This essay explores the experiences of persons with significant intellectual disabilities at the Vermont State School for Feebleminded Children (later Brandon Training School) in the period 1915-1960. We discuss the limits of existing histories of intellectual disability in accounting for the distinct experiences of significantly intellectually disabled people. This essay works to correct the tendency to define the nominal intellectual disability of "morons" and "borderline" cases — both in the past and in disability historiography of the past — against the abject, embodied difference of the "low-grade idiot" or "imbecile." The history we offer has implications for the present-day disability rights movement.

Across the highway from the former Brandon Training School in Brandon, Vermont lies the Pine Hill Cemetery. For the most part, Pine Hill is typical of Vermont burial grounds: varied grave markers are clustered into family groups, and many are inscribed with epitaphs or with simple phrases like "beloved mother" or "our son." In a separate section of the cemetery, the remains of a few dozen Brandon inmates are buried in neat rows beneath uniform, nondescript stones containing only inmates' names, years of birth and death, and the initials "B.T.S." Some of the "B.T.S." markers record lives that ended in childhood, possibly as a result of dire institutional conditions. Others record lives that spanned several decades of institutional living. None of the markers reveal how such people lived or to whom their lives mattered. Were they someone's mother or son? Did they find meaning and purpose in their institutional lives? Were they loved, and did they love in return? When they died, did others mourn their deaths?

If the grave markers tell us next to nothing about the lives of deceased inmates, existing histories of intellectual disability tell us little more. Recent scholarship explores the role of eugenicists and medical experts in constructing the discriminatory category of "feeble-mindedness." In applying the social model of disability to the history of institutions like Brandon, such work typically foregrounds the experience of nominally "feeble-minded" people whose institutionalization owed as much to ethnic, racial, class, and sexual prejudices as to intellectual impairment. While such work is important, it consigns inmates with profound intellectual impairments — those whose experiences and needs are harder to reconcile with the social model — to the margins of disability history. Labeled "low-grade idiots and imbeciles," such inmates were especially likely to enter the institution as young children and remain there until they died. Their remains were particularly likely to go unclaimed by family members and to be buried in the Pine Hill Cemetery across the road.

Our work foregrounds the institutional lives of "low-grade idiots and imbeciles." Such inmates occupied the lowest rungs in a hierarchy of intellectual disability that differentiated between "borderlines," "morons," "imbeciles," and "idiots." Their presence at institutions like Brandon was not incidental, but rather fundamental to the eugenic project. Their abjection as "helpless, custodial inmates" fortified administrators' claims that "higher-grade morons" and "borderlines" benefited from rudimentary training or education and thus were worthy institutional subjects.

In focusing on the untold stories of "imbeciles" and "idiots," we are motivated, in part, by a very personal desire to develop a "useable past" for Robbie, a young man diagnosed with "low-functioning autism" and intellectual disability. Had Robbie been born in the early twentieth century, he might easily have been classed as a "low-grade, untrainable idiot" and relegated to a "custodial" ward of the Brandon Training School. His remains, too, might have been buried just beyond the institution's gates. Robbie likely would not have been permitted to live, as he currently does, at home in central Vermont, where he receives family and community support to attend high school, pursue his interests in puzzles, nature, and cooking magazines, and form rewarding personal relationships with a variety of partners. Not only is it unbearable for us to imagine Robbie's life in an institution; it is equally unbearable for us to imagine our community without Robbie and other persons with significant intellectual disabilities in it. That is not to say the circumstances of persons with significant intellectual disabilities in the present day are ideal — far from it.

Developing a "useable past" for Robbie and other persons with significant intellectual disabilities is crucial if we are to understand the limits of current social and civic policies affecting such persons. In looking back at the history of the Brandon Training School, we recognize that, while present-day conditions are generally better for persons with profound intellectual disabilities than they were in the era of institutionalization, troubling continuities are evident. Among those continuities is a tendency to base our understanding of intellectual disability primarily on the examples of persons with mild intellectual impairments.

Scholars have been critiquing the social model of disability for some time. What is the precise relationship between what we call "disability" and what we call "impairment"? What does it mean to say that disability is constructed and impairment is not? How do we account for the materiality of human embodiment in the social construction of disability? And how do we account for people like Robbie, whose cognitive impairments are, in the words of Eva Feder Kittay, "not merely contingently disabling"? 1 Our analysis does not attempt to answer all of these questions, but it raises them to illustrate the contested limits of the social model. Allison Carey acknowledges that the social model, as it is often applied, supports a liberal, rights-based notion of disability justice. 2 It assumes that, were the limitations of social context rectified, persons with intellectual disabilities would be capable of informed participation in the social contract. Kittay notes that this might be true for people with mild intellectual impairments — precisely the group on whom most historians of intellectual disability have focused their work. 3 But it would exclude persons with more profound intellectual disabilities, who are the subject of this study. In undertaking the history of persons with significant intellectual disabilities, we seek to historicize contemporary debates about the limits and possibilities of disability justice. How might a history of significant intellectual disability prompt us to reconsider the scope of present-day disability activism, with its over-reliance on the cognitively ableist model of disability civil rights?

Certainly, scholarship that utilizes the social model to interrogate the historical intersection of eugenics, institution building, and feeblemindedness contributes immensely to our understanding of the past. James Trent's Inventing the Feeble Mind exemplifies the value of such work. 4 Trent argues that persons labeled "feebleminded" endured lifelong degradation and violence in public institutions in order to serve the ideological and professional interests of institution administrators and eugenicists. The breadth of Trent's study, which encompasses several institutions over 150 years, is impressive. While focusing specifically on the American South, Steven Noll also documents the racial, class, and cultural prejudices that informed diagnoses of feeblemindedness, institutionalization, and sterilization in the early twentieth century. 5 In their collaborative work, Trent and Noll argue that the history of feeblemindedness is one of "control and care" — control of "high-grade" feebleminded inmates, who performed essential, unpaid labor to maintain the institution, including shouldering a considerable burden of care for "low-grade" fellow inmates. 6

Yet while Trent and Noll's "control and care" hypothesis is sensitive to the wrongful exploitation of "high-grade" inmates, many of whom surely did perform unpaid care work, it does less to address the particular experiences of so-called "low grade" inmates who were ostensibly the objects of that care. Neither Trent nor Noll precisely discusses how persons labeled "idiots" and "imbeciles" experienced the regulatory apparatus of the institution. Partly, this is due to the paucity of available sources. After all, "low-grade" inmates frequently lacked conventional speech, to say nothing of the capacity to record their experiences in letters or diaries. Superintendents and their eugenic collaborators were generally too preoccupied with "morons" and persons of "borderline intelligence" to report extensively on "idiots" and "low-grade imbeciles." And yet, more than simply objects of unpaid, "high-grade" inmate care, inmates with more significant intellectual disabilities were sensitive human beings who deserve a history of their own. Given the lack of readily available source materials, how do we document the experiences of this stigmatized population? And why can we not allow the experiences of more easily documented "high grade" inmates to stand in for the rest?

One reason that we cannot generalize from the experiences of literate, "high grade" inmates is that, within institutions for the "feeble-minded," the status of "high grade" and "low grade" inmates was diametrically opposed. A rigid hierarchy of intellectual classifications governed every aspect of institutional life. "High grade" inmates had access to rudimentary education and training by virtue of what they were not: wretched, untrainable "idiots" and "imbeciles." One section of this essay documents the structure of intellectual classification that defined "high grade" feeble-minded inmates against the abject, embodied difference of their "low-grade" counterparts.

If we accept that "high grade" inmate experiences are not representative of the whole, then how do we document "low-grade" inmates' lives? In part, we must look at the discursive construction of "low grade" intellectual disability as it was crafted by institution administrators, eugenicists, and doctors. Because "high-grade" inmates were at the center of the institutional project, we must attend closely to every occasion when "low-grade" inmates were discussed. Given the limits of written sources in documenting the lives of people with impaired verbal communication, we must also attend to the spatial and material dimensions of "low-grade" institutional life. What spaces did "low-grade" inmates inhabit? How limited was their mobility? With whom did they interact in the spaces they occupied? Such details can be discerned from institutional records, particularly visual records such as photographs and site plans. Taken together, they help to compose a portrait of everyday life for "low-grade" inmates at the Brandon Training School.

Part of what defined "low-grade" inmates was their need for assistance with activities of daily living. Thus, looking at what Kittay has termed "dependency relations" is crucial to understanding "low grade" inmates' lives. 7 In documenting conditions of care at the institution, we do not assume that inmates with significant intellectual disabilities were passive recipients of care. Rather, we explore both the care inmates received, which surely shaped their lives, and inmates' challenges to care. Those challenges included noncompliance with institutional routines, pleasure-seeking, and other kinds of mental and physical activity that confounded care workers' preference for quiet, "inactive" charges.

Shifting the focus from "high-grade" to "low-grade" inmates prompts us to reconsider the periodization of institutions for the intellectually disabled. Whereas the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are most fruitful for contemplating "high grade feeblemindedness," inmates with more significant intellectual disabilities became a majority at institutions for the intellectually disabled by the mid-twentieth century — precisely the moment at which many histories of intellectual disability end. Carey notes that even histories that encompass the entire twentieth century tend to gloss over the period from 1940 to the 1960s — a period that is crucial for understanding the institutional experiences of persons with significant intellectual disabilities. 8

In offering an alternative history of intellectual disability that encompasses the mid-twentieth century, we do not mean to discount the scholarly consensus that, from their inception, institutions for the "feebleminded" constructed intellectual disability in ways that reflected the ethnic, racial, class, gender, and sexual biases of administrators and eugenicists. Rather than seeking to subvert that historical narrative, we offer a parallel narrative — one that accounts for how the discourses of "feeblemindedness" and "mental deficiency" relied on and reinforced a discriminatory system of categories — "borderline," "moron," "imbecile," and "idiot" — that mapped onto the diverse bodies and minds of people with intellectual disabilities in highly discriminatory ways. Our narrative also accounts for the fact that some people with intellectual disabilities have real and profound impairments, the exigencies of which demand models of disability history and disability justice that move beyond the expectation of articulate self-expression within a universally accessible liberal public sphere.

The resulting, altogether partial history of Vermont's Brandon Training School spotlights the lives of so-called "low-grade" inmates throughout the period 1915-1960. It is organized into three sections. The first addresses how the relational construction of "borderlines," "morons," "imbeciles," and "idiots" adversely affected inmates with significant intellectual disabilities. The second examines the conditions of care work at the institution, since care workers loomed large in significantly disabled inmates' lives. And the third examines the limits and possibilities of intimacy for "low-grade" inmates, who were often labeled sexually perverse and yet whose opportunities for sexual and other intimate relationships were denied. In approaching each of these topics, we seek to demonstrate the need for a more complicated social constructionism — one that attends to the confounding materiality and diversity of intellectually disabled people's lives.

The Relational Construction of "High-Grade" and "Low-Grade"

As the state's only public institution for people with intellectual disabilities, the Vermont State School for Feeble-minded Children, which opened in 1915, was initially charged with the task of caring for and training the State's "feebleminded" children between five and twenty-one years of age. In 1919, however, reflecting the eugenic concerns of Vermont lawmakers and experts in the field of mental deficiency, the School's mandate was expanded to include "feebleminded women of childbearing age." 9 Because no other public institutions, besides town poor farms, were open to people with intellectual disabilities, the Vermont State School quickly exceeded its enrollment limit and overcrowding became a perennial problem. In this context, administrators were loath to admit people with significant intellectual disabilities for a variety of reasons: first, because they were recognizably defective and thus posed less of a eugenic threat than "high-grade" children who could "pass" as normal; second, because they were deemed "unimprovable" and thus would remain a burden on the institution well into adulthood; and third, because their imputed savagery, animalism, and generally repulsive bearing was perceived as physically and morally polluting to the broader community of the School. Thus, while Superintendent Truman J. Allen acknowledged in 1920 that the problem of feeblemindedness included "idiots and imbeciles of low order," he stressed that the School's primary concern was with "higher grade morons" and "borderline" cases. 10 Allen argued that with proper scientific and educational treatment — and without the distraction of having to contend with large numbers of "low-grade" defectives — such "high-grade" residents could learn to approximate "normal" members of society. 11

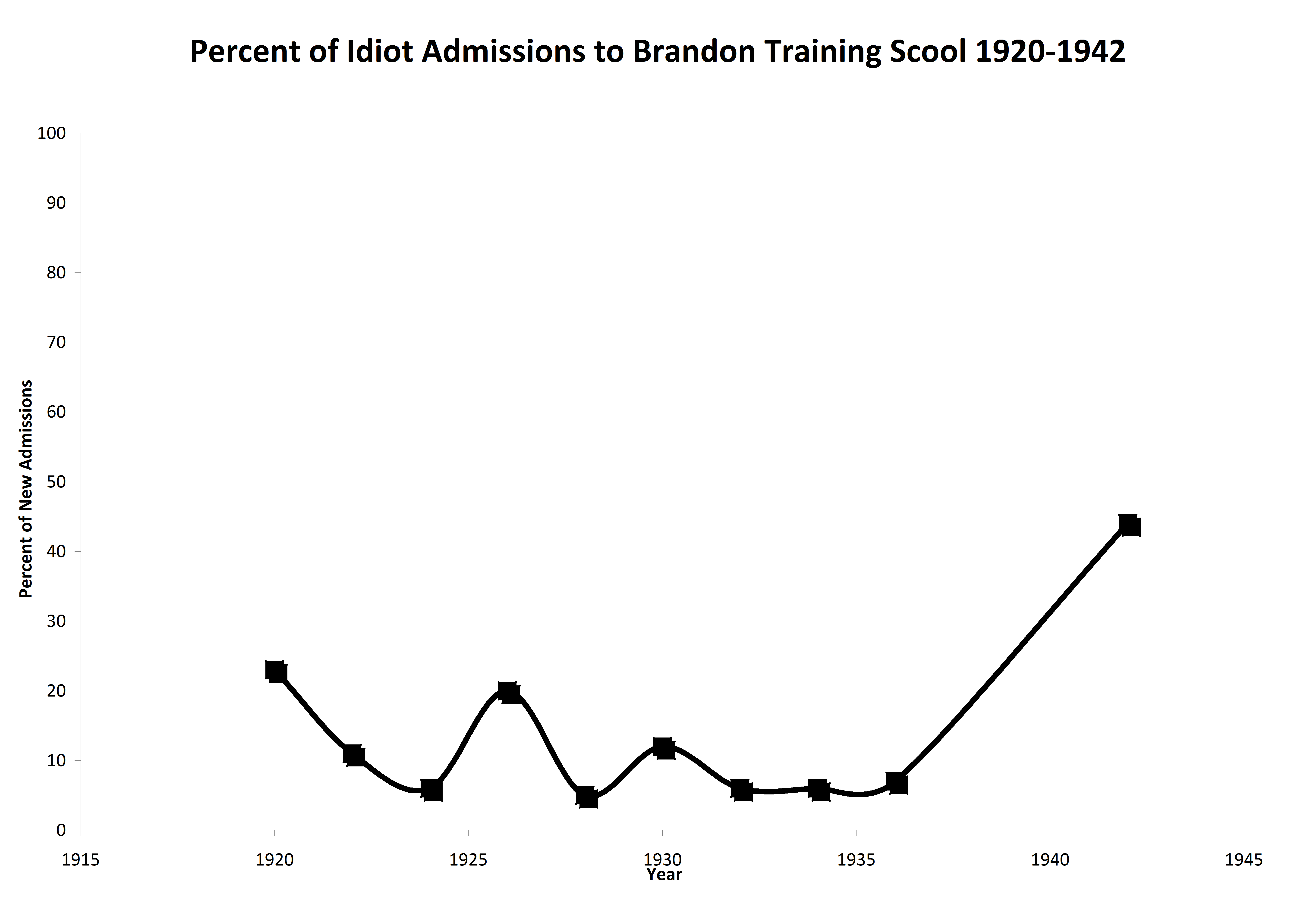

In spite of administrators' insistence that the school should serve "trainable" mental defectives, more significantly and often multiply disabled persons were admitted to the Brandon Training School in every biennial period. The following chart shows admission rates of "idiots" as a proportion of overall admissions for the period 1920-1942 12:

Text description: Graph shows the proportion of "Idiot" Admissions to the Brandon Training School for the Period 1920-1942. The graph indicates that people with significant intellectual disabilities were always present at Brandon, and that their proportion of the total increased dramatically in the 1930s.

Because administrators regarded "idiots" as a negative influence on "higher-grade" feebleminded children, they constantly stressed the importance of segregating the living, social, and learning spaces of the "high-grade" residents from the more rudimentary spaces dedicated to the care of significantly disabled residents. While the school maintained a modest academic program and more elaborate, gender-segregated manual training facilities for "high-grade" boys and girls, "low-grade" residents were, particularly in the early decades of the institution, simply housed there, though some "lower grade" inmates performed care work in "custodial" wards. "Low-grade" inmates rarely left their dormitories (which were segregated by intellectual ability) and certainly did not leave the grounds of the institution except for medical emergencies in the first three decades of the school's operation.

Throughout the period 1915-1960, Brandon administrators railed against their custodianship of "idiot" cases, emphasizing that their mission was to segregate and improve "higher-grade imbeciles," "morons," and "borderline" cases. While recognizing that some "custodial" cases could not adjust to community life and thus belonged in institutions, Allen argued in 1922, "so far as possible [the institution] should serve as a training school rather than an asylum for custodial cases." 13 In his 1926 report to the State Legislature, Allen declared that the School's purpose was to "develop pupils morally and industrially, promote physical well-being, and provide with scholastic privileges suited to their intellectual powers." 14 A regular feature of Allen's reports was his account of the physical and moral improvement of the "high-grade" residents under his care. In contrast to abject "idiot" bodies, Allen wrote, the School's "trainable" residents were, "with few exceptions … strong, hardy, well-nourished, and in good health. Sunshine, fresh air, cleanliness, exercise, and work as well as a carefully regulated dietary [sic] are the chief measures that insure their good health and happiness." 15

Evidence is less clear cut that significantly and multiply disabled residents were healthy. "Idiots" were disproportionately represented among recorded deaths at the institution, and the tone in which they were reported suggests that such deaths were counted as less regrettable than other deaths. For example, in his 1918 report to the Legislature, Allen acknowledged the death of a "paralytic boy of low grade mentality," as well as an "idiot girl," who died of influenza, and a "Mongolian idiot girl," who suffered a fatal infection of the larynx. 16 In 1939, 100 "low-grade" residents fell ill and five died when an epidemic of bacillary dysentery struck the "low-grade" boys' and girls' dormitories. 17 No "high-grade" deaths were reported. In 1942, the School reported an "unusually high number of deaths among idiots from Cachexia [low weight, wasting away] and Inanition [lack of mental rigor]." 18 Roughly translated, these deaths were caused by starvation and associated delirium. Once again, the biennial report minimized the significance of "idiot" deaths, claiming that some of the deceased had already been ill at the time of admission. Dental care also varied considerably between "high" and "low-grade" residents. 19 While "high-grade" inmates received full dental checkups, "low-grade" inmates did not. Finally, as the institution aged, so did its "low-grade, custodial" residents, much to the chagrin of School administrators. The aging and often multiply disabled bodies of significantly disabled inmates deviated considerably from administrators' idealized image of Brandon pupils as young, vital, and physically and morally healthy.

In his biennial reports, Allen repeatedly argued that towns and local communities, and not the School, should properly care for "helpless custodial cases." In making this claim, Allen hearkened back to Vermont's long tradition of cheaply housing persons with significant intellectual disabilities on town poor farms. In 1924, he wrote, "To herd all defectives into an institution is unnecessary and undesirable. It is furthermore prohibited by the burden it would impose upon the taxpayer." 20 If towns were to care "for certain lower grade custodial subjects, especially adults," the School could discharge its privileged obligation to segregate and improve "high-grade, trainable" children. 21 Frustrated that many "high-grade" children languished on Brandon's waiting list while "idiots and imbeciles" occupied spaces at the School, Brandon implemented a parole program in 1928. 22 Chief among those considered for parole were "the more helpless custodial type for whom the home can often provide." 23 From Allen's perspective, sending home "the more helpless custodial type" did not mean releasing them to move freely about the community; rather, it meant consigning them to the attics and back rooms of Vermont farmhouses while making room at the institution for more worthy "morons" and other "educable" children.

In 1936, Allen stated that the institution's most important objective was research into "the causes and nature of the mental deficiencies." After that, he prioritized the "eugenic, social, and medical" prevention of mental deficiency and its correction through education and training. 24 Allen dismissed the importance of merely caring for inmates, writing, "The matter of greatest concern is not how well such a group is cared for, but rather how much is known about them." 25 Formerly a professor of neurology at the University of Vermont College of Medicine, Allen was eager to remain active in academic circles, and superintending an "asylum" for "low-grade" inmates was not compatible with his ambitions. Instead, he ran the institution as "a training center for colleges and school groups," and he encouraged such groups to visit Brandon to study its population of "high-grade" defectives. 26 Allen thus used "young, educable morons" to advance his professional standing as an expert in the field of mental deficiency.

Allen rarely discussed "custodial" inmates except to lament their hopelessness and disruptiveness to the training program at the institution. When he did discuss them, he minimized their presence, calling them "a smaller number" in contrast to "morons," whom he referred to as a "large proportion of mentally subnormal persons." 27 It was not until after Allen's death in December 1937 that the increasing proportion of "low-grade" to "high-grade" inmates became known. In their 1940 Biennial Report, Medical Director Frederick C. Thorne and Superintendent A.D. Barnard disclosed that, "About fifty percent of the school population consists of extremely low-grade children for whom the school can only provide custodial treatment and care." 28 While Thorne and Barnard were more willing to acknowledge that "low-grade" inmates were a significant presence at the school, they shared Allen's preference for teaching "the remaining fifty percent [with] less serious defects." They wrote, "The major objectives and resources of the school must be directed toward the education and rehabilitation of the borderline group of children." 29 Like Allen, they held a low opinion of more significantly disabled inmates, whom they described as "a burden and potential moral menace wherever they exist." 30

World War II provided an additional rationale for favoring "high-grade" inmates. In 1942, Thorne and Barnard wrote, "Every mentally defective child who can be trained so as to become economically independent not only relieves the State of Vermont of an economic and moral burden but also contributes to the national defense effort." 31 Clearly, at a time when public institutions were eager to demonstrate their contributions to the war effort, caring for more significantly disabled inmates was less desirable that training "high grade" inmates to participate in national defense.

Even so, by 1942, Thorne and Barnard calculated that 63 percent of the inmate population was composed of "permanent institutional cases." In part, the increasing proportion of "low-grade" inmates was due to a new State law that prohibited the practice of housing intellectually disabled adults on town poor farms. 32 In reaction to the law, Thorne and Barnard complained, "The Brandon State School is steadily accumulating a population of permanent custodial cases and in a few short years the school will become little more than a home for aged and infirm mental defectives." They added, "As this custodial population grows larger, there is less and less room and facilities for the education of brighter young defectives." 33 Far from embracing the inmates transferred from town farms, they expressed regret that "the pressure of public demand … no longer tolerates these hapless individuals to go uncared for in local communities." 34

Even as "low-grade" inmates became a majority at the institution, Thorne and Barnard continued to stress the relative importance of training and educating "high-grade" inmates. And yet, in 1946, they wrote, "The discouraging fact is that the institution is becoming less and less of a training school and more of a custodial home for lifetime cases." 35 Their successor, Superintendent Francis W. Kelly, shared their discouragement. In 1947, Kelly complained that the institution could no longer function properly as a training school because "custodial individuals just do not have the intellectual capacity to accept such training." 36 In fact, "lower grade" inmates were categorically excluded from the school program, which only accepted inmates with IQ measurements of 50 or higher. 37 Thus a majority of inmates, many of whom might have benefited from developmentally appropriate academic enrichment, were denied the opportunity to learn.

In 1948, Superintendent Kelly acknowledged that the institution was overcrowded and understaffed, with extremely high employee turnover and a physical plant in disrepair. In particular, Kelly noted that Dormitory A, which housed "low-grade" male inmates, "was extremely damp and dark; difficult to ventilate in the summer months, and difficult to heat in the winter." 38 And yet, like administrators before him, Kelly did not prioritize correction of those problems but rather stressed the need to establish "adequate segregation of the Trainable from the Custodial group." 39 While only seventy-five children (19 percent) attended academic classes in 1948, the institution devoted considerable resources to erecting a new school building that year.

By the 1950s, "custodial inmates" had long been an established majority at the institution. And yet the administration clung to its vision of Brandon as a school whose mission was to serve "high-grade" children. As Superintendent Francis W. Russell wrote in 1956, "children who are severely retarded cannot gain very much through an organized training program as is found here at Brandon." 40 Rather than adjust the programming to reflect the preponderance of inmates with significant intellectual disabilities, Russell, like his predecessors, continued to focus on the perceived needs of the institution's diminishing proportion of "high-grade" inmates.

The Brandon Training School implemented an expanded recreation program in the 1950s. While positive for eligible children, the new recreation program underscored the vast disparities between "high-grade" and "low-grade" status. In 1955, the institution inaugurated an overnight summer camp program on nearby Lake Bumoseen, but only 160 "educable" and "trainable" children out of a population of 547 were eligible to attend. 41 "High-grade" children also had opportunities to join basketball and softball teams, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, a glee club, a drama club, and a square dancing group. Some of these groups made regular excursions to participate in competitions or exhibitions at locations throughout the state. 42 Alvah Holmes, the newly appointed recreation director, reported that Brandon's top one hundred students were also able to go to the State Fair in Rutland. Holmes described the fair experience as follows: "This is probably the biggest even of the year for the students. They love to look over the exhibits and displays. Rides and sideshows are had by all with popcorn, hotdogs, and pop as part of the outing." 43

While access to such recreational opportunities was hardly recompense for the dehumanizing conditions that "high-grade" inmates endured, it marks a stark contrast to the experience of the vast majority of inmates whom the institution classified as "low-grade." In 1956, Holmes wrote movingly of how some inmates with significant intellectual disabilities responded when they first had the opportunity to ride on the school's "brand new Chevrolet school bus" in September 1955: "During the next few days and evenings, every child who could had a ride; some were carried into the bus. To many this was their first ride, some laughed with joy, others cried not of fright but of joy, and it was very touching to us who went with them…" 44

Holmes' description offers a rare glimpse of the emotional texture of "custodial" inmates' lives. Generally regarded as "hopeless" and "hapless," such inmates spent their days and nights in bleak, overcrowded dormitories. It is little wonder, then, that some cried tears of joy when they were loaded onto a clean, fresh-smelling school bus and transported off the grounds of the institution, if only for a brief ride. Holmes was so moved by inmates' pleasure that he resolved, "Rides will be taken by some inactive groups, once a week." While Holmes also introduced "games and music" to "the lower grade dormitories," such activities, even when supplemented by weekly bus rides, compared poorly with the athletic contests, dramatics, singing and square-dancing, Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts, and special outings that "high-grade" inmates could pursue. How do we interpret Holmes' observation that "inactive" inmates "laughed… and cried [tears] of joy" when given the opportunity to ride on the school bus? How much happier might those same inmates have been had they been able to attend the school, go to a lakeside summer camp, or see the exhibits, rides, and sideshows while enjoying popcorn and hotdogs at the State Fair?

Reflecting the bias and frustration that he shared with all of his predecessors, Superintendent Russell declared that "as more severely retarded patients are admitted there will soon come a point where the entire population of the school will be of such a grade as to be untrainable." Reflecting his conviction that no self-respecting professional would want to work with such "severely retarded patients," he predicted, "At this point… [Brandon Training School] will not attract the type of professional personnel that an institution of this type deserves." 45 Russell himself tired of superintending an institution that housed so many "severely retarded" inmates in 1960, and he left to pursue other professional opportunities.

Probing Dependency Relations and Material Conditions of Care

The social model of disability envisions an ideal society in which all persons have the resources they need to exercise independence and participate equally in democratic decision-making. As such, the social model fails to account for persons with significant cognitive impairments who, under the best of circumstances, lack the capacity for rational deliberation and must rely on others to meet basic dependency needs. Kittay argues that the concept of autonomous selfhood at the heart of the social model is illusory; we are all relational beings, and we all experience dependency as care givers and recipients at various times in our lives. Thus it is only by probing dependency relations that we can understand what it means to be fully human. 46 Probing dependency relations is particularly important for understanding the experience of persons with profound intellectual impairments, including those who resided at the Brandon Training School in the period 1915-1960. Documenting dependency relations at Brandon does not tell us what inmates with significant intellectual disabilities thought or felt about institutional caregivers, but it does help us to understand what they endured — and endured differently from inmates with mild or moderate intellectual disabilities.

Even before the Vermont State School for Feeble-Minded Children opened its doors in 1915, experts in the field of mental deficiency remarked on the challenges of attendant care. As Delia E. Howe, resident physician at the Indiana School for Feeble-Minded, wrote in 1897, those challenges included inadequate training for careworkers, stressful working conditions, long hours, low wages, and a failure on the part of administrators to prioritize or invest in attendant care. Howe asserted that it is "impossible for the ordinary person to work from thirteen to fifteen hours a day at tasks requiring thought and patience, and not begin to shirk or grow irritable." 47 Attendants occupied a lowly and stigmatized status. Since both "the patients and the work are devalued," Howe observed, "the mass of citizens … believe that only coarse, unsympathetic people would voluntarily accept the position of attendant upon the insane or feebleminded." 48 She argued that attendant care must be more positively valued, and attendants must have better training and opportunities for respite, both for their own sakes, and for the sake of the inmates who depended on them for care.

Published at the turn of the twentieth century, Howe's prescription for better attendant care was echoed repeatedly in decades to come. Writing in 1904, Martin W. Barr, chief physician at the Pennsylvania Training School for Feeble-Minded Children, acknowledged the importance of institutional care work. He stated, "The character of attendants is of the first importance, as these are they who live with the children." 49 Attendants should possess "an even temperament," he wrote. Revealing his aversion to the "mental defectives" about whom he wrote prolifically, Barr stated that "dealing with natures almost wholly animal requires a certain refinement and dignity of character." 50 Like Howe, Barr argued for higher wages and shorter hours so that qualified attendants could be recruited and retained.

Writing in 1912, Henry B. Gaynor, physician at the Polk State School in Pennsylvania, argued that while the need for qualified personnel was great, "Our standard as applied to the attendant is at present very low." Individuals hired were "seldom educated, and very often not trained" in spite of the challenging nature of the work. "Often we have seen the advertisement, 'Attendant wanted; wages ____.' We may or may not inquire into the capabilities and character of the applicant… The person is employed and his duties are rather indefinitely explained." 51

While Howe, Barnard, and Gaynor drew attention to the difficulties of attendant care in 1897, 1904, and 1912 respectively, the problems they described — low pay, long hours, indiscriminate hiring, and lack of training — remained characteristic of attendant care throughout much of the twentieth century. Certainly, their observations accurately describe the situation at the Brandon Training School from its founding in 1915 through the 1950s and beyond. 52

Inmates at the Brandon Training School had more contact with ward matrons and attendants than with any other employees at the school. This was especially true for inmates with significant intellectual disabilities, who were excluded from educational and training programs and were often confined to dormitories. The only contact that many significantly disabled inmates had, besides with each other, was with the attendants who were responsible for their care. Throughout the period 1915-1960, attendant care at Brandon was far from adequate and often inhumane. Ward personnel worked long hours for extremely low pay. They received little or no training and yet were expected to complete a daunting array of tasks including keeping the dormitories clean, feeding, bathing, and dressing inmates, nursing the sick, and managing ward behavior. Wards were often overcrowded, increasing attendants' burden. Attendants who worked in "custodial" wards not only had continuous contact with inmates; they also experienced the stigma of association with a class of inmates whom many, like Barr, regarded as more animal than human. Turnover among ward employees was extremely high. Endemic understaffing also led to indiscriminate hiring and reluctance to discharge recalcitrant workers. In 1934, for example, Brandon employed only 18 direct caregivers for an inmate population of 276. 53 Given all of these considerations, it is not surprising that attendants at Brandon sometimes disregarded the humanity of the inmates in their care.

Evidence of how little administrators thought about care work at Brandon can be seen in the almost total absence of references to attendant care in the biennial reports to the state legislature from 1915 to 1950. While in 1930, Superintendent Allen briefly acknowledged that "care…is a task requiring careful study and attention in sanitary and hygiene matters," his own reports to the legislature focused almost exclusively on the institution's physical plant, its educational program for "high grade" children, financial accounts, and his own professional activities within and beyond the institution. 54 Matrons' and attendants' wages were listed in a table of staff compensation in many reports; attendants consistently received the lowest wages of all employees at the institution. 55

Superintendents' lack of regard for everyday care work is, in some ways, consistent with the gendered nature of the work. Throughout the period 1915-1960, care work at Brandon was an overwhelmingly female occupation. Brandon's administrative hierarchy was distinctly gendered, with men holding nearly all positions of institutional authority. The only exceptions were traditionally female-dominated fields: the general matron who oversaw attendant care was invariably a woman, and as time went on, some women held professional positions as teachers, nurses, therapists, and social workers.

The fact that care work was gendered as feminine certainly contributed to the low wages that institutional caregivers received. At times, administrators grumbled that they should have to pay for such work at all, particularly in the case of inmates with significant intellectual disabilities, whom many administrators felt should be cared for by mothers, "maiden aunts," and other female kin as they had been prior to the era of institutionalization. 56 The institution paid unskilled male employees much better than unskilled female employees, on the grounds that men had to provide for dependent family members, while women were perceived as subordinate household earners, whether or not they cohabited with wage-earning men.

Care work also underwent a kind of gendered mystification that obscured its nature as wage labor and cast it as a "labor of love" instead. Howe had called attendant care "an elevated calling" whose best participants were motivated by "loving kindness." 57 In similarly idealized terms, Barr declared, "[T]he comfort and well-being of the entire community is insured by a capable and sympathetic house-mother." 58 George S. Bliss also idealized female attendants while questioning their executive skills. He wrote that a "cottage" housing "fifty to seventy children…is not so large but what a good woman, even though not exceptionally gifted as an executive, can know intimately every child under her care, and be a real mother to him." 59 In thus emphasizing care workers' "natural" maternal faculties, such writers downplayed the challenges of attendant care and the hardships it imposed on care givers and care recipients alike. 60

In fact, care work at Brandon was quite arduous. In the period 1915-1940, a single shift of dormitory matrons and attendants met both the day- and night-time needs of all inmates. Only in 1941 did the School add a nighttime shift of attendants, and that was intended less to relieve the burden on existing workers than to comply with wartime civil defense measures and prevent inmates' "undesirable nocturnal activities." 61 Prior to 1957, attendants received no formal training, and their daily responsibilities were staggering. One matron and one attendant had housekeeping and sanitation responsibilities for a building housing seventy inmates; they were responsible for daily maintenance of inmates' health, hygiene, and feeding; and they oversaw what little skills training "custodial" inmates received. 62 Under such circumstances, as Howe earlier described, "To get through the day somehow — anyhow — [became] the aim of life." 63 Writing in 1947, Superintendent Francis W. Kelly commented that Brandon care workers routinely suffered "from overwork and chronic stress." 64 As late as 1970, Superintendent Raymond Mulcahy lamented that dormitories housing "severely retarded" inmates were so short-staffed that care workers struggled to maintain minimum standards of sanitation; they certainly did not have time, even if they had the inclination, to meaningfully engage inmates as well. 65 Given the endemic problems of low pay, understaffing, and overwork, it is little wonder that inmates with significant intellectual disabilities were confined to their dormitory wards, day in and day out, with little social or environmental stimulation and no organized learning opportunities. 66 Until well into the 1950s, attendants caring for "custodial" inmates also lacked access to grievance procedures, staff meetings to coordinate consistency of care, and workplace safety guidelines. 67

Low wages, long hours, and dire working conditions often translated into high employee turnover. 68 Thus inmates had to contend with a steady inflow of unfamiliar and inexperienced care providers. The situation became acute in the early 1940s, when mobilization for war expanded the employment field for unskilled workers. Even after the war, turnover among ward personnel hovered around 50 percent throughout much of the 1950s and 60s. The 1940s and early 1950s appears to have marked a low point in the quality and consistency of attendant care at Brandon. These years saw a spike in "low-grade" deaths and an increase in runaways among "high grade" inmates.

One way that administrators coped with poor attendant care was to utilize inmates as unpaid care workers. Inmate care relations took a variety of forms. Some inmates fed others who could not self-feed; others helped with bathing, dressing, and grooming; others nursed the sick; and still others performed cooking, cleaning, laundry, and other forms of domestic service necessary to sustain dormitory life.

Administrators valued unpaid inmate care work for a number of reasons. First, it was cheap, and as a surveyor for the U.S. Public Health Service observed in 1943, "Brandon had more than once been praised for being cheaply run." 69 Second, inmates were captive workers, unlike paid attendants who were all too quick to leave the institution. Third, paid ward personnel were probably more inclined to remain at Brandon if they could delegate particularly unpleasant aspects of attendant care to unpaid inmate workers.

All inmates who could perform work did so at the Brandon Training School, including many "low-grade" inmates. Not only did unpaid inmate labor help to lower the institution's overhead costs; as Trent and Noll observe, it was also justified as a control measure. 70 As a welfare administrator in a neighboring state explained, "The feeble-minded…are essentially animal…. If we want to control animals we must work them hard — they go to bed, sleep well and are ready to do hard work to-morrow." 71 Work assignments at Brandon varied by inmates' ability and conformed to a strict gender division of labor. Male inmates were typically assigned to farm work or another masculine occupation, but a few also performed food service and custodial work in the male dormitories. As Superintendent Kelly noted in 1951, "the girls are trained in all rudiments of housekeeping" including laundry and seamstress work, kitchen work, and most importantly, attendant care. 72 In 1943, the U.S. Public Health Service surveyor observed, "Girls work in the ward buildings at all times under the eye of the matron." 73 During World War II, Brandon's labor shortage became acute; at the same time, the institution began admitting infants, toddlers, and aging "idiots" who had formerly been housed on poor farms. To deal with the resulting crisis of care, the administration added twenty beds to Dormitory D so that "lower-grade girls" could care for babies and "crippled bed cases." According to the 1942 biennial report, this led to "better care for bed patients and more efficient utilization of employees." 74 The reference to "lower-grade girls" is noteworthy here. It suggests that work assignments were determined not only by gender, but also by intellectual classification. "High grade" girls were not asked to perform care work for extremely "low-grade" inmates. Instead, they might work in a "high-grade" dormitory, or serve in the kitchen or laundry, or go out on "day placement" as domestics in Rutland area homes.

It is an open question how much conditions of care actually worsened during the 1940s, and how much, as Superintendent Francis Kelly wrote in 1951, "the public is becoming more aware of it." 75 As Raymond Mulcahy would later reflect, prior to World War II, "the school was situated in the nice rural community of Brandon, 'out of sight, out of mind.'" 76 While understaffing, lack of training, low pay, and resulting inadequacies of care had existed prior to the war, several factors contributed to the heightened visibility of these problems at mid-century.

The 1940s was a period of intensified public scrutiny of mental health institutions, and particularly for attendant care, both nationally and in Vermont. Changes in welfare administration were partly responsible for this shift. During the 1930s, New Deal welfare policy began to change how the federal government and the states cared for dependent citizens, including persons with disabilities. While Vermont lagged behind other states in adopting New Deal measures, state-level welfare practices began to change in the early 1940s. Social workers with Vermont's fledgling Child Welfare Services and Aid to Dependent Children programs accused the Brandon Training School of emphasizing eugenic control of "mentally defective" persons instead of offering humane care. Needy Vermonters who had seen family or community members committed to Brandon grew mistrustful of all state welfare officials, thus making the work of newer welfare agencies more challenging. 77

Also during the 1940s, a handful of influential exposés were published that highlighted the dire conditions at state mental hospitals and training schools; these included Albert Maisel's "Bedlam, 1946" and Albert Deutsch's The Shame of the States. 78 Such exposés drew, in part, on the reports of conscientious objectors registered with the U.S. Civilian Public Service who served as attendants in roughly a third of the nation's mental hospitals and training schools during the war. Several conscientious objectors documented the conditions they observed, emphasizing the hopelessness, neglect, and abuse of inmates that they encountered during their service. While no conscientious objectors were assigned to Brandon, the conditions they documented elsewhere — untrained, overworked, and underpaid attendants and resulting neglect and abuse of inmates — certainly pertained at Brandon as well. 79 Prompted by such national media reports, Governor Ernest Gibson cast a critical eye on the Brandon Training School, declaring it "a public disgrace" and calling for Medical Director Thorne's resignation in 1947. Echoing Deutsch's The Shame of the States, a writer in the Rutland Herald called Brandon "a blot on the State's conscience." 80

Finally, a national parents' movement emerged after World War II, bringing heightened attention to institutions like Brandon. 81 At Brandon, parents and other community members organized the Brandon Training School Association in 1954. 82 BTSA members worked directly with inmates, provided toys, clothing, and other materials, and met with administrators to advocate improvements in training, recreation, and care programs. Accustomed to operating with relative impunity, Brandon administrators now had to contend with outside interference.

While scrutiny of public mental institutions increased from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s, it is important to note that none of the institutions' critics proposed deinstitutionalization. Sharing administrators' conviction that persons with significant intellectual disabilities belonged in institutions, they emphasized better institutional management, physical plant improvements, and more humane inmate care. 83

As early as 1942, Thorne and Barnard reacted to heightened public criticism by publicly acknowledging that Vermonters were entitled to higher standard of care. 84 Ostensibly to achieve that higher standard, but really to justify an ambitious building program that primarily benefited the institution's "educable" inmates, Thorne arranged to have the United States Public Health Service conduct a survey of the School. Thorne, who held a typically low opinion of inmates with significant intellectual disabilities, believed that the institution needed an ambitious building program so that "high grade" inmates could be housed and trained at some distance from "low grade" inmates. Dr. Samuel W. Hamilton was appointed to make the survey, and he spent several days at the school in May 1943. Hamilton's 84-page was released in June 1943. Hamilton endorsed Thorne's ambitious building program intended to segregate "custodial" and "high-grade" inmates. Yet he also drew attention to the dire conditions of custodial inmate care. In a comparative analysis of training schools in various states, Hamilton pointed out that Brandon allocated proportionately less money for inmate maintenance (and more for administrative salaries) than the other institutions in the comparison group. He also pointed out that Brandon's weak administrative structure allowed abuse and neglect of inmates to go unchecked. In the conclusion of his report, he recommended better administrative oversight, higher pay and better working conditions for attendants, and a detailed staff training program as necessary to provide inmates with an adequate standard of care. 85 Unfortunately, apart from the building program to segregate "high" and "low grade" inmates, little was done to implement Hamilton's recommendations.

Available records of the Brandon Training School contain evidence of specific cases in which an attendant mistreated inmates in this period. Sometimes mistreatment was deliberate, as when an attendant struck inmates with a heavy brush each morning to awaken them. 86 At other times, mistreatment resulted from a lack of proper training and safety protocols, as when a poorly trained attendant dropped an inmate with multiple disabilities, who sustained a skull fracture and died. 87 In some cases, mistreatment can be inferred from biennial accounts of illnesses and deaths at the school. One can only imagine what it was like to be an inmate in a "low-grade" dormitory who required, but did not receive, feeding assistance during a biennium in which several inmates died of starvation, or who contracted bacillary dysentery due to poor sanitation and hygiene in the "custodial" wards.

Lack of supervision and a shortage of workers meant that attendants could mistreat and neglect inmates with impunity, particularly those inmates whose mobility and communication impairments prevented them from physically resisting or reporting their experiences. It certainly did not help that the institutional culture at Brandon devalued "low-grade" inmate lives. Cases of abuse were somewhat likelier to come to light when the inmates in question had milder intellectual disabilities. Inmates with milder intellectual disabilities, while also relatively powerless against a dehumanizing institutional infrastructure, were less restricted in their movements and could verbalize their abuse, though resistance usually took the form of running away. Certainly, mass runaways by "high-grade" inmates did occasionally prompt investigations of abuse, as in 1951 near the end of Francis Kelly's tenure as superintendent. 88

In 1950, Kelly wrote that, "without adequate personnel, no adequate care can be expected or produced." 89 Kelly was particularly discouraged by the high rate of employee turnover. 90 In a letter to a local leader of women's clubs, Kelly wrote, "Whether it has been the low wage scale… or the depressing nature of the work — we certainly have lacked efficient, adequate, interested employees." 91 Perhaps discouraged by the seeming impossibility of adequately staffing at the institution, Kelly resigned in 1951. The situation was indeed dire. After a visit to Brandon in 1952, the Vermont Board of Institutions observed that high employee turnover affected the dormitory department more than any other. The Board stated, "The type of work, the inability of some to sense the implications of their work, the lack of training and the rate of pay all combine to keep a constant stream of attendants flowing in and out of the dormitories." 92

Disregard for inmate care had characterized Brandon's administration since its inception. Throughout the period 1915-1952, superintendents' biennial reports made only infrequent and passing reference to work in the dormitories. This changed in 1954 when Francis Russell became Superintendent. While Russell was not necessarily more interested in institutional care work than his predecessors, he enlisted department heads, including the General Matron, to contribute to his biennial reports. Thus while earlier biennial reports had largely ignored attendant care, the 1956 report acknowledged that the matron's department was the largest at the institution with 72 employees. Matrons and attendants shouldered many responsibilities: "The training of the students in personal hygiene, manners, living with others, dressing themselves, speech, small duties, and working on special talents are a part of the daily life for dormitory personnel." 93 Since "custodial" inmates were excluded from the education program and largely confined to the wards, dormitory personnel were also responsible for furnishing what little diversion such inmates enjoyed. "[M]uch time is spent in directing dormitory life and dormitory recreation," the General Matron reported. 94

By the late 1950s, conditions had apparently improved somewhat for dormitory personnel at the Brandon Training School. A bi-weekly training program, in the works for over a decade, finally materialized in April 1957. 95 In May 1957, like all other state employees, Brandon's care workers received a 10% salary increase. Since care workers generally fell into the state's lowest salary grade, they also received a $100 cost of living adjustment. The same law reduced the workweek to 40 hours, which meant that dorm attendants, many of whom worked 48 hours a week, could receive overtime. Another change that apparently improved working conditions in the 1950s — but that had altogether different implications for inmate welfare — was the use of tranquilizers to control inmate behavior. As the superintendent wrote in 1958, "The use of the tranquilizing drugs continues and the results substantiate their cost… [T]he relief of tension in the dormitories makes the program invaluable." 96

"Low-grade" inmates bore the brunt of the new pharmacological regime. While Vermont was often in the rear-guard of national change, Brandon administrators declared themselves at the forefront in the use of Thorazine to ease institutional care. According to Dr. Seeley Estabrook, head of Brandon's Medical Department at the time, the institution "was the first of its kind to use Thorazine. Our program has been successful both in tranquilizing the disturbed and elevating the potentialities of those we felt could benefit under treatment…Many problems have been solved." 97 An examination of available psychiatric records in the 1950s reveals that the school used Thorazine to manage a range of problem cases, including those of active and voluble "low-grade" residents. While Thorazine was used to treat undesirable behavior in some "higher-grade" residents, it was also used to subdue "low-grade" patients. In the records from a psychiatric clinic conducted at the school in April 1955, Dr. George W. Brooks made the following entries:

P.M.: This is a deteriorated, disturbed, specific epileptic was seen at D. She is reported to be unmanageable much of the time. She should be given Thorazine in gradually increasing doses up to a maximum of 300 mg…

B.M.: This deteriorated, emaciated, disturbed idiot was seen briefly in dormitory D. She should be given Thorazine in gradually increasing doses until maximum 300 mg…

R.S.: This girl is reported to be much easier to manage… [H]er Thorazine should be continued … .

J.Z.: This boy is becoming somewhat more active again. He has been receiving only 150 mg of Thorazine. It should be increased to 200 mg daily… 98

Brooks' prescription of Thorazine for "P.M.," who was "reported to be unmanageable," and "J.Z.," who was "becoming somewhat more active," provides an ominous glimpse into the effects of pharmacological management on "low-grade" inmates' lives. In 1955, somnolence and inactivity were apparently considered desirable states for "disturbed epileptics" and "idiots" at the Brandon Training School. While such pharmacological restraint eased the burden on institutional caregivers, it did so at the expense of "low-grade" inmates. In this way, the advent of tranquilizing medication reflected a broader tension between the interests of "custodial" inmates and the interests of underpaid, overworked attendants in the period 1915-1960.

Even as pharmacological restraints eased attendants' burden, physical restraint and abuse continued at the Brandon Training School. Former inmates, now living with support in communities across Vermont, recall the dire mistreatment they endured at the hand of overworked, poorly supervised, and at times, downright malicious attendants. Physical restraints and solitary confinement continued to be routine disciplinary practices even after 1960. 99 Former Brandon inmate Joe Bushey recalled that the room used for solitary confinement had bars on the window and no heat. 100 Attendants also used straitjackets and bed sheets to restrain inmates. As Helen Fredericks recalled, "They put me in a special room and they put me in a straitjacket." Though decades had passed when she recalled the trauma in 2013, she added tearfully, "I hope it never happens to anybody, ever again." 101 Don Shover, another former inmate, described a male attendant who "used razor straps on me and slapped me across the face with them on my body and everything." 102

As these memories suggest, inmates endured terrible treatment at the hands of some attendants. But at least some inmates resisted, often suffering abuse and confinement as a result. Others tried to protect one another. As Ken LaFoe remembered of his time at Brandon, he would tell other, more vulnerable inmates, "I'm your big brother." 103 LaFoe's recollection reminds us that while Brandon inmates were subject to dependency relations that ranged from the merely inadequate to the outright hostile, they also forged supportive bonds with each other. It is to the politics of intimacy and friendship at the Brandon Training School that we now turn.

Permissible and Impermissible Forms of Intimacy

Lauren Berlant writes that "intimacy builds worlds; it creates spaces and usurps places meant for other kinds of relation." According to Berlant, "normal intimacy" privileges domestic space and the heterosexual couple form; to participate in such intimacy "signifies belonging to society in a deep and normal way." 104 Nayan Shah likewise states that "personhood and citizenship emanate from the 'domestic private' and coupled intimacy." 105 If, as these scholars argue, intimacy is a crucial dimension of personhood and a qualification for citizenship, then how might we understand the politics of intimacy at the Brandon Training School?

Brandon inmates had a complex relationship to "normal intimacy." They were wrested from the intimate bonds of family life because the families into which they were born were judged socially or sexually deviant or because their disabled presence was perceived as a threat to "normal" family ties. Wrested from families, they were placed in the institution where they lacked privacy, bodily autonomy, and outlets for intimacy and sexual expression. Drawing sexual attention to themselves increased inmates' vulnerability to repressive measures such as physical or pharmacological restraint. Moreover, to be sexual in any way was to draw attention, since Brandon inmates had no means of removing their sexual activities from public view. Throughout the period 1915-1960, inmates lived and slept in open wards containing as many as fifty-four cots spaced closely together. Bathing and toileting facilities lacked privacy partitions. For "low-grade" inmates who rarely left the wards, there was no boundary of public and private. Shut away in segregated dormitories day in and day out, they were excluded from public space, yet paradoxically, they had no privacy at all.

Further hindering "low-grade" inmates' opportunities for intimacy and sexual expression were administrators' and staff members' perceptions of them as repulsive and unfit for companionship, love, or physical intimacy. Brandon administrators also perceived inmates with significant intellectual disabilities as childlike and thus as properly lacking sexual appetites. Any sexual activity, even on the part of physically mature inmates, was interpreted as inappropriate to their imputed mental age. Since "custodial" inmates also lacked privacy, sexual activity took place in view of others and was thus doubly regarded as "pathological" or "perverted."

If inmates with significant intellectual disabilities lacked opportunities for acceptable sexual expression, they also lacked access to conviviality and the comforts of an intimate, home-like setting. At times, administrators paid lip service to the ideal of "providing a pleasant home" for "custodial" inmates. 106 And yet efforts to create home-like conditions were dubious. When Harrison Greenleaf briefly served as Acting Superintendent in 1951, he lamented the barren grounds that made the institution a cold and impersonal place. 107 And when Doris Fillioe became General Matron in 1954, she criticized the "heavy, utilitarian furniture" that contributed to the cold and impersonal atmosphere of the dorms. 108 Mealtimes in the dorms, which might have afforded opportunities for conviviality, were rushed affairs. Food was portioned out before inmates entered the dining room, and often it was already cold by the time inmates were seated. Inmates were encouraged to eat quickly so the clean-up process could begin. 109 Attendants, when they received any professional guidance at all, were cautioned against becoming overly attached to the inmates in their care. "Employees should not correspond with children, invite them into their homes, or exchange intimate confidences," a 1950s staff memo stated. 110 While such a policy might have discouraged favoritism and even helped prevent sexual abuse, it also foreclosed more innocuous and reciprocal forms of inmate-staff attachment.

In a context that denied inmates access to other forms of intimacy, the nurturant bonds that formed between unpaid inmate care workers and their dependent charges was sometimes touted as an antidote to the coldness and impersonality of institutional life. Exemplifying this perspective on unpaid inmate care work, a Massachusetts administrator wrote, "A newly admitted child is at once eagerly adopted by some one. The affection and solicitude shown for the comfort and welfare of 'my baby' are often quite touching. This responsibility helps wonderfully in keeping this uneasy class happy and contented." 111 That such idealized notions of unpaid inmate care operated at Brandon is evident in a 1964 Burlington Free Press article that describes the institutionalization of an eight-year-old girl named Kit. The author writes, "When Kit first entered Brandon, her condition deteriorated." But then "Kit found a 'mother' at Brandon, a 35-year-old patient with low mentality but a loving nature. She adopted Kit…." Kit's "adoption" by an older female inmate turned "what could be tragic" into a "new, happy life." 112 Thus idealized, unpaid inmate care work helped to frame the institution in a positive light, where happy lives were possible because of the affection that older female inmates lavished on younger, more dependent ones.

The idealized relationship between Kit and her "adopted mother" was clearly calculated to make the harsh fact of institutionalization more palatable to readers of the Burlington Free Press. And yet, denied other approved outlets for love and affection, some inmates likely valued opportunities to give or receive care and thus acquire a sense of emotional intimacy and belonging. One custodial inmate who performed a variety of jobs, including infant care, later recalled, "I liked the babies best." 113 That some inmate caregivers relished their caretaking roles is suggested by a mid-twentieth-century photograph of women and girls in one of Brandon's "custodial" dormitories. The photograph illustrates the hierarchical relations of care: the matron stands authoritatively in the foreground, with five white-clad paid attendants directly behind her. In the background stand the dorm's residents. Several adult women, whom administrators persisted in calling "girls," stand with their arms around younger inmates. In posing this way, older inmates claimed a mature identity as caregivers to younger, more dependent inmates [See photograph] 114 .

Untitled photograph [n.d.], Brandon Training School Photographs and Slides, 1915-1992. Vermont State Archives. Text decription: Photograph foregrounds matron and attendants, with approximately 70 female inmates behind them. Older inmates stand with arms around younger ones. Photo is taken in a gymnasium.

If female inmates were allowed to express maternal impulses in the form of unpaid care work, they were not permitted to care for their own sons or daughters, if they had any, nor were they permitted to express themselves sexually in any way. In at least one instance, when a mother and her infant child were admitted to Brandon at the same time, the baby's name was changed and its presence concealed from its mother to preclude mother-child bonding. 115 Permissible expressions of intimacy were thus narrowly defined, even as they could also be a source of pride, belonging, and emotional sustenance for some of the inmates who participated in them.

Brandon administrators regarded "low-grade" inmates as children in whom sexual activity was tantamount to perversion. A study of seventy-two adult inmates at Brandon, completed in 1925, established a correlation between "sex perversion" and "low grade" IQ. While only 14 percent of inmates classified as "morons, borderlines, and dullards" had histories of "sex perversion," the study found that 45 percent of inmates in the lowest intelligence grouping had such histories. 116

Similarly, in his 1943 survey of the Brandon Training School, Hamilton posited a connection between low IQ and sexual deviance. Specifically, he stressed the need to isolate Brandon's "purely custodial cases" from "those children who offer promise for successful rehabilitation" because the former group included "vegetative idiots" and "low-grade children" as well as older "delinquent defectives, sex perverts, and borderline psychotics." Hamilton argued that it was "not humane or justifiable" to expose the "younger, brighter children" to such "undesirable influences." Noting that it had been necessary to discharge "a group of unstable or perverted patients… [who] constituted a menace to…the younger children," Hamilton concluded, "Several of these discharges would not have been recommended if there had existed any facilities for segregating them in a group where they would harm only themselves." As a partial solution to the problem, Hamilton recommended "the construction of another dormitory for extremely low-grade children on an isolated location on the school campus."

Hamilton's discussion of the need to segregate "educable" and "custodial" patients conflated significant intellectual impairment with "perversion." He divided the population into two groups, of which he, like Thorne, clearly privileged the "educable" children of "borderline intelligence." He described the other group as composed of "vegetative idiots," "perverts," and "psychotics." It is striking that Hamilton prioritized building isolation facilities to protect "educable" inmates from sexual predators and other "low-grade" inmates in 1943, even as he acknowledged the concurrent problems of acute understaffing and inmate neglect. Instead of recommending the allocation of resources for better inmate care, Hamilton ultimately advised more stringent enforcement of discriminatory classifications that further undermined the health and welfare of "extremely low-grade" inmates at the school.

If isolating sexually suspect "low-grade" inmates was one means of regulating sexual behavior at Brandon, administrators also worked hard to "isolate male and female patients in order to miminize communication and fraternization." In 1946, the Board of Public Welfare proposed the creation of a separate girls' campus and a boys' campus on the grounds that such a plan "would segregate male from female patients and greatly facilitate administrative problems." 117 Similarly, a policy statement issued to staff in the 1950s reminded ward personnel that "At no time is any girl to be out of sight of a caretaker. Boys must never be sent to the girls' dormitory, unattended, for any purpose whatever, and vice versa." 118

Administrators also worked to regulate homosexual contact, particularly in the male dormitories. "It has been found desirable to maintain the male population slightly below rated capacity because of the greater practical difficulty in handling boys under overcrowded conditions," a 1942 report stated. It added: "Experience has proven that a large percentage of administrative and disciplinary difficulties [read: sexual difficulties] are caused by overcrowding and lack of privacy among the inmates." 119 In 1943, Hamilton reported, "Homosexuality… is actively discouraged by breaking up involved couples." And in terms that reinforced the conflation of low IQ with sexual deviancy, he added, "High grade boys report the lower grade boys who indulge obtrusively." 120

Allegations of homosexuality and other sexual misconduct stemmed from many quarters in the 1940s and 50s. "High-grade" inmates apparently accused more vulnerable "low-grade" inmates. Staff made allegations as well. Katherine Dolan, who managed the Rutland Colony House, repeatedly accused female residents whom she did not like of being lesbians; indeed, she went as far as to declare that most Brandon transfers to the Colony were lesbians. 121 A mimeographed code of conduct from the 1950s alludes to staff members' practice of accusing inmates of sexual misconduct: "It is unethical to discuss or gossip about intimate details in the lives of … inmates publicly," the code of conduct admonished. 122

A brief memoir, written in 1973 by P.G., a 15-year-old Brandon inmate, reveals some of the challenges that inmates confronted as they sought to reconcile their sexual desires with life inside the institution. 123 In some ways, P.G.'s experience differed from that of earlier Brandon inmates; in 1965, federal law mandated "semi-private" sleeping quarters for all inmates, thus prompting a gradual end to the practice of housing up to seventy inmates in a single room. Another change was the advent of a sex education program for "educable" inmates sometime after 1960. As a relatively "high grade" inmate, P.G. also enjoyed a wider range of social and academic opportunities than his "low-grade" counterparts. Yet in spite of these differences, P.G. still struggled to bring his desires for sex and intimacy into line with the sexual restraints imposed by the institution.

On the one hand, P.G.'s sex education impressed on him the ideal of conjugal-domestic intimacy, and he looked forward to experiencing that ideal first-hand. "Someday I will meet the girl I am looking for," he wrote. "I will take her to eat nice food. I will say let me talk to you in a nice way. She said O.K. I will kiss her on the lips. We go out a lot of times. We fall in love." After that, he hoped to marry "and have a baby boy and girl." P.G.'s sex education at Brandon taught him that sex should take place within marriage. "When you marry you can do sex," he informed the reader. "That is the best time for it." 124

On the other hand, P.G. expressed frustration because his chances of realizing his ideal of sex and romance while a resident of the institution were remote: "In Brandon Training School boys and girls can't live together," he observed. "Why can't we fall in love in B.T.S.?" 125

P.G. also had to reconcile the ideal of conjugal-domestic intimacy that he learned at Brandon with his passionate feelings for a fellow inmate. Later in the memoir, he writes: "I am in love with a boy. He loves me, I love him … I feel something in my body when I kiss the boy who I love." Soon after, he writes, "I am going to tell my mother I am in love with a boy." A staff member intervenes to repress P.G.'s budding relationship. "Mr. Kastner told me you can love your mother and father and said you can not love a boy outside your own family. And he said you can love a female." This disheartens P.G., who writes, "I am really in love with a male… I don't feel good in BTS." In a final reference to his thwarted relationship, P.G. writes: "In dorm H we got a new rule. It is no boy is to come in your room. But your roommate can come in your room. The rule came out because some worker found out that sex play was going on. We have to obey the rule." P.G.'s memoir, which covers only a few months of his life at Brandon, ended shortly thereafter. 126

While P.G. was a literate inmate who inhabited Brandon in an era of "semi-privacy," his struggles to find and sustain sexual intimacy speak to a much broader experience among BTS inmates whose opportunities for intimacy and for privacy of all kinds — physical, emotional, sexual, and otherwise — were denied, and whose sexual practices were labeled deviant.

If overt sexual activity was prohibited, some inmates did form lasting bonds of friendship and even couplehood. The lifelong attachment between Hazel Cook and Irene Poquette is a case in point. Hazel and Irene were both "custodial" inmates. Though Hazel was twenty-eight when twelve-year-old Irene arrived at Brandon in 1931, the two became fast friends over the course of their fifty-year co-residence at the institution, and they inhabited a wider network of female friendship. When Brandon began the process of deinstitutionalization in the early 1980s, Irene and Hazel were placed together in a community care home in Orwell, Vermont. When the care home operator died a few years later, Irene and Hazel moved together to another home in Middlebury. Both were devout Catholics, and they regularly accompanied one another to Mass at St. Mary's Catholic Church. When Hazel died in 1994, her obituary read, "Hazel is survived by her dearest friend, Irene Poquette of Middlebury." Reflecting back on more than sixty years of friendship during a 2001 interview, Irene stated, "Hazel and I were together a good many years." And more than once in the interview she commented, "I miss her." 127

If, as Berlant argues, intimacy is a crucial dimension of personhood, it was also something that Brandon inmates struggled against powerful odds to achieve, particularly those who were labeled "low-grade" and who could not, for most of the twentieth century, hope for a life beyond the institution. One authorized form of intimacy was maternal care, as exercised by unpaid female inmates on behalf of the institution. Same-sex friendships were permitted as long as they were not overtly sexual. Allegations of "sexual perversion" were a powerful means by which supervisory staff, attendants, and "high-grade" inmates could exert power over more vulnerable "low-grade" inmates. Heterosexual liaisons were also prohibited, and female residents in particular were seen as sexually promiscuous and in need of constant sexual repression. And yet, the limited evidence presented here also attests to Brandon inmates' tenacity in pursuing sex and intimacy that ranged from "undesirable nocturnal activities" to lifelong companionate bonds.

Conclusion