Feminist scholars have suggested a broader conceptualization of work to include paid and unpaid, visible and invisible labor. Employing this broader conceptualization, this paper examines a new form of service delivery for deaf people, video relay service, as an example of the growing trend in the United States that shifts labor from the service provider to service recipient. The data discussed in this paper were collected from two focus groups with deaf people who shared their experiences with and feelings about video relay service. The findings suggest that although video relay service is preferred to text relay service by deaf people, there are still misunderstandings that occur. And, in responding to those misunderstandings, deaf people must determine whether it is worth their time and energy to confront less than adequate sign language interpreters, hang up and call back in order to get another interpreter, or do nothing.

Introduction

On a recent trip to have some blood drawn, I stopped at the library to check out a book. As I approached the self-checkout and inserted my library card, I thought about the ease of the checkout process. I then headed over to the lab.

As I entered the clinic for the first time, instead of being greeted by a clerk, I saw a computer screen that seemed to be strategically placed between me and the women working on the other side of the counter. At the top of the monitor there was a sign that said, "Self Check In." I approached the machine and read the screen. At the bottom of the screen there was a digital button that said "Start." After pushing the start button, I was given two choices. I could either type in my name or, just like the self-check-in kiosks that are so common at airports around the United States I could run my credit card through the reader for identification purposes. I chose to type my name. Once I was done typing my name I took my seat with the twenty other individuals waiting to see the medical paraprofessional.

While waiting for my name to be called, others entered and some, missing (or ignoring) the sign, approached the two women sitting behind the counter. Each was quickly referred to the self-check-in computer with a "You can check yourself in and have a seat." One lady who didn't speak English fluently approached the counter and was referred to the electronic surrogate with English directions and a point of the index finger. She approached the computer and stared blankly at it. Eventually, a young man in the waiting area said, in Spanish, "nombre." The woman responded with "gracias" and quickly began to poke at the computer screen. The women behind the counter only initiated interaction with those of us waiting to be poked or deposit urine in a remarkably small cup when they needed proof of identification, proof of payment (e.g., insurance), and to take us to the room where they would take our sample.

The blood work that I had done required that I fast before the blood draw. Therefore, when I was done, I decided to stop by McDonalds. After placing my order at the drive through menu, the clerk instructed me to check the LCD screen to make sure my order was correct before pulling forward. Being satisfied that the bag they were about to hand me was filled with the items I ordered, I drove forward to the next window, paid for my order and drove away.

While I am convinced that in some ways these experiences were more convenient for me, the irony is not lost on me. This convenience requires me to perform labor that I pay, one way or another, someone else to do. For example, it is not uncommon to see in large stores (e.g. Home Depot), just as we do in libraries, self-check-out systems whereby the customer now scans and bags her or his own items and only engages an employee of the store if there is a technical problem with the check-out machine. Furthermore, some stores have installed scanners throughout the store to enable customers to perform a price check on any item that does not have a price tag on it.

I call this consumer performed labor which is unpaid, at least not with money, and always intentional calculated consumer labor (Brunson 2009). I use the term "calculated" to demonstrate that this labor does not occur haphazardly. Rather, it is the result of calculations by the customer who must determine the benefits and drawbacks of doing (or not doing) a particular activity. While this paper focuses on the calculated consumer labor from the standpoint of the customer, it should be understood that the calculated consumer labor of customers is, at least in part, the product of calculations of service providers as well. That is, customers are made responsible for carrying out various forms of labor by service providers who, based on their own calculations, determine the amount of work that is the responsibility of the service recipient. Both of these calculations, those performed by the recipient and those performed by the provider, are based on a cost — benefit analysis.

On the part of the consumer, she or he must calculate whether the benefits of receiving a particular service outweigh the costs (financially or emotionally) associated with trying to get the service. In some cases, it is merely a calculation of the amount of time and energy the recipient is willing to expend to receive a particular service. Providers, on the other hand, must determine the amount of work consumers are willing to perform before they will go elsewhere, taking their money, for a comparable service. When consumers do not have a choice, service providers are able to require more labor from them. With populations that have been systematically disenfranchised from society and have been labeled the "Other" or otherwise stigmatized (Goffman 1963), it is often the case that they have little or no choice as to the amount of work they will perform because the service they seek is a necessity and, in some cases, offered by the state whose monopoly over the provision of the particular service is sacrosanct. When service recipients have little or no choice in where they receive a particular service, the service provider, being in an extremely advantageous position, is able to invert the workload, making the recipient responsible for more of the labor.

In this paper, deaf people's experiences with video relay service — a new telephone service for deaf and hard of hearing people — are used to explicate the ways in which "functional equivalency" and the access it is intended to provide is a product of calculated consumer labor by deaf and hard of hearing users of video relay service.

Although the experiences I shared above and the experience of deaf people I am going to discuss later in this paper are all mediated by technology, there are ways in which calculated consumer labor appears in the absence of technology. As I will discuss, some of the literature refers to the labor of consumers of services; however, the authors do not conceptualize it as calculated consumer labor. After I lay out the literature that is relevant to the rest of this paper, I will then outline the methods used to gather the data. Video relay service and types of misunderstandings and the calculated consumer labor performed by deaf people to mitigate these misunderstandings, and accommodate the sign language interpreters who cause them, that occur in this medium are then discussed. I conclude with the possible explanations for this calculated consumer labor and the long- term affects of this labor being performed.

Reconceptualizing Work

The definition of work is connected to the culture in which the activity takes place. In the United States, and other capitalist economies, work typically refers to those activities for which remuneration can be expected. Hall (1994) defines work as "the effort or activity of an individual that is undertaken for the purpose of providing goods or services of value to others and that is considered by the individual to be work" (p. 5). However, this definition ignores work that is essential to the function of society. Therefore, feminist scholars have expanded the definition of work to include a range of practices for which people, typically women, are not paid (see Daniels 1987; Smith 1987; DeVault 1991). Some of these practices include rearing children, cooking, cleaning, and carpooling. Within this broader conceptualization of work, people's behaviors that deal with one's feelings are also included. Hochschild (1983) in her study of flight attendants referred to this as "emotional labor" (p. 7). In her study of workers in the airline industry, Hochschild argues that there is a degree of "detachment" of emotions from the airline attendants saying "…in order to survive their jobs, [a flight attendant] must mentally detach themselves….from her own feelings and emotional labor" (ibid.:17).

Since Hoschschild's study, different scholars have taken up the issue of emotional labor (see Steinberg and Figart 1999). However, a great deal of this examination takes as the starting point a paid employee and the unpaid labor they perform as they engage customers in such a way to make the patrons either more or less comfortable, depending on the purpose of the interaction. This is not to say that there are no studies that examine the unpaid labor of people who are performing this labor separate from their paid employment.

In her study of "invisible" work of feeding the family, DeVault (1991) documented the myriad of work performed, often, by women. Her analysis builds upon Hochschild's conceptualization of emotional labor. DeVault uses interviews and naturalistic observations to demonstrate that buying and preparing meals comprise only a component of a larger undertaking. Feeding one's family involves planning, negotiating, and budgeting, among other things. "In addition to monitoring the household, shoppers must monitor the market, so that they know what is available and where to get it" (p. 72).

Cahill and Eggleston (1994) have also used the concept of emotion work while examining unpaid work. In their study of wheelchair users they illustrated the emotional negotiations that wheelchair users perform while navigating public spaces. In doing so, Cahill and Eggleston demonstrate that this invisible and unpaid labor is not solely the domain of service providers, but can include those who are typically thought of as service recipients — people with disabilities. In order to avoid having "walkers" in public spaces feel awkward, wheelchair users worked to keep their emotions in check when, without being asked, walkers assumed the needs of the wheelchair user or ignored them altogether.

While Cahill and Eggleston explore the work of people with disabilities in public spaces who are engaging people from whom they are not trying to receive services, Schwartz's (2006) study of the various practices taken up by deaf people in order to receive medical attention moves the discussion into the semi-public spaces — doctor's offices — with service recipients. Drawing on his own experiences as a deaf patient and those of his participants, Schwartz illustrates how deaf people position themselves in the waiting room as to be able to see when their names are called; hide the fact that they are deaf until after the appointment is made as not to be refused service; and refuse to share the name of doctors who provide sign language interpreters with friend out of fear that the doctor will resent having to pay for interpreters for several patients. While Schwartz does not call it labor, his study draws attention to calculations that deaf people perform in order to take advantages of services.

Here, in exploring the experience of deaf and hard of hearing people who use video relay service, I adopt the notion of work employed by feminists that defines it "in a generous sense to extend to anything done by people that takes time and effort, that they mean to do, that is done under definite conditions and with whatever means and tools, and that they may have to think about" (Smith 2005:151-152). Therefore, when I say work, I am including the myriad of efforts that are paid and unpaid, visible and invisible that people do that are intentional and calculated. And, I situate my discussion within a social model of disability, which points to society rather than the individual for causes of disability, to document the work performed by deaf people to take advantage of a service intended to provide them with access.

Methods

The data discussed here were collected during a larger project that examined the practice of sign language interpreting that occurs within a particular context: video relay service. The project spanned 4 years and included participant observations, interviews, examination of texts, and focus groups. In this paper, my analysis centers on the data gathered during the two focus groups with deaf people in two different cities and supplement it with data gathered during my participant observations and examination of texts.

For one focus group, the deaf people were met during a function for deaf people and asked to participate in the focus group. Members for the other group were contacted by a deaf person I knew and asked to participate in the focus group. Because of the language modality used by the participants in the focus groups, both were kept relatively small. Five people were asked to participate in both focus groups. The first one, only two deaf people showed up. Both were white and male. All five of the individuals participated in the second. In that group, there was one woman and two people of color. All of the participants self-identified as Deaf2 and said that American Sign Language was their preferred language.

The groups were asked to discuss their experiences using video relay service. Although each focus group was scheduled for two hours, they both lasted closer to three. Each focus group was conducted in American Sign Language and was videotaped and moderated by me. I later transcribed, and asked them to verify my interpretation of the video tapes from American Sign Language to English. Once the transcriptions were complete, I used open- and then focused — coding system to discover themes. The discussions in the focus groups spanned from reasons for using video relay service to the skills of sign language interpreters. It should be noted that because the focus groups occurred in American Sign Language, the quotes are my interpretation of the comments signed by the participants.

Video Relay Service and Sign Language Interpreting

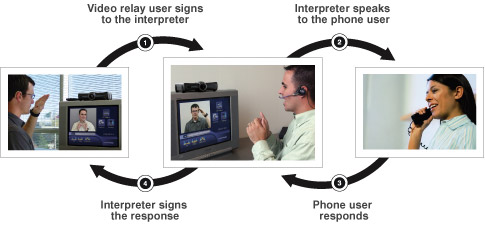

In 2000, the Federal Communications Commission expanded "relay service" making video relay service eligible for reimbursement through the Telecommunication Relay Fund to include video relay service. The funds are distributed through the National Exchange Carrier Association, Inc.3 This new venue allows for deaf and hard of hearing people to communicate via the phone with non-deaf, non-signing individuals around the world. The Federal Communications Commission is charged in Title IV of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 with providing a telephone service for deaf and hard of hearing people that is the functional equivalent to the telephone service that non-deaf people enjoy.4 This service uses video cameras, broadband technologies, and sign language interpreters to provide deaf people with telephone access. Figure 1.1 depicts the process with the deaf user, male, at the left, the sign language interpreter in the middle and the non-deaf user, female, at the right.

(retrieved from http://www.fcc.gov on 09/15/07)

To capitalize on this federally funded service, more than 15 for-profit companies established video relay service centers around the United States (and a few in Canada) where sign language interpreters, working in call centers, relay calls between deaf and non-deaf people.

Video relay service allows deaf people who use a signed language, as opposed to relying solely on reading lips, hearing aids, and or cochlear implants, to have greater access to the world they live in via the telephone. Using this new service, deaf people can communicate in a visual, rather than a "vocal-auditory" language (Bake-Shenk and Cokely 1980), to converse with friends, family, and attend to business over the phone. However, this new technology comes with old problems. These problems are a direct result of deaf people's reliance on a third party to communicate.

Sign language interpreting is not an exact science. There are a variety of factors (e.g., language, culture, education, mood, etcetera) that can influence an interpretation and the same factor can have a completely different effect in a different setting. Due to the complexities of sign language interpreting, interpretations can and do fall short of the message equivalent goal (see Turner 2005). As such, deaf people are often left to perform their own interpretation while simultaneously receiving the interpreted message. That is, deaf people are required to fill in the blanks or attempt to make meaning out of what can sometimes be jumbled messages. Sometimes the message is so skewed that even with deaf people attempting to decipher the message the original intent of the sender is unclear, and this leads to misunderstandings.

Misunderstandings in Video Relay Service

The deaf people who participated in the focus groups praised video relay service because they were able to use their native language. Although they appreciated the convenience of video relay service, they also mentioned the misunderstandings that occurred. These misunderstandings occur for a variety of reasons. The most commonly cited misunderstanding arose from the inability of sign language interpreters to understand finger spelled words. Finger spelling refers to the practice of using different hand shapes, in the United States and parts of Canada, to represent the alphabet and numbers of spoken English. I asked members in the focus groups to discuss their experiences, good or bad, with video relay service. Here, Deb expresses her frustrations with sign language interpreters' inability to understand finger spelling:

One thing that is really frustrating is that interpreters don't understand finger spelling. I notice the most problems with something like 6 or 16. Interpreters struggle with trying to understand which number I am signing. I think interpreters need a lot more training on numbers. One time I was calling an interpreter. I was asking them if they would accept a last minute request. I asked the interpreter and they accepted. I told them to add $6 per hour to their invoice and when I received their invoice they had added $16 per hour. Obviously the interpreter in video relay misinterpreted what I said. That is a problem I had with video relay.

The only difference between numbers 6 through 9 and 16 through 19 is a turn of the wrist. On a two-dimensional screen it is sometimes difficult to catch the correct number. Even without the added factor of two-dimensions, sign language interpreters have expressed "frustration in reading finger spelling and numbers" (Seal 2006:6). This frustration is complicated when the sign language interpreter must comprehend a language that relies on a particular space, the "area from the top of the head to just below the waist" (Greene and Dicker 1990: 20), to convey concepts. When this two-dimensional space is viewed on a 32-inch (sometimes smaller) screen, the signing space becomes truncated, which can add to the difficulty of understanding particular signs

Deb was attempting to find an interpreter for a last minute request, which interpreters usually bill at a higher rate since it is last minute. Having the coordinator of interpreting services say they will pay you $16 above your normal rate per hour for a last minute job is out of the ordinary; however, given the shortage of interpreters, sign language interpreters are a sought after resource and thus there is a bidding war, if you will, occurring (Bailey 2005). Sign language interpreters are cashing in on it too. Deb does not allow for the possibility that the video relay interpreter provided the correct interpretation, but the sign language interpreter heard it wrong. Instead, the blame immediately is placed on the video relay interpreter. Placing the blame for the misunderstanding on the video relay service interpreter is perhaps not surprising given that Deb is only able to see the interpreter during the interaction and is not fully privy to interaction between the interpreter she is calling and the video relay service interpreter.

Upon seeing Deb's comment, Edward suggested that perhaps it is not the fault of sign language interpreters, but of deaf people, that misunderstandings occur:

Well we really should be clearer. Signing 16 (shaking the 6) instead of starting with the 10 then adding 6 is not clear. I don't know if we can really blame the interpreters when we are not clear.

Edward suggests that Deb's way of signing 16, shaking the 6 instead of showing 10 and then 6 may not be the clearest way to convey that number. He continues by explaining that in his experience, finger spelling, and especially numbers, is difficult for interpreters to understand:

Yeah, I really notice that people have problems with understanding finger spelling or numbers. Many interpreters don't understand finger spelling. I am not sure if they are not paying attention or what but they do have problems understanding finger spelling.

Rather than suggesting that sign language interpreters need more training to improve their ability to understand finger spelling, Edward suggests that it is a momentary lapse in judgment, saying "perhaps they aren't paying attention." While Deb and Edward both discussed the issue of sign language interpreters not understanding finger spelling, neither of them defined the interpreters as "unqualified" because they were unable to read finger spelling.

To Respond or Not to Respond to the Misunderstanding

All of the deaf people I spoke with really liked the video relay service. They saw it as providing greater ease in telephone communication as compared to text relay services. However, they also mentioned some drawbacks. I have conceptualized some of the drawbacks discussed by these deaf participants in terms of the work that they must do in order to gain telephone access through video relay services. The people in my focus groups did not describe these drawbacks in a language of work. However, their accounts of their experience allowed me to discover the actions they take, as clients, in order to make the relay system work for them.

For example, because of the small number of sign language interpreters and the high demand for the service, there are times when a deaf person may wait for several minutes before she or he is connected to a sign language interpreter and able to make a call.5 This is typically a problem during "peak hours." Some video relay service providers are trying to counter this by holding town hall meetings with deaf people and informing them about the best times to call so they will not encounter long wait times. Once Deaf people have this information, they are able to determine if the significance of the call warrants the possible frustration of having to wait for an interpreter. Deaf callers are probably more apt to take advantage of this information when the calls being made are of a personal nature. When calls are of a professional nature, however, it is more difficult. Deaf persons needing to conduct business with their financial institution, for example, must do so between the hours of 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. when banks are open. These considerations mean that deaf people must schedule their calls strategically, thinking ahead about the best time to place a call and how long it might take in ways that are not so necessary for hearing people who pick up the phone and dial the number they desire right away. This work of waiting for an interpreter, planning their phone calls, and determining the best time to call is not the only work that deaf people must do while using video relay services. I will argue that an expanded view of work is useful in analyzing the various ways that deaf participants must themselves work to facilitate their telephone access. These efforts may not be visible to those who think about VRS as a service provided to and for deaf people.

Previously, we learned that Edward placed the onus on deaf people for communication problems. Edward sees accepting responsibility for miscommunications as part of the work of communicating through a third person. Jimmy agreed with Edward. Jimmy explains that deaf people should double check to make sure their message is being understood:

I think that deaf people should double-check if the interpreter understands the message. We should ask to make sure that the interpreter knows that it is 6 and not 16. The deaf person is still responsible to make sure the message is clear.

What this suggests is that rather than focusing solely on conducting their business on the phone, deaf people must also, according to Jimmy, "be responsible" for the accuracy of the interpretation. Successful communication requires everyone involved to work together. However, it must be remembered that the history of oppression of deaf people perpetrated by non-deaf people has situated deaf people in a vulnerable position. Therefore, deaf people's comments must be understood within this context and with the recognition that deaf people still have very little control over the accuracy of an interpretation. Furthermore, their ability to double-check meanings depends on the sign language interpreter's willingness to do so and whether the deaf person feels comfortable asking for clarification.

Although communication for deaf people is easier with video relay services, deaf people still discussed the many kinds of work they have to do when using video relay service. This work is a byproduct of the lack of qualified interpreters. Skill is a subjective measure and each deaf person may choose for her or his own reasons why the particular interpreter is not adequate (Brunson 2008). I asked Jake, a deaf man in his mid-thirties, what he did when he was making a call and the interpreter was less than qualified.

I hang up and call back. I don't feel it is my responsibility to tell the interpreter or their supervisor that they aren't that good. I typically say something like, 'Oh, I forgot the number so I will call back. Sorry about that.' I know that it is unlikely that I will get the same interpreter again.

Even though Jake is pretending, he not only accepts the inconvenience of hanging up and perhaps having to wait for another interpreter to become available, but he also apologizes to the interpreter for any inconvenience he may have caused them. Jake was not the only person who accepted this burden. While talking to a colleague who is a sign language interpreter for a video relay service provider about this research and the work that deaf people do while using video relay service, she recounted the practice that she and her husband, who is deaf, use when the interpreter is less than adequate:

It happens a lot. My husband is not hard to understand. He uses American Sign Language and he is clear. He is also smart. I will sometimes call him several times a day. We have a code. When I start a sentence with "my sister" or "my cousin," he knows that the interpreter is not making any sense to me. He will then say, "Well, I have to go. My boss is coming." And we hang up and call back.

After I was told this story, I asked my colleague why she or her husband did not inform the interpreter that they were not being effective. She said, like so many others I spoke with, "It isn't worth my time." My colleague's statement that her husband is "not hard to understand" should be contextualized. It is not surprising that someone who spends a great deal of time with another person, whether they are family, friends, or partners, do not think that he or she is hard to understand. This may not truly reflect the skill of the sign language interpreter who is interpreting their call. Nevertheless, this story provides another example of the work taken up by callers when they feel their interpreters are not adequate.

In all of the cases, the callers weighed the time wasted in calling back with tolerating the sign language interpreter's errors. Michael, a man who identifies as hard of hearing, but who is fluent in American Sign Language, says:

When the interpreter does not understand me then, depending on the purpose of the call, I will just continue. For example, if I am calling my sister then I wouldn't worry about the interpreter making mistakes. However, if it was something important, I would tell the person I will call back and disconnect so that I can get another interpreter.

Some calls, according to Michael, are not worth going through the trouble of hanging up and calling back. B.T.M.H. a deaf man in his fifties, disagreed with Michael. B.T.M.H. felt that regardless of the purpose of the call deaf people should hang up and call back:

I disagree. I feel that regardless of the purpose of the call if the interpreter is not doing a good job then they should hang up and get another interpreter. They are professionals so they should be good. They get paid a lot of money, around $60,000 to do that job.

B.T.M.H.'s argument that sign language interpreters are professionals who are paid well is an interesting one given that he still does not address the issue of quality with the interpreter. Even though interpreters are professionals being paid very well, B.T.M.H. does not inform them of their errors. Nor does he contact their supervisor. None of the deaf people I spoke with contacted a supervisor to complain about the quality of the sign language interpreter. When I asked them why they did not talk to a supervisor people were unaware that that was an option for them. I then asked if they would talk to the supervisor now that they knew, and the answer was still, "no."

Asking for another interpreter or asking to speak to the supervisor appears to represent more than merely admonishing the service provider. It could also indicate something about the service recipient. In indicating that they are unsatisfied with the service they are receiving, deaf people might worry about showing they are frustrated. As Goffman (1967) suggests, "to appear flustered, in our society at least, is considered evidence of weakness, inferiority, low status, moral guilt, defeat, and other unenviable attributes" (p. 102). Acknowledging that they are unhappy with the service that is being provided is also an admission that the service is needed. Doing so might seem to users of video relay service like admitting they have less power than the sign language interpreters who are there to provide them service.

Another possible reason for this approach taken by my informants is that the priority for them is completing their call. In situations when individuals, deaf and non-deaf alike, must confront poor service providers, the focus of the interaction changes. No longer is the focus on the services originally sought. Instead, the focus becomes the service delivery.

Aside from changing the focus of the interaction, there are other possible consequences to filing a complaint. In choosing to avoid confronting sign language interpreters who may not be providing adequate service to the deaf caller, they are perhaps pointing to the struggle that people with marginalize identities must face with filing a complaint. The amount of work for filing a complaint goes beyond the actual telling of a problem. Often it requires providing evidence, explaining why the behavior was problematic, and confronting the power differential that exists in society. While not addressing the problem may save feelings, energy and time for deaf callers, it also allows for a system that may not be meeting the needs of those it was intended to serve to stay in place because the work of deaf people masks the quality of service they are receiving.

This is not solely the result of deaf people not wanting to confront sign language interpreters. The accounting mechanism in place for video relay service does not make space for documenting work of deaf people as they attempt to gain access. Within the official record of video relay service, deaf peoples' work remains invisible. What gets counted is the minutes the sign language interpreter is connected to the deaf caller, not whether they deaf person was satisfied with the services they were provided.

Discussion: The Continuation of Disablement

Video relay service is intended to provide greater functional equivalency for deaf people on the telephone. As people compared video relay with text relay, it is obvious that the deaf people who participated in the focus groups prefer video relay services. However, there is also room for improvement.

Our interactions are organized, in part, by the space in which they occur. Even though spaces that are designated as public are said to be open to everyone, there are rules that govern interaction that occurs within them. These rules represent shared expectations and are intended to minimize social collisions. However, these rules are also based on able-bodied norms. Video relay service centers are spaces designed for the benefit of deaf people that make deaf people's lives public and hold them to the norms of public intercourse.

The deaf people I spoke with had a great appreciation for video relay service. They saw it as providing more equal access for them on the telephone, because they are able to use their first language rather than English to communicate with others. However, deaf people still must work to gain access through video relay services.

As a population that is disabled and patronized by society, deaf people have developed strategies that aid in dealing with service providers. These strategies are intended to get their needs met while avoiding possibly upsetting sign language interpreters. While this is emotional work, it is also empowering work. It is empowering work since deaf people are taking control over their calls and their lives. The people I spoke with did not seem to resent the fact that they were performing this work. In fact, they saw it as a necessary component of gaining access.

However, it also indicates the disempowered position deaf people occupy in society. Deaf people are made to feel, directly or indirectly, by sign language interpreters and society, that they are not entitled to demand access. They are reminded daily that their needs are secondary to those of the non-disabled person who is assisting them. Furthermore, any complaint by a deaf person may be seen as being ungrateful.

When talking about their experiences, users of video relay service did not acknowledge that they were performing this emotional and invisible work. I suspect this is a product of an inaccessible society, one that reminds deaf people constantly that they are dependent on the kindness of others. Also, if deaf people were to upset the service providers, they fear they run the risk of losing access altogether. Schein (1992) found that deaf students in Alberta were reluctant to complain about interpreters because they feared the interpreter would stop providing services for them and they would be left without access to their classes. While there are no data on whether interpreters retaliate against deaf people who complain about the services they are provided, there is a joke told in the Deaf community that illustrates that trust is at least a consideration for deaf people.

A sheriff asks [a deaf] man where the stolen money is hidden. The deaf man signs and the interpreter voices, "He says, he does not know what you are talking about."

After half an hour of continual denials by the deaf man, the exasperated sheriff places a gun against the deaf man's head and says, "If you don't tell me where the money is hidden, I will kill you."

The interpreter signs the threat, and the now-terrified deaf man responds, "I hid it under the back stairs at my cousin's house."

The sheriff, sensing that something has changed in the deaf man's persistent denials, eagerly asks, "What did he say?" Quickly, the interpreter answers, "He says he's not afraid to die." (cited in Stewart, Schein, and Cartwright 1998: 87).

Even though this joke does not directly address an interpreter outrightly denying a deaf person access, it does address the underlying issue of trust in the interpreter to do the right thing.

The skill of sign language interpreters is an issue for users of video relay service. Even though, as Jimmy said, he feels that video relay service is more "equal to non-deaf," there are strategies that deaf people have to employ to ensure they get access. Whether they are being vigilant about finger spelling clarity or devising stories so they can hang up without telling the interpreter that they are not performing successfully, it is obvious that deaf people are engaging in a lot of work to accommodate differences in the interpreters' skills. This is work that non-deaf people do not engage in while they are placing calls.

Throughout this paper, I have suggested that deaf people perform a variety of work in an effort to gain telephone access through the federally-funded video relay service. While most people may not have experience using video relay service, I suggest that the calculated consumer labor deaf people perform in order to get their needs met in video relay service is representative of a growing trend that places more responsibility on the service recipient rather than the service provider. And because this labor is largely invisible, the service providers are not encouraged to improve their services.

Works Cited

- Baker-Shenk, Charlotte and Dennis Cokely. 1980. American Sign Language: A teacher's resource test on grammar and culture. Clerc Books: Washington, DC.

- Bailey, Janet L. "VRS: The ripple effect of supply and demand," VIEWS, vol. 22(3), 2005.

- Brunson, Jeremy L. 2008. "Your Case Will Now Be Heard: Sign Language Interpreters as a Problematic Accommodation in a Legal Encounter." Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. Vol. 13(1):2.

- ---. 2009. "The practice and organization of sign language interpreting in video relay service: An institutional ethnography of access — Abridged." VIEWS. Winter, Vol. 26 (1).

- Cahill, Spencer E. and Robin Eggleston. 1994. "Managing Emotions in Public: The Case of Wheelchair Users". Social Psychology Quarterly, Vol. 57 (4), 300-312.

- Daniels, Arlene Kaplan. 1987. Invisible Work. Social Problems, Vol. 34, No. 5, 403-415.

- DeVault, Marjorie L. 1991. Feeding the Family: The Social Organization of Caring as Gendered Work. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

- Goffman, Erving 1963. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Pelican Book: Middlesex, England.

- ---. 1963. Behavior in public places. Free Press: New York.

- ---. 1967. Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. Pantheon Books, New York.

- Greene, Laura and Eva Barash Dicker. 1990. Sign me fine: Experiencing American Sign Language. Gallaudet University Press: Washington, DC.

- Hall, Richard H. 1994. Sociology of work: Perspectives, analyses, and issues. Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1983. The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press: Berkeley.

- Schein, Jerome D. 1992. Communication support for deaf elementary and secondary students: Perspectives of deaf students and their parents. Edmonton: Western Canadian Centre of Studies in Deafness, University of Alberta.

- Schwartz, Michael A. 2006. Communication in the doctor's office: Deaf patients talk about their physicians. Unpublished diss. Syracuse University.

- Seal, Brenda Chafin. "Fingerspelling and number literacy for educational interpreters," VIEWS, vol. 23(3), 2006.

- Smith, Dorothy E. 1987. The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology. Northeastern University Press: Boston.

- ---. 2005. Institutional Ethnography: A sociology for people. AltaMira Press: Toronto, ON.

- Steinberg, Ronnie J. and Deborah M. Figart. 1999. "Emotional labor since The Managed Heart." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 561:9-26.

- Stewart, David A., Jerome D. Schein, and Brenda E. Cartwright. 1998. Sign language interpreting: Exploring its art and science. Allyn and Bacon: Boston.

- Turner, Graham H. 2005. "Toward real interpreting." Pp 29-56, in Marc Marschark, Rico Peterson, and Elizabeth A. Winston (eds.) Sign Language Interpreting and Interpreter Education: Directions for research and practice. Oxford University Press: New York

Endnotes

-

A previous draft of this paper was presented at the Society for the Study of Social Problems meetings in 2008 in Boston, MA.

Return to Text -

The capitalized "D" indicates identity with a larger cultural group. Members of this cultural group see their deafness as an identity marker not a disability.

Return to Text -

Although the Federal Communications Commission is ultimately responsible for the relay service oversight, the National Exchange Carrier Association administers all payments for services. Therefore, reports are submitted to the National Exchange Carrier Association.

Return to Text -

Pub. L. No. 101 336, § 401, 104 Stat. 327, 366 69 (1990) (adding section 225 to the Communications Act of 1934, as amended, 47 U.S.C. § 225).

Return to Text -

The Federal Communications Commission requires video relay service providers to answer 80 percent of all calls within 120 seconds.

Return to Text