Previous organizational research has focused heavily on organizational commitment, for employees in general, as well as for specific minority groups. However, there is a large gap in the research literature concerning the organizational commitment of people with disabilities. The current study contributes to the literature both by investigating the predictors of reported organizational commitment of people with disabilities, as well by examining organizational-level predictors, rather than individual-level phenomena. Additionally, rather than examining legal or compliance issues related to people with disabilities, as is found in most previous research, the current study examines contextual predictors of organizational commitment, pro-disability climate, pro-disability technology, and availability of flexible work arrangements. Structural equation modeling results suggest that there is a chain effect of pro-disability climate, which impacts the organizational commitment of people with disabilities through pro-disability technology and flexible work arrangements. Implications for both research and human resource practitioners are discussed.

Valuing Employees with Disabilities: A Chain Effect of Pro-disability Climate on Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment is the degree to which individual employees are emotionally attached to their organizations (Mowday, Steers, & Porter, 1979). Organizational commitment has triggered a huge amount of scholarly attention over the past decades, as it has been shown to relate to performance improvement and a decrease in withdrawal behaviors and turnover, as well as improvement in employees' general wellbeing (Cooper-Hakim & Viswesvaran, 2005; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002; Riketta, 2002). As diversity in the workforce continues to be a large source of discussion, research has attempted to examine organizational commitment from diverse groups such as female employees (e.g., Malone & Issa, 2014) and older workers (e.g., Crowne, Cochran, Carpenter, 2014; Herrback, Mignonac, Vandenberghe, & Negrini, 2009). However, there has been scarcity of research related to the organizational commitment of people with disabilities. People with disabilities are the largest minority in our nation (estimated 1 in every 5 people) (US Census Bureau, 2012). Although estimates vary, there are 19.8 million working-age (21-64) Americans with disabilities, and this number continues to grow as more soldiers with disabilities return home from the Middle East and our population continues to age. Additionally, more people are qualifying as having a disability under the recent amendment of the American's with Disabilities Act (now ADAAA, 2008) (Wittmer & Wilson, 2010). Despite their high prevalence rates in world populations, people with disabilities are underemployed (10.1% compared to 5.1% for people without disabilities; Office of Disability Employment Policy, 2015), and those who are employed, face a variety of barriers in the workplace (e.g., Hyland & Rutigliano, 2013; Wittmer & Wilson, 2010).

While there is a substantial amount of research on issues that people with disabilities face in the workplace, little, if any, research examined why people with disabilities may or may not be committed to their organizations of employment. Thus, organizational commitment from this specific minority group deserves a fair amount of scholarly attention. One of the most cited issues people with disabilities face in the workplace is negative attitudes toward this group. Wittmer and Wilson (2010) cited several myths about employees with disabilities, such as poorer job performance and higher workman's compensation rates, which lead to these negative types of attitudes. These attitudes are often held at the highest levels within the organization and are likely to spread to the lower levels. Additionally, perceptions of fairness concerning accommodations (e.g., Colella, Paetzold, & Belliveau, 2004), are likely to lead to negative coworker reactions. Thus, while there exist many tax and other practical incentives enticing organizations to hire people with disabilities (e.g., Wittmer & Wilson, 2010), negative attitudes towards these people from all levels within the organization will likely impact their organizational commitment. Negative attitudes impact how often supervisors and coworkers communicate with employees with disabilities, how they desire to work closely with these individuals, how these individuals are evaluated, and how they are placed into jobs or promoted. Additionally, workers with disabilities are at a greater risk for stress-related disorders and injuries and experience lower self-esteem due to inadequate social support (Matt & Butterfield, 2006). These negative outcomes, in turn, impact the responses from employees with disabilities, such as lowered organizational commitment (e.g., Shur, Kruse, & Blanck, 2005).

While the majority of research concerning the successful employment of people with disabilities has focused on legal aspects, such as providing accommodations (Colella & Stone, 2005), less research has focused on issues concerning the context of the organization, specifically creating a climate that promotes diversity, tolerance, and support (e.g., Matt & Butterfield, 2006; Erickson, von Schrader, Bruyère, & VanLooy, 2013). This research suggests that an organizational climate that is pro diversity can positively impact treatment towards workers with disabilities and may be the key to their successful integration in the workplace. A climate that supports diversity can shape supervisors' as well as coworkers' attitudes and obligations towards employees with disabilities (Erickson et al., 2013), and motivates employees without disabilities to offer help to employees with disabilities (Florey & Harrison, 2000).

The main purpose of this study is to investigate organization-level practices and their relation to reported organizational commitment of people with disabilities. Inquiring about factors influencing commitment from employees with disabilities can inform organizations and help guide policies and practices used to increase commitment in these employees. Susanne Bruyère, Director of the Employment and Disability Institute (EDI) at Cornell University shared that one of the best ways to measure workplace inclusion of people with disabilities is to examine disclosure statistics. It stands to reason that if people with disabilities perceive an organization as being more pro-disability, they will be more likely to disclose their disability to others in the organization. Thus, Bruyère and her colleagues investigated what factors led people with disabilities to disclose or not to disclose. From an organizational practice perspective, they found that for organizations, having supportive supervisors, being a disability friendly workplace, having active disability recruiting practices, and having "disability" in their diversity statement, are important predictors of individual disclosure. Also, their research mentioned that organizations offering flexible work arrangements have more people disclosing disabilities (von Schrader et al., 2013). Lastly, Bruyère and her colleagues identified inaccessible technologies, both in equipment as well as programing, as a potential barrier to people with disabilities. Organizations that provide accessible technology and computer programs are more likely to successfully support people with disabilities (Bruyère, Erickson, VanLooy, 2006).

Given the above research, the current study seeks to examine if the organizational practices leading to increased disclosure are also related to organizational commitment. Thus, this study tests the chain effect of pro-disability climate on reported organizational commitment of employees with disabilities. We argue that pro-disability climate produces a chain effect on organizational commitment from employees with disabilities. First, we will provide evidence supporting the direct effect of pro-disability climate on the reported organizational commitment of employees with disabilities. Next, we will examine whether pro-disability climate also has some indirect effect on organizational commitment, through organizational factors that are likely to impact people with disabilities. Specifically, we examine the implementation of pro-disability technology and flexible work arrangements, both shown to accommodate those with disabilities and provide them a more productive work experience (Baumgartner et al., 2015; Shinohara & Tenenberg, 2009; von Schrader et al., 2013), thus likely increasing their organizational commitment. In the current study, all phenomena are tested at the organization level. Thus, organizational commitment of people with disabilities is reported through top-level human resources (HR) professionals. Top-level HR professionals are appropriate given von Schrader et al.'s (2013) finding that people with disabilities are most likely to disclose to HR professionals and are more likely to disclose with, "HR personnel who are familiar with disabilities, accommodations and understand it is a goal for companies" (p.1). The participants in the study are nearly all members of employer networks (such as the Business Leaders Network) that have the purpose of educating and supporting other employers in hiring individuals with disabilities. All HR professionals stated that they collected climate information from employees; as well, they are responsible for training and supporting the implementation of employee supportive technology.

Theory and Hypotheses

The study of organizational climate's impact on individual organizational members' behaviors can be traced back to as early as the late 1930s (Schneider, Ehrhart, & Macey, 2011). Similar to organizational culture, organizational climate is concerned with the social aspects of an organizational environment, on which organizational members tend to have a consensus (Denison, 1996). It refers to shared perceptions of organizational members about organizational events and characteristics (Reichers & Schneider, 1990), and constitutes the "shared, holistic, and collectively defined social context" (Denison, 1996, p. 625). As organizational climate has been extended to refer to some specific areas of organizational life, it is usually used with a specific focus. Past research has examined organizational diversity climate, which represents a qualified version of organizational climate in diversity and is defined as shared perceptions about an organization's diversity related formal structure as well as its informal values (Gonzalez & DeNisi, 2009).

The current study further specifies diversity climate to examine pro-disability climate. The development of a pro-disability climate is a result of an organization's efforts to promote inclusion of people with disabilities typically through human resource policies and initiatives to create a more inclusive workplace. Such an inclusive climate "advocates fair human resource policies and socially integrates underrepresented employees" (McKay, Avery, & Morris, 2008, p. 350). An organization with a pro-disability climate tends to value diversity as an asset and proactively capitalizes on its benefits in promoting the professional growth of their employees and the overall growth of the organization itself (Chen, Liu, & Portnoy, 2011). Perceptions of a pro-diversity climate are derived from such things as a the proportion of managers who have undergone disabilities awareness training, managers' awareness of disability policies and practices, and from managers' perceptions that policies are made from a genuine commitment to people with disabilities and not out of legal compliance. Employees with disabilities may then feel more embedded within the organization, perceive more support, have a better quality relationship with their immediate supervisor, feel better with their job demands, have higher organizational commitment, and experience less disability-related bias (Nishii & Bruyère, 2013).

Pro-disability Climate and Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment is an important construct capturing employees' feelings and perceptions of an organization. It refers to the degree to which individual employees are emotionally attached to their organizations (Mowday et al.,1979). Organizations with a pro-disability climate represent themselves to employees as highly dependable and ethical, and, because they value people with diverse backgrounds, they are perceived to treat people more equitably and respectfully. In reciprocity, individual employees in these organizations are more likely to develop a strong attachment to their organization. The positive association between a pro-disability climate and employees' organizational commitment has received research support (Nishii & Bruyère, 2013).

Pro-disability Climate and Implementation of Pro-disability Technology

The presence of a pro-disability climate in organizations suggests that leaders take active steps in promoting diversity to make the pro-disability climate perceivable and experienced by individual organizational members. To demonstrate presence of a pro-disability climate in their organizations, leaders, such as HR directors, must show commitment by providing support to people with disabilities, both applicants and employees. Thus, a pro-disability climate entails policy support and equity recognition (Hicks-Clarke & Iles, 2000). Equity recognition refers to functioning of organizational (procedural and distributive) justice in resources allocation and distribution (Hicks-Clarke & Iles, 2000). Policy support means that organizations establish favorable policies to bring instrumental benefits , such as mentoring, childcare, career break, and flexible working arrangements, as well as special accommodations for those with disabilities who need it (Hicks-Clarke & Iles, 2000), all of which may well be supported by proper technology implementation. For example, flexible working arrangements, such a telework, must have the proper technological foundation.

While the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (1990), now ADAAA (2008), mandates that federal contractors provide technology that is accessible, not all organizations make these improvement to their technology. In fact, the Department of Justice published the results of their 2001-2004 study, suggesting that even federal contractors had much room for improvement in making technology accessible for people with disabilities. President Obama, as part of his 2009 directive to increase the recruitment, hiring, and retention of people with disabilities, stated, through the directive, that agencies should implement strategies for hiring and retaining workers with disabilities, including "increasing access to appropriate accessible technologies, and ensuring the accessibility of physical and virtual workspaces."

Typically, however, technology implementation within organizations is driven by strategic and operational goals. Many new technologies are aimed at increasing efficiency, reducing costs, and improving operational performance. While, at the same time, technology can be implemented with the user in mind – to make the work more inclusive, user friendly, and, thus, more productive as well (Goncalves et al., 2013).

Technology aimed at making work more inclusive recognizes that many with disabilities struggle with traditional technology (Bruyère et al., 2006). For example, people with disabilities lag behind the rest of the population in Internet use (about half rate, 21.6% compared to 42.1%) (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2000). Factors contributing to this discrepancy include: income or affordability, feeling technology intimidation, and technical accessibility barriers, while the latter remain the most probable cause for lagging behind. When a person trying to use some software or hardware finds himself or herself confronted by a range of technical problems, he or she is likely not only to stop trying but also to develop a fear of technology (Vicente & Lopez, 2010).

Further, after a technology is implemented, accessibility for people with disabilities may emerge as an issue. Thus, new technology may pose barriers to such employees. Indeed, early research documented such issues. For example, in a survey distributed to HR representatives from companies in 2002, it was revealed that online technologies were extensively used for HR processes in those companies, but only 30% of the 433 respondents indicated that their organizations tested accessibility for people with disabilities when a new technology was implemented (Bruyère et al., 2006). The issue of insufficient accessibility for people with disabilities still persists today. For the Forbes 250 companies, their enterprise website accessibility levels are still in need of significant improvement (Goncalves et al., 2013). For companies, their lack of awareness of special concerns and needs stemming from employees with disabilities was an alarming sign that a pro-disability climate was not strong in those companies. Besides those factors identified in the literature, especially the accessibility issue, people with disabilities also are disadvantaged in overall digital literacy (Park & Nam, 2014), which means the capability of recognizing and finding needed information efficiently and generating and evaluating information using digital technologies (Beetham & Sharpe, 2007). However, if accessibility and other technical issues that hamper people with disabilities from using technologies are well addressed, they are very capable of becoming digitally literate (Park & Nam, 2014). Over the years, assistive technologies have been developed to accommodate the special needs of people with disabilities so that they can use regular technologies to complete their job tasks (Shinohara & Tenenberg, 2009). Moreover, information communication technologies can empower individuals with disabilities, creating conditions for self-advocacy and inclusion, and counter negative perceptions of disability (Ratliffe, Rao, Skouge, & Peter, 2012). Thus, if a company has a strong pro-disability climate, it would likely adopt and implement such assistive technologies to benefit its diverse workforce. Specifically, we argue that companies that have a pro-disability climate are more likely to recognize the need for and implement technology designed to be more inclusive and user-friendly to diverse groups of workers, which we refer to as pro-disability technology.

Pro-disability Technology Implementation and Flexible Work Arrangements

Flexible work arrangements (FWA) refer to organizational initiatives or policies that enable employees to work for their organizations at times and places outside of the organization and/or outside of the normal workday. These arrangements include but are not limited to flextime, absence autonomy, compressed work weeks, reduced schedule, telework, extra vacation days, limited schedule of meetings, flexible holidays, and keeping with the schedule (de Sivatte & Guadamillas, 2013; Haar & Spell, 2004; Rogers, 1992). Empirical research suggests that technology enables FWA. Specifically, technologies such as mobile devices, cloud services, desktop virtualization, video conferencing, social media, unified communications, and bring-your-own device schemes can enable successful flexible working (Flinders, 2012). Askenazy and Caroli (2010), in their study that investigated the effects of work time flexibility, quality norms, participation, and information communication technology (ICT) on mental strain, occupational risks, and injuries, found that ICT is positively correlated with work time flexibility. Additionally, drawing on the affordance perspective, Zammuto et al. (2007) argued that ICT has enabled emergence of multiple new forms of organizing, providing alternatives to the traditional hierarchy. A major reason for that type of organizational transformation is that ICT offers enough flexibility to organizations. The flexibility can certainly be reflected in multiple forms of work arrangement for employees. While these regular information technologies provide the benefits of flexibility in work arrangement, assistive and other pro-disability technologies help persons with disabilities to effectively use information technologies (e.g, Kent, 2015).

Pro-disability Climate and Flexible Work Arrangements

Technology provides the materiality of FWA. However, even where FWA are made a possibility, employees may or may not be permitted or choose to utilize them. Practices of FWA still depend heavily on the organizational climate. Managerial support, an important dimension of organizational climate, affects employees' use of such FWA (de Sivatte & Guadamillas, 2013; Dikkers et al., 2007; Thompson et al., 1999). Research demonstrates that despite the availability of FWA, organizational informal support, and peer use of these arrangements determine, to a great extent, employees' use of these arrangements (de Sivatte & Guadamillas, 2013; Kossek, Barber, & Winters, 1999). Also, managerial support is positively related to employees' use of FWA (de Sivatte & Guadamillas, 2013; Dikkers et al., 2007; Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999). Specifically, employees understand that managers may interpret employees' motivation for using FWA differently. Managers may attribute employees' use of FWA for the purpose of enhancing their productivity or for simply improving their personal life (Leslie, Park, & Mehng, 2012). When managers have a high productivity attribution, they perceive employees who use FWA as more committed than employees who do not use those arrangements (Leslie et al., 2012). Alternatively, employees perceived as using these arrangements for managing their personal life, often feel discouraged to use those benefits. If managers regard FWA as subject to and secondary to business imperatives, it indicates that the promotion of organizational diversity is a low imperative (Michielsens, Bingham, & Clarke, 2014).

Flexible Work Arrangements and Organizational Commitment

Prior research has examined the relationship between FWA and organizational commitment with mixed findings. On one hand, it has been found that employees attach much value to FWA (Rodgers, 1992; Haar & Spell, 2004) because they help to reduce work-family conflicts (e.g., de Sivatte & Guadamillas, 2013), which helps to enhance their organizational commitment (Casper & Harris, 2008; de Sivatte & Guadamillas, 2013; Hornung & Rousseau, 2008; Kelliher & Anderson, 2010; Thompson et al., 1999). Similarly, as FWA enables individualization, provides convenience, and helps to meet personal needs, based on reciprocity, individual employees develop a sense of obligation to pay back the valuable contribution their organizations have made (Casper & Buffardi, 2004; Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, Lynch, & Rhoades, 2001; Rousseau, 2001). Therefore, employees would develop a positive affect to their organizations. Further, a meta-analysis of empirical research (991 articles) on perceptions of telework, one type of FWA, and organizational outcomes supported the positive relationship between telework and organizational commitment (Martin & MacDonnell, 2012).

On the other hand, some studies did not support the link between FWA and organizational commitment. For example, in a study that used a sample of 514 French late-career managers representing a variety of occupations and organizations, Herrback, Mignonac, Vandenberghe, and Negrini (2009) found that flexible working conditions were not related to affective commitment. Also, Caillier (2013) found that while some types of FWA (telework) is positively associated with organizational commitment, others (flextime and compressed workweeks) are not. These mixed findings may be due to the use of different conceptual and operational definitions of organizational commitment in prior research. For example, Kelliher and Anderson (2010) used a British sample and a broad definition of organizational commitment (it included identification). Likewise, Hyland, Rowsome, and Rowsome, (2005) used an Irish sample, and Meyer and Allen's (1997) definition and scale of organizational commitment, which is also a broad definition of the concept. In addition to different conceptual and methodological approaches that may have contributed to the mixed results in past studies, another aspect of past research also motivates us to reconsider the relationship between FWA and organizational commitment. Most past studies attempted to link FWA to organizational commitment of employees in general. The few studies that specifically examined the relationship between FWA and organizational commitment of diversity groups (e.g., older employees in Herrback et al., 2009) rarely included employees with disabilities.

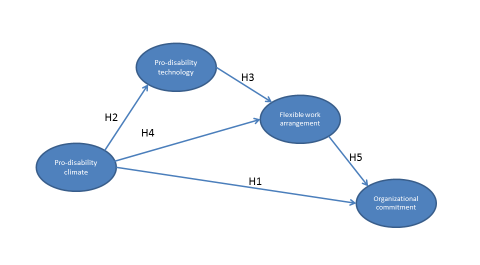

Based upon the above, the following hypotheses are presented:

H1: Organizations with a higher pro-disability climate have higher organizational commitment among employees with disabilities.

H2: An organization's pro-disability climate is positively related to its implementation of pro-disability technology.

H3: Pro-disability technology implementation is positively related to the availability of flexible work arrangement for employees with disabilities.

H4: Pro-disability climate is positively related to the use of flexible work arrangements for employees with disabilities.

H5: There is a positive relationship between organizations with flexible work arrangements and the organizational commitment of employees with disabilities within these organizations.

Figure 1. Conceptual model

Note: Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized model with direct relationships between pro-disability climate and pro-diversity technology, FWA, as well as organizational commitment. Also hypothesized is a direct relationship between pro-disability technology and FWA, as well as a direct relationship between FWA and organizational commitment.

Method

Data

Data collection took place in two waves from January to April 2014 as a part of a larger study concerning the successful employment of people with disabilities. Data were collected from HR Leaders (Directors or top managers) from mostly Fortune 500 companies (56%). The companies ranged in size between 5,000 employees to the largest of the companies representing over 400,000 employees worldwide). HR Directors and managers were contacted through human resource and leadership associations, as well as personal contacts, via email and were invited to participate in an online survey. Emails were sent to the HR Directors and managers from the leaders of these associations who encouraged recipients to participate. Eighty-six surveys were completed after two follow-up emails were sent (for an estimated response rate 20%). The respondents represented organizations from a variety of industries (e.g., healthcare, oil, consumer goods, electric, auto, manufacturing, etc.) and had an average tenure with their respective organizations over 5.1 years. These leaders were chosen to participate in this study because of their unique knowledge and access to information/data concerning the employment of people with disabilities, in general, and compared to employees without disabilities in their organization. These individuals were asked to respond to the questions based upon objective information and data, rather than subjective opinion. The purpose of the larger study was to gain information about organizational practices for increasing the successful employment of people with disabilities. Thus, additional information about the types of job held by people with disabilities, specific accommodations made, as well organizational barriers to providing accommodations and support to people with disabilities was also collected.

Variables

Pro-disability Climate was measured with 5 items (alpha = .90) on a five-point Likert scale adapted from 2012 SHRM study: Employing People with Disabilities: Practices and Policies Related to Recruiting and Hiring Employees with Disabilities. For example, "Our organization has a written policy regarding hiring people with disabilities." While there are two conflicting viewpoints of how climate should be measured within an organization (Glick, 1988; James, 1982), a thorough discussion of this debate (e.g., Baer & Frese, 2003; Denison, 1996) is beyond the scope of this paper. However, as opposed to viewing pro-disability climate as an aggregated set of individual perceptions, we have chosen to view pro-disability climate more in line with Glick (1988) who has repeatedly argued for the conceptualization of organizational climate as an organizational, rather than individual, attribute, resulting from sociological and organizational processes. Thus, climate is an organizational, rather than psychological, variable that described the organizational context for individuals' actions (Baer & Frese, 2003; Schneider, 1990). Given that we are more interested, within this study, in actual organizational practices (e.g., technology development and availability of FWA), rather than subjective perceptions, our definition of climate is more in line with the conceptualization of organizational climate from Glick (1988), Schneider (1985), and Schneider and Reichers (1983) in terms of other constructs such as interpersonal practices, intersubjectively developed meanings, and policies and practices, and not as a mere aggregation of psychological climate.

Organizational Commitment was measured with 4 items (alpha = .83) on a five-point Likert scale. The measure was adapted from Klein, Coooper, Molly, and Swanson (2013) for people with disabilities. For example, "People with disabilities in our organization are committed to our organization." Participants were prompted to consider turnover rates of people with disabilities as a whole and compared to those without disabilities, as well as any information gathered via exit interviews and employee opinion surveys.

Pro-disability Technology was measured with 4 items (alpha = .92) on a five-point Likert scale. For example, "Our organization considers the needs and concerns of employees with disabilities in our technological planning." These items were created specifically for this study and were pilot tested with a group of twenty HR managers.

Flexible Work Arrangements was measured with 9 items (alpha = .89) on a five-point Likert scale. The measure was adapted from the When Work Works (2012) Workflex: Employee Toolkit. For example, "Our organization offers telecommuting (working remotely) to employees with disabilities."

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables of the study. Also displayed are the Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients for the measures in parentheses in the diagonal entries. All constructs are significantly related to each other. All correlations are in the proposed directions. Organizational pro-disability climate is positively related to pro-disability technology (r = .58, p < .01), flexible work arrangement (r = .52, p < .01), and organizational commitment (r = .24, p < .05). Pro-disability technology is positively related to flexible work arrangement (r = .77, p < .01), and organizational commitment (r = .18, not significant). Flexible work arrangement is positively related to organizational commitment (r = .30, p < .01).

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1. | Pro-disability Climate | 17.34 | 4.56 | (.90) | |||

| 2. | Pro-disability Technology | 13.19 | 3.91 | .58** | (.92) | ||

| 3. | Flexible Work Arrangement | 29.73 | 8.03 | .52** | .77** | (.89) | |

| 4. | Organizational Commitment | 16.80 | 2.48 | .24* | .18 | .30** | (.83) |

All correlations were tested two-tailed. The diagonal entries in parentheses reflect Cronbach's alpha internal consistency reliability estimates.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

Measurement Model

To provide evidence that the constructs used in this study have convergent validity, we examined the items measuring organizational pro-disability climate, pro-disability technology, flexible work arrangement, and organizational commitment in competing measurement models (see Table 2). A single factor model examined the goodness of fit when all the items of the four constructs loaded on one common factor. Next, four two-factor models were formulated: 1) technology, FWA, and organizational commitment as one factor; 2) climate, technology, and organizational commitment as one factor; 3) climate, technology, and FWA as one factor, and 4) climate, FWA, and organizational commitment as one factor. Then, four three-factor models were created: 1) climate and organizational commitment merged as one factor; 2) climate and technology merged as one factor; 3) FWA and organizational commitment merged as one factor; and 4) FWA and technology merged as one factor. Finally, a four-factor model was developed to test the hypothesized data structure, with climate, technology, FWA, and organizational commitment items loaded on independent factors. To compare the goodness of fit of these measurement models, we used the chi-square test, the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) as key indicators. Models with CFI and TLI values of .90 or higher, and RMSEA values of less than .08 are considered as acceptable (Bentler, 1990). The comparison of all the measurement models using the above mentioned indices indicated that the four-factor model provided the best fit to the data. As the fourth item measuring organizational commitment had a loading of below the 0.5 cut-off point, it was then dropped from the instrument.

| Model | x2 | Δx2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 237.33 | 165 | .96 | .07 | .94 | |

| Three-factor model 1: (pro-disability climate and organizational commitment as one common factor) | 844.23** | 606.9 | 206 | .61 | .19 | .56 |

| Three-factor model 2: (pro-disability climate and Technology as one common Factor) | 797.45** | 560.12 | 206 | .64 | .18 | .59 |

| Three-factor model 3: (FWA and organizational commitment as one common factor) | 828.44** | 591.11 | 206 | .62 | .19 | .57 |

| Three-factor model 4: (FWA and technology as one common factor) | 708.68** | 471.35 | 206 | .69 | .17 | .66 |

| Two-factor model 1: (technology, FWA, and organizational commitment as one common factor) | 976.92** | 739.59 | 209 | .53 | .20 | .48 |

| Two-factor model 2: (pro-disability climate, technology, and organizational commitment as one common factor) | 989.87** | 752.54 | 208 | .52 | .21 | .47 |

| Two-factor model 3: (pro-disability climate, technology, and FWA as one common factor) | 870.34*** | 633.01 | 208 | .59 | .19 | .55 |

| Two-factor model 4: (pro-disability climate, FWA, and organizational commitment as one common factor) | 1001.78** | 728.45 | 208 | .51 | .21 | .46 |

| One-factor model: | 1055.79** | 818.46 | 209 | .48 | .22 | .43 |

CFI = comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis index, RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation.

Δx2is referring to the difference of the respective model to the hypothesized four factor model.

*p < .05.

**p < .01.

In addition to the overall assessment of the model fit, we conducted an item reliability and convergent validity analysis for each construct. The loadings of the items for each construct as well as the composite reliability are presented in Table 3. In Table 3, the first column records the construct names and their measuring items, the second column shows the standardized item loadings for each construct, and the third column presents the average variance extracted (AVE). None of the loadings was less than .50, a cut-off point in factor analysis (Hulland, 1999). We also calculated the composite reliability (Raykov, 1997) and AVE (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) for each construct. The composite reliability assesses the unidimensionality of a construct and should be above the .70 cut-off criterion (Ravkov, 2002). All of the four constructs met this requirement. The AVE estimates the proportion of variance explained in relation to the variance that is due to random error (Bedeian, 2007). All of the four constructs have an AVE of .50 or above, indicating good internal consistency and that the amount of variance captured by each construct is larger than the variance caused by measurement error (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). All results point to the sufficient convergent validity and item reliability of our four latent constructs.

| Constructors and indicators | Standardized Loadings | Composite reliability | Variance extracted estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-disability Climate | .83 | .67 | |

| Item 1 | .66 | ||

| Item 2 | .83 | ||

| Item 3 | .89 | ||

| Item 4 | .87 | ||

| Item 5 | .81 | ||

| Pro-disability Technology | .86 | .72 | |

| Item 1 | .86 | ||

| Item 2 | .74 | ||

| Item 3 | .86 | ||

| Item 4 | .92 | ||

| Flexible Work Arrangement | .73 | .50 | |

| Item 1 | .57 | ||

| Item 2 | .81 | ||

| Item 3 | .91 | ||

| Item 4 | .78 | ||

| Item 5 | .63 | ||

| Item 6 | .69 | ||

| Item 7 | .51 | ||

| Item 8 | .62 | ||

| Item 9 | .70 | ||

| Organizational Commitment | .75 | .75 | |

| Item 1 | .85 | ||

| Item 2 | .86 | ||

| Item 3 | .89 |

Note: N = 86

After testing for the goodness of fit of the measurement model, we examined the structural model. Model fit statistics for both the hypothesized model and alternative model are presented in Table 4. First, we examined the hypothesized model that allows direct as well as indirect effects of organizational pro-disability climate on the other three construct variables (pro-disability technology, FWA, and organizational commitment). The hypothesized model has a good fit (x2 = 273.94, df = 170, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .09, and TLI = .91). When testing the hypothesized model, it turned out that the fourth item measuring organizational commitment had a loading below the 0.5 cut-off point. Thus, it was dropped from the instrument. Next, we assessed the appropriateness of an alternative model, which only allows indirect effects of organizational pro-disability climate on the other three construct variables. The alternative model has slightly better goodness of fit (x2 = 233.74, df = 153, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .08, and TLI = .93).

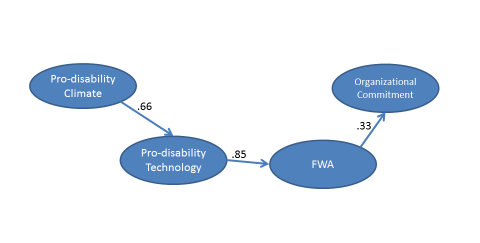

Our first hypothesis indicates that organizational pro-disability climate is positively related to organizational commitment of employees with disabilities. The test results of the hypothesized model indicate that this relationship is not significant (b = .10, p < .5). Our second hypothesis is that organizational pro-disability climate is positively related to the implementation of pro-disability technology. The test results of the hypothesized model show that this relationship is significant (b = .64, p < .01). This positive relationship is also supported by the results of the alternative model (b = .66, p < .01). The third hypothesis suggests that pro-disability technology implementation is positively related to the availability of flexible work arrangement for employees with disabilities. This relationship is significant in both the hypothesized model (b = .78, p < .01) and the alternative model (b = .85, p < .01). The fourth hypothesis indicates that organizational pro-disability climate is positively related to the promotion of flexible work arrangement for employees with disabilities. The test results of the hypothesized model show that the relationship is not significant (b = .07, p < .5). This relationship is absent in the alternative model, as it is a direct effect of organizational pro-disability climate. Finally, the fifth hypothesis suggests that promotion of flexible work arrangements would lead to increased organizational commitment of employees with disabilities. This hypothesis is not supported in the hypothesized model (b = .25, p < .06), but is supported in the alternative model (b = .33, p < .01).

| Structural Model | x2 | Δx2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized model: Direct and indirect effects model | 273.94 | 170 | .94 | .09 | .91 | |

| Alternative model: Indirect effects only model | 233.74 | 153 | .95 | .08 | .93 |

CFI = comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis index, RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation.

Δx2 is referring to the difference of the respective model to the hypothesized four factor model.

The comparison of the two structural models and hypothesis testing results indicate that the alternative model is a better model for the structure of the data of this study. Thus, we adopt the alternative model as our adjusted structural model. Overall, these results suggest that organizational pro-disability climate has direct effect on pro-disability technology implementation, and indirect effects on flexible work arrangement and organizational commitment. In other words, pro-disability technology and flexible work arrangement are two mediators of the relationship between organizational pro-disability climate and organizational commitment of employees with disabilities.

Figure 2: Adjusted Structural Model

Note: Figure 2 illustrates the resulting model. There is a chain effect of pro-diversity climate's direct relationship with pro-diversity technology, and next pro-diversity technology's direct relationship with FWA, and finally FWA's direct relationship with organizational commitment.

Discussion

Estimates suggest that organizations spend billions, perhaps around $8 billion, a year on diversity initiatives (Dipboye & Jayne, 2004; Hansen, 2003). In fact, a recent interview (May, 2015) by USA Today with Google's Vice President of People Operations, Nancy Lee, said the company was committing $150 million in 2015 to these programs. However, there are many arguments suggesting that these initiatives fail to reach their practical or bottom-line goals (e.g., Kochan et al., 2003). One suggestion for this failure is that diversity initiatives find their roots in legal compliance, as opposed to truly valuing the opportunities diversity brings. As organizations are identifying diversity needs, the non-legal needs of these employees are often overlooked, especially as they relate to people with disabilities. Support and socialization needs within the work environment are likely to impact the ability of people with disabilities to integrate and perform with supervisors and coworkers (e.g., Kulkarni & Lengnick-Hall, 2011). In fact, Kochan and colleagues share that the impact of diversity initiatives will only be seen when there is a climate that truly embraces and supports these initiatives. The findings of the current study support this argument.

While we predicted that a pro-disability climate would have a direct effect on the organizational commitment of people with disabilities and the FWA, we found that relationships between pro-disability climate and these constructs are mediated by FWA and pro-disability technology. Taking Kochan and colleagues' (2003) statement and applying it to our findings, it would be easy to see how organizations could overlook the importance of climate on the successful employment of people with disabilities. Many companies are likely to put forth diversity initiatives that may have their roots in compliance, such as pro-disability technology and FWA, without considering whether the climate of the organization is conducive to the success of these initiatives. Our findings suggest that climate is, in fact, important to outcomes for employees with disabilities, but it has an indirect effect. For example, an organization without a pro-disability climate may initiate pro-disability technology and may have available FWA. However, employees with disabilities may not be encouraged to use them by supervisors or may feel shamed for using them by coworkers who perceive these accommodations as "unfair" (e.g., Colella, Paetzold, & Belliveau, 2004). Thus, one of the most important findings of the current study is that pro-disability culture impacts the organizational commitment of employees with disabilities indirectly through the chain effect that includes pro-disability technology and flexible work arrangements.

Another important finding within the current study is that pro-disability climate has a direct effect on the availability of pro-disability technology. Given the explosion of technology in human resource practices, serious questions have been raised about accessibility of web-based platforms used in applying, testing, training, etc. in organizations (e.g., Bruyère, Erickson, & Schramm, 2003). There is a perception by many organizations that making technology accessible is too costly and/or too difficult to accomplish. However, the truth of the matter is that organizations that have a pro-disability climate and a top-down commitment to embracing diversity, have a good awareness that making technology accessible is much less costly and difficult than it may appear. The most frequent adaption is to allow for a wheelchair to fit under a work station, followed by adding screen magnifiers, braille readers, or special computer inputs for mice, keyboards, and voice-recognition software, all relatively inexpensive accommodations. In fact, the use of technology is increasingly making accommodations more reasonable for organizations to provide to employees with disabilities (Bruyère et al., 2003).

Scheduling accommodations are, in fact, made much easier by the use of technology. Our study found that pro-disability technology directly related to the availability and use of FWA. Providing scheduling accommodations for people with disabilities may be the key to providing a supportive, flexible working environment where they can take care of personal and medical needs (National Council on Disability). In addition, a pro-disability climate would support FWA that would aid in the work-life balance and other needs of a diverse workplace, such as women and older workers (e.g., Wittmer & Rudolph, 2014). In other words, the availability and use of FWA through the use of pro-disability technology represents a diversity initiative that could only be supported by an organization with a strong pro-disability climate.

Our findings that FWA directly relates to the organizational commitment of people with disabilities supports the recent governmental, practical, and research support in favor of FWA. For example, the Department of Labor's Job Accommodation Network (2010) recommends a variety of FWA for over 80% of the impairments they have documented. The Office of Personnel Management and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission suggest FWA as accommodations for individuals with disabilities. The US Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration provides employer and employee guidance related to diverse workplace flexibility needs of people with mental illness. The American Cancer Society, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, The National Mental Health Association, United Cerebral Palsy, and the United Spinal Association promote FWA for their members (National Organization on Disability, 2004). National organizations advocating for the private sector also have spoken out about the benefits of FWA; Institute for a Competitive Workforce (2008) promotes FWA as a method for businesses to attract and retain workers with disabilities. Organizations that allow for flexible scheduling and work arrangements for their employees, allow a low-cost method of creating positive social exchange and building commitment in people with disabilities.

Research and Human Resource Implications

The current study is an initial attempt to examine the relationships between important organization-level constructs and the organizational commitment of people with disabilities. The findings establish that there are unique relationships between pro-disability climate, pro-disability technology, and FWA and their impacts on organizational commitment. Given that the current study examines large organizations at an organizational-level, the findings suggest that these phenomena and relationships are consistent across industry and region, which speaks to the robust nature of our results. The results of the current study illustrate the importance, in research, of examining potential alternative models, given that some of our initial assumptions of the relationships between the variables were better represented and explained in an alternate way. These alternate explanations are especially important when we consider how organizations may apply their assumptions of how individual and organization-level phenomenon work.

There are some important organization and human resource implications that can be drawn from the current study's findings. Specifically, the current study illustrates the importance of considering the organization's climate with developing human resource initiatives in the organization. Anecdotally, human resource practitioners share that many expensive initiatives, diversity related or not, fail to reach their intended outcome. Organizations spend billions of dollars on technology, training, consultants, etc., but fail to reach performance expectation or a return on investment. Organizational change initiatives and training initiatives, again, whether diversity-related or not, do not come to fruition because the work environment and climate do not support the change or training (e.g., Bunch, 2007). Given the high investment in time, money, and effort, in implementing technology and other HR practices and benefits, such as FWA, it is essential that human resource practitioners and other organizational leaders consider whether the climate of the organization supports such an investment. If this is not the case, these leaders need to work towards shifting the climate towards a pro-disability climate before making such investments.

Additionally, human resource practitioners can take from these findings that the investments made towards providing advanced accommodations and flexible work arrangements do, in fact, have an impact on the organizational commitment of people with disabilities. Thus, in terms of justifying additional investments, human resource practitioners can feel more confident in suggesting that technology and FWA may not only have an impact on being able to provide legal, or compliant, reasonable accommodations, but may also aid in the recruitment and retention of people with disabilities. Lastly, given the current sample likely represents organizations that are at the forefront of diversity initiatives, with the majority being large, Fortune 500 organizations, it is possible that other organizations may allow these findings to serve as an example of best practices in providing a working environment for the successful employment of people with disabilities.

Limitations and Future Research

While the current study has the advantage of examining a sample of large organizations, with the majority being Fortune 500 companies, there still remain a few limitations that should be addressed through future research. The first limitation is the generalizability to smaller or midsized organizations. The organizations studied have a greater number of resources in terms of capital, but also HR. While most of the research supports the idea that technological accommodations are not costly (Bruyère et al., 2003), one could argue that a smaller organization may not be able to provide the same type of technology, or even the same types of FWA, that larger organizations can. Thus, it would be important to examine how these relationships exist in smaller organizations. The dynamics of pro-disability climate may change in a smaller organization, as communication and access to top-level leaders by employees is different. Also, smaller organizations may have more flexibility, being less bureaucratic with fewer human resource rules and policies to follow in terms of working arrangements. However, on the other hand, smaller organizations may not be able to provide as much workplace flexibility with fewer people and coverage for job responsibilities on-site.

An additional limitation is that our measure of organizational commitment, while following Klein et al. (2013), was collected via proxy and not from the individual employees. Our data were collected from HR practitioners who were taking into account actual organizational data collected from such things as exit interviews and employee opinion surveys. Given the caliber and expertise of the HR professionals completing the survey and the general impossibility of collecting data from individual employees at eighty-six different, large organizations, we feel confident with our results. However, future research should certainly attempt to collect individual-level data.

While we chose to examine organizational commitment, due to its relation to employee turnover/retention and the important social issue of the underemployment of people with disabilities, there are certainly other outcomes that are of interest. For example, other issues surrounding FWA, such as psychological involvement in work or job satisfaction are important. Previous research suggests come poorer individual outcomes when employee telecommute (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007) because they feel less included and socialized with the organization. Given previous research findings that people with disabilities feeling less included socially in the organization (Colella, 1994), it would be important to understand if FWA, such as telecommuting, would compound this lowered inclusion and how that might impact psychological involvement in work.

Taken as a whole, the current study's findings suggest that a pro-disability climate and initiatives supporting accommodations for people with disabilities will support their increased organizational commitment and tenure with an organization. Given the fact that organizations are just beginning to realize the benefits of hiring people with disabilities and their ability to solve predicted labor shortages (e.g., Lengnick-Hall, Gaunt, & Kulkarni, 2008), it is essential that human resource practitioners and organizations come together to create a working environment to promote their continued success and growth within the workforce.

References

- Ashforth, B. (1985). Climate formation: Issues and extensions. Academy of Management Review, 10, 837-847.

- Askenazy, P., & Caroli, E. (2010). Innovative work practices, information technologies, and working conditions: Evidence for France. Industrial Relations, 49 (4), 544-565. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2010.00616.x

- Baer, M., & Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: Climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(1), 45-68. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.179

- Baumgartner, M. K., Dwertmann, D. J. G., Boehm, S. A., & Bruch, H. (2015). Job satisfaction of employees with disabilities: The role of perceived structural flexibility. Human Resource Management, 54 (2), 323-343. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21673

- Bedeian, A. G. (2007). Even if the tower is 'ivory', it isn't 'white': Understanding the consequences of faculty cynicism. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 6, 9–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2007.24401700

- Beetham, H., & Sharpe, R. (2007). An introduction to rethinking pedagogy for a digital age. In H. Beetham & R. Sharpe (Eds.), Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age: Designing and delivering e-learning, 15. London: Routledge.

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fi t indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Bruyère, S. M. D., Erickson, W., & Schramm, J. (2003). Disability in a technology-driven workplace. Employment and Disability Institute Collection, 1211.

- Bruyère, S. M., Erickson, W., & VanLooy, S. (2006). Information technology (UT) accessibility: Implications for employment of people with disabilities. Work, 27, 397-405.

- Bunch, K. J. (2007). Training failure as a consequence of organizational culture. Human Resource Development Review, 6(2), 142-163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484307299273

- Caillier, J. G. (2013). Satisfaction with work-life benefits and organizational commitment/job involvement: Is there a connection? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 33 (4), 340-364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X12443266

- Casper, W. J., & Buffardi, L. C. (2004). The impact of work/life benefits and perceived organizational support on job pursuit intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 391–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.09.003

- Casper, W. J., & Harris, C. M. (2008). Work-life benefits and organizational attachment: Self-interest utility and signalling theory models. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72, 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.10.015

- Chen, X., Liu, D., & Portnoy, R. (2011). A multilevel investigation of motivational cultural intelligence, organizational diversity climate, and cultural sales: Evidence from U.S. real estate firms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97 (1), 93-106. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024697

- Colella, A. (1994). Organizational socialization of employees with disabilities: Critical issues and implications for workplace interventions. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 4(2), 87-106. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02110048

- Colella, A., Paetzold, R., & Belliveau, M. A. (2004). Factors affecting coworkers' procedural justice inferences of the workplace accommodations of employees with disabilities. Personnel Psychology, 57(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02482.x

- Colella, A., & Stone, D. L. (2005). Workplace discrimination toward persons with disabilities: A call for some new research directions. Discrimination at work: The psychological and organizational bases, 227-253.

- Cooper-Hakim, A., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). The construct of work commitment: Testing an integrative framework. Psychological Bulletin, 131: 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.241

- Crowne, K. A., Cochran, J. & Carpenter, C. E. (2014). Older-worker-friendly policies and affective organizational commitment. Organization Management Journal, 11(2), 62-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15416518.2014.925389

- de Sivatte, I., & Guadamillas, F. (2013). Antecedents and outcomes of implementing flexibility policies in organizations. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24 (7), 1327-1345. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.561225

- Denison, D. (1996). What is the difference between organizational culture and organizational climate? A narrative's point of view on a decade of paradigm wars. Academy of Management Review, 21(3), 619-654.

- Department of Labor's Job Accommodation Network (2010) WF2010 analysis of the fact sheet series compiled by the Job Accommodation Network, at https://www.dol.gov/odep/resources/jan.htm.

- Dikkers, J. S. E., Geurts, S. A. E., Den Dulk, L., Peper, B., Taris, T. W., & Kompier, M. A. J. (2007). Dimensions of work-home culture and their relations with the use of work-home arrangements and work-home interaction. Work and Stress, 21, 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370701442190

- Dipboye, R.L., & Jayne, M.E.A. (2004) Leveraging Diversity to Improve Business Performance: Research Findings and Recommendations for Organizations. Human Resource Management, 43(4), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20033

- Erickson, W. von Schrader, S. Bruyère, S & VanLooy, S. (2013). The Employment Environment: Employer Perspectives, Policies, and Practices Regarding the Employment of Persons with Disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. Published online before print November 14, 2013.

- Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (1), 42-51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

- Flinders, K. (2012). What's holding up flexible working? Computer Weekly, April 3-9, 14-15.

- Florey, A. T., & Harrison, D. A. (2000). Responses to informal accommodation requests from employees with disabilities: Multistudy evidence on willingness to comply. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (2), 224-233. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556379

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural Equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524

- Glick, W. H. (1988). Response: Organizations are not central tendencies: Shadowboxing in the dark, round 2. Academy of Management Review, 13(1), 133-137.

- Goncalves, R., Martins, J., Pereira, J., Oliveira, M. A., & Ferreira, J. J. P. (2013). Enterprise web accessibility levels amongst the Forbes 250: Where art thou o virtuous leader? Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 363-375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1309-3

- Gonzalez, J. A., & DeNisi, A. S. (2009). Cross-level effects of demography and diversity climate on organizational attachment and firm effectiveness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.498

- Haar, J.M., & Spell, C.S. (2004). Programme knowledge and value of work-family practices and organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15, 1040–1055. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190410001677304

- Hansen, F., (2003). Diversity's Business Case Doesn't Add Up. Workforce Management, April, 2003, p.28-32.

- Herrback, O., Mignonac, K., Vandenberghe, C., & Negrini, A. (2009). Perceived HRM practices, organizational commitment, and voluntary early retirement among late-career managers. Human Resource Management, 48 (6), 895-915. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20321

- Hicks-Clarke, D., & Iles, P. (2000). Climate for diversity and its effects on career and organizational attitudes and perceptions. Personnel Review, 29 (3), 324-345. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480010324689

- Hornung, S., & Rousseau, D. M. (2008). Creating flexible work arrangements through idiosyncratic deals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93 (3), 655-664. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.655

- Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::AID-SMJ13>3.0.CO;2-7

- Hyland, M. M., Rowsome, C., & Rowsome, E. (2005). The integrative effects of flexible work arrangements and preferences for segmenting or integrating work and home roles. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 141-160.

- Hyland, P. K., & Rutigliano, P. J. (2013). Eradicating discrimination: Identifying and removing workplace barriers for employees with disabilities. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 6 (4), 471-475. https://doi.org/10.1111/iops.12087

- Institute for a Competitive Workforce, an Affiliate of U.S. Chamber of Commerce. (2008) Workplace Flexibility: Employers Respond to the Changing Workforce, available at http://www.ncwd-youth.info/node/118.

- James, L. R. (1982). Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(2), 219. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.67.2.219

- Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63 (1), 83-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709349199

- Kent, M. (2015). Disability and eLearning: Opportunities and Barriers. Disability Studies Quarterly, 35(1). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i1.3815

- Kochan, T., Bezrukova, K. Ely, R., Jackson, S., Joshi, A., Jehn, K., Leonard, J., Levine, D., & Thomas, D. (2003) The effects of diversity on business performance: Report of the diversity research network. Human Resource Management, 42(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.10061

- Kossek, E.E., Barber, A.E., & Winters, D. (1999). Using flexible schedules in the managerial world: The power of peers. Human Resource Management, 38, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(199921)38:1<33::AID-HRM4>3.0.CO;2-H

- Kulkarni, M., & Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Socialization of people with disabilities in the workplace. Human Resource Management, 50(4), 521-540. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20436

- Lengnick-Hall, M. L., Gaunt, P. M., & Kulkarni, M. (2008). Overlooked and underutilized: People with disabilities are an untapped human resource. Human Resource Management, 47(2), 255-273. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20211

- Leslie, L. M., Park, T., & Mehng, S. A. (2012). Flexible work practices: A source of career premiums or penalties? Journal of Management Journal, 55 (6), 1407-1428. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0651

- Malone, E. K., & Issa, R. R. A. (2014). Predictive models for work-life balance and organizational commitment of women in the U.S. construction industry. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 140(3). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000809

- Martin, B. H., & MacDonnell, R. (2012). Is telework effective for organizations? A meta-analysis of empirical research on perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes. Management Research Review, 35 (7), 602-616. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171211238820

- Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108: 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.171

- Matt, S. & Butterfield, P. (2006). Changing the disability climate: Promoting tolerance in the workplace. AAOHN Journal, 54(3), 129-133.

- McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., & Morris, M. A. (2008). Mean racial-ethnic differences in employee sales performance: The moderating role of diversity climate. Personnel Psychology, 61, 349–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00116.x

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research and application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61: 20–52. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

- Michielsens, E., Bingham, C., & Clarke, L. (2014). Managing diversity through flexible work arrangements: Management perspectives. Employee Relations, 36 (1), 49-69. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-06-2012-0048

- Mowday, R. T., Porter, L.M., & Steers, R. M. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior 14, 224–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1

- National Organization on Disability. (2004, June).

- Nishii, L., &, Bruyère S. (2013). Inside the workplace: Case Studies of Factors Influencing Engagement of People with Disabilities. A research brief to summarize a presentation for a state of the science conference entitled Innovative Research on Employment Practices: Improving Employment for People with Disabilities held October 22-23, 2013 in Crystal City, MD.

- Park, E., & Nam, S. (2014). An analysis of the digital literacy of people with disabilities in Korea: Verification of a moderating effect of gender, education, and age. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38, 404-411. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12107

- Ratliffe, K. T., Rao, K., Skouge, J. R., & Peter, J. (2012). Navigating the currents of change: Technology, inclusion, and access for people with disabilities in the Pacific. Information Technology for Development, 18 (3), 209-225. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2011.643207

- Raykov, T. (1997). Estimation of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Applied Psychological Measurement, 21, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/01466216970212006

- Reichers, A. E., & Schneider, B. (1990). Climate and culture: An evolution of constructs. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 5–39). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Riketta, M. (2002). Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(3), May 2002, 257-266. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.141

- Rodgers, C. S. (1992). The flexible workplace: What have we learned? Human Resource Management, 3, 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930310305

- Rousseau, D. M. (2001). Schema, promise and mutuality: The building blocks of the psychological contract. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74, 511–541. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317901167505

- Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40: 437-453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1987.tb00609.x

- Schneider, B. (1990). Organizational climate and culture: Pfeiffer. New York, NY.

- Schneider, B., & Reichers, A. E. (1983). On the etiology of climates. Personnel Psychology, 36, 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1983.tb00500.x

- Schneider, B., Ehrhart, M. G., & Macey, W. H. (2011). Perspectives on organizational climate and culture. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 373–414). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/12169-012

- Shinohara, K., & Tenenberg, J. (2009). A blind person's interactions with technology. Communications of ACM, 52, 58-66. https://doi.org/10.1145/1536616.1536636

- Society for Human Resource Management. (2012). Employing People with Disabilities: Practices and Policies Related to Recruiting and Hiring Employees with Disabilities. In collaboration with and commissioned by Cornell University ILR School Employment and Disability Institute.

- Shur, L., Kruse, D., & Blanck, P. (2005). Corporate culture and the employment of persons with disabilities. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 23, 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.624

- Thompson, C. A., Beauvais, L. L., & Lyness, K. S. (1999). When work-family benefits are not enough: The influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 391–415. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1681

- U.S. Department of Commerce. (2000). Falling through the Net: Toward digital inclusion. Washington: U.S. Department of Commerce.

- Vicente, M. R., & Lopez, A. J. (2010). A multidimensional analysis of the disability digital divide: Some evidence for the Internet use. The Information Society, 26, 48-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/01615440903423245

- von Schrader, S., Malzer, V., Bruyère , S. (2013). Perspectives on disability disclosure: The importance of employer practices and workplace climate. Employer Responsibilities and Rights Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-013-9227-9

- When Work Works (2012). Workflex: Employee Toolkit created jointly by the Families and Work Institute and Society for Human Resource Management.

- Wittmer, J. L. S., & Rudolph, C. W. (2014). The Impact of Diversity on Career Transitions over the Life Course. In Hughes, C. (Ed.) Impact of Diversity on Organization and Career Development, IGI Global, pp. (151-185).

- Wittmer, J. L. S., & Wilson, L. (2010, February). Turning Diversity into Dollars: A Business Case for Hiring People with Disabilities. Training & Development, 58-61.

- Zammuto, R. F., Griffith, T. L., Majchrzak, A., Dougherty, D. J., & Faraj, S. (2007). Information technology and the changing fabric of organization. Organization Science, 18 (5), 749-762. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0307