This article analyzes the depictions disability embodies in the fantasy film series Star Wars. Fantasy as a genre is able to re-present our past and present values through visionary forms and can act as a mirror to the society that creates the image. Fantasy is powerful as it enables films the ability to conceptualize realistic viewpoints and current day culture in their images and themes. In terms of Disability Studies, fantasy plays a critical role in the analysis of disability representation since fantasy is known for exploiting and transforming disabilities into Sharon L. Snyder and David T. Mitchell's "narrative prostheses." Once transformed, disability is used for its representational power rather than its true nature. Utilizing Roland Barthes's research on myth-making and Martin F. Norden's established disability archetypes, I discuss the varying portrayals disabilities have throughout the disability-laden series Star Wars. I discuss how disability portrayals rely on archetypes such as Norden's "Obsessive Avenger," the myth formation of disability as related to a sliding scale for evil, and as a symbolic connection to themes pertaining to technology's dehumanizing effects on humans. However, I also discuss the standalone Star Wars film Rogue One which diverges in portrayals through its exploration of Tobin Siebers's theory of complex embodiment. These films can act as a larger metaphor for films with disabilities today: taking steps when it comes to the improvement of disability representations, yet still behaving as perpetrators of long-held stereotypes and archetypes.

How Disability Meets Myth: Disability Archetypes Through History

This essay serves to explore how fantasy, specifically the Star Wars series which is one of the most popular fantasy series of all time, represents the images and experiences of disability and what that signals for society's viewpoints and conceptions surrounding disability. Drawing upon Roland Barthes's work Mythologies, where Barthes describes how images, words, and objects go beyond their basic existences and become political entities full of meaning, I analyze how disability and its associated images in the Star Wars films go beyond pure images on the screen and instead give a glimpse into the historical and current cultural conceptions of disability. 1 I find that these political and cultural images parallel, but in recent films slowly diverge, from established disability archetypes. Several of the most striking and highly utilized archetypes are developed by Disability Studies scholar Martin F. Norden in his novel The Cinema of Isolation: A History of Physical Disability in the Movies. 2 His novel draws upon the myth-making involved in concepts such as disability and evil alongside work pertaining to disability's connection with technological developments and the concept of the cyborg. Utilizing Norden's archetypes and Barthes's work on myth-making, I provide an analysis of how the Star Wars films fit— or diverge— from the trajectory many films have followed when it comes to the representation of disability.

In Barthes's Mythologies, Barthes explains how myths are forms of stolen language, done through the process of robbery. 3 The robbery surrounding the myth is completed by transmuting (or more specifically, stealing) the basic existence of images, photos, reports, and objects (which he terms the "signifiers") as a way to have them become "signs" with chosen "signified" concepts and themes. The entities that are utilized as sites for chosen messages are then "deprived of their history, changed into gestures." 4 The original image becomes empty of its actual nature, instead having to create room for what the creator determines it should signify. This analysis of the nature of myth-making aligns heavily with the portrayal Hollywood cinema has historically created when it comes to disability.

The creator of the myth— the sign laced with specified significations— sits in a position of power. This creator- whether it be the film's writer, director, producer, or any individual with a significant say in the direction of a film's image or story- plays a significant role in the myth making process. This power hinges on the ability to attach meaning to bare existence. In films with disability, a significant portion of the creators of the myth are not disabled. 5 , 6 The power then sits with the non-disabled creator in establishing the role disability has in the visual medium. Disability's portrayal in film is "tied not by the observed [those who are being portrayed], disabled people, but by the non-disabled observers." 7 As a result, although disability may be physically present on the screen, it is simultaneously erased by being created without disabled people behind or in front of the camera, and by the lack of forethought of disabled people in the roles of observers. In terms of Barthes, the archetypes disability inspires are appropriated, with their depictions appealing to certain groups (non-disabled audience members) while ignoring the very groups they depict (disabled individuals). 8

From the 1890s to today, the images of disability have emerged in relation to events and attitudes at the time of the film's creation. Martin F. Norden has coined prominent archetypes such as Comic Misadventurers, Obsessive Avengers, Noble Warriors, and Techno-Marvels. 9 These archetypes establish not only a simplified way of tackling sometimes complex characterizations of disability, but are laden with the sociocultural and historical viewpoints of the times they were created.

Comic Misadventurers, for example, arose from as early as the 1890s. During this time period, there were social concerns about beggars who were faking disabilities in the United States and Europe. 10 Upon a police arrest in 1896 of 3 beggars pretending to have disabilities, many police departments throughout the United States began cracking down on beggars pretending to be disabled. Films capitalized on these social events, creating characters who pretended to have disabilities in order to wrangle money out of non-disabled civilians. A relevant example is Cecil Hepworth's The Beggar's Deceit, a film from 1900 where a begging individual who pretends to be disabled is suddenly able to walk after a police officer chases him down amidst discovering his lies. 11 These negative and harmful depictions surrounding disabled people as being manipulative and out to grab unwarranted social benefits are present even today. Many view disabled people as "cheats…trying to obtain benefits such as welfare payments, better parking spaces, or cuts in line in Disneyland." 12 These stereotypes are mostly fueled by able-bodied individuals (rather than disabled people themselves), who fake disabilities for "advantages." For example, in places such as Disney World, many able-bodied individuals have admitted to faking disabilities or hiring tour guides who they notice have visible disabilities in order to gain shorter wait times or other "privileges" during their trips. 13 , 14 As a result, policies have changed and made experiencing places like Disney World exponentially more difficult for disabled people who needed these accommodations to experience the parks more equitably. 15 , 16 Similarly to how real-life policies that affect disabled people are highly influenced by able-bodied individuals rather than disabled people themselves, films act in a parallel manner.

Once films with disability impersonators gained popularity, filmmakers transitioned to making actual disabled characters (rather than impersonators) fill a comedic role for the humor of able-bodied audience members. 17 The transition to disabled people as a way to inspire humor led to the archetype of the Comic Misadventurer: a readily manipulated disabled person who gets into troubling situations because of his disability. A prominent example during the height of this transition is Mrs. Smithers' Boarding-School, a film from 1907 whose description from Moving Picture World includes scenes where a class of children ties a rope around their visually impaired teacher and "pull him up to the ceiling, [while he is] screaming and helpless." 18 This film, classified as a comedy during this period, is horrific and disturbing in its demonstration of abuse towards the teacher, purely because of his disability.

The correlation of sociocultural events and emerging archetypes continues with the Obsessive Avenger. This archetype is rooted in the belief that disabled people are evil, violent, and vengeful individuals in part, or as a result, of their disabilities. Films with this type of character archetype attach the disability as the reason for the characters' fascination with spreading pain and suffering onto others. This connection of disability and evil/monstrosity has existed for hundreds of years and is still in public consciousness today. In terms of history, examples abound. In ancient Rome, a correlation between evil and disability was present, with Emperor Augustus recorded to have "shunned dwarfs, the deformed, and all things of that kind as evil omened mockeries of nature." 19 Here, disabled children would be drowned in the Tiber River in small baskets ("death boats") and games at the Coliseum would include disabled children being thrown under horses' hooves, dwarves fighting women, and blind gladiators fighting each other for the pleasure and enjoyment of able-bodied audiences. 20 , 21 During the Great Witch Hunt of 1480-1680 in Europe, an estimated 8-20 million people, many of whom were disabled, were put to death on account of being witches. 22 At this time period, a treatise called The Hammer of Witches (1487), written by two priests, described how to identify witches, citing impairments and giving birth to disabled children as clear indicators. 23 Even today, in various cultures, religions, and locations around the world, a connection between disability and evil persists. For example, disability has been connected to the motif of the evil eye, the eye which transmits a feeling of envy that "betrays itself by a look even though it is not put into words." 24 The power of this envious look could debilitate and kill the person it is directed at. The belief that the look of an all pervading, ill-wishing evil eye as being a cause of disability has been studied between individuals of a variety of cultures, such as Turkish, Saudi Arabian, and Nicaraguan. 25 , 26 , 27 The association of disability and evil extends beyond the evil eye, however, and even into persistent current-day beliefs in areas such as, but not limited to, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Angola where disability is believed to be connected to witchcraft by a number of individuals. 28

Paul Longmore, a North American disability rights activist, has written extensively on the connection of disability and monstrosity or evil as well: "The depiction of the disabled person as "monster" and the criminal characterization both express to varying degrees the notion that disability involves the loss of an essential part of one's humanity. Depending on the extent of the disability, the individual is perceived as more or less subhuman." 29 These depictions exemplify the ""spread effect" of prejudice" wherein there is an assumption that "disability negatively affects other senses, abilities, or personality traits… The stigmatized traits assumedly taints every aspect of the person, pervasively spoiling social identity." 30 This therein carries over into the "attitude that there is a loss of self-control and thus as endangering the rest of society." 31 This can be exemplified in many instances common today, including when individuals assume one with a physical disability has cognitive or emotional disabilities as well, or vice versa. The individual with a disability faces even further Othering from individuals upon multiple additional assumptions of disability status, and these assumptions build upon the belief of a spoiled social identity, one that lacks 'normalcy' and inspires "frightening possibilities to many." 32

The connection of sociocultural attitudes and events to the creation of disability archetypes continues with Martin's Noble Warriors and Techno-Marvels. The Noble Warrior emerged upon the U.S's entrance in WWI and WWII, when disabled veterans were considered heroes who acquired disability as badges of personal sacrifice. Much of the films during the WWI era had cure narratives, where the veterans would regain lost functions through operations and treatments. 33 This curability focus changed to a much more progressive depiction of disability after the end of WWII. Here, Noble Warrior films started to focus on social consciousness, rehabilitation, and post-rehab issues. The 1950 film The Men is an example of this. Here, director Fred Zinnemann examined the story of a veteran paralyzed by a bullet to the spine and his path to acceptance in post-rehabilitation. In order to create the film, Zinnemann visited V.A hospitals, recruited veterans who actually used wheelchairs for the film, and used their suggestions and ideas for the creation of the film. 34 This film "works as a powerful, unromanticized account of newly disabled people and one of the most sensitive films to deal with physical disability issues." 35 Unfortunately, these movies were put to a decline upon the McCarthy era when many of the creators of these progressive films were blacklisted or forced into hiding. 36 The Techno-Marvel archetype as well, characterized by an individual cured of disability through technology, arose during the 1970s-80s where there began a high growth in scientific and technological advances in the U.S. 37 This example is seen in popular film series such as Star Wars, when protagonist Luke Skywalker loses his hand in the 1980 film The Empire Strikes Back, but has a technological prosthetic replace it, one that looks and functions almost identical to his former hand.

Thus, the archetypes and myths that grow out of disability are as a result of the creator themselves and the inspiration of the culture and time period around them. Rather than film being an unattached media production separated from reality, film is rather the opposite: it is inspired and a product of the values, thoughts, worries, and events that occurred at the time of the image. 38 Film behaves in a cyclical fashion, where the culture creates the image, and the image can affect the culture. Thus, through looking at and studying film, film can act as a mirror which reflects not only the image and message it is portraying, but also the society and culture that created it. A prominent illustration is in the months following the release of Disney's 1996 film The Hunchback of Notre Dame (a film which has been widely criticized by individuals in the disability community) leading to a "rise in violence against people with scoliosis in the U.K," linked to the depiction of Quasimodo's back in the film. 39

Although fantasy as a genre may seem removed from realistic concerns, it can provide "escapes from reality, [but] can also empower." 40 This empowerment stems from the fact that superheroes, princesses, and other characters are often some of the first adult figures children are exposed to through the media, providing traits and characteristics children can mimic. Fantasy films and stories, which throughout a variety of cultures are important parts of childhood, provide a means of social learning, where children learn values and cues from aspects of the film. If a fantasy figure that children find inspiration and likeness to espouses certain behaviors, children are apt to follow suit. This has been explored through research such as Cinderella and Snow White's effects on young girls, among other studies. Girls who watched both films and enjoyed them were found to play more with tea sets than toolsets, which can be linked to Cinderella and Snow White's common gender-stereotypical behaviors of cooking, cleaning, and tending to the home. 41 Additionally, fantasy enables children and viewers of all backgrounds the ability to experiment with different worlds and cultural landscapes. In learning of a new cultural and social environment through the fantasy world, a viewer can acquire a better understanding of their own in real life. Fantasy helps "revisit values and views instilled during childhood [where one can] see, vividly displayed, deep-seated… attitudes that have been reinforced by cultural and political contexts as normative." 42 Fantasy creates a world separated from our own, yet deeply linked to it through the values and themes explored. An interpretation of the genre's persistent themes, archetypes, and images can unveil deeply rooted realistic viewpoints. Fantasy is well known to also provide a means of escapism to the viewer, where one can put current day struggles and worries on pause as they transport to the universe in question. In fantasy, what may be impossible in reality is a norm in the manufactured world. What is yearned for or loathed in that world can provide a window into one's own consciousness. The very nature then of fantasy can be critical in relation to Disability Studies, where through the study and re-evaluation of disability's image, insight can be gathered into evolving, or stagnant, conceptions of disability and its role to the individual and society.

This essay then aims to analyze how fantasy, specifically the worldwide hit Star Wars, represents the images and experiences of disability and what it can teach us about society's viewpoints on and conceptions of disability.

Disability in Star Wars: An Exploration of Visible Disability's Portrayals

From Star Wars' first film A New Hope (1977) to its latest 2019 box office hit The Rise of Skywalker, the series is one of the most successful of all time. The films have grossed over $10 billion dollars, with a rate of return over 6 times their budget. 43 The series features a number of disabled characters, such as Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, and includes disability as a recurring motif. Although the films are not primarily focused on the theme of disability per se— but instead on themes like righteousness versus evil— the heavy inclusion of disability in the characters and storylines invites audience members to think about disability throughout the series. Star Wars's disabled characters have even inspired companies, such as Open Bionics, to create Star Wars inspired robotic limbs for children. 44 Designs include characters such as BB-8 and R2-D2, which have recently gone viral when an 11 year old girl posted a video of her bionic limb and attracted the attention of Mark Hamill, the actor for Luke Skywalker. 45 , 46 Mark Hamill has even collaborated with Open Bionics, sharing a message in "Mark Hamill's special message for kids with limb differences" to "remember, Luke lost his hand to Vader, but that didn't stop him from defeating the Empire." 47 Although it is important to realize that economic factors influence such choices of collaboration (Star Wars merchandise can capture people's attention and inspire purchases), Hamill's connection between his character Luke's missing limb to the prosthetics available for children with similar disabilities signals Luke's status as an important character with a disability. Thus, portrayals of disability in Star Wars can act as powerful tools for children looking for role models who can mimic themselves, especially if there may not be any in the community around them. Star Wars's prominence and worldwide success can give the series power when it comes to creating avenues for empathy and education about various social concerns. As Star Wars has progressed in its portrayal and inclusion of women and people of color in important roles, it is then important to look at the portrayal of disability, since as of 2014, approximately 17% of individuals 18 and younger had a disability, and as of 2016, an estimated 1 in 4 adults has a disability in the United States. 48 , 49 , 50 These statistics may in truth be conservative estimates of the actual number of disabled children and adults, given that the definition of what constitutes a "disability" is still a highly contested topic. Therefore, the number of individuals living with lifelong and chronic disabilities may be higher than 17 per 100 children and 1 in 4 adults in the United States today.

Disability as a Sliding Scale for Evil: From Christ Figures to Harbingers of Death

Although the Star Wars series has increasingly been conscious of social issues and progressed in its portrayals of various minority groups— including but not limited to race, sexuality, and disability—the series supports Barthes's analysis of myth-making, most prominently through the films' relation of disability with the notions of villainy and evil, both metaphorically and literally through actions undertaken by the characters. The myth-making process present in the films fit Barthes description of the concept and the form: the "concept [the meanings associated with images]….reconstitutes a chain of causes and effects, motives and intentions. Unlike the form [here, the disability], the concept is in no way abstract: it is filled with a situation. Through the concept, it is a whole new history which is implanted in the myth." 51 Involved in the concept and form of disability and villainy in the series is the inclusion of Norden's archetype of the Obsessive Avenger. As a part of the myth making that connects the image of disability to the Dark Side and the evil that it espouses, characters such as Anakin develop into archetypes like the Obsessive Avenger, a character "(almost always an adult male) who in the name of revenge relentlessly pursues those he holds responsible for his disablement, some other moral-code violation, or both…. [this] reinforces two of mainstream society's most deeply entrenched beliefs about disabled people in general and disabled men in particular: "deformity of the body is a sure sign of deformity of the soul" and "disabled people resent the nondisabled and would, if they could, destroy them"" 52 This is closely linked to how throughout the Star Wars films, a pattern emerges where disability is connected with a progression of evil. 53 This "sliding scale" illustrates that the more disabled a character is, the more morally corrupt and evil they are, as exhibited by their actions and their symbolism. As a character moves up the scale of evil, so too does the representation of disability, and in turn the mythology that connects the image of disability to the Dark Side, which coincides with immorality and can be depicted by examples like "the destruction of the Jedi (metaphysical level)… [or trying to establish oneself] as the sole ruler by destroying the Galactic Republic and replacing it with the Empire (political level)." 54 One of the most widespread examples of a sliding scale direction of disability to evil is in the character Anakin Skywalker. In the first film The Phantom Menace, Anakin is characterized as an almost Christ-like figure. 55 He is depicted as having no father and is believed to be the "Chosen One" who is spoken of in a prophecy. This prophecy writes that there would come a person who would bring balance to the Force- a spiritual entity which has a Light and Dark side.

The Christ-like figure allusion is developed further by depicting Anakin's kindhearted and progressive nature and his fight for basic human rights. During the moments of Anakin's morality and Messiah-like nature, Anakin is an able-bodied male. Although during these moments Anakin is revealed to have fear inside of him and a potential for the Dark Side, the film characterizes Anakin as a morally upstanding character.

The sliding scale of disability and its correlation with the myth creation of evil starts in Attack of the Clones. 56 Here, an older Anakin is shown to have a tense relationship with his mentor Obi-Wan Kenobi. Obi-Wan even goes so far as to reprimand Anakin to "know [his] place" upon Anakin's refusal to follow orders of protecting Padme (his object-choice57 of love), desiring to find and hunt down those who previously tried to kill her instead. His descent to the Dark Side becomes clearer when he, in true Freudian fashion, begins to have nightmares of his mother who he had to abandon upon acceptance as a Jedi. Anakin has a repetition-compulsion of these nightmares, continuing to see her as being in danger, an image which inspires great pain and worry in him. 58 He shortly thereafter discovers that his mother was kidnapped by Tusken Raiders, and finds her beaten which leads to her death. Anakin, a Jedi whose principles include self-control, kindness, and morality, goes into a murderous rage, slaughtering the entire village of Tusken Raiders, many of whom were uninvolved with what had happened. He feels guilt over his murderous impulses and expresses his shame to Padme, but this morally horrific action has led Anakin to give in to the Dark Side. The Dark Side feeds off of hatred, rage, passion, and violence and is emblematic of the villainy Anakin has just physically committed. Shortly after this mass murder, Anakin fights Count Dooku (who is part of the Dark Side's Sith), and gets his hand sliced off. The severing of the hand acts as punishment for Anakin's previous actions which were acts of disobedience to the established "Light" side. 59 This entwinement of disability with punishment arises from a societal belief that disability occurs as a punishment for one's moral actions, actions ranging from morally ambiguous to completely dishonorable. 60 , 61

Figure 1. In the left photo, Count Dooku, a man holding a lightsaber and sporting a white beard, holds a red glowing lightsaber in both hands. Anakin, to the left of him, is shown with his back to the camera with his hand chopped off and his remaining arm glowing red. On the right photo, Anakin is lying down, unconscious, with his arm now cut in half and missing his hand. The severing of Anakin's hand is a symbol for punishment on account of his previous behaviors and the growing Dark Side within him. (Copyright 2002, Lucasfilm)

At the end of Attack of the Clones, Anakin receives a robotic hand replacement made of wires and metal which is panned in on during his forbidden marriage to Padme in Naboo. This marriage is off limits by Jedi doctrine, and is revealed to be kept a secret when Anakin neglects to tell Obi-Wan about it. Thus, the image of Anakin's robotic limb can be a further symbol of Anakin's descent towards the Dark Side and his disobedience from the established moral pathway, since its image is associated with acts characteristic of the Dark Side, including passionate relationships and disobedience. Anakin's robotic limb becomes "appropriated…. [and] cannot fail to recall the signified," where here the form [the arm] is the signifier that now becomes encompassed with the concept of the Dark Side, the signified. 62

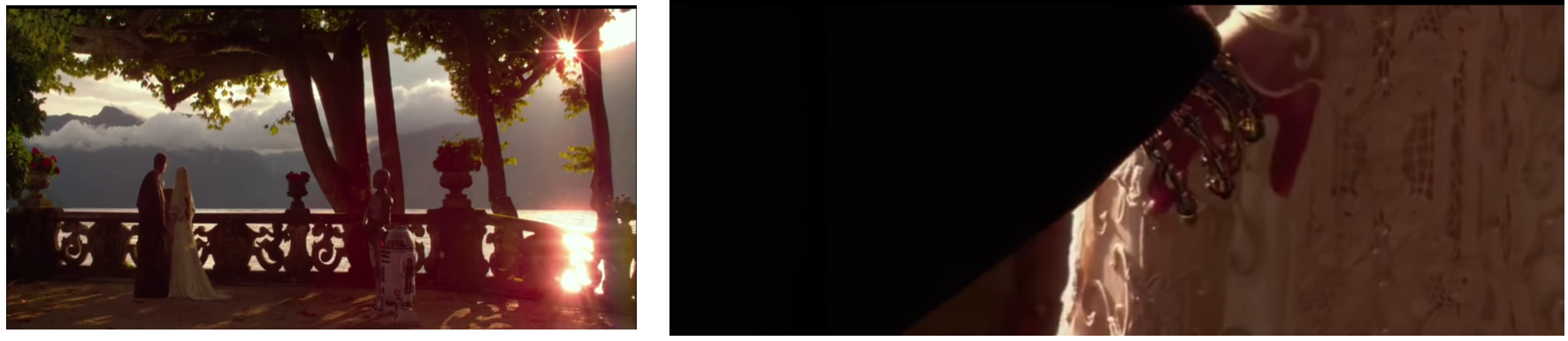

Figure 2. In the left photo, Anakin and Padme stand near the end of a wrought iron fence bordering a glistening lake. Anakin is wearing long, brown robes and Padme dons a white veil and lace wedding dress. Here, Anakin and Padme's forbidden wedding ceremony is shown and the first glimpse of Anakin's hand after being severed by Count Dooku is depicted. On the right photo, there is a pan-in on Anakin and Padme's hands. Anakin now wears a gold, robotic prosthetic as he holds onto Padme's flesh hand. The pan-in of the camera to his robotic limb, and its first appearance in conjunction to a forbidden ceremony, further depicts the connection of disability with the Dark Side and deviance. (Copyright 2002, Lucasfilm)

Anakin continues his descent to evil in Revenge of the Sith. 63 Here, the film opens with a prominent facial scar on Anakin's right side. This scar signals the moral decay that Anakin will have in the rest of the film, where he completes his descent to Darkness. Visual scarring, as used here with Anakin, is commonly used in the representations of villains. A prominent example from other mainstream films is the Joker in Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight trilogy. The Joker, who terrorizes and kills countless people, is known for his bright green hair and facial scars which give him a permanent smile. The linkage of visual scarring to characters who depict and symbolize evil even led to the social media campaign #IamNotYourVillain, where the United Kingdom based charity Changing Faces, created for people with visible differences, worked "to de-stigmatize facial scars in film and television since scarring is often used on villains (see The Joker, Darth Vader, and more)." 64 Their activism led to the British Film Institute no longer funding films with facially scarred villains, and actually financing films attempting to correct the conversation surrounding visible differences.

In Star Wars, soon after the initial image of Anakin's new facial scar, Anakin severs Count Dooku's arms off, Dooku being the one who had sliced Anakin's arm off in the previous film. When Senator Palpatine tells Anakin to kill Dooku, Anakin knows he should not (as Dooku is an unarmed prisoner and that is "not the Jedi way"), yet he does so anyway. Palpatine replies with, "It was only natural. He cut off your arm, and you wanted revenge." Shortly after this statement, Palpatine brings up Anakin's past murder of the Tusken Raiders and Anakin looks away in shame. However, Anakin does not confirm or deny the statement which claims he avenged his lost hand, and his silence signals quiet confirmation of the now legitimate accusation of revenge. This scene is reminiscent of Norden's Obsessive Avenger archetype, as Anakin indirectly confirms that the loss of his limb caused his desire to murder Dooku. Anakin's desire to avenge his arm mimics an ""overwhelming compulsion" to repeat the experience by inflicting it on someone else…[which accounts for] the sense of uncanniness and fear generated by the Obsessive Avenger, in that it makes the disabled character appear to be possessed by evil, terrifying spirits." 65 As Norden explains, "[the Obsessive Avenger] develops an irrational and over-whelming desire to repeat the experience…The character transforms this desire into vengeful action by seeking to disempower the figures he holds responsible for this moral-code violation…Audience members thus witness an exaggerated playing-out of a character's repetition-compulsion, triggered by the memory of an earlier moral-code violation- usually, that character's disablement." 66 Anakin's desire for vengeance and the repetition of limb loss through doing it to someone else directly links him to the Dark Side, symbolizing how these desires, which stem and are because of his disablement, inspire the immorality that he commits. Anakin's connection to Norden's Obsessive Avenger archetype strengthens the myth's signified concept of evil to the form/signifier of disability, where his actions— which are forbidden and which he knows are not right— are because of his need to avenge his own disability and repeat what was done to him onto others.

Figure 3. In the two pictures above, the camera pans in on Anakin's face as he steers a ship throughout space. Anakin is wearing a gold headset over his blonde hair, and has a prominent red scar that cuts across the top of the right side of his face, from his forehead and eyebrow to just below his eye. Anakin's new facial scar (left side of his face in this photo, right side of his face in general) signals the further stray from the Light Side that will occur in the rest of the film. (Copyright 2005, Lucasfilm)

The connection of disability to the evil Dark Side continues when Anakin has a nightmare about Padme, his now pregnant wife, dying during childbirth. When he awakes, he is filmed with his entire robotic arm in display. While at other times in the film before this scene, Anakin's bionic limb is covered, this scene has it in full view for the spectator to watch and gaze upon. The robotic limb is in view for several moments, inviting the spectator's gaze to study him and his new robotic addition. This places emphasis on Anakin's new corporeality and highlights his status as an individual with a technological prosthetic because of a disability. The focus on Anakin's new arm invites the audience member to think of Anakin's new bodily state, and the process of its becoming. In the words of Laura Mulvey, the scene has a scopophilic intent, whereby Anakin is subjected to a "controlling and curious gaze" from the observer. 67 This contributes to Anakin's role as a signifier of the connection between disability and villainy, where his corporeality is a result of the events and actions that previously occurred.

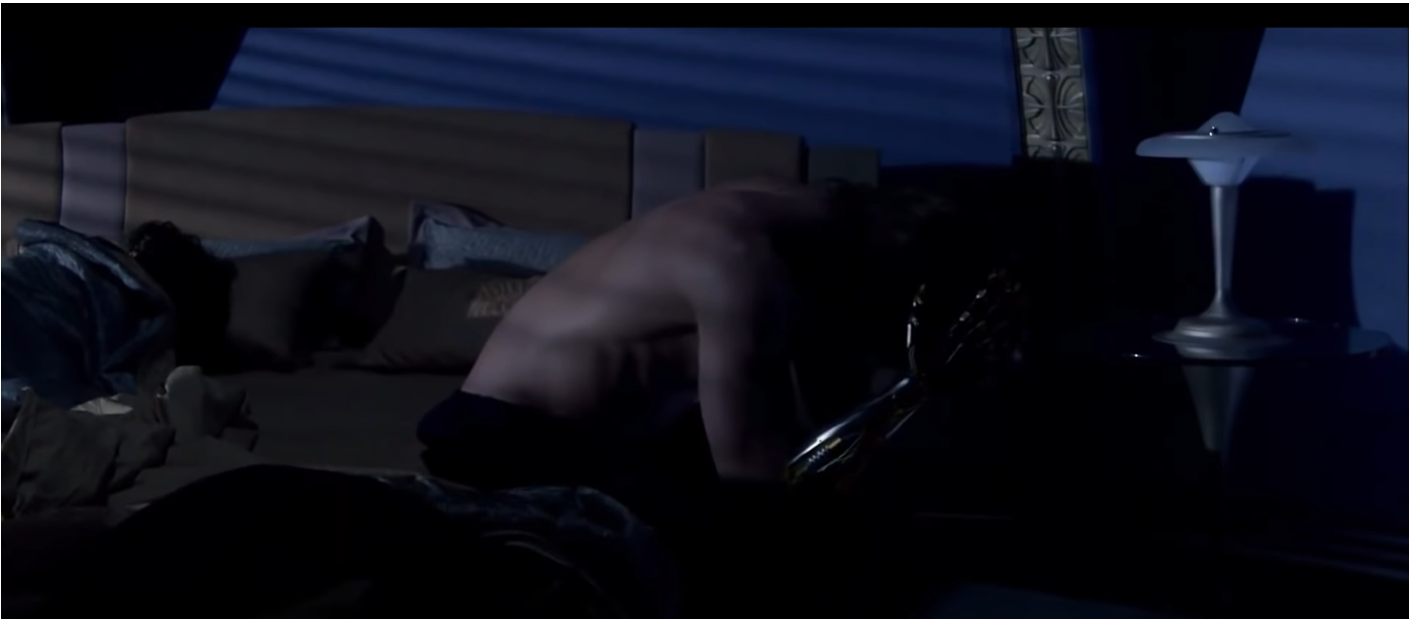

Figure 4. Pictured above is Anakin upon waking from the dream that triggers his complete descent to the Dark Side. Pictured is Anakin sitting up on his bed with his head in his hands, his robotic arm in display. Anakin is not wearing a shirt, and the side of his body with his robotic limb is directed at the camera. This angle invites a scopophilic gaze, associating his technological limb with the nightmare that seals his evil pathway. (Copyright 2005, Lucasfilm)

This dream is the tipping point for Anakin's complete turn to the Dark Side. Out of fear for the dream being a psychic vision, Anakin becomes entranced with Palpatine. Palpatine tells Anakin that in order to become powerful enough to prevent death, Anakin needs to follow Palpatine's orders, which include killing an entire temple full of Jedi children, murdering Palpatine's political enemies, and becoming disillusioned with the Jedi themselves. After Anakin fulfills Palpatine's commandments, Padme comes to convince Anakin to come back to the Light Side and denounce the path he is moving towards. Anakin instead chokes her and fights with Obi-Wan, who has come to defeat Anakin for the threat he poses. This fight scene is where Anakin becomes even more disabled than before: Obi-Wan cuts off Anakin's legs, his remaining arm, and leaves him as he gets burned in the lava that surrounds the ground he lay on. Anakin screeches out "I hate you!" to Obi-Wan, the Dark Side taking hold of him as signaled by his hatred.

Figure 5. Pictured to the left is Obi-Wan and Anakin after their fight on Mustafar, a planet with lava rivers and brown sloped rocky hills. Anakin is on the edge of a hill, near the lava below, with two of his legs cut off, an arm cut off, and his remaining robotic arm pushed in front of him to try to lift himself up. Obi-Wan stands farther up the hill, moving away from Anakin. On the right, Anakin has touched the lava below and is beginning to burn. His entire body is on fire, and his originally pale skin is now burning and full of fire. (Copyright 2005, Lucasfilm)

Anakin is left to die, trying to escape the nearby lava by using his mechanical hand to move himself up the hill. This scene utilizes disability to progress Anakin's descent into a figure of evil and moral corruption: as Anakin becomes morally "worse," he has more and more disabilities and deformities associated with him. This can be related to how Barthes describes myth-making as "to transform a meaning into form." Here, Anakin's body is the form that takes on the symbolism and face of the Dark Side. 68 Gone is the Christ-like figure able-bodied Anakin once embodied. Instead, what is left of him is a monster who kills children and chokes his own wife. Palpatine later comes and collects Anakin's body off the ground, bringing him to a medical bay for his injuries. At this medical bay, Anakin is laid on high-tech gurney where robotic attendants give him bionic replacements for the limbs that he lost. As the film shows scenes of Anakin's mechanical surgery procedures, they are overlaid with images of Padme giving birth far away, laying down on a table similar to his. The message is clear: while Padme is creating new life while she herself is dying, the opposite is shown for Anakin. The films propose that Anakin has gone from life to death, from the able-bodied Christ figure he originally was to a machine-encrusted Sith instead.

Obsessive Avengers' Reliance on the Oedipus Complex

It is important to note the role the Oedipus complex, and thus gender, plays in Anakin's descent to the Dark Side and his role as a figure for the archetype of the Obsessive Avenger, which works towards the mythology surrounding disability. 69 Norden explains how films depicting disability and an Oedipus complex together position male characters as needing to resolve their Oedipus complex by "repressing interest in the mother under threat of castration from the Father and then identify[ing] with that authority figure or destruction will follow." 70 The Oedipus complex has a large role in the Star Wars universe, as Anakin is characterized as lacking a literal father figure and having a close relationship with his mother. Once his mother dies, Padme takes on the role of a mother figure, exemplified especially when she becomes pregnant. Her characterization is further established as the new mother figure through the dreams Anakin has of her dying. In these dreams, her image appears through a water-like film where she calls for help and the screams of a baby are heard in the background.

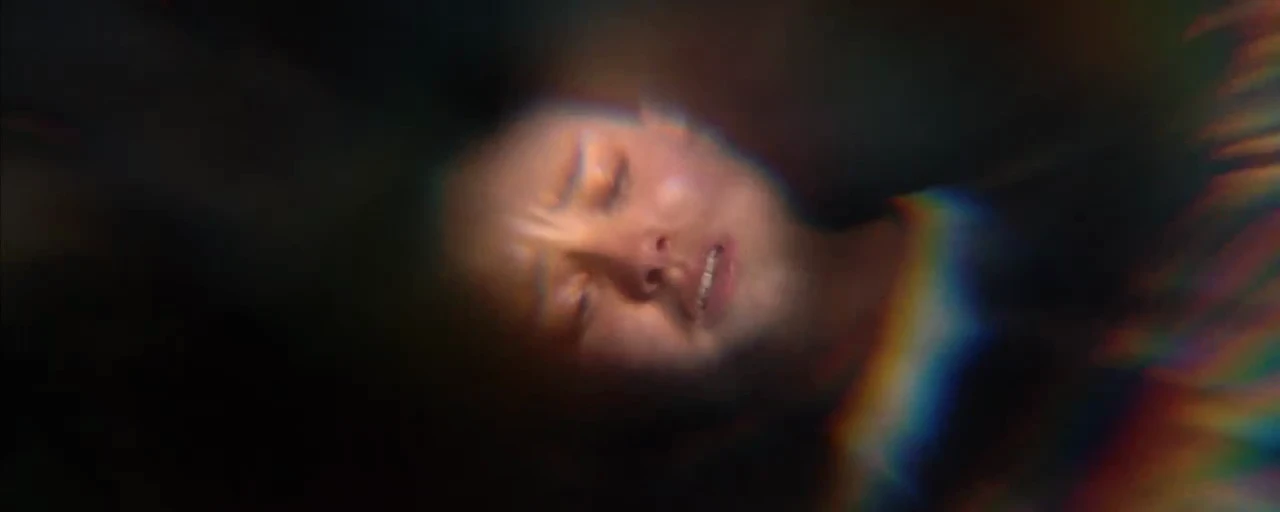

Figure 6. Depicted above is Anakin's nightmare consisting of Padme giving birth and dying. Padme is seen lying down, her face scrunched up in pain. This nightmare appears via a water-like image, where Padme's face is blurry and a rainbow appears near the right side of her face. The rainbow in the photo is analyzed as similar to when light hits water droplets, reflects off the inside of the droplets, separates into different wavelengths, and upon exit from the droplet, creates a rainbow. (Copyright 2005, Lucasfilm)

According to Freud, "a man rescuing a woman from the water in a dream means that he makes her a mother… making her his own mother." 71 Obi-Wan, who Anakin has admitted time and time again is the closest thing to a father he has, becomes the father figure in this scenario. Norden explains how films with Obsessive Avengers and Oedipus complexes "show what happens if the male refuses to control his desire for the Mother (and thereby bucks the patriarchal system) and is symbolically castrated. Disempowered and filled with revenge, he becomes a "monster" in his idiosyncratic quest to regain the phallus…. [and] almost always perishes." 72 Since Anakin could not resolve his Oedipus crisis through repressing interest for Padme, the mother figure, he faced threat of castration from the father figure, Obi Wan. Through not identifying with the father figure, destruction ends up happening to Anakin, where Obi Wan castrates him by attacking the arm and legs used most prominently during protection and fighting. The chopping of Anakin's arm and legs can be viewed as "symbolic castration arising out of a phallic-stage conflict between son and father," especially considering that one of Anakin's "power appendage[s]" is cut off, the one that wields a lightsaber and is meant to protect him and fight with. 73 Through the severing of one's hand, not only is one's ability to wield a lightsaber affected, but the resultant level of masculinity is as well since it induces castration anxiety. Thus, disablement in Anakin coincides with a crisis in masculinity. 74 , 75 , 76 Anakin's inability to form a traditional male identity through identifying with the male authority figure is connected to his disablement, which in turn is related to evil. The presence of an Oedipus complex in this circumstance is used to further "disable" Anakin by portraying him as a male who refuses to assume "a traditional male identity," which is an element of his role as an Obsessive Avenger and as the form/signified that adopts the concept/signifier relating disability to the Dark Side. 77

The Cyborg and Evil: "More Machine Than Man"

The heavy prevalence of technology and robotic replacements as a result of Anakin's descent to the far end scale of evil should not be discounted. As much as disability is used to highlight moral decay, the presence of technology in Star Wars can as well. 78 For one, by analyzing the armies each hero has fought in the film, almost all are robotic. Meanwhile, the armies that fight with the heroes are human or other "natural" creatures (such as animals). Droids and clones (although they helped the heroes during Attack of the Clones, they are revealed to indeed be toys of the Dark Side) both fight on the side of evil. Even stormtroopers, who although human underneath their suits, are depicted as robots and fight for the Dark Side. The stormtroopers are given names emblematic of codes and suits made to depict mass conformity, strikingly similar to the nature of robots. Even those who did surgery on Anakin are all droids themselves who "extend[ed] their artificiality into the living flesh that they repair[ed]." 79 , 80 Anakin's metaphorical human death is further emphasized with the presence of the droids who affix robotic technology on him, symbolizing Anakin's descent into machine rather than man, which is combined with his descent into evil. The expanse of technology and bionics contributes to Anakin's form, where the concept and signifier of villainy becomes attached to his technology, as the bionics represent his fight with Obi Wan and the evil he committed to get to that point.

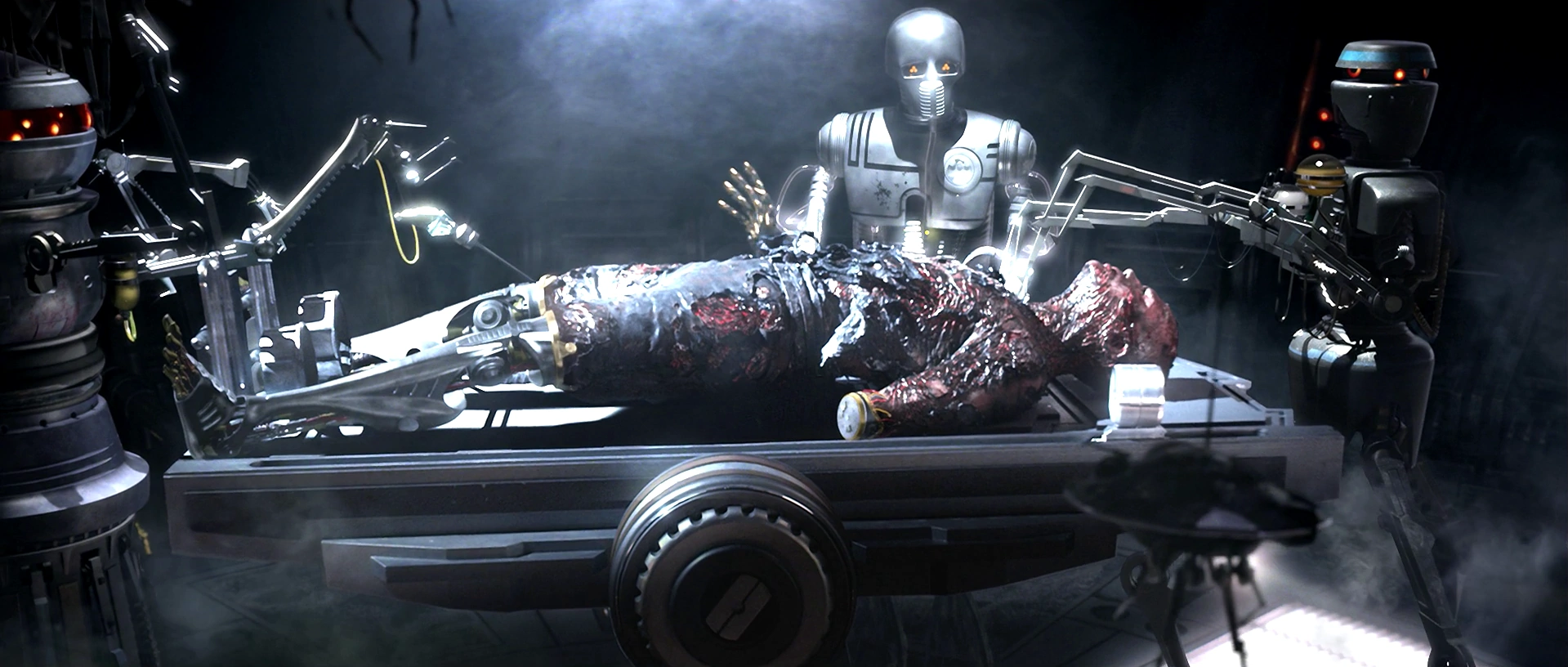

Figure 7. Pictured above is Anakin's surgery after his battle and disablement on Mustafar. Here, Anakin is lying down on a grey metallic table while three grey mechanic droids are repairing his burnt body. The droids are inserting a robotic arm, legs, and suit on him as he lies down. The implementation of his new prosthetics done through droids depict the "lifelessness" of Anakin post-disablement. (Copyright 2005, Lucasfilm)

As the story continues in A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back, Anakin— now termed Darth Vader— is now portrayed as a man in a suit, the sound of robotic breathing characterizing his presence every time he appears on the screen. 81 , 82 Thus, his evil is attached to the sound of a lack of breath and he is associated with a non-human machine through the superimposing black suit meant to keep him alive. When Luke, Anakin's son, speaks of Darth Vader's chances for redemption, Obi-Wan tells Luke that Darth Vader is "more machine now than man" and is "twisted and evil." 83 This gives the implication that there is no longer hope for Vader in part as a result of his disabilities, disabilities being the reasons for the machinery to begin with. 84 This statement is hypocritical coming from Obi-Wan though, considering it was he who had caused Anakin to become disabled and more "machine than man." Therefore, although this scene places emphasis on Anakin's dehumanization as a result of his machinery, it is important to note the hypocrisy of the situation. Obi-Wan, a Jedi who is categorized as being a morally upstanding character, says this about Anakin while simultaneously being the cause of the disablement in the first place. This situation mimics real-life situations where many able-bodied people do not consider their own roles in the social positioning disabled people have in society, although they themselves [the able-bodied] may be perpetrators of negative thoughts and actions done to them.

Additionally, this overlooked portrayal of Obi-Wan as a source of violence and debasement for Anakin when it comes to disability is lightly skimmed upon in the previous Revenge of the Sith. When Anakin and Obi-Wan are in an elevator together, Obi-Wan begins to insult R2-D2's (a droid's) ability to function, to which Anakin defensively tells him "hey, hey, hey… no loose wire jokes…. He's trying." Given that at this moment in the films Anakin has a newly prosthetic limb, it can be analyzed that although Obi-Wan may be poking what he sees as humor about a droid, Anakin may be taking it as a personal attack since he now literally has "loose wires" in his limbs. This scene, although minor, can further the analysis of technology's integration with disability as being depicted in dehumanizing ways from the able-bodied characters in the universe. 85

The Sliding Scale of Disability Re-emerges: Emperor Palpatine

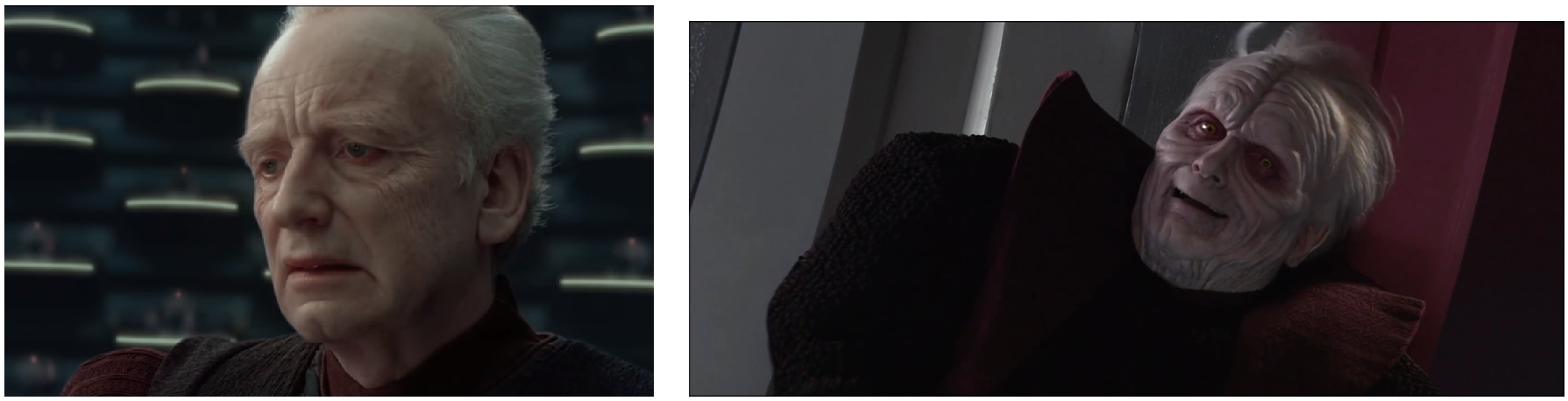

The myth creation between disability and evil, metaphorically and through action, is not limited to Anakin, and continues with the character Palpatine, who is a major villain throughout the entire series. At first, Palpatine is portrayed as an able-bodied male who is an ambitious Senator in the Republic. Once it is publicly and directly discovered that Palpatine is a Sith, during a fight with Jedi Mace Windu, Palpatine's face becomes disfigured and takes on a bright pale hue. He even tells the Senate after this event has transpired that "the attempt on my life has left me scarred… and deformed… but I assure you, my resolve has never been stronger!"

Figure 8. Illustrated above are images of Palpatine pre- and post- deformity after his battle with Mace Windu. The left picture depicts a man with pale skin and a few wrinkles. Depicted to the right is Palpatine "scarred… and deformed" with a purple hue to his skin, red-brimmed eyes, and creases along his face. (Copyright 2005, Lucasfilm)

It is critical to notice how Palpatine's diction reveals elements of disability conceptions surrounding lack and inability within the universe, as Palpatine needs to reaffirm his resolve and commitment to his duty upon the acquisition of a new disability, even though the deformity itself— to all those in the Senate that are listening— is just face value. Although, in analysis, deformity and physical disability are components involved with the mythology of disability and the Dark Side, those in the Senate do not know of Palpatine's connection to the Dark Side at this juncture. Shortly afterwards, with Palpatine's new face and body, he abolishes the Republic with the Empire, relinquishing liberty and freedom in the universe. Disability is then a signifier for a more evil downfall of Palpatine's character.

This continues in Return of the Jedi when Palpatine now walks with a cane. 86 In terms of the sliding scale of disability with moral decay, this can be attributed to his previous actions of building a Death Star (a tool which can kill an entire planet of people) and ordering Vader to kill his own son. Relating upon Barthes's work, Palpatine's corporeality is a signifier for the signified concept of his evil and villainy, and Palpatine as a whole becomes a sign whose body inherently represents these ideas. 87 Even in the new trilogy (The Force Awakens) we see this motif of disability as a sliding scale for evil when Palpatine reappears again as Snoke (a clone which Palpatine creates). 88 Snoke is a severely disfigured character who also orders the death of numerous planets full of people and manipulates Kylo Ren, one of the protagonists, to kill his own father.

Figure 9. Illustrated above is Palpatine's creation, Snoke, a mastermind for the evil First Order and shown as having facial deformities. In the picture, Snoke's rightmost eye is larger than his left, his forehead has a deep crescent scar, and the right side of his face has a sunken hole in his cheek. (Copyright 2017, Lucasfilm)

Once Palpatine appears again without his creation Snoke, he is now shown as blind, missing fingers, and connected to a robotic device with tubes that keep him upright. At this point, Palpatine has raised an entire Sith army and created the "Final Order," the snuffer of the entire Rebellion and any hope for resistance. As Palpatine worsens morally, the concept of evil "becomes form…leav[ing] its contingency behind; it empties itself, it becomes impoverished, history evaporates, only the letter remains." 89 Palpatine's entire corporeality represents the Dark Side, highlighted even more so as he is the leader of it. The disability sliding scale here turns Palpatine from an able-bodied man, to a deformed man, a deformed man with a cane, and finally a deformed man who's blind, fingerless, and attached to machinery. Once again, the use of technology here can be symbolized as further indication of Palpatine's evil nature and is a contribution to the overall mythology: he has become so connected with the Dark Side, in his words "every Sith lives in me," whereby he is a machine. Similar to Anakin, and exhibiting once more how Norden's Obsessive Avenger archetype contributes to the myth-making here that connects disability to villainy, Palpatine too follows in line with this archetype. This is shown when he tries to steal the life forces of Rey and Kylo (the two protagonists) when he notices that their powers could "restore" him from his disabilities. Palpatine starts to become cured by stealing their powers, with his fingers growing back as he yells, "the power of two restores the one!" As a result, Palpatine is shown to fall in line with the Obsessive Avenger archetype, where a desperation to be restored to able-bodiedness has him terrorize both protagonists of the film.

Figure 10. Sketched above is Palpatine's final version and most evil one yet. Here, he is now blind, deformed, and connected to tubes and machines in order to move and live. The left photo has Palpatine be blind in both eyes and connected to a device behind him full of tubes. The right photo shows Palpatine's hands, which are missing fingers and full of scars. (Copyright 2019, Lucasfilm)

Selective Techno-Marvels: Disability Erasure's Link to Morality

While the sliding scale of disability and evil is explored through Anakin and Palpatine, morally upstanding characters lack reliance on it. For characters who received disabilities or deformities and later become, or simply are, morally "good," disability either literally or metaphorically disappears. These characters do not have their forms forced with concepts and meanings as Anakin or Palpatine do, since their forms suddenly become cured of disability or fixed so much that disability seems to disappear. "Protagonists can be deserving of being cured and made whole again, whereas antagonists tend to become monstrous." 90 An example is Finn, who when sliced in the back with a lightsaber, is put in a medical ward connected to machinery and upon waking up, wakes up with no lasting injuries. Finn, who is a hero in the Force Awakens films, is cured because of his moral superiority, while people like Anakin become "more machine than man."

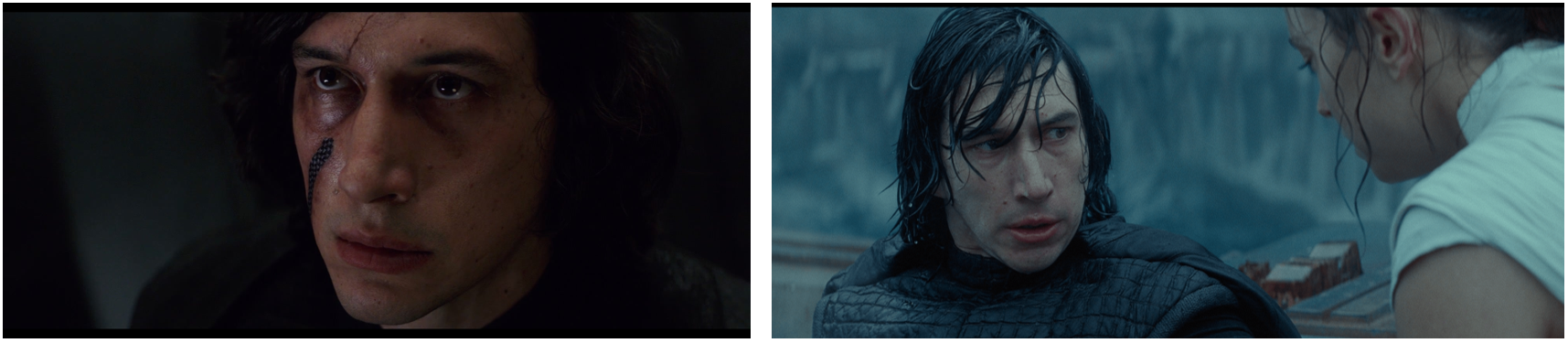

While Finn gets cured, Kylo Ren gets scarred in the right side of his face (reminiscent of Anakin Skywalker) during his fight with Rey, the morally upstanding hero of the Force Awakens trilogy. This scar remains prominent when Kylo fires up planet destroyers, but then is depicted as decreasing in visibility by the work of cosmetic medical machinery. At these moments of decreasing visibility, Kylo is depicted as having increased resistance towards the Dark Side. His scar decreases in prominence as a result of his quest to turn farther away from villainy. This is depicted in full in The Rise of Skywalker when Kylo stops fighting Rey. 91 Rey lashes at him with her saber, but later heals him, feeling that there was still an opportunity for redemption in him. As she heals the saber wound, his facial scar completely disappears, and shortly after, Kylo throws his Sith saber away and turns to the Light Side. Kylo is deserving of healing and curing because of his new morality, giving rise to the notion that the object and form of deformity/disability is to the meaning and signified concept of the Dark Side.

Figure 11. Illustrated in the left photo is Kylo as a Sith, his facial scar prominent on the right side of his face. Kylo has a thin red scar on the top of his forehead going into his eyebrow, and then a wide red and black scar from his eye to the bottom of his face. Pictured on the right is Kylo healed of his lightsaber scar moments before abandoning the Dark Side, his face now free of any scars as Rey, a woman with brown hair and a white fighting outfit, stands next to him. (Copyright 2019, Lucasfilm)

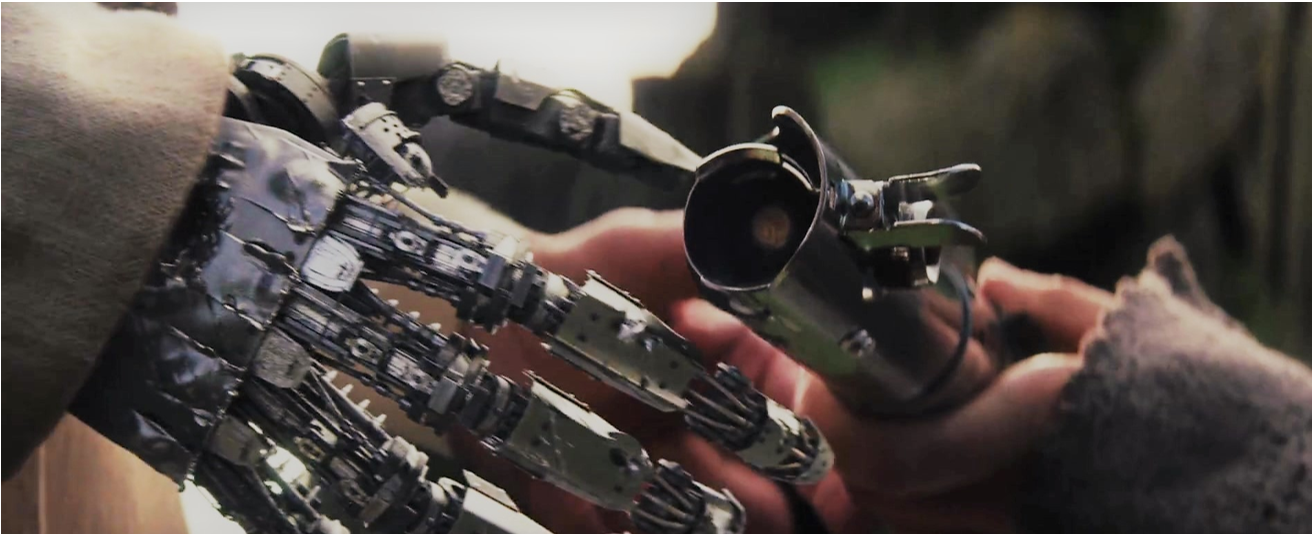

The character of Luke Skywalker follows a similar pattern to Kylo. Luke loses a hand to Darth Vader and refuses to accept Vader's request for him to join the Dark Side. When rescued by his friends, Luke later gets a robotic hand that looks exactly like a real hand in The Empire Strikes Back. As Luke does not come to be a signifier to the signified concept of villainy, he is able to have a technological advancement that at least visually erases disability. Unlike Anakin, whose bionics and technology are ingrained in his image as Darth Vader, Luke is able to have access to products that distract from his disability and visually seem to pause his new corporeality with a bionic limb. This echoes Norden's Techno-Marvel wherein disability seems to be erased upon technological advancements. 92 In Star Wars, however, this curing is given for heroic characters as opposed to evil ones, as Luke can have a "normal" looking hand while Anakin has "loose wires." 93

Figure 12. Depicted on the left photo is Luke as he gets his hand severed off by Vader. Luke is throwing his head back in pain, as his right hand (leftmost in the picture) is sliced off and shown falling from the air. On the right photo is Luke's robotic replacement, strikingly similar in look to a real human hand. His hand is exactly as his natural, former hand made of flesh, as the wrist area is shown with wires. (Copyright 1977, 1980; Lucasfilm)

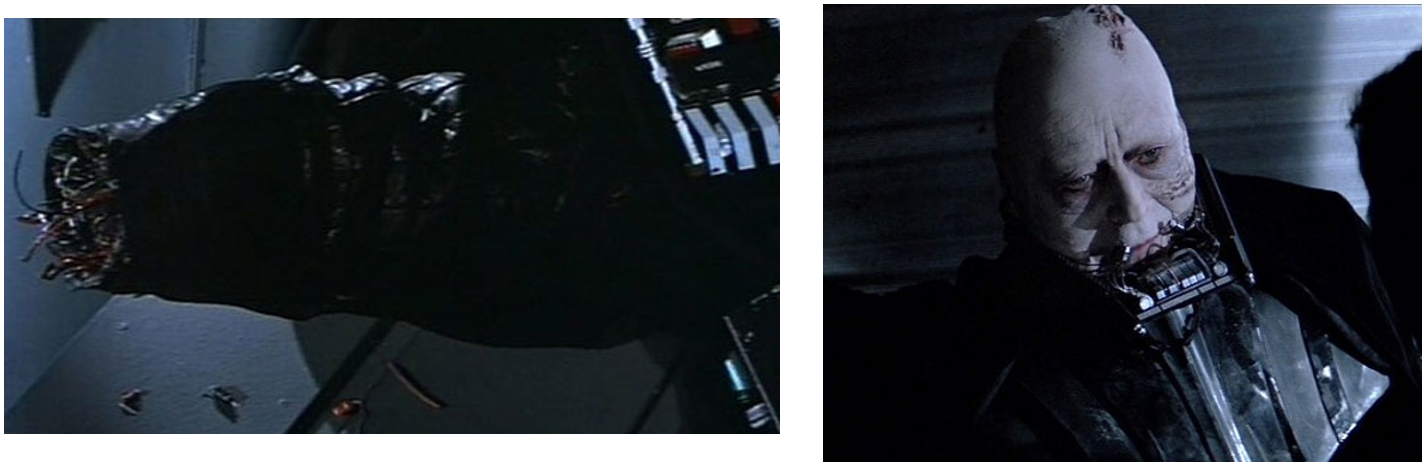

In Return of the Jedi, when Luke confronts Vader again, Vader provokes Luke into turning to the Dark Side by threatening his sister, Leia. In a fit of unbridled rage, Luke fights Vader and chops his arm off. Upon the arm falling down, Luke notices it is a robotic limb. It is then that Luke stops his attack, studies the arm, glances at his own robotic limb, and stops his fighting altogether. This scene can be analyzed as a point where Luke realizes both him and his father have more similarities than expected. The look of the castrated arm jolts Luke's realization that he too can have the same fate as his father, to be reduced to a "machine," if he continues to fight and give in to the darkness. Disability here has a critical functioning: had it not been for the image of the robotic hand, it is possible that Luke would have given in to his rage, killed his own father, and descended upon his own demise to the Dark Side and followed a similar storyline in the myth creation of disability with villainy as described through Anakin and Palpatine. However, the robotic limb acts as a point of realization for Luke, stopping him from giving in to rage and violence.

This scene is especially significant because after Luke stops trying to fight Darth Vader, Palpatine commands that Vader kill Luke. Rather than acquiescing to Palpatine's demands, however, Darth Vader instead sacrifices himself for his son. Vader gains personal redemption by throwing Palpatine off an enclave in an effort to kill him and save Luke, the hero. At Vader's consequent death scene, he asks Luke to help him remove his own helmet, which allows the observer to see the face of Anakin without his robotic mask. This scene is powerful by positioning the viewpoint of Vader's human face with its scars and deformities, alongside a powerful redemption scene. It is one of the first scenes where the image of deformity and physical disability is connected to love and redemption rather than violence, evil, and the developed myth-process where the form of disability represents the Dark Side as a symbol. However, shortly after Anakin's death, when he appears as a Force Jedi, he appears not in the form he died, but rather as the original able-bodied Anakin before his descent to darkness. Although Anakin's redemption scene is powerful in linking Anakin's image with that of love, having Anakin appear in the Light Side's afterlife as the able-bodied man he once was, rather than the disabled man he died as, is reductive in its positive imagery.

Figure 13. Pictured above, in the left photo, is Vader's severed hand that causes Luke to re-evaluate fighting him and giving into the same Dark Side his father once did. The picture depicts wires poking out of the area that remains on Vader that was just sliced. Upon Vader's personal sacrifice for Luke, he asks to have his mask removed, showing the first depiction of Anakin without his suit, shown through the right picture. Here, he is shown with a very pale hue to his face, scars alongside the bottom of his eyes and top of his head, and the bottom of his suit touching his mouth. (Copyright 1983, Lucasfilm)

Referring back to the sliding scale of disability, in the new trilogy The Force Awakens, Luke's robotic hand appears in moments of moral ambiguity and darkness. When Rey asks him to train her, he grabs the saber and refuses to do so, this scene highlighted by a very robotic looking hand. When it is shown that Luke had tried to kill Kylo in a flashback scene, again Luke is shown with his bionic hand, a hand positioned on the saber meant to kill his own nephew. However, in moments where Luke is a hero, such as in The Last Jedi when he fights Kylo Ren and the Dark Side in order to protect the Resistance, his robotic hand is covered in a glove. 94 In The Rise of Skywalker, too, when he appears as a Force ghost after his death, his robotic arm is tucked beneath his robes— if present at all. 95 Therefore, the connection of the signifier of disability to the signified concept of evil and moral ambiguity still continues to persist even within the new films in the Force Awakens trilogy, where disability is highlighted in terms of Darkness and minimized with Lightness.

Figure 14. Illustrated is a pan in on Luke's robotic grey hand in the latest trilogy, The Force Awakens, as he takes a grey lightsaber from Rey's flesh hands. Luke's hands' bionic nature tends to be portrayed more heavily during scenes of his own moral ambiguity. (Copyright 2017, Lucasfilm)

That being said, although in these examples the signifier of disability, the signified of evil, and the sign of a disability-connected evil exists, it is important to highlight how Luke, Darth Vader/Anakin, and Kylo Ren all die heroes. Although each differs in how much darkness and evil they had perpetrated and encapsulated throughout their lifetimes, it was Luke who had destroyed the Empire, Vader who had saved his son and risked his life to try killing Palpatine, and Kylo Ren who helped defeat the Sith and risked his life for Rey. Although these depictions warrant a critical viewpoint and analysis into the mythology of disability and the Dark Side in the film series, it is important and paramount to also realize how these characters are saviors and heroes as well. These characters are also powerful Force users, despite their lack of limbs and disabilities. It can be admirable then that regardless of one's dis/ability, anyone may be powerful with the Force. The Force does not discriminate. 96 , 97 This can be a powerful image for viewers, both those with robotic limbs and disabilities and those without.

Movement Towards Positive Change: Disability's Complex Embodiment

As analyzed thus far, the image of disability in Star Wars has a high linkage to the symbolism of the Dark Side and the series' differentiation of virtue and immorality. However, within the standalone Rogue One film, an exploration of Tobin Siebers's theory of complex embodiment can be applied to the images of disability. 98 Siebers highlights how complex embodiment "understands disability as an epistemology that rejects the temptation to value the body as anything other than what it was and that embraces what the body has become and will become relative to the demands on it, whether environmental, representational, or corporeal." 99 This theory applies a multidimensional outlook to the experience of disability, combining medical and social models to represent disability as a complex lived experience. Similarly to the Sieber's concept of complex embodiment is one of Jay Dolmage's anmut which "acknowledges the complex relationship between reality and representation." 100 Anmut "offers a way to reconsider disability- not as something an audience will reject or stigmatize, but as something that a diverse audience is receptive to and accepting of." 101

In Rogue One, depictions of disabled characters progress by rendering more developed images of disability, although they still have room for further improvement. 102 In this film, portrayals of disabled characters differ from previous ones. A prominent example of this is Chirrut Imwe, Star Wars's first blind character. Chirrut is seen with a walking stick, which he utilizes not only to help him better understand his surroundings, but also as a tool to fight and protect himself. He claims to have the Force, the only character in the movie who makes mention of it. During a scene where stormtroopers try to imprison Cassian and Jyn, the two protagonists, Chirrut hears of the encounter and tells the stormtroopers to "let them pass in peace." The stormtroopers try to discredit and aim to insult him by uttering "he's blind… is he deaf?" in an effort to publicly humiliate him by using blindness and now deafness as markers to be ashamed of. However, Chirrut refuses to respond and when they try to engage him, he fights with his walking stick, the tool for his blindness. By utilizing his walking stick as a weapon of defense, he reasserts his identity as a person with blindness. When stormtroopers later capture Chirrut, he has enough self-assuredness to joke at the circumstance at hand, not as a detriment to himself, but at the event and power-hungriness of the stormtroopers. When the stormtroopers capture Chirrut, they place a bag over his head to which Chirrut replies "Are you kidding me? I'm blind!"

Chirrut's character continues to be developed through him continuously making note of the Force and using it as not only a guide, but also a mode of strength. At the end of the film, Chirrut walks towards a data transmitter that could help spread information on how to destroy the Death Star and turns it on, while utilizing the Force to protect himself. When on the way back he dies in the process, he dies a hero, and his best friend, Baze, starts to believe in the Force. When Baze is about to die as well, he looks at peace with the prospect upon realizing that Chirrut does not die alone. This portrayal of Chirrut embraces aspects of complex embodiment: Chirrut's blindness is an aspect of himself that extends from within the body to outside in his society. The physical nature of his blindness is never ignored, but just as similarly the societal aspects of it are highlighted as well. Chirrut is a character who is comfortable enough with himself that he can find humor in his situation, uses a tool meant primarily for disability as an additional tool for protection and power, is strong with the Force, loved by a friend, included within his group, and dies a hero. His character is developed and is memorable for his spirituality, humor, and strength.

Chirrut exhibits armut as well in the "acknowledge[ment of] the impossibility of representing embodied experience with perfect accuracy (or rather, with predictable aesthetic effects) while simultaneously valuing the importance of representation… as important means of communication about and imagining embodied experience." 103 Chirrut's body is envisioned as a full and alive phenomenon, where his disability contributes to his entire character.

Although Chirrut has been noted to have semblances of Martin's Supercrip and also of the Saintly Sage, he is not portrayed as helpless as typical depictions of blindness usually entail. 104 , 105 The Supercrip stereotype usually describes a "disabled person who can accomplish mundane, taken-for-granted tasks as if they were great accomplishments" or as the performance of "highly extraordinary deeds- climbing a mountain, sailing the ocean." 106 These can be potentially harmful since it focuses on individual achievement, which can imply "that those who do not achieve these superhuman actions lack self-discipline and willpower." 107 As for the Saintly Sage archetype, which is described as usually being "a pious older person with a disability (almost always blindness) who serves as a voice of reason and conscience in a chaotic world," this archetype— similar to the Supercrip —suggests that "disability is not socially constructed, but is equivalent to a physical impairment which can and must be overcome by resolute dedication." 108 , 109 These representations can be harmful as they promote the idea that for a disability to be acceptable in a person, one must do what those without disabilities can, and even sometimes can't, do. The disability is not acceptable as a state of its own, but a state for what it supposedly does for the characters in these archetypes. Rather than the promotion of self-acceptance in general, these archetypes lead to the belief that for disability to be a positive trait, it must somehow extend beyond the realm of standard human ability and have one-of-a-kind abilities (having incredible foresight, the ability to see beyond what is around us, and more).

However, "given the level of technological advancement in the film, it seems that restoring Chirrut's eyesight would be a realistic possibility. Therefore, one might speculate that Chirrut actively chose to remain blind rather than become able-bodied." 110 Although his depiction is imperfect and has tendencies of these two tropes, the movement towards a complex embodiment of disability and an embrace of the concept of anmut shows improvements within the universe. Advancements could still be made, as both aspects of both tropes can be harmful for individuals with disabilities, but these advancements are large steps in a positive direction.

Figure 15. Depicted above is Chirrut Imwe, Star Wars' first blind character. On the left, Chirrut is in the center of the screen as fire sparks behind him. He carries a grey and black walking stick and he is blind in both eyes. On the right, Chirrut is pictured in the middle of the screen, fighting one stormtrooper with his walking stick and one with his hands. (Copyright 2016, Lucasfilm)

Although Rogue One progresses in its image of disability with Chirrut's complex embodiment, it backtracks in disability-positive portrayals through the character of Saw Gerrera. The audience is first introduced to Saw through the image of his robotic legs moving forward, the camera running up his body from robotic-to-human parts, making disability the object for a scopophilic gaze. 111 Similar to Anakin, Gerrera's prosthetics and cyborgization is purposely panned in on to invite the audience member to notice his difference. Rather than depict Gerrera as a whole individual and his disability as a part of him, the scopophilic camera does the opposite. His disability is highlighted, and his disability becomes prioritized for the reader to see, while he as a whole individual comes last. This positions Saw Gerrera's body in the forefront, and his character and individuality as the afterthought. The camera work inspires what Mulvey describes as "to-be-looked-at-ness," where disability is the spectacle. 112 He is depicted as having a mask which provides him oxygen, walking with a cane, and wearing a robotic suit that covers his body except for his head. When he believes Jyn (the protagonist) has come to kill him, he tells her, "[but] there's not much of me left," referring to his disabilities. He himself characterizes his disabilities as diminishing his personhood. He acts as a mode to help Jyn on her hero's quest, yet at the moment when there is danger and impending doom for the characters, Saw Gerrera gives up on life. He elects to stay on his crumbling planet and exclaims, "I will run no longer." Gerrera's depiction is categorized in the "better left for dead" trope and exists as an extension of the hero's journey. Although important to note that had it not been for Saw Gerrera, Jyn's journey and the eventual destruction of the Death Star may never have come to be, this portrayal is a step backward from the one of complex embodiment in Chirrut Imwe.

Figure 16. Illustrated above is Saw Gerrera, leader of a sect of Rebellion fighters. Pictured above, to the left, are his robotic grey feet and the bottom of his walking stick. To the right, Saw is portrayed holding his brown walking stick in hand as he wears a heavy duty black and grey suit that holds an oxygen tank. (Copyright 2016, Lucasfilm)

Conclusions

The Multidimensionality of Images: Villains, Cyborgs, and Complex Embodiments

In Star Wars, disability's symbolism varies. From being engrained in the Dark Side, linked to the technological aspects of the universe, or portrayed as a multidimensional lived experience, disability in Star Wars follows patterns of traditional archetypes and representations yet is also part of an effort for the creation of new images of disability in the universe. Disability representations as a whole have room for improvement, but it is important to note the complexities between even the most problematic representations of disabled characters such as Darth Vader/Anakin Skywalker, to their functions as heroes and saviors of this universe.

Star Wars simultaneously adheres to traditional stereotypes and regressive images of disability, while working toward surpassing boundaries through the heroism and growth disabled characters portray, and the complex embodiment of disability recently gaining exploration in the films. These changes are a result of time, changes in cultural attitudes, and even differing visions under different leadership, as Disney recently acquired LucasFilms and diverged from the planned direction of the films (Bob Iger, Disney's CEO describes how George Lucas, the creator of the series, "talked about his frustration that we hadn't followed his outlines" and "it dawned on him that we weren't using one of the stories he submitted during the negotiations…. He thought that our buying the story treatments was a tacit promise that we'd follow them"). 113 , 114

As "popular culture.. shapes us, reinforcing certain attitudes and beliefs and revising others through repetitive messages," further growth in the way disabled characters are depicted can induce positive changes in cultural and societal viewpoints for those with disabilities. 115 In the words of Mark Hamill, "remember, Luke lost his hand to Vader, but that didn't stop him from defeating the Empire." 116 The creation of positive, well-informed, and multifaceted images of disability is not only beneficial to the complexity of the film itself. For those watching, diversified representations of disability can provide a long-lasting impact regardless of the ability of the viewer. As influential and critical Disability Studies scholars Brenda Jo Brueggemann, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, and Georgina Kleege highlight through their experiences as academics and women with disabilities, "both students with disabilities and students without disabilities see a person with a disability in a position of authority, and, without having to say anything about it, it's a way of demonstrating that one can have authority and an intellectual life and a career and all these things." 117 Similarly, when representations of disability in film strive to highlight the multidimensionallity of disability and challenge ingrained stereotypes, larger social change can occur that benefits individuals both with and without disabilities. Through fantasy, viewers can have a site "which one's own fears, needs, and desires are projected," which in time will hopefully include increased positive projections from and of people with disabilities. 118

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the University of Connecticut's Holster Scholarship for providing me the support, time, and encouragement needed to complete this research. I am also indebted and grateful to Dr. Brenda Jo Brueggemann, who provided her feedback, expertise, mentorship, and friendship throughout the research project. Without both, my project would not have been possible.

Bibliography

- Arp, Robert. 2005. "'If Droids Could Think …': Droids as Slaves and Persons." In Star Wars and Philosophy: More Powerful Than You Can Possibly Imagine., 120-131. Chicago, Illinois: Open Court.

- Barthes, Roland. 1972. Mythologies. New York: Noonday Press.

- Baseel, Casey. 2019. "Wheelchair Fraudsters Fake Disabilities at Tokyo Disneyland." Japan Today. https://japantoday.com/category/national/wheelchair-fraudsters-fake-disabilities-at-tokyo-disneyland.

- Beauchamp, Miles, Wendy V. Chung, and Alijandra Mogilner. 2014. "Disabled Literature— Disabled Individuals in American Literature: Reflecting Culture(s)." Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal 6, no. 1 (November): 1-17.

- Beecher, Bill J. 2018. "Superheroes in a Silent World: Hawkeye and El Deafo." In The Image of Disability: Essays on Media Representations, 44-60. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc.

- Brian, Greg. 2020. "Some Fans Noticed a Clever Detail in 'The Rise of Skywalker' Involving Luke's Missing Hand." Showbiz CheatSheet. https://www.cheatsheet.com/entertainment/some-fans-noticed-a-clever-detail-in-the-rise-of-skywalker-involving-lukes-missing-hand.html/.

- Brueggemann, Brenda J., Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, and Georgina Kleege. 2005. "What Her Body Taught (or, Teaching about and with a Disability): A Conversation." Feminist Studies 31, no. 1 (Spring): 13-33. 10.2307/20459005. https://doi.org/10.2307/20459005

- Buckley, Cara. 2020. "For the Disabled in Hollywood, Report Finds Hints of Progress." The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/05/arts/television/disabled-hollywood.html.

- Cattell, Alec. 2018. ""Hopefully I Won't Be Misunderstood." Disability Rhetoric in Jürg Acklin's Vertrauen ist gut." Humanities 7, no. 3 (July): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030071

- Church, David. 2006. "Fantastic Films, Fantastic Bodies: Speculations on the Fantastic and Disability Representation." Offscreen 10, no. 10 (October). https://offscreen.com/view/fantastic_films_fantastic_bodies.

- Covino, Ralph. 2013. "Star Wars, Limb Loss, and What It Means to Be Human." In Disability and Science Fiction: Representation of Technology as Cure, 103-113. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137343437_8

- Coyne, Sarah M., Jennifer R. Linder, Eric E. Rasmussen, David A. Nelson, and Victoria Birkbeck. 2016. "Pretty as a princess: Longitudinal effects of engagement with Disney Princesses on gender stereotypes, body esteem, and prosocial behavior in children." Child Development 87, no. 6 (June): 1909-1925. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12569

- Davidson, Michael. 2003. "Phantom Limbs: Film Noir and the Disabled Body." GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 9 (1-2): 57-77. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-9-1-2-57

- Diken, Ibrahim H. 2006. "Turkish Mothers' Interpretations of the Disability of Their Children with Mental Retardation." International Journal of Special Education 21 (2): 8-17.

- Dolmage, Jay. 2014. A Repertoire and Choreography of Disability Rhetorics. Syracuse: Syracuse U.

- Donnelly, Colleen E. 2016. "Re-visioning Negative Archetypes of Disability and Deformity in Fantasy: Wicked, Maleficent, and Game of Thrones." Disability Studies Quarterly 36 (4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v36i4.5313

- Forbes, Bruce D. 1999. "Battling the Dark Side: Star Wars and Popular Understandings of Evil." Word & World XIX (4): 351-363.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1957. "A Special Type of Choice of Object Made by Men." In The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, 163-175. London, England: Hogarth Press.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1961. "Beyond The Pleasure Principle." 1856-1939. New York: Liveright Pub. Corp.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1961. "'The Dissolution of the Oedipus Complex." In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud: Vol.19 (1923-1925), Ego and the Id, and Other Works, 173-179. London, England: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis.

- Freud, Sigmund. 2004. "The Uncanny (1919)." In Fantastic Literature: A Critical Reader, 74- 101. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

- Germaine, Alison E. 2016. "Disability and Depression in Thor Comic Books." Disability Studies Quarerly 36 (3). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v36i3.5015

- Groce, Nora, and Julia McGeown. 2019. "Witchcraft, Wealth and Disability: Reinterpretation of a folk belief in contemporary urban Africa." Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre Working Paper Series 30 (June). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3398227.

- Harrison, Mia. 2018. "Power and Punishment in Game of Thrones." In The Image of Disability: Essays on Media Representations, 28-43. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc.

- Henderson, George, and Willie V. Bryan. 1997. Psychosocial Aspects of Disability. Springfield, Illinois: Thomas.

- Hevey, David. 2006. "The Enfreakment of Photography." In Disability Studies Reader, 367-378. New York: Routledge.

- Hoffmann, Ada. 2019. "Disability in Star Wars." Ada-Hoffmann.com. http://www.ada-hoffmann.com/2019/07/28/disability-in-star-wars/.

- Iger, Bob. 2019. The Ride of a Lifetime: Lessons Learned From 15 Years as CEO of the Walt Disney Company. New York: Random House.

- Kirkpatrick, Stephanie R. 2009. "THE DISNEY-FICATION OF DISABILITY: THE PERPETUATION OF HOLLYWOOD STEREOTYPES OF DISABILITY IN DISNEY'S ANIMATED FILMS." The University of Akron.

- Kurka, Rostislav. 2018. "From Dark Side to Grey Politics: The Portrayal of Evil in the Star Wars Saga." In A Shadow Within: Evil in Fantasy and Science Fiction, 169-188. Edinburgh: Luna Press.

- Livneh, Hanoch. 1980. "Disability and Monstrosity: Further Comments." Counselor Education Faculty Publications and Presentations 41 (11-12-): 280-83.

- Lodder, Bart. 2017. Are they monsters or entertainment? The position of the disabled in the Roman Empire. Leiden, Netherlands: Leiden University Master Thesis.

- Longmore, Paul. 1987. Screening stereotypes: Images of disabled people in TV and motion pictures. New York: Praeger.

- Lopez, Ricardo. 2017. "Women and Non-White Characters Are Speaking More in Recent Star Wars Movies." Variety. https://variety.com/2017/film/news/star-wars-diversity-dialogue-bechdel-test-rogue-one-1202633473/#article-comments.

- Madi, Sanaa M., Anne Mandy, and Kay Aranda. 2019. "The Perception of Disability Among Mothers Living With a Child With Cerebral Palsy in Saudi Arabia." Global Qualitative Nursing Research 6 (January): 1-11. 10.1177/2333393619844096. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393619844096

- Matt, Susan B. 2015. "Perceptions of Disability among Parents of Children with Disabilities in Nicaragua: Implications for Future Opportunities and Health Care Access." Disability Studies Quarterly 34 (4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v34i4.3863