The 1970s were an important decade for disability policy in Britain. The 1970 Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act promised services for all disabled people and a series of cash benefits appeared to comprise a national disability income. By the 1980s, however, these measures had failed, and some disabled people had taken radical stances against the perceived failures of capitalism. This article shows that radical views amongst disabled people began earlier and were more common than has been assumed. It examines Peace News, a prominent activist publication, as evidence of this phenomenon. Disabled people in the 1970s became radicalised in response to traditional failures of British welfare and recent failures of the welfare state. They self-identified as a minority group—alongside homosexuals and ethnic minorities—and fought against discrimination. Unlike major disability organisations in the 1970s, disabled people had a militant approach to improving their welfare and their position in the welfare state.

Quotations in this article are as they appeared in Peace News.

Introduction

This article examines a 1976 issue of Peace News, a prominent activist publication, largely written by disabled people. These writings show how disabled people in the 1970s perceived their welfare and the ineffectiveness of the post-war welfare state. Major disability organisations in the 1970s were critical of the welfare state's failure to address disabled people but were moderate and had good relations with the government. This article argues that disabled people had radical views in the 1970s before they became widespread in the 1980s. Disabled people became radicalised in response to the failures of the 1970 Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons (CSDP) Act and the cash benefits of the 1970s. They also became radicalised because of discriminatory practices embedded in the tradition of British welfare. Disabled people perceived themselves as an oppressed minority group in company with homosexuals and ethnic minorities. As the welfare state was receding, disabled people sought the independence it had withheld. This article engages with literature on disability, policy, and welfare to place its analyses within the wider framework of disability and the welfare state.

After the excitement and optimism of the 1960s, the 1970s were foreboding in Britain. It seemed to be the worst time since the unemployment and uncertainty of the inter-war period. There was the recession of 1973–75 that ended the post-war economic expansion. With its conservation of electricity, the three-day week in 1974 darkened the national mood. Many began to question the Keynesian system that had prevailed since the Second World War as is evident in studies such as The Fiscal Crisis of the State, Crisis '75…?, and Capitalism in Crisis (O'Connor 1973; Hicks et al. 1975; Gamble and Walton 1976). The Labour government abandoned the policy of full employment in 1975. Inflation rose to 27 per cent and unemployment reached 1.5 million in 1976 (Lowe 317–18). With the Conservatives moving toward neoliberalism, and the Labour left pushing for central planning, increased taxation, and nationalisation, many worried about the country's fractured political culture. Trade unionists were choosing extra-parliamentary means. Ethnic tensions reached new heights. Infrastructure and public services were crumbling. There was violence: bombings, shootings, and assassinations in Northern Ireland and mainland Britain (see Morgan 2017). It was in this climate that disabled people fought against discrimination and for recognition and rights.

Some studies of disability and welfare in the 1970s described how the cash benefits did not improve disabled people's welfare (see Loach 1977; Simkins and Tickner 1978; Topliss 1979). Many also condemned the CSDP Act as a failure (see Knight and Warren 1978; Topliss and Gould 1981; Wright 1977). Vic Finkelstein and Paul Hunt, founders of the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS), offered perspectives based on the social model of disability (Finkelstein 1972, 1975, 1980; Hunt 1966; UPIAS 1974, 1976). A great deal of work on disability as a social problem was produced when the social model became powerful in the 1980s. There were also the contributions of scholars of 'emancipatory disability research' (Oliver 1992). This progressive sociological school joined activism and scholarship to combat the social, cultural, and physical factors that impede disabled people. In Disability and Social Policy in Britain since 1750 (2004), Anne Borsay said that the CSDP Act offered inadequate services that reached a small portion of disabled people (195–96). Further historical work on disability in the 1970s analysed policy and politics including Labour and the Conservatives, civil servants and government, organised labour and employment, and major organisations including the Disability Alliance and the Disablement Income Group (DIG) (Gulland 2017; Hampton 2016; Millward 2015; Sainsbury 1995; Thomas 2011; Walker 2010). Sonali Shah's and Mark Priestley's work connected biography with policy and examined the stories of young disabled people growing up in the welfare state (2011).

This article contributes to the state of knowledge on disability in the 1970s by examining the perspectives of disabled people at the end of a welfare state that most often failed to address their welfare. It analyses Peace News to lend to a better understanding of the cultural history of the 1970s and the forces behind changing perceptions of disability. Further, the article deals historically with the independent voices of disabled people who were not speaking with the support of an organisation.

Disability and the Welfare State

Those disabled people who were not entitled to war pensions received little direct provision in the welfare state settlement of the 1940s. Unlike disabled ex-servicemen, there was no public or emotional sentiment from the experience of the Second World War and no tradition of special statutory provision. Few disabled people qualified for cash benefits under the 1946 National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act, and legislators thought that formal voluntary efforts, and the informal efforts of families, friends, and communities, would support disabled people. The 1944 Disabled Persons (Employment) Act also helped very few. The 1950s, however, saw an important shift away from the Poor Law, which was abolished in 1948, to the state engaging with disabled people in other ways. Parties inside and outside government began to consider new disability schemes including cash benefits, and there was an emphasis on the 'promotional welfare' of disabled people through local services (Hampton 73). Yet, much of the statutory welfare for disabled people was institutional and based on individual pathology definitions of disability: tens of thousands of disabled people remained in NHS 'chronic sick' wards and in local authority residential homes (Barnes 1991 23, 130).

Overall, the idea that the welfare of disabled people should and would come under the increasing responsibility of the state grew stronger in the 1950s, and there was public indignation about their welfare (Webster 222). The 1959 Mental Health Act furthered the movement against institutions and highlighted the welfare of all disabled people. So too did The Last Refuge (1962), Peter Townsend's study of institutions for disabled and elderly people. By the early 1960s, there were some statutory services for disabled people in every locality in England and Wales. The potential for significant policy development did not occur until the late 1960s. Yet, in the early 1960s, there was the view that disabled people would and should receive increased statutory welfare.

The welfare of disabled people was part of the 'rediscovery of poverty,' an international phenomenon in the 1960s. In Britain, it was the publication of Brian Abel-Smith's and Townsend's The Poor and the Poorest (1965) that drew attention to groups that remained deprived in a period of affluence. This was an exciting time for welfare with the liberalisation of British society and a new Labour government in 1964 after 13 years of Conservative rule. Disabled people did not receive new cash benefits in the 1960s but made important gains in recognition. Founded in 1965, DIG became a powerful pressure group and was the first organisation that sought to represent all disabled people. Labour and the Conservatives, the Trades Union Congress, and the public at large became aware that disabled people were neglected by the welfare state settlement of the 1940s. Disability issues were discussed in the media and the House of Commons, and government made plans for new provision. Disability had become a policy and political issue, and disabled people were perceived as deserving of increased statutory welfare. Further, the desirability of cash benefits emerged alongside services in addressing the welfare of disabled people (Hampton 119–21).

While the 1960s brought changes in perception, in the 1970s, disabled people were part of the 'revolution of expectation.' Hailed as 'a Magna Carta for the Disabled,' the CSDP Act was to provide comprehensive services to all disabled people. DIG sought to embarrass the Conservative government (1970–4) about the comparatively poor state of British disability provision as Britain was about to join the European Economic Community. Concurrently, disability continued to grow as a policy and political issue, especially with the 1972–3 thalidomide crisis. Successive governments were politically compelled to create some sort of legislation for disabled people. The Labour governments (1964–70) developed an attendance allowance, and the subsequent Conservative government introduced its own attendance allowances and the Invalidity Benefit under National Insurance. The Labour governments (1974–9) introduced several cash benefits, and they promised meaningful improvements in the welfare of disabled people. Taken together, the cash benefits and services under the CSDP Act seemed to be the reversal of disabled people's exclusion from the welfare state settlement of the 1940s. DIG began to disband and new organisations emerged including UPIAS, the Disability Alliance, and the Royal Association for Disability Rights (RADAR), all with different and contrasting objectives. The welfare state receded with the abandonment of full employment, the imposition of cash limits on expenditure, and the International Monetary Fund loan in 1976. In the economic climate of the time, the chance of additional statutory provision for disabled people was waning.

Peace News

Peace News was founded in 1936 by journalist Humphrey S. Moore, a Quaker and a member of the Peace Pledge Union, an influential pacifist organisation whose members included Aldous Huxley, Bertrand Russell, and Siegfried Sassoon (Ceadel 321–22). The organisation was motivated by the non-violent resistance theories of Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi, and the latter contributed to the publication. It advocated moral deterrence and passive resistance against invasion and was boycotted by newsagents during the Second World War. After the war, the publication took on a range of causes: parliamentary affairs, anti-colonial struggles, campaigns against nuclear weapons and testing, supporting the American civil rights movement, and protesting the Vietnam War by covering Buddhist war resisters. Peace News also supported a Welsh-language television network and was involved with the British Withdrawal from Northern Ireland Campaign. Influenced by the American civil rights movement, the publication added 'for non-violent revolution' to its masthead in 1971. It tried to create a libertarian pacifist movement by organising 'potlatches.' So too did it put together 'affinity groups' to conduct pacifist campaigns against nuclear power (McHugh et al. 344). The paper was also progressive in its content on feminism, homosexuality, and sexual politics (Beale). Peace News was part of the 'revolution of expectation' in the 1970s.

This 1976 issue of Peace News was reproduced for online viewing by Keith Armstrong (1950–2017) in 2014 with an updated introduction. Born in Cape Town, South Africa, Armstrong acquired polio as an infant and used a wheelchair throughout his life. He was a tireless campaigner for disability and housing issues as well as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. An active protestor with the Disabled People's Direct Action Network, an organisation whose campaigning helped lead to the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act, he also served as an advisor to several London boroughs and succeeded in improving accessibility on London Transport (Gill, 'Keith'). Little is known about the other contributors to this issue except Trevor Thomas (1907–1993), an art historian and the last person to see Sylvia Plath alive. Born in South Wales, Thomas had an impressive career in Britain and the United States and was an internationally renowned expert in primitive art. He did not serve in the Second World War because of hearing impairment and supported social justice causes (Stuart). Thomas was on the Executive Committee of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality and was responsible for a programme for elderly and/or disabled homosexuals. Thomas, and Maryanne Gorden, a member of the Science for the People Collective (UK), a radical group of engineers and scientists, completed the illustrations (Armstrong 2014).

'Introduction'

Armstrong's introduction is evidence that radical perspectives were widespread in the 1970s. The examination of social barriers was the basis of the work of Finkelstein (1972, 1975, 1980) and UPIAS (1974, 1976). Following on from UPIAS, Michael Oliver's Social Work with Disabled People (1983) was influential in establishing the social model that came to dominate policy and political discourse. He later used the term 'emancipatory disability research' to describe the idea of deconstructing the processes that create disability through activist research (Oliver 1992). Emancipatory disability research argued that pre-industrial society did not exclude disabled people. Industrial evolution and the physicality of industrial labour excluded disabled people and created a disabled identity based on personal tragedy and dependence. Revolution and the fall of capitalism, it was thought, would liberate women, ethnic minorities, and disabled people. While this argument was popular in the 1980s, Armstrong's comments indicate its earlier existence:

We can only really be liberated when we are all liberated and that can only hap pen [sic] during revolution . .. people with disabilities cannot be liberated if they are either sexists or racists. People who are gay only really came out when the message of ' to be gay is to be beautiful ' got across. Likewise with people who are Black. People with disabilities can only really come out (I know I haven't fully) when they/we consider ourselves to be beautiful as well. ('Introduction' 5)

Solidarity with other perceived victims of capitalism became common in the 1980s, and like Armstrong, some disabled people held this position in the 1970s.

UPIAS had radical aspirations in the 1970s. Notwithstanding the 1970 Equal Pay Act, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act, and the 1976 Race Relations Act, organisations such as DIG, the Disability Alliance, and RADAR did not align disability with feminism, anti-racism, and efforts opposing discrimination toward homosexuals. In the early 1970s, incomes and poverty were the main issues in disability politics. Major organisations were criticised by UPIAS for their inadequate representations of disabled people and for being controlled by non-disabled people. By contrast, UPIAS promoted a disabled-led approach and argued that poverty amongst disabled people was a result of systemic oppression in society. Based in part on the American civil rights movement, UPIAS fought discrimination and worked to redefine disability as a form of oppression like racism and sexism. UPIAS was radical, but not powerful, as it had no effect on government (Millward 290). It instead sought transformations in perception, unlike organisations that focused on having good relations with government and the creation of services and cash benefits. Armstrong began the introduction by emphasising that most of the essays in this issue were written by disabled people ('Introduction' 5). In his new introduction, Armstrong said that the pursuit of societal change was just beginning in the 1970s: 'At the time of its creation those campaigning for equality for disabled people in the UK, were just a few mainly isolated individuals, and this text reflects the period of its creation' (2014). UPIAS' radical views had considerable influence on perceptions of disability and on disability organisations in the 1980s. While UPIAS was not influential in the 1970s, it was the benchmark for radicalism, and Armstrong and the other writers in this issue shared UPIAS' views.

Armstrong's comments show the increasing confidence in the social model amongst disabled people in the 1970s. Armstrong shared UPIAS' belief that increased statutory welfare could be undesirable: 'When one asks a member/supporter of the " heavy left" what will happen to people with disabilities after their " revolution " all I have heard said was " We will build more ' homes ' and create more sheltered employment for disabled people ". That is no source of liberation' ('Introduction' 5). Traditional disability organisations were run on behalf of disabled people and focused on employment, cash benefits, physical access, and political lobbying (Campbell 81). Like activists, academics, and organisations in the 1980s, Armstrong instead wanted comprehensive changes based on the social model and the identity of disabled people as an oppressed group. While the focus on the social model and oppression was important to how disability organisations dealt with government in the 1980s, it was thought to have had limited subscription in the 1970s. UPIAS addressed independence through the social model—including mobility, living arrangements, and employment opportunities—and said that the state should provide disabled people with medical, technical, and educational support (1974). The social model and oppression were important concepts for UPIAS, and they were prominent themes in this issue of Peace News.

Following the introduction, this issue of Peace News featured six articles:

- 'crippled words' by Keith Armstrong;

- 'people with disabilities and state dependency' by Pat Carr;

- 'superwoman with hips of clay' by Charlotte Baggins;

- 'invisible people' by Kevin Mcgrath;

- 'the grey areas of disabled oppression' by Trevor Thomas;

The final article, 'Claiming,' offered information on benefits and advice on how disabled people should deal with the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS).

'crippled words'

In this essay of about 300 words, Armstrong wrote about the dehumanisation of disabled people and the moral failures of the welfare state. Comparing the abject state of welfare for disabled people in Britain with foreign countries was a tactic of DIG. The organisation made unfavourable comparisons between British provision and that in Turkey and fascist Spain. As Britain was about to join the European Economic Community, DIG published a report exposing Britain's failings compared to member countries (1972). Armstrong compared 1970s Britain to fascist regimes of the 1930s in its treatment of disabled people: 'In the 1930's and 40's the fascists gassed many people with disabilities; they did not fit the image of the " super man " or " super woman ". In this country in the 70's people die from hyperthermia. It is not a disease, one dies from it through lack of money to keep one warm and fed' ('crippled' 5). While DIG tried to elicit public support to compel government to act, Armstrong was angry with the welfare state's inability to create a minimum standard of living for disabled people through the cash benefits. The gap between heightened expectation and the worsening reality in the 1970s fostered radicalism.

Gill said that this essay helped popularise the expression 'people with disabilities' in Britain, and he explained:

This was no mere obsession with political correctness – rather, Keith had taken to heart Chomsky's perception that words influence thought as well as vice versa. Keith disliked later euphemisms such as 'challenged' or 'differently abled' – they were emollients, glossing over the harsh facts of life for people unable to live without human and technical assistance. He simply wanted to make the point that a disability is merely part of a person's life, not the single characteristic that defines him or her. ('Obituary')

While this distinction seems inarguable, it was a novel part of radical thought in the 1970s and became widespread in discussion of disability in the 1980s. In a 1971 Official Report, Harris defined 'impairment' as a physical condition in a person's body defined by medicine and resulting from illness, accident, or genetics. 'Handicap' was defined as a functional interruption resulting from impairment. 'Disability' was defined as a situation where societal factors prevent a person from participating in daily life because of a handicap (Harris 2). Use of these definitions increased in the 1970s and became part of the social model and its growing influence. Finkelstein and UPIAS used them, and they were routinely used to assert the social model in the 1980s. So too did progressive parties emphasise the use of the term 'disabled people' to refer to people with impairments who experienced disability as physical barriers or discriminatory attitudes (Oliver 1990 vii). Changing the definition of disability from medical and functional to social meant there was little excuse for individuals and society to continue to exclude disabled people. Disability could no longer be perceived as a physical condition. Armstrong's term, 'people with disabilities,' represented radical perceptions about the extent of change that was possible.

'people with disabilities and state dependency'

Pat Carr had been rehoused after she and other squatters were harassed and evicted from the Hornsey Rise Estate, London. From childhood, Carr had spasticity, and her radical beliefs were aligned against some of the old attitudes and failures of statutory welfare for disabled people. Mocked in the streets, Carr said physicians used her as a subject in experiments and gave little consideration to the psychological effects of her disability. She recalled being placed in a school for visually impaired children that was inferior to her brother's ordinary school (Carr 6). Notwithstanding the anti-institutionalisation movement and the liberalisation of British society in the 1960s, the number of segregated schools increased in the 1970s because the 1970 Education (Handicapped Children) Act made it illegal to deem a child ineducable. Further, and despite some good intentions, the 1978 Warnock Report and the 1981 Education Act had limited impact on the lives of children with special education needs (Shah and Priestly 34–35, 99, 141–42). Carr's poor education led to an unimpressive clerical qualification, and she had to leave her job because of her employer's worries about her efficiency as a disabled person. This led her to become homeless and develop radical views.

Carr also lacked adequate support at work, and this was indicative of the welfare state's failure in employing disabled people. High unemployment for disabled people was not unique to Britain: Hahn said that the United States and other industrialised countries had post-war unemployment rates for disabled people near two-thirds (165). Hundreds of thousands signed up for the Disabled Persons Employment Register after the Second World War, but only a small fraction benefitted from this programme in the subsequent thirty years. There was also little support for disabled people in employment beyond general practitioners. Under the 1944 Disabled Persons (Employment) Act, employers were to reserve three per cent of positions for disabled people on the register. With the recession of the 1970s, fewer employers were fulfilling their obligations, and in thirty years, there was almost no prosecution of violations (Hampton 197). From an incorrect placement in school to becoming homeless because of discriminatory attitudes at her job, Carr's story is indicative of the welfare state's failure to improve the employment circumstances of most disabled people. As UPIAS pointed out, exclusion from employment was at the centre of all other types of exclusion (1976 15–16).

Carr also became radicalised because of how she saw her eviction, during which squatters were pitted against each other by officials, as another example of the capitalist division of resistance: 'Division of class, race, sex, able-bodied, disabled, family and single persons prevailed in the end' (6). She said that non-disabled people were told to find their own homes, while disabled people and families with children were forced into dreadful living conditions and made to feel grateful. This was the less eligibility principle of the 1834 Poor Law. To discourage impostors, people were forced into supplicant roles to receive a minimum standard of housing at a time when there was insufficient council housing and unaffordable private accommodation. As in Canada and the United States, disabled people in Britain were still subject to poor relief practices and had to surrender self-determination and the freedom to choose their lifestyle to receive statutory provision (Rioux 221). Carr's radicalism was set within the economic climate of the time:

for those of us who have to be dependent on the State for survival, there can only be one solution: take all we can off them and don't feel grateful; keep on pushing for more, for everybody. The capitalist system in this country and elsewhere is under a strain, and we can stretch it to the breaking point by refusing to be satisfied with meagre handouts and by refusing to help them make profits. We must work to break down the divisions that exist and make nonsense of the categorisations. (6)

Carr's attitudes mirrored the radical thinking amongst disabled people in the 1980s: anger at dependence on the state, defiance instead of supplication, and a desire to break down the divisions created by capitalism around minority and disadvantaged groups.

'superwoman with hips of clay'

Charlotte Baggins had hip dysplasia and was a member of the Anarchy Collective, a London-based group that published Anarchy magazine. By the 1970s, trust in medical professions was waning. Her essay showed the power of radical anti-medicalization and anti-professional beliefs before they were accepted in the disability movement in the 1980s (Baggins 7). Many academics in the 1980s began to follow anti-medicalization scholars of the 1970s in their distrust of institutions, medical science, physicians and other professionals. Medical knowledge and power drove the medical and personal tragedy models of disability, which disagreed with the social model. Watermeyer said that the personal tragedy model in particular does not reflect the lived experience or self-identification of disabled people and functions 'culturally as a means of achieving mastery over the dissonant and frighteningly unknown phenomenon of disability' (93, 97). While some academics in the 1970s were familiar with the works of prominent anti-medicalization theorists, and while UPIAS was active at the time, the social model was not yet fully formed. It is probable that Baggins' views were not based on anti-medicalization literature or the emerging social model but on her personal experience and the defiant attitude amongst disabled people at the time:

It quite surprises me that I am not a people hater. I do hate, I have a great capacity for it, but it is channelled against capitalism, the state and yes, doctors … I go and see a consultant and I try to choose a time when I'm feeling reasonably strong—just countering their pedestal power, their supremacy that says because I don't have perfect hips I am some kind of subhuman species that should be talked down to. (7)

Baggins' essay shows that radical anti-medicalization and anti-professional convictions existed amongst disabled people and were unrelated to academic discourse in the 1970s. It also shows her frustration with the lack of control over her well-being, and this was a major part of the human rights focus that fuelled radical critiques of the welfare state. By the 1970s, many disabled people had learned that they must try to survive despite the welfare state, not in concert with it.

With the rise of health consumerism and the post-war generation coming to adulthood, the once-esteemed public services and associated professions were scrutinised for their outdated attitudes and practices. Public goods and services became subject to consumerist activism (Mold 2032). The distrust of authority amongst disabled people was further stoked by stories published about abuse and neglect in private care, and local authorities were pressed into greater activity. Baggins was displeased with serving as an audio-visual aid for surgeons and felt that she was used as a subject in experiments (7). She is an example of lay challenges to professionals at the time, and many disabled people began to think that they would have to work directly for the improvement of their own welfare. This led to the rise of self-help and populist groups that were different from DIG and its 'single issue' focus on a national disability income (Oliver 1990 114). Baggins' experience also shows that radical anti-medicalization and anti-professional beliefs existed amongst disabled people before these beliefs became common in the disability movement in the 1980s. The emergence of these radical beliefs was also part of the growing power of the social model in the 1970s.

'invisible people'

Kevin Mcgrath had a daughter with a severe intellectual disability. His essay focused on the 'mixed economy of welfare,' the concept that a person's needs are met by a combination of private, statutory, and formal and informal voluntary efforts. Mcgrath described his experience as an overburdened father of a daughter whose intellectual disability was not considered severe enough for statutory assistance. He described how his daughter and others were subject to discrimination and problems in employment and integration. Not only had the welfare state abandoned his daughter, but it also asked too much of his family within the mixed economy of welfare: 'the mentally handicapped and their families are not just a mass of unfortunate individuals. They constitute two groups of people who are the victims of structural failings in our society' (Mcgrath 8). He added that intellectually disabled children have no choice but to be placed in institutions or cared for by family. This was an old problem and another indicator of the more recent failures of statutory welfare for disabled people. Eugenicists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries thought the state should control and isolate intellectually disabled people (Jarrett and Walmsley 178–85). They were seen as threats to social order to be locked up or as afflicted victims who should stay at home. Mcgrath became radicalised because his family faced this scenario in the 1970s.

Dissatisfied with statutory welfare, Mcgrath appealed for greater efforts from other groups within the mixed economy of welfare. In the 1960s and 1970s, most came to believe that the state should take on a greater portion of the welfare of disabled people within the mixed economy of welfare. This opinion permeated disability policy discussion in the 1970s. Mcgrath instead argued for greater non-statutory efforts because the welfare state had failed to provide adequate provision to improve the lives of disabled people. For intellectually disabled children in the post-war period, the broad trend was a move away from institutions and toward community care within the mixed economy of welfare. The Beveridge Report, the blueprint of the welfare state settlement of the 1940s, outlined particular roles for voluntarism including social insurance beyond the statutory minimum, and caring, monitoring, and personal welfare for disabled people, elderly people, those not in employment, and other groups in need (Harris 10). In a period when most concerned parties called for the expansion of the welfare state in regard to disabled people, Mcgrath appealed to voluntarism: 'Once self-help groups have established themselves, it obviously becomes much easier for those not involved to offer their help' (8). He asked for community involvement and local relationships in libraries, playschemes, and sub-normality hospitals. He also implored people to work with non-statutory organisations and asked the designers of planned communities to create accommodation for intellectually disabled people (9). Mcgrath's views on the mixed economy of welfare were unusual for those concerned with disability issues in the 1970s. He was angry at the state for its failures, and believed, as the new right did in the 1980s, that other providers within the mixed economy of welfare should and could do more for disabled people.

Taken across the greater history of twentieth-century welfare, Mcgrath's essay shows that families in the 1970s remained the greatest source of support for intellectually disabled people and were prominent in working for reform and against institutionalisation. His essay also shows the importance of family and other informal welfare against, rather than alongside, statutory welfare and the attitudes that drove it. Before the rise of state institutions for intellectually disabled people in the late nineteenth century, their welfare was the responsibility of families and formal voluntarism. With the welfare state settlement of the 1940s, the state took on a larger role in the welfare of most people within the mixed economy of welfare (Gladstone 37–38). With the failures of the welfare state in the 1970s, Mcgrath sought a mixed economy of welfare in which non-state actors played a greater role. His essay, however, is also indicative of the 'revolution of expectation' and the faith, despite his experience, that statutory welfare would begin to provide vital provision for disabled people. In the inter-war period, few would have expected that an intellectually disabled child would be included in regular education. This was a reasonable expectation in the 1970s. Mcgrath's radicalism and goals were based on the welfare state's neglect of him and his family.

'the grey areas of disabled oppression'

Thomas' essay on disability and oppression questioned discrimination based on disability, ethnicity, political beliefs, and sexual orientation. As a self-identified, 'deaf homosexual Welshman in an Anglo-Saxon world with left-political views' (Thomas 10), his outlook is similar to those of activists who thought that minority groups had much in common because of their struggles against marginalising conservative forces. For disabled people in the welfare state, statutory provision was not a right of citizenship. Adequate statutory provision was earned through work, and, as Thomas mentioned, was inapplicable to many disabled people. This was a reaction to the failures of the CSDP Act and the ineffectiveness of the cash benefits. In the early 1970s, many were dissatisfied with DIG's focus on incomes and sought instead to defeat greater societal inequalities (Millward 290). Disabled people began to see statutory welfare as a human right and began to self-identify as a minority group. The 1975 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons asked states to work toward the full integration of disabled people in social and economic life. So too did international law through the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which came into effect for member countries in 1976. Disabled people began to seek legislation like the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act and the 1976 Race Relations Act, which protected individuals from discrimination based on personal attributes.

Thomas' essay evinces the pan-disability and anti-oppression thinking that became powerful in the 1980s. He described his personal struggle with becoming hearing impaired: 'Whatever the nature of the oppression—physical, political, racial, sexual—in my experience the essential basic adjustment required for sane survival is your own acceptance of the reality of the disability or difference from the prevailing norm' (10). Thomas also objected to the different treatment of hearing-impaired people, visually impaired people, and other disabled people by the 'oppressiveness of the opposites' (10). In the 1980s, disabled people came to value organisations of not for disabled people and saw earlier organisations as serving the medical model and the individualisation of disability at the cost of the social model and greater societal change. As Colin Barnes pointed out, disabled people and disabled-led organisations were increasingly important in the efforts of the 1980s to obtain anti-discrimination legislation (1991 6–7). They also saw older forms of advocacy as propping up a Poor Law culture that made disabled people dependent on the charity of non-disabled people. As is evident in Thomas' essay and other essays in this issue, this outlook also existed amongst disabled people in the 1970s.

'Claiming'

This section concluded the issue and encouraged disabled people to act. It advised disabled people on how to apply for cash benefits and discussed some of the traditional and new problems they faced. In the economic climate of the time, cash benefits were vital to the welfare of disabled people. Whether employed or unemployed, disabled people, especially those with severe disabilities, face harder financial circumstances in challenging times. Mavis Hyman showed that extra expenses averaged 25% of the total income for disabled people (110). High inflation was harmful because it eroded the value of cash benefits used to meet the special expenses of disabled living. In periods of high unemployment, relatives are often themselves unemployed and unable to provide financial support or assistance in kind to disabled people. Cash benefits were needed to make up for local services that were not introduced or withdrawn to cut costs, as the terms of the CSDP Act were permissive.

The DHSS was responsible for the new cash benefits introduced by the Labour governments (1974–6): the Invalid Care Allowance (ICA), the Mobility Allowance, the Non-Contributory Invalidity Pension (NCIP), and the Housewives' Non-Contributory Invalidity Pension (HNCIP). The DHSS was also responsible for Supplementary Benefit, a means-tested payment for people with low incomes regardless of employment status. This was intended to top up other cash benefits to a minimum amount by considering the cost of living and additional costs like diet, heating, and laundry. Recipients could also receive free prescriptions and funds for clothing and dental and optical treatment. Supplementary Benefit replaced National Assistance in 1966, and many hoped the new benefit and the change in name would reduce the stigma of applying for and receiving payment. Before the cash benefits of the 1970s, many disabled people relied on supplementary benefits to live. 'You probably know that this is paid if you haven't got enough money to bring you up to what they think you need to live on,' this section explained ('Claiming' 12).

Disabled people had problems with the DHSS, as this section warned: 'If you have a disability the chances are that you will be unemployed or considered too ill to work, and you will also have to tackle the Department of Health and Social Security at some time. Never tackle the DHSS on your own' (12). The DHSS had a poor reputation. Claims for the cash benefits were evaluated by a National Insurance Officer, but forms were often obtained at a local DHSS office and submitted with the assistance of junior case workers. With the pressure of having many clients and the awareness of limited resources, case workers sometimes did not represent the full needs of disabled people. There was also the idea that the DHSS wanted to deny claims and limit public knowledge of the cash benefits to limit expenditure. Further, due to the large number of claimants, claims were often assessed locally and subject to the moral and personal judgements of an overburdened official (Simkins and Tickner 58–59).

Disabled people faced difficulties in articulating their individual needs and complex living situations when seeking the cash benefits and services under the CSDP Act. Different qualifying criteria for different cash benefits added problems. The medical certification required for the NCIP and the HNCIP involved general practitioners and often specialists. For services, cash benefits, assistance with employment, and other vital provision, a disabled person may have had to visit several local authority departments. Disabled people struggled to make their circumstances known to local authorities and were often made to participate in subjective and inconsistent means tests. The difficulty of applying for the cash benefits was often worsened by a disabled person's condition, and the assistance of a friend or family member was often needed. The 'Kafka-like world' of statutory provision, as it was known, was confusing. Mildred Blaxter found that 59 agencies—defined as an organisation or branch of an organisation with a separate function and address—contributed to the welfare of disabled people in services, cash benefits, and employment programmes (18–19). There was confusion amongst disabled people, physicians, hospital staff, social workers, and local officials. This was the 1970s, but it seemed like the 1834 Poor Law—disabled people needed the help of family and local officials determined outdoor relief. The social and psychological stigma was strong.

Stigma was a major cause of low and non-take up. Goffman said that while altruistic social action is meant to mitigate rejecting attitudes, stigmatised people remain subject to discrimination including labels like 'cripple, bastard, moron' and the belief that a 'person with a stigma is not quite human' (5). Further, it is notable that Beveridge saw stigma as necessary to maintain the motivation for people to better themselves within an enlarged welfare state (Fitzpatrick 362). If services or cash benefits are well publicised and/or subject to group qualification, there is often less stigma and more openness. This section was meant to publicise the cash benefits and the closed process based on individual qualification:

Many people find a lot of difficulty in claiming supplementary benefit, either because of delays or because they have to fill in a lot of forms, or feel humiliated by the way they are treated by the officials. The best way to deal with them is to keep your cool and be polite, but don't let them put you off, and be stubborn. Remember that you can appeal against any decision that they make and that the appeal tribunal is not bound by DHSS policy but only by the Social Security Acts. ('Claiming' 12)

There was added stigma based on the idea that statutory welfare was hurting the economy at a challenging time. Frustration and humiliation often prevented disabled people from revealing their circumstances to local officials to receive the cash benefits.

Many disabled people became radicalised in the 1970s because of their anger at the cash benefits. In trying to obtain the cash benefits in the 'Kafka-like world' of statutory welfare, disabled people faced attitudes and practices reminiscent of the Poor Law in a country that purported to now be sympathetic to the less fortunate. In the shadow of the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act and the 1976 Race Relations Act, the cash benefits helped few and were often inadequate. The view from 1976 was bleak: taken together, the Constant Attendance Allowances (introduced by the Heath government) and the ICA assisted only 11,500 carers and excluded married women; the HNCIP would only improve the financial situation of 15,000 women; the NCIP would only increase incomes for 50,000; and the low rate of the Mobility Allowance meant it could not fulfil its purpose (Hampton 204, 206). As the welfare state collapsed, its failures in services and cash benefits amounted to its inefficacy in improving the lives of disabled people. This section is evidence that disabled people in the 1970s often had to struggle for their welfare against the policy and practices meant to improve it. The 'revolution of expectation' raised hopes in an unfavourable economic period, and when they were dashed, many sought radical solutions.

Conclusion

This article shows that disabled people were radical in the 1970s. These diverse writers held radical perspectives before they became mainstream in the 1980s. In the 1970s, disabled people became radicalised in response to traditional failures of British welfare and recent failures of the welfare state. They were critical of the failures of the CSDP Act and the cash benefits that did not add up to a national disability income. Disabled people also objected to older repressive elements of statutory welfare including less eligibility, institutionalisation, and social and psychological stigma. Disabled people saw themselves as a minority group and fought against what they perceived as capitalist oppression. Unlike major disability organisations in the 1970s, these writers were militant, not amicable, and they perceived themselves as a group denied rights and adequate welfare.

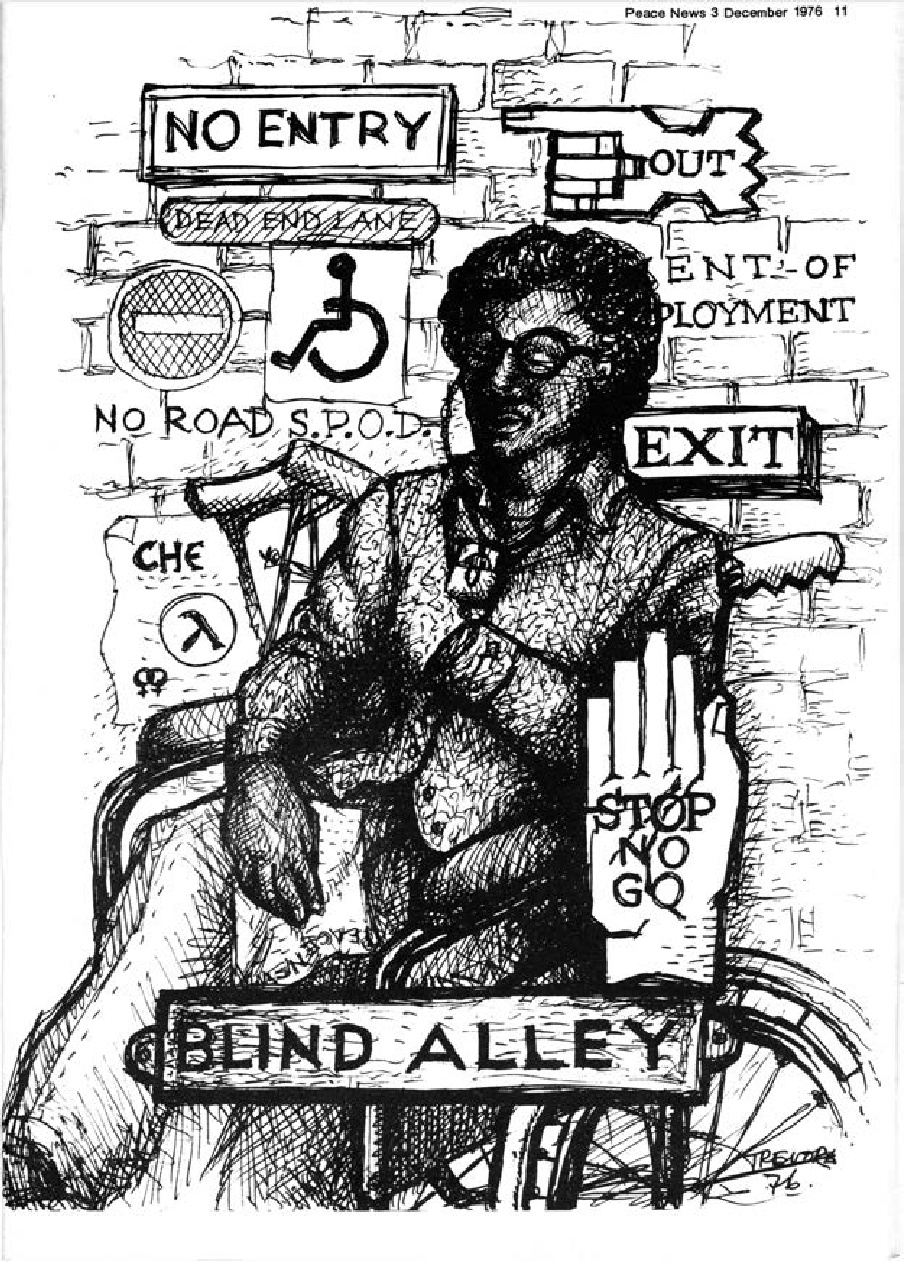

In 1976, there was meaning in Armstrong's term, 'people with disabilities.' It placed disabled people within the human rights approach of the time and emphasised the shift from seeking services and cash benefits to seeking personal independence. The term also connected persecuted groups—disabled people, homosexuals, and ethnic minorities—as people fighting for human rights. 'People' and 'disabilities' are linked and separated, recognising disability as a complicated interaction between parts of the body and parts of society, and that there can be freedom for disabled people when disabling social barriers are removed. In Thomas' drawing, Blind Alley, the man in the wheelchair is hearing impaired and visually impaired, but his physical environment—with its petty rules, barriers, and discrimination—is what impedes him. Radical voices in Britain, as examined in this article, had subscribed to the social model of disability before it became powerful in the 1980s.

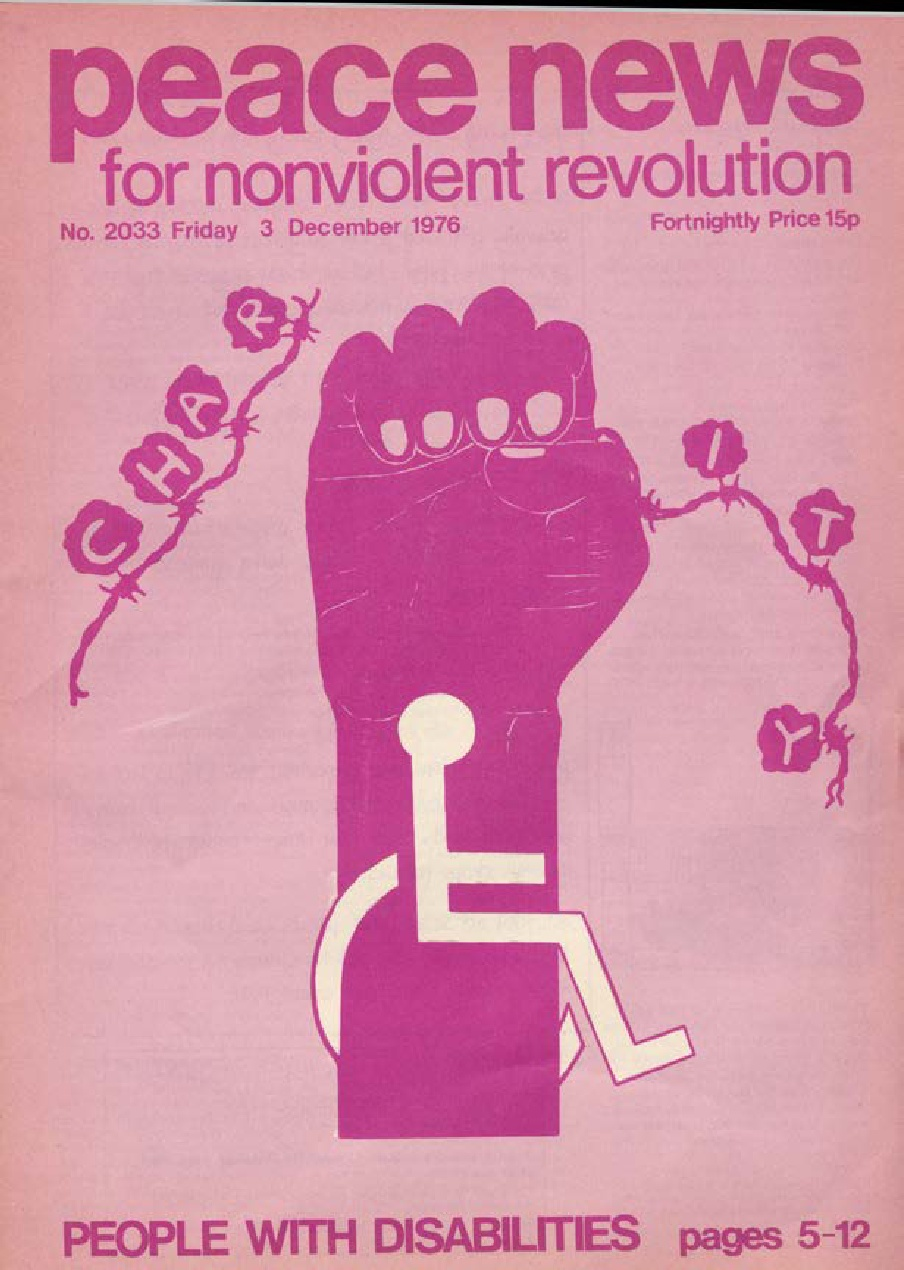

The radical authors in this issue of Peace News felt incarcerated by the traditions and culture of the country that created industrial capitalism, as Armstrong pointed out: 'The cover image is of barbed wire representing disability discrimination with the cotton wool of the charity industry who by their very nature never fully resolve the cause of problem they came to alleviate' (2014). Lancashire cotton was a historical symbol of industrial evolution, and scholars have often said that the physicality of industrial labour barred disabled people from participation in modern British social and economic life (see Barnes 1985, Oliver 1990). 'Charity industry' also has nineteenth-century associations. 'Britain is a country profoundly uncomfortable with disability and difference' (40), wrote Frances Ryan in 2019 about the British tradition of lack of coherent approach to the welfare of disabled people—something that commentators have been saying for decades. 1981 was the International Year of Disabled Persons, and in Britain, there was discussion about what went wrong in the 1970s. There were foreign comparisons, as Alf Morris, Britain's first Minister for the Disabled, put it: 'Many poorer countries have not chucked the disabled out of society as we did in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries when we made prisons on the edge of town for people that did not meet the norms. In the third world, the disabled are a part of society, not a-part from society like they are here' (Timmins). As these radical writings showed, the 1970s saw little change in Britain's poor treatment of disabled people. For disabled people, there was not much of a welfare state to dismantle when Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979.

Works Cited

- Abel-Smith, Brian, and Peter Townsend. The Poor and the Poorest: A New Analysis of the Ministry of Labour's Family Expenditure Surveys of 1953-54 and 1960. Bell, 1965.

- Armstrong, Keith. 'Introduction 2014.' From a Disability Perspective: UK Radical Disabled People Writings on Disability Issues in the mid-1970's, Originally Compiled by Keith Armstrong (First Published in 1976 in Peace News) with a New Introduction by Keith Armstrong, edited by Keith Armstrong, 2014. academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/9666143/From_a_Disability_perspective_UK_radical_Disabled_People_writings_on_disability_issues_in_the_mid-1970s_originally_compiled_by_Keith_Armstrong_first_published_in_1976_in_Peace_News_with_a_new_introduction_by_Keith_Armstrong

- ---. 'crippled words.' Peace News, no. 2033, 3 Dec. 1976, pp. 5.

- ---. 'Introduction.' Peace News, no. 2033, 3 Dec. 1976, pp. 5.

- Baggins, Charlotte. 'superwoman with hips of clay.' Peace News, no. 2033, 3 Dec. 1976, pp. 7.

- Barnes, Colin. Disabled People in Britain and Discrimination: A Case for Anti-Discrimination Legislation. Hurst, 1991.

- ---. 'Discrimination against Disabled People (Causes, Meaning and Consequences) or the Sociology of Disability.' Jan. 1985. The UK Disability Archive, https://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/Barnes-Barnes-dissertation.pdf

- Beale, Albert. 'Peace News: The First 75 Glorious Years.' Peace News, no. 2534, June 2011.

- Blaxter, Mildred. The Meaning of Disability: A Sociological Study of Impairment. Pearson Educational, 1976.

- Borsay, Anne. Disability and Social Policy in Britain since 1750: A History of Exclusion. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Campbell, Jane. '"Growing Pains": Disability Politics – The Journey Explained and Described.' Disability Studies: Past, Present and Future, edited by Len Barton and Michael Oliver, The Disability Press, 1997, pp. 78–90.

- Carr, Pat. 'people with disabilities and state dependencies.' Peace News, no. 2033, 3 Dec. 1976, pp. 6.

- Ceadel, Martin. Pacifism in Britain, 1914–1945: The Defining of a Faith. Clarendon, 1980.

- 'Claiming.' Peace News, no. 2033, 3 Dec. 1976., pp. 12.

- Disablement Income Group. Social Security and Disability: A Study of Financial Provision for Disabled People in Seven Western Countries. Disablement Income Group, 1972.

- Finkelstein, Vic. Attitudes and Disabled People: Issues for Discussion. World Rehabilitation Fund, 1980.

- ---. 'Phase 2: Discovering the Person in "disability" and "rehabilitation".' Magic Carpet, vol. 27, no. 1, 1975, pp. 31–38.

- ---. 'The Psychology of Disability.' Mar. 1972. The UK Disability Archive, https://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/finkelstein-01-Talk-to-GPs.pdf. Transcript.

- Fitzpatrick, Tony. 'Cash Transfers.' Social Policy, 3rd ed., edited by John Baldock, Nick Manning, and Sarah Vickerstaff, Oxford UP, 2007, pp. 349–80.

- Gamble, Andrew, and Paul Walton. Capitalism in Crisis: Inflation and the State. Macmillan, 1976. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-15707-5

- Gill, Tom. 'Keith Armstrong obituary.' Guardian, 4 Aug. 2017.

- ---. 'Obituary: Keith Armstrong: 7 April 1950 - 7 May 2017.' Peace News, nos. 2608–2609, Aug.–Sep. 2017.

- Gladstone, David. 'Renegotiating the Boundaries: Risk and Responsibility in Personal Welfare since 1945.' Welfare Policy in Britain: The Road from 1945, edited by Helen Fawcett and Rodney Lowe, Macmillan, 1999, pp. 34–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-27322-5_3

- Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Prentice-Hall, 1963.

- Gulland, Jackie. 'Working while Incapable to Work? Changing Concepts of Permitted Work in the UK Disability Benefit System.' Disability Studies Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 4, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v37i4.6088

- Hahn, Harlan. 'Academic Debates and Political Advocacy: The US Disability Movement.' Disability Studies Today, edited by Colin Barnes, Len Barton, and Michael Oliver, Polity, 2002, pp. 162-89.

- Hampton, Jameel. Disability and the Welfare State in Britain: Changes in Perception and Policy, 1948–79. Policy Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781447316428.001.0001

- Harris, Amelia. Handicapped and Impaired in Great Britain, Part One. HMSO, 1971.

- Harris, Jose. 'Voluntarism, the State and Public-Private Partnerships in Beveridge's Social Thought.' Beveridge and Voluntary Action in Britain and the Wider British World, edited by Melanie Oppenheimer and Nicholas Deakin, Manchester UP, 2011, pp. 9–20.

- Hicks, John, et al. Crisis '75…? Institute of Economic Affairs, 1975.

- Hunt, Paul. 'A Critical Condition.' Stigma: The Experience of Disability, edited by Paul Hunt, Geoffrey Chapman, 1966.

- Hyman, Mavis. The Extra Costs of Disabled Living: A Case History Study. National Fund for Research into Crippling Diseases, 1976.

- Jarrett, Simon, and Jan Walmsley. 'Intellectual Disability Policy and Practice in Twentieth-Century United Kingdom.' Intellectual Disability in the Twentieth Century: Transnational Perspectives of People, Policy and Practice, edited by Jan Walmsley and Simon Jarrett, Policy Press, 2019, pp. 177–94. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781447344575.003.0015

- Knight, Rose, and M. D. Warren. Physically Disabled People Living at Home: A Study of Numbers and Needs. HMSO, 1978.

- Loach, Irene. Disabled Married Women: A Study of the Problems of Introducing Non-Contributory Pensions in November 1977. Disability Alliance, 1977.

- Lowe, Rodney. The Welfare State in Britain since 1945. 3rd ed., Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Mcgrath, Kevin. 'invisible people.' Peace News, no. 2033, 3 Dec. 1976, pp. 8–9.

- McHugh, John, et al. Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organizations: Parties, Groups and Movements of the Twentieth Century. Pinter, 2000.

- Millward, Gareth. 'Social Security Policy and the Early Disability Movement—Expertise, Disability, and the Government, 1965–77.' Twentieth Century British History, vol. 26, no. 2, 2015, pp. 274–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/hwu048

- Mold, Alex. 'Patients' Rights and the National Health Service in Britain, 1960s-1980s.' American Journal of Public Health, vol. 102, no. 11, 2012, 2030–38. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300728

- Morgan, Kenneth O. 'Britain in the Seventies – Our Unfinest Hour?' French Journal of British Studies, vol. 22, special issue, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4000/rfcb.1662

- O'Connor, James. The Fiscal Crisis of the State. St. Martin's, 1973.

- Oliver, Michael. 'Changing the Social Relations of Research Production.' Disability, Handicap and Society, vol. 7, no. 2, 1992, pp. 101–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02674649266780141

- ---. The Politics of Disablement. Macmillan, 1990. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20895-1

- ---. Social Work with Disabled People. Macmillan, 1983. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-86058-6

- Rioux, Marcia. 'Disability, Citizenship and Rights in a Changing World.' Disability Studies Today, edited by Colin Barnes, Len Barton, and Michael Oliver, Polity, 2002, pp. 210-27.

- Ryan, Frances. Crippled: Austerity and the Demonisation of Disabled People. Verso, 2019.

- Sainsbury, Sally. 'Disabled People and the Personal Social Services.' British Social Welfare: Past, Present, and Future, edited by David Gladstone, UCL Press, 1995, pp. 189–201.

- Shah, Sonali, and Mark Priestley. Disability and Social Change: Private Lives and Public Policies. Policy Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qgt0j

- Simkins, Jean, and Vincent Tickner. Whose Benefit? An Examination of the Existing System of Cash Benefits and Related Provisions for Intrinsically Handicapped Adults and their Families. Economist Intelligence Unit, 1978.

- Stuart, Robert. 'Obituary: Trevor Thomas.' Independent, 9 July 1993.

- Timmins, Nicholas. 'Charter for 1980s Warns Society of Waste of Potential.' Times, 30 Jan. 1981.

- Thomas, Carol. 'Disability: Prospects for Inclusion.' Fighting Poverty, Inequality and Injustice: A Manifesto Inspired by Peter Townsend, edited by Alan Walker, Adrian Sinfield, and Carol Walker, Policy Press, 2011, pp. 223–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qgkb7.16

- Thomas, Trevor. 'the grey areas of disabled oppression.' Peace News, no. 2033, 3 Dec. 1976, pp. 10.

- Topliss, Eda. Provision for the Disabled. Blackwell, 1979.

- Townsend, Peter. The Last Refuge: A Survey of Residential Institutions and Homes for the Aged in England and Wales. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1962.

- Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation and Disability Alliance. The Union of the Physically Impaired against Segregation and the Disability Alliance Discuss Fundamental Principles of Disability. Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation/Disability Alliance, 1976. The UK Disability Archive, https://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/UPIAS-fundamental-principles.pdf

- ---. Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation: Policy Statement. Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation, 1974. The UK Disability Archive, https://disability-studies.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/library/UPIAS-UPIAS.pdf

- Walker, Alan. 'Section VII: Disability.' The Peter Townsend Reader, edited by Alan Walker, David Gordon, Ruth Levitas, Peter Phillimore, Chris Phillipson, Margot E. Salomon, Nicola Yeates, Policy Press, 2010, pp. 487–552. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t89jmr.15

- Watermeyer, Brian. 'Claiming Loss in Disability.' Disability and Society, vol. 24, no. 1, 2009, 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590802535717

- Webster, Charles. The Health Services since the War, Vol. 1, Problems of Health Care: The National Health Service before 1957. HMSO, 1988.

- Wright, Fay. Public Expenditure Cuts Affecting Services for Disabled People. Disability Alliance, 1977.