This essay uses Couser's presentation of autopathography as a frame for disseminating creative autoethnographic research practices. The preface outlines the conceptual framework for the research, which critically explores personal, cultural, and institutional contexts of mental disability discourses in response to Foucault's thesis that the arts dismantle normalizing myths about mental disability. Following Foucault's treatment of visual, performing, and literary arts as a homogeneous entity, the ensuing story demonstrates how traditional and emerging art practices and creative writing can be hybridized to create complex representations of disability that challenge ableist, normalizing discourses.

Preface

In Recovering Bodies, Couser (1997) coined the term autopathography to categorize autobiographical narratives of illness or disability. The book explored illness narrative as life writing and its potential to engage contemporary politics of the body (pp. 14-15) and to represent an entire life "to the degree that the writer identifies the self with the body" (p. 14). Recovering Bodies devoted considerable attention to subjectivity on conditions that "have been […] particularly stigmatizing or marginalizing" (p. 15), although mental illness narratives were omitted, partly because "dysfunctions like schizophrenia and depression raise complex and largely independent issues—such as the representations of altered consciousness—that [Couser] was ill-equipped to address" (p. 17).

Since Recovering Bodies, Disability Studies scholars and others who experience mental disability (Price, 2011) have contributed a wealth of conventional first-person narratives on mental disability that often rebut stigmatic and oppressive discourses. Donaldson (2002), for example, describes how people with mental disabilities are unjustly blamed for their conditions and considered weak-willed and cognitively inferior, and Nicki (2001) avows that we are routinely ridiculed for not just "snapping out of it." Jamison's (1996) pioneering concern over "coming out" as an academic experiencing mental disability has been expanded by others, including Clark (2007) who suggests that "there is no illness, except perhaps AIDS, that bears the shame still attached to mental illness and that is hidden so well in the academy" (p. 128). Such personal narratives bolster other humanities research, such as Price's (2011) analysis of rhetorics of mental disability in academia and research on performance and performing arts projects that involve mental disability (Eisenhauer, 2010a, 2010b; Johnston, 2008; Kuppers, 2003, 2007, 2008), as well as scientific research on stigma and mental disability (Boyd, Katz, Link, & Phelan, 2010; Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan & Penn, 1999; Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Hinshaw, 2007; Link & Phelan, 2001; Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Phelan, Link, Stueve, & Pescosolido, 2000; Rüsch et al., 2009; Wahl, 1995, 1999).

To elaborate this literature, I employ autopathography as a methodological frame for disseminating creative autoethnographic research on discourses of mental disability. Bochner and Ellis (2002) characterize autoethnography as a kind of ethnography, a qualitative research methodology that socially contextualizes the story rather than looking at its author. Autoethnography gazes back and forth between internal vulnerability and external, social and cultural aspects of personal experience (Ellis in Scott-Hoy, 2002). Artist Scott-Hoy (2002) uses autoethnography to merge conventional methods of painting, performance, storytelling, and research. She equates autoethnography to artmaking practices that "[explore] the experience from within, then from without" (p. 283).

Like Scott-Hoy, I use autoethnography as "a way of further involving the viewers" of my artworks (p. 283), and I deliberately weave images and words as a performative method, an act of hybridity (Picart, 2002) to "challenge comfortable binaries through the use of intertwining genres" (p. 259). The relationship of text and image, and the variety of images which includes everyday photographs, visual journal work, and completed artworks, reflect my intent to explore the interstices "between identities and places" (Brueggemann, 2009) as a metaphor for recognizing disability as a matter of complex embodiment (Siebers, 2008). Like other Disability Studies artist-authors who experience mental disability (Eisenhauer, 2009; Roman, 2009), this essay explores dynamic possibilities for visual culture and art production, which are underrepresented in Disability Studies (Derby, 2012). My intention is not simply to relay, read, or respond to my art and vernacular images, but to reuse, reread, and revitalize them with and through life writing. By blurring disciplinary boundaries through hybridity, I aspire toward transdisciplinary research that refutes academic battles over the supremacy of text/image, science/humanities/arts, and scholarly research/creative activity. The hybridity of my essay reflects Foucault's (1965/1988) treatment of the arts as a homogeneous entity, which underlies his thesis (1964/1995, 1965/1988) that the collusion of madness and the arts—in Artaud, Nietzsche, and Van Gogh—dismantles the normalizing myth that reason begets creativity and productivity.

1 a: an unforeseen and unplanned event or circumstance b: lack of intention or necessity: chance <met by accident rather than by design>

2 a: an unfortunate event resulting especially from carelessness or ignorance b: an unexpected and medically important bodily event especially when injurious <a cerebrovascular accident> c: an unexpected happening causing loss or injury which is not due to any fault or misconduct on the part of the person injured but for which legal relief may be sought d —[sic] used euphemistically to refer to an involuntary act or instance of urination or defecation

3: a nonessential property or quality of an entity or circumstance <the accident of nationality>

—Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (2012)

1. Incidents and Accidents

There was an incident …

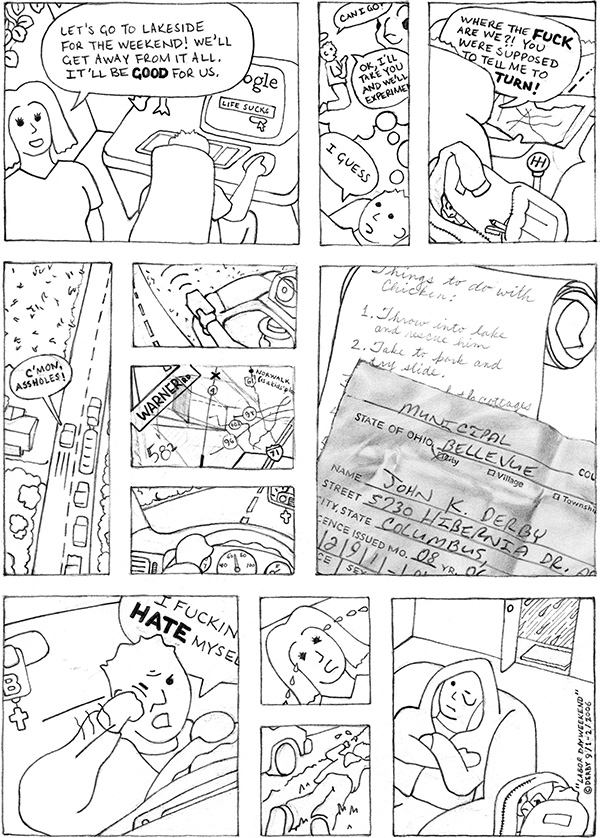

Figure 1. Labor Day Weekend, J. Derby, 2006.

Actually, there were many—as far back as I can remember. But this one was pivotal; it marked a shift from unmanageable stress to full-scale obsession with suicide.

My first year of doctoral studies was going well, except for the problems. I hadn't wanted to move back to Ohio, for one. Park City was everything I had dreamed of, and I'd built my life around skiing, mountain bike racing, and the solemn liturgy and music of the Cathedral of the Madeleine in Salt Lake. I worried about leaving, and while I told myself it would only be temporary, I knew I'd never come back. But it had to be done—Lori hated Utah. Besides, I wanted a PhD, a trophy more prestigious than all of my race trophies combined, and Ohio State was the best choice. The best offer. The best reputation. Lori could work.

At my last Mass at the Cathedral, I wept. There would be no more incense, Gregorian chant, or scholarly homilies. I sobbed on bike rides. I would lose the wilderness, the deep powder snow in Jupiter Bowl, the pristine backcountry lakes, the national parks, the golden aspen rustling in the winds. Ohio lacked natural beauty and the perfect balance of religion, exercise, scenery, time to think, and fragrant pines. And the painkillers—legally prescribed, of course—were no longer making things beautiful.

Figure 2. American Road Train / Jupiter Peak (digital diptych), J. Derby, 2012.

The move was rough. The U-Haul broke down several times and we were towed back to Salt Lake. There we were—Lori, me, and my brother Bill, following a giant tow truck with our 24-foot moving van and our Acura on a full car trailer. Our worldly possessions stretched across I-80 in a perverse American tribute to the Australian road train, the big engine that couldn't, dragged back down the mountain that it failed to overcome. To me it was a simple metaphor: the move was not meant to be.

My first quarter was great—the excitement of debate, new ideas, big dreams, drugs—I had it all, except the things I had lost. I was having trouble concentrating, so I underwent extensive testing. Some of the news was devastating. "There is some good news," my tester said. "Your IQ is above average." I looked at the results in dismay. It couldn't be right—it was terrible! Maybe it was the painkillers. No, I was a fake, an imposter. I was fucking stupid! I had heard it many times growing up and I knew it was true. Then my sister Liz almost died—some kind of rare pneumonia. She lost her baby but she survived. Our prayers saved her! Lori was also struggling from her own depression caused by the stress of working in a hostile urban high school and the move.

The woman who did my testing wasn't sure what I had. Maybe ADD. Definitely post-traumatic stress disorder from my childhood. Generalized anxiety disorder was most likely the main thing, but she couldn't say because she only did testing. I never mentioned the drugs. Then I met with a psychiatrist who didn't bother to look at the test results. He asked me some questions: "Any history of mental illness in your family?" Quite a bit. "What kind? Who? Do you feel sad?" I didn't. "Any difficulty sleeping?" My whole life. "I see. Do you have trouble concentrating? Do you have friends? Hmmm …. What about your childhood?" He shook his head. "You're a tough one to diagnose—little bit of everything. Well, what you have is bipolar disorder." Bipolar disorder. Just like that. I was bipolar. My grandfather had had it. Liz had it—well, she had something. He gave me a mood stabilizer. When I was stable, I'd be able to focus. But it didn't work. So I was prescribed Ativan® to calm me down. I was working fifteen hours a day, every day, so I tried Strattera® for concentration, then Adderall®.

In the spring, I took too many hours and one professor hated my work. I got a B+ on my first paper. I knew what that meant. So I put everything I had into the final project. I was burning through the drugs faster, trying to quit before it got really serious. I pushed and pushed. I wrote the best paper of my life, surely good enough to redeem my grade. In a few days I would rest in Vegas, crashing hard from the drugs, tired from the stress and dark fits of rage. I would be relieved to see my final grade, which would prove my worth. Probably an A-, hopefully an A …

Figure 3. Hand-printed grade from art history paper.

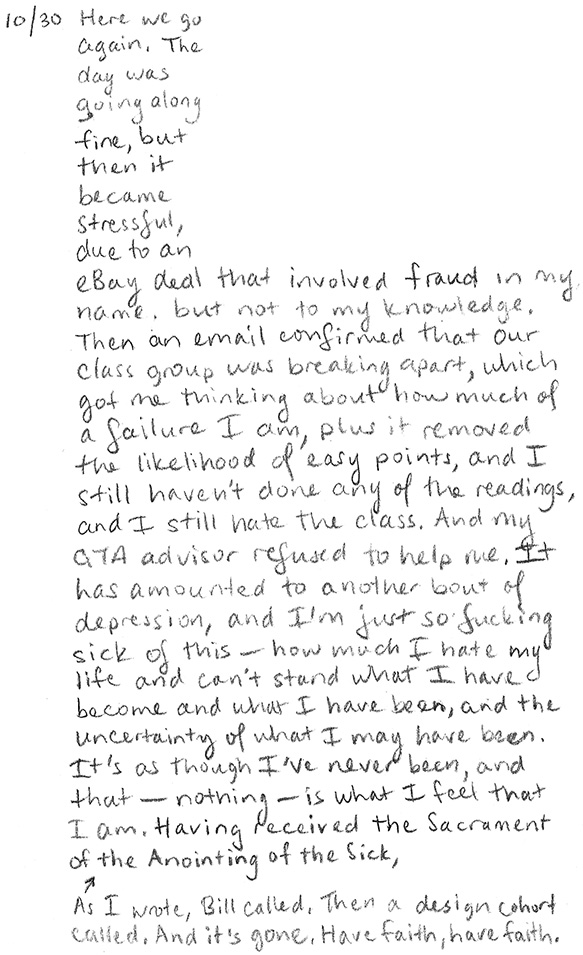

I began documenting the dark episodes in my visual journal.

Figure 4. Visual journal entry, J. Derby, 2006.

I repeatedly asked for antidepressants, but my psychiatrist was convinced that I needed to be stabilized. I was spiraling out of control, but he refused to listen. "You should become a professor of bipolar disorder," he told me, "because with bipolar it's for the rest of your life." Was this some kind of accident? An unfortunate event resulting especially from carelessness or ignorance? Was it an unexpected and medically important bodily event? Injurious? I needed a new psychiatrist, but I couldn't find one. Even OSU turned me away. I had no options.

My peers and family were worried, too. We had lengthy conversations debating my situation. I reasoned that some people are perpetually unhappy, and why should anyone have to live who doesn't want to? Maybe I should quit school and move back to Park City. Church was the answer. Church wasn't the answer. This was all my fault (Saks, 2007). But what alarmed people more than our conversations was my art. I don't know how many people saw my experimental video Disorder, but it was more than I invited. Bill loved the video and Lori got it, but my aunt panicked and she started calling me daily—hadn't she read my artist's statement?

Here is a brief synopsis of Disorder (Figure 5): The first five minutes is footage of me preparing an omelet: peppers, onions … firecrackers! It eventually explodes. The middle section reveals "disorder" through private everyday behaviors, such as hitting myself because I hate my appearance. This transitions into the end section in which I sing "Deposuit potentes" from Bach's Magnificat: "He has cast down the mighty from their thrones, and has lifted up the lowly" (International Committee on English in the Liturgy, 1975, p. 669). The camera traverses dark hallways, flashing images of a storm and an apple impaled with pills, and concludes with me floating dead in a bathtub. The video, like much of my work, attempts to transgress seriousness and crisis with untimely humor and whimsy. My artist's statement explained this, but people refused to understand.

Figures 5. Disorder (video stills), J. Derby, 2006.

2. Accidental Admissions

It was a Thursday afternoon in early November—All Souls Day, the Day of the Dead—and I had a lot to do. I had taught my morning class and was preparing to accompany an important guest speaker to lunch. After lunch, I would escort her to the award ceremony. She would deliver a speech in exchange for a prestigious award from our department. After that, I would do some homework, then go to choir rehearsal, then rush home at 9:30 to do the rest of my homework. It was going to be a long night.

A professor found me in the graduate office. She said she needed to give me money for lunch but she led me into another professor's office instead of her own. The door closed behind me, and I stood facing the two of them, side-by-side. "So what's going on, John?" I was wondering this myself. "I don't know. What do you mean?" "I heard you made a nice video in Jen's class. Someone gave me a copy of it—So, you know, I guess we're just wondering what you … how everything … maybe you haven't heard about the incident …" My memory of the conversation is fuzzy after this. I figured out what this was—a planned intervention, just like on TV. "Didn't you read my artist's statement?" I couldn't understand why this was happening, as I had been very open about my depression. "You don't have to do this—I don't need an intervention." "John, you're not the first one to go through this. We can help you get the help you need. I have connections. I know someone. You need this!" The video image of me had apparently become truer than my own words. "Okay, I'll talk to them. Let me get my stuff from the office." "Okay, but we're coming with you. We're not letting you out of our sight."

We walked together across campus to a place I'd never been. It was a strange walk—all these people, going about their business as I had just an hour earlier. Now I was being escorted like a bad child. Except I was invisible. I could feel the people not looking at me, not noticing my predicament. Did my complicity pardon me, or were they were fooled by my incredibly calm demeanor? I could control this. I wasn't going to lay down my arms and be abused. I would set the terms. I would steer the conversation. This time I would get help and it would be the right help.

We entered a building on the edge of the medical center complex, the part where tan brick medical buildings blend in with the other tan brick buildings. The intake person asked me some routine questions, the kind that are unimportant but have to be asked—name, allergies, closest relative, medication, citizenship? Toward the end of the sequence I interjected a rehearsed, calculated question: "Okay, so before we go any further, is there any way I could be locked up against my will if I talk to you guys?" No—not only don't they do this, they can't—it's against their policies. That made sense. So I finished the paperwork, had my vital signs checked, nodded, and rejoined my companion. "They have a really nice magazine collection here, don't they?" I hadn't noticed. I didn't like any of them, but I didn't have the wherewithal to critique them. "Yeah. Pretty nice," I replied. We had little in common other than a mutual fondness of cats and being overdressed for the occasion. Her senior professor attire mocked my earnest attempt at being the fashion-forward grad student everyone likes, the one I was compelled to become and may have been. How did she keep it together so well, trying so little, gardening in her spare time, chairing dissertations, enjoying her research, keeping her desk so clean? How did she have time to sit here with me, to notice the pleasantry of magazines and the urgency of my artwork, and how could she pretend that somehow the two cancelled each other out and made this unnerving engagement okay?

"John? Mr. Derby? Mr. Derby?" "Hi, right here," I said, gesturing to the nurse. "I'll be waiting right here, John," my professor assured me, "I'm not going anywhere till I find out you're being helped." And then I was led to an examining room unlike any I'd ever seen:

Figure 6. Photographs of OSU Medical Center ER examining room.

There were no medical instruments, tables, charts, or anything familiar. The walls resembled the nefarious flesh of an embalmed cadaver. And the rubber chair with a month's supply of towels. What did they think could happen in this "examination" room? The camera beamed, daring me to find out.

A resident entered and asked me predictable questions. I answered honestly, emphasizing that I was depressed, plain and simple. "Are you having suicidal ideations?" "Yes." "How often?" "Daily. No, almost daily. Maybe weekly, but more frequent in the past month. None in a couple days. Probably every couple days." "Do you have a plan?" "Yes. I know exactly how I'd do it. But I haven't put the plan in motion. I'm not the kind of person where there will be any 'attempt'—if I do it, it'll be for real." He began explaining that suicidal ideation is a serious matter demanding medical attention. It isn't something that can be ignored. There's nothing an emergency room can do, but this is something another branch of the hospital can deal with … I knew it—those fucking liars! "Whoa, whoa! You're not going to lock me up, because we already talked about that!" "Sir, we have a legal responsibility to treat you for your medical condition, and sometimes that requires hospitalization. Like I said, there's nothing we can do here, but we have a hospital that can help. I'll be back in a few minutes." "BUT YOU CAN'T! YOU DON'T HAVE THE RIGHT! I'M A FREE CITIZEN AND I HAVEN'T COMMITTED ANY CRIME!" "Mr. Derby, I have to go talk to my supervisor now. I'll be right back."

Figure 7. Self Portrait as Mental Patient, #I—296.33, J. Derby, 2006.

3. Remembered Accidents

The drugs were working. It was easy to have faith in them, because they started working just two days into my hospitalization. I only had one brief lapse of ideation, right after I got out. But I was not the same person, and it had nothing to do with the unexpected $22,000 medical bill. I had a bigger problem: a debilitating mental disability. Some of it was "side effects" of the drugs, but there was more to it. I couldn't read. I would sit for hours staring at the first page of an article, trying to read but getting nothing. I also experienced no happiness for a year, not even a second. I longed to feel "fine," the everyday mood I had taken for granted for thirteen years since my last depression.

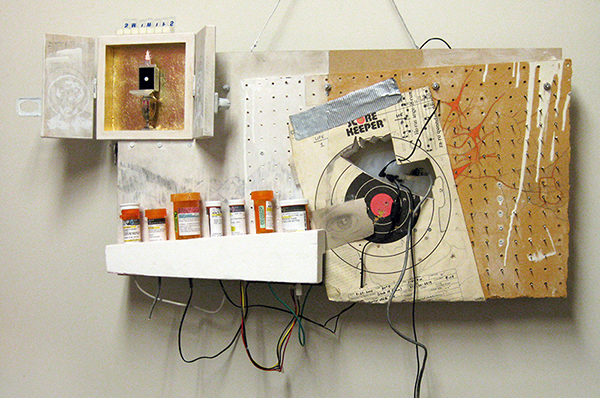

I also felt spiritually disoriented. Before my hospitalization, I had begun researching ideas to explore social, cultural, and personal aspects of religion through art. I hoped such a project could fill my spiritual void. As I researched the idea over time, however, it became clear that my faith was more of a collusion of competing forces than a creed. Psychiatry, religion, academia, art, and exercise all promised salvation as they mocked my desperation. Sacramental Psychology (Figures 8-11) emerged from the intersection of these competing discourses and their claims to solve mental disability, through psychopharmacology, Catholic Sacraments, and contemporary theory. The left side of the center panel represents the sacred ideal, while the right represents the medicalized human. The fusion of the two halves, radiated from the central self portrait outward, indicates the impossibility of compartmentalizing aspects of my identity.

Figure 8. Sacramental Psychology (center panel), J. Derby, 2006-2010.

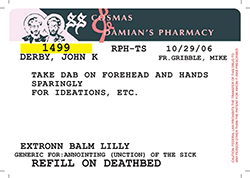

The fictitious labels (Figure 9) of the seven pill bottles indicate sacramental prescriptions, reflecting subjective meanings of theology, cultural relevance, and personal experience. Each bottle contains a symbolic artifact, some of which are personal and mysterious to viewers, others of which are common symbols like a dried rose (Figure 10). These "fake" pill bottles explore my hope and skepticism about pills, Sacraments, and academic theory, all of which are mediated through language.

Figure 9. Sacramental Psychology (detail, center panel).

Figure 10. Sacramental Psychology (detail, center panel).

The message of my pill labels, the neurological impact of the pills, placebo and reverse placebo effects, and the ways in which these are filtered through medical, academic, and religious discourses all factor into my treatment decisions and ultimately my quality of life. The use of wires connecting the pill bottles to my silicone brain allude to a problematic conduit, challenging the metaphor of the brain as a container (Danforth, 2007)—a reliquary of memories, affect, and self—while suggesting that my brain is literally a pharmaceutical container, a "brain on drugs" for better and for worse. I was convinced that Foucault's (1965/1988) critique of psychiatry for its religious, magical underpinnings remained valid in this age where chemical intervention has supplanted psychotherapy, yet I wondered if these competing "treatments" were compatible. Was Foucault helping me? Was art?

The reliquary aspect of the pill bottles is exemplified in the upper left tabernacle which contains an object resembling a monstrance (Figure 11), a religious vessel in which the Blessed Sacrament is publicly displayed for adoration in the event of Exposition. In place of the Sacrament is a Wellbutrin® pill, housed in a receptacle that represents a ring box, fashioned from a pill dispenser. As the Eucharist, or "communion" is offered as a familial gesture, the ritual of taking antidepressants evokes a sense of solidarity and faith that something more and better is just around the corner. But as an exposition, it functions more as a public announcement, not unlike the announcement Christ is supposed to make in his presence in the Blessed Sacrament: This is my body.

Figure 11. Sacramental Psychology (detail, center panel).

Figure 12. St. Dymphna, Patroness of Mental Health (left panel), J. Derby, 2009-2010.

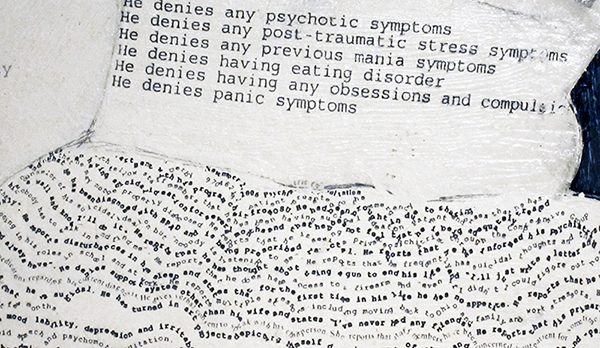

The public display of the pill bottles and monstrance challenges the idea that medicine is discreet and confidential. This is amplified in the accompanying left panel shrine, St. Dymphna, Patroness of Mental Health (Figure 12), which exposes my psychiatric history. The stripes on the dress of St. Dymphna (Figure 13)—whose likeness is an adaptation of a famous Hugh Diamond photograph representing "religious melancholy" (Gilman, 1982, p. 170)—is comprised of digitally extracted text from my medical record. Devotional candles are made from my own empty prescription bottles.

Figure 13. St. Dymphna, Patroness of Mental Health (detail, left panel).

The intimacy of these images reveals that religion and medicine are vital aspects of my personal cultural identity (Ballengee-Morris & Stuhr, 2001), the interplay of which regards (be)coming out as an ongoing process of creating connections rather than an event (Eisenhauer, 2009). Similar to my video Disorder, the Sacramental Psychology project, the right panel of which remains unmade, hasn't sorted out the loose ends of my life so much as it has knotted them together. But what more could an aspiring academic hope for: a minority identity, a story, a venue for expression, a cause? The plan was coming together perfectly—although it wasn't exactly a plan.

4. Out of the Cabinet: Accidental Accomplishments

A few things had been holding me back. The Zoloft® abated my suicidal ideations, but it caused a carnage of memory loss, apathy, and sexual problems. Perpetual slouching from my exhaustion resulted in postural deformity, which led to degenerative disc disease in my neck and a chronic sprained upper back—a problem that was perpetuated by my anxiety. Drinking away the pain wasn't helping, and it raised my body weight too high to race while diminishing my mental acuity. I had gone from overachieving to incompetent. I forgot engagements, meetings, and deadlines, and I slept through my alarm clock. No matter how hard I tried, I could not muster work, so I piled up independent study hours and took incompletes. After a year of this, Lori left me and I immediately relapsed into a severe depression. I put my suicide plan in motion. I didn't want to hurt her or my poor cats, but I was defeated. I smashed several of my paintings, returned my hundred library books, formally withdrew from Ohio State, gathered my paperwork, loaded my gun, pinpointed a remote corn field on the map, and determined a time. I was within hours of completing the plan when Lori figured it out and rescued me. Afterwards, I took a paid leave from teaching at my department's expense. I ceased duties as AGSAE co-president, dumping the work on my cohort. My teaching evaluations plummeted, and my papers were late and poorly written.

And yet, most of my superiors tolerated it. Some even seemed to understand, going out of their way to ask how I was doing and giving me more accommodations than I believed I deserved. Others remarked that I wasn't cut out for academia. Underperforming academics waste University resources, robbing deserving students of opportunities. They didn't like my personality either. I was "a completely different person" and "a cocky and arrogant jerk." Different, yes, but cocky?! I was deeply intimidated by such comments, and while I felt indignant I conceded that I wasn't worthy of oxygen, let alone doctoral funding.

Despite these challenges, my artworks and this autopathography stand as a testament to unheralded accomplishment. They triumphantly assert the truth about the Sacraments, people who believe in me, the system, love, and so on. I can argue that this essay is the pinnacle of my struggle, a compelling, important work that will absolve my ineptitude. It will never be used against me in any way. It will be cherished by Art Education and Disability Studies scholars, and anyone who receives this story will be stunned, soberly convinced. I will never have to conceal my mental disability for social or professional reasons. It won't be a problem that I've revealed aspects of my disability that are routinely used to criminalize or stereotype people. The risk of publishing this before earning tenure won't hurt—if anything, it will help!

I want to believe this, really. I want to finish with a fanfare. I am back in good health and my heart is full of joy. Nothing can stop me. Just like they say, these things always work themselves out—always. I love writing again, and it's easy like it used to be. The pain is gone, along with the sleep problem. I am confident about myself and my work. Anxiety doesn't prevent me from writing hours on end, or months. All my ambitions are about to come true. I will find a way to race again and I will win. It won't be easy because I will be busy making significant contributions to two or more fields, but winners perform under pressure. You will know me and you will like my research. I will edit journals and chair dissertations that will change the world. At the end of my career, I will give a big speech to an engaged audience of the biggest stars in my field—my friends—and I will recount this story; naturally, tears will flow and there will be a standing ovation and I will receive a plaque to add to my collection, better than my doctorate and all of my trivial race trophies. I will mention this because it is a fitting analogy: I almost went pro ….

Figure 14. Photograph of personal trophy shrine.

References

- Ballengee-Morris, C., & Stuhr, P. L. (2001). Multicultural art and visual cultural education in a changing world. Art Education, 54(4), 6-13.

- Bochner, A. P., & Ellis, C. (Eds.). (2002). Ethnographically speaking. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Boyd, J. E., Katz, E. P., Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2010). The relationship of multiple aspects of stigma and personal contact with someone hospitalized for mental illness, in a nationally representative sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45, 1063-1070. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0147-9

- Brueggemann, B. J. (2009). Deaf subjects: Between identities and places. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Clark, H. (2007). Invisible disorder: Passing as an academic. In K. R. Myers (Ed.), Illness in the academy: A collection of pathographies by academics (pp. 123-130). West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press.

- Couser, G. T. (1997). Recovering bodies: Illness, disability, and life-writing. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Corrigan, P. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59, 614-625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

- Corrigan, P. W., & Penn, D. L. (1999). Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychologist, 54, 765-776. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.765

- Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9, 35-53. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.1.35

- Danforth, S. (2007). Disability as metaphor: Examining the conceptual framing of emotional behavioral disorder in American public education. Educational Studies, 42, 8-27. doi: 10.1080/00131940701399601

- Derby, J. (2012). Art Education and Disability Studies. Disability Studies Quarterly, 32(1).

- Donaldson, E. J. (2002). The corpus of the madwoman: Toward a feminist disability studies theory of embodiment and mental illness. National Women's Studies Association Journal, 14(3), 99-119.

- Eisenhauer, J. (2009). Admission: Madness and (be)coming out within and through spaces of confinement. Disability Studies Quarterly, 29(3).

- Eisenhauer, J. (2010a). "Bipolar makes me a bad mother:"A performative dialogue about representations of motherhood. Visual Culture and Gender, 5. Retrieved from http://vcg.emitto.net/

- Eisenhauer, J. (2010b). Writing Dora: Creating community through autobiographical zines about mental illness. Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education, 28, 25-38.

- Foucault, M. (1988). Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason (Vintage Books Edition). New York: Random House. (Original work published 1965)

- Foucault, M. (1995). Madness, the absence of work (P. Stastny & D. Şengel, Trans.). Critical Inquiry, 21, 290-298. (Original work published 1964)

- Gilman, S. (1982). Seeing the insane. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hinshaw, S. P. (2007). The mark of shame: Stigma of mental illness and an agenda for change. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- International Committee on English in the Liturgy. (1975). [Evening Prayer] Gospel Canticle. English translation of the Liturgy of the Hours (Vol. I). New York, NY: Catholic Book Publishing Company.

- Jamison, K. R. (1996). An unquiet mind: A memoir of moods and madness (First Vintage Books Edition). New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Johnston, K. (2008). Performing depression: The workman theatre project and the making of Joy. A musical. About depression. Text and Performance Quarterly, 28, 206-224. doi: 10.1080/10462930701754473

- Kuppers, P. (2003). Disability and contemporary performance: Bodies on edge. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kuppers, P. (2007). The scar of visibility: Medical performances and contemporary art. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kuppers, P. (2008). Dancing autism: The curious incident of the dog in the nighttime and Bedlam. Text and Performance Quarterly, 28, 192-205. doi: 10.1080/10462930701754465

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363-385.

- Livingston, J. D., & Boyd, J. E. (2010). Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 2150-2161. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030

- Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary (2012). Accident. Retrieved January 29, 2012, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/accident

- Nicki, A. (2001). The abused mind: Feminist theory, psychiatric disability, and trauma. Hypatia, 16(4), 80-104.

- Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., Stueve, A., & Pescosolido, B. A. (2000). Public conceptions of mental illness in 1950 and 1996: What is mental illness and is it to be feared? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 188-207.

- Picart, C. J. S. (2002). Living the hyphenated edge: Autoethnography, hybridity, and aesthetics. In A. P. Bochner & C. Ellis (Eds.), Ethnographically speaking: Autoethnography, literature, and aesthetics (pp. 258-273). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Price, M. (2011). Mad at school: Rhetorics of mental disability and academic life. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Roman, L. G. (2009). Thunderous ode. Review of Disability Studies, 5(1), 34-35.

- Saks, E. R. (2007). The center cannot hold. New York, NY: Hyperion Books.

- Scott-Hoy, K. (2002). The visitor: Juggling life in the grip of the text. In A. P. Bochner & C. Ellis (Eds.), Ethnographically speaking: Autoethnography, literature, and aesthetics (pp. 274-295). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Siebers, T. (2008). Disability theory. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Wahl, O. F. (1995). Media madness: Public images of mental illness. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Wahl, O. F. (1999). Telling is risky business: Mental health consumers confront stigma. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

John Derby is Assistant Professor at the University of Kansas. He earned his PhD in Art Education with a Graduate Interdisciplinary Specialization in Disability Studies from The Ohio State University, MA from Brigham Young University, and BS and BFA degrees from Bowling Green State University. He teaches graduate and undergraduate Visual Art Education courses, and his research interests include disability studies, contemporary art practices, visual culture, and Foucault. He has published in such journals as Studies in Art Education and Disability Studies Quarterly.