Nancy Fraser and Linda Gordon's 1994 article "A Genealogy of Dependency: Tracing a Keyword of the US Welfare State" explored the historical emergence of "dependency" as a moral category of post-industrial American state. In this article, I engage their framework to explore the genealogy of dependency in America's post-industrial sister, the post-Soviet Russian Federation. I also add disability as a core element of 'dependency' that was largely absent from Fraser and Gordon's original analysis. Considering cross-cultural translation, I ask how Russian deployments of three words that all relate to a concept of interdependence align with and depart from American notions of dependency, and trace historical configurations of the Soviet welfare state vis-a-vis disability. To do so, I draw on historical and cultural texts, linguistic comparisons, secondary sources, and ethnographic research. Given this analysis, I argue that rather than a Cold War interpretation of the Soviet Union and the US as oppositional superpowers in the 20th century, a liberatory disability studies framework suggests that in the postindustrial era the Soviet Union and the United States emerged as dual regimes of productivity. I suggest that reframing postsocialism as a global condition helps us to shift considerations of disability justice from a critique of capitalism to a critique of productivity.

Introduction

What is the neoliberal concept of autonomy? How can tracing cross-cultural concepts of autonomy, and its inverse, dependency, help us to unpack the manner in which the category of disability is produced in modernity? What do notions of dependency have to tell us about how the lives of people with disabilities are valued or devalued?

Contemporary Russia has produced a class of "autonomous" self-sufficient women, according to Olga Chepurnaya (2009). The autonomous woman, Chepurnaya writes, "is in control of her own life and consciously makes choices in the public and private spheres" 1 (69). She is influenced by discourses of liberalism and individualism, and is not only independent (nezavisimaia), but her entire orientation to the world and concept of personhood differs from that of her Soviet predecessors. Chepurnaya's example is "Tatyana", a twenty-nine year old Saint Petersburg lawyer, a member of the first generation of women in Russia who are able to earn a living that is sufficient to buy an apartment, a car, clothing and household goods, and support a child — without entanglement with the physical and bureaucratic arms of state socialism. This constitutes a life circumstance of personal liberty buttressed by economic self-sufficiency that fifteen years earlier would have been unthinkable.

Chepurnaya's analysis foregrounds an interpretation of autonomy not as a normative attribute, but as a set of practices or a life strategy. Tatyana's autonomy manifests as a self-perception of status, selfhood and by her relationship to the Russian state. But not all contemporary Russian citizens are so autonomous; one particular moment in Chepurnaya's retelling emphasizes Tatyana's sense of autonomy via her perception of other Russian citizens. Describing a recent seaside vacation, Tatyana recalls her dismay when she realized upon arrival that the resort was far from the Western business-class affair advertised. Tatyana illustrated her disappointment by detailing not only the facilities themselves, but the type of guests. She recalls pulling up to the resort in her car and observing that "the hotel was terrible, just disgusting... and everyone there was needy [ubogie], as if only buses go there. Pensioners, invalids, and then we drove up. They hated us right away. They immediately hated us because they could see that our car is expensive, they could see as we parked by the window" 2 (87). The revulsion, Tatyana insinuates, was mutual. In her eyes, she stands at the opposite end of the social spectrum from the type of guests who frequented the hotel, as though they occupied spheres of citizenship and public life that ought not mix. The unspoken implication of Tatyana's assessment is that where she herself is an independent (nezavisimaia), autonomous (avtonomnaia), and self-reliant woman (samostoiatel'naia), the other hotel guests are dependent (zavisimye), dependent (nishchii), and dependants (izhdiventsy).

By parsing Tatyana's judgment of pensioners and the disabled, we find a disjuncture of linguistic variation. The variegation of words in Russian to describe independence is matched in English. In contrast, their respective antonyms, valences of dependency harboring separate definitions, are separate words in Russian, as opposed to multiple definitions of a single word in English. What might we learn by examining this disjuncture? What implications might such an investigation have for understandings of citizenship, poverty, and social welfare in Russia?

Nancy Fraser and Linda Gordon, in an essay entitled "A Genealogy of 'Dependency'" 3 , outline a critique of the manner in which the English word dependent has evolved over historical conjunctures in the United States to index a variety of economic, social, and moral/psychological assessments. In this paper, I take up Fraser and Gordon's framework for examining historical trajectories of the notion of dependency, and add the lense of disability. In particular, I examine the manner in which autonomy and dependency have developed in a Russian context, finding both departures from and parallels to the genealogy described by Fraser and Gordon in the United States. I argue that on both sides of the Cold War, a Fordist modernity asserted a hegemony of productivity as the arbiter of human worth that was maintained and reinforced throughout the twentieth century (and remains relevant into the political economic forms that we call post-Fordism). By tracing the concept of dependency, I seek to reveal important implications for justice.

Thus, the trajectory of this paper will unfold as such. First, I root us in our commonplace understanding of dependency as an English-language conceptual array. Second, I review the critical insights offered by Fraser and Gordon in "A Genealogy of 'Dependency'" – in particular, that notions of personhood and citizenship as moral values intersect with economic understandings of dependence. I elaborate how a critical disability studies perspective adds to their argument, filling out what Fraser and Gordon in passing refer to as "pauperism" – those who find themselves unable to earn a living wage – or, in the economic terms of the welfare state, the disabled. Third, I attempt to construct a parallel genealogy of dependency by tracing related words through historical usage in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia. As do Fraser and Gordon, I draw on historical dictionaries, legal documents, and cultural texts in order to reconstruct this genealogy; I also add insights from my own ethnographic research on disability in contemporary Russia. Finally, I attempt to synthesize the implications of the divergences of vocabulary and meaning identified thus far for scholarly conversations about post-Soviet citizenship. I propose questions and potential paths forward for a postsocialist perspective that rereads Soviet and American discourses of dependency as mutually complicit in creating ableist, individualizing societies.

What is dependency? parsing a key word

In both Russian and English, the word is an archaic one, most frequently deployed in technical economic language. The Free Online Dictionary, 4 a top hit for English-language Google searches, differentiates between dependent and dependant in terms of meaning.

de•pen•dent

adj.

1. Contingent on another.

2. Subordinate.

3. Relying on or requiring the aid of another for support: dependent children.

4. Hanging down.

n.

also, de•pen•dant, One who relies on another especially for financial support.

In this reading of contemporary English, we differentiate the adjective that describes the condition of dependency from the noun, one who is a dependant could be described as dependent. A dependant is someone categorized by his or her reliance on another for financial support. That is, as a noun dependant is an economic categorization, meaning, one whose economic life is defined by a condition of dependency. The genealogy of the English word dependency and the genealogy of parallel concepts in Russian (zavisimost', nishcheta', and izhdiventsy) do not match, and, when examined in juxtaposition, reveal new critical insights about what the respective national milieus may or may not have in common in ways that challenge the taken for granted. I want to distinguish three meanings emphasized in Chepurnaya's case study of Tatyana. That is (1) as an adjective, 'dependent' as contingent and relying on support to maintain material or metaphysical/social position; (2) as an adjective, 'dependent' meaning subordinate and morally reliant; (3) as a noun, one who is dependent in both of the above senses. I propose that Russian language counterpoints are (1) zavisimii, (2) nishchii, and (3) izhdevenets.

Fraser and Gordon's article traces the trajectory of the notion of dependency and takes care to disentangle the meanings that populate the concept. The analysis begins with the observation that the Oxford English Dictionary from 1588 offers the first social definition of the verb "to depend on" as "to be connected with a relation of subordination," and was "applied widely in a hierarchical social context in which nearly everyone was subordinate to someone else but did not thereby incur individual stigma" (1997: 124). Meanwhile, "independence" was a rare condition of propertied status, à la our current expression, 'a person of independent means'; in contrast, to be dependent "was to gain one's livelihood by working for someone else" (125). In this way, the notion of independence as a political-legal value emerged along with liberalism as a philosophy and attendant concepts of governance. "In the age of democratic revolutions, the developing new concept of citizenship rested on independence; dependency was deemed antithetical to citizenship… When white workingmen demanded civil and electoral rights, they claimed to be independent." (127). As Fraser and Gordon point out, this move added an inherently raced, gendered, and aged component to notions of dependency: white men were now independent, whereas women in the wife role, and racialized persons in the slave role were dependent along with children. Meanwhile, waged labor was no longer considered "dependent" and the white workingman wage-earner was now, in the rational political sense, independent (128). As a result, by the end of the nineteenth century, a bifurcated understanding of dependency emerged: the "healthy" private sphere dependency of wives and children on husbands (who by virtue of their economic/political-legal status are 'independent'), and the "dubious" public sphere of dependency, indicating those citizens who, short of economic subsistence capacity, rely on charity [and, eventually, the state] (132). This perspective was institutionalized in the Census and taxation apparatus which calls wives and children "dependents" (132) and Fraser and Gordon point out, "most Americans today still distinguish between 'welfare' and 'nonwelfare' forms of public provision and see only the former as creating dependency (133)."

The nature of this moral stigma of public dependency in the United States also changes over the course of the twentieth century. As politically won battles on feminist and gay rights fronts along with broader social patterns have changed the expected nature of the family unit, the notion of wife-as-dependent has faded (135), though still catalogued in certain programs, such as the SSDI widow payment. Through civil rights struggles, the definition of the public citizen has broadened to include previously excluded racialized and gendered subjects. As previously privately dependent adults enter the agora as wage earners, by consensus all economic dependence becomes public and therefore, argue Fraser and Gordon, morally suspect 5 (135).

Albeit unintentionally—since they do not touch on the notion of disability – Fraser and Gordon's article has much to say about the emergence of stigma around disability. The custodial role of the welfare state as a caretaker of the worker has an intrinsic developmental link to the move, during industrialization, to support those unable to work (Baynton 1996); the category of disability as we understand it today – a confluence of economic and medical factors mediated by the state – was thus born alongside Fordism 6 . Fraser and Gordon observe that as a result of the imposition of liberal independence on the political self, the economic self is implicated so that "the worker tends to become the universal social subject: everyone is expected to 'work' and to be 'self-supporting'" (135). Simultaneously, the "moral/psychological register" of dependency as a categorical label expands (134), so that those persons who are not 'self-supporting' via wage labor acquire a moral stigma.

In the genealogy that follows, I look at the ways that disability as a category was both invented as a valence of the Soviet welfare state, and simultaneously rendered morally suspect as a category of difference. Given the knowledge that the notion of dependency in Russian does not align with its English language counterpart, we must then begin to question why it is that people with disabilities (while recipients of distributive justice through state welfare systems) were systematically mistreated, excluded from the public sphere, and socially stigmatized in both the US and the USSR. As Sarah Phillips has demonstrated, although the culturally contingent configurations of disability in the Soviet Union differed from American concepts of disability, as in the American twentieth century, disabled citizens of the Soviet Union encountered medical pathologization and social marginalization (Phillips 2009; 2011). Like Fraser and Gordon's observation that dependency worked to individualize and pathologize, we can postulate that people with disabilities were subject to some discourse that individualized and pathologized difference. The common thread of the welfare state in both American and Soviet arenas concerns the development of a rubric for identifying and setting apart those bodies deemed non-productive for labor 7 . This, in turn, gestures to a core insight from disability studies: that the modern episteme relies on a fundamental assumption about ablebodiedness, and that this ableist doxa has been responsible for justifying the ongoing domination of people with bodies and minds that the Fordist state deemed unable to participate at a satisfactorily normative 8 rate in production.

Therefore, a fundamental assumption about what makes humans human and what makes a worthy citizen is bound up in the capacity of a given body to produce surplus, so that an individual's "productivity" becomes equated with his or her moral worth. While others have argued this in relation to the oppression of people with disabilities under capitalism (Russell and Malhotra 2009), by tracing the genealogy of dependency, it becomes clear that what I will call a regime of productivity was also at work in the self-purportedly anti-capitalist Soviet Union. 9The domination of people with disabilities living in a society characterized by ableist doxa is not only a condition of capitalism, but of modernity—specifically, a modernity that glorifies productive labor.

Technologies of governance 10 were developed within both American and Soviet regimes of truth which characterized a lack of productivity not as a systemic problem, but as a reflection of individual pathologies. These technologies resulted in a new system of "disability" by which some bodies were deemed pathologically different based on their failure to adhere to standards of production on a national level. As Deborah Stone demonstrates in her brilliant analysis of the creation of disability as a category of the industrialized welfare state (1984), the systems of diagnosis developed in the early twentieth century were utterly new technologies of governance that came into being along with new epistemic configurations of the state as an entity responsible for a modernist development that relied on production.

In the Soviet Union, in both ideology and practice, the labor power of the individual was harnessed for the collective project. The challenge facing both the US and the Soviet Union throughout the twentieth century was "to create conditions" in which autonomous behavior aligned with state interest. It is in this vein that I invoke the idea of regime, by which I mean not only a "configuration of political state apparatus," but also, a configuration of power that creates and effectively implements on every level a truth effect, the normalizing of particular epistemic assumptions so that they become invisible. That is, I am arguing that in both the United States and the Soviet Union, by and large the equating of productivity with a moral good was so engrained as to go unquestioned in each of these supposedly opposing systems. This is what I mean by regimes of productivity.

A Genealogy of Dependency in Russia

As in the United States, there was no notion of "disability" per se in mid-19th century Russia. The word kaliaka, similar in timbre to the English cripple, is present in the dictionary account of 19th century linguist and lexographer of Russian, V.I. Dal', as is invalid, which referred at that time specifically to veterans, and carried a connotation of glory, as in one who had given himself to the nation (and in fact Dal' offers no feminine form of the noun). 11 The word nishchii (recall, one of our valences of dependency, subordinate and morally reliant), does appear in Dal's dictionary. We find it as an adjective, meaning alms-seeking or beggarly, which can also be used as a noun — beggarly one. It also appears in two definitions related to the subsequent concepts of disability: ubogii, an invalid. An analysis of these definitions indicates that to be beggarly is not negatively morally valued in the 19th century Russian lexicon; on the contrary, a reverence for the "poor in spirit," as a core repetition of the Russian Orthodox Mass, locates the nishchii as "aligned with God" 12.

Significantly, izhdevenets (another of the valences of dependency, one who is both socially and materially reliant with negative moral connotations) was not yet in play in 19th century Russia. Thus, considering the notion of nishchii, disability and poverty were to some extent linked in 19th century Russia, perhaps in a manner similar to Fraser and Gordon's allusion to pauperism. And like the early dependence that they describe, the "beggarly ones" do not carry a negative moral stigma; the liberal equality of the male citizen before the state had yet to emerge from feudal class configurations.

At the turn of the 20th century, neither the notion of disability, nor the notion of dependency as a politico-economic-moral attribute had emerged yet. As the Soviet Union reformulated Tsarist Russia as a workers' state, an ideological rebirth drastically changed the orientation of the Russian citizen to political economy, and the relationship of individuals to work. This resulted in a radical shift in how public and private spheres were organized, and new constellations of meaning around the manifold concepts that we call dependency.

In this transition, non-productive bodies did not fare so well. Marx proposed that, once achieved, a communist society would provide for all worker-citizens; he rooted this utopian vision in the distributive principle that material goods ought to flow "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need." If implemented, such a formulation would have meant a fundamental reordering of bodily capacity vis-à-vis productivity 13 . However, in spite of the elevation of Marxism as a key tenet of the new order, this distributive principle failed to make it into the revolutionary platform. Instead, Lenin's 1917 pamphlet "The State and Revolution" asserted that a realistic proposal for building a transitional socialist state that sought to eventually achieve communism necessarily required incentives to production for workers; thus, he asserted, provision would be based on the precept of "to each according to his contribution." This trajectory of productionism as a compromise of principle in emergent socialism has been discussed by scholars, but rarely in relation to disability justice 14.

The USSR would have no nishchie, or economically dependent. According to the utopian revolutionary and resulting early Soviet policy, poverty and servitude would be eliminated via campaigns of education, electrification, and industrialization to create a society of "New Soviet Persons" (von Geldern 2011a-d). Because the early Soviet ideology held that social conditions created pathology, it was believed that given these newly engineered social forces, the emerging population "would be enlightened, unburdened by psychological complexes, [and] unblinded by distinctions of nationality and gender" (von Geldern 2011d). In this climate, the creation of the category of invalidi created a new kind of dependency with complex moral associations. For example, who was responsible for the failure of a child to thrive, or for a young adult's laziness? Those deemed morally suspect were considered utterly unable to take responsibility for themselves, as the social conditions which had produced their personal "complexes" would have to be remedied by exposure to ideal conditions; moreover, they were dangerous to the broader population as potential vectors for the spread of social ills (Phillips 2009; Ball 1994).

In 1922, regulations on state pensions for invalidi, those unable to work due to impairment, were published (Dixon and Macarov 1992: 186), and over the course of the Soviet era, adjustments to the regulations were made. Particularly notable are the implications of the fact that this set of regulations bestowed pensions only to those workers who became disabled in adulthood (whether due to occupational or other causes). Significantly, this indicates a shift from the usage of the word in 19th century Russia to mean only those injured in battle, as documented by Dal' (1989). Left out from these early welfare codes were citizens disabled since childhood or birth; a provision for these citizens was not added until 1968 (Dixon and Macarov 1992: 197-199). This can partially be attributed to the bias of the pension program toward the worker-citizen as valorized in the regime of productivity; in implication if not intention, children with disabilities who never worked were rendered invisible as citizens vis-à-vis welfare policy for the first fifty years of Soviet history. One might argue that such an oversight can be dismissed, as children were already financially dependent on parents, and not expected to be laborers. Moreover, the ideology of the new citizen promised that given the newly implemented institutions, the social conditions would revitalize those children whose development was somehow at odds with expectations. A plan to implement special education was drafted, and later implemented (Phillips 2009). However, the practical segregation in educational policy for children with disabilities indicates that in fact, especially as the century wore on, most of these children were simply institutionalized (McCagg and Siegelbaum 1989; Phillips 2009), in part due to the stigma of social failure that the constructivist ideology passed on to mothers whose children appeared abnormal 15.

In addition to the welfare apparatus, as the twentieth century unfolded, the discourse of rehabilitation took hold: a new, medicalized manner of governance that further subsumed disability and bodily difference into regimes of productivity. Emergent forms of governance at the end of the imperial era sought to address poverty (especially, in the terms of the time, vagrants, beggars, and cripples) for the good of society by formalizing charity as philanthropy and state welfare - an effort that in was both modelled on and aligned with practices in the West (Lindemyer 1996). In contrast, Soviet scientists (most notably, Lev Vygotsky) proposed new theories of individual development, which promised to deliver scientifically-developed, cutting edge technologies of self, capable of rehabilitating to social norms those deemed pathologically different (Phillips 2009). These theories were disseminated through new Soviet educational and medical institutions, and became part of general discourse. In fact, this mode of rehabilitative thinking extended beyond the disabled - a USSR-wide effort to build a "New Soviet Man" through carefully engineered social conditions applied to all citizens in the interwar period (von Geldern 2011). Still, the disciplining and isolation of people with disabilities was profound (Phillips 2009, 2011).

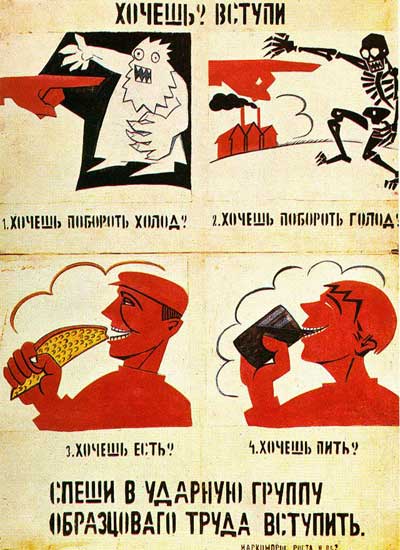

The prejudice of the Soviet state to privilege the perspective and needs of the able-bodied male worker can be read in institutional policies that emerged from the revolution through the 1930s, including welfare doctrine, the implementation of a strategy of productionism, and the valorization of "shock workers" (udarniki) or Stakhanovites, a special class of exceptionally productive laborers, including the creation of the Stakhanovite union (for more on shock workers, see Siegelbaum 2011a, b).

A Soviet poster (1925) with words by Vladimir Mayakovsky and images by Aleksandr Rodchenko, urging citizens who want to beat cold and hunger and have enough to eat to "hurry and join the shock brigade!"

Historian Stephen Kotkin has observed that where Western writing on the welfare state tends to leave out the Soviet Union, considering it a socialist project fundamentally different from liberal democracy. In fact, Kotkin argues, the goals and attributes of the state supports invented and put in place in the interwar era were remarkably similar in powerful nation states of the time, regardless of political system. Not only was the system of pensions intended to build regime loyalty, but, "spending on welfare was understood as advancing the cause of production. Quantitative output was the ultimate 'social' good, a responsibility (and priority) of the entire society" (2001: 149-150). Furthermore, he argues, the very models of production that are characterized as American Fordism were adapted by German, and, in turn, Soviet engineers; in this sense the central tenets of the interwar cult of productivity were intertwined across what are usually considered boundaries of political economy and regime politics. So productive capacity was equated with moral worth for all Soviet citizens, in a manner profoundly intertwined with similar regimes in the west. In this, a certain synchrony of Fordist productivity produced one valence of dependency that aligns with the American genealogy presented by Fraser and Gordon.

However, there were differences: it was not only the nishchie that received support in the Soviet system. As anthropologist Melissa Caldwell observes, "the concept of social welfare as it was envisioned during the Soviet period expanded the realm of needs and services so that they were applicable to all members of society, not just the disadvantaged minority" (2004, 9). Throughout the Soviet period, the practice of a centrally planned economy structured all aspects of consumer life as "subsidized" — prices for housing, dining, food goods, and utilities were set and maintained (Caldwell 2004: 9; Dixon and Macarov 1992: 190) — even as consumerism and consumer practices were facilitated and encouraged (Kotkin 2001: 141-142).

The landscape of synchronized American and Soviet Fordism also diverged in the 1960s, as corporate culture began to replace industry in the West. Meanwhile, in the Soviet bloc, the commitment to heavy industry proliferated (Kotkin 2001). Katherine Verdery (1996) has observed that in the 1970s, Socialist emphasis remained fixated on the acquisition of the material apparatuses of the means of production. Surplus was channeled into the construction and purchase of more tractors, cranes, and industrial farms and factories. As a result, while the West moved into an era of post-Fordism that mobilized populations across national territories and shifted emphasis from manual to what Michel Hardt calls affective or immaterial labor 16 (Mitchell and Snyder 2010: 181, Hardt 2003), the soviet world continued to build toward a Fordist future.

In many ways the transition to post-Fordism in the west has helped to facilitate the emergence of movements for recognition and equality for women and people with non-productive bodies (Hardt 2003). The work space of the office is more like the home space than the factory floor. The family farm has given way to agribusiness. Women and people with (certain) disabilities increasingly entered schools and the workforce. In the United States, the civil rights movement for disability justice, although often overlooked in general narratives of civil rights that center race and gender, unfolded along with women's liberation and struggles to overcome racial prejudice, from the 1950s (when polio survivors began to demand accessibility in public space using civic channels), 60s and 70s (marked by the independent living movement in California and the nationwide implementation of special education in public schools) (Pelka 2012; Longmore and Umanski 2001). Each of these US civil rights movements mobilized languages of autonomy (independence) and freedom in popular discourse (Pelka 2012; Fraser and Gordon1997). Meanwhile, there was no equivalent to the deployment of the notion of "autonomy" that Fraser and Gordon described unfolding in the Soviet Union.

So what does dependency look like in the wake of Soviet policies? As we have seen, nishchie (the needy)faded into the social welfare complex, recast as categories of pension-recipients, most prominently invalidi (and including others such as widowed mothers). As these pension positions were deemed justified and deserved, many welfare recipients can be thought of as simply zavisimii, as in relying on support. But what of our third category of dependency, izhdeventsi, those who are both morally and materially reliant? Recall that Fraser and Gordon argue that the collapsing of moral and material concepts of dependency in the United Staes led to and allowed for the (neoliberal) demonization of welfare recipients (1997).

Perhaps a telling anecdote here is the question of whether or not a retired person may be considered an izhdivenets (a morally and materially reliant person). When I first read Chepurnaya's essay about the autonomous post-Soviet woman, I was curious whether I might deploy the word izdivenets to describe the crowd that Tatyana encountered at the resort (Tatyana herself in the transcribed interview presented by Chepurnaya (2009) refers to both retired people and invalidi using the kinder adjective ubogii). Eleonora, my soviet-born language instructor, responded with surprise that I would think to apply this phrase as a descriptor of elderly pensioners.

"How," she asked, "can such people be considered dependents when they have already worked for so many years and contributed to the country? An izhdivenets is someone who takes, but does not work," she explained patiently. "And this is simply not the case for the retired!!"

I responded that in English we have a meaning of dependent that is simply economic in tax code, for instance, the question found on the commonplace W2 form, how many dependents live in your household? "Isn't," I asked, "a retired adult parent living in one's household and not working a 'dependent' in such a sense?"

She not only disagreed with this usage of izhdevenets, she actually found herself rather flustered, sputtering with indignation. "Do you mean to tell me," she said, "that if I work until I am sixty-five, and then I retire, and I live on a state pension that I have earned as a state employee, in such a case I would be dependent?"

"Yes," I said, "in that case, you would be dependent on the state."

"But," she declared, "I would not be izhdivenets!"

Thus, the moral category adheres to the notion of izhdivenets, while there exists an entirely separate sphere of deserved and earned allocation from the state. An izhdivenets may also be a common slacker, someone who becomes a dependent burden on a household — the son who grows up, but never finds a job, sitting at home in his mother's house eating her food and playing computer games into his 30s. Or, the distant relative who shows up one day for a brief visit, and permanently takes over the couch, as well as access to the liquor cabinet. In this contemporary sense, then, izhdivenets might be more accurately translated as "burdensome one," or, colloquially, a leach. The izhdivenets bucks the regime of productivity, and is socially pathologized by fellow citizens inscribing the truth effect that equates certain kinds of work as synonymous with personal and social worth.

At the same time, in the post-Soviet context a new legal deployment of the term dependant has emerged that is more in line with English language tax code usage. As such, it is now not uncommon to find written in legal documents, "she has three children dependent on her" 17 (KODEKS), presumably a translation of English-language legal discourse that has been appropriated into Russian.

The changes in the Russian notion of dependence, from a scarcely existing concept at the beginning of the twentieth century, to an institutionally codified social lack to be provisioned by the state, has been interpreted in several ways by Westerners encountering the post-Soviet state. The primary Western vision of the post-Soviet since the 1990s has been the so-called transition discourse, which casts a lens of unilinear, unidirectional progress or development flowing from West to East, encouraging Russia to progress from from socialism to capitalism and liberal democracy (Lemon 2008). The emergence of autonomous Russian individuals has in this discourse been held up as the model of progress; however, this is autonomy in the narrow sense, and not in the sense of practices and life strategies intended by Chepurnaya. As we have seen, the dimensions of dependency in Russian language do not cleanly align into a single linguistic marker as in English. Rather, there is a differentiation between zavisimii, which comprises the inverse of autonomy, nishchii, the inverse of self-reliant, and izdivenets, the inverse of a financially independent person. Moreover, the notion of izdivenets is not simply a financially dependent person, it is, more specifically, a person who has failed to contribute satisfactorily to the national (or, on a smaller scale, household) project through labor. Only the last of these contains a moral judgment.

For instance, Melissa Caldwell describes a version of this moral differentiation in her ethnography of Soviet pensioners who rely on a soup kitchen to subsidize their diets—they interpret their acceptance of charity not as a moral failing, but as an earned right. 18

I offer a further ethnographic observation that simultaneously helps us to parse the valences of contemporary Russian dependency and complicate the binary of autonomy/dependency, drawn from my ethnographic research on disability activism in contemporary Russia. In the summer of 2010, a busy civil rights lawyer in St. Petersburg sat down to talk with me about the various kinds of work he does relating to disability and civil rights. He described the popular Russian approach to disability as "highly paternalistic." If someone is an invalid, she or he is simply "like a child" he told me; in our rubric, he is nishchie, not self-reliant; which, in turn results in fellow citizens failing to grant him nezavisimost' or independence in the public sphere. As a civil rights lawyer, he finds that he is often critical of many grassroots disability activists, who present justice claims not as civil rights, but as "social issues"—code in Russia for a problem that ought to be remedied by pensions and social benefits. Rather than reversing the discourse of personal dependency in favor of capacity and rights, he pointed out, such claims perpetuate a culture of relying on a paternalistic state. He prefers the strategy of arguing for civil rights and equal representation before the law, as a manner of avoiding institutional discrimination.

In the lawyer's story I read two types of dependency to which he responds differently. First, the personal dependency of an individual who inhabits a non-normative body (especially one that requires care/contributes limited or is perceived to contribute limited labor), has historically been stigmatized, but, he contends, a civil rights approach to justice can bit by bit counter stigma through legal recognition. The second dependency that he describes is a public dependency of an individual or family on the welfare state. The lawyer frowned on a disability justice strategy that relies on redistibution without civil rights - which in his experience, many parents of disabled children in Russia pursue (petitioning governments to provide social rights like stipends, benefits, and medical care to their children that are often overlooked if not actively claimed) - because it undermines autonomy the person making the claim by casting him as a dependent in need of provisioning. This position emphasizes his Western legal training, and indicate that he has on some level acclimated to the intellectual distinction that Westerners make between the moral ground of redistribution versus recognition (Fraser 1997). He remained optimistic that a civil rights strategy could advance the status of stigmatized minority groups in Russia 19.

This configuration is entwined with broader notions of "rule of law" and democratization of the post-Soviet sphere. There seems to exist a framework for perceiving rights-based claims to justice and redistribution claims as mutually exclusive, though, of course, in practice this is not the case. Indeed, the Russian word pravo, meaning rights of citizenship, includes both civil rights and legally guaranteed social benefits. If a citizen is "dependent" on a state pension and seeks justice through financial redistribution, does this mean that she cannot not act as an independent (nezavisimaia) citizen to voice claims for justice based on claims for recognition as a member of a particular class or group? The lawyer's frustration with those who seek social benefits seems to indicate that he does believe that autonomy and economic dependence are at odds; or, at least, that his fellow citizens' energy would be better spent on civil rights issues. But, for many disability activists, redistribution is the very thing which allow them to enact "autonomy-as-life-strategy" and in turn, for those so inclined, to engage in lobbying for civil rights (Hartblay 2012).

Conclusion

In the opening to Justice Interruptus, the volume in which the genealogy essay appears, Fraser observes that since 1989, "many actors appear to be moving away from a socialist political imaginary, in which the central problem of justice is redistribution, to a 'postsocialist' political imaginary, in which the central problem of justice is recognition" (2). This is the position that our civil rights lawyer takes, one that catalogues civil rights as a more cogent form of justice-seeking behavior than welfare state redistribution. This involves the conflation of two senses of dependency: a political autonomy forfeited when civil rights and self-governance are forfeited, and an economic autonomy, forfeited when one accepts welfare or fails to be a self-sufficient wage earner.

Fraser poses a similar question in another essay in the same volume, "From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a 'Postsocialist' Age," concluding that as justice-seeking practices, claims for civil rights and claims for distributive justice need not be mutually exclusive. Zsuzsa Gille (2010) instead argues that the postsocialist transition in Eastern Europe "is not [a shift] from a politics of distribution to a politics of recognition, but rather to new patterns of and new agency behind fusing the two" (18).

Seeking justice via fused strategies of redistribution and recognition applies to the question of disability as well as to the postsoviet arena. Critical disability theorist Tom Shakespeare has observed that civil rights discourses place too much stock in markets as arbiters of justice: "the focus on civil rights still implies a liberal solution to the disability problem… [neoliberalism, meanwhile, seems] to suggest that the market will provide, if only disabled people are enabled to exercise choices free of unfair discrimination. But market approaches often restrict, rather than increase, choice to disabled people," (2006: 66-67) and, I would add, the choices available to their families and caretakers.

Meanwhile, Chepurnaya's insight, that autonomy as a practice or strategy is invoked variably, coalesces with Sarah Phillip's observations about the citizenship practices and justice-seeking strategies of adults with spinal injuries in the contemporary Ukraine (2011). Phillips proposes that her informants alternately deploy narratives of liberalism and democracy, or dependency and need, in order to make claims on governmental resources. Drawing on Aihwa Ong (2007), Phillips plays with the term "mobile citizenship" - these "hybrid strategies" literally beget mobility and access for her informants, and, the notion of citizenship itself is mobile, in that it moves through negotiable and variable meanings. Phillips and Chepurnaya, taken together, show how women and people with disabilities selectively engage with notions of political autonomy. In this way, so-called "dependence" and so-called "autonomy" are both enacted selectively "as life strategy".

These patterns of fusing recognition and redistribution to access new kinds of agency, as Gille describes, are aided by the different lexicons of dependency in Russian and English. As we have seen, the linguistic constellation that in English links dependence in the economic sense and independence in the political sense has no counterpart in Russian. Conceptually, poverty is not necessarily linked to lack of self-sufficiency: nishchie may be avtonomnie. While in English such a claim involves encountering and dismantling the linguistic hurdle of claiming that the financially dependent may in fact be politically independent, in Russian, this disambiguation is simply taken for granted 20.

This paper has explored a genealogy of dependency and the cultural disjunctures between English and Russian located in this keyword as instrumental to concepts of welfare policy, moral citizenship, and techniques of governance. To the initial concept of a genealogy of dependency laid out by Fraser and Gordon, this argument adds an attention to ableism and disability, and a critical attention to the ways that ideas circulate and get taken up across global and cultural territories of difference. At the core of all of these pursuits is a concern with justice in an era of global postsocialism. As a whole, this paper stands as an argument for a global postsocialist perspective that insists on moving beyond both the neoliberal transition narratives (predicated on an "end of history" marked by an inevitable implementation global capitalism and democracy) and leftist anti-capitalist conversations that fail to recognize the limitations of locating systems of capital as the absolute root of injustice (here, explicitly, the tendency of these perspectives to ignore ableism and thus reinforce regimes of productivity and the capacity therein to pathologize those who do exist outside of systems of capital 21).

Fraser's invocation of the concept of "postsocialist" is, at its core, concerned with a realignment of global justice-seeking strategies in that, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequent hegemony of market capital as irrevocable from democracy, no longer consider a departure from capitalism as a viable option. In a footnote, Fraser and Gordon go on to say that scholars have implied that arguments about redistribution and recognition represent "a loss of systemic critique, a sense of independence gained by narrowing the focus to the individual worker and leaving behind aspirations for collective independence from capital" (1997: 146). How can a global postsocialist imaginary escape this trap?

Given the evidence laid out above, I argue that attention to the ways that technologies of governance have at their core an obsession with productivity, driven by a doxa of ableism, may offer some novel ways to return to systemic critiques that work to expand our understanding of collective domination beyond the discourse of critiques of capital.

As this genealogy has begun to document, the Soviet and American twentieth centuries unfolded as entwined, dual fields for implementing and testing a welfare state (both in spite of and because of Cold War discourses that cast them as binary opposites). Taking this similarity as a point of departure for comparison — and the development of a global postsocialist imaginary — proves fruitful. Stephen Kotkin writes that, "No less than the United States, though in different ways, the Soviet Union embraced mass production, mass culture, and even mass consumption" (2001: 112). Both regimes, in their own way were "caught up in the new 'age of the mass' made irreversible by total mobilization, and in exploring the integrating mechanisms provided by varying forms of mass production, mass politics, mass consumption, mass culture, social welfare, and imperial/national projects" (2001: 113-114). The conditions of Fordism, characterized by a cult of productivity, attempted to reconcile wage-earning and moral obligation as manners of distributive justice. Thus, it becomes relevant to engage with both the Soviet Union and the United States as differing but cooperating co-authors of a twentieth century defined by regimes of productivity.

This reordering of the Soviet Union and the United States as parallel regimes of productivity speaks to Fraser's call for a new postsocialist imaginary that no longer considers a departure from capitalism as the key to throwing off domination. To post-Soviet studies such an orientation brings an escape from Cold War discourses and their offspring, transition discourses (Caldwell 2004; Lemon 2008), that posit the Soviet and the American as binary opposites (Yurchak 2006). Instead, it seeks a North American perspective on Russia that refuses to provincialize, but instead encounters Russia as a parallel conjuncture that is equally engaged in attempting to escape the problem of equitable distribution in a regime of productivity.

The notion of global postsocialism helps us to advance disability theory. In this essay, we have not only brought the (post-)Soviet into conversations as an additional perspective in the "new disability history," we have made an further critical move. That is, we are reframing postsocialism as a global condition helps us to shift considerations of disability justice from a critique of capitalism to a critique of productivity. In line with Mitchell and Snyder's (2010) concept of "non-productive bodies" as troubling left politics that are based in labor justice, this implies a critical disability theory that seeks new liberatory practices that are suspicious of models like Lenin's transitional socialism that compromises equitable distribution ("to each according to his need") in favor of productivity ("to each according to his contribution"). Additionally, by challenging the logics of liberalism, this argument dovetails with a relational model or capabilities approach to disability 22, that is, toward redefinitions of what constitutes humanness and human worth.

Thus, we are faced with a challenging, as-yet unanswered, and potentially door-opening question: how can a global postsocialist imaginary escape the trappings of a concept of justice that rely on logics of productivity to determine the deservedness of various citizens?

References

- A. P. Yevgen'yeva, ed. 1957. Slovar' russkogo iazyka. 4 vols. Moscow: State Publisher of Foreign and National Dictionaries, Institute of Language, Academy of Sciences, USSR. In Russian.

- Ball, Alan. 1994. And now my soul is hardened: abandoned children in Soviet Russia, 1918-1930. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Baynton, Douglas. 1996. Forbidden signs: American culture and the campaign against sign language. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bérubé, Michael. 1998. Life as we know it: a father, a family, and an exceptional child. 1st ed. New York: Vintage Books.

- ———. 2010. Equality, Freedom, and/or Justice for All: A Response to Martha Nussbaum. In Cognitive disability and its challenge to moral philosophy, ed. Eva Kittay and Licia Carlson. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Caldwell, Melissa L. 2004. Not by Bread Alone: Social Support in the New Russia.

- Chepurnaya, Olga. 2009. Avtonomnaia Zhenshchina: zhiznennaia strategiia i ee emotsional'nye izderzhki. In Novyi byt v sovremennoi Rossii: gendernye issledovaniia povsednevnosti: kollektivnaia monografiia, 524. Saint Petersburg: Izdatel'stvo Evropeiskogo Universiteta v Sankt-Peterburge. In Russian.

- Dal', Vladimir. 1989 (1863-1866). Tolkovyi slovar' zhivogo velikorusskogo Iazyka. 2nd ed. 4 vols. Moscow. In Russian.

- Davis, Lennard J. 1999. "Crips Strike Back: The Rise of Disability Studies." American Literary History 11 (3) (October 1): 500-512.

- ———. 2006. Constructing Normalcy: The Bell Curve, the Novel, and the Invention of the Disabled Body in the Nineteenth Century. In The disability studies reader, ed. Lennard J. Davis. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Dean, Mitchell. 1995. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. London: Sage.

- Dixon, John, and David Macarov, eds. 1992. Social welfare in socialist countries. New York: Routledge.

- Draper, Hal. 1970 (1966). The Two Souls of Socialism. http://scholar.googleusercontent.com/scholar?q=cache:ycbGORNKFhMJ:scholar.google.com/+productionism+socialism+russia&hl=en&as_sdt=0,34.

- Esteva, Gustavo. 2005. "Celebration of Zapatismo." Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 29 (1): 127-167.

- Foucault, Michel. 1984. The Foucault Reader. Ed. Paul Rabinow. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Fraser, Nancy. 1997. Justice interruptus: critical reflections on the "postsocialist" condition. New York: Routledge.

- Fraser, Nancy, and Linda Gordon. 1994. A Genealogy of Dependency: Tracing a Keyword of the U.S. Welfare State. Signs 19, no. 2 (January 1): 309-336.

- ———. 1997. A Genealogy of Dependency: Tracing a Keyword of the U.S. Welfare State. In Justice interruptus: critical reflections on the "postsocialist" condition. New York: Routledge.

- Gal, Susan. 2002. A Semiotics of the Public/Private Distinction. difference: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 13, no. 1: 77-95.

- ———. 2005. Language Ideologies Compared: Metaphors of Public/Private. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15, no. 1: 23-37.

- Gibson-Graham, J.K. 2006. The end of capitalism (as we knew it): a feminist critique of political economy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gille, Zsuzsa. 2010. "Is there a Global Postsocialist Condition?" Global Society 24 (1): 9-30.

- Hardt, Michael. "Affective Labor." 2003. February 2, 2014. http://www.makeworlds.org/node/60

- Hartblay, Cassandra. 2006. "An Absolutely Different Life: Locating Disability, Motherhood, and Local Power in Rural Siberia". Honors Thesis, Saint Paul, MN: Macalester College. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/anth_honors/1/.

- ———. 2012. "Accessing Possibility: Disability, Parent-Activists, and Citizenship in Contemporary Russia". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Kafer, Alison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

- KODEKS - Russian Law Database. Search for "иждивен". Friday, February 4, 2011. http://kodeks.mosinfo.ru/.

- Kotkin, Stephen. 2001. Modern Times: The Soviet Union and the Interwar Conjuncture. Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 2, no. 1: 111-164.

- Lemon, Alaina. 2008. Hermeneutic Algebra: Solving for Love, Time/Space, and Value in Putin-Era Personal Ads. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 18, no. 2: 236-267.

- Lenin, V. I. 1999 (1917). The State and Revolution: The Marxist Theory of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution. Marxist Internet Archive. Accessed Jan. 2014. http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch05.htm#s3.

- ———. 2004 (1917). Gosudarstvo i revoljutsija. Marxist Internet Archive. Accessed Jan. 2014. http://www.marxists.org/russkij/lenin/works/lenin007.htm. In Russian.

- Levinson, Jack. 2010. Making Life Work: Freedom and Disability in a Community Group Home. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lindemeyr, Adele. 1996. Poverty is not a vice: charity, society, and the state in imperial Russia. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Linton, Simi. 1998. Claiming disability:knowledge and identity. New York: New York University Press.

- Longmore, Paul, and Lauri Umanski, eds. 2001. The new disability history: American perspectives. New York: New York University Press.

- Madison, Bernice Q. 1968. Social Welfare in the Soviet Union. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Malhotra, Ravi. 2001. "The Politics Of The Disability Rights Movement." ZNet (July). http://www.zcommunications.org/the-politics-of-the-disability-rights-movement-by-ravi-malhotra.

- Marx, Karl. 2010. Capital: Volume One. Economic Manuscripts. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/.

- Mitchell, David T. and Sharon L. Snyder. 2010. Disability as Multitude: Re-working Non-Productive Labor Power. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 4, no. 2: 179-193.

- McCagg, William and Lewis H. Siegelbaum. 1989. The Disabled in the Soviet Union past and present, theory and practice.

- Ong, Aihwa. 2007. Neoliberalism as a mobile technology. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 32, no. 1 (January): 3-8.

- Petryna, Adriana. 2002. Life exposed: biological citizens after Chernobyl. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Phillips, Sarah. 2009. "'There Are No Invalids in the USSR!' A Missing Soviet Chapter in the New Disability History." Disability Studies Quarterly 29 (3). http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/936/1111.

- ———. 2011. Disability and mobile citizenship in postsocialist Ukraine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Read, Christopher. 2006. "Krupskaya, Proletkul't And The Origins Of Soviet Cultural Policy." International Journal of Cultural Policy 12 (3): 245–55.

- ———. 2001. The Making and Breaking of the Soviet System: An Interpretation. European History in Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Russell, Marta, and Ravi Malhotra. 2009. "Capitalism and Disability." Socialist Register 38.

- Shakespeare, Tom. 2006. Disability rights and wrongs. New York: Routledge.

- ———. 2009. Disability: A complex interaction. In Knowledge, Values and Educational Policy: A critical perspective, ed. Harry Daniels. Routledge.

- Siegelbaum, Lewis. 2011a. Shock Workers. Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. http://www.soviethistory.org/index.php?page=subject&SubjectID=1929udarnik&Year=1929&navi=byYear.

- ———. 2011b Year of the Stakhanovite. Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. http://www.soviethistory.org/index.php?page=subject&SubjectID=1936stakhanov&Year=1936.

- Spektorowski, Alberto. 2004. "The Eugenic Temptation in Socialism: Sweden, Germany, and the Soviet Union." Comparative Studies in Society and History 46 (1): 84-106.

- Stiker, Henri-Jacques. 1999. A history of disability. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Stone, Deborah. 1984. The Disabled State. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- von Geldern, James. 2011a. The New Woman. Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. http://www.soviethistory.org/index.php?page=subject&SubjectID=1917woman&Year=1917.

- ———. 2011b. Raising Socialist Youth. Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. http://www.soviethistory.org/index.php?page=subject&SubjectID=1917youth&Year=1917&navi=byYear.

- ———. 2011c. Electrification Campaign. Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. http://www.soviethistory.org/index.php?page=subject&SubjectID=1921electric&Year=1921.

- ———. 2011d. New Way of Life. Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. http://www.soviethistory.org/index.php?page=subject&SubjectID=1929byt&Year=1929.

- Verdery, Katherine. 1996. What was socialism, and what comes next? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Wierzbicka, Anna. 1997. Understanding Cultures Through Their Key Words: English, Russian, Polish, German, and Japanese. Cary, NC, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Yurchak, Alexei. 2006. Everything was forever, until it was no more: The last Soviet generation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Endnotes

- "sama kontroliruet svoiu zhizn' i soznatel'no delaet vybory v publichnoi i privatnoi sfere (69)." all translations my own, unless otherwise noted.

Return to Text - "Otel' uzhasnyi, prosto otvratitel'nyi … A tam vse ubogie, tuda voobshche tol'ko avtobusy khodiat. Pensionery, invalidy, i my tut … priekhali. Nas uzhe zaranee nenavideli. Zaranee nenavideli, potomu chto vidiat, chto mashina dorogaia, oni zhe vidiat, my ee postavili pod oknami"(87).

Return to Text - The article first appeared as a featured piece in the journal Signs in 1994. It was subsequently included in Fraser's 1997 collection of essays, Justus Interruptus: critical reflections on the postsocialist condition. Page number citations in this article refer to the 1997 text.

Return to Text - Here, I have intentionally referenced a non-scholarly dictionary, as a manner of demonstrating that the range in meaning offered in the term dependent is a colloquial, as well as scholarly one. This move is only possible following Fraser and Gordon's careful discussion of the OED definition, with which this non-scholarly source is not inconsistent, and on which the premise and arguement of this article, as well as my own expanded discussion of the semantic domains of dependency, rest.

Return to Text - Although recent political discourse may point to a manner in which private sphere dependency is still deemed the morally appropriate roll for women by some conservatives.

Return to Text - This claim, that the category of disability emerged along with Fordism, requires a move from a commonsense understanding of disability to a social model, or even, a political-economic model. That is, it involves rejecting "definitions of disability which make it appear that impaired persons are 'naturally' and, therefore, justifiably, excluded from the 'labor force'… [and instead] reconceptualizing disability as an outcome of the political economy" (Russell and Malhotra 2009). As Deborah Stone (1984) has shown, the contemporary concept of disability was invented as a category of the modern welfare state in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Return to Text - In 2010, disability studies scholars David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder proposed the term "non-productive bodies," as a strategic move to open the ideas of disability studies to broader social theory (in particular the neo-Marxist left). They write, "whereas traditional theories of political economy tend to stop at the borders of the laboring subjects (including potential laborers), the concept of non-productive bodies expansively rearranges the potentially revolutionary subject of leftist theory" (186). This underlines the insight that certain "resistant subjects… whose capacities make them 'unfit' for labor as the baseline of human value" offer a potential opening to destabilize the logic of capital (184).

Return to Text - For a discussion of the birth of statistics as pivotal in inventing the category of "normal" and the attendant technologies of governance vis-à-vis disability, see Davis (2006 and 1999:504).

Return to Text - The notion that the Soviet Union was also a regime of productivity offers two suppositions: that this outcome was (1) a failure to realize the ideal of communism, or (2) an inescapable outcome consistent with communist ideology. I argue for the former interpretation.

Return to Text - As French historical anthropologist Henri Stiker (1999) has indicated, historical genealogy must keep in mind the Foucaultian insight about technologies of governance; it is not so much to say that new types of people (e.g. "the mad" or "the disabled") came into being, so much as to observe the new technologies and systems that were devised for governing, monitoring, and disciplining populations. That is to say, attending to disability through the lens of social welfare here is intended as a means of accessing implications and kinds of citizenship, what it means to lead a good life, and what has been linguistically, institutionally, socially, ontologically, morally differentiated from the good life.

Jack Levinson, in his monograph on governance in the contemporary American group home for adults with intellectual disabilities succinctly summarizes the ways in which Foucault's concepts are relevant to the category of disability. He writes, "The aim of governing is not to achieve total regulation but to structure the possibilities for action; to create conditions in which individuals may conduct themselves freely in particular ways. Human conduct, in this sense, is thought of "as a resource" that must be both "unlocked" and "harnessed" (Dean 1996, 60-61)" (Levinson 2010:39; Foucault 1984).

Return to Text - A version of this analysis of philological roots of concepts of disability in Dal's dictionary first appeared in my undergraduate thesis (Hartblay 2006), and has subsequently been cited by Sarah Phillips (2009, 2010). The material presented herein draws on that earlier work, but has been adapted to the subject at hand. Please refer to those works for an expanded discussion of concepts emergent in Dal's dictionary.

Return to Text - I thank my mentor Alla Orlova for this insight.

Return to Text - Although in reviewing the potential of the Soviet Union to create a state free of ableist regimes of productivity we find Marx's concept "to each according to his need" promising, we must not mistake Marxist doctrine for a politics of liberation for the non-productive body. As Mitchell and Snyder have observed (2010), the Marxian focus on labor justice and class as the primary dimension of social injustice obscures the systematic oppression and disenfranchisement of people with disabilities that emerged as part of the very industrial revolution which Marx decries. Moreover, Marx's own interpretation of human history interpellates labor-power as a primary valence of personhood. In "Capital Volume One," Marx describes (as core to humanness) the capacity of man to manipulate earthen material with tools in order to fulfill needs. Men are called free when the products of their own labor return to them, and they need not sell their labor for survival (see Part 8: Primitive Accumulation).We might interpret this to mean, given the centrality of human labor power in the text, that productive labor and the potential for provisioning oneself is at the core of Marxist doctrine (I thank Stevie Peace for this insight). On the other hand, Marx faults the greed of some primitive "Adam" who failed to share a surplus with his weaker brothers, and traces the ways that domination emerged in part from Weberian understandings of protestant doctrine that valued productivity and accumulation of wealth (Marx 2010: Chapter 27, Footnote 9).

Return to Text - Productionism, describing the scramble of emergent socialist states to emphasize productivity in order to combat, compete with, and ultimately overcome their exploitative capitalist competitors, is characterized by scholars as an ideological compromise undertaken by Communist revolutionaries, particularly Lenin (Read 2006: 249; Read 2001: 37). In some arguments, the emphasis placed on competitive production in the early decades of the Soviet Union is seen as a necessary evil, while some radical scholars have villanized this move as an exploitative tactic on par with state capitalism.

The "of course" in the Draper's second sentence is telling: "everyone is 'for' production just as everyone is for Virtue and the Good Life," demonstrating the pervasive capacity of abelist regimes of productivity to occupy the doxa of socialist imaginaries as well as the political economy of existing capitalism.Describing the "Six Strains of Socialism" Hal Draper wrote,

There is a subdivision under Plannism which deserves a name too: let us call it Productionism. Of course, everyone is "for" production just as everyone is for Virtue and the Good Life; but for this type, production is the decisive test and end of a society. Russian bureaucratic collectivism is "progressive" because of the statistics of pig-iron production (the same type usually ignores the impressive statistics of increased production under Nazi or Japanese capitalism). It is all right to smash or prevent free trade unions under Nasser, Castro, Sukarno or Nkrumah because something known as "economic development" is paramount over human rights. This hardboiled viewpoint was, of course, not invented by these "radicals," but by the callous exploiters of labour in the capitalist Industrial Revolution; and the socialist movement came into existence fighting tooth-and-nail against these theoreticians of "progressive" exploitation. On this score too, apologists for modern "leftist" authoritarian regimes tend to consider this hoary doctrine as the newest revelation of sociology. (Draper 1970:18)

Pertinent to this topic is the tendency toward eugenicist policy in socialist productionism. For further discussion, see Spectorowski (2004).

Return to Text - However, scholarship indicates that social welfare provided for all Soviet children was subpar. See, for example, Ball (1994). I thank Aaron Hale-Dorrell for this point.

Return to Text - Hardt writes, "It has now become common to view the succession of economic paradigms in the dominant capitalist countries since the Middle Ages in three distinct moments, each defined by a privileged sector of the economy: a first paradigm in which agriculture and the extraction of raw materials dominated the economy, a second in which industry and the manufacture of durable goods occupied the privileged position, and the current paradigm in which providing services and manipulating information are at the heart of economic production" (2003). This third paradigm was, according to Verdery's ethnographic analysis, less or differently present in postwar twentieth century communism, which instead continued to privileged industry (1996).

Return to Text - "deti, nakhodiashchikhsia na nee izhdivenii"

Return to Text - As I hope is clear from the approach of this paper, I contend that we must be careful, as scholars, not to attribute contemporary russian attitudes toward state welfare to some imagined, immutable "Soviet mentality" but rather attend to more subtle differences and similarities between Soviet and American conjectures.

Return to Text - During our interview in 2010 the lawyer was optimistic about gains made in his practice toward protecting the rights of LGBT populations, mentally disabled populations (who were frequently facing revocation of legal independence without fair trial), and thus extended to physically disabled and racial minorities. However, as of the publication of this article, in 2014, the situation in Saint Petersburg, espcially toward LGBTQ populations has changed drastically, following the city-wide and then nation-wide ban on LGBTQ propaganda. I was unable to follow up with him to see if his perspective has changed in time for this publication, but hope to do so in the future.

Return to Text - However, invalidi are excluded from moral personhood via the truth effect of regimes of productivity; it is here that the lawyer's commitment to developing a new politics of civil rights becomes vital.

Return to Text - The concept of people with disabilities existing "outside of systems of capital" was proposed by Mitchell and Snyder (2010); discussions of whole communities that engage in diverse economic practices that may create spaces of autonomy outside of capital are also ongoing (see, for example: Gibson-Graham (2006), Esteva (2005)).

Return to Text - See Kafer (2013) for a discussion of a relational model of disability, and Bérubé (2010) for a discussion of a capabilities approach.

Return to Text