This article explores longstanding links between cycling and disability. Social models of disability and closely related theories on the social construction of technology are central to our approach. The former insists that disability is a social construct; the latter views technology as socially formed. Disabled persons engage in cycling for, among other things, the pleasure of moving about the city and countryside, parks and neighbourhoods, to access places of work and study, and to gain greater independence in their daily lives. They have played an active role in the development and adaptation of cycles to make them better suited to particular needs. Disabled persons, their friends and family, and technicians have shared ideas and information to design cycling machines that reduce the limitations of technologies and environments developed for so-called "able" bodies. Here, we present a typology identifying seven types of cycles that were and are used by disabled persons for varying purposes. They are as follows: transporters, pedomotives, manumotives, sociables, stability machines, tandems, and power-assisted bikes. In each case, examples existed in the nineteenth century or earlier but social construction and improved materials and technology have dramatically enhanced their utility in recent years.

Introduction

In this paper we explore the ways in which cycles in various forms have been designed and used by and for disabled persons. Briefly, we use identity first language throughout while acknowledging the presence of considerable debate over language and disability and the agency of individual disabled persons in the act of self-identifying. We engage more fully with these issues later. We show that the connections between cycling and disability have historical roots reaching back as far as the mid-17th century, although in recent times new materials and technologies have resulted in major improvements to the usefulness of the cycle for disabled persons. In an important recent paper, Inckle (2019) explores this relationship from the user's perspective in a qualitative study that stresses deficits in knowledge and information on the potential and actual use of cycles, and the deficiencies of a binary policy framework that frequently overlooks the provision of infrastructure for disabled cyclists. Andrews et al. (2018), Clayton et al. (2017) and Rissel (2015) also note the paucity of research on the use of cycles by persons with physical disabilities, and a surprising lack of awareness of their possibilities. 1 We hope this paper partly fills this gap by adopting a classificatory approach – in the Linnaean tradition – to the types of cycles that are used by disabled persons, ranging from standard bicycles to those with specific adaptations. 2 We stress the social context of the relationship between disability and cycle design, both in understandings of disability, and in the adaptation, or development from the ground up, of cycle technologies for disabled persons.

In recent times, cycles and the planning and development of cycling infrastructure have increasingly becoming markers of the so-called progressive, sustainable, resilient city – yet just how institutions and the cycling public writ large view disabled persons fitting into the global cycling project – and vice versa, seems opaque at best (Andrews et al., 2018). For those who might be unaware, disabled persons cycle, and for many of the same reasons as every other cycling body – for the thrill of it, for exercise and competitive sport, to increase mobility, to enable accessibility to work, to places of study, to recreational activities, to commerce, and consequently to enhance their participation in social activities. Drawing attention to the centuries old connections between cycling and disability, as we have done here, contributes to centring disability within a contemporary cycling discourse seemingly bent toward fetishizing normative conceptualizations of cycling bodies and activities.

Definitions and understandings of impairment and disability have changed considerably during the period since Stephan Farfler, a non-ambulatory German clockmaker, invented the first recorded tricycle in the mid-seventeenth century. From Farfler's time, through to the twentieth century, outmoded understandings placed disability within the body as a medicalized individual concern, or as divine punishment (in a Judeo-Christian context). With some disturbing exceptions, these antediluvian understandings have since been displaced by models that stress the social, political, and economic context(s) that produce disability which, as a result, have encouraged many disabled persons to consider the possibilities presented by cycles and made some individuals and institutions more open to the possibilities that exist at the intersection of disability and cycling (Wheels for Wellbeing, 2020).

Everyone has different abilities and we all will experience changes to our abilities as we age, but activists have pushed back the social and technical barriers to disability so that the possibilities for disabled persons have increased (Dolmage, 2017; Wong, 2020; Hansen & Philo, 2007). Rather than recognizing a continuum, many Victorian and Edwardian institutions adopted a dichotomy by separating people with a disability from so-called "able-bodied" individuals, giving rise to the asylum, eugenics, and medically directed treatments in which the patient had no say (Bashford & Levine, 2010; Park & Radford, 1998). In that period, disabled persons using cycles were persons living outside the asylum regime. By the 1970s, however, groups of people with disabilities objected to being categorized. Disability was, they insisted, a socially imposed category: a person may have a physical impairment but that does not make that person disabled unless society makes them so (Rocco, 2011; Oliver, 1990, 1999, 2013). 3 The emancipatory and therapeutic potential of cycles for disabled persons, long recognized by a few, became a matter of broader interest resulting, inter alia, in the creation of several small specialized cycle manufacturers as well as activist organizations such as London's Wheels for Wellbeing, and Detroit's MoGo.

During the past 200 years, bicycle and tricycle technology has advanced in response to the needs of diverse users, including racers in a quest for speed, commuters demanding comfort, and persons wishing to overcome disability and regain a level of independence. In other cases, technological advances have evolved serendipitously as mechanics, experimenting with ideas, occasionally came up with solutions that were adaptable to different needs including those with disabilities. Most cycle designs (we use the term 'cycles' to connote bicycles, tricycles and quadricycles 4) were and are based around normative assumptions regarding a species-typical "able" body (Guffey, 2018). To the extent that cycle designers "are born into an already interpreted world, they and their interpretations of the world are necessarily shaped by socially available understandings" (Bonham and Johnston, 2015, p.8). This social constructionist position asserts that current cycle designs are influenced by how pre-existing designs are found both useful, and/or deficient, and how the experiential knowledge of disabled persons, their immediate social contacts, and technologists working with these groups, help to refine existing designs and imagine new possibilities. Cycle design and technology evolve, with social forces (particularly users of specific technologies) exerting pressure for change. This engages with the work of Pinch and Bijker (1984) on the social construction of technology (SCOT) which places technology in its societal context.

Constructivism stresses the social and geographical context in which invention and innovation takes place, including the ability of society to adapt new technologies to specific needs, to prioritize certain projects, and to work collectively in teams that share knowledge and insight (Norcliffe, 2009). Furthermore, as Oudshoorn & Pinch (2003) note, users matter in several ways - by presenting non-normative needs that require answers, by proposing practical solutions, and by asking institutions for results that overcome specific issues. Today, cycles are used for pleasure and recreation, to assist mobility, speed up recuperation in the presence of acquired injury, serve as a therapeutic intervention (e.g., to maintain flexibility and to train the cardiovascular system), promote exercise and mobile activity, and to enable broader participation within typically exclusionary environments developed by ableist institutions. Depending on how one's body works, many disabled people enjoy riding standard cycles, but in addition, a growing number of specialized and customized cycles have been developed, often in response to disabled persons and their families actively pressing for particular solutions that increase mobility and allow them to engage in many daily community activities. The aim of this article is to describe these developments and, where possible, interpret the genealogy of cycles used in diverse ways by disabled persons.

We recognize that there are serious and complex discussions on terminology, labelling, and identity when working on or with disability. Indeed, disability can be seen to impact everyone in various, often subtle ways, such that dichotomies are meaningless. Our standpoint is that the social model leads directly into rights and justice perspectives, constituting the progressive mainstream of the whole movement (Thomas, 2004). Thus, we favour phrases such as "disabled person" though we acknowledge in particular the progressive and radical turn toward identity first language. Furthermore, when we speak about the possibilities of cycles, we do not advocate for the "fixing" of disabled bodies, but for increasing general awareness of the potential of cycling for leisure, work, recovery from illness, and good health. Many disabled persons ride simply for enjoyment as a pleasurable part of their daily lives, while others might choose to use cycles therapeutically as part of a process of working with and through impairment within a disabling social and environmental context.

Our positions, as authors, also differ both experientially, and in terms of our academic roots. Norcliffe is an economic geographer with interests, inter alia, in cycling technology. Buliung is a transport scholar whose lived experience of disability centres on being a parent of a child who uses a wheelchair for independent mobility (Buliung et al., 2021; Ross and Buliung, 2019). Kruse is a human movement scientist who has investigated the effects of training and treatments on individuals with cerebral palsy. Radford has researched the Victorian asylum (Radford 2000, 2020) and disability more generally, and also has a disabled family member. Our individual, personal and multi-disciplinary academic standpoints have enabled a rich conversation about disability cutting across an onto-epistemological terrain that allows us to think through difficult points of intersection between sociological, historical, bio-medical and critical ways of thinking about disability, cycle design/innovation, and use.

This article is organized in four sections. First, we summarize changing understandings and contrasting terms adopted in the disability literature over the past hundred years. Often seen as a means for treatment and management of disabilities, cycles are also used as a source of enjoyment, a means to socialize, and as a recreational vehicle, just like their non-disabled peers. Second, we examine a range of disabling conditions where cycles with specific attributes present useful possibilities. Third, we summarize the technical dimensions that feature in cycles designed for disabled persons. And fourth, we select examples from our research that confirm the relevance of the social construction approach to understanding how disabled persons and technicians have co-produced cycles for disabled persons.

Changing and contrasting concepts of disability

More so in academic exchange than in society as a whole, the disability/ability binary has given way to recent acceptance of the political, economic and social production of disability, of diversity within the group labeled as disabled, and recognition of the complex manner in which disability and ability are co-constructed (Oliver, 1990, 1999, 2009; Goodley, 2014). At its most radical edge, we have also seen the rise of Crip theory wherein labels of "the clinic" are re-appropriated as a move to organize and empower the community (Schalk, 2013). The clinical label, turned on its head and re-appropriated, comes to exist as a labeling of power and identity first, one that challenges normative ideas about bodies and abilities. Persons who identify as having a disability in one area might view themselves as having an enhanced ability in others: thus, the young Swedish climate change activist, Greta Thunberg, views her autism as her "superpower". Asked if being on the autism spectrum gave her a special insight into climate change or a vision on a course of action, she replied "That could be … I go my own way" (Interview William Brangham, PBS Newshour September 13, 2019).

The cultural and social construction of disability influences the policy framework of a given jurisdiction: significant international and even local differences are to be expected. For instance, in the UK, the evolution of the firm Remploy is revealing of political and identity shifts. Created in 1944 under the Disabled Persons (Employment) Act, Remploy was initially intended to create meaningful employment for persons injured during the Second World War with, at its peak, 83 factories manufacturing a wide range of products (Edwards, 1999). By the 1990s, it began to diversify into finding employment for disabled persons in the service sector. In 2007, Remploy began to open employment offices with the aim of placing disabled persons in mainstream work rather than in dedicated factories, and adopting the slogan 'putting ability first'. Following a change of government in 2010, a phase of privatization began that led to all Remploy factories being closed or sold to the private sector, leaving Remploy as an employment agency matching the skills of disabled workers with productive activities under the Access to Work program (Bombastic Spastic, 2011). This pursuit of neoliberal goals, including the elimination of subsidies, also advanced the ableist aim to eliminate the disability/ability binary in the labour force.

An emerging literature rejects the binary by re-casting particular skills of workers previously categorized as disabled as assets for specific work tasks, including the use of disabled bodies to project a progressive corporate social responsibility (CSR) agenda. In other words, within the context of neoliberal ableism (see Goodley 2014), disabled persons do their daily work, while also elevating the CSR profile of their host company. Another aspect of this model is that it emphasizes the "patient" rather than the treatment: the focus is not on the impairment of a patient but on realizing his or her potential. From this perspective Shakespeare (1996) is highly critical of Oliver Sacks' book An Anthropologist on Mars for exploiting the disabling impairments of patients rather than normalizing them as latent possibilities. In this vein, Remploy seeks productive activities that match the skills of a disabled worker.

A binary approach still persists in some sections of society, resting on older attitudes and on bureaucratic requirements. To get an accessible parking pass, or to become eligible for disability benefits in numerous jurisdictions, one has to prove "disability" or demonstrate that one is "disabled enough", often through troubling, highly stressful bureaucratic and inflexible processes that typically involve a physician acknowledging the presence of a clinically disabling condition. Many groups and individuals that society sees as "disabled" increasingly reject the label. Among the deaf and hard of hearing, for example, a powerful Deaf culture movement rejects the disability label, identifies itself by using an upper case "D" in "Deaf" and regards itself as a cultural group. It has its own language (signing), rejects alternative ways of communication (lip reading makes unacceptable concessions to the hearing world) or cochlear implants (offering a "cure" and therefore implying that deafness is a defect that should be fixed). The assertion of an independent Deaf culture has been powerfully enhanced by the use of social media. Social media is utilized by this group to reconnect, organize and especially as a platform to demonstrate their capabilities. 5

In recent history, the most significant force in changing conceptualizations of disability has been the social model. The social model emerged in the early 1970s among a group of physically disabled men in a Cheshire home for community-assisted living in England, now a group-home alliance for the impaired operating in 55 countries (Barron & Amerena, 2007). Dissatisfied with their lack of independence and segregation within closed environments, they charged that a complex social overlay was superimposed on them without their consent simply because they happened to have an impairment. They insisted on distinguishing between impairment (their individual physical condition or defect or diagnosis) and disability (the social segregation and stigmatization imposed on all of them from the outside). Disability was characterized as a totally social phenomenon. This social model was contrasted with a previous model, identified either as the medical model (since treatment was said to be founded on medical norms), or the individual model as it focused on the individual's impairment and not on the general forces of disablement. They set up a loose association calling itself UPIAS - United Physically Impaired Against Segregation (Imrie and Edwards, 2007) - with its foundational document dated 1975. As is evident in this title, the members of the group identified as impaired, not disabled, and their main goal was integration or mainstreaming. The social model later received its best known formulation in Michael Oliver's landmark book The Politics of Disablement (1990).

Within contemporary disability studies, discussion of the social model usually revolves around its inadequacies, in particular, its inability to accommodate intersubjectivity, intersectionality, and pain, among other things (Withers, 2012; Goodley 2014). Oliver (1990) has an answer to many of these points of criticism, which Goodley (2014) has summarized; suffice it to say that much of the defense rests on deciding what lies within and beyond Oliver's "sociological critique" (Goodley 2014, p. 8). Yet it is hard to imagine social and scholarly perspectives proceeding the way they have had the social model not impacted society in the way it has over the last quarter century.

The social model has been re-stated in various forms and a number of times, usually without the essential Marxian analysis that originally underlay it. One notable geographical statement that by contrast places the Marxian element front and centre is Brendan Gleeson's Geographies of Disability (1996). Gleeson finds the origins of stigmatization and enforced segregation of disabled persons in the rise of capitalism. His claim that disability was virtually absent from medieval society seems ludicrous at first until one recognizes the insistence of the social model on separating disability from impairment. While the latter was ubiquitous in medieval society the argument advanced is that the systematic segregation of disablement awaited the arrival of capitalist society. Indeed to this day among old-order Anabaptist groups, persons with disabilities are cared for within the family and the congregation, and are not segregated. There is no doubt that forces for segregation developed powerfully in the nineteenth century and dominated discourses well into the twentieth, but it seems preferable to interpret them less as a feature of capitalist production than one of several changes which in combination have been identified as modernity (Radford 1994, 2020). An insufficient understanding of genetics led scientists to propose faulty interpretations of disability. Intensified segregation and stigmatization adopted in that era were clearly linked with an obsessive focus on diagnosis, classification, measurement, and testing, which was supported by medicine, psychology, and social science. These links are especially clear in the realms of psychiatric and intellectual disablement, and the closed custodial institutions ("asylums") they produced which have been called "icons of modernity" (Radford, 2000). A lessening of these forces, which many authors see as beginning in the 1970s, might be associated with postmodernity (Radford, 1994).

In this article we adopt a broad social model perspective, recognizing the social forces of disablement and the distinction between impairment and disability. We do not, however, adopt the strict terminological difference as its use has not gained widespread acceptance either in the disability studies literature or in society in general. The emergence of the social model broadly corresponds with the development of socially based interpretations of technological change that have been applied by Wiebe Bijker to cycling. Bijker (1995: 6) stresses the politics of technology, its impacts on gender relations, and the way "technologies are shaped and acquire their meanings in the heterogeneity of social interactions", and not in the technology itself. Here, we focus on disability rather than gender but, like Bijker, we stress the context of technological change, and while we accept that the ingenuity of individuals is sometimes important, in the case of disabled persons, collective and iterative adaptations of existing technologies have often been influential. Thinking through the intersection between social models of disability and technological innovation – we view disabling environments, material conditions, social circumstances and institutions as producing the "social" context contributing to the construction of new technologies, in this case, cycles for disabled persons.

The potential of cycles

Assumptions that a disability necessarily limits the capacity to cycle are erroneous. Many disabled persons enjoy the freedom that a bicycle grants, and ride for pleasure, recreation, health, exercise, to work, to shop, and to socialize with friends. Cycling may be liberating, even exhilarating, and allows many to join society on equal terms. Some are able to cycle on standard bicycles, but other riders may require modifications or a re-design to make the bicycle work for them.

Persons whose movement is limited, may use cycles to gain mobility within the home, the workplace, the neighborhood, public and institutional spaces and sometimes over greater distances. These machines may allow a person to travel where it was not previously possible, to avoid public transport that often poses difficulties, and achieve greater mobility so long as the necessary infrastructure such as separated lanes, ramps and lifts is installed. Despite criticism of its singular focus on wheelchairs, Guffey (2018) promotes the iconic International Symbol of Access - ![]() - to raise awareness of the accessibility issue.

- to raise awareness of the accessibility issue.

Recent research has demonstrated that cycling and similar rhythmic sports also produce several health benefits including the reduction of stress, depression, anxiety, and tension (Concordia University, 2017; Mammen and Faulkner, 2013; Oja et al. 2011). Furthermore, physical activity using cycles may forestall the need for drugs. Although generally presented as a medicalized approach, disabled persons have often themselves initiated cycling because they find it eases tensions. Therapeutic activity programs that include the use of cycles are often negotiated between patients and physicians due to their proven benefits (Oja et al. 2011; Wanner et al, 2012; Warburton et al., 2006; Wehmeier et al, 2020). Stationary machines, being very stable, put less stress on the musculo-skeletal system than walking, jogging and skiing do, since the saddle and handlebars support a substantial proportion of a rider's weight. Persons with cardiovascular problems have often taken up e-bikes, which offer electronic assistance for persons advised not to exert undue effort due to cardiovascular limitations (Bourne et al., 2018). Additionally, new cycles such as the RaceRunner have been shown to raise heart rates to levels that induce health improvements (Bolster et al., 2017; Knudsen, 2017).

Cycling requires a rider in public spaces to see the way ahead, which can pose dangers for persons with vision impairment or who have low vision, especially on roads shared with motorized vehicles. Interestingly, in the Netherlands, which has excellent cycling infrastructure, Jelijs et al. (2020) found that partially-sighted cyclists were able to ride at the same speed and distance from the curb as fully sighted cyclists. Stationary cycles and riding a tandem or a side-by-side sociable guided by a person without vision impairment is also an option.

Cycling can have a role in circumstances where fatigue and muscular dysfunction limiting movement occur as a result of autoimmune disease. Stable tricycles offers a low weight-bearing, low impact solution, and with e-assist increases local mobility (Hootman et al., 2003). Stationary bicycles are also stable, and with programmable levels of resistance a rider can fine-tune the effort required to suit their own preferences. A range of other conditions, including simply age, also affect balance. The standard bicycle obviously presents a problem for those with vertigo and related balancing issues. Inherently stable machines such as tricycles, quadricycles and wheelchairs are better suited to persons with balance problems, as are stationary bicycles.

Technical dimensions that feature in cycles designed for disabled persons

A lengthy search of published and on-line literature, including the web sites of over a dozen makers located in several countries, plus in-person interviews at the fabrication shops of two makers, and phone interviews with five users led to the identification of seven main types of cycles used by disabled persons (Hickman, 2015; Wheels for Wellbeing, 2020). 6 We recognize that variations on themes make this classification somewhat arbitrary, but we believe that it is the first historically-based classification of cycles used by disabled persons. Recently developed versions of these types make use the latest technologies and materials, but for each type we have identified antecedents indicating that users and their support groups had previously recognized a specific need and sought a technical solution, as proposed by theories stressing the social context of technical innovation.

Several overarching considerations have been recognized by designers. The machine needs to be accessible to a person who has mobility issues: this may require an open front, a low top tube, rear access, a lifting pedal, or a two-track tricycle configuration leaving the front unblocked. Stability is a common priority, often requiring a wide wheel-base, canted wheels, a low centre of gravity, and/or a (semi) recumbent riding position. Speed is rarely a priority, hence low-gearing, which makes for less resistance and ease of climbing slopes, is generally an advantage. Footstraps, calf braces for legs, seat belts and headrests are among the support devices used to position riders for a comfortable ride. Since the rider may be lower to the road and slower than most cyclists, enhanced visibility, using flags, lights and brightly colored clothing is often preferred. Comfort is also important, especially as pain accompanies many forms of disability: soft materials and massage seats, a recumbent position, and arm, leg and head supports, all may provide relief for the rider.

Pedal cycles

The standard pedal cycle can be a functional and enjoyable means of transport. In some cases, cycles with lower gears are adopted to reduce the effort required, clips may be used to hold feet in the pedals, and saddles may be replaced by more comfortable seats, but broadly they are standard cycles. Technically known as a pedomotive machine, the pedal-driven safety bicycle first appeared in the 1880s, with numerous improvements since then. Today light, strong and efficient cycles, with or without gears improve the way of life of persons with a range of disabilities. Hickman and Clement (2018) stress the enjoyment gained from riding and socializing with other cyclists.

Handcycles

Manumotive machines are cycles that are driven by riders using their arms: the rider's legs are not active. Typically, these vehicles were based on tricycles with a single front steering wheel, but some have rear steering which is a less stable arrangement. It is highly significant that Stefan Farfler, a paraplegic clockmaker based in Altdorf close to Nuremberg in Bavaria, designed the World's first recorded tricycle around 1660 (Norcliffe, 2012). 7 Farfler used his knowledge of clock gears and wheels to devise a manumotive with a drive mechanism that resembled a large clock (figure 1A). With this machine he was able to travel around Altdorf – to the Lutheran church, and to visit family and friends, hence Farfler was both maker and user. The front box was articulated to allow steering.

By the mid-nineteenth century most manumotive tricycles were driven by levers acting on a cranked axle: examples include those adapted for soldiers injured during the American Civil War (1861-65). A rider's legs rested on a bar that holds the steering steady until the rider activates the steering mechanism attached to one of the cranked levers. Another example is Charsley's ponderous manumotive tricycle of 1869 (Great Britain patent # 2451 of 1869) which does not appear to have been successful, whereas his later Velociman tricycle of 1880 was a modest success and manufactured by the Singer Cycle Company of Coventry from 1880 for 20 or more years. Manumotives proliferated after the First World War during which numerous soldiers suffered grievous damage to, or loss of their legs. By this time technology had advanced and metal tube construction with chain drive was the norm. These manumotives do not require a second person to push them, although mounting and dismounting may require assistance.

Today, efficient manumotives machines made with lightweight materials including carbon fibre and titanium allow riders to move quite rapidly, in on- or off-road settings, with their steering mechanism incorporated into the driving levers. For comfort, seating is often custom molded to the rider's body. For instance, STRAE Sport Handcycles based in Las Vegas, Nevada, are "designed by engineers and specialists seeking a safe and ergonomic cycling experience for those with spinal cord injuries, amputations, or neurological diseases" (figure 1B). Similarly, Upright Handcycles (located close to Winnipeg, Canada) and Theraplay Mobility Tricycles (located near Glasgow, Scotland) are designed for persons (especially children) with Spina Bifida and/or other conditions affecting the lower extremities. Isabelle Clement describes how a Clip-on handcycle "changed the life" of a disabled young mother who wanted to monitor a 4 year-old son who was learning to ride, as she could not keep up with him in her wheelchair (Hickman and Clement, 2018: 205).

Chair Transporters

Chair transporters range from technologies like a Bath chair, or wheeled commode (which may be pushed by a caregiver) to the rickshaw (which is pedaled by a rider) to pony and dog carts that transport a wheelchair. The person being transported gains mobility largely due to someone/something else's efforts. He or she does not contribute to the act of movement, although in many cases the rider steers the vehicle.

An early example of a chair transporter is the c.1890 3rd Marquis of Bute's "invalid carriage", a quadricycle box drawn by a pony and built by J. Waude of Leicester Square, London (he had chronic nephritis which made him visually impaired). Bute's carriage is on display at the Arlington Carriage Museum in Devon, England. The rear of the box drops down as a ramp allowing a wheelchair to be pushed up the ramp into the box, and the ramp raised and bolted in position. The passenger then drives the pony independently, and is free to choose any desired route. Somewhat different is the Bath chair, invented by James Heath of Bath, England around 1750. The passenger controls the steering but relies on someone behind to push the chair. Bath chairs dating to the nineteenth century often had a folding hood that could be raised during inclement weather, suggesting that its use was valued at all seasons and in all weathers. The Bath chair on display at the Arlington Carriage museum in Devon originally belonged to Julia Lloyd, founder of Scope (formerly know as the Spastics Society – a name significantly changed at the time the Social Model of Disability became accepted) (figure 2A). Historically, bath chairs became a common sight following major wars as large numbers of people suffered war-time injury.

A modern variation of the box transporter, except that the motive force is a cyclist riding behind the wheelchair passenger, is a variation on the Dutch cargo cycle (short box) recently adopted by Detroit's MoGo bicycle rental company (figure 2B). The MoGo has three wheels for stability, with the ramp placed at the front of the box; the passenger plays a passive role. Draisin, a German maker of cycles for disabled persons, also has a chair transporter (the Draisin Plus): it has a detachable light wheelchair fastened via a shock absorber at the front. Draisin stress that "the design of the wheelchair-bicycle combination … has evolved and matured over the years" as feedback from users was incorporated into the design (https://draisin.de/produkte), as anticipated by social models of technology.

Sociables (side-by-side)

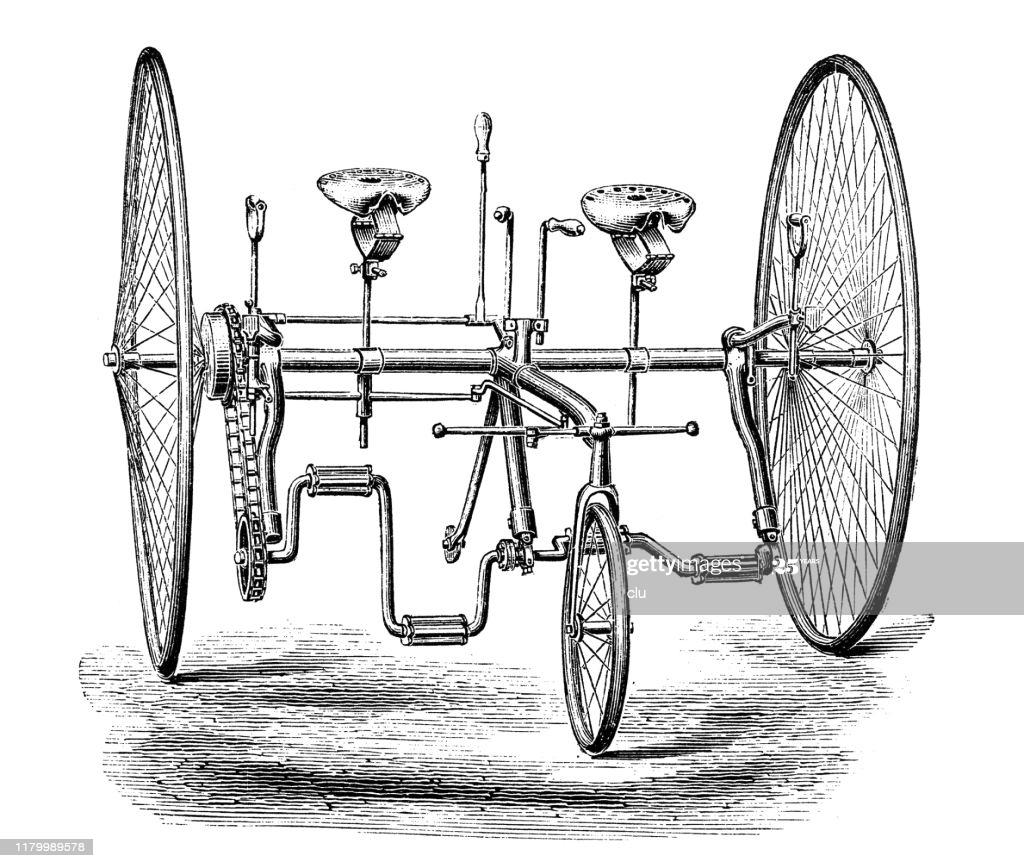

Sociable tricycles, where the riders sit side-by-side, appeared in the 1880s, mainly being marketed to courting and newly married couples. Riding side-by-side was evidently a bonding experience. But, of their nature, they offered possibilities for riders with disability. The first such model, invented in James Starley's workshop in Coventry, appeared in 1878 (figure 3A). Being heavy and wide, they would not pass through normal doors, and since the bent axle with the pedals was a single unit from side to side, both riders had to maintain the same cadence, which could stress both riders.

Recently, the sociable has reappeared as a machine tailored to persons with several kinds of disability (figure 3B). As one user who formerly transported his daughter in a trailer behind his bicycle remarked: "in a trailer I was not able to see her reactions and was afraid she would tip over and I would find her on the road. With the trailer behind I was taking her along. With a sociable - I am riding with her side by side. She smiles when she sees something and I see she smiles – and she can't speak." In practice, riding sociable models provides bonding experiences for persons with a wide range of disabilities with their family and friends.

Recent versions of the sociable tricycle such as the RickSycle (figure 3B) that are designed for disabled persons divide the axle into two separate units, so that each side of the sociable has separate gearing and the two riders can maintain different cadences. A tired rider pedals at her/his own cadence, or rests while the pilot does all the work. Some models allow the pedals to lift aside to improve access, and seat belts may be fitted for safety. Brightly colored materials are used to improve visibility.

Stability machines

Deteriorating balance and fear of falling leads many people to reduce their horizons and even become a recluse: it can induce agoraphobia. In practice, a range of cycles present persons who have trouble balancing with the possibility of re-engaging with the outdoors and with indoor exercise and appreciating a re-found mobility. Such positive outcomes offer possibilities to counter the effects of aging and a number of autoimmune diseases. Moreover, according to Bullmore (2018), this problem is rapidly increasing because modern lifestyles are producing excess cytokines leading to inflammation of major organs including the brain. Many so affected will become unstable on their feet, but will benefit from non-ballistic exercise such as cycling, provided they are securely balanced (Rissel, 2015). This is also true for people with a neuro-muscular disorder such as cerebral palsy, who, among other symptoms, can experience motor control challenges.

Two main types of stability cycles offer an alternative, stationary bicycles and tricycles. Stationary bicycles form part of the booming exercise equipment industry that offers numerous add-on gadgets, instruments and programs. Makers are continually improving their range of products in response to suggestions from users and their families. For disabled persons they present an opportunity to exercise, mostly indoors in a gym-type environment, setting their own program and pace. Stationary bicycles linked to programmed video screens showing bicycle routes in exotic settings, accompanied by soothing sounds, can make such activities pleasurable and encourage disabled persons to take an active role. These bicycles play an important role in maintaining cardio-vascular fitness and enlarging muscle mass in disabled persons, especially when recovering from illness or surgery. Bullmore's research suggests they may soon have a wider applicability.

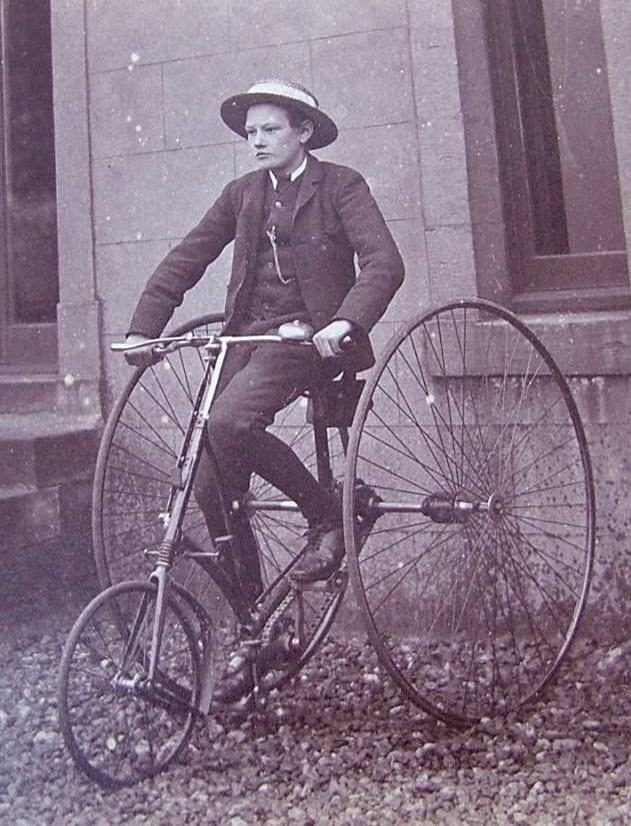

The tricycle, with its medieval roots, is an outdoor machine typically devoted to local un-programmed trips. There was a little recognized tricycle boom in the 1880s that made cycling accessible to persons with balance issues – especially the elderly, resulting in a diversity of new designs, of which the Cripper was the most successful (figure 4A). As early as 1897, Siegfried was using tricycles to conduct treatments on patients with ataxia to help them regain some muscle control (Siegfried, 1902, p.10-11). His work formed part of the medicalized approach to disability noted above, but his results did encourage work on therapeutic treatments. Since that time tricycles have been used to treat patients both inside and outside the asylum.

Adult tricycles have a wide wheelbase making them stable and well-adapted "to the requirements of women and elderly men" (Bijker, 1995, p.56). Many have baskets behind or up-front so that riders can use them to carry shopping goods and assorted articles. They present moderate exercise opportunities for persons with a wide range of disabilities. Persons with Down Syndrome, for instance, find the stability of tricycles calming (Hayden, 2016), as do the elderly who are making increasing use of them, especially in places with mild winters such as Florida and California.

An example of a stable tricycle is the Adventurer, made by Freedom Concepts of Winnipeg, MN. This tricycle has back support, foot straps and an extra wide split back axle with one driving wheel and one freewheel, thus avoiding a differential. Despite the high riding position, it is hard to tip, it has very low gearing and Velcro straps which hold feet on the pedals. A seat belt keeps the rider in the high seat. In an interview, Freedom stressed that their designs are constructed in consultation with medical professionals, therapists, and the families of users, and that further customization is always possible (https://www.freedomconcepts.com/about-us/ accessed 26/6/2020).

A recent addition to the range of stability machines, the Petra Bike or RaceRunner is, in practice, a version of the World's first bicycle, the laufmaschine or draisine invented in 1817 by Karl von Drais (Lessing, 2003), and its British successor, Denis Johnson's Pedestrian Accelerator of 1818 (Street, 2011). The RaceRunner was invented in Denmark by the Danish wheelchair athletes Connie Hansen and Mansoor Siddiqi (Hornbæk, 2017) (figure 4B). It illustrates the social construction of technology by conjoining athletics, user needs and invention. A RaceRunner has a lightweight tubular frame with 2 inclined rear wheels and a front steering wheel, handlebars, a chest plate (almost identical to the front "body rest" of Johnson's lady's hobby horse (Street, 2011, 129-135), and a saddle. Sitting on the saddle, users propel themselves forward by walking or running (Donnell et al., 2010).

The RaceRunner can be used for everyday transport purposes, for leisure, as a training device, and for sport (RaceRunning is now a sport in the Paralympic Games). Although originally developed for people with cerebral palsy, it can be utilized by persons with poor balance, reduced trunk control, restricted range of movement, and/or limited walking abilities. With adjustable components and equipment, the RaceRunner is customized to fit the user's anatomy and mobility preferences (walking vs running). Both psychological and physical health effects have been found in preliminary studies of individuals with cerebral palsy: several weeks of training with a RaceRunner positively affected bone health, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscle growth (Bryant et al., 2015; Hjalmarsson et al., 2020).

Tandems

A tandem has two passengers, normally with a pilot up front and a stoker behind, although these positions may be reversed in the case of disabled persons. Guided by an experienced pilot, riders with a range of disabilities can enjoy a ride. Persons who are vision impaired, have muscular dystrophy, or with various forms of dementia and memory loss are thereby able to exercise, visit the city or countryside, or travel to a specific destination. An interviewee in Missouri state recalled riding tandem regularly with an elderly cycling friend who had advanced dementia and no longer even recognized the interviewee; the passenger was "strong as an ox, and happily pointed out everything we passed, although he had no inkling of where he was". Very different were the experiences of a much younger interviewee from a Lyon suburb who was taking regular tandem rides by volunteers from a local cycling club. Lacking sight, his other senses clicked in and he would enthusiastically remark on the sun and wind on his skin, the smell of the vineyards and pine forests, and the sound of birds.

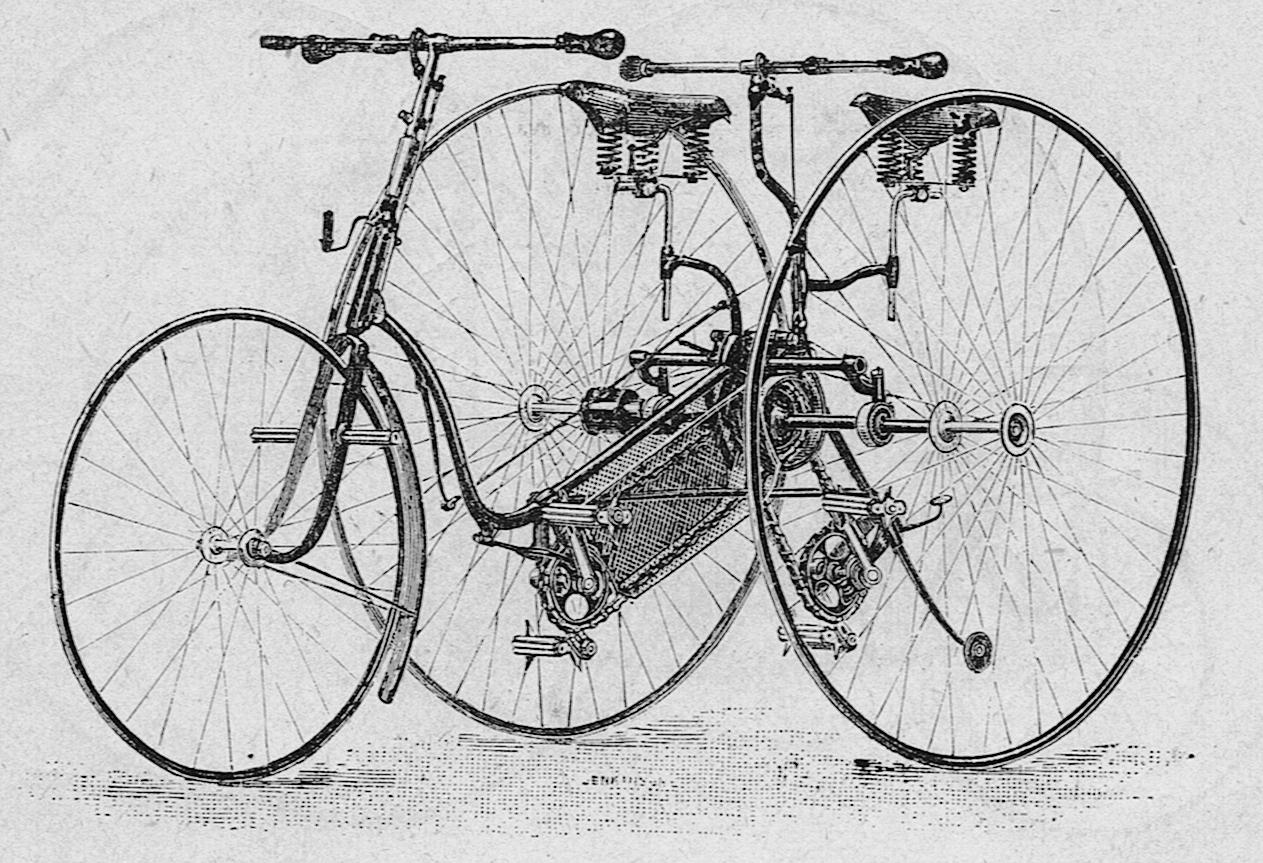

A limitation of the classic tandem such as the Marlboro' Club Tandem tricycle (figure 5A) is that the stoker and pilot have to maintain the same cadence, which may require a compromise over speed between the two riders; newer models with clutch drives allow independent pedaling, although when tandem riders pedal at different cadences the asymmetry of movement affects balance. A recent advance, technically, is the Circe Cycles Helios tandem made in Cambridge, UK that, with low step-over height and easy size adjustment, allows both young and adult riders to exercise. The Hase Bike Company of Bochum in Germany includes in its range of bikes the Pino, which places the front rider in a low semi-recumbent position, with the pilot behind and above (figure 5B): the Tour version of the Pino empowers disabled persons to undertake long-distance tours.

Power-assisted bikes

Although the e-bike is seen as a recent innovation, in practice power-assisted cycling has a longer history. Earlier attempts failed to gain a commercial foothold, unless the motorcycle and automobile are conceived as power-assisted bikes! The Michaux-Perraux steam velocipede of 1868 was the probably the first power-assisted bicycle, followed by Lucius Copeland's prototype steam bicycles of 1881 and 1884, and a steam tricycle of 1888. These prototypes were not intended for use by disabled persons, but in the twentieth century, battery powered tricycles (using cells similar to car batteries) were adopted by persons with mobility difficulties. R.A. Harding Company of Bath (UK) launched a motor and battery powered tricycle in 1926 widely used by disabled persons: some models with rear-mounted, small motors and batteries were clearly power-assisted cycles, whereas other models, such as the Pultney, were small cars and therefore fall outside the remit of this paper.

More recently, e-bikes – with both on and off-road applications, have been widely adopted, especially by older riders. According to the Electric Bike Review about 85% of the World's e-bikes are now made in China with the remainder (more high-end) made in Taiwan and Europe. 8 Electric-assisted vehicles have been welcomed by the disabled community, and particularly the elderly who find pedaling up-hill or into the wind too strenuous, but otherwise can cope. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has raised critical issues with e-assisted vehicles. Do they count as mobility devices and can they be used, for example, on trails posted "no motorized vehicles", or for parking in places reserved for disabled persons? Exchanges in The Electric Bike Review forum (19 January 2020) indicate that despite ambiguities over which set of regulations apply, the ADA appears to guarantee equal access to public spaces for all persons with a mobility disability. 9

Conclusion: social models revisited

One of the specialized makers (Freedom) use the term "adaptive" to describe their cycles; they state: "each bike is built to the person and their special needs" adding that "any bike can be further customized and adjusted to the exact specifications and unique requirements of the rider, ensuring that each Freedom Concepts bike is a perfect fit". 10 These cycles address the needs of specific users whose input therefore has to matter to their designers. In interviews we found that all makers regularly interact with purchasers (users and their families), and over time make design modifications based on feedback (social exchange). One maker (interview at RickSycle of London, Ontario) reported 5 rounds of modifications as users responded to their design changes, while Theraplay claimed it had conducted 40,000 assessments as riders test out the suitability of their models. 11 And most machines are offered with "options" that a user can add-on if it seems appropriate. The Dutch maker of specialized cycles, Van Raam, allows purchasers to configure their bike on-line. 12 This adaptive strategy simultaneously empowers users by tailoring a bike to their needs, which increases mobility and, therefore, their ability to engage in daily life.

Many small makers came to the activity because of individual, family or community needs, hence their interest in the project is necessarily socially motivated. Theraplay "was approached by a local charity working with children with Spina Bifida and was asked to design and produce a hand driven tricycle for … children with this condition", while Freedom Concepts received a request to build a cycle for a child with cerebral palsy. MoGo of Detroit stated that they exchange information on cycles for disabled persons with bicycle sharing schemes in several other cities that have recently launched an adaptive component, including: Portland's Adaptive Biketown, Milwaukee (Bublr Bikes), Capital Bike Share (Washington D.C.), Heartland Bike Share (Lincoln, NE), the Bay Wheels Bike Share (Oakland, CA), and Seattle, WA. In short, they have formed a network of biking sharing organizations that caters to riders with special needs, giving them more control over their lives.

This article complements the research of Inckle (2019) on disabled cyclists and the unfortunate tendency to focus on user's deficits rather than the possibilities located at the intersection of disability and cycling. We have taken a socio-historical approach to trace this relationship between cycling and disability over several centuries and in doing so clearly demonstrate the possibilities for innovation and activity and personal mobility that can arise from centering disability in processes related to the design and use of cycles. We do this by drawing on two closely related social models. The social model of disability challenges the individual nature of disability, rejects binary interpretations and invokes the social context for addressing disability. Applied to the use of cycles, we find that numerous technical adaptations have been made to work for individual needs, often proposed by disabled persons themselves.

The SCOT model emphasises the interaction of makers and users in prioritising projects and in developing and adapting technologies. As the interviews demonstrate, makers pay careful attention to social needs in designing products and adapting technology. Users, family members and their friends react to designs and prototypes, suggest modifications and in some cases recommend total rejection. This learning process requires innovation, modification, acceptance, and rejection: the ultimate test is whether the final user likes and purchases the artefact. As we have noted, all of the makers we have contacted confirm that the design of their bicycles is an interactive process as known technologies are re-jigged to match the needs of the individual, and then modified – often on several occasions - as users provide feedback. Several makers customize their cycles and a few now allow buyers to incorporate a range of modifications on-line.

Our aim in this article has been to connect the needs and desires of disabled persons with the development of cycles. In practice, we find quite a close socially-driven connection. Cycles have been adapted to work for disabled persons since the pre-industrial era and, by incorporating new materials and technologies, significant improvements in the functionality of cycles have resulted. The seven basic types of cycles – the standard pedal bicycles, hand bikes, chair transporters, sociables, stability machines, tandems and power-assisted cycles - have all been used by disabled persons for over a century. This is not a surprising discovery: the bicycle has long been adapted to a variety of uses, from military/paratrooper bicycles, to delivery cycles, to ice cream sales, to field ambulance, to indoor fitness machine, to transporter to work, to study, shop and play. A cycle is evidently an artefact that lends itself to adaptation.

Unfortunately, the possibilities offered by cycles to disabled persons have not been as widely recognized as might be hoped. Adoption has been slow, perhaps because of the high cost of some of the more advanced machines, 13 but new lightweight materials, electronic gearing and increasing comfort make cycles more user-friendly. As Wheels for Wellbeing, an advocacy group based in London (UK) laments, the two main obstacles they face are social ones. This advocacy organization "spends most of its time … convincing disabled people that they can cycle … and convincing everyone else, from family members to government ministers, that disabled people can, and do, cycle, and that disabled people need to be included in cycling policy and design guidance" (Hickman and Clement, 2018, 207). We have shown that many improved cycling technologies are now available to disabled persons, and that those who have taken advantage of the resulting possibilities have found satisfaction and pleasure in so doing.

Conflict of Interest & Disclosure Statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and no financial interest or benefit arising from the direct applications of this research.

Bibliography

- Andrews, N., Clement, I., & Aldred, R. (2018) Invisible cyclists? Disabled people and cycle planning – a case study of London, Journal of Transport & Health, 8(2), 146-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2017.11.145

- Barron, T. & Amerena, P. (2007) Disability and Inclusive Development. London: Leonard Cheshire Foundation International.

- Bashford, A. and Levine, P. (2010) The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bijker W. (1995) Of Bicycles, Bakelites, and Bulbs: Towards a Theory of Sociotechnical Change. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bolster, E. A. M., Dallmeijer, A. J., de Wolf, G. S, Versteegt, M., & van Schie, P. E. M. (2017) Reliability and Construct Validity of the 6-Minute Racerunner Test in Children and Youth with Cerebral Palsy, GMFCS Levels III and IV. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics 37 (2), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2016.1185502

- Bombastic Spastic (2011) A short history of Remploy. http://bombasticspastic.blogspot.com/2011/08/remploy-was-set-up-under-1944-disabled.html accessed 8 May 2019.

- Bonham, J. and Johnson, M. eds. (2015) Cycling Futures. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press. https://doi.org/10.20851/cycling-futures

- Bourne, J. E., Sauchelli, S., Perry, R., Page, A., Leary, S., England, C., & Cooper, A. R. (2018) Health benefits of electrically-assisted cycling: a systematic review. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(1) 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0751-8

- Bryant, E., Cowan, D. & Walker-Bone, K. (2015) The introduction of Petra running-bikes (race runners) to non-ambulant children with cerebral palsy: a pilot study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 57 S4, 34–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12780_23

- Bullmore, E. (2018) The Inflamed Mind: A Radical New Approach to Depression. (London: Short Books).

- Buliung, R., Bilas, P., Ross, T., Marmureanu, C., & El-Geneidy, A. (2021) More than just a bus trip: School busing, disability and access to education in Toronto, Canada, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 148, 496-505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2021.04.005

- Clayton, W., Parkin, J., & Billington, C. (2017) Cycling and disability: A call for further research. Journal of Transport and Health, 6 (2017), 452-462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2017.01.013

- Concordia University (2017) Feeling stressed? Bike to work: Study shows how a pedal-powered commute can set you up for the whole day. Science Daily (21 June 2017), retrieved June 26, 2020 from www.sciencedaily.com/

- Dolmage, J.T. (2017) Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press). https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9708722

- Donnell, R. O., Verellen, J., van de Vliet P. & Vanlandewijck, Y. (2010) Kinesiologic and metabolic responses of persons with cerebral palsy to sustained exercise on a Petra race runner. European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity, 3(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.5507/euj.2010.001

- Edwards, F. (1999) Remploy: A Very Special Company. London: Krystyna Dunn Associates.

- Gleeson, B. (1996) Geographies of Disability. London: Routledge.

- Goodley, D. (2014) Dis/Ability Studies: Theorizing Disableism and Ableism. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203366974

- Guffey, E. E. (2018) Designing Disability: Symbols, Space and Society. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350004245

- Hansen, N. & Philo, C. (2007) The normality of doing things differently: bodies, spaces and disability geography. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 98(4), 493-506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2007.00417.x

- Hayden, D.M. (2016) "Effects of adapted tricycles on quality of life, activities, and participation in children with special needs." https://thescholarship.ecu.edu/bitstream/handle/10342/5649/HAYDEN-HONORSTHESIS-2016.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Hickman, K. (2015) Disabled cyclists in England: imagery in policy and design. Urban Design and Planning, Institute of Civil Engineers https://doi.org/10.1680/udap.14.00048

- Hickman, K. & Clement, I. (2018) Cycling and disability. Cycle History 29, 205-207.

- Hjalmarsson, E., Fernandez-Gonzalo, R., Lidbeck, C., Palmcrantz, A., Jia, A., Kvist, O. et al. (2020) RaceRunning training improves stamina and promotes skeletal muscle hypertrophy in young individuals with cerebral palsy. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 21, 193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03202-8

- Hootman J.M., Macera C.A., Ham S.A. et al (2003) Physical activity levels among the general US adult population and in adults with and without arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 49,129–135. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10911

- Hornbaek J. M. (2017) The History of RaceRunning. In M. Siddiqi & J.M. Hornbaek (Eds.), Coaches' Manual: RaceRunning (1st Edition) (p. 6-8) Parasport: Denmark.

- Imrie, R. & Edwards, C. (2007) Geographies of disability: reflections on the development of a sub-discipline. Geography Compass 1(3), 623-640. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00032.x

- Inckle K. (2019) Disabled cyclists and the deficit model of disability. Disability Studies Quarterly 39(4) open source. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v39i4.6513

- Jelijs, B., Heutink, J., & de Waard, D. (2020) How visually impaired cyclists ride regular and pedal electric bicycles. Transportation Research, Part F, Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 69(1), 251-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2020.01.020

- Knudsen, S. (2017) The RaceRunner and its Possibilities. In M. Siddiqi & J.M. Hornbaek (Eds.), Coaches' Manual: RaceRunning (1st Ed.) (p. 9-16). Parasport: Denmark.

- Lessing, H-E (2003) Automobilität: Karl Drais und die Unglaublichen Anfänge. (Leipzig: Maxime).

- Mammen, G., & Faulkner, G. (2013) Physical activity and the prevention of depression: a systematic review of prospective studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(5), 649-657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.001

- Norcliffe, G. (2009) G-COT: The geographical construction of technology. Science, Technology and Human Values, 34(4), 449-475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243908329182

- Norcliffe, G. (2012) Before geography? Early tricycles in the age of mecanicians. Cycle History 22: Proceedings of the Twenty-Second International Cycle History Conference (Quorum Press: Cheltenham) 86-99.

- Oja, P., Titze, S., Bauman, A., de Geus, B., Krenn, P., Reger-Nash, B. & Kohlberger, T. (2011) Health benefits of cycling: a systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 21(4), 496-509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01299.x

- Oliver, M. (1990) The Politics of Disablement (New York: Macmillan). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20895-1

- Oliver, M. (1999) Capitalism, disability, and ideology: A materialist critique of the Normalization principle. In R.J. Flynn and R. Lemay (Eds), A Quarter-century of Normalization and Social Role Valorization: Evolution and Impact. (University of Ottawa Press: Ottawa) p.163-173. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1cn6s45.8

- Oliver, M. (2009) Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice. (Houndmills: Palgrave-Macmillan).

- Oliver, M. (2013) The social model of disability: thirty years on. Disability and Society 28(7), 1024-1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.818773

- Oudshoorn, N. & Pinch, T. J. (2003) How Users Matter: The Co-construction of Users and Technologies. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3592.001.0001

- Park D. & Radford, J. (1998) From the case files: reconstructing a history of involuntary sterilization. Disability and Society 13(3), 317-342. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599826669

- Pinch, T. J. and Bijker, W.E. (1984) The social construction of facts and artefacts: or how the sociology of science and the sociology of technology might benefit each other. Social Studies of Science 14(3), 399-441. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631284014003004

- Radford, J. (1994) Intellectual disability and the heritage of modernity. In M.H. Rioux and M. Bach (Eds.) Disability is not Measles: New Research Paradigms in Disability (Toronto: Roeher Institute), 9-27.

- Radford, J. (2000) Academy and asylum: power, knowledge and mental disability. In R.H. Brown and T.D. Schubert (Eds.) Power and Knowledge in Higher Education (New York: Columbia University Press), 106-126.

- Radford, J. (2020) Towards a post-asylum society. In Brown I. et al (Eds.) Developmental Disabilities in Ontario (4th Edition) Toronto: Delphi Graphic Communications, 25-40.

- Rissel, C. (2015) Health benefits of cycling. In J. Bonham & M. Johnson (Eds.) Cycling Futures. (Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press) p. 43-62. https://doi.org/10.20851/cycling-futures-03

- Rocco, T. S. editor (2011) Challenging Ableism, Understanding Disability, Including Adults with Disabilities in Workplaces and Learning Spaces (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass).

- Ross, T. & Buliung, R. (2019) Access work: Experiences of parking at school for families living with childhood disability, Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 130, 289-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.08.016

- Shakespeare, T. (1996) Review of An Anthropologist on Mars by Oliver Sacks, (London: Picador)", Disability and Society 11(1), 137-139.

- Schalk, S. (2013) Coming to claim crip: disidentification with/in disability studies. Disability Studies Quarterly, 33(2) https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v33i2.3705

- Siegfried, M. (1902) Tricycling as an Aid in Treatment by Movement and as a Means of Carrying Out Resistance Exercise. (Leipsic (sic); Georg Thieme) (translated by Louis Elkind: 22 pages) https://wellcomecollection.org/works/aef3z83r

- Street, R. (2011) Dashing Dandies: The English Hobby-Horse Craze of 1819. (Christchurch, Hants: Artesius Publications).

- Thomas, C. (2004) Developing the social relational in the social model of disability: a theoretical agenda. In C. Barnes & G. Mercer, G. (Eds.) Implementing the Social Model of Disability: Theory and Research. (Leeds: Disability Press).

- Wanner, M., Götschi, T., Martin-Diener, E.,Kahlmeier, S. & Martin, B.W. (2012) Active transport, physical activity, and body weight in adults: a systematic review." American Journal of Preventive Medicine 42(5), 493-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.030

- Warburton, D.E., Nicol, C.W. & Bredin, S.S. (2006) Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal 174(6), 801-809. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051351

- Wehmeier, U. F., Schweitzer, A. & Jansen, A. (2020) Effects of high-intensity interval training in a three-week cardiovascular rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 34(5), 801-809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215520912302

- Wheels for Wellbeing (2020) Types of Cycles. https://wheelsforwellbeing.org.uk/types-of-cycles/ accessed 11 November 2020.

- Withers A. J. (2012) Disability Politics and Theory (Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing).

- Wolfson, P. L. (2014) Enwheeled: Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, and Parsons The New School for Design. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.parsons.201511240747

- Wong, A. (2020) Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century. New York: Vintage Books).

- World Bank (2021) Disability Inclusion. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disability accessed 26 March 2021.

Endnotes

-

Although search engines reveal a large literature on cycling and disability, approximately 95% of the 600+ articles were published in medical, health and sport science journals, mostly examining bio-medical responses to specific test exercises. Very few examine the development and uses of different types of bicycle, and their technological and social potentials.

Return to Text -

We developed this genealogical classification independently (believing this had not previously been attempted) but subsequently discovered that the Wheels for Wellbeing organization in the UK has proposed an alternate functional typology – (https://wheelsforwellbeing.org.uk/types-of-cycles/ accessed 5/11/2021).

Return to Text -

Oliver (1999), a political economist, differs by arguing that disability and rehabilitation are categories necessarily produced by and for capitalism, in contrast to contributors to Rocco's volume (2011) who seek to shift understandings of disability from medical and economic interpretations to a social justice concern.

Return to Text -

We exclude discussion of wheelchairs for which there is already a solid literature. However, we would like to note that several technologies – especially light strong spoked cycle wheels – have been adopted by wheelchair designers (Wolfson, 2014).

Return to Text -

https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/how-social-media-became-a-game-changer-for-the-deaf-community/514223/

Return to Text -

Lock-downs due to the Covid-19 pandemic prevented further personal interviews soon after our project was launched.

Return to Text -

He also designed a quadricycle.

Return to Text -

https://electricbikereview.com/ accessed 30/06/2020.

Return to Text -

Electric Bike Review 19 January 2020 www.electricbikereview.com/forums/threads/does-the-ada-supersede-local-restrictions-on-ebikes.31655/ accessed 15/9/2020.

Return to Text -

Freedom Concepts Inc. (2020) www.freedomconcepts.com accessed 15/9/2020.

Return to Text -

Theraplay Cycles for Life (2021) www.theraplay.co.uk accessed 15/9/2020.

Return to Text -

Vanraam let's all cycle (2021) www.vanraam.com/ accessed 15/9/2020.

Return to Text -

For instance, the Bowhead Adventure E-Bike costs $14,999.

Return to Text