In this article we offer a number of empirical examples to argue that educational practices designed to provide children labeled with disabilities with a free and appropriate public education can lead to an experience of "containment." Drawing upon data from two science projects conducted with children labeled with disabilities in an elementary school in the United States we explore adults' and children's experiences of contesting containment in a special education classroom, alongside a concomitant desire to cultivate competence. Based on the work of Foucault (1977) we suggest that children with labels face a number of containment strategies including: exclusion and classification (categorizing and placing children in segregated classrooms with an alternative curriculum); individualization (Individual Education Plans); examination and assessment (measuring children's attainment against predetermined goals and tests); and control (the regulation and self-regulation of children's bodies and behaviors). Notwithstanding these disabling constraints, it is possible to move towards an approach informed by Disability Studies in Education (DSE), in which competence is cultivated through more inclusive strategies. These include positioning children as abled rather than labeled through taking a Universal Design approach to Learning (UDL); recognizing children's multimodal communicative practices; constructing learning stories as a narrative form of pedagogical documentation and assessment; valorizing the ways in which children contest containment and control through their bodily actions and child-initiated narratives; and respecting children's autonomy in the learning process.

Today many students with disabilities in the U.S. education system continue to be placed in special schools and self-contained classrooms and denied access to the general curriculum (Baglieri et al, 2011; Lalvani, 2013; Ryndak et al., 2014). This is in spite of the right afforded by the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, 1975, (now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act [IDEIA], 2004) for all students to receive a "free and appropriate education" in the "least restrictive environment" (LRE) alongside their non-disabled peers. Disability scholars argue that interpretations of LRE have led to a continuum of placements from the least restrictive (full inclusion) to the most restrictive (self-contained) and legitimized the dual bureaucracies of "general education" and "special education" (Skrtic, 1995). All too often this has led to the segregation of disabled students from their grade-level general education contexts, grade-level peers, and grade-level curriculum content (Ryndak et al., 2014).

In this article we document adults' and children's experiences of contesting containment in special education classrooms alongside pedagogical approaches that foster the cultivation of children's competence. The data reported here was generated as a result of a year-long collaboration between a school and university researchers in which the shared aim was to facilitate access to the general science curriculum for students with moderate and mild intellectual disabilities. Two projects were conducted in three special education classrooms of an elementary school in the Midwest region of the U.S. The purpose of the two projects was to contest the deficit-based assumption that students labeled with intellectual disabilities are unable to handle the content of academic subjects such as science and mathematics. This is critical because many schools serving children labeled with disabilities emphasize a functional curriculum that focuses simply on daily living skills alongside basic reading and writing, thereby denying them access to the wider general curriculum (Trela and Jimenez, 2013). Working from a strengths-based perspective and informed by socio-cultural theories (Vygotsky, 1978; 1987; Smith, 2002; Woodhead, 2005; Connor & Valle, 2015), we wanted to recognize that children are not simply passive recipients of curriculum but are active co-constructors of learning. Thus, our aim was to highlight what students were doing, as opposed to what they did not do, as well as what we could do as educators to cultivate their competence further.

Notions of Containment and Competence

We offer a number of empirical examples to argue that educational practices designed to provide children labeled with disabilities with a free and appropriate public education can lead to an experience of containment. Notwithstanding these constraints, it is possible to move towards an approach in which children's competence is cultivated through more inclusive strategies. In order to examine the meaning of these concepts of containment and competence, particularly as they relate to children labeled with disabilities, we draw upon social and psychological theory.

Containment

"Containment"' is often used in relation to: a) the containment of a disease - the action of keeping something harmful under control, and b) the self-contained person – someone who is in control of the body, and by extension, of the 'self' (Shildrick, 1997). As the French social theorist and historian Foucault (1967, 1977) argued, from the nineteenth century onwards, certain social groups have been subject to strategies of containment and regulation on account of their "abnormalities." The "birth of the clinic" (Foucault, 1973) led to an understanding of disability as a medical pathology to be treated and corrected (Connor & Valle, 2015). Consequently, people with disabilities were contained within segregated spaces and denied access to mainstream culture (Baglieri, Bejoian, Broderick, Connor & Valle, 2011; Hughes, 2013). Nowadays, segregated education such as self-contained classrooms within public schools can be viewed as spaces for the containment of difference, with consequences for children's access to peer-group cultures and academic opportunities (Holt, 2004; Valle, Connor and Reid, 2006).

In Foucault's (1977) sense of disciplinary power, certain containment or "dividing practices" separate those who are "normal" (i.e. who fit into dominant institutions and ways of behaving) from those who are not. This is to maintain order and discipline. Ball (1990; 2013) argues that dividing practices are central to the organizational processes of education in our society through modes of classification, containment and control.

Differentiating and labeling children with disabilities from those without is classification. This sets up a binary (paired) opposition of able/disabled children, which in turn produces the dualism of general education and special education. Indeed, commenting upon Foucault, Rabinow (1984) suggests that these dividing practices are methods of manipulation that combine the mediation of science with the practice of exclusion. Thus, children found to be incompetent on the basis of medical and/or psychological assessments are placed into disability categories and provided with special education services (Gresham, 1986).

Containment can be seen through segregated facilities such as self-contained classrooms with strong spatial boundaries, which can be physical, social and curricular in nature. As Valle, Connor and Reid (2006) argue, the practice of containing labeled students within particular spaces renders them invisible to others and can lead to silencing, low expectations and a watered-down curriculum.

Finally, control can be seen in the monitoring, regulation and training of children's bodies to be useful and docile. Shallwani (2010) argues that this is evident in the dominant educational discourse of child development and its associated practices. For example, children's development needs careful monitoring against predetermined goals, educational standards and Individual Education Plans (IEPs). Their time and use of space requires regulation in order to function according to the prescribed timetables and routines of the school. Lastly, their bodies have to be trained to behave in particular ways, such as holding a pencil "correctly" or not running indoors. In this way, teachers and paraprofessionals are expected to closely observe and intervene to make the child's body useful and docile.

Foucault suggests that disciplinary power not only contains bodies and behaviors through external techniques but also through internal self-regulation – hence the notion of the 'self-contained' individual. In other words, the self is complicit in disciplining the self (Foucault, 1992). However, whilst this process of self-subjectification could be seen as insidious, the ability to regulate and conduct oneself can also form the basis of autonomy and self-realization (Prout, 2000). Thus, children labeled with disabilities, as well as teachers of special education, may be subject to control and self-regulation, whilst also acting as subjects with agency: contesting containment and demonstrating competence.

Competence

Due to the hegemony of developmental psychology and theories of socialization competence has tended to be seen as age- or stage- related (Christensen & Prout, 2002; Morrow, 2005). The older or more independent a child is, the more competent they are assumed to be. Conversely, the younger and more dependent a child is, the more incomplete or incompetent they are assumed to be. Competence, or lack of it, is therefore viewed as an essential attribute that resides within the individual based on his/her age and stage of development. However, sociocultural psychologists and scholars from the 'new social studies' of childhood have contested this view. Rather than focusing on in/competence as fixed within each individual based on their age or level of dis/ability, they argue that competence is an intrinsically contextual matter (Vygotsky, 1978; Donaldson, 1978; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Hutchby & Moran-Ellis, 1998, Harry, Rueda & Kalyanpur, 1999; Lee, 2001; Hogan, 2005; Prout, 2005; Woodhead 2005). Competence arises through a combination of experience, cultural contexts and relationships (Smith, 2002). Lee (2001) argues that both children and adults are all incomplete and dependent upon one another and that we need to recognize the existence of dependencies within competence. Moreover, children and adults can be moved in and out of competence as a consequence of the social contexts and resources available to them.

Similarly, scholars from the field of Disability Studies in Education (DSE) argue that notions of disability and incompetence are not innate, static attributes of an individual, rather they are socially constructed facets of identity and experience (Connor et al., 2008; Broderick et al., 2012). They suggest that the hegemonic discourse of special education has led to a dominant narrative in which disability is located within students themselves rather than within the disabling structures of the learning environment and its interaction with student characteristics. Thus, students with disabilities are assumed to need the help of specially trained teachers who are able to implement a variety of 'evidence-based strategies' to remediate within-child incompetences. As Allan (2012) points out, "the notion of competence, and its plural 'competences', has, in recent years, been replaced by the narrower version of 'competency', or the plural form 'competencies', denoting discrete skills and activities which individuals can perform" (p.17). Indeed, functional skills instruction and IEPs aim to foster such competencies in children labeled with disabilities. However, from a DSE and sociocultural perspective, provision of the IEP should not be at the expense of enabling students' access to the wider curriculum and to social contexts and cultural tools where their competence is both recognized and developed through guided participation in meaningful activities with others (Rogoff, 1990; Cowie & Carr, 2009).

Methodology

Our Positionality

Rama Cousik. I initially trained as a special education teacher in India and learned about Disability Studies (Gleeson, 1997; Davis, 1999; Danforth & Gabel, 2006) after coming to the U.S. Since then, I have been critically examining the special education system that seems to promote the ableist perspective (Hehir, 2002) in which categories take precedence over children's autonomy. I agree with the social model perspective of disability (Broderick et al, 2012), which argues that by suitably changing conditions in the environment, children are no longer constrained and actively participate in their learning. My role in this project has been to design and implement the two projects that provided data for this paper with a co-investigator, as well as to undertake data analysis and reporting.

Heloise Maconochie. My positionality is informed by the interdisciplinary fields of Childhood Studies and Disability Studies (for example, James, Jenks & Prout, 1998; Prout, 2005; Corsaro, 2011; Goodley 2011; Curran & Runswick-Cole, 2013). In both fields children are seen as active agents, and not simply as passive recipients, of social and educational processes. Children's views and perspectives are actively sought and there is acknowledgement that children shape and are shaped by the cultural, social, economic, political, structural and historical contexts they find themselves in. With regards to this particular project my involvement has been at the data analysis and reporting stages of the research.

This paper draws on two classroom science projects. The methodological approach in this paper was informed by a DSE perspective (Gabel, 2005; Danforth & Gabel, 2006) in which narratives of children's classroom and learning experiences came to the fore. As Connor (2009) suggests, narrative forms of knowledge can act as counter stories to traditional special education research which is often located within a medical model paradigm that casts students as deficit-based (For the types of methods used in special education research, see Brantlinger, Jimenez, Klingner, Pugach, & Richardson, 2005; Odom, Brantlinger, Gersten, Horner,Thompson & Harris, 2005). Qualitative, ethnographic methods were used to document children's participation in the general science curriculum, their development of scientific understanding and their experiences of disability in schooling. Data collection methods included narrative observations, fieldwork notes by the first author, children's drawings, staff journal entries and semi-structured interviews, and the construction and analysis of learning stories (Carr, 2001). Field notes and narrative observations helped researcher reflexivity and analysis, and in interpretation of other data. These also enabled us to ascribe meanings to actions by participants and researchers.

Description of the Two Projects

During a professional development session, special education teachers in a local elementary school expressed a need for and interest in teaching science lessons in their classrooms. Prior to the implementation of the two projects, the teachers followed a special education curriculum that was based on their students' IEP goals and objectives which included functional skills such as personal skills, cooking, art and functional academics. Children also received related services such as physical and occupational therapy and speech and language therapy, based on their individual needs. Teaching was mostly conducted individually or in small groups.

Based on their interest in teaching gardening to their students, two university researchers implemented two projects. The first project provided an opportunity for university researchers, teachers, paraeducators and children to work and learn together. The teachers requested that the university researchers play a major role in planning and implementing the project. The project helped develop a shared understanding of the dynamics of the special education classrooms, children's interests and curriculum adopted. Based on the experiences and understanding gained from the first project, a second project was designed and developed. This time, it was initiated by one of the three special teachers who had participated in the first project, who requested the researcher to demonstrate a model science lesson in her classroom. After examining the extant literature on lesson planning and curriculum for children with disabilities, it was decided that an approach based on the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) was suitable for the purpose of demonstration because the approach allowed children autonomy in expression of knowledge in a variety of ways.

Three special educators and 25 students from three classrooms participated in the first study and students, teachers and paraeducators from one of those three classes participated in the second study. The two projects are described below.

All ethical guidelines required by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the university were followed in maintaining confidentiality, informing participants of the benefits and risks, and voluntary nature of their participation. Informed consent was obtained from parents, children and educators. Additionally, we sought to root the ethical regulations of the IRB within a "value-oriented strategy" of "ethical symmetry" in which the "rights, feelings and interests of children… [were given] as much consideration as those of adults" (Christensen & Prout 2002, p. 492-493) throughout the research process.

Study #1

Participants.

Three special education teachers and 25 students from three special education classes in a local elementary school participated in this study in Spring 2014. There were 23 male and two female students from ages ranging from 9-12 years. The students in the three classrooms were diagnosed with moderate to mild developmental disabilities including autism, emotional disorders, learning disability, and intellectual disability.

Materials and Procedure.

The goal of the study was to teach students how to grow tomatoes and other vegetables indoors since we were interested in learning about the outcomes of students participating in a hands-on, inquiry based learning process. The teachers were provided with a storybook about how to grow plants indoors. The storybook had pictures of each stage in the plant growth. The sentences were short and simple. The story contained vocabulary words that teachers could test students on after completion of the project. All materials needed to implement the lesson were provided. This included, pots, frames to hold the pots, seeds, soil, plant food, grow lights, albums for students to collect data, a camera, vocabulary test sheets and flash cards. The study was implemented for four months. Data for this study included pre and post vocabulary tests, teacher journals of students' communication and interaction with the project materials such as plants, seeds and soil.

Study #2

Participants.

The participants for the second project included one special education teacher, two paraeducators and eleven students with disabilities. The children had a range of impairment labels including intellectual disability, autism, Attention Deficit Disorder and learning disability. Data for this study included vocabulary tests conducted by the researchers before, during and after the implementation of the UDL lesson, anecdotal records of children's comments, researcher observational narratives, children's drawings and writings, and teacher and paraeducator interviews.

Procedure.

Having built a trusting relationship with the school over a period of one year, the second project was conceptualized when one of the special education teachers who participated in the first project invited Rama to conduct another study in her class. The teacher wanted to know if she could demonstrate another science lesson in her class as a model that she and her paraeducators could observe, reflect on and learn from. A UDL-based approach to conceptualize the lesson appeared apt for the purpose (cast.org). UDL is based on the premise that learning experiences should be designed to be universal, that is, to meet the needs of a diverse group of learners rather making ongoing adjustments for individual students labeled with special needs. Thus, in UDL inclusion is addressed at the design stage, rather than accommodations added as an afterthought (Feldman, Battin, Shaw & Luckasson, 2013). The first author of this paper and the special education teacher collaboratively developed a new science series titled "Life-cycle of an Apple," with goals drawn from state science standards for K-2 grades. This study was conducted in Fall 2014. The first author taught the opening lesson using a variety of learning materials such as books, audio-video and hands on activities, music, games and arts and crafts, and students were allowed to demonstrate their learning in multiple ways-by writing, drawing, through verbal expression, singing, pointing to or showing an object that represented the topic and by using letter tiles to spell vocabulary words. The teacher, paraeducators and university researchers collaboratively supervised various activities that students were involved in during the lesson. Students had several opportunities to practice what they learned from the lesson in other settings. For example, the teacher noted that students connected a recent visit to an apple orchard with the science lesson and during a cooking activity, they were able to connect apple with apple pie.

Data Analysis

Analysis occurred during and after the data generation phase. Thus, analysis occurred "in the field" during the interpretative process of meaning-making as teachers and university faculty constructed learning stories, journal entries and research memos. It also happened later when the audio recordings of teachers' and paraeducators' interviews were transcribed and when we examined journals of teachers' and children's narratives and applied thematic analysis (Braun & Clark, 2006) to the entire data set. Through a process of abductive reasoning, codes and then broader themes were constructed both inductively from the data and deductively from theoretical literature. Rather than claim that this project is generalizable to other settings the criteria we employed to address issues of rigor were Lincoln and Guba's (1985) notions of transferability, credibility and dependability.

Findings and Discussion

Exclusion and Classification

IDEA (2004) requires teachers to adopt the UDL model for instruction, and in tandem with the No Child Left Behind Act (2001), mandated access to general education for students with disabilities. Schools vary in determining the extent of access to general education. Some adopt the full inclusion model where there are no self-contained, special education classes and others have special education classes based on disability classification. In the school where the research was conducted there continued to be a focus on teaching functional skills to students labeled with mild, moderate and severe disabilities in self-contained classrooms. Thus students were segregated and excluded from their peers. Furthermore students were denied full access to the general education curriculum and instead expected to learn from a curriculum designed on the basis of their disability label and an assessment of their strengths and weaknesses as documented in their IEP.

The classification of disability labels is usually a result of a failure of the individual to measure up to the normative standards. In other words,

Labels take birth when inquirers begin to look for problems. For example, most teachers routinely "screen" their students for negative behaviors that disrupt the flow of teaching and learning. When they find that some students are significantly different from the rest of the class (in terms of academic performance), such students are referred for special education. Subsequently, these children re-enter the classroom with new, negative identities… (Cousik, 2012, p. 33).

The IEP contains goals and objectives that are usually adaptations and modifications of goals from the general education curriculum, or depending on the severity of the disability, they may be just functional goals that focus on teaching life skills and daily living skills. In this case, the students' IEPs focused primarily on functional living skills alongside goals in basic reading, writing and math, modified from the general education curriculum. According to Morton (2012), "IEPs have become the default curriculum for some students, rather than a space for considering how well educators are doing to ensure students have access to and participate in the curriculum." The IEP can pose a restriction on children's access to regular education, and its very individualized nature can deny children the opportunity to co-construct knowledge with peers and teachers.

As one paraeducator who participated in both the studies remarked, "Our children don't do what they do in the hallway! Those children [children in general education classrooms] take part in science fair every year. This year they got butterfly kits. They watch them grow. Our kids don't get to do that. We don't participate."

Wehmeyer, Lattin, Lapp-Rincker and Agran (2003) observed children with intellectual disabilities in both general education and special education settings and found that the children did not have complete access to the general education curriculum. However, the UDL method promises to eliminate this barrier. For these reasons, as a research team of university faculty, school teachers and paraeducators we sought to question the deficit-based, functional curriculum imposed by the IEP and instead implemented a UDL curriculum that was structured in a way as to provide access to all children. Courtade, Browder, Spooner, & DiBiase (2010) have demonstrated the effectiveness of inquiry based approaches to provide access to general education for children with intellectual disabilities and similarly, we demonstrate that it is indeed possible that the IEP in conjunction with a UDL approach, can open up the world of general education curriculum to children in contained special education settings.

There were several advantages inherent in taking a Universal Design approach to learning. UDL allowed teachers to embed cross-curricular content into their lessons which tapped into students' prior experiences, strengths and interests; students could choose from a variety of simple and straightforward materials that everyone could use regardless of impairment; students' multimodal communicative preferences were valued as legitimate means of expressing their understanding – linguistic, visual, audio, gestural and spatial; students were also encouraged to take action based on their scientific theorizing; finally, children's learning was evaluated on the basis of qualitative, substantive intentions instead of being evaluated on normalization principles and projected as having failed to measure up to those standards.

For example, a student Stephen demonstrates his ability to access general education curriculum through the UDL lesson, which eliminates the contextual and curricular barriers that segregated settings create (Ryndak, Taub, Jorgensen, Gonsier-Gerdin, Arndt, Sauer, & Allcock, 2014).

Fig 1: A list of vocabulary words written by Stephen (Apple, Seed, Seedling, Tree, Bud, Flower, Fruit, Green, Red, Trunk, Coore (core), Stem, Roots)

Stephen demonstrates his ability to learn and write words drawn from standards-based science lesson, instead of routinely copying "functional words" which is common practice within the curriculum for children with developmental disabilities in special education classes.

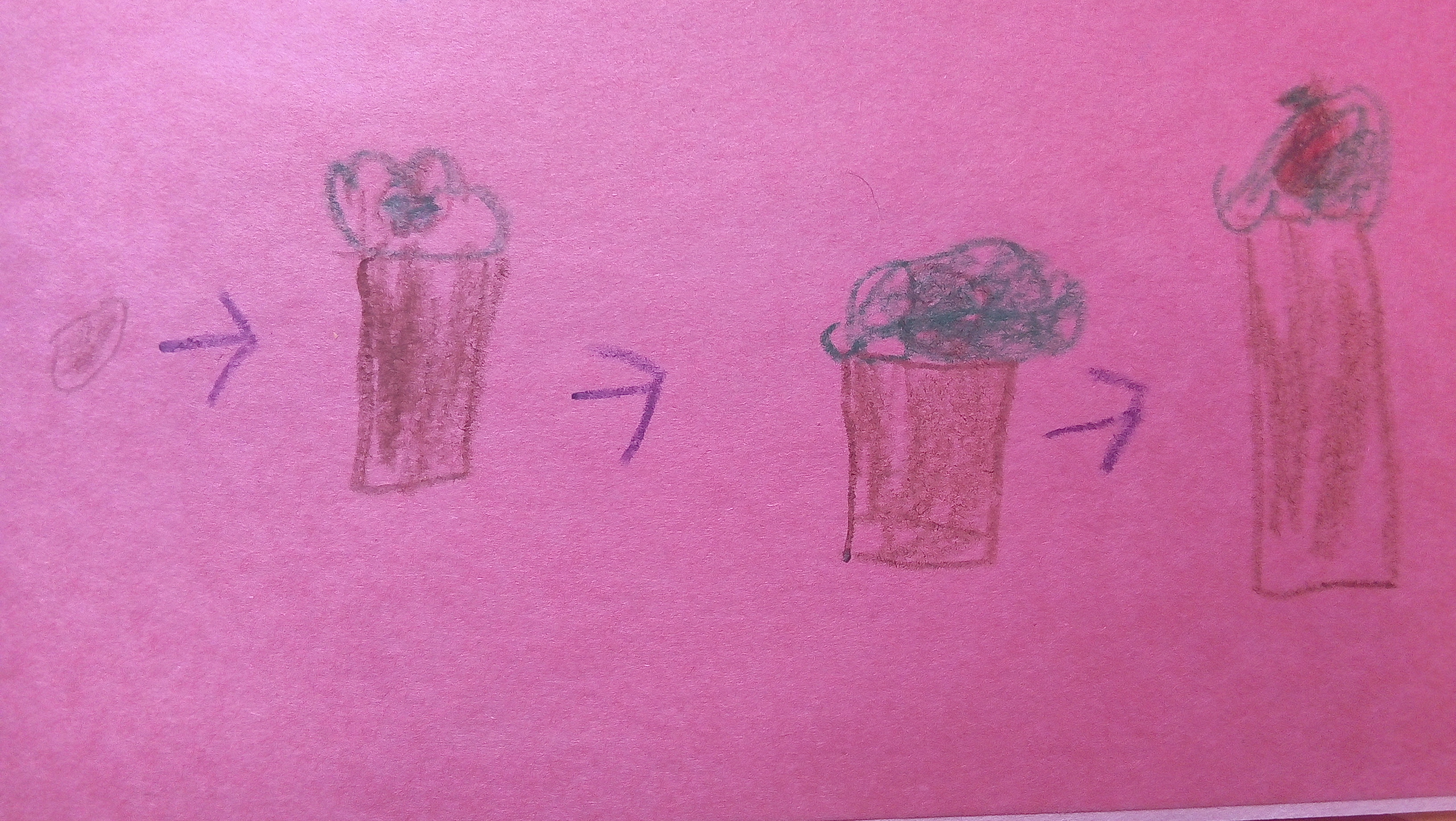

In this example from another student Mark, we observe how he interprets and illustrates the life cycle from seed to fruit. This drawing illustrates his ability to express

- His keen observation skills

- His knowledge about how life cycle of living beings is sequential and progressive

- The difference in size and structure of the plant during each phase in the lifecycle

His drawing demonstrates how the multiple instructional strategies in the UDL lesson to teach the concept of life cycle such as the narrative, pictures and symbols, song, and videos helped him remember, retrieve and express the knowledge he gained.

Fig 2: Mark's representation of the life cycle of an apple. Four drawings that represent growth from a seed to a tree that has a red apple.

Analysis of Teacher and Paraeducator Narratives.

The class teacher and two paraeducators noted the significance of the UDL approach and the opportunities it provided for students. The teacher remarked that the children's attention was sustained, and they seemed to be deeply involved in their learning. All three of them also observed that the variety of modalities available for students to engage in learning, such as music, movement, technology and art, increased their interest and engagement. For example, the teacher said:

I think the actual music incorporation was very effective and reached a different modality and …since all of them really are visual the technology we used for the vocabulary, the YouTube video you used, that was very very effective. I felt it was very appropriate and I think it was timed very appropriately when you talked with them…they were engaged in listening to what you were doing and I think incorporating all of those things is what allowed us to teach the longer lesson like we did cause if it would've been just one modality I think they would have gotten bored or disengaged so I think it definitely was effective.

The paraeducators had been working with the children for quite some time and commented on the effect the variety of activities and materials seemed to have on the children. One paraeducator commented on the variety of materials we brought in to the class and said:

The material was good was wonderful they enjoyed hearing the story, the paper that you brought in for them to follow up on and to draw the seeds and then the tree and the branches and they enjoyed that! That was…good hand eye coordination and then of course all the bananas and apples and everything you brought…and musical instruments were wonderful yeah and guitar they love that yeah you doing the guitar and singing! Oh, so anytime you work with these kind of kids and you bring music into it they love it and let you know I've seen it from five years.

The teacher also observed how UDL allowed children to be engaged in learning in multiple ways and said

…all the centers that we had set up were measuring what they could do some of them were game playing, some were on the word search and the others making a book, right? Putting the book in order and sequencing all of those activities I think too allowed them to show that they were engaged. They were learning and they had different ways of showing that.

One paraeducator noted that the students "…enjoyed learning about the apples and they enjoyed the music aspect of it you brought they love any kind of music and the attention span of the kids was longer." She had an insightful suggestion to make for future practice when she said

Their attention span is not that long, so maybe shorten the session of the lessons…a little bit because once they are on the go they can only stay focused-which I'm sure you know-for so long. The only thing I can tell other than that you know this is all trial and the first time and so this is what we're learning from.

Inviting the paraeducators and not just the teacher to be a part of the study seemed to underscore a sense of belonging in the paraeducators. One remarked, "I enjoyed it. I had never been involved in any kind of study like this and it was new to me…I was pleased and to be able to be involved in it I was honored thank you so much- to be able to be a part of it, to see the kids and Mrs… and all of us involved in it!" The second paraeducator said, "I liked it! I would have liked to have done more! I am a hands on person and I thought it was great!"

We researchers benefitted greatly from including paraeducators in the study. For example, they had some valuable suggestions for future teaching sessions, such as creating model ant farms, making musical instruments, science experiments such as observing the effect of mixing vinegar and soda, etc. Another interesting conversation between the first author and a paraeducator are best shared in the dialogue form that they originally took place.

What did you think of the materials that I brought in?

Oh they were cute. There was only one thing I would change- you planted a seed then an apple tree grew. Its going to take an apple tree years to grow!

Correct!

Maybe if we had more information on how long, or just that how long do you think, it would take that apple tree to grow?

That's a good suggestion! I did briefly mention that it takes years and years for an apple tree to grow but I probably didn't emphasize that!

Yes. In the book it looked like she planted the trees and then next thing, the plants came out! No! No! That's not how it happens. It don't work that way!

[I laugh.] That's a good suggestion! Thank you!

Her comments provided valuable feedback on how we teachers must plan the lesson, materials and narrative carefully so that children are provided access to accurate and authentic knowledge.

The significance of the opportunity to engage in learning opportunities that cultivated competence was aptly illustrated by the class teacher who participated in the study, one year later. She remarked that, "This year our children are required to take part in standardized testing in science and social studies. They got the science part very well, but not the social studies. I think it is because of our project"! (Class teacher, personal communication, March 2016).

Thus, it was evident from the point of view of the teacher and paraeducators, that the UDL approach to teaching ensured that the children were no longer subject to exclusion and classification based on their IEPs, but had access to the same level of learning as their peers without disabilities.

Examination and Assessment

Another way we sought to contest children's containment and recognize competence was by using narrative forms of assessment, alongside the numerical forms of assessment the school required. Narrative assessments are based on a sociocultural, rather than individualized, understanding of learning, and therefore provide a richer and more contextualized account than quantitative methods alone can achieve. We used participant observations, photographs of children's work, anecdotal records of children's conversations, gestural communications, written work and drawings to construct stories of children's learning. In addition to this we sought to listen to and analyze the embodied, verbal and written stories children told of their experiences during the science projects. The learning stories (Carr, 2001) co-constructed by teachers, students and college professors provided a powerful counter-narrative to traditional forms of assessment that focus solely on the individual and are divorced from social context. Indeed, forms of assessment such as tests, examinations and developmental checklists are usually employed to measure and evaluate what individual children know and can do and to highlight what they do not know and cannot do. This leads to the dividing practice of classification in which students' attainment is measured and compared against other students, developmental norms, predetermined goals and state standards. Given that we were working within an educational system in which students must participate in testing programs and schools must demonstrate adequate yearly progress as part of public accountability, we also employed pre- and post-test forms of assessment. However, our goal was to focus on using learning stories as a frequent and ongoing formative assessment tool, rather than on conducting one cumulative and summative assessment through standardized testing. As one class teacher remarked: "We were learning about the process of their learning more than the results." Furthermore, in common with Morton (2012), we were eager to notice and document those contexts, social interactions and experiences that enabled students to show that they were competent, as this provided rich evidence of their scientific and cross-curricular learning. The learning stories below illustrate this.

Marigold and Apple Seeds

John eats his apple for lunch and puts the seeds in his pocket. The tomato plants are wilting. Ms. Jones brings something new to class. John and his friends appear excited and curious at what their teacher has brought in. "We will plant these seeds" she says, showing them Marigold seeds. Everyone looks at the seeds in her hand and laughs. "They are not seeds!" a few children exclaim. "These are seeds" says John, taking out the apple seeds that he has saved from lunch. Ms. Jones talks to them about different types of seeds. They remove the dead tomato plant and plant Marigold seeds in the pot.

In this learning story John and his classmates (participants in study #1) demonstrate their capacity to think scientifically. They observe, compare and contrast seeds by appearance - color, shape, size. They deduce that seeds must have a common appearance and wonder if seeds that don't fit their definition are actually seeds or something else. They demonstrate competence in rejecting a hypothesis by laughing and exclaiming that "…they are not seeds" referring to Marigold seeds. They substantiate their argument by producing evidence [saved apple seeds] that supports their argument. This is an excellent example of children demonstrating their capacity to engage in scientific learning, something that children with intellectual disabilities are considered incapable of. Furthermore, they create a new opportunity for learning for themselves. They determine what the teacher should teach them. These are highly valuable learning outcomes that cannot be tested by standardized assessments that states mandate in P-12 schools.

This short learning story illustrates two important points that we reflected upon as educators. Firstly, that students labeled with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities, previously assumed to be incompetent, can participate successfully in scientific inquiry. Secondly, students demonstrate that they are actively involved in the co-construction of knowledge with their teachers. Dunn (2004) argues that learning stories "can become a vehicle for inclusion, as the teacher increasingly sees the learner, not the disability" (p. 126). The reason for this is that learning stories can provide a contextually rich form of assessment that is strengths-based rather than deficit-based, since the purpose is to recognize children's competence by focusing on what children can do and what their educators need to do next to enhance their learning.

Growing, growing, growing!

Ms. Anne's students seem to keenly observe the plants. Dylan points to the mustard saplings that have pushed themselves out of the soil and says "Look! They are growing, growing, growing!"

"What's growing?" asks Ms. Anne.

"The sticks!" says Dylan as he points to the mustard shoots. "I will show you," he adds. Then he draws a flower on a paper and shows it to his teacher.

Ms. Anne is a special education teacher who participated in the first study. Dylan, her student and another participant in study #1, demonstrates his observation skills. He has a frame of reference to determine what to name new objects he sees in his current environment. He knows what sticks are and drawing from this previous knowledge, compares the mustard shoots to sticks. He also shows an ability to demonstrate his new knowledge in different multimodal ways – verbally, gesturally (through pointing) and through representational drawings. Gathering and documenting student participants' multimodal communicative practices (transcripts of conversations, photographs, drawings and so forth), opens up a whole set of cultural tools in which children can demonstrate their competence and provides a valuable means through which teachers can assess and provide evidence of children's learning. This is consistent with a UDL approach in which students have the freedom to use multiple means of expression to demonstrate what they know rather than being constrained to one particular modality and medium as prescribed by the teacher or standardized tests (Wehmeyer, 2006). In this instance Dylan's repetition of words and phrases such as "growing, growing, growing" was perceived as an example of valuable communication of knowledge, instead of misinterpreting it as echolalia, which is mere parroting of words. Thus UDL assessment is flexible and embedded. Students are afforded multiple means of action and expression. This is in contrast to containment strategies which dictate choices and influence decision-making.

In addition to the learning stories, children's drawings provided another rich source of pedagogical documentation that made their learning visible and provided an alternative to numerical forms of assessment. Pedagogical documentation is developed by or with children, and can take many forms such as children's work samples, written notes, videos, photographs, and audio recordings. As explained by Moss, Dillon, and Statham (2000), "pedagogical documentation plays a role in seeing and understanding children as individuals rather than normalizing children against standardized measures and categorizing some as 'abnormal"' (p.251). Austin's drawing below provides an example of a self-initiated activity in which he drew a ruler next to each stage in the life cycle of an apple tree to illustrate the difference in growth.

Fig 3: Austin's representation of 'Life Cycle of an Apple'. Four drawings of plants increasing in height, with a ruler next to each plant drawing.

This independent addition to what was required by the teacher [i.e. to draw a picture of the life cycle of an apple], aptly demonstrates Austin's competence to apply a mathematical concept [of measurement and graduation] to a topic in Biology [life cycle]. As educators, the UDL approach enabled us to value student-initiated representations of their understanding and to appreciate that pedagogical documentation "adds the qualitative story to quantitative measures of educational assessment" (Couchenour and Kent Chrisman, 2016 p. 435).

Control – the Regulation and Self-Regulation of Children's Bodies and Behaviors

The Weighted Vest

Wednesday. The class seems excited as they look at the tomato plants which have grown a little tall. The boys [his classmates] are taking turns to water them. Stephen is sitting by the plants. He looks upset about something. After a few minutes, he rips the weighted vest off his chest and flings it aside. He probably doesn't anticipate that it would fall on the tomato plant. The tender stems break in half. Another student pulls out a tomato sapling from the pot. "Oh! No! Look, he killed the plants!" exclaims Luke. Stephen drops his head and appears sad. Then Ms. Monica talks to everyone about the need to take care of the plants.

Ms. Monica is another teacher who participated in study # 1. Her student Stephen, who also participated in the study, is 10 years old and he and his six classmates have been diagnosed with developmental disabilities and are grouped in the MOMH functional skills class. MOMH or Moderate Mental Handicap is the outdated way of referring to students with moderate intellectual disabilities but many schools in this Midwestern state still continue to use the label to refer to children with disabilities in special education classes. Teachers can contest the use of such labels by understanding their origins. For example, "handicap" comes from the idea that disabled people have no option other than to beg cap-in-hand (Bone, 2017). As Foucault (1973) suggests, the language we use is never neutral: discourse produces subjects.

Stephen is one of those children who seem to have more energy than other children, so much energy that they are considered hyperactive and hence, unmanageable. It is common practice to make children like him wear a weighted vest, which restricts free movement and makes them sluggish - thus controlling what they can do with their bodies.

We argue that children who are hyperactive are subjected to external control by the use of devices such as the weighted vest and/or medication that slows their movement. Foucault (1997) focuses on the body as a site of institutional power and regulation. He utilizes the notion of the 'docile body' to illustrate how bodies are subject to control, containment and manipulation. In his words, "A body is docile that can be subjected, used, transferred and improved" (p. 136). Docility renders bodies still and/or silent. It invokes passivity (Bailey, 2014). In the classroom children's bodies are contained so as to make them more useful and to maintain order and discipline. Thus, Stephen's body is the subject of biopower and discipline – and yet he is not without power. The weighted vest is intended to make his movement like that of children without hyperactivity, but Stephen is not entirely powerless. He contests this containment by throwing the vest off his chest. Thus, Stephen exercises agency through contesting containment.

This incident led the teacher to further promote inquiry-based learning in her class. Children's actions resulted in damaging and killing some of the plants, which served as an excellent teachable moment for the teacher to promote critical thinking skills in her students. She did this by explaining the care of plants, helping them examine cause and effect [Ex: What happens when you strike a plant with force or pull it out of soil?].

Special education teachers and students are controlled by the overarching philosophy of education that determines their actions in the classroom. The teacher here is complying with the law that allows a team of educators, therapists and family to decide and then document through the IEP what students like Stephen must do in the classroom. IDEA mandates that all procedures implemented towards placement and education of children with disabilities must be decided by the IEP team members and not just by the class teacher. Thus, any procedure that deviates from the team's ruling such as not using the recommended weighted vest puts teachers at risk of losing their jobs. On the other hand, whenever feasible, students with disabilities are allowed to be a part of the IEP team, free to express their ideas, goals and future plans. Had Stephen been a part of that team, perhaps he would have not consented to wear the vest, a rejection that he demonstrates in class in the above example.

In addition to the learning stories we constructed as educators, we also sought to develop a sensibility to the stories children told us. This enabled us to reflect upon our roles as educators, to pay attention to discourses and practices that contain and lead to self-containment, as well as to recognize children's competences. For example, during the UDL study (study #2), Jaylen fetched paper and pencil and engaged in a piece of free writing inspired by the lifecycle project:

The apple trees grows in the orchard And Apples Grow in |trees. A Apple is a fruit Some apples Grow in|spring and fall and summer. I love to eat a apple. But apples do not grow in winter. Some Humans have a apple orchard in there Yard. And you can go to a Johnny apple seed fair if you want to but you must be good forever if you want to go. Some Apples can be red green and yellow. Apples are real. Anybody must be good if they want apples. Do not throw a fit and get whatever you get and Don't throw a fit or else No apples. eat the apples.

Figure 4: A copy of Jaylen's essay. The paragraph above this figure has a transcription of the essay.

Connelly and Clandinin (1990) argue that students' stories are the context for making meaning of the curriculum and school situations. We noticed the following aspects of Jaylen's story that provided evidence of his scientific understanding and socio-cultural experience:

- Biological – "Apples grow on trees". "Apple trees grow in orchards". Apples grow in certain seasons but not others. "An apple is a fruit". There are different varieties of apples: "red, green and yellow". "Apples are real". You can "eat the apples".

- Personal – "I love to eat a apple"

- Social– "Some humans" (people) have a apple orchard in there (their) yard". "You can go to a Johnny Appleseed Fair if you want" to.

- Cultural –"You must be good forever if you want to go" to the fair and if you "want apples". "Do not throw a fit" or else 'No apples'".

As educators, one way we can use this story is to map Jaylen's writing against relevant Language Arts and Science standards as evidence of his academic attainment. Another way we can use this story is to use it to reflect upon the wider sociocultural issues it reveals and how this impacts upon our practice as teachers. Indeed, Goodley and Tregaskis, (2006) suggest that narrative can offer insights into the construct of disability and its effects. Jaylen's narrative suggests he is well aware of social expectations to "be good" and knows that there are consequences if he doesn't conform to cultural norms of behavior. The potential for containment if someone "throws a fit" could result in not being allowed to go to the fair and "No apples.". What also strikes us is the way in which Jaylen has internalized the dominant discourse of behaviorism so prevalent in school, to the extent that he is now engaged in processes of self-regulation and containment. As teachers we need to pay attention to the stories children tell, as they help us to become aware of discourses and institutional practices that contribute to the exclusion of students.

Conclusion

The containment of children with disabilities draws a parallel with the lack of growth in the plants. Half way through the project a few students in one class noticed that some of the plants were wilting, and informed their teachers. Based on an expert gardener's suggestion, children learned how to cultivate the plants by removing the old soil, repotting them in larger containers, and by adding new soil and plant food which had been specially formulated for healthy growth. In time, the students observed that the plants began to revive.

As educators, we too were learning to cultivate the seedlings in our care, by contesting the small containers, classifications and tight controls in which educational structures placed students; namely, the disability label, the functional IEP, the restricted curriculum, the segregated classroom, the summative assessment, the weighted vest, and the hegemony of behaviorism. Our aim in designing UDL lessons that opened up the general science curriculum to all students, and in co-constructing learning stories as an alternative to summative tests, was to broaden our focus beyond students' acquisition of individual competencies and behavioral norms to consider how we might recognize, document and cultivate their competence further. Through the science projects, teachers had the opportunity to be gardeners who allowed children to thrive and grow by removing certain restrictions posed by the self-contained classrooms (such as thinking outside of the IEP and extending the IEP goals to incorporate goals from general education within a UDL approach), by changing the environment (allowing freedom of movement around the classroom, and choice of materials and modes of expression), by providing new opportunities to discover for themselves (through inquiry-based, experiential learning) and by valorizing the healthy growth of children, through listening to the stories children they told.

Just as the analysis of learning stories has helped us to plan the next steps for the children's learning, as educators and researchers we have begun to consider the next steps for our learning. We propose to venture into the general education classrooms of the school and invite teachers to consider implementing the UDL approach, where the three UDL principles allow flexible means of instruction, flexible means of student engagement and a highly motivating and safe learning environment that allows all children to flourish, whatever their level of ability. With patience and perseverance and by fostering an environment of mutual respect, we will all learn that tomatoes will grow and so shall we.

Strategies of containment can mean that students and teachers are disabled by the hegemonic structures of special education which leave them unable to question why students with impairments are denied access to the general curriculum, to their non-disabled peers and to certain physical spaces in the school. Stigmatizing labels, segregated classrooms, deficit-based assessments, a restricted curriculum, weighted vests and educational strategies that control bodies and behaviors all contribute to an experience of containment for children. However, as suggested by the learning stories and narratives offered here, this project has argued that disabled students and their special education teachers can and do exercise agency in contesting these cultural, intellectual, social and physical boundaries. Indeed, we have found that strategies that cultivate competence and support inclusion include:

- applying principles of UDL that encourage multimodal teaching and learning and provide seamless access to the general education curriculum;

- providing a nurturing, classroom atmosphere that fosters interdependent learning;

- facilitating learning through naturalistic inquiry rather than through prescriptive instructional methods that emphasize competence in literacy;

- conducting frequent, ongoing assessment as described in UDL rather than one cumulative and summative assessment through standardized tests;

- and using narrative forms of assessment that recognize children's growing competence and re-story notions of ability and disability.

As we seek to apply strategies such as these it becomes possible to shift from a view of special education as a place for isolation and containment to a view of education as a system of services and supports for all students in the broader context of school and community (Heumann & Hehir, 1997; Hitchcock et al. 2002).

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to the children, teachers and paraeducators who participated in the study and to Dr. Jeffrey A. Nowak, Associate Professor, Educational Studies, IPFW, for his assistance with the projects. Funding for the projects was provided by IPFW and North East Indiana Science Technology Engineering Math (NISTEM).

References

- Allan, J. (2012). Difference in policy and politics: Dialogues in confidence. Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 8, 14-24.

- Ayres, K. M., Lowrey, K. A., Douglas, K. H., and Sievers, C. (2011). I can identify Saturn but I can't brush my teeth: What happens when the curricular focus for students with severe disabilities shifts?. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 47, 3-13.

- Baglieri, S., Bejoian, L. M., Broderick, A. A., Connor, D. J., and Valle, J. (2011) [Re]claiming "Inclusive Education" toward cohesion in educational reform: Disability Studies unravels the myth of the normal child. Teachers College Record, 113, 2122-2154.

- Bailey, S. (2014) Exploring ADHD: An ethnography of disorder in early childhood. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. (ed.) (1990) Foucault and education: Discipline and knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. (2013) Foucault, power, and education. New York: Routledge.

- Bone, K. M. (2017). Trapped behind the glass: Crip Theory and disability identity. Disability and Society, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1313722

- Brantlinger, E., Jimenez, R., Klingner, J., Pugach, M., & Richardson, V. (2005) Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional Children, 71, 195-207. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100205

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Broderick, A. A., Hawkins, G., Henze, S., Mirasol-Spath, C., Pollack-Berkovits, R., Prozzo Clune, H., Skovera, E. and Steel, C. (2012). Teacher counternarratives: Transgressing and "restorying" disability in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16, 825-842. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.526636

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Carr, M. (2001). Assessment in early childhood settings: Learning Stories. London: Paul Chapman.

- Christensen, P. and Prout, A. (2002). Working with ethical symmetry in social research with children. Childhood, 9, 477-497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568202009004007

- Couchenour, D. and Kent Chrisman, J. (Eds.). (2016). The Sage encyclopedia of contemporary early childhood education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483340333

- Connelly, F. M. and Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19, 2-14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002

- Connor, D. J. (2009). Breaking containment – the power of narrative knowing: Countering silence within traditional special education research. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13, 449-470. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110701789126

- Connor, D. J., Gabel, S. L., Gallagher, D. J. and Morton, M. (2008). Disability Studies and Inclusive Education – implications for theory, research and practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12, 441-458. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802377482

- Connor, D. J. and Valle, J. W. (2015). A socio-cultural reframing of science and dis/ability in education: Past problems, current concerns, and future possibilities. Cultural Studies of Science Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-015-9712-6

- Corsaro, W. (2011). The sociology of childhood, (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

- Courtade, G., Spooner, F., Browder, D., & Jimenez, B. (2012). Seven reasons to promote standards-based instruction for students with severe disabilities: A reply to Ayres, Lowrey, Douglas and Sievers (2011). Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 47, 3-13.

- Cousik, R. (2012). Disability as a narrative construction. International Journal of Appreciative Inquiry, 14 (3), 32-35.

- Cowie, B., & Carr, M. (2009). The consequences of sociocultural assessment. In A. Anning, J. Cullen, & M. Fleer (Eds.). Early Childhood Education: Society and Culture (pp. 95–106.). London: Sage.

- Curren, T. and Runswick-Cole, K. (Eds.). (2013). Disabled children's childhood studies: Critical perspectives in a global context. New Nork, NY: Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137008220

- Davis, L. J. (1999). Crips strike back: The rise of disability studies. American Literary History, 11, 500-512. https://doi.org/10.1093/alh/11.3.500

- Danforth, S. and Gabel, S. L. (2006). Vital questions facing disability studies in education. New York: Peter Lang.

- Donaldson M. (1978). Children's minds. London: Fontana.

- Dunn, L. (2004). Developmental assessment and learning stories in inclusive early intervention programmes: Two constructs in one context. New Zealand Research in Early Childhood Education, 7, 119–131.

- Feldman, M. A. Battin, S. M. Shaw O. A. and Luckasson, R. (2013). Inclusion of children with disabilities in mainstream child development research. Disability and Society, 28, 997-1011. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.748647

- Ferri, B., and Connor, D. (2005). Tools of exclusion: Race, disability, and (Re) segregated education. The Teachers College Record, 107, 453-474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2005.00483.x

- Foucault, M. (1967). Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason. (R. Howard, Trans). London: Tavistock.

- Foucault, M. (1973). The birth of the clinic: An archaeology of medical perception (A. Smith, Trans.) New York: Vintage Books.

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of a prison. (A. Sheridan, Trans) London: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. (1992). Governmentality. In F. Burchall, C. Gordon and P. Miller. (Eds.). The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 97-104.

- Gabel, S. (2005). (Ed.). Disability Studies in education: Readings in theory and method. New York: Peter Lang.

- Gleeson, B. J. (1997). Disability Studies: A historical materialist view. Disability & Society, 12, 179-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599727326

- Goodley, D. (2011). Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. London: Sage.

- Goodley, D. and Tregaskis, C. (2006). Storying disability and impairment: Retrospective accounts of disabled family life. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 630-646. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305285840

- Gresham, F. M. (1986). Strategies for enhancing the social outcomes of mainstreaming: A necessary ingredient for success. In C. J. Meisel (Ed.) Mainstreaming Handicapped Children: Outcomes, Controversies and New Directions (pp. 193-218). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Harry, B., Rueda, R. and Kalyanpur, M. (1999). Cultural reciprocity in sociocultural perspective: Adapting the normalization principle for family collaboration. Exceptional Children, 66, 123-136. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299906600108

- Hehir, T. (2002). Eliminating ableism in education. Harvard Educational Review, 72, 1-33. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.72.1.03866528702g2105

- Hogan, D. (2005). Researching "The Child" in developmental psychology. In S. Greene and D. Hogan (Eds.). Researching children's experiences (pp. 22-41). London: Sage.

- Holt, L. (2004). Childhood disability and ability: (Dis)ableist geographies of mainstream primary schools. Disability Studies Quarterly, 24, 3. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v24i3.506

- Hinshaw, R. E., & Gumus, S. S. (2013). Universal Design for Learning principles in a hybrid course. SAGE Open, 3, 2158244013480789.

- Hughes, B. (2013). Disability and the construction of dependency. In L. Barton (Ed.) Disability, Politics and the Struggle for Change (pp. 24-33). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hutchby, I. and Moran-Ellis, J. (1998). (Eds.) Children and social competence: Arenas of action. Lewis: Falmer Press.

- James, A., Jenks, C. and Prout, A. (1998). Theorizing childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Kumari Campbell, F. A. (2008). Exploring internalized ableism using critical race theory. Disability and Society, 23, 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590701841190

- Lalvani, P. (2013). Privilege, compromise or social justice: Teachers' conceptualizations of inclusive education. Disability and Society, 28, 14-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.692028

- Lee, N. (2001). Childhood and society: Growing up in an age of uncertainty. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Morrow, V. (2005). Ethical dilemmas in research with children and young people about their social environments. Children's Geographies, 6, 49-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280701791918

- Morton, M. (2012). Using Disability Studies in education to notice, recognize and respond to tools of exclusion and opportunities for inclusion in New Zealand. Review of Disability Studies, 8, 25-34.

- Moss, P., Dillon, J. and Statham, J. (2000). The "child in need' and "the rich child": Discourses, constructions and practice. Critical Social Policy, 20, 233–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101830002000203

- Odom, S. L., Brantlinger, E., Gersten, R., Horner, R. H., Thompson, B., & Harris, K. R. (2005). Research in special education: Scientific methods and evidence-based practices. Exceptional Children, 71, 137-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100201

- Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Ryndak, D. L., Taub, D., Jorgensen, C. M., Gonsier-Gerdin, J., Arndt, K., Sauer, J., Ruppar, A. L., Morningstar, M. E. and Allcock, H. (2014). Policy and the impact on placement, involvement and progress in general education: Critical issues that require rectification. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 39, 65-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796914533942

- Prout, A. (1990). Children's participation: Control and self-realisation in British late modernity. Children and Society, 14, 304-315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2000.tb00185.x

- Prout, A. (2005). The future of childhood. Abingdon: Routledge Falmer.

- Rabinow, P. (1984). Introduction. In P. Rabinow (Ed.) The Foucault reader (pp. 3-29). London: Penguin.

- Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. New York: Oxford University Press.

- La Salle, T. P., Roach, A. T., & McGrath, D. (2013). The relationship of IEP quality to curricular access and academic achievement for students with disabilities. International Journal of Special Education, 28, 135-144.

- Shallwani, S. (2010). Racism and imperialism in the child development discourse of "developmentally appropriate practice". In G. S. Cannella, and D. S. Soto, (Eds.), Childhoods: A handbook (pp. 231-245). New York: Peter Lang,

- Shildrick, M. (1997). Leaky bodies and boundaries: Feminism, postmodernism and (Bio) ethics. London: Routledge.

- Skrtic, T. M. (1995). Disability and Democracy: Reconstructing [Special] education for postmodernity. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Smith, A. B. (2002). Interpreting and supporting participation rights: Contributions from sociocultural theory. International Journal of Children's Rights, 10, 73-88. https://doi.org/10.1163/157181802772758137

- Trela, K. and Jimenez, B. A. (2013). From different to differentiated: Using "ecological framework" to support personally relevant access to general curriculum for students with significant intellectual disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 38, 117-119. https://doi.org/10.2511/027494813807714537

- Valle, J. W., Connor, D. J., and Reid, K. (2006). IDEA at 30: Looking back, facing forward—a disability studies perspective. Disability Studies Quarterly, 26, 2. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v26i2.678

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky, New York: Plenum Press.

- Wehmeyer, M. L., Lattin, D. L., Lapp-Rincker, G., & Agran, M. (2003). Access to the general curriculum of middle school students with mental retardation: An observational study. Remedial and Special Education, 24, 262-272. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325030240050201

- Wehmeyer, M. L. (2006). Universal Design for Learning, access to the general education curriculum and students with mild mental retardation. Exceptionality, 14, 225-235. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327035ex1404_4

- Woodhead, M. (2005). Early childhood development: a question of rights. International Journal of Early Childhood, 37, 79-98. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03168347