Americans with disabilities represent a significant proportion of the population. Despite their numbers and the economic hardships they face, disability is often excluded from general sociological studies of stratification and inequality. To address some of these omissions, this paper focuses on employment and earnings inequality by disability status in the United States since the enactment of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a policy that affects many Americans. After using Current Population Survey data from 1988-2014 to describe these continuing disparities, we review research that incorporates multiple theories to explain continuing gaps in employment and earnings by disability status. In addition to theories pointing to the so-called failures of the ADA, explanations also include general criticisms of the capitalist system and economic downturns, dependence on social welfare and disability benefits, the nature of work, and employer attitudes. We conclude with a call for additional research on disability and discrimination that helps to better situate disability within the American stratification system.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA, P.L. 101-336) was championed as the "emancipation proclamation" for people with disabilities by Senator Tom Harkin,1 and referred to as a "final proclamation that the disabled will never again be excluded" by Senator John McCain.2 Twenty-four years after the ADA became law, however, the employment rate among working age people with disabilities was at only 17 percent compared to 65 percent of people without disabilities (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015). Not surprisingly, during the ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA or the ADA Restoration Act; P.L. 110-325) hearings in the mid-2000s, many disability advocates alluded to the ADA's "failure" in addressing the continuing decline in the economic wellbeing of people with disabilities. These concerns lead researchers to the question: to what extent has the ADA influenced employment and earnings outcomes given a variety of individual, labor market, and political-institutional factors that have also shaped the economic wellbeing of persons with disabilities?

In attempting to answer this question, scholars have sought to determine whether or not the ADA improved employment and earnings outcomes among people with disabilities (Acemoglu and Angrist 2001; DeLeire 2000; Donahue et al. 2011; Kruse and Schur 2003; Maroto and Pettinicchio 2014a). Despite these efforts, researchers have been confronted with a host of theoretical and empirical problems due to the difficulties in disentangling the effects of policies from supply-and-demand explanations for labor market outcomes. Like many policies, the ADA did not specify ways in which to address individual and labor market complexities, nor did it describe how to go about changing attitudes and behaviors in the workplace, which could limit its effectiveness. However, isolating the effects of a single policy change over time is often quite complicated with multiple factors at play.

Although some researchers have long focused on these issues, disability still remains a disproportionately small part of the mainstream literature on structural inequality. Given the size of the population with disabilities in the United States and the hardships they face, it is particularly surprising that disability is often excluded from general sociological studies of stratification and inequality. In this paper, we draw from the wide-ranging literature on disability in order to situate this discussion in a broader framework of the sociology of stratification. Specifically, we discuss the relationship between antidiscrimination legislation like the ADA and labor market outcomes among people with disabilities. In light of its twenty-fifth anniversary, we explore existing policy-oriented explanations that suggest the ADA has failed to improve employment and earnings outcomes among people with disabilities, and we highlight the difficulties in assessing the role of the ADA vis-à-vis occupational characteristics, as well as employer and employee preferences. By combining policy perspectives with individual and structural explanations for inequality, we demonstrate how disability acts as a status that shapes the unequal distribution of resources, similar to race and gender.

We begin by describing pre- and post-ADA trends in employment and earnings outcomes among persons with disabilities. We then provide a brief historical discussion of American disability rights legislation in order to situate the two primary explanations about why the ADA may have failed to improve the economic wellbeing of persons with disabilities. After addressing the complexities in establishing whether policies like the ADA influence employment and earnings outcomes, we turn to other attitudinal, institutional, and structural explanations for growing inequality among people with disabilities. In our conclusion, we reiterate the importance of linking policy approaches and supply-and-demand explanations for continued disparities between people with and without disabilities and integrate our contribution within the broader literature on stratification and inequality in the United States.

THE ECONOMIC WELLBEING OF PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

In the United States, the employment, earnings, and subsequent economic wellbeing of persons with disabilities have generally declined since the 1970s. This occurred even after the enactment of the Rehabilitation Act in 1973, which provided antidiscrimination provisions regarding employment in the public sector and agencies receiving federal government contracts. In fact, the only time people with disabilities appeared to improve their economic situation was in the 1960s when the gap between workers with and without disabilities narrowed. According to Haveman and Wolfe (1990) real earnings for persons with disabilities rose between 1962 and the mid-70s, but began to plummet after 1976. During that period, real earnings among people with disabilities decreased along with disability transfer payments, leading to an overall decline in economic wellbeing. Thus, employment rates began to decline well before the ADA was enacted, and continued to decline throughout much of the 1990s, despite the economic expansion during this period (Burkhauser et al. 2001, 2003, 2006; Houtenville and Adler 2001; Unger 2002).3

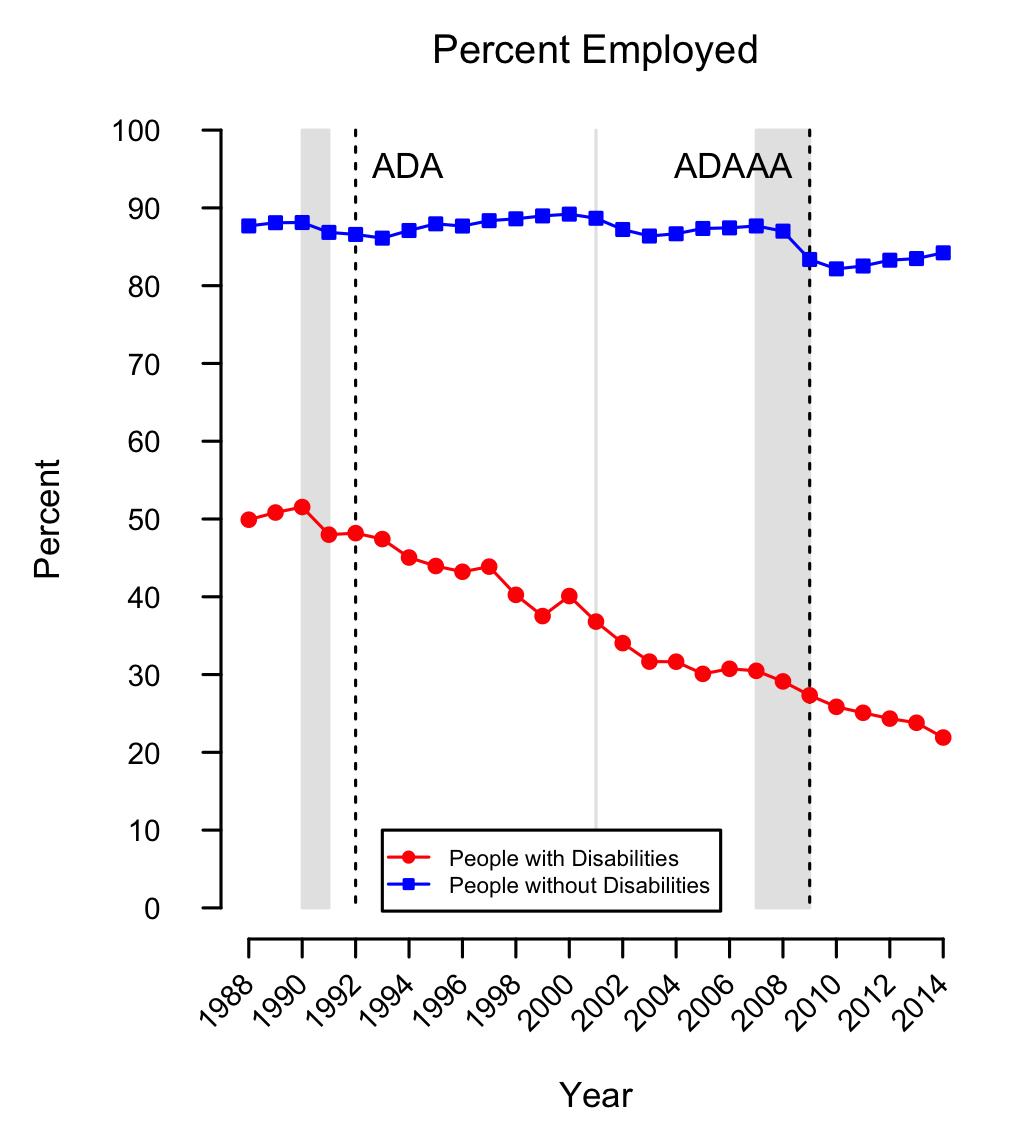

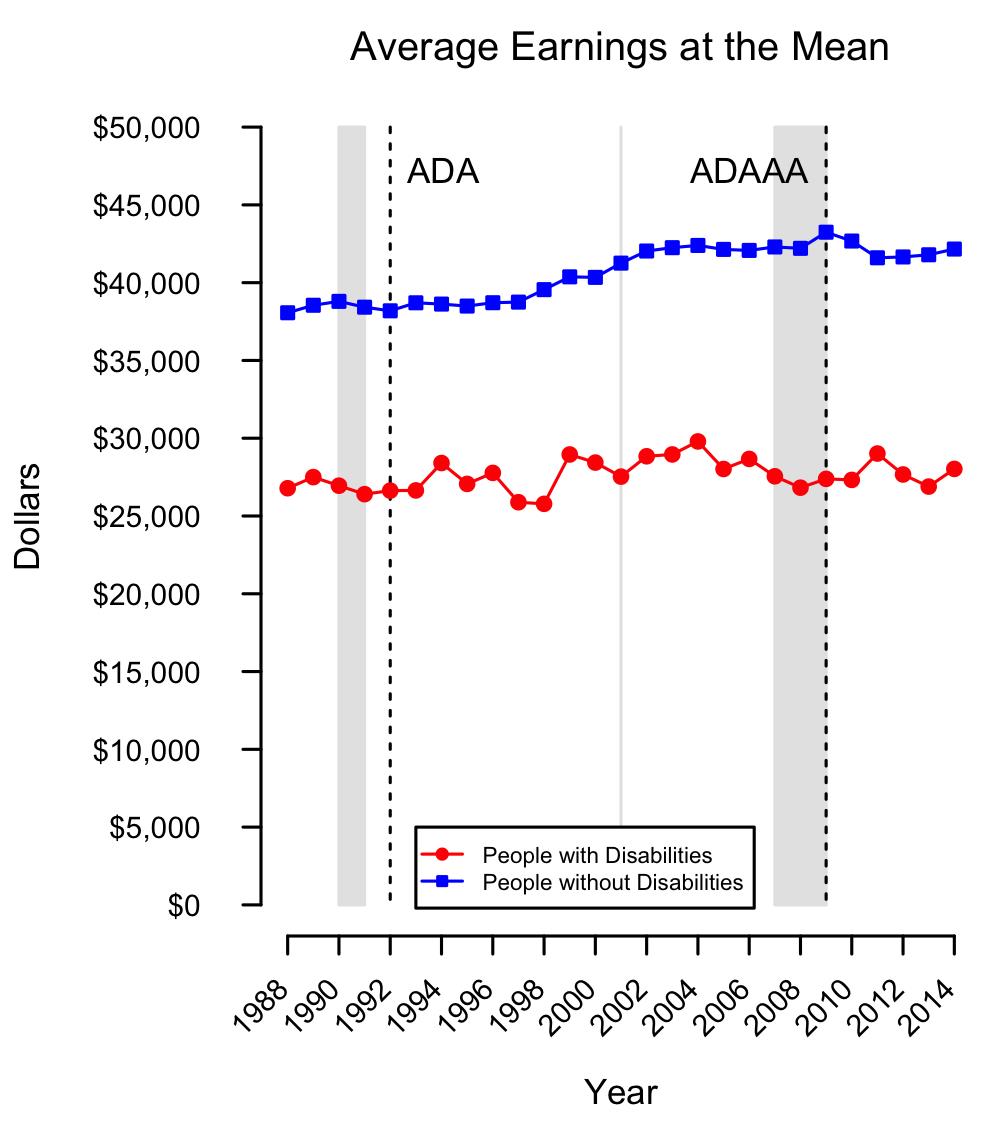

To supplement these findings, Figures 1 and 2 plot trends in employment and earnings for working-age people with disabilities from 1988 through 2014 using Current Population Survey (CPS) data.4 Figure 1 shows the employment rate for people with and without reported work-limiting disabilities and Figure 2 shows the average earnings for these two groups over time. Both plots control for individual characteristics, human capital, and state variation.5

SOURCE: 1988-2014 CPS data for working-age people (25-61 years of age) with and without work-limiting disabilities.

NOTES: Estimates show the average percent employed based upon disability status. Estimates control for age, education, marital status, the presence of children, sex, race, the receipt of government assistance, and state of residence. Dotted lines mark the passages of the ADA and ADAAA. Shaded areas denote recessionary periods in the United States.

View extended text description of Figure 1

SOURCE: 1988-2014 CPS data for employed working-age people (25-61 years of age) with and without work-limiting disabilities.

NOTES: Estimates show the average earnings in 2014 dollars based upon disability status. Estimates control for age, education, marital status, the presence of children, working hours, occupation, sex, race, the receipt of government assistance, and state of residence. Dotted lines mark the passages of the ADA and ADAAA. Shaded areas denote recessionary periods in the United States.

View extended text description of Figure 2

As Figure 1 indicates, the rate of employment for people with work-limiting disabilities has declined over the past twenty-five years, even after accounting for variation in education, human capital, and the receipt of government assistance. In 1988, the employment rate for the average person with disabilities was 50 percent. By 2014, this rate declined to 22 percent.6 Employed people with disabilities, however, saw fewer declines in earnings over this time period (Figure 2). In terms of average earnings for workers, people with any work limitation earned about $12,000-14,000 less than the rest of the population in 1988 and in 2014, after accounting for individual and state control variables. Absolute earnings for people with disabilities increased by approximately $1,200 between 1988 and 2014, but the relative disparities did not improve. Thus, net of other characteristics, employment disparities for people with disabilities have grown over this period, while earnings gaps have remained relatively stable.

To add to the complexity, labor market outcomes for people with disabilities vary according to individual, occupational, and structural characteristics, as well as the specific type of disability. For instance, studies have consistently shown that people with mental or cognitive disabilities have worse employment outcomes than individuals with physical disabilities, regardless of occupation (Baldwin and Johnson 1994; Jones 2008, 2011; Maroto and Pettinicchio 2014b; Wilkins 2003). Across studies, earnings gaps were largest for people with work limitations, cognitive difficulties, and independent-living barriers, but people with hearing difficulties experienced the smallest earnings gaps (Baldwin and Johnson 1994; Burkhauser et al. 2002; DeLeire 1995; Lewis and Allee 1992; Unger 2002).

Building on this research, Tables 1 and 2 present estimated employment rates and earnings for working-age adults with different types of disabilities, other minority groups, and the total population using CPS data from 2014. For comparison purposes we present these estimates with and without sets of control variables.

| No Controls[1] | Controls[2] | |

| Disability Status | ||

| Any Limitation | 23.78 | 36.188 |

| Any Work Limitation | 13.49 | 23.05 |

| Hearing Difficulty | 49.98 | 62.98 |

| Vision Difficulty | 31.36 | 50.66 |

| Cognitive Difficulty | 17.24 | 31.39 |

| Ambulatory Difficulty | 16.00 | 28.88 |

| Mobility Difficulty | 9.59 | 18.32 |

| Self-care Difficulty | 8.85 | 18.47 |

| Other Groups | ||

| Female | 68.26 | 74.27 |

| Black | 67.18 | 79.81 |

| Hispanic | 71.64 | 82.45 |

| Total Population | 74.11 | 81.19 |

| SOURCES: CPS 2014 March Supplement, N= 67,912 | ||

| NOTES: Data are for working-age adults (25-61 years of

age) [1] All estimates include population weights, as provided by the survey. [2] Estimates control for age, education, marital status, presence of children in the household, sex, race, the receipt of government assistance, and state of residence. Controls are mean centered for 2014 to provide estimates of average employment rates. |

||

| No Controls[1] | Controls[2] | |||

| Estimate | Percent Difference | Estimate at Mean[3] | Percent Difference | |

| Disability Status | ||||

| Any Limitation | 23,873 | -68.43 | 33,047 | -25.62 |

| Any Work Limitation | 16,428 | -104.82 | 29,109 | -38.05 |

| Hearing Difficulty | 38,421 | -18.12 | 38,247 | -10.01 |

| Vision Difficulty | 28,122 | -49.40 | 34,038 | -21.70 |

| Cognitive Difficulty | 15,651 | -108.58 | 26,520 | -47.00 |

| Ambulatory Difficulty | 26,037 | -57.54 | 37,403 | -12.30 |

| Mobility Difficulty | 16,530 | -102.73 | 31,125 | -30.71 |

| Self-care Difficulty | 19,683 | -85.04 | 33,388 | -23.58 |

| Other Groups | ||||

| Female | 37,912 | -34.95 | 37,354 | -23.93 |

| Black | 37,436 | -22.84 | 39,357 | -7.94 |

| Hispanic | 35,014 | -32.87 | 39,775 | -7.51 |

| Total Population | 45,848 | 42,247 | ||

| SOURCES: CPS 2014 March Supplement, N = 50,380 | ||||

| NOTES: Data are for employed working-age adults (25-61

years) with earnings [1] All estimates include population weights, as provided by the survey. [2] Estimates and percent differences come from models predicted logged earnings. Models control for age, education, marital status, presence of children in the household, sex, race, usual hours of work per week, major occupation, government employment, self-employment, the receipt of government assistance, and state of residence. [3] All controls are held at their means. To account for error when transforming values to dollars, values are multiplied by the mean of the exponentiated residuals. |

||||

In 2014, about 74 percent of the population was employed. This rate rose to 81 percent after accounting for control variables. Even after factoring in differences in education and human capital, employment for people with different disabilities did not reach these levels. Across all types of disabilities, 36 percent of people were employed in 2014. Employment rates were highest for people with sensory difficulties (51 to 63 percent), but lowest for those that indicated self-care or mobility difficulties (18 to 19 percent). However, these rates still lagged behind the rate for the total population, as well as rates for women, blacks, and Hispanics.

As seen in Table 2, there were fewer differences in earnings by disability type for employed workers in 2014, but disparities that exceeded those of other minority groups were still present, even after for accounting for key explanations of labor market inequality. People with any limitation earned approximately 26 percent less than the rest of the population. This amounts to a $9,000 difference in earnings at the mean. Workers with cognitive, mobility, and self-care difficulties experienced gaps upwards of $10,000 at the mean, but employed workers with hearing and ambulatory difficulties saw the smallest earnings deficits. In this case, it appears as though the largest disparities for people with certain disabilities occur at the employment stage, although earnings gaps were still present.

In addition to this variation by disability type, disability intersects with a person's race and ethnicity, gender, age, and education level to differentially affect labor market outcomes (BLS 2015; Bradsher 1996; Kessler Foundation/NOD 2010). The differences in the estimates with and without control variables in Tables 1 and 2 reinforce this point, as do analyses of trends over time. For example, even though white men with disabilities showed signs of recovery by the mid-80s, nonwhite men with disabilities did not. By the mid-80s, family income for nonwhite men with disabilities was less than 50 percent of the income of white disabled men (Haveman and Wolfe 1990).

Women, blacks, and Hispanics with disabilities often face additional obstacles due to the intersection of multiple disadvantaged statuses (Hernández 2006; Shaw, Chan, and McMahon 2012). Schur (2004) described women with disabilities as facing a "double handicap" because of their lower employment levels and higher poverty rates than both women without disabilities and men with disabilities. Randolph and Anderson (2004) found similar disadvantages for women using Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data. However, due to the employment of men and women in different occupations, physical disabilities tend to be more limiting in terms of wage penalties for men (Baldwin, Zeager, and Flacco 1994).

Overall, people with disabilities still experience large employment and earnings disadvantages that vary by disability type and other individual characteristics. Despite the ADA's goals, there has been little improvement in economic outcomes for people with disabilities since its passage. These trends have continued in part because the ADA neither conceptually nor practically dealt with specific individual and structural-level considerations regarding the integration of individuals with disabilities in the labor market. Yet, it is impossible to understand how the ADA influenced the economic wellbeing of individuals with disabilities without accounting for the broader factors that also determine employment and earnings outcomes. Although the ADA may not have improved the wellbeing of persons with disabilities, it does not necessarily mean that it diminished it, given evidence that employment and earnings were already in decline before the ADA was introduced. In addition to individual characteristics and structural aspects, multiple political-institutional factors have also influenced the ADA's ability to shape attitudes and behaviors about people with disabilities and improve their employment and earnings outcomes.

THE LEGACY OF AMERICAN DISABILITY ANTIDISCRIMINATION LEGISLATION

Although disability has always had a place on the American policy agenda, and Congress has enacted hundreds of laws that directly affect persons with disabilities, the majority of political discourse and legislation dealt with social and health service provisions, not rights or discrimination (Pettinicchio 2013). This has reflected the dominant paradigm or worldview that people with disabilities are either clients or patients in need of services. However, this trend began to change in 1971 when Senator Hubert Humphrey and Representative Charles Vanik introduced an amendment to the Civil Rights Act that would have included disability as grounds for discrimination. Although this bill failed, the antidiscrimination language eventually made its way into the 1973 Rehabilitation Act. The law established an antidiscrimination and affirmative action approach to disability employment in public sector firms that included any entity receiving federal funds or contracts. Specifically, Section 504, which borrowed language from the Humphrey-Vanik bill, stated that "No otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States shall, solely by reason of his handicap, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

Importantly, the Rehabilitation Act did not appear to be driven by changes in public preferences or social movement mobilization. The Rehabilitation Act was largely the product of institutional entrepreneurship (Altman and Barnartt 1993; Pettinicchio 2012, 2013; Scotch 2001). Nonetheless, it marked a pivotal turn in the disability rights story as it facilitated the growth of the nascent disability rights movement. It also shaped political discourse around disability rights, created political opportunities, and produced a policy framework for what would become the ADA.

In the mid-to-late 1980s, disability movement leaders, as well as other institutional entrepreneurs in the government, began to consider new legislation that would extend many of the provisions in the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 to the private sector (excluding any affirmative action measures). After multiple drafts, Congress passed a considerably watered down version into law as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. Under certain circumstances, the ADA prohibited discrimination on the basis of disability, defined as "a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits a major life activity" (Blanck et al. 2007; Burris and Moss 2007-2008).

A major hurdle was convincing the Republican administration to pursue the legislation (Shapiro 1993). According to Pelka (2012), Justin Dart, a Republican, disability activist, and person with a disability, was quite persuasive in pitching the ADA as an important part of the Republican platform. Others have suggested that the ADA fit well with President Bush's "kinder and gentler America" (Barnard 1990). At the same time, it was congruent with the conservative mantra that work of any kind, even if low paying and potentially more counterproductive to economic wellbeing than unemployment, is work nonetheless. That is, work of any kind is better than unemployment. Thus, the ADA has been framed as a mandate for "getting the disabled off welfare" (Stein 2003).

Early on, it was clear that the role of the ADA in improving labor market outcomes for people with disabilities was uncertain. Because Title I of the ADA applies to the private sector, the business community made its anxieties known before and after the passage of the legislation. Opponents argued that the ADA increased the costs of hiring persons with disabilities. Others argued that the ADA had already been watered down before it was even passed into law (partly as a result of pressures from employers and businesses). Legislators attempted to quell fears that "mandating" reasonable accommodations would increase the costs of hiring and retaining disabled employees, and they worked to assuage worries that the ADA would cause an influx of lawsuits against employers (O'Brien 2001). In addition, the courts have ruled fairly conservatively when it comes to the application of the ADA. As a result, many saw the ADA as having failed in improving employment and earnings outcomes. With the ADA Restoration Act in the mid-2000s, disability rights advocates sought to investigate what they saw as important political and institutional shortcomings associated with the ADA.

Despite the assertion that the ADA failed to improve the economic wellbeing of persons with disabilities, determining whether the ADA achieved its goals has proven difficult for scholars. DeLeire's (2000) study, which used data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), claimed that the ADA led to a decreasing employment rate for disabled relative to nondisabled men. Acemoglu and Angrist (2001) presented similar results using 1988-1997 March Current Population Survey (CPS) data. However, using SIPP data, Kruse and Schur (2003) found that employment did decline, but mainly in the years immediately following the ADA, and they actually observed an increase in employment with an alternate measure. Thus, while some studies claim that the ADA decreased disability employment, the findings on this matter are inconsistent. Although the ADA may not have reversed the trend, it is also not clear whether it contributed to it, as its effectiveness depended on enforcement agencies and interpretation by the courts (see Maroto and Pettinicchio 2014a).

Did the ADA Fail? Policy Perspectives

Two main policy explanations have been offered as a way to clarify the relationship between the ADA and employment rates among people with disabilities. The "unintended harm" thesis claims that the ADA unintentionally hurt employment by increasing the costs of employing persons with disabilities. However, the "judicial resistance" thesis claims that the ADA amounted to empty, under-enforced legislation that was undermined by the courts. The former argument suggests that the ADA negatively affected employers' perceptions of the costs of hiring persons with disabilities, while the latter implies that since the ADA had no bite, it should have had little effect on employers' perception of costs.

Both theories seek to explain the ways in which attitudes and behavior change following policy interventions but make different assumptions about employers' perceptions of people with disabilities. The unintended harm thesis claims that the ADA hurt employment by increasing costs, but it does not contend that employers would have hired people with disabilities otherwise. The judicial resistance argument assumes that employers will not hire people with disabilities because of false perceptions of costs and prejudice towards people with disabilities. Interestingly, this is also the same assumption made about employer attitudes and behaviors regarding minorities and women (Arrow 1998; Dovidio and Hebl 2005; Moss and Tilly 2001; Maroto and Pettinicchio 2014a).

Unintended Harm

According to the unintended harm thesis, the ADA created disincentives for hiring persons with disabilities due to employer perceptions about the costliness of providing reasonable accommodations. Prior to the enactment of the ADA, legislators and members of the business community not only worried that there would be an influx of disabled individuals seeking employment, but they also feared that existing employees would seek potentially costly redress under the ADA (DeLeire 1995). When data on complaints filed through the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) were first made public, employers were concerned that the vast majority of persons filing complaints were not those with typical disabilities (e.g., mobility, vision, and hearing impairments only represented 17 percent of EEOC complaints) but rather, those with backaches and heart problems — conditions that are prevalent in the population.

Reports suggest that following the ADA, members of the business community also presented mounting concerns about losing autonomy in the workplace due to increased regulation. Employers worried that they would have to hire unqualified workers, reimburse expensive medical bills, and pay other increased costs associated with hiring persons with disabilities (see Lee 2003). Employers could avoid these costs, however, by not hiring persons with disabilities. According to Acemoglu and Angrist (2001), some employers might choose to fire an employee with a disability because they believed the costs of litigation to be less costly than accommodation, and others might refrain from hiring people with disabilities so as to avoid costs of accommodation and litigation altogether.

Many of these arguments resurfaced during the ADA Restoration Act hearings as well. Congressional members expressed concerns about potential unintended harm connected to the ADA and the ADAAA. For instance, Representative McKeon stated that, "… concerns have been raised about the unintended consequences that would result from an expansion of the law. As this committee well knows, even the best of legislative intentions often produce harmful unintended consequences" (US House. Committee on Education and Labor 2008).

Judicial Resistance

The judicial resistance argument revolves around the role of the courts in effectively undermining already watered-down legislation. The ADA granted employers wide discretion in making decisions about disability status, as well as hiring, firing, and accommodation. For example, employers could choose to evaluate an employee's disability in its mitigated state and make the case that the employee did not qualify under the ADA, or they could evaluate the employee's disability in an unmitigated state and argue that the individual's disability was too severe to be reasonably accommodated. Thus, if they could not get the case thrown out based on standing, employers could then argue that accommodations were too unreasonable.

Proponents of judicial resistance argue that the courts have ruled conservatively on disability cases largely favoring employer freedom and autonomy. The courts have generally upheld the notion that the ADA must not overly regulate, limit autonomy, or remove control of the employer over the workplace (O'Brien 2001; Stein 2003). Despite applause on the part of proponents of the ADA — that the ADA is the most significant legislation passed since the Civil Rights Act — the courts have seen reasonable accommodation not as an extension of civil rights, but as outside conventions that govern work. The courts protected employers not by ruling in favor of employers on reasonable accommodation issues, but by ruling that a majority of people with disabilities was not actually covered by the law. As O'Brien (2001, 168) claimed, "the Court insisted that the employers needed protection from being overrun by all the disabled people who were wrongly seeking legal redress." Indeed, the final draft of the ADA did not assume that employment practices excluded persons with disabilities, nor did it recognize original statements describing the environment of the workplace as disabling. The general counsel for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce said that when it came to the ADA, courts "went with the business community right down the line."

In turn, interpretations of the law have created major hurdles for disabled plaintiffs and, in many ways, rendered the ADA ineffective in changing employer attitudes and practices. For instance, unlike women and racial minorities, persons filing under the ADA must prove that they have a disabling condition and that their disability impairs performance in a "major life activity" (Colker and Milani 2010). Following the 1999 Sutton v. United Airlines case (527 U.S. 471) and until the ADA Restoration Act in 2008, disabled plaintiffs had to show that their disability precluded them from an entire class of jobs, not just their own jobs. Additionally, plaintiffs could not file under the ADA if they mitigated their disabilities with medical supply, technology, or medication (Lee 2003; see Toyota v. Williams, 534 U.S. 184). Not surprisingly, leaders of disability groups were highly critical of the situation. Critics have referred to the law as "illogical," "hyper-technical," and a "Catch-22" (O'Brien 2001).

Courts have seldom ruled against employers' discretion, and in the few cases that have been decided on reasonable accommodation, courts have sided with employers. Eighty-six percent of cases brought to the EEOC early on were dropped (DeLeire 1995) and most cases have not make it beyond determining whether a person is qualified under the law, leaving very little judicial precedence for dealing with reasonable accommodation (Lee 2003). Employment discrimination plaintiffs have generally fared poorly in federal district courts, although some disability plaintiffs have benefited by settling out of court (Moss et al. 2005) meaning that most cases do not make it beyond district court. For example, between 1992 and 1998, disabled plaintiffs prevailed in only 8 percent of cases (Russell 2002; Stein 2003). At a national level, court data from the Supreme Court Database suggests that the Supreme Court often overturns liberal lower court decisions in favor of employers (Maroto and Pettinicchio 2014a). The court case results imply that judicial decisions following the ADA should have assuaged employer fears, not amplified them.

Overall, the unintended harm and judicial resistance perspectives raise questions about whether the ADA decreased employment or simply did not help to increase employment. Importantly, studies comparing the effects of ADA-like legislation across states have not lent any further credence to the unintended harm argument. For example, Beegle and Stock (2003) found that individuals with disabilities had higher rates of labor force participation in states that enacted ADA-like laws prior to 1980 compared to other states, but they did not find an effect for state laws with a reasonable accommodation provision, which implies a stalemate regarding the role of antidiscrimination legislation in improving employment outcomes. More recent research that expanded the number of years, however, showed that state-laws that included reasonable accommodation provided added benefits to people with disabilities (Maroto and Pettinicchio 2014a). Existing evidence suggests that these laws have not served to provide any added gain for persons with disabilities, which is different than saying that laws might actually create unintentional harm. Importantly, interpretation and enforcement of the legislation intervenes in shaping the ability of policy to affect labor market outcomes.

BEYOND POLICY: SUPPLY-AND-DEMAND FACTORS EXPLAINING EMPLOYMENT OUTCOMES

People with disabilities are less likely to be employed and earn less today than similar people with disabilities did in the 1980s and 1990s, but questions as to whether the ADA caused these declines remain. Work seeking to uncover the role of the ADA in shaping these outcomes is inconclusive. This is further complicated because various supply-and-demand side considerations, which also shape labor market outcomes, are often left out of policy analyses. The individual-level characteristics important to supply-side explanations and broader policy explanations that we discussed earlier in the paper shape employment and earnings, but demand-side factors like employer attitudes and occupational structures also influence these outcomes. In discussing these factors, we also consider the role of benefits and government assistance and the broader role of employment rights in capitalist societies, both of which may have important effects on economic outcomes for people with disabilities.

Changing Attitudes and Behavior

Beyond the specific policy perspectives discussed earlier, demand-side aspects related to employer attitudes and the potential for discrimination also affect labor market outcomes for people with disabilities. Disability has been an easy way to keep people unemployed as it preys on widely held beliefs that people with disabilities are feeble, weak, and incompetent (Russell 2002). Neufeldt (1995) argued that, historically, disability was always negatively portrayed, until it became medicalized into a deficit or condition. Individuals with disabilities are often seen as helpless, potentially causing "aesthetic anxiety" and making others feel awkward (Robert and Harlan 2006). As a result, this long history of stereotypes and negative portrayals connects to prejudices about whether people with disabilities can be productive employees (Schwochau and Blanck 2000; Unger 2002).

Although policies like the ADA ban certain behavior by employers, they do not necessarily improve employer attitudes about minority groups. As Reskin (2001) claimed, antidiscrimination legislation assumes that employer behavior would have to change as public perceptions and attitudes become increasingly disapproving of discriminatory behavior, but this is not always the case. According to statistical discrimination, queuing, and status characteristics theories (see Arrow 1973, 1998; Reskin and Roos 1990; Ridgeway 1991, 1997), employers may continue to hold negative attitudes about people with disabilities, and they may equate disability with lower productivity and higher costs for making accommodations. These generalizations then affect their willingness to hire and promote people with disabilities.

Attitudes can act as an obstacle in the workplace and may even affect views about the costs of accommodation (see Stein 2003). However, studies suggest a complex relationship between attitudes and hiring practices, particularly due to the social desirability bias that exists in surveying employers about attitudes. For instance, Wilgosh and Skaret (1987) found that negative attitudes inhibited employment and advancement in some instances, but they also noted a discrepancy between employers' willingness to hire applicants with disabilities and their actual hiring practices. As a means to overcome social desirability bias in employer comments about people with disabilities, Kaye, Jans, and Jones (2011) asked employers to indicate what other employers generally see as problematic about hiring people with disabilities. Respondents revealed negative attitudes about disability and concerns over the cost of accommodating people with disabilities (Kaye et al. 2011). Overall, employers are more likely to hire a person with a disability if they already have hired someone with a similar disability, suggesting that prior experience can dispel the myths about costs and the inefficiency of disabled workers (Komp 2006; Unger 2002).

Discrimination does not always stem from employers' intentional actions based on prejudicial or negative attitudes. It often evolves out of employers' unconscious biases about certain groups (Greenwald and Krieger 2006; Tajfel 1982). The Implicit Association Test (IAT) provides researchers with ways to measure unconscious attitudes toward social characteristics, including disability (Greenwald and Krieger 2006). The IAT evaluates the time it takes for people to match certain positive and negative concepts. In studies incorporating IAT measures of disability attitudes, respondents indicated implicit preference for people without disabilities and tended to associate disability with childlike characteristics (Robey, Beckley, and Kirschner 2006; Vaughn, Thomas, and Doyle 2011).

The stereotype content model, supported by many social psychologists, offers an additional way to measure attitudes about disability (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007; Fiske et al. 2002). In studies using this model, researchers asked respondents to rank groups based upon axes of warmth and competence, two key dimensions of interpersonal and intergroup interactions. People with disabilities tend to fall within the "pitied" quadrant of the stereotype content model, where individuals are characterized as incompetent and ineffective, but generally likeable and nonthreatening (Fiske et al. 2002).7

Overall, conscious and unconscious negative attitudes about disability likely affect employers' willingness to hire people with disabilities, particularly because of assumptions that people with disabilities will be less productive workers. When this occurs and when employers rely on limited information about average group differences in productivity and reliability, they engage in statistical discrimination (Arrow 1998; Holzer 1996; Lundberg and Startz, 1983; Moss and Tilly 2001). However, if the beliefs about groups reflect the actual distributions of characteristics across groups, decision makers are assumed to be economically rational, which is often the case when the issue is a disability that could affect productivity. As a result, certain types of discrimination against people with disabilities may be seen as warranted.

Studies of disability discrimination are more limited than those of race and gender discrimination, but tend to rely on similar methods, including wage decomposition models, employee surveys, and EEOC charge data. Using 1984 SIPP data, Baldwin and Johnson (1994) found that for men with disabilities, discrimination most likely occurred due to below average returns for experience, but, in the case of men with more severe disabilities and handicaps, it likely stemmed from employer prejudice. DeLeire (2001) also found evidence of wage discrimination for men with disabilities in his analysis of SIPP data from 1984 and 1993, although productivity differences explained a larger part of the wage gap.

Other researchers have investigated employee perceptions of discrimination using surveys. In a study of 119 employees with disabilities matched to their employers, one third of employees reported experiencing discrimination at work, but perceptions of discrimination were more prevalent among workers with less education and among racial minorities (Balsar 1996). The two most common types of perceived discrimination in Balsar's (1996) study were related to reasonable accommodation and promotion decisions. Additionally, employees with disabilities have described experiences of marginalization, fictionalization, and harassment in large, bureaucratic organizations that managers tended to tolerate and even encourage at times (Baldwin and Johnson 2006; Robert and Harlan 2006).

The courts (citing the 1987 School Board of Nassau County v. Arline case, 480 U.S. 273) to some extent have acknowledged normative and attitudinal barriers in the workplace, and Congress sought, in part, to address attitudes and norms surrounding disability with the ADA (Lee 2003). Indeed, many scholars agree that changing norms and attitudes in the workplace was an important objective of the ADA, and activists saw it as such (Acemoglu and Angrist 2001). However, multiple avenues of research indicate the persistence of negative attitudes about disability that can affect employer behavior. Both the unintended harm and judicial resistance arguments rest on the premise that policies shape attitudes and behaviors. Nevertheless, empirical findings have been largely inconclusive about the role of the antidiscrimination legislation like the ADA in labor market inequality, especially when it comes to understanding how the law shaped employer attitudes and practices.

Benefits and Welfare Availability

Beyond the effects of employer attitudes, the presence of other income sources can reduce a person's need to work. Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and other forms of public in-kind assistance are meant to alleviate poverty among persons with disabilities who face high rates of material hardship (She and Livermore 2007), but the relationship between SSI, employment, and rights-based legislation, like the ADA, is complex. It is not clear whether SSI payments, and other benefit policies, preclude individuals from looking for work or simply supplement earnings gaps (Haveman and Wolfe 2000). In investigating transfer payments over time, Haveman and Wolfe (1990) found that public disability transfer payments helped cushion the decline in earnings among people with disabilities. However, with welfare retrenchment in the 1980s, transfer payments could not stop the decline in economic wellbeing of people with disabilities. Because increases in the amount of payments ended by 1974 and transfer payments seemed to increase in tandem with disability employment, researchers argue that generous payments did not lead to declines in economic wellbeing after the seventies.

Although some have sought to link SSI to employment rates, findings are inconsistent. For instance, Maroto and Pettinicchio (2014a) found that the individual receipt of government assistance was associated with decreased employment and earnings, but at the state level certain benefits often increased average earnings. Acemoglu and Angrist (2001) have suggested that transfer payments reduce employment, but Houtenville and Burkhauser (2004) have argued that rates of employment for people with disabilities declined due to changes in Social Security, not the ADA. On the one hand, Beegle and Stock (2003) found that there was an increase in the number of disabled people collecting SSI following the ADA, which may, according to some, decrease the likelihood of looking for employment. On the other hand, Lahiri, Vaughan and Wixon (1995) found an increase in SSI denial rates prior to the ADA, and DeLeire (2000) showed that there was a small decline in payments, which paled in comparison to the decline in the disability employment rate.

In addition, there has been a legal concern regarding qualifying for employment and SSI. As Colker and Milani (2010) explained, lower courts have been divided on the issue of whether people who claim SSI because they are so disabled that they cannot work are also qualified under Title I of the ADA. However, a 1999 Supreme Court case (Cleveland v. Police Mgmt. Sys. Corp, 526 U.S. 795) ruled that because the SSA does not take into account reasonable accommodation in rendering a decision that a person is "totally disabled," this does not bar the person automatically from being qualified. Thus, while transfer payments can affect a person's need for paid employment, it is unlikely that changes in these payments can explain the continuing employment and earnings disparities for people with disabilities.

Employment Rights in Capitalist Societies

As we outlined earlier in the paper, courts have generally maintained a pro-employer or pro-business outlook in their decisions. Some scholars, however, have raised broader structural questions regarding the concept of equal rights in employment within a capitalist context. For instance, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act was intended to work within a capitalist system and thus, not meant to eliminate unemployment, but rather to deal with disparate treatment discrimination that occurs, for example, when a member of a racial group is not hired for a job because of his or her race. The Civil Rights Act is not an economic bill of rights. It by no means guarantees anyone who can work the right to work. Indeed, the unemployment rate among African Americans remains twice as high as that of whites (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014).

Similarly, the ADA does not guarantee the right to work for people with disabilities, nor does it provide affirmative action to remedy past discrimination. In fact, unlike the Civil Rights Act, neither the Rehabilitation Act nor the ADA prohibits employers from taking disability into account in making employment decisions (Colker and Milani 2010). Thus, this rights-based law can only be understood within the structural constrains of a capitalist system that limits labor market participation. As argued by Russell (2001, 2002), the failure of the ADA to increase employment for people with disabilities exposes the contradictions of promoting equal opportunity in an unequal society.

According to the Marxist tradition, capitalist societies can never have full employment. Unemployment is not an aberration but rather it functions to keep wages low. Indeed, in most countries — even those with a well-established safety net — people with disabilities remain the last minority group to have excessively high non-employment rates. People with disabilities can be viewed as the reserve army of labor or industrial reserve army (Neufeldt 1995; Russell 2001, 2002; see also Marx 1867; Keynes 1936). This means that in times of increasing overall employment where there are shortages in labor, employers reluctantly dip into this pool. But when there is an overabundance of labor, individuals with disabilities are the least likely to be employed. Following this perspective, Kruse and Schur (2003) found that people with disabilities were particularly sensitive to labor market tightness in their analysis of SIPP data. Yelin (1997) and Yelin and Katz (1994) have also shown that employment trends for the general population tend to be exaggerated in the population with disabilities. This line of reasoning links the employment of people with disabilities to broader labor market processes but, as Jenkins (1991) has asked, is the labor market participation and economic wellbeing of people with disabilities based on only these broader processes, or might there be something unique to disability?

Occupational Structures

Variation in employment and earnings among people with disabilities is also a function of their position in the occupational structure. Although numerous studies have addressed the ways in which occupational segregation limits the earnings potential for women and racial minority workers (e.g., see Tomaskovic-Devey et al. 2006; Blau, Brummand, and Liu 2013), research on disability occupational segregation has been more limited. Nonetheless, existing work has shown that people with disabilities tend to be underrepresented in some industries, but overrepresented in others (Kessler Foundation/NOD 2010; Maroto and Pettinicchio 2014b; Unger 2002). They are generally underrepresented in managerial sectors, but more concentrated in low-skilled jobs and manual labor (Jones 2008; Kaye 2009; Maroto and Pettinicchio 2014b; Smith and Twomey 2002).

Similar to other minority groups, people with disabilities have tended to fare better in federal employment (Kim 1996; Lewis and Allee 1992). For example, the number of people with disabilities in the federal government and in the social service sector increased in the 1980s, just as overall employment rates were declining (Lewis and Allee 1992; Unger 2002). However, despite the provisions in the Rehabilitation Act, in their study of federal careers, Lewis and Allee (1992) noted that people with disabilities occupied lower-grade positions. They experienced difficulty in getting promoted, and were often "pigeon-holed" into particular jobs. This suggests that while antidiscrimination legislation can create opportunities for employment, these do not necessarily improve working conditions (including career mobility and earnings outcomes) for those already employed.

People with disabilities may also self-select into different types of employment (Beegle and Stock 2003; Schur 2002, 2003). Following the ADA, employment in part-time and non-standard work grew for people with disabilities in the 1990s, which is likely a combination of worker and employer choices (Hotchkiss 2004b; Yelin 1997). Given that certain types of disabilities can require more time off from work, non-standard work arrangements are generally more common for people with disabilities. In her analyses of disability and non-standard work arrangements, Schur (2002, 2003) also found that health problems were the primary cause of non-standard work for people with disabilities, not necessarily discrimination.

People with disabilities could also differ from the rest of the population in terms of human capital and job choice (Blanck et al. 2003, 2007). Jones and Sloane (2010) suggest that people with disabilities accept certain kinds of employment, which partially explains a mismatch between their skills and job requirements. This skill mismatch then affects earnings and future job prospects, especially for people with disabilities (Jones and Sloane 2010). Compounding these effects, people with disabilities are generally underrepresented in the fastest growing sectors and overrepresented in declining industries (DeLeire 2000; Kruse and Schur 2003). This helps explain earnings gaps given that wages typically are lower or stagnate in occupational sectors that are in decline.

Disability consistently leads to lower earnings and rates of employment making it a key status for inequality. When looking at the effects of policies and discrimination, researchers need to also account for these job choice and productivity differences (Blanck et al. 2003, 2007; Jones 2008). This is important because post-ADA decreases in employment for people with disabilities could stem from a variety of factors including employer and employee preferences based on the nature of the job and the disability (Domzal et al. 2008). Non-standard work arrangements and skill mismatch, even while partially voluntary, lead to lower incomes and earnings disparities (Schur 2003; Tolin and Patwell 2003). Although many researchers focus on policies like the ADA and their role in seeking to eliminate discriminatory attitudes and practices, both supply-and-demand side characteristics that are not easily addressed by antidiscrimination legislation explain a large part of the employment and earnings inequality associated with disability status.

DISCUSSION

Over twenty years ago, researchers called for a stronger consideration of disability status in stratification research. Scholarly research on disability in sociology has grown since the 1990s, but knowledge gaps remain. Although employment and earnings disparities are well documented, researchers still need to disentangle the multiple mechanisms behind these disparities and do more to investigate the role of discrimination, attitudes, and policy in this process. The deeply rooted attitudinal and normative basis on which interaction with people with disabilities rests present a major obstacle in increasing the employment and subsequent economic wellbeing of people with disabilities, but few policies have attempted to address these issues.

The National Council on Disability (NCD) argued that when it came to the economic wellbeing of people with disabilities, the ADA had not delivered (NCD 2004). At ADAAA congressional hearings, Naomi Earp, Chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), testified that the "employment of persons with disabilities has presented the greatest ADA challenge" (U.S. House. Subcommittee on Constitution 2006), indicating that more must be done to address these employment disparities. Laws like the ADA cannot just eliminate economic inequality: they must change norms and remove stigmas. But the ADA does not instruct employers on how to remove attitudinal barriers nor is it particularly straightforward about how antidiscrimination legislation interacts with labor market contexts to produce more positive employment and earnings outcomes. Furthermore, by leaving the courts responsible for interpreting disability rights and implementing policy, the ADA has done little in addressing attitudes since the courts have not based their rulings on the assumption that attitudinal barriers have hindered employment.

The main challenge for stratification research has been to disentangle the role of the ADA in shaping economic outcomes net the effects of institutional and labor market complexities. For instance, Maroto and Pettinicchio (2014a) illustrate the complex relationship between legislative intent, enforcement, and judicial interpretation, while showcasing the multilayered institutional aspects behind the implementation of disability antidiscrimination legislation. The interplay between legislative politics and policy implementation provides important insights on possible reasons why the ADA has not been as effective in improving the economic well being of people with disabilities.

Similarly, the literature on disability labor market inequality has demonstrated the importance of supply-and-demand side factors that might lead to employment and earnings disparities. On the demand-side, these include employer preferences and attitudes, the nature of work, occupational and sector needs, practices and norms, as well as stereotypes and negative expectations about productivity and efficiency among disabled employees. On the supply side, the type of disability and preferences for certain types of work, as well as human capital, education, and professional networks also shape labor market outcomes for people with disabilities. Thus, key theories of labor market inequality like statistical discrimination, queuing, and expectation states theory highlight important relationships between supply-and-demand factors that are especially relevant for understanding how and why people with disabilities are unevenly represented across occupations and industry sectors. As researchers continue to synthesize policy arguments on one level and labor market considerations on the other, we will have a better sense as to how policies like the ADA interact with political and economic structures to produce intended policy outcomes. Hopefully, this will help to shed light on why disability antidiscrimination legislation "succeeds" or "fails" in improving the lives of people with disabilities.

CONCLUSION

Given the important role of attitudes in discriminatory practices, it is not surprising that proponents of the ADA believed attitudinal changes would come with its passage. Although preexisting civil rights legislation served as a model, people with disabilities would have to look at a rights system that paralleled, rather than evolved within, a broader civil rights framework. Disability employment discrimination legislation came about later than race, sex, and religious discrimination legislation and is not included under Title VII. It was clear in 1971, when Humphrey and Vanik first introduced the Rehabilitation Act, that disability would not find a place within existing antidiscrimination legislation, even though compelling arguments can be made to include disability as a protected group along with religion, gender, and race. But, the case of disability rights legislation is by no means an example of a unique political process nor is questioning whether policies like the ADA succeeded in removing attitudinal and structural barriers.

Although disability may have faced unique challenges, all antidiscrimination laws struggle to change attitudes. Race, sex, religion, and disability antidiscrimination legislation have all faced obstacles in implementation and enforcement. Congress did not fully define discrimination in the Civil Rights Act, and what has constituted discrimination has evolved over time as a result of various court cases and amendments that themselves were a response to challenges by new groups demanding protection and enforcement (Reskin 2001). In many ways, the effectiveness of any antidiscrimination policy rests on perceptions of discrimination on the part of employee and employer, as well as the enforcement agency's willingness to pursue complaints (Dobbin 2009; Kalev and Dobbin 2006; Reskin 2001). As Burstein (1990) observed, discrimination is only known when people see it as such, complain about it, and an enforcement agency effectively responds to those complaints.

Race and sex discrimination legislation have worked to impede, but by no means, eliminate the unequal treatment of women and minorities in the workforce (as is evidenced by experimental audit studies, see Ayers 2001; Heckman and Siegelman 1992). These efforts have been hampered by a lack of government commitment to ending discrimination and by the Court's continual siding with businesses in various discrimination cases (Dobbin 2009; Reskin 2001). Overall, the EEOC's enforcement of Title VII has been uneven due to government and interest group pressures as well as resource availability (Burstein 1989; Burstein and Edwards 1994; Reskin 2001). Consequently, race and sex inequalities in employment and earnings persist (Blau and Kahn 2006; Goldin 2006; Pager and Shephard 2008). Nonetheless, it seems that despite their limitations, policies like Title VII are generally seen as having reduced race and sex discrimination in the workplace, but disability antidiscrimination policies are seen has having to overcome bigger hurdles when it comes to changing negative attitudes about people with disabilities.

While our paper speaks specifically to the ADA and unique challenges and obstacles faced by people with disabilities in the labor market, we also situate our discussion in the broader sociological literature on stratification. Inequality researchers often overlook disability status as a basis for stratification, choosing to focus on the more common bases of race, class, and gender. Most stratification textbooks and readers examine how the categorization of people into groups — an innate quality in human beings — constitutes a first step in the stratification process (Arrighi 2007; Grusky 2014; Keister and Southgate 2012; Massey 2007; Sernau 2014). Although these books focus on a variety of group categorizations and subsequent stratification, they largely ignore disability as a status contributing to inequality. This is not something unique to textbooks. Inequality researchers often overlook disability status as a basis for stratification, choosing to focus on the more common bases of race, class, and gender. Nonetheless, individual and structural factors help explain why people with disabilities on average earn 14,000 dollars less than similar individuals with disabilities and why poverty rates tend to be 2 to 5 times greater among working-age people with disabilities than those without disabilities.

Future studies of disability discrimination should work to address these issues by situating disability in a broader discrimination framework so as to better compare disability with race and gender. Doing so would likely result in theory building and the incorporation of new methodologies into disability research. For example, experimental audit studies also offer the potential to overcome social desirability bias. Although attitudinal research shows an erosion of race and gender discrimination, audit studies indicate that it still continues to plague these groups in many areas (Pager and Shepard 2008; Quillian 2006). Audit studies on disability have been rare, but the results will likely be telling. Finally, in addition to policy arguments, researchers should also address how certain characteristics, such as occupation, job requirements, unionization, and non-standard work arrangements affect employment outcomes for people with disabilities (Blanck et al. 2003). While the boundaries of disability are fluid and change over time, bringing disability status into a more general sociological discussion of stratification will spark new avenues of research in this area.

References:

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Joshua D. Angrist. 2001. "Consequences of Employment Protection? The Case of the Americans with Disabilities Act." Journal of Political Economy 109(5):915-957.

- Altman, Barbara M., and Sharon N. Barnartt. 1993. "Moral Entrepreneurship and the Promise of the ADA." Journal of Disability Policy Studies 4(1):21-40.

- Arrighi, Barbara A. 2007. Understanding Inequality: The Intersection of Race/Ethnicity, Class, and Gender, 2nd Edition. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Arrow, Kenneth J. 1998. "What Has Economics to Say About Racial Discrimination?" Journal of Economic Perspectives 12(2):91-100.

- Arrow, Kenneth. 1973. "The Theory of Discrimination." Pp. 3-33 in Discrimination in Labor Markets, O. Ashenfelter and A. Rees (eds.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Ayres, Ian. 2001. Pervasive Prejudice: Unconventional Evidence of Race and Gender Discrimination. University of Chicago Press.

- Baldwin, Marjorie, and William G. Johnson. 1994. "Labor Market Discrimination Against Men With Disabilities." The Journal of Human Resources 29(1):1-19.

- Baldwin, Marjorie L, Lester A Zeager, and Paul R Flacco. 1994. "Gender Differences in Wage Losses from Impairments Estimates from the Survey of Income and Program Participation." Journal of Human Resources 29(3):865-887.

- Baldwin, Marjorie L., and Johnson, William G. 2006 "A Critical Review of Studies of Discrimination Against Workers with Disabilities." Pp. 119-157 in Handbook on the Economics of Discrimination, Rodgers W.M. III (ed.). Northampton, MA: Edgar Elgar Publishing.

- Balser, Deborah B. 2000. "Perceptions of On-The-Job Discrimination and Employees With Disabilities." Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 12(4):179-197.

- Barnard, Thomas H. 1990. "The Americans with Disabilities Act: Nightmare for Employers and a Dream for Lawyers?" St. John's Law Review 64:229-252.

- Beegle, Kathleen, and Wendy a. Stock. 2003. "The Labor Market Effects of Disability Discrimination Laws." The Journal of Human Resources 38(4):806.

- Blau, Francine D., P. Brummand, and Yung-Hsu Liu, A. 2013. "Trends in Occupational Segregation by Gender 1970-2009: Adjusting for the Impact of Changes in the Occupational Coding System. Demography 50(2):471-492.

- Blau, Francine D. and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2006. "The Gender Pay Gap: Going, Going…But Not Gone." In The Declining Significance of Gender? F.D. Blau, M.C. Brinton, and D.B. Grusky (eds.). Russell Sage.

- Blanck, Peter, Meera Adya, William N. Myhill, Deepti Samant, and Pei-Chun Chen. 2007. "Employment of People with Disabilities: Twenty-Five Years Back and Ahead." Law and Inequality 25:323-354.

- Blanck, Peter, Lisa Schur, Douglas Kruse, Susan Schwochau, and Chen Song. 2003. "Calibrating the Impact of the ADA's Employment Provisions." Stanford Law and Policy Review 14(2):267-290.

- Bradsher, Julia E. 1996. "Disability Among Racial and Ethnic Groups." Disability Statistics Abstract No. 10. National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation, U.S. Department of Education: Washington, D.C.

- Burris, Scott, and Kathryn Moss. 2007-2008. "The Employment Discrimination Provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act: Implementation and Impact." Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal 25(1):0-32.

- Burkhauser, Richard V., Mary C. Daly, Andrew J. Houtenville, and Nigar Nargis. 2001. Economics of Disability Research Report #5: Economic Outcomes of Working-Age People with Disabilities over the Business Cycle-An Examination of the 1980s and 1990s. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

- Burkhauser, Richard V., and David C Stapleton. 2003. "Introduction." Pp. 1-22 in The Decline in Employment of People with Disabilities: A Policy Puzzle, edited by David C. Stapleton and Richard V. Burkahauser. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

- Burkhauser, Richard V., and Andrew J Houtenville. 2006. A Guide to Disability Statistics from the Current Population Survey - Annual Social and Economic Supplement (March CPS). Ithaca, NY.

- Burstein, Paul. 1990. "Intergroup Conflict, Law, and Labor Market Discrimination." Sociological Forum 5:459-476.

- Burstein, Paul. 1989. "Attacking Sex Discrimination in the Labor Market: A Study in Law and Politics." Social Forces 67:641-665.

- Burstein, Paul and Mark Evan Edwards. 1994. "The Impact of Employment Discrimination Litigation on Racial Disparity in Earnings: Evidence and Unresolved Issues" Law and Society Review 28(1):79-112.

- Colker, Ruth and Adam A. Milani. 2010. Federal Disability Law in a Nut Shell. West.

- Cuddy, Amy J.C., Susan T. Fiske, and Peter Glick. 2007. "The BIAS Map: Behaviors from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92:631-648.

- DeLeire, Thomas. 2000. "The Wage and Employment Effects of the Americans with Disabilities Act." The Journal of Human Resources 35(4):693-715.

- DeLeire, Thomas. 1995. "The Unintended Consequences of the ADA." Regulation 23(1):21— 24.

- Dobbin, Frank. 2009. Inventing Equal Opportunity. Princeton University Press.

- Donahue, John J., Michael Ashley Stein, Christopher L. Griffin Jr., and Sascha Becker. 2011. "Assessing Post-ADA Employment: Some Econometric Evidence and Policy Considerations." Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 8(3): 477-503.

- Dovidio, John F. and Michelle R Hebl. 2005. "Discrimination at the Level of the Individual: Cognitive and Affective Factors. Pp. 11-36 in Discrimination at Work: The Psychological and Organizational Bases. R. L. Dipboye and A. Colella, editors. Erlbaum.

- Fiske, Susan T., Amy J.C. Cuddy, Peter Glick, and Jun Xu. 2002. "A Model of (Often Mixed) Stereotype Content: Competence and Warmth Respectively Follow from Perceived Status and Competition." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82(6): 878-902.

- Goldin, Claudia. 2006. "The Rising (and Then Declining) Significance of Gender." In The Declining Significance of Gender? F.D. Blau, M.C. Brinton, and D.B. Grusky (eds.). Russell Sage.

- Greenwald, Anthony G. and Linda Hamilton Krieger. 2006. "Implicit Bias: Scientific Foundations." California Law Review 94(4):945-967.

- Grusky, David B. 2014. Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in a Sociological Perspective. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Haveman, Robert, and Barbara Wolfe. 1990. "The Economic Well-Being of the Disabled: 1962-84." The Journal of Human Resources 25(1):32-54.

- Heckman, James J. and Peter Siegelman. 1992. "The Urban Institute Audit Studies: Their Methods and Findings." Pp. 187-258. Clear and Convincing Evidence: Measurement of Discrimination in America. M. Fix and R. J. Struyk, editors. Urban Institute Press.

- Hernández, Tanya. 2006. "The Intersectionality of Lived Experience and Anti-Discrimination Empirical Research." Pp. 325-337 in Handbook of Employment Discrimination Research: Rights and Realities. L.B. Nielsen and R.L. Nelson (eds.). Springer.

- Holzer, Harry J. 1996. What Employers Want: Job Prospects for Less-Educated Workers. Russell Sage.

- Hotchkiss, Julie L. 2004a. "A Closer Look at the Employment Impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act." Journal of Human Resources 34:887-911.

- Hotchkiss, Julie L. 2004b. "Growing Part Time Employment Among Workers with Disabilities." Economic Review. Atlanta, GA: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

- Houtenville, Andrew J, and Adam F. Adler. 2001. Economics of Disability Research Report # 4. Estimates of the Prevalence of Disability, Employment Rates, and Median Household Size-Adjusted Income for People with Disabilities Aged 18 Through 64 in the United States By State 1980 through 2000. Cornell University: Ithaca, NY.

- Houtenville, Andrew and Richard V. Burkhauser. 2004. Did the Employment of People with Disabilities Decline in the 1990s, and Was the ADA Responsible? Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

- Jenkins, Richard. 1991. "Disability and Social Stratification." The British Journal of Sociology 42(4):557-580.

- Jones, Melanie K. 2011. "Disability, Employment and Earnings: An Examination of Heterogeneity." Applied Economics, 43, 1001-1017.

- Jones, Melanie K. 2008. "Disability and the Labour Market: A Review of the Empirical Evidence." Journal of Economic Studies 35(5):405-424.

- Jones, Melanie K., and Peter J. Sloane. 2010. "Disability and Skill Mismatch." Economic Record 86:101-114.

- Kaye, Stephen H. 2009. "Stuck at the Bottom Rung: Occupational Characteristics of Workers with Disabilities." Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 19(2):115-28.

- Kaye, Stephen H. 2003. Improved Employment Opportunities For People with Disabilities, Disability Statistics Report (17). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research.

- Kaye, Stephen H., Lita H. Jans, and Erica C. Jones. 2011. "Why Don't Employers Hire and Retain Workers with Disabilities?" Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 21(4):526-36.

- Kessler Foundation/National Organization on Disability (NOD). 2010. NOD Survey of Employment of Americans with Disabilities. New York: Harris Interactive.

- Keister, Lisa A. And Darby E. Southgate. 2012. Inequality: A Contemporary Approach to Race, Class, and Gender. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. New York: Harcourt.

- Kim, Pan. S. 1996. "Disability Policy: An Analysis of the Employment of People with Disabilities in the American Federal Government." Public Personnel Management 25(1):73-88

- Komp, Catherine. 2006. "Attitude not Cost Barrier to Disabled Workers." Center on Disability Studies Information Brief. The New Standard 1(6).

- Kruse, Douglas, and Lisa Schur. 2003. "Employment of People with Disabilities Following the ADA." Industrial Relations 42(1):31-66.

- Lahiri, Kajal, Denton R. Vaughan, and Bernard Wixon. 1995. "Modeling SSA's Sequential Disability Determination Process Using Matched SIPP Data." Social Security Bulletin 58(4):3-42.

- Lee, Barbara A. 2003. "A Decade of the Americans with Disabilities Act: Judicial Outcomes and Unresolved Problems." Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 42(1):11-30.

- Lewis, Gregory B, and Cheryl Lynn Allee. 1992. "The Impact of Disabilities on Federal Career Success." Public Administration Review 52(4):389-397.

- Lundberg, Shelley J., and Richard Startz. 1983. "Private Discrimination and Social Intervention in Competitive Labor Markets." The American Economic Review 73:340-347.

- Maroto, Michelle and David Pettinicchio. 2014a. "The Limitations of Disability Antidiscrimination Legislation: Policymaking and the Economic Well-being of People with Disabilities." Law and Policy 36(4):370-407.

- Maroto, Michelle and David Pettinicchio. 2014b. "Disability, structural inequality, and work: The influence of occupational segregation on earnings for people with different disabilities," Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 38:76-92.

- Marx, Karl. [1867]1967. Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production, Vol. I-III. New York: International Publishers.

- Moss, Kathryn, Michael Ullman, Jeffrey W. Swanson, Leah M. Ranney, and Scott Burris. 2005. "Prevalence and Outcomes of ADA Employment Discrimination Claims in Federal Courts." Mental and Physical Disability L. Rep. 29(3): 303-311.

- Moss, Philip and Chris Tilly. 2001. Stories Employers Tell: Race, Skill, and Hiring in America. Russell Sage.

- Neufeldt, Aldred H. 1995. "Empirical Dimensions of Discrimination against Disabled People." Health and Human Rights 1(2):174-189.

- O'Brien, Ruth. 2001. Crippled Justice. University of Chicago Press.

- Pager, Devah, and Hana Shepherd. 2008. "The Sociology of Discrimination: Racial Discrimination in Employment, Housing, Credit, and Consumer Markets." Annual Review of Sociology 34:181-209.

- Pelka, Fred. 2012. What We Have Done: An Oral History of the Disability Rights Movement. Boston and Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Pettinicchio, David. 2013. "Strategic Action Fields and the Context of Political Entrepreneurship: How Disability Rights became part of the Policy Agenda." Research in Social Movements, Conflict and Change 36: 79-106.

- Pettinicchio, David. 2012. "Institutional Activism: Reconsidering the Insider/Outsider Dichotomy." Sociology Compass 6:499-510.

- Randolph, D.S., and E.M. Anderson. 2004. "Disability, Gender, and Unemployment Relationships in the United States from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System." Disability and Society 19:403-414.

- Reskin, Barbara F. 2001. "Employment Discrimination and Its Remedies." Pp. 567-599 in Sourcebook of Labor Markets: Evolving Structures and Processes. Ivar Berg and Arne L. Kalleberg, (eds.). Klewer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Reskin, Barbara, and Patricia A. Roos. 1990. Job Queues, Gender Queues: Explaining Women's Inroads into Male Occupations. Temple University Press.

- Ridgeway, Cecilia L. 1997. "Interaction and the Conservation of Gender Inequality: Considering Employment." American Sociological Review 62,=:218-235.

- Ridgeway, Ceclia L. 1991. "The Social Construction of Status Value: Gender and Other Nominal Characteristics." Social Forces 70:367-386.

- Robert, Pamela M, and Sharon L Harlan. 2006. "Mechanisms of Disability Discrimination in Large Bureaucratic Organizations: Ascriptive Inequalities in the Workplace." Sociological Quarterly 47(4):599-630.

- Robey, Kenneth L., Linda Beckley, and Matthew Kirschner. 2006. "Implicit Infantilizing Attitudes About Disability." Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 18(4):441-453.

- Russell, Marta. 2002. "What Disability Civil Rights Cannot Do: Employment and Political Economy." Disability & Society 17(2):117-135.

- Russell, Marta. 2001. "Disablement, Oppression, and the Political Economy." Journal of Disability Policy Studies 12(2):87-95.

- Schur, Lisa A. 2004. "Is There Still a Double Handicap?" Pp. 253-271 in Gendering Disability, Bonnie G. Smith and Beth Hutchinson (eds.). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Schur, Lisa A. 2002. "Dead End Jobs or a Path to Economic Well Being." Behavioral Sciences and the Law 20:601-620.

- Schur, Lisa, Douglas Kruse, Joseph Blasi, and Peter Blanck. 2009. "Is Disability Disabling in All Workplaces? Workplace Disparities and Corporate Culture." Industrial Relations 48(3):381-410.

- Schwochau, Susan, and Peter David Blanck. 2000. "The Economics of the Americans with Disabilities Act, Part III: Does the ADA Disable the Disabled?" Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law 21:271-313.

- Scotch, Richard K. 2001. From Goodwill to Civil Rights. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Sernau, Scott. 2014. Social Inequality in a Global Age, 4th Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Shapiro, Joseph P. 1993. No Pity: People with Disabilities Forging a New Civil Rights Movement. New York: Random House.

- Shaw, Linda R., Fong Chan, and Brian T. McMahon. 2012. "Intersectionality and Disability Harassment: The Interactive Effects of Disability, Race, Age, and Gender." Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 55:82-91.

- She, Peiyun, and Gina A Livermore. 2007. "Material Hardship, Poverty, and Disability Among Working-Age Adults." Social Science Quarterly 88(4):970-989.

- Smith, Allan, and Breda Twomey. 2002. "Labour Market Experience of People with Disabilities." Labour Market Trends, August:415-27.

- Stein, Michael Ashley. 2003. "The Law and Economics of Disability Accommodations." Duke Law Journal 53(1):79-191.

- Tajfel, Henri. 1982. "Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations." Annual Review of Psychology 33:1-39.

- Tolin, Tom and Martin Patwell. 2003. "A Critique of Economic Analysis of the ADA." Disability Studies Quarterly 23(1):130-142

- Tomaskovic-Devey, D., Zimmer, C., Stainback, K., Robinson, C., & Taylor, T. 2006. "Documenting Desegregation: Segregation in American Workplaces by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 1966-2003." American Sociological Review 71:565-588.

- Unger, Darlene D. 2002. "Employers' Attitudes Toward Persons with Disabilities in the Workforce: Myths or Realities?" Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 17(1):2-10.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2015. Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics—2014. U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), USDL-15-1162.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2014. Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2013. U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), Report 1050.

- U.S. House. Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Constitution. 2006. Hearing on the Americans with Disabilities Act Sixteen Years Later (2007-H521-10, September 13). Text in ProQuest® Congressional Hearings Digital Collection. http://congressional.proquest.com/congressional/docview/t05.d06.2007-h521-10?accountid=14784 (accessed August 3, 2015).

- U.S. House. Committee on Education and Labor. 2008. Hearing on H.R. 3195, ADA Restoration Act of 2007 (2008-H341-30, January 29). Text in ProQuest® Congressional Hearings Digital Collection. http://congressional.proquest.com/congressional/docview/t05.d06.2008-h341-30?accountid=14784 (accessed August 3, 2015).

- Vaughn, E. Daly, Adrian Thomas, and Andrea L. Doyle. 2011. "The Multiple Disability Implicit Association Test: Psychometric Analysis of a Multiple Administration IAT Measure." Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 54(4):223-235.

- Wilgosh, Lorraine R., and Deborah Skaret. 1987. "Employer Attitudes Toward Hiring Individuals with Disabilities: A Review of the Recent Literature," Canadian Journal of Rehabilitation 1: 89-98.

- Wilkins, Roger. 2003. "Labour Market Outcomes and Welfare Dependence of Persons with Disabilities in Australia." Working Paper no. 2/03, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne.

- Yelin, Edward H. 1997. "The Employment of People with and without Disabilities in an Age of Insecurity." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 549(1):117-128.

- Yelin, Edward H. and Patricia P. Katz. 1994. "Labor Force Trends of Persons With and Without Disabilities." Monthly Labor Review 117:36-42.

Endnotes

- Harkin said this at the

20th anniversary of the ADA (2010, 156 Cong Rec S6131-S6144)

Return to Text - 1990, 136 Cong Rec S 9684.

Return to Text - However, some of these declines

were likely due to the greater number of workers being classified as

disabled (Hotchkiss 2004a).

Return to Text - In order to account for school