This article examines narratives of disease and disability in Canada's gay and lesbian newspaper, The Body Politic (1971-1987), in order to demonstrate how gay male masculinity developed within a gay ableist culture deeply affected by HIV/AIDS. Over the course of the 1980s, two seemingly separate issues of disability and disease were woven together, establishing a dichotomy between the unhealthy and healthy, afflicted and non-afflicted, disabled and non-disabled body, which was marked by tension and, at times, hostility. As a result, two seemingly different discussions of disability and disease in The Body Politic intersected at the site of the gay male body, whereby issues of frailty and undesirability were shaped by pre-existing perceptions around disability. Narratives around disease and disability demonstrate how perceptions of bodily "failure" transferred from the disabled body onto the diseased body during the formative years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic through imagery and text. The aesthetics and language of disability are particularly important for understanding how the disabled body and the HIV/AIDS-afflicted body were culturally framed because the stylization of the body itself was fundamental to the politics of sexual liberation and the formulation of visible lesbian and gay communities.

Writing in November 1982, Michael Lynch—then an editor at Canada's longest running gay and lesbian newspaper, The Body Politic—described his New York City friend, Larry's (a pseudonym for a man later identified as Fred) long battle with Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), an AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome)-related cancer. When in hospital for treatment, Fred's mother, Selma noted that her son "persisted in calling his illness 'Kaposi's,' which to her was his way of saying to everyone he was gay." 2 KS was not only a highly visible skin disease—forming lesions on the skin of its victims—but it became synonymous with gay men and gay promiscuity when it was discovered to be a common secondary disease of AIDS. 3 This article examines narratives of disease and disability in The Body Politic (1971-1987), referred to hereafter as TBP, in order to demonstrate how gay male masculinity developed within a gay ableist culture deeply affected by HIV/AIDS. Over the course of the 1980s, two seemingly separate issues of disability and disease were woven together, establishing a dichotomy between the unhealthy and healthy, afflicted and non-afflicted, disabled and non-disabled, which was marked by tension and, at times, hostility. As a result, discussions of disability and disease in TBP intersected at the site of the gay male body, whereby issues of frailty and undesirability were shaped by pre-existing perceptions around disability.

In the many discussions around AIDS and its preliminary stage, HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), TBP's editorial collective disentangled gay men's sexuality, masculinity, and bodies from disease. The collective offset narratives of gay men as victims of disease by buttressing (desirable) gay male masculinity as active, virile, and healthy. The newspaper also featured numerous reports and articles from 1982 onward describing the "debilitating" and "disabling" effects of HIV/AIDS. Use of such language perpetuated the perception that the HIV/AIDS-affected body transformed into something comparable to the physically disabled body—unable to perform gender or sexuality in a desirable or "normative" manner. More importantly, the narratives around disease and disability in TBP demonstrate how perceptions of bodily "failure" transferred from the disabled body onto the diseased body during the formative years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic through imagery and text. TBP reveals the establishment of similar "stylistic" expectations for how diseased and disabled bodies ought to perform within what we now call the queer community, as well as how community members—both able-bodied and disabled—responded during an epidemic that plagued North America more broadly. The aesthetics and language of disability are particularly important for understanding how the disabled body and the HIV/AIDS-afflicted body were culturally framed because the stylization of the body itself was fundamental to the politics of sexual liberation and the formulation of visible gay male communities.

First and foremost, the HIV-affected gay male body was almost ubiquitously presented in TBP as white, ignoring the ravaging effects of the disease particularly for African Americans and Canadians. The limited coverage of non-white gay men with HIV/AIDS was not exclusive to TBP, however. As historian Martin Duberman contends, the New York Times published "only three articles between 1981 and 1993 that focused primarily on black gay men with AIDS." 4 The silence around African Americans with HIV/AIDS was notably contested by artists such as Joseph Beam and Essex Hemphill, both of whom sought to address the intersections of racism, capitalism, and homophobia, as well as the loneliness of African Americans affected by the disease. 5 Referring to Hemphill's 1993 poem, "Vital Signs," Darius Bost argues that the legacy of slavery and "antiblackness…marked black people as 'socially dead,' thereby rendering their suffering as normative and unremarkable." 6 As a continuation of this legacy, as well as the consequences of gay cultural life centering on white able bodies, the suffering of Black gay men from HIV/AIDS was suppressed by more prominent narratives of the disease's effects on white gay men. While mainstream and gay publications ignored the impact of HIV/AIDS on African Americans, another kind of silence about HIV/AIDS was fed by a distrust found in many Black communities in response to the Tuskegee syphilis experiments and the long history of racial segregation that limited Black people's access to medical services. According to James H. Jones, many Black gay men regarded HIV/AIDS as the latest expression of "racial genocide". 7

Furthermore, the exclusion of persons with disabilities from this queer sexual culture perpetuated their invisibility and tropes of their a-sexuality, a major point of contention that continues to reverberate and mobilize contemporary debates in queer communities around the politics of desire and inclusion. Termed "horizontal hostility" 8 by writer and activist Eli Clare, he argues that "[m]arginalized people from many communities create their own internal tensions and hostilities, and disabled people are no exception." 9 For those who acquired HIV/AIDS, their bodies were similarly relegated to the periphery of queer life, just as many persons with disabilities, especially those with visible "conditions," had been. This "stigmaphobic distancing"—a term used by disability theorist Robert McRuer to describe the process by which more stigmatized members of the community are distanced from by those desiring to be "normal," or at least seen as normal—is evident in the ways in which queer sexuality was stylized as a performance hinged on healthy able-bodiness. 10

For Fred, the lesions on his skin were a corporeal reminder that gay male masculinity was becoming refashioned along the lines of health. Health and muscularity took on new meaning in the pageantry of gay male masculinity whilst those perceived as disabled or "debilitated" by HIV/AIDS became increasingly secluded from gay culture. Stories such as Fred's are heart-wrenching and they should not be read as merely case studies for tracing the development of discourses around disease, disability, and health in what is now referred to as the queer community. The emotions in these stories—compassion, anger, sadness, trauma, and love—reflect the significance HIV/AIDS had in shaping gay communities across North America by bringing people together as well as tearing them apart. Within these narratives, however, are discussions around gay male masculinity, gender, sexuality, and health that demonstrate the importance of stylizing the gay male body during the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s in an effort to combat stereotypes of frailty or weakness following the disease, common tropes associated with the physically disabled body.

The Body Politic

The Body Politic is an important resource for understanding the intersection of disability and HIV/AIDS because it was both Canada's largest gay activist newspaper during its tenure between 1971 and 1987, and it engaged in many intellectual discussions around gender, sexuality, ability, and disease occurring across North America and Western Europe. Formed in Toronto in 1971, TBP grew in size and scope to include social and cultural developments occurring in gay communities across Canada and the United States as well as discussions, debates, and deeper questions about gender, sexuality, race, the body, disability, and HIV/AIDS in Toronto's gay community. The newspaper's predominantly middle-class intellectual readership placed it as one of North America's most "politically engaged and intellectually sophisticated lesbian and gay periodicals," in the words of David Churchill. 11

Using a textual analysis of editorial content, illustrations, and input from readers of TBP reveals how gay male masculinity was in large part defined by the written and visual aesthetics surrounding the male body. Dividing this article between HIV/AIDS and disability disentangles overlapping tropes around health and the body while highlighting the body as an important cultural text. As the HIV/AIDS-afflicted body was debilitated by the disease, its muscular non-disabled counterpart simultaneously took on new meaning as an aesthetic of healthy and "normal" gay male sexuality. The dichotomy between the unhealthy and healthy, diseased and non-afflicted, disabled and non-disabled was marked by tension and, at times, hostility. Furthermore, comparing the representation of disability to HIV/AIDS bodies reinforces scholar Lennard Davis's argument that with "disease-generated disabilities—AIDS, tuberculosis, multiple sclerosis, arthritis, chronic illnesses—the instability of the category 'disabled' begins to appear." 12 Although discourses of disease and disability seemingly collided with each other, I focus on each differently, but always with their collusion in mind.

Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas's concept of "queer style" is an important analytical tool to approach the numerous advertisements, articles, and images in TBP that seemingly championed white butch performances of masculinity in the gay male community, while marginalizing bodies perceived as disabled or diseased. Queer style includes the bodily posture, the legibility of (dis)ability, how one dresses, their grooming, one's visible physique, their vocalizations, gesticulations, mannerisms, and other characteristics of the body that are presented in society. It is both an aesthetic adoption and rejection of the sexual status quo or, using Adrienne Rich's term, "compulsory heterosexuality," in order to reproduce alternative sexual ways of being. 13 Geczy and Karaminas argue that whereas heterosexuality "is aligned to legible codes such as the suit for the male and the dress for the female, queer style is resistant to them. It does, however, have a set of consistent attributes such as non functionality and exaggeration." 14 The exaggeration of butch masculinity and femininity that was pronounced in TBP demonstrates a latent heteronormativity around gender and sexuality in the gay male community of the time, notably non-disabled white macho performances of masculinity. Thus, queer style is useful in highlighting ways in which gay men played with masculinity but also adopted ability as a critical component to the pageantry of the gay male body in TBP—a process that is not always explicit or straightforward.

Visualizing the male body and dressing the body (up or down) to perform expected masculine mannerisms and roles is a fundamental component in the socialization and normalization of gay masculinity as a style. "Style," in the words of Susan Sontag, is a "notion that applies to any experience (whenever we talk about its form or qualities)." While visual art, fashion, and music have style in the conventional sense, Sontag argues that "Whenever speech or movement or behaviour or objects exhibit a certain deviation from the most direct, useful, insensible mode of expression or being in the world, we may look at them as having a style, and being both autonomous and exemplary." 15 Kelby Harrison compares Sontag's definition of style with philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty's understanding of style as a lived phenomenon or "expressive gesture" to articulate style as a manifestation that is "not a mask, but instead an actual form of existence." 16 This postmodern approach to style builds upon late modernist Erving Goffman's argument that individuals hide their real "self" with masks that are both material and performed. 17 Rather than pursue style as an expression of the inner self, style is an integral linkage between an individual's purposeful identity and their engagement with the world.

The relationship between style and gender resonates with Judith Butler's theory of performativity and the body. Butler argues that gender, assumed to be a natural internal essence, "is manufactured through a sustained set of acts, posited through the gendered stylization of the body." 18 As a result, movements, gestures and acts of the body "constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self." 19 I use performativity in conjunction with Susan Schweik's theory of "deformance," whereby the deformed subject becomes the permanent other and represents "the asymmetrical relation between displayer and displayed, usually between classes, and between the nondisabled and the disabled." 20 Using the model of deformance to approach disability and HIV/AIDS opens up possibilities to interpret embodiments of disease and disability as simultaneously transgressing gendered and sexual norms while also buttressing ableist desirability within queer culture.

Historiography

My reading of TBP as an actor in reinforcing and combatting the self-regulation of gay male masculinity is an important shift away from previous scholarship that has focused on the publication as an engine for political activism and knowledge. Patrizia Gentile and Gary Kinsman's The Canadian War on Queers, Ann Silversides's AIDS Activist, and Thomas Waugh's Romance of Transgression in Canada have recognized TBP for its role in subverting the policing of gays by the state and as a forum for discussions on AIDS and the fragmentation of gay activism. Indeed, TBP's coverage of the cultural reverberations that HIV/AIDS had in both gay and mainstream communities solidified the recursive relationship between the personal and the political. However, this article positions TBP as a broader cultural text that mediated representations of gay male masculinity with cultural commentary on gender, race, the body, disability, and disease.

During the HIV/AIDS epidemic, gay men afflicted with the disease were culturally interpreted, especially in the early 1980s, as being unable to meet expectations of how bodies should function and operate on a sexual level in a society that centered on neoliberal and capitalist ideals of ableism. Rosemarie Garland-Thomson argues that "disability is a representation, a cultural interpretation of physical transformation or configuration, and a comparison of bodies that structures social relations and institutions." 21 Furthermore, disability scholar Dan Goodley argues that "[w]hile some bodies and populations are deemed more precarious than others, we are all debilitated in and by neoliberalism capitalism." Citing Jasbir Puar's article, "Prognosis time: Towards a geopolitics of affect, debility and capacity," he further contends that "[m]any of us fail to meet the demands of neoliberal ideals. And debility is to be found at that moment when dis/ability collides." 22 HIV/AIDS threatened to obstruct or debilitate gay male sexuality as it had been socially imagined, particularly by raising concerns about the safety of gay male promiscuity.

Disability and Masculinity

Shortly before the HIV/AIDS epidemic attained media spotlight and brought gay men's bodies under medical scrutiny, the first detailed discussion of gay men with disabilities in TBP appeared. In February 1980, Gerald Hannon wrote an exposé describing the second closet that most gays and lesbians with disabilities experience. With the title, "No sorrow, no pity," Hannon's article contended that "at the back of our own closets we have built another one, and into it we have shoved our gay deaf and our gay blind and our gay wheelchair cases, and we've gone on with the already difficult enough problems of living as gay people." In Hannon's opinion, the lack of visibility for gay people with disabilities in the community or TBP stemmed from the same oppression faced by gay men and women in mainstream society. Using the metaphor of the closet, Hannon took disability out of the realm of medicine and the body and made it an issue in the gay community. Indeed, he acknowledged that while race, class, sexuality, and gender were significant registers in gay culture and reflected in TBP, disability had perhaps been forgotten because of "our dogged insistence on our essential health as gay people, on our persistent view of ourselves in our own media as whole, active, healthy, bright and beautiful." 23 Health and the portrayal of healthy bodies in discussions of disability in TBP before the AIDS crisis were refashioned once the latter epidemic erupted and visibly affected the gay male body.

Disability was described in no uncertain terms as being a hindrance to sexual viability and normative performances of masculinity. Indeed, the notion of homosexuality also shares a long history with "disability." Disability rights activist James Charlton argues that assumptions around disabled asexuality stem from both a medicalization of disabled bodies as well as an inherent paternalism that consigns those perceived to be disabled as children. 24 The perception of asexuality was a dramatic shift from early twentieth century narratives of those with cognitive disabilities as "social menaces and sexual predators," according to Michelle Jarman. 25 Disability Studies scholar Tobin Siebers notes that "[o]ne of the chief stereotypes oppressing disabled people is the myth that they do not experience sexual feelings or that they do not have or want to have sex…" 26 He maintains that disabled people lack privacy because they are frequently inundated by medical observation which include an invasion of their space. Those whose minds did not function in ways understood to be "normal" were relegated to the periphery of society, homosexuality being no exception.

Social barriers, such as being refused entry into bars or a lack of service, discouraged people with disabilities from making themselves visible in gay culture. Activist for the rights of people with disabilities, John Kellerman, described to Hannon in "No sorrow, no pity," how he was refused into gay baths in Winnipeg for being disabled, though he did make sure to mention that he had not experienced discrimination at gay bars in Toronto. The ostracism he faced as a man with Cerebral Palsy discouraged him from socializing and being present in spaces non-disabled gay men took for granted. "I want to develop a relationship with someone, but nothing much has happened with either men or women. I've often wanted to go to the baths, but I'm afraid to because I'm afraid they wouldn't let me in," he told Hannon. 27 Despite Kellerman's more positive experience in Toronto, Hannon and others in the editorial collective were wary of the "welcome" attitude towards gay men with disabilities.

In a survey on Toronto establishments following Hannon's article, it was noted that, "It's also pretty easy to talk a good game to an inquiring reporter — both the St Charles and Parkside taverns made welcoming sounds, but I'm told both have refused service to CPers [people with Cerebral Palsy] in wheelchairs." 28 Discriminatory practices at these establishments reinforced the invisibility of people with disabilities in a gay culture that decades prior had been invisible itself. Hannon's examination of the discrimination faced by those with a disability appears to have been sparked, at least partially, by his interview with Kellerman. No stranger to activism, Kellerman had previously requested $2,000 from the Ontario provincial government in 1974 to fund a conference on sex and sexuality for people with disabilities. 29 Kellerman was actively involved in organizing the International Year of the Disabled taking place in 1981. Furthermore, the Canadian federal government had begun considering independent living resource centres as part of an effort to allow those with disabilities to overcome structural, financial, and social barriers, culminating in the federal government's Obstacles Report (Special Committee on the Disabled 1981). 30 Coverage of disability could thus lend itself to a positive reception and recognition of TBP at conferences and workshops on disability and promote the newspaper as an inclusive forum for all marginalized groups.

Physical boundaries, such as stairs, also prevented those with disabilities from socializing with other gay men. Hannon asked readers to consider the "next time you're at your favourite gay spot, count the stairs." 31 Complementing Hannon's article was an anonymously-written report on disabled people's access to gay Toronto establishments. The report surveyed business owners and managers of local gay bars, bathhouses, and discos, and noted that "Most gay watering holes in this town do seem to have a lot of stairs, and none have washrooms adapted to wheelchairs, so a willingness to be friendly certainly doesn't solve all problems." 32 However, discussions of exclusionary practices or the lack of accessibility at gay bars and bathhouses did not appear in TBP's city guides following this article, notably John Allec and Edna Barker's "Hot Spots" guide to Toronto in July-August 1982, raising questions about the newspaper's sincerity in facilitating accessibility in the gay community. 33

In an attempt to rethink what it means to be disabled, Hannon argued that infancy and old age had some of the same effects of disability. He argued that while limitations from age are "not the same as spending your life blind, or deaf or in a wheelchair…it does indicate that we are talking about a spectrum here, not discrete and mutually exclusive groups." 34 Broadening the scope of disability to include nearly everyone at one stage or another in their life was an effort to bring the experience of having a disability that much closer to readers. In doing so, Hannon challenged the static nature of ableism and highlighted the inevitability of impairment, a move that would later be taken up by scholars in the late 1990s. 35 He did not, however, counter cultural stereotypes of disabled bodies as being void of masculinity or sexuality. Concluding "No sorrow, no pity," Hannon interviewed gay activist Tom Warner who told Hannon of a time when he was picked up by a man who was unable to walk. Warner proceeded to go to bed with him only to find it did not work out because "his legs were so cold. I flinched every time they touched me and of course he sensed it." 36 Warner's experience stresses a reactionary discomfort with how the man's body failed to perform. Furthermore, it demonstrates that even those conscious of how disability intersected with sexuality struggled to negotiate their own desires for bodies that functioned in "normal" ways.

Hannon's article undoubtedly provoked greater dialogue in TBP around disability within the community. In June 1981, Fo Niemi, a reader who was equally vocal about racism plaguing Black, Asian, and Latino men, called for "[a] clearly visible and well-organized handicapped gay group [that] will help promote the needs and goals of disabled gays and facilitate the members' reintegration in the mainstream of society." 37 Heeding this call, seminars for gay and disabled men and women appeared in the classifieds section of TBP in the early months of 1981, such as those organized by Wilf Race and Chris (last name withheld) who advertised their "[f]our-session seminars for physically disabled gay men." 38 Other organizations also informed readers that they were accessible for those with physical and cognitive disabilities. Yet, it was the input from members of the queer community who had a disability that seemingly fostered the greatest discussions of how disability and desire intersected.

For 19-year-old Warren Camp of Mississauga, Ontario, the prejudice of society seemed to be half of the battle. Writing into TBP in November 1983, Camp was responding to Hannon's "No sorrow, no pity," from years prior. He began by challenging the use of the term "disabled," arguing that "it has done as much to reinforce stereotypes today as the archaic 'crippled' did in years past." 39 Camp's critique demonstrates a concern that various physical or mental disabilities were generalized together, reducing people to the same experiences of oppression. Instead of focusing on his physical disability, Camp saw the opportunities that his prosthetic legs provided. As someone with two prosthetic legs but not in need of a wheelchair, Camp admitted that his ability to get past the physical barriers and socialize in bars made his coming out easier. This view ran counter to Hannon's approach to disability as an obstacle in of itself, indicating that people living with disabilities nuanced the ableist viewpoints of TBP's editorial collective.

Camp described his own experience with the popular sentiment that people with disabilities are not, or should not, be gay. In his opinion, this view had much to do with how gay male masculinity has been styled around the body. "With so much emphasis placed on physical appearance, they [disabled people] represent an unsightly fringe element. They're better off just not coming out!" he argued. His point reiterated Hannon's aforementioned argument that the gay community had built a closet within itself. Evidently, the International Year of the Disabled and coverage of disability in 1981 had done little to change the politics around desirability and disability.

Camp challenged the framing of the body in the construction of masculinity and sexuality during his many conversations with men at the bars. His goal was to demonstrate that disability is a fraction of a person's identity and that "[w]hen all the clothes are shed and we are stripped down to raw reality, we find warts on everyone, making that a fact of life to be reckoned with, and not ignored [emphasis in original]." 40 This statement was a critique of the performative element of masculinity as a style that involved covering up of the flawed elements of the body. By comparing disability to "warts" found on everyone, Camp positioned disability within the realm of aesthetics, suggesting that what constituted disability was a matter of perspective since nobody epitomized the ideal body. It also articulated how disability was socially viewed as a stylization of the body that required covering up. Hence, in the gay community, style was just as much about covering up or ignoring aspects that did not adhere to values of desirability.

Other gay men with disabilities contested erasure in TBP through classified ads. Ads from men with disabilities or individuals requesting men with perceived disabilities were ephemeral and inconsistent at best, but they did exist in greater numbers after Hannon's exposé on disability in February 1980. In May 1982, Scott, a 30-year-old gay white man living in Toronto, described himself as, "wheelchair-bound with cerebral palsy," and ensured the reader that "experience with disabled was unnecessary." 41 The following month, Richard, a man interviewed by Hannon for his aforementioned article, submitted an ad stating that he was aroused by "taller, hairier huskily-built types. Late 20s to early 30s preferred, but young at heart matters most." 42 Not only did Richard refer readers to his personal description in "No sorrow, no pity," but he also requested a picture at the end of the ad. In his interview, Richard had mentioned how he determined "gayness" by the sound of someone's voice rather than rely on visual markers. To request a photograph seems to defy the stereotype that blind gay men were unable to read, let alone appreciate, the visual elements of queer style. While it is unknown if Richard examined the photograph himself or had it described to him, this ad further demonstrates that gay men with disabilities also took part in the policing and perpetuation of desirable queer styles.

However, there did exist a number of ads that specifically requested gay men with disabilities, appearing to counter any holistic narrative of disabled asexuality. A submission by a man in Toronto in search of men with disabilities stressed the "sincere" intentions of his ad. In October, 1980, the "gay male, 23, 6'1", 170 lbs" wrote in seeking an "amputee or disabled under 25 for sincere relationship. 43 Another classified ad written in December 1984 by Alan, a 28-year-old "straight acting" white man, requesting "people who use leg braces, wheelchairs, and especially amputees. Nothing kinky, just an honest friendship/relationship wanted. Ages 21ish to 32ish." 44 It is unknown if Alan himself identified as disabled, but his request for a disabled partner suggests that not all gay men saw disability and sexuality as incompatible. In addition, Alan's ad suggests that his desire for traits we associate with the disabled body broadly lay within the realm of fetish or kink by explicitly stating that his desire for someone disabled is "[n]othing kinky." In doing so, his ad reads as if his attraction to gay men with disabilities requires justification—reiterating ableist cultural expectations around masculinity, sexuality and desirability. Disability was not only made out to be an example of bodily "otherness," but as fetishized spectacles of abnormality. The dual narratives of asexuality and fetish articulate that bodies perceived to be disabled are not seen as being able to produce a sexuality in their own right but rather become desirable by the "kinky" sexual proclivities of non-disabled others.

The abnormality or fetishization of disability provided those writing for and reading TBP with a language and framework for understanding the effects of HIV/AIDS. Just as disability had been stylized in myriad ways for those reading TBP and writing its content, the HIV/AIDS body had been framed using similar language of debility or frailty. This articulation of disease was shaped by the same neo-liberalism and ardent individualism of the post-war era that witnessed the Baby Boomer generation experience historically unprecedented socio-economic mobility. Bodies were (and continue to be) expected to function in ways that facilitate and mobilize industrial capitalism, yet bodies that are disabled or diseased are often viewed as incapable of doing so despite some recent academic efforts to provide alternative valuations of disabled bodies in society. 45 The resulting stigma around disability and disease was exacerbated in a cultural hysteria with HIV/AIDS where transmission and life-expectancy were unknown in the early 1980s and fear-mongering was rampant both within the queer community and outside it.

TBP and the "Gay Cancer"

"Gay cancer" was a term many readers of TBP came across in September 1981. The newspaper reported that KS, a rare form of cancer, had been found among forty-one gay men, mostly in the New York City and San Francisco metropolitan areas. 46 The findings originally emerged on July 3, 1981, when Lawrence Altman of the New York Times published an article titled, "Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals." 47 This piece was then subsequently reprinted through the New York Times news service in hundreds of North American newspapers. TBP's editorial collective thought that the New York Times article was a means of sensationalizing gay culture. In an un-authored report in TBP, it was argued that the New York Times article misrepresented linkages between gay men and KS because there were numerous errors in Altman's approach to the unpublished work of Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien, which linked KS with gay men. 48 Lynch and others scrutinized what he dubbed, the "moral-medical right," for its crude and oppressive definitions of gay people that frequently linked homosexuality with mental or physical illness. 49 However, if any doubt about the disproportionate presence of KS in gay men still existed in late summer of 1982, it was dispelled in the July-August and September 1982 issues of TBP.

As the first reference to AIDS appeared—then referred to as ACIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) as well as GRIDS (Gay-related Immunodeficiency Syndrome)—it was reported that "[o]f the 300 cases reported across the United States, 242 are homosexual or bisexual men." 50 In September 1982, TBP writer Robert Trow informed readers that five cases of the disease had been reported in Canada. As a consequence to the controversial medical and media reports on the transmission and cause of AIDS, Trow noted a report in the July 1982 issue of The Gay Men's Health Crisis Newsletter, a New York City publication, stating that "the city's gay men are abandoning drugs and casual sex in droves, convinced that 'life in the gay fast lane kills.'" 51 For many gay men, AIDS became an epidemic that was already reshaping performances of masculinity and certain sexual practices which had once seemed ubiquitous in gay male culture, such as cruising, were now being re-evaluated by gay men.

Michael Lynch's coverage of his trip to visit Fred in New York City in the November 1982 issue was an important episode in verifying the morbid reality of HIV/AIDS. It is also a textual narrative of how the disease refashioned gay male masculinity and the gay male body. According to Lynch, Fred acquired a small support group led by his lover, Bruce, after being diagnosed with KS. He was dismayed, however, that many of his goods friends "stopped seeing us, even stopped bothering to call." 52 Lynch noted that Fred was resentful for feeling invisible and/or feared by those caught up in the hysteria of contagion. Coverage of the cultural effects of HIV/AIDS in the context of Fred was an important move away from discussing HIV/AIDS strictly as it pertained to medicine and renewed attempts to pathologize gay men's bodies. The emphasis placed on Fred's sense of invisibility, his body, and his appearance in Lynch's article turned what might be just an example of HIV/AIDS into one of the earliest cultural commentaries of the importance of the healthy body in gay male culture and the invisibility of bodies deemed to have failed.

When Lynch returned to New York City to visit Fred in the hospital, he noted that Fred "had lost half of his hair because of the chemo, and his skin was all broken out." By way of coping, Lynch, Bruce, and the others who stuck by Fred, used humour to soften the impact of the disease on his appearance. After Fred returned home, Lynch quipped that, "I don't think of Fred as having cancer anymore. I don't remember what he looks like with hair!" Throughout his bouts with chemotherapy and later battling tuberculosis, Fred linked his masculinity with his facial hair. In 1982, when Fred had finished his first round of chemotherapy, Lynch noted that he had "grown back his hair and, a source of great pride, his moustache." 53 For Fred to regain his moustache was to regain a sense of machismo, virility, a connection with gay culture, and a legible performance of gay masculinity, one rooted in white macho culture. White macho culture was a queer appropriation of clothing associated with the hypermasculine working-class, including tight jeans, white shirts, moustaches, and a macho demeanor, while also implicitly including whiteness and ableism. In stressing the significance of facial hair for Fred, Lynch's article was an evaluation of how HIV/AIDS might re-shape queer style, particularly the presentation of gay men's bodies in the community.

Coverage of Fred provided readers with an early insight into the cultural reverberations of the disease, touching on the social repercussions of centering gay culture on the white male body. The article was well-received by many readers, with some, such as Don Opper of Winnipeg, calling for greater coverage of mental and physical health in TBP. 54 More broadly, however, discussions of AIDS in TBP received varied reactions from readers. Jerry Rosco from New York City was supportive of Lynch's article on AIDS in March 1983. Meanwhile, Rich Grzesiak, Assistant Editor at Philadelphia Gay News, argued that TBP's article, "The Case Against Panic," in November 1982 was unfairly critical of American print media's coverage of AIDS. 55 The mixed reactions surrounding discussions of AIDS highlight the sensitive nature of the disease, particularly as it risked reshaping (and even eliminating altogether) activities and behaviours that had become synonymous with gay men's masculinity, such as cruising.

These varied responses to TBP's coverage of AIDS were also a result of the convoluted information around AIDS transmission in the early 1980s. During this time, gay men's bodies became a battleground between the conservative segments of society, the medical profession, and gay community politics. This was dubbed "AIDS panic" by Ed Jackson in March 1983. 56 AIDS sparked new questions and debates amongst readers around individual sexual choices, responsibility for personal wellbeing, and how gay men might restylize themselves to combat media portrayals of their bodies as frail, infected, "polluted," and even "disabled."

Intersections of Disease and Disability in TBP

In TBP, the AIDS-afflicted body was described in many instances using the language of disability. References to the unique debilitating effects of the disease established the healthy and sexual desirable figure as "normal" and the unhealthy and sexually undesirable subject as "abnormal" within the gay community. TBP reflected the tension between portrayals of gay men with AIDS that raised awareness of the disease and its debilitating effects, and the actions of men attempting to subvert stigmatized notions of their masculinity and sexuality. Gay men stylized their bodies in ways to subvert the heteronormative/ableist gaze on their "abnormal bodies," and labels of pollution and dread from both within and outside the gay community. Sociologists Kathy Charmaz and Dana Rosenfeld argue that visible effects of disabilities transform the disappearing body into the dysappearing one, whereby the body appears "dysfunctional to ourselves and to others." 57 In the case of gay men with AIDS, their bodies were highlighted for their inability to function—primarily sexually—as expected.

Lynch recalled the withering effects AIDS had on Fred's body in the March 1983 issue of TBP. He wrote: "Fred now was utterly weak, a skin-and-bones echo of the vibrant thirty-three-year-old redhead Bruce had met sixteen months before." In his description of Fred's death, Lynch included details that reinforced an aesthetic of AIDS for readers. Details, such as his lover Bruce straightening "the illness-thinned body on the bed," established in the reader's imagination an image of emaciation that has long been synonymous with disease. 58 In their monograph, Looking Queer, John De Cecco and Dawn Atkins quote gay activist Victor D'Lugin saying, "For a long time, outside and inside the community, the face of AIDS was the emaciated body." 59 The loss of muscle and subsequent undesirable thinness symbolized an absence of masculinity because emaciation was embedded in tropes of frailty and vulnerability, the opposite of muscularity and strength. When those who developed AIDS began to see their bodies waste away from the disease or a related illness, their ability to communicate strength, vitality, and masculinity through their body also seemingly disappeared and they began to perform a manifestation of deformance.

Historian Heather Murray argues that "[t]he physicality of AIDS went far beyond connotations and hints of contamination….Those with full-blown AIDS became shockingly disfigured." 60 The visible symptoms of AIDS led to those with the disease to experience a stigmatization similar to people who were perceived as disabled. 61 In this case, gay men with AIDS were distanced from those desiring to be "normal," or at least seen as unencumbered by the markings of disease or disability. Despite groups such as the AIDS Committee of Toronto (ACT) forming in 1983 and calling for greater financial, social, and political support for AIDS victims, AIDS reshaped understandings of desirability and sexual normalcy. Some men reportedly saw themselves as "lepers," disabled, or abnormal following their diagnosis. Others used TBP as a platform to vocalize a need for greater awareness and support and referred to their condition as one that resulted in their isolation from society.

In September 1983, Vancouver social worker Bryan Teixeira wrote an article on AIDS in TBP describing the symbolic meaning of AIDS in the gay community and how the disease was reshaping the social and sexual fabric of the gay male community. Inspired by Susan Sontag's reference to the leper as a social text for corruption in her book, Illness as Metaphor (1978), Teixeira argued that as long as AIDS was labelled a "gay disease," gay men were at risk of denying themselves the pleasures of gay sex and, in the process, condemning those with AIDS "not as brothers to be supported," but as "lepers to be denied." 62 Teixeira articulated how the AIDS-positive individual risked ostracism from the gay community as "AIDS indicates some small degree of contamination." 63 Indeed, these sentiments around bodily pollution and AIDS would be reiterated by Sontag herself in her 1989 monograph, AIDS and Its Metaphors (1989), where she contends that, "AIDS has a dual metaphoric genealogy. As a microprocess, it is described as cancer is: an invasion. When the focus is transmission of the disease, an older metaphor, reminiscent of syphilis, is invoked: pollution." 64 For those visibly affected with AIDS, such as Lynch's close friend Fred, the disease became an example of the health and social risks associated with promiscuity. 65

Becoming a pariah seemed to be the social consequences of the disease for 28-year-old Peter Evans, who described the social stigma he faced as a person with AIDS to Ed Jackson in an interview for TBP published in October 1983. After being diagnosed with AIDS in December 1982 while living in London, England, Evans's symptoms included Crohn's Disease as well as bouts of Psoriasis. The latter, and notably more visible symptom, led him to quit his job because people had begun to refuse his service as a waiter. Evans described the social repercussions he felt from having AIDS as the "leper approach." 66 After returning home to Ottawa between late 1982 and early 1983 because doctors in London felt incapable of treating him, Evans described feeling isolated from friends and family, society, and even other patients with AIDS during his time in hospital. 67

In the article "Going Public with AIDS," Jackson referred to Evans as "Canada's national person with AIDS" because he was one of the most outspoken advocates for HIV/AIDS research. 68 His interview with Evans served as another personal account, albeit politically driven, by TBP to undermine the invisibility of those affected by AIDS. Jackson's article was not just a commentary on mainstream society, but of the gay community itself, serving as a reminder that a new closet in the gay community formed when people with HIV/AIDS became hidden in hospital rooms or their private residences. Six months after going public, on January 7, 1984, Evans succumbed to the disease. His obituary in TBP by the AIDS Committee of Toronto (ACT) read, "Beyond grief, though, we are proud to have known Peter. He demonstrated to all Canadians that a person with AIDS has much to teach his friends, the general public, and those who have or live in fear of this syndrome." 69 Even in death, Evans was framed as an example that AIDS could cloak its hosts with stigma and fear.

In the June 1986 issue of TBP, writer Phil Shaw's review of Arthur Bressan Jr's 1985 film, Buddies, demonstrated how the arts could convey the horrific realities of HIV/AIDS while serving as a "mirror" for constructions of disease, sexuality, and race in gay male culture. The film follows a New York City gay man, David, who takes care of Robert, another gay man dying of AIDS. Friendships blossom as David acts as a "buddy" to Robert in his final days. 70 By arguing that the film accurately reflected the horrific realities of the gay community, Shaw's praiseworthy review simultaneously perpetuated HIV/AIDS as an issue for attractive, white gay men. This was a major point of consternation for Roger Bakeman, a reader and Ph.D. student in Atlanta, Georgia, who challenged the whiteness of AIDS by writing into TBP in March 1986. Bakeman argued, "Some people think that AIDS is just a white boy's disease. Since 25 percent of AIDS cases have occurred among blacks, another 15 percent among others (mainly Hispanic), and only 60 percent among whites, this is clearly not true." 71 The tension around how HIV/AIDS was visualized in TBP's news articles and cultural coverage as a white disease rather than one that affected all gay men situated the newspaper as a mediator between the imaginations and the actual realities of AIDS in the gay community. It also subsequently meant that the experiences of non-white gay men and those with disabilities with the HIV/AIDS were further marginalized and assumptions of their asexuality implicitly reinforced.

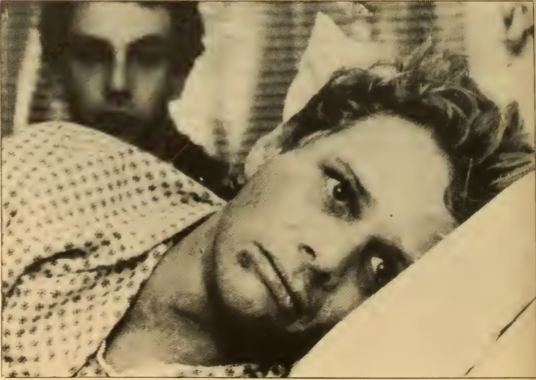

In Shaw's review of Buddies, he included an image of a man with AIDS who held a somber appearance with darkened eyes and a lesion under the lip (Figure 1). The face is an important part of the body in the context of AIDS because the disease's effects on it were difficult to cover from the gaze of onlookers. Murray argues that "[t]he faces of those suffering with AIDS, too, could be ravaged by the purple-brown lesions of Kaposi's sarcoma, as though gay men with AIDS carried the visual lacerations and markings of a perceived non-ascetic life." 72 These aesthetic elements, along with the hospital gown, create a style of AIDS—disheveled, sullen, and noticeably ill with corporeal markings of disease.

While the film created this image, TBP chose to include it in order to capture the horrific realities of HIV/AIDS on the gay male body. The film still photograph evokes a sense of hopelessness, frailty, and sadness that encapsulated wider discourses of disease, emasculation, disability, and undesirability. Despite the scene containing a healthy-looking young man in the background, perhaps to demonstrate the support or love that one may receive if diagnosed with the disease, the man dying from AIDS is foregrounded and appears lonely and internally isolated—evoking HIV/AIDS as a disease that renders gay men's bodies or even identities invisible or vastly marginalized. Thus, TBP's inclusion of this image exemplifies how the newspaper straddled reinforcing the undesirability of the AIDS body while simultaneously addressing stigmas of the disease.

The visualization of AIDS on the gay male body as disabled was most notably discussed in TBP after news broke that famous Hollywood actor Rock Hudson was diagnosed with AIDS in July 1985. Strewn across the front page of almost every tabloid, Hudson's health condition and more insidiously, his homosexuality, exemplified how HIV/AIDS and homosexuality could be portrayed in the media. Writing in TBP in December 1985, film scholar Richard Dyer argued that the revelation that "'virile,' 'muscular,' 'square-jawed,' 'masculine'" Rock Hudson was gay fundamentally challenged "US men's style of antiseptic machismo." 73 He stated that popular conceptions of masculinity and heterosexuality were not only defined by physical traits such as muscularity or a square jaw, but that those qualities resulted in "stable" and normative heterosexuality. Dyer stressed that straight conceptions of heterosexuality were artificial, using Hudson's ability to pass as a way to demonstrate that not all gay men were effeminate or weak.

Figure 1. Film still photograph used to illustrate Phil Shaw, "A celluloid valentine to the gay community," The Body Politic 127, June 1986, 32.

Challenging assumptions around gay male masculinity was important considering that before-and-after photos of the Hollywood actor risked portraying gay men as frail, weak, and emasculated. Positioning "Rock [as] healthy, strong, gorgeous in stills from films and in early pin-ups, side by side with Rock tired, haggard, tragic" represented a "chronology," according to Dyer. Hudson embodied this narrative by turning from a "healthy, strong, gorgeous" man while in the closet into a man whose masculinity and virility was lost to his homosexuality. Dyer best articulated how this chronology styled and was styled by gay masculinity when he said:

Such a juxtaposition of beauty and decay is part of a long-standing rhetoric of gayness. It is a way of constructing gay identity as a devotion to an exquisite surface (queens are so good-looking, so fastidious, so stylish, so amusing) masking a depraved reality (unnatural, promiscuous and repulsive sex acts). The rhetoric allows the effects of an illness gotten through sex to be read as a metaphor for that sex itself. 74

Dyer's analysis highlights the tension between the healthy male body, which is representative of heterosexuality, and the frail male body that is emblematic of homosexuality. Gay male style had not only been polarized between "beauty and decay" in the past but became increasingly so during the AIDS epidemic. In the context of the gay male community, the muscular, healthy male body offered a surface that both reflected cultural constructions of desirability and rebuked the "depraved reality" that gay sex potentially leads to the destruction or debilitation of gay men's bodies.

The editorial collective's attempts to qualm social anxiety about gay male sexuality were somewhat ineffective. While highlighting the very real stigma that those HIV/AIDS could expect to encounter, the personal accounts of Fred or Evans, or the artistic representation of AIDS in film were constructed as morbid narratives about the potential decline of the gay male body. The editorial collective seemed to replicate the language of disability when describing their AIDS-affected bodies. Framing these individuals in TBP as isolated in apartments or under medical observation communicated to readers that HIV/AIDS threatened to confine the gay male body in a similar manner to those perceived as disabled. Indeed, writing at the time of the AIDS epidemic, scholar Jeffery Weeks recorded first-hand the effects of AIDS on gay male style in his book, Sexuality in Its Discontents (1985). In it, he notes: "AIDS is a disease of the body, it wrecks and destroys what was once glorified." 75 That which was glorified, however, was the muscular, white, non-disabled body.

Conclusion

Within TBP, the similarities in depictions of people with HIV/AIDS and those perceived to be disabled entrenched an "abnormal" body in the gay community that buttressed a healthy "normal" one. In doing so, TBP reflects how the gay male body was a site of tension as discourses around disability and disease became further entangled in a world of HIV/AIDS. Stereotypes of asexuality and emasculation that had surrounded men with disabilities long before HIV/AIDS had partly extended onto non-disabled gay men in this new climate. The similarity in tropes of disability and disease when looking at masculinity as a style demonstrates that bodies perceived to no longer function as expected became restylized or rather, cloaked under similar discourses of health, sexuality, and ability.

Even nearing the end of TBP's publication in 1987, questions around the freedom of gay men's sexual and gender expression were raised amongst readers and the editorial collective alike. Over the course of the 1980s, the newspaper described the rapid development of anxieties both from outside and within the community around the regulation of sexuality and the gay male body. In a climate of social intolerance and fear around the health of gay men outside the community some gay men felt compelled to restylize themselves and their sexual lifestyles to something akin to heterosexual monogamy; some men did not. Nevertheless, gay male sexual practices such as cruising became increasingly scrutinized and positioned against healthy heterosexual "normalcy" that involved practices such as monogamy. Similar to other sexually transmitted diseases, HIV/AIDS brought with it significant discussions about the aesthetics of disease. But unlike those diseases discovered before it, HIV/AIDS centred on the gay male body and sparked apprehension around disability—resonating with Weeks's powerful quote that AIDS reduced what was one glorified or fetishized into an unsightly spectacle, often treated with indifference.

Bibliography

- Beam, Joseph. In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1986.

- Bost, Darius. Evidence of Being: The Black Gay Cultural Renaissance and the Politics of Violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

- Butler, Butler. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge Press, 1999 [1990].

- Charlton, James I. Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520925441

- Charmaz, Kathy, and Dana Rosenfeld. "Reflections of the Body, Images of Self: Visibility and Invisibility in Chronic Illness and Disability." In Body/Embodiment: Symbolic Interaction and the Sociology of the Body, edited by Phillip Vannini, 42-60. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Churchill, David. "Personal Ad Politics: Race, Sexuality and Power at The Body Politic." Left History 8, no. 2 (2003): 114-134. https://doi.org/10.25071/1913-9632.5514

- Clare, Eli. Exile and Pride: Disability, Queerness, and Liberation. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015 [1999]. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822374879

- Davis, Lennard J. Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body. London: Verso Press, 1995.

- De Cecco, John, and Dawn Atkins. Looking Queer: Body Image and Identity in Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay, and Transgender Communities. New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Fuchs, Don M. "Breaking Down Barriers: Independent Living Resource Centres for Empowering the Physically Disabled." In Perspectives on Social Services and Social Issues, edited by Jacqueline S. Ismael and Ray J. Thomlison, 187-200. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development, 1987.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

- Geczy, Adam, and Vicki Karaminas. Queer Style. London: Bloomsbury Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350050723

- Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre, 1956.

- Goodley, Dan. Dis/ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism. New York: Routledge, 2014. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203366974

- Harrison, Kelby. Sexual Deceit: The Ethics of Passing. Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2013.

- Hemphill, Essex. Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry. New York City: Plume Press, 1992; Jersey City, New Jersey: Cleis Press, 2000.

- Jarman, Michelle. "Dismembering the Lynch Mob: Intersecting Narratives of Disability, Race, and Sexual Menace." In Sex and Disability, edited by Robert McRuer and Anne Mollow, 89-107. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394877-005

- Jones, James H. Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. New York: The Free Press, 1981 [1993].

- Marks, Deborah. Disability: Controversial Debates and Psychosocial Perspectives. London: Routledge, 1999.

- McRuer. Robert. Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

- Mitchell, David T., and Sharon L. Snyder. The Biopolitics of Disability: Neoliberalism, Abelenationalism, and Peripheral Embodiment. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.7331366

- Murray, Heather. "Every Generation Has Its War." In Gender, Health, and Popular Culture, edited by Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, 237-257. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2011.

- Puar, Jasbir K. "Prognosis time: Towards a geopolitics of affect, debility, and capacity." Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 19, no. 2 (2009): 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/07407700903034147

- Rich, Adrienne. "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Experience." Signs 5, no. 4 (Summer, 1980): 631-660. https://doi.org/10.1086/493756

- Schweik, Susan M. The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public. New York: New York University Press, 2010.

- Siebers, Tobin. "A Sexual Culture for Disabled People." In Sex and Disability, edited by Robert McRuer and Anna Mollow, 37-53. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394877-002

- Sontag, Susan. AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989.

- -----. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978. https://doi.org/10.1017/S009700850000397X

- -----. Against Interpretation: And Other Essays. New York: Farar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

- Voelkel, Rebecca M. Carnal Knowledge of God: Embodied Love and the Movement for Justice. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1ggjhnm

- Walkowitz, Judith R. Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class, and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Weeks, Jeffrey. Sexuality and Its Discontents: Meanings, Myths, and Modern Sexualities. New York: Routledge, 2002 [1985].

Endnotes

-

The author would like to thank the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for funding this research at the doctoral and postdoctoral level.

Return to Text -

Michael Lynch, "Living with Kaposi's," The Body Politic 88, November 1982, 33.

Return to Text -

'"Gay' Cancer and burning flesh: the media didn't investigate," The Body Politic 76, September 1981, 19.

Return to Text -

Martin Duberman, Hold Tight Gently: Michael Callen, Essex Hemphill, and the Battlefield of AIDS (New York: The New Press, 2014), 154.

Return to Text -

See: Joseph Beam, In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology (Boston: Alyson Publications, 1986); and, Essex Hemphill, Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry (New York City: Plume Press, 1992; Jersey City, New Jersey: Cleis Press, 2000).

Return to Text -

Darius Bost, Evidence of Being: The Black Gay Cultural Renaissance and the Politics of Violence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 14. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226589961.001.0001

Return to Text -

See James H. Jones, Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment (New York: The Free Press, 1981 [1993]), 223.

Return to Text -

This term is the same as horizontal/lateral violence which consists of violence and/or tension that perpetuates oppression within a marginalized group. See: Rebecca M. Voelkel, Carnal Knowledge of God: Embodied Love and the Movement for Justice (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2017), 110. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1ggjhnm

Return to Text -

Eli Clare, Exile and Pride: Disability, Queerness, and Liberation (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999 [2015]), 108.

Return to Text -

Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York: New York University Press, 2006), viii.

Return to Text -

David Churchill, "Personal Ad Politics: Race, Sexuality and Power at The Body Politic," Left History 8, no. 2 (2003): 115. https://doi.org/10.25071/1913-9632.5514

Return to Text -

Lennard J. Davis, Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body (London: Verso Press, 1995), xv.

Return to Text -

Adrienne Rich describes compulsory heterosexuality as "a manmade institution…as if, despite profound emotional impulses and complementarities drawing women toward women, there is a mystical/biological heterosexual inclination, a 'preference' or 'choice' that draws women toward men. Adrienne Rich, "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Experience," Signs 5, no. 4 (Summer, 1980): 637. https://doi.org/10.1086/493756

Return to Text -

Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas, Queer Style (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2013), 4. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350050723

Return to Text -

Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation: And Other Essays (New York: Farar, Straus and Giroux, 1966), 36.

Return to Text -

Kelby Harrison, Sexual Deceit: The Ethics of Passing (Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2013), 115.

Return to Text -

See Erving Goffman, Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. (1965; revised ed., New York: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1959).

Return to Text -

Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge Press, 1999 [1990]), xv.

Return to Text -

Butler, Gender Trouble, 140.

Return to Text -

Susan M. Schweik, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 48.

Return to Text -

Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 6.

Return to Text -

Dan Goodley, Dis/ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism (New York: Routledge, 2014), 95. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203366974 See: Jasbir K. Puar, "Prognosis Time: Towards a Geopolitics of Affect, Debility, and Capacity," Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 19, no. 2 (2009): 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/07407700903034147

Return to Text -

Gerald Hannon, "No sorrow, no pity," The Body Politic 60, February 1980, 19.

Return to Text -

James I. Charlton, Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 58. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520925441

Return to Text -

Michelle Jarman, "Dismembering the Lynch Mob: Intersecting Narratives of Disability, Race, and Sexual Menace," in Sex and Disability, eds. Robert McRuer and Anne Mollow (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 92. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394877-005

Return to Text -

Tobin Siebers, "A Sexual Culture for Disabled People," in Sex and Disability, eds. Robert McRuer and Anne Mollow (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 39. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394877-002

Return to Text -

Hannon, "No sorrow, no pity," 21.

Return to Text -

"Stair trek: nightlife by wheelchair," The Body Politic 60, February 1980, 22.

Return to Text -

Hannon, "No sorrow, no pity," 21.

Return to Text -

Don M. Fuchs, "Breaking Down Barriers: Independent Living Resource Centres for Empowering the Physically Disabled," in Perspectives on Social Services and Social Issues, eds. Jacqueline S. Ismael and Ray J. Thomlison (Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development, 1987), 193.

Return to Text -

Hannon, "No sorrow, no pity," 19.

Return to Text -

"Stair trek: nightlife by wheelchair," 22.

Return to Text -

John Allec and Edna Barker, "Hot Spots: Toronto's Summer of 82," The Body Politic 85, July-August 1982, 22.

Return to Text -

Hannon, "No sorrow, no pity," 22.

Return to Text -

See Deborah Marks, Disability: Controversial Debates and Psychosocial Perspectives (London: Routledge, 1999); and, Clare, Exile and Pride (1999).

Return to Text -

Hannon, "No sorrow, no pity," 22.

Return to Text -

Fo Niemi, "Support for disabled," The Body Politic 74, June 1981, 5.

Return to Text -

Classified ad: Wilf Race and Chris, "Gay and Disabled," The Body Politic 73, May 1981, 40.

Return to Text -

Warren D. Camp, "Not disabled," The Body Politic 98, November 1983, 6.

Return to Text -

Camp, "Not disabled," 6.

Return to Text -

Classified ad: Scott, "GWM, 30, Good-looking," The Body Politic 83, May 1982, 41.

Return to Text -

Classified ad: Richard, "Very Huggable Person," The Body Politic 84, June 1982, 42.

Return to Text -

Classified ad: "Gay Male, 23, 6'1"," The Body Politic 67, October 1980, 41.

Return to Text -

Classified ad: Alan, "Toronto/Belleville/Ottawa," The Body Politic 109, December 1984, 40.

Return to Text -

David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, The Biopolitics of Disability: Neoliberalism, Abelenationalism, and Peripheral Embodiment (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015), 27.

Return to Text -

'"Gay' Cancer and burning flesh: the media didn't investigate," 19

Return to Text -

Lawrence K. Altman, "Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals," New York Times, July 3, 1981, A20.

Return to Text -

'"Gay' Cancer and burning flesh: the media didn't investigate," 19.

Return to Text -

Lynch, "Living with Kaposi's," 35.

Return to Text -

"Kaposi research hurt by cutbacks," The Body Politic 85, July-August 1982, 16.

Return to Text -

Robert Trow, "AID disease reported in Canada," The Body Politic 86, September 1982, 14.

Return to Text -

Lynch, "Living with Kaposi's," 34.

Return to Text -

Lynch, "Living with Kaposi's," 35.

Return to Text -

Don Opper, "Physical Pain, mental anguish," The Body Politic 89, December 1982, 4.

Return to Text -

Jerry Rosco and Rich Grzesiak, "AIDS alternatives," The Body Politic 91, March 1983, 4.

Return to Text -

Ed Jackson, "Red Cross: resisting AIDS panic," The Body Politic 91, March 1983, 17.

Return to Text -

Kathy Charmaz and Dana Rosenfeld, "Reflections of the Body, Images of Self: Visibility and Invisibility in Chronic Illness and Disability," in Body/Embodiment: Symbolic Interaction and the Sociology of the Body, ed. Phillip Vannini (New York: Routledge, 2016), 46.

Return to Text -

Michael Lynch, "This Seeing the Sick Endears Them," The Body Politic 91, March 1983, 36.

Return to Text -

John De Cecco and Dawn Atkins, Looking Queer: Body Image and Identity in Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay, and Transgender Communities (New York: Routledge, 2012), 351.

Return to Text -

Heather Murray, "Every Generation Has Its War," in Gender, Health, and Popular Culture, ed. Cheryl Krasnick Warsh (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2011), 245.

Return to Text -

McRuer, Crip Theory, viii.

Return to Text -

See Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978), 6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S009700850000397X

Return to Text -

Bryan Teixeira, "AIDS as Metaphor," The Body Politic 96, September 1983, 40.

Return to Text -

Susan Sontag, AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989), 17.

Return to Text -

The social stigma tied to AIDS stemmed from notions of bodily "pollution" that had emerged in the last two centuries alongside an obsession with hygiene, purity, and personal cleanliness. These were associated with morality and social stability, and as Judith Walkowitz argues, an attempt to curtail the corruption of the repectable working and middle classes. Judith R. Walkowitz, Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class, and the State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 34.

Return to Text -

Ed Jackson, "Going public with AIDS," The Body Politic 97, October 1983, 28.

Return to Text -

Jackson, "Going public with AIDS," 29.

Return to Text -

Jackson, "Going public with AIDS," 28.

Return to Text -

Obituary: "Peter Evans (April 20, 1955 - January 7, 1984), The Body Politic 101, March 1984, 10.

Return to Text -

Phil Shaw, "A celluloid valentine to the gay community," The Body Politic 127, June 1986, 32.

Return to Text -

Roger Bakeman, "Not colour specific," The Body Politic 124, March 1986, 11.

Return to Text -

Murray, "Every Generation Has Its War," 245.

Return to Text -

Richard Dyer, "Rock: The Last Guy You'd Have Figured?" The Body Politic 121, December 1985, 27.

Return to Text -

Dyer, "Rock: The Last Guy You'd Have Figured?" 29.

Return to Text -

Jeffrey Weeks, Sexuality and Its Discontents: Meanings, Myths, and Modern Sexualities (New York: Routledge, 2002 [1985]), 50.

Return to Text