In this article, I report on an IRB-approved auto-ethnographic study of a disability studies rhetoric course that I designed and taught at a mid-size Midwestern university. The study examines students' multi-modal life writing compositions, "normal commonplace books" (journals of students' encounters with the assumptions, or commonplaces, of normalcy), and classroom discussion, asking: How do students' use normalizing discourses in relation to disability and other marginalized identity categories? And, how might educators pedagogically intervene in such discourses? Ultimately, I found that exploring a "rhetoric of normalcy" might help educators access students' experiences with disability, and consequently, redress the hegemony of the norm. The study revealed that students were more likely to use normalizing discourses in their written responses rather than during in-class discussions. Similarly, the instructor intervened in these problematic discourses in written feedback rather than verbally in classroom exchanges. The study also proved that after exposure to critical disability studies, students were more willing to discuss other social justice issues relating to race, sexuality, religion, and class. In keeping with the aims of the special issue, the results of this study suggest one way to teach disability studies content to a variety of audiences, and detail an approach used by a teacher-researcher to study a DS classroom.

Introduction

I always wanted to be normal; I always wanted to be like everybody else, everybody else but me. Normal, to me, meant thinking that the glass is half-full, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps, be a productive, well-functioning member of American society. Don't complain. Be brave. Don't sweat the small stuff. But I am not normal. I am an obsessive thinker and worrier, prone to depression and anxiety, and I have a body that never quite functions as it should. I am a thirty-eight-year-old female still in school without a stable job, a house, without 2.3 children and a white picket fence (at least I have the partner—Check). If I took a "normal" measuring stick to calculate how well I have been succeeding and fitting in with other women similar to my age, I expect to fall below the bell curve.

I happened upon Lennard Davis's Enforcing Normalcy in the second semester of my first year as a PhD student in English Studies. There I was introduced to the concept of the bell curve invented by 19th century Western European statisticians which was used to construct the "average man" and to separate the desirables from the undesirables, the normal from the abnormal, and the abled from the disabled. Through Davis's scholarship, I realized that discourses of normalcy are a fiction, or rather an ideology, constructed by the most powerful to dominate and oppress the most vulnerable. Apparently, then, the narratives that I had been measuring myself against my entire life were just stories propagated by discourses of normalcy, insidious because they denied their own rhetoricity.1 The relief I felt while reading Davis and the work of other disability studies (DS) scholars cannot be exaggerated. And yet despite reading and doing work in DS, I am still carrying around that "normal" measuring stick, knowing that the most powerful narratives are the hardest to resist.

I use this story, my awakening to the ideology of the norm, as an attempt to describe why I chose to theme my teaching internship course: "The Discourses of Normalcy." I do not want my students to wait until they are my age to realize that being normal is a façade and trying to fit in with the norm suppresses our unique identities. At my university, graduate assistants are given the opportunity to teach an upper-level undergraduate course in their area of study during the third-year of their PhD program. We have the freedom to make our own pedagogical decisions regarding the assigned course, as long as we meet the learning outcomes described in the course catalog. I requested and was assigned to teach English 246: Advanced Composition, which is part of the undergraduate rhetoric and composition track. After seven years of teaching first-year and basic composition courses with prescribed pedagogies, I was thrilled with my internship assignment. For this class, I integrated the fields of rhetoric and composition and disability studies, and by doing so, focused on the subfield of disability rhetoric. This article is an account of that integration.

I received IRB approval to use the course to conduct a study on student reactions to a rhetoric and composition course that incorporated disability studies. I consider my "Discourses of Normalcy" study an exploration of not only how my students respond to and produce normalizing discourses, but also of what it means to learn and teach disability in the writing classroom. I did not pre-determine the outcome of this study. I did not go into this looking for evidence to support a theory. Instead I wanted to see where my students would take me. To do so, I turned to what DS scholars consider accessible research methods. Methods that Brenda Brueggemann ("Rethinking Practices") calls "improvisation on the fly," Margaret Price ("Writing From Normal") describes as "planning and improvisation," and Jay Dolmage ("Mapping") refers to as not concrete tasks but "ways to move." In order to do this I had to step aside as the researcher and realize that my students, the research participants, are the experts in the classroom that I designed and that their responses are the data that would tell me what I still needed to know about teaching disability studies in the composition classroom. I developed the following research questions (which is admittedly a normative convention used in most IRB qualitative studies) to guide what would become an auto-ethnographic multimodal, mixed-method research study:

- What does it look like to teach and learn about disability in a composition classroom?

- What awareness do students have that negative stereotypes lead to stigma and violence against Others?

- How aware are students of the ways in which they have been constructed by normalizing discourses and conversely how do they construct others through these discriminatory discourses?

- How might a pedagogy that combines composition theory and practice and disability studies serve to promote social justice while also helping to improve students' literacy abilities?

- How does a disability studies-themed course promote opportunities for greater access for all students in the rhetoric and composition classroom?

"Discourses of Normalcy": Research Participants, Methods, and Data Collection

My advanced composition class consisted of a mix of eighteen students ranging from sophomores-to-seniors: fifteen of whom were English and English Education majors and the other three of whom were related liberal arts majors. Located in a Midwestern, mid-sized university, most of my students were white, and presumably middle-class, raised in a politically conservative environment. Five students were male and the remaining female. Four students were of color and initially all students were seemingly able-bodied. I mention these specifics because I know that student subjectivity in relation to the course content, like the instructor's subjectivity, effects how class material is taken up and used.

As is true at the graduate level, there is no major or certificate in disability studies at the undergraduate level at my university. I held no expectations than that my students would have been introduced to DS or encounter it again after leaving my classroom that semester. Consequently, I felt a tremendous responsibility to represent the importance and value of critical disability studies to the field of rhetoric and composition, to my students' course work, and to their individual lives.

Although I was the teacher on record for the course, my IRB required a P.I. (Principal Investigator) who was an accredited professor while I served as the Co-P.I. of the study. The P.I. attended the class twice: once to explain the study and the second to observe the class. According to the study's IRB, students could opt-out of participation in the study by not signing the consent form passed out during the P.I.'s introduction of the study. The identities of those who opted-out of the study were not to be known to me until course grades were entered. I found out afterward that all of my students did agree to participate in the study. Participation meant that they were willing to have their classwork used in the study and in any publications in respect to the study without identifying information; each student also granted me access to analyze and publish peer review group and class discussions, and permission to record student-teacher conferences.

Course content was divided into three parts according to the three major projects: an art as representation paper, a life writing paper, and a multimodal remix of the life writing paper. For the first part of the semester, students were introduced to cultural studies concepts for analysis from Jeffrey Nealon and Susan Searls Giroux's The Theory Toolbox which they applied to critical disability studies theoretical readings, including portions of Simi Linton's Claiming Disability, Tobin Seibers's Disability Theory, Lennard Davis's Enforcing Normalcy, Susan Schwiek's The Ugly Laws, Rosemarie Garland Thomson's "The Politics of Staring," and Erving Goffman's Stigma. Although many of the core readings were focused primarily on disability identity, they worked effectively as a springboard for discussing other socio-political identity constructions. For the second part of the semester we turned our attention toward life-writing on disability and normalcy, which took many forms such as disability blogs, videos, sound essays, webtexts, graphic memoirs, and personal essays including selections from Brenda Jo Brueggemann's Lend Me Your Ear and Nancy Mairs's Waist-High in the World. The third part of the course addressed issues of normalcy and access and how multimodal compositions had the potential to provide greater opportunities for literacy and access than did traditional compositions. Work from disability rhetoric scholars Jay Dolmage, Cynthia Selfe, and Melanie Yergeau guided discussions.

The data I collected took a variety of forms. I kept a teacher-journal to record and reflect on class discussions and my pedagogical decisions after each class, which I did not share with the students. As I was working on the journal, my students were doing a similar project. Using the university's online course management system, students created a class record of the course and posted it on our course website. Along with the three major course projects, I also collected student reading responses to the course material and audio-recorded (with permission) peer group meetings and conferences that took place prior to the collection of each final project.

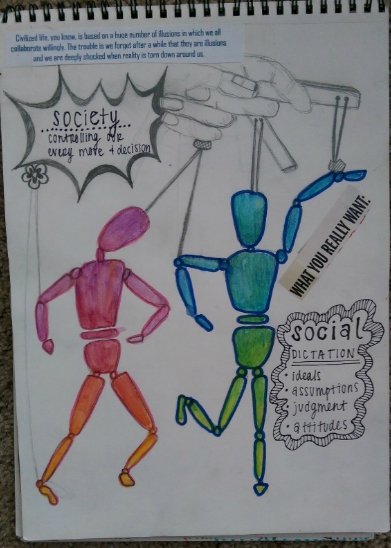

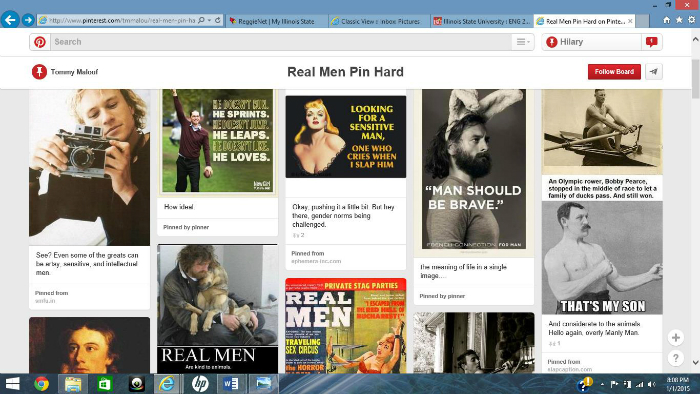

The most interesting and valuable data I collected for the internship was the "Normal Commonplace Books." Throughout the semester, students were asked to take notice of some of the societal commonplace assumptions in regards to normalcy, stigma, and stereotypes and to arrange them in a "book." This was a semester-long project and the students used various material and digital technologies to create the books. These books took the form of scrapbooks, dioramas, Pinterest boards, videos, musical performances, sound essays, and more. The content of the Normal Commonplace Books differed: some students chose to present through visual images and text their norms in contrast to acceptable societal norms, while others chose to represent one or the other, and some read as if they were diaries that documented their changing perceptions of normalcy as the class evolved. Other trends showed that students focused on specific aspects of normalcy such as gender norms while others looked at normalcy more generally. As part of the assignment, students had to use quotations from the course readings in order to put in context what they were learning. The following are some samples of the different forms of these commonplace "books":

Image: Two puppets, one a blue-colored male featured on the right and one a pink-colored female figure featured on the left, are controlled by society's hand pulling them with strings. Two thought bubbles list societal norms that might be in contrast to personal norms. The caption overhead the figure reads: "Civilized life, you know, is based on a huge number of illusions in which we all collaborate willingly. The trouble is we forget after a while that they are illusions and we are deeply shocked when reality is torn down."

Image: Using a mix of images and text, some taken from course readings, this student creates a Normal Commonplace Pinterest Board that takes a playful look at male gender norms. The images selected juxtapose pictures of stereotypical "real men" and "sensitive men." The "real men" images feature well-built, athletic males usually shirtless and engaged in traditionally thought- of- as masculine sports such as rowing, boxing, and football. Under these images the student uses captions to write sarcastic quips such as "how ideal" and "Hello again, overly manly man." The images of the "sensitive men" include men snuggling with animals, poets lost in thought, and artists. Underneath a picture of former actor Heath Ledger holding a camera, the student writes the following caption: "See? Even some of the greats can be artsy, sensitive, and intellectual men."

Image: A rectangular box is covered with black construction paper. Newspaper clipping and web images of "norms" are taped on the box. Using computer paper, the box is gift-wrapped with pieces of string containing normalcy quotes taken from the readings and her own thoughts on normalcy.

This assignment gave me a unique glimpse into how the students were responding to the course theme and in what ways they were taking up the content, repurposing it, and applying it to their own lives. The fact that the Normal Commonplace Books are multimodal compositions also allowed me to explore how multimodal compositions compared to traditional written compositions as samples of student knowledge production. The project was indeed challenging (and fun!) for the students and for myself. First, students were tasked with integrating the course content into their own schemas and then with having to produce an original composition conveying what they learned regarding normalizing discourses. The fact that the "form" of the commonplace book was entirely open-ended caused some students to panic. The panic also suggests that they were intimidated by a non-normative composition assignment which asked them to think differently about what counts as "writing." To assist with their apprehension regarding the project, I told them I did not have to completely "get" the message about normalcy they wished to convey (which is also true, I told them, of text-based writing), only that I needed to be able to tell that they were engaging with normalcy constructions and course readings. As the teacher, I was challenged with trusting my students' expressions of knowledge as valid and apparent even if I struggled to comprehend them. Overall, I was pleased with the project's results and with the decision to assign it as a semester-long project, since it allowed students to capture their evolving reactions to being exposed to normalizing discourses.

My findings suggest that students seemed to prefer, or had more confidence in, using digital technologies such as Pinterest, video, and social networking sites rather than using material technologies and performance as formats for their "books." Visual and textual modes were used more than auditory modes for composing and delivery. Of all the data collected, the Normal Commonplace Books showed the most evidence of students' growing awareness of how minority groups are stigmatized and marginalized by linguistic and visual representations. In response, students "talked-back" to these representations by using their commonplace books to create counter-narratives of normalization. These findings also suggest that multimodal assignments unlike strict, linear, rule-based writing assignments allow students to access more aspects of themselves and their abilities in the composing and delivery process. Likewise, the audience of multimodal compositions have greater opportunities at accessing these compositions. Although beyond the scope of this study and article, the above would suggest that the field of composition studies has much to gain from universal design pedagogy.

Finding a Pedagogy of My Own

The semester before teaching my internship course, I was introduced to several pedagogies taken up by the field of rhetoric and composition: cultural studies pedagogy, feminist pedagogy, process pedagogy, and critical pedagogy. I troubled myself all semester to fit my teaching philosophy into one of those prescribed pedagogies, frustrated that I was attracted to some aspects of all of them. For someone who is accustomed to striving to be normal, I wanted to find my pedagogical box and climb right in. However, it would take the entire semester to realize that many rhetoric and composition instructors enact hybrid pedagogies and that mine would naturally emerge from the very scholarship I studied and valued: the field of disability rhetoric.

I knew I wanted to include disability scholarship as soon as I received my internship assignment, but I was unsure of how students, who would be unaware of the theme when registering for the course, would react to an entire semester of advanced composition devoted to disability studies content. To reach a wider audience (or to try to please more students?), I decided to use discourses of normalcy as the class theme to address issues such as disability/ability, stigma, white privilege, sexuality, and gender norms with the intention that by doing so, we could build an awareness of oppressive ideological norms. I also told myself that concentrating on normalcy rather than just disability studies would be more useful to my English Education majors who would, as high school teachers, encounter diversity and issues of normalcy in their classrooms. I also knew that I was not the first teacher-researcher to realize the potential of incorporating the theme of normalcy into the rhetoric and composition course (see especially Price's "Writing from Normal"), and I am indebted to the work that has been done before me. Therefore, from the onset, the intention of my study has been to build on and extend the scholarship in this area.

In retrospect, I could have themed the course content only on disability studies rather than widening its scope to normalcy (I certainly had enough material!), but the fact that I chose not to, and did not adjust the theme the two consequent times I taught the class, speaks to my own insecurities regarding seemingly non-disabled students reluctance to engage with disability. I do not regret theming the course on discourses of normalcy, agreeing with Tobin Seibers that disability theory has the potential to align all marginalized identity categories and to address the normalizing discourses that construct them. Indeed, from the data collected, students' exposure to critical disability studies early in the semester allowed them to be more open and willing to discuss other social justice issues relating to race, sexuality, religion, and class. Yet despite the effectiveness of the course theme, I find myself still wondering at my decision-making, and I am left with the question: How can I expect my students to realize the potential of disability studies to their course work and individual lives when their instructor is hesitant to fully engage with the field?

However, scholarship on benefits of integrating disability studies in the rhetoric and composition classroom is well-documented (see especially Brueggemman and Lewiecki-Wilson, Dolmage, Dunn, Vidali). When reviewing this scholarship, I can see that my hesitancy to focus my internship course entirely on disability issues instead of normalcy was misplaced since deconstructing normalcy is fundamentally a disability issue. Disability rhetoricians see a close relationship between disability studies curriculum and the work needing to be done in the composition classroom. Brueggemann and Lewiecki-Wilson note that "the core concepts of disability studies scholarship—such as claiming and naming, embodied learning and writing, and social stigma and the social construction and representation of disability—are especially pertinent to writing instruction" ("Rethinking Practices" 91). They argue that the questions posed by disability studies theory are also questions needing to be addressed in the composition classroom, questions that relate to language and its effects, understanding the role of the body in learning and writing, issues of access and exclusion, and theories of difference. Price adds that disability pedagogy is a critical pedagogy and necessary in a disability-themed basic writing course. Vidali agrees that DS pedagogy is an agent of change and that disability-themed undergraduate writing courses lead both students and teachers to become deeper critical thinkers and readers.

While teaching the course, I found all of the above to be true. Initially, my P.I. questioned my decision to use disability studies content and theory in a composition course. She was concerned that reading disability studies scholarship would not appropriately address the course goal of teaching writing. Yet the issues that disability studies brought to the class such as embodiment, access, social construction, and the material effects of language made my students more conscious of their own language choices and the power that their own rhetoric and compositions would have on social realities and inequities. Understanding how their bodies functioned in relation to not only how they wrote but what they wrote also made them more socially-conscious writers and more cognizant of their own subjectivities in relation to the normalcy issues they explored. In addition, being asked to consider their own bodies' limits and strengths gave them greater insight into how access is not an issue just for the disabled but for all bodies.

Of course, after all my course work and teaching experience I am still not sure what it means to teach writing and how to select course content that enables students to become "better" writers. I do not mean to sound self-deprecating in the above statement, rather I feel as if learning to teach writing is an on-going process and questioning this process is fundamental to my growth as a teacher of writing. Nonetheless, I am confident that my students left the course with more critical awareness about "writing" and its effects because of their exposure to disability studies.

Ironically, when I planned my internship course I was not familiar with disability studies pedagogy. Yet my course goals and assignments reflect that I was enacting a DS pedagogy without realizing it. This realization has given me insight into how a teacher develops her own pedagogy. I now see that "pedagogy" is not a static category to be fit into, but rather a philosophy that emerges from our subject positions, identity formations, and our ways of being in the world. During the teaching of my internship I found myself constantly revising what I wanted my students to "get" from the course. I made changes to the assignments, readings, and class activities not only based on student responses to the material, but also in connection with the community we were building in our classroom and our knowledge of one another. Despite my initial trepidation over teaching an advanced composition course without fitting my own pedagogy into other scholarly approaches, my internship experience was both enjoyable and meaningful—to me and my students. I like to believe that the disability studies inspired course content is largely responsible for my students' writing and critical thinking development and for the safe, warm, and respectful environment in which our learning took place. However, this does not mean that the course went perfectly smoothly or that new considerations did not continuously arise during the planning and teaching of my internship. I touch on one major concern—disability disclosure—below.

Disability Disclosure, Identification, Interdependence

One of the greatest questions that arose during my internship was how to address my own subjectivity as a teacher with a disability. A plethora of scholarship has been devoted to the legal, psychological, and socio-economic effects of disability disclosure. The fear of stigma, contend DS scholars, has led many persons with disabilities to a life of passing (see especially Brueggemann and Moddelmog, Kleege, Titchotsky). This is often the case for both students and faculty in academia. In her research on disabled faculty in the academy, Stephanie Kerschbaum informs that such disclosure can be traumatic and shameful and is often met with denial, resistance, and ignorance and is not a singular event. Considering this research, I had to think carefully about the risks and benefits that disclosing my disability would have not only on my students but on myself as well and the possible long-term effects of that decision.

I had some concerns: Would my students think less of me? Would they think I was revealing too much about my personal life? Would they feel embarrassed for me or pity me? I already knew that I was not satisfied with burying the required statement regarding disability and special accommodations at the bottom of my syllabus and instead wrote my own version of the statement to be placed at the top of my syllabus. I added to the required statement that the "class attempts to accommodate all learning styles" and to "please tell me if this is not the case." I also wrote that as a person with a disability, I was sensitive to students with disabilities and accommodation concerns and encouraged self-disclosure to ensure the best education for everyone. Apparently then, I made the decision to come-out as disabled to my students. However, I chose not to disclose my particular disability until later in the semester, and I knew that coming-out on paper was much safer than doing so face-to-face.

The decision for teachers to "come out" as disabled in the classroom must be an individual one and needs to align with a teacher's pedagogy. Regardless of the decision made, I am convinced that the choice can profoundly affect the dynamics of the classroom. Personally, I believe that through disability disclosure a teacher-researcher enacts identification and interdependence which are key principles of DS methodology and pedagogy. In both of Margaret Price's and Michael Oliver's work on DS methodology, the importance for DS researchers to self-identify with their research and with their research participants is stressed. Price is dismayed that so few researchers in DS-themed studies discuss their, "own positions, identifications, or alliances with respect to the topic they research" and calls for DS research to, "make more space for explicit identification by researches ("Disability Studies" 171). Similarly, Oliver notes that emancipatory research is enhanced when DS researchers and research participants are aware of each other's subjectivities. Therefore, my decision to disclose my disability is partly due to disability studies ethic of identification.

In retrospect, I am not sure what effects my disclosure had on my students. After making my disclosure announcement, not a single student came to me to self-disclose. Perhaps this was because none of my students identified with being disabled, although one student did write his life-writing narrative about his experiences with ADHD and another about her experiences with rheumatoid arthritis (but that was much later in the course). Also, my disabilities—fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome—are not visible and are poorly understood. Thus, my disclosure might have been anti-climatic. And yet, I like to think that my disclosure marked the beginning of what became a space where respect for differences, vulnerability, and empathy was nurtured. In writing and in class discussions, my students shared their own individual experiences with feeling "abnormal" and marginalized. My male students talked about their fear of crying and how much that gender norm repressed them. Another student spoke about her shame in not grieving normally while another shared her experiences with racism as a biracial woman. I do not mention these stories to make a point about how therapeutic the writing classroom can be; rather, I am interested in sharing how teaching composition through a DS perspective and a DS pedagogy can start to upset the oppressive forces of normalizing discourses.

Also, I believe my decision to disclose my disability to my students and the disability-themed course content fostered a spirit of what DS and rhetoric scholars refer to as interdependence in our small writing community. Students showed a shared responsibility for one another that was not evidenced in my previous courses. In regards to group work, students seemed more aware of the different abilities and perspectives that each group member was capable of bringing to the table and of each other's access needs. This was evidenced by a group of students composing a life-writing video that contained captions, audio, visual and oral modes in an effort to showcase their diverse abilities and to enable their users to experience a multimodal narrative of how their group encountered pressures of normalizing discourses. Even with individual assignments, students sought out their peers' assistance and ideas and asked for extra class time to facilitate these interactions.

I would also say that the disability-themed content might have been responsible for the generosity and kindness that the students showed me and one other. My students' desire for human community is most assuredly a product of their exposure to stigmatizing discourses of normalcy. Several of my students noted in their reading responses their gratitude for their classmates, the class material, and how the class exposed them to social injustices:

I never expected a course to surprise me… I never felt that material could catch me off-guard. I don't mean in a manner that would stupefy me or confound me but in a reflective way that touched at previously thought of standards… I could not have been more confident in my understanding of normalcy way back in August. I have now come to realize that arrogance is a bad color on me.

…advanced composition has struck me as one of the most meaningful courses. I really appreciate it because of how unique the material is….I did not realize that normalcy is such a complex concept. Luckily I was able to be in a class and learn information that I didn't know existed….It was a pleasure having classmates who are kind, understanding and very helpful.

To say my views has drastically changed would be a lie, for my eyes were hardly open, limiting what I saw….I used to be naïve, much like the rest of society. I used to have selfish tendencies, ones that had become so reactionary, so automatic, that I had hardly noticed them at all. Perhaps if I shared these tendencies with a peer that has not taken English 246 they might dismiss my self-accusations of self-centeredness as 'overthinking'. I believe if I told my college freshman self these accusations, he would have a hard time understanding.

As a teacher, it is satisfying to hear these words of awakening and change from my students' (all responses were positive, perhaps because evaluating the course was not a requirement) and to think that my own disability disclosure facilitated these responses. Yet the power of normalizing discourses and dominant narratives, especially as they relate to disability, are difficult to upset. Therefore, despite my students' personal reflections and reading responses, some of the normalizing discourses we worked on disrupting in class appeared and recirculated in their own writing.

The Hardest to Resist

Perhaps for my students, the hardest narratives to resist relating to normalcy were those of overcoming, sentiment, and inspiration. Cognitively most students recognized the difference between living with a disability and overcoming one and demonstrated this knowledge in course discussions, yet their writing responses evidenced a tension between the two. This tension was most apparent in their life-writing papers, especially for students who wrote of family members with disabilities. For instance, a student ends up reifying the narrative of overcoming and inspiration relating to disability in her own written discourse regarding her "legally blind" uncle:

His kind, gentle, and understanding personality has affected me more than he may ever know. It sucks that he is blind, but his disability has the ability to impact and affect the people around him. This makes me realize that maybe everything does happen for a reason and although we don't know the reason why he lost his vision, his loss has made the people around him, especially me, learn to appreciate and simplify life at all times.

Later in her paper, her uncle becomes the moral compass by which she judges herself and others. The same sentiment is expressed in a student's life-writing narrative regarding his brother who has Down's Syndrome. Understandably, both students recognize the problem of charity organizations objectifying persons with disabilities by reducing them to inspirational quotes and sentimental photographs and the popular trend to "allow" a "special" teenager with say, cystic fibrosis, shoot some hoops in a college state basketball game for school publicity, but are not aware of how their discourse makes similar reductions of their own loved ones.

Another contradiction emerged over what Rosemarie Garland-Thomson refers to as the rhetoric of wonderment. Mostly all of my students agreed that a freak show advertisement of an armless man writing with his toes is an act of necessity or "normal for him" and not a wonder, but could not help but being in awe of a photograph of a man in a wheelchair climbing a steep mountain. Similarly a few students who analyzed films for their art as representation papers argued that the films they were critiquing were stigmatizing and marginalizing their disabled subjects, but still found themselves in awe over the accomplishments and courage of, for example, John Forbes Nash, Jr. in A Beautiful Mind and Temple Grandin in the self-titled biopic. And, if I were to be honest, I notice in myself similar contradictions when processing my responses to popular disability representations. When my students ask if there is not a way to appreciate the accomplishments and admire the courage of someone with a disability without hero-worshipping and wonderment, I pause and need to consider. Perhaps one of the most challenging and worthwhile aspects of teaching a disability-themed course is having to constantly reexamine one's own normalizing discourses and admitting to not always "getting it right" either.

Yet, there were clear instances of students contributing to damaging discourses of normalcy within their own compositions and discourse. As the instructor, it is difficult deciding how and in what way to respond. The challenge was guiding students to recognize their own use of normalizing discourses without shaming them or forcing them to adopt my own views on normalcy. Yes, I wanted my students to conclude that norms were socially constructed and were a product of dominant ideologies, but I did not necessarily want them to subscribe to my own liberal ideology. For instance, just because I believe that sexuality is fluid and nuanced did not mean that I expected my students to feel the same way. What I did want was for them to question the assumption that heterosexuality is natural or normal and then to make their own decisions about what to believe. Of course, it was my secret hope to have my students adopt and share my convictions by critical conscious choice, but I knew that it was not my role as a teacher to make my students share my views and perhaps that is for the best. Isn't the goal of education in a democratic society to encourage different world views and provide a community in which such views can be aired without fear even if those views re-inscribe normalization? And yet, if I am enacting a critical DS pedagogy perhaps I am supposed to disrupt my students' use of normalizing discourses? I am not sure.

During class discussions, I struggled with whether or not to point out when my students were re-inscribing ablest norms. It felt less threatening to point out when students used ablest discourses in their written work rather than during class discussions. On their written work I circled sentences and phrases that contradicted the course goal to bring awareness to normalizing discourses. I was careful to phrase my written feedback as questions rather than criticisms. By doing so, I hoped the students would realize they were perpetuating hegemonic norms and to rethink their rhetoric. However, I was less likely to question their use of these norms when they expressed their reactions to readings during class discussion. Perhaps I was trying to avoid too much conflict? Perhaps I was unsure of whether it was my place to "correct" my students' beliefs and opinions, especially in front of their peers? I also recognized that most of us use normalizing and ablest discourses without realizing so or meaning harm. Taking all of this in consideration, I decided that it would be unfair to criticize students for using ablest discourses during discussions. I hoped instead that when a student expressed a normalizing viewpoint her classmates would challenge her discourse and begin a productive conversation about our automatic tendencies to use ablest rhetoric. These discussions did take place; however, was I shirking my own responsibilities as the class instructor by remaining silent?

One instance that particularly concerned me was when a student exhibited a forcibly negative reaction to a fellow student who self-disclosed with having A.D.H.D. and taking medications for treatment. The student with the negative response explained that his younger brother with A.D.H.D was "ruined" for years from similar medications. Although I tried to mitigate the conversation by making the discussion less personal, the student with A.D.H.D told me later that her classmates' reaction was the reason why she usually did not self-disclose her disability. As her teacher, I feel terribly that I failed to protect her from normalizing discourses and I wonder at what I could have done differently.

Despite finishing the internship and this article with these unanswered questions, I am not deterred by them. Teaching a disability-themed course or any other course that raises awareness of social injustices should engender questions and complications for both the instructor and the students. The fact that these questions, especially those related to re-inscribing damaging discourses, are especially pertinent to the composition classroom shows how disability studies and rhetoric and composition are united in their pedagogical aims.

Conclusion:

In regards to my own expectations of the internship class, the experience has allowed me to be one of the fortunate PhD students who want to teach not only because of a stipend, but because it makes them a better human being. As for my personal relationship to normalcy, the journey has not ended. I am still not normal; I don't imagine I ever will be. As I said earlier, powerful narratives are hard to resist and I am not naïve to think that after thirty-seven years the normalcy narrative I have been wrestling with all my life will quickly depart. And yet, being able to critique the ideology of the norm and normalizing discourses with my students has enabled me, and I hope them too, to chip away at such oppressive narratives.

As the field of disability studies continue to grow so must our approaches to teaching disability. This article reports on just one way DS teacher-researchers can incorporate critical disability studies in courses across the disciplines. In retrospect, I realize that part of the effectiveness of my "Discourses of Normalcy" class is due to the fact that I was given freedom to create the content of my internship course. As I move on to teaching other rhetoric and composition courses with more restrictions and prescribed aims and outcomes, incorporating critical disability studies in these classes will be more of a challenge. Therefore, I offer up universal design pedagogy as a place to begin. By making our classrooms and course content more accessible to a wider range of bodies we enact the very principles of disability studies that we wish to teach.

Works Cited

- Brueggemann, Brenda Jo. Lend Me Your Ear: Rhetorical Constructions of Deafness. Washington, D.C: Gallaudet Press, 2002. Print.

- Brueggemann, Brenda Jo and Debra Moddelmog. "Coming-Out Pedagogy: Risking Identity in Language and Literature Classrooms." Pedagogy, 2:3. (2002). 311-355. Print.

- Cherney, James L. "The Rhetoric of Ableism." Disability Studies Quarterly. 31.3 (2001) n.p. Web. 4 April 2015.

- Davis, Lennard. Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness and the Body. New York: Verso, 1995, Print.

- Dolmage, Jay. "Mapping Composition: Inviting Disability in the Front Door." Eds. Cynthia-Lewiecki Wilson and Brenda Jo Brueggemann. Disability and the Teaching of Writing: A Critical Sourcebook. Boston: Bedford St. Martins, 2007. 1-14. Print.

- ___ "Writing Against Normal." Composing Media = Composing Embodiment: Bodies, Technologies, Writing, the Teaching of Writing. Ed. Kristin L. Arola and Anne Wysocki. Utah: Utah UP, 2013. 110-26. Print.

- Dunn, Patricia. Learning Re-Abled: The Learning Disability Controversy and Composition. Studies. Portsmouth, Heinemann-Boynton/Cook, 2005. Print.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. "The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetoric of Disability in Popular Photography." Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities. Ed. Sharon L. Snyder, Brenda Jo Brueggemann, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomas. New York: MLA, 2003. 56-75. Print.

- Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1963. Print.

- Kerschbaum, Stephanie. "Access in the Academy." Academe. 98.5 (September-October 2012). Web. 2 February 2012.

- Kleege, Georgina. "Reflections on Writing and Teaching Disability Autobiography." Disability and the Teaching of Writing: A Critical Sourcebook. Eds. Cynthia Lewiecki-Wilson, Brenda Jo Brueggemann with Jay Dolmage. Boston: Bedford/ St. Martins, 2008. 117-123. Print.

- Lewiecki-Wilson, Cynthia and Brueggemann, Brenda Jo. Introduction: Rethinking Practices and Pedagogy: Disability and the Teaching of Writing. Disability and the Teaching of Writing: A Critical Sourcebook. Eds. Cynthia Lewiecki-Wilson, Brenda Jo Brueggemann with Jay Dolmage. Boston: Bedford/ St. Martins, 2008. 1-9. Print.

- Linton. Simi. Claiming Disability: Knowledge and Identity. New York and London: New York University Press, 1998. Print.

- Mairs, Nancy. Waist-High in the World: A Life Among the Nondisabled. Boston, Beacon Hill Press, 1996. Print.

- Nealon, Jefferson and Susan Searls Giroux. The Theory Toolbox: Critical Concepts for the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowan, 2012. Print.

- Oliver, Michael. Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice. New York: St. Martin's, 1996. Print.

- Price, Margaret. "Disability Studies Methodology: Explaining Ourselves to Ourselves." Practicing Research in Writing Studies: Reflexive and Ethically Responsible Research. Eds. Katrina M. Powell and Pamela Takayoshi. New York: Hampton Press, 2012. 159-186. Print.

- __ "Writing from Normal: Critical Thinking and Disability in the Composition Classroom." Disability and the Teaching of Writing: A Critical Sourcebook. Eds. Cynthia Lewiecki-Wilson, Brenda Jo Brueggemann with Jay Dolmage. Boston: Bedford/ St. Martins, 2008. 56-73. Print.

- Selfe, Cythina, et al. "Literacies and the Complexities of the Global Digital Divide." Ed. Sharon Miller. The Norton Book of Composition Studies. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2009. 1499-153. Print.

- Schweik, Susan. The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public. New York: New York UP, 2009. Print.

- Siebers, Tobin. Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008. Print.

- Titchkosky, Tanya. The Question of Access: Disability, Space and Meaning. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012. Print.

- Vidal, Amy. "Discourses of Disability and Basic Writing." Disability and the Teaching of Writing: A Critical Sourcebook. Eds. Cynthia Lewiecki-Wilson, Brenda Jo Brueggemann with Jay Dolmage. Boston: Bedford/ St. Martins, 2008. 40-55. Print.

- Yergeau, Melanie. "aut(hored)ism." Computers and Composition Online. (Spring 2009): n.p. Web. 5 March 2012.

- __ "Circle Wars: Reshaping the Typical Autism Essay." Disability Studies Quarterly. 30.1: (Winter 2010). n.p. Web. 5 March 2012.

Endnotes

- Jim Cherney defines rhetoricity in

"The Rhetoric of Ableism" as common sense cultural assumptions that seem to

"go without saying."

Return to Text