This paper mobilizes activist art at the intersections of disability, non-normativity, and Indigeneity to think through ways of decolonizing and indigenizing understandings of disability. We present and analyze artwork produced by Vanessa Dion Fletcher, the first Indigenous disability-identified Artist-in-Residence for Bodies in Translation (BIT), a research project that uses a decolonized, cripped lens to cultivate disabled, D/deaf, fat, Mad, and aging arts on the lands currently known as Canada. We begin by setting the context, outlining why disentangling the disability, non-normativity, and Indigeneity knot is a necessary and urgent project for disability studies and activisms. Drawing on Indigenous ontologies of relationality, we present a methodological guide for our reading of Dion Fletcher's work. We take this approach from her installation piece Relationship or Transaction?, which, we argue, foregrounds the need for white settlers to turn a critical gaze on transactional concepts of relationship as integral to a decolonized and an indigenized analysis of disability and non-normative arts. We then centre three original pieces created by Dion Fletcher to surface some of the intricacies of the Indigeneity/disability/non-normativity nexus that complicate recent discussions about recuperating Indigenous concepts of bodymind differences across white supremist settler colonial regimes on Turtle Island (North America) that seek to debilitate Indigenous bodies and lives. We intervene in these debates with reflections on what might be created—and what we might learn—when the categories of Indigeneity and (Western conceptions of) disability and non-normativity are understood as contiguous, particularly focusing on meaning-making within Dion Fletcher's developing oeuvre.

Introduction

Anishinaabe artist-scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, in her book Dancing on Our Turtle's Back, describes the convergence of art, activism, and everyday life. As she stories a public procession of her Nishnaabeg community of dancers, artists, drummers, community leaders, Elders, and children walking down the main street in the city currently known as Peterborough, Ontario, art is not only part of everyday life; art is everyday life. For Simpson, the celebration of Indigenous culture by First Nations Peoples is a way of taking up space and taking back space on stolen land in acts of resistance. Simpson describes, "Settler-Canadians poking their heads out of their houses, restaurants, and offices, staring at them from the sidelines, their looks saying, 'what do they want this time?'" (9). Simpson writes, "But that day we didn't have any want—we were not trying to fit into Canada. We were celebrating our nation and our lands in the spirit of joy, exuberance, and individual expression" (9). Simpson's story teaches us, if we attend closely, something important about Anishinaabe artistic expression and ontologies of difference. In her accounting, neither the very young nor the old are excluded due to perceived and/or experienced vulnerabilities, needs or in/capacities. Instead, they play a vital part in Indigenous cultural expression as it weaves into the fabric of daily life, and they take up space on colonized land that is violently inhospitable to Original Peoples.

In this essay, we offer one account of how we are working to decolonize disability through activist art by exploring selected works produced by our project's 2018-19 Artist-in-Residence of Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology and Access to Life (hereafter Bodies in Translation or BIT), Indigenous disability-identified artist Vanessa Dion Fletcher (Potawatomi- Lenape). Briefly, BIT is a multifaceted arts research project that cultivates disabled, D/deaf, fat, Mad, and aging arts using a decolonizing and cripped lens in order to engage with multiple community-institutional partners. BIT started with a compelling idea: that creating both access to art for non-normatively embodied people and opportunities for the public to engage with such art would expand understanding of non-normative vitality and advance social and political justice in Canada. Our project is led by Indigenous and non-Indigenous e/Elders, 2 scholars, artists, and activists in our governance structure, research and artistic activities, and decolonizing disability, non-normative and activist art is central to our work. We interrogate what activist arts can teach about disabled lives at the intersections of Indigeneity, disability and non-normativity. We do this by experimenting with ways of decolonizing disability and non-normative arts in a variety of genres (performance, visual art, film, installation, digital media) and by creating opportunities for various publics to engage with such work.

Our commitment to 'decolonizing disability through activist art' began when we wondered about the multiple ways in which the experience of disability informs and complicates the project of decolonizing, as we examine in this essay. While we recognize that we need to decolonize disability studies, activisms and arts, we also appreciate how knowledge and creative production from bodies and minds of difference can advance the project of decolonizing. In what follows, we begin unpacking this syllogism by giving background on the complexities of thinking Indigeneity, disability, and non-normativity together. Here we explore why it is vitally important to examine art at this nexus through an indigenizing lens that seeks to recover and recuperate Indigenous concepts of bodymind difference as well as a decolonizing one that surfaces and challenges some of the egregious effects of settler colonial systems that aim to debilitate Indigenous bodies and nations. Drawing from Indigenous ontologies of relationality, we introduce our methodological guide taken from reading Dion Fletcher's installation piece, Relationship or Transaction?. We then move to offer a relational reading of three more of Dion Fletcher's works, Offensive/Defensive, Own Your Cervix, and Finding Language. In our reading of these works which surface some of the intricacies of the Indigeneity/disability/non-normativity nexus, we consider how knowledge and creative production from an Indigenous perspective on "what Western discourses call disability" (Kuppers 175) might support decolonization. We end by suggesting that a relational reading of Dion Fletcher's developing oeuvre reveals the work required to make old/new sense of disability in a colonized world that debilitates Indigenous peoples.

Thinking through the Disability/Indigeneity/Non-normativity Nexus: New/Old Meanings of Disability and Worldly Arrangements

Our Bodies in Translation work is situated in Ontario, with many of our activities occurring on the traditional territories of the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee nations. When we started this project, we knew that we had a responsibility both to work in relationship with Indigenous peoples and to respond to the call by Indigenous scholars and activists to decolonize our research (Truth and Reconciliation Commission/TRC, 1-22). Along with taking up our responsibilities to work for and in solidarity with Indigenous self-determination efforts, we wanted to explore how cultivating activist arts at the intersections of disability and Indigeneity might contribute to decolonize disability in ways that are consonant/resonant with Indigenous worldviews and perspectives. Thus, we briefly outline decolonizing research that evidences some of the debilitating effects of white settler colonial structures on Indigenous peoples before turning to outline Indigenous scholarship that aims to recuperate Indigenous concepts of bodymind difference. Through focusing attention on white settlers' responsibilities in redressing colonial conditions, we surface some of the complexities that complicate any simplistic call for disability pride or for recuperating pre-contact ways of knowing non-normativity.

In the testimonies of disabled and of Indigenous peoples, we can identify how similarities and overlaps in the state's egregious treatment of both groups has served the geopolitics of settler-colonial nation building. These overlaps include settler imposition of political and economic regimes that have produced high degrees of debility (Puar X; 17; 20) and disability among Indigenous peoples. The imposition of ableist settler knowledge systems have sought to render Indigenous and disabled populations as defective and inferior; settler transinstitutional responses to Indigenous and disabled bodies, centering mainly on policies of containment and elimination have had violent and deadly effects for Indigenous and non-normative lives. Yet these resonances are complicated by a formidable rub: notions of 'defectiveness' that have been imposed on Indigenous people through colonial knowledge regimes have meant that the ascription of disability, madness, fatness, or other forms of non-normativity doubly or multiply threatens Indigenous peoples' access to the category of the human. This makes the claiming of disability or non-normativity itself a privilege.

Colonization processes including genocide, war, and land theft along with the imposition of Western laws and logics have been, and continue to be, powerful determinants of debility and disability among Indigenous peoples globally (Puar 1-33; Grech and Soldatic 2-4). Profound inequities in all areas of social, political and economic life have devastated Indigenous populations for generations across formerly colonized and settler colonial nations, resulting in disproportionate rates of impairment and early death (Allan and Smylie 4-12; Lovern 307). Impairments range from psychic distresses caused by colonial trauma to physical impairments related to body and land dispossession, war, unfettered capitalism, unsafe living environments, and inadequate health care (Kelsey 197-203; Senier 215-219). In Canada, Australia, the US, and other settler colonial nations, the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from traditional territories and resources combined with intentional exposure to communicable disease and environmental toxins due to nuclear weapon testing, strip mining, chemical processing, and insecticide spraying near Indigenous reserves/communities have led to high rates of cancers and impairments; and colonizing processes such as the containment of Indigenous peoples on reserves with poor living environments that are moreover cut off from traditional food sources have resulted in a high prevalence of diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic conditions in populations (Gilroy et al 1026-1027). As a result, the rate of disabilities experienced by Indigenous people in Canada is twice that of non-Indigenous people (British Columbia Aboriginal Network on Disability 2).

Indigenous people grapple with the same Western logics for understanding disability as non-Indigenous people do. Yet the impacts of these have been magnified for Indigenous peoples due to how notions of 'defectiveness' have been imposed on Indigenous communities through colonization, especially via scientific knowledge. For example, in settler nations such as Canada, administrators, physicians, and scientists, in the process of claiming the land and its peoples, have and continue to frame Indigenous peoples as impaired and defective as a way to justify colonial violence (Gilroy 1027). Since the invasion of Indigenous lands, settler-elites have categorized Indigenous bodies and cultural practices in the same ways they have cast disabled ones: as deficient relative to a Euro-white non-disabled mythical norm. Governments have mobilized these arguments to rationalize continued violence against both groups including through forced confinement (residential schools, asylums) and elimination (starvation, forced assimilation, normalizing treatments, eugenics), practices that have had devastating effects for Indigenous and non-normative lives, and for the intergenerational transfer of culture (Kelly et al 12-33). To offer some examples, at the height of the asylum era in the 1970s, Canada had 41 institutions for people labelled with developmental disabilities (not including psychiatric institutions) with many more institution-like programs for people with diverse disabilities run by charities and municipalities (Brown and Radford 16); at the peak of the residential school system in 1931, 80 Indian Residential Schools operated, with the last one closing in 1996 (TRC 3). With respect to the custodial power and carceral control of institutions in their work to eliminate 'problem' populations over the last 150 years of nation-building, settler scholar Jay Dolmage examines how anti-immigration eugenics rhetoric and policies have cast immigrants, especially racialized ones, as "disabled upon arrival" (1). Along the same line of research, settler scholar Karen Stote has tracked the sterilization of Indigenous peoples, demonstrating how they were classified as mentally unfit as a precursor to sterilization (138-142).

In contrast to these logics, through our arts-based research, we are learning that Indigenous peoples have had radically different ways of understanding non-normativities. For instance, Dolleen Tisawii'ashii Manning (Anishinaabe), a lead researcher on Bodies in Translation, argues that the deficiency-based concept of disability was not part of an Anishinaabe worldview nor did it exist within Anishinaabe communities prior to the imposition of Eurocentric colonizing knowledges. This is also echoed in our conversations with Bodies in Translation Wisdom Keeper, Anishinaabe Elder Mona Stonefish. Indigenous scholars such as Penelope Kelsey (Seneca) (195-196), Lavonna Lovern (Cherokee) (309-315), and Hollie Mackey (Cheyenne) (6-9) concur, arguing that for Indigenous peoples dismantling ableism principally involves recuperating Indigenous ontologies that may not perceive abnormality to exist, and creating systems that embrace decolonized perspectives and enact inclusion/ reincorporation of bodies of difference into the Indigenous body politic. For Kelsey, decolonizing disability entails both resistance to colonial logics and reclamation/ revivification of Indigenous modes, which reflect the "continuity of embodied kinship in the past, present, and future" (195). This view of decolonization does not pivot on individuals' overcoming disability (which values disability only to the extent that it can be transcended) but instead focuses on the fight for "corporeal and cultural survival" (196), a turn which foregrounds healing from colonial trauma and genocide while affirming Indigenous disabled lives as integral to the social body. Lovern argues that neo/colonial processes principally produce(d) disability and its oppression globally. It follows that achieving disability justice for Indigenous peoples requires the decolonization of bodymind difference and the reclamation of Indigenous thought systems, which assert that all "beings are created correctly and that differences are a means of gathering knowledge both for the individual and for the community" (314). Thus, as these scholars contend, revitalizing Indigenous paradigms may be critical to dismantling colonial ableism within the Canadian context and globally.

Given these fraught histories and their reverberating legacies, we approach the Indigeneity, disability, and non-normativity nexus through a reciprocal exchange of ideas, pedagogies, frameworks, and worldviews. Attending to activist art, we ask: how do Indigenous ways of knowing bodymind difference disrupt settler-colonial logics which inform the binary division between the categories of 'disability' and 'nondisability'—categories that seek to 'know' us, separate us, oppress us? And how does disability studies' theorizing of ableism and of the ways both that ableism is distributed and intersectionally is felt help us to understand, and resist, the specific modes of oppression that Indigenous people who identify or are coded as disabled confront? Dion Fletcher's artwork sits in this nexus. And since her art practice is an embodied and embedded one, her thoughtful, nuanced exploration brings new meaning to this coming-together—meaning that we think can only arise through artistic practice and product. The meanings we generate from Dion Fletcher's work may be related to how disability art generally and her work specifically speaks in more than one dialect; written and spoken words feature prominently in her work but Dion Fletcher also enunciates in other visceral and vividly symbolic tongues. Body fluids and medical exams figure in her projects, as do scavenger hunts, porcupine quills, and five-dollar bills. As we have witnessed during exhibitions and performances, the multiple sensory registers along which her work communicates enhances its aesthetics of accessibility and the objects and actions with which she works carry yet-to-be and not-languagable metaphoric and metonymic associations that evoke strong affective responses in audiences. The (im)possibilities of communication and by extension, of relationship across multiple differences emerge as a recurring theme in her work.

Relationship or Transaction? Methodological Notes on Decolonizing Disability Arts

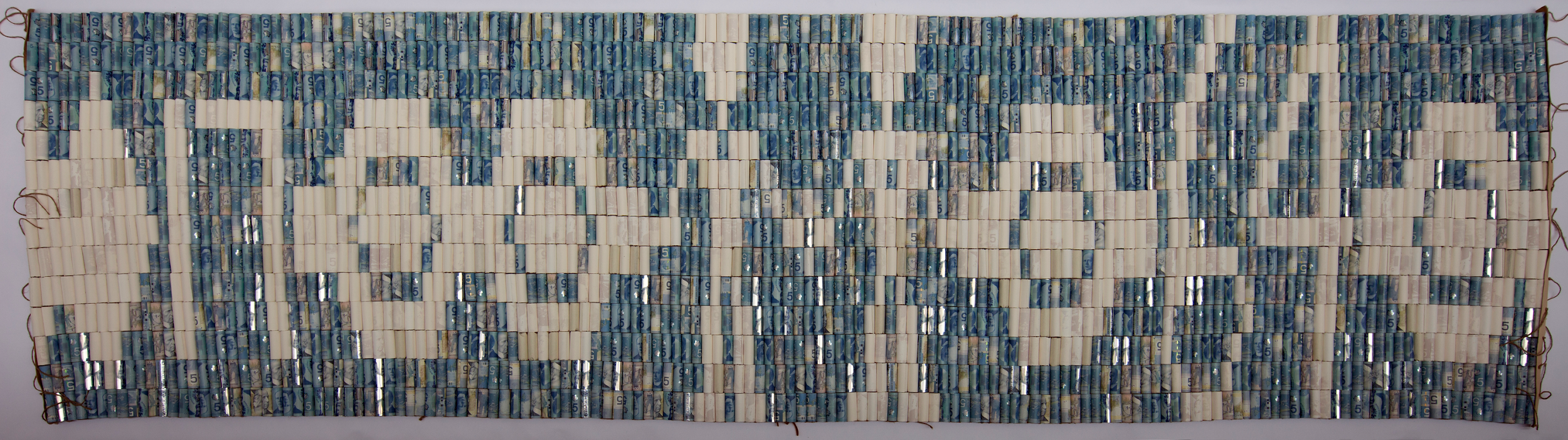

Figure 1: Relationship or Transaction?, Vanessa Dion Fletcher, 2014 3

We begin with Dion Fletcher's Relationship or Transaction? 4 (2014) because it teaches us something important about the primacy of relationality in Indigenous ontologies and hence the kind of relationships we need to enter into, ethically, politically and affectively, in order to engage with and learn from her work. She (2014) describes her installation as follows: "This belt depicts two figures holding hands in the center flanked by pentagons and the date 1764. [The] reproduction is made using $5 bills as the quwahog (purple) beads and replica $5 bills as the whelk (white) beads". She created an eight-foot-long by four-foot-wide replica of the 1764 Western Great Lakes Covenant Chain Wampum Belt, known by colonizers as the Treaty of Niagara between the British and 24 Indigenous Nations (Borrows 155), using close to 2000 five-dollar Canadian bills (Figure 1). Dion Fletcher rolled the 2000 blue Canadian five-dollar bills and white replica bills to look like wampum beads, the cylindrical beads that the Lenape and other Indigenous nations whose territories spanned the eastern seaboard of Turtle Island carved from the dark purple and whitish parts of clam shells using stone drills and water. She chose to remake this Wampum because the Treaty of Niagara was a formative treaty in what would become Canada (Borrows 155) (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Relationship or Transaction? Vanessa Dion Fletcher, 2014 5

Figure 3: Relationship or Transaction? Vanessa Dion Fletcher, 2014 6

When settler colonizers entered into agreements such as those encoded in the Covenant Chain Wampum, they mistook the wampum beads as currency (Haas 80; Morcom 130-131). Dion Fletcher thus uses money in crafting the belt to jolt people into thinking anew about the nature of the treaty relationship—not as a finite transaction that begins and ends when people exchange money, lands, and resources but rather as an open-ended agreement, in which people enter into living relationships and commit to upholding certain values, rights, and responsibilities as an integral part of maintaining those relationships. This resonates with Leanne Simpson's description of her Nishnaabeg nation in relationally monistic terms, as "the web of connections to each other, to the plant nations, the animal nations, the rivers and lakes, the cosmos, and our neighboring Indigenous nations… an ecology of intimacy… based on deep reciprocity, respect, noninterference, self-determination, and freedom" (8). In drawing attention to white settlers' instrumentalist orientation to the world, Relationship or Transaction? gestures toward settlers' consuming and extractive tendencies rooted in a white supremist neoliberal, consumerist mindset that has, since contact, operated as a powerfully destructive force in Indigenous-settler relations (Fowlie and Rice 1-33; Rice and Mündel 2018 119-121). The work thus offers important commentary on a profound rub between settler and Indigenous worldviews: between those premised on atomism, utilitarianism, and capitalism, which instrumentalize activities and things according to their perceived usefulness and reduce almost all exchanges of the resulting "goods and services'' to commodified transactions; and those premised on relational holism or monism, which recognize the inherent interconnectedness and value of all people and things and emphasize a shared responsibility for sustaining good relations, with both the human and non-human worlds.

Encountering Dion Fletcher's work, white settlers cannot escape their failure to uphold this and many other treaties, and their ensuing consumption of Indigenous lands, people, ideas, and spiritualities. Ample historical evidence shows that settlers verbally agreed to certain terms in treaties with Indigenous peoples while writing documents with different key terms that advanced only settlers' interests, thus betraying the trust of their Indigenous co-signers (Obomsawin). Within the Canadian context, settler colonial governments continue to evade their treaty obligations and while many settlers have become aware of the state's egregious treatment of Indigenous peoples, few are willing to work through the complex problematics of land repatriation that decolonization requires (Rice, Dion, Fowlie, & Breen 3-5). Dion Fletcher's work teaches us that we have to decolonize disability as a concept, and this necessarily means white settlers seeing themselves in and working toward transforming relationships with Indigenous peoples, and disabled/ and non-disabled people from both groups, working, thinking and feeling across difference in our engagements with each other and with art-making at the intersections. Relationship or Transaction? reminds us of our embeddedness in a broader historical, social, and material context, and white settlers especially of the enduring fact that if we live on colonized land, here and elsewhere, we are in relationship with Indigenous peoples, whether or not we know or acknowledge this reality.

For us, following Wampum teachings means enacting accountable relationships in our scholarly work, which means acknowledging our relationalities with Indigeneity, disability, and non-normativity and of assuming responsibility for the well-being of these relationships as living entities. To that end, I, Susan Dion, am a Potawatomi-Lenape scholar who has been working in the field of Indigenous education for more than thirty years. My research focuses on decolonizing and realizing Indigenous education, urban Indigenous education, and methods of developing respectful relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. I work closely with school boards and community organizations to address Indigenous issues. I, Carla Rice, am a white settler living with mental difference who has an extended family of Indigenous kin. Through disability arts research, I have come to know my non-normativity experientially and relationally, and to experience the power of art to interrupt ableist colonial ontologies and enact, if fleetingly, other possible worlds. I, Eliza Chandler, come into disability arts and culture as a proud disabled woman invested in giving new ontological meaning to disability. I believe that disability artists can enact new worldly arrangements in which disability means and matters differently. As I pursue this project, however, I think with Indigenous art and other worldmaking projects and consider how my desire uncomfortably aligns with the colonial desire for a new world—a desire implicit in Indigenous genocide and its effects. In this colonial context, I must ask myself, is my place to work towards a 'new world'? Or must I instead work in solidarity with Indigenous Elders, scholars, and artists in service of re-establishing Indigenous sovereignty and of returning to the past as we look forward to the meanings we might want disability and non-normativity to hold?

In addition to these positionalities, two of us, Susan and Carla, are family, one being mother and the other step-mother, and the third, Eliza, being a colleague-friend to Dion Fletcher. We ask readers to consider how love, care, and commitment in our varied relationships inform the analysis that follows and consider how these bonds might strengthen our capacity to see and learn from her work. To illustrate, when she was three years old, Vanessa articulated her experiential understanding of disability, stating, "Mommy there are some boxes in my brain that don't open." She was only three years old, yet her experience of living in her body informed her understanding. While some might consider close relationships between researcher-scholars and 'subject' to be detrimental, we work from the position that strong relationships can have positive impacts on knowledge production. Consider how our subjectivities and positionalities allow us to make meaning of Dion Fletcher's work.

Undoing the Colonial Ordering of Things

Using a relational lens, we explore three of Dion Fletcher's more recent works: Own Your Cervix (2017) mounted at the Tangled Art + Disability Gallery in Toronto, a performance piece titled Offensive|Defensive (2017) at the Centre for Contemporary Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and a third performance, Finding Language: A Words Scavenger Hunt (2019) developed during her time as the BIT Artist-in-Residence. It is helpful to think with settler art historian Carla Taunton's words, specifically "storytelling and embodied practices are essential components of Indigenous ways of knowing and being" (34), as we think through what Dion Fletcher's work might surface about the Indigeneity-disability nexus. Rather than analyzing how these (and other) differences intersect (which assumes differences are discrete, separable categories), we explore how they intrasect or, in keeping with Indigenous and other processual ontologies, materialize in more emergent, entangled, and embodied terms in Dion Fletcher's practice (Rice 537; Rice, Jiménez, et al 185-187; Rice and Mündel 2019 216; Rice, Harrison and Friedman 416-417), and consider how they clarify one another and co-mingle in indeterminate ways. Because Dion Fletcher's embodiment, and thus her embodied practices, cannot be siphoned off into separate parts, we take up all her work, even work that doesn't specifically address disability, as animating this nexus.

Own Your Cervix

Figure 4: Colonial Comfort and Beading Works, works part of Vanessa Dion Fletcher's Own Your Cervix exhibition, 2017 7

Own Your Cervix (2017) is a solo, multi-media exhibition that Dion Fletcher has held in different venues. On her website, Dion Fletcher describes Own Your Cervix as a project that

[U]ses porcupine quills, glass beads, damask patterns and menstrual blood to consider how our bodies are defined physically and culturally. A Western progress narrative often assumes an irrelevance of a feminist practice, but we will never be done making meaning of our gendered and cultured bodies. Furthermore, a feminist body practice is far from irrelevant in current social and political contexts (para 1). 8

Dion Fletcher shared with us that putting this exhibition into a disability arts space, namely Tangled Art + Disability Gallery in Toronto, Canada, helped it to find its audience. In other spaces, audience members had read the work as derivative of second-wave feminist preoccupations and focused mainly on its Indigenous elements as a new, intriguing intervention into feminist art's exploration of body politics. They especially commented on an arresting artifact that grounded the show: a blood-stained cream-colored damask Victorian-style settee with real porcupine quills stuck in and around a few bloody stains at one end of the piece (Figure 2). Why a Victorian style sofa? What did its bloody stains and quills mean? We might relate to the pleasing/menacing piece as a material object reminiscent of the comforts of the Victorian home, focusing on what it might signify about colonial-Indigenous gender relations—how it might stand in as a bloody reminder of the ways that such 'comforts' were/are premised on the violent regulation, control, and destruction of Indigenous women's bodies and of Indigenous families and nations.

At Tangled, in contrast to other spaces, audiences became conscious of how nuanced ideas about accessibility—about accessibility as political, as a practice, as an aesthetic—were central to the show. For example, Dion Fletcher constructed an examination 'room' in the gallery by suspending white curtains from ceiling to floor so that she could invite visitors to sign up for artist facilitated self-examinations in the privacy of a curtained-off space. Featured in the exam room was a low examination table designed for ease of transfer for those using mobility devices and for anyone who has difficulty hoisting themselves onto pelvic examination tables (which typically are designed for the ease of physician, not of patient, use); a low hung mirror that could be positioned so that sighted patrons might visually access their orifices and non-visual patrons have these audio described if they wanted; and variously sized speculums were available so that those with vaginas, cervixes, and associated body parts could touch, handle, and use the technologies to investigate and come to know their unique crevasses/openings. These elements prompted visitors to consider how accessibility might be better understood as a multifaceted concept—as always political, entangled with everyday practices, implicated in design and aesthetics, and as such, as perhaps better conceived in the plural, as accessibilities.

Following the tradition of disability justice activist Mia Mingus (2011), 9 Dion Fletcher's orientation to accessibility elevates it from being strictly a logistic concern into a political consideration of how entanglements of normative, medicalized, and colonial spaces and practices invite some bodies in and exclude other bodies. With Own Your Cervix, Dion Fletcher creates a world in which we can all get to know our bodies, reclaim, even own our bodies, in a cripped space in which we are called upon to think about the impacts of colonialism on Indigenous women's and trans and Two-Spirit bodies. Dion Fletcher's work prompts us to wonder: What is the relationship between accessibility, desire, and bodies? Why aren't women, trans, and gender-fluid people able to easily access their cervixes, vulvas, and other sex-coded organs as sites which foster the coming together of sexual health, autonomy, and pleasure? How might this lack of access adversely affect differently-located, and especially Indigenous disabled people? How might the meanings given to body parts coded as female, disabled, or trans debilitate persons so coded in a world that doesn't give us permission to access or know these parts/processes? By locating Own Your Cervix in the space of a disability art gallery, and therefore contextualizing it through the lens of disability art, a space and politic familiar with questioning how we come to know our own and others' bodies in particular ways, Dion Fletcher's installation was able to breathe new life into old debates; here, bodies are "stolen and reclaimed" (Clare 359-360 ) not just by medical authority, but in particular by how westernized medical authority is a colonial tool, one that participates in patriarchal colonial theft.

In our conversations with visitors, those familiar with Indigenous histories and cultures told us that they saw the row of seven embroidery rings hung on a crimson wall, Beading Works, each featuring a beaded blood stain, as a celebration of Indigenous womanhood. Some disabled and Indigenous visitors interpreted the porcupine quills that pierced the Victorian sofa as signifying the imagined threat posed by Indigenous and disabled women's wombs to white ableist settler nation-building. In an article Dion Fletcher wrote about her show, she speaks of how her entangled identities mark and surface in the settee piece:

I read this phrase that talked about the Victorian Era as being one of 'colonial comfort.' It just really resonated with me because those two words don't at all go together for me, as an Indigenous person. There is nothing comfortable about colonialism. So, I thought about whose comfort we are speaking to and then I also thought about the ways that Indigenous peoples and disabled people continue to persist against these kinds of 'comfortable' norms. And I see the menstrual blood as a kind of representation of the possibility of fertility, and the possibility of future generations of Indigenous children, as bleeding onto the couch, in a sense 'staining' it. That was the first alteration that I made to the sattee 10 after I had it upholstered in the white fabric. (168)

In Own Your Cervix, the idea of coming to 'know your cervix' takes on multiple meanings. We might interpret the invitation to know your cervix as an invitation to know yourself, to know your gender, to know your Indigeneity, to know your disability. We might consider Dion Fletcher's re-invigoration of second-wave feminist body politics that inspired self-examination and activist art focused on gendered/sexed embodiment as capturing what is critical at this intersectional, that is, cripped and decolonial Indigenous feminist moment: as a means of giving herself (and us) permission to access and come to know her (and our) differences, to affirm and honor difference in its many symbolic and material forms.

Offensive|Defensive

Figure 5: Offensive|Defensive , Vanessa Dion Fletcher, 2017 11

We begin our discussion of Offensive|Defensive (2017) with Dion Fletcher's artist statement about the performance piece that was part of the 'Cry'in Out Loud' group exhibition in Santa Fe:

Porcupine quills were used before the introduction of glass beads, dyed and embroidered onto clothing, moccasins, etc. To be used, the quills needed to be soaked and flattened; in the old days women would soak them in their mouths and pull them out through their teeth to flatten them. I wanted to feel the same thing my people did years ago. I can't speak my language, but I can fill my mouth with quills, like words I'll never know. I hold them on my tongue, wanting to choke a little out of sadness, but not letting myself. Placing the quills in my mouth, I inhibit my ability to speak. Approaching people one by one maintaining eye contact I slowly remove the quill from my mouth and offer it to them. This intimate gesture builds a temporary connection between us. I repeat this gesture cycling through the audience, replacing the quills in my mouth as I go. 'Cry'in Out Loud' in English is inherently colonial; with little access to my Indigenous languages, I sometimes find power in silence. (para. 2)

Looking at the images from this performance we are struck by two moments: first is the moment of exchange and second is the moment of holding. The moment of exchange occurs when Dion Fletcher takes a quill from her mouth and hands it to an audience member. The quill holds remnants of her saliva, her DNA; it is sharp and possibly hazardous. Dion Fletcher describes this experience as an "intimate gesture [that] builds a temporary connection" (para. 2). She offers the quill and people accept it. This moment of exchange requires trust as it is imbued with her relationship with the quill. For Dion Fletcher, each quill is precious, signifying both the solace it provides "choking on the words I'll never know" and connection "feeling what my ancestors felt" (para. 1). For us, this is a moment of compelling implication. Having accepted the offer, audience members are now in a relationship with the quill, with Dion Fletcher, and with the relationship that exists between the two. Although it may only last for a moment, for that moment, audience members experience implication.

The second moment of particular interest is the moment of holding. As a witness to this performance, I, Susan, see the discomfort and confusion audience members experience when they realize they are left holding the quill, and they do not know what to do with it. They know something about the quill: it has been in Dion Fletcher's mouth. It seems precious, somehow important, yet people are left feeling confusion and discomfort. I think that because Dion Fletcher has challenges with written communication, she creates these encounters where she's communicating without language. By not using language—by operating outside of a recognizable narrative—she creates the possibility for audience members to step outside of their dominant narratives. Possibility exists in that rupture because she structures the moment of communication so they can't rely on the taken-for-granted because their taken-for-granted isn't her taken for granted.

In my, Susan's, most hopeful reading of this performance, I like to think that audience members leave with an understanding of themselves in relationship with a gendered, colonized, ablest society. In my less-hopeful moments, I think at the very least they leave somewhat confused, disrupted, with remnants of my child's DNA on a porcupine quill in the bottom of their pocket. One day when they least expect it, they will reach into the pocket and the spirit of the porcupine, the spirit of our ancestors will poke their fingertip and a tiny pain felt on the tip of the finger will make them think again about the woman who finds comfort in silence and what it means to be implicated in relationship.

Finding Language: A Word Scavenger Hunt

Figure 6: Finding Language: A Word Scavenger Hunt, Vanessa Dion Fletcher, 2019 12

The final piece we engage is Dion Fletcher's performance Finding Language: A Word Scavenger Hunt (2019), which she developed as part of her BIT Artist-in-Residence and performed at the Cripping the Arts symposium 13. Finding Language animates Dion Fletcher's multi-layered relationship with spoken and written languages as a Potawatomi-Lenape artist who is seeking out her traditional and sleeping Lenape language (called 'Delaware' by colonizers), and as someone who identifies as learning disabled. This performance begins with audio of her grandmother's voice filling the room. The voice begins by telling family stories, in a mix of Lenape (?) and English, from the past and then goes on to describe the process of getting older, becoming disabled, becoming dependent. Overlaid is audio of a little girl who is softly singing in what might be a traditional Indigenous language, perhaps in Lenape. As the audio ends, Dion Fletcher turns her focus on the Delaware-English/English-Delaware dictionary she is holding in her hand. As she begins to read aloud from this dictionary, it becomes clear that it offers distinctly colonial translations of the Lenape language; this tool does not allow her access to her Lenape language directly.

Figure 7: Finding Language: A Word Scavenger Hunt, Vanessa Dion Fletcher, 2019 14

With dictionary in hand, she sets out on a 'words scavenger hunt' around the room. She roams through the audience in the large room in which we are gathered in search of written words. As Dion Fletcher finds English words, which are plentiful, she translates them into the Lenape language using her dictionary. And the translations she finds are surprising, contentious, revealing. Take, for example, her discovery of a tote bag with multiple spellings of the English word 'women' - 'wimmin', 'womin', 'wimmyn.' Dion Fletcher slowly reads out these different spellings of the word phonetically and then turns to her dictionary. As she is thumbing her way through the English side of the dictionary in order to find the Delaware translation, she reads aloud other surrounding words: "White, white snow, be white, witch, hm." Tension rises as the weight of colonialism's disappearance of Indigenous language fills the room. She finds the word 'women' and reads aloud its related forms: "Indian woman, Delaware woman—that's me!—white woman, schoolteacher, bad woman, good-for-nothing woman, woman with poor character […] Old woman, fat woman, be a bad woman, be a good-for-nothing woman, older single woman, hm." Tension rises again.

At this point in the performance, unless you know Dion Fletcher and/or her work, you might (rightly) read this work as making public a young, urban, Indigenous person's quest for her Indigenous language on stolen land, a language that has been violently disappeared by colonialism through the residential school system and other forms of cultural genocide, a language that is now fragmentally accessible through a colonial lexicon. But as Dion Fletcher performs her scavenger hunt, she invites the audience into part of her experience of this performance, telling us: "I like to listen. I don't actually like reading, I'm not sure why I chose a performance where I'm reading the dictionary but—I guess we all do things we don't like to do sometimes", adding another layer of complexity. Reading Dion Fletcher's artist statement 15 for this work reveals another layer of how an intermingling of identities and experiences informs her work. She writes, "I've lost my words. Some of them are stuck in little boxes in my brain—drawers that won't open. Some of them are in the mouths of my Indigenous ancestors" (para. 1).

Throughout this performance, Dion Fletcher tries to find her Lenape language. She easily, though perhaps uncomfortably, has unfettered access to English, the language of colonization, and the written word, the medium through which her learning disability surfaces, as this performance demonstrates. She can hardly take a step before encountering another written word, another English word. But to access the language and oral tradition of her people requires her, at least in part, to use a colonial tool, the English-Delaware dictionary. And within it, she can hardly take a step before encountering colonial racism, misogyny, fatphobia, and ableism within its translation—or perhaps interpretation. Dion Fletcher positions this work as streaming from many of her experiences, including her experiences of disability. As she writes in her artist statement, "This work stems from my experience of language, colonization, and disability, however, these reflections or investigations are relevant to many people" (para. 1). However, she does not use medicalized terms or settler-colonial logic when describing her disability and the way that it impacts how she accesses language. Instead, she describes her experience with words and written languages as "loosing words" through multiple and perhaps inter-related processes of words stuck in shut boxes in her head and words stuck in the mouths of her Indigenous ancestors. Her work prompts us to consider, in a way that only art can do, that the stuck-ness of words in her head and words on her ancestor's tongues as being part of the same process. Colonialism has disappeared Lenape, an oral language, Dion Fletcher's Indigenous language, and in the wake of this disappearance, and in line with colonial rule, English, a written language, rose as the dominant language. Finding Language addresses the ways that she has lost her language through the imposition of settler-colonialism and struggles to orient to the language of settler-colonialism, a written language, because of the ways she delivers and receives language.

Finding Language presents audiences with compelling questions and insights about the meanings of disability in Indigenous and non-Indigenous contexts. Dion Fletcher provokes us to consider how the meaning of her learning disability, which emerges as she encounters the written word, is impacted by the context of her original oral culture having been disappeared through colonial genocide. If we consider how disability is experienced by and through colonialism, as it does in Dion Fletcher's case, how does this change our understanding of ontologies of bodymind differences? Moreover, Dion Fletcher is producing her work in relation to disability art. In so doing, how does Dion Fletcher invite us to think through recuperating her Lenape culture with and through her experience with her disability, which is more than the experience of ableism and inaccessibility but, instead, vital to her experience of the world. This reminds us of Kelsey's framing of decolonizing as the "continuity of embodied kinship in the past, present, and future" (195), as mentioned above. In bringing together these threads, Dion Fletcher is identifying the implicatedness of colonization and colonial ways of knowing in producing non-normativity while maintaining the value of disability within, and Kelsey writes, the fight for "corporeal and cultural survival" (196). In doing so, Dion Fletcher's art disrupts colonial understandings of bodymind difference and leads to decolonizing understandings of disability and its phenomenological meaning in and of the world.

To thicken our analysis, we return to Simpson who writes about the Nishnaabeg creation story and specifically about her and her children's experience of hearing that story.

Elders teach us that this most beautiful, perfect lovely being was not just any 'First Person,' but that it was me, or you. We are taught to insert ourselves into the story. Gzhwe Mnidoo created the most beautiful, perfect person possible and that most beautiful, perfect person was me, Betasamosake. … Every time I tell my children this story, or they hear this part of it in ceremony, their faces light up. It re-affirms that they are good and beautiful and perfect the way they are. (41)

The story teaches us that within Nishnaabeg thought we are accepted without judgement; further, by inserting ourselves into the story we accept responsibilities to our human and nonhuman relations "according to our own gifts, abilities and affiliations" (41). Unconditional acceptance of each of us is balanced, in turn, by our unconditional acceptance of our responsibilities to others and all of creation. Dion Fletcher can only dream of this place as she, and we, live in a colonized world where the need to categorize, judge, and create hierarchies of value are ever present. None of us can know how she or any of us would experience what we currently call disability in a decolonized world because that world does not exist. Dion Fletcher willingly puts her life/self under a microscope—or speculum—inviting viewers to look/learn from her experience as Lenape-xkwe (woman) living with disability in an ableist colonized world. Her art invites us to see the constructed barriers—in language, knowledge systems, values, environments, and beyond—that diminish her human-ness and her capacities to participate fully, to fulfill her responsibilities. Her art is thus an encounter with the hard work required of Indigenous (and non-Indigenous) peoples to make old/new sense of disability in a colonized world that debilitates Indigenous bodies; in so doing her work creates the potential for us to learn anew with her. We must pay attention to the ways in which the world we have inherited/constructed impedes our embrace of difference as it impedes our access to expanded possibilities to fulfill our responsibilities.

Conclusion

In Bodies in Translation, we are led by and think with art that brings together Indigeneity, disability, and non-normativity in a way that breathes new meaning into this nexus. In many ways, ours is an impossible project; it confounds in how we seek to understand an intersection—disability and Indigeneity—that we cannot rightly or ethically know. Given the number of nations across Turtle Island with their own thought systems, languages, and cultural practices, it is likely that Indigenous peoples, even amongst themselves, carried diverse understandings of complexly embodied people and of what constituted illness, impairment, and wellbeing. This fact overlaid with five centuries of colonial cultural, social, and physical genocide means that accessing the worldviews of Indigenous peoples in all their complexity and diversity remains an ongoing, challenging project.

As we inhabit the seemingly impossible space of desiring to know the unknowable, we are once again presented with an opportunity to be led by activist art as we are developing new understandings, a practice that is unwaveringly at the centre of Bodies in Translation. In this paper, we explore and learn from the work of Dion Fletcher in our pursuit of bringing Indigenous and disability frameworks together. We do this in order to think about what might be created when these categories are understood and approached as contiguous. When we attend to the three works discussed in this paper—Own Your Cervix, Offensive/Defensive, and Finding Language—both as individual works and a body of works, we arrive at a few thoughts. First, Dion Fletcher's work helps us move beyond the binary division between body and theory through the embodied practice of her work (Taunton 34), revealing the body as a primary site for knowing embodied difference. Second, this work brings an Indigenous ontological framing of bodymind difference, moving away from the deficit model of disability. Third, Dion Fletcher's work exemplifies how our bodily knowledges are stolen from us by colonial (including medical) regimes in broader projects of subjugation and how reclaiming knowledge of our bodies through our own embodied sense contributes to the broader project of resistance and Indigenous resurgence. Furthermore, the work is demonstrative of how Indigenous artists, such as Dion Fletcher, who address disability and non-normativity in their work productively teach us to question our terms as ontological facts, open to old/new concepts of disability that help us to recuperate Indigenous pasts, redress debilitating todays in order to enact decolonized futures for bodymind differences, and strive to practice relationality as a way of doing justice. All of this makes her practice a striking example of activist art that contributes to decolonizing understandings of disability and non-normativity.

References

- Allan, Billie, and Janet Smylie. First Peoples, Second Class Treatment: The Role of Racism in the Health and Well-being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Toronto: Wellesley Institute. 2015. Print.

- Borrows, John. "Wampum at Niagara: The Royal Proclamation, Canadian Legal History, and Self-Government." Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equality, and Respect for Difference. Ed. Michael Asch. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997. 155-72. Print.

- British Columbia Aboriginal Network on Disability Society. National Indigenous Federal Accessibility Legislation Consultation. Report. 2017. Print.

- Brown, Ivan, and John P. Radford. "The Growth and Decline of Institutions for People with Developmental Disabilities in Ontario: 1876-2009." Journal on Developmental Disabilities 21.2. (2015): 7-27. Print.

- Clare, Eli. "Stolen Bodies, Reclaimed Bodies: Disability and Queerness." Public Culture 13.3. (2001): 359-366. Print. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-13-3-359

- Dion Fletcher, Vanessa. "About the 'Own Your Cervix' Exhibit." Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 8.1. (2019). 164-69. Web 26 July 2019. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v8i1.476

- Dion Fletcher, Vanessa. "Relationship or Transaction." Vanessa Dion Fletcher, 2014, https://www.dionfletcher.com/relationship-or-transcation.

- Dolmage, Jay. Disabled Upon Arrival: Eugenics, Immigration and the Construction of Race and Disability. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2018). Print. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1h45mm5

- Fowlie, Hannah, and Rice, Carla. "The Need to Consume." Settler-Colonial Studies. (under review). 1-33.

- Gehl, Lynn. The Truth that Wampum Tells: My Debwewin on the Algonquin Land Claims Process. Halifax: Fernwood, 2014. Print.

- Gilroy, John, Angela Dew, Michelle Lincoln, Lee Ryall, Heather Jensen, Kerry Taylor, Rebecca Barton, Kim McRae, and Vicki Flood. "Indigenous Persons with Disability in Remote Australia: Research Methodology and Indigenous Community Control." Disability & Society 33.7. (2018): 1025–45. Print. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1478802

- Grech, Shaun, and Karen Soldatic. Disability in the Global South: A Critical Handbook. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2016. Print. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-42488-0

- Haas, Angela "Wampum as Hypertext: An American Indian Intellectual Tradition of Multimedia Theory and Practice." Studies in American Indian Literatures 19.4. (2007): 77-100. Print. https://doi.org/10.1353/ail.2008.0005

- Dion Fletcher, Vanessa 2018. Artist's Statement. Hobbs, M., & Rice, C. (Eds.). Gender and Women's Studies: Critical Terrain. 2nd Edition. (pp. ii-iii). Canadian Scholars'/Women's Press.

- Kelly, Evadne, Dolleen Tisawii'ashii Manning, Seika Boye, Carla Rice, Dawn Owen, Sky Stonefish, and Mona Stonefish. "Elements of a Counter-Exhibition: Excavating and Countering a Canadian History and Legacy of Eugenics." Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 57.1 (2021): 12-33. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbs.22081

- Kelsey, Penelope. "Disability and Native North American Boarding School Narratives." Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 7.2 (2013): 195–211. Print. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2013.14

- Kuppers, Petra. "Decolonizing Disability, Indigeneity, and Poetic Methods: Hanging Out in Australia." Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 7.2. (2013): 175–93. Print. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2013.13

- Lovern, Lavonna L. "Indigenous Perspectives on Difference: A Case for Inclusion." Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 11.3. (2017): 303–20. Print. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2017.24

- Mackey, Hollie. "Towards an Indigenous Leadership Paradigm for Dismantling Ableism." Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal 14.3. (2018): 1–12. Web 25 July 2018.

- Manning, Dolleen Tisawii'ashii. "Off the Cuff: Mnidoo Infinity Squeezed through Finite Modulations." Thinking Spaces: The Improvisation Reading Group and Speaker Series, 5 April 2018, Art Gallery of Guelph, Guelph, ON. Keynote Address.

- Morcom, Lindsay. "Indigenous Holistic Education in Philosophy and Practice, with Wampum as Case Study." Foro de Educación 15.23. (2017): 121-138. Web 23 October 2018. https://doi.org/10.14516/fde.572

- Obomsawin, Alanis, director.Trick or Treaty?, National Film Board of Canada, 2014, www.nfb.ca/film/trick_or_treaty/.

- Puar, Jasbir. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017. Print. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822372530

- Rice, Carla. "The Spectacle of the Child Woman." Feminist Studies 44.3 (2018): 535-66. https://doi.org/10.15767/feministstudies.44.3.0535

- Rice, Carla. and Mündel, Ingrid. "Storymaking as Methodology: Disrupting Dominant Stories through Multimedia Storytelling. Canadian Review of Sociology 55.2. (2018), 211-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12190

- Rice, Carla and Ingrid Mündel. "Multimedia Storytelling Methodology: Notes on Access and Inclusion in Neoliberal Times." Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 8.1. (2019), 118-48. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v8i1.473

- Rice, Carla, Elisabeth Harrison, and May Friedman. "Doing Justice to Intersectionality in Research." Cultural Studies<–>Critical Methodologies 19.6 (2019): 409-20.https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708619829779

- Rice, Carla, Karleen Pendleton Jiménez, Elisabeth Harrison, Margaret Robinson, Jen Rinaldi, Andrea LaMarre, and Jill Andrew. "Bodies at the Intersection: Refiguring Intersectionality through Queer Women's Complex Embodiments." Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 46.1. (2020a), 177-200. https://doi.org/10.1086/709219

- Rice, Carla, Dion, Susan, Fowlie, Hannah, and Breen, Andrea. "Identifying and Working Through Settler Ignorance." Critical Studies in Education (2020b): 1-25. Ahead of print: https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2020.1830818

- Senier, Siobhan. "Traditionally, Disability Was Not Seen as Such." Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 7.2. (2013): 213–29. Print. https://doi.org/10.3828/jlcds.2013.15

- Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. Dancing on Our Turtle's Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence and New Emergence. Winnipeg: Arbeiter Pub, 2011. Print.

- Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Print. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1pwt77c

- Stote, Karen. An Act of Genocide: Colonialism and the Sterilization of Aboriginal Women. Halifax: Fernwood, 2015. Print.

- Taunton, Carla. "Performing Sovereignty: Forces to be Reckoned With" More Caught in the Act, Eds. Johanna Householder and Tanya Mars. Toronto: Artexte, 2016. 34-55. Print.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Web 6 June 2015.

Endnotes

-

We wish to thank the anonymous reviewers whose feedback helped us to attune and strengthen our argument presented in this paper. We acknowledge Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology, and Access to Life, a research project funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#895-2016-1024), the research project that supports our collective work. We are also indebted to Vanessa Dion Fletcher for her art that inspires our thinking and engages us in the work of decolonizing disability art and the ontology of disability itself.

Return to Text -

We use the term "E/elder" to include both Indigenous Elders and Non-Indigenous elders, recognizing that in Anglo-Western cultures the term senior, for some communities, has pejorative connotations and that in Indigenous cultures, "Elder" is a respected title bestowed not as a result of age but rather as a result of one's knowledge and actions. Indigenous Elders are recognized knowledge keepers who have earned the respect of their communities and nations through demonstrating wisdom, harmony and balance in their actions and their teachings.

Return to Text -

Image Description: A close up of Vanessa Dion Fletcher's piece Relationship or Translation?. The image features five rows of blue and white Canadian five-dollar bills that are rolled and packed closely together in a style reminiscent of a Wampum Belt.

Return to Text -

https://www.dionfletcher.com/relationship-or-transcation

Return to Text -

Image Description: An image of Vanessa Dion Fletcher's artwork, Relationship or Transaction? Dion Fletcher kneels in a gallery in front of a small crowd of people. The is lifting up a gold-colored blanket on top of which is the large wampum belt, in a blue and white pattern, which she wove using rolled Canadian five-dollar bills.

Return to Text -

Image Description: An image of Vanessa Dion Fletcher's artwork, Relationship or Transaction? A large wampum belt woven with white patterning on a blue background. Rather than being made of wampum beads, the blue parts of the belt are comprised of rolled Canadian five-dollar bills.

Return to Text -

Image description: An image of Vanessa Dion Fletcher's artwork, Own Your Cervix. In this image, a couch stands in front of a red wall in a gallery space. The couch is ornate, covered in white damask with brown wood detailing. Clusters of porcupine quills stick out of the couch, arranged mostly on the sides and back of the couch. On the wall behind the couch, seven fabric circles of varying sizes of the same white damask fabric are arranged in a line; each circle has a streak of blood on it.

Michelle Peek Photography courtesy of Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology & Access to Life, Re•Vision: The Centre for Art & Social Justice at the University of Guelph.

Return to Text -

https://www.dionfletcher.com/project-07

Return to Text -

See: https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/02/12/changing-the-framework-disability-justice/

Return to Text -

The ways that Dion Fletcher spells is part of her art. We honour her modes of expression and believe that to do otherwise would entail an act of epistemic violence. As she has written: "As an Indigenous woman, I learned the ways that language was used to alienate and oppress my family, my ancestors, and the ways it continues to oppress me, both as a cultural experience and a disabled experience." (2018, p iii)

Return to Text -

Dion Fletcher, an Indigenous woman, holds open her mouth full of porcupine quills. She is adding another quill to the pile.

Return to Text -

Image description: An image of Vanessa Dion Fletcher's performance, Finding Language: A Word Scavenger Hunt. In this image, Dion Fletcher, an Indigenous woman, is beginning her performance by lying on her back on a low stage. She is wearing black shoes, gold-colored leggings, a black jacket, and glasses. Her hands are placed on her abdomen.

Michelle Peek Photography courtesy of Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology & Access to Life, Re•Vision: The Centre for Art & Social Justice at the University of Guelph.

Return to Text -

Co-sponsored by BIT, Cripping the Arts was a symposium and performing arts festival which explored contemporary issues related to the cultivation of disability, Deaf, and mad arts. The relationship between Indigenous and disability arts—a relationship skillfully explored in Dion Fletcher's work—was one of the central themes of this symposium and festival.

Return to Text -

Image description: An image of Vanessa Dion Fletcher's performance, Finding Language: A Word Scavenger Hunt. In this image, Dion Fletcher, wearing black shoes, gold-colored leggings, a black jacket, and glasses, crotches down in front of an audience member who is holding out a tote bag. There are multiple spellings of the word women on this bag. With one hand, Dion Fletcher is pointing to the spelling of the English word that is in focus in this photograph: wommin. In her other arm, Vanessa is holding her English-Delaware dictionary. Her cellphone, which she is using to capture the words she finds and projects them onto a large screen in front of the audience, is strapped around her neck. Vanessa is looking at the words on the tote bag through her cellphone.

Michelle Peek Photography courtesy of Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology & Access to Life, Re•Vision: The Centre for Art & Social Justice at the University of Guelph.

Return to Text -

See www.dionfletcher.com

Return to Text