The award-winning musical Next to Normal is widely lauded for addressing the stigma of mental illness. However, the play uses a medical model of psychosocial disability in a way that narrows and sanitizes the representation of people who have such disabilities. Analyzing Next to Normal's performances, critical reviews, artist commentary, and audience reactions, this article argues that the musical fails to remove stigma associated with people with psychosocial disabilities and overlooks an ecological perspective that would better honor their experiences.

Much theater unwittingly stigmatizes people with psychosocial disabilities. 1 Oppressive tropes of madness as metaphor and archetype are ubiquitous in American theater because they are useful. Such tropes efficiently perform a kind of shorthand: they strengthen narrative or clarify character in ways that have little or nothing to do with the actual individual, social, and political experiences of people who live with psychosocial disabilities. At the same time they universalize what are in actuality diverse and multifarious experiences. Rather than illuminate, educate, and explore, such tropes invalidate, infantilize, and misinform. David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder argue that this cultural representation has a very real impact in the world that influences how people view themselves and behave toward others. 2 For those among us labeled or associated with mental illness, stigmatization can result in emotional and psychological distress and social exclusion. It creates barriers to education, employment, housing, social services, healthcare and other entitlements, legal protection, and political advocacy. 3

If theater has the power to negatively influence attitudes about people with psychosocial disabilities, can it do the opposite as well? Librettist Brian Yorkey and composer Tom Kitts think it can. They created the widely successful Broadway musical Next to Normal partly because they wished to raise awareness about people with these disabilities. Yorkey has said that exposing the stigma associated with mental illness was a main catalyst in creating the show. 4 The play's reviewers often state that the show exposes the truth of mental illness. Lawrence Toppman lauded Next to Normal as "brutally honest," 5 and Tony Brown called it an "unblinking look at mental illness." 6 Critic Misha Barton feels that it "attempts to paint an authentic picture," adding "it's about time." 7 After receiving positive feedback from many fans, lead actor Alice Ripley commented, "I think we are performing a public service!" 8

Unfortunately, the play's depiction does something other than show straightforward facts about psychosocial disability, and its relationship to stigma is much more complex. Victoria Ann Lewis observes that theater that attempts to move beyond stigmatizing representations of the disabled person never truly transcends or overcomes such conventions. 9 This is particularly true of how we represent our notions and experiences of madness. Theater that wishes to critique society's oppressive attitudes toward psychosocial disability must contend with the authoritative language and practices of psychiatry. These include cultural values, assumptions, knowledge, and institutional structures that impact disability yet remain problematically ignored or under-discussed.

Next to Normal is one of the first major theater productions in the United States to present madness through a contemporary biomedical model. Millions of Americans intimately experience this model when they use psychiatric medication or receive other mental health services, but these experiences are generally not openly discussed. Next to Normal brings some of these "shameful," underrepresented experiences into the light, and therefore can be seen as a positive step forward for representation of people with psychosocial disabilities. For example, many audience members have welcomed the musical's acknowledgment of their own frustration with taking psychotropic medication and psychiatry's incomplete understanding and treatment options.

When critics describe the show as "brutally honest" and "unblinking" they seem to be specifically referring to how the musical uses the medical model's putative objective representation of mental illness to resist false stereotypes and therefore combat stigma. However, the same audience feedback that welcomes Next to Normal's "enlightened" representation also reveals severe concerns with this medical model. For example, despite Yorkey and Kitts' attempts to remove stereotypes, the show's medical perspective does little to reduce the stigma associated with mental illness. Additionally, by representing psychosocial disability through an "objective" medical narrative, the musical elides psychiatry's potential to oppress its patients and exacerbate their distress. Finally, the show's strategies to elicit audience empathy for people with psychosocial disabilities emphasize society's normative values, which include an ideology of ability that marginalizes some of us. This marginalization is revealed on stage by a narrative, characters, and images that ignore significant socioeconomic and cultural factors that greatly impact experiences of psychosocial disability.

An analysis of Next to Normal and its attempts to destigmatize mental illness clarifies the social construction of psychosocial disability and emphasizes the deep-rooted challenges we face when attempting to rewrite oppressive representations of and reactions to madness. Having garnered significant attention, the musical can be used as a starting point to address concerns that are well understood by people with psychosocial disabilities but are all too often missed or under-discussed by the majority in society who continue to rely on a medical model to understand and respond to psychological and emotional difference and distress. By noting what the musical fails to show, this article outlines how cultural representations can acknowledge more aspects of psychosocial disability in ways that would lead us as a society to provide better support for each other.

Next to Normal, San Francisco, February 10, 2011

It's 9 p.m. and I'm sitting in a Starbucks café in the Tenderloin District of downtown San Francisco. Across the street in the elegant Curran Theater, the Pulitzer Prize—and Tony Award—winning Broadway musical Next to Normal is in the middle of the first act. 10 I've been coming down here to interview audience members for the past week. Before each performance begins I approach people outside on the sidewalk and ask them what they have heard about the show and why they chose to come. I keep the questions open-ended, but I really hope that they mention mental illness. I want to know if this specific theme interests them. What preconceptions or experience do they have with mental illness? Do they hope to see anything specific tonight? I then invite them to come back out after the first act and share their first impressions with me.

It's now almost time for intermission. Before the show, the sidewalk was alive with a large crowd of well-dressed people standing under the twinkling lights of the marquis, laughing, smoking, and talking on their cell phones. Now the street is almost empty. Everything is quiet and the energy has changed. The few pedestrians who remain stand still or walk alone, often changing direction. Many are dressed in dirty, ill-fitting, or incomplete clothing. The street is no longer a place where people pass through or gather before entering the warm, brightly lit theater. It is a destination in itself.

One older man stands near the wall of the theater, hunched over his cane. I recognize him as a former client from the days when I worked as a psychiatric social worker. With baggy pants five sizes too big and a wild ring of hair around his bald crown, he looks like a caricature of Jack Nicholson without the fiery twinkle in his eye. He stands there scowling and muttering to himself. When I knew him, he lived alone in a squalid single-occupancy-rate hotel and would not leave his tiny room for weeks on end. He had no family or friends, so I would check in with him every day. He wouldn't bathe or brush his teeth and had that familiar and specific street-homeless smell, a pungent mixture that is both acrid and sweet. His flattened expression and disorganized speech were always a little unsettling. Whether it was because of the side effects of strong medication, a disorganized thought process, or his personal distress, he never specifically asked me how I was doing. One time, however, when I mentioned that I participated in theater, he seized upon this and began telling me how much he loved theater. From that time, he would talk to me about various actors or shows from years past, even though he no longer had the resources to attend performances. I have now seen him down here several nights in a row. Perhaps he is in the habit of standing next to the theater just to be close to it.

Inside the theater, an actress is portraying an upper-middle-class, white suburban mother named Diana who has a psychiatric diagnosis of bipolar disorder. 11 Alice Ripley, who originally played the role of Diana on Broadway, offers a normative beauty that is, as one critic notes, "the very image of an attractive mother on a TV drama." 12 Diana lives in a beautiful house with a loving husband and daughter, and at first glance it would appear that she has no troubles to speak of. And yet something is very wrong. The musical tells the story of her struggles with psychiatric symptoms and the powerful side effects of medication that leave her feeling empty inside. Sometime during the first act, Diana decides the meds aren't worth the side effects. With soft piano and cello music playing in the background, she slowly sinks to her knees and looks off into the distance. She begins singing with sorrow and longing about the pre-medication days when she felt alive. Soon, an upbeat acoustic guitar tempo joins in and a spark comes into her eyes as she remembers the highs and lows of her past extreme feelings.

Back outside the theater, my gaze rests on my former client, who continues to stand alone, mute, on the sidewalk. As his former therapist, I cannot ethically approach him in public uninvited. But I would have liked to have known what he would have thought about the show going on inside. How much would he or the others walking around the street that night have identified with the way Diana's disability is represented in the play? If there is a significant difference between the story unfolding in the theater and the lives of those who were outside that night, what is it? If Next to Normal's version of mental illness doesn't adequately represent real lived experience, why did its creators choose it? What does this sanitized version offer? And what does it neglect?

Next to Normal clearly offers something that is welcomed by some theater critics and advocates of people with psychosocial disabilities. The Pulitzer Prize Board called the show "a powerful rock musical that grapples with mental illness in a suburban family and expands the scope of subject matter for musicals." 13 Affiliates of the influential nonprofit advocacy group National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) have co-sponsored awareness nights in conjunction with performances of the play. 14 Nancy Tobin, the executive editor of NAMI's magazine bp, claims that the show has become "a powerful ally in educating audiences." 15 Facebook fan pages and other website forums have popped up where audience members share enthusiastic responses and talk about how the show mirrors some of their own experiences. 16 It appears that Next to Normal has become a poster child for mental health advocacy and a rallying point for those who wish to fight stigma and oppression. As librettist and lyricist Brian Yorkey states, "Exposing the stigma of mental illness is one of the reasons [composer Tom Kitt and I] wrote the show, why we pursued telling this story. We both feel that an awful lot of people try to live up to a standard of what they consider 'normal' and that actually can be as destructive as anything." 17 The key word here is "normal." Yorkey suggests that normal is a concept that separates some individuals from others and can harm those who are unable to meet its standards. He thus echoes the basic argument of disability studies that society constructs an impossible, unnatural standard of what is normal that alienates and disenfranchises people who cannot meet that standard. But how does Next to Normal represent this concept of "normal?" And what does the "next to" signify?

Various audience members have individually thanked Yorkey, Kitts, and Ripley, saying that they felt the musical told their personal story. 18 This identification should not be disregarded. Yet in light of the individuals I observed outside the theater that night, I am compelled to ask who is actually being represented on stage and how fully the show represents them. Though the musical attempts to destigmatize psychosocial disability and champion understanding and support for individuals with such disability, the musical ignores how economic, institutional, political, and social factors interact to affect the status and well-being of such individuals. Through its simultaneous rejection and use of the concept "normal," this well-meaning yet very narrow representation actually reinscribes ableist and normative ideologies that go unquestioned in our larger society.

In an effort to reduce the stigma of its subject, Next to Normal reduces psychosocial disability to mental illness, a biological condition located within the individual. The musical fully embraces this medical model in an effort to eliminate moral judgments about people who contend with psychosocial disability. Modern medicine states that we all have biological bodies that are prone to illness; anyone can become sick regardless of his or her moral values and choices. In this respect, the medical model "normalizes" emotions, thoughts, and behaviors that are considered deviant. However, because this model foregrounds individual pathology, it obscures social factors that partially construct psychosocial disability. This limits the possibility that society will more fully accept and support those who are labeled mentally ill. One social factor the musical ignores is psychiatry itself. Because Next to Normal embraces a medical model of mental illness, it represents psychiatry as an objective institution, and it thus fails to address how clinical language and practices can add to the distress of those labeled with psychosocial disorders.

Equally troubling is Next to Normal's strategy for engendering empathy in the audience. It presents a very "normal"-looking and -behaving protagonist who avoids most of the stigmatizing aspects of psychosocial disability. By sidestepping issues that construct social identity such as class and race or individual expressions of psychosocial disability such as a deviant personal appearance and behavior that is tied to stigma, Next to Normal reinforces the limits of U.S. society's acceptance of those who deviate from the norm. Perhaps the creators sought to make it possible to broach a taboo subject by channeling representations of disability into characters who were relatable for the audience. But their adherence to a packaged, sellable representation implicitly encourages the audience to focus on a narrow medical model that doesn't consider the factors that continue to oppress and create distress within those who contend with psychological and emotional difference.

In interviews, librettist Brian Yorkey and composer Tom Kitt frequently use terms related to pathology. For example, Brian Yorker told an interviewer that

more families are touched by mental illness than we know—depression, bipolar, and anxiety. For [the] most part, people don't tend to share that. I think we realized that and that's what we wanted to show. An illness like that thrives in the dark, and light may not kill it, but it certainly helps to start the healing. 19

This language clearly frames psychological and emotional difference as sickness, and it conjures madness as a threatening entity that thrives and grows through neglect and ignorance and that must be destroyed by bringing it out into the enlightened gaze of "normal" members of society. To bring it out into the light is to openly name it as an illness that must be eradicated.

The musical begins by introducing a seemingly "perfect, loving family" 20 that is haunted by the spectre of pathology. In a hypomanic episode, the mother finds herself on the floor, caught up in a frenetic enthusiasm for making sandwiches and claiming that the room is spinning. Her daughter Natalie is practicing the piano, singing that although "Mozart was crazy, flat-fucking crazy," his music was "not-crazy" but balanced and nimble. If only she can obtain an early admission to college, she will escape the similar "disease" in her family, she sings. The husband, meanwhile, questions his own sanity in his spousal relationship: "Who's crazy? The one who sees doctors or the one who just waits in the car?" The protagonist wife and mother is then definitively introduced to the audience by her psychiatrist, Dr. Fine: "Goodman, Diana. Bipolar depressive with delusional episodes. Sixteen-year history of medication." 21 Through this medical interpellation, all previous representations, narratives, and experiences of Diana are corralled and flattened into the purview of psychiatry. In contrast to disability activism's demand for people-first language, her doctor reduces Diana to her diagnosis; she is a bipolar depressive with delusional episodes. This medical framing is never questioned in the world of the play. This is because diagnosis-first language is the acceptable, standard discourse in our society. Consider, for example, a recent New York Times headline that reduces an individual to his diagnosis by linking psychosocial disability with medical language and violence: "A Schizophrenic, A Slain Worker, Troubling Questions." 22

A critical approach to language is central to disability studies. Deemphasizing individual biological impairment, disability studies concentrates on the social construction of disability: the ways that society perceives and responds to and therefore constructs disability. This theoretical move to a social model of disability has increased understanding, acceptance, and accommodation of people with physical differences. Mainstream institutions are developing more inclusive practices, often spurred by legislation such as the Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (1973) and the American with Disabilities Act (1990). Despite these gains, fewer advances have been made in terms of responses to psychological and emotional difference, which are still primarily understood as medical problems that require a medical solution. In fact, with advancements in neurobiology and psychopharmacology, the model that sees disability that stems from psychological and emotional difference as a biological flaw has strengthened in the past two decades. 23 The term "mental illness" pathologizes nonnormative thought, feelings, and behavior and insists that they be diagnosed and cured. Michel Foucault argues that modern western society has given psychiatry the sole authority to explain and treat these "pathological" differences. 24 Because the psychiatric model identifies distress and difference as primarily an individual medical impairment that requires an individual solution, people often ignore or deprioritize many other factors and frameworks that construct the "problem," such as, socioeconomic and political conditions, and the power dynamics within the sphere of psychiatric treatment. It is true that psychiatric diagnosis and treatment plans often include at least some room for addressing the patient's social needs and concerns, but psychopharmacology and other treatment that targets the biochemical thought process of the individual remains the first line of treatment, and often it is the only treatment. This view is performed in Dr. Fine's treatment of Diana. The benefits that would derive from working to change society's response to mental illness are absent from the treatment plan, mainly because for Dr. Fine, Diana's condition has nothing to do with society.

The framing of Diana's problem in Next to Normal is well intentioned. Unlike narratives of madness that dwell on creative genius or spiritual affiliations with otherworldly forces, modern medicine is egalitarian in that every biological body is susceptible to sickness. The creators of the musical present Diana as a relatable person and not as an outlier in the human condition. Rejecting a romantic notion of madness, Yorkey reports, "There were people who suggested that we make Diana an artist, a creative person, but we chose to make her an ordinary woman. Not everybody who becomes a great artist has this disorder and not everybody who has bipolar is creative." 25 But Diana isn't just ordinary. She is exemplary and possesses a beauty of the type that is often used to sell detergent on television. She is a "sexy and sharp," middle-class, educated, suburban mom in her thirties or forties. Both actors cast in the Broadway role have been white with blue eyes and dark blond or red hair. Furthermore, this physical beauty and ability does not stop with the mother. She has a "handsome," loving, and devoted husband and a talented (albeit stressed out) teenage daughter.

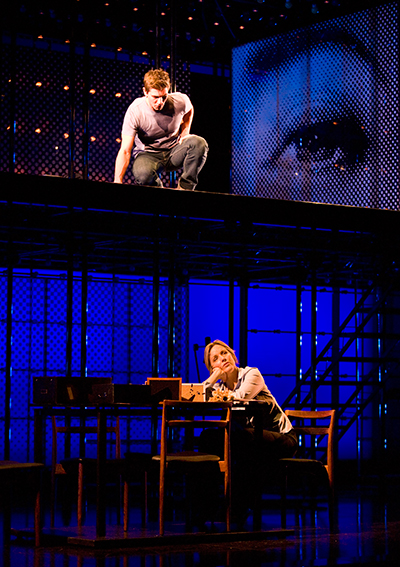

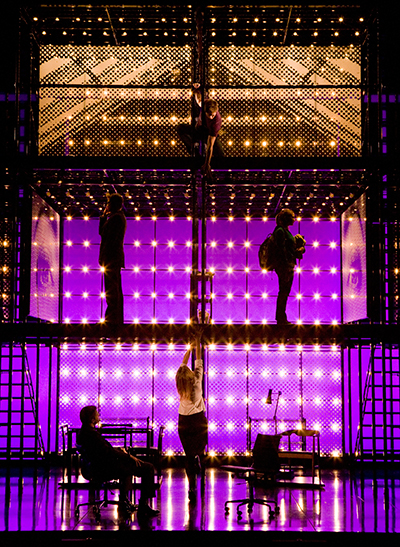

The family's social standing also suggests that they are models of normalcy. The abstract scaffolding set that depicts their self-designed, three-level home gleams with steel, brilliant colors, and an industrial shine that suggests an antiseptic cleanliness. This sterility suggests a clinical space free of any external factors that might contribute to madness. Any illness present in this story, therefore, cannot possibly come from the environment. In fact, the environment has little significance at all beyond functioning as a mirror of Diana's mind, which suggests that all the vital aspects of Diana's madness lie behind her two eyes, which are literally printed on the second-story windows. In fact, the entire house is a pictorial and metaphorical representation of her head. The upstairs attic of her unconscious is inhabited by a hallucinatory version of her dead son and a chorus of voices that sings about how medications are interacting with her brain. The live band that provides the amplified music of her moods is located in the darker recesses of the theater and of her mind. The spectacle of bright lights that floods the cyclorama, pillars, and floor of the set are always the consequence and literal reflection of Diana's internal feelings, not her social world. When she feels depressed, a deep blue pervades the space (see Figure 1). When she is manic, electric lights flash, casting gold and white across the set (see Figure 2). When she attempts to kill herself, red light pools across the floor and walls like blood emanating from her body/mind, the true source of her pain. The relationship between Diana's internal state and the external environment is thus a one-way street, suggesting her madness stems not from an ecological relationship between the individual and her world, but solely from her within her body, in her psyche, her neurochemistry, and her genetic predisposition.

Figure 1. After electroconvulsive therapy, Diana (Alice Ripley) continues to feel empty and sad but no longer knows the reason why because the memory of her son (Curt Hansen) has been erased. © 2012 Craig Schwartz Photography

Figure 2. In her psychiatrist's (Jeremy Kushnier) office, Diana (Alice Ripley) experiences a thrilling, manic delusion and hallucinates that her son (Curt Hansen) is alive. © 2012 Craig Schwartz Photography

In keeping with society's acceptance of psychiatry as the main arbiter of and solution to madness, Yorkey and Kitts state that they are opposed to a strictly political antipsychiatry message: "We were not interested in setting up a straw man of a doctor who was part of the problem. The story that was interesting and most compelling to us was about the very competent doctors who are still struggling with finding the treatments that are right for their patients." 26 This seemingly fair-minded representation of psychiatry as doing the best it can echoes psychiatry's claim that it is an objective tool that is used to treat a biomedical condition. However, while psychiatry may be part of the solution, it is also always part of the problem: its practitioners are the very ones who exercise the power to label madness as a problem. Yorkey and Kitts are right to avoid returning to the black-or-white antipsychiatry stance of the 1970s. But Next to Normal offers no awareness of the vital role that sociological and cultural critiques have in assessing and reshaping psychiatric treatment. Bradley Lewis argues that psychiatry's claim that it has an objective position in society results in undeserved authority. By disavowing ideology, psychiatrists remove any possibility of a critique of the power and potentially harmful ideas and practices of their field. 27 As long as the problem of psychosocial disability is considered to originate solely in the individual patient's brain, psychiatry can be judged only on how well it understands and fixes that brain's illness. This is not the case; psychiatrists can do harm or exacerbate distress. Their ability to shape society's perceptions, values, and responses to psychological and emotional difference extend far beyond the clinic.

Anyone who has been associated with psychosocial disability has experiences with clinicians that present a very different picture of the field than the neutral picture its practitioners like to present. Often the relationship between individuals with emotional and mental disabilities and their clinician is very uncomfortable. This discomfort occasionally surfaces in Next to Normal in the form of a gentle critique of the power imbalance inherent in psychiatric discourse. For example, in her song "My Psychopharmacologist and I," Diana wryly notes that while her doctor knows her deepest secrets, she knows only his name. But such moments of discomfort are underdeveloped and are treated as unfortunate but necessary side effects of clinical treatment by "very competent doctors" who may not know all the answers but are certainly not part of the initial problem. The musical thus accepts psychiatry's claim to neutrality within its medical paradigm of madness. Diana cannot escape the biochemical etiology of her distress, and Next to Normal accepts psychiatry's claim that its objectivity and authority makes it impervious to theoretical and cultural critique. While psychiatry doesn't have all the answers, "it is the best we've got," Diana's therapist sings.

Next to Normal does acknowledge that psychiatry is far from perfect. In an effort to accurately depict the legitimate struggles some people go through in accepting psychiatric treatment, the story reveals that Diana's medication regime has resulted in unpleasant side effects, leaving her emotionally empty. In the song "I Miss the Mountains," Diana sings with sorrow and longing of her pre-medication days, when she felt truly alive (see Figure 3). A fire alights in her eyes as she remembers the "manic, magic days / And the dark, depressing nights." Soon the music swells, and so does her voice and resolve. Defiantly, she rushes to the bathroom and dumps her dulling medication into the toilet, belting out:

I miss the highs and lows,

All the climbing, all the falling,

All the while the wild wind blows,

Stinging you with snow

And soaking you with rain—

I miss the mountains,

I miss the pain. 28

Figure 3: Missing the wild and sharp feelings of her pre-medication days, Diana (Alice Ripley) secretly dumps her pills into the toilet. © 2012 Craig Schwartz Photography

At this point the musical offers a viewpoint similar to that of advocacy groups such as Mad Pride and The Icarus Project, which assert that such experiences have intrinsic worth, despite or even because of the pain associated with such moments. 29 Diana claims that she cannot simply dismiss her madness as an illness that should be eliminated because these "sick" feelings that psychiatry rejects constitute a positive aspect of her identity. Recalling her past as a "wild girl running free," she uses nature as a metaphor for the invigorating essence of her life. The sensations of "fire," "soaking rain," and air that "cuts … like a knife" reminded her that she was "real." 30 This viewpoint resonates with some audience members, particularly those who have a similar relationship with psychiatric medication that numbs thoughts and feelings. One young man who returned to speak with me at intermission commented:

So I think that that one song, "I Miss the Mountains," … I remembered that from that piece on NPR. That was one of the reasons I wanted to see the show. It sparked my memory, so I really wanted to come out here and tell you this. That, uh, I remembered that from the piece. Because … I mean … I was on meds. And that was how I felt. 31

The musical seems to offer a social space where normally taboo subjects can be discussed. I was surprised at the number of people who came back to speak with me in order to disclose that they, like Diana, had had personal experiences with psychiatry. An older man told me:

I was committed in [city X.] I hated it. I wanted out. Everyone was drugged out except me. It was horrible there. It was like an Edgar Allen Poe piece. The pigeons flew in. There were no windows. Just iron bars. And the pigeons would shit on us from above. (Laughs.) I know it doesn't sound real, but it is true! 32

Such positive audience identification suggests that, on some level, the musical honors the experiences of those with psychosocial disabilities. Nevertheless, its audience is ultimately instructed to toe the psychiatric party line; the narrative warns that resistance to treatment is not only unwise but ultimately untenable. After Diana defiantly discards her medications, her pill-free hypomania becomes unsustainable as she slides into suicidal thoughts and action. In fact, even Diana's short-lived rebellion of "I Miss the Mountains" is criticized by critic Chris Caggiono as an irresponsibly inaccurate depiction. He writes, "[Diana] romanticizes the highs and lows of bipolar disorder. But the truth is the 'highs' are not refreshing, they're debilitating. And the 'lows' are characterized not by wistful melancholy but by active self-loathing and destruction." 33 In his earlier review of the Off-Broadway version of the show, he argued, "Manic depression is a disease, not an alternate lifestyle… . Would Yorkey counsel diabetics to stop taking insulin because of the inconvenience? Would he suggest that heart patients forgo their nitroglycerin because it's not organic?" 34

Perhaps in response to such feedback, which urges a retreat from any anti-psychiatry message, the show was reworked before it moved to Broadway. Director Michael Greif and others successfully encouraged Yorkey and Kitt to remove the main song "Feeling Electric," which focuses on the doctor and psychiatric power of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). In the original staging, the psychiatrist sheds his surgical gown for rock star attire and sings to Diana with raw vocalization and lyrics full of hubris:

I see the word and you'll see the light …

The thunder's under my command

I hold the lightning right in my hand. 35

Yorkey and Kitt replaced the song with Diana's "Wish I Were Here," which does critique psychiatry. But the critique is more subtle and focuses on the unfortunate side effects of treatment. As Diana sings about her sense of depersonalization, her doctors remain silent, professional, and only indirectly responsible for what may be a necessary consequence of appropriate care.

I am not suggesting that madness does not sometimes result in suicide or that ECT is not an important treatment option. Rather, I wish to emphasize that Next to Normal encourages the audience to understand Diana only as a compilation of mental illness symptoms. The musical focuses on Diana's role as patient, and Dr. Fine's medical chart tracks this story with details of dysfunctional behavior, diagnoses, treatment regimens, and repeated relapses as Diana spirals downward into attempted suicide. With this story, what do we really learn about her? Along with her individual symptoms, she ultimately fails as a housewife and mother and seems to possess no outside interests or friends. Although some will argue that Diana's journey realistically mirrors that of many psychiatric patients, the musical's storytelling privileges her failures and pain to a degree that erases other potentially valuable and rich facets of her life. This approach clearly is not in line with the demand of disability advocates for "people first" representation.

A richer understanding of psychosocial disability is offered by The Icarus Project, a network of local chapters throughout the United States that builds community support around issues of distress and healing and creates opportunities for creativity and celebration in the forms of writing, film, live performance, sharing skills, and lectures and other social gatherings. Its mission statement offers a positive and collaborative valuation of madness:

We believe these experiences [that are often diagnosed and labeled as psychiatric conditions] are mad gifts needing cultivation and care, rather than diseases or disorders. By joining together as individuals and as a community, the intertwined threads of madness, creativity, and collaboration can inspire hope and transformation in an oppressive and damaged world. Participation in The Icarus Project helps us overcome alienation and tap into the true potential that lies between brilliance and madness. 36

Founded by people who have experienced being labeled with bipolar disorder, The Icarus Project sidesteps the binaries of the medical model and draws new conceptual maps that offer a more affirmative social space between sane and insane where "sensitivities, visions, and inspirations are not necessarily symptoms of illness" and "breakdown can be the entrance to breakthrough." 37

Instead of condemning Next to Normal's narrow representation, it is more useful to analyze why the musical frames Diana's disability only as a biological illness triggered by psychological trauma. Once the musical's strategy is understood, we can evaluate that strategy in terms of its efficacy and unintended consequences. Because Next to Normal explains socially deviant behavior as the result of neurochemical processes in the brain, it is able to dismiss the concept of madness as moral deviance and claim that mental illness is not the fault of the individual any more than diabetes is the result of poor moral choices or lack of willpower. This strategy is not without merit. Contemporary U.S. society maintains stereotypes of mental illness that are linked to immoral behavior. These stereotypes are particularly prevalent in television and film. 38 Perhaps this is why N.A.M.I. has embraced the musical as a tool to try to reduce stigma.

Psychiatry has experienced a paradigmatic shift from a psychodynamic model to one based on neurobiology within the past thirty years. This new psychiatry rejects the psyche as the ultimate cause of mental illness. Revolutionary research in genetics, neurochemistry, brain imaging, and psychopharmacology promote the belief in U.S. society that "mentally ill" individuals are not personally responsible for their condition and therefore deserve the same compassion as those stricken with cancer or diabetes. However, even though the new psychiatry has to a great extent delinked concerns of morality from the concept of mental illness, it has not removed stigma altogether. The new psychiatry has naturalized it by likening it to physical illness. This naturalization promotes an overreliance on psychiatry to conceptualize madness and treat aspects of distress that are actually caused by discrimination and other forms of social injustice. 39

Stigma theorists Bruce Link and Jo Phelan argue that once society recognizes certain thoughts, emotions, and behaviors as saliently different, those traits become attributes that may be judged as bad. People who have those thoughts, emotions, and behaviors can then be stereotyped and subjected to other forms of oppression. 40 However, it is important to recognize that attributes of mental illness are not first identified as salient and then subsequently judged as negative. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) defines "mental disorders" as clusters of symptoms (i.e., attributes). Because psychiatry deems these symptoms unacceptable, the act of diagnosing always immediately judges patients as being in a state of unacceptable deviance. Although the biochemical model suggests that the patient is not to blame, this new model labels the patient as essentially defective. Therefore, the effort to somehow separate the fundamental markers of mental illness from negative judgment while maintaining mental illness as a viable concept is the same as attempting to remove threads from a tapestry while trying to maintain the fabric's integrity.

Phelan argues that once someone is diagnosed with mental illness, it is difficult for the patient to remove that label in the future. Furthermore, the new biomedical model exacerbates the label's "stickiness." 41 Once the defect is presumed to be part of one's genetic makeup, the threat looms that it will surface at any time. First-person accounts describe how this deleterious concept follows people for decades. 42

Because it narrowly focuses on mental illness, Next to Normal inadvertently ignores the humanity and gifts of the psychosocially disabled person. And by ignoring broader social considerations, the play also ignores an ecological perspective, one that considers that a person's health is influenced by multiple factors on various registers: intrapersonal (biology and psychology), interpersonal (social and cultural), the physical environment, the community, and public policy. 43 These factors interact with one another to produce a cumulative effect. The most effective support for people with psychosocial disabilities recognizes this matrix of influences and seeks intervention that takes all of these factors into account. A fuller, ecological representation of a person with psychosocial disability would honor these experiences and possibilities.

Next to Normal presents Diana's experience with psychosocial disability as one that is limited to intrapersonal problems. Furthermore, the only interpersonal trauma she has experienced happened seventeen years earlier when her infant son died. This framing of the character presents her true problem as a biological propensity toward bipolar disorder. During her initial psychotherapy session (which she seems to able to afford with no difficulty), she shares with her therapist, "When I was young, my mother called me 'high spirited.' She would know. She was so high-spirited they banned her from the PTA." 44 Doctor Madden responds, "Sometimes there's a predisposition to illness, but actual onset is only triggered by some … traumatic event." The performance thus suggests that the ingredients of Diana's madness are genetic, inherited from her mother who experienced her own dysfunctional "high spirits." By controlling for all other possible causes of her distress, Next to Normal presents a mentally ill patient who is in distress only because of her biological makeup. Even the traumatic death of her son is eliminated as the ultimate source of her dysfunction. Diana's husband, who also experienced the trauma, is able to remain functional (although psychologically repressed) because he does not have the biological propensity toward mental illness.

The musical goes even further in narrowing its depiction of disability. Unlike my former client who stood outside the theater, Diana's symptoms appear quite palatable, a strategy that elicits identification and therefore hopefully empathy and concern from audience members. However, in this effort to encourage identification, the musical renders Diana … well … "normal." Her manic behavior is limited to energetically making too many sandwiches on the kitchen floor. Even this deviant behavior is tempered by the fact that upon seeing her husband's concern, she immediately recognizes what she is doing and states with chagrin that is simultaneously assertive and funny, "I just wanted to get ahead on the lunches." 45 The play always narrates Diana's other deviant or dysfunctional behavior in the past tense so that in the present she can agree in a rational manner that such behavior wasn't acceptable. As she looks at family photos with her daughter, Natalie, who describes some of her mother's past behavior (e.g., jumping in the pool during Natalie's swim meet at school), Diana turns to Natalie and sings, "Your life has kind of sucked, I think." 46 Natalie complains about her mother's deviant behavior throughout the show and eventually mirrors Diana's dysfunction with her own drug abuse. Yet the audience rarely sees Diana's dysfunctional behavior directly. Aside from overenthusiastic sandwich-making, her inappropriate behavior in the present is limited to benign symptoms such as baking a birthday cake for her dead son or feeling sexually attracted to her therapist, who, in Diana's delusional mind, appears to sporadically jump up amid flashing lights during a guitar riff and sing sexually suggestive lyrics to her. But even this inappropriate feeling toward Dr. Madden is tempered by the fact only she and the audience notice her hallucinations. After these libidinal acts, the doctor sits back down as if nothing happened. As Diana discusses the side effects of her medication with him, she simultaneously struggles with her "tingly" response to his sexual dynamism. She states, "I sweat profusely for no reason. Fortunately, I have absolutely no desire for sex [with my husband]. Although whether that's the medicine or the marriage is anyone's guess."

"I'm sure it's the medicine," Dr. Madden replies in a professional, reassuring manner.

Wrongly interpreting his reply as expressing sexual interest in her, she smiles and says, "Oh thank you, that's very sweet." With a meaningful look, she then adds, "But my husband's waiting in the car." 47

The audience consistently laughs at this moment, but the psychiatrist shows no recognition of her feelings. Instead, he only pauses in a momentary confusion that is quickly dismissed. He doesn't comment about or discipline her for what normally would be labelled "erotic transference." The result of this is that Diana's "inappropriate" behavior is presented to the audience as trite, nonthreatening, and without impact. Even for herself, apparently, her desire has no negative or positive consequences. It's just there as a symptom for only the audience to note. What is missing in this exchange is what would typically happen in a therapeutic relationship: the clinician would label such feelings as "not real" and pathological and the patient would feel rejection when told that it is inappropriate to have such feelings for an officially disinterested authority figure. Of course, such a dismissal would have an even greater impact if the patient had no significant other or outside social support and therefore had reached toward the clinical relationship as his or her only intimate interaction with another human being. Diana, who has a loving husband and an oblivious clinician, avoids this difficulty from both ends.

Diana's most extreme experiences take the form of hallucinations of her dead son, Gabe, whom she sees as the teenager he never became. But because the audience also sees Gabe and because what they see is an attractive young actor singing and behaving in a more or less normal way, 48 even Diana's hallucinations appear acceptable. In fact, the first plot twist consists of the audience's discovery that her teenage son only exists in her mind. The blocking and dialogue at the beginning of the show is such that Gabe's lines and actions fit neatly in with rest of the family's interactions, as if the husband and daughter are aware of him. Only with the birthday scene, during which the mother lovingly brings out a cake with flickering candles, is her delusion revealed. Again, the consequences of this deviant behavior are within normal limits. Natalie swears and childishly stomps off stage (perhaps marking herself as a little dysfunctional because she cannot empathize with her Mom or show understanding). Her husband whispers a song of gentle, loving support to her, "He's Not Here."

Diana's normative appearance and behavior contrasts markedly with many people's experience of psychosocial disability. They often find it challenging to present themselves in a way that others deem acceptable. Their facial expressions may appear flattened. They may have difficulty dressing in certain ways or may no longer share society's norms about how often to bathe. They may find it impossible to relate to others in a way that meets society's demands. Indeed, their "deviant" performances of self in everyday life often mark madness in the first place, leading to stigmatization that creates alienation, discrimination, and the absence of support. The DSM often emphasizes disorganized speech, grossly disorganized behavior, a flattened affect, decreased verbal communication, and an inability to maintain personal hygiene as symptoms that signal mental illness and lead to a specific diagnosis. Diana exhibits none of these stigmatizing traits. Rather, her extreme feelings are represented through a "surging tidal score" and Alice Ripley's virtuosic voice, which "capture[s] every glimmer in Diana's kaleidoscope of feelings. Anger, yearning, sorrow, guilt and the memory of what must have been love seem to coexist in every note she sings." 49 Diana always dresses nicely and speaks with clarity and intelligence. One critic notes, "One reason we like Diana so much and feel for her is that she never tries to hurt anybody or act indulgently, she remains the innocent and confused victim who only tries to hurt herself to escape. I would dare say real bipolar sufferers get much scarier." 50 Even Diana's suicide attempt is a sweet, haunting moment with her son, a moment that is bathed in gorgeous stage light. Dressed in a white dinner jacket, Gabe slowly dances with her and beckons her to go with him to another world, "a place we can go where the pain will go away." Promising her "there's a world where we can be free," he leads her off stage. The depiction of the suicide attempt is limited to the psychiatrist's authoritative spoken words, which are inserted between the lyrics and sanitized with clinical language: "Goodman, Diana. Discovered unconscious at home. Multiple razor wounds to wrists and forearms. Self-inflicted. Saline rinse, sutures and gauze. IV antibiotics. Isolated, sedated and restrained. Damn it … ECT is indicated." 51

One can critique Next to Normal's sanitized representation of Diana's psychosocial disability as inaccurate. The musical's lack of abjecting language, images, and smells strips madness of its power to remind us of the consequences of society's standards of normalcy and structural inadequacies. But would a grittier, more realistic account be better? Popular culture typically makes sense of contemporary madness through sensationalized and negative traits that seem inherently stigmatizing. Most of us rely on these symptoms to describe psychosocial disability. Consider the problems with how I described my former client outside the theater. In order to emphasize his psychosocial disability, I described him in ways that are associated with stigma: poor hygiene, flat affect, an inability to empathize with me. I suggested that there is a specific "street-homeless" smell, which although it is the result of the actions of society (i.e., the failure of society to care for some of its citizens) connotes a choice made by the individual who fails to bathe. Doesn't this more "honest" description further stigmatize my former client? It might. But the main problem is not that I used abjecting language. My mistake was that I didn't go further to represent his personal experience. As his former clinician, I kept my clinical distance and adhered to an ethical code that I must not approach him on the street. But what if I had interviewed him? In fact, instead of just sticking with Next to Normal's audience members, what if I had interviewed everyone on the street that night? Why didn't I approach others who were "dressed in dirty, ill-fitting, or incomplete clothing" and experienced the street as "a destination itself"? What if I had asked them what they had heard about the play? Or what they thought about their own lives? Why didn't I invite my former client tell me why he comes down to the theater night after night? The reach of the clinic is long indeed. Even with my intention to critique Next to Normal's use of psychiatric discourse, I allowed questionable professional ethics and conventional thinking to limit my understanding and representation of my subject.

Next to Normal's sanitized characters, who are already fairly "normal," live within a narrow medical framework. In an effort to avoid stigma, the show thus uses strategies that exemplify a catch-22 people with psychosocial disabilities who wish to advocate for themselves face. In order to claim that madness is acceptable and natural, advocates often rely on perspectives about what is normal that have the effect of disempowering the very people they are advocating for. This leads to the question of whether it is possible to represent madness without including stigmatizing language and ideas. For example, would audiences even recognize psychosocial disability without relying on the concept of mental illness? In order to speak to their experience as abjected subjects, it appears that "mentally ill" people must first accept their interpellation as such. 52 Theatrical representation appears to be in the same bind. Nevertheless, my choice to not speak with my former client outside the theater that night suggests that this catch-22 isn't really the main problem.

The concept of disability appears to be forever caught within oppressive language because disability as a social construction is constituted by stigma. We therefore need to not avoid this language but somehow not let it control or limit us. The solution is not to shy away from how people already think and talk, but to exceed those narrow perceptions with many representations that include people's distress, shortcomings, and gifts: in short, representations that fully honor our humanity. My former client's "street-homeless" smell might seem like a less significant trait if we knew more about him. What did he look like as a child? Who is his family? Does he have any dreams or wishes about the theater today? His story remains untold, and this omission separates him from others.

His alienation, however, is not limited to lack of representation. Standing alone on the sidewalk, my former client performed a literal isolation that results from society's demand that people take care of themselves. Full independence is, of course, a myth for everyone. But society's ideology of ability promotes this myth. At the end of Diana's story, the plot takes a decidedly nontraditional turn for Broadway musicals when Diana chooses to leave her husband. In doing so, she follows contemporary U.S. mainstream society's paramount value of individualism:

I thought you'd like to know.

You're faithful, come what may,

But clearly I can't stay,

We'd both go mad that way—

So here I go….

A life I've never known.

I'll face the dread alone …

But I'll be free.

To catch me when I fall,

I'd never get to know the feel of solid ground at all.

Rather than argue for a community solution to madness that acknowledges interdependence as the main reality of how we live our lives, the musical suggests that we achieve self-actualization by ourselves. Furthermore, Diana claims she is doing the right thing because she is releasing her husband from her problems. Otherwise, she sings, he would also go mad. All too often, individuals with severe and persistent mental health issues do separate from their families, but for a very different reason; their deviant behavior has long since exhausted their support. When a mad person's family no longer feels able to provide support, he or she is forced to turn to a solitary life on the street with inadequate public health and social services. The musical doesn't acknowledge the absence of community involvement in "mental illness" in U.S. society. Perhaps in an effort to champion the idea of self-empowerment, the musical's lyrics state that Diana will be "free" and will experience self-actualization ("the feel of solid ground") when she tries life on her own. This view denies the need for an interdependent approach to support and disregards the painful consequences of society's demand for self-sufficiency. When Diana claims that her madness makes it impossible to stay with her family and that she must strike out on her own, she actually does not end up having to face the world alone. The audience learns that she has conveniently returned to live with her parents. But what would have happened to her if she hadn't had anyone else to turn to, as is often the case for many individuals who live with severe psychosocial disability? One needn't ask. Just go down to the Tenderloin District in San Francisco, grab a cup of coffee at Starbucks, and look out the window. The show is going on right outside.

On the night I saw my former client, I walked across the street during intermission to once again interview audience members. One older couple was generally pleased with the music and acting. One of them added that the play seemed to be pretty accurate, as she knew someone who suffered from depression. However, she thought it provided an unfair view of psychiatry:

I think that it is a little anti-medication, all of these pills that don't help her. And I'm not sure that that's accurate. I'm not sure. Maybe it is. Certainly there are practitioners out there that overmedicate people. I don't know. I do know there are a lot of people that have depression but are successfully treated by medication. I do think that sometimes it is a cheap shot. But part of this is entertainment, too. (She laughs.) 53

Perhaps for this audience member, the musical's only flaw is that psychiatry is not entirely effective in treating Diana's mental illness. The underlying assumption that psychological and emotional difference should be seen as individual pathology is invisible and unchallenged. Her comment suggests that even the musical's critique of psychiatry is offered simply to provide dramatic tension in what otherwise would be a dry realistic representation of psychiatry and a tragic illness. This acceptance of Next to Normal's "realistic" representation of psychosocial disability reveals the inherent problem with the medical model. By asserting an objective truth about "mental illness," the model erases its own contingencies, misrepresentations, and exclusions.

The woman's companion added that the first act ends on a depressing note with Diana's attempted suicide: "I hope that there is some sort of positive resolution to this thing. In real life it seldom does. So if it is just like real life, we'll be walking out of here in another hour and a half feeling just as bad as we do right now. And I'm hoping that that's not the case." 54 At first glance, this comment suggests that pleasurable theater is at odds with the goal of engaging audiences on this important social issue. But Next to Normal's representation of "real life" is quite incomplete. It may be that some audiences may respond negatively to its biomedical depiction of disability not because Diana expresses sorrow and pain but because this "realistic" portrayal of her character fails to show that her pain and struggle has any value.

Next to Normal's attempts to generate empathy with a sanitized depiction of Diana in which her "true" self is separate from her biochemical disease. But this effort ironically decreases the character's humanity and subsequently the audience's capacity to connect with her. Although Diana expresses wry humor and defiance, her story is ultimately a disabling, medical narrative of a woman who is delimited by a cluster of symptoms hung on the frame of a sanitized "normal" person. These "normal" aspects serve as reminders of what she cannot be. In the end, psychiatry fails to cure her and she must remove herself from her family in a gesture that echoes a harmful ideology of ability and individualism. This medical model deprives Diana of agency to be more than a poster child for psychiatry, a sum of unwanted symptoms.

The dehumanization of Diana's character mirrors the typical social construct of disability where people with physical, intellectual, and emotional differences are rendered as beings outside the margin of what is humanly acceptable and serve as a foil to "normal" people. As a "next to normal" subject, Diana offers the audience less humanity to appreciate, celebrate, or empathize with. In other words, the man who worried about leaving the theater feeling bad may have rejected the representation of Diana as unsatisfying because Next to Normal's full "reality" of psychosocial disability via the medical model lacks the humanity that is actually experienced by people with psychosocial disabilities. Although it may appear counter intuitive, a less comfortable but fuller depiction of Diana that includes the hardships, the grime, the quirks and imperfections, the inexplicable, the quotidian joys, and the full challenges of social injustice and knowledge gained by living through the trials and tribulations of psychosocial disability might provide more humanity for the audience to understand, empathize with, root for, and, ultimately, value. Instead of bringing us closer to those with psychosocial disabilities, the medical model keeps us at a distance.

While I was speaking with the couple, an older man with a knotted beard, long gray hair, and dirty, tattered clothes walked up to us and with a shaky voice asked for money. I smiled at him and replied, "Sorry, not today." He turned away without replying and asked someone else. I looked at the couple, and they returned my gaze without speaking. The woman gave a short, uncomfortable laugh. At that moment the lobby bell rang, signaling the beginning of the second act, and they quickly excused themselves.

Daily experiences of psychosocial disability remain so under-discussed in society that Next to Normal's elementary move toward greater inclusion of intimate experiences of mental illness is welcomed by individuals who feel that their concerns are ignored in public discourse. By depicting Diana's deprivation and struggle, the musical validates various theatergoers' personal experiences, including the young man's frustration with dulling medication and the older ex-psychiatry patient's outrage and sense of disbelief of his horrible treatment in the asylum where he was "shit on from above." Even though the play only presents Diana as "next to normal," this acknowledgement by means of partial inclusion is better than nothing at all because it at least presents psychosocial disability as an important topic for discussion. But along with providing affirmation, audience feedback also reveals unspoken and perhaps even unrecognized problems with the dominant biomedical model of madness, including the tendency to disregard integral factors of social injustice that comprise psychosocial disability. Next to Normal's problematic representation can therefore push us to consider how theater and society in general might engage madness through a critical model of disability that foregrounds these social concerns. Such representation would highlight the deleterious power wielded by clinicians and pharmaceutical companies. It would eschew the narrow and ultimately false concept of mental illness as only a genetic and biochemical brain disease that is stigma-free and can be understood and treated apart from cultural and social forces. It would address intersectional factors such as class, race and ethnicity, sex and gender, legal and social institutions, and other forms of disability that lead to oppression and increase individual distress. Lastly, it would consider not only this distress that so prominently delineates current concepts of madness, but also madness's inherent value and the critical knowledge that rises from experiences of psychosocial disability.

Done for the night, I turned away and walked down the sidewalk. As I approached my former client standing on the corner, I looked at him and smiled. But it had been a long time since we worked together, and he did not appear to recognize me. He looked past me with an unfocused gaze and a frown on his face. Important ethical problems of clinical practice, such as whether it is ever permissible to approach a former client uninvited, never have a single, obvious answer. That night I said nothing and continued down the street. Next time, I'll stop and ask what he's thinking.

Scott Wallin is a Ph.D. candidate in performance studies at the University of California, Berkeley. His current research investigates psychosocial disability and performance and builds on a background of psychiatric social work, acting, and directing for the stage. Education: B.A. in Dramatic Arts and Cultural Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara; M.S.W. in Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley; M.A. in Performance Studies, New York University.

Endnotes

-

Disability studies has not yet reached a clear consensus on what to call the experience of possessing ideas, behavior, and distress in ways that are considered abnormal and subsequently oppressed by others. Society generally uses the term "mental illness," which immediately pathologizes the condition. In Mad at School: Rhetorics of Mental Disability and Academic Life (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), Margaret Price reports that although she prefers "psychosocial disability" she discovered that the term ultimately "failed to mean" anything to other people (19). She therefore settles on the term "mental disability." For me, this latter term denotes cognitive difference but does not speak to sensory difference. It also doesn't signify behavior that is socially unacceptable. Because the term "mental disability" lacks political resonance, I continue to use "psychosocial disability." I do not always use this term, however, because people's "abnormal" individual thoughts and feelings are not always discussed or thought about in terms of oppression. Therefore, when I wish to refer to the individual experience of "abnormal" thoughts and feelings, I use the term "madness." When I refer to madness in a political context, I use "psychosocial disability." I occasionally also use the term "mental illness" in this article, and not always in scare quotes. I do so because mental illness as a concept remains widely used and internalized by people and therefore must be acknowledged in certain contexts. Furthermore, the experience of sickness, distress, and dysfunction remains part of madness, and I have no desire to deny that. Nevertheless, when I use the term mental illness, I wish to include the caveat that the term's signified pathology is always intertwined with cultural values and social realities.

Return to Text -

David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, Narrative Prostheses: Disability and the Dependencies of Discourse (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

Return to Text -

Julio Arboleda-Flórez, "The Rights of a Powerless Legion," in Understanding the Stigma of Mental Illness: Theory and Interventions, ed. Julio Arboleda-Flórez and Norman Sartorius. (West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2008), 1-18.

Return to Text -

Nancy Tobin, "Tackling Stigma from the Stage," bp Magazine, Fall 2009, http://www.bphope.com/Item.aspx/593/tackling-stigma-from-the-stage.

Return to Text -

Lawrence Toppman, "Brutally Honest 'Next to Normal' has Abnormal Power," The Charlotte Observer, 14 July 2011.

Return to Text -

Tony Brown, "Next to Normal at PlayhouseSquare: An Unblinking, Rock-Musical Look at Mental Illness," Cleveland.com, 7 June 2011, http://www.cleveland.com/onstage/index.ssf/2011/06/next_to_normal_at_playhousesqu.html.

Return to Text -

Misha Berson, "Next to Normal, Coming to 5th Avenue, Tries to Paint Authentic Picture of Mental Illness," Seattle Times, 19 February 2011. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/entertainment/2014247022_next20.html

Return to Text -

Tobin, "Tackling Stigma from the Stage."

Return to Text -

Victoria Ann Lewis, "Introduction," in Beyond Victims and Villains: Contemporary Plays by Disabled Playwrights (New York: Theater Communications Group, 2005).

Return to Text -

Next to Normal won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and three 2009 Tony Awards, for Best Original Score, Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Musical, and Best Orchestration. The U.S. touring production, in which Alice Ripley played the lead role, performed in San Francisco from 25 January to 20 February 2011.

Return to Text -

My description of Next to Normal draws primarily from the shows I attended during June 2009 at the Booth Theater in New York and during January and February 2011 at the Curran Theater in San Francisco. I have also consulted video recordings of performances in New York; Washington, D.C; and San Francisco. I also used Next to Normal: Original Broadway Cast Recording, CD, Sh-K-Boom, 2009; and the published book and lyrics: Brian Yorkey, Next to Normal (New York: Theater Communications Group, 2010).

Return to Text -

Charles McNulty, "The Family Next Door is Rocked by Crisis; The Pop Musical 'Next to Normal' Pulses and Ebbs in Its Ahmanson Visit," Los Angeles Times, 3 November 2010.

Return to Text -

"2010 Pulitzer Prize Winners: Drama," http://www.pulitzer.org/works/2010-Drama.

Return to Text -

The NAMI Awareness Night associated with Next to Normal in San Francisco took place on 11 February 2011 at the Curran Theatre. Advertisements for the event said that the goal was "to benefit the San Francisco affiliate of the non-profit National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) which is co-sponsoring NAMI Awareness Night, with the national touring company of the award-winning musical Next to Normal. The performance … will feature an after-show session with the Next to Normal cast, as well as information about NAMI's free educational and support programs for both family members and consumers dealing with mental health issues." See "NAMI Awareness Night-Next to Normal Performance," http://www.yelp.com/events/san-francisco-nami-awareness-night-next-to-normal-performance.

Return to Text -

Tobin, "Tackling Stigma from the Stage."

Return to Text -

See the official Facebook page for Next to Normal at http://www.facebook.com/n2nbroadway.

Return to Text -

Tobin, "Tackling Stigma from the Stage."

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

Brian Yorkey quoted in Greg Archer, "What's Next for Next to Normal?" The Huffington Post, 1 February 2011, my italics.

Return to Text -

In the opening song, "Just Another Day," the protagonist Diana begins "They're a perfect, loving family, so adoring / And I love them every day of every week." Yorkey, Next to Normal, 8.

Return to Text -

The discursive practices of psychiatry are deliberately reductive. The point of clinical language is to create an intelligibility and uniformity of description and treatment so that one doctor can pick up where another has left off. One of the many down sides of this practice is that people are reduced to their medical symptoms. This is a significant problem because psychiatric symptoms can never be truly separated from cultural values and lived experience.

Return to Text -

Deborah Sontag, "A Schizophrenic, A Slain Worker, Troubling Questions," New York Times, 16 June 2011.

Return to Text -

Ann Wilson and Peter Beresford, "Madness, Distress and Postmodernity: Putting the Record Straight," in Disability/Postmodernity: Embodying Disability Theory, ed. Miriam Corker and Tom Shakespeare (New York: Continuum, 2002), 143.

Return to Text -

Foucault, History of Madness. See also Michael Foucault, Psychiatric Power: Lectures at the Collège De France, 1973-74, ed. Jacques Lagrange, trans. Graham Burchell (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

Return to Text -

Tobin, "Tackling Stigma from the Stage."

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

Bradley Lewis, Moving Beyond Prozac, DSM, and the New Psychiatry: The Birth of Postpsychiatry (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006)

Return to Text -

Yorkey, Next to Normal, 26.

Return to Text -

"The Icarus Project: Navigating the Space between Brilliance and Madness," http://theicarusproject.net/, accessed 24 January 2012.

Return to Text -

Yorkey, Next to Normal, 26-27.

Return to Text -

Interview recorded by the author during the intermission of the 8 February 2011 Next to Normal performance at the Curran Theater in San Francisco.

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

Chris Caggiano, "Next to Normal Vastly Improved, but Still Biased," Everything I Know I Learned from Musicals: Musings on Musical Theater from Chris Caggiano (blog), 5 May 2009, http://ccaggiano.typepad.com/everything_i_know_i_learn/2009/05/next-to-normal-review.html.

Return to Text -

Chris Caggiano, "Next to Normal: Shaky Show, Irresponsible Message," Everything I Know I Learned from Musicals: Musings on Musical Theater from Chris Caggiano (blog), 4 February 2008. http://ccaggiano.typepad.com/everything_i_know_i_learn/2008/02/next-to-norma-1.html.

Return to Text -

"feeling electric," n.d., YouTube video clip, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iFk0Y1xGIuo, accessed 12 May 2012.

Return to Text -

"The Icarus Project: Navigating the Space between Brilliance and Madness."

Return to Text -

Ibid.

Return to Text -

Heather Stuart, "Media Portrayal of Mental Illness and Its Treatments: What Effect Does it Have on People with Mental Illness?" CNS Drugs 20, no. 2 (2006): 100.

Return to Text -

Angea K. Thacuk, "Stigma and the Politics of Biomedical Models of Mental Illness," International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 4, no. 1 (2011):140-163.

Return to Text -

Bruce Link and Jo Phelan, "Conceptualizing Stigma," Annual Review of Sociology 27 (2001): 363-385.

Return to Text -

Jo C. Phelan, "Genetic Bases of Mental Illness—a Cure for Stigma?" Trends in Neurosciences 25, no. 8 (2002): 430-431.

Return to Text -

Wilson and Beresford, "Madness, Distress and Postmodernity."

Return to Text -

James F. Sallis, Neville Owen, and Edwin B. Fisher, "Ecological Models of Heath Behavior," in Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, ed. Karen Glanz, Barbara K. Rimer and K. Viswanath, 4th ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2008), 465-485.

Return to Text -

Yorkey, Next to Normal, 39.

Return to Text -

Ibid., 14.

Return to Text -

Ibid., 73.

Return to Text -

Ibid., 21.

Return to Text -

Facebook and YouTube comments often gush about the actor's good looks and the fact that he appears bare-chested on stage.

Return to Text -

Ben Brantley, "Fragmented Psyches, Uncomfortable Emotions: Sing Out!" New York Times, 15 April 2009, http://theater.nytimes.com/2009/04/16/theater/reviews/16norm.html?pagewanted=all.

Return to Text -

Cindy Warner, "'Next to Normal' the Pulitzer Winner Opens Pandora's Music Box at Curran Theater," San Francisco Examiner, 28 January 2011.

Return to Text -

Yorkey, Next to Normal, 52-53.

Return to Text -

Louis Althusser argues that ideology transforms individuals into specific subjects by means of interpellation. Through discursive practices, ideology hails individuals and assigns them specific social meanings, which they must use to identify themselves as subjects. As such, they are subject to the authority and laws of that ideology and proceed to think and behave in socially acceptable ways. This is not to say that subjects cannot resist such authority. But they must operate within the parameters of their own subject formations insofar as they remain subjects. Individuals therefore resist and seek to change power structure and social values by destabilizing such ideology by identifying its inconsistencies and contradictions. Louis Althusser, "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses," in Althusser, Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (London: New Left Books, 1971), 121-173.

Return to Text -

Interview recorded by the author during the intermission of the 10 February 2011 performance of Next to Normal at the Curran Theater, San Francisco.

Return to Text -

Interview recorded by the author during the intermission of the 10 February 2011 performance of Next to Normal at the Curran Theater, San Francisco.

Return to Text