This is an HTML version of a creative work. A PDF version is available at: https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v40i2.6752

I compiled this collection of non-fiction prose/poetry (including diary entries from the period directly before and after I received medical diagnoses for my "invisible" impairments) in reflection on my first OT visits and the issues they 'touched' upon: my hands; nerves; joints; collagen; (ab)normality; dys/functionality; history; future; self.

For most of my independent life, with the exception of routine "green light" check-up visits to drop-in clinics, I avoided all but the most alternative health care professionals and practices. A hippy-leaning, able-body-identified, long-ago-Women's-Studies-minor-turned-yoga-aficionado/addict, I saw the bio-medical-pharmaceutical complex through sceptical eyes. Besides which, I was healthy/lucky/young enough to buy into what Susan Wendell (1996) calls a 'myth of control' that:

people embrace… in part because it promises escape from the rejected body. The essence of the myth of control is the belief that it is possible, by means of human actions, to have the bodies we want and to prevent illness, disability, and death. Like many myths, the myth of control contains a significant element of truth; we do have some control over the conditions of our bodies, for example through the physical risks we take or avoid and our care for our health. (p. 93-94)

By contrast, the last seven years have found me on the (im)'patient' end of countless appointments with allopathic para/medical practitioners. In an effort to figure out how to take care of a doubly-diagnosed body no longer adequately served by my own "outside-the-box" attempts at self-care, I have consented to being physically manipulated, pricked, electro-conducted, x-rayed, monitored, discussed, and otherwise evaluated in a variety of specialists' and generalists' offices and labs. This included seeing an occupational therapist, or OT for short.

With the intention of "reduc[ing] the hyperextension of [my] finger joints and associated complications" she "created a set of custom-made low temperature thermoplastic splints for [my] fingers to increase [my] capacity… and decrease the risk of pain, injury and possibly soft tissue damage" (quoted from her letter of treatment, January 28, 2015). In layperson's terms, after heating plastic strips in warm water, she moulded them to my fingers, creating moderately comfortable splints to stabilise, support and restrict the range of motion of my deviantly "hyper-mobile" joints. These splints are not without their setbacks (e.g., calluses and tenderness that started showing up after a few days of trying them out, difficulties with manipulating objects, etc.)—not to mention the risks of exacerbating existing issues by transferring pressures to other areas, creating dependence, etc.

"Zippers and elevator buttons," I reported enthusiastically when I called after the trial period to check in. "I can do up my coat and push elevator buttons—repeatedly!—with my own fingers, without worrying I'm injuring myself."

A couple weeks later, I returned to be fitted for the more permanent, patented, US-made versions of the splints (there is a competing Canadian company I asked about, but my OT stopped ordering from them after some difficulty getting a splint re-sized by them). I sat with a cup of tea at her dining room table as she tinkered with the company-supplied blue plastic sizing contraption. She fiddled with placing sequentially-sized proximal and distal loops ultimately intended to brace my PIP and DIP joints into the haphazard connector blocks, going back and forth between my fingers and all the different options. Twice, she called the company to ask questions (e.g., which style and size would be best to use, given my unique situation – with includes my pinky DIP joint's being too small for their tiniest loop; my range of motion's exceeding the ideal swan-neck spacing requirements, etc.). When she finally wrote down the "final" calculations (pending adjustments), we high-fived.

At some point, after seemingly endless re-calibrations, I commented: "No offence, but it seems sort of random."

She nodded, smiling, not at all defensive.

"Definitely more an art than a science," I mused, thinking of all the degrees of imprecision and uncertainty in the process, from figuring out sizing to predicting ultimate effect to determining costs with re-sizing factored in.

"Yes," she agreed. "Some doctors don't get that part, though."

--

My hands are small, I know

But they're not yours, they are my own

But they're not yours, they are my own

And I am never broken

-Jewel (Kilcher), "Hands" (in Spirit, 1998)

--

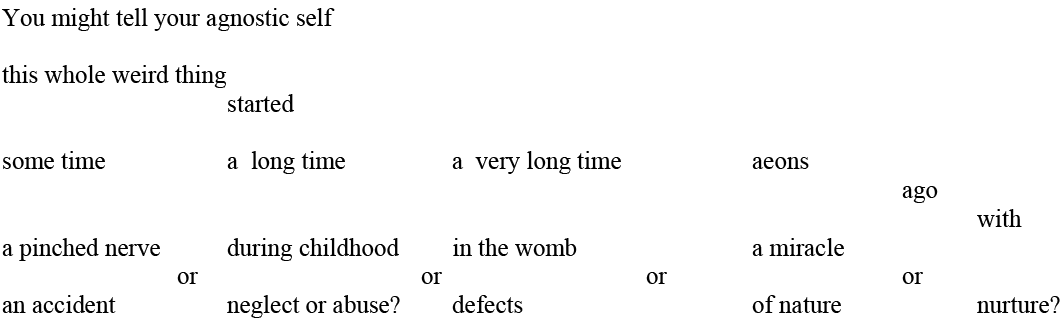

![my hands always did things (most) other hands could[n’t] but how could I know what other hands could do that mine were different (humble heroes handling so much we don’t give them enough credit) when I stretched my thumbs to my wrists all the way, in both directions, showing off my fingertips bent at unexpected angles (I(t)) would freak them out…](https://dsq-sds.org/index.php/dsq/article/download/6752/version/6132/5562/24039/6752_Goldberg_Composition1.png)

The first time I heard the word 'double-jointed' was in the classroom:

"Are you double-jointed?" one kid asked.

I remember standing, staring

at the carpeted floor

on which I usually sat

with my butt touching the ground

between uncrossed legs, knees forward, feet back

I felt natural, normal, neutral

(until

some kid said:

"You shouldn't be sitting like that –

it's

bad for you":

((my) (ab)normal ((way of) being))

was (construed

as ) a problem:

that needed fixing.

"There is no such thing as double-jointed,"

another kid piped in.

And that is how I learned:

1) I am double-jointed.

2) There is no such thing as double-jointed.

--

Sunday, August 12, 2012 ~1:17pm

Dear Diary,

Here I am at my kitchen table, eating kale chips I made myself-ish with L– after eating all the ones she had in the oven when I got home to find her (pot of soup on the stove)… [after my first Moksha class in forever, which I took to] see how it would work with my shoulder being how-it-is (that is, wonky, and subluxatey, and—finally—medically validated with a still-unknown diagnosis awaiting an MRI arthrogram, about which I keep getting non-news voicemails from my father with promises to keep me posted as his nepotistic connections pan out in getting me an appointment (or, so far, don't).

It was strange to see him—was it a month ago already? —in his element, overly familiar in his professional abode, striding through the offices and corridors (no door closed to him, Dr. G–, beloved old-timer whose career there has spanned several decades and departments) like he owned the place—or, rather, like it owned him. And in more than one way, it does, always has, since well before I came along I'm guessing. But not in an oppressive way, at least, subjectively, to him. He, its humble servant, doting son, tending to staff and patients alike with the loyalty and concern most reserve for their children, parents, lovers— and I, his only daughter, never knew this man, only saw him parodied in skits at his so-called retirement party, where one attendee sent me confused and full of a melee of strong hurt-angry-bewildered-sad feelings, nearly in tears, into the next room to call a friend after [she] assert[ed]:

"You're so lucky to have him as a father. Compared to your dad, Patch Adams looks like the devil…"

Anyways, after walking around for 2 weeks with a pinched nerve, I felt grateful for any help I could get in accessing "good" Western medicine—if I am going to have to go that route, which I probably wouldn't have moved towards so quickly if Dr. J–, who agreed to do a trade with me for osteopathic treatments, hadn't have, 5 minutes into playing with my shoulder and seeing my restricted range of motion (how I can only easily raise my right arm half-way in the front and to the side, as compared to my normally hyper-mobile super-human acro-yoga-teacher range), told me I ought to talk to an orthopaedic surgeon, that it was beyond his scope to fix me…

And, besides, my current father's actual care + help, even in his limited sphere, is a far cry from that one-of-my-earliest-memories "other-time-in-the-hospital-with-dad" encounter where, after falling from the bench in Papa's boat and cutting my head, we drove to the hospital where I was told I should go inside and "meet some nurses"—and proceeded to be held down by said nurses, literally kicking and screaming, while my father, using that in-the-best-interests-of-the-child/patient rationale, overrode any pretense of consent and put stitches in me, ignoring the screams my mom could hear all the way in the far-off waiting room:

"I hate you, daddy! I'll never love you again!"

And, if you substitute "love" for "trust", it mightn't be far from the truth.

And love, well, that's still a complicated feeling for me, one I've yet to totally feel comfortable with or comprehend, much of the time – except, perhaps when I'm feeling it, in its simplest form, acutely…

--

originStories:

You might ask your agnostic self

if there mightn't be a person-able

G-d

to credit/blame/thank/pray to

after all

because wouldn't it feel nice

to make the doctors wrong

and get access

to that ultimate authority

to explain

once and forever

we were all made this way

on purpose.

Anyways, we all agree now:

It wasn't just a pinched nerve.

Tuesday, September 25, 2012 11:21 pm

Dear God,

I'm trying that on for size, after returning from Kol Nidre services, in the Hart House Debates room with the vaulted wood ceilings lined with Celtic (?) imagery and gargoyles. Oops. Already lost the epistolary tone… I don't really feel comfortable I guess, even as a thought exercise, addressing G-O-D, even though I believe in the power of prayer and the potential for many of the benefits of a secure attachment relationship being available to those who can personify deity as an internally available listener.

Anyways, I am suddenly sleepy, after a long day of driving to Ajax with R–G– to find Dr. L–'s opinion that surgery is not an available option for my shoulder, then dinner at J–'s, then services…

Feeling optimistic, w/ an undercurrent of anxiety/dread/fear about the year to come.

--

Upon returning to Western Medicine

(because it's the only thing that makes sense under the circumstances):

prodigal daughter,

learn to listen

carefully

to

[doctors

(who)

don't like to admit

they don't know]

absolutely

everything

(and then

make up

your own mind)

--

Wednesday, June 4, 2013 9:14 am

Yesterday, I went to see Dr. [M–] + got a preliminary diagnosis of EDS (+ scoliosis, an unexpected tag-on).

Just waiting to see bloodwork (in ~2+ months) to see if I'm "classical" (in my genes) or just the hyper mobile [sic] type. It feels similar, if ever less "epiphanic," than the Parsonage-Turner Syndrome [diagnosis]—more a "yeah, I knew that" than "oh, that makes sense." It, on some level, terrifies me—to have it validated that I am (more) fragile + unrepairable (than most)—more actually not only on the road to death, but ever-increasing chronic pain + loss of mobility. And yet, validating (in a reduction of cognitive dissonance sort of way).

It makes me realise my internal incompatibilities, on some level, simply make sense – the young exterior w/ the old interior, that happy medium averages don't really work for me. It makes me want to write, while I still can sit. It makes me want to travel. To fuck. To die. Or at least fight for the right to die if/when the pain, the debility, should get to be too much.

--

Friday, June 7, 2013 9:31 am

Waking up in a whole new contextual world of EDS – realising my various oh-too-complicated quirks seem to be shared by others with this diagnosis (or Dx, as it seems to be called online)…

--

"If you hear hoof-beats, assume horses – not zebras,"

they advise young doctors

{to think

[everything

is genetic]}(.)

(but)

if you trace the DNA back far enough

aren't we all zebras 1

(metaphorically speaking)

?

--

Friday, July 31, 2013

Yesterday, I met w/ J– S– [Genetic Counsellor] + Dr. C– M– [Clinical and Metabolic Geneticist] to find out I'm being slotted into the Hypermobility type of EDS + have scoliosis (only 6 degrees in lower spine) + that's that.

--

Rarely Diagnosed

You're all so smart, the OT smiles.

(referring to us

"zebras"

who dazzle

her doorstep)

Well, it could be, I retort.

(Or else

you just need to be

(too) smart (for your own good)

(enough)

to navigate

the system

to make it

here…)

--

There's a picture:

(Somewhere)

(In an old house)

(In an old pile)

(Pre-digital)

my hand holding up my elbow

(Splotchy)

(By accident)

(Once-burned)

(Twice splattered)

after we kids skidded on

(Paint-thinned)

(Concrete)

(Around which: pylons)

(Placed to prevent people)

plowing right through

(Like we might have avoided)

(Except we were too busy)

(Playing)

(To notice:)

Only I fell.

(That slippery liquid was not water.)

Instinctively, we all jumped right in-

to the fancy hotel swimming pool

and the burning stopped

eventually.

My mother wanted a record

of the blemish

that might scar

and then I might never be

able

to be

a model

which seemed silly

at the time.

Posing, then

(I)

felt awkward, forced.

More than a decade later, the first

professional photographer for whom I modelled said

I was unique: the only one

with whom he'd ever worked so

self-directed: using the mirror

across the studio, ensuring my young body's near-limitless reach stayed in the range of "normal

(/) exceptional";

keeping all my parts in place: joints (not too) flexed; back (not too) arched; smile (not too) big.

I earned enough $ from that shoot to buy my own camera; it went everywhere with me for years until I loaned it to a girl from California who had lost her own in Peru. (She sent it back months later with a scarf and chocolate.)

--

"There is a lot of things I can do that you can't, you know."

"With that hand," he smirks.

"With this hand, yes."

-Lezlie Frye, "Fingered" (in Sex and Disability, 2012, p. 259)

--

Even after it dawned on me that something was "wrong-wrong" it wasn't obvious what I ought to do

about it.

That first week after my brachial plexus nerves spontaneously combusted:

life went on

around me

as usual

in the woods

at the festival:

all the fairies and food; and fun and music and tents; stars and starry eyes,

so

I turned my skirt into a sling

slung silver tinsel festive over my aching, fearful shoulder

took the paths

with more caution

than ever before

afraid even to hug

I smiled

(Except when I was wincing – it's amazing how many people couldn't tell

the difference)

--

We'd met before; we connected on the dock; flirted a bit.

If she noticed the self-fashioned sling

it didn't seem to make much difference

to her.

--

She needed somewhere to stay her first night back in the city; she was flying to Peru later that same week.

When she got to my place, she made it clear: she wasn't expecting to go to sleep. Not right away.

I did an inventory of my body:

Some parts couldn't move; others could.

Some parts hurt; others didn't.

--

"Those of us who can learn to be or seem 'normal' do so, and those of us who cannot meet the standards of normality usually achieve the closest approximation we can manage."

-Susan Wendell (in The Rejected Body, 1996, p. 88)

--

References

- Frye, L. (2012). Fingered. In R. McRuer and A. Mollow (Eds.), Sex and disability (pp. 257-262). Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Kilcher, J. (1998). Hands. On Spirit [CD]. Atlantic Records.

- Popik, P. (2010, Sept. 12). "When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses, not zebras" [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.barrypopik.com/index.php/new_york_city/entry/when_you_hear_hoofbeats_think_of_horses_not_zebras

- Wendell, S. (1996). The rejected body: Feminist philosophical reflections on disability. New York: Routledge.

Endnotes

-

"Zebra" (Popik, 2010, Sept. 12) is a term reclaimed by those with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome in reaction to the medical school adviso: "If you hear hoof-beats, assume horses, not zebras." Originally intended to encourage new doctors not to over-diagnose "exotic" conditions, the attitude underlying this saying has led to a tendency in medical professionals to overlook rare conditions when they do present.

Return to Text