This study discusses special education services across three provinces of Sri Lanka. It sought to answer the following research questions: (a) who are the children receiving special education services? (b) what are the current special education practices? (c) what are parents' views on communication supports, inclusion and literacy? Sixty-seven parents from the Western, Southern and Northern provinces participated in an in-person survey interview. The results indicated no children older than 14 years and very few children with severe needs received school services. This study identified some key implications including a need for Speech and Language Therapists to work in schools. It also discusses the benefits and challenges of implementing inclusive education in low- and middle-income (LAMI) countries.

The United Nations Children's Fund (2009a) reports there are 200 million children with disabilities in the world. A report published by the World Bank (2010) found that 15% of the world's populations live in low-income countries. Activists, educators, and parents seek to improve special education services worldwide. This interest arose out of international policies and conferences discussing and supporting universal education. The United Nations World Conference on Education for All (United Nations Educational, Scientific & Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 1990) highlighted improving access to education as a goal for all low- and middle-income countries (LAMI) countries. Recommendations have been made for inclusive education policies to be put in place so children with disabilities can experience their rights to an appropriate education (Dawson, Hollins, Mukongolwa, & Witchalls, 2003).

Inclusion

The rationale behind inclusion is that a child with a disability will best be able to cope in a typical world by being able to adapt in a regular school environment (Eleweke & Rodda, 2002). There are no universally accepted definitions of the terms "Inclusion" and "Inclusive Education" (Humphrey, 2008). Booth and Ainscow (2000) describe inclusion in a broad sense to include the child's presence (without the use of pullout classes or other "integrated segregation"), participation (the quality of the education the child is receiving), acceptance (by peers and others), and achievement (academic achievement and other skills development) in mainstreamed schools whenever possible.

Inclusion entails the participation of children with disabilities in a regular school or classroom with the aim of providing equal opportunities and experiences as typical or non-disabled students. Marston (1996) describes the following three types of placement models: First, the full inclusion model, children with disabilities receive all instruction in the general education classroom. The special education teacher and general education teacher collaborate to provide effective instruction. Second, the combined services model, children receive instruction in both a pullout resource room as well as in general education. The special education and general education teachers team together to provide instruction. Third, the pullout model, children receive services in the pullout resource room only. There is no formal collaboration between the special education and general education teachers.

Including children with disabilities in regular schools is a challenge faced by many countries around the world (Eleweke & Rodda, 2002). Barriers to implementing inclusion include inadequate facilities and trained personnel, lack of funding, ineffective and inefficient use of technology, and lack of support to teachers practicing inclusion (Eleweke & Rodda, 2002; Furuta, 2009; Gronlund, Lim, & Larsson, 2010). Despite inclusion being a challenge, there have been many documented social and academic benefits for students with and without disabilities (Kent-Walsh & Light, 2003; Soto, Müller, Hunt, & Goetz, 2001). Lopez (1999) studied inclusive education in Sri Lanka and found that typical peers, teachers, principals and parents all expressed positive attitudes toward inclusion.

Parents' views

No matter the culture or country, it is important to consider parents as a consumer group and seek out their views and expectations. Involving parents of children with disabilities in their education is an imperative part of providing effective services. This is especially important when the situation involves children with significant cognitive deficits, complex communication needs, or young children who may be dependent on adult caregivers in their lives to determine their needs and interests in order to make the best decisions on their behalf (Leiter, 2004). In such situations, when individuals may not be able to express their own views, it is important that the voice of the individual with a disability be expressed through a parent's view. In the United States the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990 and its reauthorization in 1997 required parent involvement in the educational decision making process for their children with disabilities; however, the reality of parental involvement remains elusive with culturally diverse and with low-income families (Kalyanpur, Harry & Skrtic, 2000). Schools are often unsuccessful in achieving high levels of participation by minority and low-income parents (Lavine, 2010). Nevertheless, it is still important to obtain input from all parents regarding their children's education, as they are key stakeholders involved in the education system (Lindsay & Dockrell, 2004). Parents' views are especially important when interacting in a South Asian context (such as Sri Lanka), because of the importance placed on the family unit. It is often less about the needs of the individual with a disability, rather about the impact of decisions upon the entire family unit, including the individual with a disability.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is a small pearl-shaped island located just off the coast of India. It has a rich culture and heritage spanning more than 2000 years. The United Nations Development Programme (2000) classifies Sri Lanka as a developing country. Despite this, it has relatively high social indicators (UNICEF, 2009b). The literacy rate is 93.2% for males and 90.8% for females (Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 2012).

Sri Lanka is a country that values education. Education participation among children without disabilities is 95% for children between 5-14 years and 65% in the 15-19 years age group (The United Nations Children's Fund Regional Office for South Asia [UNICEF ROSA], 2007). In stark contrast, of the reported 10.6% of school-aged children in Sri Lanka who have disabilities, 10.2% do not attend school because of their disability, meaning only 0.4% of these children attend school (UNICEF ROSA, 2007). The Education Policy (1948) mandates free education at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels (Ministry of Human Resource Development, Education and Cultural Affairs, 2000; Yokotani, 2001). A majority of schools in the country are government schools; approximately 2% of educational facilities are private (UNICEF ROSA, 2007).

Although these statistics appear promising, there are discrepancies between provinces in the country. The quality of education in Sri Lanka is compromised by unequal economic development, a history of civil conflict and regional imbalances (UNICEF, 2009b). Education has been significantly affected by a 26-year long civil war leaving hundreds of thousands of families and children displaced in the Northern province, disrupting the education of many. This also resulted in a high prevalence of war-induced physical, cognitive, and psychological disabilities (Campbell, 2009). Statistics indicate that 7% of the population in Sri Lanka present with a disability, this amounts to about 1,407,000 people (United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific [UNESCAP], 2010).

The government of Sri Lanka has passed legislation and policies focused on including individuals with disabilities in society (Campbell, 2009). Fundamental rights for people with disabilities are guaranteed under Article 4 of the constitution, and under the Act for the Protection of Rights of Persons with Disabilities enacted in 1996 (Yokotani, 2001; Cambell, 2009). However, at present, there is no education law that mandates children with disabilities receive education services. In spite of Sri Lanka's high school enrollment rate, many children with disabilities do not attend school (Ministry of Social Welfare, 2003). The stigma and negative attitudes associated with disability often make people unwilling to even admit they have a family member with a disability, thus preventing children with disabilities from accessing special education services (Kalyanpur, 2008). In addition, providing services for a large population of individuals with disabilities is a difficult task for LAMI countries like Sri Lanka (Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2002).

Children with disabilities in Sri Lanka are educated either through inclusion in mainstreamed schools or through specialized schools (Yokotani, 2001). The Sri Lankan Ministry of Education initiated special units, which were integrated special education programs within regular government schools, in the late 1960s (Furuta, 2006). Currently, there are four educational options for children with disabilities in Sri Lanka: specialized schools, special education units within regular education schools, inclusive regular education schools, and special resource centers attached to regular education schools (Hettiarachchi, & Das, 2014). There are specialized schools run by the government of Sri Lanka. There are ten specialized schools in the Western province, one specialized school in the Northern province and four specialized schools in the Southern province (Government of Sri Lanka, 2013). In addition, the number of special education units within regular schools across these provinces are as follows: 130 special units in the Western province, 116 special units in the Northern province, and 105 special units in the Southern province (Government of Sri Lanka, 2013). However, the Ministry of Social Welfare reports that despite the free educational policy and established special units, there are still students with disabilities who continue to not have access to services (as cited in Furuta, 2009). Barriers to accessing special education include a limited number of rural schools having special education units (Furuta, 2006), administrators denying children with disabilities admission to schools, an insufficient number of qualified teachers, and parents lacking awareness regarding educational facilities (Furuta, 2006; Furuta, 2009; UNICEF ROSA, 2007). There is a general lack of awareness in society that people with disabilities can benefit from schooling and become contributing members of society (Furuta, 2009).

In 2002 the Asian Development Bank requested LAMI countries to create a database with the numbers and needs of individuals with disabilities (as cited in Kalyanpur, 2008). However, to date there has been no formal attempt to document the numbers and needs of individuals with disabilities, or specifically the number of children with disabilities in Sri Lanka. Disability studies as a field itself remains under developed in Sri Lanka (Campbell, 2011). This shortage of information on individuals with disabilities and their scope of needs make social planning a challenge (Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2002). Furthermore, no previous research study has examined parents' views on current special education services, what services parents value, and what services parents want their children to have access to in the future. This study sought to answer the following research questions,

- Who are the children receiving special education services? (Sampled across 3 provinces in Sri Lanka)

- What are the current special educational practices in these provinces?

- What are parents' views on communication supports, inclusion and literacy?

Method

The research questions were addressed through a face-to-face survey interview. Wherever needed, conversational flexible interviewing techniques were utilized to clarify questions and ensure that respondents understood the questions (Schober & Conrad, 1997). Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board.

Survey Development

The authors developed the survey questionnaire for this study. The survey was constructed based on a review of the literature and input from the primary investigator, who is from Sri Lanka, to ensure that the questions were culturally appropriate. The demographic questions in section one were adapted from Hetzroni's (2002) study on Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) use in Israel. The questions and response categories on the survey that pertained to the child's physical skills, inclusion and literacy adapted a similar survey style as the "WG questionnaire" (UN Washington Group, 2006). Eight questions from section four regarding the child's communication skills were adapted from the Communication Matrix Profile (Rowland, 2011). These eight questions covered the four main purposes of communication: to express needs and wants, to exchange information, to maintain social closeness and to engage in social etiquette (Light, 1988).

This survey was specifically developed for parents of children with disabilities that asked specific questions regarding any communication difficulties the children experienced. It was anticipated that due to the children's potential communication difficulties sharing information on their education experiences would be a challenge. Therefore, it was decided that parents' views should be sought. In addition, parents are key stakeholders in their children's education system. The survey was pilot tested with an American parent living in the United States to assess if the questions were worded appropriately for a parent of a child with a disability. No pilot testing was carried out with Sri Lankan parents due to not having access to these parents. Additionally, parents in Sri Lanka may have been apprehensive regarding discussing their child with disabilities with the researchers via distance mediums as compared to face-to-face interactions due to the stigma and negative attitudes associated with disability (Hettiarachchi, & Das, 2014; Kalyanpur, 2008) in South-Asian cultures. Two of the majority religions in Sri Lanka are Buddhism and Hinduism. Both these religions believe in the concept of Karma. Karma can be explained as facing a consequence in the present due to some negative action taken in the past. Therefore, one common belief is that having a child with a disability is the consequence of a past parental sin or negative action. The climate of stigma associated with disability and the need for building trust and rapport with parent participants reinforced the importance of a face-to-face methodology. No significant changes were made following the pilot survey interview. The final version of the survey consisted of five sections (a) child's demographics, (b) physical skills, (c) communication needs and interventions, (d) questions related to inclusion, and (e) questions related to literacy.

Participants

Parents of children with disabilities were recruited for this study through the investigator's personal contacts, parent support group organizations, private organizations working with children with special needs, and government school authorities. These individuals and organizations were requested to disseminate recruitment materials to potential participants. The Western, Northern and Southern provinces were identified as they provided a diverse geographic and ethnic representative sample of Sri Lankan society. Parents were considered eligible if they (a) were a parent of a child with special needs, (b) had a child who was currently receiving education services or had previously received services (within the past six months) through a regular school or specialized school (government or private), (c) had a child with a disability who did not have a primary diagnosis of visual or hearing impairment, (d) were willing to participate in a face-to-face, survey interview lasting between 30-60 minutes, and (e) were from the Western, Northern or Southern provinces. All parents who received recruitment materials and were willing to participate were given an opportunity to do so regardless of the age of their child.

Data Collection

The primary investigator was the sole interviewer in all of the in person face-to-face survey interviews conducted in Sinhala and English. Competent translators were used to conduct interviews in Tamil with participants from the Northern province. The translators used were teachers or individuals who had direct involvement with the education system, and were native Tamil speakers. When a translator was used, the interviewer asked the questions in English and the translator translated the questions verbatim. Participants' responses in Tamil were translated verbatim in English. The interviewer read each question to the participant and, based on the response provided, checked off a corresponding answer on the survey. All the interviews were digitally recorded. The interviews were conducted at locations convenient to participants such as schools where their children attended, places of work or homes, and at a private organization that provides extracurricular activities to children with disabilities.

Data Analysis

Data were collected on the survey questionnaire by the interviewer. Each survey was coded and entered into an excel sheet. A master list of codes was developed to keep track of each response and its corresponding code number (Salant & Dillman, 1994). Responses from section four, pertaining to the child's communication level, were entered into the Communication Matrix Profile online and each child's individual profile was generated. Only the responses to the questions that were asked were entered into the profile. Children were classified accordingly from levels I to VII, depending on the level with the most number of mastered communicative behaviours. Level V and above is considered being symbolic, meaning the child uses either words, signs, or pictures to communicate.

After all data were entered for all three provinces, data verification was done by a research assistant to ensure there were no data entry errors (Salant & Dillman, 1994). Descriptive statistics such as frequency counts and percentages, as well as means and medians, were obtained using SPSS.

Results

The results from the quantitative section of the survey conducted are presented. Twenty-five participants from the Western Province, 23 participants from the Southern Province and 19 participants from the Northern Province participated in the study (total of 67 parent participants).

Children's Demographics and Traits

The children's demographics information is presented in Table 1. The ages of individuals receiving services ranged from 4 to 39 years in the Western province (mean=10.12 years), from 6 to 15 years in the Southern province (mean=9.91 years) and from 4 to 23 years in the Northern province (mean=10.42 years). A large majority (64%, n=43) of the children receiving special education services across all three provinces were male. Children receiving special education services were diagnosed with Down syndrome (39%, n=26), autism spectrum disorder (10%, n=7), cerebral palsy (12%, n=8), developmental delay (12%, n=8) or a dual diagnosis (13%, n=9). As seen in Table 1, 52% (n=35) of these children were classified as having mild and 42% (n=28) moderate degrees of severity. The number of children classified as having a severe disability was only 6% (n=4).

Children's traits are detailed in Table 2. Gross motor skills were described in terms of ambulation. Across all provinces, 89% (n=60) of children were able to walk independently. There were very few children who either required assistance with walking (6%, n=4) or used wheelchairs (2%, n=1). A majority (86%, n=58) of the children had the fine motor skills to be able to write independently. There were very few children who either required assistance with fine motor tasks such as writing (9%, n=6) or were unable to write (4%, n=3). Parents were asked how much of their children's communication they understood. The overall finding was that 43% (n=29) of parents felt their children were intelligible 100% of the time, while 3% (n=2) of parents felt their children were intelligible less than 50% of the time. In addition, 75% (n=50) of parents' responded "none" when asked if there were people they wished their child could communicate with. Of those that identified individuals in response to this question, 10% (n=7) of parents listed peers and 10% (n=7) listed multiple people.

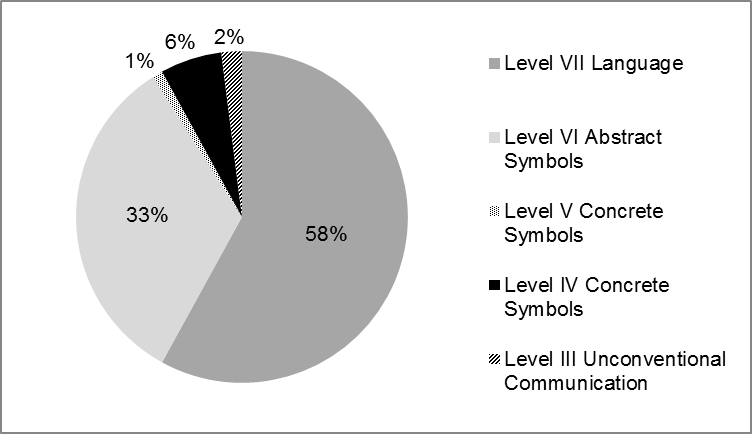

Children's communication levels were classified according to the Communication Matrix Profile (Rowland, 2011). Many of the children across all three provinces were classified as being at either level VI-Abstract Symbols (32.8%, n=22) or level VII-Language (58.2%, n=31). Level VI indicates that the child is starting to use single words (signs or pictures) to communicate and at level VII the child is beginning to combine two to three symbols (words, signs or pictures) to communicate (Rowland, 2011). There were no children in the sample who were reported to be early beginning communicators (Figure 1). Parents also responded to whether or not they felt their children needed help with communication, 79.1% (n=53) of parents felt their children required help with communication.

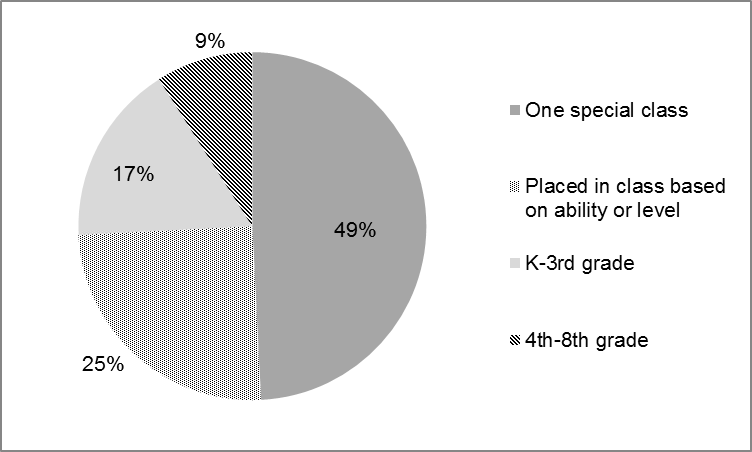

Children varied in terms of their school placements. Across all three provinces, 58.2% (n=39) of children with disabilities were educated in regular government schools. Overall 49.2% (n=33) of children were placed in one special unit (self-contained classroom) regardless of their age or abilities. Significantly few children (25%, n=16) were placed in classrooms based on their skills and abilities (Figure 2). Of the sample 17% (n=11) were placed in a classroom that was K-3rd grade, and 9% (n=7) were placed in a classroom that was 4th-8th grade.

Special Education Supports and Practices

Communication supports. Parents were asked about current educational supports and practices of the special education system in which their child was enrolled. Of the 53 parents who responded "yes" to the question of whether or not they felt their children needed help with their communication, 75% (n=15) of parents from the Western province and 70% (n=14) of those from the Southern province reported their children were currently receiving communication support at school. In contrast, 53.8% (n=7) of parents from the Northern province stated their children were not receiving communication support at school. Of the parents who responded their children were receiving communication support, 82.8% (n=29) of them indicated this support was provided by a teacher and not a communication specialist. Only 11.4% (n=4) of parents mentioned receiving communication support by a speech and language therapist.

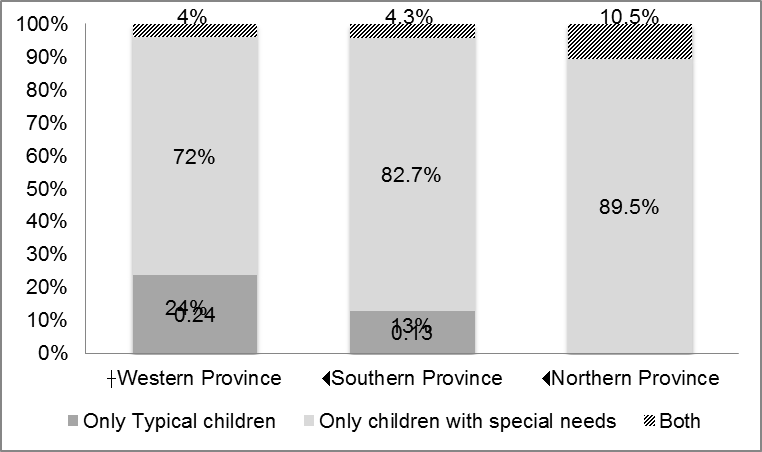

Inclusionary practices. Across all three provinces an overwhelming majority (81%, n=54) of parents reported that their children were most often in segregated classrooms exclusively for children with disabilities (Figure 3). Some parents reported their children spent time with both typically developing and children with disabilities (6%, n=4). Few parents reported their children spent time with just typically developing peers (13%, n=9). Corresponding to the number of children in segregated classrooms, 81% (n=54) of parents stated that their children spent 0% of the school day with typically developing children. See Figure 3.

Literacy practices. Results from this section revealed that a majority of the children from all three groups either needed assistance to read (52.2%, n=35) or were unable to read (41.8%, n=28). It was also reported that 70.1% (n=47) of children across the groups followed a completely different curriculum from that of the mainstream. Most participants across all three provinces responded that at least some emphasis was placed on teaching reading (79.1%, n=53) and writing (76.1%, n=51) at school.

Parents' views on Communication Supports, Inclusion and Literacy

All parents (n=40) who were asked if they would like their children to receive communication support by a Speech and Language Therapist in school responded "yes." Parents felt inclusion with typical children would be beneficial; a majority (92%, n=22) of parents from the Western and (95.7%, n=22) Southern provinces and over half (63.2%, n=12) of parents from the Northern province expressed this. Almost all parents (98.5%, n=66) felt it was important for their children to develop literacy skills.

Discussion

To paint an accurate picture of the special education system in Sri Lanka, it is essential to first understand the characteristics of children who require special education services and their needs. This information can be used to shape appropriate government policies and educational practices. It is equally important to obtain these children's parents' views on current supports and educational practices so their input can also guide special education policies and services for their children and those like them in the future.

All three provinces shared similar trends in the data. A few private special schools in the Western and Northern provinces included adults. Services for adults with developmental disabilities in Sri Lanka are scarce. Consequently, many of these adults continued to attend school even after reaching the typical age for graduation. Furuta (2009), in his study about special education preschools in Sri Lanka, found that children in the preschools ranged from preschool age to adults. In contrast to these private special schools, none of the children who attended the special education units in government schools were older than 14 years. Parents reported that currently there is an age limit of 14 years imposed on these units. They expressed concern about their children's future once they aged out of the school system. At present, there are no government regular schools that provide special education services at the high school level, and no transition services to help these individuals transition from school to the community. While it is reassuring that the government of Sri Lanka has measures in place providing children with disabilities access to education during the elementary and early middle school ages, it is concerning that little has been done to further these services beyond school-age years.

It was promising to note that children with a wide variety of diagnoses were accessing educational services; however, most of these children were diagnosed with the more "visible" disabilities such as Down syndrome or cerebral palsy. Very few children receiving services were diagnosed with non-apparent disabilities. About 10% of the total sample was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), indicating there is some awareness of this diagnosis. Many of the children were reported to have mild or moderate degrees of severity; there were only four children in the entire sample reported to have severe levels of disability. Additionally, a majority of the children in this sample were mobile and able to walk independently. This suggests that children with severe disabilities are not accessing educational services.

Based on the Communication Matrix (Rowland, 2011) a significant number of children were classified as being at either the abstract symbol level (level VI) or at the language level (level VII) of communication. Although these children were classified as being on the higher end of the communication levels on the Communication Matrix, this is not an indication that they had functional language skills, as the Matrix is designed to be for children who are younger. This could be the reason why most parents still felt their children needed help with communication. There were no children in the sample reported to be beginning communicators. Saddhananda (2001), as reported in UNICEF ROSA (2007), found that 50.8% of individuals with communication difficulties never attend school. It is deeply concerning that the current data too showed that children with severe communication and motor impairments are not in schools. Most schools are not equipped to handle their needs and teachers may not feel competent due to lack of sufficient training. Often times, these children are refused admission to school because of the severity of their needs. Additionally, some parents may not see any value in educating children who are severely impaired (Kalyanpur, 2011).

Most children received special educational services through free, regular government schools. It was observed and reported by parents that, in many cases, all the children with disabilities were placed in one self-contained classroom or special education unit regardless of age or ability. This educational placement accounted for almost 50% (n=33) of the children in the study. In one particular school that the primary investigator visited there were more than twenty children in the unit with just one teacher and a parent volunteer to assist. Although these children were receiving educational services, it is questionable how effective these services are in overcrowded classrooms with inadequate teacher support. Thus, even those who access education do not always receive an appropriate education.

This study also examined current educational supports and practices in terms of communication support, inclusion and literacy provided in the special education system. At present, there are no Speech and Language Therapists (SLT) employed in any government schools in Sri Lanka. This is due to both the limited number of professionals in the country, and because there is no government allocation for SLTs to work in schools. Currently, professionals work primarily in hospitals, with a handful employed in private schools. Therefore, it was not surprising that parents overwhelmingly reported their child's teacher as being the provider of communication supports at school. Teachers who have not received any specific training in this area, however, flounder to provide communication interventions. Per the Sri Lankan Ministry of Education (2004) one of the key barriers to providing special education services is the lack of systematic procedures and trained teachers in the country (as cited in UNICEF ROSA, 2007). At the same time it is creditable that teachers attempt to meet children's communication needs.

Across all three provinces, inclusionary practices were relatively consistent. A majority of the time, children spent 100% of their day with other children with disabilities away from their typically developing peers. This practice is more in line with Soder's (1980) definition of "integration", which consists of placing a group of children with special needs in an ordinary school but not in the same regular education classroom (as cited in Lopez, 1999). Sri Lankan educators inaccurately use the term inclusive education; for example, the terms "inclusion" and "integration" are sometimes used synonymously (Singal, 2006). Therefore, although children with disabilities were permitted access to regular schools, a majority of the time they were placed in a self-contained classroom within the school. In spite of the documented benefits of inclusion in developed (Garrick-Duhaney & Salend, 2000; Kent-Walsh & Light, 2003), and LAMI countries (UNICEF, 2003), most children in this study continued to be separated from their typical peers. There were 10 students (15% of the sample) who were reported to receive education in inclusive education settings. Of these children, eight were classified as having only mild levels of disability and the remaining two had moderate levels of disability. Eight of these children either had a diagnosis of ASD or Down Syndrome. A majority of students included in regular education classrooms were typically in private schools. These children were included in the regular education classroom often with a "shadow teacher." The "shadow teacher" functioned essentially as a one-on-one para-professional, helping the student with his or her academic work and with transitions between classes. While shadow teachers appeared to be frequently used in private schools, government schools did not permit outside teachers into their buildings and did not have the resources to provide teaching assistants to function in this role. Therefore, there were limited opportunities for a child with a disability to experience supported learning in a general education classroom. As reported by a parent in this study, on the rare occasion a child with a disability was placed in a general education classroom, he or she was expected to be able to function with the help of the classroom teacher only, sometimes in classrooms with 35 to 40 regular education students. Kent-Walsh and Light (2003) reported that educational assistants are a crucial part of including students in general education classrooms; and thus many of these students lacked the support they needed.

Parents in Sri Lanka, like others across the globe (Yssel, Engelbrecht, Oswald, Eloff, & Swart, 2007), have reported benefits of inclusion, including children showing social and academic growth by being in the same classroom as their typical peers (Lopez, 1999). Currently, there are no truly inclusive educational facilities in the Northern province where children with special needs are educated in the same classrooms as their typically developing peers (Hettiarachchi, & Das, 2014). Although more than half of the parents in the Northern Province felt inclusion would be beneficial for their children, this percentage was fewer than parents who expressed this sentiment in the Western and Southern provinces. Therefore, the nature of the situation itself limits parents living in this province from experiencing inclusive education for their children. The north and east of Sri Lanka, until a few years ago was significantly impacted by an almost 30-year long civil war leaving the development in these areas far behind the rest of the country. In addition, parents in the Northern Province had lower educational levels compared to parents of the other two groups. All these factors, especially parents' limited exposure to inclusive educational settings, may contribute towards their less positive views regarding inclusion.

Some parents didn't think their children would be able to cope with being in the general education classroom, especially since some of their children had previously experienced education in the mainstream before being referred to schools that had special education services. For inclusive education to be successful, it should be implemented in a form that is a good fit for individual children and schools. Children with disabilities need to be supported in their learning environment (Furuta, 2006). An additional, essential factor is that teachers practicing inclusion need to be provided with continued guidance and support (Lopez, 1999).

Since 1986, there has been increased emphasis on the Regular Education Initiative (REI) in the United States, recommending that a majority of students with disabilities need to be served in regular education classrooms (Johnsen, 1994). However, some researchers have reported evidence of inclusion not being an appropriate solution in countries with depleted resources and a limited number of qualified teachers (Kalyanpur, 2011). Kalyanpur (2011) goes on to speculate that a more meaningful solution may be to find a middle path between international initiatives such as inclusive education and local realities in these countries. In contrast, successful inclusive education has been documented in LAMI countries such as Laos, where the key indicators to the success of this model were teacher training, increased awareness of the benefits of inclusion among communities, and establishing a link with local organizations and religious leaders who strongly influenced the community (UNICEF, 2003). Another important factor was the founding of local provincial implementation teams to provide on-going support to teachers and schools (UNICEF, 2003). This leads to question whether or not inclusive education is appropriate for a country like Sri Lanka. This question can be discussed using an Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) approach; EBP has been defined as the combination of the best and most current research, relevant stakeholder's perspectives and clinical/educational expertise, together facilitating effective decisions for direct stakeholders (Schlosser & Raghavendra, 2004). In relevance to Sri Lanka, research supports the benefits of inclusion in LAMI countries when implemented appropriately (UNICEF, 2003), and a majority of parents in the current study saw benefits to their children being included with typically developing children. Therefore, two of the three branches of evidence-based practice support inclusion in Sri Lanka. The third branch is based on professionals' experiences with inclusion and their views on it; this remains an area for further exploration.

Sri Lankan parents believe that teachers place "some emphasis" on teaching reading and writing to students with disabilities. However, parents across all three provinces stated that in some classrooms there was no emphasis on teaching literacy skills. In general, individuals with disabilities read significantly below grade level or at levels that are inconsistent with their chronological age, cognitive and linguistic abilities (Brewster, 2004). Almost all of the children in the current study were unable to read or needed assistance with reading. Reading and writing are complex skills to learn (Hetzroni, 2004). However, almost all parents in the study (98.5%) across all three provinces felt it was important that their children acquired at least some literacy skills. In addition, the general literacy rate in Sri Lanka (of individuals without disabilities) is 93.2% for males and 90.8% for females (Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 2012). These numbers are considered high for a South Asian country that is classified as being a LAMI country. Literacy is a skill valued by Sri Lankan society but not always shared with students with disabilities.

Educational Implications

The gap in services for children older than 14 years of age and young adults is a significant concern. For example, there is an age limit of 14 years imposed on the special education units in government schools. In addition, adult services for individuals with disabilities are extremely limited. There are no special education high school or transition services provided by the government. The lack of services for older school-age children and adults was a concern expressed by parents. Both government and private organizations should work collaboratively to provide appropriate services for adolescents, young adults, and adults with disabilities.

The significant lack of children who had severe mobility and communication impairments in schools across all three provinces was noteworthy. Schools should make accommodations so that the buildings are accessible by all children, even those with severe mobility needs. Teachers should receive appropriate training so they are better able to meet the needs of all children. There is an urgent need for more initiatives to increase community awareness of the importance of educating children with severe disabilities.

This research also shows the need for legislative and policy changes to include an allocation for Speech and Language Therapists to work in government schools. From a practical standpoint, there are only a limited number of Speech and Language Therapists in the country; therefore, the Ministry of Education in Sri Lanka should consider providing teachers training on communication supports and strategies that they can implement in their classrooms at least as a temporary solution.

In government regular schools, at present there was only one special education unit per school. If the number of educators and units in a school can be increased, then students can receive more supports. This would make current special education services even more effective in a pullout model of inclusion by resulting in more individualized, efficacious instruction and smaller student-to-teacher ratio. Additional supports may also lead to a combined services or full inclusion model.

Changes are required to better support children with disabilities who are being included in mainstream general education classrooms. Government schools should consider either providing the child with a shadow teacher or a teaching assistant, or at the least permitting the child's parent to function as support personnel in the classroom. If inclusive education is to be successful, the child must be adequately supported. The government of Sri Lanka should seek advice from other similar LAMI countries, such as Laos, which have been successful in implementing inclusive education. Adequate supports such as those reported in the Laos study (UNICEF, 2003) should be put into place.

In providing appropriate and satisfactory disability services, it is important to consider the individual with disabilities and his/her family, their views and perspectives on education or school, and broader society in general. This study investigated the views of parents, but the implications of this study can positively influence educational services for the individual, and can also have broader implications on legislature and policy changes that could impact society as well. This investigation contributes to the interdisciplinary scholarship of disability studies and its interaction with special education studies.

Limitations and future research

The results of this study provide readers with a glimpse of the current status of special education services in Sri Lanka. Caution should be taken when trying to generalize these results to Sri Lanka more broadly, as participants were representative only from three of nine provinces. However, considering the consistency of the findings, it is possible to speculate that the special education system in the rest of the country is similar. The interview nature of the surveys limited the number of participants from each province. In addition, multiple parents were interviewed whose children were in the same classroom or school so there were shared similarities.

Interpreters were used for all the survey interviews conducted in the Northern Province. Data collection can be restricted by the use of an interpreter (Lopez, 1999). Another limitation was that one of the survey questions was modified after the first 13 interviews conducted in the Western Province, although this did not cause any significant changes to the results of the study.

This research suggests areas for future research. There is an urgent need to develop and implement a suitable education system for older children and adults with disabilities. Future research should investigate services being implemented for this population in other countries and draw from them a service delivery model that is appropriate for Sri Lanka. Another area of exploration is the lack of students with severe disabilities in schools. Investigation into this issue is required to understand if these students are accessing special education services and, if not, the reasons why they are not. Examining the benefits and challenges of implementing inclusive education in LAMI countries is also important. Further research is required to evaluate teachers' perspectives on the special education system in Sri Lanka, as they are key stakeholders in the education system, and to consider student experiences and perspectives. Research applying an effective training model for teachers on communication supports and strategies that can be put into action in their classrooms is needed. It would also be important to consider parents' satisfaction with current special education services.

Conclusions

The issues being discussed in relation to educational supports and practices are not just specific to Sri Lankan parents: these are global issues that parents of children with disabilities address on a daily basis. It is imperative that educators take heed and listen to parents; they are key informants about their children's education (Soodak & Erwin, 1995). It is important to find out parents' views and concerns regarding current educational supports and practices to plan for future services to be more effective. In this study, for example, parents unanimously expressed a need for speech and language therapists to work in schools so their children with complex communication needs can receive appropriate communication services.

It is encouraging to see the growth that has taken place in the field of special education in Sri Lanka. Services have expanded to both urban and rural schools. However, it is critical to step back and evaluate current services, and to consider the needs identified through this study in order to further improve special education services so many more children will continue to benefit from it.

References

- Booth, T. & Ainscow, M. (2000). Index for inclusion: Developing learning and participation in schools. Retrieved from Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education website: http://www.eenet.org.uk/resources/docs/Index%20English.pdf

- Brewster, S. (2004). Insights from a social model of literacy and disability. Literacy, 38(1), 46-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0034-0472.2004.03801008.x

- Campbell, F.K. (2009). Disability, Legal Mobilisation and the Challenges of Capacity Building in Sri Lanka. In Banks, M.E., Gover, M.S., Kendall, E. & C.E. Marshall (Eds.), Insights from Across Fields and Around the World. (pp.111-128). Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Campbell, F. K. (2011). Geodisability Knowledge Production and International Norms: a Sri Lankan case study. Third World Quarterly, 32(8), 1455-1474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.604518

- Central Bank of Sri Lanka. (2012). Economic and Social statistics of Sri Lanka 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/10_pub/_docs/statistics/other/econ_&_ss_2012.pdf

- Dawson, E., Hollins, S., Mukongolwa, M., & Witchalls, A. (2003). Including disabled children in Africa. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(3), 153-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00472.x

- Eleweke, C. J., & Rodda, M. (2002). The challenge of enhancing inclusive education in developing countries. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 6(2), 113-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603110110067190

- Furuta, H. (2006). Present Status of Education of Children With Disabilities in Sri Lanka: Implications for Increasing Access to Education. The Japanese Journal of Special Education, 43(6), 555-565. Retrieved from http://ci.nii.ac.jp/els/110006786089.pdf?id=ART0008731613&type=pdf&lang=jp&host=cinii&order_no=&ppv_type=0&lang_sw=&no=1371309984&cp=

- Furuta, H. (2009). Responding to Educational Needs of Children with Disabilities: Care and Education in Special Pre-Schools in the North Western Province of Sri Lanka. Japanese Journal of Special Education, 46, (6), 457-471.

- Garrick Duhaney, L. M., & Salend, S. J. (2000). Parental Perceptions of Inclusive Educational Placements. Remedial and Special Education 21(2), 121-128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/074193250002100209

- Government of Sri Lanka (2013). Sri Lanka education information 2013. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.lk/english/images/Statistics/sri_lanka_education_information_2013.pdf

- Gronlund, A., Lim, N., & Larsson, H. (2010). Effective Use of Assistive Technologies for Inclusive Education in Developing Countries: Issues and challenges from two case studies. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology, 6(4), 5-26. Retrieved from http://www.editlib.org/p/42264

- Hettiarachchi, S., & Das, A. (2014). Perceptions of 'inclusion'and perceived preparedness among school teachers in Sri Lanka. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 143-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.003

- Hetzroni, O. (2002). Augmentative and alternative communication in Israel: results from a family survey. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18(4), 255-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07434610212331281341

- Hetzroni, O. (2004). AAC and literacy. Disability & Rehabilitation, 26(21-22), 1305-1312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638280412331280334

- Humphrey, N. (2008). Including pupils with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream schools. Support for learning, 23(1), 41-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9604.2007.00367.x

- Japan International Cooperation Agency Planning and Evaluation Department. (2002). Country Profile on Disability. Retrieved from World Bank wesbite: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DISABILITY/Resources/Regions/South%20Asia/JICA_SriLanka.pdf

- Johnsen, Susan. (1994). Parenting the Gifted: Examining the Inclusion Movement. Gifted Child Today, 17, 17-19.

- Kalyanpur, M. (2008). Equality, quality and quantity: challenges in inclusive education policy and service provision in India. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(3), 243-262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603110601103162

- Kalyanpur, M. (2011). Paradigm and paradox: Education for All and the inclusion of children with disabilities in Cambodia. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(10), 1053-1071. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.555069

- Kalyanpur, M., Harry, B., & Skrtic, T. (2000). Equity and advocacy expectations of culturally diverse families' participation in special education. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 47(2), 119-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713671106

- Kent-Walsh, J., & Light, J. (2003). General Education Teachers' Experiences with Inclusion of Students who use Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 19(2), 104-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0743461031000112043

- Lavine, J. (2010). Some thoughts from a "minortiy" mother on overepresentation in special education. Disability Studies Quarterly, (30), (2). http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v30i2.1238

- Leiter, V. (2004). Parental activism, professional dominance, and early childhood disability. Disability Studies Quarterly, (24), (2). http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v24i2.483

- Light, J. (1988). Interaction involving individuals using augmentative and alternative communication systems: State of the art and future directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 4(2), 66-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07434618812331274657

- Lindsay, G. & Dockrell, J. (2004). Parents' concerns about the needs of their children with language problems. The Journal of Special Education, 37(4), 225-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/00224669040370040201

- Lopez, I. (1999). Inclusive education. A New Phase of Special Education in Sri Lanka. Goteborg University. Retrieved from http://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/23003/1/gupea_2077_23003_1.pdf

- Marston, D. (1996). A comparison of inclusion only, pullout only, and combined service models for students with mild disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 30(2), 121-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002246699603000201

- Ministry of Human Resource Development, Education and Cultural Affairs. (2000). Education For All: National Action Plan. Retrieved from UNESCO website: http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/upload/Sri%20Lanka/Sri%20Lanka%20EFA%20NAP.pdf

- Ministry of Social Welfare. (2003). National Policy on Disability for Sri Lanka. Retrieved from World Bank website: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTSRILANKA/Resources/NatPolicyDisabilitySep2003srilanka1.pdf

- Rowland, C. (2011). Using the Communication Matrix to Assess Expressive Skills in Early Communicators. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 32(3), 190-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1525740110394651

- Salant, P., & Dillman, D. A. (1994). How to conduct your own survey. New York: Wiley.

- Schlosser, R. W., & Raghavendra, P. (2004). Evidence-Based Practice in Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 20(1), 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07434610310001621083

- Schober, M. F., & Conrad, F. G. (1997). Does conversational interviewing reduce survey measurement error? Public Opinion Quarterly, 576-602. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/2749568.pdf?acceptTC=true

- Singal, N. (2006). Inclusive Education in India: International concept, national interpretation. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 53(3), 351-369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10349120600847797

- Soodak, L. C., & Erwin, E. J. (1995). Parents, Professionals, and Inclusive Education: A Call for Collaboration. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 6(3), 257-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s1532768xjepc0603_6

- Soto, G., Müller, E., Hunt, P., & Goetz, L. (2001). Critical issues in the inclusion of students who use augmentative and alternative communication: An educational team perspective. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 17(2), 62-72. Retrieved from http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/aac.17.2.62.72. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/aac.17.2.62.72

- The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). (2003). Inclusive Education Initiatives for Children with Disabilities: Lessons from The East Asia and Pacific Regions. Retrieved from UNICEF website: http://www.childinfo.org

- The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). (2009a). Childinfo: Monitoring the situation of children and women. Retrieved from UNICEF website: http://www.childinfo.org/disability_resources.html

- The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). (2009b). Mainstreaming child friendly schools in Sri Lanka: A case study. Retrieved from UNICEF website: http://www.unicef.org/education/files/CFSSriLankaCaseStudyJan2009.pdf

- United Nations Children's Fund Regional Office for South Asia (UNICEF ROSA). (2007). Social inclusion: Gender and equity in education SWAPS in South Asia. Retrieved from UNICEF website: http://www.unicef.org/rosa/Unicef_Rosa%28Srilanka_case_study%29.pdf

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2000). Human Development Report 2000. Retrieved from UNDP wesite: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2000

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (1990). Meeting Basic Learning Needs: A Vision for the 1990s. Retrieved from UNESCO website: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0009/000975/097552e.pdf

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). (2010). Disability at a Glance 2010: a Profile of 36 countries and areas in Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved from UNESCAP website: http://www.unescap.org/sdd/publications/disability/disability-at-a-glance-2010.pdf

- UN Washington Group on Disability Statistics (2006). Short set of questions on Disability. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/washington_group/wg_questions.htm

- World Bank. (2010). World Development Report 2010: Development and Climate Change. Retrieved from World Bank website: http://wdronline.worldbank.org/worldbank/a/c.html/world_development_report_2010/abstract/WB.978-0-8213-7987-5.abstract

- Yokotani, K. (2001). Promoting Inclusive Education in Neluwa, a Tea Plantation Area in Sri Lanka, through the Community Based Rehabilitation Programme. (Unpublished master's thesis) University of Sussex.

- Yssel, N., Engelbrecht, P., Oswald, M. M., Eloff, I., & Swart, E. (2007). Views of Inclusion A comparative study of Parents' perceptions in South Africa and the United States. Remedial and Special Education, 28(6), 356-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/07419325070280060501

Appendix

| Table 1 | |||||||||||

| Children's Demographics | |||||||||||

| WP | SP | NP | Overall | ||||||||

| mean | median | mean | median | mean | median | mean | median | ||||

| Age | 10.12 | 8 | 9.91 | 10 | 10.42 | 11 | 10.12 | 10 | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Female | 7 | 28% | 8 | 34.8% | 9 | 47.4% | 24 | 36% | |||

| Male | 18 | 72% | 15 | 65.2% | 10 | 52.6% | 43 | 64% | |||

| Diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | 6 | 24% | 1 | 4.3% | 0 | 0% | 7 | 10% | |||

| Down Syndrome | 9 | 36% | 10 | 43.5% | 7 | 36.8% | 26 | 39% | |||

| Cerebral Palsy | 2 | 8% | 2 | 8.7% | 4 | 21.1% | 8 | 12% | |||

| Develop- mental Delay | 1 | 4% | 4 | 17.4% | 3 | 15.8% | 8 | 12% | |||

| ADHD | 1 | 4% | 2 | 8.7% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 5% | |||

| Other | 1 | 4% | 3 | 13% | 2 | 10.5% | 6 | 9% | |||

| Dual Diagnosis | 5 | 20% | 1 | 4.3% | 3 | 15.8% | 9 | 13% | |||

| Severity | |||||||||||

| Mild | 16 | 64% | 14 | 60.9% | 5 | 26.3% | 35 | 52% | |||

| Moderate | 8 | 32% | 8 | 34.8% | 12 | 63.2% | 28 | 42% | |||

| Severe | 1 | 4% | 1 | 4.3% | 2 | 10.5% | 4 | 6% | |||

| Table 2 | |||||||||||

| Children's Traits | |||||||||||

| WP | SP | NP | Overall | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | ||||

| Ambulation | |||||||||||

| Independent | 22 | 88% | 22 | 95.7% | 16 | 84.2% | 60 | 89% | |||

| Needs assistance | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 10.5% | 4 | 6% | |||

| Wheelchair | 1 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5.3% | 2 | 3% | |||

| Writing | |||||||||||

| Independent | 18 | 72% | 21 | 91.4% | 19 | 100% | 58 | 86% | |||

| Needs assistance | 5 | 20% | 1 | 4.3% | 0 | 0% | 6 | 9% | |||

| Unable to write | 2 | 8% | 1 | 4.3% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 4% | |||

| Speech intelligibility | |||||||||||

| 100% | 10 | 40% | 8 | 34.8% | 11 | 57.8% | 29 | 43% | |||

| 50%-100% | 15 | 60% | 14 | 60.9% | 7 | 36.9% | 36 | 54% | |||

| <50% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4.3% | 1 | 5.3% | 2 | 3% | |||

| People you wish your child could communicate with | |||||||||||

| Extended Family | 0 | 0% | 2 | 8.7% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 3% | |||

| Peers | 5 | 20% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 10.5% | 7 | 10% | |||

| Multiple People | 2 | 8% | 4 | 17.4% | 1 | 5.3% | 7 | 10% | |||

| None | 18 | 72% | 16 | 69.6% | 16 | 84.2% | 50 | 75% | |||

Figure 1. Children's communication levels across all three provinces.

Audio Description: The pie chart of children's communication levels across all three provinces indicates that many of the children across all three provinces were classified as being at either level VI-Abstract Symbols (32.8%, n=22) or level VII-Language (58.2%, n=31). Level VI indicates that the child is starting to use single words (signs or pictures) to communicate and at level VII the child is beginning to combine two to three symbols (words, signs or pictures) to communicate (Rowland, 2011). There were no children in the sample who were reported to be early beginning communicators.

Figure 2. Children's classroom placements across all three provinces.

Audio Description: The pie chart of children's classroom placements indicated that across all three provinces, 58.2% (n=39) of children with disabilities were educated in regular government schools. Overall 49.2% (n=33) of children were placed in one special unit (self-contained classroom) regardless of their age or abilities. Significantly few children (25%, n=16) were placed in classrooms based on their skills and abilities (Figure 2). Of the sample 17% (n=11) were placed in a classroom that was K-3rd grade, and 9% (n=7) were placed in a classroom that was 4th-8th grade.

Figure 3. Academic inclusion with typically developing peers.

Audio Description: The bar graph of academic inclusion with typically developing peers indicated that an overwhelming majority (81%, n=54) of parents reported that their children were most often in segregated classrooms exclusively for children with disabilities (Figure 3). Some parents reported their children spent time with both typically developing and children with disabilities (6%, n=4). Few parents reported their children spent time with just typically developing peers (13%, n=9). Corresponding to the number of children in segregated classrooms, 81% (n=54) of parents stated that their children spend 0% of the school day with typically developing children.