This paper addresses growing anxieties over the past two decades within media studies and visual art concerning the negative effects of technological sociality. Noting the recurrent use of the language of cognitive impairments—particularly that of autism—in appraisals of mediated relational deficits, this paper investigates the parallel production of ability and disability within privileged models of relationality and its aesthetics. Rather than attempting to police or restore valorized forms and practices of interpersonal exchange, I call for a more inclusive approach to relationality predicated upon a disability studies approach. Looking specifically to the Second Life performance works of Eva and Franco Mattes, I argue that technologically-produced social impairments can be productively approached as sites of alternative and adaptive relationalities.

In 1996, feminist media scholar Anne Balsamo made the following provocative statement: "Even as VR [virtual-reality] technology promises a new form of intersubjectivity, it contributes to a heretofore unknown epidemic of cultural autism." 1 This is surely a curious turn of phrase both today and within the rhetorical and historical context of Balsamo's argument. On the one hand, it may be tempting to dismiss such concerns as alarmist, overly-speculative, or ableist—VR has thus far failed to materialize its promised revolution in telecommunications, and even if it had there is surely something problematic in condemning a medium by way of analogies to a cognitive impairment. On the other hand, Balsamo's statement merits further consideration precisely because this conflation is so pervasive. From the rise of relational aesthetics in visual art to the frenetic discussions of the impoverishing sociality of social media within popular psychology and communication studies, much of these fields' debates and stakes seem driven by concerns over the deleterious effects of technological sociality. Throughout the histories of virtual technologies and its present, the specter of cognitive disabilities frequently serves as a dystopian symbol for the socially damaging effects of media. Thus it becomes important to ask: what, precisely, was "cultural autism" intended to mean and how did disability become a common metaphor for thinking through the relational effects of technology? What, moreover, is to be done about the enduring confluence between relational impairments, social ideals, and technology today?

This paper examines the legacy of "cultural autism" through two spheres: media criticism and visual art. It tracks the continued anxieties surrounding new forms of bodily and social telecommunications and their seeming correspondence to autistic relationality. Such a conflation, it claims, is not merely incidental.

Within media studies, this is a story of the difficult philosophical stakes of communicative ideals and the fraught defense of the body at a moment of its seeming abandonment. It is apparent, however, that in this process social impairments have been problematically trafficked as metaphors within a form of cultural critique that excluded (dis)ability as an analytic lens in its own right. Whether addressing virtual worlds, the Internet, or mobile technology, critical attention more often than not has continued to invoke an imagined whole from which technological tools subtract and disable through the displacement of bodily presence.

This is also the story of the rise of relational aesthetics as a definitive mode of artistic production and engagement at the turn of the millennium, and media art's resultantly fraught position in relation to the new primacy put on presence and open-ended social exchange. In celebrating the formal qualities of interpersonal contact, a tacit judgement concerning the form and content of authentic and restorative social relations can be found within the critical proponents of relational aesthetics. Excavating these assumptions through a disability studies approach helps recontextualize media art's historically troubled claims to legitimacy within this schema as well as the evident impossibility of relational art's own social ideals.

Both these histories meet in the work Eva and Franco Mattes: two artists creating performance pieces within the virtual world of Second Life. Depending on how these works are approached, the Mattes' seemingly satirical remobilizations of body and relational art gestures within a digital context either serve to confirm the fears congealed around the idea of "cultural autism," or alternatively challenge and expand its presumptions. In approaching these works in terms of the relational affordances of digital media, and in remobilizing the terms of relational aesthetics in a more inclusive light, the Mattes' Reenactments (2007-2010) and Synthetic Performances (2009-2010) can present a new perspective on digital communication as a site of both the pervasive failure of conventional relational language and perhaps the articulation of new, shared, and alternative engagements in inter-personal contact made possible through the very instrumentality of these failures. The "cultural autism of technology" in these works thus becomes a site of aesthetic and interpersonal innovation. Such a gesture could stand as an example for how to attend to different relational affordances and grammars between people and media without reference to a pre-technological authenticity or an imagined, abled, and Edenic whole.

In reflecting on the work of past and present critics, this paper seeks to ask more of the aesthetics and theorizing of social relations, and to demobilize the rhetorical weapons that have been forged around autism as a cultural trope while still attending to the parallels in bodies and affects that are engendered by technological mediations. The origin and the ongoing echo of Balsamo's words are worth returning to because, striped of their discriminatory sting, they are not fundamentally mistaken. There is something about telecommunications that is akin to autism—the suspension of proprioceptive and body language cues, the rearrangement of affective intensities, and new, at times challenging, deferrals of presence. It is the task of scholars working in these fields to approach this connection with compassionate curiosity, charting solidarities that could challenge the ableist legacy of impossible communicative ideals that are still so pervasively held.

I. Technology, Autism, and Media Criticism

First and foremost, Balsamo's words should be contextualized within her immediate scholarly concerns and her wider cultural surrounds. Technologies of the Gendered Body, the book from which this quote derives, is a part of a larger community of criticism responding to the popular vision of virtuality promoted by cyber-utopian journalists and virtual reality (VR) developers. In this promotional imagination new media stood to offer a profoundly disembodied experience of the world in which personal appearance and identity would be entirely malleable, presumably ushering in a social space free (or at least significantly removed from) gender, race, or class. 2 To this end, Balsamo contributed to a burgeoning literature of feminist and anti-racist media critique that sought to problematize the erasure of corporeal identity in virtual technologies, joining voices such as N. Katherine Hayles, Lisa Nakamura, and Wendy Chun, all of whom published books with similar political goals within short succession of one another. 3

Balsamo also wrote these words in the midst of the Internet's mass adoption, Wired magazine's rise to cultural prominence, and VR's brief-lived development bubble. This popular techno-libertarian consciousness informed and accompanied broader departures from identity politics and materialism within philosophy in the wake of post-structuralist, post-feminist and transhumanist reconsiderations of the security of bodily facticity. 4 For a corporeal feminist like Balsamo it was thus ever more essential to argue for the continual importance of embodied locations within technological systems and cultural representations.

Such socio-technological erasures, she argues, risk newly undermining the legitimacy of bodily claims to difference or oppression, ultimately serving the reproduction of hegemonic norms. 5 Paradoxically, however this defense of corporeal understanding and experience is articulated in such a way as to elide the legitimacy of cognitive and physical diversity. In this framework, autism serves as a metaphor for cyberculture's corporeal forgetfulness, a condition that Balsamo warns will culminate in an impoverishment of person-to-person intimacy and a troubled relationship with the body and its limits. "Cultural autism" seeks to express a socially and even physically amputated position through technology.

However, as media archaeologists and communications historians are quick to point out, such fears are not as wholly contemporary or unprecedented. John Durham Peters' genealogical investigation of the idea of communication reveals parallel tensions going back as far as the 1880s with the rise of new forms of disembodied technologies such as the photograph and telegram. 6 These early forms of incorporeal communication, divorced from the full range of embodied social nuance, were interpreted through the twinned anxieties of solipsism and telepathy for fear that modern media would either fail to provide meaningful social contact or wholly overwhelm the subjectivities of its participants through invasive, deterministic suggestion. This perceived dis- or over-abeling of media subjects, Peters argues, has led to well over a century of academic, popular, and cultural debate on the meaning of communication in the wake of these forms of bodily interruption. 7 Seen within a larger historical context of media criticism, Balsamo and her cohort's alarm may in part be the expression of a perennial concern rather than the pioneering appraisal of a wholly new new media. The novelty of their arguments, however, lies in the local political concerns of the authors and the evolving terrain of what bodily and cognitive ability can be said to mean in an era of greater stakes and pathological vocabularies for social normativity.

Autism's broad brush certainly provides a fertile space for suspicions and anxieties about the new. Its biological basis is poorly understood, such that its diagnosis is conducted purely through behavioral speculation. 8 A broad range of impairments fall into this criteria, including difficulties with social interaction, sensory management, ease of empathetic understanding, and engaging in varied behaviors or interests. 9 Though autism has more recently been conceived as a spectrum on which every individual is to some degree located, autism as a medically modeled clinical diagnosis is more specifically correlated with evidence of globally or locally diminished cognitive capacities, poor social integration, and an impaired ability in navigating reciprocal or emotive forms of communication. 10 Like a "bad media subject," Autistics are widely presumed to live in affective remoteness, defensively withdrawn from the vibrancy and vulnerability of "authentic" bodily and intersubjective contact. 11

Significantly, new media technologies and autism have grown together, emerging in force in the 1990s. Concurrent with the rise of the Internet was the beginning of autism's so-called epidemic, whereby the rate of autism's prevalence shot up dramatically, with estimates ranging from 2 to 5 individuals per 10,000 in the year 1980, to that of 120 individuals per 10,000 in 1999. 12 At the height of the seeming crisis there was a concerted attempt to locate the cause of autism through epidemiological models, searching for some manner of pervasive environmental cause. Whether through the hidden perils of vaccines, pesticides, or even excessive television use, autism was often figured as a direct consequence of the unprecedented ascent of estranging technologies within the western world. 13 Electronic and digital media as newcomers to a social landscape now in question were quickly associated with the condition. As Patrick McDonagh suggests, "autism anxiety" is an inseparable part of the condition's definition and discursive use, and can be seen to be distinctly on the rise. 14

Balsamo's use of the autistic analogy is particularly rich, as there is an evident hierarchy to the way that she imagines bodily communication and experience: an evaluation of certain kinds of technological embodiments and subjectivities, with autism serving as a negative model. By contrast, it follows that bare embodiment—the perhaps nostalgic meeting of bodies in space for physical connection and conversation—is the ideal against which VR falls short. When comparing the two, the virtual body definitely serves as the impaired and disabled foil to the presumed abled-bodied 'real' communicator. Not insignificantly, however, her description of what is objectionable in the technology troubles the extent to which her concept of "cultural autism" is to be read as merely a cultural analogy. Instead, Balsamo appears to have inadvertently discovered a bodily and social solidarity with autism through technology, and recoiled at the implications.

Stepping into the Sense8 World Tools VR system in order to conduct her study, Balsamo was immediately confronted with the "disconcerting effect" of the virtual environment's lack of proprioceptive clues. 15 Unable to draw from familiar spatial reasoning markers, much of the scholar's time in the system was devoted to simply orienting herself in the world. 16 In her writing, which draws heavily from popular anti-Cartesian critiques of the visual politics of photographic and film cameras, she condemns the comparative graphic and haptic deficits of her experience in VR as broadly representative of the technology's aspiration towards total disembodiment. 17 This leads the scholar to conclude,

Upon analyzing the 'lived' experience of virtual reality, I discovered that this conceptual denial of the body is accomplished through the material repression of the physical body. The phenomenological experience of cyberspace depends upon and in fact requires the willful repression of the material body [emphasis in original]. 18

In this understanding VR, by virtue of its restricted range of sensory information, enacts a transgression against the natural affordances of bare embodiment. In what is almost a Freudian invocation, Balsamo sees VR and its participants disguising and obliterating their bodily capacities as if they were an inconvenient fact or inappropriate urge. 19 This language, and the implicit binary construction at work between the natural body and its illegitimate distortions, suggests a moralizing principle at play in the text. The presumed disavowal of the materially lived body (the authentic one as the scare quotes in the above passage seem to imply) is a key component to unraveling the many valences of what the scholar means by VR's "cultural autism."

Though Balsamo may not have been aware, her proprioceptive difficulties in maneuvering through the Sense8 VR environment are in many ways analogous to the phenomenological experience of autism. As self-advocates report, a variable intensity of bodily sensation and sensory feedback complicate many Autistics' experiences of the world, making it difficult at times to locate their bodies in space or restrict common idiosyncratic movements that are often perceived as socially inappropriate. 20 The sensory experience of autism is diverse, equally encompassing vast differences in over- and under-stimulation from environmental and bodily cues. 21 Such bodies are not materially or willfully repressed, but are rather sensorially unpredictable and "noisy." 22 However, bodies that have been made phenomenologically dissonant or distorted through technology do not seem to qualify as such to Balsamo.

The argumentative logic of "cultural autism" has outlasted Balsamo's book and the media of its analysis. 23 As John Durham Peters has argued, autism seems to be "the 'it' disease for new media." 24 Popular science journalism abounds with claims that technology is "making us autistic." 25 Even still, the full implications of making this analogy, with its messy imbrication in medical and social models of ideal sociality, are rarely explored. 26

Sherry Turkle's 2011 book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other is a paradigmatic example of how the idea of "cultural autism" has been reworked to fit the contemporary mediascape. In her examination of the social use of diverse media such as Second Life, email, texting, and care work robotics Turkle contends that contemporary subjects are increasingly drawn to these technologies precisely because as they allow users to carefully control, measure, and predetermine the scope of social contact, thereby reducing the risks associated with spontaneous face-to-face sociality. 27 The results, she claims, is a loss in genuine human connection and an increase in psychologically harmful social isolation; "we are connected as we've never been connected before, and we seem to have damaged ourselves in the process." 28 Consequently, Turkle argues for a significant rethinking of the use of social technologies, perhaps even restricting their adoption, in order to ensure that social contact is sufficiently nourishing and properly humanizing. 29

In its discussion of mediated carework, this text explicitly and derogatively references autism. Warning against the kinds of damage robotic intimacy could bring, Turkle contends,

Human beings are capable of infinite combinations of vocal inflection and facial expression. It is from other people that we learn how to listen and bend to each other in conversation. Our eyes 'light up' with interest and 'darken' with passion or anxiety. We recognize, and are most comfortable with, other people who exhibit this fluidity. We recognize, and are less comfortable with, people—with autism or Asperger's syndrome—who do not exhibit it. The developmental implications of children taking robots as models are unknown, potentially disastrous. Humans need to be surrounded by human touch, faces, and voices. Humans need to be brought up by humans. 30

To this, one is tempted to ask, are Autistics not also human and deserving of parenthood? 31 Is Turkle aware of the ableist implications of comparing Autistics to robots? Her remarks, in describing a possible future of increasingly mediated communication, reaffirm a rigidly neurotypical ideal for what bodily communication is meant to constitute and what the inherent capacities of users of technology are or should be. This ideal enacts a very troubling exclusion of differently-abled subjects and concomitant communicative possibilities that may actually better facilitate relational exchanges for a diverse range of people.

How might these exclusionary models of media criticism be amended? Firstly, in mobilizing the cultural tropes of disabilities as negative models for technological relationality, critics presume the static and inherent nature of autistic impairments themselves. Disability studies scholars, conversely, have strongly contested the way in which sociality can be approached as a property of discrete individuals rather than the emergent outcome of a broader cultural sphere. 32 This stands to challenge much of the definitional presumptions communications scholars bring to their idea of communication. When face-to-face, affectively laden speech are no longer considered as the sole or privileged modes of exchange, Autistics enjoy vastly improved forms of social coordination, particularly when employing mediated communication tools such as a screen, pencil and paper, or a companion animal. 33 Similarly, the stigmatization of bodily tics and nonverbal utterances on the part of researchers and educators may rob Autistics of meaningful forms of volitional expression. 34 These advocacy efforts, focused on legitimizing difference rather than correcting deviations from the social and neurotypical ideal, have contributed to the political reach of autistic voices in the larger neurodiversity movement and stand significantly to invigorate the scope of communications research as such. 35

Autistic relationality has also, in many cases, flourished through the introduction of the personal computer, and this should bear weight on the role and direction of criticism within the field of media studies. Without the usual barriers to conversation posed by an expected proficiency with eye contact, body language, or emotive inflections to speech, tools such as Internet Relay Chat or blogging platforms can provide highly liberating outlets for some Autistics to communicate in ways that come more easily to their own expressive habits. 36 Virtual worlds in particular have also been a great inter-personal assistance for many Autistics in so far as all users, irrespective of their prior bodily and relational capacities, must newly negotiate social relations without recourse to nuanced body language or intense corporeal immediacy. 37 Consequently, Second Life, as the first mass-adopted and relatively free virtual environment, has been highly important for many Autistics around the world as an accessible platform for social and political organizing. 38 Without the expectation for eye contact, body language, emotive or even verbal speech, autistic users of Second Life often encounter a relational space that is far more adaptive to their own capacities. 39 The extent to which information technologies have enabled autistic individuals and communities to flourish stands to challenge broad claims for the primacy of bodily presence in human communication. Contrary to the implicit morality of Balsamo and Turkle's view of bodily repression, technologically-mediated communication could be said to be more 'natural' for Autistics.

Secondly, the legitimacy of the social ideals defended by media critics should be brought into greater scrutiny. Just as Fiona Campbell's early work posits the construction of a "corporeal standard" that is historically produced and defended ahistorically as a foundational part of being human, so too might "relational standards" be identified and taken to task for their exclusionary violences. 40 Indeed, as the preceding analysis reveals, there is a mutually constitutive relationship between physical and social ideals (as well as the bodily and cognitive disability tropes to which they are counterpoised). The demands made upon the body and its social performativity come to matter not only in their representations, but in the faith afforded to the politics of relationality's outward appearance. Consequently, the aesthetic dimensions of relationality, bodies, and technology also bear weight on the maintenance of standards. It is to this consideration that this paper now turns.

II. Relational Aesthetics and Abled Ideals

At the same time that cultural autism was first levied as an object of critical concern, visual art was simultaneously swept up in a complementary social imperative: that of relational aesthetics and art's potential to provide unmediated, even restorative, interpersonal exchange. Famously articulated by Nicolas Bourriaud, such artworks are said to take place in a context of increasingly limited and artificial social relations within Western society at large, following from late-capitalism's encroachment on public space and private lives and the relational limitations of electronic media. 41 It what may seem like the answer to Turkle's call for a technological retreat, Bourriaud champions relational art as a means of open and authentic social encounters. 42 By shifting the focus of artistic and formal merit from representations of the world to relations within it, Bourriaud contends that contemporary art has embarked on a new ethical and political project as well as a significant innovation within its larger history. 43

Crucially according to the critic, these reparative acts of interpersonal exchange (if they are to interrogate the role of technology within social relations at all) must occur outside of the media in question. Bourriaud's "law of relocation" claims that technology is most effectively addressed as a perceptual condition against which art must articulate counter relations rather than as an instrument through which art can materialize or aestheticize anew. 44 This claim, the culmination of an extended reflection on the parallel impacts of modern photography and contemporary computing in sensory and social habits, argues that the user-friendly screen of digital media has gained primacy as an omnipresent (and radically insufficient) model of sociality. 45 The best way to respond to the computer's pervasive sensory conditioning, Bourriaud therefore argues, is to articulate alternatives in the form of innovative and meaningful human exchange. As Bourriaud states, overly technological works are "[a]t best… just a symptom or gadget, or worse still, the representation of their own alienation from methods dictated by production." 46

Yet, in the context of the heightened stakes and anxieties around social and technological connectivity, the precise meaning or value of relationality within relational aesthetics remains significantly under-defined. This key concept, evocative of political and emotional communities yet without exact denotative criteria, merits further scrutiny. In Bourriaud's writing relational art is described quite broadly as "an art form where the substrate is formed by inter-subjectivity, and which takes being-together as a central theme." 47 Understood as a social interstice, relational art might be said to apply quite broadly and with countless historical antecedents. Being-together can take on numerous forms, and it is the formal qualities (qualities of taste, it could be argued) of these relations that define relational art as art, according to Bourriaud. 48 However, the critic's own law of relocation limits relational art's boundaries, or at the very least gestures towards what an ideal form of aesthetic relationality might constitute. This formal judgment on the part of relational aesthetics' pivotal thinker, rendered declaratively as law, underscores the process of how social exchanges that are celebrated as authentic or meaningful are made legible at the cost of other forms of sociality. At the root of this formal judgment is a model of behaviors and abilities to which all the participants of relational art seemingly should aspire. Rendering these formal expectations clear, however, requires an excavation of the tacit assumptions in Bourriaud's argument.

Firstly, as with Balsamo and Turkle's corporeal ideals, the vast majority of Bourriaud's paradigmatic examples of relational art revolve around deeply embodied relations. For example, Vanessa Beecroft's durational tableau vivants are composed of female models, identically coifed and groomed to an ideal image of femininity, made to hold strenuous poses within a space that viewers can only glimpse through rather than physically enter. The testing of the models' bodies, and the viewers' bodily desires and refusals towards the models, are a significant component to the aesthetics of the social relation figured therein. Meanwhile, Rirkrit Tiravanija's pad thai (1990) eschews even performative objects in lieu of the gustatory act of cooking and sharing a meal with his visitors. The artist's assumption of a care work role, and the audience's shared sensory experience of communal eating, forms a social bond that pivots around bodily need and pleasure. And yet, for all the corporeal focus of relational aesthetics, body art is scarcely mentioned by Bourriaud as either an antecedent to the movement or an active mode inherited and practiced by its performers. 49 Instead, the implicit ideal of technologically nude, embodied and active human contact goes unstated and unexamined, while nevertheless surely inflecting the critic's appraisal of the shortcomings of technologically-mediated art. If this understanding of relationality is specifically and virtuously humanistic, then it is a specific model of human bodily and social enactments that are being celebrated over others.

Secondly, strategies for the creation of collective meaning in mainstream relational art in large part depend upon the gregarious and exploratory social temperaments of the organizing artists and participating audience. Tino Sehgal's celebrated relational artwork This Progress (2010), for example, consisted only of a cadre of interpreters engaged in conversation with visitors ascending the ramp of the Guggenheim Museum. Many of the socially vigorous guides, who auditioned and were screened for the position to ensure their fit as appropriately outgoing and philosophically informed public interlocutors, nevertheless found the process to be emotionally exhausting at times. 50 As the guides each engaged with upwards of seventy visitors a day, some reportedly struggled with social overload and anxiety while work breaks rapidly became fiercely guarded moments of solitude. 51 Moreover, for all the visitors who delighted in the opportunity for open-ended conversation and intellectual connection, there were many others who found the experience to be bewildering in its artificial intimacy and risk of social rejection. 52 These aberrant moments of relational refusal or collapse are absent from celebratory accounts of the performance, which instead emphasize a restorative sense of genuine intimacy and emotionally uplifting ascent. 53 The social ideal of relational art, the extroverted participant willing to mingle and collaborate with strangers, proved to be an elusive and exhausting standard even for Sehgal's hand-picked interpreters.

This underlying supposition—that Bourriaud's wide-ranging assertions of relational art's formal and functional qualities rely upon some problematically exclusionary precepts—has been expressed in different ways in numerous criticisms of his writing. For one, the digital art community's opinion of the law of relocation is predictably low, contending that Bourriaud's delegitimation of technological art is tantamount to a form of "media injustice." 54 Critics such as Claire Bishop, moreover, have been keen to point out that relational art does not always model ethical or even politically hopeful interpersonal encounters, but may instead draw from avant-garde strategies of a willful antagonism or even provocative exploitation of its participants. 55 Similarly, from a museological perspective, Susie Scott et al.'s study of visitor negotiations with interactive art reveals that many participants experience a profound sense of unease with open-ended and socially-driven artworks, in stark contrast to Bourriaud's contention that relational art engenders psychologically reparative human connection. 56 Further still, artist Hennessey Youngman has levied heavy suspicions at the presumed ability of relational art to escape ongoing racialized and economic pressures within the contentious site of the art gallery. 57 The sum of these assertions suggests that relational art's promises of open sociality and political transformation, if indeed viable as a site of artistic and theoretical practice for some, are certainly not available to all.

In light of these criticisms, it becomes ever more apparent that Bourriaud's model and hopes for relational art are heavily predicated upon the restoration of its participants not merely to their lost natural propensities for social exchange, but also a heavily idealized conception of what authentic communication and bodily capacity are, both formally and ideologically. At the heart of such a construction is an intersectional bundle of privileges, making the ideal spectator a particularly convivial and bodily-abled subject, fully inured to risks of social violence or physical and socio-economic barriers to participation. 58 Technological experiments in failed relationality disturb this model, not merely because they represent a heavily mediated form of human contact, but more importantly because they radically refigure bodily and social terrains, frustrating the drive towards competency, authenticity, or completeness. It can be argued that these formal differences in the aesthetic qualities of failed and ideal relationalities—a preference for proxies over proximities and bodily prostheses over presence—do not nullify the relational potential in such exchanges, nor do they necessarily render such experiences inherently dehumanizing or alienating. By questioning the validity of claims for the specific formal properties of authentic or transformative sociality, it may be possible to reconsider wider anxieties around technological relationality.

Essential to such a challenge, and presently absent from current criticisms of relational aesthetics, are the theoretical and political insights of disability studies. Such a perspective draws much-needed attention to the scarcity of individuals who actually achieve the punishing model of ideal bodily or social facility that sets the standard for group participation, and the extent to which these ideals become the principal means by which failure is attributed and formal segregations are reified. Taking Bourriaud to task for the exclusionary standards within his model of ideal sociality thus stands to challenge similar assumptions at play in wider anxieties over technological sociality and the primacy of bare embodiment in social exchange.

The social model of disability maintains that social organization is principally responsible for the experience of disability, rather the medical or psychological impairments that frequently become legible as the cause of an individual's exclusion.59 As famously articulated by Britain's Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation:

We define impairment as lacking part or all of a limb, or having a defective limb, organ or mechanism of the body; and disability as the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by a contemporary social organization which takes no to little account of people who have physical impairments and thus excludes them from participation in the mainstream of social activities. 60

This definition might also be expanded and read in reverse: capacity can be understood as having limbs, organs, neurodevelopment, and technological tools that facilitate the performance of specific tasks whereas ability derives from the exercise of these capacities within social and built environments that support and encourage their use.

In the context of relational art, these capacities may include cultural capital, physically-abled bodies, and social networks that enable some viewers comfortably to participate in diverse social interstices and experience rewarding interpersonal exchange. Such capacities could be a prior knowledge of the history of the gaze politics that Beecroft's work invokes, or the societal prominence to secure an invitation to a Tiravanija meal in his collector's home and the conversational acumen to add to the night's atmosphere of social electrification. Ability derives from the exercise of these capacities in socially supported ways, through institutional and artistic structures that enable their participants to engage in stimulating relational exchanges. Relational aesthetics' political goals and emotional rewards are a particular property of this ability.

Impairments, conversely, may include but are not limited to social anxieties, cognitive and bodily difficulties of movement, speech, and perception within the built environment and a larger matrix of innumerably many socially stigmatized identities and practices. 61 Visitors may fail to achieve the restorative human connection promised in This Progress, for instance, if they lack the knowing willingness to play along with Sehgal's script or the confidence to challenge it in appropriate moments to better connect with the interpreters as people, rather than choreographed dialogs. 62

In short, the ideal model of relationality forwarded by Bourriaud and relational art in the mainstream is not universally accessible or inclusive. By constructing relationality narrowly, privileging corporeal presence and open-ended social experimentation, certain forms of sociality are made legible at the cost of others. The comfort and ease of engaging in reciprocal social exchange are highly determined by the expectations and supports offered in specific social environments, partially constructed by the artist and hosting institution and partially informed by larger theoretical investments in select formal qualities within relational art as a means of ameliorating larger political and social anxieties. As a consequence, it is all the more evident that the celebration of liberational models of sociality can quickly become a policing of its terms, serving ultimately to exclude creative social possibilities outside the dominant model of how intersubjectivity should properly appear.

The social model of disability argues that ability outcomes are highly relational; relational aesthetics, concordantly, can be viewed as a site not only for creative social experiments that model political possibilities, but also more deeply as structured situations in which capacities and impairments come to matter in the construction of social ability. It is in the creation and creative negotiations of social interstices that interpersonal exchanges are either made possible or foreclosed.

Such a perspective invites a far more measured outlook on the social impact and artistic possibilities of contemporary media. As much as the technological interface of telecommunications can inhibit the forms of corporeal presence and acuity emphasized in the canonical history of body and relational art, so too do these modes of idealized social and aesthetic exchange restrict explorations of alternative forms of social presence facilitated by technology. An alternative goal for relational art, therefore, would be to explore a plurality of relational models and modes of being-together in the hopes of striking new, perhaps even more inclusive horizons.

Having troubled the extent to which relational deviance can be taken as a straightforward product of disabled and technological subject positions, it remains to be seen how the aesthetics and communicative affordances of technology might be re-engaged. The following section attempts to take up this challenge by working through the digital performances of Eva and Franco Mattes, artists whose work has never been attended to as an example of relational aesthetics although it fills every criteria outside of the law of relocation. Using autism as an allied hermeneutic, this analysis attends to the local grammars of relationality within the Mattes' and Second Life's reconfiguration of communicative ideals.

III. Synthetic Relationality in the Performance Work of Eva and Franco Mattes

From 2007-2010, artists Eva and Franco Mattes staged a curious experiment in relationality. Using digital avatars, pre-determined animations, and computer-rendered props, the pair systematically restaged several of the most canonically important and physically demanding works of body art within the virtual environment of Second Life. In their original historical context these performance pieces represented a highly provocative challenge to long-held paradigms of spectatorship, requiring audiences to participate with the performer in creating social relations through an embodied negotiation with the artists' physicalities. The Mattes' virtual re-enactments, however, seemed designed to frustrate the very root of these gestures. By filtering the conditions and results of the work's participation through a heavy-handed technological interface, the stakes and outcomes of the performances were radically diminished, so much so that the virtual re-enactments seemed to verge on the point of parody.

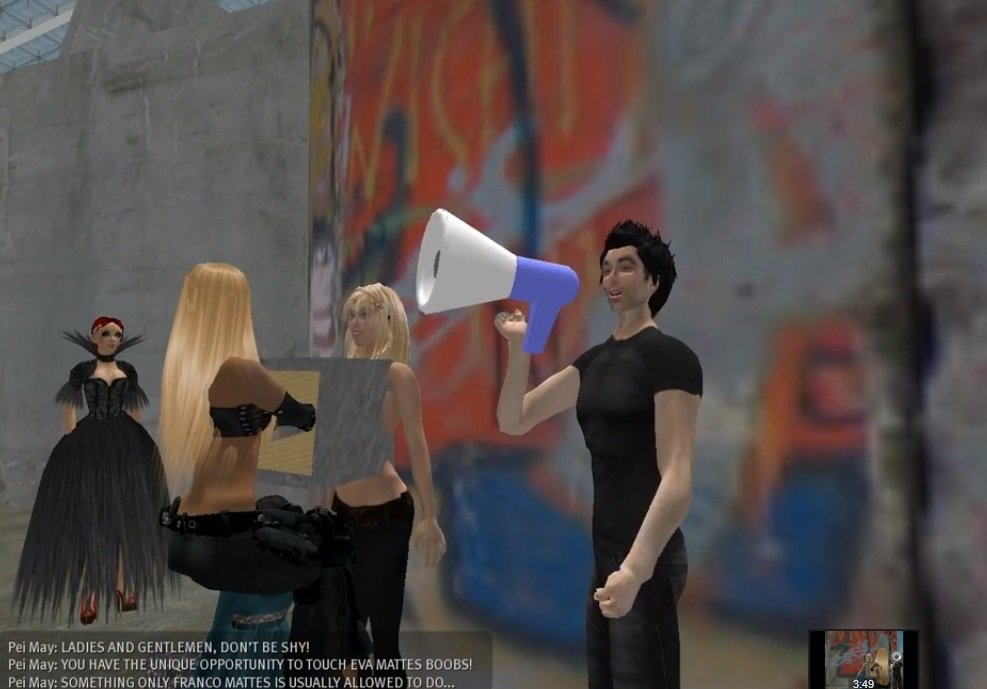

Comparing both sets of gestures—the historical performances and their virtual restaging—initially seems to confirm the primacy of the body that abounds in Balsamo's cultural autism or Bourriaud's relational aesthetic. In the original Tapp und Tastkino (1968-1971), for example, artist Valie Export invited audiences in ten different European cities to fondle her bare chest through a curtained theatrical maquette. The artist claimed that the proximity and candor of the exchange would serve to "activate the public" by flipping the usual sensory modes of engagement with the female body, as spectators were made to touch instead of look while facing the artist eye-to-eye in an intimate and reciprocal proximity. The charge of this bodily relation, however, was entirely lost in the move to virtual space. In the Mattes' version of Tapp und Tastkino (2010, fig. 1) avatar spectators and performers, maneuvering in the distant third-person perspective of Second Life's in-world cinematography, performed the gesture at significant remove and entirely without any haptic exchange. In the virtual arena of the re-enactments, technologically-mediated avatar bodies seemed to render the relational drive of these works impotent.

Yet, to arrest interpretation at this point of comparison would be to deny the emergent possibilities that stem from the different affordances of virtual bodies and worlds. While the Mattes' original intentions in creating the works were partially experimental and partially sardonic, they quickly became motivated by the intersecting capacities and limitations of Second Life, particularly in the ways in which its unrealistic modeling of real-world representations and physics create new modes of interaction. 63 As the performance series developed, "we realized that some of the best moments were software errors. For example, bodies were merging into one another… a 'videogame-native' performance should work on this and include software bugs." 64 Through this emphasis on Second Life's unique modes of interruption, the series evinces an interest that goes beyond mere satirical recontextualization. This investigation, instead, might be better understood as one of the ubiquity and unique affordances found in breaks from the communicative ideal.

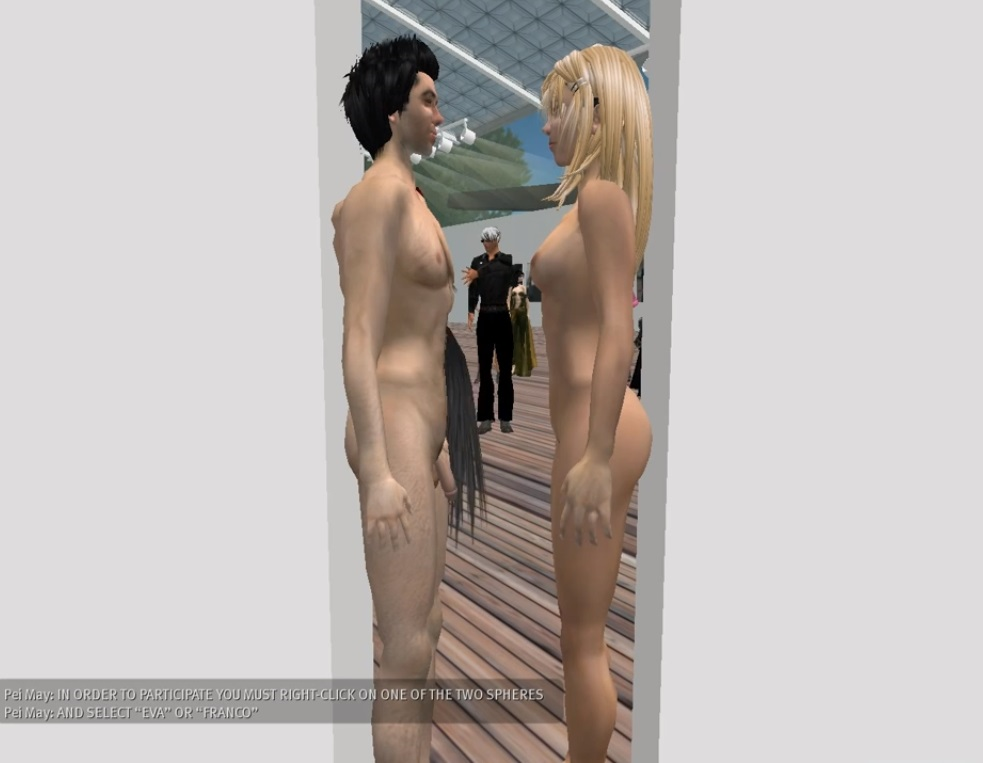

The re-enactment of Imponderabilia (2007, fig. 2), for example, clearly traffics in these punctuated interruptions of bodily norms. In Maria Abramovic and Ulay's original 1977 construction two performers stand nude in a standard sized doorway, significantly narrowing the passage in the process. The participating audience, if they wish to pass through the door and into the subsequent gallery, must turn their bodies sideways as they move past the performers, making a choice as to whose body (and what gender of body) they will face in so doing. The Mattes reproduced this embodied problem through a rudimentary form of interface design: participants, in order to pass through the doorway, had to click on one of two icons representing either artist. Having selected a preferred body to face, their avatars would subsequently be turned to the side and maneuvered through the doorway by a routinized and pre-programmed script. The visual result, however, revealed the extent to which bodies and objects in Second Life have rather easily exploitable boundaries and entirely fictive mass. The diverse range of avatars that participated in the re-enactment were often splayed in strange postures or otherwise too wide to realistically pass through the space between Franco and Eva without running aground of the artists or the wall against which they stood. Second Life's solution to such problems is to simply let objects overlap, cresting in and out of seemingly solid persons and things like a swimmer's stoke through water. The virtual Imponderabilia, consequently, rapidly became a site of jumbled and overlapping shapes as the participants' avatars swam through the performers and the environment in their crossing.

These interpenetrating objects and subjects, in addition to figuratively extending the forms of intimacy Abramovic and Ulay posed as a challenge to their historic participants, represented a present transgression to the decorum of the virtual world by interrupting Second Life's coherence as an illusory space. These visual glitches are generally considered to be poor practice in Second Life at large, as they disturb a sense of wholeness and identification many users experience with their avatars. 65 In the context of the artwork, however, these actions speak to a growing thematic intent in the series to push against these forms of social legibility in order to uncover new capacities for bodily presence and exchange within the technological platform.

Tapp und Tastkino is a willful culmination of this exploit. In designing the props for the performance, the Mattes' made a significant departure from Export's original chest maquette, which featured an elaborate velvet curtain and architectural embellishments in the style of a European theatre. Instead, the virtual maquette had a far more modern and industrial appearance, and the entry point into the renacted box was rendered as a small and singular triangle. Consequently, fitting both hands through the opening to access Eva's breasts would have been impossible outside of Second Life, but within the platform it guaranteed the overlap and interpenetration of avatar boundaries. Arms disappeared through seemingly solid material, entering not only the maquette, but also Eva's avatar body beyond it. The intimacy figured in this exchange is one of mutual proprioceptive confusion- a loss of the secure limits of the body and the expertise of movement. This itself figures a form of vulnerability not wholly dissimilar from the intimacy of the original's audience relations. Rather than Export's attempt to activate her spectators through a haptic address, the Mattes' turned to the fragmentation of identifications and visual logics as their social interstice.

On the one hand, it is easy to focus on the spectacle of these forms of visual breakdown. If the Mattes' exploits and overlaps are interpreted as intentional errors, then it is a relatively simple matter to evaluate the Reenactments in a Heideggerian or Kantian frame, as has become the norm for glitch art and other genres of contemporary electronic media art that traffic in noise and user unfriendliness. 66 By interrupting the ease and smoothness of the sensory modalities of technology, such artists are said to reveal the mediating work of previously invisible technologies and their concomitant ideologies. 67 There is also a distinct aesthetic pleasure in the complex and unpredictable forms of broken media, often equated to the gothic or the sublime. 68 Such interpretations, key to fostering creativity and critical recognition within contemporary media art, certainly adhere to parts of the Mattes' virtual performances. However, these analyses are deeply predicated upon a model of contemplative spectatorship that arguably ignores the active and relational qualities of participating in such art works and perhaps overly rely on the legibility of functional objects and their categorically different, broken derivatives.

Instead, drawing from the general ethos of disability studies, it may be productive to think of these fragmentary moments and bodies as constitutive of alternative sensory modalities rather than errors. The Mattes, by deliberately altering the bodily experience of the cited performance works to disorient their spectators, initiate an exploration of the limits and capacities of Second Life outside or only obliquely related to the virtual world's mimetic intent. Such attempts are not wholly intended to thrill, excite, or amuse, but are rather lab work of a different order, one that seeks to reinvigorated supposed failures with new productive possibilities.

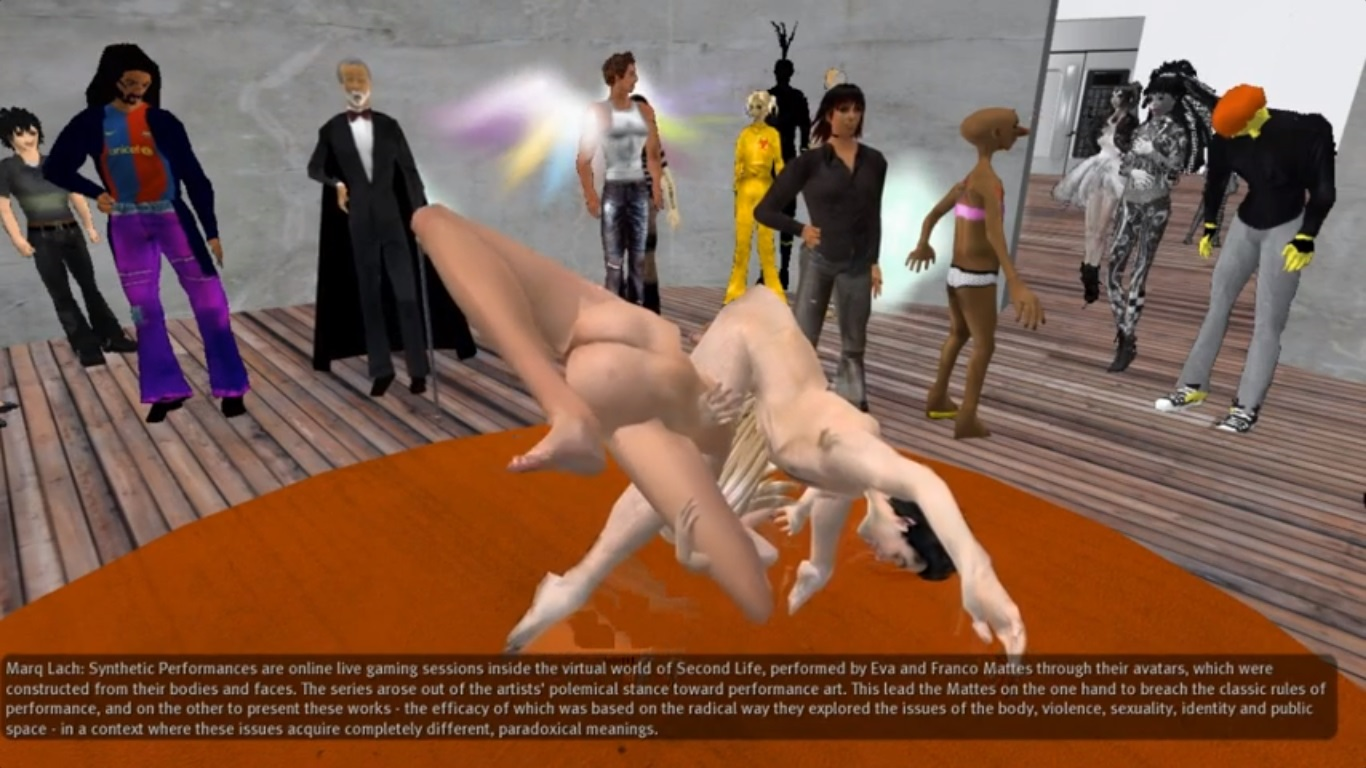

To this end, the visual vocabulary of Second Life exploits discovered in the Reenactments are continued and intensified in the pair's later Synthetic Performances (2009-2010). These works are unique in the Mattes' repertoire in that they lack any obvious historical appropriations or citations in form. Instead, they seem purely driven by a desire to explore the often awkward terrain of avatar bodies and alternative relational possibilities within the technological affordances of Second Life. They do so by pushing avatars into often uncomfortable and disorienting configurations, using the sensory modalities of bodily confusion as a starting point for a new form of sociality.

The first of the series, Medication Valse (fig. 3), seems to pick up where Tapp Und Taskino left off: engineering ways to frustrate Second Life's fictive cohesion and develop new modes of relating through virtual bodies. The work begins with Franco's nude avatar seated in an executive chair, bending slowly forwards and backwards until his shoulders seemingly disconnect from their sockets and his face and torso merge into and out of the furniture. The pace of his movements is steady and unhurried, while his face, when legible, looks serene. As he continues to rotate his virtual body parts twist and distort further, passing through one another as if knotting and unknotting. While each deformation seems more severe than the last, the rotations all end with his avatar in a resting position, proportions and ligatures more or less restored to the prior norm, before bending once again out of shape. These actions are accompanied by the calm and measured beat of a waltz, giving the performance a strangely decorous sensibility.

The piece's second act situates Eva and Franco's avatars floating parallel in midair, continuing the impossible folding and overlapping of body parts of the first section. There is a languid, balletic grace to the bodies' tempo and reach, disconcertingly in contrast with the deconstruction of their form. Some spectators, commenting in Second Life's chat client, note the aberration, positing that the deformations of the Mattes' avatars were the product of drugs, some sort of disease, or a "Second Life virus." 69 Others noted a distinctly erotic dimension to the meeting and mixing of the avatars' forms as they seem to fall apart and into one another. As one spectator quipped, "[t]hat's not in the Karma Sutra." The work culminates with a frenzied crescendo as first Franco's then Eva's avatars break from their stable orbit and increase the speed and torsion of their movements. Their bodies resultantly become more erratic and visually chaotic, strobing in their rapid flight from position to position. "Orgasm," announced another spectator.

As these comments suggest, Medication Valse can be interpreted through two distinct frames: an exposition of the body's seemingly ill derivatives or its extension into new intercorporeal possibilities. These connotations are also very much alive in the piece's title and soundtrack: a waltz written for use in the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975). In its cinematic context, the song serves as the nurses' cloyingly loud signal to residents of a mental institution to line up and receive their corrective medications. As the drama unfolds, however, the saccharine quality of the music takes on a sinister turn as the nurses' insistence on orderly behavior exacts its toll on the dignity and lives of the institution's patients. The Mattes' mobilization of the music in the context of their transitions through extreme bodily deformations and back again is thus ambiguous. Are they in the midst of a pharmacological dream, or do their errant bodies solicit an external drive for medical correction and ordering?

The work's technological appearances serve to emphasize the latter interpretation. The video documentation of the performance, a screen capture from Eva's point of view, is riddled with I-frame compression artifacts that further emphasize an aesthetic of fragmentation (fig. 4). Popularly known in glitch art circles as datamoshing, these artifacts can be identified by the momentary smudging of pixels across the screen following in the trail of a moving object—the Mattes' avatars in this case. 70 In the context of Medication Valse this suggests that the work was recorded, accidentally or intentionally, through a low-bandwidth connection, or that the data has been somehow damaged in the process of changing formats and being uploaded to youtube. In either case, these artifacts push the reading of the Mattes' avatars further, stressing the highly aesthetic qualities of disintegration and reformation, and foreshadowing the frenzied crescendo of the piece. These glitches suggest that the distorted nature of the performing bodies is not solely a property of the individual avatars, but rather belongs to the mechanics of the virtual world and the ways in which these bodies inhabit and move through space. There is, in short, something inherent to the mediality of being virtual under interrogation in the piece—something at odds with normative standards of corporeal ability and relational exchange. The work's formal qualities and its climax, moreover, while at times alarming in their flirtation with seeming violence to the body, also suggest the possibility for visual and relational pleasures, be it in Franco's singular explorations or his own virtual body or the pair's carnal embrace.

The subsequent Synthetic Performances open this proposition to spectator participation. I can't find myself either (2010) presents a "bed in" within Second Life, whereby audience members could join the Mattes' avatars lounging on an oversized mattress equipped with set animations, essentially staging a crudely animated sex party (fig. 5). While such endeavors are a major industry in Second Life as a whole, the performance soon frustrated any hopes for straightforward titillation. In the artists' own words, they enacted "what should have been an orgy but turned out to be a somehow ominous 3D-bodies-merging freak show." 71 As in their other works, the placement of bodies and pre-programmed animations within the artwork created a messy agglomeration of avatars and objects, proving the title's declaration. However, like the corporeal mergers figured in the Impoderabilia and Tapp und Taskino, there was a newfound intimacy—even pleasure—to this state of shared misperception.

In Bourriaud's terms, these artworks form a distinct social interstice. Their principle medium of sociality, however, is not typical bodies, conversation, or even proximity, but rather a mutual feeling of spatial confusion as participants' virtual surrogates flicker in and out of legibility. The sensual dimensions to this state are nevertheless still present, though through a new enactment. The sexuality of the work becomes unhinged from bodily objectification or mastery and instead finds its horizon in a shared indeterminacy. In this way the erotic becomes a manner in which moments of fragmentation are figured in a positive light while fragmentation in turn acts on eroticism, expanding its criteria and experience. Rather than an inwardly directed solipsism, this figuring of technological embodiment presents the disintegration of bodily coherence as a means for pleasurable relationality, outwardly directed into the environment and others.

This proposition is furthered in the last of the Synthetic Performances, entitled I know it's all a state of mind (2010). In the work the Mattes' avatars and those of their participants are animated in a variety of falling animations, tumbling to the floor and snapping back up again for a period of four hours (fig. 6). The avatars' inability to stay upright, with all its physical humor and pathetic repetitions, initially reads like a depressing piece of slapstick. However, the long duration of these bodily failures, their cyclical rhythm, and surprising variations in form, soon cause the action to lose its meaning over time until the dropping bodies no longer read as failed physical subjects but as dancers of a sort. As with the previous Synthetic Performances, the plummeting bodies collide and cohere to one another without resistance or reaction, forming conglomerate twins with distinct sexual connotations.

These repeated acts of falling are intercut with moments of spasmodic twitches, faces flickering through rapid nods and turns of the head, as well as recurrent rotations through overly emoted expressions of happiness, fear, concern, and anger. These bodily tics give the impression of a mental experience that is equally erratic as the physical stability of the avatar bodies, as if beset by inappropriate and cascading affects. The campy quality of Second Life's rendering of facial expressions, however, breathes doubt into the believability of these emotions, while their repetitions stress the limitations of the predetermined expressions in the pursuit of some form of authentic social exchange. Avatars, the work seems to expressly suggest, are significantly impaired in their capacities to emote or relate as normatively-abled bodily subjects. The Mattes' remixing of their limited vocabulary, however, reveals the lively alternatives that are otherwise elided in the pursuit of ideal relational capacities.

Perhaps one of the most striking moments in the performance comes when Franco's avatar interrupts his consecutive falls and twitches in order to sit on the floor, singularly rotating through a series of baroque facial expressions. Eva's avatar subsequently takes position directly behind Franco and also performs an inventory of emotions while falling directly on top of her partner's virtual body (fig. 7 and 8). These collisions, and the chimeric figures they form, present an image of relationality that is both strikingly intimate in its bodily proximities and highly distant in the seeming social disconnect between the two emoting avatars. Without any correspondence between their visible affects, one another, and their environment, the ersatz mental states of the avatars initially read as another form of inability, just like their bodies' failure to stay upright. The continued co-presence of the performers, however, despite the lack of obvious communication or reciprocal relations, nevertheless forms a kind of social connection in its own right. Though the performers do not directly face one another, outwardly communicate, or affect each other through their bodies, they still recognize one another's spatial presence and share a body language, even if that language's meaning is opaque or non-descriptive to the outsider.

Seen as a whole, there is a distinct kinship between the forms of fragmentary, indirect, and mediated relationality figured in the virtual performances and the specter of autism that has mirrored the bodily and social experience of new media forms in the eyes of their critics. The overly emoted facial expressions of I know it's all a state of mind are non-signifying, indicating a fundamental difficulty to effectively convey or read normative relational cues (the likes of which drives much of autistic social difficulties). The Mattes' avatars' jerky movements, moreover, could easily evoke autistic stimming gestures. The confusion engendered around the noisy boundaries and spatial locations of overlapping subjects and objects in the series further calls to mind the proprioceptive and sensory noise experienced by so-called low-functioning Autistics, as do the technical glitches in the video documentation. Purposely occupying an errant aesthetics of disorientation, the Mattes' artworks seem to enact a concerted autistic vocabulary.

As persuasive as these parallels may be, however, it is unlikely that a direct citation of autism or other culturally legible impairments were expressly intended by the artists. Their public commentary on their works avoids the topic of disability altogether and occasionally falls into a dualistic approach to the supposed mind/body split of virtual worlds. 72 Nevertheless, as the history of media criticism evinces, these questions are endemic to the experiences and discussions of new technology. Because the sensory and bodily affordances of virtual environments are inherently and obviously fragmentary and indirect, the medium calls to mind experiences of the body and the social that are broadly deemed to be broken, inadequate, or otherwise impaired. Accidental or inevitable, the Mattes' investigations of the relational potential of Second Life thus provide a revisionist outlook on the ongoing history of the cultural autism of media.

IV. Conclusion

As a result of this consonant intersection between inherent and mediated impairments, disability studies provides a powerful tool with which to intervene in both popular appraisals of media and contemporary art. 73 This body/these bodies of theory and activism stands to challenge persistent beliefs in modes of ideal communication while also illustrating the validity of differently-abled forms of embodiment and exchange. The relational standard of direct, face-to-face social presence is decidedly absent from the Mattes' artistic propositions. Nevertheless, like the autistic subject positions they evoke, these artworks elaborate alternative methods of being a body and being-together with others.

Within the intersections of disability studies and aesthetics, such spaces of possibility are encouragingly more and more under analysis. Ato Quayson, for example, has described moments of representational interruption as "aesthetic nervousness" in which the sensory experience of disability tropes cannot be solely contained within signifying regimes. 74 Such moments of sensory excess seem to contain the potential to bridge people with and without personal experiences of disability or disablement, as the validity of protocols and standards for ableist legibility often fail to adhere within the aesthetic presence of experience, mediated or otherwise. Anna Hickey-Moody has in many ways sought to push this concept even further through her study of the performing body as a site of affect and becoming. 75 Using a Deleuzian ethical framework, she has endeavored to re-center differentiation as the universal site of human experience and knowledge, thereby troubling the binary understandings of body/mind and abled/disabled that are continually pervasive in both critical and uncritical accounts of cognitive difference. 76

Such efforts have expanded the scholarly legitimacy of the aesthetic and the work it can be said to perform concerning the representational and affective structures of disability. What a parallel discussion of media and art stands to offer to this conversation is the insight that variable and often challenging intensities in affect and capacities can be cultivated through technology and are already part of the quotidian experience of contemporary life. As Eva and Franco Mattes' performance work and the wider history of media criticism suggests, aesthetic nervousness and becoming differentiations abound in mediated terrains, such that the distinctions between abled and disabled positions may only be legible after the fact, most visibly in the refusals marshaled around the concept of cultural autism and allied works of popular criticism. Corporeal and social standards are continually being undone within technology and art, affording experiential solidarities that can be mobilized against such refusals. To do so would mean to approach variable social affordances as contingently and socially produced, and thus a relational practice open to aesthetic and political renegotiation

Anne Pasek is a PhD student at NYU's Department of Media, Culture, and Communication. Her research focuses on the aesthetic, social, and political responses to technological failure. This research is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and Fulbright Canada.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to extend her gratitude to Christine Ross and Jonathan Sterne for their rich comments and support in drafting this article. Thanks also go out to Kirk Mitchell, Sarah Hamill, and the anonymous reviewers for their encouragement and feedback.

Bibliography

- American Psychiatric Association. "Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes." Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, D.C., 2013.

- Bagatell, Nancy. "From Cure to Community: Transforming Notions of Autism." Ethos 38, no. 1 (March 1, 2010): 33-55.

- Baker-Smith, Ben. "Datamoshing - The Beauty of Glitch." Bit_Synthesis, April 28, 2009. http://bitsynthesis.com/2009/04/tutorial-datamoshing-the-beauty-of-glitch/.

- Balsamo, Anne. Technologies of the Gendered Body: Reading Cyborg Women. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996.

- Barlow, John Perry. "Being in Nothingness Virtual Reality and the Pioneers of Cyberspace." Mundo 2000, 1990. https://w2.eff.org/Misc/Publications/John_Perry_Barlow/HTML/being_in_nothingness.html.

- Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London; New York: Verso Books, 2012.

- Boellstorff, Tom. Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Translated by Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods. Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2002.

- Bousteau, Fabrice. "L'extraordinaire Exposition de Tino Sehgal Au Guggenheim." Exhibit, no. 311 (May 2010): 82-89.

- Brincker, Maria, and Elizabeth B. Torres. "Noise from the Periphery in Autism." Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 7 (July 24, 2013).

- Bryant, Eric. "Tino Sehgal: Guggenheim Museum." Exhibit 109, no. 5 (April 2010): 114-114.

- Campbell, Fiona A. "Inciting Legal Fictions: Disability's Date with Ontology and the Ableist Body of Law." Griffith Law Review 10 (2001): 42-62.

- Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006.

- Clare, Eli. Exile & Pride: Disability, Queerness & Liberation. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2009.

- Collins, Lauren. "Primal Schmooze." The New Yorker, March 22, 2010. http://www.newyorker.com/talk/2010/03/22/100322ta_talk_collins.

- ———. "The Question Artist." New Yorker 88, no. 23 (August 6, 2012): 34-39. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/08/06/the-question-artist

- Cotter, Holland. "In the Naked Museum: Talking, Thinking, Encountering." The New York Times, February 1, 2010, sec. Art & Design. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/01/arts/design/01tino.html.

- Danilovic, Sandra. "Autism and Second Life - An Introduction." Journal on Developmental Disabilities 15, no. 3 (2010): 125-29.

- Davidson, Joyce. "Autistic Culture Online: Virtual Communication and Cultural Expression on the Spectrum." Social & Cultural Geography 9, no. 7 (November 2008): 791-806.

- Desantis, Alicia. "At the Guggenheim, the Art Walked Beside You, Asking Questions." The New York Times, March 13, 2010, sec. Arts / Art & Design. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/13/arts/design/13progress.html.

- Donnellan, Anne M., David A. Hill, and Martha R. Leary. "Rethinking Autism: Implications of Sensory and Movement Differences." Disability Studies Quarterly 30, no. 1 (March 12, 2009). http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/1060.

- Durham Peters, John. "Broadcasting and Schizophrenia." Media, Culture & Society 32, no. 123 (2010): 123-40.

- Eyal Gil. "For a Sociology of Expertise: The Social Origins of the Autism Epidemic." American Journal of Sociology 118, no. 4 (2013): 863-907.

- Fusar-Poli, P., M. Cortesi, S. Borgwardt, and P. Politi. "Second Life Virtual World: A Heaven for Autistic People?" Medical Hypotheses 71, no. 6 (December 2008): 980-81. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2008.07.024.

- Greenfield, Susan. Mind Change: How Digital Technologies Are Leaving Their Mark on Our Brains. Random House, 2015.

- Hainge, Greg. "Of Glitch and Men: The Place of the Human in the Successful Integration of Failure and Noise in the Digital Realm." Communication Theory 17, no. 1 (2007): 26-42.

- Hall, Alena. "Social Media Is Actually Making You Socially Awkward." The Huffington Post, June 19, 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/06/19/social-media-makes-you-socially-awkward_n_5512749.html.

- Hayles, Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. New York: Harper, 1962.

- Heim, Michael. "The Erotic Ontology of Cyberspace." In Reading Digital Culture, edited by David Trend, 70-86. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2001.

- Hickey-Moody, Anna. Unimaginable Bodies: Intellectual Disability, Performance and Becomings. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2009.

- Hickey-Moody, Anna, and Denise Wood. "Imagining Otherwise: Deleuze, Disability & Second Life." Presented at the ANZCA08: Power and Place, Wellington, July 2008.

- Hill, Elisabeth L., and Uta Frith. "Understanding Autism: Insights from Mind and Brain." Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 358, no. 1430 (February 28, 2003): 281-89.

- Isaksen, Jørn, Trond H. Diseth, Synnve Schjølberg, and Ola H. Skjeldal. "Autism Spectrum Disorders — Are They Really Epidemic?" European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 17, no. 4 (July 2013): 327-33.

- Johnson, Sue. "How Gadgets Ruin Relationships and Corrupt Emotions." Wired, February 14, 2014. http://www.wired.com/2014/02/gadgets-ruin-relationships-connection-illusion-one/.

- Jones, Amelia. "Chris Burden's Bridges, Relationality, and the Conceptual Body." In Chris Burden: Extreme Measures, 110-34. New York: New Museum, 2014.

- Kleban, Camilla, and Linda K. Kaye. "Psychosocial Impacts of Engaging in Second Life for Individuals with Physical Disabilities." Computers in Human Behavior 45 (April 2015): 59-68. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.004.

- Lanier, Jaron, and Adam Heilbrun. "A Portrait of the Young Visionary." Whole Earth Review, 1988. http://www.jaronlanier.com/vrint.html.

- Lasko-Harvill, Ann. "User Interface Devices for Virtual Reality as Technology for People with Disabilities." In Proceedings of the Second Annual Virtual Reality and Persons with Disabilities Conference, 59-65. Northridge: California State University, 1993.

- Malaby, Thomas M. Making Virtual Worlds: Linden Lab and Second Life. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009.

- Mattes, Franco and Eva, Orietta Berlanda, Julia Gwendolyn Schneider, Helen Stoilas, and Ana Finel Honigman. "Nothing Is Real, Everything Is Possible." 0100101110101101.org, 2007. http://0100101110101101.org/press/2007-07_Nothing_is_real.html.

- McDonagh, Patrick. "Autism and the Modern Identity: Autism Anxiety in Popular Film," Disability Studies Quarterly, 19 (1999): 184-91.

- Menkman, Rosa. The Glitch Moment(um). Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. http://issuu.com/instituteofnetworkcultures/docs/glitchmomentum

- Morin, Amy. "Is Technology Ruining Our Ability to Read Emotions? Study Says Yes." Forbes, August 26, 2014. http://www.forbes.com/sites/amymorin/2014/08/26/is-technology-ruining-our-ability-to-read-emotions-study-says-yes/.

- Murray, Stuart. Autism. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2012.

- Myer, Rob. "Glitch As Symbolic Form." Furtherfield, May 20, 2013. http://www.furtherfield.org/features/articles/glitch-symbolic-form.

- Nakamura, Lisa. Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Ochs, Elinor, and Olga Solomon. "Autistic Sociality." Ethos 38, no. 1 (2010): 69-92.

- Oliver, Michael. Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996.

- Perepa, Prithvi. "Cultural Basis of Social 'Deficits' in Autism Spectrum Disorders." European Journal of Special Needs Education 29, no. 3 (2014): 313-26.

- Peters, John Durham. Speaking Into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Quayson, Ato. Aesthetic Nervousness: Disability and the Crisis of Representation. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

- Scott, Susie, Tamsin Hinton-Smith, Vuokko Härmä, and Karl Broome. "Goffman in the Gallery: Interactive Art and Visitor Shyness." Symbolic Interaction 36, no. 4 (November 1, 2013): 417-38.

- ———. "The Reluctant Researcher: Shyness in the Field." Qualitative Research 12, no. 6 (2012): 715-34.

- Shanken, Edward A. "Alternative Nows and Thens to Be: Art History and the Future of Art." Presentation at PB 43, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013.

- Shindler, Kelly. "Life After Death: An Interview with Eva and Franco Mattes." Art21 Magazine, May 28, 2010. http://blog.art21.org/2010/05/28/life-after-death-an-interview-with-eva-and-franco-mattes/.

- Siebers, Tobin. Disability Aesthetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010.

- ———. Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008.

- Solomon, Olga. "Sense and the Senses: Anthropology and the Study of Autism." Annual Review of Anthropology 39, no. 1 (2010): 241-59.

- Stendal, Karen, and Susan Balandin. "Virtual Worlds for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Case Study in Second Life." Disability & Rehabilitation 37, no. 17 (August 2015): 1591-98.

- Taylor, Astra. Examined Life: Excursions with Contemporary Thinkers. Zeitgeist Films, 2008.

- Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books, 2011.

- Turner, Fred. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

- Wilson, Robert A. "The Role of Oral History in Surviving a Eugenic Past." In Beyond Testimony and Trauma: Oral History in the Aftermath of Mass Violence, edited by Steven High, 2014.

- Youngman, Hennessy. ART THOUGHTZ: Relational Aesthetics, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yea4qSJMx4&feature=youtube_gdata_player.

Illustrations

Figure 1: Eva and Franco Mattes, Reenactments: Tapp und Tastkino, 2010. Video still of documentation of performance in Second Life. Available from http://0100101110101101.org/reenactment-of-valie-export-and-peter-weibels-tapp-und-tastkino/

Figure 2: Eva and Franco Mattes, Reenactments: Impoderabilia, 2007. Video still of documentation of performance in Second Life. Available from http://0100101110101101.org/reenactment-of-marina-abramovic-and-ulays-imponderabilia/.

Figure 3: Eva and Franco Mattes, Synthetic Performances: Medication Valse, 2009-2010. Video still of documentation of performance in Second Life. Available from http://0100101110101101.org/medication-valse/

Figure 4: Detail of I-frame compression artifacts in Medication Valse.

Figure 5: Eva and Franco Mattes, Synthetic Performances: I can't find myself either, 2010. Video still of documentation of performance in Second Life. Available from http://0100101110101101.org/i-cant-find-myself-either/.

Figure 6: Eva and Franco Mattes, Synthetic Performances: I know it's all a state of mind, 2010. Video still of documentation of performance in Second Life. Available from http://0100101110101101.org/i-know-that-its-all-a-state-of-mind/.

Figure 7: Detail of avatar overlap in I know it's all a state of mind.

Figure 8: Detail of avatar overlap in I know it's all a state of mind.

Endnotes

-

Anne Balsamo, Technologies of the Gendered Body: Reading Cyborg Women (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 132.

Return to Text -

Jaron Lanier and Adam Heilbrun, "A Portrait of the Young Visionary," Whole Earth Review, 1988, http://www.jaronlanier.com/vrint.html.

Return to Text -

Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 1999); Lisa Nakamura, Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet (New York: Routledge, 2002); Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006).

Return to Text -

Balsamo, Technologies of the Gendered Body, 127; Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 208.

Return to Text -

Balsamo, Technologies of the Gendered Body, 10.

Return to Text -

John Durham Peters, Speaking Into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 5.

Return to Text -

Though, as Peters deftly points out earlier in the book, this problem emerges long before the Victorians, as early as Socrates. Ibid., 39.

Return to Text -

Elisabeth L. Hill and Uta Frith, "Understanding Autism: Insights from Mind and Brain," Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 358, no. 1430 (February 28, 2003): 281.

Return to Text -

The DSM V presently conflates autism, autism spectrum disorder, Asperger's, and pervasive development disorder not-otherwise-specified which in previous versions of the manual had served to lend nuance to the wide-reaching criteria for autism. American Psychiatric Association, "Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes: Neurodevelopmental Disorders," in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

Return to Text -

Hill and Frith, "Understanding Autism," 281.

Return to Text -

Olga Solomon, "Sense and the Senses: Anthropology and the Study of Autism," Annual Review of Anthropology 39, no. 1 (2010): 428, doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.105012. Following the general preferences of the autistic community, this study does not use person-first language (i.e. "people with autism"). See Nancy Bagatell, "From Cure to Community: Transforming Notions of Autism," Ethos 38, no. 1 (March 1, 2010): 40.

Return to Text -

Jørn Isaksen et al., "Autism Spectrum Disorders - Are They Really Epidemic?," European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 17, no. 4 (July 2013): 330, doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.03.003.

Return to Text -

Eyal Gil, "For a Sociology of Expertise: The Social Origins of the Autism Epidemic," American Journal of Sociology 118, no. 4 (2013): 864-865.

Return to Text -

Patrick McDonagh, "Autism and the Modern Identity: Autism Anxiety in Popular Film," Disability Studies Quarterly, 19 (1999): 190.

Return to Text -

Balsamo, Technologies of the Gendered Body, 124.

Return to Text -