Analysis of publications in Disability Studies Quarterly between 2000-2012. Data and discussion concerning: the number of articles published; the number of articles collaboratively (or individually) authored; the kind and range of fields/disciplines that DSQ-published authors work in; the kind and range of methodologies generating DSQ -published research; the key terms for DSQ publications during this 13-year period (focusing both on titles and keywords). Conclusion summarizes trends and key points from the analysis and suggests a few points of further engagement for the future of Disability Studies.

Introduction

This article will offer an analysis of the field of Disability Studies as it might be constructed from publications in Disability Studies Quarterly (DSQ) between 2000-2012. The journal first began electronic publication in 2000 and by 2006 (when Brueggemann and Danforth become Co-Editors) the electronic publication began to feature a searchable index. Making use of that searchable index and other tools for data gathering and analysis, for this article we have specifically collected data on:

- The number of articles published in DSQ from 2000-2012

- The number of articles collaboratively authored

- The range of fields that the authors work in

- The methodologies used in each article

- The titles of each article

- The keywords for each article

We examined every article published between 2000 and 2012, and we collected data by looking at each individual article. Because our study yielded so much data, providing charts from each of the thirteen years of the journal that we studied would simply be overwhelming. In most cases then we have grouped the articles into two sets, 2000-2005 and 2006-2012. The benefit of this multi-year grouping is that the data is easier to understand and interpret, and it allows us to discuss the changes in DSQ across two different editorial terms.

We have collected data on DSQ specifically because it is the journal we know best. Working as the journal's co-editor for six years (Brueggemann, 2006-2012) and as its Assistant Editor for that final year (Brewer, 2011-2012), we are familiar with the way the journal has changed, what it does well, and what challenges it faces; our combined DSQ editorial experience has provided helpful context in positioning the data we have collected about DSQ 's publications over the last thirteen years. Our analysis here provides but one (just one) slice of the work being done in the field of Disability Studies overall, and we envision our study as a contribution to larger disciplinary knowledge and identity-formation that is happening internationally.

Article Count and Author Count

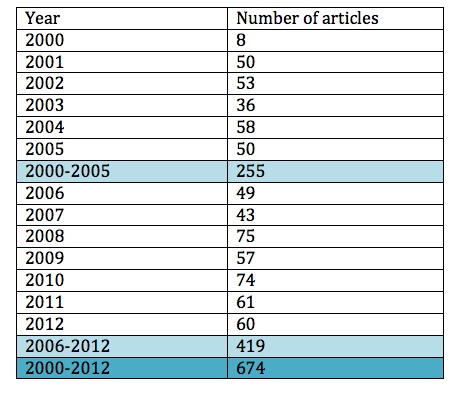

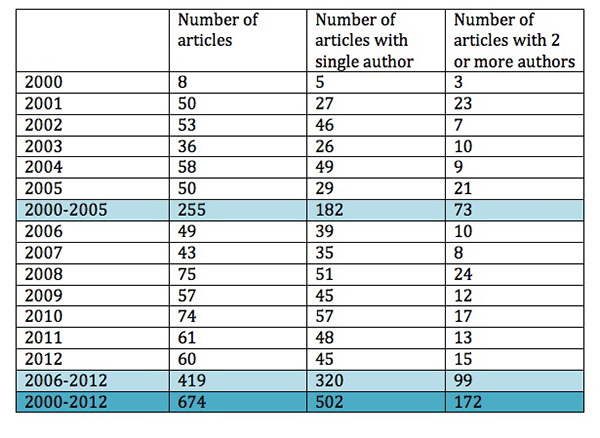

Over the past thirteen years, a total of 674 articles have been published in DSQ over 53 issues; this generates an average of approximately thirteen (13) articles per issue through that thirteen (13) year period. This count includes general articles, special issue articles, creative works, and cultural commentary. When we generated this count, we did not include prefatory matter, "From the Field" pieces that were in the earlier years of our data set, or tributes; we made the decision not to include those contributions to DSQ in our data because it would be difficult to generate methodologies or keywords for these pieces. And in the case of the "Tributes" and "From the Field" sections in particular, these were specific to the earlier 2000s, and were not continued throughout the thirteen years of the journal that we examined.

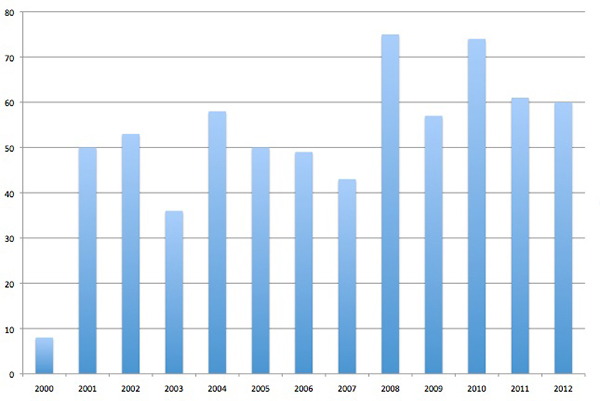

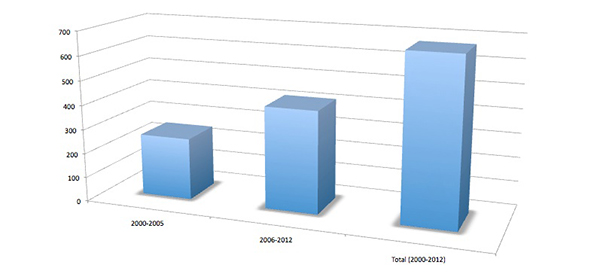

One of the trends we observed was that the number of articles published in DSQ has remained relatively stable over the thirteen-year period. Out of the 674 articles that were published between 2000 and 2012, 255 of these were between 2000 and 2005. (It is important to note, however, that only one issue from 2000 is available online, so the count for that year is only 8 articles; the articles from the other three issues during 2000 are not available online.) The number of articles published between 2006 and 2012 is 419. While this number is larger than the total count for 2000 to 2005, it is the total for articles from a 7-year period, where 2000-2005 is essentially 5 full years of the journal and 1 issue only from 2000.

The average number of articles published between 2000 and 2005 is 42.5 (although, again, this number is skewed because we only have online records for 8 articles that were published in 2000). A truer number is the average number of articles published between 2001 and 2005, which is 49.4. The average number of articles published each year between 2006 and 2012 is 59.9.

Figure 1. Count of Number of Articles Published Each Year, 2000-2012

Collaboration in the Field

When we generated a count for the articles, we were also interested in the number of articles that were collaboratively authored. We were interested in collecting this data because of our impression that the field of Disability Studies is collaborative.

Although it would impossible to know all the reasons why any particular article was single-authored or co-authored, our impression is that the conventions from different disciplines affect collaboration—possibilities and incentives for and against it—quite a bit. For example, there is greater value given to single-authored work in the humanities and the arts. Many of our primary disciplinary fields do not reward or always give us credit for promotion and tenure if we do collaborative work, so we are often only encouraged to publish single-authored pieces. On the other hand, collaborative authorship and research is highly valued in the sciences and medical fields. Perhaps the higher number of single-authored articles is more a reflection of the expectations in our primary fields, and does not always or necessarily reflect on Disability Studies as a discipline.

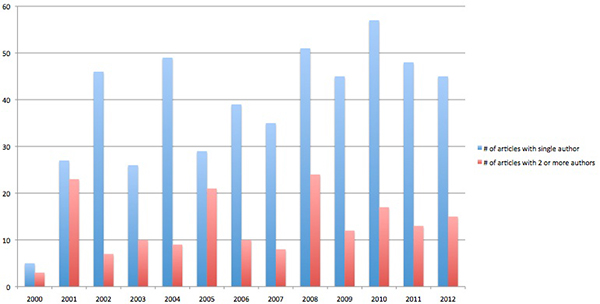

Figure 4. Count of Articles Published by Single Authors and Number of Articles Published by 2 or More Authors, 2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.)

Figure 5. Chart of Number of Articles Published by Single Authors and Number of Articles Published by 2 or More Authors Each Year, 2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.)

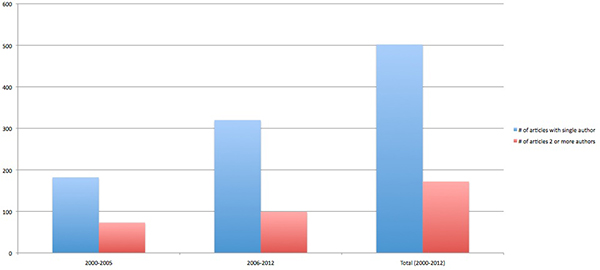

Figure 6. Chart of Number of Articles Published by Single Authors and Number of Articles Published by 2 or More Authors in Grouped Years, 2000-2005, 2006-2012, and 2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.)

Between 2000 and 2005, the articles that were single-authored account for 71.4% of the total publications, while the articles that were co-authored by two or more people account for 28.6% of the total articles published during this time period. For the years 2006 to 2012, the numbers are similar, yet with a slightly higher percentage of single-authored articles. The articles written by one author were 76.4%, while the articles that were co-authored from 2006 to 2012 account for 23.6% of the total articles published during these years. For the total range of years we collected data from, 2000-2012, 74.5% of the articles had one author, while 25.6% had two or more authors.

Authors' Fields and Methodologies of Articles

We were also interested in data on the types of articles being published in DSQ during this 13-year period (since the journal first went online). If we had been asked about the nature of the field of Disability Studies, we would have anecdotally but emphatically declared its interdisciplinary nature. The following data is intended to move us beyond the impression that Disability Studies is interdisciplinary by providing a concrete picture of just how many different fields and methodologies are represented in DSQ.

We worked in the spirit of grounded theory methodology, which means that rather than imposing our own categories about the authors' fields and the articles' methodologies onto the articles from the last 13 years, we collected data from the articles themselves to see what trends emerged in the publications from the past thirteen years. This grounded theory methodology was useful for our goals in this study because we wanted to gain a better understanding of the scholarship being published in Disability Studies, using DSQ as a case study. Our primary interest is in exploring trends that emerge from the data we have collected on articles published in DSQ.

Authors' Fields

To collect data on the authors' fields, we worked from what each author claimed as his/her own field to create the general categories that we discuss below. In other words, we did not assign a broad field (i.e. the Humanities) to any author. We recorded the field that an author claimed (i.e. Philosophy), and after recording the field/s that each author positioned him or herself in, we generated field groupings and later broader categories of these field groupings. In some cases, authors indicated their field in the article itself; if this was the case, the author's field most often appeared with their email address and name at the beginning of the article. In many cases, the author's field was not provided in the article, and we found this information by searching back to their institutional web pages.

Our initial data-gathering stage resulted in a list of 174 distinct fields that DSQ authors were working in and from! In our second stage of analyzing the data on authors' fields/disciplines, we grouped together any similar fields within our list of 174 distinct fields. This resulted in 66 field groupings. Appendix A shows the 66 field groupings, as well as the individual fields (from our list of 174 fields) that we grouped together. We do not expect that every reader will affirm our classification choices. Indeed, we understand that there are multiple ways to group disciplines, especially those that work across disciplinary boundaries (in fields such as accessibility studies, anthropology, technical writing, and public health, to name a few). We recognize the many different and interdisciplinary fields contributing the Disability Studies scholarship, and we see this as positive, and something that we do not intend to cover up by providing large categories. As such, we have included both our raw data we collected on authors' fields (See Appendix A), as well as the figures that represent the authors' fields in broader categories.

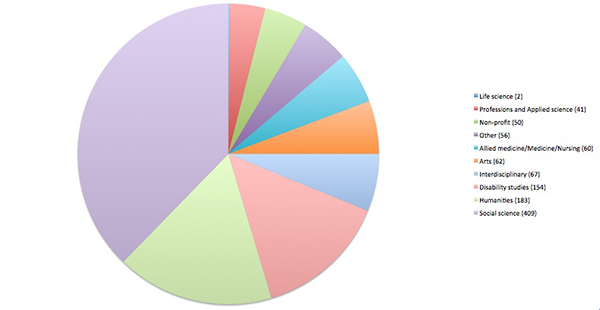

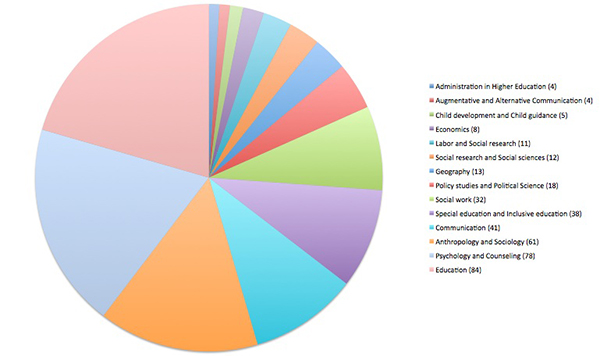

In our final stage of working with the data on authors' fields, we created even broader categories, and out of the 64 field groupings 10 general categories emerged.

The pie chart in Figure 7 illustrates that the largest grouping of authors' fields is in the Social Sciences, followed by the Humanities. The numbers corresponding to each field (i.e. 409 in the Social Sciences) indicate that 409 individual authors claim one of their primary fields as within the Social Sciences. The total numbers of individuals working with specific disciplines do not correspond to the number of total articles published; this is because some articles had more than one author, and in many cases, one author claimed to be in multiple fields, which we included in our count.

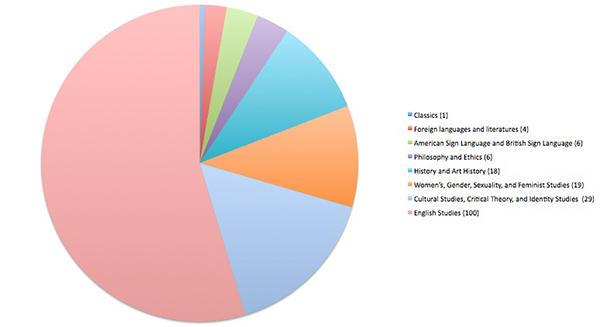

The dominance of the Social Sciences is in part due to our inclusion of Education within the Social Sciences. Cushing and Smith found that 20% of all Disability Studies programs were housed within Education departments. Indeed, in many cases, DSE (Disability Studies in Education) is referred to as its own subset of Disability Studies itself. In Figure 8a below, we show the fields that make up the category of Social Sciences. Education is the largest discipline within this category, and it is even larger if one considers that we have kept Special Education and Inclusive Education as a separate discipline within the Social Sciences. Figure 8b offers a similar disciplinary breakdown within the Humanities.

Figure 8a. Chart of Authors' Fields within the Category of Social Sciences (Click on figure to enlarge.)

The second largest grouping of authors' fields is the Humanities, which confirms much of the scholarship that cites the humanities as the core of Disability Studies. The third largest category is Disability Studies itself; the data shows that 154 authors indicated that one of their primary fields was Disability Studies. In several regards, we believe that it is quite remarkable that Disability Studies even appears as the third largest category. There are relatively few graduate programs in Disability Studies compared to older fields, and there are relatively few academic jobs that are listed as solely for Disability Studies. In most cases, Disability Studies scholars are hired into other departments, and they position themselves within multiple disciplines.

The fourth largest category is for authors working in truly interdisciplinary fields that could be grouped in no other way. These fields include, for example, Bioethics, Accessibility Studies, and Chemical Sensitivities Studies. Disability Studies could conceivably be grouped with other interdisciplinary fields, but we chose to keep Disability Studies separate because of the obvious interest that readers of DSQ have in the field.

Following interdisciplinary studies is the Arts, which is better represented in DSQ than in other academic journals. DSQ publishes creative work in almost every issue. Because of this practice, data from the journal reflect the thriving creative work within Disability Studies.

The category of Other for authors' fields encompasses independent scholars, students, individuals working in the private sector, and those whose field is unknown. In many ways, the category of Non-profit that slightly fewer authors claim is also a mix of work being done for a range of institutions. These two categories together represent the ties that Disability Studies, as an academic field, has to the general public. These categories are evidence that DSQ includes voices from outside of the academy, including disability rights activists.

The fields that are least represented in DSQ are those in the sciences and medical fields. When put in context of the history of Disability Studies, this is not surprising. As Cushing and Smith explain in their comprehensive study of Disability Studies programs (DSQ, 29.3, 2009), "DS grew largely through its critique of medical and interventionist approaches to disability, leaving it with no obvious safe space to grow in those disciplines, even though they were the traditional sites of research on disability." Although Disability Studies scholarship grew out of medical and scientific fields, it is now housed in mostly other disciplines, as both our study and Cushing and Smith's 2009 study indicate.

The category of Professions and Applied Sciences include fields such as Law, Economics, and Planning and Urban Development. We speculate that most Disability Studies work in these fields is also positioned as interdisciplinary, as a result of the institutional trend to separate disability issues from the "normal" course of study or work. For example, an Urban Planner interested in creating more accessible city spaces may claim to work within Accessibility Studies (a disability-specific field) as well as Urban Planning.

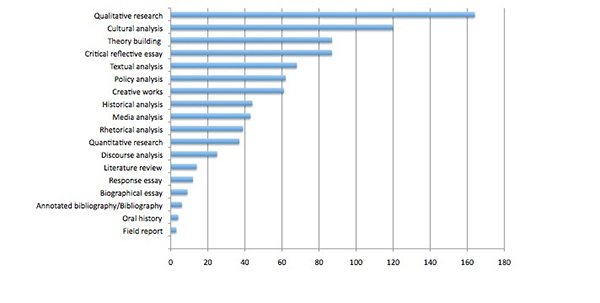

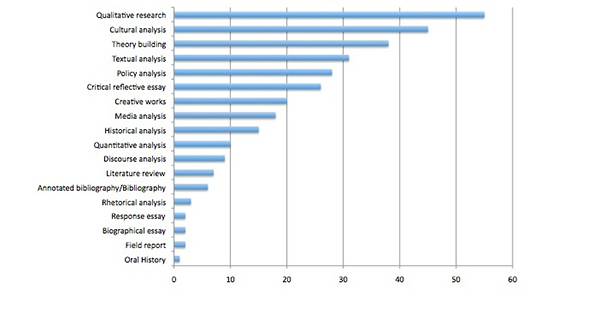

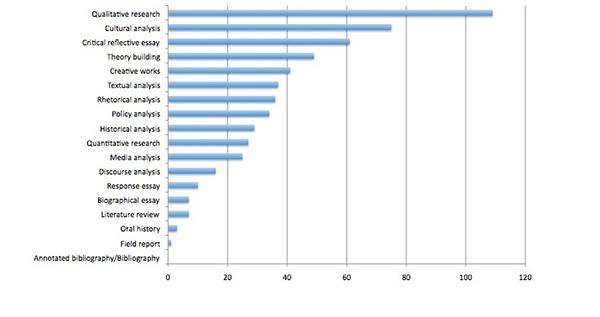

Methodologies

As will become evident in this section, the dominant methodologies used in the published research align closely with the authors' fields. Our approach to generating methodologies emerged from the articles themselves, in a process influenced by grounded theory. We assigned one or more methodology to each article after reading it, and if we encountered a methodology that we had not seen in another article (for example, literature review or field report), we added it to our list of possible methodologies. Our list of methodologies emerged from the research approaches we observed in the articles; we did not apply a pre-fabricated list of methodologies to the articles themselves. However, we did group together some of the methodologies in the following ways, for the ease of presenting the data:

Qualitative research includes:

- Case study

- Ethnography/Participant observation

- Focus groups

- Interviews

- Participatory action research

- Surveys

Creative works include:

- Creative nonfiction

- Fiction

- Poetry

The frequency of particular methodologies throughout the last thirteen years of DSQ is related to the authors' fields and the type of research that is typically done in a particular field. From this perspective, it is not surprising that the most common methodology used is qualitative research, which is valued and frequently used in the Social Sciences. It is also perhaps to be expected that many text-based methodologies would be used, given the large number of authors in the Humanities that have published in DSQ. Many of the methodologies in the chart above are frequently used in the Humanities: cultural analysis; critical reflective essays; textual analysis; policy analysis; creative works; historical analysis; media analysis; discourse analysis; literature review; response essay; biographical essay; and oral history.

Another influence on the methodologies is the journal itself and the types of submissions it accepts. Of particular note is the large number of creative works, cultural analysis, critical reflective essays, and response essays, which are regular features in the journal.

There are some consistencies in methodologies across the 2000-2005 years and the 2006-2012 years, namely that the most frequently used methods are qualitative research. Another common methodology across both sets of years is cultural analysis because of the featured section on cultural commentary that appears in many issues of DSQ.

But there are also some distinct differences in the use of particular methodologies during the 2000-2005 years and then during the 2006-2012 years. For example, there is a rise in critical reflective essays, from 26 during 2000-2005 to 61 during 2006-2012. Critical reflective essays are those that draw on personal experience to contribute to scholarly discussions going on in the field of Disability Studies. Our expectation, had we not collected this data, would have been to guess that such personal writing would be on the decline over the years. As DSQ has moved away from personal writing in the form of Tributes, we might expect more research and less personal exposition. But personal writing is—has been and remains—a staple of the field of Disability Studies. The practice of valuing and including the personal is also reflected in some of the field's anthologies. One of the particular reasons for the large number of critical reflective essays in the 2006-2012 DSQ years is that the 2007 issue on Blogging included pieces that were almost solely critical reflective essays (some of these essays used other methodologies too). We were also careful in our examination of methodologies to look for multiple methods within one article, and often times one of these methods was a personal reflective piece. As our data demonstrates, there is often not a binary between personal writing and scholarly writing in Disability Studies, and we wanted to record both as we gathered data on the methodologies used by authors.

Some particular increases in methodologies during the 2006-2012 years can be attributed to special issues that were published. The rise in creative works from 20 during 2000-2005 up to 41 during 2006-2012 is in part because of the 2008 special issue on Poetry. There were 12 creative works from that issue alone. And the rise in rhetorical analysis as a method can be attributed to the 2010 special issue on Disability and Rhetoric, which included 17 articles. Finally, the somewhat smaller rise in response essays is due in part to the 5 responses to (editorially gathered) responses to the 2009 Cushing and Smith "multinational" study of Disability Studies programs. This particular format for an issue—publishing a large study like Cushing and Smith's and soliciting responses to it—is unique to that particular issue of DSQ. While special issues bring particular methodologies and topics into the spotlight, the rise in particular methodologies and areas of research is also evidence that much work of this kind is already being done in Disability Studies. The many articles that were published in the special issue on Disability and Rhetoric, for example, reflects back to the field that rhetorical analysis is a viable methodology for conducting research in Disability Studies.

Titles 1 and Keywords

Quantitative research, as we have shown in our count of articles, authors' fields, and methodologies, tells only part of the story of work being done. To tell another part of the story, in this section we have completed qualitative research to represent the titles and keywords of all the articles published in DSQ between 2000 and 2012. We have chosen to represent the titles through Wordle™, because a graphic "Wordle" visually represents various trends in topics that are discussed in the journal. A Wordle diagram works by associating word size with the number of times a specific word gets mentioned. As the Wordle Web site (http://www.wordle.net/) explains:

Wordle is a toy for generating "word clouds" from text that you provide. The clouds give greater prominence to words that appear more frequently in the source text. You can tweak your clouds with different fonts, layouts, and color schemes.

Thus, in our DSQ Wordles, the larger a word is in the Wordle, the more times it has been mentioned in the titles and keywords from DSQ in a particular period. A particularly large word in a Wordle should be understood as a very important term because it has been used frequently by a range of different contributors to DSQ.

When we generated Wordles based on the titles and keywords in DSQ, we chose specific parameters with clarity and readability in mind. For example, each Wordle is limited to a display of 100 relevant words, and common English words were excluded, such as "and," "or," and "it." This was done for ease of viewing and to focus on the most relevant terms. Since Wordles, by nature, do not provide a count of data in the way that tables and graphs do, we imagine (and hope) that each viewer will find different terms of interest in each Wordle. We often find that different terms stand out to us as we revisit the Wordles at a later time. While different terms will undoubtedly strike different readers as relevant, we discuss some of the trends we see represented in each of the Wordles. Our intent in this section is to visually document elements of change in the focus of the DSQ articles over the 13-year period and to provide thoughts on why these changes occurred.

Note: In the following discussion, we provide a brief caption for each Wordle, but we also analyze all Wordles and associated terms within the article itself.

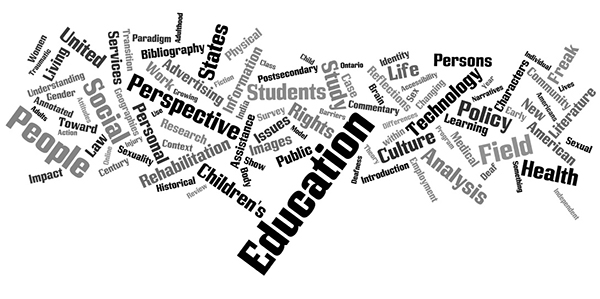

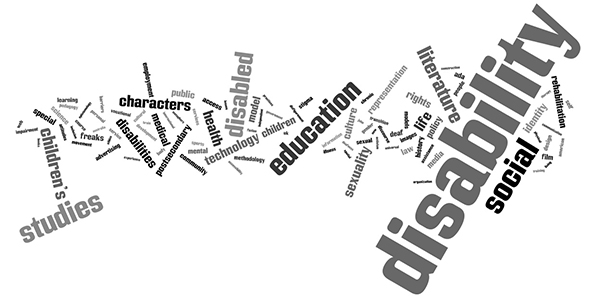

Figure 12a. Wordle of Titles from Articles, 2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the titles of articles in DSQ from 2000-2012. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as disability, education, people, and rights—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

The first thing we noticed about the Wordle that includes titles from 2000 to 2012 is that the word disability is so large. While this word is prominent in each of the Wordles, and this makes sense because it is part of the journal title and likely to be used by many authors, it is worth noting that the word disability has been chosen over other possible terms. We might look at what other terms do not appear in the Wordle, such as handicap or impairment. Because the words handicap and impairment signal a medical view of disability, their absence in most of the titles published in the last 13 years of DSQ indicates that most contributors have taken a perspective that is interested in disability as something other than simply a medical "problem." Articles that are situated in this way are in line with the journal's description:

[DSQ] is a multidisciplinary and international journal of interest to social scientists, scholars in the humanities, disability rights advocates, creative writers, and others concerned with the issues of people with disabilities. It represents the full range of methods, epistemologies, perspectives, and content that the multidisciplinary field of disability studies embraces. DSQ is committed to developing theoretical and practical knowledge about disability and to promoting the full and equal participation of persons with disabilities in society (Disability Studies Quarterly, 2012).

When we examine other words that appear large in the Wordle, we can grasp further a sense of the type of research currently done in DSQ. Words such as cultural and commentary, for example, appear much larger than health. And medical or medicine does not appear at all. DSQ has frequently published cultural commentary pieces, and the prominence of these two words, in combination with words like reflections, critical, response, perspective, and identity, further supports what our data has shown about the significant amount of work being done in the Humanities related to disability.

Some of the prominent words in this Wordle are such because they represent themes of special issues of the journal. Words such as autism, rhetoric, poem, education, freak, and law are examples of words that were used frequently because entire issues were devoted to these ideas. These special issues are understandably about a wide range of topics, but what we can glean from their appearance in the Wordle is that Disability Studies research intersects with almost any other field. The very fact that a special issue on any one of these topics was published in the last 13 years also demonstrates that enough scholarship was being done in that area for a slate of peer-reviewed articles to create a critical mass for publication.

One final note about all of the Wordles is that, because of the nature of Wordles and how they organize information, some words appear separately that should actually go together. Examples of these pairs of words that have been split up are disability studies, United States, cultural commentary, and special education. It may be confusing to consider united by itself, without the knowledge that when it is paired with the word states, it shows us that much of the scholarship in DSQ is focused on disability issues within the United States. Remembering that some words should be grouped together can facilitate easier understanding of the Wordle.

For another perspective of the major Wordle that represents all of the key terms from 2000-2012, we've removed "disability" from the generated word cloud in Figure 12b below.

Figure 12b. Wordle of Titles from Articles ("Disability" Removed), 2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the titles of articles in DSQ from 2000-2012; however, the term disability and its variations, as well as the term studies, have been removed. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as communication, social, poem, and commentary—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

Figure 13a. Wordle of Titles from Articles, 2000-2005 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the titles of articles in DSQ from 2000-2005. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as disability, education, health, and perspective—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

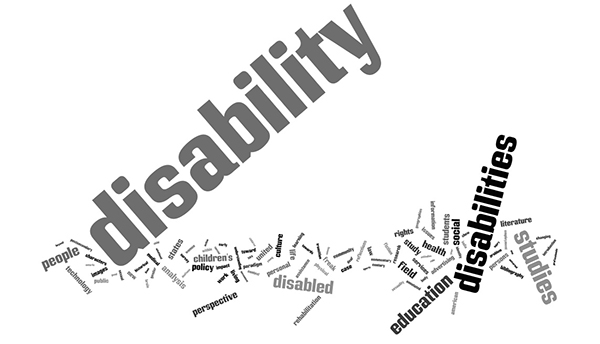

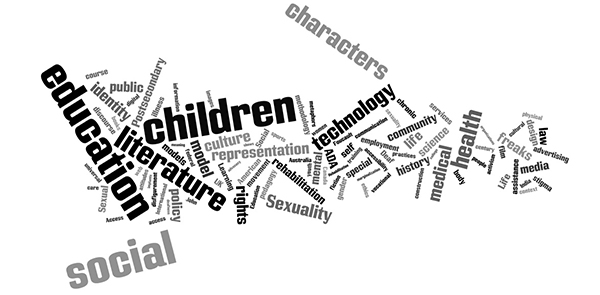

The Wordle that isolates the titles in DSQ from 2000 to 2005 represents a period of time that includes the 10-year anniversary of the passage of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The 10th anniversary of the ADA's passage was marked by a national refocusing on disability issues, a celebration of progress made as a result of the ADA, a call for further revision of the law, and a sharing of stories by many people of how the ADA influenced their lives positively. If we keep in mind the historical significance of the ADA, it makes sense that the Wordle from this time period includes words from titles that suggest a political interest. Examples include words such as social, policy, rights, assistance, states, American, law, public, and services. Specific examples of articles that focus on the ADA are Martin Gould's 2004 commentary titled "Assessing the Impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act," and the 2005 book reviews by Art Blaser and Heather Munro Prescott of Ruth Colker's book, The Disability Pendulum: The First Decade of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Greg Perry's book, Disabling America: The Unintended Consequences of the Government's Protection of the Handicapped. When a search is conducted for the term "ADA" within DSQ, 82 results come up, demonstrating that many articles actually refer to the ADA, even if the term does not always appear in the article's title.

Another trend in terms used in article titles between 2000 and 2005 are the words technology and information. Both of these terms appear relatively large in the Wordle, which can be attributed to the growing work in a variety of disciplines that at this time became focused on the effects of new media on culture, communication, and identity. Interestingly enough, DSQ went from being a print journal to an online journal in 2000. The history of the journal itself reflects the importance that new media has had on ideas across disciplines.

We might group some of the words that appear in this Wordle together, as contributing to a particular viewpoint that is largely represented during the years 2000—2005. For example, the terms new, paradigm, and models suggest that contributors to DSQ during this time had a self-awareness that their writing was proposing a new way of looking at disability issues. We might consider, as one example, the 2005 article by Vandana Chaudhry and Tom Shipp titled "Rethinking the Digital Divide in Relation to Visual Disability in India and the United States: Towards a Paradigm of 'Information Inequity'"; here the co-authors are quite self-consciously moving away from previous ideas.

Figure 13b. Wordle of Titles from Articles ("Disability" Removed), 2000-2005 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the titles of articles in DSQ from 2000-2005; however, the term disability and its variations, as well as the term studies, have been removed. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such education, social, children's, and technology—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

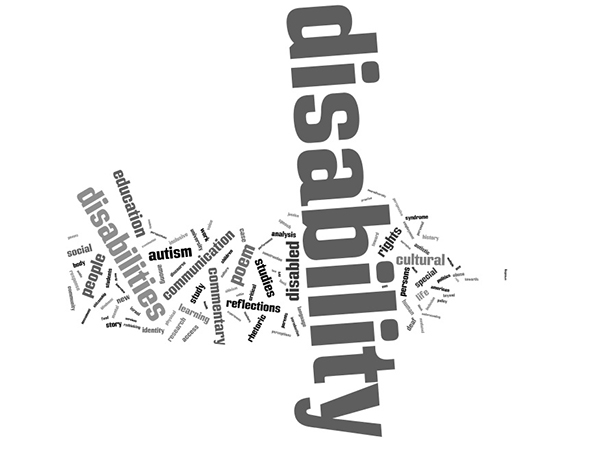

Figure 14a. Wordle of Titles from Articles, 2006-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the titles of articles in DSQ from 2006-2012. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as disability, autism, cultural, and rights—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

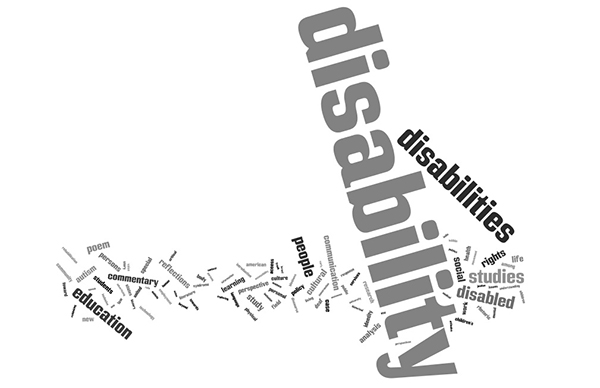

As we noted in the Wordle for the titles from all the issues between 2000 and 2012, here again between 2006 and 2012 the largest words reflect special issues that were published. These special issues are of interest to our survey of publications in the field of Disability Studies because their topics point to timely issues in the field. For example, the word autism appears not just because of the 2010 special issue on Autism and the Concept of Neurodiversity, but also because in recent years interest in Autism has grown exponentially and the disability community has had much to say. There have been a number of articles published that relate to Autism in other issues of DSQ, particularly the 2011 special issue on Disability and Rhetoric, but also in some of the general issues.

Similar to the prominence of the word autism in this 2006—2012 Wordle, poem also appears as being important during this time. In 2008, there was a special issue on Poetry, indicating that a large enough body of poetry related to disability existed for a peer-reviewed issue in DSQ to be published. For example, Jim Ferris, who wrote the introduction for the special issue, had already published the award-winning Hospital Poems in 2004, and Kenny Fries and Stephen Kuusisto had been publishing disability poetry throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Aside from the special 2008 issue on Poetry, DSQ frequently publishes poems and other creative works. In sum, one thing that the prominence of poem in this Wordle documents is that creative work has had a major presence in Disability Studies in recent years. We might also view the presence of words like rhetoric, communication, language, and reflections as an indication that scholars are interested in issues of representing oneself and others. How we do (and should or shouldn't) talk about disability is as much a part of Disability Studies as topics like the ADA, new media, and poetry. In support of this point, we could cite Curt Dudley-Marling and Patricia Paugh's 2010 article titled "Confronting the Discourse of Deficiencies" that examines the language used to talk about students with learning disabilities. No doubt, other groups of words within the Wordles can be found that suggest particular relationships and important ideas. And we hope readers will find their own examples as they explore each of the Wordles.

Figure 14b. Wordle of Titles from Articles ("Disability" Removed), 2006-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the titles of articles in DSQ from 2006-2012; however, the term disability and its variations, as well as the term studies, have been removed. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as education, commentary, autism, and poem—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

Keywords

In recent years, DSQ has made a commitment to collecting keywords from authors. One of the main motivations for doing so is to have an on-going collection of data about the articles being published in DSQ. Keywords provide the main topics that are discussed in an article, so collecting the main topics on everything published in the journal provides a better sense of the work being done in the interdisciplinary field of Disability Studies. Other reasons for DSQ to include keywords are more immediately practical; keywords (and abstracts) give readers a preview of an article before reading it, and keywords help the website's search function return more accurate results. In short, when authors provide keywords with their articles, it provides an at-a-glance understanding of what scholarship looks like in the growing field of Disability Studies, both for readers of DSQ and for researchers collecting data about the field.

One type of data we collected in our study of DSQ was the keywords because they provide an impression of what is being written about. They give us a view of the scholarship in DSQ that allows us to triangulate claims that we've made based on trends we see in methodologies, titles, and authors' fields. However, before we could collect keywords, we first needed to take stock of how many articles already had keywords and how many did not. This became interesting data in itself (see Figures 16 and 17 below). Most of the articles published before 2011 did not have keywords. And closer examination of those early articles that did include keywords showed that they varied greatly; some authors included one keyword and others had eight or more. As online platforms for scholarship have become more commonplace, keywords have become a more important part of the articles. By the middle of 2012, it had become routine that the editors asked all authors to submit 3-5 keywords and an abstract prior to publication of their articles.

Because our study of DSQ focuses on articles published between 2000 and 2012, and because keywords have only recently become a formal part of the published articles in the journal, any data on keywords published in the last thirteen years would not provide a complete picture of the topics that the articles cover. Rather than working with an incomplete record of keywords, we have generated keywords for the articles whose authors did not include them. This part of our project is of a somewhat different nature than the other parts because we did not simply collect and compile existing data, but we created data to fill in a missing history of the scholarship in Disability Studies.

For every article that did not include keywords, we generated between three and five keywords for the article. We did not generate keywords for creative works (we initially tried, but after our first attempt at generating keywords for a poem, we realized this was an impossible task!), so we included the count of those publications that neither had keywords nor had keywords generated for them by us.

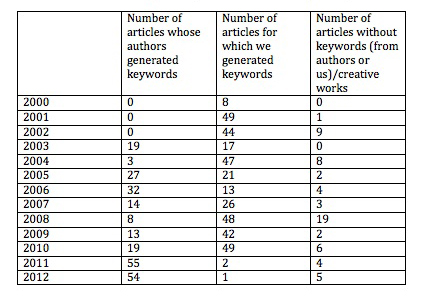

Figure 15.

Count of Articles by Year Whose Authors Provided Keywords,

Articles for which We Generated Keywords,

Articles Without Keywords,

2000-2012

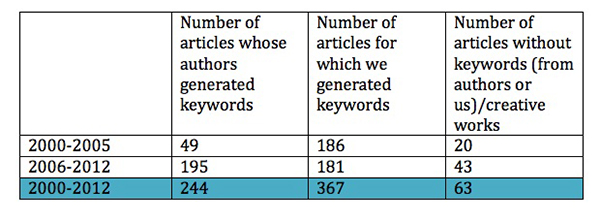

Figure 16.

Count of Articles by Grouped Years Whose Authors Provided Keywords,

Articles for which We Generated Keywords,

Articles Without Keywords,

2000-2005, 2006-2012, and 2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.)

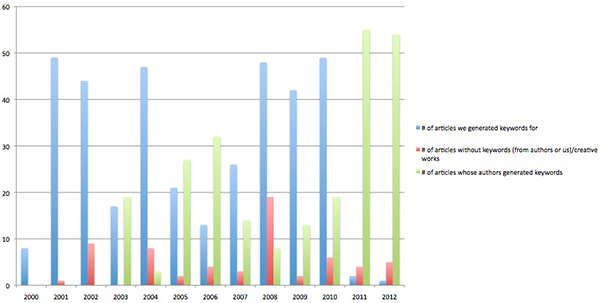

Figure 17.

Chart of Articles by Year Whose Authors Provided Keywords,

Articles for which We Generated Keywords,

Articles Without Keywords,

2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.)

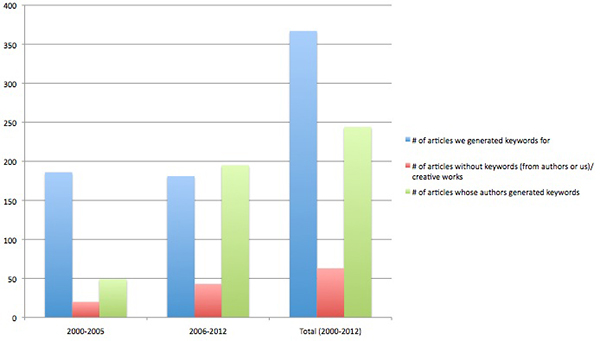

Figure 18.

Chart of Articles by Grouped Years Whose Authors Provided Keywords,

Articles for which We Generated Keywords,

Articles Without Keywords,

2000-2005, 2006-2012, and 2000-2012

The data we generated for keywords is unlike any of the other data in this study because it reflects a combination of author-generated keywords and keywords that we generated. Because of the different origins of the keywords, we opted to represent the data by using Wordles, rather than, say, counting the number of articles that had a particular keyword listed (i.e. disclosure). We used the same limiters that we did for the Wordles of the titles, so the following Wordles include only the 100 most common keywords (for the sake of readability) and they do not include common English words (i.e. "and," "or," "a," "the"). Our hope is that DSQ will continue to require author-generated keywords, and a future study can find trends in common keywords and ways that authors represent their own work.

Figure 19a. Wordle of Keywords for Articles, 2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the keywords of articles in DSQ from 2000-2012. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as disability, social, identity, and representation—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

The Wordle reflecting keywords between 2000 and 2012—the entire range of our study—includes more keywords generated by us than those generated by authors. As the tables above show, there were 584 articles (not including creative works) that were published in DSQ between 2000 and 2012, of which 244 had keywords generated by the authors, and we generated keywords for the remaining 367 articles. The ratio between author-generated keywords and the keywords generated by us provides an interesting perspective on the prominence of the term disability because we tended not to list disability as a keyword. Our rationale for doing so was that it is assumed that all of the articles published in DSQ are about disability in some way, so it is not a particularly descriptive keyword or search term. We think that the prominence of disability in the Wordle is worth considering then. Its size indicates that it is the single most common keyword for the articles published between 2000 and 2012, and we have a few ideas about why this might be the case.

One theory about the common listing of disability as a keyword is that many authors are situated within a primary field other than Disability Studies, and because of this major disciplinary location, the tendency exists to call attention to work that is specifically about disability. In our minds, we might view our work in Disability Studies as separate from the work of our primary fields. Another theory we have about why disability is a common keyword is that disability studies is often listed as the full keyword because many articles are contributing to definitions of the field or to theories and models of disability.

In comparison with the data we have collected on authors' fields and methodologies, this keyword Wordle provides another view of how truly interdisciplinary the field of Disability Studies is. Because the Wordle only includes the top 100 keywords, the more specific and less frequent words are left out (for example, Million Dollar Baby doesn't appear in the Wordle, although it is a keyword, but Film does appear). Many of the keywords that do appear, then, are reflections of the fields that Disability Studies work intersects with. For example, we might think of many of the keywords in the Wordle as being able to complete the phrase "Disability and…[Education/Gender/Policy/Race/Rhetoric/etc.]."

Figure 19b. Wordle of Keywords for Articles, ("Disability" Removed), 2000-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the keywords of articles in DSQ from 2000-2012; however, the term disability and its variations, as well as the term studies, have been removed. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as social, rights, policy, and education—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

Figure 20a. Wordle of Keywords for Articles, 2000-2005 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the keywords of articles in DSQ from 2000-2005. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such disability, literature, characters, and social—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

In the Wordle for the keywords from articles published between 2000 and 2005, there is less of a disparity between the size of the word disability and other keywords, although disability is still the most common keyword. As we explained above, this is likely due to our own tendency not to list disability as a keyword, since every article is about disability in some way.

The keywords from DSQ articles published during this time period can be grouped together to provide a sense of major conversations in the field during those years. Some of the keywords that appear to be related are:

ADA, law, policy, government

Employment, vocational, rehabilitation

Barriers, inclusion, accessibility, access, universal, design, construction, technology

Culture, cultural, identity, self, representation, personal, sexual, sexuality, gender,

Postsecondary, education, learning, pedagogy, epistemology

Stigma, attitudes, inclusion,

Representation, web, media, advertising, technology, books

Models, social, medical

Figure 20b. Wordle of Keywords for Articles, ("Disability" Removed), 2000-2005 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the keywords of articles in DSQ from 2000-2005; however, the term disability and its variations, as well as the term studies, have been removed. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as health, medical, freaks, and sexuality—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

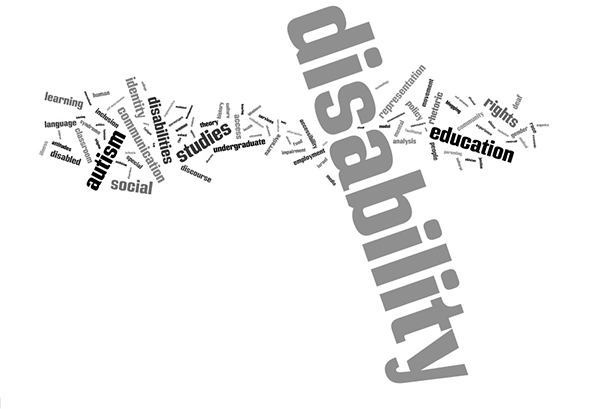

Figure 21a. Wordle of Keywords for Articles, 2006-2012 (Click on figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the keywords of articles in DSQ from 2006-2012. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such as disability, undergraduate, representation, and discourse—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

The prominence of disability as a keyword is in line with our sense that authors included disability as a keyword more often than we did when we generated keywords for articles. In the articles published between 2006 and 2012, authors generated their own keywords more commonly than we generated keywords for the articles. We see, then, that the most common keyword listed by a large margin is disability.

As we did for previous Wordles, we view this one with an interest in trends that it reveals. We see it as one answer to an inquiry about what conversations dominated the discipline of Disability Studies between 2006 and 2012. Some of the trends that appear from this Wordle are:

Learning, education, classroom, undergraduate

Blogging, technology

Narrative, discourse, language, rhetoric

One of the commonalities across all three of the keyword Wordles is that the term mental appears. We attribute this in part to the 2012 special issue on Disability and Madness and to increased scholarship within Disability Studies on psychiatric disabilities and developmental disabilities. However, we are struck by appearance of the term mental in relation to the term physical, which does not appear in the Wordles. The absence of the qualifier physical in the term physical disability perhaps does not need to be included as a keyword because it is implied. Along the same lines, the terms Autism, Deaf, and Deafness are visible in each of the Wordles, and we wonder if by calling these terms out as keywords it doesn't suggest that they are somehow different than the expected conversation about disability. We wonder if because these are seen as terms that categorize an article and set them apart from other articles, if they don't map debate lines in the discipline of Disability Studies. For example, scholars such as Bradley Lewis and Peter Beresford have written about the tenuous place of psychiatric disability within Disability Studies scholarship. Autism and Deafness also occupy unique relationships to Disability Studies, overlapping in support for disability pride, culture, and identity, but fitting uncomfortably into discussion about impairment.

Each time we would return to the Wordles, new relationships between terms and topics seemed to appear. We hope that readers will find their own relationships between terms as they examine the Wordles.

Figure 21b. Wordle of Keywords for Articles, ("Disability" Removed) 2006-2012 (Click figure to enlarge.) This is a Wordle created from the keywords of articles in DSQ from 2006-2012; however, the term disability and its variations, as well as the term studies, have been removed. It demonstrates the significance of certain terms—such classroom, rhetoric, access, and history—as they appeared in weight and frequency during this period.

Rear View but Forward too

In looking back over our data, and considering both the process of its collection and analysis, a few outstanding themes and thoughts seemed to emerge from this study of articles published in DSQ between 2000-2012.

First, there is the dominance, and consistent reoccurrence of, certain terms in the Wordles. Disability, most notably and seemingly quite natural (along with its variants, "disabled" and "disabilities," plural). Yet the admittedly self-conscious need to call out this term, even in a journal dedicated to work in this field, raises (and begs?) the question of why such a self-conscious name-calling remains in need. Other terms appear with regularity and weight throughout these thirteen years of DSQ publication (in alphabetical order here):

access

accessibility

autism (particularly for the 2006-2012 period)

children

communication

community

culture

education (arguably, the second biggest term next to disability)

employment

history

identity

literature

medical

policy

representation

rights

sexuality

social

technology

A valuable keyword project for the field of Disability Studies surely exists in a more extended study of any or all of these terms.

Second, we could not help but notice the refreshing diversity of methodologies employed in "doing Disability Studies." Our study coded for eighteen (18) different methodologies in this thirteen-year period and while qualitative studies is clearly the staple of our field, there are significant movements that seem to be happening with the growth of "cultural analysis" approaches and the rise of the "critical reflective essay." "Theory building" also shows a strong hand in the past thirteen years of our field's growth. More sustained analyses of any or all three of these rising methodologies in our field's work would surely make for a meaningful research project. Why are these methods so readily engaged now in studying disability? What suppleness and strengths do they present? From another (and somewhat opposite) angle, we might also consider why "oral history" is not in use more—especially given the emphasis that clearly still remains on personal narrative and experience-based texts in our field. What are the elements or issues in doing "oral history" that seem to keep it in low profile among our available methodologies? Finally, it seems that even a large-scale collection that would bring together a rich discussion about all the available means of disability studies methodologies is now much needed in our field.

A third rearview glance but forward-looking outcome of our thirteen-year study of DSQ's articles focuses on the nature and weight of collaboration (co-authoring) in our field. In our view, there was a (surprisingly) low percentage of collaboratively authored articles when the final tally was completed. Given the inter-, multi-, and cross-disciplinary nature of Disability Studies, the relative paucity of collaboration in our publications—and the preponderance of individually authored articles—seems to exist in considerable tension. How might we further sustain, maintain, and en/courage collaboration (especially cross-disciplinary collaboration) as we continue to grow the field?

In considering ways to further foster cross-disciplinary collaboration in Disability Studies, some possibilities might come in nurturing more conversations between the Social Sciences and the Humanities. This fostering would be a fourth look back and view forward we suggest from our study. Rather than (continuing to) point out the disciplinary divide between these two larger academic domains, how might bringing them into the same room more often generate even more good research from shared discussions they might have over "disability"—as condition, identity, rights, lived experience, culture, metaphor, material reality, etc.? Can we stage conferences, symposia, courses, journal issues that work more to break up the camps—social scientists here, humanists and artists there—and put us all around the same campfire more often? Perhaps we might even make better use of the field of "Education"—which clearly appeared as a dominant force in Disability Studies in the last thirteen years (from the pages of DSQ) —as a location for bringing social scientists to the table with humanists in powerful cross-disciplinary conversations over those terms (see above) that clearly seem to matter to all of us?

The special issues often featured in DSQ offer another location for such cross-disciplinary conversations. Our fifth conclusion comes in the unquestionable impact that special issues have on that journal (and thus, we are sure, on our field). Going forward, in the growth of our field, how might special issues (such as this one on growing our field!) consciously, carefully, and creatively do even more work to engage rich inter-, multi- and cross-disciplinary approaches to a "special" topic?

Finally, we conclude by suggesting that the work of keywords —in calling out both topics and methodologies—is significant in mapping the past, the present, and the going/growing forward of Disability Studies.

Works Cited

- Blaser, Arthur. Rev. of The Disability Pendulum: The First Decade of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Disabling America: The Unintended Consequences of the Government's Protection of the Handicapped. by Ruth Colker and Greg Perry. Disability Studies Quarterly 25.4 (2005): n.pag. Web. 1 Mar 2014.

- Brueggemann, Brenda Jo, Elizabeth Brewer, Nicholas Hetrick, and Melanie Yergeau. Arts and Humanities (The SAGE Reference Series on Disability: Key Issues and Future Directions). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2012. Print.

- Chaudhry, Vandana and Thomas Shipp. "Rethinking the Digital Divide in Relation To Visual Disability in India and the United States: Towards a Paradigm of 'Information Inequity'" Disability Studies Quarterly 25.2 (2005): n.pag. Web. 1 Mar 2014.

- Cushing, Pamela and Tyler Smith. "Multinational Review of English Language Disability Studies Degrees and Courses." Disability Studies Quarterly. 29.3 (2009): n.pag. Web. 1 Mar 2014.

- Dudley-Marling, Curt and Patricia Paugh. "Confronting the Discourse of Deficiencies." Disability Studies Quarterly. 30.2 (2010): n.pag. Web. 1 Mar 2014.

- "Editorial Policies." Disability Studies Quarterly. The Society for Disability Studies and The Ohio State University, 2013. Web. 1 June 2012.

- Gould, Martin. "Commentary: Assessing the Impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act." Disability Studies Quarterly. 24.2 (2004): n.pag. Web. 1 Mar 2014.

- "Home." Wordle. Jonathan Feinberg, 2013. Web. 1 Mar 2014.

- Prescott, Heather Munro. Rev. of The Disability Pendulum: The First Decade of the Americans with Disabilities Act. by Ruth Colker. Disability Studies Quarterly 25.4 (2005): n.pag. Web. 1 Mar 2014.

Endnotes

- The data and discussion of the Titles from DSQ is adapted from Chapter 5 of the Arts and Humanities Volume of The SAGE Reference Series on Disability: Key Issues and Future Directions. Brueggemann and Brewer co-authored this volume along with Nicholas Hetrick and Melanie Yergeau.

Return to Text

Appendix A

Code for Author's General Field |

Authors' Fields in Groups |

2000-2005 |

2006-2012 |

Total (2000-2012) |

Interdisciplinary |

Accessibility Studies (Assistive technology, adaptive technology research, universal design, telecommunicationand technology policy initiatives) |

3 |

5 |

8 |

Social science |

Administration in Higher Education |

2 |

2 |

4 |

Professions and Applied Sciences |

Advertising |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Non-profit |

Advocacy and Activism |

8 |

29 |

37 |

Humanities |

American Sign Language and British Sign Language |

1 |

5 |

6 |

Social science |

Anthropology and Sociology (Medical anthropology) |

22 |

39 |

61 |

Arts |

Arts (Dance, Film director, Film editor, film producer, music, performing arts, performance studies, theater) |

7 |

10 |

17 |

Allied medicine/medicine |

Audiology (Speech and Hearing, Speech language pathology) |

4 |

11 |

15 |

Social science |

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Facilitated communication, mediated communication |

0 |

4 |

4 |

Interdisciplinary |

Bioethics |

2 |

1 |

3 |

Life science |

Biology (Zoology) |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Allied medicine/Medicine |

Biostatistics and Disability Research |

3 |

1 |

4 |

Interdisciplinary |

Chemical sensitivities |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Social science |

Child development and Child guidance |

1 |

4 |

5 |

Professions and Applied Science |

Childcare |

0 |

4 |

4 |

Humanities |

Classics |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Social science |

Communication (technical communication, journalism) |

17 |

14 |

41 |

Interdisciplinary |

Community health (public health, environmental and occupational health science) |

8 |

6 |

14 |

Humanities |

Cultural Studies, Critical Theory, and Identity Studies (American, Canadian, Hispanic, Lakota, Jewish, African, African American, Asian American, Postcolonial, Liberal studies, Popular culture studies, critical theory, critical trauma studies) |

8 |

21 |

29 |

Interdisciplinary |

Disability Services and Diversity Services (ADA Coordinator, Veterans Affairs, Multicultural counseling/diversity centers) |

8 |

3 |

11 |

Disability studies |

Disability Studies (Deaf studies, Neurodiversity) |

51 |

103 |

154 |

Social science |

Education (Early childhood, educational counseling, educational development, education leadership and policy, learning and development, social justice education, teaching and learning, teaching and leadership, educational psychology, art education) |

34 |

50 |

84 |

Social science |

Economics (Microfinance) |

1 |

7 |

8 |

Humanities |

English (English as a second language, Literature, Literacy studies, Rhetoric and Composition, Writing Center Administration) |

23 |

77 |

100 |

Humanities |

Foreign languages and literatures (German and African) |

3 |

1 |

4 |

Social science |

Geography (human geography, medical geography) |

12 |

1 |

13 |

Humanities |

History (art history) |

6 |

12 |

18 |

Other |

Independent scholar |

7 |

1 |

8 |

Social science |

Labor and social research (social welfare, vocational rehabilitation, workplace accommodation consulting) |

5 |

6 |

11 |

Professions and applied science |

Law (attorney, disability law and policy) |

11 |

11 |

22 |

Interdisciplinary |

Library science |

2 |

1 |

3 |

Allied medicine/medicine |

Medicine (Dementia studies, Epidemiology, Nursing, Nutritional sciences) |

9 |

4 |

13 |

Professions and applied science |

Mental health services |

2 |

0 |

2 |

Interdisciplinary |

Museum studies |

4 |

0 |

4 |

Non-profit |

Non-profit organizations |

3 |

10 |

13 |

Allied medicine/medicine |

Occupational therapy and science, Physical Therapy, and Rehabilitation Science |

6 |

9 |

15 |

Humanities |

Philosophy and Ethics |

1 |

5 |

6 |

Interdisciplinary |

Physical education, adapted sport, and kinesiology |

9 |

9 |

18 |

Interdisciplinary |

Planning and Urban Development (Environmental design) |

2 |

1 |

3 |

Social science |

Policy studies and Political Science (health policy, policy analysis, social policy, public affairs, social management) |

8 |

10 |

18 |

Professions and Applied science |

Private sector (various positions, information and technology management, information science and technology) |

4 |

6 |

10 |

Allied medicine/medicine |

Psychiatry |

10 |

3 |

13 |

Social science |

Psychology and Counseling (experimental psychology, human development, cognitive behavioral therapy, developmental disabilities, rehabilitation psychology, school psychology, counseling psychology, counseling education) |

30 |

48 |

78 |

Social science |

Social research and Social sciences |

3 |

9 |

12 |

Social science |

Social work |

15 |

17 |

32 |

Social science |

Special education and Inclusive education |

11 |

27 |

38 |

Other |

Student |

0 |

23 |

23 |

Interdisciplinary |

Urban studies and Metropolitan studies |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Humanities |

Women's, Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies |

4 |

15 |

19 |

Arts |

Writing (creative writing, freelance writer, poet, blogger, magazine founder/editor) |

13 |

32 |

45 |

Other |

Unknown |

10 |

15 |

25 |