Disability theorists have long-argued that social norms related to gender, sexuality, and disability co-construct one another (Kafer, 2013; McRuer, 2011). In response, leading disability studies journals frequently consider the importance of gender and sexuality in the lives of people with disabilities (e.g., Albertz & Lewieck-Wilson, 2008; O'Toole, 2002; Robillard, & Fichten, 1983; Samuels, 2013; Tepper, 1999). However, only a few studies have explored these same issues in the lives of college students with disabilities (e.g, Henry, Fuerth, & Figliozzi, 2010; Miller, 2015). That represents a critical gap in the literature at a time when students with disabilities represent one of the fastest growing segments of the college-going population (Higher Education Research Institute, 2011; Snyder & Dillow, 2013). Available research has shown that college students with disabilities face pervasive stigma and chilly campus climates (Trammell, 2009). Yet, few studies use empirical findings to theorize disability as an intersectional category of identity that is co-constructed with other social identities such as gender and sexuality (Vaccaro, Kimball, Ostiguy, & Wells, 2015). As such, they may fail to note the interplay of overlapping and mutually reinforcing systems of oppression in the lives of students with disabilities.

In the absence of empirical information about how students with disabilities make meaning of their sexuality and gender, researchers and educators may inadvertently reduce the experiences of people with disabilities to their disabilities alone and/or rely on potentially deleterious implicit theories in their work with students (c.f., Milligan, & Neufeldt, 2001; Kimball, Vaccaro, & Vargas, 2016). To begin to address this issue, this paper uses data from a constructivist grounded theory study that delved deeply into gender and sexuality concepts, identities, and enactments expressed by college students with disabilities who have minoritized gender and/or sexual identities. Following the convention of queer theorists, we label these identities "queer" even though not all participants did or would describe themselves in this way (e.g, Edelman, 2004; Muñoz, 1999). These minoritized gender and sexual identities are "queer" because they transgress against oppressive social norms and assumptions that privilege cisgender, heterosexual identities. Our goal is to disrupt the present state of knowledge regarding the intersections of gender, sexuality, and disability using critical inquiry (c.f., Carducci, Kuntz, Gildersleeve, & Pasque, 2011; Renn, 2010).

Literature Review

Consistent with the tenets of Charmaz's (2014) constructivist approach to grounded theory, we utilized two sensitizing constructs to integrate relevant empirical and theoretical literature into our research process: 1) empirical literature related to the intersections of gender, sexuality, and disability in the lives of college students; and 2) theoretical work by queer and crip theorists who seek to understand the role of ableism, heterosexism, and cisgender privilege in constructions and experiences of identity.

Intersections of Gender, Sexuality, & Disability

Intersectionality is an oft-used term in academic and activist settings. Yet, scholars conceptualize and apply intersectionality in a variety of ways (Abes & Kasch, 2007; Hancock, 2016; Hill-Collins & Bilge, 2016; Shields, 2008). Early work that anticipated intersectional scholarship was produced by a group of Black feminists who explicated the difficulty of separating "race from class from sex oppression because in our lives they are most often experienced simultaneously" (Combahee River Collective, 1977/1995, p. 234). Since then, many writers—especially women of color—have discussed intersectionality in the context of the effects of multiple minoritized identities of race, gender and class (Crenshaw, 1989; Hill Collins, 1991; hooks, 2000; Wing, 2003). Shields (2008) described intersectionality as the way intersecting social identities such as race, gender, class, and sexuality are "organizing features of social relations, mutually constitute, reinforce, and naturalize one another" (p. 302). Most of these scholars view intersectionality is an invaluable analytic tool for critically analyzing the way that pervasive oppressive structures reinforce one another and lead to unique lived experiences for people with multiple and interconnected social identities (Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016).

In this study, we began our intersectional analysis from the perspective of queer theory, which Abes and Kasch (2007) have argued is an inherently intersectional framework. We follow this logic in applying an intersectional, queer theoretical lens to the experiences of students with disabilities. Despite the importance of both intersectionality and queer theoretical perspectives, they have rarely been adopted in studies of college students with disabilities. The empirical literature on the experience of college students with disabilities is both scant (Kimball, Wells, Ostiguy, Manly, & Lauterbach, 2016; Peña, 2014) and pays little attention to issues related to their gender and sexual identities (Patton, Renn, Guido, & Quaye, 2016). In fact, Student Development in College, the key textbook used for training higher education administrators, made it to its third edition before devoting a full chapter to disability identity development (Patton et al., 2016). That chapter covers four models of disability identity that Patton and colleagues (2016) argue have broad utility for higher education administrators. Two of these models focus on disability generally (Gibson, 2006; Johnstone, 2004) and two focus specifically on college students (Davidson & Henderson, 2010; Forber-Pratt & Aragon, 2013). However, these models are: rarely used in research on students with disabilities (Kimball et al., 2016c); seldom used by higher education administrators (Kimball et al., 2016b); and not intersectional approaches to disability.

Strong empirical evidence also supports the intersectional approach to disability—even if supported by only a limited number of college-specific studies (e.g., Henry et al., 2010; Miller, 2015). A recent study of identity salience indicated that visible disabilities represent a superordinate form of identity relative to other common social identity markers such as gender and ethnicity (Rohmer & Louvet, 2009). Notably, however, this finding is not consistent across disability diagnoses—with people with learning disabilities and other invisible disabilities sometimes being seen as having less legitimate forms of disability identities (McDonald, Keys, & Balcazar, 2007). Studies have also shown that the gender experiences of people with disabilities are inextricable from their experiences of disability (McDonald et al., 2007; Peuravaara, 2013). Likewise, both gender and sexuality intersect with disability in the perceptions of both self and others (e.g., Helmius, 1999; Tepper, 1999). For example, studies have shown that disability has a profound impact on the dating and romantic partnerships of college students with disabilities (e.g., Goldstein & Johnson, 1997; Robillard & Fichten, 1983). In part, these experiences stem from a pervasive set of social assumptions that treat all people with disabilities as asexual whether they so identify or not (c.f., Kim, 2011; Milligan & Neufeldt, 2001). In response, scholars in both college student development and disability studies have called for increased attention to the intersections of gender and sexuality for people with disabilities (Fraley & Mona, & Theodore, 2007; Harley, Nowak, Gassaway, & Savage, 2002). Yet, very little empirical work has been published in response to this call.

Queer & Crip Theory

While literature on the intersections of disability, gender, and sexuality in the lives of college students is limited, empirical work has highlighted the way in which students with disabilities actively shape their own identities and the world in positive ways through their activism, self-styling, self-advocacy, and storytelling (e.g., Kimball, Moore, Vaccaro, Troiano, & Newman, 2016; Pasque & Vargas, 2015). Likewise, queer and crip theorists focus on the construction of identity within and against ideological systems that give rise to feelings of alterity (Kafer, 2013; Renn, 2011). They also argue that the systems of oppression supporting societal understandings of gender, sexuality, and disability exert interlocking effects that can amplify one another. In other words, gender, sexuality, and disability must all be thought of as intersectional in nature (c.f., McRuer, 2006; Moser, 2006). Queer and crip theories extend these notions further.

Critical queer theory focuses on both sexuality and gender identity in order to derive five key insights about the underlying structure of society. First, queer theorists have demonstrated that the idea of queerness is a necessary precondition of the idea of heterosexuality (Muñoz, 1999). Second, queer theory suggests that, since heterosexuality has been systematically reinforced as normative, queerness is seen as abnormal (Edelman, 2004). Third, queer theorists have shown that the social definition of heterosexuality is predicated on an understanding of gender as binary and fixed (Butler, 1990). Fourth, queer theory holds that, within this gender binary, men hold privileged gender identities relative to women, and anyone who is not cisgender is marginalized still further (Butler, 2004). Finally, queer theorists believe that these assumptions are so fundamental to the way that society has been organized that heterosexuality and patriarchy effectively become compulsory, and those who do not conform are punished via enforcement mechanisms such as stigma, covert economic penalties, and law enforcement actions (Foucault, 1978). Crip theory, a critical disability perspective, extends these five tenets of queer theory by suggesting that sexuality and disability have always been related to one another in medical thought and social action (Kafer, 2013).

Crip theorists argue that ablebodiedness also serves as a compulsory force in society and effectively serves to reinforce (and be reinforced by) compulsory heterosexuality (McRuer, 2006). By suggesting the normative nature of both ablebodiedness and heterosexuality, society has been structured—and people have been taught to—treat difference as problematic (McRuer, 2011). In the context of interlocking systems of structural oppression, critical queer theory and crip theories highlight the importance of acknowledging non-dominant identities that allow for transgression: the queer and the crip. Both terms serve as discursive spaces rather than a fixed identity based on a particular sexuality, gender, or disability status. The queer and the crip can be constructed many ways, but they are often built using signs and symbols appropriated from a society that does not value these identities, but are repurposed to fit the self-styling of those who (re)claim them (Muñoz, 1999). In response to this idea, we utilized these empirical and theoretical insights to explore the way in which students with disabilities represent their broader sense of self through the concepts, identities, and enactments they use to express their sexualities and gender identities.

Methods

The data for this study were generated from a constructivist grounded theory study (Charmaz, 2014). As higher education disability scholars, we are interested in understanding the experiences of college students with disabilities. In this project, we sought to address the following research question: How do college students with disabilities describe their process of developing a sense of purpose? A secondary research question within this broader study asked: How salient are students' social identities as they develop purpose? As we delved into our secondary research question, we began to see particular patterns of responses among 12 of our 59 participants with disabilities who also self-identified as having minoritized sexual or gender identities. We describe these minoritized social identities as "queer" in recognition of the fact that our participants developed these identities in opposition to oppressive ideological and social structures (e.g, Edelman, 2004; Muñoz, 1999). As a focused response to our second research question, this paper does not delve deeply into purpose per se, which we address elsewhere (Vaccaro, Kimball, Newman, Moore, & Troiano, 2018). Instead, we focus on student narratives and offer theoretical propositions about the developmental processes students with disabilities implemented as they attempted to articulate queer gender and sexual identities.

For the study, we used theoretical sampling (Charmaz, 2014) to find a diverse pool of participants. Theoretical sampling is a form of purposive sampling, which seeks to identify participants who can best illuminate the phenomenon under study rather than using probabilistic methods. In this case, the theoretic sampling sought to garner participants who identified as college students with disabilities; who had diverse majors, class years, and other social identities (e.g., gender, class, sexuality); and who were willing to share their perspectives on purpose development. Recruitment primarily took place via disability services offices at multiple higher education institutions. Fifty-nine participants from three public and one private historically White universities in the Northeast comprised our final sample. Once students volunteered for the study, they were scheduled for an individual interview. Before beginning the interview, we asked students to complete consent and demographic forms. The demographic form asked students to report their disability, age, gender, race, and sexual orientation. We offered a number of closed-ended options for gender (i.e., woman, man, transgender, genderqueer) and sexuality (i.e., heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer, questioning). Participants were instructed to select all that applied. We also provided a category called "Not listed: (please explain)" where students could describe themselves using their own words. Since it was the primary focus of our study and there is little agreement about meaningful disability categories (Vaccaro, Kimball, Ostiguy, & Wells, 2015), the demographic form also included a blank space for students to "describe your disability." Table 1 provides a demographic summary of the subset of 12 participants described in this paper.

| Pseudonym | Pronouns* | Age | Year | Major | Disability | Gender | Sexuality | Race |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aricelli | she/ her | 28 | Junior | Italian | Bipolar Disorder II (Time 2: Bipolar disorder 1, borderline personality disorder, ADHD inattentive type) | Woman | Lesbian | Bi/Multi-Racial |

| Cal | Not reported | 19 | First Year | Math | Asperger's Syndrome, Anxiety | Man | Questioning | White |

| Erin | she/ her | 22 | Senior | Nursing | Dyslexia, Dyscalculia | Woman | Lesbian | White |

| Isaiah | he/ him | 20 | Sophomore | Chemical Engineering | ADD, history of concussions | Man | Rejects labels | White |

| Justice | they/ them | 23 | Senior | Biology | Depression and anxiety; not-yet diagnosed chronic illness (possibly Addision's disease)** | Man, Transgender | Asexual & Aromantic | White |

| Layla | she/ her | 28 | Graduate Student | Textiles (historic) | Chronic Migraines | Woman | Queer | White |

| Liza | she/ her | 20 | Junior | Psychology | Depression, Anxiety | Woman | Pansexual | White |

| Poppy | Not reported | 21 | Sophomore | Psychology | Profound deafness in right ear | Woman | Heterosexual; Rejects labels | White |

| Reyna | Not reported | 19 | First Year | Animal Science | Cerebral Palsy | Woman | Lesbian | White |

| River | it/ that | 31 | Class of 2013 | Studio Art | Autism Spectrum | Man | Questioning | White |

| Willow | Not reported | 20 | Sophomore | Biomedical Engineering | Dyslexia, reading comprehension | Woman | Bisexual | White |

| Yolanda | they/ them | 22 | Senior/ Grad Student | Math/ Mechanical Engineering | Autism and other related, hypermobile | Gender-queer | Queer | White |

| * As noted in our limitations section, our original demographics form did not include a space for participants to report pronouns. While we asked each participant to supply pronouns retrospectively, imperfect contact information meant that some did not respond. ** While not listed on their demographics form, Justice described themself as on the autism spectrum during the interview and related that a medical professional had previously indicated that they might have Asperger's Syndrome, though no formal diagnosis was ever made. | ||||||||

This demographic table shows that participants included: seven women, four men (one of whom reported that they were transgender), and one genderqueer person. Participants also include three lesbians, two people who reported rejecting labels, two queer-identified people, two people who reported questioning their sexuality, one bisexual person, one pansexual person, and one asexual and aromantic person. Participant ages ranged from 19-31 and their academic standings included two first year students, three sophomores, two juniors, two seniors, one senior / graduate student, one graduate student, and one recent graduate. Participant majors included seven people majoring in a science, technology, engineering, or mathematics field; three people majors in the arts or humanities; and two people majoring in the social sciences. One participant identified as multiracial and the remainder were white. Information regarding disability status, as well as any demographic information directly relevant to interpretation, is provided in the findings section as each participant is introduced.

Throughout the study, we used constant comparative analysis to move back and forth between collection, analysis, and theory building. Our interview protocol included questions about the ways multiple social identities shaped student meaning-making processes and sense of self. We audio-recorded the 60-120 minute interviews, transcribed them verbatim, and then subjected them to grounded theory open coding (Charmaz, 2014). All transcripts were coded by at least two members of the research team and confirmed by at least two others. Following our primary coding process, we conducted focused coding to sort and categorize important emergent themes. Charmaz (2014) explained how focused coding allows researchers to honor emergent themes and affords them an opportunity to follow the data in "unanticipated, but exciting directions" (p. 140). This was certainly the case with our project where we followed up on emergent concepts regarding the ways students with disabilities expressed their sense of self through unique gender and sexual perspectives, identities, and enactments. Charmaz (2014) argued: "After you have established some strong analytic directions … you can begin focused coding to synthesize, analyze, and conceptualize larger segments of data" (p. 138). In our case, these larger segments of data included responses about gender and sexuality from a sub-sample of 12 students with disabilities who identified as having a queer gender and/or sexuality. To enhance theorizing during our constant comparative process, we conducted follow-up interviews. For the sub-set of 12 students described in this paper, nine completed a second interview. During the theorizing stages of the constant comparative process, we found queer theory to be a useful "sensitizing concept" (Charmaz, 2014, p. 30) that moved us toward our four theoretical propositions and a visual heuristic (See discussion of Figure 1 in Theoretical Proposition 4).

To enhance trustworthiness and credibility, we used a number of strategies including: analytic triangulation; member checking through follow-up interviews and email inquiries; discrepant case analysis; and peer reviews from disability scholars and students (Jones, Torres, & Arminio, 2014). We also addressed relational competence through reflexivity about our social identities, positionality, power relationships, and pre-understandings (Charmaz, 2014; Jones et al., 2014). The team included researchers with and without disabilities who represented a spectrum of genders and sexualities. We challenged each other to recognize how our identities and perspectives shaped our research as we sought to produce scholarship that challenged power and privilege and exposed the ways development is shaped by inequitable social contexts.

Limitations

On our demographic form, we asked students to report their social identities, but we did not ask students about their pronoun usage. To address this limitation, we followed up with students via email and asked them which pronouns they used. In the findings, we only use pronouns for students who responded to this inquiry. Unfortunately, avoiding pronouns in some vignettes resulted in an overuse of pseudonyms and passive voice.

Another limitation is that our analysis aggregates widely divergent identities into the overall ideas of queerness and disability. Indeed, although all the participants represented in this paper have identities that both queer and crip theories seek to explain, not all of them would identify as "queer" or as having a "disability." Simply put, although we have grouped these participants' accounts together for strong theoretical reasons, the way that they self-identify and experience the world varies dramatically. Similarly, we must note that it is difficult to write with nuance about gender and sexuality separately because they are co-constitutive of one another (Shields, 2008). However, we also need to make clear that gender and sexuality should not be conflated. Although queer theory suggests that society is structured otherwise, we do not believe that knowing someone's present understanding of their gender allows us to make assumptions about their present understanding of their sexuality or vice-versa.

A third limitation relates to the racial identities of our participants. All but one self-identified as white. The lack of people of color in our sample restricted our ability to attend to systematically address potential racial variations in experience from an intersectional perspective. However, this limitation also reflects the fact that, white students with disabilities are far more likely pursue a postsecondary degree than students of color with disabilities (NCES, 2016). The suppressed educational trajectories of students of color with disabilities warrants further investigation, which we are unable to undertake in this study.

Findings

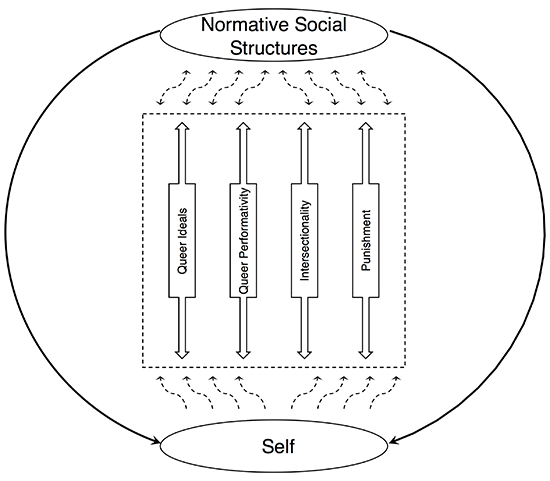

Instead of artificially chopping student narratives into categories or themes (the norm for qualitative studies), we present extended vignettes from 12 students with disabilities to capture the ways they thought about, made meaning of, and performed gender and sexuality. Charmaz (2014) contends "For grounded theorists, a story does not stand on its own" (p. 317). As such, we offer brief analyses of student narratives in the context of four queer continua which are portrayed in Figure 1. First, students expressed understanding and adoption of a range of queer ideals. This continuum involved the range of participant rejection-to-acceptance of restrictive gender and sexual norms, binaries, and labels. The continuum of queer ideals ranged from queer perspectives that were purely abstract (e.g., something I read about in class) to highly personalized (e.g., something I apply to my life). A second continuum was queer performativity which reflected the heterogeneous ways students enacted queer ideals in their language and behavior. The third continuum represented the range of student understandings of, and concerns about, receiving punishment (Foucault, 1978) for enacting queer ideals and engaging in queer performativity. Crip theorists argue that ablebodiedness is a compulsory force in society and reinforces compulsory heterosexuality (McRuer, 2006). As such, we paid attention to the ways students talked about the overlaps, similarities, and differences among their sexual, gender, and disability identities. Thus, the fourth continuum, called intersectionality, portrays variations in student propensity to adopt queer ideals, engage in queer performativity, and acknowledge punishments in relation to their single and/or intersecting gender, sexual, and disability identities.

We could have ordered the 12 vignettes by categorizing students in a variety of ways (e.g., alpha order, disability type, gender identity, sexual identity). Instead, we chose to begin with students whose prose focused more in the intersections of multiple identities, including their disability. This choice reinforces our conclusion that student reflections about intersectionality exist on a continuum. Some students reflected deeply on the intersections of two or more social identities (early vignettes) while other students discussed only one identity at a time and/or refused to discuss some identities at all (later vignettes). Notably, since our analysis utilizes a critical, intersectional approach, some of our discussion of participant findings may seem to problematize participant beliefs or behaviors. That is not our intention; instead, we are interested in explicating the way that students with disabilities made meaning of their gender and sexual identities in order to highlight the systems of oppression within which they are constructed. Regardless of where students fell on the intersectional continua, we wish to acknowledge that they were all actively engaged in developmental processes—albeit at different points—to define themselves relative to or in opposition from these oppressive belief structures.

Yolanda

On our demographic form, Yolanda wrote "autistic (pile of things you could argue either are a part of autism or not), hypermobile." Yolanda attempted to enact queer ideals and engage in queer performativity by selecting "they/them/theirs" as gender pronouns. Moreover, Yolanda's word choice and tone of voice during the interviews conveyed irritation with labels and restrictive and binary images of sexuality. Yet, Yolanda also used three categorical labels (versus a spectrum) when describing their attraction.

I've liked guys. I've liked girls. I've liked non-binary people, but I tend to not like any of the above all that often. And romantic stuff aside, I'm totally asexual. I think queer is the best word for that. Most of the time because of the not sexual attraction, not sex drive thing, it's not registering all that high on my to-do list. But, if I need to give it a label, queer is what I'm going for because not much else makes sense … I think my asexuality actually does relate to my autism, because I have sensory processing issues … None of the neuro-typical gender definitions make particularly much sense to me. So, it's like here is a definition of what it is to be a man. I don't think that matches [me]. Here is a definition of what it is to be a woman. No!

Yolanda alluded to intersectionality when describing difficulty processing normative gender messages because of their autism. The way their brain processes emotions and information—including hegemonic messages about gender and sexuality—illuminates the mutually reinforcing nature of ideological systems within an intersectional framework (Shields, 2008). Yolanda also described a desire to engage in queer performativity by resisting ill-fitting "neuro-typical" labels. The simple exclamation of "No!" and selection of "gender-queer" on our demographic form suggests Yolanda was attempting to enact queer ideals by performing queerness in everyday life with little regard for potential punishment.

Liza

Liza, who identified as having "depression and anxiety" on the demographic form and revealed she was experiencing PTSD in the interview, struggled to engage in queer performativity as she navigated limiting societal messages about her intersecting gender, sexual, and disability identities.

With sexual orientation I identify as pansexual … Most people don't really know [what that means], so I just say I'm bisexual … It's a part of me. It's not who I am … In some ways, [gender is] more prominent because I'm mentally ill and I'm a female, and those two things just kind of tend to be put together, and … Especially with the PTSD, I already feel weak, but then I feel defenseless.

Liza's choice to "just say bisexual" shows an unwillingness to perform sexuality in a manner that aligned with her internal sense of self and queer ideal of resisting binaries. The quote also highlights Liza's fear of being misunderstood—which could be experienced as a form of punishment. However, Liza's quote also reveals her deep reflection on intersectionality, which has been described as the process by which various social identities "mutually constitute, reinforce, and naturalize one another" (Shields, 2008, p. 302). She could not fully express her disability, gender, or sexuality without also describing her other identities. Liza also alluded to the fact that her intersecting social identities were simultaneously subject to oppressive stereotypes about weakness and defenselessness. Prior literature has discussed these intersecting stereotypes primarily through the lens of visible disabilities (Kafer, 2013). However, Liza's quote demonstrates that invisible disabilities (McDonald et al., 2007)—such as depression—can powerfully influence a person's meaning making because they can be so deeply intertwined with other visible and oppressed identities such as gender.

Layla

Layla, who experienced chronic migraines, preferred the term pansexual because it captured the spectrum of attraction versus a binary. She also enacted queer ideals through queer performativity (e.g., resistance) by pointing out that our demographic form was not inclusive because it lacked a closed-ended option for pansexual.

People generally look at me and assume that I must be hetero, especially because I'm married to a guy. I'm really, really not hetero. I prefer pansexual. I know that's not an option on there [student is pointing to the demographic form] … I have been attracted to and been with people who defied the gender binary. So I don't really care if you're male, female, something in between, transsexual, whatever.

Layla described individuals other than male and female as "in between"—suggesting a classification of gender into three categories versus a spectrum. She may have wanted to adopt queer ideals by rejecting strict binaries, but Layla did not completely avoid categorizing people into three labels. Her comment "transsexual, whatever" could also be viewed as somewhat dismissive and exclusionary of gender-nonconforming people—a striking contrast to her queer performance of queer ideals when challenging the researchers about the exclusion of a pansexual category on our demographic form.

Oppressive disability and gender messaging shaped the way others viewed and interpreted Layla's performance as a person with intersecting gender and disability identities.

As a small, white female [with a disability], people are sometimes pre-inclined to be sympathetic towards me, or, conversely, they have sometimes been pre-inclined to view me as sort of whiny and having a victim complex … I do find gender to be sort of a strong part of my sense of self, but … I think I've mined that one for all that I can at this time.

Similar to Liza, oppressive notions of weakness or sympathy deserving statuses of women and people with disabilities were strong influences on Layla's intersectional sense of self. Because Layla was done "mining" the topic of gender, the interviewer did not ask further questions. As such, it is hard to know if, and how, she made further meaning of intersectionality and the extent to which restrictive labels (e.g., "female" with a "whiny" "victim complex") shaped her understanding of other social identities as well.

Justice

On our demographic form, Justice listed the following in response to the disability question: "depression and anxiety; not-yet diagnosed chronic illness (possibly Addison's disease)." During the first interview, Justice said "I had somebody who attempted to diagnose me with Asperger's Syndrome" and in the second interview, Justice claimed the identity saying "that I [am] on the autism spectrum." Like disability identity, Justice's sexuality journey was an ongoing process. Ruminations about gender became less frequent as Justice became more confident performing and embodying a trans identity.

As I was first sorting out exactly what I identified as, and how I wanted to, like, act on that, [gender] was a really big part of my identity … After I came out as trans … I don't think that much about my own gender, because … like now it matches how I feel, and so now I don't really have to think about it all that much … . I've come out as like every sexual orientation in existence at some point or another in my life … I had had a crush on a boy, and then had a crush on my best friend, who was a girl, and so I just kind of decided, okay, that must mean that I'm bisexual. Problem solved … [Then] for about a year and a half, I identified as a lesbian, until I came out as trans … And so that was also around the time that I discovered the word pansexual [and] continued identifying as pansexual until, like, last year, at which point I started tossing around various assorted identities on the asexual spectrum … Depending on how I'm feeling at the moment, and who is asking me, and under what circumstances—sometimes I'll answer that I'm asexual, and sometimes I'll answer that I'm demi-sexual, and sometimes I'll answer that I'm gray-asexual … This is a work in progress.

Justice expressed a desire to live queer ideals and engage in queer performativity by breaking free of restrictive binaries. Yet, the narrative shows achievement of these goals was somewhat hindered by societal pressure to adopt limiting sexual identity labels (lesbian, bisexual, pansexual) earlier in life. At the end of the interview, Justice suggests a rejection of binaries by leaning toward "the gray-asexual part of the spectrum"—a term created in an effort to find a descriptor that felt right.

Intersectionality of gender and sexuality is apparent in the prior quote as sexuality became "more clear" only after Justice "came out as trans." Later in the interview, Justice also explicated intersectionality between gender and disability.

So for gender, I think one of the hardest areas is that the autoimmune illnesses are almost entirely a phenomenon that people with XX chromosomes get, because there's a genetic component to them, and they're just a lot more likely in people who have two X chromosomes. And so in a lot of chronic illness support communities … everyone is a girl … Like I can count on one hand the number of cisgender guys I have met in my entire time associating with the chronic illness community online. And probably I can count on both hands the number of guys in general, trans or cis that I've encountered. So like almost everybody that I talk to about chronic illness stuff identifies as a woman. And so it's really hard to like get support and talk about the things I'm going through, because a lot of times we'll be talking about self-care, or how to be a young person with a chronic illness, and they'll be like: "Oh, well, sometimes I like to paint my nails for self-care." And it's like, I don't paint my nails, I don't really like to paint my nails … The only time I paint my nails is when I'm working with small children and one of the boys is like, "I want to paint my nails, but it's embarrassing, because I'm a boy." So then I'll come in with my nails painted [laughs]. Or they'll be like, "Oh, well, here are some fun craft ideas to decorate your mobility aids." And I'll be like, "I don't want to tie pink ribbons on my cane. Like, does anybody have any recommendations for like nerdy stickers that you can stick on your cane that won't wash off with the rain?" And so it's tricky to relate to a lot of the conversations that happen.

In this quote, Justice engaged in queer performativity to educate young boys about queer ideals—challenging restrictive gender norms that suggest boys should not wear nail polish. While Justice does not typically choose to express themself by wearing nail polish, Justice risked punishment to challenge restrictive notions about "appropriate" gender expressions in order to teach young boys that believing in and enacting queer ideals was ok. While Justice did not necessarily talk about intersectionality of all three identities (gender, sexuality, disability) in the prior quotes, Justice spoke quite eloquently about the interconnections between gender and sexuality when they detailed the limits of available sexual identity terms (e.g., lesbian) which were inherently tied to their evolving gender identity. They also explicated the intersections of gender and disability when discussing the gendered nature of chronic illness communities and their corresponding inability to find support that honored these deeply intersecting identities.

River

River self-identified as a person on the autism spectrum. When asked about sexual identity, River expressed quite a bit of discomfort about relating to people and having "urges" (not explained during the interview). Because of obvious discomfort, the interviewer did not ask probing questions.

Well it's just that, as life went on, I related to less people around me. I wondered, why like this thing (penis) that's attached to my body. Why should this influence my identity at all? It doesn't … So I, I became a non-entity, as far as, obviously I have physical matter (genitals), but I don't have any, certain meanings.

Here, River expresses queer ideals by pushing back on restrictive notions of sexuality and gender that equated genitals with assumed gender, sexual identity, and appropriate partners. On the demographic sheet, River did not want to be "either gender" which suggests an adoption of a binary perspective. However, in a follow up email about pronouns, River expressed the desire to reject labels and engage in queer performativity by adopting the pronouns "it" and "that." The following interview response suggests an adoption of queer ideals through rejection of normative societal messages about what River's gender and sexuality should mean.

Society says you can do whatever you want—You can be the other one (gender) now. But I don't want to be the other one. I don't want to spend money I don't have mangling my body and hormones, or whatever, messing up my mind just to become somebody else's [idea of what is acceptable] … From my experience, people who do that—they have [gender confirmation] surgery— it's not convincing … If I did that … I would think I look like a clown.

Queer ideals, performativity, punishment, and intersectionality all appear in this quote. We contend the "clown" comment reflected a desire not to perform according to others expectations and also a reference to possible punishment (e.g., disapproval, judgment) if River undertook gender confirmation surgery. Intersectionality can be seen in the way that River's literalness, a common trait among those on the autism spectrum, influenced the belief that gender confirmation surgery is "not convincing." There also seems to be a disconnect between River's queer ideals and vocabulary for describing queer performativity. For instance, River's vocabulary could unintentionally replicate oppressive norms (implying trans* people look like clowns) even while River attempted to enact queer ideals by rejecting restrictive norms and selecting "it" and "that" pronouns (e.g., queer performativity). This disconnect between intention and impact reflects the complex developmental nature of understandings of gender and sexuality.

Cal

Cal self-identified as having Asperger's Syndrome and anxiety. Cal expressed very few queer ideals during the interview and did not seem concerned about binaries or labels. Cal did, however, seem embarrassed (and possibly concerned about punishment) after engaging in what could be seen as queer performativity (or at least non-normative conversational behavior) (i.e., blurting out the word penis during the interview). Cal said: "I'm male, I feel male, but … I think about feminism a lot … And how the patriarchal forms are sort of pernicious. Too many Ps there. Penis. Good grief. I'm sorry." After ending the conversation about gender with that apology, the interview moved to the topic of sexuality.

I think about sexuality and I have sort of strange ways of going about my preferences … I have fantasies. I'm not really attracted to people, in the real world and I find the idea of seeking out a romantic, potentially sexual relationship, to be a bit scary in the sense that I probably, that it would be something that I had to work to maintain at. That would be a bit overwhelming that I couldn't just go about life only for myself, but I'd have to consider some other person too and that sort of thing. I'm a virgin, but regards to pornography, I only like ever consume cartoon pornography. I don't ever seek out videos and stuff, it's always drawn by people on the internet and it extends the full range. I am bisexual in my choice of pornography.

In this passage, Cal's clear description of fantasies can be seen as a powerful articulation of queer ideals and enactment of queer performativity. Cal's statement regarding the prospect of seeking a "romantic, potentially sexual relationship" being "a bit scary" reflects the possible intersection of sexuality and disability. Prior research has suggested that fostering intimate relationships involves giving and receiving complex social cues—an often difficult task for students on the autism spectrum (DeVries, Noens, Cohen-Kettenis, van Berckelaer-Onnes, & Doreleijers, 2010; Jacobs, Rachlin, Erickson-Schroth, & Janssen, 2014). Cal's fear over the potential transgression of the mostly implicit rules shaping intimate relationships highlights the extent to which thinking about punishment may actually lead to self-regulation or the internalization of stigma (Foucault, 1978; Butler, 1990). This potential fear of punishment stands in marked contrast to the openness with which Cal shared information about the consumption of cartoon pornography in an interview context.

Aricelli

On our open-ended demographic form, Aricelli listed her disabilities as follows: "bipolar disorder 1, borderline personality disorder, ADHD inattentive type." Compulsory heterosexuality was an ever-present reality in Aricelli's household. During the interview, she admitted she would rather avoid family than suffer potential punishments associated with violating compulsory heterosexuality (Foucault, 1978).

There was this girl I was dating … I had considered having her come over, just introducing her as a friend, not as a partner, eventually didn't end up happening. She is very much that stereotypical lesbian that I don't fall into … I texted my mom from work. I just wanted to throw it out there that the girl who would be coming over is gay, and I know it's your house and if you have an issue with that let me know now so we can cancel everything.

Aricelli went on to elaborate that any discussion of her sexuality or the people whom she dates is a "closed topic"—that is, one about which her parents refuse to have a conversation. Notably, Aricelli describes a similarly pattern of non-communication around her disability, which she described as having been identified after high school. However, her interview does not make clear why, in contrast to most other participant narratives, her parents do not figure prominently in her discussion of issues arising from her disability.

During a follow-up interview, Aricelli expressed queer ideals about sexuality and gender and performed these ideals by critiquing our demographic form. In the margins of the form (See Methods), she wrote "while neither apply to me, I applaud and appreciate the inclusion of 'atypical' extended choices for gender and sexuality. Great job." Aricelli's use of the word "atypical" in quotation marks also suggests an understanding (and dislike) of social messaging that produces and reinforces binaries of gender and sexuality. Likewise, her desire to express fully her disability status by combining and fully describing the impact of her multiple diagnoses reflects an understanding that disability is inherently difficult to categorize. After trying to confirm to oppressive ideologies about who she should be earlier in life, Aricelli now wants to enact queer ideals by challenging oppressive notions (e.g., queer performativity) as a parent.

Growing up [gender binaries] didn't bother me, I just thought that's how it was. But as I got older, I was like: "What the hell?" I try to keep things open, even though she's so young. She has blue onesies with cars and she sports a blue bow with them. Unless it specifically says stuff like: "mommy's little dude"—obviously she's a girl. I try to get things that are all different colors and all different styles and she doesn't just have the fluffy pink stuff. I think it's a good foundation to start with that she gets used to the fact that that's not a boy thing and a girl thing, it's all for everybody. In that regard it's easier to have a girl, because I couldn't put a boy in pink and justify it with other people who don't understand.

Despite a desire to adopt queer ideals (e.g., reject gender limitations), Aricelli actually used binary labels and gender normative language during the interview (e,g., blue, pink). She also seemed to draw the line at challenging restrictive gendered messaging (and potential punishments) by not selecting clothes that said "mommy's little dude" because "obviously she's a girl." Aricelli intended to socialize "good foundation[s]" by resisting gender binaries. She may have been attempting to blur gender binaries. Another possibility is that Aricelli performed gender policing (e,g., putting a blue bow on the child to ensure the blue outfit was not misunderstood). Given the tone and delivery of her interview, researchers understood her comments to suggest Aricelli was unprepared to challenge some restrictive norms (or navigating subsequent punishments) if her child had been a "boy" dressed in "pink." In essence, while Aricelli described a desire to embody queer ideals by performing queerness in parenting, her language and actions suggest she sometimes fell short of fully enacting liberating queer ideals. Although Aricelli did not address fear of possible punishments directly in her interview, the gap between Aricelli's queer ideals and performance of queerness arguably reflects a concern about the possibility of punishment, the basis for which can be seen in her early experiences of compulsory heterosexuality and gender performance expectations.

Erin

Erin identified as a student with dyslexia and dyscalculia. She exhibited queer ideals by challenging heterosexism and stigma, describing herself as "gay," and refusing to be defined by dating partners. Erin said:

I mean I'm gay and proud, but … I think you shouldn't be defined by your sexual orientation. And, I don't think you should be stigmatized by your sexual orientation, but it still happens. It's like: "Okay, yes, I'm gay. Congratulations. You want a trophy? You know a gay person. Have a cookie." [Laughs] … The need to defend yourself … So, I guess that's when it became an identity for me 'cause I'm not ashamed of the fact that I'm gay … If you're asking me about politics, I'm not gonna be like, "Oh, by the way, I'm gay." I don't feel like I walk around with a giant rainbow on my head either. I'm kinda just a person. When people start attacking me because they're like, "Oh, no, you're entitled to less rights because you're gay," is when I start being like, "Really?" … I don't decide major life things because I'm gay. It's kind of who I decide to come home to. I don't think that a straight person would define themselves by their boyfriend.

Erin's comment that straight people do not have to "define themselves by" their partners aligns with Muñoz's (1999) contention that queerness cannot exist apart from compulsory heterosexuality. This vignette also shows Erin's willingness to risk punishment by enacting queer performativity through resistance to oppressive comments and heteronormative pressures.

When discussing gender, Erin argued for queer ideals of embracing fluidity and rejecting binaries, but in doing so, Erin also used gender-typified examples to illustrate the point.

I think gender's fluid. I mean that's kind of a weird thing to say, I guess, but I don't –I think gender's fluid for me. In my opinion, you don't have to be feminine all the time. You don't have to be masculine all the time. You can wake up one morning and decide, "You know what? I'm gonna buy boy jeans at Walmart, and a tee shirt, and not wear a bra today," and you're still just as much as yourself as you were when you wore a dress and a bra and the cute little heels that your mom bought you for Christmas. So for me, I don't think gender is so much a thing for me as much as it's just accepting the fact that it moves, and it's fluid, and it doesn't necessarily have to be male/female. Personally, I identify as a female, but just because I'm that doesn't mean I need to run around in skirts and do girly things.

Even though Erin confidently argued for queer ideals (e.g., fluidity), her declaration of ideals was immediately followed by a disclaimer "but I don't think gender's fluid for me" and a resistance to "do[ing] girly things." It seemed that Erin had a grasp of queer terminology (e.g., fluid, moves) and wanted to enact queer performativity. Yet, she framed the argument using limiting sex-laden language (male, female) and restrictive ideas about gender expression (girly things, cute heels).

Isaiah

Isaiah described his disability as "ADD and a history of concussions." Isaiah's queer ideals revolved around the belief that people who relied on fixed sexuality labels were out of touch with contemporary society—a place where people could be "whatever."

As far as sexuality I feel like it's becoming more accepted to just be whatever you are nowadays. But there are some people who definitely are still old school thought processes, where they don't accept mixed labels … or things they don't understand. That's where a lot of problems come from is not understanding somebody … So I like don't – I try not to use labels in terms of like being myself usually. But, when people ask … I try and explain it like I'm 90, 95 percent straight. And then every once in a while I find guys attractive. And I don't need to say whether or not I'm bi or straight it just is what it is. It's really about the person. That's usually how I present it to people.

Although they expressed a desire to resist labels, Isaiah felt obligated to quantify a percentage of straightness revealing a propensity to perform heterosexuality most of the time—despite expressing queer ideals. This quote also suggests the power of compulsory heterosexuality and the ways queerness only becomes real if juxtaposed to straightness (Muñoz, 1999).

Elsewhere in the interview, Isaiah displayed added sensitivity to the social contexts for both disability and gender—although his commentary suggested these identities were separate, versus intersectional, in his life. He noted that the idea that ADHD was a real disability requiring treatment by medication was "very socially unaccepted" and that the experiences of people with concussions were poorly understood. Later in the interview, Isaiah also problematized social thinking about gender norms: "I hate the phrase, 'Be a man.' Because it's just like being an adult—not like macho and stuff. I don't know if that's you, that's fine." This quote suggests a desire to adopt queer ideals by rejecting restrictive gender norms including narrow and restricting "macho" gender performance. Fear of offending the interviewer (a cisgender man) and a desire to avoid negative consequences (e.g., punishment) associated with challenging traditional gender norms, may have prompted Isaiah to say to the interviewer: "if that's you, that's fine."

Poppy

Poppy self-identified as a person with "profound deafness in right ear." Because she had an invisible disability, "a lot of the times people forget that I'm even deaf in one ear … [When I tell them] some people … don't really understand what it means entirely." When speaking about sexual identity, Poppy resisted labels and expressed the queer ideal that sexuality exists on a spectrum.

I prefer not to label. I mean I'm as far as I can tell I'm heterosexual I've always been with men. I think that I will always be with a man. But, I mean if a woman walked into my life and she was everything that I wanted, I wouldn't be like, "You got the wrong anatomy. So you can leave." And I definitely think that that's something that I think about especially with the whole lack of understanding as a society that it's not just black and white. There's a lot of grey. There's a spectrum. Even in terms of gender there's a spectrum a lot of people don't get that and I'm just like no: "Go take a class!" … So the way that I view the world in terms of my gender is a bit different … Even as a female I think that I'm a bit more masculine because I had to fill that male role. I killed all the bugs and took care of all the mice and set up all of the furniture and the TVs and crap.

Poppy simultaneously used a queer ideal (e.g., "prefer not to label") while adopting a label (i.e., heterosexual). The way in which Poppy referred to anatomy (as if it determined intimacy and sexual identity) might also indicate a limited adoption of queer ideals. For instance, the use of sex terms (male, female) and talk of killing bugs and setting up furniture as "male" behaviors might indicate binary thinking. It could also suggest internalization of traditional gender roles and gender (e.g., not queer) performances that do not push back against restrictive social norms.

As a woman with an invisible disability, Poppy held the perspective that the general public needed to be more aware how problematic it can be to make assumptions based on what they think they see (e.g., no disability, heterosexuality, gender). She was frustrated that normative social structures restricted individuals from learning that gender and sexuality existed on a continuum. Nonetheless, Poppy expressed queer ideals and risked punishment by expressing her view of the world as "a bit different." Interestingly, Poppy's interview did not contain any references to intersectionality. While she recognized all of these identities shared the common root of existing within oppressive social structures, she described her disability, gender, and sexuality as distinctly separate aspects of self.

Willow

On our demographic form, Willow self-identified her disability as "dyslexia, reading comprehension [issues]." Willow described divergent queer performances at the university (openly queer) and at home (closeted). Willow did not disclose sexuality to family out of fear of rejection (e.g., punishment).

That is a tricky one. I'm bisexual … I'm very open with my sexuality at the University … I think it just takes me a while to tell people bravely enough, but I don't really want my family to know … I'm not a feminist, but I have friends who are very feminist, and it's a little annoying because I don't – this is what bugs me about gender equality is that people always say, "Feminists are better. We can do just as much as men can do." Okay, then do that quietly like the men are doing.

Willow's queer ideals seemed limited by normative and binary views of gender and gender roles. The expectation that women "do that quietly" suggests a reluctance to engage in queer performativity or adopt non-restrictive queer ideals about gender. In fact, suggesting women be quiet seems steeped in oppressive notions that women should be silent. It also highlights the extent to which people who hold minoritized identities may internalize oppressive systems of thought and possibly use them against other minoritized people via horizontal oppression.

Reyna

On the demographic form, Reyna marked "cerebral palsy" for her disability and "lesbian" for sexual identity. Reyna spoke openly about her disability, which was the most visible form of disability among our participants, and also eloquently described the experiences of alterity that arose from it. This open communication about disability as a core part of sense has been previously theorized as an act of queer performativity (Kafer, 2013; McRuer, 2006). However, when asked during the interview, "How, if at all, do you think about yourself in terms of sexual orientation?", Reyna responded "I wish not to answer that question." Unfortunately, without asking follow-up questions that would have been unethical given her expressed wishes, it is impossible to determine where this hesitation came from since Reyna openly responded to all of the previous interview questions. It is possible that she was uncomfortable talking about her sexuality with her interviewer—a masculine-presenting, cisgender man—or that she was unwilling to speak publicly about her sexuality generally. Consequently, her unwillingness to discuss her sexuality serves to highlight the extent to which the interview process provides inherently unequal access to each of the four continua rather than to reveal her own meaning-making. That is, Reyna could have held sophisticated queer ideals, been finally attuned to issues related to punishment, and embodied intersectional reasoning, but she could not yet be comfortable engaging in the queer performativity requisite to discuss these things in an interview. Additionally, the interview time ran out before gender could be discussed. So, we know very little about how Reyna made meaning of gender besides the demographic form where "woman" was checked off. While Reyna's case does not shed much additional light on the queer continua, it does provide an important discrepant case that highlights the fact that researchers see but one small glimpse of a person's meaning-making—and only if a person allows them to see it.

Discussion

To honor our grounded theory methodology, we offer four theoretical propositions regarding the perspectives on gender and sexuality concepts, identities, and enactments expressed by college students with disabilities who also claimed societally marginalized gender and/or sexual identities. Prior literature has established college as a particularly critical time period for identity construction generally and for the development of individuated understandings of gender, sexuality, and disability specifically (c.f., Vaccaro et al., 2018; Patton et al., 2016). However, no prior work has systematically explored the simultaneous construction of these identities by people with disabilities, which has the effect of rendering gender and sexuality invisible in the lives of college students with disabilities. As the product of a critical inquiry practice designed to disrupt the present thinking about the intersections of gender, sexuality, and disability (Carducci et al., 2011; Renn, 2010), these propositions critique and extend existing understandings by offering an alternative account of the experiences of college students with disabilities.

Theoretical Proposition One

Students' with disabilities thoughts about, identifications with, and enactments of gender and sexuality can be understood in the context of four inter-related continua. First, students expressed queer ideals which reflected diverse thinking about, and rejection/adoption of, restrictive gender and sexual norms, binaries, and labels. For some students, this continuum was theoretical while for others, it was personal. The second queer performativity continuum encompassed the different ways students enacted their gender and sexuality queer ideals through everyday language and behavior. The third continuum represents varying levels of concern regarding punishment (Foucault, 1978) when adopting queer ideals and engaging in queer performativity. The fourth intersectionality continuum explicates variations in student propensity to discuss and/or reflect upon their single and/or intersecting gender, sexual, and disability identities as intersectional (e.g., mutually constituting, reinforcing) (Shields, 2008).

Theoretical Proposition Two

Variations among the four continua suggest students exhibited different levels of readiness to adopt queer ideals, enact queer performativity, experience punishment, or consider intersectionality. While prior research has emphasized the superordinate nature of disability identity (Rohmer & Louvet, 2009), our findings demonstrated that there were not only differences among the 12 students, but within each student in regard to the process and pace at which they made meaning of queer ideals, performativity, punishments, and intersectionality. For some students that meant that disability was central to their understanding of gender and sexuality and for others it did not. Presenting our findings as extended vignettes shows similarities as well as variations by, and between, students. Had we presented the findings in four continua sections and divided student stories into shorter quotes, the complex and sometimes subtle distinctions within each student vignette would have been difficult to see.

Some students adopted restrictive societal labels and messaging for one social identity, but not others. For example, a student might express queer ideals and engage in queer performativity in regard to gender, yet still accept normative messaging about sexual identity—or vice versa. For instance, Aricelli was closeted around family and referred to her partner as a "stereotypical lesbian," suggesting some acceptance or internalization of restrictive sexual orientation norms and fear of punishment. However, she expressed more radical queer ideals about gender fluidity and a desire to raise her child in a gender-inclusive environment.

Notably, many participants appeared quite measured in their performances of queer ideals in deference to normative social structures. Tierney and Dilley (1998) suggest "queer theorists seek to disrupt 'normalizing' discourses" (p. 61). Our data show that although students may have adopted some queer theoretical ideals (e.g., fluidity, breaking binaries, rejecting labels), many simultaneously perpetuated normalizing discourses. These findings are not altogether surprising given the totalizing nature of normative systems, wherein even those who seek to resist or escape their logic are also bound by it. In essence, participant narratives suggest a complex view of queering the world—with students sometimes disrupting and perpetuating normalizing discourses simultaneously. Even participants who exemplified queer ideals also used oppressive language, adopted restrictive labels, conflated gender and sex terms, and participated in behaviors that reflected an acceptance of restrictive norms. For instance, Erin expressed queer ideals such as gender fluidity. However, her queer performance seemed limited by restrictive societal messages about appropriate attire (e.g., boy jeans). In other cases, students used restrictive sex terms (e.g., male, female, transsexual) while simultaneously expressing radical and seemingly inclusive queer ideals that rejected binaries, labels or other exclusionary gender and/or sexual messaging. Such divergent and seemingly contradictory ideals and performances exemplify the messy developmental processes for students with multiple intersecting marginalized identities.

Queer and crip theory scholarship often suggests queer paradigms are inherently about intersectionality (Abes & Kasch, 2007; McRuer, 2006). In fact, Abes and Kasch (2007) contend intersectionality and queer theory cannot be separated when they argue queer theory "critically analyzes the meaning of identity, focusing on intersections of identities" (p. 620). However, we caution against adopting intersectionality as the only tool for understanding the lives of students with disabilities with queer gender and sexualities. Making meaning of intersectionality requires careful scaffolding from simple to more complex ideas and thoughtful attention to student readiness. Some students, like those whose vignettes appeared first were explicit about the ways intersecting identities of gender, sexuality and disability shaped their lived realities. They articulated the confluence of their multiple identities and described how disability, gender, and sexuality "serve[d] as organizing features of social relations, mutually constitute, reinforce, and naturalize one another" (Shields, 2008, p. 302). Other students did not discuss intersections among their disability, gender or sexuality—and some even refused to talk about certain identities. Put simply, it is neither fair nor realistic to expect that simply because an individual possesses multiple minoritized identities that they will have a complex, fully intersectional self-understanding. Nor should we assume that a person with a disability would not have intersectional views of self. Instead, divergent perspectives and actions regarding intersectionality reinforce our arguments about the complex nature of development.

Our findings contribute to the largely theoretical literature base that portrays "ideal" notions of intersectionality, punishment, and queer performativity. Our data showed that students can simultaneously adopt, reject, understand or fail to comprehend the queer paradigms as described in the scholarly literature. Moreover, each student exhibited a unique state of developmental readiness. For instance, while some students spoke eloquently about intersectionality, others had little or nothing to say about particular identities and/or did not describe their identities as intersectional (e.g., mutually constituting and crosscutting) (Shields, 2008). As developmental scholars, we honored these diverse developmental trajectories by representing participant meaning-making as they reported it to us. That is, we took care not to adopt intersectional, queer, or crip lenses for participant meaning-making where our participants did not; however, where possible, we do also point out possible interpretations within participant narratives that highlight possible intersectional, queer, and crip interpretations that go beyond the limits of the data available to us. As a result, our findings add to the literature by cautioning theoreticians to overlay idealistic theoretical concepts on the narratives of individuals who do not express such perspectives. We contend such analyses are developmentally inaccurate and an inappropriate use of researcher power.

Theoretical Proposition Three

The tension between the sense of self of students with disabilities and the influence of normative social structures related to gender, sexuality, and disability means that identity development takes place within a liminal space. Traditional identity development models typically suggest that the identity development is an individual-focused process (Patton et al., 2016). Our data suggest otherwise. Disability-, gender-, and sexuality-based oppression represented significant influences in the lives of our participants. The four inter-related continua about ideals, performance, punishment, and intersectionality show how students with disabilities navigated questions about identity and normative social structures simultaneously. Their vignettes suggest that it would be artificial to separate questions traditionally associated with identity development (e.g., "Who am I?) from those of social group membership (e.g., "Who does society want me to be?). As students with disabilities navigated oppressive messages about gender, sexuality, and disability, they simultaneously attempted to figure out who they were, what ideals they believed in, and how they could enact/perform those ideals in light of very real punishments (e.g., exclusion, ridicule, rejection). As such, our findings suggest students with disabilities inhabited a liminal space between identity and normative social structures as they navigated their genders and sexualities. See Figure 1.

Additionally, our data reinforces the importance of translating this liminality into individual, developmental terms. Participants engaged in queer performances to enact queer ideals (e.g., rejecting restrictive norms), reflected on punishments, and made meaning of intersectionality in radically different ways. Consequently, we view queerness as a liminal, fluid and messy developmental process—not a state of being or series of stages as suggested by much student development literature (e.g., Forber-Pratt & Aragon, 2013; Gibson, 2006). One of our contributions to the literature is that our work problematizes disability identity models that are predicated on a single identity lens and disconnected from the four continua that emerged in our study. Additionally, we also acknowledge that our data represents only a small piece of each participant's developmental journey. Our findings neither capture participants' meaning-making fully over time nor do they suggest that the observed balance between self and normative social structures will hold consistent over time.

Theoretical Proposition Four

The three theoretical propositions articulated above can be integrated into a grounded model that offers insight into the ways queer students with disabilities constructed their gender and sexuality. This heuristic model (Figure 1) places queer ideals, queer performativity, intersectionality, and punishment at the center of the model. It also suggests that these continua mediate between a person's sense of self and normative social structures; reflecting this tension, arrows connect normative social structures to the self and both the self and normative social structures to the continua. Because this small qualitative study cannot claim statistical relationships or direction, we use a dotted box around the four continua to convey the idea that queer ideals, queer performativity, intersectionality, and punishment function in tandem with one another. While the continua appear in a plethora of disciplinary literatures, our work is unique because it combines them into one theoretical model.

Future research should explore these potential relationships further. The centrality of the four continua in the model is intended to demonstrate the extent to which the continua were the primary finding of this study and also to decenter the idea of self. While many student development models place a student's sense of self at the core of the model, our findings highlight the way that students understand themselves is a complex, messy process. Centering the self emphasizes the idea of self-direction at the expense of the process of self-discovery. For queer people, privileging the idea of self-direction risks understating the extent to which the process of self-discovery relies on normative and restrictive social discourses beyond an individual's control and further risks ignoring the time self-discovery processes take.

As noted in Theoretical Proposition Two, no two students with disabilities in our sample manifested precisely the same configuration of queer ideals, queer performativity, intersectionality, and punishment as they navigated their understandings of self and normative social structures related to gender and sexuality. Their lived experiences could be located at various places on the four continua. Normative social structures exert a form of environmental press that sends powerful messages about socially acceptable ideals and performances related to gender, sexuality, disability, and intersectionality. These normative structures also teach individuals that punishment will result when individuals ignore or resist hegemonic norms. As such, normative social structures appear at the top of the model showing press on the continua which, thereby shape a person's sense self. There are also direct arrows from normative social structures to self to denote the myriad of other presses (outside the scope of our continua) that individuals experience. Framing normative social structures as we have, incorporates Theoretical Proposition Three's recognition that students with disabilities are engaged in acts of liminality as they make meaning of their genders and sexualities. This depiction means that both normative social and self function as the visual and conceptual anchors at the periphery of the model while the continua sit at the center of the model and describe any changes therein. In sum, the end result of depicting Theoretical Propositions One, Two, and Three as an integrated, grounded model is that it can also serve as a heuristic and impetus for future research.

Implications and Recommendations

Our study findings emerge from a rich tradition of queer, crip scholarship addressing the potential for transgression against oppressive norms in the gender and sexual identity constructions of people with disabilities (e.g., Butler, 2004; Kafer, 2013; McRuer, 2011). Within this literature base, we acknowledge that our findings appear to offer only limited expansion of existing theory and empirical findings. However, most of this literature focuses on the gender and sexual performance of adults with disabilities. In focusing on college students with disabilities, we reveal the messy work of constructing queer, crip identities in a key time for identity development. As such, our findings establish the foundation for future research that delves even more deeply into the ways students with disabilities learn and adopt queer ideals and enact queer performativity as an ongoing developmental process. Additional research should explore the congruence (or lack thereof) between students' thoughts (e.g., queer ideals) and behavior (i.e., queer performances) and how these phenomena shape student's sense of self. For instance, how is it that so many students expressed relatively radical queer ideals (e.g., fluidity, spectrums, rejecting labels, breaking binaries) while simultaneously using restrictive language (e.g. female, male, 90-95% straight) and norms (e.g., "male role-killing bugs"). Did this incongruence result from a lack of knowledge and/or developmental readiness? Our findings do not provide a full answer to this question, but highlight the need for future scholarly attention. Despite the need for more research, we believe that these findings can inform practice. All educators, no matter their role in higher education, can engage in efforts to deconstruct restrictive norms by: using inclusive language; queering curriculum and extra-curriculum; challenging binary thinking and behavior from students and colleagues; and working to change individuals who, and systems that, deliver punishments.

Educators must also see students with disabilities as whole people with complex, interesting identities. As crip theorists have suggested (Kafer, 2013; McRuer, 2011), and we have argued throughout this paper, gender, sexuality, and disability are intricately related to one another. Unfortunately, educators and researchers have often focused their attention on campus accommodations and academic outcomes, paying no attention to the fact that students with disabilities navigate complex gender and sexual identities in college. Likewise, educators have infrequently considered the role that assumptions of ablebodiedness play in students' experiences of sexuality and gender. Our findings powerfully demonstrate why educators must begin to view students with disabilities through a holistic lens and offer support services, courses, workshops, and everyday conversations that honor their range of experiences with intersectionality. A key part of viewing students with disabilities holistically is the adoption of intersectional approaches to both research and educational practice. While our work contributes empirical evidence about the intersection of disability, gender, and sexuality, more work is still needed. In particular, work that examines the role that race plays in experiences of disability—including experiences related to gender and sexuality—is needed. Prior research has shown that disability functions as a superordinate form of identity for many people with disabilities (Rohmer & Louvet, 2009) but the extent to which that may vary by race is unclear. Given that prior intersectional approaches to critical theory have well-documented the central influence of race in the lives of People of Color in the "white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchical state" (hooks, 2000, p. 22), a more nuanced understanding of the role of race in the construction of disability, gender, and sexuality is needed.

Scholars and educators should explore the connections between generational norms, academic curriculum, and student development. It is possible that our participants were attempting to use generationally appropriate (see Isaiah), inclusive, and queer ideals learned in "progressive" undergraduate classes without internalizing the scope and depth of what words like fluidity and spectrum really meant. We did not have access to student course histories, but quite a few participants mentioned gender and women's studies courses. Concepts learned in queer-affirming courses likely influenced the adoption of queer ideals and students' meaning-making processes. Unfortunately, our data did not allow for an in-depth analysis of student academic histories or the processes by which they came to understand queer, feminist and other counter-hegemonic ideals. Future research should explore if, and how, students learn, adopt and or reject counter-hegemonic concepts/paradigms/terms (e.g., feminism, non-binary notions, queer theories) and how that formal education shapes their worldviews and senses of self.

Faculty and higher education administrators should think carefully about their curricula and pedagogy when crafting courses and extra-curricular programming. Educators who introduce students to queer ideals and encourage queer performativity have an obligation to scaffold learning so that students can move beyond the basics. Informing students about ongoing educational opportunities to delve more deeply into queer theory, intersectionality, and other boundary pushing education is a good way to ensure that queer learning continues. However, we cannot assume that students who adopt certain queer ideals will not simultaneously hold and/or enact other oppressive perspectives or behaviors (e.g., racist, misogynist, classist, cissexist, heterosexist).