This essay explores issues surrounding psychiatric hospitalization through the intersection of creative writing and artmaking. The writing reflects on four artworks by the author created from appropriated hospital gowns that reflect on issues of representation and historical and contemporary experiences of hospitalization for mental disabilities including questions surrounding dignity, wellness, family, asylum tourism, psychiatric photography, and objectification.

After I enter the small conference room with the faded mismatched chairs, I am asked to hand over my cell phone, my wallet, my keys. I am then asked to remove all my clothes as the medical technician shakes my clothing, feels the waste bands, turns sleeves inside out and then back again, shakes my underwear and bra and then returns my unmentionables back to me again while keeping my other clothing. I am then handed a wrinkled pair of baggy blue pajamas, pinstriped thin cotton housecoat, and hospital gown with a strange pink amoeba-like pattern. As I leave the small room, I enter the community of the psychiatric hospital blending in among all the other patients who too have had their belongings and dignity locked away at the door.

When it is finally my time to leave the hospital, after days of watched clocks, of answering the same questions, of side effects from drugs intended to make me well, I am wearing the clothes I wore to the hospital staring at that pair of blue pajamas, pinstriped blue housecoat, and hospital gown in a rumpled ball on my bed. I consider walking down the hall and putting them in the hamper and pause. You are coming with me. I put the ball of cloth into the bottom of my hospital-issued paper bag, put my discharge paperwork on top and head for the exit knowing the over-worked staff is much less likely to be concerned with what I am taking with me than with what I came.

Hospital Gowns, inkjet on fabric stretched on canvas, each 6 " x 6", 2008. Exhibited at the Ohio Art League Annual Exhibition, Columbus, OH.

I cannot bring myself to cut the hospital gowns and pajamas from the hospital and instead take to photographing them from multiple angles rumpled into folds and creases on the floor of my home office. I order additional hospital gowns from online suppliers accumulating mounds of gowns in varieties of square and floral patterns. I print the photographed fabrics onto fabric (two of them fabrics from my own hospital stay), stretch the fabric across canvas squares, copies of copies. On the third square I overlay the face of a late nineteenth-century patient whose image was labeled, "photophobic hysteric."

The 19th century neurologist Charcot well known for his practice of photographing and chronicling "hysteric" patients represents a history of objectifying the psychiatric patient through the medical gaze (Didi-Huberman, 2003). The "photophobic hysteric" is one example of Charcot's practice of turning the camera on the "hysteric" patient. The "photophobic hysteric" who is reported to have an eye condition which causes her to turn away from the camera offers a gratifying refusal in this gesture that disrupts the gaze extended to her body. While "photophobic" refers to a sensitivty to light, her refusal becomes a sensitivity to the photographic process.

Squares of photographs become bodies in crinkled gowns standing in lines at nursing stations, in lines for food, sitting in lines of chairs staring at a television behind a layer of smudged plexiglass. An assembly-line of patients in the hospital machine hoping to arrive at the other end a product of wellness.

Lunatic Ball Gown, sewn repurposed hospital gowns, life size, 2008. Photograph published in Hospital Drive: Word, Sound, Image, 2012.

I am haunted by an early 20th century lithograph titled Lunatic's Ball depicting the patients of the Somerset County Asylum dancing for the amusement of onlookers. Often described as a recreational activity of late 19th and early 20th century asylums, depictions of lunatic's balls form a genre of artwork through which to be entertained by gazing at the "mentally ill" Other. I am reminded of Foucault's (1965) discussion of asylum tourism in Madness and Civilization and the installation of bars in the Middle Ages so onlookers could "observe the madmen chained within" and how as late as 1815 the hospital of Bethlehem exhibited patients for a penny every Sunday (p. 68).

In an 1841 letter to the The Lancet editor, the writer, who goes by the name "A Convert," describes the presence of the public at these lunatic balls and while the author describes the "safety of mixing with lunatics" and that "so complete was the triumph over apprehension, that some of the ladies unhesitatingly accepted as partners in the dance those that were patients," I am struck by the line: "On returning to my home, I could not but reflect on the moral of what I had seen." (p. 276). While the author praises that the "lunatics" were not restrained, the restraint of being in the asylum seems to be forgotten. These "inmates" do not have the luxury of returning home.

With this history in mind, I repurposed hospital gown fabrics and created a gown using a traditional gown pattern making certain adaptations. What is a girl to where to the lunatic's ball? I imagine myself now in the lunatic ball gown with the wasp-like waist of a Disney princess dancing through my daily activities, standing in the grocery line, sitting at a meeting at work, picking my daughter up from school. My skirt opening like an umbrella as I twirl. Meeting the stares. Come one, come all, to the lunatic's ball.

One Flew Over, sewn repurposed hospital gowns, approximately 8" high, 2009 Exhibited at The Birds of CAW., Columbus, OH.

The scraps of hospital gowns in my office on the desk and floor begin to remind me of the birds' nests I used to spy on as a child with my father, their fragments molding together to create a cozy new form. It is no surprise that when the women's art collective in Columbus, OH, CAW, decided to have a show centered on the theme of birds that I took to building a nest. I titled the piece, One Flew Over, thinking of the infamous film, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. I think of this dramatic portrayal of life in a psychiatric hospital compared to the monotonous and dehumanizing reality of contemporary hospitals.

The bird will not fly. It has no wings and steel pins enter and exit its body cavity fixing it to the hospital's edge. Feathers matted beneath the weight and folds of a hospital gown. For your protection. A Safe place to be. What is a bird, if not meant to fly?

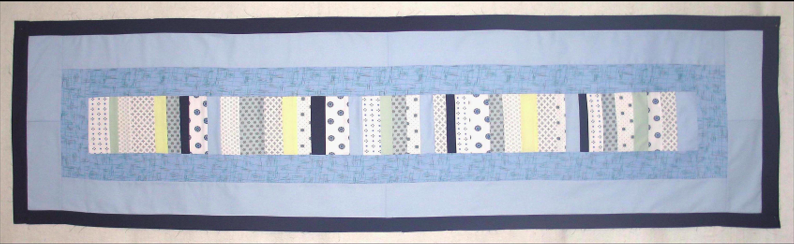

Entering the psychiatric hospital, I lose more than my clothes and belongings. Unlike medical hospitalizations, I receive few well wishes from family, friends, and colleagues. I am a forgotten person lost in the folds and creases of the institution. In She Never Sent Me Flowers, I collaborated with my mother, a quilter, to capture the monotony of days marked in time with little contact with friends and family.

Fragments of cloth mark moments of time. The heavy hands of the old industrial clocks tick seconds into minutes into days. I watch this empty chair next to me and wonder where you are.

Charles Simic once said: "Wanted: a needle swift enough to sew this poem into a blanket" (Charles Simic Quotes). Over the course of my journey with these hospital gowns, I have grown to wonder if I am searching for a needle swift enough to sew pain into a poem. I could never bring myself to cut the hospital gown and pajamas I smuggled home that day from the hospital, but have cut and reassembled many other hospital gowns diverting them from their intended destinies. Through this process, I have questioned and investigated my experiences of psychiatric hospitalization from many angles, but I do not know that I can ever regain moments of lost dignity. What I have now are my poems sewn into blankets.

References

- Anonymous (1841). Balls in lunatic asylums. The Lancet, 37 (951), 276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)81670-1

- Charles Simic Quotes. (2016). Retrieved July 6, 2016, from http://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/25415.Charles_Simic

- Didi-Huberman, G. (2003). Invention of hysteria: Charcot and the photography of the Salpêtrière. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Foucault, M. (1965). Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason. New York, NY: Vintage Books.