Accessing museums has been difficult for people who are blind or partially sighted, often due to objects being placed in glass cases creating a barrier to access. Many museums around the world provide some accessibility but what happens when a museum looks at the issue in its entirety and sees blind and partially sighted visitors as important as everyone else.

The Victoria & Albert Museum in London has tried to take an holistic approach to access, by looking at what prevents blind and partially sighted visitors visit a museum and how it can improve access for such an audience.

Taking a focused approach to consider not only the objects but implementing a museum wide strategy is required to provide inclusive access for all visitors. The museum considers how it can improve the visitor experience by removing the physical barriers, staff training, providing touch objects and tactile books, as well as looking to the future to see how technology can play a part in improving access.

Employing people with a disability has also assisted the V&A in its journey to becoming more accessible by employing a blind person as its first Disability and Access Officer, a unique opportunity to change from within.

Introduction

The Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of art and design. First opened in 1857, the museum is housed in seven Grade 1 Listed buildings, which combine to form one large building and seven miles of gallery space. A listed building, in the United Kingdom, is a building that has been placed on the Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest, similar to the National Register of Historic Places in the United States. However, this gives us the opportunity to show how an historic building which was not designed with disabled people in mind can be made into an accessible environment for all users in the twenty first century.

The V&A is part of a family of museums consisting of The V&A in South Kensington and the V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green. It also operates an accessible archive and store at Blythe House in West London (jointly run with the British Museum and the Science Museum).

The purpose of the Museum is to enable everyone to enjoy its world class collections and to explore the cultures that created them: to inspire those who shape contemporary design.

Over the past ten years, the museum has been pro-active in developing inclusive and accessible services and premises for its visitors, including those with sight problems. The V&A's aim is for disabled people to come in off the street, just as any visitor would, to enjoy the collection. Historically this approach has not been the norm for museums as many would not be either physically or intellectually accessible. This is why in the V&A's FuturePlan, a redevelopment of the South Kensington and Museum of Childhood sites, access for disabled people is a priority.

FuturePlan

FuturePlan is an ambitious programme dedicated to restoring and enhancing the V&A's original 19th century architecture, opening up previously hidden areas to the public and improving visitor facilities. Over the past ten years 70% of the Museum's public space has been transformed through FuturePlan phase 1. Following the completion of the British Galleries in 2001 more than forty FuturePlan projects have been completed, transforming accessibility throughout the museum.

The picture below shows the V&A entrance completed in 2001, where a ramp now gives access to wheelchair users to the main entrance. This is great for wheelchair users, who can now gain access to the entrance, but what happens when you get inside? And what about other visitors with disabilities? What facilities are there for visually impaired visitors in particular? This article will show how the V&A has taken a long term approach on accessibility through FuturePlan and considered visually impaired people when implementing services and policies.

Cromwell Road Entrance, V&A museum

Organisational Strategy

Organisations need to consider that accessibility is not only physical adaptations to buildings, it is about the management and services which also aid access. By creating a strategy that pulls together all elements of disability into one document focusing on the moral, legal and business case and how that can impact on day-to-day activities for both staff and visitors.

The V&A began this process in 2002 when it employed me as the museum's first Disability and Access Officer. I was also the first blind employee of the V&A. This was a new area of work, as my previous work experience was providing a consultancy service to the RNIB (Royal National Institute for Blind People) and several property service companies.

As a Consultant for RNIB, I worked to develop improved access to sporting and leisure venues, undertaking access audits and training staff and sports commentators, so working in a museum was a step into the unknown. However, service provision in a museum is the same as it is for sporting venues or other customer facing organisations regardless of the visitors needs e.g. asking a visitor/customer if you can assist works for a museum as well as a retailer. For example, in 1998, I was refused into a cinema as I was told my Guide Dog was "a fire hazard". The Operations Manager thought he knew what was best for me without asking, surprising as we had never met before. If the Operations Manager had asked how I could be assisted, it would have saved his organisation thousands of pounds in legal fees and compensation as this was the first successful Guide Dog case under the Disability Discrimination Act in the UK, which has set a precedent for all service providers.

I carried out an access audit of the museum to understand the levels of provision for disabled visitors including visually impaired people. The audit looked at the levels of service provision for visitors, and how FuturePlan can achieve accessibility.

The Disability Action Plan published in 2004 highlighted the positives and set out a three-year plan of action for those areas that required attention.

The Disability Action Plan was partly driven by the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) which came into law in 1995, which places a duty on service providers to make 'Reasonable Adjustments', remove any physical barriers to accessing the building and also remove attitudinal barriers to allow disabled people to access services. The DDA was based upon the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), however it did not provide the legal rights which came with the ADA. The DDA has now been incorporated into the Equality Act which came into law in 2010.

The Audience

Why is it necessary to provide access to museum collections for visually impaired people? At the V&A, which is partly government-funded, visually impaired visitors are as entitled to gain access to the collection as any other tax payer. As stated above, the DDA places a legal duty on the museum to make 'Reasonable Adjustments' to services and collections. If you have always enjoyed art and design, why should you stop once your sight fails?

It is estimated by the Royal National Institute for Blind People (RNIB) that there are about two million people in the UK who are registered blind or partially sighted (Visually Impaired). This means, that for every thirty people within the UK, one will have a sight impairment which substantially affects their day-to-day activities. As the majority of Visually Impaired people are 50 years or older, it is important that adjustments which are made today will also benefit people for the future.

Gallery Interpretation

Visually Impaired visitors are faced with particular issues when visiting the V&A because so much of what is presented in the galleries is visual. The first FuturePlan project to be completed, giving improved access for visually impaired people, was the British Gallery where an Access Consultant was employed and had input into both the interpretation and physical access of the gallery.

The Gallery Interpretation policy developed out of FuturePlan, considers interpretation to be "the bridge between the Museum's objects and expertise and our visitors' curiosity and knowledge". The policy goes beyond labels and panels to include new media that invite touch, action, analysis and reflection. This is a move away from the traditional where museums have hidden objects in glass cases, inaccessible to many people — especially those who cannot see.

The objective of the Gallery Interpretation Policy is that accessible interpretation elements will create a minimum standard for interpretative provision. Three key questions were asked during consultation with Visually Impaired visitors:

- Is the provision clearly marked and easy to use?

- Does the provision significantly aid understanding of subject matter?

- Does the provision encourage further exploration of the V&A from the user?

Touch Objects and Braille

One of the major changes in FuturePlan was to incorporate touch objects into galleries. The Interpretation Strategy has made touch objects the norm in the V&A, allowing all visitors to interact with the objects. Museums used to invite visually impaired visitors in to touch objects after the museum had closed. Doing this when the museum was open would have encouraged able-bodied visitors to touch these objects too. Now, permanently-displayed objects can be investigated and appreciated by all visitors, not just those with a visual impairment.

There has been much debate in the museum sector as to whether original or replica objects should be used as touch objects. The V&A uses both originals and replicas in galleries as it is not always possible to show an original object due to security reasons or its requiring a high level of conservation. Below, is a photo of a Ming vase, in the T. T. Tsui Gallery, which is permanently on display. It is an original made in 1550. The vase is a touch object, giving all visitors, including Visually Impaired people, an opportunity to interpret such a precious object. Located next to the vase is Braille information giving further accessibility. However, due to the height and positioning of the Braille, the object and the accompanying Braille aren't as user friendly as they should be.

Ming Vase, T.T. Tsui Gallery

By assessing the accessibility in the British Gallery and other gallery projects, the museum learnt much about how touch objects and Braille information should be designed into a display. Initial consultation on touch objects and how they might be displayed was undertaken with visitors with varying success. The museum ran Focus Groups to assess the requirements of visually impaired visitors, researching the preferred height of the objects, the use of Braille and also the type of objects which would be of interest. Some objects were chosen purely because they looked tactile. For instance, blocks of different woods were offered as touch objects so visitors could feel different grains. However, to help conserve the wood, the museum treated it, so preventing the visitor from interpreting the object. This set of touch objects had very little learning before treatment and became completely irrelevant afterwards.

Further learning from the gallery development was the use of interpretive provision aimed at making information more accessible. In the British Gallery, tactile line drawings were installed so visually impaired visitors could understand images such as The Crystal Palace (a building which housed the Great Exhibition in 1851). Raised lines outlined the edge of the structure and significant detail within, with further raised lines leading from the outer part of the panel to letters of the alphabet, indicating important areas of the building. The lines leading from the alphabet directed the user to Braille information. However, the amount of raised lines put into the images made it impossible to follow, thus rendering the activity pointless.

The importance of selecting any object is that it fits in with the story of the gallery and conveys what the Curator wishes it to say. An object should not be chosen because it looks good to touch; it must have qualities which help the visitor to understand the object in relation to the collection and the technique by which it is made. For example, the Ming vase shown above was selected due to it being from a significant period in Chinese history and not just a beautiful object to be touched.

Suitably designing a touch object in a gallery is more than just putting it on a ledge and fixing a Braille panel next to it. For each object for instance, consideration needs to be taken on how high or low it will be positioned since children and adults will all want to touch.

Putting a Braille panel next to an object seems an easy task, however at times you could think you are designing a new rocket system for NASA. Following research undertaken with Visually Impaired visitors, it was found that Braille panels next to objects should be laid flat as this allows visitors of all heights to read comfortably. Occasionally, panels have also been designed to pull out from under the object where space has been a factor.

By assessing the visitor's interaction with objects and Braille, the following dimensions were found to be usable for a wide range of visitors:

Object height — 30" from the floor. The base of many objects should be at the specified height to prevent tall people from having to bend forward. However, if you display large objects e.g. motor vehicles, consideration must be taken regarding which part of the vehicle is significant enough to be touched.

Braille information — 30", flat to a table top or as a pull out panel. It is important that the panels are located next to the object and are not located in any circulation routes which may prevent the label being used.

The inconsistent approach to Braille in V&A galleries could often be difficult for users to find and both Grade 1 and Grade 2 Braille were used. Grade 1 Braille provides information in alphabetical form, being the first level learnt when using Braille. Grade 2, our preferred choice contracts words e.g. the word "The" becomes one symbol and not the three alphabetical characters.

Guidance on how to produce the panels and the specification of Grade 2 Braille, and more importantly the management of the process were outlined. Another failure of the British Gallery was that Braille panels were installed at the wrong object and the manufacturer did not label the panels in print. Also the museum did not have a Braille reader on site during installation. Therefore, written guidance on how this process should be achieved was produced.

The following requirements cover production of Braille and management of the installation process:

- All Braille text should be produced in Grade Two Braille. The Braille should conform to British Braille guidelines and only use Braille symbols such as: punctuation, number signs or letter signs.

- As a general principle the Braille panel should contain the same text as the print label. Occasionally there may be a need for slightly different information in the Braille panel but this should be the exception.

- Braille panels should be located either: flat on a surface with the touch object or as a pull out panel. The Braille panels should never be located flat on walls as this is difficult to read by Braille readers as a person's height may prevent them from comfortably reading the text.

- The specified height from floor level of the panel should be no less than 30". This allows children and wheelchair users who are Braille readers to have access to the information.

- All Braille panels must be checked by a Braille reader before any manufacturing takes place. On receipt of the Braille panels, proof reading by a Braille reader must be carried out before installation.

- The Braille reader should also be available during installation and on hand to check that the panels are being installed at the correct object.

Audios and Audio Description

The V&A is moving away from the use of Braille for touch objects in galleries as there is a limited audience who read Braille. With the limitations on funding and the will to provide access to a wider audience the museum wishes to provide greater accessibility through new technology. Audio descriptions of objects are being written and recorded to assist visually impaired visitors to listen to descriptions downloaded via their own smart phones.

Over the past several years, the V&A has been assessing the accessibility of multimedia guides in many organisations which provide information to all visitors in their chosen format. The aim would be for the museum to provide a system which is both user friendly to all visitors and accessible to those who are not as technically minded or have been excluded by new technology.

I visited three museums whilst in Boston in the United States in 2011 and assessed two multi medias, one at the Hall of Patriots Place an American Football Museum who use an Infrared system and the Museum of Fine Art in Boston who use I Pods.

Both systems had benefits and drawbacks, meaning that not one system would satisfy all user needs including those who are Visually Impaired. Benefits such as language selection and audio features made the systems more accessible, where usability in selecting menus and options on touch screens may be a barrier to independent usage. Therefore, in the short term the V&A will provide audio descriptions in an MP3 format which is downloadable from the museum's web site.

In 2006, the first audio descriptions accompanied videos in the Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art. These descriptions have proved beneficial for all as the Describer highlights significant images within the video which even many sighted visitors had not noticed such as certain colours or inscriptions. Further audio descriptions have been developed for the Furniture Gallery which opened in December 2012 and the Europe Gallery which opens in 2014. The new audio descriptions will be available both in the galleries and via the museum's web site.

A self-guided audio trail had also been planned to take Visually Impaired visitors around the museum, locating ten touch objects. Due to the complexity of the building and the large walking distances, only the audio description of the objects has been produced, and not the directional information as first planned.

Complex buildings such as the V&A with eighteen split levels make it impossible for visitors to follow directions, especially those with a visual impairment. Audio guides in some museums give directions from object to object by using stride length and then visual clues. As people's strides differ and not all visually impaired people are prepared to stride out in unfamiliar places, this directive becomes non-effective. Only when internal guidance systems similar to external GPS are available will visually impaired people be able to self guide around large museums like the V&A.

All of the ten audios can be downloaded from the museum's website in an MP3 format, making it accessible to all smart phones and MP3 compatible phones. However, visitors who do not use smart phones are not forgotten as the museum will provide the audios on a device which can be picked up on arrival at the museum.

Tactile Books

Being able to access photographs and paintings can be difficult for Visually Impaired people. Audio Description as outlined above can assist, however using a tactile image can add to the description given enabling the visitor to further interpret the work. The V&A has developed its provision since first making line drawings available to visitors in the late 1990s, interpreting images for the Photography Gallery.

Books developed for the Paintings Gallery took on both the tactile image form and techniques we use today. However, not all Visually Impaired people have been taught to touch which can make reading tactile images difficult, so on occasion it is necessary to remove less important elements enabling the user to focus on key images of the work.

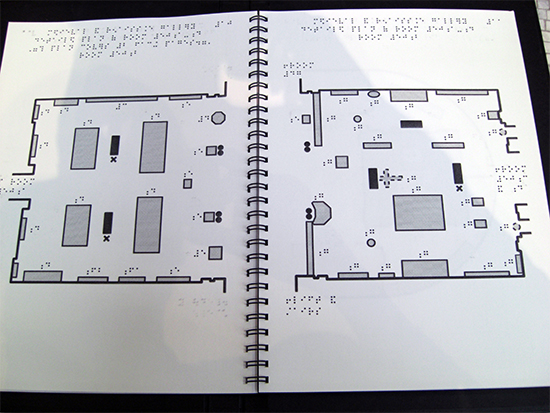

To try and develop this form of interpretation further, the V&A has worked with the Royal National Institute for Blind People to make tactile images more accessible. The tactile books have: Braille information of gallery panels; gallery plans so the visitor can orientate themselves in the gallery; and descriptions of the tactile images as well as the tactile image itself. Where necessary, the images have been simplified to highlight the key elements of a picture.

Tactile book with Braille description

To help the V&A and RNIB further get it right, a focus group was run to develop resources for the Medieval and Renaissance Gallery, the final FuturePlan project. The group, all Braille readers, evaluated the tactile images and their accompanying descriptions with the following outcome for producing tactile image books:

- The images must be interesting and informative.

- Textures and lines must be distinguishable.

- Braille labels on the images in full where at all possible.

- Have a key on the image page when abbreviations have to be used due to space limitations.

- Keep titles simple.

- Do not mention things that are not shown unless relevant to the image.

It is not enough to just have the tactile images - having only half of the information does not give equal access. Description of the images was written to help the visitor navigate around the image. From the Focus Group, the following directions helped when looking to provide images and text:

- The descriptions must explain the image so the visitor understands. Reading and understanding the descriptions takes quite a lot of time so the descriptions need to be written as concisely as possible.

- Ensure that the important details are given first e.g. having to turn the page sideways to read the image.

- Important to have the details about size date etc. at the beginning in order to start the process of understanding.

- Use vocabulary which is suitable for a wide audience.

- Do not assumed knowledge, on occasions further explanation may be required.

Accessible Talks and Events

The Learning Department has developed further interpretive provision by programming talks for disabled people; the V&A is one of the first museums in the world to have done so. The aim of the programme is to encourage disabled visitors to the museum by offering events which cater for their specific needs. The programme focuses on both the permanent collection of the museum as well as special exhibitions.

The V&A first started providing talks and touch tours for Visually Impaired people in 1985 after receiving requests from societies for the blind. The programme soon developed into the programme we have today, where one touch tour or handling session takes place per month or on request. Monthly talks for visually impaired people take place in galleries, led by Curators and V&A Guides complementing the touch objects permanently displayed. Whenever a new gallery opens a programme of events is planned to show visitors the newly displayed objects.

V&A Touch Tour

It is not always possible for visitors to touch objects in an exhibition due to loan agreements with the owners. Therefore, Curators will give a talk and handling session in a seminar room which focus on objects from the exhibition. Although this is not the inclusive experience we would like to offer, touching objects before entering the exhibition allows the visitor a better understanding of the display when described to them.

Planning a touch tour is just like planning any other talk:

- You select your subject and the date of the talk.

- Book a speaker, Curator or V&A Guide.

- Work with the Curator/speaker to select suitable objects which can be touched.

- Arrange for volunteer guides to assist the visitors during the talk.

When leading a touch tour or handling session, the V&A directs the Curator/speaker to consider the following:

- When in a public gallery and walking is involved, then around seven or eight objects to talk about will be sufficient. If it is held in a room as a handling session, eight to ten objects can be used.

- Where possible, allow the visitor to touch objects with their bare hands. Be guided by the Curator who will specify if gloves are to be worn.

- The visitor will need time to examine the objects and there will be long pauses and the need for individual explanations. Always take the pace from the visitor, even if the visitor examines the object before you start your description.

- Focus your description on what is being touched at any time, and offer to guide the hand, when appropriate.

- When objects cannot be touched, it may be useful to use materials or objects which relate to the work being described. Any additional objects or materials, which are to aid a touch tour, should be relevant and not take the visitors mind away from the original piece.

- Only end the session when the visitor is satisfied that they have gained the information they wish to take from each piece.

Behind The Scene Talks

Much work goes on behind the scenes in the museum, from conserving objects to dressing galleries. So visitors can learn about the work undertaken by staff who do not have a customer facing role, behind the scene tours are organised. The talks allow Visually Impaired visitors to touch objects which are in the process of being conserved before going into galleries or exhibitions. For example, visitors to the Stained Glass conservation department watched the making of a stained glass replica that is now permanently displayed in a gallery. Also curators from the Fashion department have demonstrated to visitors how they dressed mannequins for the Ballgowns: British Glamour since 1950 exhibition.

Audio Described Events

Audio Description is often used for television programmes, films and theatre, however the same techniques can be used in describing museum objects or live performances. For example, audio description has enhanced performances in Fashion in Motion, the catwalk fashion show at the V&A starting in November 2004, and also the Chinese New Year celebration.

As both events are live, the Audio Describer is positioned away from the performance but within visual range. Having watched the rehearsals, the describer gets an understanding of the running order allowing them to have prepared information of the performance to hand. The narrator describes information a visually impaired person might not be able to see so they can interpret the subject in a more accessible way. The visitors receive the commentary via radio receivers enabling them to sit anywhere within the auditorium.

The audio described events complement the described talks (verbal description) that happen when objects cannot be touched. To aid speakers to deliver more descriptive talks, including a touch tour to visually impaired people, the museum has developed guidance:

- Each session should last an hour and a half to two hours maximum.

- Take your time - Speak clearly and do not try to overload too much information into a session. Pay close attention to the speed at which you speak, and pace yourself.

- Ask questions to the visitor - this will allow the description to flow and meet the needs of the visitor.

- Do not be afraid to use words such as: sight or see. Use everyday words and terms when describing an object.

- Many blind people who have lost their sight have a visual memory of colours, which will help to build up a picture of the object in their mind.

- The use of size can be beneficial because everyone can relate to it. Using examples of size, from everyday experiences and objects will enable a visually impaired visitor, to relate to the object. Size in terms of the human body may be particularly useful, e.g. a London bus is five times the height of a person.

- Use the basic information found on a label, such as the name, title or subject of the object etc as a starting point before the description.

- A general overview of the object, which describes the object as a whole, can include subject matter if appropriate. Include the style of a work of art, or the context of an object. In a tour which includes descriptions of several objects, make comparisons between objects, styles and methods of production.

- To provide a starting point to the description of where objects are placed within the work, you might use the position of the numbers on a clock. For example, you may begin at the top of a painting, which would be 12 o'clock, and work down to the bottom of the picture, until you arrive at 6 o'clock.

- Do not skip around the object as this may confuse the visitor. Move in a logical, sequential order. Give accurate, precise instructions for moving from one place to the next. If you are working with a sculpture, work in a sequential movement, e.g. start from the head and move down to the feet.

- Once you have set the scene with a general description, fill in the gaps with specific details. Take time to show the relationship between details and the entire object.

- Take the lead from the visitor in when to finish a description. Dependant upon the interest or experience of the visitor will determine the length of time spent at an object.

Practical Art Workshops

The V&A offers more than just touch tours and audio descriptions with a planned series of workshop activities as part of the public programme. Providing practical activities allows visitors to express their own interpretation of the museum's collection. The V&A has been proactive in providing events which are accessible to visually impaired visitors for many years.

In 1998, photographer Eric Richmond tutored a group of nine visually impaired people. They produced black and white pictures of the Sculpture Court which were displayed outside the V&A's Canon Gallery of Photography. Participants reported that the course helped them to learn about photography and gave them greater access to the collections. Photography has been a favourite amongst visually impaired visitors with the museum running more than ten workshops since 1998.

Drawing and painting workshops for visually impaired visitors have also been popular. Terry and Lilly, who have never seen, were interested in Constable's work. Using his sketches of the sky and light reflections on landscape, a series of raised drawings were produced and the pictures were described. They also found it of help to paint the sky themselves so that they formed a better understanding of how it continually moves and how Constable portrayed this. The Constable pictures and the raised drawings were displayed in the Constable Room at the museum.

Touch Me, a V&A exhibition held in 2005, explored the sense of touch both physically and emotionally. Visually impaired people participated in a workshop run by Carmel McElroy, designer of the Feeling Rug Knitted Fingers. Participants created their own rugs inspired by Carmel's exhibited rug, giving their own interpretation on her work.

The most recent workshop focusing on the Constable and Turner paintings Seeing is Art, run by Sally Booth an artist who is herself visually impaired, taught visitors the techniques in which Constable and Turner created their work. Sally is now working with the museum to run regular workshop sessions focusing on other V&A collections including ceramics and photography.

Staff Training

To help achieve the work outlined above, the museum needs to have staff who wish to provide equality in service. The Disability Action Plan not only looked at the services, facilities and premises but challenged people's attitudes: if you can't get past the person on the door, it is pointless having an accessible environment.

The V&A has implemented training for staff to breakdown attitudinal barriers which prevent visually impaired people accessing the museum. Front of House and Learning Department staff received disability awareness training and visual awareness training, which I run.

Having a basic knowledge of the needs of the visitor and being able to ask the right questions "how can I help you?" aids a better customer service and more importantly takes the assumption of knowing how best to help the visitor without the knowledge base.

The Visual Awareness training is more than showing how to guide visually impaired people; a context of why we are doing such training is needed. Giving staff the background of visual impairment, facts and figures and dispelling some of the myths is important not only for their work at the museum but for life outside.

Safely guiding a visually impaired person around the museum is key to aiding an accessible visit. Therefore, some of the training is undertaken using blindfolds. This is not to show the person undertaking the task what it is like to be blind, it is to highlight how difficult it can be when Visually Impaired people visit an environment such as a busy museum. Being able to see the size of a room differs greatly to interpreting the space without sight and this task aims to highlight such factors.

Personal Experience

What is it like for someone who is visually impaired to work in the arts? Being blind and working on disability issues did not mean that I was the right person for the job. When I came into post, I was still studying the MSc Inclusive Environments Design and Management at the University of Reading. I had been working on disability issues since going blind in 1994 and the MSc was a way of formalising my experience with a qualification.

Like most people starting a new job, I wanted to make my mark, but in an organisation as complex as the V&A where do you start. Having little museum experience, combined with no interest in art, this role was going to be a challenge. I now have an interest in art, making it accessible to those who would like to access it and those who wish to work in the museum.

I have often been asked, "why are you working in an art museum if you don't like art?" The reply is "the job I undertook was what made me apply". The role encompasses every aspect of the V&A's work, from the strategic planning to designing new galleries, developing policies and practices, staff training and managing the talks and events programme for disabled visitors, how often you get an opportunity to do so much variation in a job.

A lot of good work was happening at the museum on disability issues when I first came into post; however it was all isolated with no coherent approach, or often not known by others around the museum. To help the museum to take a coherent approach, I wrote the first Disability Action Plan as outlined above. Putting together my experience as an Access Consultant and studies at the University of Reading where I gained an auditing qualification, I audited the museum to find the levels of service or not as the case maybe.

I am not a person who likes to write lots of policies and then let them gather dust on a shelf; however, it is essential to write strategies and guidance which will lead to an outcome. The action plan was referenced to the Disability Discrimination Act, codes of practice produced by the Disability Rights Commission, Museums Libraries and Archive Council's Disability Portfolios and my own experiences and ideas as an access auditor.

The Codes of Practice aimed to assist employers, service providers, premises owners and education providers on how to meet the Disability Discrimination Act, however they were long and often confusing as what would work for one disability wouldn't work for another. With my interpretation of the Codes of Practice, the plan pulled together the positives and set out a plan of action for a three year period. The action plan was seen as best practice by the employers Forum on Disability in the 2006 Disability Standard, the first benchmarking survey on disability in the world. As this was the first Disability Action Plan I had personally written, it was pleasing to have gained such recognition but more importantly it was being implemented throughout the museum.

Any action plan isn't worth the paper it is written on unless a budget is allocated to undertake the projects. After a short negotiation with the Finance Director who had some knowledge of access work, I walked out of his office with the best part of £100,000 ($160,000) increase in budget for year 1 projects. This budget gave me the opportunity to implement many projects, including:

- The instillation of a Fire Pager System which alerts deaf people to the fire alarm;

- Assistive technology on computers in the National Art Library and Prints and Drawings study room;

- The design and printing of the V&A's first Access Guide.

One of the greatest challenges at the museum was getting people on-side as often people didn't relate to disability or disability issues. Several colleagues felt that accessibility is just a whim, and as we haven't had any disabled people come to the museum in the past, why should we make the building accessible. On one project, colleagues felt that if I spent the money on my proposal it would be "criminal" and "I was beating the museum with a stick". Fortunately these people have now left the museum, with more open minded people in these significant positions.

Being at the right place at the right time is important when developing policies and practices which have long term implications. One of the practical changes made by the V&A's Project team on FuturePlan was to include me into the design process. It is too late when your half way through a project to make changes as it becomes difficult to alter designs and becomes more costly. Since we have taken this approach, I feel access is more integrated and "we often get it right, more than we get it wrong".

The V&A journey to accessibility has been long and difficult and sometimes sole destroying. The challenges which have been met and often overcome have led to improved accessibility for all visitors. I have found that access can be achieved even in organisations with complex structures; perseverance and a thick skin are key elements in the armoury of an Access Officer.

After ten years of work in the V&A, I feel I have learnt a grate deal, stretching myself on a daily basis. I hope I have shown colleagues that blind people can work and achieve their goals and access is for everyone to address and not just key individuals.