The Small Island State of Jamaica is vulnerable to various natural hazards; as a result, it faces threats to its economy, infrastructure, property, and populace. Disaster Risk Management (DRM), including preparedness, mitigation, and recovery, is critical for the nation. Central to this process is information provision and dissemination in order to enhance the public's understanding and management of these hazards.

Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) are a significant part of Jamaica's population, who require DRM information in special formats. This exploratory study examines the provisions made for PWDs in DRM at the national and local government levels in Jamaica. Surveys were utilised to gather information from national Government Ministries and local Parish Councils about DRM facilities in place for PWDs, access to DRM information for PWDs, and the extent of PWDs participation in DRM at these levels. Additionally, focus group consultations were held with PWDs from two educational institutions for PWDs to gather their perspectives on provision of information and special facilities for them.

Jamaica has taken the appropriate policy and legal steps to recognise the rights of PWDs by being a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, as well as developing a national policy and enacting legislation on PWDs. Additionally, government respondents showed a high level of awareness of the necessity of disability inclusion. The results, however, indicate that disability inclusiveness has not been achieved by many government entities charged with responsibility for policy implementation and with the responsibility of setting the example by obeying the country's laws. Recommendations are made to ensure full participation of PWDs in society including equal access to information, equal access to facilities and inclusion in DRM programming and planning.

Introduction

The Caribbean region is comprised of three main island groupings, the Greater Antilles, the Lesser Antilles, and the islands of the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos archipelagos, as well as Belize on the Central American rim and the Guianas on the north-eastern coast of South America (Potter, Barker, Conway & Klak, 2004). Many countries and territories of the region lie within the North Atlantic hurricane belt and many are located within active seismic and volcanic zones (Carby, 2011).

Jamaica, 18N 77W, located in the northern Caribbean, is exposed to multiple hazards of natural and anthropogenic origin. These include hurricanes, floods, droughts, earthquakes, landslides, transportation accidents, and hazardous materials releases. It is estimated that exposure of the country's assets to seismic and hurricane hazards stands at US$ 18.6 billion (Inter American Development Bank [IADB], 2009), and the entire population is vulnerable to the impact of these hazards, though at differing levels. The 2011 Census carried out by the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN), indicated the number of Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) in Jamaica. As can be seen from Table 1, the population 5 years old and over possessing specific disabilities includes 129,645 males and 238,565 females (a total of 368,210) with some sort of sight disability; 31,374 males and 43,483 females (a total of 74,857) with some sort of hearing disability; 46,413 males and 79,474 females (a total of 125,887) with some sort of walking disability; and 18,742 males and 19,697 females (a total of 38,439) with some sort of communication disability.

| DISABILITY | MALE | FEMALE | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sight | 129,645 | 238,565 | 368,210 |

| Hearing | 31,374 | 43,483 | 74,857 |

| Walking | 46,413 | 79,474 | 125,887 |

| Communicating | 18,742 | 19,697 | 38,439 |

Note. Results include persons who indicated having some difficulty, much difficulty or not being able to do specific function at all as indicated by the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (2011).

As outlined in Table 2, in terms of the population 15 years old and over possessing specific disabilities, 36,643 males and 58,115 females (a total of 94,758) possess a disability associated with lifting; 18,594 males and 24,751 females (a total of 43,345) have a disability associated with self-care; and 27,933 males and 44,693 females (a total of 72,626) have a disability associated with remembering and concentrating.

| DISABILITY | MALE | FEMALE | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifting | 36,643 | 58,115 | 94,758 |

| Self-care | 18,594 | 24,751 | 43,345 |

| Remembering & Concentrating | 27,933 | 44,693 | 72,626 |

Note. Results include persons who indicated having some difficulty, much difficulty or not being able to do specific function at all as indicated by the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (2011).

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPWDs) and its optional Protocols were adopted in 2006 and entered into force in 2008. Full and effective inclusion and participation in society, accessibility and equality of opportunity are among the guiding principles of the Convention, which to date has been ratified by some 160 signatories, including Jamaica.

As societal attitudes to PWDs have evolved, so has the discourse surrounding PWDs and DRM. Persons with Disabilities can suffer even more adverse effects from natural hazards as evidenced in the cases of the 2004 Asian tsunami, Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (Hemingway & Priestly, 2006) and Hurricane Ivan in 2004 (Jagger, 2011). Despite the existence of the UNCRPWDs, PWDs are often not adequately catered for in DRM information dissemination and planning. Wisner (2002) describes PWDs as a once forgotten group in DRM. As recognition of the rights of PWDs has increased, so has the recognition of the importance of planning for PWDs in crises and emergencies. Historically in DRM planning, persons with impairments have been considered to suffer from disabilities which make them vulnerable in disaster situations and are often cast as victims in need of special assistance (Wisner, 2002). Emergency Management organisations often include guidance for providing this special assistance. For example, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) of the United States (US) had guidance for Planning for Personal Assistance Services in General Population Shelters (Wisner, 2002). This approach however is shifting.

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 presents a different viewpoint, stating that PWDs are important in the assessment, design and implementation of plans tailored to their specific requirements. This is consistent with the UN Convention's concept of "full and effective inclusion and participation" and suggests that DRM policy should explicitly provide for active involvement of PWDs in all aspects of DRM, and that practitioners should ensure that such policy is implemented by inclusion of PWDs in DRM planning and programming.

Observation in Jamaica suggests that the existence of policy and legal frameworks has not resulted in adequate inclusion of PWDs in society, including in the public sector. The purpose of this study was therefore to explore the facilities available for PWDs, provisions made for PWDs in DRM in national Ministries and local Parish Councils in Jamaica, as well as the extent to which provision is made for PWDs to contribute to DRM planning in these organisations. Specifically, the research sought to address the following questions:

- What types of facilities are in place for Persons with Disabilities with regard to preparedness for and response to hazards?

- What types of access do Persons with Disabilities have to Disaster Risk Management information?

- To what extent are efforts made to include Persons with Disabilities in Disaster Risk Management planning?

Methodology

The study utilised elements of both quantitative and qualitative approaches to gather data. The quantitative aspect involved the development and administration of a survey instrument to all Government Ministries (n=12) and Parish Councils (n=13) within Jamaica; thus the entire population of Ministries and Parish Councils was the focus of the study. The survey instrument was developed by the researchers and was based in part on another survey instrument (also designed by the researchers), which was utilised in a study carried out amongst PWD umbrella organisations in the region to explore access to DRM information and assistance. Some questions were modifications of this earlier instrument whilst other questions were new in order to focus on this specific topic. Thus, question wording was improved where needed based on experiences with the previous instrument. The survey instrument sought to gather various data in four main sections:

- Section One - general background information on the entities, including their involvement in DRM national and regional networks, their awareness of DRM policies, plans, and legislation, and whether PWDs are employed at their organisations;

- Section Two - the DRM facilities in place for PWDs within the entities and whether organisational emergency plans make provision for PWDs;

- Section Three - access to DRM information for PWDs, types of programmes for PWDs, and the groups targeted by these programmes; and

- Section Four - the extent to which PWDs are included in DRM planning.

All respondents were assured of anonymity with respect to the reporting of results.

Instruments were emailed to the Parish Disaster Coordinators of the Parish Councils and to various sections of the Ministries as recommended during telephone calls. Follow-up telephone calls were made to increase respondent response. At the national level, 50% of the Government Ministries contacted (six Ministries) responded to the survey whilst 92% of the Parish Councils contacted (12 of 13 Councils) responded to the survey. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was utilised to analyse data, with descriptive statistics generated.

The qualitative aspect of the research involved two focus group consultations undertaken with PWDs from two educational institutions for PWDs in Jamaica. Letters were sent to the Principals of the institutions seeking entry and access to undertake the research with students. One focus group involved approximately 30 past and present students of an institution for those with hearing impairments and included an interpreter. The other focus group was carried out at a school that focused on special education and involved 12 current students with various physical and developmental impairments. All students were below the age of 18; in both cases, gatekeepers, including some parents and teachers, were present. These gatekeepers ranged in age from the mid-30s to the 40s. These two student groups were chosen based on convenience sampling as they were the only coherent groups of PWDs that could have been accessed to explore those receiving (accessing) DRM information. Whilst it might be assumed that teenagers and young adults may not normally be representative of DRM awareness and preparedness behaviours, some studies have suggested that age is not a significant determinant of disaster preparedness behaviours (e.g., Najafi et al. 2015). Additionally, in Jamaica, the Parish Disaster Committee had been undertaking sensitisation work with this stakeholder group. The presence of gatekeepers allowed for the addition of their perspectives to the discussions.

Semi-structured questions were asked to uncover individuals' thoughts with respect to access to DRM information and provision of assistance during times of emergencies. Discussions were tape-recorded and transcribed. As with the surveys, participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality with respect to the reporting of the results. The trustworthiness of this aspect of the study was enhanced primarily through triangulation, specifically having two members of the research team facilitate the focus group discussions and analyse the results, as well as through ethical conduct of this aspect of the research.

It should be noted that this aspect of the study was limited to a focus on exploring access to DRM information and did not include whether recipients acted on this information.

Findings

Awareness of and Involvement in Disaster Risk Management

The national and local government entities were asked various questions related to their awareness of and involvement in DRM. Amongst the Government Ministries, two (40%) reported that they belonged to regional and/or national disaster management networks, citing regional entities such as the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) and local entities such as the National Disaster Coordinating Network and National Disaster Risk Management Council. All of the Parish Councils which responded indicated that they belonged to regional and/or national disaster management networks with ten of them indicating that they belonged to the Office of Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Management (ODPEM) and two indicating that they were part of the National Disaster Committee.

With respect to DRM plans, of the total respondents at both the national and local government levels, 89% reported having DRM plans in place, with 5.6% indicating that no plan was in place and 5.6% of respondents indicating that they were unsure whether a plan was in place. Significantly, all twelve of the Parish Councils reported having a plan in place whilst only 67% of the Government Ministries reported having a plan in place.

Ninety-four percent of the entities at the national and local government levels indicated that a Disaster Management Planning Committee was in existence. This includes five of the Government Ministries, whose Committees were comprised of Senior Management, Middle Management, Ancillary Staff, and Other Members. Similarly, amongst the Parish Councils which indicated that they had Planning Committees, membership was also comprised of Senior and Middle Management, along with other Committee members.

Provision for Persons with Disabilities in Disaster Risk Management

The various local and government entities were asked whether the existing DRM plans within their entities made specific provisions for PWDs and whether any sorts of facilities were in place for PWDs. Although 89% of respondents had reported having DRM plans in place, only 53% of these indicated that these plans make provisions for PWDs. Twenty-four percent indicated that no provision for PWDs was made in these plans and 12% reported being unsure as to whether provision was made. Significantly, 64% of the Parish Councils reported that the plans make provisions for PWDs, whilst 33% of the Government Ministries indicated that the DRM plans in existence in their entities make provisions for PWDs.

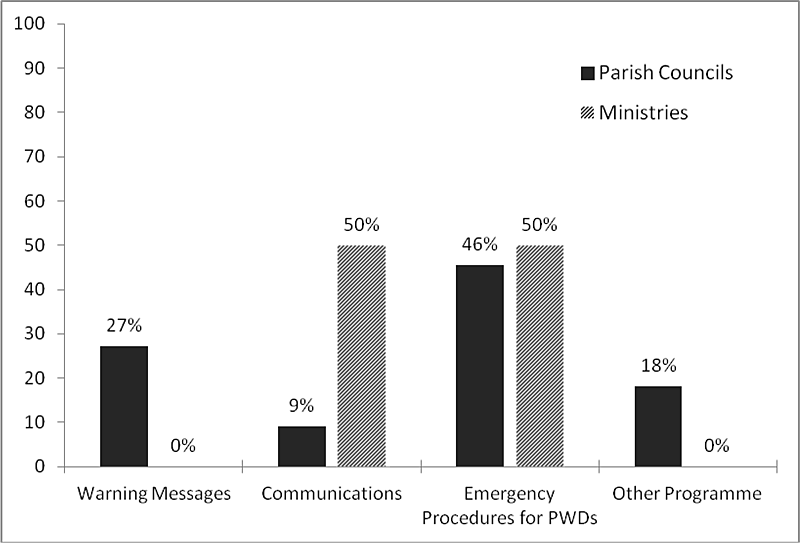

Additionally, only 39% of all respondents at the national and local government levels reported that their entities carried out any sort of DRM programmes specifically for PWDs. For Parish Councils, 50% reported that they carry out DRM programmes for PWDs whilst 17% of the Government Ministries carry out programmes in DRM for PWDs. Within the Ministries, the programmes included Communications (that is, communicating information about potential hazards, impacts and risks before events) and Emergency Procedures for PWDs (actions to be take in response to a threat or an emergency/disaster), and these programmes were targeted at the visually impaired, hearing impaired, mobility impaired, and the colour blind. Twenty-seven percent of Parish Councils stated that their programmes included Warning Messages (that is, messages given to alert the recipient to the threat immediately prior to an event), 9% indicated that their programmes included Communications, 46% that their programmes included Emergency Procedures for PWDs which were focused on the visually, hearing, mobility, and mentally impaired, and 18% had other programmes (see Figure 1 below). Amongst the Ministries, none had programmes for Warning Messages, 50% had programmes which included Communications, 50% had programmes for Emergency Procedures for PWDs, and none had any other programmes (see Figure 1 below).

Access to Disaster Risk Management Information

As indicated, all respondents were asked to indicate whether special programmes were undertaken for PWDs, the types of programmes carried out and the specific target groups. They were also asked about provision for and communication to PWDs during times of emergency. For communicating warnings to PWDs, the respondents reported communicating warnings through disability organisations, Community Emergency Response Teams (CERTs), specially designated persons, fire wardens and fire monitors, and special warning systems such as strobe lights. One respondent reported that there is no special system in place for warnings.

At the local government level, 75% of the Parish Councils indicated that assistance is provided to PWDs in times of emergency, which includes, battening down of homes, stocking of emergency supplies, transportation for evacuation, emergency plan development, special access to emergency relief, and provision of funding/assistance for recovery. For the Government Ministries, 60% stated that in times of emergency there is provision of assistance to PWDs. The Ministries cited amongst the type of assistance transportation for evacuation, emergency plan development, special access to emergency relief, and provision of funding/assistance for recovery.

Inclusion in Disaster Risk Management Planning and Preparedness

All entities were asked whether there were any PWDs employed in their organisation. For the national government entities, three of the six (50%) indicated that they had PWDs amongst their employees, whilst two (17%) of the twelve Parish Councils indicated that they had PWDs amongst their employment. Two Ministries indicated that they have facilities in place for PWDs, including, special bathrooms, special elevators, and ramps. At the local government level, five of the Parish Councils (42%) stated that they have facilities for PWDs, including ramps, special bathrooms, and other facilities.

Importantly as well, all of the Government Ministries who responded indicated that they were aware of the Persons with Disabilities Act, whilst eleven (92%) of the Parish Councils who responded stated that they knew of the Act.

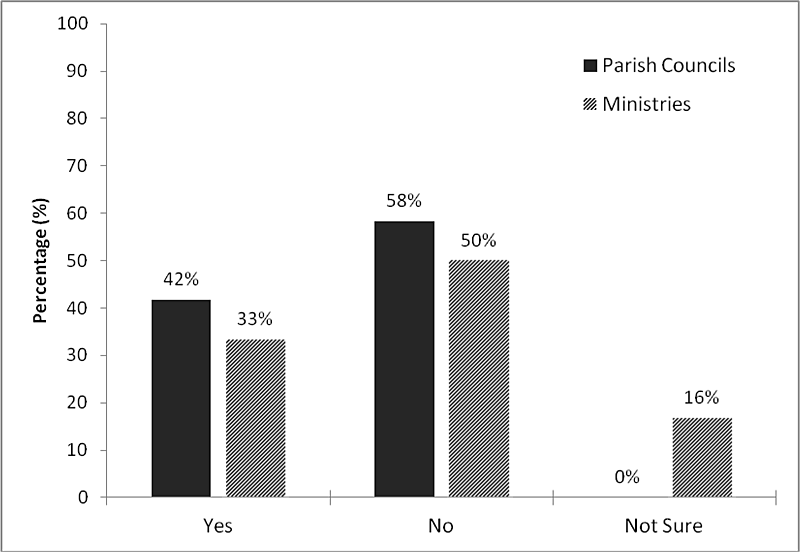

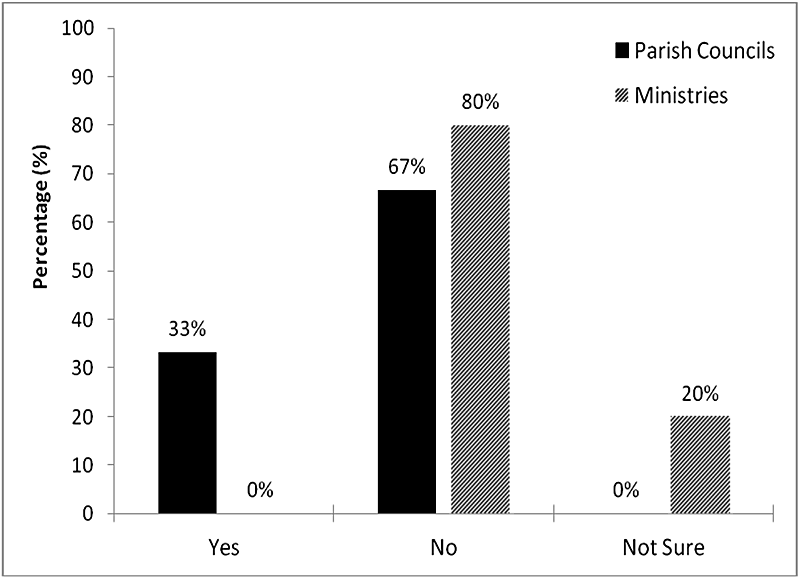

National and local government entities were asked about the inclusion of PWDs on DRM Planning Committees, about special roles accorded PWDs during times of emergency, and to offer recommendations with respect to facilitating PWDs in the workplace. With respect to the inclusion of PWDs in DRM Planning and Preparedness, none of the Government Ministries reported that PWDs are included on DRM Planning Committees, rather, 80% indicated that no PWDs were included on DRM Planning Committees and 20% indicated that they were not sure. Four of the Ministries also indicated that PWDs were not given any special roles during times of emergencies. Amongst the Parish Councils, however, 33% indicated that PWDs are included on Planning Committees whilst 67% indicated that they were not (Figure 2). Nine of the Councils, though, stated that PWDs were not accorded any special roles during emergencies whilst three said that they were uncertain if any special roles were allocated to PWDs during these times.

Figure 2. Inclusion of persons with disabilities on Disaster Management planning committees in national and local government entities.

Significantly, all of the Ministries and Parish Councils who responded to the survey felt that more should be done to facilitate PWDs in the workplace during both normal times and times of emergency.

Discussion

PWDs and DRM in Jamaica

Jamaica developed the country's National Policy for Persons with Disabilities (NPOPWDS) in 1999. The policy states that the policy development process was initiated through self-advocacy and involved several umbrella organisations representing persons with impairments. These organisations emerged in the early 1980s and resulted in PWDs becoming more vocal and advocating for their rights. One of the major goals of the policy is to "integrate persons with disabilities into society so that they can participate fully in all aspects of society" (National Advisory Council on Disability, 1999). The policy affirms the right of all persons to information and calls for the widespread use of "alternate means of communication" (National Advisory Council on Disability, 1999).

With reference to disaster preparedness, the policy states that the government and the private sector should ensure that the special needs of PWDs are taken into account in a disaster. It also emphasises the importance of ensuring communication with PWDs and their inclusion in DRM. Interestingly, in the policy's Preamble, the view is expressed that there is a need for legislation which would help to remove some of the societal barriers and contribute to a shift to a new norm, that of inclusion rather than marginalisation. It was not until 15 years later that The Disabilities Act 2014 was passed. It legally establishes the Jamaica Council for Persons with Disabilities and a Disabilities Rights Tribunal, provides for equal access to all aspects of national life, protection from discrimination and access to education and training for PWDs. In addition, it calls for public passenger vehicles and public and commercial premises to be readily accessible to PWDs. The Act does not speak specifically to DRM and PWDs.

The Disabilities Act 2014 defines "persons with disabilities" as person(s) with a "long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment which may hinder his full and effective participation in society, on an equal basis with other persons" (The Disabilities Act, 2014, p. 4). However, some authors, (e.g. Wisner, 2002; Hemingway & Priestley, 2006) subscribing to the social model of disability, state that an impairment becomes a disability because of societal factors. Hemingway and Priestley (2006) argue that disability is no longer perceived as a natural consequence of impairment.

DRM theory also recognises vulnerability as constructed by society. The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) defines vulnerability as, "The conditions determined by physical, social, economic, and environmental factors or processes, which increase the susceptibility of a community to the impact of hazards" (UNISDR, 2004). Thus, different members of a society may be exposed to the same hazard but may experience different vulnerability depending on socio-economic circumstances, access to power, gender, age and other factors. Cutter, Boruff and Shirley (2003) describe vulnerability as being based on inequalities which shape the susceptibility of groups or individuals and their ability to respond. Cutter et al. (2003) also recognise vulnerability of place – characteristics of the built environment, growth rates and other factors which can contribute to social vulnerability (Cutter et al., 2003).

In DRM, PWDs are often cast as being vulnerable by virtue of their impairment. Historically, this has led to the treatment of PWDs as victims in need of assistance (Wisner, 2002). However, Hemingway and Priestley (2006) argue that PWDs vulnerability to human disasters is embedded within social structures, institutional discrimination and the presence of environmental barriers. The Disabilities Act 2014 states among its principal objectives to "promote individual dignity and individual autonomy, including the freedom of choice and independence of a person with a disability" and to "ensure full and effective participation in society of persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others [emphasis added]" (The Disabilities Act, 2014, p. 5). If persons with impairments are to be independent and are to participate fully and effectively on an equal basis with others then it is clear that discrimination, environmental and institutional barriers must be removed in order that the impairment is not 'disabling'.

Facilities for PWDs in Normal Times

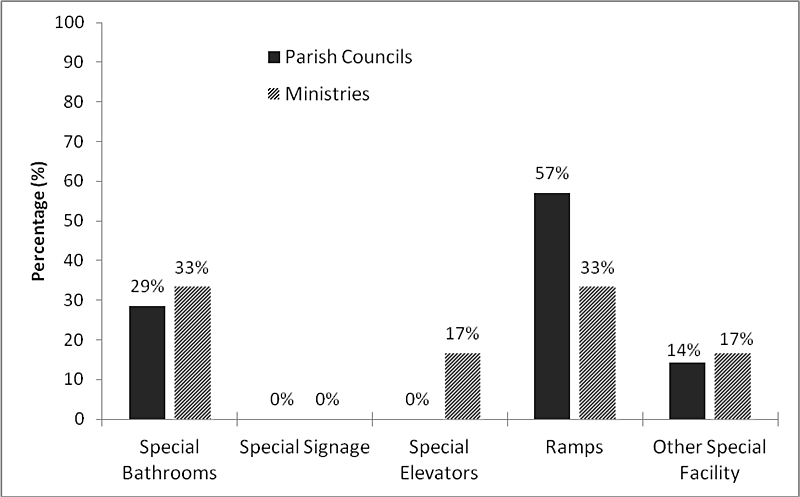

In Jamaica, PWDs face barriers outside of crises and emergencies. From Figure 3 it is notable that only 33% of responding Ministries and 42% of Parish Councils reported having special facilities for PWDs in the workplace. Fifty-eight percent of Parish Councils and 50% of Ministries reported that there were no special facilities for PWDs in the workplace. Sixteen percent of the Ministries who responded said that they were not sure if there were special facilities for PWDs in the workplace. Of those, 29% of Parish Councils and 33% of Ministries had specially equipped sanitary facilities; 57% of Parish Councils and 33% of Ministries had ramps; none of the Parish Councils and 17% of the Ministries reported elevators in buildings with more than one level; and 14% of Parish Councils and 17% of Ministries had other special facilities (see Figure 4). None of the Parish Councils nor Ministries had any special signage for PWDs.

During the focus group discussions with the hearing impaired, some of the everyday barriers faced were related. These include lack of sign language interpreters at hospitals, government offices, police stations and private sector entities such as banks. Members of the group stated that they sometimes try to write their questions but persons are often impatient, do not want to read these questions, and are unwilling to write answers to queries and other information. In an emergency there is no method of communicating with the emergency services using telephones. Some persons had downloaded an application from the Ministry of National Security which uses Global Positioning System (GPS) and allows the emergency services to locate the person who is texting. While not developed for PWDs, it is useful to them. However, most of the hearing-impaired persons attending the focus groups were not aware of the application.

Problems for PWDs encountering environmental and other barriers become more acute during crisis situations when the threat includes injury and possible death. Chou et al. (2004) in studying the effects of the 1999 Taiwan earthquake report that factors which increased the risk of death included moderate physical disability, psychiatric illness and socio-economic status.

Access to Information

In the context of DRM, barriers would include, for example, denial of access to information by not providing sign language interpretation, no text accompanying visual displays and use of colour coding only, as opposed to hatching, for warning signs. Thus, persons with impairments often cannot benefit from information which could prove vital to their safety.

Njelesani, Cleaver, Tataryn and Nixon (2012) report that evacuation plans for Hurricane Katrina, were geared towards persons who could walk, drive, see or hear. Some PWDs were evacuated without medicines, medical equipment, wheelchairs or service animals. Communication of warnings and precautionary information did not reach some persons with hearing impairments because of a lack of sign language. In addition, persons who were visually impaired could not understand the significance of some visual displays because there were no audio descriptions.

Difficulty in accessing information was also reported by the focus group of the hearing impaired. Precautionary and warning information broadcast by commercial media in many instances does not cater to PWDs. One participant stated that on the approach of Hurricane Matthew in 2016, she watched television, could see the track of the hurricane and see it getting closer and closer, but there was no text explaining the figures and maps that she was seeing. There was little sign language interpretation on national television channels. Some persons related that they found sign language interpretation for warnings on Facebook and followed updates there. Others watched foreign cable channels which provided sign language interpretation.

When the focus group of the hearing impaired were asked about precautionary information for other hazards, it was stated that the Parish Disaster Coordinator had done an earthquake drill at the school so students and staff knew what to do in an earthquake. However, no one had received information on earthquake mitigation measures such as better building practices or preventing non-structural damage in the home.

During the Chikungunya (ChikV) outbreak of 2015, many of the persons attending the focus group discussions became aware of the situation only when they saw persons becoming ill or when they became ill themselves. Some homes were visited by health personnel but they were unable to communicate with the hearing-impaired as the health personnel could not sign; however, they showed pictures of mosquitoes and the name of the disease. When asked if they were aware of the current (2016) Zika threat, most persons were not. One person had the impression that Zika develops from ChikV. Most of the women were unaware of the government message advising women to avoid getting pregnant.

Students at the other educational institution for PWDs (the special education school) were accompanied by teachers and caregivers. The latter group indicated that most persons, including PWDs, would find weather information given in latitude and longitude difficult to understand. In general, caregivers took the responsibility for ensuring that precautionary and alerting information is understood.

Interestingly, students who had not been participating in the conversation responded when asked about earthquake precautions. Many were able to state or demonstrate the actions to be taken during an earthquake, as the Parish Disaster Coordinator had conducted a drill at the school. This might suggest that demonstration of precautionary measures may be a good method for providing information for this group.

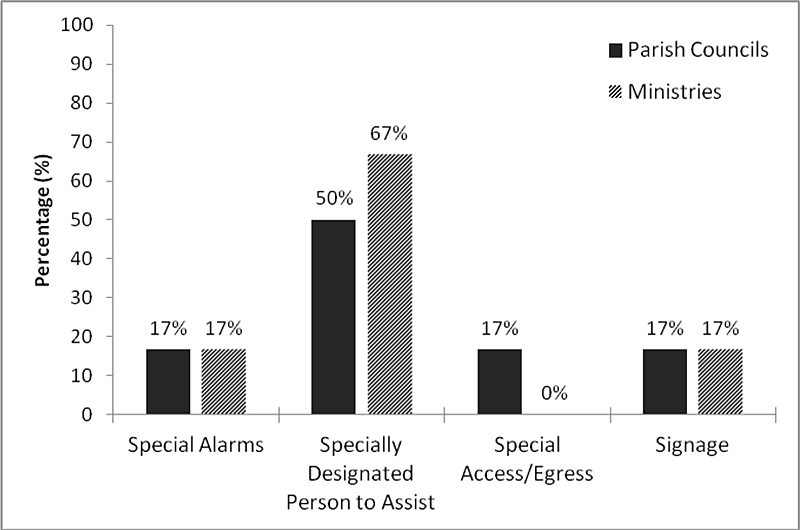

Although PWD-accessible warning messages and precautionary information are sparse on commercial media, the results suggest that the importance of alerting PWDs to potential emergency or disaster situations is appreciated by respondents. Seventeen percent of Parish Councils and 17% of Ministries indicated having Special Alarms in place for PWDs; 50% of Parish Councils and 67% of Ministries reported having specially designated persons to assist PWDs; 17% of Parish Councils indicated special access/egress for PWDs but no Ministries had this in place; and 17% of Parish Councils and 17% of Ministries had special signage in place for PWDs during emergencies (see Figure 5). Parish Councils and Ministries reported warning systems or procedures for PWDs. Systems in place at the parish level include designated members of CERTs being given responsibility for warning PWDs, strobe lights in offices and one Parish Disaster Committee reported using an umbrella organisation for PWDs to assist with alerting and warning. Ministries reported that fire wardens and monitors have been assigned responsibility for warning PWDs. However, these measures are not widespread enough to benefit the majority of PWDs.

Special Programmes for PWDs

Interestingly, almost 71% of the entities reported the existence of special provisions for PWDs during disasters and emergencies. Respondents reported that assistance during emergencies was in place for the visually impaired, the colour blind, the hearing impaired as well as those persons with developmental and mental challenges.

The types of assistance available for PWDs included battening down and securing of homes, stocking of emergency supplies, transportation for evacuation, special access to emergency relief and designated persons to assist PWDs. In the post-impact period, Parish Councils reported provision of funding and/or assistance for recovery. Pre-impact assistance such as battening and securing premises and stocking of emergency supplies are important. Jagger (2011) from her study in Jamaica, reported that PWDs did not want to go to shelters, but preferred to stay at home and get help with battening down, debris removal and clean-up. Persons with disabilities also indicated that access to home and community after the storm was a higher priority than access to a shelter (Jagger, 2011). This may reflect the condition of the shelters – not being PWD equipped – but it may also reflect that PWDs feel they will receive less support away from their residences. Some members of the focus groups indicated that they received help from family and other community members during and after disasters. This level of support might not be available at an emergency shelter. For the focus group at the special education institution, all the PWDs present required caregivers. Shelter facilities would be required to have enough space for PWDs, caregivers and equipment.

Inclusion in DRM Planning

Implications for Citizenship

Marshall (1950, quoted in Morris, 2005) identifies three types of citizenship rights: civil rights - necessary for individual freedom; political rights – the right to participate in the political process; and social rights – the right to economic welfare, security, sharing of the social heritage and to live life to the prevailing standards of the society. Civil and political rights are usually enshrined in law. Social rights are more problematic and include three concepts which are important in considering the exercise of citizenship by PWDs: self-determination, meaning that individuals have capacity for free choice and the exercise of autonomy; participation, which speaks to the full participation in political and social life; and contribution, that is, the recognition that PWDs do contribute to society (Morris, 2005). MacGregor (2012) argues that the true test of citizenship is whether it can be exercised. In Jamaica, as it pertains to DRM, individuals exercise free choice in the manner of response to warning messages and precautionary information. For example, there is no provision in law for mandatory evacuation; all citizens have the right to remain in their homes if they choose to, when warnings and evacuation notices are given. Morris (2005) argues, however, that giving people choice is not enough to enable self-determination for PWDs. If, for example, PWDs remain at home because of lack of facilities at emergency shelters, there is, in effect, no choice. Morris (2005) notes that in order for PWDs to be full citizens it may be necessary to remove barriers to self-determination or to provide resources to enable self-determination. To truly benefit from self-determination, emergency facilities should be so equipped that PWDs are at no disadvantage compared to those without impairments.

The study shows that PWDs are not afforded the opportunity for full participation in DRM activities. Despite making special provisions for PWDs in emergencies and disasters, PWDs are generally excluded from participating on an equal basis with other persons in DRM planning in the responding organisations. Only 33% of Parish Councils and none of the Ministries include PWDs in DRM planning committees and none of the respondents reported assigning roles to PWDs in emergencies and disasters.

There are various barriers to participation, some of which are attitudinal. The fact that many plans cater for assistance for PWDs show that these individuals are seen as in need of help. Other barriers relate to the conduct of meetings which cater for those without impairments. For meetings, there is no sign language for the hearing impaired, no sight-saving print for those with limited vision and as the survey showed, many public facilities do not provide ramps and elevators for the mobility impaired. As Anastasiou and Kauffman (2013) point out it is social structures which prevent PWDs from enjoying full participation in societal activities, further pointing out that the needs of PWDs should be fully taken into account and catered for in its social organisation. For DRM, participation is vital as disasters represent a threat to life.

The casting of PWDs as 'vulnerable' and as victims in need of assistance is not unusual. Wisner (2002) notes that many of the resources available on PWDs and disasters assume that the PWD is dependent, and notes that many plans do not assume that a PWD could be in a position to provide support and assistance to another person. The UNCRPWDs states that PWDs and PWD organisations should be involved in DRM planning and should be consulted by the State. Berke, Cooper, Salvesen, Spurlock and Rausch (2011) state the importance of public officials, local people and independent mediating organisations working together in overcoming barriers to resilience building.

DRM community-based planning recognises the importance of including residents of at-risk communities in developing plans for those communities. Involvement of community organisations in DRM in Jamaica dates back to the 1980s (Carby, 2015). Local knowledge is now used in Community Based Disaster Risk Management (CBDRM) programmes and contributes to hazard analyses for development planning (Carby, 2015). The same principle should apply to PWDs by including their knowledge in developing disability-inclusive plans and programmes. Despite this recognition of the importance of involving community-based organisations and local knowledge in DRM planning and programming, this has not extended to disabled peoples' organisations. Morris (2005) states that these organisations tend to be invisible. However, they can contribute by providing practical knowledge on the requirements for inclusivity, acting as points for information dissemination for PWDs and providing information to authorities on the status and needs of their members. Persons with disabilities can participate by assisting as volunteers providing services as do the able-bodied. For example, someone who is mobility-impaired could register persons at a shelter.

Recent experiences in disaster situations suggest that PWDs and organisations for PWDs can be a source of information and support. Hemingway and Priestley (2006) note that examples from Hurricane Katrina and the Indian Ocean Tsunami indicate that disabled people's organisations and informal networks represent great capacity to respond in post disaster situations; however, they lack resources to sustain their contributions and their expertise is underutilised in the disaster relief efforts.

The study suggests that PWD organisations are also underutilised in the planning phase of DRM in Jamaica. However, there are some examples of collaboration with organisations for PWDs. The NGO PANOS in partnership with the ODPEM and the Portmore Disability Association is piloting a warning system for PWDs in the city of Portmore. The system uses special receivers to provide alert messages to PWDs on the FM Band. Under that project one emergency shelter in Portmore was retrofitted to be PWD accessible (H. Glaze, personal communication, January 16, 2017). The ODPEM has also piloted other projects with the Combined Disabilities Association aimed at providing PWDs with training in disaster preparedness and DRM planning. These efforts can be seen as pilots which need to be replicated island-wide in order to be widely inclusive for PWDs.

There is some indication that efforts are being made by the government entities to ensure equal access for PWDs. The Ministry of Health reported a programme underway which is designed to ensure that PWDs have full access to health facilities and healthcare at all times. The programme includes training of staff in sign language, auditing of facilities for accessibility, retrofit of facilities, sensitisation of staff to rights of PWDs and training of health care providers in interacting with PWDs and meeting their needs. One Parish Council also reported that plans are being made to better meet the requirements of PWDs, including during emergencies and disasters.

The National Meteorological Service is developing an application for mobile devices which will deliver simplified colour-coded alerting information for weather systems (E. Thompson, personal communication, February 23, 2017). Though not PWD specific, this would be useful for those with some types of mental impairment.

The survey shows that respondents are aware of the Act and its requirements and listed several improvements which they think should be made for inclusion of PWDs. These included provision of adequate facilities, inclusion of PWDs in DRM planning and decision-making, assigning PWDs roles and responsibilities during response and recovery operations, sensitisation of the public, development of a database of PWDs, appropriate warning and alerting mechanisms and review of all government policies to ensure that these include considerations for PWDs. The importance of liaising with organisations for PWDs was also stated. An enabling policy and legal framework and a high level of awareness of the need for disability inclusion exist. It is difficult therefore to explain the lack of adequate facilities and the exclusion of PWDs from the DRM planning process.

When asked why appropriate mechanisms and systems for PWDs are not in place, respondents gave a variety of reasons, including inadequate financial resources for retrofitting facilities to make them PWD accessible. One respondent, in answering the survey, stated that societal attitudes exist which "place able-bodied persons at the top and PWDs at the bottom of a perceived hierarchy" (2016). It was suggested that sensitisation of the society is needed to change attitudes to PWDs and that training of staff in government offices is also required. One person suggested that public sector organisations should be required to report annually on progress on complying with the Disabilities Act.

This latter is a very interesting suggestion. Kieck et al. (2016) suggest a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system for inclusive development cooperation, which includes disability-sensitive indicators. They suggest the use of non-person related indicators to measure aspects such as laws and policies which promote disability inclusion, equitable policy-making processes and accessibility of training courses for PWDs. Such an M&E system could be adapted for use by national and local government authorities as part of their monitoring and reporting under Jamaica's sustainable development plan Vision 2030 Jamaica.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Jamaica has taken the appropriate legal and policy steps to recognise the rights of PWDs by being a signatory to the UN Convention, developing policy and enacting legislation on PWDs. However, this has not led to widespread improvement in the situation of PWDs, particularly in the area of DRM. There is need for concerted action at the meso (regional), macro (national) and micro (local) levels (Berke et al., 2011).

The intent of both the 1999 Policy for PWDs and the Disabilities Act 2014 is clear: PWDs have equal rights in Jamaica and must be afforded the opportunity and means to participate fully in all aspects of life. Though not treating DRM in detail, the provisions made in the policy and legislation, if implemented, would ensure that impairments do not in fact become disabling in emergencies and disasters. Despite the absence of specific reference to DRM in the Policy and Act, application of these instruments to DRM is not difficult. Tables 3 and 4 show the requirements of the policy and Act and recommend how they can be applied to DRM.

| Requirement under Policy | Application to DRM |

|---|---|

| A national communication system which takes into account the right to information of all citizens. | All DRM information to be accessible to PWDs. Priority to be given to alerting and warning systems and messages and precautionary information. National DRM communication system should be equipped with technology which enables communication with PWDs. |

| A barrier-free environment that will enable PWDs to have physical and technological access to all areas of society. | Emergency shelters to be equipped to facilitate PWDs including designated areas for PWDs. |

| Organisations of and for PWDs should collaborate with the relevant agencies to provide the necessary information regarding the clientele they serve. | PWD representatives to be included on National DRM Council, Committees, Parish Disaster Committees and on CBDRM Teams, and to be assigned roles in plans. |

Note. Requirements under National Policy for Persons with Disabilities from National Advisory Council on Disability (1999)

| Requirement under Act | Application to DRM |

|---|---|

| A person with a disability has the same fundamental rights as any other person in Jamaica. | This must include the right to alerts and warnings, precautionary information, information on available facilities, and assistance in a format which can be easily accessed and understood. |

| Promote individual dignity and individual autonomy. | Adequate facilities in emergency transportation and accommodation to allow PWDs to be independent. |

| Ensure full and active participation and inclusion in the society. | This must include participation in DRM programmes, planning, and policy development. |

| Prevent or prohibit discrimination against a PWD. | Remove institutional and environmental barriers. Enforce barrier-free environments for PWDs. |

| Promote respect for and acceptance of PWDs. | Recast PWD from victim to resource person and demonstrate full appreciation of skills a PWD can bring to DRM. |

Note. Requirements under the Disabilities Act from the Disabilities Act (2014)

The government should also ensure accessibility of all communication related to DRM to all sectors of PWDs. Explanatory text should accompany figures and maps. All visual announcements should be accompanied by sign language interpretation, and techniques such as shading and cross hatching should be used in addition to colours for warning signs. Inclusion of PWDs and disabled persons' organisations in DRM planning should be mandated. In addition, government entities should include reporting on progress on disability inclusion as part of their regular reporting schedule for Vision 2030 Jamaica.

Developing a Disability-friendly Disaster Plan

Kailes and Enders (2007) propose a function-based approach to emergency planning for persons with impairments and suggest that this approach should be interwoven into emergency planning. The CMIST framework comprises five function-based planning elements: communication, medical needs, maintaining functional independence, supervision and transportation which emergency planners can use to plan for a wide range of requirements for persons with impairments as well as those with functional limitations such as language differences, hearing or cognitive limitations which are not met by the standard emergency planning approaches. An adaptation of the CMIST framework to Jamaican DRM planning could see emergency planners adjusting their approaches in the following areas:

Communication

Provision of information in formats which are understandable and usable. Current methods are based on announcements usually carried by radio and television. Ensuring more inclusive information dissemination would involve sign language accompanying television broadcasts, large print posters with latest information in easy-to understand format placed in public places such as police stations and post offices and the use of community networks to provide information for persons who are home-bound.

Medical Needs

Disaster plans do not currently cater for persons with medical needs. Such needs would be covered under hospital plans. However, some medical needs may not require hospital care. Equipping emergency shelters with appropriate levels of equipment and trained staff could meet medical needs such as routine injections, intra-venous care, vital signs monitoring, and administering medication.

Maintaining Functional Independence

Many persons such as the elderly can manage with assistance. Provision for replacement of equipment, such as canes, wheelchairs, crutches which may be left or displaced during evacuations should be made, as well as ensuring emergency power supply for equipment dependent on electricity. Providing for caregivers in emergency shelters may also be necessary. Displaced persons may also require provision of personal care assistance for persons in need who are separated from family care.

Supervision

Provision of supervisory care for persons suffering from trauma, anxiety, depression and children separated from families. This would also include ensuring safety and security for vulnerable persons in shelters. These elements could be integrated into existing plans for post-impact psychosocial support.

Transportation

Currently, evacuation plans call for provision of buses to transport evacuees without transportation. However, some persons may have difficulty reaching transportation assembly points. Community based and organised networks could register those in need of transportation and arrange for conveyance to transportation points.

Development of disaster plans using this framework would require an adjustment in current approaches to planning, which although participatory, still places responsibility for much of the input on the local and national governments. The approach suggested under the CMIST framework requires a high level of local knowledge and input and would place additional burden on parish and community organisations. Greater integration of non-emergency personnel such as community health aids will be required. In addition, more partnerships which can provide volunteer support such as with faith-based organisations and service clubs would have to be built.

With some additional planning, some elements could be integrated into ongoing activities. For example, identification of persons in need of transportation could be done as part of a school project. Volunteers for supervisory duties could be part of a faith-based organisation's or service club's outreach ministry or programme.

Despite some progress being made there is need for the government at national and parish levels to implement its policies and to set an example by complying with its laws designed to ensure full participation of PWDs in society including equal access to information, equal access to facilities and inclusion in DRM programming and planning. This would allow PWDs to fully exercise their social rights as citizens.

Further Research

The results of this exploratory study indicate that disability inclusiveness has not been achieved by many government entities charged with responsibility for policy implementation and with the responsibility of setting the example by obeying the country's laws. There are indications that efforts are being made, including examples of pilot-type projects to work with PWDs on DRM issues. Respondents showed a high level of awareness of the necessity of inclusion. The question seems to be how to translate these pilot initiatives as well as awareness and knowledge into action on a wider scale in order that all or the majority of PWDs may benefit. The need for further research on inclusiveness of PWDs in the public sector is suggested. This should include surveys across all government entities including statutory bodies, departments and agencies. There is need for further definition of barriers to inclusiveness and challenges to policy implementation and adherence to the law among public sector entities. Inclusion of a wider cross-section of PWDs and disabled persons' organisations through the use of surveys and focus groups to document their experiences and to differentiate experiences of persons with different impairments is also indicated. There is an opportunity for interdisciplinary research which could include examination of societal attitudes to impairments and to PWDs and how these attitudes might affect disability inclusiveness. Research into the best methods of providing differentiated information to persons with different types of impairments would also be useful.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Parish Disaster Committees and the Government Ministry representatives for taking the time to complete the surveys for this research. We acknowledge the Principals of the two educational institutions for allowing us access, and express our gratitude to the staff, students and caregivers who contributed to the focus group discussions. Additionally, we thank the anonymous reviewers for their comprehensive and constructive comments which strengthened this manuscript.

References

- Anastasiou, D., & Kauffman, J. (2013). The social model of disability: Dichotomy between impairment and disability. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 38(4), 441-459. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jht026

- Berke, P., Cooper, J., Salvesen, D., Spurlock, D., & Rausch, C. (2011). Building capacity for disaster resiliency in six disadvantaged communities. Sustainability, 3(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su3010001

- Carby, B. (2011). Caribbean Implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action HFA Mid-Term Review, Caribbean Risk Management Initiative – UNDP Cuba. Retrieved from http://www.unisdr.org/files/18197_203carby.caribbeanimplementationoft.pdf.

- Carby, B. (2015). Beyond the community: Integrating local and scientific knowledge in the formal development approval process in Jamaica. Environmental Hazards, 14(3), 252-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2015.1058740

- Chou, Y., Huang, N., Lee, C., Tsai, S., Chen, L., & Chang, H. (2004). Who is at risk of death in an earthquake? American Journal of Epidemiology, 160(7), 688-695. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh270

- Cutter, S., Boruff, B., & Shirley, W. (2003). Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Social Science Quarterly, 84(2), 242-261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6237.8402002

- The Disabilities Act, No. 13. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.japarliament.gov.jm/attachments/341_The%20Disabilities%20bill%202014%20No.13.pdf.

- Kailes, J. and Enders, A. (2007). Moving beyond 'Special Needs' A Function-based framework for emergency management planning. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 17(4), 230-237. https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073070170040601

- Kieck, B., Ayeh, D., Beitzer, P., Gerdes, N., Günther, P. & Wiemers, B. (2016). Inclusion grows toolkit on disability mainstreaming for the German Development Cooperation. Retrieved from http://edoc.hu-berlin.de/series/sle/265/PDF/265.pdf.

- Hemingway, L., & Priestley, M. (2006). Natural hazards, human vulnerability and disabling societies: a disaster for disabled people? Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 2(3). Retrieved from https://www.rdsjournal.org/index.php/journal/article/view/337.

- Inter American Development Bank. (2009). Catastrophe Risk Profile for Jamaica. Retrieved from http://pioj.gov.jm/Portals/0/Sustainable_Development/Catastrophe%20Risk%20Profile%20for%20Jamaica.pdf.

- Jagger, J. (2011). Disaster management policy and people with disabilities in the United States and Jamaica (PhD thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia). Retrieved from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3427&context=etd.

- MacGregor, M. (2012). Citizenship in name only: Constructing meaningful citizenship through a recalibration of the values attached to waged labour. Disabilities Studies Quarterly, 32(3). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v32i3.3282

- Morris, J. (2005). Citizenship and disabled people: A scoping paper prepared for the Disability Rights Commission. Retrieved from http://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Citizenship-and-disabled-people_A-scoping-paper-prepared-for-the-Disability-Rights-Commission_2005.pdf.

- National Advisory Council on Disability. (1999). National policy for persons with disabilities. (Class No. 334.02-056.26 (729.2)). Jamaica.

- Najafi, M., Ardalan, A., Akbarisari, A., Noorbala, A.A., & Jabbari, H. (2015). Demographic determinants of disaster preparedness behaviours amongst Tehran inhabitants, Iran. PLOS Current Disasters, (1). https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.976b0ab9c9d9941cbbae3775a6c5fbe6

- Njelesani, J., Cleaver, S., Tataryn, M. & Nixon, S. (2012). Using a human rights-based approach to disability in disaster management Initiatives. In S. Cheval (Ed.), Natural Disasters (pp. 21-46). InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/32319

- Potter, R. B., Barker, D., Conway, D., & Klak, T. (2004). The contemporary Caribbean. New York: Prentice Hall.

- Statistical Institute of Jamaica. (2011). Population census 2011. Retrieved from http://statinja.gov.jm/Census/PopCensus/Popcensus2011Index.aspx.

- Wisner, B. (2002). Disability and disaster: Victimhood and agency in earthquake risk reduction. In C. Rodrigue and E. Rovai (Eds.), Earthquake. London: Routledge. Retrieved from http://www.asksource.info/resources/disability-and-disaster-victimhood-and-agency-earthquake-risk-reduction.