The US Virgin Islands Department of Education receives funds from the United States Federal Government and must abide by educational laws that the government develops. The purpose of this research is to assess the attitudes and preparedness of school personnel employed by the US Virgin Islands Department of Education to support federal mandates such as Inclusion, as intended and in accordance with the reauthorized Individuals with Disabilities Act of 2004. For the purpose of this study, some 575 Inclusion Questionnaires were completed (totaling 20% of VI school personnel). This included 10 principals, 346 general education teachers, 47 special education teachers, 25 vocational teachers, eight (8) school psychologists, six (6) counselors and 81 other or paraprofessionals. Results indicate that school personnel attitudes and beliefs are similar regardless of their position in the school system, age or years of experience. Solutions to developing and maintaining inclusive public school settings are discussed.

Introduction

The United Stated Virgin Islands (USVI) is a territory of the United States and is a collection of four main islands - St. Croix, St. Thomas, St. John, and Water Island - and many small, mostly uninhabited, islands. The US Virgin Islands is located in the Caribbean Sea approximately fifty miles east of Puerto Rico. The territory is divided into two districts: the St. Thomas/St. John district and the St. Croix District. The estimated total population of the US Virgin Islands is 109,677 with 51,389 individuals residing on St. Croix, 54,259 on St. Thomas, and 4,030 on St. John. The USVI is very culturally diverse. The majority of the population is comprised of individuals of African descent.

Africans were brought as slaves to the Virgin Islands initially during colonization, a period of some 300 years before United States ownership. Later, individuals of African descent came as a result of tourism and trade, influenced by the purchasing of the islands by the US in 1917. Between the early 1600s and 1917, St. Thomas, St. Croix, St. John and Water Island came under the rule of several countries including Holland, France, England, Spain and Denmark. They became the US Virgin Islands upon transfer to the United States from Denmark on March 31, 1917 for the purchase price of $25 million.

Currently, residents migrate from many other Caribbean islands of the Lesser and Greater Antilles and from the United States mainland. Racial composition, according to 2000 US Census data, is as follows: Black or African American alone 76%, White alone 13%, Asian or Pacific Islander alone 1%, other race alone 6%, two or more races 3%. Also according to those data, in terms of ethnicity, some 15,355 persons are of Hispanic origin (14% of the total population), with the majority residing on St. Croix. There, the Hispanic population represents 27% of the population.

Additionally, the US Virgin Islands is currently experiencing an influx of Hispanic and French speaking persons due to damages from hurricanes, poverty and health conditions of neighboring islands. These trends are consistent with those at the national level. According to data provided by the Virgin Islands Department of Education, there was an estimated 15,903 students, ages 3-21, enrolled in the public schools during the 2007-2008 school year. Out of this total, 674 students between the ages of 3-21 were identified as receiving special education services in the St. Thomas/St. John school district, and 883 identified as receiving services in the St. Croix school district. There were 743 teachers employed in the St. Croix district and 681 teachers employed in the St. Thomas-St. John district during the 2007-2008 school year.

Pivik, et. al. (2002) stated that children with disabilities represent an especially vulnerable class of citizens, and special laws and policies in the United States and Canada have been in place for over 25 years promoting full participation and integration of these children into society, particularly in the education setting. This is also the case in the US Virgin Islands. The US Virgin Islands Department of Education receives funds from the United States Federal Government and must abide by the Federal Government's educational laws. Such laws include Public Law-94-142 (the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973), the Americans with Disabilities Act, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and the most recent No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001, which introduced numerous changes in Elementary and Secondary Education in the United States. As these laws were authorized and in some cases reauthorized, education leaders and policy makers of the Virgin Islands Public School System (like their counterparts in other states and territories) were obliged to reevaluate the existing vision, mission, and core values that guided the system and determined how they correlated with students' academic performance.

In addition to the historical timeline of education law on the national level, a local court case seriously impacted the way the Virgin Islands Department of Education complies with the federal laws. This case is Nadine Jones, et. al v. Government of the Virgin Islands (2007). The plaintiff was a young girl with a disability, whose parents sued the Virgin Islands Department of Education for failing to adhere to her Individualized Education Program (IEP). As written in the consent decree, the Department of Education had no timely mechanism for impartial due process hearings and it failed to provide a free and appropriate public education, in that it failed to provide related services. As a resolution to this case, both the plaintiff and defendant agreed to: 1) address USVI Child FIND (US Virgin Islands Family Information Network on Disabilities) requirements and parents' rights when making referrals for special education services, procedures for evaluation and eligibility; and 2) the development of Individualized Education Programs more immediately (ten days) after an eligibility meeting. Although the main focus of this case was the rights of students with disabilities in education, the court's decision forced educational leaders to begin to align their policies, procedures and curriculum standards to those mandated by the United States State Department of Education.

The education of special education students continues to be a topic of great debate in the education arena, especially now that school districts are required to meet Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) standards. Education leaders and policy makers must report the academic performance of students with disabilities as part of their AYP data, in order to receive federal funding (Roybler, 2002). According to Hardman and Dawson (2008), the promise of academic success is non-exclusionary and therefore includes students with disabilities. Schools must now ensure access to the curriculum on which universal standards for all children are based. Additionally, educational leaders and policy makers have to identify creative ways of addressing the needs of these students. This includes addressing their needs during standardized testing, in the least restrictive environment. With the use of assistive technology and related services, more and more students with disabilities are being mainstreamed and provided with more access to the general curriculum.

Teachers (general and special education simultaneously), parents and administrators are required to carefully collaborate and decide on effective placement for each individual child with an Individual Education Program, annually. One might ponder the difference in the requirements regarding placement of children with disabilities to date, in comparison to those of the past. The premise for the disability rights movement was for the inclusion of people with disabilities. In terms of education, lawmakers and advocates want to change the procedural formats regarding how children with disabilities receive services and are educated. They want to first change from a model of special education classes (i.e. separate facilities, secluded classes, pull-out models, resource settings, etc.). They would then like to gradually move into the general education setting, to a model of students with disabilities being given general education first, with the appropriate related aids and services that will assist them in achieving academic success.

This procedural shift is resulting in more students with disabilities being exposed to the general education curriculum at earlier ages and in multitudes. More students are being included not just in the vocational and physical education courses, but in the core subjects as well. As more Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) are drafted by IEP teams (special educator, general educator, school administrator and a special education representative) for students with disabilities to attend classes with their non-disabled peers, there is a growing body of concern by both the general educators and the special educators as to the appropriateness of such a phenomenon. In an effort to validate the need for this research, we believe it is important to provide a historical outline of the term "Inclusion."

In the late 1980s and 1990s many researchers showed the negative effects of tracking children in homogenous ability groups (Oakes, 1985; Lipsky & Garner, 1997; Ogle, Pink, & Jones, 1990 and Wheelock, 1992). It could be argued that this body of research, along with advocacy such as that exhibited by Madeleine Will in her 1985 Wingspread Conference (Racine, Wisconsin) speech, marks the first seeds of issues of inclusion. Will's contribution to the matter came during her tenure as Assistant Secretary for the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, U.S. Department of Education. Her Wingspread Conference speech, which was reprinted the following year (Will, 1986), to a large degree, endorsed inclusion on behalf of the federal government. Subsequent to the late 1980s and 1990s many parents and advocates of children with disabilities began to question and organize themselves against separate education programs. They started advocating for their children to learn with their peers in regular classrooms. This marks the birth of "Inclusion."

Inclusion refers to the placement of a child with disabilities in a general education classroom, with supports that the child needs in the classroom (Salend, 2001). This applies to students being diagnosed with either low or high incidence disabilities. Connor and Ferri (2007) explained Inclusion as a philosophy that has the potential to fundamentally change the foundations of special education, as well as the American educational system nationally.

Many organizations endorsed this new philosophy. The National Association for State Boards of Education (NASBE) was among the first to strongly endorse the "full inclusion" of students with disabilities in regular classrooms. In 1992, NASBE released a report titled "Winners All: A Call for Inclusive Schools." The report called on states to revise teacher-licensure and certification rules so that new teachers would be prepared to teach children with disabilities as well as those without disabilities. It also recommended training programs to help special educators and regular educators adapt to collaborating in the classroom. Around the same time, another organization that had passed a resolution supporting inclusion was the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

As schools moved ahead with implementation of inclusive education, a spectrum of opposition developed. Educators and researchers began to line up behind and support one of three positions: no inclusion, inclusion and full inclusion. The position of no inclusion is an obvious one. With regard to the notion of inclusion vs. full inclusion, the literature reflects that the "inclusionists" support the position that there is a limit to which students with certain disabilities can be fully accommodated in the regular classroom and that a continuum of services (e.g. special education placement, as needed) is the most appropriate model for them. On the other hand, "full inclusionists" believe that all children, regardless of disability, belong in the regular classroom all of the time and that pulling them from the regular classroom for any period of time, for special education placement, is counterproductive to the goals and objectives of inclusion (e.g., Fuchs and Fuchs, 1998).

The late Albert Shanker, former President of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) writing in opposition to the notion of full inclusion for the AFT, in his weekly column, "Where We Stand," (1996), penned this:

What full inclusionists don't see is that children with disabilities are individuals with differing needs; some benefit from inclusion and others do not. Full inclusionists don't see that medically fragile children and children with severe behavioral disorders are more likely to be harmed than helped when they are placed in regular classrooms where teachers do not have the highly specialized training to deal with their needs. (NY Times, p. E7)

While Shanker, in that article, voiced his concerns against full inclusion, there are many educators and researchers who believe that Inclusion, be it "full" or as intended by the reauthorized Individuals with Disabilities Act of 2004, does not benefit all students. That Act reads as follows:

To the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are not disabled, and special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily. (Individuals with Disabilities Act of 2004, Pub. L. no. 108-446, 118 STAT 2677) (2004)

They wrongly think that teachers in the regular classrooms are not adequately trained to meet the needs of the special education student (Top, 1996). Another myth that works against the philosophy of inclusion is that many educators, and other lay persons, think that inclusive education is designed to benefit children with disabilities only. To the contrary, research shows that inclusive education helps the development of all children in different ways. Wolery and Wilbers (1994), for instance, indicate that although, inclusion is primarily designed to allow children with disabilities to learn with their peers in the regular classrooms, the benefits are extended to children without disabilities, parents of children without disabilities and by and large, the whole community.

Others think that the additional time, children with special needs require, is time taken away from general education students (Irmsher, 1996). To the contrary, many researchers are showing that inclusive education promotes and enhances all students' social growth within inclusive classrooms and does not negatively affect typical students' academic growth (Freagon, 1993; Goodlad and Lovitt, 1993). Such studies also show that the presence of students with severe disabilities in regular classrooms does not affect teachers' levels of allocated or engaged time. Arguably, there are different beliefs and perceptions about inclusive education that vary from state to state and territory to territory. The purpose of this research is to assess the attitudes and preparedness of school personnel employed by the US Virgin Islands Department of Education to support the federal mandates of Inclusion according to the reauthorized Individuals with Disabilities Act of 2004 as written above.

According to Connor et al. (2008), there are no shortcuts "to insuring that institutions become learning organizations around the principles of inclusive education." That will happen, they suggest by "cultivating theory, expanding research and defining practice." Likewise, as school districts—locally, nationally, and internationally—attempt to restructure their schools' culture and climate and revamp school policies to facilitate a more inclusive school environment, the attitudes and preparedness of school personnel must be addressed. It is possible that attitudes and preparedness of school personnel vary from state to state, region to region and in US territories. In that regard, the results of this study are important. They can help in the defining of theory, expanding research, and defining practice.

Further, from a national and international standpoint, the findings here can make a significant contribution to the literature in that analyses of attitudes of school personnel in the US Virgin Islands towards inclusion can be compared to the results of current and future studies to determine the extent to which differences may or may not exist by geographic location. In their article on educator attitudes toward inclusion, a study conducted in Australia, Subban and Sharma (2005) support this notion by suggesting that future studies consider the influence of variables such as geographic location on teacher attitude and concern about inclusive education. The results of the research presented here, which was conducted in the US Virgin Islands, provides a step in that direction, in that they begin to help address the question of how educators in different geographic locations feel about inclusion.

From a local standpoint, the findings of this article can be helpful to the territory's education system in that they will provide some evidence of the extent to which existing practices, policies and programs may be impacting the attitudes and beliefs of Virgin Island school personnel, regarding Inclusion. As a matter of policy the Virgin Islands territorial school system supports and encourages the concept of inclusion. Throughout the Islands, there are many examples of such support; collaborative teaching or co-teaching to support inclusive practices, for instance, has been implemented in several Virgin Island schools. Trainings on inclusion have been provided to Virgin Island teachers, through the VI Department of Education's division of Special Education. A course featuring inclusion, taught by the primary author of this article, is offered at the University of the Virgin Islands, for teachers. Additionally, conferences, workshops and technical assistance, all related to inclusion, are provided for Virgin Island school personnel through the Virgin Island University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (VIUCEDD), where two of the authors of this article are senior administrators.

Since the majority of school personnel in the Virgin Islands, including teachers and administrators are individuals who have received at least one college degree from the University of the Virgin Islands (UVI) and the majority of future employees will, in all likelihood, continue to be graduates of this institution, the findings in this article can help UVI, the VI Department of Education and other local organizations in the development of better policies, programs and practices that foster inclusion.

Additionally, the continued study and comparison of attitudes towards inclusion and preparation for addressing issues related to inclusion, can provide the basis of additional research, help provide answers to questions and concerns regarding the development of inclusion policy, as well as aid program development and implementation in the US Virgin Islands and beyond.

Research Questions

- What is the attitude of educators in the USVI (teachers, administrators, counselors and paraprofessionals) towards including children with disabilities in general classrooms?

- Is there significant difference among Virgin Islands teachers regarding how they perceive inclusion, based on sex, age, years of teaching experience and educational qualifications?

- Are Special Education teachers more supportive of implementing inclusion than regular education teachers in the US Virgin Islands Schools?

- How do educational leaders in the Virgin Islands public schools view inclusion?

Sample

There are fifteen hundred (1,500) fulltime teachers teaching in the St Croix and St. Thomas/St. John districts in the United States Virgin Island. For the purpose of this study, 20 percent of the total teaching and administrative staff in each school was selected. Approximately six hundred questionnaires (600) were distributed and five hundred 575 were returned. Analyzing the sample revealed that the participants of this study included 10 principals, 346 general education teachers, 47 special education teachers, 25 vocational teachers, 8 school psychologists, and 6 counselors. Eighty-one (81) of the respondents categorized themselves as "other" or as paraprofessionals. There were 69 individuals who identified themselves as male, 475 who identified themselves as female, while 31 participants did not answer the gender question. Participants were also categorized by age. There were 79 individuals who indicated they were between the ages of 20-30; 141 between the ages of 31-40; 163 between the ages of 41-50 and 157 indicating the age of 51 and over. Thirty-five (35) respondents chose not to indicate their age.

Instrumentation

The "Inclusion Questionnaire" (see Attachment A) is a nineteen-item questionnaire developed by the authors to fit the Virgin Islands community and is divided into four parts. Its development was not influenced by any existing instruments. The first part deals with "Attitudes and Beliefs Towards Inclusion" and has seven items. The second part addresses "Services and Physical Accommodations" available in the public schools for students with disabilities and the third part focused on "School Support," or support that the public schools extend to children with disabilities. Part Two has two items. Part Three contains ten items. The fourth and final section asked for "Biographical Information" and generated information on the respondents' position, school level, degree earned, age, gender and years of experience. Before the questionnaire was administered, it was pilot-tested on twenty teachers who were taking classes at the University of the Virgin Islands. Almost all of these teachers indicated they found the questions clear and that the survey instrument was asking the right questions.

Methodology

The results of this research will be given based on the categories of Attitudes and Belief, Services and Physical Accommodations, and School Support as they were separated on the Inclusion Questionnaire surveying instrument. Pearson Chi-square tests of independence were calculated on each Survey Question (items 1-21) and by Biographical Information (items 22-29). Statistically significant conjoins [p< .05] are indicated. First the data were analyzed based on the number of respondents, per question, to determine their level of agreement as identified by the Likert-scale (i.e. strongly disagree (SD), disagree (D), don't know (DK), agree (A), strongly agree (SA)).

Findings and Discussion

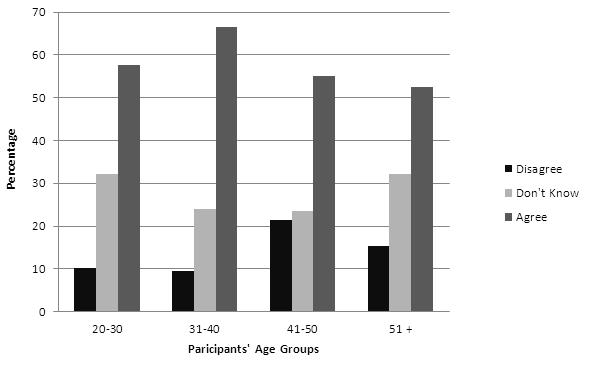

The first category on the survey questionnaire was entitled Attitudes and Beliefs. Participants responded to seven questions in this section which was designed to answer the first research question exploring the attitude of Virgin Islands educators towards inclusion. The first area of emphasis in which crosstabs were generated was School Support by the participants' ages. The categories of this data set were 20-30, 31-40, 41-50, and 51 and older. When asked to rate the following statement: "Students with disabilities are included in school and district assessments and necessary modifications are provided as needed," as indicated in Table 1 below, participants 20-30 years of ages responded with 10.2% disagreeing with the statement, 32.1% not knowing and 57.7% agreeing with the statement. Results for the participants ages 31-40 were: 9.4% disagreed, 23.9 did not know and 66.6% agreed. Participants ages 41-50 results indicated that 21.5% disagreed with the statement, 23.4% did not know and 55.1% agreed with the statement. The last age group was those 51 and older. Their results revealed that 15.4% disagreed with the statement, 32.1% did not know and 52.5% agreed.

Table 1: Responses to the statement: Students with disabilities are surportively included in school and district assessments and necessary modifications are provided as needed. (n = 563)

These numbers are particularly important in that they suggest the age of the educator does not prevent their being familiar with the assessments being given and to whom they are given throughout the schools. These results also give credibility to the notion that students with disabilities are being included during annual assessments.

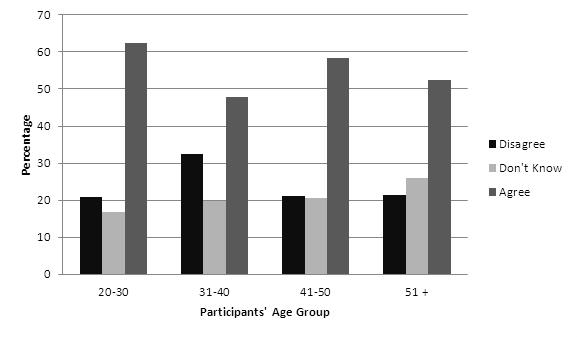

In response to the Statement: "We individualize the instructional program for all children whether or not they are disabled and provide the resources that each child needs to explore individual interests in the school environment," as indicated in Table 2 below, participants in the age group of 20-30 responses were 20.8% disagreed, 16.9% did not know and 62.3% agreed. Participants in the age group of 31-40 responses were 32.4% disagreed, 19.9% did not know and 47.8% agreed. Additionally, persons in the age group of 41-50 indicated that 21.1% of them disagreed, 20.5% did not know and 58.3% agreed. Lastly, participants in the 51 and older category responses indicated that 21.5% disagreed, 26.1% did not know and 52.3% agreed.

Table 2: Responses to the statement: We individualize the instructional program for all children whether or not they are disabled and provide the resources that each child needs to explore individual interests in the school environment. (n = 555)

These results speak to the idea that educators, regardless of their age, understand the need to maintain student-centered environments as much as possible in an effort to educate each child successfully.

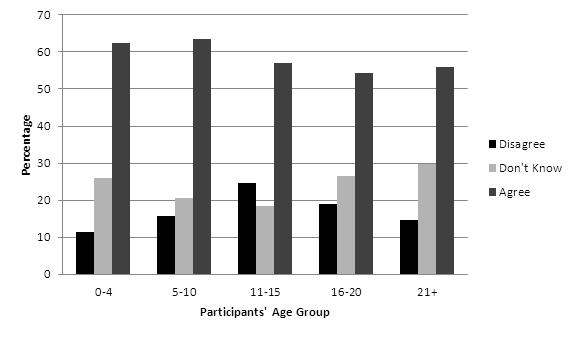

The second area of emphasis, in which crosstabs were generated, was School Support by the participants' years of experience for item 18: "We actively encourage the full participation of children with disabilities in the life of our school including co-curricular and extracurricular activities." As indicated in Table 3 below, the categories for this data set were 0-4years, 5-10 years, 11-15 years, 16-20 years and 21 or more years. In the 0-4 years category 11.5% of the participants disagreed with the statement, 26.1% did not know and 62.3% agreed. In the 5-10 years category participants stated that 15.7% of them disagreed with the statement, 20.7% did not know, and 63.6% agreed. The next category was 11-15 years. The results were 24.6% disagreed with the statement, 18.5% did not know and 56.9% agreed. In the category of 16-20 years, 19.1% disagreed with the statement, while 26.5% did not know, and 54.4% agreed. The last category was 21 years or more and the results were 14.6% disagreed, 29.7% did not know and 55.8% agreed.

Table 3: Responses to the statement: We actively encourage the full participation of children with disabilities in the life of our school including co-curricular and extracurricular activities. (n = 559)

Contrary to the findings of Subban and Sharma (2005), years of experience, in this study, did not generate significant levels of difference in the responses for any other items. Trends in participants' responses were more or less the same regardless of the question.

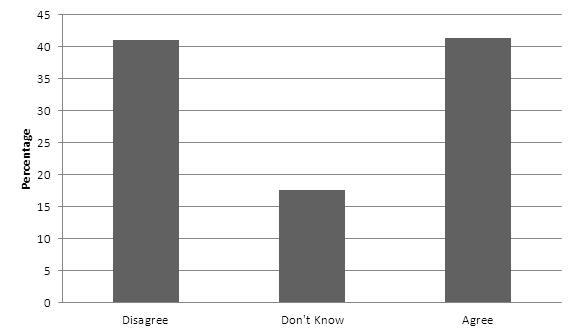

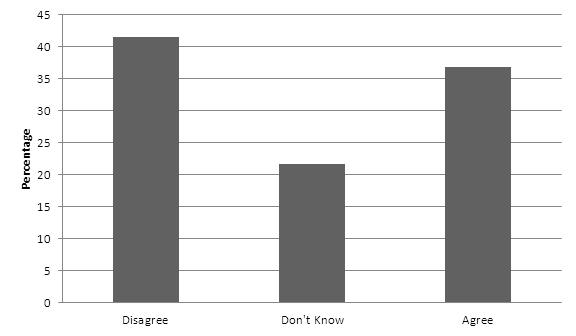

When asked to respond to the statement: "The regular teacher believes that students with disabilities can succeed (successfully participate) in the regular education setting", as shown in Table 4 below, the respondents were equally divided. About 41.47% was very much in the affirmative, compared to the same number 41.47% in the negative.

Table 4: Responses to the statement: The regular teacher believes that students with disabilities can succeed (successfully participate) in the regular education setting. (n = 561)

The authors found this very puzzling. Given the many awareness workshops that have been conducted in the Virgin Islands for public school teachers and other educational personnel, it is tempting to suggest that these respondents should know that inclusion is law of the land and therefore should have responded affirmatively at a much higher percentage rate. It is very possible that these individuals have simply made up their minds about inclusion, one way or another. It is also possible, in light of the inclusion vs. full inclusion debate, that some respondents believe some students with disabilities can succeed while others (e.g. those with "more serious" disabilities) cannot be successful. Inclusion is not a simple black and white issue. The results here, however lead us to conclude that for whatever the reason, roughly half of the people believe that students with disabilities can participate successfully in the regular classrooms with their peers, while the other half does not believe so.

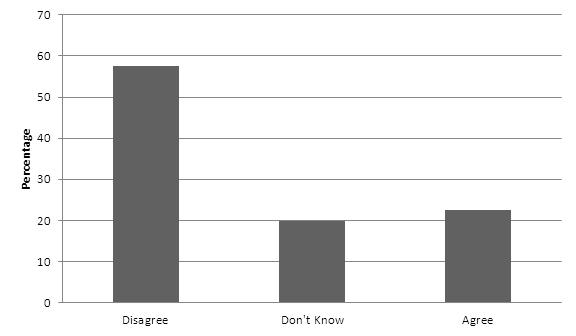

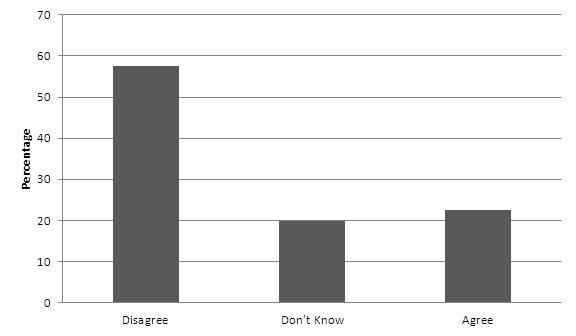

When asked to respond to the statement, "School personnel are prepared to teach students with disabilities in the regular education setting," as indicated in Table 5 below, many of the respondents (57.5%) indicated their belief that the school personnel were not ready.

Table 5: Responses to the statement: School personnel are prepared (professional development/other training) to teach students with disabilities in the regular education setting. (n = 567)

Some teachers believe they are not trained to teach children with disabilities. They often use their lack of training as an excuse to resist admission of children with disabilities to the regular classrooms. Such teachers are heard saying they need "special skills" to teach children with disabilities.

Institutions of higher education have contributed immensely to this problem. Most schools train teachers to teach in regular classrooms and special classrooms. They call the former, teachers and the later, special education teachers. The schools that certify these teachers tell them that they cannot teach children with special needs if they come to the regular classroom…that only specially trained teachers are supposed to teach children with disabilities. The irony is institutions of higher education talk "inclusion" and practice "exclusion".

Additionally, Connor and Ferri (2007) noted that more often than not, the word "special" becomes synonymous with exclusion, segregation and marginalization. That is, when a student is removed from the classroom to receive instruction or support related to his or her disability the act of removal can serve to reinforce notions of difference and deficiency to both the student and his or her peers. Inclusion mediates against such perceptions. Not having to remove a student from the classroom for special instruction is a goal of inclusion because of the belief, as supported by research, that it is beneficial to students who have disabilities as well as those who don't. Removal of a student from the classroom is not always necessary because a good teacher can teach children with disabilities and those without disabilities in the same classroom. This is nothing new. Over the years, good teachers have proven that children with disabilities can be taught in the same classroom with non disabled children, through the use of a well-planned teaching approach which encourages the active participation of all children.

It seems that the practice of segregating students by ability in the Virgin Islands public schools is not only endorsed by the administration but is also accepted by the students. When teachers were asked to respond to the statement: "Students in the general education setting are prepared to accept students with disabilities" the response was very alarming. As show in Table 6 below, a large number, 41.5%, do not think that non-disabled students are prepared to be in the same classroom with children with disabilities.

Table 6: Responses to the statement: Students in the general education setting are prepared to accept students with disabilities. (n = 562)

Although this number is high, the authors believe this number is declining and there is need for more character education activities and social-emotional activities of both groups of students together that would foster the acceptance of children with disabilities in the classroom.

The results of the survey also revealed that Special Education teachers (64.8%) are committed to collaborative practice that will be required to help students with disabilities succeed. This is welcoming news. A few years back when the primary author was conducting workshops on inclusion for the public school teachers, many of the teachers who were showing resistance to inclusion were special education teachers. This is understandable; many of these teachers were working in a secluded, but safe environment; and were not willing to venture to open an unknown environment of inclusive classrooms.

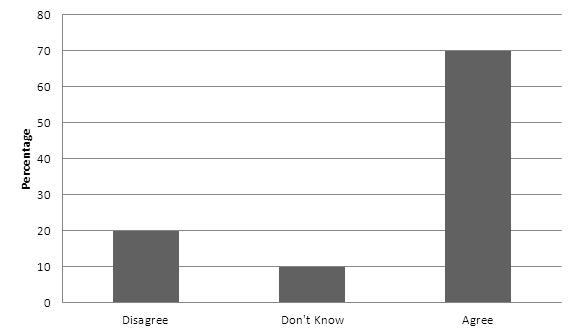

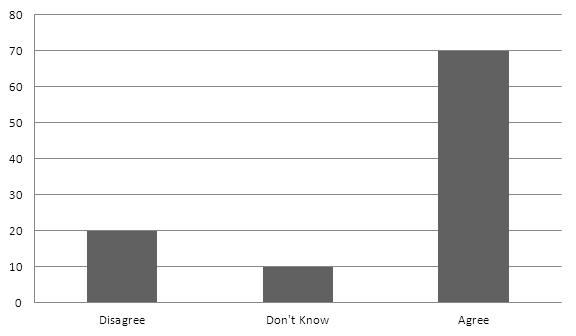

There is no question about it, if inclusion is going to be successful, from top to bottom; the leadership must believe in inclusion. In this section "educational leaders" is defined as school principal. School principals (n=10) were asked to respond to the survey statement (item # 14): "General educators and special educators integrate their efforts and their resources so that they work together as integral parts of a unified team", as indicated in Table 7 below, 20% indicated that they disagreed, 10% did not know and 70% agreed with the statement.

Table 7: Principals' responses to the statement: General educators and special educators integrate their efforts and their resources so that they work together as integral parts of a unified team. (n = 10)

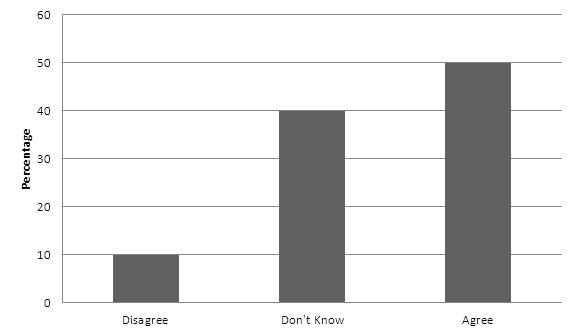

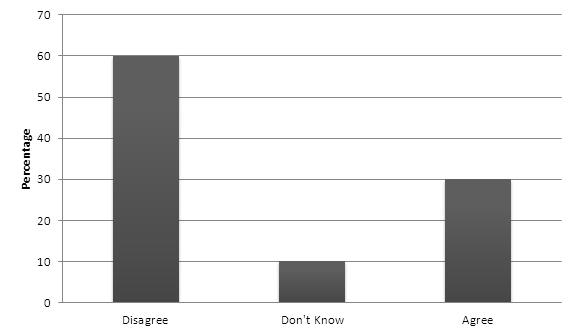

In response to item 15: "We give children with disabilities just as much of the full school curriculum as they can master, and modify it as necessary so that they can share elements of these experiences with their classmates," as shown in Table 8 below, results indicated that 10% disagreed, 40% did not know and 50% agreed with the statement.

Table 8: Principals' responses to the statement: We give children with disabilities just as much of the full school curriculum as they can master, and modify it as necessary so that they can share elements of these experiences with their classmates. (n = 10)

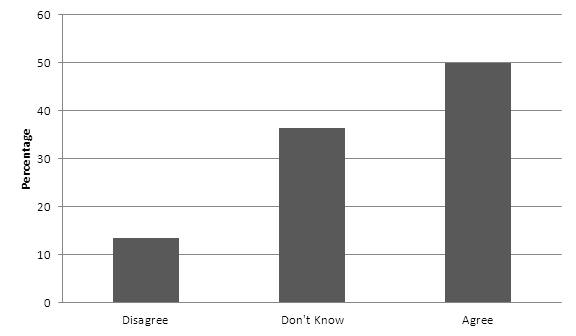

For item #17: "We make parents of children with disabilities fully a part of our school community so they also can experience a sense of belonging," as shown in Table 9 below 20% disagreed, 10% did not know, and 70% agreed with the statement.

Table 9: Principals' responses to the statement: We make parents of children with disabilities fully a part of our school community so they also can experience a sense of belonging. (n = 10)

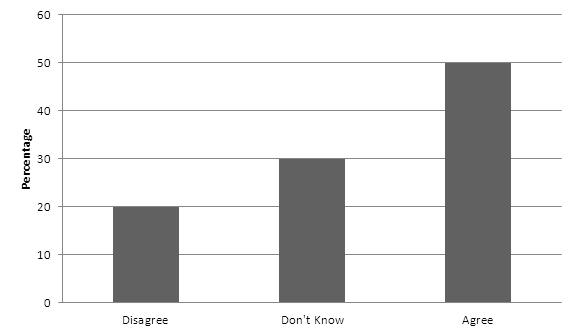

School principals also responded to item #19: "We individualize the instructional program for all the children whether or not they are disabled and provide the resources that each child needs to explore individual interests in the school environment." As the results in Table 10 below indicate, 60% disagreed, 10% did not know and 30% agreed with the statement.

Table 10: Principals' responses to the statement: We individualize the instructional program for all children whether or not they are disabled and provide the resources that each child needs to explore individual interests in the school environment. (n = 10)

In response to the statement "The principal understands the needs of students with disabilities and supports inclusionary practices," as indicated in Table 11 below, 50% agreed or strongly agree while 13.5% disagreed or strongly disagreed. Over thirty-six percent did not know one way or another.

Table 11: Responses to the statement: "The principal understands the needs of students with disabilities and supports inclusionary practices." (n = 304)

Although only half of the respondents view their principals as supportive; this is a trend that should be welcomed. When the leadership at the building level is supportive of inclusion, they are then able to present and advocate for the concept of inclusion to their faculty and staff. Inclusion becomes embedded in the school culture and climate. Teachers, both special education and general education, would feel supported and encouraged to try new ideas. These ideas are supported by the findings of a study conducted by Walter-Thomas (1997), in which schools where the principals were actively involved in the development of new special education services seemed to do better over time and principals performed multiple roles in establishing creditability of new special education services.

The last question under this category that was asked to educators in the Virgin Islands was whether we genuinely start from the premise that each child belongs in the classroom he or she would otherwise attend if not disabled. This is the most important question that summarizes the reasons behind this study. The law specifically authorizes that all children belong to the regular classrooms and learn with their peers. The phrase in the law, "To the maximum extent appropriate," also points out that there is an exception to the rule and that some students may benefit more by being in an exclusive environment. However, the proof of burden is in the hands of the school and not the parents.

As indicated in Table 12 below, when asked the above mentioned question, 50% of the participants agreed or strongly agreed. Yet, another 20% disagreed or strongly disagreed, while another 30% did not know, one way or another.

Table 12: Responses to the statement: We genuinely start from the premise (of least restricted environment) that each child belongs in the classroom he or she would otherwise attend if not disabled. (n = 550)

The philosophies of inclusion agree that students with disabilities should be in school with their peers in the age-appropriate general education classroom for some amount of time. The debate rages however, between inclusionist and full inclusionists, as to whether all students, regardless of disability, should or should not be in the general classroom all of the time and whether pulling students with disabilities from the general education classroom, to receive instruction or support specific to their disability, is counterproductive to the purposes of inclusion. This study will not resolve that issue. The results here however, showing that at least half of the respondents genuinely start from the premise that each child belongs in the classroom he or she would otherwise attend if not disabled, which is consistent with the law, are somewhat encouraging. They suggest there is a systemic change that is taking place in the United States Virgin Islands, although they have a long way to go.

It is important to note that no significant differences were found when crosstabs were generated for the seven attitudes and beliefs, services and physical accommodations and school support survey questions, based on school level (elementary, middle and high school) or school district (St. Thomas/St. John and St. St. Croix). Although the initial crosstabs revealed significant differences on one or two of the survey questions (1-7), further calculations indicated that the significant difference were one or two points off and the trends were pretty much the same. Readers should understand that most of the responses favored agreement with the survey questions. The only exception to this was on survey item 3:"school personnel are prepared to teach students with disabilities in the regular education setting", which results, as shown in Table 13 below, indicate that 57.5% of the respondents that took this survey disagreed with the statement.

Table 13: Responses to the statement: School personnel are prepared (professional development/other training) to teach students with disabilities in the regular education setting. (n = 567)

Lastly, crosstab results of this study, across all survey questions, revealed that the participants' responses were the same, except on the items indicated above. They agreed, disagreed or did not know, regardless of their demographics. Participants of this research all felt that the accommodations to the physical plant and equipment are not adequate to meet the needs of students with disabilities, nor were they sure if the related services for students with disabilities are available. It is important for readers of this article to understand that the significance of these results is that education leaders will be better able to troubleshoot areas of weakness and provide tailored professional development activities that will help to positively influence school personnel perception of inclusion and inclusive practices in the public schools. Education leaders and policy makers may want to place more emphasis on developing course modules, staff development and professional development, where all stakeholder groups can learn and understand the fundamentals of special education, the titles and roles of special education personnel and the role they play in academic success of students with disabilities.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion, education leaders and policy makers of public schools in the US Virgin Islands need to invest more resources into disability awareness education (Pivik, et al. 2002) and explicit professional development and training as to the whys and hows of inclusion for both special education and general education personnel, in an effort to enhance collaboration when working together and with children with disabilities and their caregivers. Along the same train of thought, the teachers in the Walther-Thomas (1997) study identified specific staff development topics, for their skill development, to include scheduling students, co-planning, co-teaching skills, writing Individualized Education Programs, for mainstream settings, and communicating more effectively to facilitate teamwork and collaboration.

It is believed that these same topics should be covered with school personnel in the US Virgin Islands, because the participants indicated that they too lack professional and staff development to increase their skills in inclusive development programs, like the participants of this study. It is recommended that interview sessions be conducted, based on school level, although no significant differences were indicated in this study, to gather the teachers' thoughts on areas of emphasis they feel should be covered that are appropriate for the school setting and school needs. Additionally, investments should be made in upgrading the physical structures and providing adequate equipment for these students, as well as the related services that are needed.

Recommendations for future research include a follow-up longitudinal study within five years to determine if the results of this data have been impacted or influenced significantly. It is also recommended that data be collected on the perception of children with disabilities enrolled in the public schools in the US Virgin Islands and their parents and/or caregivers, to determine if there are any perceived barriers and facilitators as they relate to the quality of inclusive education being provided in the US Virgin Islands.

References

- Connor, D.J., Gabel, S.L., Gallagher, D.J. and Morton, M. (2008) Disability studies and inclusive education - implications for theory, research and practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(5-6), 441-457.

- Connor, D. J., & Ferri, B. A. (2007). The conflict within: Resistance to inclusion and other paradoxes in special education. Disability & Society, 22(1), 63-77.

- Freagon, Sharon, & Others. (1993). Some answers for implementers to the most commonly asked questions regarding the inclusion of children with disabilities in general education. Springfield, IL: Illinois State Board of Education, Springfeld.

- Fuchs, D. & Fuchs, L.S. (1998): "Competing visions for educating students with disabilities: Inclusion vs. full inclusion." Childhood Education, 74.5 309-317.

- Goodlad, J. I., & Lovitt, T. C. (Eds.) (1993). Integrating general and special education.

- New York: Merrill.

- Hardman, M. & Dawson, S. (2008). The impact of federal and public policy on curriculum and instruction for student with disabilities in the general education classroom. Preventing School Failure. 52: 5-11.

- Irmsher, K. (1996). Inclusive education in practice. Eugene, OR: Oregon School Study Council. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 372 525).

- Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) 2004, 20 U.S.C 1400 et. seq (2004).

- Jones, Nadine et. al v. Government of the Virgin Islands. Civil No. 1984-47 Concent Decree (2007, February).

- Lipsky, D. K., & Gartner, A. (1997). Inclusion and school reform: Transforming America's classrooms. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

- Macciarola, F.J., Lipsky, D. K., & Gartner, A. (1995). The judicial system and equality of schooling. Fordham Urban Law Journal, 23(3), 567-606. The Berkeley Electronic Press. http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj

- Oakes, J. 1985. Keeping track: How schools structure inequality. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ogle, D., Pink, W., & Jones, B.F. (Eds.). (1990). Restructuring to promote learning in America's schools. Columbus, Ohio: Zaner Bloser.

- Pivik, et. al. (2002). Barriers and facilitators to inclusive education. Council for Exceptional Children.69:97-107

- Roblyer, M. D. (2002). Integrating educational technology into teaching. New Jersey: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

- Salend, S. J. (2001). Creating inclusive classrooms: Effective and reflective practices (4thed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

- Shanker, A. (1996, August 25). Ideology and common sense. The New York Times, p. E7.

- Staub, D., & Peck, C. A. (1994-1995). What are the outcomes for non-disabled students? Educational Leadership, 52(4), pp. 36-40.

- Subban, P. & Sharma, U. (2005). Understanding educator attitudes toward the implementation of inclusive education. Disability Studies Quarterly, 25(2). Retrieved from http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/545/722

- Top, B. (1996). Status of policies, procedures, and practices; State directors of special education perceptions regarding implementation of inclusion. Orange City, IA: Northwestern College, Department of Education.

- Walther-Thomas, C. (1997) Co-teaching experiences: the benefits and problems that teachers and principals report over time. Journal of Learning Disabilities.30: 395-407.

- Wheelock, A. (1992). Cross the tracks: How 'untracking' can save America's schools. New York: New Press.

- Will, M. (1986, November). Educating students with learning problems-a shared responsibility. Washington, DC: Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services.

- Wolery, M. & Wilbers, J.S. (Eds.) (1994). Including children with special needs in early childhood programs. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Attachment A: Survey Questions, Response Rates and Sample Demographics

| Survey Questions | SD | D | DK | A | SA | n | |

| Attitudes and Beliefs | |||||||

| 1. | The regular teacher believes that students with disabilities can succeed (successfully participate) in the regular education setting. [p < .05 on Position, School Level, Gender] | 70 12.5% |

160 28.5% |

99 17.6% |

177 31.6% |

55 9.8% |

561 |

| 2. | School personnel are committed to accepting responsibility for the learning outcomes of students with disabilities. | 43 7.8% |

105 19.0% |

136 24.5% |

195 35.2% |

75 13.5% |

554 |

| 3. | School personnel are prepared (professional development/other training) to teach students with disabilities in the regular education setting. [p < .05 on School Level] | 122 21.5% |

204 36.0% |

113 19.9% |

101 17.8% |

27 4.8% |

567 |

| 4. | Students in the general education setting are prepared to accept students with disabilities. [p < .05 on District] |

70 12.5% |

163 29.0% |

122 21.7% |

177 31.5% |

30 5.3% |

562 |

| 5. | General educators are committed to collaborative practice that will be required to help students with disabilities succeed. [p < .05 on Position] | 36 6.4% |

100 17.7% |

141 24.9% |

239 42.2% |

50 8.8% |

566 |

| 6. | Special educators are committed to collaborative practice that will be required to help students with disabilities succeed (successfully participate). [p < .05 on Position, School Level] | 27 4.9% |

53 9.5% |

115 20.7% |

270 48.6% |

90 16.2% |

555 |

| 7. | General educators are willing to make accommodations in order for students with disabilities to be included. [p < .05 on Position, Degree, District] | 36 6.5% |

88 15.8% |

133 23.9% |

247 44.4% |

52 9.4% |

556 |

| Services and Physical Accommodations | |||||||

| 8. | Accommodations to the physical plant and equipment are adequate to meet the students' needs. [p < .05 on Teacher Type] |

136 24.1% |

169 29.9% |

94 16.6% |

119 21.1% |

47 8.3% |

565 |

| 9. | Services needed by students are available (e.g., speech therapy, occupational therapy, adaptive physical education, etc.). [p < .05 on Teacher Type] | 96 17.1% |

152 27.1% |

134 23.9% |

141 25.2% |

37 6.6% |

560 |

| School Support | |||||||

| 10. | The principal understands the needs of students with disabilities and supports inclusionary practices. [p < .05 on District] |

16 5.3% |

25 8.2% |

111 36.5% |

113 37.2% |

39 12.8% |

304 |

| 11. | We genuinely start from the premise (of least restricted environment) that each child belongs in the classroom he or she would otherwise attend if not disabled. | 39 7.1% |

71 12.9% |

165 30.0% |

221 40.2% |

54 9.8% |

550 |

| 12. | Adequate staff development is available to ensure personnel are properly equipped with skills to work with students with disabilities. [p < .05 on Degree, Teacher Type, District] | 111 19.9% |

174 31.1% |

139 24.9% |

101 18.1% |

34 6.1% |

559 |

| 13. | Procedures for monitoring individual student's progress are in place. [p < .05 on Teacher Type] |

36 6.8% |

84 15.9% |

165 31.3% |

198 37.5% |

45 8.5% |

528 |

| 14. | General educators and special educators integrate their efforts and their resources so that they work together as integral parts of a unified team. [p < .05 on Position] | 46 8.3% |

104 18.8% |

127 23.0% |

228 41.3% |

47 8.5% |

552 |

| 15. | We give children with disabilities just as much of the full school curriculum as they can master and modify it as necessary so that they can share elements of these experiences with their classmates. [p < .05 on Position, District] |

29 5.2% |

61 11.0% |

133 23.9% |

272 48.8% |

62 11.1% |

557 |

| 16. | Students with disabilities are supportively included in as many school and district assessments as possible (with necessary modifications provided as needed). [p < .05 on Age] | 27 4.8% |

55 9.8% |

154 27.4% |

261 46.4% |

66 11.7% |

563 |

| 17. | We make parents of children with disabilities fully a part of our school community so they also can experience a sense of belonging. [p < .05 on Position, Teacher Type] | 24 4.3% |

67 12.0% |

158 28.2% |

246 43.9% |

65 11.6% |

560 |

| 18. | We actively encourage the full participation of children with disabilities in the life of our school including co-curricular and extracurricular activities. [p < .05 on Years Experience] | 21 3.8% |

69 12.3% |

141 25.2% |

237 42.4% |

91 16.3% |

559 |

| 19. | We individualize the instructional program for all the children whether or not they are disabled and provide the resources that each child needs to explore individual interests in the school environment. [p < .05 on Position, School Level, Degree, Age] |

34 6.1% |

106 19.1% |

121 21.8% |

239 43.1% |

55 9.9% |

555 |

| 20. | Adequate numbers of personnel, including aides and support personnel, are available to support inclusionary practices. [p < .05 on Position] | 73 24.5% |

89 29.9% |

67 22.5% |

58 19.5% |

11 3.7% |

298 |

| 21. | Teaming approaches are used for problem solving and program implementation. [p < .05 on Position, Degree] |

19 7.6% |

37 14.9% |

77 30.9% |

92 36.9% |

24 9.6% |

249 |

| Biographical Information | |||||||

| |

Response Categories vary according to Item (indicated with items below). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 22. | Position: (1) principal; (2) teacher; (3) school psychologist; (4) counselor; (5) other (including paraprofessional) | 10 1.8% |

439 80.7% |

8 1.5% |

6 1.1% |

81 14.9% |

544 |

| 23. | School Level: (1) elementary; (2) middle/junior high; (3) high school |

378 69.9% |

85 15.7% |

78 14.4% |

|

|

541 |

| 24. | Degree earned: (1) AA; (2) BA; (3) MA; (4) Ed.Sp./Advanced Diploma; (5) PhD/Ed.D |

27 5.4% |

273 54.3% |

181 36.0% |

12 2.4% |

10 2.0% |

503 |

| 25. | Teacher Type: (1) regular education teacher; (2) special education teacher; (3) vocational teacher; (4) other | 346 65.2% |

47 8.9% |

25 4.7% |

113 21.3% |

|

531 |

| 26. | Years of Experience: (1) 0-4; (2) 5-10; (3) 11-15; (4) 16-20; (5) 21 and over |

71 12.9% |

145 26.4% |

65 11.8% |

71 12.9% |

197 35.9% |

|

| 27. | (Your) age: (1) 20-30; (2) 31-40; (3) 41-50; (4) 51 and over |

79 14.6% |

141 26.1% |

163 30.2% |

157 29.1% |

|

540 |

| 28. | Gender: (1) male; (2) female |

69 12.7% |

475 87.3% |

|

|

|

544 |

| 29. | School District: (1) St. Thomas/St. John; (2) St. Croix |

224 39.0% |

351 61.0% |

|

|

|

575 N |

Chi-square tests of independence were calculated on each Survey Question (items 1-21) by Biographical Information (items 22-29). Statistically significant conjoins [p < .05] are indicated above.