Deaf academics who navigate aspects of their professional lives through signed language interpreting services face a range of issues, including handling perceptions of their Hearing peers, identifying and negotiating their own communication preferences, and balancing personal and professional relationships with their interpreters. Interpreters bring individual sets of schemas and skills to their work, which impacts the interpreted interaction. In this paper, a Deaf academic and her interpreter/colleague discuss various challenges in having an interpreter—and being an interpreter—in academia. Topics include being "outed" as a person with a disability because of the presence of an interpreter; the need for interpreters with specialized academic vocabulary; the responsibilities of the Deaf academic and the interpreter in interpreted interactions; and the sense of vulnerability, intimacy, and autonomy experienced by the Deaf academic and the interpreter. The article is a shared reflection about the evolution of a relationship, beginning with the authors' respective roles as client and interpreter, and leading into to their present alliance as colleagues and friends.

A growing number of Deaf 1 academics navigate various aspects of their professional lives via signed language interpreting services (Hauser & Hauser, 2008). If a Deaf academic and an interpreter work together for a period of time, they may develop a successful professional partnership based on trust and respect (Brooks, 2011). At the same time, they may also face issues of identity, power, and interdependence that need to be negotiated and resolved, a process fostered by self-reflection and shared dialogue. Drawing on their experiences, the authors individually and collectively examine their approach to developing and sustaining their intellectual and interpersonal partnership as a Deaf academic and an interpreter. The discussion is grounded in the authors' distinct disciplines—philosophy and linguistics—and their respective specialties of bioethics and interpretation studies. Having graduated from separate doctoral programs at one university, the authors now find themselves as faculty colleagues at another university, with the opportunity to reflect on their journey in the academic world. By turns, they examine their complementary relationship as recipient and provider of interpreting services and ultimately, as academic colleagues. In their discussion, they consider philosophical, linguistic, and ethical questions surrounding interpreted interactions. Their conversation builds throughout the paper as they raise sensitive issues that arise in their professional partnership, concluding with three pervasive "tensions"—vulnerability, intimacy, and autonomy—in their association. This article is offered as a "conversation in progress" about the individual positions and shared engagement in their academic journey.

Teresa — My "Coming Out"

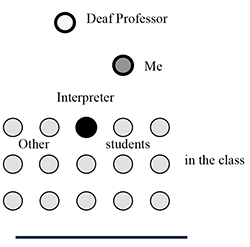

I am a latecomer to interpreting services—as a mainstreamed hard of hearing child, I did not use an interpreter until I entered college. My first encounter with a signed language interpreter was unusual: out of curiosity, I signed up for a Deaf Studies course taught by a Deaf professor. A sign language interpreter provided spoken English interpretation for the nonsigning hearing students. As is typical, the signed language interpreter sat in the front row of the classroom facing the Deaf instructor. Since I could not understand the interpreter's spoken interpretation without speech-reading her (I did not know much sign language at that time), I sat midway between the professor and my classmates, facing the interpreter and the hearing students (with the professor behind me) in order to speech-read her spoken interpretation (See Figure 1). I felt vulnerable sitting apart in this space physically separated from the other students. It was discouraging that in a class where I expected to be less marked as "other" given the topic, the seating arrangements for accessibility emphasized my disability in ways that I had never experienced with a hearing professor.

Figure 1. A schema of my first experience with an interpreter, which put me in an exposed and vulnerable position.

Aside from this bizarre experience, I did not work with interpreters for access to spoken information again until I became a graduate student. It wasn't until I experienced my first seminar in graduate school that I realized the limits of the speech-reading strategies I had honed as a mainstreamed student sitting in the front row of the classroom, eyes locked onto the professor's face as I scrawled notes across my neatly lined paper. The shift from small seminar courses at a women's college, with eight to ten students who deliberately took turns and drew in quiet classmates, to the aggressive "verbal brawling" of male-dominated graduate philosophy courses was an adjustment, to say the least. In order to speech-read, one must first locate the speaker, which most people do via listening, not looking. Measured seminar discourse with hand-raising, turn taking, and pauses to ensure that the speech-reader has made eye contact, is much more effective for speech-readers than discourse where impassioned speakers talk over one another in order to gain the floor (and one surmises, to assert dominance).

It immediately became obvious that I needed to make some quick decisions to gain access. I assumed that the solution to my communication access needs would be technology based. I would use CART providers 2 and an assistive listening device 3 to access classroom discourse and colloquia. I soon learned of geographical and technological limitations to these solutions: I lived in a state with few trained CART providers and the technical capabilities of conference microphones were simply inadequate.

The university's Office of Disabled Student Services grew exasperated with me as each effort to accommodate my hearing loss became unworkable. Finally, they offered me the last resort of accessing classroom communication through an "oral transliterator." 4 The horns of my dilemma were to either accept this "sub-standard" accommodation or give up my dream of becoming a philosopher. Grudgingly, I accepted, despite my reservations about oral interpreting. The art of speech-reading is constrained by the fact that many sounds look identical on the lips (e.g. "pat" and "bat"). Highly skilled speech-readers mentally rifle through possible options to determine what is most likely given the context; having a large English vocabulary to choose from is a plus. This mental selection process is coupled with the challenge of lag time—that is, of partially hearing sounds and keeping the sounds in mind long enough to match them with the corresponding visual appearance of the oral interpreter's mouth movements. Speech-reading an oral transliterator is a complicated mental task resulting in more work for the deaf or hard of hearing person than simply reading captions (in which errors are corrected by the captioner and not the consumer). Using an assistive listening device in conjunction with speech-reading the speaker can reduce the lag time problem, but is only workable if the sound quality is sufficiently good and if the deaf or hard of hearing person has residual hearing.

One benefit to working with an oral transliterator in class was having only one person to speech-read, rather than whipping my head in every direction to catch every student comment before it was completed. Once I became more comfortable with my transliterator, I asked him why he fidgeted so much while providing oral interpretation. He explained that he was also a sign language interpreter and found it hard not to sign while mouthing the words. I gave him permission to "add his hands," renewing my acquaintance with American Sign Language, which I had put on hold since my undergraduate days. In doing this, I had taken charge of the interpreting relationship for the first time.

The shift from using technology for access to working with another person to deliver the information was a sea change. As an FM assistive listening device user, I was anonymous; my behind-the-ear hearing aids have thumbnail-sized receivers at the bottom that transmit the speaker's voice from a lavaliere microphone. By opting to work with a transliterator, I moved from being a person with a more-or-less invisible disability to someone whose disability was publicly visible. 5 The aim was access; the unintended effect was attention. As a hard of hearing child, I had been schooled in how to 'pass' as a hearing person and not call attention to myself. As noted in my first encounter with an interpreter, attracting public awareness as a result of my disability left me feeling vulnerable and exposed. Oral transliterators are often less noticeable than signed language interpreters — people may not notice a person silently mouthing words, but it's hard not to notice a person whose arms and hands are constantly moving. Asking the oral transliterator to 'add his hands' became a public statement that moved me out of the hard of hearing closet into the signing deaf community. 6

In addition to the isolation of being the only deaf person in my program, working with an interpreter to gain access "outed" me as a person with a disability. Instead of having a fair amount of control regarding the choice of when to disclose my status as a person with a hearing loss, my cover was blown the minute I sat down in the classroom and faced the interpreter. As an undergraduate, I "passed" as a Hearing 7 person, made possible by hiding my hearing aids behind my long brown hair. One benefit of this was control over whether and when to disclose my hearing status. I had always chosen whether I would disclose my disability; in having this done for me, I felt as though my privacy and autonomy had been usurped. As a graduate student, I was publicly marked with a "scarlet D" (for Deaf) at the same time I began the process of becoming an academic philosopher.

The public nature of working with a signed language interpreter had unanticipated results. The first consequence was ironic: getting communication access to lectures led to increased isolation from my graduate school cohort. For the first time in my life, my fellow students seemed reluctant to approach me during breaks as well as before and after class. The presence of the working interpreter, coupled with my quiet nature in class, led many of them to think that communication with me would be a challenge, or at least, difficult to initiate. In addition to being hard of hearing/deaf, as an older graduate student with young children, I did not have much time to socialize with other graduate students. When I did socialize, I spent more time with doctoral students in the Linguistics Department, many of whom were my interpreters and others of whom were Deaf. Given that this department was a central meeting place on campus for people who signed, I felt that I was less of an oddity there than in the Philosophy Department, where no one signed.

The small numbers of Deaf Ph.D. students at my university made the isolated experience of graduate study even more solitary. In 2002, a group of international signing Deaf academics and graduate students convened at the University of Texas. 8 The Deaf linguistics professor at my university invited me to join her at this event and encouraged me to attend despite my misgivings that I was not sufficiently entrenched in the signing Deaf community.

This workshop changed my life in important ways. For the first time in my life, I met Deaf people who were interested in hanging out in libraries and talking about ideas. I met other Deaf doctoral students creating ASL lexicons of specialized terms in their disciplines and facing similar accessibility challenges. The people I met at the first Deaf Academics workshop became part of my scholarly community continuing to this day, even though only one of them worked in a philosophy-related discipline. In addition to finding a scholarly community, I also learned from two Deaf historians that I was part of the signing Deaf community, despite my reservations about my 'Hearing' ASL accent. These scholars took several steps to make sure that I had access at the workshop—as the only scholars working in the humanities, we formed a bond.

I'm often asked when I joined the signing Deaf community. For a number of reasons, this question strikes me as problematic. For one, those asking often assume that joining the signing Deaf community has an identifiable moment (or perhaps series of moments) in time, that joining the signing Deaf community implies a rejection of deaf and hard of hearing identities, and most problematic of all, that an identity and membership discourse is best suited for analyzing this way of being in the world. Although I have used the metaphor of exiting the hard of hearing closet, this should not be taken to mean that I have replaced my hard of hearing way of being in the world with a signing Deaf experience. Rather, I have not rejected or discarded my hard of hearing or (oral) deaf ways, but supplemented them with a signing Deaf persona and phenomenology. In short, the public move of learning visual language prompted other moves, including a more public identification as a hard of hearing person, a deaf person, and a (culturally) Deaf person. 9 In my view, one does not negate the other. 10

Fortunately, around this time, I became aware of another possible source for obtaining more highly qualified interpreters. 11 As luck would have it, the Philosophy Department and Linguistics Department were not only housed in the same building, but located on the same floor. The university's doctoral program in linguistics down the hall had a number of graduate students who were also experienced ASL-English interpreters. This group ultimately became the pool from which I drew most of my interpreters, and that was how I met Brenda.

Brenda — Forming a Relationship

I met Teresa when I accepted an assignment to interpret a graduate seminar titled "Philosophy of the Self" (little did we know that the course topic—the self—would foreshadow many of our future discussions). 12 The seminar was being offered at the same university where I was also enrolled as a doctoral student in the linguistics program. Teresa became aware of me as an interpreter and added my name to the short list of individuals she felt could interpret philosophy discourse and who understood the implicit curriculum of graduate school life (Campbell, Rohan, & Woodcock, 2008). At that time, I had worked as a professional interpreter for nearly 20 years, in hundreds of situations, and with a wide variety of Deaf people. When preparing for an assignment, interpreters naturally draw on the experiences and schemas they have developed over time and map them onto the present assignment. Using contextual information and our own assumptions about the world, interpreters rapidly anticipate patterns that may emerge during each language interaction. 13 Thus, I drew on my prior experiences to consider how I would work with Teresa.

I quickly recognized that Teresa was taking steps away from operating as an individual who had spent years, in her words, "passing as a Hearing person" and was moving towards a deeper affiliation with what is sometimes referred to as the Deaf-world (Lane, Hoffmeister, & Bahan, 1996). This situation was not new to me. In fact, ASL-English interpreters frequently work with emergent signers like Teresa because Deaf people acquire sign language at various points in their lives—they may have been deafened due to an accident or illness, they may have a progressive hearing loss and spoken language is no longer accessible, or they may have gone through educational systems that did not foster the use of sign language (Marschark, 2007; Marschark, Lange, & Albertini, 2002). Since 1974, federal legislation has made it possible for deaf children to be educated in their home schools, rather than being placed in residential schools specifically designed for deaf children. The number of deaf mainstreamed children now greatly outnumbers those enrolled in residential schools. One outcome of this shift is that mainstreamed deaf children often don't acquire sign language early in their lives, and only encounter ASL as adults. This phenomenon is so common that my initial meeting with Teresa was a very familiar one. In addition to acquiring ASL and learning to use an interpreter, Teresa was navigating another big challenge, that is, positioning herself as a serious doctoral student in a male-dominated discipline. It was not going to be easy for her, but one of the best aspects about being an interpreter is to play a small role as Deaf people achieve their goals, especially when the deck is stacked against them. Teresa was resolute in her goal, I was committed to her vision, and together we entered the classroom determined to make it work.

What are the responsibilities of the interpreter with emergent signers like Teresa? Are we interpreting or teaching ASL? Do we offer suggestions for using an interpreter, or wait to take their lead? When should we exercise more control, and when should we back away? While there is a body of research about the linguistic effects of late acquisition of sign languages (Emmorey & Corina, 1990; Mayberry, 1991/1993; Newport, 1988), little has been written about providing interpretation services to these individuals. Each emergent signer (in Teresa's case, an emergent "receiver" of signs) brings a unique set of language skills and impressions to the interpreted experience (Smith, 2012).

The emergent signer may also experience emotional undertones when using an interpreter for the first time. For example, some emergent signers are reluctant to use an interpreter at all, perhaps viewing them as unwelcome voyeurs into the world they have navigated alone for so long. For others who have "passed" as Hearing for most of their lives, an interpreter may represent a "failure," a belief fostered by years of implicit messages from parents, speech therapists, physicians, teachers, and scores of others who encouraged spoken language at all times. And for others, interpreters may evoke feelings of dependency, unwanted attention, or a sense of losing their coveted membership in the "Hearing world." To top it off, professional interpreters charge for their services, but rare is the organization that builds in an accessibility budget. The result? The Deaf individual is made to feel like a burden, while Hearing people can freely come and go.

To complicate things, emergent signers are often in flux about their own communication preferences, for example, they may wish to speak one day, while preferring to sign the next. They may tell the interpreter to always "sign in English" and later, demand ASL at all times. Emergent signers may feel friendly toward the interpreter at one moment, and within seconds feel embarrassment and irritation about using an interpreter. For example, when Teresa attends a social function such as a department party with an interpreter tagging along, she may at once feel as if she is babysitting an "annoying little sister," while simultaneously enjoying access to departmental banter and gossip that would have been missed otherwise (Campbell, Rohan, & Woodcock, 2008).

These shifting emotions put both the emergent signer and the interpreter in a vulnerable position with one another. As a long-time interpreter, I have worked with many emergent signers in my career and hold opinions based on those experiences; at the same time, it is important to remember that I, as a hearing person, can never fully understand the lived experience of being Deaf. We each bring our experiences, insights, and goals to the table. It takes self-awareness and patience to honor the process of learning how to communicate with one another (not to mention with Hearing people).

Speaking of Hearing people, they often bring many assumptions (usually wrong) about what it means to have an interpreter. Some uninformed people may view the interpreter as the Deaf individual's "personal representative." For example, when an interpreter asks a clarification question of the professor, either as preparation before class or during a class lecture, the professor may get the impression that it is being generated from the Deaf student, and may question the students' academic abilities. Some hearing people believe that the student and interpreter are long-time friends or family members and should be left on their own, a situation that can isolate the Deaf student. Other hearing people become fascinated with signed language, and pepper the interpreter with questions while ignoring the Deaf student. If these and other situations are not discussed and negotiated, the emergent signer may develop resentment towards interpreters.

Despite these obstacles, when an emergent signer recognizes that something has to change and an interpreter is accepted as a possible solution, a relationship is formed, for better or worse. What may not be anticipated is that the use of an interpreter can have ramifications beyond the control of both the interpreter and the person receiving services. This can leave both parties scrambling to manage situations as they arise in the moment. To exacerbate the situation, the interpreter and the emergent signer rarely have time to reflect on or discuss the situation. Once the classroom discourse begins, the chance for any conversation between the interpreter and the student abruptly ends in order to focus on the course content. Five minutes before or after class is not much time to anticipate what might happen in class, discuss preferences, and negotiate the terms of the day. Thus, the leap of faith required to use an interpreter is often just that—a leap into unknown territory, with no clear place to land.

Teresa — Going Public

Given that one of the standard assumptions of ethical norms is that they must be public, I began thinking about the public nature of being disabled. When one's disability is visible, people treat you differently. Appearing in public with a person whose job it is to provide access to you as a disabled person, adds another layer of complexity. Since I had not previously attended school with interpreters, I was at a loss when it came to figuring out how to work with them. As a grassroots activist in bioethics and disability advocacy, I was familiar with the patients' rights movement and People First, 14 where people who historically had little power were encouraged to recognize their rights in proactively shaping their own lives. I approached my interpreters with this attitude.

I assumed that interpreters would bring a wealth of knowledge about conducting a relationship with consumers of interpreting services. Since my experience was limited, I started by asking them questions. Practical questions were seemingly easy: "where should we sit?" was a frequent topic of discussion, until I realized that their default schema did not fit my needs. As someone who relied heavily on lip-reading, having the interpreter sit across the room meant that I would lose information contained in facial micro-muscle movement (Oyer & Frankman, 1976). Through trial and error, I learned what worked best was to position the interpreter three to four feet away from me, with my left ear oriented toward the speaker. With that arrangement, I could rely on my residual hearing to supplement what I was viewing.

Some of my other questions seemed to perplex the interpreters. For example, I asked "what are my duties as a consumer of interpreting services?" 15 As a philosophy graduate student studying applied ethics, this was an obvious question to ask for establishing a new professional relationship. I was flummoxed when interpreters were at a loss on how to respond to this question and, more puzzling, thought that my question was a rather odd one to ask! The idea that I would just "show up" and expect the interpreter to take full responsibility for the communication interaction was surprising to me; this was compounded by the fact that I was trying to assert myself as a Deaf woman of color in a field mostly populated by white Hearing men. I wanted communication access strategies to help me succeed in my role as a graduate student in philosophy, and I assumed that interpreters would be able to provide answers.

At some point, it also became clear that the dictum of interpreters to "match the consumer's language preference" wasn't well suited to someone like me, who was so new to interpretation that I didn't even know what to request. For example, philosophical discourse is heavily dependent on precision of words and word order. I assumed (wrongly) that interpreters who were doing transliteration 16 would convey every spoken word on their hands and lips. When a professor said, "if and only if," I assumed that the interpreter would reproduce this exactly, rather than reduce the phrase to "if," which has a very different meaning in philosophy. It took me several months to realize that I had to request a word-for-word English transliteration. There is also a lack of standardization in transliteration practices and my interpreters were not aware of the importance of reproducing philosophical conversations verbatim. That I was simultaneously learning the protocol for working with an interpreter while learning the norms of what it is to be an academic philosopher and bioethicist made this situation even more challenging.

When interpreters say they follow the preferences of the participants in the interpreted situation, for practical purposes, this usually means the preferences of the Deaf participant. Interpreters may assume that Deaf people have experience working with interpreters and know their own communication preferences. Included in the scope of information that ought to be provided to interpreters is the Deaf consumer's preference as to how the interpreter should manage communication. For example, under what circumstances do interpreters ask for clarification? What should interpreters do when the spoken delivery is too fast (summarize, switch to mouthing, tell the speaker to slow down, or follow some other consumer-directed preference)? What is the Deaf participant's preference regarding how the interpreter responds to questions directed at the interpreter? 17 Above all, who takes responsibility for all of these decisions? The interpreter is taught to both attend to the Deaf person's communication needs and to adopt the conventions of her profession. When the Deaf person has primary goals beyond the particular interpreted interaction, this can result in one kind of tension; when the Deaf person and the interpreter have different domains of professional expertise, this results in a different sort of tension. Both of these tensions deal with the issue of autonomy; who has the authority to make these decisions and the grounds of this authority will be discussed in a later section.

Brenda — Invisibility vs. Presence

Teresa writes of being "visibly disabled" for the first time in her life and the losses she felt because of the presence of an interpreter. Her feelings are understandable but unfortunately, may feed into a pervasive belief held by interpreters, that is, that interpreters should behave as if they are "invisible" in the interaction (but refuted in Metzger, 2002). For an emergent signer who is experiencing interpreters for the first time, the presence of an interpreter may be perceived as an intrusion. Imagine yourself in a situation in which a full-grown adult sits in front of you, moving her hands and body to convey a language that you may not fully understand, while drawing the stares of everyone in the room. Without question, the situation calls for sensitivity and discretion on the part of the interpreter; however, like it or not, the interpreter is present and is a very real part of the interaction. Historically, interpreter education programs and professional codes of ethics have taken a stance against any involvement by interpreters and further stipulated that all interpreted interactions must remain strictly "neutral." It is now acknowledged that while interpreters can be professional, they cannot, nor should even strive to, be neutral entities akin to machine translation (Metzger, 2002). While there are professional boundaries within interpreted interactions, there is more understanding that interpretation requires the involvement and expertise of all of the participants, including the interpreter (Nicodemus, Swabey, & Witter-Merithew, 2011).

With her presence, the interpreter establishes that she is in the setting to perform a particular function, which requires the need for involvement of all the participants. In Teresa's situation, she needed her interpreters to offer and discuss options about positioning, interacting with the interpreter, and explaining the role of the interpreter to the professor and other students. That her interpreters offered few options may reflect a well-intentioned but misguided belief that all choices lie with the Deaf participant and interpreters are functionally "invisible." Establishing a presence as the interpreter fosters opportunities for informed and transparent decision-making throughout the interaction with all of the participants. Achieving this requires interpreters to find and exercise "voice"—a competence that has been historically suppressed and discouraged (Nicodemus et al., 2011).

In the past (and still today), ASL-English interpreters have placed a strong value on autonomy of the Deaf client and, as a result, may say nothing when decisions must be made during an interpreted interaction. The underlying value is to promote self-advocacy of the Deaf client and avoid any hint of paternalism. Most interpreters receive little training on either interaction management or negotiating the conditions under which they work. They may operate in this manner without knowing that other approaches, for example, relational autonomy, 18 which acknowledges the relationship of all of the communication participants, could result in more transparent decision making in the interpreted interaction (Witter-Merithew et al., 2010).

This dilemma is illustrated in the example given by Teresa, in which she noted that she asked interpreters about the "duties" that she held as a participant in the interpreted interaction, and she was surprised when interpreters were perplexed by her question. Anecdotally, many interpreters report feeling responsible for all aspects of the interpreted communication, which may be further exacerbated by the "thou shalt not" approach that interpreters learn from interpreter educators, fellow colleagues, and the professional Code of Professional Conduct. 19 Interpreters may also experience conflict when trying to position themselves in relation to community norms with behaviors that feel in violation of professional codes of professional conduct. For example, an interpreter may share something personal about herself with the Deaf academic (information sharing is a norm in the Deaf community), but later question if a professional boundary has been crossed. To make progress in this area, interpreters may first need to recognize that interpretation is a socially constructed phenomenon in which all of the participants may have multiple relationships.

Ethical norms are a necessary component of any practice profession; however, a more holistic approach may be to view interpretation as a co-constructed linguistic experience that is developed by recognizing and fostering a relational approach with the communication participants. The ethical conduct of interpreters is a critical topic as evidenced by regular columns in professional newsletters, workshop trainings, and books on interpreter ethics. 20 At present, the focus is on the behaviors of the interpreters with little dialogue with the other participants in the communication. Though questions will continue to be raised about our respective duties in our partnership, the notion that it there is shared responsibilities is a move in the right direction. As interpreters, we should raise these questions directly with our consumers in an effort to be transparent in our decision-making. While we make ourselves vulnerable in hard discussions, they provide the opportunity for more authentic, and possibly more intimate, interactions. Fortunately, being both a consumer of interpreting services and a bioethicist, Teresa can help interpreters to frame the questions about our respective responsibilities during communication.

Teresa — Living the Questions

The Hearing participant in a signed interpreted communication situation is typically unaware of the complex factors that make accessing the information a reality or an exercise in pretense—for the interpreter as well as the Deaf participant. Interpreting scholars study how participants in interpreted communication interactions manage communication access; as a philosopher, I am interested in the answers to these questions as they shed light on the question that has hounded me for close to two decades: how should one live as a consumer of interpreting services?

As a consumer of signed language interpreting services and applied ethicist, I have often wondered about my obligations (ethical and otherwise) in interpreted interactions. It is clear to me from observation and personal experience that for the interpreter to perform her professional duties, she must be provided with information about the nature of the assignment (so that she can determine whether she has the language skills and background knowledge to interpret this context, as well as assess other factors that might be applicable). 21 Relevant interpersonal information is also likely to be helpful, such as sharing that a particular situation has the potential to become acrimonious, or that the Hearing member of the interpreted interaction may have an influence over the Deaf person's career in ways that are not immediately obvious. 22

Another responsibility of the Deaf consumer is to anticipate the kinds of interpreted interactions most likely to occur. For example, an interpreter working at a professional conference might interpret a keynote speech, a business meeting, a discussion with co-authors, a small special interest academic society meeting, paper and panel sessions, a formal awards luncheon, a happy hour, and a dinner meeting. Each of these interactions requires shifts in tone and language use.

The Deaf professional should also consider her responsibility to familiarize the interpreter about the jargon of her discipline. The number of Deaf professionals in some fields is very small (law, medicine, and religion are classic examples); indeed, in some fields the Deaf consumer may be a solitaire breaking ground in the profession. When there is no critical mass of Deaf professionals, there is no standardized ASL vocabulary for the interpreter to draw on. 23 As a result, the Deaf solitaire is tasked with generating such a vocabulary in order to obtain the necessary education that is the first step of professionalization. 24 The Deaf professional has few options: she may provide information about the terms in advance (signs, preference for fingerspelling, etc.), she may "feed" the interpreter signs throughout the assignment, or she may defer all decisions to the interpreter. Another consideration is the ability of the interpreter to interpret the content. Typically, an interpretation (versus a transliteration) requires that the interpreter comprehend the content sufficiently to make decisions about the choice of words and phrasing that preserves the meaning. The Deaf consumer has an ethical obligation to consider if requesting interpretation (rather than transliteration) is a practical possibility, given the nature of the assignment and the pool of interpreters who possess the requisite knowledge for interpretation. 25

Deaf professionals who find themselves in interpreted interactions that require a highly specialized vocabulary and background knowledge often put together a pool of interpreters they work with on a frequent basis. While this is highly beneficial in terms of creating continuity for standardizing technical vocabulary and increasing the interpreters' breadth of knowledge of the field, thus supporting a better work product, the bond in this professional relationship also raises "some uncomfortable realities" (Campbell, Rohan, & Woodcock, 2008, p. 102), including questions of vulnerability, intimacy, and autonomy. More specifically, placement of the deaf client can exacerbate feelings of vulnerability; intimacy can occur with interpreter witness to quasi-private learning moments typically confined to members of one's academic program (such as the deaf client's embarrassment of a botched argument objection); and struggles over vocabulary and meaning can often revolve around concerns about autonomy.

Brenda — Co-construction

As increasing numbers of Deaf people enter highly technical or professional work, close collaboration between the client and interpreter is becoming the new paradigm (Hauser & Hauser, 2008). In my own practice, I've interpreted for Deaf individuals pursuing pharmaceutical, chemical engineering, and architectural degrees, none of which are familiar disciplines to me. I've interpreted lengthy conversations about replacing car transmissions, football plays, and Japanese flower arranging, all without any knowledge of the specialized vocabulary, in either English or ASL. In the early days, I felt responsible to get the information right and thought I had to do it on my own. Deaf people exhibit patience with the requests for clarification and re-explanations, but one cannot help feel that a collaborative approach would have been more effective.

A relevant theory borrowed from linguistics and psychology is the notion of co-constructing communication, that is, actively working collaboratively with the participants in an interaction to create shared meanings (Burleson, Albrecht, & Sarason, 1994; Goldstein, 1999). In this framework, there is recognition that participants come together to build a message as partners. Co-construction is a distinctive approach, with emphasis on collaboration in an activity, which may simultaneously deepen the relationship and understanding between the partners. According to Vygotsky (1978), the construction of meaning takes place through interaction, both interpersonally as well as intra-personally. In this perspective, meaning is formed and shaped in dialogue with others as well as in dialogue with oneself. Bakhtin's (1986) concept of multi-voicedness illuminates this dialogic process. According to Bakhtin, each person appeals to multiple voices scripted from past interactions to construct meaning in any present encounter. These voices are constructed to form one's identity and position on issues being addressed. The reflective process is one way these voices are exposed. In well-intentioned efforts, interpreters may have fostered the belief in both Deaf and Hearing clients that we are fully responsible for the communicative interaction. In fact, it is a collective process between the Deaf and Hearing interlocutors as well as the interpreter.

That is not to say that interpreters don't have a special bond with the Deaf clients with whom they work. Most interpreters acknowledge their allegiance to the Deaf community while recognizing the impact of all of the participants in communication exchange. Our connection to the Deaf client can come out in subtle ways — a shared smile when a Hearing person asks, "Can Deaf people drive a car?", 26 the re-telling of important news within the Deaf community, or the sharing of valuable resources. Fortunately, it also comes out in the way that Teresa considered how to work with her interpreters and how she conceptualizes the task of interpreters. While there is a language acquisition process for emergent signers, perhaps there is also an "interpreter acquisition" process. In her process, Teresa considers her duties in interpreted interactions, which in turn, strengthens our proposition that the interpreted co-construction of meaning holds duties for all of the participants.

As Teresa moved beyond her student status into the realm of professional philosopher, she increasingly expressed her preferences for how she wanted to work with interpreters. She created an extensive written description about herself, her language use, and what she expects from interpreters. She provided details about how she wants to position herself within her profession and how interpreters can support those goals when working with her. Using this description, she has once again taken control and is guiding the process in which she and the interpreter form their working relationship—whether for an hour, for a day, or for many years to come.

Brenda and Teresa — Vulnerability, Intimacy, and Autonomy

In our conversations about constructing a partnership we recognized that the nature of interpreted interactions, where only the interpreter is privy to the full linguistic content, raises issues of vulnerability and autonomy. This is exacerbated by the intimate nature of visual language communication, which requires sustained eye contact, or gaze. The following section is an initial attempt to identify and unpack some of our questions and assumptions around each of these concepts, laying the groundwork for future inquiry. In our discussion about these concepts, we were struck by the difference in how our disciplines approach them. As a philosopher, Teresa was most concerned with defining these terms and providing conceptual clarification. As a scholar of interpretation studies, Brenda was most concerned about generating a working definition that could be used as a basis for practice. This is a familiar dilemma in applied ethics, where, unlike other areas of philosophy, the luxury of time to thoroughly explore an issue is constrained by the very real fact of persons living in a situation that is happening right now.

Vulnerability is the susceptibility to harm; in the case of interpreted interactions, this is typically psychological harm, which could include such things as having one's disability status "outed" outside of one's control. Vulnerability is closely connected to autonomy; if one is not able to make decisions for oneself, then one becomes more vulnerable to potential harm. While both the Deaf and Hearing participants in interpreted interactions are equally vulnerable in that they do not know what the other person is saying, and they have placed their trust in the professional interpreter to convey that information, the Deaf person is often more vulnerable than the Hearing person. Here's why: among Hearing people, the Deaf person is always at a disadvantage because of reduced access to auditory information. Publicly disseminated information, such as that delivered by news media is readily available in print or other visual formats, even if it is not accessible in American Sign Language. 27 Informal information is less usually less accessible; for the Deaf professional, "water cooler chat" is perhaps more important, e.g. for learning about office politics, career opportunities, and scuttlebutt about the profession. 28 Having less access to information makes the Deaf person vulnerable to opportunists and others who might take advantage of the Deaf person due to her lack of access to information.

One question to consider is the ways in which a Deaf person can be vulnerable in interpreted interactions, but perhaps a better question is to note the ways in which all parties in the interpreted interaction may be vulnerable. In other words, what sorts of harm might ensue in these kinds of situations? Harm can occur from misunderstanding, whether that is generated by misinterpretation or the deliberate decision to withhold or alter information. Violation of privacy is another harm, as is providing false information. The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) Code of Professional Conduct (CPC) addresses both these issues, but only for interpreters. 29 The latter could also apply to a Deaf person's behavior, such as a Deaf client spreading rumors in the Deaf community about an interpreter's unethical behavior. Mistrust can result when one person is vulnerable in ways that the other is not. For example, a Deaf professional may feel a sense of vulnerability regarding whether the interpreter is conveying her words in an appropriate professional register, but has few options to find out the quality of the interpretation that is being delivered. Some Deaf professionals choose to watch their interpreters very closely in an effort to speech-read and correct them. 30 Self-monitoring your own sign production as well as the mouthing of the interpreting is not only tiring, it also turns all of the attention back on the interpreter rather than the other conversational participants.

Another ethical issue is the question of intimacy, which we'll define 31 as a close relationship with another person. Interpreters are witness to many of people's most personal moments in life—receiving a diagnosis of breast cancer, the passing of an aged mother, the birth of a child. In these moments the interpreter experiences the tension between feelings of compassion and the need to remain detached in order to do the work. Interpreters and participants in an ongoing professional relationship can also become close. This is not unusual; professionals do become close to members of the population they serve — consider longstanding relationships between a physician and a patient with a chronic medical condition, or the lawyer monitoring a family trust.

An issue unique to the signed language interpreter is often unacknowledged: the intimacy of interpreted communication. Consider this: when using a visual language, the parties communicating must look at one another in order to engage in discourse. The nature and phenomenological experience of the gaze in conversational discourse differs from interpreted communication; the Deaf consumer is bound to maintain eye contact with the interpreter without the pauses and breaks that occur during a typical spoken conversational interaction. The intensity of the Deaf consumer's gaze is frequently matched by the interpreter's gaze. The purposes are different: the interpreter is attending to the Deaf consumer, checking for understanding, and also observing the whole environment; the Deaf consumer is focused on obtaining the message, and any other visual information that is relevant to this message. In the highly specialized professional world, the Deaf consumer must be ready to collaborate with the interpreter in creating the interpretation together. This collaboration need not require language to take effect; it may take place via exchanged gazes, just as might occur between spouses at a party or from a mother to her child, or other during other intimate relationships, such as longstanding friendships.

The final issue we examine is autonomy, which is the ability to make one's own decisions about one's life. Deaf people who work with interpreters are dependent on the interpreter for access to communication. The amount of interpreter-dependent content may vary, since information may also be conveyed through text or other visual means. Managing public perceptions of the Deaf person as a capable professional with the schema that the Deaf person is being "helped" by the interpreter is tricky. Establishing a relationship that respects the professionalism of the interpreter, who is in a newly emerging profession that is still shaping professional norms, with the autonomy of the Deaf professional, who may face some initial skepticism regarding her competence, is likely to require a dialogue about the assumptions and expectations of both the interpreter and Deaf professional. This presents something of a puzzle beyond the practical matter of when such a discussion might take place. If one of an interpreter's professional obligations is to support autonomous decision-making in the interpreted exchange, and another professional obligation is to provide a faithful rendering of the content of the message, these two obligations may conflict. For example, there may be times when the interpreter may privilege the need to support the Deaf participant's autonomy over the faithful rendering of the message. 32 But this move in itself appears to undercut the Deaf person's autonomy, which is the puzzle.

Autonomy in the context of the interpreted interaction is typically understood to mean that the Deaf person has the authority to make decisions herself. Given the historical model of interpreters as "helpers," and the history of Deaf people having little voice in Deaf/Hearing interactions about matters that concern them, autonomy is an important concept. But just what does it mean to be autonomous in an interpreted interaction?

As a Deaf person, part of the condition for autonomy is access to information. This information may be linguistic; it can also be environmental, which includes both visual and auditory content. For example, the Hearing person participating in the interpreted interaction can listen to the interpreter, but also take in information with her eyes. That is, she can observe the body language of the Deaf person who is expressing herself, she can observe other's responses to that expression or to other events taking place in the room. By contrast, in order to obtain the message, the Deaf person must look at the interpreter when the Hearing person is expressing herself. This imbalance of access to information has the potential to affect autonomy. One question is whether a person can be truly autonomous when access to information is constrained, not by the actions of the interpreter, but by the nature of the communication itself—that is, the visual mode of communication. Does the interpreter, as a proponent of the Deaf person's autonomy in interpreted interactions, have any responsibility to convey this additional information so that the Deaf person's autonomous choices are made with similar access to information as the Hearing person in the interpreted interaction has?

One must also examine the prosodic cues, or non-linguistic meanings, that are given during communication (Nicodemus, 2009). What meanings are conveyed when language comes via a shout versus a gentle voice, a clipped pace versus a cheery lilt? How is relevant information conveyed that leads to the most autonomy for the participants?

Pausing the Conversation

Pinpointing the exact starting point of a decade-long conversation is no easy task. Our conversation began tentatively, and was shaped in fits and starts; it is the result of a concerted and deliberate effort to construct a meaningful and respectful discourse about our roles as interpreter and consumer of interpreting services. One might say that the conversation began years ago when Brenda and Teresa entered the philosophy department seminar room and sussed each other out—Teresa looking to Brenda to provide guidance and interpreted content and Brenda looking to Teresa to assess who she was and how she wanted to express herself. Starting with the nuts and bolts of working together to create meaning in a particular setting, Brenda and Teresa took on the challenge of determining what to say and how to say it—creating a respectful bilingual dialogue about difficult topics that are rarely broached.

The fragments of conversation that we offer in this article come from our ongoing discourse. They touch on some of the internal realities of interpreters and consumers regarding vulnerability, intimacy, and autonomy. Ironically, we found that in our discussions about these issues, we again faced our own vulnerability, intimacy, and autonomy at the meta-level (i.e. interpreters don't share autonomous thoughts with consumers, deaf professionals don't acknowledge their vulnerability, and colleagues don't develop intimate professional [as opposed to personal] relationships). By framing these as matters for academic discourse, we gave ourselves permission not only to analyze these concepts as scholars, but also to openly address them as colleagues and friends. We have but paused the conversation; much remains to be said.

References

- Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. (V. W. McGee, Trans). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Burleson, B. R., Albrecht, T. L., & Sarason, I. G. (Eds.) (1994). Communication of social support: Messages, interactions, relationships, and community. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Brooks, B. A. (2011). It is still a hearing world: A phenomenological case study of deaf college students' experiences in academia. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Ohio University, Lancaster.

- Burke, T. B. (2007). Seeing philosophy: Deaf students and Deaf philosophers. Teaching Philosophy, 30(4), 443-51.

- Burke, T. B. (2004). An argument analysis of technology and deafness. Paper session presented at the Second International Deaf Academics and Researchers conference, Washington, DC.

- Burke, T. B. (forthcoming). Armchairs and stares: The privation of Deafness in (Deaf Gain anthology, Murray and Baumann). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Campbell, L., Rohan, M. J., & Woodcock, K. (2008). Academic and educational interpreting from the other side of the classroom: Working with deaf academics. In P. C. Hauser, K. L. Finch, & A. B. Hauser (Eds.) Deaf professionals and designated interpreters: A new paradigm (pp. 81-215). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Emmorey, K., & Corina, D. (1990). Lexical recognition in sign language: Effects of phonetic structure and morphology. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 71, 1227-1252.

- Goldstein, L. S. (1999). The relational zone: The role of caring relationships in the co-construction of mind. American Educational Research Journal, 36, 647-673.

- Hauser, A. B., & Hauser, P. C. (2008). The deaf professional-designated interpreter model. In P. C. Hauser, K. L. Finch, & A. B. Hauser (Eds.) Deaf professionals and designated interpreters: A new paradigm (pp. 3-21). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Lane, H., Hoffmeister, R., & Bahan, B. (1996). A journey into the Deaf-world. San Diego, CA: Dawn Sign Press.

- Mackenzie, C., & Stoljar, N. (Eds.) (2000). Relational autonomy: Feminist perspectives on autonomy, agency, and the social self. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Marschark, M. (2007). Raising and educating a deaf child: A comprehensive guide to the choices, controversies, and decisions faced by parents and educators. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Marschark, M., Lang, H. G., Albertini, J. A. (2002). Educating deaf students: From research to practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mason, I. (2006). On mutual accessibility of contextual assumptions in dialogue interpreting. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 359-373.

- Mayberry, R. I. (1991). The long-lasting advantage of learning sign language in childhood: Another look at the critical period for language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language, 30(4), 486-512.

- Mayberry, R. I. (1993). First-language acquisition after childhood differs from second-language acquisition. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 1258-1270.

- Metzger, M. (2002). Sign language interpreting: Deconstructing the myth of neutrality. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Newport, E. L. (1988). Constraints on learning and their role in language acquisition: Studies of the acquisition of American Sign Language. Language Sciences, 10(1), 147-172.

- Nicodemus, B. (2009). Prosodic markers and utterance boundaries in American Sign Language interpretation. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Nicodemus, B., Swabey, L., & Witter-Merithew, A. (2011). Establishing presence and role transparency in healthcare interpreting: A pedagogical approach for developing effective practice. Rivista di Psicolinguistica Applicata, 11(3), 69-83.

- Norcott, W. H. (1984). Oral interpreting: Principles and practices. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press.

- Oliva. G. (2002). Alone in the mainstream. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Oyer, H., & Frankmann, J. (1976). The aural rehabilitation process: A conceptual framework analysis. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (2005). Code of professional conduct. Retrieved from http://www.rid.org/ethics/code/index.cfm.

- Setton, R. (1999). Simultaneous interpretation: A cognitive-pragmatic analysis. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Smith, C. (2012, May 19). Interpreting for emergent signers: A preliminary study. Presentation given at Gallaudet University, Washington, DC.

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1986/1995). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Stewart, K. M., & Witter-Merithew, A. (2006). The dimensions of ethical decision-making: A guided exploration for interpreters. Burtonsville, MD: Sign Media, Inc.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Winston, E. A. (1989). Transliteration: What's the message? In C. Lucas (Ed.), Sociolinguistics of the Deaf community (pp.147-164). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Witter-Merithew, A., Johnson, L., & Nicodemus, B. (2010). Relational autonomy and decision latitude of ASL-English interpreters: Implications for interpreter education. Proceedings of the Seventeenth National Convention of the Conference of Interpreter Trainers. San Antonio, Texas.

Endnotes

-

We follow the standard academic convention of using uppercase "Deaf" to indicate the sociolinguistic signing community and lower case "deaf" to indicate the physiological condition of hearing loss.

Return to Text -

CART stands for Communication Access Realtime Translation. With CART, spoken language is immediately captioned for Deaf and hard of hearing individuals via a CART provider who types the spoken message verbatim into a stenotype machine. The resulting captions may be shown on a small screen read only by one person, or may be displayed on a large screen for groups.

Return to Text -

An assistive listening device (ALD) is used to enhance hearing ability for people in a variety of situations when hearing aids are not sufficient to access spoken language. The devices are used to amplify speech in a number of public settings (e.g. lecture halls, movie theaters, banks, hotels) or in private homes and cars. There are four types of assistive listening devices (FM, infrared, telecoil, and Bluetooth); all convey sound picked up by microphones to receivers worn by the person with a hearing loss. ALDs can also be used with earbuds.

Return to Text -

An oral transliterator, sometimes called an oral interpreter, silently mouths speech for the non-signing deaf or hard of hearing consumer. In addition, an oral transliterator may use facial expressions and gestures. This accessibility service benefits non-signing deaf people and hard of hearing people who rely on speech-reading (see Norcott, 1984). The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf offers an Oral Transliteration Certificate (OTC) for individuals working in this specialty (Retrieved from http://www.rid.org/education/testing/index.cfm/AID/88).

Return to Text -

The use of "disability" here is not without controversy. Some members of the signing Deaf community explicitly reject a "disability identity," preferring to solely identify "Deaf" as being a member of a linguistic minority group. I have argued elsewhere that positing this choice as whether one is disabled or Deaf neglects another option, that of the inclusive "or," which is both (see Burke, 2004).

Return to Text -

My process of identifying with the signing Deaf was gradual, and at this point, since I was using transliterated signed English and not ASL, I did not view myself as Deaf.

Return to Text -

In my paper "Armchairs and stares: The privation of deafness,", I argue that just as a distinction is made between lower case "deaf" and upper case "Deaf,", a parallel structure for distinguishing "hearing" as a physiological condition and "Hearing" as a sociocultural frame is necessary for concept and argument clarification (Burke, forthcoming).

Return to Text -

The Deaf in Academia Workshop, see http://www.deafacademics.org/conferences/index.php for details.

Return to Text -

These multiple ways of being perceived are not unlike my experience of being viewed as Arab-American or European-American, and the forced-choice question that implies one must prioritize one identity. The obvious disanalogy regarding the move from hard-of hearing to oral deaf status is frequently raised as an objection since ethnicity is often viewed as a fixed identity, but even here an interesting parallel surfaces in my family history, as witnessed by the shift from using "'Syrian"' to "'Lebanese-American"' to "'Arab-American.'"

Return to Text -

For more details, please see my unpublished paper draft, "Deaf: Identity, capability, phenomenology" (working title).

Return to Text -

In the mid-1990s, the office of Disabled Student Services at the university where I was enrolled began to recognize the need for specialized support services for Deaf, deaf and hard of hearing students and formed Deaf and Hard of Hearing Services.

Return to Text -

We are cognizant of disclosing a few specifics in this article about where and how we came to know one another. We carefully considered whether to include this information because certified interpreters adhere to a tenet of confidentiality in their Code of Professional Conduct (http://www.rid.org/ethics/code/index.cfm) and are mindful about sharing even seemingly innocuous details of their work. At the same time, we recognize the lack of open dialogue between interpreters and consumers regarding their personal and professional relationships with one another. Ultimately we decided that providing a few details was useful in framing our story and explaining our shared journey.

Return to Text -

See Mason (2006), Setton (1999), and Sperber & Wilson (1986/1995) for more on relevance, context, and pragmatics in language use.

Return to Text -

People First is a national self-help advocacy organization for people with developmental disabilities.

Return to Text -

The use of "duties" here is meant as an ordinary language term and not intended as a philosophical term.

Return to Text -

Transliteration is used to describe the process of mapping ASL signs onto English grammatical structure (see Winston, 1989).

Return to Text -

This question arises from my experiences at academic conferences. As a junior scholar I look forward to engaging in conversation with other philosophers, but my colleagues bypass me to ask the interpreters questions about sign language interpreting and the philosophical lexicon of ASL (which I constructed with the help of ASL linguists). It's frustrating to have the communication access available but to struggle to re-direct the conversation to philosophy itself.

Return to Text -

The concepts of relational autonomy put forth in MacKenzie and Stoljar's anthology (2000) stress the role of relatedness in individual's self-conception and interactions. This notion offers a provocative alternative to traditional models of the autonomous individual. Relational autonomy is currently being examined for its application to signed language interpreting (Witter-Merithew et al, 2010), but the concept is still under analysis in philosophical discussion.

Return to Text -

The national professional association for interpreters in the United States, the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, has an established Code of Professional Conduct, which is taught in all interpreter training programs and is an integral component of the certification process.

Return to Text -

Stewart and Witter-Merithew (2002) provide an excellent book on the topic.

Return to Text -

To use a graphic example, if an experienced medical interpreter is asked to interpret an autopsy, the interpreter would have the language skills and background (medical) knowledge, but it would also be relevant to include the fact that the interpreter will be interpreting a specific kind of medical event—an autopsy. The interpreter may have personal objections to the dissection of the human form, the interpreter may be squeamish, or the interpreter may have religious beliefs that conflict with this practice. Another bit of relevant information might be to fill in the interpreter on the politics of obtaining interpreting services. It may be the case that the Deaf professional has expended hours convincing or even threatening an organization to provide services; knowledge of this may be useful to the interpreter, should the interpreter have interactions with staff members from the organization paying for interpreting services.

Return to Text -

For example, in an interpreted interaction between two academic colleagues, one Deaf and one hearing, the interpreter may be unaware that even though the hearing colleague and the Deaf colleague work in different universities, the hearing colleague may be positioned to evaluate the Deaf colleague's work as a journal reviewer, or an external tenure reviewer.

Return to Text -

Mid-way through my M.A. program I learned of a philosophy doctoral student, Jim Haynes, who was working at Gallaudet University in the Philosophy and Religion Department. We established contact on line and began a dialogue about developing ASL signs for academic philosophy. Jim was the first Deaf philosopher that I met. Sadly, he passed away in 2004, during my first term at Gallaudet. Losing a colleague is never easy, but this loss was compounded by the fact that we had spent years looking forward to hours of philosophical discourse together as Deaf philosophers and colleagues.

Return to Text -

This is in itself an ethical issue that will not be addressed here. The construction of signed neologisms based on spoken language is a highly charged topic within the signing Deaf community that has roots in oppressive practices in deaf education (see Burke, 2007).

Return to Text -

A variant on this dilemma is frequently seen in student discussions about professors whose signing is not fluent or approaching native signing competency. Students often complain that priority is given to finding academics with Ph.D.s instead of people who sign well, not understanding that the Venn diagram intersection of people with Ph.D.s in anthropology and people who are fluent signers may be in the single digits; this is compounded by the lack of awareness that universities must satisfy accreditation requirements in order to continue to receive federal funding, and that not everyone in the group satisfying both conditions wants to live or work at a given campus.

Return to Text -

Hearing people frequently ask Deaf people if they can drive a car. This question is so frequently asked of Deaf people that jokes have arisen about it in the Deaf community. Recently, a Deaf friend sent me the following snappy comeback, "Yes, Deaf people can drive a car. In fact, I just ran over a Hearing person who asked me that question" (Janis Cole, personal communication).

Return to Text -

Deaf-blind individuals and deaf individuals with low vision often face compounded difficulties in accessing this content, since not all visual content is provided in accessible formats. The Twenty-first Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act is expected to address some of these issues, though this will not assist Deaf individuals who are not literate in English and prefer to use ASL to obtain information, or non-signing deaf or hard of hearing individuals who are not literate.

Return to Text -

Blogs and vlogs have contributed to the spread of informal information; the caution for the Deaf professional is to remember that these may not be reliable sources of information, and information may be incomplete. Accessibility is another issue; some blogs are private and require viewing approval by the owner, who acts as a gatekeeper for information.

Return to Text -

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Code of Professional Conduct. Retrieved from http://www.rid.org/ethics/code/index.cfm

Return to Text -

In Teresa's case, she made the decision to voice for herself, avoiding this particular issue.

Return to Text -

See Burke, forthcoming.

Return to Text -

As an example, Teresa recalls participating in a paper presentation panel at a conference Q & A session, in which another panelist used his Hearing privilege to speak over Teresa as she was answering questions. Since she was unable to hear that he was doing this, she was disadvantaged. Her interpreter stopped interpreting and used her voice and hands to communicate to Teresa that her spoken communication was drowned out by the panelist, and that the interpreter couldn't do her job under these conditions. Was this an instance of the interpreter attempting to obtain conditions in order to faithfully render the message? Or was it a decision to support Teresa's autonomy as a Deaf person? Or was the interpreter usurping Teresa's autonomy through her own action?

Return to Text