The author describes two exhibits: Blind at the Museum at the Berkeley Art Museum in 2005, and What Can a Body Do?, at the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College in 2012. She argues for inclusive design in the exhibits themselves, as well as what she calls the exhibit's discursive elements—catalogues, docent tours, symposia, and websites—that not only extend the life of such exhibits but also expand access for attendees and others.

Introduction

"You're standing too close to that painting. You have to stand back to really see it," says a male museum visitor. 1 In her book Sight Unseen Georgina Kleege recounts the story of how a fellow visitor criticized her in this fashion for behaving "inappropriately" during the 1992 Matisse exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art. According to this visitor, in Kleege's words, "there is a right way and a wrong way to see" because "sight provides instantaneous access to reality." 2 Kleege didn't get the chance to tell the visitor that she has macular degeneration, and so needed to stand very close to the paintings in order to get even the most general sense of their overall composition. In many ways Kleege's experience remains emblematic of ongoing problems. The well-established discourse of museum accessibility often works against its own stated goals and I argue that this must be productively destabilized.

Traditionally, issues of accessibility in a museum are confined to programs for those who are blind, deaf, or use wheelchairs. Generic examples of these programs include touch tours of museum collections for those who are blind (at major museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) or tours of exhibitions using an ASL interpreter for the deaf which are popular at museums like the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art also in New York. A museum might also be concerned with ensuring that the museum building is physically accessible for disabled patrons, such as including wheelchair ramps or large font and Braille wall labels.

But this preoccupation with a limited concept of access has ironically obscured the possibility of more generative disability-related content within exhibitions, displays, and other curatorial practices. We might see such moves as the first step towards re-thinking issues of disability and access in an art museum. In other words, I would like to suggest that curators must first express interest in exhibiting critical work about disability and persuade institutions to do so in ways that don't simply reproduce existing biases. Second, curators must take a more critical approach to disability, both conceptually and practically. Often disability is confined to the education or visitor services department of an art museum. The fact that such departments are often quite separate from the curatorial department is itself revealing, in that disability is not widely considered a topic that needs thought, as opposed to treatment. Museums might think of disabled visitors as having so-called medical conditions and requiring physical access, but often they miss the cognitive or cerebral aspects of disabled embodiment.

In particular, I argue that the concept of access should be broadened and extended to exhibition forms that have traditionally been deemed supplementary, such as lectures, symposia, workshops, educational programs, audio guides, and websites. This paper will examine the role of disability—in this case blindness—within the expanded field of discursive art, not only as a practical problem that governs form and access but also an object of representation. Exhibitions that explore themes of disability and normativity redefine viewers' perceptions, and raise new implications for contemporary art exhibition making and discursive programming. The discursive turn has much to offer the disabled subject in its representation in the museum.

We need to rethink some of the key assumptions behind notions of access and accessibility. Instead of merely extending access, institutions need to question how such gestures can in fact perpetuate repressive norms. Often this means asking how their own practices reproduce hierarchies of visibility and recognizability. I'd like to suggest that in pushing the normative regime of disability even further, we must also move beyond the usual understanding of access and re-think what the phrase, visual culture, means in our society, and how our museums and galleries are arbiters for this culture. What would happen if the museum began to re-think of itself as an institution for sensorial culture rather than purely visual culture? This would indeed be radical, given that much of art history itself would be turned on its head.

In experiencing the world upside down, we'll not gain just a new visual experience, but an entirely new sensorial and conceptual one also, and this is exactly the point. Perhaps it is the museum and artists that can lead the way in the challenge to overturn the discursive regimes that simplify disabled communities into reductive binaries. Disability studies scholar Tobin Siebers speaks to this prospect when he writes that "the disabled body changes the process of representation itself. Blind hands envision the faces of old acquaintances. Deaf eyes listen to public television … Mouths sign autographs … Could [disability studies] change body theory [and contemporary art] as usual?" 3 Imagine encountering a gamut of atypical physical experiences inscribed in a work of art. These experiences might range from blindness to deafness, from dwarfism and challenges with scale to how bodies engage with the built environment as a paraplegic in a wheelchair or as an amputee with a prosthetic leg or arm. Other experiences would cultivate a heightened sense of sound, touch, smell, taste, or body language.

Ultimately, I will suggest that we might even need a different concept than access if we mean to engage disability along more productive terms. In order to do so, I will analyze the ways in which disability and accessibility can be problematized within the museum through the use of discursive formats, relying on two case studies: the conference and website that accompanied the exhibition, Blind at the Museum, which took place in 2005 at the Berkeley Art Museum, CA and the website, audio guides and Blind Field Shuttle walk by Carmen Papalia, all attached to the exhibition, What Can a Body Do? that was hosted by Haverford College, PA in 2012. My discussion analyzes how the notion of access informed both shows, and closes by considering how the exhibitions might serve as a model for efforts to rethink reductive or normative understandings of disability and access.

The discursive turn and combatting ocularcentrism

In an essay on curating and the educational turn, Paul O'Neill and Mick Wilson provide an excellent summary of how discussions, talks, education programs etc. have always played a supporting role to the exhibition of contemporary art, but in recent times, the discursive intervention has not only taken on a more central focus, it has turned to become the main event. 4 These discursive practices are framed in terms of education, research and knowledge production and they are often produced as platforms separate to established formats of museum education. The role of the curator has expanded to take on not only the organizational aspects of working with artists, gathering artwork and arranging loans and shipment of work, but it now involves the administration of these discursive mediums.

O'Neill and Wilson also discuss how the rhetorical device of the turn usefully suggests a "logic of development" and a "process of change." 5 We might see the issue of disability as relating to such developments in two ways. On the one hand, exhibitions like Blind at the Museum can be situated within the context of the discursive turn, insofar as they turn away from autonomous exhibition formats. On the other, they also remind us that the discursive turn has largely overlooked the question of disability, and would do well to think hard about the issues that this omission raises. If a turn is by nature about shifting territories, stabilities, and normative positions — its "mere existence…making apparent the need for a more differentiating and discerning perspective" — this would seem perfectly compatible with the objective of creating new discourse around disability itself. 6 If the discursive turn wants to make good on its emancipatory promises, as articulated above, then it needs to turn towards questions of access for the widest possible range of audiences.

The discursive turn bears a larger potential outside the museum as well, insofar as it could help us rethink the disabled subject in terms of the critique of ocularcentrism — the longstanding bias toward vision in Western thought and culture. As historians like Martin Jay and David Levin have shown, such a tendency goes back as far as Plato's notion that ethical universals must be so-called accessible to the ostensible mind's eye, and continues through the Renaissance into modernity. 7 What if the clarity of truth was not beholden to vision or the mind's eye? As demonstrated by Georgina Kleege's experience at the Museum of Modern Art, many still believe that there really is a right and a wrong way to see, even a true and false way.

Against such tendencies, Georgia Warnke has cited contemporary critics who argue that "ideology is no longer connected to distortions in vision but to distortions in language." 8 For example, scholar Michael Davidson points out how blindness, like other social categories, is constituted within discursive regimes that assign it with specific values. 9 While vision is typically identified with knowledge, blindness is often equated with lack, as in expressions such as "I must have been blind not to see the implications," or "I've lost sight of the goal." Davidson suggests that in order to counter ocularcentrism, more discursive events need to take place so that an alternative regime can be generated. The Blind at the Museum conference, to be discussed below, is a concrete example of what form this alternative regime might take. At a major event such as this, scholars come together that either have direct or indirect experience with blindness and interacting with objects in a museum. They have opportunity to discuss issues of access and how a new language might be created that is more inclusive and minimizes patronizing expressions (such as the ones discussed above) that many people often take for granted. In other words, many people often don't think about the exclusionary impact of these words towards the blind community.

Events such as the Blind at the Museum conference then, heralds great promise for the role that the current trend or move towards discursive practice plays in art museums in relationship to disability rights. Rethinking language around disability and access within the current societal discursive regime as articulated by Davidson in order to combat ocularcentrism goes hand-in-hand with re-thinking curatorial and exhibition practices within the discursive turn in the museum. This will ultimately expand what we might like to think of as "access." 10

Blind at the Museum

Blind at the Museum, in the Berkeley Art Museum's Theater Gallery, which was curated by curator Beth Dungan and artist Katherine Sherwood, asked how blindness might change our sense of what it means to view a work of art, ultimately prompting viewers to imagine new ways of seeing and knowing. Twelve artists participated in the exhibition, most of them blind, and one of them deaf, among them Sophie Calle, the French neoconceptualist artist; the sculptor Robert Morris; multimedia artists Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and Joseph Grigely; and photographers John Dugdale and Alice Wingwall (fig. 1). Rather than thinking about blindness and sight as polar opposites, the artists explored a wide range of optical experiences—peripheral vision, distortion, floaters—along a continuum. The artists emphasized sound, touch, and multisensory expression through a variety of media; they investigated the unreliability of vision and re-thought the activities of viewing within the museum. Some offered a meditation on the limits of the optical; others explored the metaphors and stereotypes of blindness; and a few highlighted the embodied experience of visual impairment.

Figure 1: Installation photo from Blind at the Museum (2005) at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, January 26 through July 24, 2005.

My analysis will focus on two key aspects of the exhibition: the two-day conference that accompanied the show; and the exhibition's website, which linked to an interview carried out for local radio.

Blind at the Museum conference

On March 11-12, 2005, the Blind at the Museum conference brought together scholars, artists, and museum professionals to explore issues surrounding access to visual art. Questions under discussion included: What are the relations between seeing and knowing, or between words and images? To what extent are traditional notions of beauty founded in sight or seeing, and how are these notions being transformed and called into question precisely within that site of beauty, the museum? How do artists with impaired sight represent their visual experience? What role can technology play, as both tool and artistic medium, in the accessible museum of the future? Some of the most compelling answers to these questions are to be found in the paper delivered by Michael Davidson.

Michael Davidson's talk, entitled "Nostalgia for Light: Being Blind at the Museum," focused on the theme of recent exhibits and colloquia exploring blindness and museums: how the blind have a great deal to teach the sighted, "not only about blindness but about seeing and about the assumptions that sighted persons bring to the larger cultural field." 11 Davidson describes in detail how some of the pieces in the BAM exhibition attempt such teaching, in addition to undertaking visual analysis of a number of other sources pertaining to his topic, ranging from photographs and films to philosophical approaches to curating (Derrida's Memoirs of the Blind at the Louvre). For example, Davidson says that the ocularcentric focus of modern art is dramatically contested when we consider the work of blind photographers in the Blind at the Museum exhibition such as Alice Wingwall, who re-site the visual through the technological means by which modernist ocularity was created and more. Davidson says:

In their work the meaning of the photograph is diverted from the developed print to the discursive processes that precede and accompany the clicking of the shutter. In each of these cases, the great theme of modernist defamiliarization is revived to ask for whom is the familiar familiar and by what presumption of access is it made strange? 12

Specifically, in Alice Wingwall's work, Hand Over Dog, Joseph at the Temple of Dendur (1995; fig. 2) the artist uses her beloved guide dog named Joseph, her camera, as well as her own distorted eyesight as a layering of lenses to present a unique perspective. It features a zoomed out perspective of the museum room housing the Temple of Dendur, which is situated at the top center, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The photographer's hand can be seen in the bottom center of the image as a hazy and ambiguous form pointing in direct alignment towards the center of the temple entrance. Joseph is seated attentively in profile facing this hand. Wingwall is pointing towards the temple as if directing our attention to the theatricality of the events taking place around the platform. Because her hand is the only element not in focus, she seems to be drawing a relationship between her own blindness and Joseph's role as her alternative tool of vision.

Figure 2: Alice Wingwall, Hand Over Dog: Joseph at the Temple of Dendur, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.

Most appropriately, given the context of Davidson's paper, he advocates for the discursive construct evident in the artists' work and within the institutional infrastructure of the museum in concert with my intimation that the discursive turn has much to offer the disabled subject in its representation in the museum. He applauds the artistic framing of optical and ocular character of art not simply to "reinforce the imperative of sight but to resite seeing as a discursive construct, embedded in debates about what it means to live in the modern world." 13 He concludes by again emphasizing how the blind artists in Blind at the Museum provide a new rhetoric to see the image in an ocular-centric world. Davidson's paper does much to support the move away from ocularcentrism and how the discursive turn has an important role in shifting perceptions of the blind subject—what seeing can become and can mean in new contexts, as demonstrated in the photography of both Wingwall.

www.blindatthemuseum.com

Following on from the power of the discursive construct discussed in Davidson's paper, the still-operational Blind at the Museum website also allows us to think through these questions with respect to virtual platforms. A website has the potential to function as a critical form of discursive exhibition as it broadens access to those who can't visit and acts as an archive for future use. It also enables discussion in forums on the subjects emanating from the show so that intelligent conversations can evolve and develop comprehensively. In the Blind at the Museum website, visitors encounter a fully active, comprehensive site with main subject headings such as "Conference," "Forum," "Artists" and "Links." 14 The "Conference" heading includes links to some of the papers that were given and the "Artists" link provides both image and text for what was seen at the exhibition (fig. 3). Importantly, the website also provides a link to the MP3 of the original audio descriptions for each of the works, keeping true to the theme of the show being accessible to the blind. 15 The website is accessible for the deaf in providing all the sound-based information on the MP3 tracks in written form, so that it becomes multi-sensorial.

Figure 3: Screen shot of home page for Blind at the Museum website.

The website also includes a link to a broadcast on the local public radio station KQED, in which the program Forum interviewed two of the artists, John Dugdale and Pedro Hidalgo, along with the curator Beth Dungan and the conference keynote speaker Georgina Kleege. 16 While the interview was mostly informational, a telling moment occurred when the interviewer opened up the conversation to include questions from the listening public. A woman named Esther called in and described her visit to the exhibit with her blind father, commenting on how disappointed she felt that the art in the exhibit ultimately perpetuated the museum as a space that privileges those with vision, given the work was primarily visual. Esther said that apart from Joseph Grigely's audio installation, You (2001), there was very little work that her father could enjoy. Despite Davidson's earlier assertion in his paper that blind artists were attempting to resituate seeing as a discursive construct and demonstrate how seeing could be seen differently, the work was still predominantly visual, thus reinforcing the hierarchy of the ocular. The curator, Beth Dungan, seemed awkward and uncomfortable with Esther's criticism, and did not really offer a satisfying reply. Instead she was evasive and changed the subject. Perhaps Dungan realized that the exhibit had its shortcomings in this ostensible sense and didn't care to elaborate on this oversight.

However, Kleege suggested that even though Blind at the Museum had offered many typical accessible components to the display — such as ASL interpreters at the conference and for hearing impaired guided tours, as well as audio descriptions at the exhibition and Braille wall labels — what was really important about Blind at the Museum was the suggestion that the museum and artistic practice were at a sort of threshold or juncture. Kleege imagined that artists in the future would be inspired by the exhibition to create art that can be experienced by a number of different modalities, such as tactility, verbal or sound elements. While many artists have done precisely this, such as installations that create immersive environments, like the work of Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto, or the Happenings of Allan Kaprow, we shouldn't rule out the possibility that additional innovation that will come from artists with vision impairments or other disabilities, such as the blind artists in Blind at the Museum. 17

What Can a Body Do?

In this section, I will reflect on how notions of access and the discursive turn (with emphasis on the blind visitor experience) were broadened and deepened as a development of and extension to Blind at the Museum, by analyzing the What Can a Body Do? exhibition, curated by myself and presented at Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College from October 26 — December 16, 2012 (fig. 4). The exhibition attempted to narrow the question originally posed by French philosopher Gilles Deleuze into: "what can a disabled body do?" In my Introduction to the catalogue essay, I write: "Further, this exhibition asks, what does it mean to inscribe a contemporary work of art with experiences of disability? What shapes or forms can these inscriptions take? How, precisely, can perceptions of the disabled body be liberated from binary classifications such as normal versus deviant or ability versus disability that themselves delimit bodies and constrain action? What alternative frameworks can be employed by scholars, curators, and artists in order to determine a new fate for the often stigmatized disabled identity?" 18 Nine contemporary artists participated in the exhibition, including Joseph Grigely, Christine Sun Kim, Park McArthur, Alison O'Daniel, Carmen Papalia, Laura Swanson, Chun-Shan (Sandie) Yi, Corban Walker and Artur Zmijewski. They each demonstrated new possibilities for the disabled body across a range of media by exploring bodily configurations in figurative and abstract forms.

Figure 4: Installation photo of What Can a Body Do?, Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, Haverford College, PA, October 26—December 16, 2012; Photo credit: Lisa Boughter.

In the foreword to the exhibition catalogue for What Can A Body Do?, faculty members at Haverford College Kristin Lindgren and Debora Sherman write of the exhibition's commitment to access: "Access involves more than checking off a list of practical accommodations. It is a way of thinking about the world that challenges us to imagine how another body, another self, experiences it… [in this exhibition] access is treated not as an afterthought but as a creative process intrinsic both to art practice and curatorial practice." 19 Even more than art and curatorial practice though are the various discursive elements of the exhibition that included the catalogue that is accompanied by a CD with audio versions of all the catalogue text, which features the voices of the curator, artists and students from Haverford College. The extensive exhibition website, still active, provides audio links to the catalogue essays and artists' bios as well as audio descriptions of the work written and recorded by the artists and Haverford students. Visitors could also access the descriptions via iPod while engaging with the work in the gallery. In addition, Vancouver-based visually impaired artist Carmen Papalia was awarded a Mellon Tri-College Creative Residency, and led students on a Blind Field Shuttle throughout the campus. I will elaborate on the website, audio guides and Blind Field Shuttle.

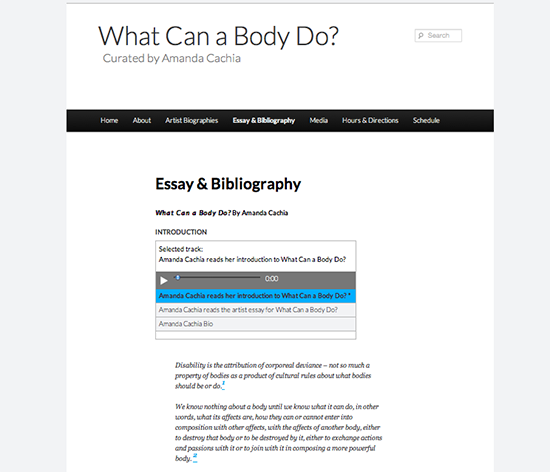

http://exhibits.haverford.edu/whatcanabodydo/ & Audio Guides

The What Can a Body Do? website was designed by Haverford College web team Sebastianna Skalisky and David Moore and is the first exhibition website of its kind for the College in that it is the most comprehensive universally-designed website. Apart from the entire content of the website being available to blind readers via screen reader, the website also includes almost all text and image-based content in the exhibition in audio form. Conversely, any image-based content that incorporates sound is accessible for a deaf visitor through written audio transcripts. Under the heading "Media," visitors will find the audio descriptions of all the art work, and under the other headings, such as "Essay and Bibliography" (fig. 5), or "Artist Biographies," audio transcriptions of this text can be found. Also embedded into this section are the mostly captioned videos of some of the works in the show, including Artur Zmijewski's Eye for an Eye (1998), the trailer for Alison O'Daniel's Night Sky (2011) and Park McArthur's It's Sorta Like a Big Hug (2012). An interview with Christine Sun Kim, artist and Mellon Tri-College Creative Resident, can also be watched here, that documents her sound performance at the opening reception, alongside an essay film entitled The Rupture, Sometimes (2012) by PhD Communication student at the University of Pennsylvania, Kevin Gotkin, that features nine artists and scholars discussing the potential of disability to expand and enrich our ways of thinking.

Figure 5: Screen shot from the What Can a Body Do? website, featuring audio transcriptions of all text and image-based content in the exhibition

Focusing specifically on the audio descriptions, I invited both the artist and the students (facilitated by faculty members) to contribute to the audio and written transcripts. First off, it was important to include the artists in this process as a means to titillate their thinking towards access and how it might form a productive dialogue with their art-making process, now and in the future. In some instances, some of the artists commented that they had never thought about audio description for their work before, and found the process interesting and useful. The gallery's student staff and exhibition interns, led by Aubree Penney and Michael Rushmore, also wrote and recorded audio descriptions of each piece. Of this experience, Kristin Lindgren says that, "Most students brought to this task a strong interest in visual art but no previous engagement with disability studies. Indeed, some were skeptical that an exhibition focused on disability would be aesthetically and conceptually compelling. Producing an audio description, however, enabled each student to engage intimately with the work of one of the artists and to envision its place in the exhibition." 20 Naturally, then, incorporating the voices of the curator, the artists and the students as part of this audio description exercise really meant that the audio description, and consequently the exhibit website, began to function akin to the nature of a television, where various channels will instantaneously give you access to a multiplicity of styles, techniques, opinions and sensibilities. Similarly, the website and the various audio tracks and written audio transcriptions give the museum visitor to What Can a Body Do? a plethora of means in which to engage with the work, through various perspectives. In some cases, the visitor will have the opportunity to hear up to three different descriptions of the same work. According to Lindgren, "What Can a Body Do? really attempted to bring disability into conversation with multisensory experience, the literary practices of close reading and ekphrasis, and gallery protocols" through these discursive devices I mention. 21

Some of the multi-layered outcomes of the website and audio descriptions include the firm commitment by the gallery to create audio description for every future exhibition. These discursive tools also made an impact in scholarly circles where for instance, Mara Mills, Assistant Professor in the Media, Culture and Communication Department at New York University has expressed her interest at including the exhibition in her syllabus for her upcoming course, entitled Disability, Technology and the Media. She said of the exhibition, "it's one of the best models I can think of for arts inclusion / multimodal spectatorship." 22 However, while every effort was made by the gallery staff and curator to ensure the highest standards of accessibility (following Smithsonian Museum of American History guidelines) most of the work in the exhibition itself could not be touched and was still predominantly visual, thus still excluding audience members with hearing and visual impairments. Echoing the criticism the curators received in the radio interview for Blind at the Museum, a student/intern at the gallery explained her interaction with a mother who visited the exhibition with her blind son. She had complained that while the show was important for offering inclusivity around differences, there were still problems around its various exclusions to certain types of audiences. So on the one hand, while the gallery (and curator) are being disciplinary towards certain established ADA guidelines of what is considered acceptable and accessible for a wider range of audience members, we are not being able to entirely overcome entrenched bias towards visual culture as the dominant mode of experiencing visual art within the museum/gallery context. My hope is that in my future curatorial endeavors with the rhetoric and discourse of disability, I'm able to push the normative regime of disability even further in tandem with moving beyond access and entirely re-thinking what visual culture means in our society. Such tension supports the argument of my paper, in promoting the possibilities for a new form of access, where the physical limitations in a gallery context can be flipped into more hopeful pathways within the discursive turn.

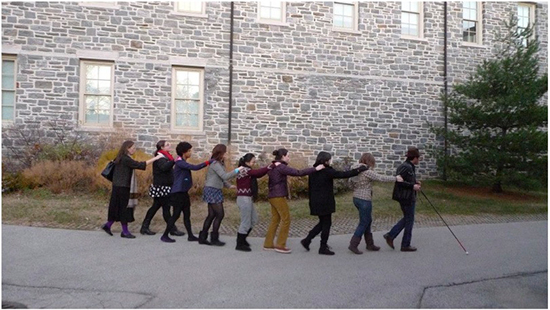

Blind Field Shuttle by Carmen Papalia

Students from Haverford College and two other colleges in the surrounding area, Bryn Mawr, and Swarthmore, had the opportunity to work directly with Carmen Papalia through the Mellon Tri-College Creative Residencies Program. Carmen led various students and faculty members on his Blind Field Shuttle, that involved navigating the Haverford College campus using unfamiliar modes of orientation (fig. 6). In Papalia's work, relationships of trust and explorations of the senses unfold as the artist leads walks with members of the public in Blind Field Shuttle as part of his experiential social practice. This work is a non-visual walking tour where participants tour urban and rural spaces on foot. Forming a line behind Papalia, participants grab the right shoulder of the person in front of them and shut their eyes for the duration of the walk. Papalia then serves as a tour guide — passing useful information to the person behind him, who then passes it to the person behind him/her and so forth. The trip culminates in a group discussion about the experience. As a result of visual deprivation, participants are made more aware of alternative sensory perceptions such as smell, sound, and touch — so as to consider how non-visual input may serve as a productive means of experiencing place.

Kristin Lindgren reports on her experiences of Papalia's work that included students from one of her classes:

Eyes closed, one hand on the shoulder of the person in front of us and the other grasping the air for tactile clues, we moved as one winding organism, passing information down the line through touch and voice. Occasionally the organism broke apart, hand slipping off of shoulder, a disorienting, generative rupture. The texture of the ground beneath us—grass, gravel, pavement, cobblestone—became a source of information and orientation. The warmth of the early December sun, the sudden chill as the sun was blocked by a wall or a building, the flicker of light and dark, noticeable even with eyes closed, helped us to locate ourselves in space. The whirring of heating condensers signaled that we were near a building. Gnarly tree limbs, rough stone faces on a sculpture, the predictable geometry of a chainlink fence: all provided clues in this new landscape. We were still inexperienced in navigating by these compass points, however, so most of us had no idea where in the world we were. 23

Figure 6: Carmen Papalia on leading his Blind Field Shuttle on the Haverford College campus, December, 2012.

This testimony gives proof to how discursive practices, such as the social practice of Papalia's walk, can really be used as a tool for widening a visitor's (or in this case a student's) engagement with work that posits themes of disability. Papalia's navigation of the walk as someone who is blind opened new pathways for using the senses that we often taken for granted, such as smell, touch and sound, given his instructions to close one's eyes during the walk and so removing access to the visual. The students were able to grasp new ways of orienting themselves in a familiar environment that became dynamically unfamiliar through the walk. This moment of disorientation and reorientation, emphasized by multi-sensory modes of being, hand in hand with access to multi-channel audio description, really gave the exhibition an edge. These discursive components add much value, longevity and permanency to not only the images in the exhibition, and the textual analysis around it, but also to the thinking, interacting with and destabilizing of access itself.

The Future of Museums & Access

In conclusion, while the Blind at the Museum and What Can a Body Do? exhibitions served and still effectively serve to raise issues around the possibilities and limitations of access, there is still more work to be done. More elaborate and accessible discursive programs need to be introduced across a broader range of museums and galleries in order for issues concerning disability to find a permanent place in its rooms and in the minds of those who work in them. For example, as technology evolves, audio description and interactive touch-screens in museums are becoming more complex, as visitors deal with interfaces beyond a painting, sculpture or even video. How can text, Braille and other forms of signage contribute to an intertextual experience of an exhibit? Can new modes of access become part of the discourse that an exhibit generates or into which it intervenes? These questions will serve as important paradigms for building museums and planning exhibitions in the decades ahead.

The future of museums depends on their creating a site for meaningful, activist, discursive and intellectual exchanges between the widest possible range of people in order to account for a greater spectrum of human physical, perceptual, cognitive and sensorial experience. Disabled communities can no longer be segregated to special collections or special, adjunct programming. The contemporary art world and beyond can begin to shift negative perceptions and meanings of the disabled body in order to make room for its more nuanced, complex representation across diverse artistic fields. Blind at the Museum and What Can a Body Do? stand as the beginning of possible alternative framework that can be employed by scholars, curators and artists in order to determine a new fate for the disabled figure in contemporary art and in life. In other words, more than just offering a conventional exhibition that explores the experience of blindness or other types of impairments, the new discursive format can open the door for a huge variety of programming regarding complex embodiment. Conferences, websites, audio guides and blind walks are just the start.

Further, if access is no longer relegated to the education or visitor services departments of an art museum, and spreads not only through the curatorial department but through every department, wall, door and window of an art museum, what would that mean for the art museum? Perhaps access would no longer be an add-on to a museum budget, or as an after-thought for a curator when installing an exhibit without large-print labels. Perhaps programming material that is accessible will no longer be considered unattractive, but can be treated with more aesthetic potential, care, sensitivity and intelligence. It might be embedded into all exhibition planning in the future as a matter of course, rather than as a last-minute addition. Access can be approached as a tool that will widen perspectives and thinking around practices that are in need of reinvention and revision. Ultimately, if access is to be made radical and controversial, as these scholars have called for, the very concept of access also needs to be re-visited in order to develop new attitudes, perceptions, and language that counter its stigmatized status.

Given that disability's marginalized position is generated by a mainstream societal discursive regime, the museum's discursive turn offers an important solution to combating and shifting disability's loaded language and thinking. Discursive practices must initiate much more fluid and organic conversations about how art moves us and why it matters, incorporating multiple sensorial perceptions where the ocular and the discursive can work cohesively. Talking in this way will strengthen and make more complex the point of the discursive turn. Not only should the voice of disability become a participant in such conversations, it needs to be a vital one, instead of marked absences, awkward silences and skewed representations surrounding disability.

Bibliography

- www.blindatthemuseum.com, Accessed March 15, 2012.

- http://exhibits.haverford.edu/whatcanabodydo/ Accessed September 15, 2012.

- KQED radio Forum Interview with John Dugdale, Beth Dungan, Pedro Hildago and Georgina Kleege, hosted by Dave Iverson, Friday, May 27, 2005, 10am. http://www.kqed.org/a/forum/R505271000, Accessed March 15, 2012.

- Cachia, Amanda. "What Can a Body Do?" What Can a Body Do? curated by Amanda Cachia. Pennsylvania: Haverford College, 2012.

- Davidson, Michael. "Nostalgia for Light: Being Blind at the Museum." Blind at the Museum conference, Berkeley Art Museum, March 11-12, 2005. Published in Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body. University of Michigan, MI: 2008.

- Kleege, Georgina. "The Mind's Eye." Sight Unseen. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Levin, David Michael. "Introduction." Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision. Edited by David Michael Levin. Berkeley, California: University of California, 1993.

- Lindgren, Kristin and Debora Sherman, "Foreword." What Can a Body Do? curated by Amanda Cachia. Pennsylvania: Haverford College, 2012.

- Lindgren, Kristin. "Growing Rhizomatically: Disability Studies, the Art Gallery and the Consortium" by Amanda Cachia, Kelly George and Kristen Lindgren, January 2013 (written for an upcoming issue of Disability Studies Quarterly).

- Mills, Mara email message to author, December 26, 2012.

- O'Neill, Paul and Mick Wilson. "Introduction." Curating and the Educational Turn. Amsterdam: De Appel Open Editions, 2010.

- Sandell, Richard and Jocelyn Dodd. "Activist Practice." Representing Disability: Activism and Agency in the Museum. Edited by Richard Sandell, Jocelyn Dodd and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson. New York and London: Routledge, 2010.

- Siebers, Tobin. "Body Theory." Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2008.

- Warnke, Georgia. "Ocularcentrism and Social Criticism." Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision. Edited by David Michael Levin. Berkeley, California: University of Califonia, 1993.

- Williamson, Aaron. "In the Ghetto? A Polemic in Place of an Editorial." Parallel Lines Journal 2011, 5 Mar 2012 http://www.parallellinesjournal.com/

Amanda Cachia is an independent curator from Sydney, Australia and is currently completing her PhD in Art History, Theory & Criticism at the University of California, San Diego. Her dissertation will focus on the intersection of disability and contemporary art. She held the position Director/Curator of the Dunlop Art Gallery in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada from 2007-2010, and has curated approximately 30 exhibitions over the last ten years in London, New York, Oakland, and various cities across Australia and Canada.

Endnotes

-

Georgina Kleege, "The Mind's Eye" in Sight Unseen (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999), 93.

Return to Text -

Ibid., 96.

Return to Text -

Tobin Siebers, "Body Theory," Disability Theory (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2008) 54.

Return to Text -

Paul O'Neill and Mick Wilson (eds.), "Introduction" in Curating and the Educational Turn (Amsterdam: De Appel Open Editions, 2010), 15.

Return to Text -

Paul O'Neill and Mick Wilson (eds.), "Introduction" in Curating and the Educational Turn (Amsterdam: De Appel Open Editions, 2010), 15.

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

Georgia Warnke, "Ocularcentrism and Social Criticism" in Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision, (ed.) David Michael Levin (Berkeley, California: University of Califonia, 1993), 287.

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

Michael Davidson, "Nostalgia for Light: Being Blind at the Museum," Blind at the Museum conference, Berkeley Art Museum, March 11-12, 2005. Published in Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body (University of Michigan, MI: 2008), 143.

Return to Text -

However, I also want to be quick to point out that there need not be an opposition between the ocular and the discursive. David Levin has said that Georgia Warnke develops the idea that "the cultivation of perception and sensibility exemplified by an 'aesthetic education' could multiply our perspectives, expand our horizons and deepen our moral vision, contributing significantly to the discursive formation of those fusions." In other words, while the anti-ocularcentric potential of the discursive turn has an important combative role in support of the disabled position, the possibilities retained within other modes of sensorial perception, not excluding vision, must ideally be intertwined with it in a museum for a more powerful and well-rounded discursive form. After all, it is also in the material forms of representation that identities become sedimented, so perhaps it is worth thinking about the discursive construct more scrupulously within and without these boundaries in order to break down binaries (like "normal" versus "pathological"). Levin, David Michael. "Introduction." Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision. Edited by David Michael Levin. Berkeley, California: University of California, 1993.

Return to Text -

Michael Davidson, "Nostalgia for Light: Being Blind at the Museum," Blind at the Museum conference, Berkeley Art Museum, March 11-12, 2005. Published in Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body (University of Michigan, MI: 2008), 143.

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

Ibid., 166.

Return to Text -

www.blindatthemuseum.com, Accessed March 15, 2012

Return to Text -

Despite this, it is not clear to me if the website is easily navigable for a blind person so that they can locate the MP3 tracks.

Return to Text -

KQED radio Forum Interview with John Dugdale, Beth Dungan, Pedro Hildago and Georgina Kleege, hosted by Dave Iverson, Friday, May 27, 2005, 10am. http://www.kqed.org/a/forum/R505271000, Accessed March 15, 2012

Return to Text -

Despite these promising implications, curators and artists remain creatures of habit and are still working with material and with artists that for the most part excludes any discourse or framing around disability. While there are certainly prominent "mainstream" artists that have disabilities, such as Chuck Close and Ryan Gander, both of these artists remain silent about their disabled experiences. In other words, their disabled experiences are rarely mentioned or discussed in the context of their art practices, by both the artists themselves and the critics who write about their work. While this is a personal choice by the artist and is to be respected, Close's work particularly has a very clear connection to his disability (prosopagnosia - face recognition deficit) so it is unusual that this connection between his paintings and his diagnosis isn't mentioned more frequently and with comfort. Further, while there are institutions such as Creative Growth in Oakland and Creativity Explored in San Francisco that work with mentally and intellectually disabled communities, these institutions remain arguably ghettoized and for the most part remain separated from mainstream art discourse and exhibition venues. In 2011, British artist Aaron Williamson said, "In the mainstream, the stakes for critical appreciation are high and artists expect a rigorous consideration of their efforts … criticism, rather than celebration is the bedrock of mainstream art and, in many ways, forces artists to take risks and to oppose cultural complacency. [But] with disability art today, mainstream art critics may simply be unprepared to comment negatively on artists who they consider to be socially disadvantaged, or, even worse, deserving of pity. The critical silence towards disability art might, therefore, be considered to operate from both within and without." If the majority of mainstream critics believe this is their only recourse in writing and talking about disability, the language and attitudes surrounding the work need to be reformulated. Aaron Williamson, "In the Ghetto? A Polemic in Place of an Editorial" in Parallel Lines Journal, In the Ghetto, ed. Aaron Williamson, 2011, 5 Mar 2012 http://www.parallellinesjournal.com/

Return to Text -

Amanda Cachia, "What Can a Body Do?" in What Can a Body Do? curated by Amanda Cachia (Pennsylvania: Haverford College, 2012), 5-23.

Return to Text -

Kristen Lindgren and Debora Sherman, "Foreword" in What Can a Body Do? curated by Amanda Cachia (Pennsylvania: Haverford College, 2012), 3-4.

Return to Text -

Kristin Lindgren, "Growing Rhizomatically: Disability Studies, the Art Gallery and the Consortium" by Amanda Cachia, Kelly George and Kristen Lindgren, January 2013 (written for an upcoming issue of Disability Studies Quarterly), 7.

Return to Text -

Ibid., 8.

Return to Text -

Mara Mills email message to author, December 26, 2012

Return to Text -

Kristin Lindgren, "Growing Rhizomatically: Disability Studies, the Art Gallery and the Consortium" by Amanda Cachia, Kelly George and Kristen Lindgren, January 2013 (written for an upcoming issue of Disability Studies Quarterly), 8-9.

Return to Text