The compelling role that art plays in managing emotions and healing is well documented in disability research (Ainsworth-Vaughn, 1998; Corbett, 1999; Al Zidjaly, 2005, 2007). The strategic role that art can play in combating social exclusion and inciting societal change, however, is under-examined. This article extends recent developments in multimodality that build on mediated discourse analysis (Scollon, 2001) to fill this gap. It demonstrates how a person with a disability from the Islamic Arab country Oman, where the outdated medical model of disability still prevails, strategically uses a semiotic resource (Microsoft PowerPoint) to create mediated actions (animated music videos) that manage interpersonal and social exclusion. I specifically focus on how Yahya creatively draws on various cultural customs in making these music videos. I also show how this plays a role in not only alleviating disability's effect on Yahya's social life, but also in leading to wider social change. In viewing art as a form of mediated action, this study has far-reaching consequences for both disability and multimodality studies—in particular, regarding the various multimodal ways through which exclusion can be managed. The study also contributes to our understanding of disability and its relationship to art and technology in a non-Western culture.

Introduction

Exclusion or social isolation—the major predicament facing people with disabilities—is widely recognized in disability studies. However, with very few exceptions (e.g., Everts, 2004; Al Zidjaly, 2005; 2006; 2007; 2009), a close examination of specific interactive practices through which inclusion and exclusion are constructed, especially where technology is an issue, is almost nonexistent. In addition, the existing sociological research that addresses the experience of isolation in the lives of those with disabilities (Goffman, 1963; Murphy, 1990; Robillard, 1999) is not only outdated; but also, it perpetuates a passive image of individuals with disabilities in managing such an experience. Contrary to such depictions, which represent withdrawal, marginalization and isolation as inevitable outcomes of quadriplegia, in this paper, I investigate how a quadriplegic man (Yahya) from the Islamic Arab country of Oman strategically uses a semiotic resource (Microsoft PowerPoint) to create actions (animated music videos) that influence the behaviors of his interlocutors and, in turn, manage his disability. What is especially creative about these videos is that in making them, Yahya draws on the genre of "greeting cards," a powerful cultural tradition in Oman (and elsewhere in the world). He also draws on a strategy that creates a culturally-tied pattern of interaction called "getting the lower hand" (Beeman, 1986), where a person presents himself or herself as requiring protection, thus, obligating the other to protect him or her. These collective actions, which are made possible by a technological artifact and which integrate cultural norms, in turn generate social inclusion and alter the course of Yahya's life in dramatic and unexpected ways.

The videos analyzed in this paper were collected as part of a larger project (Al Zidjaly, 2005) for which I, as Yahya's friend and sometimes caregiver, video- and audio-taped Yahya's everyday interaction, in addition to engaging in participant-observation with Yahya and his primary caregivers for more than nine months. The purpose of the study was to examine how Yahya, as a quadriplegic man, who is largely considered helpless by his society's standards, exercised agency, particularly through the use of technology. Additional videos Yahya created were collected at different intervals during 2007, 2009, and 2011. In this article, I extend my previous research (Al Zidjaly, 2011) by conceptualizing art (in this case, artistic animated music videos that have greeting-card-like forms) beyond being mere tools for expression and healing. Instead, In this study, I employ mediated discourse analysis (Scollon, 2001), a theory that takes as its unit of analysis the moments that social actors take actions, to explore Yahya's art as mediated actions. This theory suggests that actions are always social (by communicating identities), and are carried out by agents through mediational means (by technology, in this case) to achieve intended outcomes (in this case, combating interpersonal and broader societal exclusion). My analysis demonstrates how Yahya's animated music videos enable him to manage a widely realized predicament regarding disability; they allow him to become an active participant in his community and to construct an agentive identity—the identity of a person who is capable of doing things believed impossible for him to do. This approach not only highlights the power in any form of artistic expression, but also gives an accurate picture of how art and technology (the music videos analyzed in the paper are made through a technological artifact) in actuality help manage disability and even create personal and social change.

The next section of the paper details the relationship of the academic fields of multimodality and disability, especially as related to the role that art and technology can play in alleviating disability. This is followed by a brief description of the disability situation in Oman and a synopsis of Yahya's story—in particular, his introduction to and use of Microsoft PowerPoint software. The analysis is divided in two parts, each illustrating through specific examples how Yahya exercises agency by creating animated music videos that combat being excluded from (1) the social events of his large extended family and community and (2) the right to hire his own female resident assistant (a right previously reserved for married 'normal' couples in Oman). The concluding remarks suggest the necessity for a sociocultural model of disability to go beyond conceptualizing art as just a tool for healing or representation into investigating how these texts are used in real life as actions to achieve certain goals and outcomes—that is, how they integrate with the social milieu in which they exist. Doing so has consequences for disability studies, a field that has long identified the crucial role that art and technology alike can play in alleviating disability.

Multimodality and Disability

Multimodality, a relatively new analytical framework created to analyze complex, multimodal discourses that draw upon or consist of various visual and textual modes (Iedema, 2003), has recently been brought together with disability studies in the social sciences. This was an inevitable and natural outcome given the crucial role artistic expression and technology alike can play in healing and creating access to worlds that are otherwise unavailable. Further, as linguistics and communication studies came to embrace the fact that people, especially those with certain disabilities, draw upon various modes other than and beyond just language to communicate, it became clear that multimodal forms of expression require multimodal analytical approaches. Joining multimodality and disability studies propitiously has helped correct to a certain degree the erroneous misrepresentation of social isolation as an inevitable—and inescapable—outcome of quadriplegia. Examining the construction of the social reality of disability from a multimodal perspective has enabled researchers to begin to uncover the active role that those with disabilities can play in relation to technology and art, the two major areas where multimodality and disability have been interlinked.

Various approaches to multimodal texts have been proposed over the years. Some use little or no contextual information (e.g., content analysis approaches), while others advocate grounding multimodal discourses in the social milieu in which they exist (e.g., anthropological and cultural approaches). This latter approach, which is key to the argument in this paper, has recently been developed into what came to be known as the dynamic approach towards multimodal texts and practices. The underlying proposition in this dynamic approach is that tools of communication need to be studied in the context of their situated use by social actors (Jones, 2005). In these frameworks, visual analysis is not only a matter of analyzing images per se, as it has been the case in earlier models of multimodality (e.g., Kress & van Leeuwin, 1996, 2001); it is a matter of analyzing them in their socially specific and multimodal contexts. Pioneers of such an approach are Goodwin (1995, 2001) and Iedema (2001, 2003), who demonstrate how dynamic social practices unfold and meanings transform from one semiotic mode into another in interactions where non-verbal communication (such as gaze, gesture, images and so on) plays a role. Taking a mediated discourse analysis (Scollon, 2001) perspective, Scollon and Scollon (2003) further develop this dynamic approach to communication by arguing that the true meaning of public discourses such road signs and brand logos can only be understood by considering the social and physical world in which they are placed. In Al Zidjaly (2011), I extend the argument that multimodal texts must be contextualized to disability studies. Through examining the cover and contents of ten volumes of Challenge, the main disability magazine in Oman, I argue that full realization of the power that can reside in images of disability can only be achieved through focusing on what images or visual texts mean to their users and how they matter to the people they address—the disabled population in Oman.

The first area that provides background to my analysis examines the relationship of technology and artist expression. That any form of expression, from painting to poetry, self-empowers through enabling expression of emotions and, in consequence, healing one's damaged self is an adage in the literature on disability and artistic expression (Al Zidjaly, 2005; 2007; Ainsworth-Vaughn, 1998; Corbett, 1999). In fact, art was a major catalyst in shifting the outdated view of disability as a medical problem to a social problem, as the work of Lewis (2000) demonstrated. However, most research in disability studies, just like earlier multimodal frameworks themselves, dedicates itself to examining visual art as decontextualized tools for self-expression (e.g., Diem-Wille, 2001) or representation (e.g., Crutchfield & Epstein, 2000; Halifax, 2009). Some recent research that deals with the interplay between art and disability from a multimodal perspective, however, moves beyond conceptualizing multimodal texts as simply mediums of representation or of expressing visually what one is inhibited from expressing verbally, to seeing them as communicative actions for self-empowerment, especially in educational settings (e.g., Wexler & Cardinal, 2009). This is in line with current dynamic multimodal research that centralizes the interplay between images and texts (Jones, 2005) and the need to consider the role of individual active agents in making art works by integrating visual texts in real life practices (Al Zidjaly, 2011). In this analysis, I propel this research trajectory forward by highlighting the need to examine how visual texts are used to accomplish specific goals pertaining to overcoming social isolation. This gives a richer understanding of the full potential of artistic work by people with disabilities.

A related body of research that also provides background to my analysis investigates the relationship of new media technology to disability. Some scholars suggest that new media technology alleviates disability through masking disability, equalizing power, and creating independence (e.g., Ford 2001; Grimaldi & Goette, 1999; Sproull & Kiesler, 1986). Others, however, are skeptical, arguing that, in some cases, technology can even create disability (e.g., Seymor and Lupton, 2004; Goggin & Newell, 2003; Kaye, 2000). In Al Zidjaly (2005), I note that most of this research, however, merely speculates about the beneficial or ineffectual role that technology plays in the lives of those with disabilities. To understand the exact relationship between technology and disability, I argue, it is critical to identify specific technology-related actions that people with disabilities recognize as being of use to them personally, using the framework of mediated discourse analysis (Scollon, 2001), which focuses on the actions that people take at specific moments. Only then can one get a precise picture of the interrelationship between technology and disability. In Al Zidjaly (2007), I do exactly that as I examine music videos created by Yahya using Microsoft PowerPoint software as tools of agency via self-expression and defiance of oppressive societal beliefs surrounding disability. In this paper, I go one step further by demonstrating how visual texts can be mediated actions that at times are strategically used to arrive at intended outcomes. This dynamic approach towards multimodal artistic texts has consequences for disability studies because it sheds light on a crucial topic of study in recent disability studies research: technology and agency. In other words, it extends our understanding of art and technology as therapeutic to art and technology as agentive and productive.

Background to Data

The Statute Law of Oman—an Islamic, Arabian country located in the North East of the Arabian Peninsula—advocates justice and equality for all in terms of rights and responsibilities. This signals that the government of Oman takes the issue of promoting and protecting human rights very seriously. This also is evidenced by the country's ratification in 2008 of the United Nation's Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities as well as its promulgation by Royal Decree No. 63/2008 its own Care and Rehabilitation Law for People with Disabilities. This law, which is the first of its kind in the country, ensures the rights of persons with disabilities and works to regulate, organize, and improve the services provided to them. Accordingly, these Omani laws and decrees acknowledge first and foremost that disability is a social problem—not just a medical predicament—and that people with disabilities constitute a foundational part of a society's economic, social, health and educational sectors. Hence, societal and psychological obstacles and stigma are to be removed to enable the process of inclusion. In reality, however, the antiquated medical model of disability prevails and, as a consequence, people with disabilities in Oman continue to be stigmatized, pushed to the periphery and sheltered due to outdated societal misconceptions of disability that equate those with disabilities with deviance and worthlessness. Thus, despite providing accessibility measures, rehabilitation centers and health and educational benefits, the Omani government's contribution to public awareness and services provided is deemed limited. That is, despite its belief that disability is socially produced, the Omani government has not yet succeeded in implementing this belief in the wider Omani society, judging by the situation of disability in Oman (Al Zidjaly, 2011).

Against this backdrop, in 2005, I initiated a multimodal case-study project examining how one particular person with a disability in Oman, Yahya, deals with the question of inclusion on a day-to-day basis through discourse and technology. Yahya was in a life-altering car accident in 1988 that left him quadriplegic. Despite being confined to a hospital bed and being unable to feed, dress or move himself, Yahya is able to use a personal computer by typing with the knuckle of his right hand. The project included videotaping and audio-taping everyday interactions between Yahya and his family, as well as engaging in participant-observation with Yahya and his primary caregivers over the course of nine months and seventeen days. This was facilitated by my friendship with Yahya dating back to 1994. The data collection also consisted of observing Yahya's computer-related practices, which resulted in collecting many of the videos analyzed in this paper. Over the next five years, I continued collecting the animated music videos Yahya made and sent to me, as his friend, and to many other friends and family members. When I first started observing Yahya, my objective was to elucidate the vital role that the Internet plays in enabling Yahya to overcome his limitations as an individual with a disability living in a society that conceives of him as wholly dependent. What I discovered as I collected data, was that Yahya's agency was enhanced not only by the content of his e-mails to friends or messages posted to online chat rooms, but also by the emergent practices he created as tools for self-empowerment. Therefore, it was mainly Yahya's use of the computer itself (for example, using non-Internet software programs such as Microsoft PowerPoint) that have had a continuing and positive effect on his self- empowerment.

One of these emergent practices was Yahya's use of the software Microsoft PowerPoint to create personal animated videos; this is the topic of the analysis that follows. Yahya started this activity approximately two months after purchasing his first personal computer and installing the Microsoft Office software in the summer of 2001. The Microsoft Corporation created PowerPoint to help business people and academics create professional presentations. Although Yahya was unemployed and had no need to create professional presentations, he did not discard the software. Instead, he utilized the well-known tool to initiate a new practice of making music videos composed of verbal and visual slides that originally either told a story or expressed his stance toward diverse events in his life. The target audience for these videos is comprised of Yahya's extended family members (he shares a house with many of them, including his parents, as is common in Oman) and friends who either receive them from Yahya via e-mail or view the videos in the form of wall posters that hang in Yahya's room. Elsewhere (Al Zidjaly, 2007, 2005), I demonstrate how such videos allow Yahya to make sense of his past and present and also provide a forum in which he can express himself and critique his family and the society in which he lives. Using Microsoft PowerPoint this way provides Yahya with an outlet for alleviating his disability and healing himself. These findings are congruent with mainstream disability research. Here, I conceptualize such videos as mediated actions carried out by Yahya for specific purposes.

Managing Exclusion through Microsoft PowerPoint

It is commonly recognized in disability research that as people's physical abilities gradually deteriorate, they often experience exclusion not only from social participation but also from conversational interactions (Goffman, 1963; Murphy, 1990; Robillard, 1999). However, this view is outdated. In this section, I demonstrate how Yahya makes videos that are deliberately intended as strategic actions to help implement his agenda. Specifically, they are intended to combat (1) being excluded from familial and general social events and (2) being denied the right to hire his own female resident assistant to care for him (a right previously reserved for married "normal" couples in Oman). My analysis illustrates how this particular semiotic resource (Microsoft PowerPoint) enables a person with a disability to manage a widely realized predicament regarding disability (exclusion) by allowing him to become an active participant in his community, construct an agentive identity—the identity of a person able to do things believed impossible for him to do, and direct the actions of his primary caregivers. This analysis focuses specifically on a subset of the videos Yahya has made over the last ten years. Videos that accomplish this function often closely align with traditional greeting cards and/or create a pattern known as "getting the lower hand" (Beeman, 1986). In drawing upon such cultural customs, he makes sure that they are culturally acceptable.

Actions that Manage Interpersonal Exclusion

In the early stages of being introduced to Microsoft PowerPoint, Yahya's main objective in making animated music videos was not to change the dominant idea that disability means powerlessness, or to promote a social cause, but rather, to showcase his capabilities (establish competence) and, in so doing, create involvement with his immediate family. As Yahya explained in an interview I conducted with him in 2007, over the years, he has experienced what many other quadriplegic people have, which is the slow and gradual process of finding himself being side-lined to the periphery of social engagements by his immediate family, albeit unintentionally. This was due to many practical reasons, mostly the effort it takes to take a quadriplegic man out, and the lack of ramps in so many places in Oman, especially in the early 2000s. Thus, through creating animated music videos, Yahya decides to combat marginalization in his immediate surroundings and exhibit his competence to those around him. (His family members knew little about computers at this time and he had more computer knowledge than I did, although I am an academic). Making such videos did, in fact, succeed in making Yahya's close circle take notice of him for the first time in a long time, and in a new way. An example of such an action is Video 1, Yahya's first ever animated music video. Note that although Yahya's native language is Arabic, he is fluent in English (the second official language of the country). Hence, Yahya's videos usually are written in Arabic or English. Also, Bel, a contracted form of Al Belushi (Yahya's last name), is one of Yahya's online nicknames.

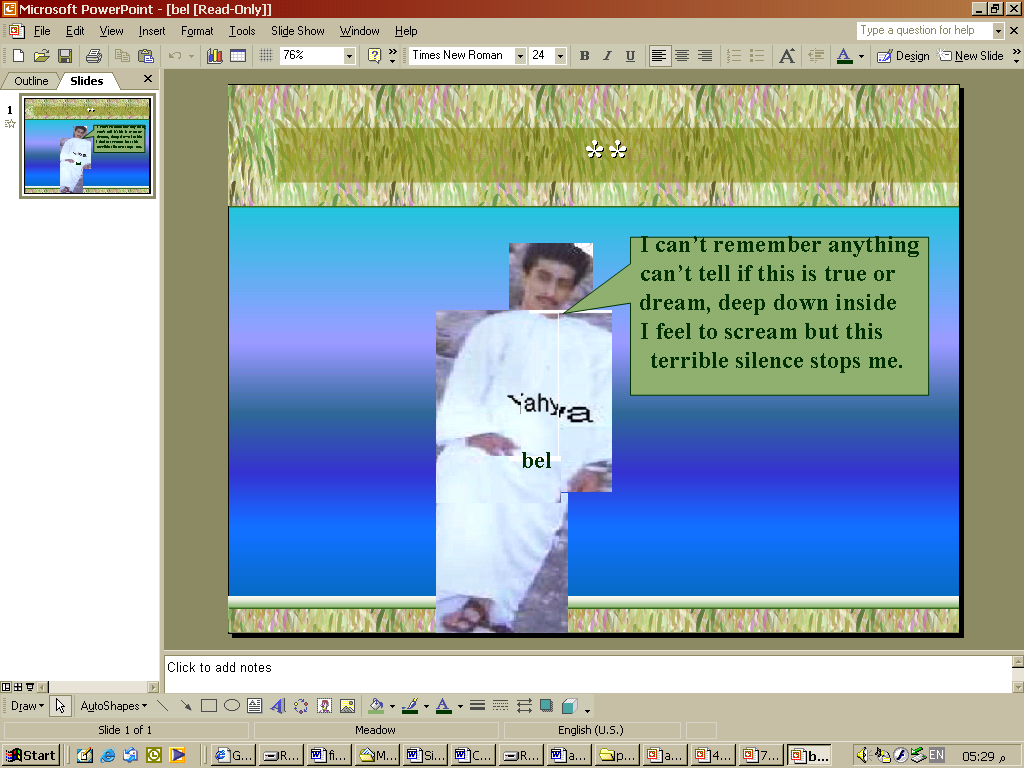

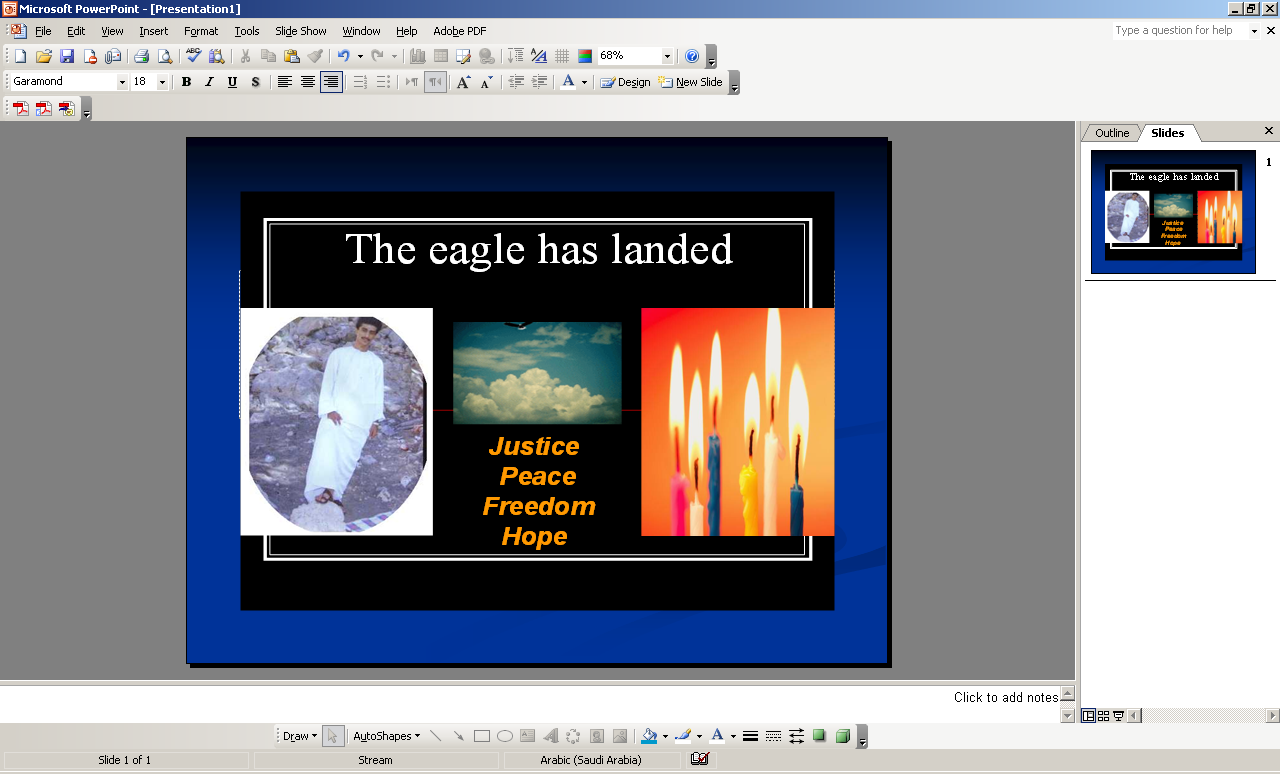

Video 1: Establishing Competence

Video 1 was created in 2002 and was sent by Yahya to all his friends and family members who happened to have access to personal computers at the time. The video interestingly enough presents the only picture available from his past that shows Yahya standing up. At one level, Yahya's first video does considerably express his feelings about the life-altering car accident he endured ten years prior; it does depict the effect his disability has had on his self-image. This is indicated by the distorted design of the video that clearly reflects the impact Yahya's car accident has had on him as a young man: He feels distorted and unable to understand his predicament. To express his feelings that his body is altered beyond words, Yahya cuts his picture from the past into six pieces and then cobbles them together into a misconstrued shape. This animation of himself then "sings" a portion of the song One by the American rock band Metallica. One presents the narrative of a World War II veteran who has lost all his limbs and senses in the war; yet, he was kept alive against his wishes. The fact that the chorus of One consists of the lyrics (Oh, please God take me) is not so much a wish for death, as Yahya has later explained to me, but rather a cry for help. This cry did indeed reach his family and friends who were startled by the video's message and captivated simultaneously by the visual communication of the daily pain Yahya endures. In addition, something else captured the attention of the family: the complexity of the design and animation of the music video.

In a playback session (Tannen, 2005) I conducted with him as part of the original 2005 project, Yahya explained that his sole, original purpose of making this first video was to demonstrate his expertise in maneuvering PowerPoint to everyone around him (and especially to working members of his family); it was his attempt to combat social exclusion. Indeed, Yahya's audience was intrigued by his technological capabilities, especially since none of his friends or family knew much about PowerPoint at the time. Therefore, Video 1 did succeed in creating communication between Yahya and his family and in altering ever so slightly their view of Yahya. Instead of perceiving him as dependent, they started flooding him with their PowerPoint needs. In short, over the years, Yahya has become the PowerPoint laureate of the family: He has become the go-to guy for creating professional presentations and even conducts classes in using PowerPoint for children in the family. Hence, Video 1 helped Yahya "pass" as normal, which according to sociologist Goffman (1963), is one of the main plights of those with disabilities. It showed those around him that disability does not translate into uselessness and that they have much to learn from their quadriplegic friend and family member. This first video and the subsequent ones, thus, acted as a refusal to give into personal and familial exclusion. It was an inventive way to do something about being excluded that was made possible by Microsoft PowerPoint software (though through Yahya's work and creativity).

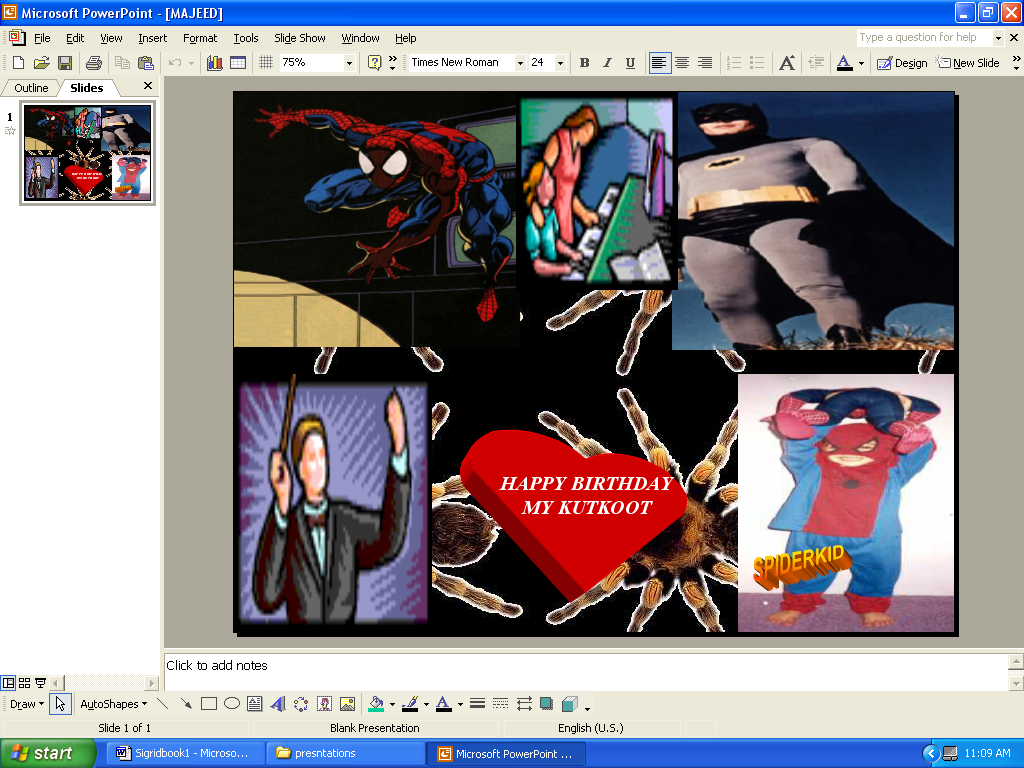

While all of Yahya's animated music videos are intriguingly complex design-wise, once he made his mark as a capable technological expert—not just in terms of making videos but also regarding in computers all around—Yahya started using his self-created videos to combat being excluded from social participation—first in family-related events and later in wider social circles. He did so by making videos that resemble greeting cards in order to create belonging. Because of his status as a quadriplegic man living in Oman, Yahya in most cases is incapable of independently carrying on numerous types of actions such as buying his own greeting cards, which Omanis like to frequently exchange, or taking his nephews out for their birthdays. This results in him being deprived from participating in many family occasions. Instead of giving in to social exclusion, however, he found a way to play around it using technology as a tool to make animated greeting videos that appeal to children and adults alike that end-up guaranteeing him participation in family events. For instance, Video 2, which was made in 2007, is an animated birthday video centered on the theme of Spiderman and Batman, the focus of his four-year-old nephew's fascination at the time. Both Yahya and his nephew are represented in this animated video. The video is accompanied by Yahya's voice singing a happy birthday tune in Arabic, while the design of the video includes a picture of the nephew in a Spiderman costume (lower right). This specially designed music video greatly appealed to his nephew and allowed Yahya to not only participate actively in the nephew's birthday celebration (the nephew and his parents came by to visit after the celebration was over), but also helped the nephew see Yahya as capable of doing creative actions that not even his parents are capable of.

Video 2: Happy Birthday

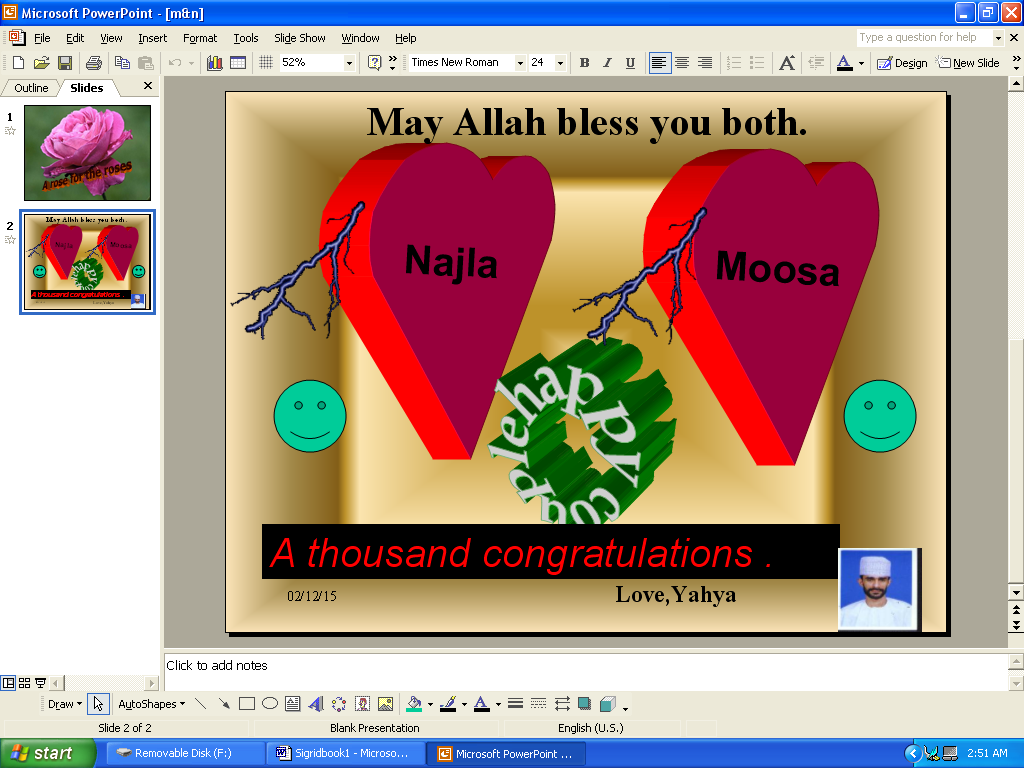

The same is true for the third video in this section, which Yahya created as a greeting card for one of his sisters and her husband for their first anniversary. Because of his family's lack of motivation and lack of accessible facilities, Yahya was unable to go out to celebrate with them. Rather than give in, however, he created a personalized and animated greeting card for the couple using symbols typical of anniversary greeting cards (flowers and hearts), while simultaneously employing traditional greetings norms to appeal to his sister and her husband who are religiously conservative. Thus, he opted to use smiley faces instead of their pictures (religious and cultural norms in Oman discourage using personal photographs publicly), as well as drawing upon religious congratulatory phrases, thereby, showing cultural sensitivity. This, once again, allowed him to participate (Yahya, who is not very traditional, even includes a picture of himself [lower right] in the greeting card) and be an agent at the same time. These actions were appreciated by all and did succeed in making Yahya a crucial participant in all family occasions, despite the obstacles and orthodox ideas surrounding him as a quadriplegic man living in Oman. As time went by, Yahya's videos persuaded the family on many occasions to choose his room instead of going out as a venue to celebrate, especially children's birthdays and anniversaries, where they can gather together as a family and watch the videos made by him.

Video 3: Happy Anniversary

Once Yahya managed to combat familial exclusion, he started making videos that create engagement not just with immediate family but also friends. This coincided with Yahya's active involvement in online political, religious and spiritual chatrooms, which reflect his personal interests. Such online activity gave him a chance to engage in a multitude of various discourses, in addition to widening his social circles. In turn, this allowed him to take an active part in his community by discussing world events. To create more involvement with his newly acquired online friends, especially Omanis whom he could not go out and meet with in cafes as other Omanis who meet online do, he started making personalized animated greeting videos that are sent to them during personal celebrations or holiday seasons. One example is Video 4, which is a New Year's greeting video that was made on New Year's Eve of 2011. In this video, Yahya again draws on cultural discourses that include Islamic religious greetings in addition to wishing happiness—not just to friends, but also their families, which is typical of Omani greetings that are always collective (i.e., include family). His friends were in awe of the "live" firework show and also appreciated the personalized nature of the card (Yahya recorded a personalized blessing in his own voice).

Video 4: Happy New Year

To ensure constant involvement, especially with the larger community (his online Omani and non-Omani friends), Yahya then put a personal twist on a prevalent cultural activity: That of sending religious messages to friends and family to save souls. Thus, besides making personalized greeting videos such as Video 4, Yahya partakes in an established cultural practice whereby Omanis exchange religious messages via email, usually made by anonymous people. However, Yahya's videos are unique in the sense that rather than representing mainstream religious views, they feature more humanitarian, philosophical and spiritual views of life and the afterlife. In addition, unlike the videos usually exchanged by Omanis, Yahya's identity as the maker of the videos is known. This action started when Yahya found himself, just like many other men and women across Arabia, intrigued by world affairs concerning the Middle East. This led him to study the main religions of the world (Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism and Hinduism), resulting in Yahya acquiring a more fresh perspective on the nature of life and God. Consequently, his academic venture made him a more prominent figure in various religious chatrooms and eventually partake in creating a new religious Islamic identity called "the enlightener," whose job is to explain the true essence of Islam and other world religions to Muslims (Al Zidjlay, 2010). This pursuit of religious knowledge also paid off in a different way: He started making videos in which he shares these fresh perspectives with those around him. Because of the interesting and thought-provoking nature of his videos, they get to be circulated by friends and family members to co-workers, guaranteeing Yahya involvement in wider social circles. Video 5, the last video in this section, is an example of such videos. In it, Yahya explains in his recorded voice the message behind the video: That justice is the foundation of a good life because God is Just.

Video 5: God is Just

The first noticeable thing about video 5 is that it includes an animated movie of a hawk flying, which is Yahya's newly acquired symbol that accompanies most of his recent videos as a means of signaling perseverance, wisdom, and freedom. He adapted this symbol immediately after he survived some personal hardships, including his younger brother's untimely death and both his parents falling seriously ill. As for the video itself, as Yahya explains in the attached audio-tape, it is about the makings of a good life: that it all starts with justice because God is just. Through justice, peace can be achieved, which leads to the ultimate goal of all (especially those with disabilities)—freedom of thought and action. Once that is in place, then hope can flourish, and with hope, one can move mountains. What is most striking about this particular video—besides the call for justice and the prevalence of hope—is the accompanying music that plays as the background music to the audio-message: an instrumental version of the song, "The Day that Never Comes," by the American rock band Metallica. The song revolves around the idea of awaiting for the light at the end of a tunnel; it is about not losing hope, even when it looks like the sun will never shine, which is also accentuated by the flaming candles that twirl in the actual video. This video, thus, is a message of seeking hope wherever one can find it and not giving up despite constant obstacles. This is Yahya's philosophy of life. Because of the thought-provoking nature of such videos, they work to keep the line of dialogue open with family and friends leading to numerous engaging discussions that guarantee Yahya as the focus of interactions. In addition, such actions not only signal strength and understanding but also place Yahya, a quadriplegic man who lives in a society that still struggles with the basic idea of inclusion, as the wise man whom family and friends (online and offline) go to for advice or profound discussions, guaranteeing him constant involvement in his social circles.

Creating Actions that Combat Social Exclusion

Besides creating actions that enable him to connect to —and help create—his social world, Yahya makes music videos at times to implement his personal agenda. Yahya's car accident rendered him unable to perform many tasks. Caring for him became a full-time job—one that even his sisters and I together could not manage. Therefore, he has required an in-home personal nursing assistant since 1988. It was necessary for this assistant to be female, as Islamic culture (practiced by Yahya's family and most Omani people) discourage its members from hosting foreign men in their homes. Further, it was imperative to hire a foreign assistant through the Ministry of Manpower because no female Omani resident assistants were available. Hiring a foreign assistant usually requires a special permit that typically is available only to married couples because cultural customs discourage assigning female assistants to houses with young unmarried men. Thus, until 2002, Yahya was dependent upon his parents and married sisters for securing the special permits and hiring and retaining his resident helpers. This made Yahya highly dependent on his family for his basic survival. However, in the late 1990s, several family feuds ensued over his assistants and many were fired by his parents. This prompted Yahya to move out of his parents' house and take an unprecedented action during the summer of 2002: Yahya sought to become the first unmarried quadriplegic man in Oman to have a foreign resident assistant permit. This action challenged laws and customs and also was an attempt to end his dependency on his family.

Because the special permit is reserved for married couples only, getting an exception to the government rule required not only large amounts of paperwork, but also a plethora of meetings with numerous bureaucratic officials, ranging from the Mayor of Yahya's hometown, to the governor (among many other officials), to the Omani Minister of Manpower and Minister of Social Development. Though Yahya was able to do most of the work that went into receiving a government exemption, such as writing multiple letters, he needed a spokesperson who would physically take these letters to the various government agencies. (At the time, none of the government agencies was accessible to people in wheelchairs.) Besides, had Yahya gone himself, he would have required at least two people to go with him. Thus, given the practical difficulties of the task, Yahya turned to me to help him in what I understood at the time as the impossible mission: To assist him in fulfilling his dream of finally being independent as far as assistants were concerned. However, due to the vast amount of paperwork and the large number of bureaucratic steps involved (especially since at the time there existed no laws regarding disability in Oman), I declined his request. His sisters declined as well.

However, Yahya was adamant that he needed control over this vital aspect of his life as a person with a disability. Rather than give in, he turned to an ingenious strategy to get what he wanted: He launched a creative take on a widely practiced cultural strategy in the Islamic, Arabian culture where an agent from a lower position places himself or herself at the mercy of a person from a higher position to get what one wants. The person in the higher position usually finds him or herself in a state where he or she cannot refuse the lower person and, as a consequence, gives in to the request. Thus, by putting oneself down, one actually gains power over the person of a higher position. This widely documented strategy is referred to in the literature on Arabian/Islamic cultures as 'getting the lower hand' (Beeman, 1986) and/or 'evoking the protector schema' (Tannen, 1994). In past research (Al Zidjaly, 2006), I focus on how Yahya verbally performs this strategy to incite others to help him. However, he also uses multimodality—his music videos. Thus, in this section, I demonstrate how Yahya uses videos to position himself as helpless and, thereby, tries to change my mind and assist him in this difficult task. The following two videos (of five I analyze in this section) were sent to me the night I rejected Yahya's request to become his spokesperson in his "mission impossible." These two videos are a far cry from the "greeting card" videos examined in the previous section.

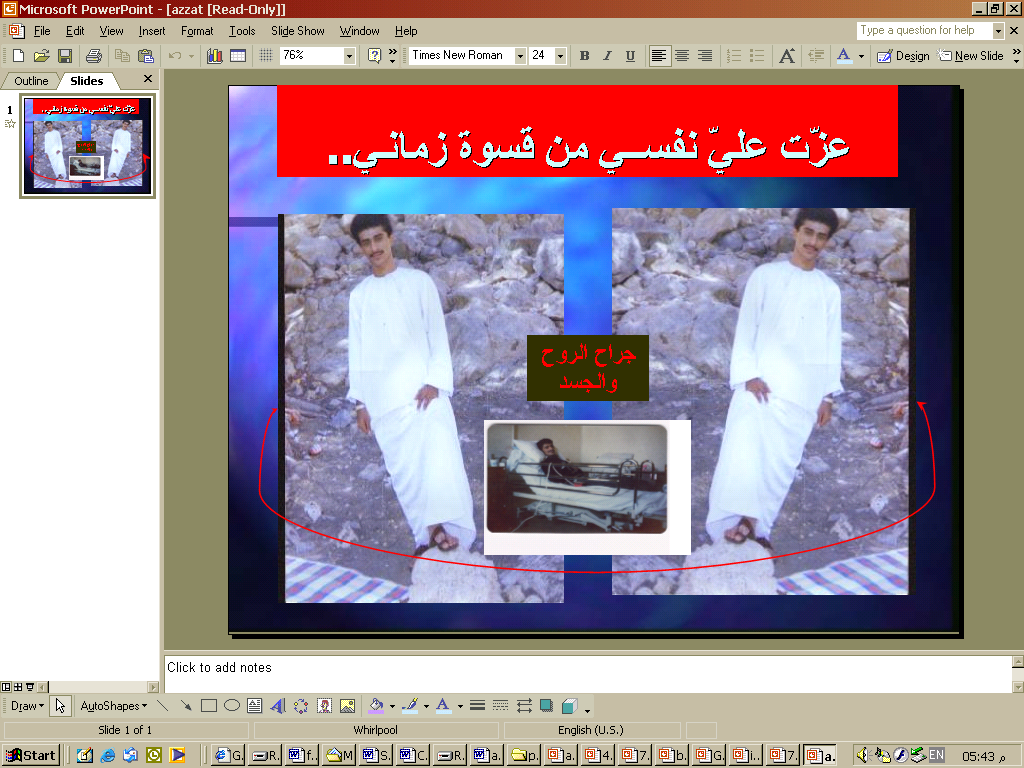

Video 6: Body and Mind Wounds

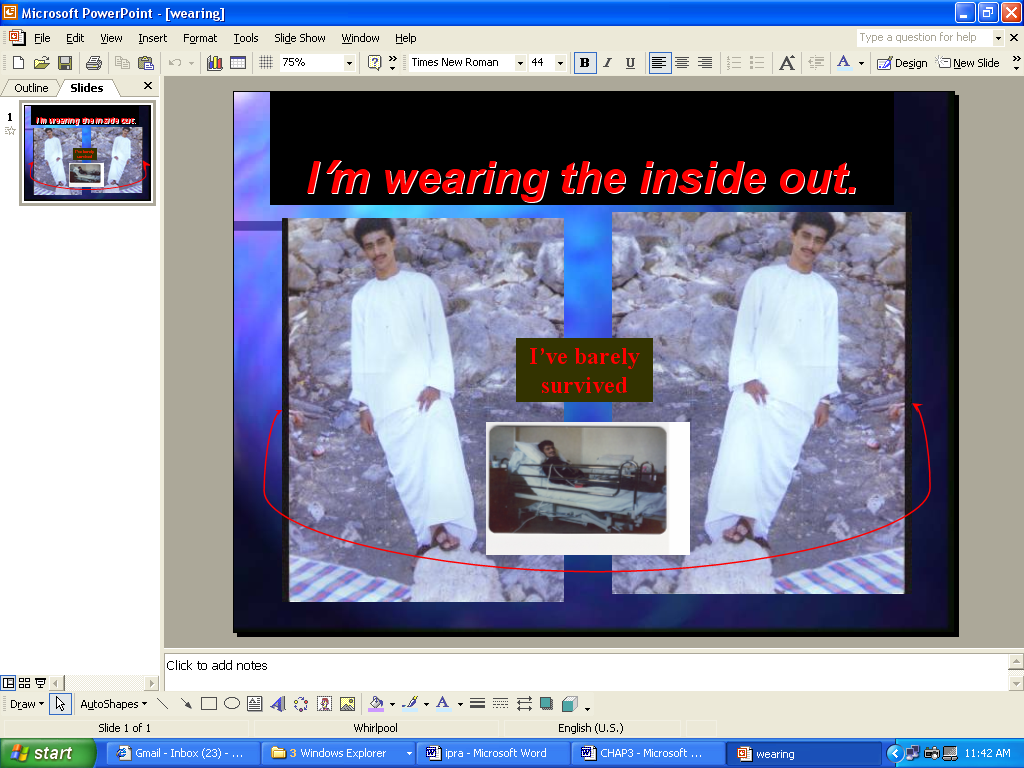

Video 7: Vow of Silence

While the visual aspect in Videos 6 and 7 is the same, the text and music accompanying each videos are different. As such, the videos deliver different (although related) messages. Visually, Yahya's choice of a frontal angle where he looks directly at the viewer as he lays on his hospital bed, according to Kress and van Leeuwen's (1996) visual semiotics, represents involvement by establishing an imaginary relationship with me, the sole target of the videos, whereby he is symbolically demanding pity and sending the message that he has no one to look after him but himself. The demand and the accompanying self-pity are indicated through the way the various images in the two videos are connected with each other. Specifically, Yahya juxtaposes a combination of pictures representing him as standing up (past) with lying on a hospital bed (present). The former's size and placement on either side of the videos indicate saliency; the latter image, which represents his current reality, is placed in the lower middle, whereby he looks as though he is looking up at the viewer (demanding pity). The three images are connected or contained by a red arrow; this not only frames the pictures, but suggests (Yahya later explained to me) that he has no one to depend on but his two angels (which is his past self—the independent Yahya). It is widely believed in the Muslim culture that each person has an angel on each shoulder protecting him or her. Through this imagery of independence, his framing of his past and present self and through drawing on the cultural idea of protective angles, Yahya disconnects himself from his surroundings.

Verbally and musically, the messages conveyed in the two versions of the videos accentuate the idea communicated by the images: They collectively emphasize the notion that Yahya can depend on no one but himself. The title of the Arabic video, for instance, is a line from an Arabic ballad named "I pity myself for life has been cruel to me," which also accompanies the video. The lyrics of the ballad discuss loneliness, hurt, and bad luck in life. This message is further accentuated visually by the comment "the pains of body and soul" in the black box in the center of the video. In the English version (Video 7), the title of the video is a line from a well-known song by the British progressive rock band Pink Floyd, "Wearing the Inside Out." The message in the black box is "I've barely survived," which is another line from the same song. Everyone has seemingly given up on Yahya; thus, Yahya retaliates by turning to oneself and taking a vow of silence, as also expressed by the music accompanying Video 7. However, unlike the Arabic song, where self-pity is accentuated, the English song communicates slight hope. The Pink Floyd ballad is about being on the verge of despair, indicated by lyrics about being "overrun," "barely surviving," as "this bleeding heart is not beating much." Nonetheless, the lyrics end with these two lines: "I am coming back to life" and "I'm holding out for the day when all the clouds have blown away." This indicates that notwithstanding being let down by me and his family, Yahya, in reality, has not given up entirely on me. He is, indeed, hoping his video will persuade me to revisit my decision not to partake in getting him an exception. Collectively, thus, the music of both versions act as a cry for help before it is too late.

In the third video in this section, Yahya elaborates the theme of friendship while continuing to depict himself as being alone and unable to rely on anyone. He thus continues evoking the protector schema by attempting to get the lower hand. This video, strangely enough, was made for his own viewing with me and his family being intended overhearers; thus, while he did not send it to me, his other friends, or family, Yahya did play the video on his computer continuously for hours at times following our joint refusal to help him in his mission. The video presents a greeting card of a collection of roses that Yahya has dedicated to himself. This action is reminiscent of a widely accepted practice in Oman whereby friends send each other greeting cards to show how much they care as discussed in the previous section. By sending the video to himself, Yahya once again evokes the notion that no one would ever send Yahya a card, so he must send one to himself. The video also is intended, Yahya admitted later, as a reminder to me of the duties of friendship. The intent was to indirectly suggest to me that I have failed as a friend. In particular, the messages communicated through the video center around the themes of friendship, giving, religion and the brevity of life (each rose represents one of these themes). Together, they send a reminder that friends and blessed people, in general, are expected to give to others, especially because life is short. This draws on cultural understandings in Omani and other Arab societies that are collective in nature that one is supposed to put others' needs before one's own. The music of the video further accentuates the theme of being let down by friends. The Arabic song, "My precious dear," is a monologue in which the singer is expressing sorrow over lack of good friends and fortune. Collectively, the video and the music deliver the message that Yahya is hurt by my actions as a friend, while emphasizing his disconnection from everyone else surrounding him. Despite Yahya's efforts, this video does not lead me to answer Yahya's plea and I do not play my role in the protector schema.

Video 8: My Precious Dear Self

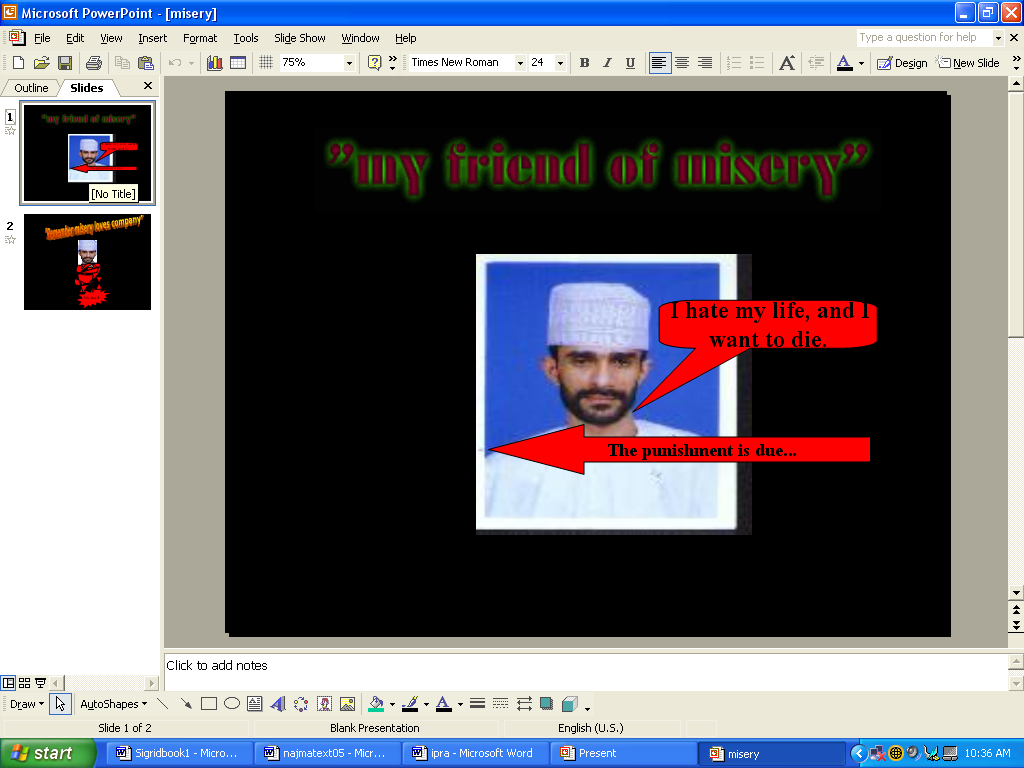

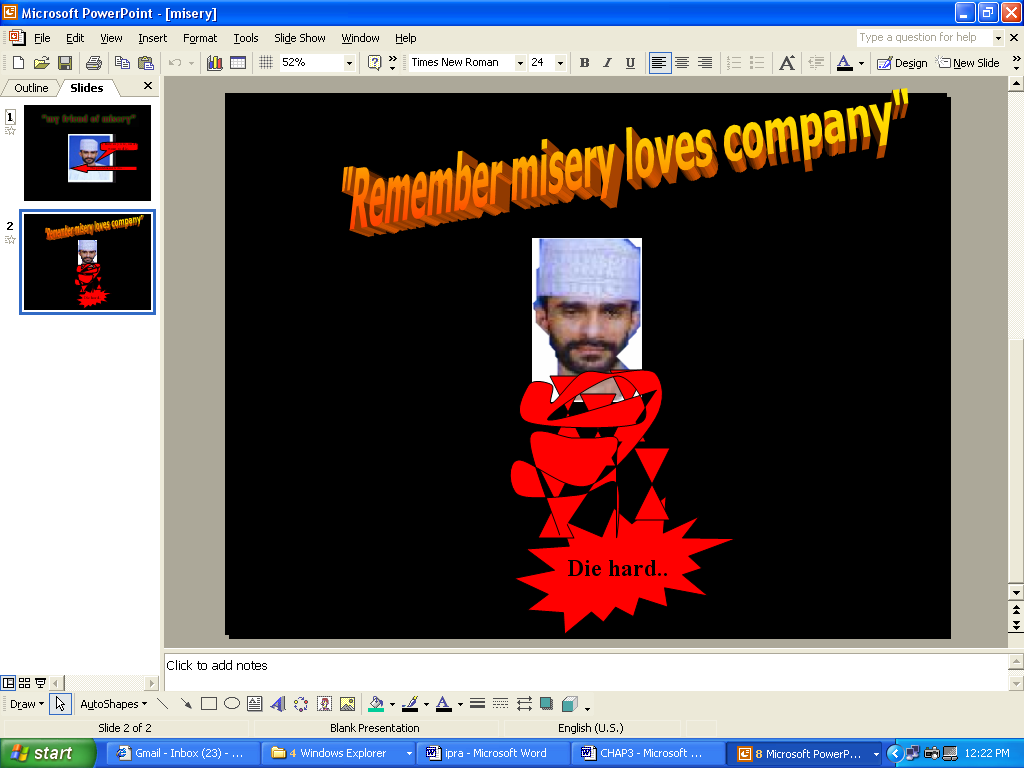

Next, Yahya sends me a music video (Video 9) in which he blatantly admits his hatred of his life and expresses that perhaps his only option is to take his own life. He visually represents committing suicide in the second slide of the video. The visual elements of the video are striking. Yahya once again chooses the frontal angle. However, this time, his image is salient: He is staring the viewer (me, in this case) in the eye. He is not demanding pity in this video. Instead, he seeks to unsettle me with a direct or penetrating stare, according to Kress and van Leeuwen (1996). The dark colors (black and red) used in this video, emphasize death and blood. The texts accompanying the messages emphasize Yahya's self-hatred. The theme of abandonment and having no one to listen to despite incessant attempts to be heard is delivered through the music accompanying this video, which is "Misery" by Metallica. The opening lines include the following lyrics: "You still stood there screaming. No one caring about these words you tell. My friend before your voice is gone. One man's fun is another's hell." This last video with its two parts could be erroneously read as an example of being passive aggressive, especially because it evokes the culturally unacceptable act of committing suicide. Taking a broader cultural rather than psychological perspective, however, lends more insight. The video evokes the culture-specific protector schema as Yahya tactically constructs a helpless self to convince me to help him. Thus, he seeks partial control over his future. In other words, these videos are strategic actions intended (with his own admission at playback sessions) to get what he wants: to make me revisit my earlier decision to decline helping him obtain the exception necessary for him to hire his own resident assistant.

Video 9: Misery (Slide 1)

Video 9: Misery (Slide 2)

As is clear from Video 9, Yahya uses his art in ways that are upsetting, but also persuasive. He symbolically (visually and virtually) commits the culturally unacceptable act of decapitating himself. This gives him some form of control that he actually lacks altogether. In reality, even if he wanted to commit suicide, he would not be able to do so without assistance. Yahya indeed makes his internal emotions visible to me and to the world as expressed in the videos analyzed in this section. However, as discussed throughout this paper, these are not merely artistic expressions; they also are actions. In the face Yahya's positioning, I reconsider my earlier decision not to help him obtain his own permit and I decide to help him. When I finally informed Yahya of my revised decision later that night after I received Video 9, he informed me that he knew that self-presenting as helpless would lead me reconsider my earlier position. That is, he did intend to make music videos that serve as actions to get what he wanted from me, which was to help him out in a mission I deemed impossible at the time. This indicates that while Yahya constructs a helpless self in his music videos, he actually exerts agency in real life. Strategically and creatively making music videos through PowerPoint allows him to get the lower hand, leading him to influence my actions.

Together, Yahya and I spent the summer of 2002 convincing government officials to grant Yahya an exception so that he could finally have a right previously reserved for married couples (hiring someone to care for him). The road was filled with many hurdles; but, after three months of daily hard work, Yahya and I succeeded in making Yahya the first unmarried man in Oman to obtain the right to hire his own resident assistants (and the first quadriplegic man at a time when talking about the rights of people with disabilities was still something unheard of). By Fall 2002, Yahya and his mother made up and, as a result, Yahya moved back to his parents' house (a house he had helped build using his pension money) with his own personal assistant, Lukshmi, from India. The action of having hired his own assistant not only gave Yahya control over a vital aspect of his life, but also was symbolic in a different way: It managed to change how his parents viewed him. For the first time, they started seeing their son with a disability not as a dependent half of a man, but rather as a person who is capable of achieving miracles once he sets his mind to it. This turn in Yahya's life not only created social change at home, and societal change in getting the exception, it also alerted many officials in Oman to the plight of those with disabilities. Yahya's music videos, which interweave culturally-salient traditions (of greetings cards and the protector schema), contemporary song lyrics and music, and the modern technology of Microsoft PowerPoint, made this feat possible. These actions also represented Yahya's taking a stand against a widely acknowledged predicament among people with quadriplegia—social exclusion.

Art as Mediated Action

In this paper, I conceptualized art as mediated action carried out by agents through mediational means (technology) to achieve intended outcomes (in this case, combating interpersonal and social exclusion). In the first section, I showed how Yahya manages to ensure inclusion through making music videos that keep him an active participant in his immediate family circle as well as in interactions with his friends. While he is incapable of carrying on many actions, such as participating in social occasions that take place outside home—especially since both his family and society discourage such participation in various ways, his personalized and animated videos allowed him to get the attention of his family. These videos display his creativity and ability to create complex videos (despite his physical limitations) that are akin in some ways to traditional greeting cards. In addition, his making of these videos enables Yahya to participate in family occasions and participate in wider social circles, including specially organized ones (e.g., teaching the children to use PowerPoint), despite the obstacles and orthodox ideas surrounding him as a quadriplegic man living in Oman. In similar ways, he makes videos that ensure his role as an active participant in his community of friends by creating videos that divulge in spiritual discourses; these not only express his beliefs, but also keep lines of dialogue open with family and friends. Analysis only in terms of their internal grammar or as merely self-expressions or representation does not do justice to these works of art; it gives an incomplete picture of Yahya's capabilities as a quadriplegic young man living in a society where exclusion is still widely considered an inevitable outcome of disability. It also underestimates the power of artwork more generally, and the power of those who create art.

In the second section, I demonstrated how Yahya uses music videos to accomplish meaningful social action—to lead another person to take action, which in turn leads to the collaborative accomplishment of social change through evoking a protector schema. The videos (three of which were sent to me and one which was played repeatedly on his computer) express his pent-up feelings toward his circle of friends. They position him as a lonesome man whom everyone has abandoned and, therefore, he can only turn to himself. However, the videos are more than that: they are a creative take on a cultural practice called "getting the lower hand," which enables him to use the videos he excels in making as strategic actions focused on a specific goal. Thus, despite constructing him as helpless, the five videos analyzed in the second section get Yahya what he wants: I agreed to do my duty as a friend and help him get his special permit. This life-changing action transformed Yahya from being perceived as a quadriplegic dependent man who does not even get to decide who cares for him, to an independent individual, a man who succeeds in becoming the first quadriplegic man in Oman to own the Ministry of Manpower permit. In addition to garnering the respect and attention of his family and friends by securing the permit, this action has also resulted in opening lines of dialogue with government officials. For many of these officials, it was the first time they were reminded that people with disabilities have rights and need to have some control over their lives. Thus, the action created not only a change in Yahya's interactions with his family and friends, but it actually led to social change.

To understand the significance of such actions (i.e., making animated music videos through Microsoft PowerPoint to fight social exclusion), we must draw upon sociologist Goffman's (1963) seminal study of the management of stigmatized identities, which is one of the key studies that has led to the development of the field of disability studies. According to Goffman, the discrepancy between who someone is in reality (one's real identity or private self) and who one wishes to be or who the wider society expects one to be (one's virtual identity or public self) is the main plight of stigmatized individuals, whom the wider society has labeled "abnormal." Unlike "normal" individuals, stigmatized people—especially those whose stigma is physically apparent, such as quadriplegic persons—need aid in facilitating this discrepancy between their real and virtual selves. This aid is usually provided by those whom Goffman refers to as the "wise": the stigmatized's families, friends and health workers who, by virtue of their knowledge and closeness to the stigmatized individual, can assist that person in surpassing his or her limitations as physically dependent and passing as "normal." While Goffman acknowledges that "normal" and "deviant" individuals are "part of each other" (p. 135), in his discussion of identity management by the stigmatized, he constructs a view in which the wise in reality hold the power. Unlike this dichotomist view, in which only one source has power, this study illustrates that via the mediational means of technology, a dependent agent plays a crucial role in managing his or her own identity. My analysis demonstrates Yahya's capability in playing an active role in managing the discrepancy between his own real and virtual selves, suggesting the possibility of an individual with a disability to be his own "wise."

In addition to advocating investigating how people with disabilities use multimodal means to effect change in their own lives, the analysis calls for the development of a multimodal theory relevant to disability studies and, in particular, a sociocultural approach to disability. I suggest that recent approaches in multimodality that apply a mediated discourse analysis framework (Scollon, 2001) to visual texts and/or works of art (e.g., Al Zidjaly, 2011) provide the foundation for such a theory. In this view, artworks in all shapes and sizes are mediated actions carried out by agents to achieve certain goals instead of simply as mere means for self-expression, healing, emotional management or representation. This analysis, thus, contributes to current research in disability and multimodality by conceptualizing multimodal texts—including art works as mediated actions that are situated in sociocultural contexts as well as in the scenes of everyday life. It highlights the need to explore how texts or works of art are used in real life or are integrated in everyday practices as actions that are used to achieve certain outcomes. Understanding art in this way has consequences for disability studies. While the field has long identified the crucial role that art and technology alike can play in alleviating disability, how exactly this occurs in terms of accomplishing social action is largely unexamined. This multimodal analysis, from a mediated discourse perspective, also reveals the complexity of the relationship between technology and disability, highlights the agency of people with disabilities and demonstrates how a person with a disability can create inclusion through technology. It reinforces, and shows in specific terms, how disability is a sociocultural construct. This newly conceptualized and still developing dynamic approach to multimodality, thus, combines textual representation with social construction. Combining the two in the context of disability studies offers a powerful tool to do critical and socially-driven multi-semiotic analysis that is especially needed in disability studies.

NOTE: Yahya Al Belushi has given his permission to print the nine animated music videos analyzed in this paper.

References

- Ainsworth-Vaughn, N. (1998). Claiming power in doctor-patient talk. U.K.: Oxford University Press.

- Al Zidjaly, N. (2005). Communication across ability-status: A nexus analysis of the co-construction of agency and disability in Oman. PhD dissertation, Georgetown University, Washington, DC.

- Al Zidjaly, N. (2006). Disability and anticipatory discourse: The interconnectedness of local and global aspects of talk. Communication & Medicine, 3(2), 101-112.

- Al Zidjaly, N. (2007). Alleviating disability through Microsoft PowerPoint: The story of one quadriplegic man in Oman. Visual Communication, 6(1), 73-98.

- Al Zidjaly, N. (2009). Agency as an interactive achievement. Language in Society, 38, 177-200.

- Al Zidjaly, N. (2010). Intertextuality and Islamic identities online. In R. Taiwo (Ed.), Handbook of research on discourse behavior and digital communication: Language structures and social interaction (pp. 116-136). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Al Zidjaly, N. (2011). Multimodal Texts as Mediated Actions: Voice, Synchronization and Layered Simultaneity in Images of Disability. In Sigrid Norris (Ed.), Multimodality in Practice: Investigating Theory-in-Practice-through-Methodology [Routledge Studies in Multimodality] (190-205). London: Routledge.

- Beeman, W. O. (1986). Language, status, and power in Iran. Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press.

- Corbett, J. (1999). Disability arts: Developing survival strategies. In P. Retish & S. Reiter (Eds.), Adults with disabilities: International perspectives in the community (pp. 171-181). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Crutchfield, S., & Epstein, M. J. (2000). Points of contact: Disability, art and culture. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Diem-Wille, G. (2001). A therapeutic perspective: The use of drawings in child psychoanalysis and social science. In T. van Leeuwen & C. Jewitt (Eds.), Handbook of visual analysis (pp. 119-133). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Everts, E. (2004). Modalities of turn-taking in blind/sighted interaction: Better to be seen and not heard. In P. LeVine & R. Scollon (Eds.), Discourse and technology: Multimodal discourse analysis (pp. 128-145). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Ford, P. J. (2001). Paralysis lost: Impacts of virtual worlds on those with paralysis. Social Theory and Practice, 27(4), 661-680.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of a spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Goggin, G., & Newell, C. (2003). Digital disability: The social construction of disability in New Media. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Goodwin, C. (1995). Co-constructing meaning in conversations with an aphasic man. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 28(3), 233-260.

- Goodwin, C. (2001). Practices of seeing visual analysis: An ethnomethodological approach. In T. van Leeuwen & C. Jewitt (Eds.), Handbook of visual analysis (pp. 92-118). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Grimaldi, C., & Goette, T. (1999) The Internet and the independence of individuals with disabilities. Internet Research, 9(4), 272.

- Halifax, N. V. D. (2009). Disability and illness in arts-informed research: Moving toward postconventional representations. Oxford, UK: Cambria.

- Iedema, R. (2001). Resemiotization. Semiotica, 37(1/4): 23-40.

- Iedema, R. (2003). Multimodality, resemiotization: Extending the analysis of discourse as multi-semiotic practice. Visual Communication, 2(1), 29-57.

- Jones, R. H. (2005). "You show me yours, I'll show you mine": The negotiation of shifts from textual to visual modes in computer-mediated interaction among gay men. Visual Communication, 4 (1), 69-92.

- Kaye, H. S. (2000). Computer and internet use among people with disabilities. Washington, DC: National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research and U.S. Department of Education.

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Edward Arnold.

- Lewis, V. A. (2000). The dramaturgy of disability. In S. Crutchfield & M. Epstein (Eds.), Points of contact: Disability, art, and culture (pp. 93-108). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Murphy, R. (1990). The body silent: The different world of the disabled. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Robillard, A. (1999). Meaning of a disability: The lived experience of paralysis. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Scollon, R. (2001). Mediated discourse: The nexus of practice. London: Routledge.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourses in place: Language in the material world. London: Routledge.

- Seymour, W., & Lupton, D. (2004) Holding the line online: Exploring wired relationships for people with disabilities. Disability and Society, 19(4), 291-305.

- Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1986). Reducing social context cues: Electronic mail in organizational communication. Management Science, 32, 1492-1512.

- Tannen, D. (2005). Conversational style: Talking among friends. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Wexler, A. J., & Cardinal, R. (2009). Art and disability: The social and political struggles facing education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.