This essay argues that Tom McCarthy's 2003 film The Station Agent defies traditional theories about the representation of disability in Hollywood cinema. Moreover, the film offers a new model of visual relations for the post-ADA era, a model that challenges dominant principles about the voyeuristic, spectatorial gaze from traditional film theory as well as alternative principles of the managed stare from recent disability theory.

In his influential book The Cinema of Isolation, Martin Norden develops an argument that seems curiously inapplicable to Tom McCarthy's 2003 film The Station Agent. Norden argues that "most movies have tended to isolate disabled characters from their able-bodied peers as well as from each other." He suggests this portrayal is "consistent with the way that mainstream society has treated its disabled population for centuries." Isolation, he contends, "is reflected not only in the typical storylines of…films but also to a large extent in the ways that filmmakers have visualized the characters interacting in their environments; they have often used the basic tools of their trade—framing, editing, sound, lighting, set-design elements…—to suggest a physical or symbolic separation of disabled characters from the rest of society" (1). Writing just a few years after the enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act, Norden concludes that the ADA "has yet to exert much noticeable influence on moviemakers" (309).

McCarthy's The Station Agent clearly reverses the dominant pattern that Norden identifies in cinema. In direct contrast to a tradition of isolation, the focus of McCarthy's story is the gradual movement of Fin McBride, a man with dwarfism, from isolation to intimacy. Using disability theory as a tool for analyzing McCarthy's film, this essay will argue that The Station Agent is a post-ADA narrative about the complexities of integrating people with disabilities into the wider community. Since film as a medium inherently privileges vision and looking, The Station Agent focuses self-consciously on the visual protocols of inclusion and integration; thus, the film intervenes not only in the social treatment of people with disabilities but also conventions of filmmaking. The Americans with Disabilities Act represented a historic occasion to rethink the dynamics of the gaze, and The Station Agent takes up the challenge to reimagine how both social practices broadly and film practices specifically might change in accord with recent social changes.

My argument is rooted in a fundamental overlap between disability studies and film theory which has yet to be fully explored. Laura Mulvey's landmark account of the male gaze in "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" explores the way mainstream Hollywood film constructs and orchestrates vision as a device positioning viewers in particular ways: that is, as male subjects controlling the gaze, with female characters treated as objects in relation to whom the male self is defined. 1 Similarly, disability theorists such as Rosemarie Garland-Thomson have explored the way vision has been essential, historically, in the construction of disability as deviance. Garland-Thomson, for example, examines the way freak shows in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries erected sharp divisions between the able-bodied viewer and the disabled "freak." As Garland-Thomson puts it, "[f]eminization prompts the gaze; disability prompts the stare," suggesting the way gender and disability construction operate through similar visual dynamics (Extraordinary Bodies 28). In both Mulvey's theories on the male gaze and disability studies theories on the freak show, constructed, framed, orchestrated vision is used as a device in the construction of selfhood and the erection and maintenance of important social divisions.

Moreover, both theories are rooted in a model of vision as spectacle. "Mainstream film neatly combine[s] spectacle and narrative," Mulvey explains, routinely using the term spectators to describe viewers (11); "the mass of mainstream film, and the conventions within which it has consciously evolved, portray a hermetically sealed world which unwinds magically, indifferent to the presence of the audience, producing for them a sense of separation and playing on their voyeuristic fantasy," she adds (9). Similarly, for Garland-Thomson "the disabled body is a spectacle," part of a "complex relation between seer and seen" (Extraordinary Bodies 136). This treatment of vision as spectacle is a limitation, I will suggest, that virtually all of the subsequent scholarship has accepted. This is most true of film studies, where the idea persists even among critics who have challenged and qualified Mulvey's theories.

Disability studies, notably, has made important recent progress in addressing the problem. 2 In her book Staring: How We Look, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson attempts to complicate visual culture scholarship by emphasizing the active involvement of the viewee in looking relations. 3 She notes that the concept of the gaze "has been extensively defined as an oppressive act of disciplinary looking that subordinates its victim" (9). In response, she redefines her earlier term, the stare, to allow for a relationship between viewer and viewee that involves active agency on the part of the latter. As opposed to the gaze, staring is "an intense visual exchange" (9), a "communicative gesture" (185), she suggests; it transforms the staree from victimized object to subject. Garland-Thomson self-consciously makes this intervention in a post-ADA context in which disability is publicly evident much more often: "Now that civil rights legislation has removed many barriers to equal access, people with disabilities are entering and being seen everywhere….The public venues for the very stareable have expanded from sideshows to all parts of public life" (195), and this means that stares are taking more diverse forms.

Garland-Thomson's intervention is useful in acknowledging that looking can have various motivations and effects beyond the spectacular and the disciplinary. Her intervention also helps explain why contemporary performers with disabilities such as David Roche might actively engage in self-exhibition and how such performances might represent a positive experience for performers and audiences alike. The limitation in her theory, however, is that it depends on personal encounters between living individuals where the staree can actively respond to and manage the look of the starer. This limitation is particularly apparent in her final chapter, where she discusses Sontag's arguments about staring in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). Sontag theorizes staring as a "one-way dynamic, in part because she is considering photographs rather than lived interactions," Garland-Thomson writes, and as a consequence Sontag condemns staring as a form of inappropriate voyeurism (186). Garland-Thomson's alternative view of staring as a mutual, potentially productive interaction that takes on various meanings when involving living people does not offer much intervention in the analysis of films or photographs, nor does it help us rethink the way we might interact with such images. This essay will argue that McCarthy's The Station Agent suggests a way of conceiving the dynamics of vision that differs both from the voyeuristic gaze of traditional film theory and the managed stare of recent disability theory. Like Garland-Thomson in her new theory of staring, the film offers a model of looking that is more compatible with a post-ADA (and, one might argue, a feminist, multicultural) era.

The Station Agent begins with a series of scenes illustrating Fin's life in Hoboken, New Jersey, where he works for his friend Henry in a model train store. Most of these early scenes emphasize Fin's obsession with trains and his social stigmatization. His stigmatization revolves around visual reactions—people point him out, stare at him, tell their friends to look—and such gestures initiate a thematic concern with vision and looking that persists throughout the movie. In one of the first scenes in the movie, for example, a couple passes Fin in a grocery store and the man tells his companion to look at Fin. As the woman whispers back to be quiet, concerned that Fin might overhear them, the man laughs audibly. At the register, the cashier offers to help another customer before that person points to Fin, who is first in line but partially concealed by the register. The cashier apologizes rather insincerely, saying "I didn't see you" with a tone and expression that suggest unconcern. Invasive, unwanted visual attention alternates in this early scene with neglect of Fin's basic needs and rights due to his "invisibility"; this brief sequence in the movie concisely illustrates a dynamic that has been paradigmatic, historically, of the social experience of people with disabilities, and it demonstrates the way both social stigma and social neglect are connected to vision and its failings.

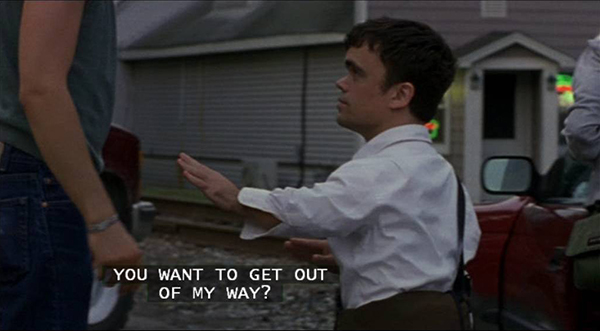

The emphasis on vision quickly turns self-reflexive in a subsequent scene at the model train store. Here we watch train enthusiasts watching a homemade movie (see Fig. 1). With shots alternating between the film itself and close-ups of the audience, the scene draws our attention outward to ourselves and our activity as film viewers. We are equated here with an audience that is obsessed with or fascinated by something quite ordinary: trains. Later in the movie Fin remarks to his friend Olivia that he finds it odd how "different people see me and treat me" when in fact he's a "very simple, boring person." The homemade movie suggests the way film contributes to this fetishization, and the scene begins to critique a practice that the film itself will try to undo.

Figure 1. Fetishizing the ordinary.

This early scene also suggests an underlying link between cinema and the railroad. In Parallel Tracks: The Railroad and Silent Cinema, Lynne Kirby explains that cinema emerged during the golden age of the railroad and the two institutions have important historical and cultural ties. Many of the earliest films were about trains, notes Kirby, including the first publicly-exhibited film, L'Arrivée d'un train (1895), and one of the classic early U.S. films, The Great Train Robbery (1903). Furthermore, the tracking shot, a fundamental film technique, derived its name from the use of railroad tracks to move cameras. "The railroad," writes Kirby, is "omnipresent in the history of film" (1); the two quickly became doubles, mirror images of each other, "the cinema find[ing] an apt metaphor in the train" (2) and the train frequently "a metonymy of vision itself" (243). Kirby's book is helpful in explaining the preoccupation with the railroad in The Station Agent as a further instance of the film's self-reflexivity.

After the train club meeting, Fin's friend Henry dies and bequeaths to Fin a derelict train station in the small town of Newfoundland, New Jersey. Fin moves into the station and meets Joe, a gregarious coffee and snack vendor who works from his truck parked in the depot lot. Chafing at his own isolation (he explains that he's filling in for his sick father; "I've been here for six weeks. It's driving me crazy," he says), Joe tries to befriend Fin. Perhaps as a result of his social stigmatization, Fin has cultivated a fierce self-containment, a kind of steely, impervious movement through social space resembling the trains with which he is so enamored. While Fin resists Joe's efforts, Joe is persistent. He invites himself on Fin's trainwatching and railway walking excursions, and eventually the two form a somewhat lopsided friendship.

Joe is the model in the film for an assertive, mostly benevolent invasion of privacy. Fin would like to remain isolated; it is, perhaps, his way of coping with the insults he suffers from people on a daily basis. Joe won't allow him to remain alone. There is some suspense early in the film about the merits of Joe's invasiveness. At one point, for example, Joe asks Fin out of the blue, "Do you people have clubs?" Joe has, until now, tended to avoid mentioning Fin's height in Fin's presence, and the unspoken implication of Joe's question is that "you people" means people with dwarfism. There's an awkward silence in the film coupled with an alarmed look from Olivia, the other character in the scene, who recognizes the possible offense in Joe's question. But Joe quickly says, "You know, like a 'train of the month' club?" and the film reveals, as Olivia visibly relaxes, that he's talking about Fin's hobby. Joe is the first character who defines Fin by something other than his height, and Joe begins to represent a model for respectful treatment of socially marginalized people. It is a model that depends on Joe's own experience of isolation. If Joe illustrates how a community gets integrated, it seems to depend on some degree of shared experience and a capacity for sympathetic recognition of one's own experience in others. It is ultimately the model that the movie proposes for cinema itself.

Joe's invasiveness in the film is not restricted to Fin. Through Joe, Fin gradually befriends Olivia, a middle-aged woman coping with the death of her son and the subsequent breakdown of her marriage. Like Fin, Olivia has moved to Newfoundland seeking solitude. She blames her son's death on her own failure of vision: "He fell off the monkey bars. I turned my head for a second…," she says, trailing off in pained guilt. Like Fin, one component of her emotional insulation is a desire for visual privacy. After first confiding in Fin about her son, she says, "Would you mind not looking at me right now?" Her desire for privacy goes beyond vision; she repeatedly pushes Fin, Joe, her husband, and other characters away. By focusing on three characters isolated for different reasons, the film erodes the conventional link between social isolation and disability, the link articulated by Norden in The Cinema of Isolation. While isolation quickly comes to be the central problem of the narrative—all three main characters are suffering from it—isolation is clearly not universal in its source or effects.

Brought together by Joe's unceasing efforts, the odd trio slowly develops a friendship as they walk the rails, eat together, and talk. Although Fin and Olivia remain wary of Joe's invasiveness, the middle scenes are the happiest moments in the film. Most of these scenes take place in daytime during sunny weather, unlike later scenes that are usually overcast or shot at night. Fin smiles for the first time in these sequences. The cheerfulness of this section of the movie is reinforced by a soundtrack that becomes folksy and upbeat.

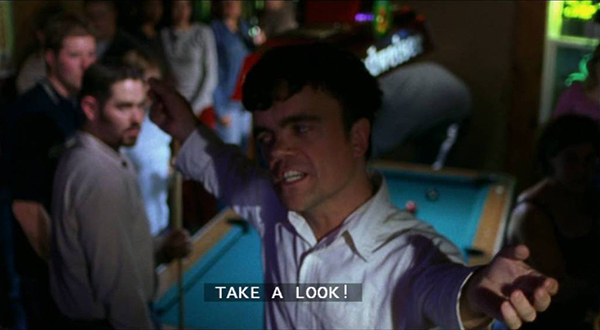

Things quickly unravel in this fragile friendship, however. Olivia learns from her husband that he is going to have a baby with another woman. She retreats into total privacy, refusing to see Fin and Joe. Meanwhile, Fin gets caught in a fight between the young local librarian, Emily, and her boyfriend, Chris. Emily is pregnant but doesn't want to move in with Chris, and when Fin tries to intervene he gets rudely pushed by the boyfriend, who has been consistently insensitive to Fin throughout the film. In a parting shot, Chris calls Fin a "freak." The film reminds us here of one of the dominant historical methods of visual representation of little people, the freak show. 4 In a fascinating reversal of the tactics of the freak show, however, this scene (as with many in The Station Agent) is shot from Fin's height, so that we watch, if not exactly from his perspective, at least from a comparable vantage point (see Fig. 2). Our intimacy with Fin is enhanced by the use of a close-up that centers on Fin and positions the other characters mostly offscreen; we can see Fin's face but not the faces of Emily or Chris. Because he is the only character we can see in any detail, our entire attention and sympathy are with Fin, whose expression is more apparent than it would be in a longer shot. The effect is a visceral rendering of Fin's experience, which is dominated by a sense of powerlessness and marginalization (a marginalization that is intriguingly at odds with the cinematography of the scene). We know Fin wants to help—it is one of the first occasions when he has come out of his shell to get involved in other peoples' lives—but he is powerless to do anything, a powerlessness that is underscored by the fact that Chris, a much larger man, shoves him effortlessly aside.

Figure 2. Chris tells Fin to get out of his way in a close-up shot from Fin's height.

Pained by his treatment and his powerlessness in this situation, and hurt by Olivia's abandonment, Fin copies Olivia's behavior and aggressively pushes Joe away. "I want to be left alone, Joe. Okay? That's what I want," he insists while rearranging the seat cushions in a train car, symbolic of his dubious effort to control the things in his life that provide comfort. Finally taking the hint, Joe departs. These scenes vividly illustrate the damage that isolation can do. Olivia is rejected by her husband, whom she admits she still loves but nevertheless consistently retreats from, Fin is hurt by Olivia's rejection, and Joe is pained by Fin's rejection. Rejection and isolation have a domino effect. The fact that this cycle of rejection is situated in such close narrative proximity to the incident involving the librarian's boyfriend (Chris literally pushes Fin away while Fin and Olivia figuratively push others away) suggests that acts originating in self-protection (Olivia's and Fin's behavior) may not be so different, at least in their effects, from acts rooted in aggression and insensitivity (Chris's behavior).

The film quickly illustrates the tragic consequences. At an emotional low point, Fin gets drunk in the local bar. While he had always avoided this place, presumably because it exposes him to unwanted attention, he now stands on a bar stool and invites the crowd to stare at him. "Take a look," he shouts angrily at the patrons twice (see Fig. 3). The camera angle in this scene is striking and troubling. Shifting from its typical position at Fin's height, the camera is now above Fin and looking down on him, mirroring the voyeuristic, alienating conventions of freak shows, as if obliging Fin in his invitation to view him in a degrading way. Afterward Fin leaves the bar, stumbles on some railroad tracks, and is nearly killed by a train in what appears to be an unpremeditated suicide attempt (he smiles ruefully as he looks up at the oncoming engine). Awakening the following morning, and jolted, apparently, into some self-awareness by the incident, Fin seeks out Olivia.

Figure 3. A drunk Fin invites attention in a crowded bar.

There is, again, some suspense about the value of this invasiveness. When Fin had initially tried to visit Olivia, after she retreated from him and Joe but before Fin's apparent suicide attempt, he camped out beside her house, reading, eating lunch, and smoking beneath a tree while watching her house and waiting for her to appear. In these scenes, which take place over several days, he even overhears a loud, angry, private phone conversation between Olivia and her husband, a moment Fin chooses, unfortunately, to confront her and ask if she's all right. Olivia reacts badly, yelling at him to get off her porch and leave her alone. However benign Fin's intentions may be, there is a strange voyeurism in the scenes leading up to the confrontation, as if Fin is stalking Olivia. The director might easily have included just the final scene in which Fin goes to the house, overhears the phone conversation, and meets Olivia. The point of these apparently superfluous scenes, I would suggest, is not only to create some suspense about the value of intrusive friendship, and not only to connect Fin's intrusiveness with Joe's behavior earlier in the film, but also to draw a connection between intrusive friendship and film spectatorship, which is often also conceived as a form of voyeurism (the well-known model of the cinema spectator as invisible voyeur peeking through a keyhole, the camera lens, at the private lives of characters in film).

If there remained any doubt about the value of invasive friendliness, however, the film emphatically lays that doubt to rest. After his near-death experience, Fin goes immediately to Olivia's house. In a scene that recalls the earlier ones of Fin's invasion of Olivia's privacy, he now enters her house uninvited just in time to prevent her suicide. Possibly Fin's own near-accidental suicide provides him with insight into Olivia's state of mind, and he enters her house without permission now, despite her previous anger at his intrusion, because he suddenly understands that her life is at stake. While the movie does not illuminate Fin's thinking sufficiently to confirm or deny this possibility, it is clear that in both Fin's and Olivia's stories, the movie equates profound social isolation with suicide and the death of the self, 5 and it represents the solution as Joe's benevolent invasiveness, adopted here by Fin.

Community is restored in the final scenes of the film. Earlier Fin had been asked by Cleo, a young girl interested in trains, to talk to her elementary school class about their mutual interest. Fin refused at first, offending and hurting Cleo in the process, but finally he agrees. The class visit represents the larger social model of the Americans with Disabilities Act in the sense that here Fin is actively integrated into a public, institutional space. The force keeping him away has not been accessibility, however; Fin has no physical difficulties navigating the school or other social spaces. His marginalization has been the result of his social treatment. In this, the film articulates a different basis from the ADA for the social exclusion of people with disabilities, a basis more consistent with Rosemarie Garland-Thomson's way of viewing disability as a social process rooted in stigmatization rather than a medical model of pathologized difference. 6 Fin's re-integration into the community does not go without a hitch, however. One of the students interrupts his presentation to make demeaning comments about Fin's height. The teacher removes the student. It is an interesting gesture. The story suggests that integration involves isolating those who are insensitive rather than isolating those perceived as different—a final and dramatic reversal of the tendency that Norden identifies in films involving people with disabilities. 7 This gesture is also, I would argue, the cinematic foundation of the film itself, which not only marginalizes hurtful characters (such as Chris) at the edges of the narrative but also presumes and helps erect a community of viewers who are sensitive and sympathetic to Fin. Moreover, the teacher is arguably an authority figure symbolically equivalent to film; the movie suggests, in other words, that authorities (implicitly including cultural institutions such as the cinema) have a vital role to play in the formation of tolerant, inclusive community. In this, perhaps, the film is aligned with the ADA.

The Station Agent ends with the smaller community also restored, as Fin invites Joe back and the three friends resume their relationship, sadder from their experience but more knowledgeable about the dangers of social isolation and the necessity of community. But this is no simplistic vision of community. Unlike most Hollywood films, the movie does not end by restoring the normative family, or uniting a romantic couple, or solidifying male bonds. On the contrary, the final trio represents a parody of family, 8 romance is the butt of a joke about Fin and the librarian in the final scene, and male bonds are thwarted by Olivia's presence.

As I suggested above, film theorists are inclined to regard cinema as fundamentally a form of voyeurism, a medium that sets up characters as Other, either Others against which the normative self is defined (as with freak shows) or Others toward which the self aspires (in the case of movie stars we admire, for example). 9 The Station Agent acknowledges that visual relations can objectify people. There are many scenes involving characters saying things like "Look at that" while gesturing toward Fin. In one striking scene, a clerk at a convenience store shouts to Fin to grab his attention and then whips out a camera and photographs him without his consent. These scenes clearly indicate that visual relations can be degrading and objectifying, and the photography scene in particular suggests how cameras are often involved in that process. Furthermore, the movie also acknowledges that community formation can represent an invasion of privacy, simultaneously visual, physical, and auditory. 10

But the film also suggests that we might view both cinema and looking as forms of community-building that demand a level of intrusiveness. As Rosemarie Garland-Thomson contends in Staring, looking may be socially and politically essential, a necessary part of social recognition. Being seen is comparable to the feminist demand for a public voice, she suggests: "the visual embrace of a stare is a validation of our being, the relational registering that we matter to another, even if it perhaps exposes our deepest vulnerabilities" (59). Citing the views of political philosopher Nancy Fraser, she adds that recognition "is essential not simply for individual self-realization but, more important, is the cornerstone of an ethical political society…. One becomes an individual subject only in virtue of recognizing, and being recognized by, another subject" (158). The Station Agent suggests additionally that visual intrusiveness can be valuable and even life-saving. The intrusiveness of film gets aligned with Joe's intrusiveness; that is, cinematic invasion of privacy is redefined as a practice that stems from a desire for friendship and the alleviation of loneliness rather than exploitation, prurient spectatorship, or, as film theory often suggests, psycho-sexual desire and identification.

The Station Agent emphatically rejects the alternative—isolation—as beneficial. While isolation may be, for Fin, an appropriate defense mechanism in degrading situations, it cannot permanently substitute for genuine comradeship. In Fin's and Olivia's stories, isolation drifts dangerously toward suicide. Community, on the other hand, is not idealized. Even friends can be hurtful at times. Not all of Joe's intrusions are appropriate or welcome. During the darker period in the film, when Olivia has distanced herself from the other main characters, Joe is feeling upset, and in one conversation he starts to pry inappropriately into Fin's sex life. He asks whether Fin has ever slept with a "regular-sized chick" and "someone [his] own size," questions which have no clear purpose other than prurient curiosity. Having come to trust Joe, Fin is initially open to his questioning, but when he recognizes the direction the conversation is heading he quickly tells Joe he doesn't want to discuss the subject. It's a painful scene. Not long after, Fin tells Joe emphatically he wants to be left alone. The scene acknowledges that voyeurism and sexual prurience can be elements of intrusive friendship. The rest of the movie, however, is committed to demonstrating that this need not always be the case.

In the same way, cinema itself is not idealized. The film does not imagine its own practice as one that accurately represents Fin's perspective. It is true that one of the striking features of the film is the way the camera is generally aligned with Fin's vantage point. McCarthy typically shoots scenes from Fin's height, with the effect that we see the world and other characters as the main character does. Some scenes, like the fight between the librarian and her boyfriend, are particularly noteworthy in the way the camera position directs audience sympathy and identification toward Fin. Moreover, the cinematography and composition of the film tend to emphasize horizontality. There are many gorgeous and striking scenes of trains or train rails spanning the screen from left to right, and the horizontal emphasis of these scenes is enhanced by the widescreen format of the film (see Fig. 4). One might argue that the film's emphasis on horizontality represents a shift away from a world conceived in vertical terms privileging height and an effort by McCarthy to imagine a world more suited to Fin's needs and desires, a world where height no longer dominates as a visual code.

Figure 4. This is one of many scenes shot at Fin's height and emphasizing horizontal elements.

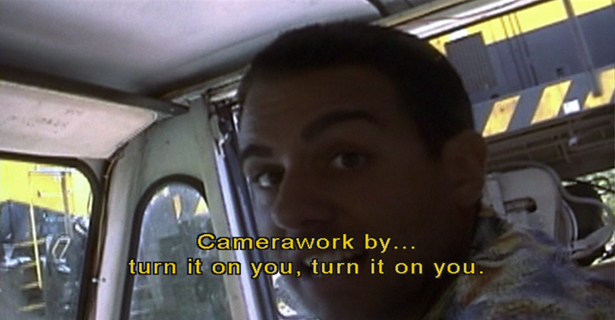

Despite this provocative evidence, a key scene suggests that the film might be attempting something other than a rendering of Fin's perspective. In this scene, Fin and Joe are chasing a train (see Fig. 5). Joe is driving his truck and Fin is filming the event from inside the truck. Fin did not buy the camera—it was a gift from Olivia—and although Fin is operating the camera, he is doing so at Joe's rather dictatorial commands. The scene opens with an initial long distance shot of Joe's truck pacing the train followed by a home-videocamera-style close-up of Joe inside the truck with the train in the background. "This is Joe Oramas reporting live from the inside of Gorgeous Frank's Hot Dog Emporium. Open every day from 7 to 3," he shouts excitedly over the noise of the train. Seeing the camera drift away from his own face toward the train, he orders Fin to "Keep it on me." He then acknowledges Fin: "Camerawork by…turn it on you, turn it on you," he commands, and his instruction is followed by a split-second, wildly tilted, out-of-focus close-up of Fin's nervous face as Joe shouts, "Finbar McBride!" The emphasis quickly shifts back to Joe's narration, as he yells wildly: "Whoo! We're train-chasing, baby!" While Fin obviously enjoys the experience, smiling through much of the train chase, he remains silent, and it is the raucous, screaming Joe who clearly dominates the scene just as he dominates the filmmaking method.

Figure 5. Joe directs Fin in the way to film the train chase.

The scene suggests that even if a little person is behind the camera and doing the filming he is still operating under the directives—the ideological direction or conventions—of people without disabilities, or a culture that assumes the absence of disability as the norm. Just as Fin did not buy the camera, he did not initiate the train-chasing adventure (that was Joe's idea), and Fin's attempt to film himself is clumsy and marginal to the main drama of the train chase. This self-reflexive scene, more than any other, undermines the idea that The Station Agent is attempting to represent Fin's perspective. Rather, the scene suggests the film is aligned with Joe's perspective. The audience—the ideal audience of the film—is like Joe: well-meaning, sympathetic, but, because of the nature of film itself, inherently intrusive. 11

Thus, the film does not operate in the way that Sharon Snyder and David Mitchell propose contemporary disability documentary cinema does; indeed, it offers an important challenge to their argument. Snyder and Mitchell accept conventional film theory in their premise that mainstream cinema portrays disabled bodies as exotic spectacles in a manner consistent with the scrutinizing, detached gaze of medicine and ethnography. They argue, however, that recent disability documentary cinema represents a "site of resistance and political revision" (193) to this conventional gaze because such films privilege the voices and perspectives of disabled people and, furthermore, those voices and perspectives inform the cinematic techniques of the films. Snyder and Mitchell ignore the possibility that conventional film techniques might continue to inform the practices of disability documentary directors through unconscious internalization of mainstream methods. Whether or not this is the case in disability documentary cinema, the train chase scene in The Station Agent suggests that that film is self-consciously neither an attempt to privilege Fin's voice nor his perspective. The film method is more closely aligned to Joe's curious, invasive perspective—a perspective which is similar to the medical, ethnographic gaze in its intrusiveness but different in its motivations.

The method by which isolated individuals are integrated or re-integrated into the community justifies the film methods—the occasional voyeurism and the persistent invasion of privacy. As an allegory for the integration of people with disabilities into the broader community, and physically "normal" characters into the lives and community of the disabled, the film suggests that integration perhaps inevitably involves intrusive curiosity and persistent, even if sometimes misguided and ill-informed, efforts at inclusion. The movie imagines the alternative as death, a literal death (Olivia's and Fin's suicides) standing for a symbolic social death. 12

In Parallel Tracks, Kirby argues that, during the period of cinema's emergence, prevalent cultural forces contributed to a model of social integration based on hierarchy and homogenization. Early cinema, she argues, mirrored the dynamics of the railroad. In uniting rural hinterlands with cities and jostling together people ordinarily separated by class, race, ethnicity, and gender, the train, like the cinema, "was a force of integration" (6). Yet the railroad relied on hierarchical domination by, for example, imposing standardized times in place of variable local times and by reinforcing various forms of institutional racism against, for example, African-American passengers and Chinese workers. In its early practices, Kirby argues, cinema operated according to the same principles, integrating a diverse population under a homogenizing cultural institution and perpetuating various forms of institutional racism in its depiction of minorities. Moreover, mainstream cinema, she suggests, adopted visual practices that were compatible with the principles of hegemony and hierarchy adopted by the railroad: namely, a detached, voyeuristic, spectatorial, leisure- and consumer-oriented, touristic sensibility that reflected an urban, middle-class, white perspective.

Like Kirby, film studies scholarship as a whole has made much of the fact that cinema originated at the turn of the twentieth century along with other modern phenomena, including the railroad as well as urbanized consumer culture. Scholars have used this historical coincidence to argue that cinema is rooted in a culture of voyeurism and detached spectatorship. Disability studies offers the added insight that voyeurism is the fundamental dynamic of the freak show, a major form of entertainment in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and this was another cultural force pushing cinema toward a model of exploitative spectatorship. It is perhaps no surprise, given the historical origins of cinema, that film theory is heavily indebted to psychoanalytic theories that originated at the same time. Freudian theories of voyeurism, fetishism, and narcissism, which are the basis of contemporary film theory, arose in conjunction with an urban, consumer culture of anonymity, alienation, and mobility, and those theories reflect an urban sensibility of detached spectatorship. 13

Film scholars might do more to interrogate the origins of their own theories, however. In particular, we might consider the possibility of other models of visual relations. Garland-Thomson offers one such model in her redefined concept of the stare. The Station Agent offers another such model—an intimate, relational model of looking consistent with its narrative emphasis on the value of egalitarian community and the necessity of social integration. The Station Agent is the antithesis of an urban film. The movie follows the journey of its main character from the large city of Hoboken to the small town of Newfoundland, and part of that journey involves the assimilation of certain "small-town" values. In one of the first encounters between Fin and Joe, after Joe realizes that Fin is living in the train depot beside which he parks his truck, Joe says, "Wow, we're neighbors. Nice." Joe models what one might call a neighborly theory of visual relations. It is a system, both social and visual, that involves the intrusiveness of voyeurism without the detachment and condescension. Like voyeurism, the model contains an element of selfishness. Joe's desire to befriend Fin stems from his desire to alleviate his own loneliness. But it is not pleasure at the expense of the other; it comes with responsibilities toward the other. As this essay has suggested, the movie does not simply idealize these social relations. 14 His relationships with Joe and Olivia bring Fin pain and discomfort as well as joy. But the movie suggests that it is necessary to Fin's happiness and psychological health. More broadly, the movie suggests that a neighborly model of social and visual relations might be necessary in a post-ADA age dedicated to non-hierarchical, non-homogenizing principles of social inclusion and integration.

In Extraordinary Bodies, Garland-Thomson identifies two major historical models of disability corresponding to the periods before and after the enactment of the ADA. The compensation model, reflected in such programs as workmen's compensation for industrial accidents, assumes a normative body and figures disability as a departure from or loss of able-bodiedness demanding compensation. It understands disability as deviance, "supports a narrow physical norm," limits economic benefits to those who are able to work in a system that excludes some from the outset, and is linked with the problematic and hierarchical politics of benevolent sympathy and paternalism (49). In contrast, the accommodation model embraced by the ADA dispenses with the idea of the norm, requires workplaces to accommodate physical variation, offers greater economic opportunity to more people, and abandons the politics of paternalism.

These two models of disability are reflected in two corresponding social and visual models. 15 As Kirby and others have suggested, the railroad historically represented a model of community formation founded in unity through subordination (to borrow a term coined by Alan Trachtenberg in The Incorporation of America). The deterioration of the railroad in The Station Agent (represented by the derelict train station and the many images of abandoned railroad cars) suggests the rise of a new social model. In McCarthy's film, a little person, a marginalized person, takes over the socially integrative role the train once played; he becomes the modern "station agent," a person who, Fin explains, once served as a unifying figure (a combination postal clerk-grocer-barber) around which a community revolved. By inserting a little person into a former railroad occupation, the film suggests that the ADA has replaced the railroad as an institution of social unification; Fin, as the modern station agent occupying the defunct station house, represents the shift from corporate, hierarchical (and, implicitly, racist and imperialist 16 ) forms of social integration to forms of integration founded in an expectation of diversity and opposition to discrimination, marginalization, and hierarchy. The visual effect of that change, the movie suggests, is a shift from voyeuristic spectatorship to intrusive neighborliness.

Works Cited

- Bal, Mieke. "The Gaze in the Closet." Vision in Context: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Sight. Ed. Teresa Brennan and Martin Jay. New York: Routledge, 1996. 139-53. Print.

- Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. Chicago: U Chicago P, 1988. Print.

- Brennan, Teresa and Martin Jay, eds. Vision in Context: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Sight. New York: Routledge, 1996. Print.

- de Lauretis, Teresa. "Film and the Visible." How Do I Look? Queer Film and Video. Ed. Bad Object-Choices. Seattle: Bay Press, 1991. 223-64. Print.

- Doane, Mary Ann. "Film and the Masquerade: Theorising the Female Spectator." Feminism and Film. Ed. E. Ann Kaplan. Oxford: Oxford U P, 2000. 418-36. Print.

- Dyer, Richard. Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society. New York: St. Martin's, 1986. Print.

- Ellis, John. Visible Fictions: Cinema, Television, Video. Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982. Print.

- Fiedler, Leslie. Freaks: Myths and Images of the Secret Self. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978. Print.

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York: Columbia UP, 1997. Print.

- ———, ed. Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York: New York UP, 1996. Print.

- ———. Staring: How We Look. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

- hooks, bell. "The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators." Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies. New York: Routledge, 1996. 197-213. Print.

- Jay, Martin. "Scopic Regimes of Modernity." Vision and Visuality. Ed. Hal Foster. Seattle: Bay P, 1988. 3-27. Print.

- Kaplan, E. Ann. "Is the Gaze Male?" Feminism and Film. Ed. E. Ann Kaplan. Oxford: Oxford U P, 2000. 119-38. Print.

- ———. Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film, and the Imperial Gaze. New York: Routledge, 1997. Print.

- Kirby, Lynne. Parallel Tracks: The Railroad and Silent Cinema. Durham: Duke UP, 1997. Print.

- Longmore, Paul. "Screening Stereotypes: Images of Disabled People." Screening Disability: Essays on Cinema and Disability. Ed. Christopher Smit and Anthony Enns. New York: U P of America, 2001. 1-17. Print.

- Mayne, Judith. Cinema and Spectatorship. New York: Routledge, 1993. Print.

- Metz, Christian. The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema. Trans. Celia Britton et al. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1982. Print.

- Mulvey, Laura. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." Screen 16.3 (1975): 6-18. Print.

- Neale, Steve. "Masculinity as Spectacle: Reflections on Men and Mainstream Cinema." Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in the Hollywood Cinema. Ed. Steve Cohan and Ina Rae Hark. New York: Routledge, 1993. 9-20. Print.

- Norden, Martin. The Cinema of Isolation: A History of Physical Disability in the Movies. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers U P, 1994. Print.

- Snyder, Sharon and David Mitchell. "Body Genres: An Anatomy of Disability in Film." The Problem Body: Projecting Disability on Film. Ed. Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotić. Columbus: Ohio State U P, 2010. 179-204. Print.

- Stacey, Jackie. "Desperately Seeking Difference." Feminism and Film. Ed. E. Ann Kaplan. Oxford: Oxford U P, 2000. 450-65. Print.

- The Station Agent. Dir. Tom McCarthy. Perf. Peter Dinklage, Patricia Clarkson, and Bobby Cannavale. Miramax, 2003. DVD.

- Straayer, Chris. Deviant Eyes, Deviant Bodies: Sexual Re-Orientations in Film and Video. New York: Columbia UP, 1996. Print.

- Trachtenberg, Alan. The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age. 1982. New York: Hill and Wang, 1997. Print.

Endnotes

- While more recent scholarship has qualified Mulvey's claims, particularly on the presumed masculinization of film audiences, critics continue to accept her premise that vision is central to the constitution of subjectivity and to divisions between self and other that are intertwined with broader social divisions. See de Lauretis, Kaplan ("Is the Gaze Male?"), Doane, Stacey, Neale, and hooks.

Return to Text - Although film studies remains largely devoted to the idea of vision as spectatorship, the broader field of visual culture studies has also challenged it. The contributors to Brennan's and Jay's Vision in Context argue for a variety of forms of looking that vary depending on historical circumstance and subject position. Mieke Bal argues in that volume, for example, that the gaze can be used for silent communication. In his earlier essay "Scopic Regimes of Modernity," Martin Jay suggests that competing modes of vision have been present throughout modernity and postmodernity.

Return to Text - Although two film critics imagine the possibility of a relational form of looking and thereby anticipate and inform her argument, Garland-Thomson develops the idea much more fully than previous scholars. See Kaplan, Looking for the Other (especially the Preface and Chapter 1), and Straayer (especially chapter 1).

Return to Text - For further discussion of freak shows, see Fiedler, Bogdan, and Garland-Thomson (Extraordinary Bodies and Freakery).

Return to Text - Like Norden, Longmore argues that a common solution to the threat represented by disability in mainstream film is isolation of characters with disabilities. Suicide and death often follow, he claims. The Station Agent rescues its characters from isolation culminating in suicide and death.

Return to Text - Garland-Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies.

Return to Text - See also Snyder and Mitchell, who argue that the new disability documentary cinema "designates degrading social contexts as that which need to be rehabilitated" (196).

Return to Text - That is, Joe and Olivia are not a couple and Fin is emphatically not a child. Nuclear families are consistently broken in this film, including both Olivia's family and Emily's potential family, and the movie overtly acknowledges and critiques the infantilization that is a part of Fin's social experience.

Return to Text - Most film scholarship focuses on the latter. See, for example, Ellis and Dyer on the functions of film stars. A great deal of psychoanalytically oriented film theory emphasizes the processes of identification that occur between audiences and characters generally; see, for example, Metz. Mulvey addresses both dynamics, including the way classic Hollywood film constructs woman as Other and the way this permits audiences to identify with male characters and fashion an identity in relation to masculinity.

Return to Text - By physical, I mean that characters often intrude on the physical space of other people. In one comic scene, Joe tries to put his feet on a stool that Fin is using as they both sit reading together. Fin clearly regards Joe's act as intrusive—in part, no doubt, because Fin needs the stool to be comfortable in a chair sized for a larger person. After Fin looks at his feet without speaking, Joe ends up putting his feet back on the ground. By auditory, I am referring to the cell phones that ring intrusively in the film, or the humorous scene where Joe tries to engage Fin in conversation after promising that he only wants to sit and read with him.

Return to Text - We learn early in the film that Joe is looking for "cool people"; he tells Olivia he's having a hard time finding people he likes in Newfoundland. By "cool people," Joe apparently means quirky, interesting, sensitive outsiders. Joe himself is an outsider in Newfoundland; he speaks Spanish, he's of Cuban descent, and he's an urbanite from Manhattan. If Joe is the viewer's surrogate in the film, then the film constructs the ideal audience as those who gravitate toward outsiders because they themselves have some experience (any experience) of outsiderdom, which takes many forms. Thus, the film attempts to construct its own community of sensitive outsiders, or, in Joe's terms, "cool people."

Return to Text - Although certainly, given the high rates of suicide among people with dwarfism, stigmatization has effects that are more than merely symbolic.

Return to Text - For an overview of film theories of spectatorship, see Mayne.

Return to Text - In an interesting related scene, Fin explains the history of the term "walking the right-of-way," a term Fin uses to describe his hikes along the railroad tracks. He explains that in the past the U.S. government seized private land because railroads claimed they needed the "right-of-way." Interestingly, the film does not clearly condemn this seizure of private property. The necessity of community formation, in which the railroad was instrumental, takes precedence over privacy in the film, even where the right to privacy involves property ownership. This mirrors the film's larger claim that community formation justifies the invasion of privacy.

Return to Text - Similarly, bell hooks identifies a shift in African-American viewing practices coincident with the political abandonment of segregation. "Before racial integration, black reviewers of movies and television experienced visual pleasure in a context where looking was also about contestation and confrontation," she writes (199).

Return to Text - While the film does not overtly address the subject of imperialism, it does explore the subject of race in its treatment of Cleo and Joe and the friendships those characters form with Fin and Olivia.

Return to Text