When I first heard of Ellen Forney's graphic memoir, Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me, I was intrigued but didn't think it would necessarily be a good text for use in my classroom. Forney's experience as a queer woman artist with bipolar disorder struck me as both too specific and too far away from the experiences of my Midwestern public university students. But once I read the book, I realized how narrow my own viewpoint had been. Forney's writing and illustrations are compelling and complex, yet tremendously clear and accessible for a wide range of readers.1

I soon began assigning Marbles in a variety of undergraduate classes, including courses on literature and disability, gender and disability, and the cultural politics of illness. My students' response was immediate and enthusiastic in every class. For some, the graphic format was a revelation, giving them access to a medium of expression they hadn't realized could be "serious" enough to belong in a classroom. For others, their own experiences with bipolar disorder or major depression not only meant they felt a personal connection to the text, but even more so that it gave them language with which to address a topic that had been mostly taboo or stigmatized in their lives.

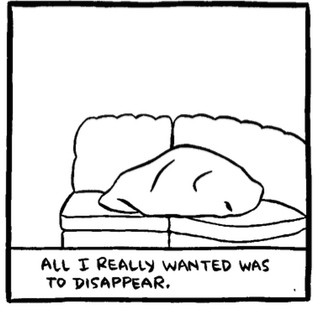

In class, I use a variety of techniques to draw out these responses. For example, in one fairly large discussion-based class (30 students), I brought crayons and markers for stduents to create drawings of "depression." I collected the drawings, randomized them, and passed them back so each student could describe another anonymous student's drawing for the class. We then identified common visual themes and tropes that emerged in their drawings and connected them back to specific images in Forney's book. For example, many students drew pictures of themselves hiding under bedclothes, much like Forney's drawing of herself on page 81 [Fig. 1].

On this page, there are six square frames, each of which shows an almost identical image of a shapeless lump of blanket on a couch. The blanket and couch cushions are drawn as thick black outlines around empty white space, so that the figure under the blanket merges into the furniture. In the first four frames, there is what seems to be a fold or opening on the end of the blanket-lump, which when examined more closely resembles an open eye, further reinforcing the merging of Forney's narrator with inanimate objects. In the fifth frame, part of a human face and one arm has emerged from the blanket, the hand covering the face with fingers splayed, but in the sixth frame, the human figure has disappeared again and the blanket-lump-eye is now closed. Below this final image are the words, "All I really wanted was to disappear."

Depression and anxiety are reaching near-epidemic levels among college students in the United States, as the National College Health Survey has recently shown, and as many of us who work or study at American universities will know firsthand.2 While some of my students had already spoken in class about their experiences with depression, it was quite powerful to see how many who had not talked about it—indeed, some who generally didn't talk at all—made a deeply visceral connection to the visual depiction of depression through Forney's book. Indeed, another strength of using Marbles in the classroom is how it offers students different ways to participate—speaking, writing, drawing—that then also make space for different learning styles and communicative literacies.

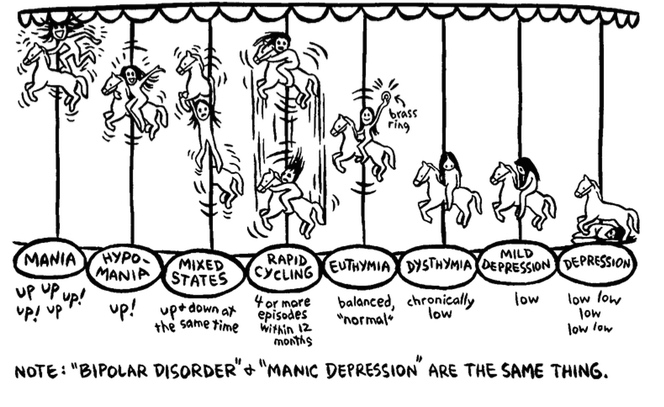

Another of the images from Marbles to which students frequently return is the carousel which Forney uses to illustrate different mental states associated with being bipolar on p. 59 [Fig. 2]. In this half-page frame, a long-haired human figure representing Forney rides atop eight carousel horses labeled with the mental states of "mania," "hypomania," "mixed states," "rapid cycling," "euthymia," "dysthymia," "mild depression," and "depression." Each horse is in motion to represent the effect of this state on Forney, from the manic horse leaping so high it smashes her against the roof, to the depression horse that is sunk as low as possible with Forney curled up in a fetal position below. The "normal" state of euthymia, or balance, shows Forney atop a horse in the middle, sitting triumphantly upright and brandishing a "brass ring" of normalcy. This illustration helps students to grasp and discuss both the negative aspects of mania—which, as Forney acknowledges, can sometimes seem to an outsider like a desirable state due to euphoria and high productivity—and more importantly, to understand the state of mental "normalcy" as something artificial, a state that is culturally rewarded yet difficult both to attain and maintain.

This brings me to the third great strength of Forney's memoir, as well is its most prominent overarching theme: the connection and possible tension between creativity and mental disability. At the start of the memoir, as Forney is first diagnosed with bipolar disorder, she resists both medication and the idea that she is somehow connected to other famous artistic figures who are believed to be bipolar or have other mental disabilities. She invokes the Michelangelo of the title and a host of others, most notably painter Vincent Van Gogh, to defend herself against the proposal that she must normalize her mental state at the expense of her artistry. Later, after the intolerable suffering of a depressive episode propels her into a years-long journey to find effective treatments, including medication, yoga, journaling, and talk therapy, Forney returns to this question in the last two chapters of her book.

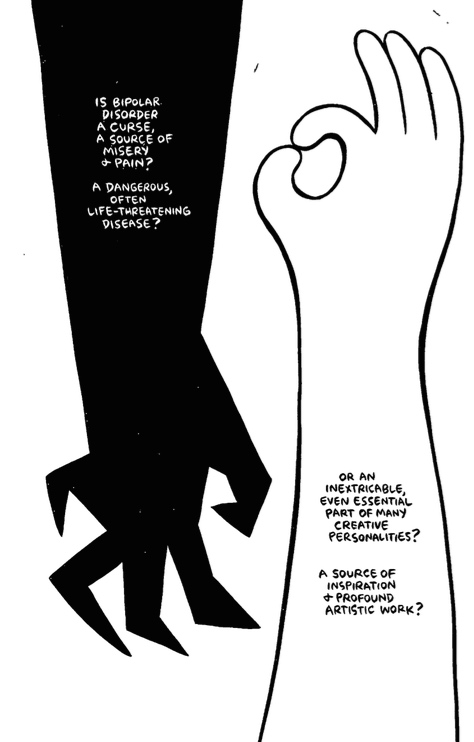

At the start of chapter eight, Forney asks, "Are bipolar disorder and creativity actually linked?" Her conclusion comes in the following chapter, with a full-page image of two humanoid arms juxtaposed in a yin/yang-like parallel [Fig. 3]. The left arm is stark black against a white background, its claw-like fingers jaggedly crooked. White letters on the forearm ask, "Is bipolar disorder a curse, a source of misery and pain? A dangerous, often life-threatening disease?" On the right, the arm is an outline of black over white space, its fingers forming an "OK" sign, while black letters spell out the rest of the question: "Or an extricable, even essential part of many creative personalities? A source of inspiration and profound artistic work?" The next page gives the answer, "I suppose it's both," above an image of the two hands clasped tightly together.

I love this ending not only because it gives such rich material for class discussion, but also because it models for students the possibility of a conclusion that doesn't fall into "either/or" dichotomies, a possibility that is one of the most challenging and important concepts I seek to promote in my class discussions and writing. The fact that Marbles offers such rich, topical, and accessible material for students in the disability studies classroom, as well as a model for developing critical thinking and writing skills, means that it has swiftly become a regular text in my classrooms and I highly recommend it for others as well.

Endnotes

- The queerness of Forney's memoir is

a strong presence, and one that engages many students, while potentially

alienating others. Forney's choice to introduce her narrative with a vision

of her manic state as hypersexualized, including a fairly graphic portrayal

of an all-woman porn photo session (as the basis for a cartoon she was

creating) is edgy and may not work in all classroom settings, or at least,

could require some careful preparation and framing.

Return to Text - American College Health

Association. (2014). American College Health Association-National College

Health Assessment II: Undergraduate Students Reference Group Executive

Summary Spring 2014. Hanover, MD: American College Health Association.

Return to Text