This article investigages the annual #BellLetsTalk mental health awareness campaign through the lens of critical disability studies. Created by the telecommunications company Bell Canada, the campaign encourages social media users to share, promote, and like posts about Bell, mental health, and hyperindividualist narratives of overcoming disability and illness. However, delving deeper into the archive uncovers dissenting crip voices that resist Bell's hegemonic narrative of wellness and cure. Focalizing my analysis around a sample of 5000 tweets (including 2093 unique tweets) from the 2018 campaign, I identify distinct disabled networks emerging around the hashtag on Twitter/X: 1) feminine therapeutic networks, 2) masculine sick publics that retain an attachment to capitalism and nationalism, and 3) queer communities that keep company with ghosts. Furthermore, I identify users deliberately disidentifying with the network and occupying the role of the killjoy or "bad" avatar. This article articulates an ethical, hybrid qualitative and quantative method for working with data.

Content warnings: This article references important and difficult topics including domestic violence, abuse, sexual violence and self harm. However, this article does not discuss these topics in-depth. One sub-section of this article discusses suicide at length. This section is bookended by text in italics both introducing and appending the topic.

Hashtag Health Nation

I'm staring at an Excel sheet that holds 5000 tweets. They're not all unique tweets; sometimes I scroll through several cells of "today, for every tweet and retweet using #BellLetsTalk, Bell [corporation] will donate 5¢ to #mentalhealth initiatives in Canada. Join!" Other times my eye catches on a word like "suicide" or "fucking" and the scrolling stutters or stops. I'm pulled into the tweets that use all caps or too many exclamation marks: the people yelling into the void of cyberspace. When I read more carefully, I stumble over moments of sarcasm puckering the smooth skin of a corporate hashtag. This is the collective and collaborative digital life-writing text I have created, pieced together using Python, Excel and OpenRefine, to connect a communications corporation (Bell Canada), a social networking site (Twitter 1 ), and hundreds of (here, anonymous) authors that tweeted, retweeted, and favourited #BellLetsTalk on Wednesday, January 31st, 2018. 2

It's an interesting and incredibly complicated archive. The peppy energy of a car-wash fundraiser and saccharine clichés about love and healing crash painfully into tweets about exhaustion, insomnia, forgetting to take your medication, financial struggles, domestic abuse, and sexual violence. Generic claims about how mental illness "doesn't discriminate" sit uncomfortably beside tweets about gendered violence. Hearts and smiley faces punctuate the text, trying—and often failing—to make the overarching story uplifting and heartwarming. Instead, it's heartworming, burrowing into my body. I am relieved that none of the tweets I collected were authored by people I know. Still, I know many people who did tweet and retweet #BellLetsTalk, and their presence hovering around the archive—some brutally, vulnerably personal, others in the careless vein of well-meaning tourists—is a bruise. When I press on it, it hurts.

Bell Let's Talk is an annual mental health awareness campaign run by Bell Communications Company in Canada. This national campaign is cross-platform: for each tweet that uses the hashtag #BellLetsTalk, for every Bell Let's Talk video watched on Instagram or Facebook, for every text sent on a Bell Canada phone ("turn off imessage!"), Bell will donate five cents to "mental health initiatives." Bell has developed Instagram filters and Facebook profile picture frames for this initiative. Bell Let's Talk functions as a PR campaign positioning Bell as a caring corporation, provides exceptional advertising for Bell, and contributes to the project of national identity building. My analysis is based on the 2018 campaign.

In Robert MacDougall's comparative study of the development of telephone systems in the United States and Canada, he writes that in Canada, the Bell Telephone Company became "to some extent…an agent of national unity" (16). I want to connect this historical thread of nationalism in the development of communication technologies to Bell Canada's contemporary use of digital media to reinforce a particular image of national identity and belonging: one that is predominantly white, settler colonial, able-bodied, and cisheteronormative. "So keep talking, keep posting, and let's make a difference," announces Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in a video featured on the Bell Let's Talk's homepage. Trudeau was featured prominently in the 2018 campaign, while numerous Canadian celebrities promoted the campaign and offered themselves as examples of overcoming narratives. Employing the head of Canadian government to promote a charity campaign foregrounds the currents of power and hegemony prevalent in what Eli Clare calls the "ideology of cure" (3).

As I stare at the forty-six personal testimonies on the Bell Let's Talk webpage, I am hyper-aware of the threat of electroshock therapy (ECT), institutionalization, and treatment without consent pulsing behind the smiling faces of cured Canadians. Twenty-three (50%) of Bell's personal stories include a positive experience with the psychiatric and medical industries, citing the value of therapy, medication, hospitalization, psychiatry, psychology, or a combination of these treatments. Still others celebrate the policing and prison industries. Emphasizing cure and overcoming rather than social justice and interdependency, Bell Let's Talk stakes a claim not only on the good Mad body deserving of citizenship and rights, but on the future of mentally ill bodies within a settler framework that seeks to "make a difference" by eradicating difference.

Bell Let's Talk uses Trudeau as a symbol of aspirational national identity, a position Mad and disabled people have long been told that we, too, can earn, if only we take our medication and accept the painful and demanding love of the settler state. This campaign promotes cure, apolitical self-care, and maintaining wellness and health (often explicitly to avoid absenteeism at work.) There is no mention of access, collective care, or disability justice, and certainly no mention of discrimination, sanism, or ableism. Behind Trudeau's white smile, the genocidal project of settler colonialism is carried out—we kill land, language, and lives; encourage the harmed to speak their pain so that we might listen, and then celebrate ourselves for the goodness of saving small pieces of dirt.

Turning toward the #BellLetsTalk hashtag itself, a constellation of feelings, objects, and practices emerged around the words "good" and "bad," highlighting the dominant ideologies of the campaign. Good: Bell's campaign, crying, sports players, people who have died from suicide, people who are good for your mental health, people, days, nights, things, times. Bad: mental health, cell reception, days, times, things. The most "good" object and practice were the Bell campaign and hashtag, while the most "bad" objects were time periods and feelings. While "good" is used here to assign moral value to the network (and its good, i.e., technologically and socially-savvy, users), "bad" refers obliquely to experiences of madness/mental illness. This brief analysis is intended to provide readers with an understanding of the overarching framework of the campaign: that mental illness is bad and needs to be eradicated, and that mental health is good and worth attaining, typically through positive thinking, talking to a friend, tweeting on Bell Lets Talk day, and/or psymedical interventions. Welcome to the #BellLetsTalk project of Canadian national mental health.

In #HashtagActivism, Sarah J. Jackson, Moya Bailey, and Brooke Welles argue that those who "have long been excluded from elite media spaces…have repurposed Twitter in particular to make identity-based cultural and political demands" (xxv), a claim I take up in my exploration of Mad/disabled networks. Nathan Rambukkana identifies these networks as "hashtag publics" (29), and while he focuses on the publics of race activism, the tensions brewing around #BellLetsTalk can also be suggestive of "the kinds of publics that do politics in a way that is rough and emergent, flawed, and messy" (29). It is important to keep in mind the different types of networks that are at play in these identity acts, some less visible (reading without responding; favouriting; retweeting) some more visible (responding, tweeting using the same hashtag), but all engaged in the production of online identity and community. While the use of a corporate hashtag is distinct from the creation of an activist hashtag, there is still merit in recognizing the way marginalized people intervene in dominant public conversations on social media. In this paper I explore the Mad/sick/crip counterpublics that emerged through #BellLetsTalk, drawing attention to individuals and communities that resisted, subverted, and at times explicitly critiqued Bell Canada and mental health charity campaigns more broadly.

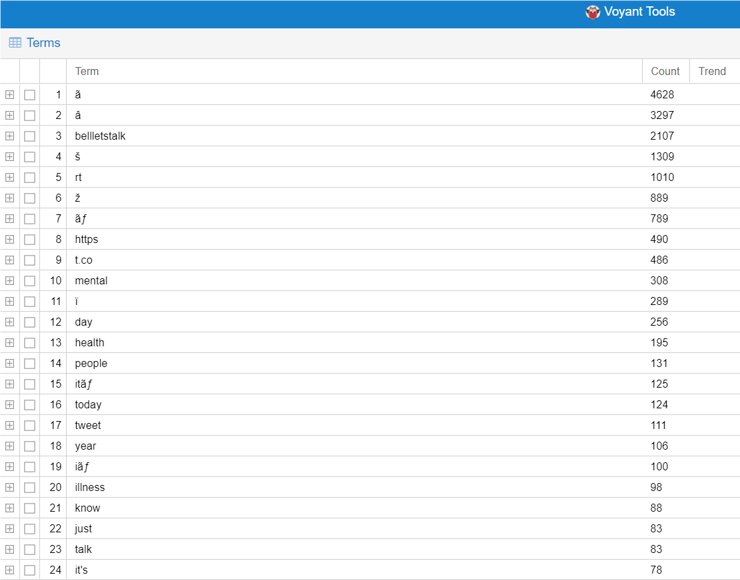

Of the 5000 tweets I analyzed for this project, 912 were retweets (RTs) of Bell's official Twitter account @Bell_LetsTalk with no additional content, 220 simply stated "#BellLetsTalk," and sixty were RTs of celebrity spokeswoman and Olympian Clara Hughes. Of the users who did append their own sentences to the hashtag, the most recurring words included "rt" (1010), sometimes because I have captured a retweet; in other cases, users were encouraging each other to retweet. RTs are an important function of Twitter: not only do they denote another level and type of participation, but popular tweets rise to the top of the page and are promoted as the "Top" tweets. Less retweeted and liked tweets get buried and are harder to find. While Twitter users can select "Most Recent" as an organizing principle, the default is "Top" (i.e., most popular). It's also worth noting that the Twitter algorithm tries to predict what tweets a user will most likely interact with based on past interactions, a process which makes it less likely that users will encounter dissenting or unique utterances.

With almost twenty percent of the tweets dominated by Bell, the message of the benevolent corporation dominates. Users are encouraged to share and promote Bell, as well as to disclose their own experiences of mental and emotional distress, often in the form of overcoming narratives and expressions of gratitude. While the corpus of #BellLetsTalk tweets is primarily narratives of overcoming, self-management, hyperindividualism, and the moral value of tweeting, the messiness and discomfort of Mad/crip bodies emerge from under the glossy veneer of prescriptive wellness. Sifting through the dataset uncovers Mad/crip testimony and kinship. For many Mad and crip bodies, this type of activism, care work, community-building, and public identity performance is much more accessible than take-to-the-streets or other offline tactics (Al Zidjaly 2011; Hedva 2016; Mann 2018).

However, while some of these networks queer/crip the hashtag in disruptive ways, other performances of bad/Mad/sad re-enact troubling attachments to markers of the settler colonial project: whiteness, toxic masculinity, and nationalism. This article moves through these networks affectively from feelings of belonging along multiple axes of kinship to feelings of isolation and the avatars that struggle to disidentify with the networks that seek to claim them. This process can also be read as peeling back the layers of the hashtag, from the more easily accessible (and shareable, likeable) performances to the more submerged (and less shareable, likeable) performances within these networked publics.

Digital Research Methods

Labor, Failure, and Creativity

This paper uses algorithms in tandem with close-reading, and computer processes in collaboration with visual and textual analysis. Digital humanities (DH) tools enabled me to collect Twitter data and to clean and assemble the text that I identify as collective automedia. Between January 26 and January 31, 2018, I used Python and Twitter APIs to collect several gigabytes of tweets that all used the hashtag #BellLetsTalk. I collected the data directly to one of the PCs at the Sherman Centre for Digital Scholarship at McMaster University. Understandably, the file wouldn't fit on my thumb drive and could not be easily transferred to my personal PC. I attempted to open the document in OpenRefine 3 in order to move to the first stage of cleaning (translating JSON to CSV). However, the file was so large that the browser kept crashing (often after attempting to load for twenty minutes). Nor would the file fit in a single Excel sheet or Google Sheet. I was faced with the hard limits of programs that can only handle so much data at any one time, and the reality that collecting tweets also involves collecting far more metadata about the tweets and the user than I needed or wanted.

I took a manual approach to narrowing down the scope of the project, which allowed me to understand how the data were being changed, cleaned, lost, and transformed through algorithmic processes and human labor. I was able to successfully open the JSON file in Atom 4 . From there, I was able to copy and paste a selection of the data into a Google Sheets file (5000 tweets). Based on the size of the file and my own limitations for this project, I focused on tweets posted between January 30-31. Switching to my personal laptop I translated fifty rows (tweets) at a time using a JSON → CSV converter online 5 , saving the data in folders as sets of 1000. I then worked on one file at a time, copying and pasting the metadata I wanted (from the columns of metadata that the API collected) into a single Google Sheet. The metadata I saved included location, when the tweet was created (or retweeted), and the number of favourites, retweets and replies at the moment of collection. Finally, I created a separate document for the tweet corpus itself. I opened this sheet in OpenRefine and deleted the duplicate tweets.

From the original 5000 tweets I collected, I was left with 2093 unique tweets. Although I primarily worked with the unique tweet content for my analysis of Mad/crip networks, this paper is informed by both datasets. I detail this process not only for transparency, but also to make visible the embodied and exhaustive labor that goes into digital research and quantitative methods, the barriers to research, and the creativity, troubleshooting, and innovation that working with data requires.

Research Ethics

When collecting data from hundreds of digital bodies, it's impossible to obtain consent from each user. However, it is possible—and necessary—to undertake this research in an ethical and non-exploitative manner. My work with quantitative research and data collection shares the concerns of the authors in the edited collection Good Data. According to the editors, Angela Daly, S. Kate Devitt, and Monique Mann, these researchers are invested in "articulating a more optimistic vision of the datafied future" by generating, discussing, and promoting "ethical data practices" (8). I am particularly indebted to Andrea Zeffiro's work in this collection on social media ethics, and I take seriously her argument that "researchers are responsible for protecting the privacy and anonymity of unknowing participants" (225). When I decided I wanted to scrape Twitter data to study #BellLetsTalk, I approached the McMaster Research Ethics Board. I was told that because Twitter is a public platform, and hashtagging is a public action, there would not be an expectation of privacy from the users of the hashtag. However, as Zeffiro reminds us, "simply because information is stipulated as 'public' does not absolve researchers of ethical concerns" (231). I would also remind readers that the landscape of social media evolves much more quickly than institutional bureaucracy, that many 'public' platforms are used in private, small, intimate, and community-building ways that do not anticipate an academic audience, and that digital avatars—and the people behind them—deserve to be treated with care and respect.

I was primarily concerned with protecting the anonymity of the users—my goal was to uncover patterns of feeling and Mad/crip networks, not to "out" a single user. I do not reproduce the username or any identifying information about the authors of the tweets. Furthermore, due to the searchability of tweets, this article will not reproduce tweets verbatim, but will focus on recurring words and, when necessary, explain the context that provides meaning to these words. The data have been saved on a computer at the Sherman Centre for Digital Scholarship behind two sets of passwords, and a copy of the data has been saved on my PC, which is also password protected. The metadata, which contains sensitive information, will not be made public.

Despite the many tools now available for performing digital scholarship, the full consequences of using these tools are unknown. The algorithms, the computer, the DH tools, the researcher, the corporation: there are many layers of transition, transformation, and curation that shape the final working archive, which is never complete nor neutral. In this overview of my dataset, I hope to illuminate the messiness and complexity of working with digital platforms, machines, and algorithms whose processes are not transparent. Of the 5000 tweets I initially chose, selected based on date and time (which translates into proximity in the dataset), 3641 were retweets. The presence of original tweets and retweets, as well as the range of tweets (from just the hashtag to a long narrative thread) point to the different forms and levels of engagement with the hashtag that inform this study. It's important to recognize that even within the "unique" tweets dataset of 2093 there is repetition, as I have frequently collected the original tweet as well as a single retweet, and/or a retweet with slight additions or alterations. The dataset is imperfect, incomplete, and very much curated by obsfucated algorthimic, digital processes and the choices I made as the researcher.

Collective Automedia

Digital media are typically discussed through metaphors of space, of chat rooms and virtual worlds. To enter we need to assume a form of digital embodiment. We enter digital spaces through the avatar, a term Beth Coleman uses to describe the act of "putting a face to things" online. She cites emoticons as early examples of digital avatars and moves on to discuss the video game avatar (54-55). On Twitter, the avatar is the visible face/body/person on-screen (often represented by a thumbnail image) that has a relationship with the invisible person behind the screen. It is through our digital avatars that we connect, protest, harm, and communicate with one another online.

Tweeting, or the production of what Laurie McNeill names "auto/tweetographies" ("Life Bytes" 144), is a form of digital life writing. Digital identify performance can also been referred to as "automedia," a term Emma Maguire uses to "denote diverse forms of media that present autobiographical performance(s) and which require close attention to the facts of mediation" (21). Through the iterative process of planning, failure, revision, and innovation, and guided by an attention to ethics, I assembled a collective automedial text as my primary object for analysis. Collective automedia shifts the focus away from individual avatars/Twitter users/speakers and towards networks, communities, and the circulation of madness and emotion through the hashtag.

This methodology takes inspiration from the disability justice concepts of "collective care" and "interdependency." Leah Lakshmi Piepzna Samarasinha describes collective care as a framework "where we actually care for each other and don't leave each other behind" (108); collective care is community-oriented and focused on mutual support. Collective care is inventive, creative, and non-normative; it can be small and disorganized; it understands the diverse needs of our "bodyminds" (Price 2015; Schalk 2018). The related concept of interdependency—as opposed to independency—recognizes that we need each other and rely on each other, and again focuses on communal, collective solutions and actions rather than individual ones. Mia Mingus writers that "interdependence moves us away from the myth of independence, and towards relationships where we are all valued and have things to offer" ("Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice"). Interdependency challenges the negative associations of dependency that are often associated with disability.

Social media emerge in an ableist, capitalist context that celebrate independency and self-care. In fact, social media coax users toward the confessional mode of life writing. McNeill writes that "auto/tweetography participates in a larger culture of digital self-help and normalizing that continue offline traditions of autobiography" ("Life Bytes" 152), noting that the "design and contest framework ensure that particular kinds of self-revelation take place that reflect popular understandings of memoir, particularly those that associate self-reflection with self-help, informed by therapeutic culture" (153). While McNeill focuses her analysis on the Six-Word Memoir, she extends her theorizing of social media to other platforms including PostSecret and Facebook, exploring the "exigencies of confession and therapy in microblogging genres" (157). PostSecret users operate within the genre of therapeutic confession (in which speaking or disclosing is understood as inherently curative) which is embedded within a framework of capitalist self-help (in which we are tasked with managing our own bad feelings in order not to disrupt work flows). Like PostSecret and the Six-Word memoir, the 280-character count of Twitter encourages revelation and confession that can limit identity exploration and self-expression, reducing complex experiences to simpler and more easily consumable identities. McNeill's connection between microblogging and self-help culture is particularly relevant for a hashtag like #BellLetsTalk, which actively encourages users to be publicly vulnerable, to share their feelings, and to speak openly about mental illness—as long as they are now healthy or becoming healthy. #BellLetsTalk ultimately claims Twitter as a therapeutic space for users with mental illnesses in their journey to become healthy/sane/able-bodied.

Generating a collective automedial text from the #BellLetsTalk corpus puts pressure on the confessional model of life writing and the hyperindividualism of Canadian settler culture. The archive I have assembled embodies Leigh Gilmore's concept of "limit-cases" which "produce an alternative jurisprudence within which to understand kinship, violence, and self-representation" ("Limit-cases" 134). While, as Gilmore notes, "memoirs and autobiographies struggle with the persistent legacy of confession that institutionalizes penance and penalty as self-expression" (137), my project resists the violence of these traditions by taking the confessional tweets encouraged by #BellLetsTalk and reframing them as networks and communities rather than singular avatars or authors. By refusing to make the Mad/crip avatar hypervisible by reproducing their words verbatim, I resist the confessional mode that demands total access to the speaker—which can open them up to harm. Instead, these collaborative utterances—many of them traumatic—are "testimonial projects, but they do not bring forward cases within the protocols of legal testimony" (134).

In bearing witness to the multiple voices engaged in the project of #BellLetsTalk, my methodology brushes up against Bronwyn Davies's concept of a "collective biography" that is "open, rhizomatic, and transformative" (Masschelein and Roach 257). Davies writes that:

In relation to your question as to whether interviewing is still relevant in the face of "big data," I can't imagine that it would ever be irrelevant to listen to people. What format that listening takes, and what interpretive work is done with what they have to say is, to me anyway, endlessly fascinating (262)

In assembling this life-writing text I have tried to listen, honour, and respect avatars, their real-world counterparts, and their hashtagged affects and bodies. While I do not use interviews in this article, my use of the program Voyant 6 to uncover less popular—but still present—feelings and critiques enacts a form of ethical encountering that recovers the voices of speakers whose words could easily be lost in a sea of data, drowned by quantitative approaches that equate "most popular" with "most significant." Instead, I pivot between popular and less popular, common and uncommon, sifting through the multi-authored collaborative #BellLetsTalk text for Mad/crip feeling and expression.

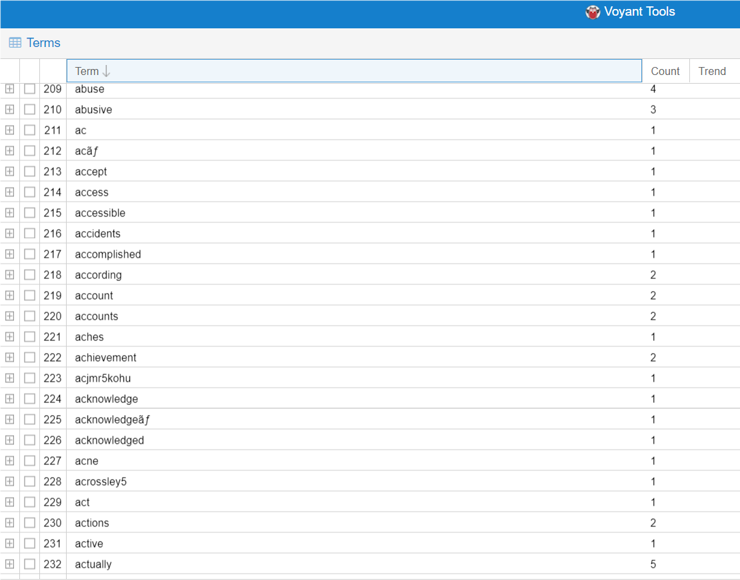

Voyant allows the user to view the word list either alphabetically or by most commonly occurring word. By selecting the most commonly occurring words, we are confronted with the self-reflexive "rt" (1010), "mental" (308), "health" (195), "day" (256), "people" (131), "today" (124), and "tweet" (111), thus largely erasing critical madness from the corpus. However, if we look at the word list alphabetically, smaller clusters and outliers are granted the same visibility as celebrities like Clara Hughes and Michael Landsberg. This is one tactic through which researchers can unearth dissenting voices and collectives in big data projects whose social and social media hegemonies seem unshakeable. Dorothy Kim writes that "What critical discussions about the digital humanities seem to forget are the possibilities of examining and working with minute granularity—the practice of extreme close reading" (234). By looking at alphabetical word lists in Voyant, researchers can navigate between the quantitative tools of big data analysis and the "minute granularity" of "extreme close reading," uncovering those grains of difference in the texture of the corpus. If users are turning to hashtags and digital spaces to form temporary micro-communities that push back against totalizing narratives of neoliberal settler mental health, digital humanities researchers have a responsibility to find and examine these moments of performed and embodied resistance.

In my analysis of the #BellLetsTalk collective automedia, I used Voyant to perform text analysis alongside close reading to establish patterns and relationships. In some cases, I revisited the username or avatar in order to tentatively make claims about the types of communities forming around the hashtag (i.e., masculine and feminine publics) and used this imperfect knowledge in conjunction with an analysis of tweet content, including textual analysis and an attention to the tone/emotional tenor of the tweet (often signaled by emoji use, all capitals, and/or diction). Visual analysis was also used to interrogate images of select bodies that were circulated through the hashtag as idealized crip citizens.

Dataset Biases

Looking briefly at the date and location of tweets/users reveals biases in the dataset that shape the #BellLetsTalk collective automedia and influence my analysis. While most users are located in Canada (according to their Twitter accounts), several hail from the United States (possibly Canadian expatriates), including Los Angeles and Las Vegas, and a few were located in the United Kingdom. Tweets clustered around urban centres like Toronto, Ottawa, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, and Montreal, although smaller towns also appeared under the list of user locations. The tweets spanned the West coast (BC) to the East coast (Newfoundland and Nova Scotia), although the North (territories) was largely absent. Users ranged from verified celebrity accounts like Clara Hughes with thousands of followers to non-verified accounts with only a handful of followers; from users with thousands of tweets to users with less than a hundred; and from established accounts to new accounts. Looking at the metadata collected for this project, we can conclude that Bell's national campaign sparked minimal international engagement and significant intranational engagement. A diverse range of users/avatars participated in the hashtag, although the views of urban users will be more visible. Since Twitter requires access to screen technology and the Internet, many people would not have been able to participate in the hashtag.

Networked Madness: Kinship and Belonging

Support networks were performed, created, and celebrated through the hashtag in ways that trouble the neoliberal individualism of the corporate campaign—even as they rely on a neoliberal social media corporation. #BellLetsTalk hashtag users shouted out to their friends (digital and physical), talked to other avatars, and thanked their friends and family members for being a part of their social support system. With twenty-one uses, "family" was a minor theme that emerged in the dataset, second only to variations of "friend" at sixty uses (including one use of "partner" as in "partner in crime"). While "friend" appeared unequivocally as a positive sentiment (marked by "greatest" and "best," or in some cases, mourned and lost), "family" was sometimes evoked as a support network and other times as a guilt-laden reason to not commit suicide.

Situating mental illness within a network rather than a single body highlights the interdependency of crip community. These digital identity performances can be understood as what Alison Kafer identifies as "claiming crip," which she describes as a tactic for family and friends of disabled people, "acknowledging that we all have bodies and minds with shifting abilities, and wrestling with the political meanings and histories of such shifts" (13). Similarly, Elizabeth Ellcessor highlights Sami Schalk's work on "'identifying with' the political project of disability" as a methodology of experiencing embodiment as a "shifting social location" (27). Choosing to identify with disability or mental illness and participating in the crip network destabilizes the binaries of healthy/sick, abled/disabled, and sane/Mad and makes these categories visible as shifting, unstable, and relational. When we look more closely at these articulations of Mad/crip kinships, different modes of kinship and belonging emerge along multiple axes of identity and distinct social groups.

This framing of disability as a fluid category (which it is) that intersects with many other embodied experiences (which it does) and is a state we will all encounter (which we will), trembles when encountering the hegemonic fury of the family. Following the threads of networked madness means following the ideology of heteronormative "good" families that care, support, and police their crip members. Always, we have to ask of the network: are we cripping the family, or normalizing the crip? While networked madness diffuses feeling and responsibility in a gesture towards queer/crip interdependency, it also risks reproducing the infantilization of Mad bodies over whom parents, psychiatrists, and the state often wield total control. If your disability is our disability, then we have a right to make decisions over that embodied experience—even when it isn't our own body. "Claiming crip" or "identifying with" can be used as tactics to re-imagine disability as a social and cultural category, but this must be done in tandem with the understanding that the individual bodies that compose the network have unique experiences that cannot be collapsed into sameness. Claiming authority over any group experience is always a tenuous and problematic project. Recall Sara Ahmed's ruminations on "happy families": "the happy family is a myth of happiness, of where and how happiness takes place, and a powerful legislative device, a way of distributing time, energy, and resources" (Promise 45). The association between "happy" and "good" that Ahmed interrogates appears in my dataset as a way of policing and disciplining Mad bodies, of telling us what not to do, and how not to act in our mentally ill bodies (in the #BellLetsTalk corpus: suicide is bad, performative unhappiness is bad, bodies that perform unhappiness are bad).

However, in the hashtag we also see family members celebrated as mentally ill role models and/or caregivers in ways that put pressure on the idealized "happy family" and the solitary unit of the mentally ill "bad" body. Users celebrating their relationships with their mom (3), dad (3), brother (3) and sisters or sisterhood (6) position mental illness as something that exists within and across generations and communities, rather than isolated within individual bodies. Here, mentally ill family members and friends are not sites of contagion to be contained in an institution, but members of a network composed of many different nodes through which sadness and anxiety and other bad feelings flow. Inviting us to imagine coming out crip to a parent or hearing a parent come out as crip, a few of the tweets crystallize a key moment in the visibilizing of mental illness, even as the burden continues to fall on Mad/crip bodies to disclose (Kerschbaum et al 2017; McRuer 2006). Again, however, this moment situates mental illness within a relationship rather than a single body, and perhaps brushes against the genetic legacies and intergenerational trauma through which pain is often inherited. The most radical element of these conversations is the diffusion of badness or madness distributed among a network of caregivers, rather than within a bad body. We also see these networks performed on Twitter through retweeting, favouriting, responding, and tweeting at other hashtag users.

These gestures towards community, sociality, and participation de-emphasize individual responsibility and self-management in favour of collective action and caregiving, reproducing the "networks of interdependency" (McRuer, Crip Theory 4) that Mad/crip bodies often model offline. Sharon Snyder and David Mitchell write that "disabled people's openly interdependent lives and crip/queer forms of embodiment provide alternative maps for living together" (3), and crip theorists and activists have been arguing for a cultural paradigm shift towards interdependency over independency for years (McRuer 2006; Mingus 2010; Piepzna-Samarasinha 2018). Returning to the emphasis on friendship in the dataset, I read these tweets as an acknowledgement of the limitations of traditional family structures and proof of queer/crip family. "Friend" and "sisterhood" implicitly introduce non-normative family models into the conversation and broaden the interdependent network from the nuclear family to include queer communities.

In this dataset, we see family used both as a disciplinary technique and an aspirational support system of love and affection. Family is represented as a site of safety and security, even as we see it also being used to produce guilt and shame. There were no references in the dataset to familial abuse. However, there was one reference to childhood sexual abuse, which suggests familial complicity. Celebrating and generating support networks through the hashtag is a form of community-building that invites Mad and sane, crip and non-crip bodies into potentially productive and generative relationships and may be a site of resistance to systemic ableism. However, the ideology underpinning these networks and the use of the frequently occurring word "family" uncovers a complicated relationship between Mad bodies and their support systems. I remember when getting help for my own mental illnesses meant compromise and making myself smaller: accepting being misgendered by health professionals, not performing the feminist killjoy for fear of alienating or losing my support system.

What do we sacrifice in order to be a part of the network?

What are the limit-cases of networked madness?

As we continue our excavation of hashtagged madness, we will hold these questions in mind, as they undoubtedly shape the corporate Mad/crip avatar. Moving deeper into the micro-communities of Mad/crip hashtag networks, I explore the ways in which membership in these networks is contingent on specific identity performances and often reliant on the exclusion of other marginalized bodies. The corpus includes:

- feminine therapeutic networks

- masculine sick publics with deep attachments to capitalist national identity, and

- queer communities that keep company with ghosts.

Feminine Therapeutic Networks

The dataset contains fifteen uses of a variation on "girl" and nine uses of a variation on "boy." Looking closer at these tweets revealed that "girl" was used exclusively to hail another avatar, a conversational referent to another Twitter user. In contrast, "boy" was used only once in the same vein, while the other "boys" in the text referred to supportive boyfriends, hurtful exes, and "boy" as sexual predator and abuser. There were no uses of "girlfriend" in any context. While it is impossible to know someone's gender for certain without asking, the usernames of the "boyfriend" tweeters skewed towards traditionally feminine-coded names. There was one instance of "women" and zero instances of "men" or "man."

What we see emerging is a feminine therapeutic network in which feminine users talk to each other, reference each other, share stories and feelings, and support one another. While this sample again is too small to make broad claims about the entire hashtag, it's not unreasonable to conjecture that women and femmes are more actively involved in the hashtag than men and masculine genders based on the gendering of depression and anxiety, and the way women are socialized into affective/emotional labor and would perhaps be more likely to communicate with other users and express empathy and care. Claiming a feminine therapeutic space online echoes other uses of digital spaces by medicalized feminine-coded avatars. For example, Olivia Banner discusses the "affective intimate publics" ("'Treat Us Right!'" 201) of fibromyalgia (FM) forums that function as online support groups, like the social media platform PatientsLikeMe (PLM). FM is a condition that primarily affects women, leading to the creation of a "specifically female digital publics, where women sometimes reflect on the social conditions that determine how medicine constructs their illness" (200).

We see tweets exploring the relationship between patriarchy and mental illness with an emphasis on the gendering of illness and the reality of living in a feminine-coded body. References to post-partum depression (2) and sexist beauty standards that emphasize thinness and lead to eating disorders or other forms of distress (3) remind the reader that experiences of mental illness emerge within society and culture. These tweets also obliquely suggest that marginalized bodies are more likely to experience mental illness and sidle up against sociocultural critiques of fatphobia and the gender bias within the healthcare system (Banner 2014; Wendell 1996). These tweets both reflect offline pre-existing support groups (of friends, sisters, mothers, etc.) and indicate the creation of a new network and space to discuss "the female complaint" (Banner 198).

Many of these avatars used the network to perform and validate bad/Mad/sad identities and affects. Ji-Eun Lee writes that "The writing and re-authoring of life stories by survivors often works to contest prevailing psychiatric narratives whereby experts retell the stories of patients/consumers through professional interpretation" (106). Emerging as a counterpublic, these collective automedial narratives interrupt both the propaganda of benevolent corporations and caring governments, and a simple trajectory from bad (sick) to good (well). "Depression" (32) was the most cited experience of mental illness, followed by "anxiety" (27). Other tweets signaled depression through either sleeplessness or extreme amounts of oversleeping, crying, and sadness. Users spoke about self-harm, panic attacks, eating disorders (ED), bipolar, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other users liked, retweeted, and/or replied to these identity performances, validating, supporting, and boosting the public profile of these tweets.

Within the performances of mentally ill identity we witness the emergence of a feminine therapeutic Mad/crip digital public in which users share coping mechanisms and validate each other's experiences and bodies through favourites and retweets. Coping mechanisms included listening to music (5), deep breathing (3), and animals/pets (8). These personalized recommendations, typically cited as a coping mechanism for the individual user, often acknowledged that everyone is different, and thus are distinct from generic reminders to "reach out" or "get help." They are offered by mentally ill avatars for other mentally ill avatars and are a form of crowdsourcing as a free alternative or complement to institutional supports like therapy. Although it is beyond the scope of this current project to study the activity of #BellLetsTalk year-round, it is worth noting that there is sustained engagement with the hashtag over the long-term and may offer evidence of an emergent Mad/crip public that discusses mental illness and performs networked madness outside of the single day fundraising campaign.

Masculine Sick Publics

Social constellations of sick masculinity emerged in the hashtag around the conventionally masculine and nationalist rhetoric of sports: references to hockey (15), baseball (1), sports (14), ballfield (1) goalies (2), player (3), athlete (1), and Olympic/Olympian (2) punctuate the document. Tampa Bay, Leafs, Habs. NHL player Paul Ranger was referenced 11 times as an exemplary masculine mentally ill body. Masculine users identify these national male heroes as role models of mental illness, men who can speak openly about their feelings and be emotionally vulnerable—but only because they embody the hypermasculine ideal of able-bodiedness and physical prowess, and because they have gained financial/capitalist success through these hypermasculine bodies. This circulation of the supercrip male avatar mirrors the representation of masculine depression marketed by drug companies (Gardner 2007).

The hashtag #SickNotWeak (28) used in conjunction with #BellLetsTalk circulated a particularly visible form of curated masculine madness. The Twitter account @SickNotWeak (16) is attached to a not-for-profit run by Canadian sports journalist and Bell Let's Talk spokesperson Michael Landsberg. The account enacts a masculine reclaiming of mental illness with an emphasis on strength over weakness and a rejection of the sociocultural emasculation that typically accompanies mental illness in men. The avatar for @SickNotWeak is an older white man (Landsberg) who appears to be in fairly good shape. The website features the chest of a man in a business suit ripping open his blazer in a Clark Kent Superman-style reveal, only in place of the "S" we have a "#", but the allusion is clear: mentally ill men speaking about their experiences through #SickNotWeak are superheroes (and supercrips). This image also celebrates able-bodiedness, whiteness, and financial success (signaled by the business attire). The webpage describing Sick Not Weak eerily positions Landsberg's charity as an avatar with personhood, using the first person "I." One of "his" goals is to "To see the Toronto Maple Leafs win a Stanley Cup in my lifetime." Here, Michael Landsberg takes on the role of the every-man, dis- and then re-embodied as the charity avatar @SickNotWeak, speaking to and for men who have mental illnesses, but are still "real" men: they enjoy physical activity, national sports, and fine tailoring, and are brave and bold enough to say "screw the stigma!" ("About").

This type of masculine community-building relies on pre-existing networks of sports fans and targets a particular demographic: white, able-bodied, middle-class men. Using these common markers of nationalism and masculinity, and relying on shared fandoms, men used #BellLetsTalk to form and strengthen social networks in the production of a collaborative Mad identity. Shout-outs to "my boy" and tweets to/for/about fathers and brothers also inscribe a familial and often generational bent to the "men supporting men" community articulated and performed through #BellLetsTalk. In conclusion, some masculine-coded users were able to harness the hashtag in order to transform pre-existing networks into social support groups, to articulate complex and vulnerable feelings online, and to reach out or offer support to other men. However, in order to access this masculinist therapeutic space, they were required to perform a specific form of masculinity and to uphold nationalist and capitalist values.

(The following section discusses suicide and suicide ideation.)

Ghost Stories: Queering the Crip Family

From gendered networks to the digital reproduction of heteronormative families, #BellLetsTalk doesn't initially appear to enact a politics of queerness. Yet, as discussed earlier, the distribution of madness through the hashtag and its associated networks is a crip/queer process that contains the potential to queer the family, rather than normalize/normativize the crip. It's worth noting that moments of queer identity performance appear in the corpus, from one use of "bisexual" to the feminine-coded avatars identifying with the masculinist rhetoric of #SickNotWeak. The most notable queer/crip potentiality of networked identity and affect, however, is the invocation of suicide.

How do we remember those who died from suicide, when the act of suicide is not speakable?

In the wake of the 2017 Netflix series 13 Reasons Why, fear of suicide contagion led to bans and widespread moral panic. The word "suicide," steeped in fear, pathologization, and horror, is treated as if it contains the germ of contagion that will spread wildly throughout the (implicitly or explicitly youthful) population. So instead it's glossed over, cleaned up, euphemized, silenced. Laurie McNeill reminds us that obituaries typically avoid the word "suicide," and the act is, in some way, unspeakable, a topic that is also a social taboo: "Death by suicide, however, remains problematic for many mourners…Instead writers may mask this situation under the euphemistic 'at home, suddenly,' a safely nondescript cause of death that avoids social abjection" ("Writing Lives in Death" 197).

In the #BellLetsTalk life-writing text that I have assembled—a snapshot of identity performance taken from the dynamic practice of hashtagging—there is a very real tension between the tweets that mourn and remember specific loved ones and generic tweets reminding users of the double meaning behind "lost": we lost people who lost the battle with mental illness. In this double-coded "lost" we see a turn to a dominant illness metaphor: war. War scenes run rampant across Twitter, as users "fight" (27), "struggle" (24) and "battle" (14) with mental illness, and some lose the fight and thus are lost to us. These tweets I read not as a practice of mourning and/or memorializing, but as a form of exploitation in which the avatars of the dead are resurrected to digital life to do the labor of promoting a mental health agenda. These bodies are used to generate fear and are positioned simultaneously as ultimate failure and ultimate tragedy. These strawmen are the end of the road for all those on the journey of depression, used to ward us away from following in their path. Suicide hangs over every discussion of mental health, and the depressed body is positioned as always about to commit suicide. When mapped along this linear narrative of failure, suicide is presented as the "logical" outcome of all mental illnesses.

This is the dominant cultural memory of suicide, and there is a national community-building practice embedded in framing suicide as horror, failure, and tragedy. Consider, for example, the way Canadian settler media employ the phrase "suicide crisis" to refer to the high rates of suicide among Indigenous youth. The phrase positions the body of colour as a body in need of saving, and the use of "crisis" separates individual pathology from the collective and ongoing trauma of colonialism. If "they" (Indigenous populations) have a problem with suicide (presented through the language of epidemiology), then "we" (white settlers) become the benevolent saviours rescuing the Native from herself. On a smaller scale, the term "suicide victim" attaches pity and tragedy to the passive figure of the dead. By remembering suicide as failure, we continue to police the bodies of Mad, suffering, and traumatized people and nations, to shift the burden from oppressive states onto individual bodies, and to justify our (mis)treatment of mentally ill bodies (because they might become suicide victims in the future).

I am not interested in this conventional use of the death-by-suicide, who is rendered silent and forced into a generic linear narrative of failure. Instead, I'm interested in the texts that invite the dead person back into the conversation. To the people who wrote to and of a "dear friend," claiming kinship with the use of "my": "my angel" or "my guy," and directly addressing the dead—"I miss you" (my emphasis). These networks that include the dead turn toward the past, a movement that resonates with Heather Love's queer orientation of "feeling backward." These "explorations of haunting and memory" and "stubborn attachments to lost objects" are "a drag on the progress of civilization" (7). While Love interrogates the narrative of queer progress, we can also use the state of feeling backward to critique the relationship between cure and neoliberal settler colonial progress that seeks to eradicate pain, pasts, and unwanted bodies.

The #BellLetsTalk archive enacts the practices of public mourning and memorializing through hashtagging. Five tweets used variations of "miss you" and spoke of specific people who have died, while six spoke to and of people "lost" to mental illness. The implicit—and sometimes explicit—cause of death in each case was suicide. These users invite the ghosts of the dead into the network, haunting the corporate hashtag with their absence, allowing the dead to belong, and making room for the pathologized expressions of "Mad grief" (Poole and Ward 95). As autobiographical acts, these tweets remain stubbornly resistant to the corporate narrative of healing, health, and happiness and are an important intervention in the aggressive emphasis on cure and health.

Using social media as digital memorials is not a new practice; #BlackLivesMatter and #SayHerName for example, remember those Black bodies murdered by the police. These hashtags harness Twitter in the practice of counter-witnessing, creating living memorials that challenge dominant power structures by remembering the bodies at the margins that have been left out of the national (white) settler archive (Fischer and Mohrman 2016; Gilmore 2017; Tynes, Schuschke, and Noble 2016). We can read these #BellLetsTalk tweets as a response to the censoring of suicide in the mainstream press, and a reclamation of the dead family member outside the discourses of shame and failure. While so many avatars are tweeting to their followers or each other, these avatars are tweeting to the dead, both performing their grief and insisting on the continued humanity and personhood of the deceased. As a memorial, Twitter does not contain the authority of monuments or state libraries. However, Twitter does offer a space for counter-storying cultural, collective, and personal memories that challenge national narratives, and makes visible the struggle and contestation in the process of assembling an archive.

Publicly mourning someone who died from suicide is a radical act.

(This section on suicide has concluded)

Broken Networks: Mad/Crip Alienation

"Belonging" is a fraught and strange term, feeling, negotiation. Sometimes it requires self-sacrifice and other times it requires sacrificing our attachments to power. Networks—physical and digital—emerge around inclusion and exclusion. We may come to the social network for a sense of community and acceptance, but these experiences can also produce anxiety, alienation, and ambivalence. We can use digital spaces and practices like hashtagging to create therapeutic and activist communities, to support one another, to create "access intimacy," where I "feel like I can say what my access needs are, no matter what" (Mingus "Access Intimacy"). We also see belonging contingent on a variety of factors, from gender and race to Internet access, technological literacy, and even grammar. We see a struggle between the good avatar circulated by the corporation and the many misbehaving networks that use the hashtag in unexpected ways, and the limitations of these networks that rely on social cohesion by way of exclusion.

Networked madness in this case study typically maintains its attachments to 1) the family, 2) the conventions of social media networks and 3) the conventions of settler composition. Users retweet, favourite, respond. They participate in the creation not only of a single-authored statement but of a community. They participate in the production and reproduction of Twitter. These users also write in a traditional cohesive structure that generally adheres to conventional grammar, adapted to include acronyms, tags, and emojis. But what about the bad users who break the rules and break the network? Jennifer Pybus explores the affective value of social network sites that create economic value from user-generated content, arguing that "What is central, then, for a social network to function is relationships – affective relationships," adding that users log in "for positive emotional experiences" (237). However, examining Twitter networks more closely reveals the ways in which they produce a range of positive and negative affects. Communication processes coaxed through social networks can indeed foster relationships and communities, but at the same time also produce isolation and alienation.

This section follows the thread of alienation, looking for broken networks that interrupt the therapeutic communities mobilizing around #BellLetsTalk. Not all Mad/crip bodies are allowed into social networks. Not all exclusions are involuntary. Some of us exclude ourselves. We refuse to play by the rules of the game or the group. Where networked Mad/crip bodies and affects challenge the sanist/ableist discourses of neoliberal individualism, resilience, and overcoming, other bad avatars took to the hashtag to disrupt the formation of networks as imagined safe spaces, while still others were forcibly isolated. These articulations of hurt, anger, dissatisfaction, and loneliness register as refusals, breaks, and rejections of the kinds of belonging that were available to some, but not all, users. Ahmed writes that "Sometimes we have to struggle to snap bonds, including familial bonds, those that are damaging or at least compromising of a possibility that you are not ready to give up" (Living 88). Bad avatars use the #BellLetsTalk hashtag to rage, despair, and critique social structures of inequality, including self-referential criticisms of hashtagging and Twitter activism. These users more explicitly take on the role of the Mad/crip killjoy, killing the joy of the network, and distancing themselves from the presumed "goodness" of the network. In contrast to the dominant goodness of networked bodies and affect, some users deliberately embodied bad avatars who feel unapologetically bad.

Despite the first-person narration that is the default on Twitter, many of the #BellLetsTalk tweets are about other bodies rather than the self (although these automedial acts are still always self-performances), and users employ second tense of "you" i.e. "you are not alone." In the corpus, "I" appeared 561 times, and "you" 481 times; these pronouns often come together in the sentence construction of an "I" addressing a—typically, but not always, generic—"you." Furthermore, many first-person narrators discuss past experiences from a distance that almost feels like third person, perhaps because the immediacy has been edited out (i.e., "I was"). They are calm, grammatically correct, and use appropriate punctuation. This use of the second-person or a distanced first-person narrator are modes of making one's identity legible and consumable to a wide audience without alienating readers with emotional outbursts or sentence fragments. Bodies that are used to being criticized or dismissed as hysterical or crazy may have learned to be careful in how they perform Mad. These tweets or threads are the most coherent and the most accessible as autobiography: narrated digital lives. Linear, readable, rational. Maria Leigghio reminds us that "under dominant psy discourses and practices a person who has alternative experiences of reality, often pathologized as being 'psychotic' or as having 'hallucinations,' is disqualified as a legitimate knower because their experiences are interpreted within a modernist framework as a break from reality" (126). In order to become a "legitimate knower," and read as an authority of their own embodied experiences, Mad/crip bodies must imitate the quiet calm impersonal rationalism of Western psychiatry.

"SUCKS" "FUCKING" "shit": other users take a different approach, employing the immediacy of a first-person narrator whose text at least appears to be produced without forethought. Short, staccato tweets about exhaustion and insomnia (sometimes modified by an angry or frustrated "fucking") enact the feelings being communicated. The use of all capitals, swear-words, and lack of punctuation and adherence to grammatical conventions in several tweets signal a tonal shift away from the "good" articulations of mentally healthy/sick identity. This is another form of identity performance, one less coherent, less neat, less structured along a familiar narrative, but no less communicative. Through these guttural enunciations of hurt, anger, fear, and pain, Mad/crip users enact a queer/crip politics that includes the "refusal to cover over what is missing, a refusal to aspire to be whole" (Ahmed, Living 185). These avatars are not recovering, overcoming, or grateful. They refuse to perform happy or healthy. They kill the joy of the therapeutic network. These furious and aggressive tweets perhaps offer one answer to Johanna Hedva's provocative question; "How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can't get out of bed?" Their words are bricks thrown at the social network, smashing the tidy and exclusionary process of mental health community-building.

These screaming, swearing, misspelled, and at times nearly illegible enunciations demarcate the bad avatar from the good—the user who knows when to add a smiley face from the user who sees not a network but a void to shout into. If "happiness is attributed to certain objects that circulate as social good," these users become "alienated – out of line with an affective community – when we do not experience pleasure from proximity to objects that are attributed as being good" (Ahmed, Promise 41). While networked madness destabilizes the happy/sad divide and attempts to wrench "sad" from its association with that sticky word "bad," angry isolated tweets that are affectively out of step with the hashtag perform alienation as a disruption and critique of the network. The objects of social good at stake here are the network and the social media platform. Networked madness, in all its wonderful messiness, remains grateful for these objects, happy for and with these objects. Expressions of gratefulness fluidly transfer from the physical bodies of loved ones to Twitter avatars to the very acts of tweeting and hashtagging.

Of the different performances of alienated madness, angry/angsty youth emerged as a distinct demographic tweeting along a theme: the critique of education institutions. However, this did not appear to be a gesture toward community-building, and the tweets are encountered as a thematically related but distinct set of criticisms and identity performances that perhaps deliberately evade identification with support networks. In contrast, other social criticisms—for example, of poverty and systemic racism—appeared very rarely and seemed to be isolated by users as punishment for trespassing on the settler space of hashtag wellness. In the process of un-networking madness, alienated Mad/crip avatars may be 1) actively seeking to disidentify from the therapeutic public with their claim to bad feelings and/or 2) forced into isolated discursive pockets or solo tweets because they do not enact an attachment to the network or locate healing within these spaces.

Delving deeper into the corpus uncovered a few isolated tweets that, while not deliberately attempting to subvert the politics of the network, were isolated because of their content. If critical youth seek to deliberately break the network, avatars of colour and poor avatars seeking to engage in social criticism were isolated by other users. The scarcity of explicit cultural critiques also suggests that more radically minded users were already alienated from the hashtag and did not find it to be an accessible and welcoming site for the kinds of digital identity acts they wanted to perform. These singular, isolated tweets point to the limits of corporate hashtagging and the reproduction of whiteness as goodness in colonial mental health campaigns.

One tweet referenced job loss due to mental illness, implying discrimination and pointing to the brutality of capitalism that bulldozes marginalized bodies, particularly disabled and mentally ill bodies of colour. Another tweet critiqued the lack of adequate disability leave. One tweet identified poverty and racism as barriers to accessing care. Looking for POC (particularly BIPOC, WOC, and QOC) in a dataset that is so glaringly, hurtfully white is tricky, and an ethically fraught practice for a white settler scholar. However, I do want to acknowledge that there were users—likely people of colour—critiquing #BellLetsTalk as being inadequately intersectional, and I do not want to participate in the erasure of these important and difficult identity acts. For example, in 2017, in direct response to Bell Let's Talk, Black Mad artist and activist Gloria Swain created the counter-hashtag #BellLetsActuallyTalk. 7

The Future of Feminist DH: Creativity & Care

This article laid out my creative and critical approach to performing crip feminist DH research by generating a multi-authored automedial text. This process protected the anonymity of users and turned away from venerating the individual "I" in order to interrogate networks, assemblages, and relationships. This tactic challenges the "neoliberal life narrative" of "the self-made man, and the empowered woman" (92 Tainted) that Gilmore laments, and turns towards interdependency, collectivity, and community. By protecting the identities of users, I also practiced an ethics of care for the bodies that compose our powerful, fragile, and dangerous social networks.

The future of feminist DH lies in creativity and care. I am attentive to the dialogues about ethics and methodologies that are occurring in informal Zoom meetings and formal conferences, that are mapped out in the edited collection Good Data, that are finding their way into footnotes or full articles. Our research is also shaped by innovation and invention: consider, for example Moya Bailey's work with the hashtag #GirlsLikeUs, and her emphasis on foregrounding consent, accountability, and collaboration (2015). Bailey's article imagines one way of ethically engaging with digital bodies and community partners. In the introduction to Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and the Digital Humanities, Elizabeth Losh and Jaqueline Wernimont foreground "the tasks of intersectional feminisms, of coalition building, and of communal care and repair" (ix) as a critical direction in DH. The collection includes a range of creative approaches to doing digital scholarship. Creativity lives in both product and process, in our plans and the revisions we make to our research plans.

In 2018, I wrote a call for papers (CFP) for the annual Sherman Centre for Digital Scholarship graduate scholarship. Our chosen theme that year was "System/Système D: Improvising Digital Scholarship." In the CFP I wrote:

System/Système D: to improvise, change, adapt. We use this term playfully to acknowledge the creativity, troubleshooting, and failures that accompany digital scholarship. Innovation and learning binds digital scholars together as we navigate uncharted waters with new evidence, new tools, and new questions. What does it mean to improvise within the field of digital scholarship? What challenges do digital scholars face and how can they be overcome? What can we learn from interdisciplinary approaches and how do we make the field more accessible to diverse voices?

I think about these questions when my laptop or PC crashes, when Python crashes, when my Python code fails, when parts of the data I collected are corrupted or lost. I think about pain. I think about access as a Mad/crip body. I feel fatigue settling under my skin. Each digital media project requires a different research framework and a different understanding of vulnerability, accountability, and collective care. Working with video games is not the same as working with a Twitter hashtag data set, which is not the same as working with Instagram, blogging, or TikTok, even as platforms, users, and audiences intersect and overlap.

I came to this project with a methodology prepared and then had to improvise, adapt, and create new ways of working with and through the barriers and affordances of digital scholarship; of embodiment; of time and energy and money. Feminists and disability scholars and activists are redefining what the study of digital media and mediated lived might look like, challenging digital humanists to be creative and inventive in our methods and practices, and encouraging us to think critically about how to perform our research in an ethical manner. Looking to the future, my hope for this field is that it continues along a trajectory towards critical reflection and an ethics of care, and that it shifts away from sane/able-bodied feminisms and towards centering the Mad/crip bodyminds—of researchers, subjects, and audiences (recognizing we can be all three at once)—in the methodologies we generate to perform and communicate our research.

Works Cited

- "About." Sick Not Weak, https://www.sicknotweak.com/lets-work-together/.

- Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822373377

- —. The Promise of Happiness. Duke University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822392781

- Al Zidjaly, Najma. "Managing Social Exclusion through Technology: An Example of Art as Mediated Action." Disability Studies Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 4, 2011. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v31i4.1716

- Bailey, Moya. "#transform(ing)DH Writing and Research: An Autoethnography of Digital Humanities and Feminist Ethics." Digital Humanities Quarterly, vol. 9, no 2, 2015, http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/9/2/000209/000209.html.

- Banner, Olivia. "'Treat Us Right!': Digital Publics, Emerging Biosocialities, and the Female Complaint." Identity Technologies, edited by Anna Poletti and Julie Rak, University of Wisconsin Press, 2014, pp. 198–216.

- Clare, Eli. Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure. Duke University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822373520

- Coleman, Beth. Hello Avatar: Rise of the Networked Generation. The MIT Press, 2011.

- Daly, Angela, S. Kate Devitt and Monique Mann. "What is (in) Good Data?" Good Data. INC Theory of Demand Series, 2019, pp. 8-23, https://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/tod-29-good-data/.

- Ellcessor, Elizabeth. Restricted Access: Media, Disability, and the Politics of Participation. NYU Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479867431.001.0001

- Fischer, Mia and K. Mohrman. "Black Deaths Matter? Sousveillance and the Invisibility of Black Life." Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media & Technology, vol. 10, 2016.

- Gardner, Paula. "Re-Gendering Depression: Risk, Web Health Campaigns, and the Feminized Pharmaco-Subject." Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 32, no. 3, 2007, pp. 537–55. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2007v32n3a1862

- Gilmore, Leigh. "Limit-Cases: Trauma, Self-Representation, and the Jurisdictions of Identity." Biography, vol. 24, no. 1, 2001, pp. 128-139. https://doi.org/10.1353/bio.2001.0011

- —. Tainted Witness. Columbia University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.7312/gilm17714

- Hedva, Johanna. "Sick Woman Theory." Mask Magazine, Jan. 2016, https://topicalcream.org/features/sick-woman-theory/.

- Jackson, Sarah J., Moya Bailey and Brooke Foucault Welles. #HashtagActivism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice. MIT Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10858.001.0001

- Kafer, Alison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana University Press, 2013.

- Kerschbaum, Stephanie L., Laura T. Eisenman, James M. Jones, Davit T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder. Negotiating Disability: Disclosure and Higher Education. University of Michigan Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9426902

- Kim, Dorothy. "Building Pleasure and the Digital Archive." Bodies of Information, edited by Elizabeth Losh and Jacqueline Wernimont, University of Minnesota Press, 2018, pp. 230-260.

- Lee, Ji-Eun. "Mad as Hell: The Objectifying Experience of Symbolic Violence." Mad Matters: A Critical Reader in Canadian Mad Studies, edited by Brenda A. LeFrançois, Robert Menzies, and Geoffrey Reaume, Canadian Scholar's Press Inc., 2013, pp. 105–21.

- Leigghio, Maria. "A Denial of Being: Psychiatrization as Epistemic Violence." Mad Matters: A Critical Reader in Canadian Mad Studies, edited by Brenda A. LeFrançois, Robert Menzies, and Geoffrey Reaume, Canadian Scholar's Press Inc., 2013, pp. 122–29.

- Losh, Elizabeth and Jacqueline Wernimont, editors. Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and the Digital Humanities. University of Minnesota Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctv9hj9r9

- Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Maguire, Emma. Girls, Autobiography, Media. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74237-3

- Mann, Benjamin W. "Survival, Disability Rights, and Solidarity: Advancing Cyberprotest Rhetoric through Disability March." Disability Studies Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 1, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v38i1.5917

- Masschelein, Anneleen and Rebecca Roach. "Emergent Conversations: Bronwyn Davies on the Transformation of Interview Practices in the Social Sciences." Biography, vol. 41, no. 2, 2018, pp. 256–69. https://doi.org/10.1353/bio.2018.0022

- McNeill, Laurie. "Life Bytes: Six-Word Memoir and the Exigencies of Auto/Tweetographies." Identity Technologies, edited by Anna Poletti and Julie Rak, University of Wisconsin Press, 2014, pp. 144–64.

- —. "Writing Lives in Death: Canadian Death Notices as Auto/Biography." Auto/Biography in Canada: Critical Directions, edited by Julie Rak, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2005, pp. 187–205. https://doi.org/10.51644/9780889209213-010

- McRuer, Robert. Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability. NYU Press, 2006.

- Mingus, Mia. "Access Intimacy, Interdependence, and Disability Justice." Leaving Evidence. 12 April 2017, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/access-intimacy-interdependence-and-disability-justice/.

- —. "Access Intimacy: The Missing Link." Leaving Evidence, 5 May 2011, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link/.

- —. "Interdependency (Excerpts from Several Talks)." Leaving Evidence, 22 Jan. 2010, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2010/01/22/interdependency-exerpts-from-several-talks/.

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, Leah Lakshmi. Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018.

- Poole, Jennifer M. and Jennifer Ward. "'Breaking Open the Bone': Storying, Sanism and Mad Grief." Mad Matters: A Critical Reader in Canadian Mad Studies, edited by Brenda A. LeFrançois, Robert Menzies, and Geoffrey Reaume, Canadian Scholar's Press Inc., 2013, pp. 94–114.

- Price, Margaret. "The Bodymind Problem and the Possibility of Pain." Hypatia, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015, pp. 268-284. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12127

- Pybus, Jennifer. "Accumulating Affect: Social Networks and Their Archives of Feeling." Networked Affect, edited by Ken Hillis, Susanna Paasonen, and Michael Petit, MIT Press, 2015, pp. 235–47. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9715.003.0019

- Rambukkana, Nathan. Hashtag Publics: The Power and Politics of Discursive Networks. Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2015. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-1672-8

- Schalk, Sami. Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women's Speculative Fiction. Duke University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822371830

- Swain, Gloria. Bell Let's Actually Talk. 2017, https://lets-actually-talk.tumblr.com/.

- Tynes, Brendesha M., Joshua Schuschke and Safiya Umoja Noble. "Digital Intersectionality Theory and the #BlackLivesMatter Movement." The Intersectional Internet: Race, Sex, Class, and Culture Online, edited by Safiya Umoja Noble and Brendesha M. Tynes, Peter Lang Publishing, 2016, pp. 21-40.

- Wendell, Susan. The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability. Routledge, 1996.

- Zeffiro, Andrea. "Provocations for Social Media Research: Toward Good Data Ethics." Good Data, edited by Angela Daly, S. Kate Devitt, and Monique Mann, INC Theory of Demand Series, 2019, pp. 216–43, https://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/tod-29-good-data/

Endnotes

-

In July 2023, Twitter was bought by Elon Musk and rebranded as "X,: and tweets are now referred to as "posts: on the site. However, since my research is based on the 2018 version of the app, I will use 'Twitter' and "tweets: throughout this paper.

Return to Text -

As of 2024, Bell Let's Talk Day continues to be an active, annual campaign in Canada.

Return to Text -

A tool for cleaning messy data.

Return to Text -

An open source code editor, although I did not use it to edit code.

Return to Text -

https://konklone.io/json/

Return to Text -

An open-source tool for performing textual analysis, Voyant provides data on text content: i.e., number of times a word occurs in the text, average sentence length, etc. Voyant also offers simple visualizations like Wordles to demonstrate more and less commonly occurring terms.

Return to Text -

The hashtag was not active in 2018.

Return to Text