In advancing inclusion efforts this critical position paper makes explicit the relevance of new materialism as a pedagogy to counter the dominant medicalized models in Canadian and Australian school and community contexts. This paper argues the implementation of contemporary universal policies and programs do not adequately address the complex experiences of children and young people with disabilities. New materialism as a form of pedagogy, however, can prioritize individuals embodied, relational connections to all things and find new, creative ways to support young people with disabilities. The material turn is a welcoming pedagogical framework that places the material body and the emergent child at the center of educational and community practice.

Introduction:

As educators and critical disability scholars in Canada and Australia we are challenged with questions surrounding our own inclusive practices. In particular, we have been held in tension when delivering inclusion agendas as both countries predominantly continue to implement medicalized functional pedagogies that do not adequately attend to the embodied experiences of young people with disabilities (Allan, 2015; Lynch & Irvine, 2009; Slee, 2011; Underwood, 2008). Instead, the primary focus is on assessing their deficits to meet universalized standards. This inquiry aims to push forward the agenda for new, more embodied approaches to support young people with disabilities in Canadian and Australian community and school contexts. To ask: What might happen if we gave increased attention to the emergent body? How does it change how we look, what we ask, and what we choose to represent? Importantly, 'how do we destabilize dominant medical models that ground Canadian and Australian inclusive design?' and 'How do we stop ourselves from slipping back into conventional approaches when thinking about children and youth with disabilities?' In raising these questions, we turned to explore poststructural scholars interested in thinking about the intricate connections individuals make to all things beyond universalized programming and human-centered practices.

One specific area of emergence that drew our attention was to increasingly consider children and youth with disabilities' connections to all kinds of matter and how a person's connections to matter (i.e. objects, spaces, and other non-human things) can inform the multiplicity of their subjectivities. This material shift is known as the 'posthuman turn' or 'the material turn' and it emerged as a means to transgress beyond the universal subject (Coole & Frost, 2010). Rosi Braidotti explains the material turn or what she coined new materialism with Manuel DeLanda in the 1990s, as an "embodied and embedded brand of feminist philosophy" that "break[s] from both universalism and dualism" creating a "specific band of situated epistemology" (Braidotti in Dolphijn & van der Tuin, 2012, p. 22). In this paper, we are interested in how new materialism might be used when working with young people with disabilities, as it presents a productive space to prioritize the creative connections they make to all things and disrupt static medicalized notions on disability experience. "Matter teaches us through resisting dominant discourses, showing us new ways of being" (Hickey-Moody & Page, 2016, p. 5). Given the pre-vailing emphasis on special education models within government, educational and community policies and practices enacted across Canada and Australia, new materialism as a form of pedagogy can potentially disrupt these linear regimes (McBride, 2013; Slee, 2011; Underwood, 2008). That is, the 'new materialist' turn can put into question dualisms; human/non-human, culture/nature, structure/agency and extend understandings outside traditional forms of representation (Braidotti, 2006; Coole & Frost, 2010). Hultman and Lenz Taguchi (2010) similarly suggest new materialism opens up possibilities to understand the children as emergent in which non-human forces are equally at play and work as constitutive factors in their everyday lives. This emphasis on the relational dimensions of human-nonhuman encounters is what Barad (2007) describes as intra-action, the mutual engagement bodies make to all matter. That is, intra-activity formulates alternative insights; a "way of understanding the world from within and as a part of it" (Barad, 2003, p. 88).

Specifically, in this paper, by exploring new materialism as a form of pedagogy within the field of disability studies, we want to give increased attentiveness to young people's mediated actions. As Coole and Frost (2010) reiterate, "everywhere we look, it seems to us, we are witnessing scattered but insistent demands for more materialist modes of analysis" and to attend to a body's infinite possibilities (p. 2). To ask: Are there new ways to engage children and youth with disabilities in school and community beyond standardized special education models? Are there pedagogical approaches that allow for young people's increased voice, creativity and active engagement? Can we incite educators, practitioners, community organizations, government departments to increasingly consider more liberating pedagogical approaches when working with children and youth with disabilities?

Our rationale for examining new materialism as a form of pedagogy in Australian and Canadian contexts is based on our own situated knowledge within these countries as educators. This requirement to push the boundaries is further evidenced after reviewing current Canadian and Australian inclusive policies and programs that predominantly revert to a medical model framework. This medical model framework is often categorized through special education literature and programming, with a strong emphasis on remediating children and youth with disabilities' bodies closer to normality. For example, when analyzing provincially governed Canadian inclusive policies and documents, the majority of provinces implement a special education model (McBride, 2013). That is, "under these authorities, all jurisdictions in Canada either require or recommend that an individual program be designed and implemented for students identified as having special needs" (McBride, 2013, p. 5). The commonalities include an assessment and the identification of needs, development of an individual program plan with suitable accommodations and the assigning of educators to deliver a separate special education curriculum to the student with a disability. For instance, in the province of Alberta, the government's Standards for the Provision of Early Childhood Special Education (2006) identifies that "through early intervention strategies" young children can "develop knowledge, skills and attitudes that prepare them for later learning" (p.2). Similarly, Ontario's Standards for School Boards' Special Education Plans (2000) states schools "must have in place procedures to identify each child's level of development, learning abilities, and needs", and they must "ensure that educational programs are designed to accommodate these needs and to facilitate each child's growth and development" (p.6).Whilst these provincial policies are in place, what is not clear is the effectiveness of programs in fully supporting children and youth with disabilities inclusive experiences in Canadian learning settings (McBride, 2013). In particular, there is a paucity of research that explores the relevance of more embodied forms of programming that consider children's affinity to all things beyond universalized curriculum and human centered practice.

If we look briefly at an example from the Australian context, national Disability Standards of Education (2005) advocate "enrolment, educational treatment and participation on the same basis as a prospective student without a disability" (p.12, emphasis in original). However, within state jurisdictional levels, special educational policies emphasize adjustments and interventions to address predominant medicalized and deficit notions of disability for these young people to participate in mainstream education. In documenting Australia's first national curriculum, specifically in reference to meeting the needs of young people with disabilities, Price and Slee (2018) argue that students with disabilities continue to be commonly consigned to the special educational needs or special needs student categories. This has been reinforced by numerous reports including the Queensland report of education for students with disabilities in state schools, identifying how separate special education continues to be pervasive (Deloitte Access Economics, 2017). This is despite the national call for educational goals of equity, excellence and active and informed citizenship outlined in the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (MCEETYA, 2008). Vinson, Rawsthorne, Beavis, and Ericson (2015) describe the broader concerns in Australia for youth in their Dropping off the Edge Report, with increasing youth experiencing unemployment, criminal convictions and disengaged in their communities. Young people with disabilities are of no exception. They continue to describe a "[w]eb of disadvantage: constraining effect of one form of disadvantage which can reinforce the impact of one or more other forms of disadvantage" (Vinson et al., 2015, p. 10). Whilst Canadian and Australian governments have advocated for rights-based inclusive policies and practices, such as: equal educational access, full membership, and engagement in both academic and extra-curricular programming, the enactment of such policies continue to regulate how young people with disabilities experience their communities.

Critical disability scholars have problematized medical model frameworks and how they place too much emphasis on children and youth's functional aptitude with a lack of attendance to the wider dimensions of their lives (See Canella, 2005; Corker & Shakespeare, 2002; Goodley, 2014; Goodley, Hughes & Davis, 2012; Reddington & Price, 2016; Reddington, 2017; Reddington & Price, 2017; Scully, 2002; Slee, 2001; Underwood, 2008). As Corker and Shakespeare (2002) explain it is the strong emphasis placed on a child's functionality relative to their medical signifiers that "seek[s] to explain disability universally and end[s] up creating totalizing, meta-historical narratives that exclude important dimensions of individual lives, abilities and of their knowledge" (p. 15). As such, the categorical definitions of disability continue to be problematic producing an ability/disability system that marks difference and informs our ideas about disability and normality (Garland-Thomson, 2002). This is strongly evident after examining special education policies in Canada and Australia where the documents prioritize the remediation of bodily difference. This paper advances the argument to engage in alternative pedagogical approaches, namely the application of new materialism to unsettle essentialist medical model frameworks and acknowledge the situated capacities young people with disabilities embody with all things. Specifically, we argue the requirement to disrupt functional knowledges grounded in medical discourses and to push the boundaries. To do this, we suggest new materialism as a form of pedagogy as it values and recognizes the intersections young people with disabilities make to both human and nonhuman elements. It is important to acknowledge in advance that we are not discounting human to human interactions in this paper; instead we are accounting for the non-human connections that often do not get prioritized when working with young people. As Peters and Burbules (2004) remind us, historically in education there has been a tendency to think humanistically and focus on the relations between humans; however, children make connections to nonhuman things and these also require attention. We turn now to outline the broad field of new materialism followed with examples of new materialism mobilized with young people to capture new embodied knowledge on their lives.

New Materialism

Since educational and community settings have a "long history of representational logic," new materialism as a form of pedagogy can work to transgress these boundaries and focus on the relational dimensions of individual experience (Olsson, 2009, p. xvi). That is, to increasingly account for the nature between discursive practices and the materiality of the body (Barad, 2007). As Hickey-Moody and Page (2016) remind us, "bodies and things are not separate as we were once taught, and their interrelationship is vital to how we come to know ourselves as human and interact with our environments" (p. 2). We, therefore, invite a space for individuals to see how new materialism might be used as a form of pedagogy, as a form of praxis (Freire, 1996) to disrupt traditional ways of thinking about disability experience and to see the entanglement all bodies make to matter and how it informs one's subjectivity. This is highly relevant for scholars and individuals who work in Canadian and Australian contexts as the pedagogical model continues to be aligned with Pearsall's (1999) definition of pedagogy, "theory and instruction of teaching and learning" (p. 1051) rather than a pedagogy understood as "the experience of the corporeality of the body's time and space when it is in the midst of learning" (Ellsworth, 2005, p.4). Therefore, there is a requirement to find alternative forms of pedagogy that prioritize the multiplicity of connections young people with disabilities make to all things, human and non-human. As Hickey Moody, Palmer and Sayers (2016) similarly suggest "[m]atter teaches us [to resist] dominant discourses and [show] new ways of being" (p. 220). It is a "profound movement beyond a Cartesian mind-body dualism … shifts to a 'between' located in, with, and through the body" (Hickey Moody et al., 2016, p. 216, emphasis in original). That is, new materialism "conceive[s] of matter or the body as having a peculiar and distinctive kind of agency, one that is neither a direct nor an incidental outgrowth of human intentionality but rather one with its own impetus and trajectory" (Frost, 2011, p. 70). Further, Coole and Frost (2010) recognize how new materialism can shift human understanding beyond the universal subject and think through possibilities on young people's lives.

Such a shift in Canadian and Australian inclusive delivery produces an opportunity to change the way educators and practitioners think about subjectivity; "blurr[ing] categorical distinctions" between nature and culture, mind and matter (Braidotti, 2006, p. 200). This is seen in recent research where new materialism has been applied to examine the entanglement young people make to all things. We turn now to give you a few detailed examples of new materialism and its capacity to mobilize new knowledge on young people's lives. We will then shift to share our research in the field of new materialism when working with young people in Canada and Australia.

New Materialism in Education

In wanting to show the relevance of human to nonhuman connection we begin first with the work of Hultman and Lenz-Taguchi (2010) who utilized new materialism as a methodological tool to focus on the non-human forces that inform children's learning in a Sweden preschool. To do this, they set out to see and think differently about two photographic images taken in a Swedish preschool playground. The emphasis of their inquiry was to focus on the non-human intersections the children made to matter. At the onset, Hultman and Lenz Taguchi describe the tension they felt at first glances of the images as humanistic approaches to education dominated their initial ways of thinking. "The children seemed to have a magnetic power over our gazes; they stood out from the background and seemed to rise above the material environment" (p. 525). Hultman and Lenz-Taguchi then remarked on the dominance of embedded human centered approaches in social contexts and how it continued to blur their capacities and ways of seeing the child even though they were highly theoretically informed on new materialism and contemporary frameworks in early childhood settings. "As feminist researchers, our awareness of what can be understood as an anthropocentric gaze, a gaze that puts humans above other matter in reality, that is, a kind of human supremacy or humancentrism, became even more problematic to us" (2010, p. 526, emphasis in original). In wanting to disrupt anthropocentric thinking, Hultman and Lenz-Taguchi decided to mobilize what they called relational materialism to ignite attention to the human-nonhuman encounters the preschool children made to their environments; with a keen interest in exploring the mutual intersections they made to all matter. Relational materialism is understood as "a space in which non-human forces are equally at play and work as constitutive factors in children's learning and becomings" (Hultman & Lenz-Taguchi, 2010 p. 527).

For example, when exploring one image of a girl in sandbox, the initial anthropocentric gaze shows the girl and the sandbox as two separate entities. The sandbox merely a backdrop to the girl, a "subject/object" divide (Hultman & Lenz-Taguchi, 2010, p.527). Yet, when they put forth their new materialist approach and asked, "What happens if we look at the image thinking that not only humans can be thought upon as active and agentic, but also non-human and matter can be granted 'agency'?" they could actively destabilize the separation of girl and sandbox and see them as mutually engaged (p. 527, emphasis in original). Hultman and Lenz-Taguchi discovered that the sand offered new possibilities when viewed as an effect of mutual engagement. The relation between sand and the girl (metaphorically) can postulate questions to each other and locate an active, emergent relation with one another.

[T]he sand and the girl, as bodies and matter of forces of different intensities and speed, fold around each other and overlap, in the event of the sand falling, hand opening… the falling movement of the glittering sand into the red bucket. (Hultman & Lenz-Taguchi, 2010, p. 530)

Through a relational materialist approach, the sand is understood as emergent and actively interconnected with the girl just as much as the girl plays with the sand. "Human and non-human bodies can thus be thought upon as forces that overlap and relate to each other" (Hultman & Lenz-Taguchi, 2010, p. 529). Their body of work draws attention to the importance of tracking children's attraction to all things as many children and youth experiencing disability are affectively drawn to nonhuman forms of matter (Reddington & Price, 2016; Reddington & Price, 2017). We suggest Hultman and Lenz-Taguchi's relational materialism, including the use of images are a productive tool to show young people's intersubjectivity with matter in diverse settings, that everything is not human-to-human focused. Empowering young people with disabilities as visual ethnographers has been found to highlight their interrelatedness with space and place to enhance "opportunities for learning, interactions, safety and happiness" (Price, 2016, p.67). Leander and Boldt (2012) similarly have centered attention on children's emergent actions with other things when offering a nonrepresentational reading of two young boys' experiences with literacy. Their analysis of the boys' experiences with text focuses on the multiplicity of movement. Distinctly, they examine two boys' active intersections when reading and playing with Japanese manga.

At one point they [the two boys] carried their books, costume accessories, and weapons outdoors and sat reading in a porch swing. With no spoken planning, Lee stood up, grabbed a sword, and began swinging it at Hunter. Hunter dropped his book and picked up a sword, and for the next several minutes the battle moved between the porch and the front yard, with the porch steps offering a vantage point from which to make leaping lunges at one another" (Leander & Boldt, 2012, p.27).

Leander and Boldt's attentiveness to the boys' movements, "[lives] in the ongoing present" addresses how children can be thought of differently outside static forms of representation (p.22). Here, the concept of movement, the entanglement of play with Japanese manga, supports the process of thinking through bodily capacities where a more active, ontological space is prioritized.

Our goal with the nonrepresentational rereading is to reassert the sensations and movements of the body in the moment by moment unfolding or emergence of activity. This nonrepresentational approach describes literacy activity as not projected toward some textual end point, but as living its life in the ongoing present, forming relations and connections across signs, objects, and bodies in often unexpected ways. Such activity is saturated with affect and emotion; it creates and is fed by an ongoing series of affective intensities that are different from the rational control of meanings and forms (Leander & Boldt, 2012, p.25, 26).

Leander and Boldt argue that if we begin with the body rather than with texts our attention turns elsewhere. This work is useful in demonstrating the relevance of new materialism as a form of pedagogy as it makes a shift to think about young people with disabilities' competencies outside functional medicalized models. This notion of following young learners'emergent relations to texts through movement and physical engagement with learning materials and seeing what matters to children is further evidenced in O'Donnell's work.

O'Donnell (2013) identified how problematic it has been for children and youth when educators, practitioners, government services predominantly focus on "performance indicators for behaviour change" and use a "skills-based" approach to measure and assess social competence (p.265). O'Donnell's (2013) argument to value and recognize children's subtle pedagogical relations in school, whereby "some of the most significant moments in education can arise from chance occurrences" warrants greater attention in Canadian and Australian contexts (p. 266).

[The] simple act of noticing and seeing a sense of possibility in those unpredictable moments (kairos) that arise in classrooms, such as a gleam of insight or a frown crossing a student's face, better positions the teacher to help students to work through a genuine pedagogical encounter with a subject (O'Donnell, 2013, p.267 emphasis in original).

O'Donnell (2013) attendance to children's potential shows us that we do not know what children and youth will form connections to; and therefore, we must remain open to the situational elements within pedagogical encounters. In Canadian and Australian contexts, a transformative recognition of children and youth's actions could signal a reworking of the special education model that currently places limits on how they are known. In desiring to transform recognition of children and youth's capacities, we turn now to explore our research in the field of new materialism. Our large aim in sharing our research is to ignite a discussion amongst scholars, educators, practitioners, government organizations, and in communities on ways to increasingly apply new materialism as a form of pedagogy to support young people. We have purposefully chosen research that focuses on young people's diverse connections to different things, namely: spaces, objects, virtual realities as well as the arts to show the relevance of matter in their lives. We also include a series of reflective questions across the section, to support increased dialogue about how new materialism as a form of pedagogy might be facilitated in multiple environments to support inclusion.

Conceptualizing New Materialism

We start by showing how connections to virtual realities can posit a welcoming space for young people with disabilities to thrive and rearticulate their social relations. Below we share an excerpt of our research on one young man with autism spectrum (AS) and his relations to virtual worlds. In this body of research, Donna Haraway's (1991) readings of cyborg configurations are applied to explore up close his affective connections to cyborg imagery. In particular, we analyzed how this young 21-year-old man with AS mobilized cyborg imagery to "rearticulate his social identity when experiencing school on the periphery" having previously attended public in Nova Scotia, Canada (Reddington & Price, 2016, p. 882). Specifically, the young man, Arthur, created a partial cyborg identity, named Silver Ninja Viper, as a mechanism to renegotiate his subjectivity in school. As a cyborg figure Arthur could perform "like a ninja" and act like a bit of a "tough guy" (p. 889, emphasis added).

Digital robotic voiceover software gives Arthur a space to assign lived qualities to his cyborg ninja, heightening his appeal to exist as partial cyborg. Arthur's cyborg writing similarly amplifies his capacity to exist in alternative ways which he activates across an 18 module [comic] series on ninja's life. Arthur working as partial cyborg, rewrite[s] his social trajectory via ninja [and] offers that social space to evade static configurations that previously deemed his body as marginalized, peripheral. (p. 889)

We later highlight in this research how Arthur's Silver Ninja Viper transformed into a blue Dodge Viper GTS. "Arthur's cyborg performs like a Transformer, with ninja moving at high speeds, battling forces both with real world (Earth) and fictional worlds" … "thus, Silver Ninja Viper acting as lead, masculine hero provided Arthur with the opportunity to revitalize his social world" (p. 889, 890). Through Arthur's material relation to cyborg imagery, he was able to rearticulate his social identity more to his liking and in the process, disrupt his marginalized status. He later revealed to Reddington (2014) how he produced an 18 comic module series on his life as Silver Ninja Viper as it served as a mechanism to rupture what he called his former, "wuss status"; his body no longer bound as a medicalized subject. We cannot discount the connections people with disabilities make to technology as a means to transgress their marginalized social experiences. To ask: how might access to creative virtual mediums increase young people with disabilities affective connections to others, to their surroundings? How might technology be utilized to support them in maintaining social connections when outside of learning spaces, to their peers?

We turn now to show another example of our research that involved young people with disabilities' connections to spaces who had previously attended public school in Nova Scotia. We chose this body of research to show the relevance of space in their lives and how space is not a static entity (Reddington & Price, 2017). By means of face to face semi-structured interviews, Reddington (2014) sought responses from young men with AS,18-34 years, about their situated experiences in educational spaces. The participants in the study self-identified as young men with autism who had experienced school under the Nova Scotia Special Education Policy (SEPM) (Nova Scotia Department of Education and Culture, SEPM, 1996). At the time of the interviews, the participants described how they occupied various school sites, such as regular classroom settings, resource rooms, and separate learning center environments. The learning center and resource rooms in Nova Scotia schools are remedial settings under the special education policy designed to assist children and youth with disabilities when receiving separate individual programming. In wanting to access the young men's relational experiences with school spaces, Reddington (2014) used visual mapping to account for their emergent experiences in school spaces. Explicitly, the concept of visually mapping involved inviting participants to emergently draw their uses of spaces on 8cm x 11cm paper with the use of colored markers. Many of the young men responded to this activity and were eager to show "on paper" their relational kinship to school sites.

In wanting to follow the young men's emergent connections to school spaces, Reddington (2014) employed the works of Deleuze and Guattari (1987) in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (ATP) as it offers some productive conceptual tools to foster a new materialist pedagogical framework. The concept of rhizomes pursues a line of thought that looks to extend and prioritize attendance to children and youth's infinite potential. Deleuze and Guattari (1987) describe rhizomes as a type of plant spreading in multiple directions with no centralized root. "The rhizome operates by variation, expansion, conquest, capture, offshoots … the rhizome is acentered, non-hierarchical, nonsignifying system without a General and without and organizing memory or central automation" (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 21). Here, we suggest rhizomes mobilized as a conceptual tool support a new materialist pedagogical approach as it allows for recognition of thinking through emergent relations, "any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be … this is very different from the tree or root, which plots a point, fixes an order (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987, p. 7).

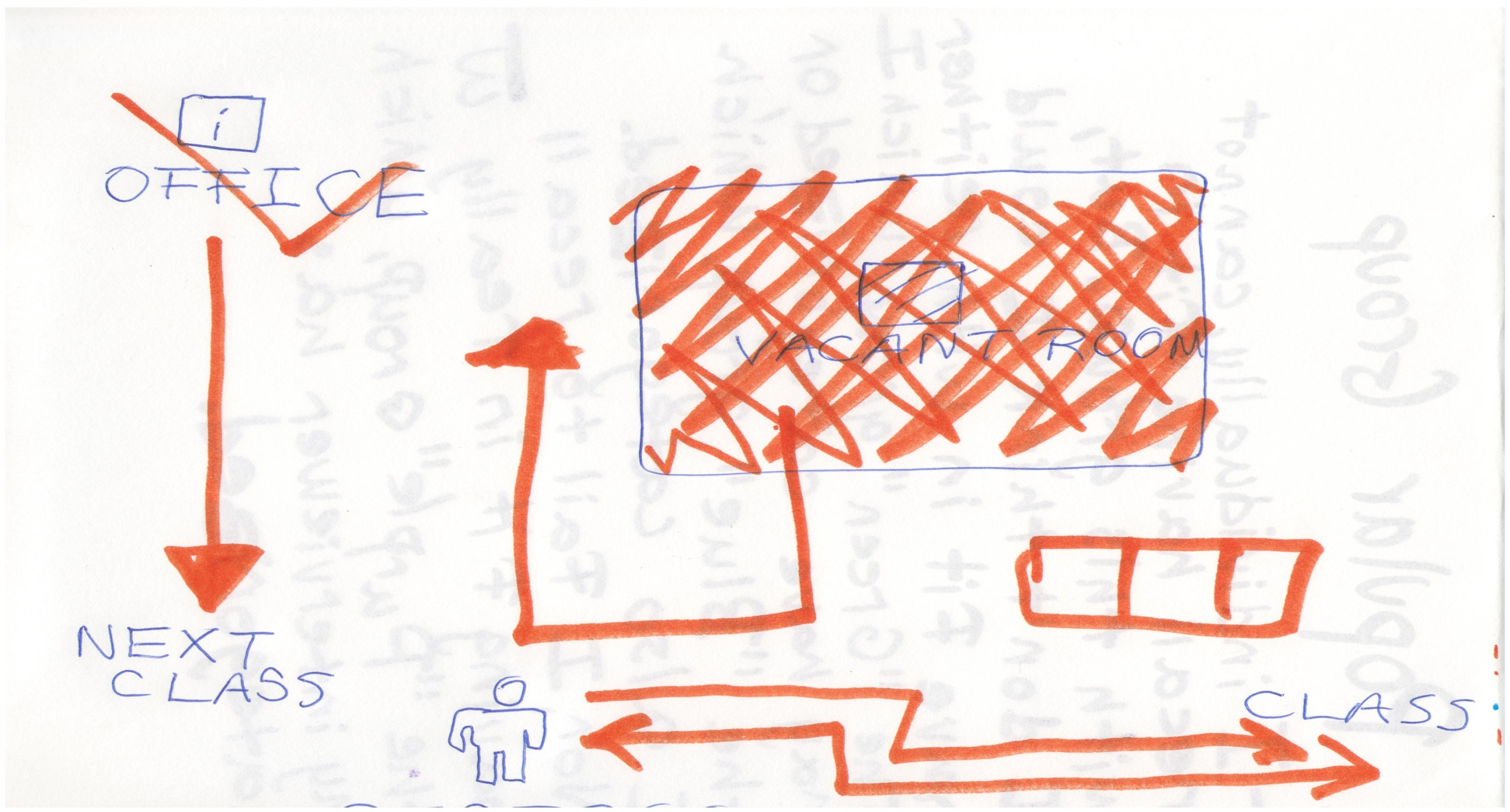

For example, one twenty-two-year-old man with AS indicated how he used to do laps of the hallways to escape what he called the confines of the learning center (See Reddington & Price, 2017). His capacity to use movement (doing laps of the hallway) to disrupt his static medicalized position indicates the potential he possessed to find new trajectories. It is through the act of visually mapping his use of school spaces that we produced new embodied knowledge on his school experiences. Another participant in Reddington's study drew a map of a vacant classroom and showed how he secured this space during noon time to avoid unwelcoming entanglements with dominant peers (See Figure 1.0). The young man's active movement to occupy the vacant room reveals his capacity to resist conventional forms of movement and "attempt to imagine outside them" (Youdell, 2011, p. 27). Here, we show the relevance of visually mapping young people's movements to demonstrate how bodies flow through different spaces in meaningful ways and how physical sites are not passive entities.

Figure 1.0: Arthur's Vacant Room (Figure 1.0 shows a pen sketch of a rectangle labelled, "vacant room" and outside the vacant room in the top left-hand corner is the word, "office" and below "office" the word "next class". Arthur after labelling these spaces with a pen took an orange marker and drew thick orange arrows showing his direct route of travel where he left the vacant room, walked past the office and headed directly down a long hallway to his next class.)

This new materialist work evidences the relevance of inquiring more about children and youth's active engagements and movements in diverse spaces. We suggest mapping activities can be a productive way to understand the multiplicity of their subjectivities in different spaces and can take a multiplicity of forms such as: physically drawing their journey on paper, photographing use of spaces, or alternatively walking the site with children and actively video recording their engagements. Other elements might involve mapping their movements relative to peers. To consider: Where do they like to go? What is at stake for children with disabilities when moving across various spaces – at home, in community, at school, in public venues? Such a focus on their movements can ignite a mediated space to learn more about what informs their subjectivities and understandings of our complex world. We invite educators, practitioners, families and community facilitators to find opportunities to support young people's affective desires and facilitate more welcoming spaces for young people to experience.

This is seen in Price's (2016) recent work where she mobilized digital photography to gain alternative knowledge on thirty-seven students with disabilities aged 13-19 years and their experiences of educational places and spaces. In responding to the question "What is important to me?" student images depicted interactions with significant people (i.e. peers and staff) moving across multiple contexts both within the special education site and local community. Space and places which provided safe opportunities to interact, demonstrate capabilities and foster learning and independence were deemed most important. For example, community access programs mobilized interactions and connections to space and place through work experience, cycling program, community café hospitality training and independent living skills activities. Significantly for those young people involved in the school community café (See Figure 2.0), they built trusting relationships with peers, staff and community whilst acquiring skills in hospitality to mobilize as they transition from school to society. Price (2016) creatively shows the importance of matter in the young lives and how such affinities to non-human things and activities can transform their personal relationships in meaningful ways.

Figure 2.0: School Community Cafe (Figure 2.0 shows an image of small cups of Jell-O and fruit on a tray and youth moving around the table picking up the food and talking to others.)

When looking further at new materialist approaches, we also see the importance of acknowledging young people's personal relationships to objects, fictional characters, stuffed animals, pets, and other aesthetics as seen in Reddington's (2014) research. To ask: Is there a certain object the child is drawn to? Do youth with disabilities have an affinity for fictional mediums? To animals? Below is an example of the relevance of objects in young people's lives, particularly those experiencing disability. Reddington (2014) explicitly reveals the relevance of using artefacts in her research when exploring young men with autism spectrum, ages 18-34, situated experiences having previously attended public school in Nova Scotia, Canada. As part of her methodology, she invited participants to share artefacts from their schooling (e.g. photographs, yearbooks, pictures, drawings and keepsakes).

One participant, a twenty-two-year-old man, Oliver, who self-identified as having autism, showed Reddington the affective connection he made to strong mythological characters seen in films and books. Oliver explained how his interest in mythology grew after spending long hours at school in a learning center environment. He further added how he felt separated from his peers when occupying the learning center stating, "I don't know I mean everybody else goes to the class, and I was mostly in the learning center around other people with autism who were often loud or made a lot of noise" (Reddington & Price, 2017, p.1202). Oliver then stated how he enjoyed looking up mythological characters on the Internet as it gave him a chance to "get away" from others or what he indicated as the "kids that annoyed him." He expressed what he liked best about mythology was that many of the characters represented what he called, "formidable power, strength and bravery." He was drawn to some characters more than others, specifically "The Titans" and "Hercules". He then reached for his backpack during the interview and asked if he could show Reddington something. Oliver soon revealed a series of mythological characters he sketched during his time in the learning center. After filtering through several pieces, he gave Reddington this drawing titled, 'Me in School' for her project (See Figure 3.0).

Figure 3.0: Me in School (Figure 3.0 is a pencil sketch of a masculine character with broad shoulders and muscular arms. The pencil-colored sketched fictional character is wearing a white vest, lime green t-shirt and gray and blue colored pants. The hands drawn are large and oversized and signal strength and vitality. The sketch resembles a superhero type figure.)

Oliver identified how he wanted to emulate this mythological character, stating, he was "tough and unbeatable." Here, we see the strong connection another makes to art to escape reality and find other means to express his subjectivity. The image of The Titans or Hercules produced a welcoming affective connection for Oliver that he could use to transgress his static remedial experiences in the learning center and locate experiences more to his liking. What unfolds through inviting the young men to bring in artefacts, like Oliver's art, is an alternative understanding of how young people with disabilities think about their subjectivity. It is through using artefacts that these new insights were offered. This is evidenced again when a twenty-one-year old participant with autism, Wes, expressed how art was a large part of his identity and asked at the onset if he could show Reddington a piece of his art.

He uploaded onto Reddington's computer an image of a ceramic bowl. The bowl was a project Wes had constructed in school, and designed to be a "representation of his identity." Together, glancing at the image Wes explained its characteristics and imparted that the lid signified his "introverted" nature, and then signaled for Reddington to look at the sharp points protruding from the sides of the bowl. He explained that the points were added to reinforce the idea of "keeping people at a distance." Wes' bowl also had two sculpted handles intended to look like bones to embrace his feelings of "touching bone," "organic" and "intimate." The bowl, a symbol of Wes' identity, presented an initial means for Wes to share his identity through his interplay with art and matter.

By allowing children and youth to share artefacts, to visually map their use of school spaces and emergently draw their affective bond to non-human things can assist practitioners, educators, specialists, community facilitators in knowing more about what is important in children and youth's everyday lives. In other words, by attending to the wider dimensions of their lives, by applying new materialist approaches, we can learn beyond functional, medicalized paradigms. To ask: Do young people actively work to maintain certain relations to things? Within the field of disability, how might thinking about young people's emergent relatedness to all things expand our knowing about what is important to them? This follows Deleuze and Guattari (1987) where bodies are thought about through movement, vitality and possibilities. The exploration in this section is intended to support individuals working with young people in being responsive in nurturing all their connections, both human and non-human. It is through a new materialist pedagogical approach that we can begin to decenter medicalized framework models and advance towards a space where alterity and variation is prioritized.

Conclusion

A new materialist pedagogical approach can pursue the transient nature of children and youth's lives. That is, new materialism as a form of pedagogy can signal a reworking of conventional pedagogies within disability models that place limits on how children and youth are known. Distinctly, it invites individuals working with young people to increasingly consider what other possibilities might exist when attention is given to their lives in moments. This is crucial as young people who feel disempowered and marginalized can become oppressed (Freire, 1996). Rodgers (2006) describes Himley and Carini's importance placed on a description discipline of carefully attending to young people, "not to fix or explain [a] child, but to make the child more visible by coming to understand him or her more fully and complexly as a particular thinker and learner" (Himley & Carini, p. 127). This is to "to be more sensitively attuned to who [children] are and are becoming, so that recognizing them as persons, we can assist and support their learning better" (Himley & Carini, 2000, p.57). Therefore, the material turn is a welcoming pedagogical framework that places the material body, the emergent learner, as the central focus.

We must therefore seek opportunities for more liberating pedagogies within the disability field, to present new ways of engaging young people and resisting dominant functional models bound by curricula. Such an approach offers affordances for young people with disabilities to increase access to learning, open new pathways to employment, community engagement and contributing to society as productive and respected citizens. As Cannella (2005) reminds us, "the possibilities for supporting diverse knowledges, facilitating new actions and practices, and fostering various ways of living/being with and learning from each other are limitless" (p.19). In addition, there is a requirement to follow closely the entanglements children and youth make with both human and nonhuman things and acknowledge the multiplicities of subjectivities of young people. A space where identity is not fixed, but rather fluid and where we as a community create conditions that empower young people to authentically participate.

References

- Alberta Minister of Education. (2006). Standards for the provision of early childhood special education. Retrieved from https://education.alberta.ca/media/1626521/ecs_specialedstds2006.pdf

- Allan, J. (2015). Critiquing policy: Limitations and possibilities. In D. Connor, J. Valle & C. Hale (Eds.), Practicing disability studies in education: Acting towards social change. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28 (3), 801–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822388128

- Braidotti, R. (2006). Posthuman, all too human towards a new process ontology. Theory, Culture & Society, 23(7-8), 197-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276406069232

- Cannella, G. (2005). Reconceptualizing the field (of early care and education): If 'Western' child development is a problem, then what do we do? In. N. Yelland (Ed.), Critical issues in early childhood education (pp. 17-39). New York, NY: Open University Press.

- Coole, D. & Frost, S. (Eds.). (2010). New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics. Durham, NC: Duke University. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822392996

- Corker, M., & Shakespeare, T. (Eds.). (2002). Disability/postmodernity: Embodying disability theory. London, UK: Continuum.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota Press.

- Deloitte Access Economics (2017) Review of education for students with disability in Queensland State Schools. Brisbane, Department of Education and Training. http://education.qld.gov.au/schools/disability/docs/executive-summary-disability-review-report.pdf

- Dolphijn, R. & van der Tuin, I. (2012). New materialism: Interviews & cartographies. Michigan, MI: Open Humanities Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/ohp.11515701.0001.001

- Ellsworth, E. (2005). Places of learning: Media, architecture, pedagogy. New York: Routledge.

- Frost, S. (2011). The implications of the new materialism for feminist epistemology. In H. Grasswick (Ed.), Feminist epistemology and philosophy of science (pp. 69-83). New York, NY: Springer Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6835-5_4

- Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2002). Integrating disability, transforming feminist theory. NWSA Journal, 14(3), 1-32. https://doi.org/10.2979/NWS.2002.14.3.1

- Goodley, D. (2014). Dis /ability Studies: Theorising disablism and ableism. London, UK: Routledge.

- Goodley, D., Hughes, B. & Davis, L. (Eds.) (2012). Disability and social theory. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137023001

- Haraway, D. (1991). A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology and socialist-feminism in the twentieth century. London, UK: Routledge.

- Hickey-Moody, A., & Page, T. (Eds.) (2016). Arts, pedagogy and cultural resistance: New materialisms. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hickey-Moody, A., Palmer, H., & Sayers, E. (2016). Diffractive pedagogies: Dancing across new materialist imaginaries. Gender and Education, 28(2), 213-229. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1140723

- Himley, M., & Carini, P. (Eds.). (2000). From another angle: Children's strengths and school standards. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Hultman, K., & Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Challenging anthropocentric analysis of visual data: A relational materialist methodological approach to educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(5), 525-542. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2010.500628

- Leander, K.M., & Boldt, G. (2012). Rereading "a pedagogy of multiliteracies": Bodies, texts, and emergence. Journal of Literacy Research, 45(1), 22– 46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X12468587

- Lynch, S. L., & Irvine, A.N. (2009). "Inclusive education and best practice for children with autism spectrum disorder: An Integrated Approach." International Journal of Inclusive Education 13, 845–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802475518

- McBride, J. (2013). Special education legislation and policy in Canada. Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 14(1), 4-8.

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA). (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. Melbourne: MCEETYA. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

- National Disability Standards of Education. (2005). Retrieved from: https://www.education.gov.au/disability-standards-education-2005

- Nova Scotia Department of Education and Culture. (1996). Nova Scotia Special Education Policy Manual. Halifax, NS: Author.

- O'Donnell, A. (2013). Unpredictability, transformation, and the pedagogical encounter: Reflections on "what is effective" in education. Educational Theory, 63(3), 265-282. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12023

- Olsson, L. M. (2009). Movement and experimentation in young children's learning: Deleuze and Guattari in early childhood education. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ontario Ministry of Education. (2000). Ontario's standards for school boards' special education plans. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/speced/iepstand/iepstand.pdf

- Pearsall. J. (Eds). (1999). The concise Oxford dictionary. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Peters, M.A., & Burbules, N. (2004). Poststructuralism and educational research. Lanham & Oxford, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Price, D. (2016). Wellbeing in disability education (Chapter 3). In F. McCallum, & D. Price, (Eds.), Nurturing wellbeing development in education: From little things big things grow. (pp. 112-132). London, UK: Routledge.

- Price, D., & Slee, R. (2018 in press). An Australian curriculum that includes diverse learners: the case of students with disability. In A. Reid & D. Price (Eds.), (Chapter 17). The Australian curriculum: Promises, problems and possibilities. Australian Curriculum Studies Association, Canberra.

- Reddington, S. (2014). "Thinking through multiplicities: Movement, affect and the schooling experiences of young men with autism spectrum disorder." Unpublished PhD thesis, University of South Australia, Adelaide.

- Reddington, S. & Price, D. (2017). Trajectories of smooth: Mapping two young men with autism spectrum experiences in Canadian school spaces. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(12), 1197-1209. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1336576

- Reddington, S. (2017). A pedagogy of movement and affect: Young men with ASD and intersubjective possibilities. In C. Loeser & B. Pini (Eds.), Disability and Masculinity: Corporeality, Pedagogy and the Critique of Alterity (pp. 45-63). London, UK: Palgrave MacMillan Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-53477-4_2

- Reddington, S. & Price, D. (2016). Cyborg and autism: Exploring new social articulations via posthuman connections. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(7), 882-892. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1174898

- Rodgers, C.R. (2006). Attending to student voice: The impact of descriptive feedback on learning and teaching. Curriculum Inquiry, 36(2), 209-237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2006.00353.x

- Scully, J. L. (2002). A postmodern disorder: Moral encounters with molecular models of disability'. In M. Corker, & T. Shakespeare (Eds.), Disability/Postmodernity: Embodying disability theory (pp. 48-59). London, UK: Continuum.

- Slee, R. (2011). The irregular school: exclusion, schooling and inclusive education, London, UK: Taylor and Francis.

- Slee, R. (2001). Driven to the margins: Disabled students, inclusive schooling and the politics of possibility. Cambridge Journal of Education, 31(3), 385-397. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640120086620

- Underwood, K. (2008). The construction of disability in our schools: Teacher and parent perspectives on the experience of labelled students. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Vinson, T. Rawsthorne, M., Beavis, A., & Ericson, M. (2015). Dropping off the edge, 2015: Persistent communal disadvantage. Victoria & ACT: Jesuit Social Services/Catholic Social Services Australia.

- Youdell, D. (2011). School trouble: Identity, power and politics in education. London, UK: Routledge.