

Now, now I'm a germ freak and I want my whole, you know, after this I was like, "Oh my gosh, and I'm wearing dirty slippers." And I'm like, "Ew, I shouldn't be doing that, my feet are going to get infected and I might catch something."

Because Shelley was not certain what will and will not spread the virus, everything was suspect. She explicitly ties these anxieties to COVID-19, saying, "Never felt that way before this whole virus came about."

In two-thirds of the interviews, informants gave particular consideration to masks as a means of prevention. Many informants liked wearing masks. Jeremy and Robert, for instance, both felt safer when they and those around them wore them. Rachel mentioned the mask made her feel like she was dressing up "like some doctor" for Halloween. Tom also felt like masks were like costumes, though mentioned people may be fearful around them, stating, "the idea of wearing masks is kind of uncomfortable and sometimes it makes you—people think you're going to do something. They may think you're scary, that you're going to beat them up or you're going to rob."

Melissa, a forty-one-year-old woman from the Southwest who needed to wear a mask for her job at a local grocery store, noted that the masks she had access to did not accommodate her disability:

But I'm having a hard time because, here's my thing—the smallness of my head and then and then I wear hearing aids. And so, it's, like, how can you keep the mask on?! And it like…yeah. It's just—I'm having a real tough time with the masks…and the first time I went and put it on, then my hearing aids, you know, were like, popping off, and I'm like, I can't have this. I'm like—and I can't not wear my hearing aids; I need to be able to hear. So yeah, I—yeah, the masks are just very…very hard [chuckles]. It's very tough.

She goes on to explain adjusting her mask using a shoelace, but her frustration at the lack of thought that went into designing a mask for someone with hearing aids was clear.

"I Just Need to Be Shown What To Do": Getting Information

Informants sourced information about COVID-19 from a range of sources, including family members, television news, social media to smart devices. Almost all informants actively sought out information about the virus, even when the experience was bewildering or disheartening. Melissa, however, mentioned specifically avoiding the news and instead getting information from her parents because, "I'm not used to hearing about the death, about hearing about what's on the news, you know."

Several informants talked about the inaccessibility of information. Amanda, for instance, suggested that prevention guidelines such as not touching her face and hair would have been easier to understand if someone had shown her first. She said, "Technically that is harder for someone like me…. But if somebody shows me what to do and all that kind of thing, I would do it. But I just need to be shown what to do."

Barbara expressed feelings of confusion, which she attributed in part to her disability, as contributing to anxiety early on in the pandemic. She said,

I think earlier on, back when I didn't know as much of what was going on, I was a lot more anxious, I also think that the fact that it's more difficult for adults with disabilities to process those kinds of things or to understand them, can also lead to greater fear for both them and their families. Because you can be very scared and not understand or know how to explain this to a child or an adult who might not have capabilities to understand what's happening anymore. And I think that can be a very difficult situation.

Later in the interview, she suggested specific resources designed for adults with I/DD would mitigate that anxiety:

I think there should be a lot more available online resources that provide information in a number of different ways and that they're thoroughly broken down into different steps and the situation in parts and that anything that may be confusing is not dumbed down, but explained in a way that would make sense for adults with disabilities.

While several cognitively accessible resources exist, largely created within I/DD communities themselves (e.g. GMSA, 2020), no one mentioned having encountered them. The lack of access to understandable information, in many cases, led to increased anxiety, confusion, or reliance on others for explanations.

Informants also talked about misinformation and trust in the media. Dana dismissed misinformation out of hand, saying, "people were making a protest over the coronavirus and saying that it was fake and it was a big hoax, but it's not. It's real." Others, like Melissa, were more uncertain. "But I'm gullible," she said after sharing a story of what she interpreted as a dubious claim about COVID-19 from a coworker, "I can believe anything." She took the claim to her mother, who helped her research the answer. Jeremy, Tom, and Barbara also grappled with misinformation discovered on social media with varying degrees of skepticism. The unchecked spread of misinformation online posed a significant challenge. Further, as mentioned above, the continually shifting standards and guidelines created additional confusion, especially if it was not disseminated accessibly.

"I Think I'm the One that Takes It More Seriously": Personal Responsibility

Informants often spoke about increased feelings of responsibility for themselves and others in the pandemic era. Several, like Tom, suggested that some people became ill because they were acting irresponsibly. Others talked about their personal responsibility to keep themselves and those around them safe. John expressed his frustration toward those who refused to follow protocols, stating,

Some people like, wear a mask, some people like don't, some people like more serious than others, but I like, I want this to be done and I don't know that much about the coronavirus, I just know that it's serious…. I think I'm the one that takes it more seriously.

Shelley also spoke about a newfound solemnity. She identified herself as an avid performer, but said she no longer felt comfortable dancing, even by herself in her room for fun, saying, "I don't think this is a big party celebration thing of the pandemic. So, I don't do that. I just take it seriously and I don't dance."

Several informants shared stories where they were forced to make difficult choices in order to protect themselves. Ellen left her employment because she felt unsafe. Barbara and Jeremy were both forced into a position to deny necessary services due to unsafe practices. Barbara withdrew from her day program rather than risk exposure. Jeremy asked his nurse to not return to his home because she refused to wear a mask, forcing him to manage his medication without assistance. When asked how he came to that decision, he said simply, "I like to keep myself safe and [my girlfriend] safe."

"It Made 2020 My Worst Year": Life Transformations

Informants, like Robert in the above quote, characterized spring 2020 as a time of unwanted change, from derailed plans to program cancellations to job loss. Several informants experienced changes to their housing due to the pandemic. Both Rachel and Robert left independent living arrangements to move back in with their parents after losing employment. Tom had to postpone his plans to move out of his parents' house, as he had to put his search for competitive employment on hold. He expressed his frustration, saying, "I am impulsive a little bit to get out of the house and start my own life and I'm afraid that that will never happen. I've been wanting to move out starting from last January."

Perhaps the most dramatic change in living arrangements occurred for Shelley. At forty-five, Shelley was by far the youngest person living in her ten-bed group home. Because her roommates, all of whom were over seventy, were at high-risk for COVID-19, her household locked down early in the pandemic. Shelley experienced acute isolation. She expressed that she got frustrated from

just the fact that we have to stay home all the time and nothing changes with that. Like every time I hear the word stay home, I'm like, Oh again, we have to still be doing the same thing. Nothing is changing. Nothing's good.

Changes to or loss of employment or day services was another common experience among informants. Prior to the pandemic one participant was not working, four attended day programs or sheltered workshops, six worked in the community, and one was attending job trials through school. All but John, Melissa, and Amanda were not working or attending programs at the time of their interview. The experience of losing employment, whether in the community or in a segregated workplace, was difficult for many informants. "It feels kind of sad," Rachel commented after sharing that she was no longer working. She expressed anxiety over the uncertainty of when she might return to work, saying that she was not worried about contracting the virus, but "I'm just worried about…about my jobs." Several, like Ellen, expressed missing the social interactions they had with coworkers, while others like Philip were concerned about missing paychecks. Robert, who was put on furlough from his position with a janitorial supply company, shared his financial concerns, noting, "I had to file for unemployment…and I've got to take some responsibility of my unemployment situation." At the time of his interview, he was struggling to navigate unemployment benefits, which he had yet to receive despite meeting eligibility criteria.

John, Melissa, and Amanda all retained their employment during the pandemic, as each was dubbed an "essential worker." John and Melissa both worked at grocery stores, while Amanda did food service at an assisted living facility. John expressed that he was grateful to still be working, in part

because I can get out of the house, like I still have money and that's the only time…sometimes I see my friends always at work in the break room. That's the only time to talk to people [inaudible] at my break room or in, on Zoom, or um, phone.

Melissa, while expressing some frustrations with customers who refused to follow safety protocols and management that did not provide enough information, enjoyed the recognition that came with being an essential worker. When asked if she was proud of the work she was doing, she said,

You know…there are…two other coworkers that are not working right now at this time, because of the virus. And I wished that I was one of those too. And then, when I was hearing, you know that they're congratulating all the essential workers and that. And then I was like, "Okay, it's not so bad after all." Okay, well, we are getting recognized. And I wasn't sure if the world was going to recognize us because, you know, I've been doing okay and we're just grocery people. You know, we're just the ones that helped keep you fed. And then, I, you know, there's the doctors and the nurses but they get more credit. But…now I'm—yeah, now I'm quite okay. I like the title—the title of being an "essential worker" or "hero." [laughs] Like I say I wasn't at first, but then I'm like well, okay.

Amanda, however, had a distinctly negative experience with her continued work. Her role in food service transformed under new pandemic protocols. She said,

I worked with senior living, independent and assisted living, and they are not immune. They've been immune to most sicknesses but not the current one, but they are a little bit more sensitive to everything. It's not just to look good or whatever. It's involving sicknesses and all of the above. They're really, really fragile about that. Yeah. And yet with all this going around, there have been four people at my job that got hit with it.

Whereas she previously interacted with many of the residents, a job she enjoyed because of its social element, she was now responsible for boxing up food to deliver. She expressed frustration at her sudden lack of social interaction at work, asserting, "It's so not fun anymore." Additionally, because of her increased exposure risk due to the nature of her workplace, her routine and time with family also changed. She told me,

They don't want to be close to me if I don't take a shower or wash my hands or anything, which I get, but I just, but every day when it comes to going to work. Every single five days, it just gets annoying.

The ripples of impact due to essential work touched not only the work itself, but schedules, structures, and relationships.

Nearly all informants talked about increased isolation caused by program and activity cancellations and stay-at-home orders. While some services and programs shifted online with varying degrees of success, the sudden and often dramatic shrinking of informants' social world created anxiety, loneliness, and frustration. John shared that when things began closing and being cancelled, he realized the seriousness of COVID-19. Ellen said simply, "all of 'em are cancelled," when asked about how her schedule has changed since the pandemic begun. Tom was perturbed not only by cancellations that hit close to home, but of national or international sporting and entertainment events that he looked forward to. He said, "And when I found out very important events being canceled, this really made me really scared and I'm well angry too."

For many, these closures led to a feeling of being trapped. Amanda and Dana both referred to quarantine as a type of imprisonment, with Dana remarking she was "desperate" to be away from her house. For others, the emptying of their calendars resulted in large chunks of unstructured time. Jeremy, who previously attended an arts-based program five days a week, suddenly found himself staying up most of the night, commenting, "Uh, I mean, I don't really feel, to me, I don't really feel the need to sleep during the night. I don't have anywhere to be." Barbara remarked that her daily life is "a lot more boring," now, and shared a list of self-improvement projects she assigned herself to create structure. Dana described her daily schedule only in terms of screen time and breaks until her next screen time. Tom became visibly upset when he couldn't remember his daily schedule at his day program before quarantine. When asked, he replied, "I don't remember. The coronavirus has also [done] another thing. Erased our memories."

"I Can't Bear to Be Around this Stupid Sickness Anymore": Emotional Impacts

Informants expressed anxiety, frustration, sadness, and uncertainty, as well as fear of the illness, isolation, and harm coming to loved ones. Barbara mentioned that at the beginning of the pandemic she was "pretty much afraid to leave the house," an anxiety she only alleviated by educating herself on illness prevention with her parents. Shelley expressed that she cries more now during the pandemic because "my body and my emotions, like I said, just go to extremes."

As discussed above, confusion over what the pandemic is, how long prevention protocols will be in place, and other related factors contributed significantly to anxiety felt by informants. Without a clear picture of what the future held—or even why things like food shortages and cancellations were occurring—uncertainty abounded. For some, the anxiety of the pandemic manifested as anger or frustration. As Tom said, "I've been getting a lot of pissed off lately and I just think, 'Oh my goodness, does this mean to stand forever?'" Dana, Shelley, and Amanda expressed similar feelings, remarking they were "annoyed" or "frustrated" with the current state of their worlds. Importantly, Shelley remarked on her frustration not as a rational response to unprecedented times, but as a "behavior" in need of management. She mentioned that she had "anger issues" due to autism; if she "behave[s] well" during the pandemic, she told me, her father will give her an award. For others, like John and Robert, that uncertainty manifested as sadness. John, for example, began crying during our interview, asking when the COVID-19 pandemic would come to an end.

"I Think People Are Just Very Tired of Staying Home and Not Being, Like, Sociable": Relationships

The pandemic deeply affected informants' relationships with others. From severed connections with friends and family to shifting relationships with in-home staff to widely varying experiences with digital spaces, disconnection formed a substantial theme among all informants.

For about one-third, an abrupt lack of physical contact and nonverbal expressions of affection with others became one of the most difficult aspects of COVID-19 protocols. Melissa, who lived alone and worried about being misinterpreted when communicating via text message or telephone, said one thing she struggled with is not being able to, "see my friends and be able to hug people—I'm a hugger—and that's a real—I mean, that's a real killjoy because of this coronavirus, it's really a killjoy. So a hug. The hugging part." John, Shelley, and Philip also referenced hugging as an important aspect of their social lives that they no longer have access to. Shelley confessed to crying when her mother visited at a six-foot distance because "we can't hug each other, anything."

When digital communication was possible, it was often not fulfilling. Whereas some informants, like Ellen, didn't have communities that transitioned online at all, others like Shelley did not have the support or technical resources to participate fully. Shelley, who is blind and who at the time of the interview only had access to a cell phone without smart capabilities, explained her disappointment in struggling to participate in online group events. She felt a resistance from others to offer her assistance to participate in online activities, saying,

I just felt like, okay, well that nobody cares to do it. You know? I was like, okay, nobody cares to do this with me. What am I trying to do? You know? That's what I felt like…I just felt like in general nobody cared about doing it and it just felt all distant and ugh, it felt horrible.

Access to technology bore critically on how connected informants felt during the pandemic. Disabled people generally and people with I/DD specifically are less likely to have access to the internet or internet-enabled devices than their nondisabled peers, a problem compounded by closures of libraries and other sites of public access in 2020 (Chadwick, Wesson, and Fullwood, 2013). Human support to use that technology was also important for informants' online participation. Rachel, for example, said her social activities were "coming great on the computer," in part because "mom knows all about [setting it up]." If Rachel had continued to live independently rather than move back with her parents it's possible she would not have had the same access to these programs. Her parent reaffirmed this point when presented with preliminary findings from this study, a finding supported by other research on technology access for people with I/DD during the pandemic (McCausland, McCarron, and McCallion, 2022).

Several informants also alluded to an imbalance in the effort placed in communication. In just under half the interviews, informants shared that they felt they were the ones responsible for reaching out to others. Shelley, who prior to the pandemic enjoyed making phone calls with friends and family, said it now felt like a "job." Melissa worried that she would be perceived as a burden if she reached out to connect with more people during the pandemic, even though she would like to speak to more people than she currently was. She said,

I'd kinda like to talk to more people, but I do understand that, you know, they…they have…. I do understand that they work and they have other lives. You know, they have their own life that they live also, and, I, you know, I can't control that, you know? And I understand, you know? It's…[pause] it's what it is, you know [chuckles]? But um…[pause] yeah, I never know, you know, day to—day to day, you know, who is doing what or, you know.

The majority of informants felt a loss in quality of communication and connections, whether limited by technological access or attitudinal barriers.

For informants who relied on direct care and support in their day-to-day lives, those relationships came to bear a special importance. Barbara, for example, felt her staff assisted in ensuring her home was a safe haven from illness. Jeremy, on the other hand, reported an increased strain in his relationships with staff who entered his home. As mentioned above, he asked his nurse to not return when she did not wear a mask. He revealed his fears about exposure from staff:

Jeremy: I feel unsafe when somebody comes into my house and doesn't have the mask.

Becca: Mm. And has that happened a lot other than I know your nurse, you mentioned?

Jeremy: Um, some, uh, my DSP [Direct Support Provider], my, uh, person that comes here, my, my staff, uh, uh, he doesn't wear a mask, but, uh, he does practice, uh, healthy things like washing hands, coughing into your hand.

For someone who relied on direct care in its many forms, social distancing was not a possibility. When that care comes from professionals, many of whom travel between clients' homes throughout the day, people like Jeremy risk illness simply because they rely on support.

Finally, in terms of interconnections, several informants including Robert, Philip, Melissa, and Amanda expressed feeling distraught over both acquaintances and strangers more seriously affected by the pandemic. Philip began working with a friend to get food donations from local restaurants because "people right now do not have money to go to the grocery store." Such thoughts and actions directly resist ableist assumptions of people with I/DD as only passive recipients of care or victims of circumstance.

Conclusions

While the experiences of the pandemic varied widely, informants shared a number of similar experiences and responses. These included confusion around the virus and its effects, power imbalances in relationships, and critical transformations in living and working arrangements.

Mirroring uncertainties that many others felt in an era of misinformation and media saturation, informants reported difficulties knowing where to learn about the pandemic, how to determine if information was reliable, and whom to reach out to in moments of confusion. Uncertainty characterized much of national and global discourses about COVID-19 in spring 2020 (Koffman, et al, 2020; Chater, 2020). However, as previous research suggests, people with I/DD faced additional difficulties in accessing meaningful information about COVID-19 and often found reporting on the subject confusing (van Holstein et al, 2023).

While research suggests appropriate and accessible healthcare communications improve health outcomes (Courtenay and Perera, 2020; CDC, 2020), guidelines for how to achieve these are often vague and nonspecific. For example, the CDC guidelines on "Communicating with and About People with Disabilities," last reviewed in February 2022, focuses entirely on policing the language of disability (it advocates for person-first language, despite wide variability in preferred terms among various communities). There is no mention of understandability, simplified language, or augmenting communications with images or videos. Informants in this study recommended a number of strategies to help improve communications. Amanda for example, advocated for having someone model preventative behaviors, and Barbara asked for information to be broken down and simplified. Van Holstein et. al. (2023) similarly found lack of access to accessible information about the pandemic to be a prominent theme when interviewing people with I/DD in Melbourne, Australia, noting "self-advocates had to extract essential information from media and government messaging that was not tailored to their needs," often relying on people in their personal networks to translate (533). Embregts and colleagues (2022), when assessing the experiences of people with I/DD in the Netherlands, also conclude with a call for more accessible information. Where cognitively accessible information about COVID-19 has been produced, it has most often been by self-advocacy groups, such as the Green Mountain Self-Advocates' "A Self Advocate's Guide to COVID-19" (GMSA, 2020). The dearth of accessible information on COVID-19, problems disseminating existing information, and reliance on others to explain information lead to continued disparities in access to information, which in turn creates anxiety, confusion, and unnecessary risk.

The second key shared experience among informants concerns social connections and relationships. Gill (2015) writes that people with I/DD experience more professional regulation over their lives than nearly any other non-institutionalized or incarcerated group. From specialized and segregated education to employment services, social services to caregiving and living arrangements, the lives of people with I/DD are often tightly regimented and controlled. With the COVID-19 pandemic, however, that structure dissolved almost entirely for many, leaving them both isolated and unmoored. Relationships many informants relied on faded away as structured and professional encounters dwindled. How informants discussed communication in the pandemic era also provides insight into this unbalanced relational dynamic. Many informants shared that they were consistently the ones initiating communication with friends outside of their households, a finding that resonates with previous research on the characteristics of social networks of people with I/DD (van Asself-Goverts, Embregts, and Hendriks, 2013). Melissa felt burdensome when initiating communication, worried she was bothering people by seeking a relationship. This finding is salient here in that it reveals the consequences of social networks for people with I/DD, which previous research shows are often small and contingent on professional services (Forrester-Jones, et al, 2006). When professional services cease, the bidirectional communication may also end, resulting in loneliness and isolation.

Additionally, informants discussed growing power imbalances between themselves and their staff, such as Jeremy's experience with two staff members who refused to wear masks in his home. He eventually asked his nurse to leave, while his direct support professional remained at the time of our interview. Paradoxically, Jeremy had to compromise his health by losing support to take his medication in order to protect his health from COVID-19. This anecdote brings into focus two interconnected issues: the impossibility of social distancing for many people who rely on professional or informal support and the difficulties in managing risk for direct support professionals. While in Jeremy's case he was able to dismiss his nurse and take his medications independently, many others rely on formal and informal caregiving and cannot reject it even if it puts them at risk (Fietz, de Mello, and Fonseca, 2020). That danger is exacerbated by the risks borne by direct support professionals themselves, who are overwhelmingly women and people of color, whose low wages often necessitate moving through many people's homes in a single day, and whom state and federal plans have consistently deprioritized for personal protective equipment (Kinder, 2020). The ostensible acceptability of these risks contributes to a narrative of disabled and marginalized lives as disposable. A focus group conducted with people with I/DD by Epstein and colleagues (2021) found similar themes of risk and disposability, with one participant remarking, "Outta this pandemic, I hope we move away from institution, shelter workshops, group homes.[…] It's like throwing somebody in the trash, disposable. It exposes our society" (6).

Informants' experiences with risk and "essential work" also gesture toward social conceptions of disposability and I/DD. Employment opportunities for people with I/DD have long been critiqued for being limited to socially undesirable, low-wage positions (Shapiro, 1994; Kumin & Schoenbrodt, 2016). These positions are sometimes known as "the Three Fs": food (food service or grocery), flowers (landscaping), and filth (janitorial). Of the six informants working outside of segregated workshops or day programs prior to the pandemic (and Dana, who was attending job trials through school), all worked in positions that align with the 3Fs. Some, like Ellen, chose to stop working because of the risk to her health, and others, like Rachel and Robert, lost their positions at least for the duration of the pandemic. The three who continued working were all in positions now considered essential (Amanda in food service at an assisted living facility, and Melissa and John in grocery stores). With the abrupt reclassification to "essential work," workers with I/DD were suddenly confronted with unprecedented recognition of their labor, as Melissa acknowledges and appreciates, entangled with an increased demand for risk to their health and wellbeing. There is a need for further scholarship examining these narratives of disposability and their consequences on the lives of people with I/DD and other marginalized groups.

There were several limitations in this study. While informants varied widely in terms of living arrangement, age, and guardianship status, they shared a few key similarities. First, all informants in this study communicated verbally. The inclusion of informants who are non-speaking could substantially enrich this space, as this group has long been excluded from qualitative research (Teachman, Gibson and Mistry, 2014). Additionally, ten of twelve informants self-identified as white. Further research should prioritize capturing the experiences of non-white people with I/DD, attending to the ways in which the experience of disability and race are deeply entangled in the United States, including in the experience of healthcare (Blick, et al, 2015). Limitations in recruitment, obtaining consent, and conducting interviews remotely due to the time period in which this research took place also created barriers to diversifying this set of informants. Because of stay-at-home orders and COVID-19 prevention protocols, participation required access to an internet-enabled devices. This means people from lower socioeconomic statuses or in living arrangements that restrict their access to the internet were also underrepresented. Further, all informants lived in urban or suburban areas. Capturing exurban and rural perspectives could further nuance the findings here relating to isolation, service provision, and access to technology and information. Finally, at the time of interviews, no participant had been diagnosed with or treated for COVID-19. Retrospective work will doubtless be necessary to understand how people with I/DD experienced medical care during this time. Rawlings and Beail (2023) also argue that people with I/DD experiencing Long COVID are a significantly understudied population. These additional perspectives can further augment recommendations in order to avoid further marginalize already marginalized members of the I/DD community.

This research provides new insights for responding to the needs, desires, and experiences of people with I/DD in the pandemic era, which can be applied to future crisis-planning. While many of these experiences resonate with those of nondisabled people, barriers to accessible information, support, and community produced and exacerbated issues that demand more explicit consideration. Institutionally, service delivery providers should address the loss of structure and relationships when considering program cancellations and closures. Public health professionals must consider cognitive accessibility and understandability when designing messaging for the public. Narratives of emotional tolls, feelings of personal responsibility, and isolation testify to the importance of collecting and privileging the perspectives of people with I/DD about their health, wellbeing, and daily lives. Such knowledge is crucial for building meaningful policy and practice that resists and rejects narratives of disposability, instead building crisis plans that value all lives.

References

- Abrams, T. & Abbott, D. (2020). Disability, deadly discourse, and collectivity amid coronavirus (COVID-19). Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 22(1), 168-174. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.732

- Alexander, R. (2020). Guidance for the treatment and management of covid-19 among people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(3), 256–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12352

- ANCOR. (2022). The state of america's direct support workforce crisis 2022. ANCOR. https://www.ancor.org/resources/the-state-of-americas-direct-support-workforce-crisis-2022/

- Blick, R., Franklin, M., Ellsworth, D., Havercamp, S., Kornblau, B. (2015). The double burden: Health disparities among people of color living with disabilities. Ohio Disability and Health Program. https://nisonger.osu.edu/sites/default/files/u4/the_double_burden_health_disparities_among_people_of_color_living_with_disabilities.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012) Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in psychology vol. 2: Research designs. (pp. 57–71). APA Books. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Brewis, J. (2014). The ethics of researching friends: On convenience sampling in qualitative management and organizational studies. British Journal of Management, 25(4), 849-862. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12064

- Carey, G., Miller, B., and Finnegan, L. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on college students with intellectual disability. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 55(3), 271-281. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-211162

- Centers for Disease Control. (rev. 2022, February 1). Communicating with and about people with disabilities. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/materials/factsheets/fs-communicating-with-people.html

- Chadwick, D., Wesson, C. and Fullwood, C. (2013). Internet access by people with intellectual disabilities: Inequalities and opportunities. Future Internet, 5(3), 376-397. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi5030376

- Chater, N. (2020). Facing up to the uncertainties of COVID-19. Nature Human Behavior, 4, 439. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0865-2

- Constantino, J., Sahin, M., Piven, J., Rodgers, R., & Tschida, J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Clinical and scientific priorities. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(11), 1091-1093. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060780

- Corbett, A. (2011). Silk purses and sows' ears: the social and clinical exclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. Psychodynamic Practice, 17(3), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753634.2011.587606

- Courtenay, K., & Perera, B. (2020). COVID-19 and people with intellectual disability: Impacts of a pandemic. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.45

- Embregts, P. (2020). Experiences and needs of direct support staff working with people with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic: A thematic analysis. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12812

- Embregts, P., van den Bogaard, K., Frielink, N., Voermans, M., Thalen, M., and Jahoda, A. (2022). A thematic analysis into the experiences of people with a mild intellectual disability during the COVID-19 lockdown period. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 68(4), 578-582. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2020.1827214

- Epstein, S., Campanile, J., Cerilli, C., Gajwani, P., Varadaraj, V., and Swenor, B. (2021). New obstacles and widening gaps: A qualitative study of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. adults with disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 14(3), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101103

- FAIR Health, West Health Institute, & Makary, M. (2020). Risk factors for COVID-19 mortality among privately insured patients: A claims data analysis [White paper]. FAIR Health. https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Risk%20Factors%20for%20COVID-19%20Mortality%20among%20Privately%20Insured%20Patients%20-%20A%20Claims%20Data%20Analysis%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

- Fietz, H., de Mello, A.G. & Fonseca, C. (2020). Intimate connections and singular embodiments: Disability in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Somatosphere. https://somatosphere.com/2020/intimate-connections-singular-embodiments.html/

- Forrester-Jones, R., Carpenter, J., Coolen-Schrijner, P., Cambridge, P., Tate, A., Beecham, J., Hallam, A., Knapp, M. & Wooff, D. (2006). The social networks of people with intellectual disability living in the community 12 years after resettlement from long-stay hospitals. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(4), 285-295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00263.x

- Gill, M. (2015). Already doing It: Intellectual disability and sexual agency. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816682973.001.0001

- Gleason, J., Ross, W., Fossi, A., Blonsky, H., Tobias, J., & Stephens, M. (2021). The devastating impact of Covid-19 on individuals with intellectual disabilities in the United States [Commentary]. New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst.

- Green Mountain Self Advocates. (2020). A self-advocate's guide to COVID-19. https://gmsavt.org/resources/a-self-advocates-guide-to-covid-19

- Gulati, G., Fistein, E., Dunne, C., Kelly, B., Murphy, V. (2020). People with intellectual disabilities and the COVID-19 pandemic. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(2), 158-159. . https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.66

- Hall, M. (2019). Critical disability theory. In Zalta, E. (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/disability-critical/

- Johnston, K. and Pollack, H. (2023). COVID-19 reveals longstanding health inequities and discrimination against Americans with disabilities [Editorial]. Medical Care, 61(2) 55-57. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001810

- Kahlke, R. (2014). Generic qualitative approaches: Pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13(1), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300119

- Kalman, H., Lövgren, V., & Sauer, L. (2016). Epistemic injustice and conditioned experience: The case of intellectual disability. Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women's and Gender Studies, 15, 63-81.

- Klausen, C. (2019). Knowledge, justice, and subjects with cognitive or developmental disability [Doctoral Thesis, University of Waterloo]. UWSpace. https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/handle/10012/15099

- Kinder, M. (2020, May 28). Essential but undervalued: Millions of health care workers aren't getting the pay or respect they deserve in the COVID-19 pandemic. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/research/essential-but-undervalued-millions-of-health-care-workers-arent-getting-the-pay-or-respect-they-deserve-in-the-COVID-19-pandemic

- Koffman, J, Gross, K., Etkind, S. & Selman, L. (2020). Uncertainty and COVID-19: How are we to respond? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(6), 211-216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076820930665

- Kumin, S & Schoenbrodt, L. (2016). Employment in adults with down syndrome in the United States: Results from a national survey. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 29(4), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12182

- Landes, S., Stevens, D. & Turk, M. (2020). COVID-19 and pneumonia: Increased risk for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the pandemic [Brief]. Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion. https://lernercenter.syr.edu/2020/04/27/COVID-19-and-pneumonia-increased-risk-for-individuals-with-intellectual-and-developmental-disabilities-during-the-pandemic

- Landes, S., Turk, M., Formica, M., McDonald, K. & Stevens, J.D. (2020). COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability living in residential homes in New York State. Disability and Health Journal, 13(4), 1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100969

- Laverty, S. (2003). Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: A comparison of historical and methodological considerations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(3), 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690300200303

- Lincoln, Y. and Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

- Mark, J., Hobbs, F.D.R., Bernal, J.L., Sherlock, J., Amirthalingam, G., McGagh, D., Akinyemi, O., Byford, R., Dabrera, G., Dorward, J., Ellis, J., Ferreira, F., Jones, N., Oke, J., Okusi, C., Nicholson, B.D., Ramsay, M., Sheppard, J.P., Sinnathamby, M., Zambon, M., Howsam, G., Williams, J., & de Lusignan, S. (2020). Excess mortality in the first COVID pandemic peak: Cross-sectional analyses of the impact of age, sex, ethnicity, household size, and long-term conditions in people of known SARS-CoV-2 status in England. The British Journal of General Practice, 70(701), e890–e898. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X713393

- McCausland, D., McCarron, M., and McCallion, P. (2022). Use of technology by older adults with an intellectual disability in Ireland to support health, well-being and social inclusion during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(2), 175-190. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12514

- McDonald, K. E. (2012). "We want respect:" Adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities address respect in research. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(4), 263-274. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-117.4.263

- McGarry, B., Grabowski, D. & Barnett, M. (2020). Severe staff and personal protective equipment shortages faced by nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Affairs, 39(10). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01269

- Monteleone, R. (2020). Account/ability: disability and agency in the age of biomedicalization [Doctoral Dissertation, Arizona State University]. KEEP. https://keep.lib.asu.edu/items/158097

- Neusar, A. (2014). To trust or not to trust? Interpretations in qualitative research. Human Affairs, 24(2), 178-188. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13374-014-0218-9

- Rapley, M. (2004). The social construction of intellectual disability. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489884

- Rawlings, G. and Beail, N. (2023). Long-COVID in people with intellectual disabilities: A call for research in a neglected area. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(1), 91-98. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12499

- Shapiro, J. (1994). No pity: People with disabilities forging a new civil rights movement. Times Books.

- Silverman, A. (2020, March 27). People with intellectual disabilities may be denied lifesaving care under these plans as coronavirus spreads. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/people-with-intellectual-disabilities-may-be-denied-lifesaving-care-under-these-plans-as-coronavirus-spreads

- State of Alabama. (rev. 2010). Annex to ESF 8 of the state of Alabama emergency operations plan: Criteria for mechanical ventilator triage following proclamation of mass-casualty respiratory emergency. https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/6846-alabama-triage-guidelines/02cb4c58460e57ea9f05/optimized/full.pdf

- State of Alabama. (2020). Alabama crisis standards of care guidelines: managing modified care protocols and the allocation of scarce medical resources during a healthcare emergency. https://www.alabamapublichealth.gov/cep/assets/alcscguidelines2020.pdf

- Teachman, G., Gibson, B. and Mistry, B. (2014). Doing qualitative research with people who have communication impairments. In SAGE Research Methods Cases Part 1. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/978144627305013514660

- Temple, V. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic and individuals with intellectual disability: Special Olympics as an example of organizational responses and challenges. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 39(3), 285-302. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2021-0137

- Turk, M., Landes, S., Formica, M. & Goss, K. (2020). Intellectual and developmental disability and COVID-19 case-fatality trends: TriNetX analysis. Disability and Health Journal, 13 (3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100942

- Van Asself-Goverts, A., Embregts, P., & Hendriks, A. (2013). Structural and functional characteristics of the social networks of people with mild intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34 4), 1280-1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.01.012

- Van Holstein, E., Wiesel, I., Bigby, C., and Gleeson, B. (2023). More-than-care: People with intellectual disability and emerging vulnerability during pandemic lockdown. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 48(3), 525-540. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12595

- Wendell, S. (1996). The rejected body: Feminist philosophical reflections on disability. Routledge.

- Willner, P., Rose, J., Kroese, B., Murphy, G., Langdon, P., Clifford, C., Hutchings, H., Watkins, A., Hiles, S. & Cooper, V. (2020). Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of carers of people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(6), 1523-1533. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12811

- Wos, K., Kamecka-Antczak, C., and Szafranski, M. (2021). Remote support for adults with intellectual disability during COVID-19: From a caregiver's perspective. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 18(4), 279-285. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12385

Endnotes

-

While typically adhering to identity-first language

(disabled people vs. people with disabilities), I follow Gill (2015) in

adopting person first language when referring to intellectual disability as

a method of recognizing the long histories of advocacy for person first

language among self-advocates with intellectual and developmental

disabilities through organizations such as People First.

Return to Text - Due to public backlash, the State of

Alabama replaced this protocol with the 'Alabama Crisis Standards of Care

Guidelines' in August 2020.

Return to Text

Appendix: Easy Read Summary

|

|

|

|

Understanding COVID-19

|

|

Preventing COVID-19

|

|

Getting Information

|

|

Personal Responsibility

|

|

Changes to People's Lives

|

|

Strong Feelings

|

|

Relationships

|

|

Things I Learned From These Interviews

|

|

What Else Should We Know?

|