As undergraduate students engage with disability studies coursework, they learn about sociocultural concepts that address issues of ableism, normalcy, equity, and inclusion of disabled people in all facets of society. A transformational ideological change in how students view disability often occurs during these courses. To further explore this phenomenon, I completed a study on the capstone course for a DS minor program at a mid-sized public university. Two research questions asked: 1) How do undergraduate students make sense of and understand disability while completing a DS course? and 2) Which pedagogical decisions made by course instructors promote undergraduate students' development of new understandings of disability? A review of the scholarship on DS pedagogy in postsecondary contexts and the transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1990) concept of critical reflection situated how these students' perspectives shift over a semester. The weekly reflection assignment of 69 students over two semesters were coded with qualitative methods. Findings include themes related to the process of reflection unearthing realizations and identifying both problems and solutions, connecting to moral obligation. The findings explore connections to the process of reflection while the students were within the liminal space of understanding course content that contrasted their prior assumptions about disability. I discuss implications for postsecondary educational pedagogical methods to understand and utilize the liminal space while teaching DS courses.

Major and minor programs focusing on Disability Studies (DS) have been emerging in institutions of higher education across the United States. In these courses, the instructors are tasked with the development of DS syllabi that introduce critical concepts to students from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds. Additionally, DS courses are developed with high aims for students as they are asked to develop a critical lens toward disability. Their initial medicalized and positivistic notions about disability are often uprooted (Jarman & Kafer, 2014; Vidali, Price, & Lewiecki-Wilson, 2008). This challenging of preconceived ideologies may lead to the students transforming their prior conceptions of disability.

This transformation occurs while undertaking DS coursework, due to students learning about concepts that are fundamental to DS as a field. They engage with sociocultural concepts that address issues of ableism, normalcy, equity, and inclusion of disabled people in all facets of society. Additionally, DS students work toward multi- and inter-disciplinary inquiry, education, and practice to learn critical perspectives and discourse on disability within their own disciplines (Danforth, 2014; Baglieri & Shapiro, 2012). The recognition of models to explain the phenomenon of disability (e.g. social model, medical model, charity model, rehabilitation model) is one avenue for understanding the experiences of disabled people from myriad perspectives. For students in DS courses, this is often their first introduction to this new view of disability (e.g. Paterson, Hogan, & Willis, 2008).

At institutions of higher education, DS major and minor course work is a site where concepts fundamental to a DS mindset are presented, discussed, and have potential to lead to transformative changes in how students (re)consider disability. The social model is taught as one fundamental aspect to many DS program curricula and reveals a politicized viewpoint on the disability experience (Slesaransky-Poe & Garcia, 2014; Dewsbury et al., 2004). Additionally, the entrenched history of disability policy development, including disability activism that emerged from the disability rights movement in the United States in the 1960s, has continued to raise awareness of disability as a societal construct (Ferguson & Nussbaum, 2012; Oliver, 1996). As such, DS is an ideological, activist, discipline affirming such sociopolitical components of disability like the ableist effects of residing within a capitalist economy. Often these societal issues spiral into creating environments with barriers that result in conditions that lead to lack of access and need for accommodations for disabled people (Oliver, 1996).

Studying a Disability Studies Course

Acknowledging the need to research postsecondary DS courses and the transformative effects these courses have on students; I completed a study of the capstone course for a DS minor program at a mid-sized public university. Prior to the start of the study, the course instructors noted their observations to me about their students' perspectives of disability evolving over the semester, as evidenced in work samples and class discussions from previous semesters teaching this course. As articulated by Paterson, Hogan, and Willis (2008), in their work with nontraditional students who were in the workforce, this is an observed phenomenon for students undertaking DS coursework:

After some exploration and time in the program, however, a shift begins to happen and students start to look within. It is scary…to realize what they do not know and how much they have to learn in order to "better" themselves. This realization puts [students] in a vulnerable spot, knowing how far they have to go."

I wanted to further explore how undergraduate students experienced their understanding of disability studies and completed a qualitative analysis of their reflection responses to course material. Two research questions guided this study: 1) How do undergraduate students make sense of and understand disability while completing a DS course? and 2) Which pedagogical decisions made by course instructors while they were planning the course served to promote undergraduate students' development of new understandings of disability?

The Disability Studies Course

The course aimed to challenge students in reconsidering their preconceived notions of disability, which often resided within a medicalized model of understanding concepts related to disability. The students in the course were enrolled in major programs from throughout the university, with the majority from "helping" professions such as: Human Services, Early Childhood Education, Elementary Education, Special Education, Psychology, Cognitive Science, Exercise Science, or Health Sciences. Since this was the capstone course for the DS minor, many of the students already had experiences working with disabled populations, either through personal experience or through fieldwork in their undergraduate courses, by the time they took the course in their Junior or Senior year of their undergraduate programming.

The course consisted of full class meetings for weekly guest lectures and division of the class into four discussion sections which met separately. From the perspective of the students, they met twice a week: once with the full group for a guest lecture, and again for a small group discussion session. The weekly lectures featured live and/or remote guests who were disabled or who worked closely with disabled people. The intent of these guest lectures was to provide and promote an insider's perspective on being disabled and the daily reality of the systemic issues facing disabled people in today's society. Then, later in the week, the students met in their smaller discussion sections to debrief and reflect on the guest lectures and assigned readings.

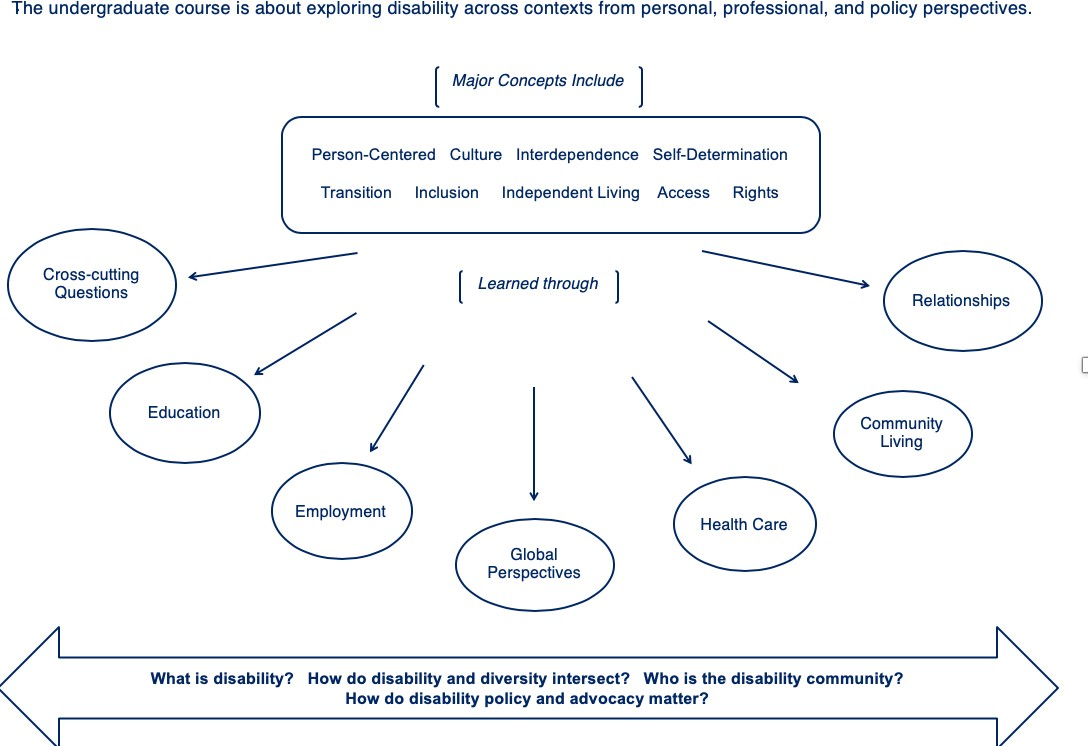

Topics related to disability history, employment, healthcare, education, community living, and relationships/sexuality were covered (See Figure 1). The students related to these topics every week through the guest lectures, reflection assignments, and in-class discussions in the smaller discussion section class. The in-class discussions occurred in small and large group formats, often discussing the reflection assignments and what resonated from that week's guest lecture. Pedagogical resources such as videos, brief in- class readings, and referencing homework readings that targeted each week's topic were also used (see appendix 1).

Additional assignments included reading a memoir written by a disabled person and developing a paper reflecting on the book. Also, an in-depth small group interview project with a disabled individual and/or their family was worked on throughout the semester. This project culminated during finals week with multi-media presentations about the personal history and current experiences of the people they worked with, often in collaboration with the person they interviewed. The disabled people they worked with over the semester were invited to these presentations as attendees and to provide vital feedback on their experiences.

Reflections

There were two types of reflection assignments, reading reflections and learning reflections. During each discussion section the students were asked to complete one type of reflection with this assignment alternating weeks. These reflection assignments were developed with the aim to provide the students the space to respond to the often ideologically challenging content the students had been learning during the course.

Reading reflections

Every other week the students came to class with the reading reflection completed. These were reflections developed as a homework assignment, which they turned in prior to class. The purpose of these reading reflections was to assist the students with digestion of the reading material and to support in-class discussion. Additionally, the students were divided into small groups, with each group given a different reading reflection prompt. On the day of a reading reflection assignment, the small groups met and discussed their reflections with each other, then the class would have a large group discussion about each prompt. Structuring the assignment this way encouraged the discussion sections to engage and, at times, challenge each other.

Learning reflections

The learning reflections occurred during the last 15 minutes of class time. These reflections supported the students in building on their understanding of the content, the readings, discussions, guest lectures, discussion section activities, and their prior reflections that had been covered during the two weeks that they had been discussing a topic. The entire class was given one prompt and developed brief responses individually in class.

Review of Literature

My interest in the intersection at student understanding of disability and the application of pedagogical methods informing that understanding is a central aspect to this research. In order to make sense of the reflection assignments as they pertained to my research questions, I applied transformative learning theory's concept of critical reflection to my exploration of how these students' perspectives shift over a semester. Transformative learning (TL) guided me toward understanding how the students underwent reflection on DS content. I also completed a review of the scholarship on DS pedagogy in postsecondary contexts in order to see how DS pedagogy has been applied in various DS course contexts that are both similar and different to the ones used in the course I studied. These areas of scholarship united to unearth the student's transformative experience of residing within the liminal space while being placed within a DS educational context.

Disability Studies Pedagogy

The use of specific pedagogical methods is important to consider when teaching a DS course. There are connections to be made between the experiencing of the course content and the pedagogical methods an instructor can employ to support their students. The content of DS courses is often new and challenging to students, who may have difficulty grasping and dealing with the tension between their prior notions and what now resonates with them. Such content should be approached with care. Thus, the study of pedagogical methods that have been successfully developed in courses covering DS content is required in order to sensitively guide students through processing this new information.

The teaching of DS concepts at the university level within teacher education programs has been broadly explored (e.g. Pearson et al., 2016; Connor, 2015; Erevelles, 2015; Llavani & Broderick, 2013; Ware, 2013; Hulgin et al., 2011; Baglieri, 2008). In particular to Disability Studies in Education (DSE) scholars, the pedagogical methods used to incorporate DS concepts into postsecondary teacher education courses have piqued their interest, due to the novel approach DSE provides in contrast to special education. Connor (2015) details his pedagogical methods in an inclusive practices course framed by DS/DSE theory which led to students experiencing shifts in their perceptions of disability. These methods included an emphasis on the experiences of disabled people, critically viewing the special education system and foundational philosophy, use of DSE-focused texts and films, deconstructing disability representation in film and media, and a reflective assignment on observations of disability in students' daily lives. In another traditional special education course, problem-based learning with case studies was applied to enhance DSE concepts (Eisenman & Kofke, 2016). Also, Ware (2013) described her use of "media exemplars" to ensure connections were made to disability literacy and the use of arts-based assignments.

Pedagogical practices in DS courses have been reflected upon in recent scholarship. The recent Disability Studies Quarterly 2015 special edition, Interventions in Disability Studies Pedagogy, engages with novel pedagogical practices that embody the DS content that the instructors teach. Also, several papers in that edition explicitly detail the pedagogical methods, the assignments, and content, that they felt were worthwhile to their course aims. Derby and Karr (2015) engaged in content related to ableism through arts-based assignments. In their partnership with learning disabled individuals at a university in the UK, Greenstein et. al (2015) discuss the intentional transformative impact of co-teaching as praxis through providing insider perspectives in their course. When instructing a writing course about normalcy, Selznick (2015) provided opportunities for multimodal compositions and she details how discussion of normalcy is key content for a DS course.

Reflection activities are often applied as a pedagogical tool in both teacher education and DS programs, as a mechanism for students to make meaning of disability and DS concepts (Connor, 2015; Baglieri, 2008; Cypher & Martin, 2008; Lower & Dreidger, 2008). Lower and Dreidger (2008) discuss how a self-reflection assignment assisted the students with deepening their understanding of disability in their own lives and their own experiences as disabled people. Cypher and Martin (2008) employed reflection activities stemming from purposeful DS reading assignments with the aim of engaging their students in the process of critical thinking. In their reflective article about their DS course, Cypher and Martin came to realize, "Disability studies forces students to question the validity of their old assumptions and complicates notions that most students believed were settled prior to the course…" Put differently, engaging in reflection has the potential to support student's undertaking of their transformation of their prior stance on disability.

Critical Reflection toward transformation

Transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1990, 1991) inquires and examines how adult learners undergo changes in ideological perspectives. According to Mezirow, once a disorienting dilemma is presented it is possible to transform preconceived assumptions with the combination of three key ingredients: authentic experiences, critical reflection, and dialogue (Mezirow, 1991, 1998). While all ingredients are necessary for ideological transformation, there has been a call by the scholarly community for in-depth examination of the transformative process (Snyder, 2008). For the purposes of this study, critical reflection was singled out for further exploration as a pedagogical method initiated by the course instructors. This course in particular was of interest to study within a transformative framework due to consistent opportunities for students to develop and discuss their reflections and the experiential assignment encouraging students to interview an individual or family member affected by disability. Thus, the course provided all components of Mezirow's recipe for transformation of preconceived assumptions.

Critical reflection assists learners in making changes to their meaning schema and even in triggering a transformation (Mezirow, 1990). The critical nature of reflection is connected to postmodern understanding of power relationships within social and political realms (Kreber, 2012; Brookfield, 2005). With regard to understanding what reflection can do for the learner, Mezirow (1990) states:

Reflection enables us to correct distortions in our beliefs and errors in problem solving. Critical reflection involves a critique of the presuppositions on which our beliefs have been built (p.1).

He also considers the following:

Transformative learning involves a particular function of reflection: reassessing the presuppositions on which our beliefs are based and acting on insights derived from the transformed meaning perspective that results from such reassessments (p.18).

As such, critical reflection is connected to challenging preconceived assumptions learned in formal and informal outlets. A student embarking on a transformation may have uncertainty in their transitioning thought process. Critical reflection assists with the development of these changes and the struggle to understand new perceptions. Critical self-reflection requires the awareness and upheaval of preconceived assumptions which may result in personal transformation of one's worldview (Mezirow, 1998).

Transformation through the liminal space

Another key facet to TL theory is the experience of residing within the liminal space while undergoing a transformation. Batchelor (2012) citing Conroy (2004) provides the following definition of the liminal space:

Liminality, therefore, expresses a state of limbo, an ambiguous period in which individuals are in between a phase of their lives that is known and past and a phase of their lives that is unknown and yet to be experienced (Conroy 2004). (p. 598)

Throughout the course, disability was situated within a sociopolitical framework, with in- depth discussion about the social model formulating the discussion within each week's theme. Similar to Picower's (2013) use of a social justice orientation toward instruction, the instructors sought to develop the course with the intent to discuss the politicized nature of equity and its intersections across society. In this respect, the reflection assignments intended to unearth issues of equity that disabled individuals experience on a daily basis in the United States and around the world. Reflecting on these concepts led the students to many realizations that revealed they were experiencing a liminality while engaging in their reflection.

When students are experiencing a liminal space while completing reflection assignments, reflection becomes a pedagogical activity initiated by the instructor that engages a student in better understanding of their identity. Malkki (2010) discussed how reflection is a holistic process incorporating social, biological, and emotional components. The "comfort zone" and "edge emotions" are key aspects contributing to the process of reflection. As individuals embark on changing their meaning perspective, reflections become multi-dimensional (Malkki, 2010). When faced with new ideology, individuals reflect upon prior assumptions of their worldview and reside within a liminal space while making sense of new meanings (Berger, 2004). The students in this study were found to be experiencing liminality in myriad ways, which will be expanded upon below in the findings and discussion sections.

Methods

The DS Course

This study was designed with several components in mind to answer the research questions. The data collection included qualitative analysis of the students' reflection assignments as well as in-class observations of the weekly full class lecture and one of the two break out discussion sections. This was a rich data set that provided much information for a detailed, qualitative analysis.

I completed a qualitative content analysis to reflection assignments occurring weekly during the DS course offered at a public mid-Atlantic university. In my role a researcher, I observed the course over two semesters. I observed the weekly guest lecture and one of the discussion sections per semester, attending most of those class meetings. All instructors were included in the research team as peer de-briefers. One hundred thirty- one junior and senior students from various majors around the university (e.g. teacher education, health science, cognitive science, exercise science) were enrolled during the two semesters studied, with my study focusing on the observations and reflection assignments of the 69 students enrolled in the sections I observed.

This study underwent Institutional Review Board approval and students provided consent for analysis of their work samples and in- class discussions to be used in this study. At the start of each semester, when the entire class was grouped together for their first class, I passed out and read the consent forms, reviewed the nature of the study which included stating that I would be observing some of the classes, would have access to all of their assignments and potentially quote their work in the final manuscript and dissemination activities. I also discussed that their names and location of the university would be anonymized. The students had the opportunity to leave the study at any time. I collected their consent forms that day, and developed a spreadsheet aligning the students who provided consent with the students who did not. All of the students in the discussion sections I observed consented to participate in this study.

Data Collection

Reflection assignments

Reflections were submitted on a weekly basis, with a total of 13 reflections completed per student. Reading reflections asked each student to respond to one of four questions pertaining to that week's reading assignment. The questions were designed to prompt synthesis of ideas across the assigned readings and course themes. Learning reflections asked students to write a brief reflection during the final 15 minutes of every other discussion section. This reflection corresponded with the conclusion of a course theme during the second week it was discussed. Examples of the reflection prompt are provided in the appendix.

Observations

I performed participant observations of course lectures and in- class discussions documented with descriptive field notes.

Data Analysis

The reflection assignments underwent a qualitative content analysis coding and thematic development process. The data analysis began during the first semester using an a priori coding scheme based on common concepts from DS literature. Having been granted access to the course online learning management system, I read through the reflection assignments as they were completed and turned into the professors, taking informal notes as I read. I also completed detailed field notes while observing the classes during the semester, which served as the data for the specific pedagogical methods used in each class observed. Following the conclusion of the courses, the reflection assignments were uploaded into an online qualitative research software system where an open coding process was completed with line-by-line axial coding and close reading of the reflection assignments. These initial codes then went through a low-tech process using notecards with the codes written on them, that led to the categorization and determination of the broad themes presented below. (Creswell, 2012).

Findings and Discussion

The concept of liminal space is central to the findings in this study, pertaining specifically to the first research question. This analysis of reflections assists with understanding the liminal aspect of burgeoning ideological transformation (Snyder, 2008). Berger (2004) discussed the concept of her students residing on "the edge of knowing" and how an instructor can have a supportive role for students through the liminal space:

I began to think about the kind of reflection that seeks to create new forms of thinking, new discoveries—reflection that takes us to the edge of our meaning. It is this kind of reflection that we believe has the most power to be transformative—to move outside the form of current understanding and into a new place. (p 338)

Bailey, Stribling, and McGowan (2014) concluded of their students (who were active teachers at the time), "teachers look more critically at their identity; refresh their awareness of how knowledge is created, maintained; and passed on, and absorb ideas around discomfort" (p. 261) while they are within the liminal space.

The nature of the reflections was highly variable across students. When I read over all of the reflections, I observed that many of the students were in the process of learning to reflect on their preconceived ideologies of disability through uncritical reflection. This kind of reflection often summarized the readings in response to the prompt, or the student did not take the extra step in making connections to the experiences of disabled people. Additionally, there was much variability in the critical take each student provided each week. The same student could have deeply reflected on the topic one week, then the next week provided a cursory reflection. The reflections excerpted in the findings below were from the students who completed a critical reflection. These students were engaged in deeply understanding the new concepts they were learning. They contrasted these concepts at the intersection of what they learned from the readings, or the experiences either they had with disabled people or their own experiences, and understanding the sociocultural power relationships that shaped the marginalization of disabled people. These are the reflections that engaged deeply and critically with the learning and reading response questions and serve as an understanding of how students communicate their liminality through the mechanism of critical reflection. Much can be learned about the liminal space of transformation through the analysis of the students' reflections.

The findings reveal students had myriad understandings of disability while being liminal. The most striking aspects are in the exploration of how the students processed their reflections on the course material. The themes present a behind-the- curtain view of critical reflection grounded in the students' own assumptions, realizations, and moral beliefs regarding disability. The pedagogical methods used in the course were referenced frequently, with comments about in-class discussions and guest lectures, along with reactions to assigned readings. As anticipated, preconceived notions of disability were often challenged and culled in these reflection assignments. This section concludes with connections to the students residing within the transformative learning concept of the liminal space.

The Process of Reflection

Themes pertaining to the first research question asking how students made sense of disability included: unearthing realizations; and identifying problems and solutions, connected to morality.

Realizations

The students' reflections on aspects of disability led to new realizations about their preconceived notions. Their realizations were observed in statements directly stating a new realization, by stating they found something interesting, or through agreeing and/or disagreeing. At the same time, many of their emotions as they went through the process of realization through reflection was effectively conveyed.

Mindy discussed her insights about broad societal values and contrasted them with her new realizations about societal construction: She stated how she "noticed" many issues that were brought to light for her:

…there are many underlying social values that I have noticed. First, society likes to put people into socially constructed boxes. These boxes relate to one's gender, sexual preference, etc. By placing people into these socially constructed boxes, society is easily able to understand how others should act. When someone does not fit into these social constructs, society pushes against their thoughts.

In this excerpt, Mindy discussed her perspective on the role of the social model of disability, while intersecting and broadening the social model with other identity constructs beyond disability, like gender or sexuality. She realized when people are different from the social norm it is the society that does not value them. This is a powerful realization that she succinctly reflected upon through the structure of "socially constructed boxes."

Fiona provided insight into the role of emotion in processing reflections. Her emotions served to help understand new information she learned in class about health care for disabled people:

It is baffling that people who are blind may not have access to braille or large print, depending on their needs, or that some locations are not wheelchair accessible which is also illegal anyway…I was shocked to read that studies have shown "much lower rates of screening mammography and Pap tests among women with disabilities than among those without" (Iezzoni, 2011, 1950-1951). How is this still going on? This has to be considered malpractice and illegal!

In her assessment that that health care system is "baffling" and that she was "shocked" about many of the realities of healthcare for disabled people, she is demonstrating emotion in her reflection. She is upset and engaged with empathizing with the stories of disabled people.

Celine framed her realizations in her first reading reflection by stating how "interesting" it was to learn about the disability rights movement:

It is so interesting that the factor that set the precedence for how unconstitutional it is to take away minorities rights including individuals with disabilities was not directly related to disabilities but was fighting on a different issue. As well it also showed disability rights movement activists what they needed to do, what they needed to say and how to do it in order to get the legislation and back up they needed to ignite a disability rights movement. It was really interesting to read the articles about the events that led up to these legislative changes and movements and how influential other historical events were on each other.

In this framing of "interesting", Celine is expressing how she realized the activist historical implications on the rights of disabled people. By mentioning the precedence for disability rights was initially on "a different issue" she referred to the work of the civil rights movement. This shows a burgeoning realization that in finding disability history interesting, she is also understanding the intersectional nature of civil rights issues.

Students processed their realizations learning new material through agreement and disagreement with readings and discussions. Ariel, an exercise science major, agreed with the content and outlined her conclusions about disability education policy:

I agree that the term "appropriate" here can lead to segregation in an unfair way for a child with disabilities. Something that is appropriate changes from situation to situation and from thing to thing…IDEA does segregate students into different classroom types depending on the severity of their disability. This means that the Brown decision that separate is not equal has been negated. I don't believe that this was the intention but IDEA needs to be redefined to provide a more inclusive education for children.

However, Monica, a special education major, stated her disagreement by contrasting her previous experiences with information presented in the course readings:

I have a lot of experience with special education. I love special education and it is a passion of mine. I really questioned some of the things the authors wrote in their articles. I disagree with one of the ideas presented in the article…I do not believe that LRE is the general education classroom for all students…The whole idea of special education is individualized goals and instruction to meet each student's needs. Just because a student is in special education, does not mean they will all have the same LRE.

Special education teacher preparation programs are often framed from a medicalized, behaviorist perspective. It is not surprising that Monica, and other special education majors in the class, experienced resistance to a reading about full inclusion. Monica stated her passion for and experience in special education as evidence that she is equipped with the knowledge to sufficiently resist understanding full inclusion. Disagreement is one mechanism toward ideological change. As Monica reflected on her disagreement, this may lead to more engagement on unearthing what she is disagreeing about and why.

To expand on the variety of agreement and disagreement specifically from special education majors, it is useful to analyze some of the other realizations made by these students. Special education majors, June and Aurora, had their own aspects of agreeing and disagreeing with the readings' views on special education. June expressed how the readings helped her understand what she already knew about special education, but also acknowledged the tensions in her continued resistance to how the reading portrayed special education:

The readings this week has allowed me to think about special education from a different perspective. When reading the "Institutionalized Inequality" article, this sentence about special education stood out to me: "The field must continue to produce the problem it was created to serve". I never looked at teaching special education in this way. I have been trained on different ways to help students with special needs and how to identify these needs in a classroom. This article is stating that the entire field of special education is based around this idea that if a child is not "normal" then we need to give them specialized education to make them "normal". I disagree with that statement because I do not see special education as a way to conform students into acting the "correct" way in a classroom, I see it as helping each student be successful in their own way.

Aurora, on the other hand, expanded on her agreement with some of the readings about educational placement. She described her experience working with a student from a Latin American country whose primary language is Spanish:

I found that the readings for this week affirmed my understanding of special education that I had developed during my student teaching experiences…

My special education placement took place in a self-contained, special program classroom for students on the Autism Spectrum. During my first month in the classroom, I was able to help transition a student from our classroom to a general education classroom because it was determined during an IEP review with his parents and support staff that our classroom was too restrictive for this child. He had been placed in this class after moving to [state] from [Spanish-speaking country] and it seemed like this room was most similar to the experience he had in [Spanish-speaking country]. After conducting the meeting we learned he had been in day-care and had not been enrolled in public school. It was also determined that the student had a developmental delay but not Autism and this was news to the school staff as there was a language barrier that made things challenging up to this point. The student began the transition to a general education classroom where I saw significant growth from interacting with typically-developing peers. He began speaking and understanding English faster than he did in the special program classroom and was learning how to socialize with his peers.

She concluded her reflection stating, "I learned how the Least Restrictive Environment is the regular education environment but it is not appropriate for all children at all times." Although Aurora developed an intersectional analysis of how disability in educational spaces can affect students and families whose primary language is not English and her analysis of agreement with the readings and utilized her personal experiences to reflect on the readings, she continued to politely challenge the notion of inclusive placements for all students.

In completing their reflections on disability concepts, the students were able to process new information, come to new understandings of how disability is perceived in today's society, and better understand this new viewpoint, even if they were not quite ready to incorporate the new perspective into their personal ideology. As students came to these understandings, emotion was evident in their writing, which can be observed in Fiona and Monica's reflections above. Malkki (2010) notes the myriad dimensions to reflection, including emotional, social, and cognitive. According to Dirkx (2001), emotion can be a tool to assist better understanding of one's world and contribute to ideological transformation. Mezirow (2012) also determined that emotion is a necessary aspect to transformation. The students were concerned they had not been privy to the alternative views of disability presented in the course. While unearthing their realizations, they experienced many emotions including shock, frustration, agreement, and sadness.

Problems and solutions connected to morality

Students often discussed problems and corresponding solutions to issues related to disability. Several of the solutions can be interpreted as a moral obligation that our society should collectively understand the role of stigma and unfair disadvantage for disabled people. The moral imperative of inclusionary practices and providing accommodations to people with disabilities were evident in their responses.

Diana provided a rich discussion of disability stigmas and the intersection with minority populations:

Taking the step to get rid of stigmas is similar to the step taken to better the healthcare for people in general with disabilities. In both situations, stigmas must be taken away in order to ensure that the minority group, whether it be race or someone with a disability, gets the same necessary care that others get. On the other hand, it also differs, because the stigmas that need to be taken away are different. In reference to healthcare for minorities with disabilities, the stigma that must be stopped is that minorities do not need as good of care, or that they do not deserve as good of care as the white population.

Her problem and the solution directly related to racist problems that have been observed in healthcare. By framing the problem as an issue of disability stigma, she succinctly outlined an intersectional analysis of how disability stigma affects "minorities" differently in how they receive healthcare. Calling attention to the racist implications of the different treatment of different populations of people appeals to a moral sense of unfairness.

Ivy also discussed healthcare. She portrayed her solution of education for healthcare professionals as imperative, "The proper resources, education, accessibility, and training need to be provided for healthcare professionals to ensure that people with disabilities are being treating the same as people without disabilities." By making the connection that educating healthcare professions lead to better treatment for disabled people, she is reflecting on a solution to the unfair treatment of disabled people.

Ariel reflected on the issues of the IDEA segregating students and made connections to desegregation policy:

IDEA does segregate students into different classroom types depending on the severity of their disability. This means that the Brown decision that separate is not equal has been negated. I don't believe that this was the intention but IDEA needs to be redefined to provide a more inclusive education for children

In this excerpt, she provided understanding of how the intention of the law can become lost once the law is enacted. Her understanding that the IDEA is a mechanism for segregation implies her moral understanding that full inclusion can only happen once the IDEA undergoes adjustments that supports inclusion in school.

Christy also commented on how students need to be included in general education: "Every child learns and acts differently, and having a diagnosis of a disability should not change whether or not they can be in normal class setting." Her use of the word "should" indicated her moral imperative for including students based on their disability diagnosis. In other examples of the moral use of "should", Layla described her perspective on sexuality as, "…a social value is sexuality, and gender, and since non- disabled peers have the right to their own bodies, and their own sexuality, the same rights should be given to those with disabilities." In discussing the CRPD, June suggested, "Because the U.S. is such a world power we need to use our influence to help other countries and recognize that people with disabilities should be given equal treatment." These statements imply that our society can do better in the treatment of disabled people, and there are common-sense solutions to each issue that arises.

The moral/ethical understanding of prior and novel assumptions is an understood component to critical reflection (Mezirow, 1998). The ethical inclination toward understanding disability has been explored in higher education settings, with students purposefully deconstructing their ethical perspectives of disability (Erevelles, 2015). In their reflections here, students described their moral concerns and connections to common assumptions about the disability experience. They demonstrated a strong sense of morality when discussing which services, supports, and/or accommodations should be in place for disabled people to thrive. The moral imperative of inclusion of disabled people through accommodations in the community was evident in the reflections. Students situated their moral sense within the context of a problem with a corresponding solution discussed and read about in class.

Pedagogical References

The discussion sections of this course both required and provided the time for effective discussion and discourse between the students and between the students and instructor. Each instructor applied their own pedagogical practices to facilitate discussion of concepts that were often new and, at times, disturbed the preconceived ideologies of the students' understanding of disability. Across all instructors, there was use of their personal experiences with each concept, which served as a social springboard for the students to have a back and forth dialogue with each other and with the instructor. When the instructors were candid in this manner, there was a reciprocal relationship with the students sharing their reflections of personal experiences with disabled people, or their own experiences as a disabled person, that related to the week's topic.

Drawing on excerpts from the memos I wrote in the first semester of observations, I integrate some examples of the pedagogical methods applied to foster discussion. I noted how the methods varied across instructors. That semester, the majority of my observations were primarily with one instructor (Instructor 1). When the opportunity arose, I observed the other instructor (Instructor 2) and noted their pedagogical differences facilitating discussions in their class:

After observing [Instructor 2's] section, it looked to me like [they] utilizes some more structure to [their] sections. Those students knew they would need to talk out, and that it would be a different student in their group each week who would have their turn to talk. [Instructor 2] goes around the room to each group and ensures every group has a chance to share their thoughts. [Instructor 2] also directly stated [they] would call on "volunteers" if there was a lull in the discussion.

I contrasted this more structured approach to the instructor I was primarily observing that semester:

In [Instructor 1's] sections [they] encourages discussion through follow up questions and promoting time to consider how to discuss the concept. [They] does this by asking a question then waiting for the students to respond. Sometimes a series of long pauses can create discomfort. I wonder if this discomfort impacts the students' willingness to continue with the discussion. [Instructor 1] seems to combat this effect by continuing to ask follow-up questions, or clarifying the question further. This strategy often works.

Both of these pedagogical decisions for class discussion was fostered from the outset. When the instructors started the semester there was a clear expectation that this was a discussion section, which entailed dialoguing with classmates and the instructor about the reflection assignments, in-class activities, and readings. Regardless of how it was incorporated, in each discussion section the students were divided into groups and in these small groups they reviewed their reflections. Then the instructor incorporated a full class discussion, after briefly checking in with each of the small groups. These pedagogical practices served to support the students in their reflections.

Within the reflection assignments, students made direct statements regarding the pedagogical methods used in the course (e.g. in-class discussions, guest lecturers, assigned readings). These methods were used to further their understanding of disability. In her remarks about their class dialogue, Andrea stated: "In our class discussion today, we discussed a lot about how SSI and SSDI both do not inspire workers to reach their full potential." Additionally, Terry referred to a short video they watched:

And what surprises me the most about the issues with transportation is the fact that they keep occurring. The woman in the video claimed that there have been thousands and thousands of complaints regarding that specific transportation system, and nothing has been done to improve it.

Christy provided an example of referencing several methods to promote her perspective of special education policies:

Based on all of our readings, presentations, and discussion I think one way in which discrimination manifests in special education policies or practices is by race. I saw this a lot in the one reading that talked about disproportionality in special education. It discussed how it is typically seen that African American students are more often placed in restrictive environments, which isn't always their least restrictive environment, where they deserve to be. We also talked a lot about race in discussion today in terms of seclusion and restraints. It was discussed how it may be more typical for people of a minority race or lower socio-economical background to be put in restraints, most of the time, undeserved.

These pedagogical methods were purposefully applied by the instructors in order to support the students as they worked through uncertainty and liminality. When framed within a transformative lens, the course reading assignments served as a disorienting dilemma, which provided a springboard for further processing of DS concepts, and students offered their personal insights in response to the readings. The course instructors consistently facilitated full and small group discussions that were subsequently referenced in the reflection assignments. It was not simply the act of assigning reflections, but the additional use of the reflections which was impactful for processing novel DS ideas.

The Liminal Space

The findings from this study acknowledge and further explore experiencing the liminal space. This is a unique analysis of the reflections of undergraduate students from various disciplinary backgrounds. For many of the students in this course, the DS orientation of concepts presented what Mezirow (1991) terms a "disorienting dilemma.". As suggested by Snyder (2008), I sought to identify how students reflected and worked through their experience on "the growing edge" (Berger, 2004).

The themes developed from this deep analysis of students' reflections provide a snapshot of the experience of residing within the liminal space of transformation. While engaging in the act of understanding new material, these students actively wrestled with tensions that surfaced in their emotional realizations and while devising moral solutions to problems. Connected to their understanding was the adept use of pedagogical methods, such as providing weekly opportunities for small group discussion and activities promoting the first-person experiences of disabled people.

Batchelor (2012) provides commentary on students in higher education being liminal and residing in what she terms, "being on the borderline." In this conceptualization of the liminal space students in higher education settings are at risk of being marginalized when they are experiencing this borderline status. I want to expand on this concept with regard to the students here and what was revealed about the liminal space specific to learning about DS concepts. The majority of the students participating in this study came from major areas of study that focused on "helping" professions, such as: special education, human services, psychology, or exercise science. In these disciplines, which are largely taught outside the DS minor, disability is framed within the dominant medical model lens. The DS perspective the students learned in this course unearths additional emotions and reactions, due to how disability has been previously constructed over their undergraduate careers. Keeping this context in mind, these students are experiencing being placed on the margins of their own disciplines, as they are some of the only students in their major areas of study who have been exposed to DS ideologies. This outcome of experiencing liminality has several implications for postsecondary educators.

Implications for Postsecondary Education

The findings from this study assists DS faculty with development of transformative methods in their courses and provides further nuance to the understanding of pedagogical methods. A better understanding of the experience of residing within the liminal space of transformation was unearthed in this research. Additionally, these findings may assist faculty engaged in teaching transformational material. The concept of the liminal space is important for any educator presenting transformational material to deeply understand. Vulnerability occurs when experiencing the liminal space, which results in increased emotions as students struggle to make sense of new information presented in contrast to previously conceived assumptions. This leads to better insights for professors seeking to understand how to support students who are seemingly resistant or have emotional reactions to course content. Additionally, when students are experiencing "being on the borderline" they may face marginalization from their mentors and peer groups. Without a strong community of supportive individuals to assist through the liminal stage of transformation, many students could resist, or appear highly emotional, the transformational material covered in class.

There are nuances to consider when understanding that course material could engage students in the liminal space. It is not simply the act of assigning reflections, but the additional use of the reflections and their connection to other pedagogical tools that was powerful for the students in this study as they processed novel DS ideas. Critical reflection in combination with pedagogical methods that contribute to transformation, such as opportunities for discussion, and providing experiences, such as lectures about and by those undergoing the course concepts, assisted these students with reflecting on their realizations of new assumptions. Through confronting the transformational nature of their content, professors can plan to utilize pedagogical tools to support students working through complicated ideological concepts previously unknown to them.

Berger (2004) provided recommendations to facilitators working with students in a liminal space: "1. helping students find and recognize the edge, 2. being good company at the edge, and 3. helping to build firm ground in a new place" (p. 346). Critical narrative reflection has great potential to support these recommendations. This important pedagogical tool can serve to assist students residing in the liminal space of awareness of new assumptions and work toward incorporating them into preconceived worldviews.

Conclusions

Erevelles (2015) "argue[s] that disability studies can radically intervene in higher educational contexts" (p.173). The incorporation of DS concepts in higher education has much potential to result in a transformative effect on how students view aspects of disability (Pearson et al., 2016). Often the instructors are deeply committed to DS principles and develop courses with the intent to transmit their excitement about disability issues to their students (Connor, 2015; Llavani & Broderick, 2013; Ware, 2013). Although DS courses are often designed with the educator's passionate stance to create a transformative environment, students still may express resistance, or struggle to understand this new outlook on disability (Hulgin et al., 2011). This expression of student vulnerability needs to be recognized and dealt with in a manner that does not necessarily reflect on the professor or the content. It is a natural reaction to their new understanding of the course content that may result in uprooting their ideological identity.

The students who enrolled in the DS course in this study were presented with conscious-raising sociopolitical material in the form of readings, guest lectures, and videos, which often served as a disorienting dilemma. They were provided with opportunity to process their reactions to the inequities of disabled people in the United States and around the world. Reflection assignments were one of several activities used throughout the course in addition to weekly in-class discussion in small groups or with the whole class and other assignments. With this study, I sought to explore critical reflection specifically as a mechanism to promote ideological transformation and to better understand its use within the instructors' praxis. I also wanted to explore the experience of the liminal space.

The findings here serve as an observation of how critical reflection can unearth the experience of the liminal space. The students' emotional reactions and evolving relationship with their moral consciousness suggests their struggle with new concepts about disability. An environment promoting queries and concerns regarding preconceived notions about disability supported these students while working within "the edge of knowing," as described by Berger (2004). There is great potential to contribute to the study of transformation through participation in a DS course or program of study. However, due to the lack of interviews with students or possibility for longitudinal follow-up, this study was not able to fully focus on transformative impact.

Through illustrating the process of critical reflection as a transformative practice and creating a snapshot of the process of reflection, I intend for this research to serve as an exploration on the insights into the experience of residing within the liminal space. When students experience the liminal space, they are in a vulnerable position with increased emotions as they struggle to make sense of new information presented in the face of previously conceived assumptions. Any educator presenting transformational material must understand the impact of the liminal space and provide pedagogical tools in their courses to support their students as they experience "being on the borderline." This is a sensitive time which requires specific pedagogical methods, such as reflection assignments, to support students in their journey through liminality rather than squashing the potential for ideological transformation.

References

- Batchelor (2012) Borderline space for voice. International Journal of Inclusive Education. 16:5-6, 597-608, https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.655501

- Baglieri, S. (2008). 'I connected': Reflection and biography in teacher learning toward inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(5-6), 585-604. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802377631

- Baglieri, S., Valle, J.V., Connor, D.J., & Gallagher, D.J. (2011). Disability studies in education: The need for a plurality of perspectives on disability. Remedial and Special Education, 32(4), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932510362200

- Baily, S., Stribling S.M., & McGowan, C.L. (2014). Experiencing the "Growing Edge": Transformative teacher education to foster social justice perspectives. Journal of Transformative Education, 12(3), 248-265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344614544373

- Berger, J.G. (2004). Dancing on the threshold of meaning: Recognizing and understanding the growing edge. Journal of Transformative Education, 2(4), 336- 351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344604267697

- Brookfield, S.D. (2012). Critical theory and transformative learning. In Taylor, E.W. & Cranton, P. and Associates (Eds), The Handbook of Transformative Learning, Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Connor, D.J. (2015). Practicing what we teach: The benefits of using disability studies in an inclusion course. In Connor D.J., Valle, J.W., & Hale, C. (Eds.), Practicing Disability Studies in Education: Acting Toward Social Change. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-1446-5

- Connor, D. J., Gabel, S. L., Gallagher, D. J., & Morton, M. (2008). Disability studies and inclusive education — implications for theory, research, and practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(5-6), 441-457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802377482

- Connor, D.J., Valle, J.W., & Hale, C. (2015). Introduction: A brief account of how disability studies in education evolved. In Connor D.J., Valle, J.W., & Hale, C. (Eds.), Practicing Disability Studies in Education: Acting Toward Social Change. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-1446-5

- Creswell, J.W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Cypher, J., & Martin, D. (2008). The mobius strip: Team teachers reflecting on disability studies and critical thinking. Disability Studies Quarterly, 28(4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v28i4.139

- Derby, J. and Karr, V. (2015) A Collaborative Disability Studies-based Undergraduate Art Project at Two Universities. Disability Studies Quarterly. 35(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4643

- Dewsbury, G., Clarke, K., Randall, D., Rouncefield, M., & Sommerville, I. (2004). The anti-social model of disability. Disability & Society. 19(2), 145-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000181776

- Dirkx, J. M. (2001). The power of feelings: Emotion, imagination, and the construction of meaning in adult learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2001, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.9

- Eisenman, L. & Kofke, M. (2016). Questions, Questions: Using Problem-Based Learning to Infuse Disability Studies into an Introductory Secondary Special Education Course. Review of Disability Studies. 12(4).

- Erevelles, N. (2015). Madness and (higher education) administration: Ethical implications of pedagogy using disability studies scholarship. In Connor D.J., Valle, J.W., & Hale, C. (Eds.), Practicing Disability Studies in Education: Acting Toward Social Change. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-1446-5

- Greenstein, A., Blyth, C., Blunt, C., Eardley, C., Frost, L., Hughes, R., Perry, B., Townson, L. (2015) Exploring Partnership Work as a Form of Transformative Education: "You do your yapping and I just add in my stuff". Disability Studies Quarterly. 35(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4653

- Hulgin,K., O'Connor, S., Fitch, E.F., & Gutsell, M. (2011). Disability studies pedagogy. Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 7(3&4), 52-66.

- Jarman, M. & Kafer, A. (2014). Guest editors' introduction: Growing disability studies: politics of access, politics of collaboration. Disability Studies Quarterly. 34(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v34i2.4286

- Kreber, C. (2012). Critical reflection and transformative learning. In Taylor, E.W. & Cranton, P. and Associates (Eds), The Handbook of Transformative Learning, Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Lalvani, P. & Broderick, A. (2013). Institutionalized ableism and the misguided "Disability Awareness Day": Transformative pedagogies for teacher education. Equity & Excellence in Education. 46(4), 468-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2013.838484

- Lower, E., & Driedger, D. (2008). "Before and After," "Self Inventory," and "Self Reflection". Disability Studies Quarterly,28(4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v28i4.141

- Malkki, K. (2010). Building on Mezirow's theory of transformative learning: Theorizing the challenges to reflection. Journal of Transformative Education, 8(1), 46-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344611403315

- Mezirow, J. (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

- Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

- Mezirow, J. (1998). On critical reflection. Adult Education Quarterly, 48, 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171369804800305

- Mezirow, J. (2012). Learning to think like an adult core concepts of transformation theory. In Taylor, E.W. & Cranton, P. and Associates (Eds), The Handbook of Transformative Learning, Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

- Paterson, J., Hogan, J., and Willis, H. (2008). Vision, Passion, Action: Reflections on Learning to do Disability Studies in the Classroom and Beyond. Disability Studies Quarterly,28(4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v28i4.138

- Pearson, H., Cosier, M., Kim J.J., Gomes, A.M. Hines, C., McKee, A.A., & Ruiz, L.Z. (2016). The impact of disability studies curriculum on education professionals' perspectives and practice: Implications for education, social justice, and social change. Disability Studies Quarterly, 36(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v36i2.4406

- Picower, B. (2013). You can't change what you don't see. Journal of Transformative Education.11(3), 170-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344613502395

- Selznick, H. (2015) Investigating Students' Reception and Production of Normalizing Discourses in a Disability-Themed Advanced Composition Course. Disability Studies Quarterly. 35(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4626

- Slesaransky-Poe, G., and Garcia, A.M. (2014). The social construction of difference. In Lawrence-Brown, D. & Sapon-Shevin, M. (Eds.), Condition Critical: Key Principles for Equitable and Inclusive Education. Teachers College Press.

- Snyder, C. (2008). Grabbing hold of a moving target: Identifying and measuring the transformative learning process. Journal of Transformative Education. 6(3), 159- 181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344608327813

- Vidali, A., Price, M., & Lewiecki-Wilson, C. (2008). Disability studies in the undergraduate classroom. Disability Studies Quarterly, 28(4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v28i4.137

- Ware, L. (2013) Special Education Teacher Preparation: Growing Disability Studies in the Absence of Resistance. In Wilgus, G. (Ed). Knowledge, pedagogy, and postmulticulturalism: shifting the locus of learning in urban teacher education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137275905_8

| Topic | Reading Response Prompt samples | Learning Response Prompt samples | Assigned Readings | Class Activity samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disability History/ Overview of DS concepts |

|

In what ways do the various positions on "person-first" language reflect our society's evolving perspectives on disability? |

|

Lives worth Living video |

| Education |

|

|

|

Relevant Presentations |

| Employment |

|

|

|

|

| CRPD | No RR this unit |

|

|

Relevant Presentations |

| Health Care |

|

|

|

Relevant Presentations |

| Community- Living |

|

|

|

Relevant Presentations |

| Relationships |

|

|

|

|