This paper will describe an artist-curatorial project by Fayen d'Evie and Georgina Kleege, working with the collection of the KADIST Art Foundation in San Francisco to investigate the radical potential of haptic criticism and tactile dialogue.

Introduction

Prior to the early 1800s, touch permeated accounts of aesthetic appreciation, and permissive handling was routine for visitors encountering collections of artistic curiosities. 1 As museums of art evolved into conduits for civic education, charged with edifying and enlightening the masses, deferential models of visitor behaviour were introduced forbidding touch. Though originally entangled in nineteenth-century politics of gender, race, and class control, these behavioural codes transcended their archaic roots, morphing into securitised 'Hands off!' policies in contemporary settings, and social taboos self-censoring the touching of artworks (Candlin, "Don't Touch"). These norms are rarely subjected to rigorous interrogation. Touch tours for blind people provide a partial exception. Yet touch tours are normally treated as exclusive, personal experiences - as protocols to meet baseline access obligations - rather than being valued for their contributions to public cultural discourse.

This paper chronicles the first phase of an experimental, dialogic project that extrapolates from the experience of touch tours to develop critical positions, methodologies and vocabulary to texture contemporary haptic criticism and tactile aesthetics. Our work is informed by the scholarship of Fiona Candlin and Constance Classon; the curatorial practices of Amanda Cachia; and the artistic interventions of Carmen Papalia among others. 2 Interacting with collections, and creating new responsive artworks, we have mobilised curators, conservators, researchers and public audiences to experiment in tactile encounters and intersensory translations. In this paper, we deal with the formative phase of the project, as we worked "hands-on" with the collection of the KADIST Art Foundation in San Francisco. A dialogic ethic has propelled our collaboration and also structures the narrative of this essay. Speaking in turn (blurred through intersubjective editing interjections and annotations), we foreground our personal connections to the project, trace our meeting of minds and politics in asserting the perceptual and social value of touch, and share tactile and conceptual discoveries as we navigate our resistance to ocularnormative civility. 3

GK: The Normative Touch Tour

I grew up in the art world. Both my parents were visual artists. I was diagnosed as "legally blind" when I was eleven, and though I retain a degree of residual vision, I am accustomed to exploring objects haptically and to scanning surfaces digitally for texture and temperature. In addition to these tendencies, which may be common to many blind people, I was familiar with the media, techniques and tools of my parents' works. My father was a sculptor who worked primarily in metal, so I learned not only to haptically trace the abstract forms of his constructions, but also to recognize the textural qualities of different finishes. My mother was a painter. I often helped her stretch and prime her canvases and was familiar with her preferred practices for mixing and applying pigments.

Whenever I get the chance, I leap at the opportunity to get my hands on art. I have availed myself of touch tours in museums in North America, the UK and Europe, and while I have my preferences and pet peeves about the way these tours are conducted, I always get something out of the experience. 4 The best touch tours allow me to employ the full range of my "handsy" tendencies and to draw upon my aesthetic background. Whether through a live docent or a recorded audio guide, the best touch tours direct the hands of the beholder to facets and features that are not visible to the eyes alone. They may describe the tools and techniques the artist used to achieve certain textural effects, or to construct the form as a whole. They may also draw attention to the invisible traces of damage and repair which speak to the longevity and value of the piece. But unfortunately, touch tours are usually rushed. This timing seems to coincide with the temporality of a typical sighted visitor's pace through a museum—pause, look, move on. So sometimes there is only time for a brief stroke or pat of a work, and the cursory exploration tends to focus on recognizing the objects depicted rather than on their individual haptic features.

Less successful touch tours assemble groups of blind people during hours or days when the museum is closed to the general public. I recognize the practical expediency of this design, since the logistics of guiding a group of blind people through a gallery crowded with other visitors can be daunting. Still, I resent the segregation. Museums are public institutions; blind people are part of the public too. Yet blind people, like people with other disabilities, often find ourselves siloed into special groups or programming in ways that reinforce our marginal status. One reason that museums may keep touch tours out of sight of the general public is a fear that everybody wants to get their hands on art. To be fair, I have never been on a public touch tour when this issue has not come up. Docents and guards are compelled to shoo sighted visitors away as they reach out to feel something I've just been touching. Strangers will stand and watch me and sometimes even ask me what it feels like to touch the art. Sometimes I've been asked to refrain from touching until after a group of children has passed through the gallery. While adults can be expected to comply with the "only for the blind" rules, there's an expectation that children might not recognize my exclusive status, and will feel deprived if they see me touching while they cannot.

Whether they are good or bad, standard museum touch tours systematically fail to capture and collate the responses of the privileged few who enjoy this exceptional access. I always feel like I come away from even the least successful touch tours, with something of value to communicate to sighted art lovers. It is precisely the aspects of the work that are not available to the eyes alone that I believe can enhance a sighted viewer's appreciation. I ask, since not everyone is allowed to touch the art, why not include tactile and haptic details in descriptive labels, wall text, and catalogues? Why not employ blind docents to conduct tours where they touch the art and describe the experience to people who are not allowed to touch?

F d'E: Inciting Tactile Encounters

My unusual relationship to seeing has long been part of the private process of my artmaking, whether through a myopic privileging of micro-textures, or a partiality to chromatic fluctuations and fugitive affects. A few years ago, as the degeneration of my functional vision accelerated, I began to claim my unstable vision more explicitly as a central force in my artistic practice. For a solo exhibition in Melbourne, Australia, I constructed an installation of tactile paintings entitled Not All Treasure is Silver and Gold, Mate, abstract compositions that referenced perception and language (d'Evie). 5 The paintings were mounted on freestanding plywood walls, which functioned as the theatrical architecture for two oratory performances of short fiction dealing with visual assumptions of value, which I wrote and performed together with two actors from the Theatre of the Blind. The exhibition coincided with a visit to Melbourne of Devon Bella, then Curator of Collections at KADIST in San Francisco, who encouraged me to extend my work. She had followed Georgina Kleege's writings on blindness and art for some years, and offered to facilitate a personal introduction.

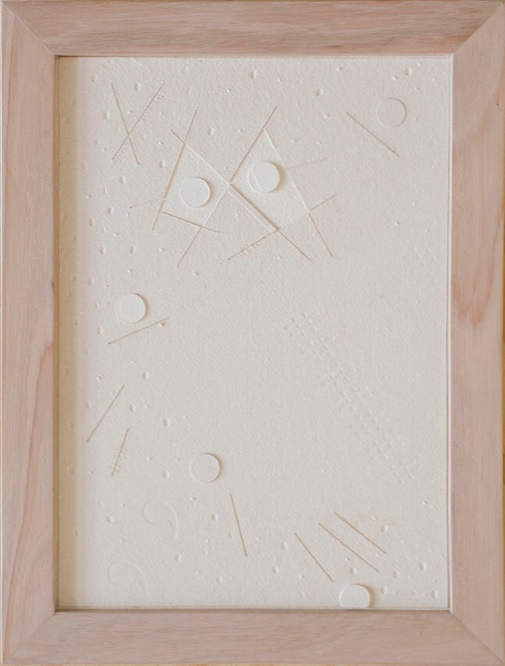

Fig. 1. Fayen d'Evie, 2015. Not All Treasure is Silver and Gold, Mate. West Space, Melbourne. Photo: Tobias Titz.

Two colour photographs side by side. The left-hand photograph documents a rectangular, portrait-oriented painting constructed from collaged paper stocks, some painted with textural acrylic paint or ground pumice. There are knife cuts and embossing on some of the surfaces of the painted paper. The painting composition is abstract: angular lines and circles fall from the top right-hand corner, in a sweeping motion, curling down towards the lower right-hand corner. The painting is framed in a pale wood, with a light grain. The right-hand photograph documents two hands exploring the surface of a cropped detail of a painting constructed from collaged, painted paper stocks. A smaller hand rests over a larger one, which is palm towards the painting, touching circular forms.

I met Georgina a few months later at her sparse office in Berkeley. As an opening gambit to conversation, I confessed to a crucial failing of my Melbourne exhibition: a lack of touch. I had crafted the paintings from collaged layers of embossed paper and linen, painted in textured shades of white and off-white. 6 I had assumed that over the course of the exhibition, the visual and tactile aesthetic of the paintings would both shift, as fingerprint grease smeared the surfaces, and tactile agitation frayed vulnerable edges. But by the end of the exhibition, the paintings were barely different to their opening state. A few people later confessed that they had refrained from touching so as to avoid damaging the work, preferring to use Instagram to capture a visual memory. One artist confided that he had felt uncomfortable handling the paintings while others were looking, while also admitting that on past occasions, he had surreptitiously fondled other artworks to check material textures. 7 Georgina and I talked about how audiences have internalised touch as transgressive, and she raised her frustration that ocularcentric dominance over cultural encounters had stifled public discussion of tactile qualities. Even when Georgina attempted to put her experience of touch tours into words, she was struck by a poverty of language: "Even as a blind person, I have a vast vocabulary to describe visual aesthetic experience, but when I talk about touch I fall back on sets of binary adjectives: hard/soft, smooth/rough, warm/cool, etc. I crave greater complexity and precision" (Kleege, "Kadist Proposal"). We surmised that the entrenching of the "hands off" policies had promoted tactile amnesia within dominant art historical accounts, and had impeded non-ocular perceptual discoveries, leading to a loss of language to discuss tactile aesthetics. We proposed to Devon Bella that the three of us work with the KADIST collection in a dialogic and experimental way to generate descriptive and conceptual vocabulary for a contemporary tactile aesthetics. A political aim was also explicit: through our activities, we would engage specialist and public audiences in reflection on the ocularcentric norms of exhibiting, and on the social politics and radical potential of contemporary tactile aesthetics.

Devon took the lead on the first stage of the project, auditing the KADIST collection to refine a shortlist of works for haptic encounters. We were interested in works that spoke to the social history or politics of touch, and works that were materially diverse, with textural, compositional, or tactile traces of haptic making. We were also intrigued by structural tensions and limits: works that were conceptually or materially relevant, but that Devon preferred to exclude from handling because of preservation or other concerns.

GK: Experiments in Tactile and Haptic Encounter

From the shortlist of possible works, four were selected for a one-day, public exhibition: A meditation on the possibility… of romantic love or where you goin' with that gun in your hand, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton discuss the relationship between expressionism and social reality in Hitler's painting (2005) by Daniel Joseph Martinez; From a Whisper to a Scream (2005) by Juan Capistran; Untitled (Grate I/II: Shan Mei Playground/ Grand Fortune Mansion) (2012) by Adrian Wong; and Third Realm (2011) by Jompet Kuswidananto. A week before the event, we met at KADIST to experiment with methods of tactile encounter. Not surprisingly, a great pleasure in this research was having the luxury of more or less unlimited time to spend with these works. As mentioned above, even the best museum touch tour has to keep to a schedule and there is seldom an opportunity to backtrack and re-handle a previous item. At KADIST, we were able to examine each piece in minute detail, and then move back and forth between pieces, to revise and refine initial observations. Our first discovery was that each artwork invited or incited a different kind of touch, and offered different kinds of rewards.

Martinez's piece consists of two marble forms, each about eighteen inches tall and two inches thick, with flat polished surfaces, and ridged sides. The forms are based on the iconic photograph of Seale and Newton, in their leather jackets and tilted berets, standing before the Black Panther Party sign. In Martinez's rendering, the two men are reduced to flat, silhouette cut-outs. The piece encouraged a delicate tracing motion with the fingertips. Initially, this felt like the standard touch tour where the point is to identify the object depicted. Tracing the outlines made it clear that we were dealing with silhouettes of two human figures. Without the title or the iconic photograph that the artist is referencing, there was little to indicate that the two figures were the Black Panther leaders. Still, the marble's thickness and persistent coolness (even after prolonged handling the stone did not warm up), conveyed a sense of memorial reverence. This is the material of classical sculpture and of tombstones.

Capistran's piece consists of folded dollar bills mounted in a felt-lined, trench-like vitrine. The bills are in pairs, as if in a didactic origami diagram, illustrating how two-dollar bills can be folded and intertwined into the shape of a gun. With this piece, we undertook to recreate the folding process to arrive at the end result of the dollar-bill hand gun. We approached the artwork as if it was a set of step-by-step instructions, beginning with the unfolded bills and then carefully following the procedure, folding, unfolding, comparing our version with the original as we made and corrected errors. The size and texture of the bills was familiar, but the handling process transformed them from quotidian commercial tokens to a medium of construction. Needless to say, the process was not as easy as it looks. It was like learning origami, and was so engrossing, so satisfying as we completed each step correctly, that when the gun finally emerged it came as a kind of shock, even though we had known all along that this was where the process was meant to end up. The surprise connecting the dollar bills with the hand gun reinforced the underlying themes of the piece. (Later, a participant on the touch tour would comment that when he looked at the piece he "got it" right away, but he could imagine that doing the folding would make the piece more meaningful.)

The work by Wong is a metal form mounted on the wall, compositionally suggestive of an abstract painting. The form consists of two layers of fabricated metal, each a distinct geometric pattern. This work elicited the impulse to grasp with the whole hand, even to pull and shake with the whole arm and upper body. The cool metal of the bars, and the thickly applied paint were familiar, but the rough, even sharp edges at the joints reinforced the sensation of hidden violence. The layering of the two sections invited the hand to attempt to slip through the gaps, but these explorations were often thwarted by the bars underneath. From a distance, the piece looks like an abstract geometrical construction, but our up-close manual investigations foregrounded the purpose of gates to forcefully keep out or keep in.

The hanging installation by Kuswidananto invited a combination of all these techniques. In this piece, the bodies of three horses are sketched through suspended elements—bridles, with blinders and dangling reins, saddles with stirrups, and horsehair tails—referencing a mythical parade around the palace of Yogyakarta. The stitching and buckles on the bridles and saddles invited a dextrous manipulation as with the Capistran piece, while the leather surfaces encouraged palming and stroking. There was even a kind of tracing gesture as we drew the invisible lines to outline the missing bodies of the horses. Any touch set the hanging elements gently swinging, animating what we came to call "the ghost horses." This was enhanced by kinaesthetic, proprioceptive whole-body movement around and between the horses. There was a powerful suggestion of the presence of the horses that compelled us always to move around and between them, rather than to walk through the invisible bodies. In other words, although there was space between the tails and the saddles, and between the saddles and the bridles, we were perpetually inclined to move all the way around the front or the rear of the horses, as if they were actually physically present.

What we discovered whilst working with this collection was less about developing a vocabulary and more about observing how each piece seemed to require, even dictate, a different kind of haptic engagement. Our conversation brought into focus the different kinds of touching we were doing—tracing, pinching, stroking, manipulating, folding, tapping, grasping, shaking— and the different body parts enlisted to do it—fingertips, palms, whole hand, forearms, whole arms, whole body.

Fig. 2. Fayen d'Evie, Georgina Kleege and Devon Bella, 2016. The Gravity, The Levity: Georgina Kleege and Heidi Rabben discuss Jompet Kuswidananto's Third Realm, 2011. Video still. KADIST, San Francisco.

A video still frames two women, standing and gesturing behind a ghostly horse form suggested by suspended leather and horsehair elements: a bridle with blinders; reins that dangle so that the ends are just out of the frame; a saddle with two stirrups, and a tail, which also has its tip just outside of the frame. The two women are standing behind the horse, their bodies facing the camera. One of the women, has a hand in the air, as if stroking the horse's mane. Her other hand lower, palm perpendicular to the floor, as if stroking the horse's chest. The other woman, is leaning over, with one hand reaching down to signal a volume where one of the horse's legs would be, and the other hand holding a slim, white cane. The two women are dressed in black, but their hands are similar tones to the blush-toned leather, such that the hands become another fragmented part of the distributive sculptural body of the horse.

F d'E: Destabilizing Codes of Behaviour

Devon announced the one-day exhibition The Gravity, The Levity as a public event with limited places, requiring a RSVP, allowing her a measure of control over the intensity of handling. On the day, most of the attending crowd were curious artists, curators, art teachers, and art writers. Only a few visitors identified themselves as blind or partially blind. After welcoming remarks, Devon established ground rules for the event. Since none of the group would be wearing gloves, she requested that everyone wash and dry their hands before touching the artworks, to avoid bare hands transferring natural skin oils or dirt to the materials. She then invited me to present a performative lecture which I had developed in lieu of didactic instructions. I opened the lecture with an introduction to Robert Hooke, the seventeenth-century Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society, who bemoaned a terrible defect afflicting Natural Historians: contentment with lazy, superficial description. Hooke claimed that this habit of descriptive casualness has compromised not only the advancement of knowledge about natural objects and phenomena, but the descriptions of almost all things. He declared that the antidote for this terrible looseness was diligent attention, not only through ocular inspection, but also manual handling. Here the titular paired terms – the gravity, the levity – appeared amidst a taxonomy of other descriptive qualities proposed by Hooke, such as clamminess, slipperiness, coarseness, fineness, stiffness, pliableness, moistness, fluidity, brittleness, dullness, and sonorousness (36).

As the lecture progressed, I spoke of the nineteenth-century codes of decorum that sought to educate the working class in taste and aesthetics, and that rendered touch as transgressive ("the unsanitary, lascivious body"), while subjugating handicrafts as decoration for the home (d'Evie, The Gravity). I noted the alternative social codes of modern libraries, where handling is democratised. I spoke of artists who scrape, splinter, depress, bruise, pour, spit, wipe, pace, copy-paste, of how touch insinuates in the making of any artwork. I suggested that despite a militant disavowal of touch, handling persists even within the most guarded collections, through curators, preparators, conservators and surreptitious art fans, whose fingerprints are furtively wiped away before the gallery opens its doors. In the closing sequence, I proposed that with diligent attention perhaps we can begin to retrieve latent stories of touch, and that a haptic reading of artworks – including those not normally considered through touch – might offer new conversations on materiality and immateriality, the politics of space, gendered politics, race politics, migrant politics, social interrelationships, intimacy, reverence, or fear.

I then handed over to Georgina, who led the group on a touch tour from piece to piece, reciting haptic discoveries collated during our experimental sessions, and inviting the wider group to join her in touching the works. One participant, a blind fan of accessible art, followed Georgina's lead with enthusiasm, investigating her tactile methods and also improvising with other ways of handling. A smattering of other visitors touched the artworks hesitantly, momentarily, politely, and then stood back, content to watch and listen from the margins. Thus, as Georgina was living out her dream of performing as blind docent enlightening and inciting a mixed audience to touch, our experiment perversely devolved into spectatorship of the blind. A former student of Georgina's whispered to her, in the midst of the tour, "None of the sighted people are touching anything." As the dynamic persisted, he announced a similar sentiment to the crowd of onlookers. Though his analysis was not entirely accurate, the touching by ocularnormative visitors was so cursory and tentative as to be near imperceptible.

I had hoped that the triangulation of Devon's positioning of the event, my lecture, and Georgina's tour would incite the audience to take up a rare opportunity to lay their hands on significant contemporary works of art, and to speak of their tactile discoveries during a collective conversation that closed the event. Yet our methods to invite tactile exploration proved insufficient. The issue was not a lack of interest or curiosity, as evidenced by communications from attendees in the wake of the event, requesting to be invited to future events, or connecting our work to themes within their respective practices. Indeed, a writer who had participated subsequently published an essay detailing how our event had provoked reflection on contemporary haptics, while an attending curator invited me to extend this trajectory of work in Moscow (Haug). Instead, it seems that audiences have become so habituated to normative visual cultural paradigms that even when restrictions on touch are explicitly lifted, and guidance is provided on ways to touch, it is a struggle in a one-off event to persuade audiences to break the codes of ocularnormative civility. My conclusion was that there is a need for a more pervasive project of artistic and curatorial interventions, to agitate ingrained norms of sensory segregation, to incite oculardiverse incivility, and to negotiate non-normative codes of behaviour for specific tactile encounters.

In the months following our public event, I accelerated the development of critical positions and methodologies towards this more radical proposition. I worked with the concept of a haptic "be-holder", retrieving the etymological root of beholding, bihalden, a conjoining of bi, thoroughly, and halden, to hold, to keep, to guard, to preserve, to maintain, to take care. I proposed that the concept of accessibility be inverted, shifting away from a segregated, disability-focused model, to awaken or extend perceptual attentiveness and movement vocabularies of all haptic be-holders. Responding to the invitation from V.A.C. in Moscow, I developed a performative pedagogical score to expand sensory attentiveness and movement vocabularies, which was performed through tactile encounters with sculptural works from the State Museum of Vadim Sidur. William Forsythe's theory of choreographic objects implicates the perceptual reflections of Jacques Lusseyran and Bernard Morin, and I drew on close readings of the latter sources to reconceptualise a touch tour as an encounter between a haptic be-holder in motion and an artwork understood as a specific choreographic object. The touch tour may then be approached as a site for understanding embodied interactions at nested scales: with discrete artworks; micro and macro relationships between arrangements of artworks and bodies in motion; movement pathways within an exhibition site; and spatial, environmental, social, or temporal factors that alter the experience of the encounter. To test this idea, I instigated exhibitions with oculardiverse collaborators, co-creating mutating, vibrational, sculptural installations that dissipated conventional distinctions between artists and audiences. Following Lusseyran and Morin, I treated the exhibition site as a boundless topology, a landscape through which to move and instigate action.

Conclusions

Our initial motivation – heightening the discursive value of insights derived through touch tours for the blind – has not been tempered. However, our experiences working with the KADIST collection have nuanced our ambitions. Clearly, affirming a blind person as the tactile docent of an exhibition, while onlookers watch with their hands firmly in their pockets, risks enacting a freak show of otherness. It may also reinforce the stereotype that blind people are innately endowed with superhuman powers of tactile perception, even though a person who is blind may well be accustomed to visual culture norms that have indoctrinated audiences to refrain publicly from touch in galleries or museums of art. We have not been dissuaded from arguing for oculardiverse docents who have a habit of haptic engagement, and can communicate tactile methods and discoveries, and invite perceptual improvisation. The handling of artworks from the KADIST collection impressed upon us how each discrete work of art requires and invites a different method of engagement and exploration. However, we realised that more attention needs to be paid to the performative and participative tensions related to how an audience is inducted into novel codes of embodied encounter. Who should assume the responsibility for liberating or regulating expectations of behaviour? We would grapple with this question in the subsequent phase of the project, experimenting with audio description as a curatorial and ekphrastic medium. Treated as a performative proposition, audio description may be transfigured as a score to activate and navigate conversations, translations, and interactions between and among constellations of artworks and complex bodies-in-motion.

Works Cited

- Antonello, Pierpaolo. "'Out of Touch': F.T. Marinetti's Il Tattilismo and the Futurist Critique of Separation." Back to the Futurists: The Avant-Garde and Its Legacy, edited by Elza Adamowicz and Simona Storchi, Manchester U P, 2013, pp. 38–55.

- Cachia, Amanda. "Curating New Openings: Rethinking Diversity in the Gallery." Art Journal, vol. 76, no. 3-4, 30, Jan. 2018, pp. 48-50. Taylor & Francis, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2017.1418482

- Candlin, Fiona. Art, Museums and Touch. Manchester U P, 2010.

- ---. "Don't Touch, Hands Off!: Art, Blindness and the Conservation of Expertise." Body and Society, vol. 10, no. 1, 1 Mar. 2004, pp. 71-90. SAGE, https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X04041761

- ---. "Rehabilitating Authorised Touch or Why Museum Visitors Touch the Exhibits." The Senses and Society, vol. 12, no. 3, 17 Oct. 2017, pp. 251-266. Taylor & Francis, https://doi.org/10.1080/17458927.2017.1367485

- Capistran, Juan. From a Whisper to a Scream. 2005, KADIST, San Francisco.

- Classen, Constance. The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch. Studies in Sensory History. U of Illinois P, 2012.

- ---. The Museum of the Senses: Experiencing Art and Collections. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.

- d'Evie, Fayen. The Gravity, The Levity. KADIST, 16 Jan. 2016, San Francisco. Performative lecture.

- ---. "Orienting Through Blindness: Blundering, Be-Holding and Wayfinding as Artistic and Curatorial Methods." Performance Paradigm, vol. 13, 2017, pp. 42-65. www.performanceparadigm.net/index.php/journal/issue/view/22. Accessed 19 June 2018.

- d'Evie, Fayen, Ben Phillips, and Janaleen Wolfe. Not All Treasure is Silver and Gold, Mate. 6 March – 2 April 2015, Westspace, Melbourne.

- d'Evie, Fayen, Georgina Kleege and Devon Bella, 2016. The Gravity, The Levity: Georgina Kleege and Heidi Rabben discuss Jompet Kuswidananto's Third Realm, 2011. Video still. KADIST, San Francisco.

- Fisher, Jennifer. "Tactile Affects." Tessera, vol. 32, Summer 2002, pp. 17–28. tessera.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/tessera/article/view/25273/23467. Accessed 19 June 2018.

- Forsythe, William. "Choreographic Objects." William Forsythe and the Practice of Choreography, edited by Steven Spier, Routledge, 2011, pp. 90-92.

- Hooke, Robert. The Posthumous works of Robert Hooke, containing his Cutlerian lectures, and other discourses, read at the meetings of the illustrious Royal Society. Second ed., F. Class, 1971.

- Haug, Kate. "Touching to See: Haptic Description and Twenty-First Century Visuality". LXAQ, vol. 1, 10 Oct. 2016. sfaq.us/2016/10/touching-to-see-haptic-description-and-21st-century-visuality/. Accessed 19 June 2018.

- Jackson, Allyn. "The World of Blind Mathematicians." Notices of the American M Mathematical Society, vol. 49, no. 10, Nov. 2002, pp. 1246–1251. www.ams.org/notices/200210/comm-morin.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2018.

- Kleege, Georgina. More Than Meets The Eye: What Blindness Brings to Art. Oxford U P, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190604356.001.0001

- ---. "Some Touching Thoughts and Wishful Thinking." Disability Studies Quarterly. vol. 33, no. 3, 2013. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v33i3.3741

- ---. "Kadist Proposal Re Haptic Exhibiting and Tactile Dialogue." Received by Fayen d'Evie, 12 Sept. 2015.

- Kuswidananto, Jompet. Third Realm. 2011, KADIST, San Francisco.

- Lusseyran, Jacques. And There Was Light. Translated by Elizabeth R. Cameron, New World Library, 2014.

- Martinez, Daniel Joseph. A meditation on the possibility… of romantic love or where you goin' with that gun in your hand, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton discuss the relationship between expressionism and social reality in Hitler's painting, 2005, KADIST, San Francisco.

- Papalia, Carmen and Whitney Mashburn. "Let's Keep in Touch." 12 Nov. 2017, Queen's Museum, New York. Workshop.

- Svankmajer, Jan. Touching and Imagining: An Introduction to Tactile Art. I.B. Tauris, 2014.

- Tilley, Heather. "Introduction: The Victorian Tactile Imagination." 19: Interdisciplinary Studies of the Long Nineteenth Century, vol. 19, 21 Oct. 2014. Open Library of Humanities, https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.723

- Wong, Adrian. Untitled (Grate I/II: Shan Mei Playground/ Grand Fortune Mansion). 2012, KADIST, San Francisco.

Notes

- Here, "artistic curiosities" refers to crafted objects within the sixteenth- to eighteenth- century European wunderkammers or kunstkammers, some of which have been acquired for the collections of major museums of art. For scholarly discussions of the cultural history of touch, we recommend Fiona Candlin's Art, Museums and Touch and Constance Classen's The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch.

Return to Text - For more detailed information, consult Amanda Cachia's "Curating New Openings: Rethinking Diversity in the Gallery" and the webpage for Carmen Papalia and Whitney Mashburn's "Let's Keep in Touch" workshop: www.queensmuseum.org/events/lets-keep-in-touch.

Return to Text - Within this essay, we have chosen to experiment with conversation as a structure for the narrative, acknowledging moments of doubt, confusion, and collaborative discovery. Given the space constraints, we have privileged personal reflections and the evolution of our dialogue over analysis of secondary texts, though we have referenced a small sample of key texts that have informed our respective positions. For more extensive discussion locating our respective perspectives in the context of broader scholarly discourse, we refer readers to Georgina Kleege's More Than Meets The Eye: What Blindness Brings to Art and Fayen d'Evie's "Orienting Through Blindness: Blundering, Be-Holding and Wayfinding as Artistic and Curatorial Methods."

Return to Text - For a detailed account of my experience of museum touch tours consult Georgina Kleege's "Some Touching Thoughts and Wishful Thinking."

Return to Text - A similar but more detailed narration of the characteristics and failings of this installation is included in Fayen d'Evie's "Orienting Through Blindness: Blundering, Be-Holding and Wayfinding as Artistic and Curatorial Methods."

Return to Text - My approach to composition of the paintings was informed by readings on tactile, haptic and sensorial aesthetics including: Pierpaolo Antonello's "'Out of Touch': F.T. Marinetti's Il Tattilismo and the Futurist Critique of Separation"; Jan Svankmajer's Touching and Imagining: An Introduction to Tactile Art; Heather Tilley's "Introduction: The Victorian Tactile Imagination"; and Jennifer Fisher's "Tactile Affects."

Return to Text - For thoughtful discussion on the allure of forbidden touch: Fiona Candlin's, "Rehabilitating Authorised Touch or Why Museum Visitors Touch the Exhibits" and Constance Classen's The Museum of the Senses: Experiencing Art and Collections.

Return to Text