Can online media help disabled people become more engaged in the organizations that represent their interests in the public arena? Using a combination of Web content analysis and qualitative interviews, this article investigates whether online communications are challenging traditional patterns of power distribution in Scottish disability organizations. Overall, empirical findings only partially matched expectations that member-led groups would be more inclined than 'professionalized' charities to embrace interactive online media. Although most groups acknowledged the Internet's potential to empower disabled users, none of them deliberately pursued that outcome through their respective Web outlets. Instead, conservative views on the Internet prevailed across the entire organizational spectrum. Nonetheless, the analysis revealed also that such 'minimalistic' approach to online media was in fact underpinned by very different motives for disability non-profits on one side and self-advocacy groups on the other.

A little over three decades ago, disability studies pioneer Vic Finklestein (1980) argued that technological development, and especially new Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), would eventually mitigate the impact of exclusionary barriers and foster the emancipation and empowerment of disabled people. Although such optimism resonated with the work of political scientists like Barber (1984), who claimed that ICTs were poised to herald an era of radical democratic renewal, an empirical debate on the effects of online communications on disabled people's involvement in the public arena is yet to be had. So far, the vast majority of research on disability and online media has focused instead on issues of access and accessibility (e.g. Ellis & Kent, 2011). Indeed, these concerns remain relevant to date as only 41% of disabled Britons regularly used the Internet in 2011 compared to 78% of the general population (Dutton & Blank, 2011: 18). These data resonate with the constructivist argument for which technology, as a social product, is bound to reproduce pre-existing mechanisms of exclusion including disabling barriers (Roulstone, 1998; Goggin & Newell, 2003), thus exacerbating established inequalities (Dobransky & Hargittai 2006). In addition, these findings have corroborated also the idea of digital divide (Norris, 2001; Warschaurer, 2003; Vicente & Lopez, 2010), which continues to be immensely popular among Internet scholars as well as policy-makers.

Yet, as Pilling, Barrett, and Floyd (2004) noted in their seminal investigation of the experiences of disabled users in the UK, the relationship between disability and online media is a complex and multi-dimensional one that cannot be summarized by a single figure. As such, work on disabled Internet 'pioneers' has consistently highlighted their positive attitude towards online technology (Goggin & Newell, 2004; Sheldon, 2004), stressed the importance of discussion forums and blogs as platforms for the diffusion of alternative and un-mediated representations of disability (Thoreau, 2006; Goggin & Noonan, 2007), pointed at the role of online communications as a booster and multiplier of interpersonal relationships (Anderberg & Jönsson, 2005), and discussed the benefits of mobile devices for disabled users (Goggin, 2011). Moreover, Internet use among disabled Britons is heavily weighted towards younger generations (Williams et al., 2008), who at the same time are also more likely than their older counterparts to be civically and politically engaged (Schur, Shields & Schriner, 2005). For these reasons, it is essential to ask whether the popularity of accessibility research has in fact dimmed other, more nuanced aspects of the relationship between disability and online media, including the use of interactive platforms such as blogs, forums, and social networking sites. This is not to underplay the importance of access and accessibility issues, but rather to establish whether, while some barriers are mirrored in the online environment, others could in fact be re-negotiated. In line with Watson's call for a broader "critical realist" shift in disability studies (2012), it is therefore important to re-align investigations of disability and the Internet with the lived experiences of disabled people, especially those who regularly engage in online communications in spite of persisting accessibility problems.

In light of these observations, this paper investigates the Web presence of nine emblematic Scottish disability non-profit organizations and self-advocacy groups with a view to establishing whether online media can challenge the traditional power differential between organizational 'elites' and grassroots supporters. Following a brief overview of the role of non-profit organizations in contemporary Scottish governance, this paper asks whether disability groups have taken advantage of participatory online media to help their primary constituents acquire an un-mediated 'voice' in the public arena. Results indicating that both 'professionalized' non-profits and as grassroots collectives unexpectedly shared a rather conservative approach to online communications are then discussed. In particular, interviews with those responsible for maintaining the Web presence of the groups under scrutiny are analyzed in order to expose the mechanisms that lay behind this pattern. As such, crucial differences among the perspectives on technology held by different types of organizations are identified.

Disability organizations as e-democratic actors?

In recent decades, successive UK governments sought to reverse a negative trend in civic and political engagement by bringing decision-making 'closer' to citizens. In this framework, voluntary organizations, self-advocacy groups, and other civil society collectives have often been encouraged to act as intermediaries between citizens and political institutions (Barnes, Newman, & Sullivan, 2007). While many remain doubtful with regard to the 'democratizing' impact of this approach (e.g. Craig & Taylor, 2002), this process has placed additional accountability and representativeness requirements upon non-profits and advocacy groups. Thus, it has been argued that the latter should engage more directly with their members, supporters, and other stakeholders on an ongoing basis (Mourdant, 2006). In particular, this is crucial for organizations that strive to represent social groups that are traditionally marginalized or altogether excluded from the democratic arena and civic life more generally (Foot, 2009). This is especially relevant for disability advocacy groups given the barriers that routinely exclude their primary constituents from the public arena (Campbell & Oliver, 1996; Drake, 2002; Morris 2005).

These issues take on even greater relevance in Scotland, where non-profits have enjoyed a particularly close relationship with policy-making institutions ever since the devolution of legislative powers from Westminster to Edinburgh was implemented in 1999. In particular, several policy domains likely to have a direct impact on the livelihoods of disabled Scots — healthcare, social work, transport, education, and housing just to name a few — have since been the exclusive prerogative of the re-constituted Scottish Parliament. This has created a smaller political arena that provides local disability organizations with unprecedented opportunities to approach decision-makers directly (Maxwell, 2007: 221). In addition, Scottish political parties have been particularly keen on involving non-profit organizations and advocacy groups in policy-making as a way of promoting 'consensus-based' governance (Keating, 2010: 92-3).

In this context, research has shown that a variety of pre-existing civil society groups have been able to harness the potential of the Internet to communicate more frequently with their constituents, thus enhancing their representativeness and boosting their credibility in the eyes of policy-makers. In particular, e-advocacy practices have led some established non-profits to assimilate participatory elements typical of social movement groups, arguably shifting power to grassroots supporters and generating 'hybrid' organizations (Chadwick, 2007). However, it would be incorrect to say that new media pushed established non-profits down a participatory route per se. Rather, the inclination of a given group to provide its supporters with options for meaningful e-participation has been strongly linked to its pre-existing structure, underpinning ideology, and overall mission (Kenix, 2007, 2008; Burt & Taylor, 2008). In other words, the extent to which online engagement and e-campaigning have 'democratized' these groups has been highly variable and dependant on their predisposition to experiment with participatory practices, as well as their willingness to take on some of the risks involved. In light of these considerations, it was important to ask whether Scottish disability organizations too have used the Internet to re-design their relationship with constituents, empowering them, and addressing some of the democratic requirements deriving from their increasingly prominent role in policy-making. In order to formulate useful hypotheses, it was essential to reflect on the structure, values, and purpose of these groups, as well as considering the impact that these factors may have on their approach to participatory online platforms.

The problem with charity: Groups 'for' and 'of' disabled people

The structure of disability organizations in Britain highlights a number of tensions that, in turn, question the existence of a solid collective identity for the disability 'community.' Shakespeare (2006) provided a useful 'working' categorization of disability organizations, identifying three main group typologies, including:

- traditional charities led by voluntary sector professionals and centered on service-provision;

- member-led groups strongly influenced by the social model of disability and chiefly orientated towards policy and advocacy work; and, finally,

- hybrid bodies that were established decades ago as traditional charities and have since undergone substantial changes to introduce, at least on paper, some degree of user-control.

Historically, traditional charities have been heavily criticized by prominent social model scholars and disability rights activists. In particular, the approach of these organizations to support services has long been regarded as promoting the perpetuation of disempowering disability stereotypes (Oliver, 1990). Perhaps even more importantly, critics have also highlighted the exclusion of disabled members from positions of leadership within these organizations (Drake, 1994, 1996), thereby mirroring discrimination mechanisms operating more broadly in society. On the contrary, small membership groups have generally been indicated as the backbone of the British disability movement of the early 1990s, which shared the strong participatory ethos typical of new social movements (Oliver, 1997).

Although most of the empirical research substantiating these claims was carried out over a decade ago, to date there remain clear differences between organizations "of" and "for" disabled people (Oliver & Barnes, 2012). Such distinctions can crucially inform research on the performance of these groups as e-democratic actors. While traditional charities and many hybrid bodies remain bureaucratic, constantly concerned about fundraising targets, and increasingly close to government institutions (Barnes, 2007), self-advocacy groups tend to be small, non-hierarchical, resource-poor, and based on voluntary work (Drake, 1996). In this framework, key themes that emerged from previous research on online activism were instrumental in formulating reasonable expectations about the approach of Scottish disability organizations to online media. As originally pointed out by Pickerill (2004) in her study of environmental campaigners and corroborated by research on the peace movement (Olsson, 2008; Gillan, Pickerill, & Webster 2008), smaller, issue-based, non-hierarchical groups tend to benefit from the Internet in a disproportionate manner for aggregating people, mobilizing support, and building a collective identity while simultaneously entrusting individual supporters with control over campaign messages and decision-making. Thus, citizen-led, loosely-tied groups have been shown to be particularly attached to digital media as platforms for broadcasting otherwise marginalized views (Lievrouw, 2011: 159). This is in line with the expectation that groups underpinned by the participatory ethos typical of new social movements would be best placed to take advantage of innovative ICTs (Norris, 2002: 188-93). Conversely, established and institutionalized campaigning organizations have demonstrated an ambivalent attitude towards online media by virtue of the tension that exists between the Internet's open nature and innate organizational control impulses (Brainard & Siplon, 2002, 2004).

For these reasons, Scottish self-advocacy groups were expected to be especially keen on embracing participatory online platforms as a way to enhance their levels of internal pluralism and pursue their empowerment mission more effectively. Instead, it was reasonably assumed that traditional charities and, at least in part, hybrid bodies would prefer a more careful approach to technology, seeking to harness the Internet's potential for mobilization while at the same time minimizing the share of control granted to users. In assessing the veracity of these hypotheses, particular attention was paid to the relationship between Scottish disability organizations and Web 2.0 technology, including all those readily available platforms such as social media, blogs, forums, and multimedia sharing sites that allow Internet users to also become content producers. This is because such tools are particularly likely to stimulate intra-organizational democratization by enabling what Bimber, Flanagin, and Stohl (2012) have described as "entrepreneurial engagement," i.e. the possibility for users to create their own opportunities for involvement and promote an agenda genuinely based on their priorities and expectations.

In this context, organizations might assume a new role, not as filters, but rather as catalysts of participation capable of democratically aggregating different opinions into coherent messages. The result would be one of 'enhanced' pluralism in which the emergence of new voices is promoted but not 'managed,' while at the same time the risks of extreme fragmentation posed by online initiatives are averted. To what extent, then, do Scottish disability organizations embrace participatory online technology and provide 'ordinary' users with viable channels to contribute to their campaigns and initiatives? In order to tackle this question, a mixed-methods enquiry strategy was devised.

Research design and methods

In order to account for the entire range of Scottish disability non-profits and self-advocacy groups, this study scrutinized the Web presence of nine emblematic organizations, three per each one of the typologies discussed above (Table 1). These were purposively selected among organizations with extensive experience of participating in national disability policy debates. In addition, their websites ranked highly on Google.co.uk for a series of disability-related keyword searches. Although it could be argued that Google search results are not neutral as they are informed both by online traffic flows and the perceived credibility of those behind a given website (Introna & Nissenbaum, 2000), this does not detract from the fact that top-ranking URLs are those most likely to attract online traffic. As such, choosing such websites effectively mirrored the user-experience.

Table 1 - Scottish disability organizations selected for analysis

|

Organization |

Website |

Member-led groups |

Inclusion Scotland |

|

Glasgow Disability Alliance (GDA) |

||

Glasgow Centre for Inclusive Living (GCIL) |

||

Traditional charities |

Enable Scotland |

|

Quarriers |

||

Scottish Association for Mental Health (SAMH) |

||

Hybrid bodies |

Capability Scotland |

|

Spina Bifida Association Scotland |

||

Spinal Injuries Scotland (SIS) |

While this paper concentrates primarily on commonly held patterns within and across different group categories, a specific case study is brought into the spotlight in the second part of the analysis to discuss how formal disability organizations may seek to associate themselves with particularly successful user-initiated campaigns on social media. Undoubtedly, purposive selection and the limited size of the sample analyzed in this study restricted the possibility to generalize its results. However, given the seminal nature of this project, focusing on a limited number of high-profile organizations crucially enabled to explore this varied organizational ecology in great depth.

The first part of the analysis relied on 'on screen' investigation to capture and interpret the Web presence of these organizations. A coding frame was devised that included two distinct yet complementary sections. First, a number of variables were included with the aim of providing a comprehensive overview of the content posted on the websites of the groups listed above, with specific attention to content authorship and the occurrence of personal disability stories. Second, a matrix for recording interactive features was also created by drawing on previous attempts to map user-involvement on political websites maintained by parties (Gibson & Ward, 2000), candidates (Stromer-Galley, 2006), and grassroots activists (Gillan, 2009). Most of the options in this second part of the coding frame were created ex novo to account for recent developments in online communications. Thus, while the official websites of the groups under scrutiny were indeed adopted as starting points, this study stretched beyond a straightforward analysis of their content to sound their approach to social networking and video-sharing sites. All Web pages located up to three clicks from 'home' were coded individually, which gave a total of 766 entries (111 for the first group of websites; 391 for the second group; 264 for the third group).

As the aim of this study was also to identify the reasons at the root of the online media choices of Scottish disability organizations, the analysis was complemented by a series of semi-structured interviews with communication strategists and leaders from the groups under scrutiny. In addition to their centrality in disability research (Barnes, 1992a), in recent years qualitative methods have also been gaining increasing recognition in Internet enquiry (Rasmussen, 2008; Witschge, 2008). In total, nine in-depth interviews were carried out with representatives from six of the organizations listed above. These were instrumental to reach 'beyond screens' and contextualize the results of content analysis.

What is online and who controls it?

Overall, online content tended to cover topics that were coherent both with each group's specific aims and objectives and, more broadly, with their traditional rhetoric. As such, traditional charities and hybrid bodies placed strong emphasis on fundraising, which constituted the single biggest focus on their websites, occupying 22.8% and 25.4% of their Web pages respectively. This particular result was consistent with the results of previous work on non-profit organizations in the U.S. (Saxton, Guo, & Brown, 2007) but went beyond expectations for UK charitable organizations, which have access to a range of public funds that make them less dependant on private donations than their American equivalents. In contrast, fundraising was entirely absent from the websites of member-led groups. Rather, these focused more often on disability rights and campaigning, which together accounted for nearly 21% of their content. Furthermore, organizations from all three type groups dedicated considerable space to the promotion of their services. While this was anticipated for the Web pages maintained by traditional and hybrid organizations, it was surprising to find that 18.4% of those belonging to member-led groups focused on service-provision too. This ultimately reflected a growing tendency among these groups to provide services, including IT courses, as a way to promote independent living and self-advocacy for disabled people (Shakespeare, 2006: 157).

Results for content authorship revealed that the organizations were firmly in control of what appeared on the Web pages under scrutiny. Overall, staff members were the source of over 95% of the content analyzed for this project . This constituted a strong pattern that cut across the entire organizational spectrum and was subsequently corroborated by other results throughout the rest of the study. The only exception was Inclusion Scotland, which however stood out only because it drew a sizeable amount of its Web content from mass media sites as a way to provide supporters with an online disability news digest (Table 2).

Table 2 - Content authorship per organization type (share of total Web pages)

Source of Content |

Group Typology |

||

Member-led |

Traditional |

Hybrid |

|

Organization (staff) |

71.2% |

95.9% |

95.1% |

Users |

-- |

0.3% |

0.4% |

External source (mass media, institutions, etc.) |

23.4% |

0.8% |

0.4% |

Other |

1.8% |

0.3% |

-- |

n/c |

3.6% |

2.8% |

2.7% |

Intuitively, this could look like a reasonable state of affairs from an organizational point of view. However, such a strong centralization in content production was sharply at odds with an increasing tendency for successful online campaigns to require extensive input from users and personalized online messages (Bennett & Segerberg, 2011). In particular, it was surprising to find that, even when they included blog pages, the websites of member-led groups did not feature opportunities for users to comment and provide feedback. Instead, user-contributions about policy proposals and other disability issues were invited via e-mail — a closed, one-to-one circuit — and not displayed online as a means to foster public debate. Overall, this constituted a preliminary indication of the existence of a negative attitude towards participatory Internet tools among Scottish disability organizations, which in turn influenced the way in which personal stories of disability were included on their websites.

Personal stories: Un-mediated disability 'voices'?

All of the websites under scrutiny hosted personal stories of disability. Member-led groups and traditional charities included personal narratives on 9% and 9.5% of their Web pages respectively, while hybrid bodies fell just short of that at 7.6%. Indeed, this was expected of the Web outlets maintained by traditional and hybrid organizations by virtue of their experience with using personal accounts in fundraising and campaign material. In fact, on the websites of these organizations personal stories tended to cluster around pages dedicated to service-provision and fundraising (Table 3).

Table 3 - Location of disability stories on traditional charities websites

Website section |

|

Homepage |

5.4% |

About disability |

5.4% |

About the organisation's services |

45.9% |

Fundraising & volunteering |

13.5% |

News & events |

8.1% |

Disability rights & policy |

21.6% |

Instead, finding personal stories on nearly one in ten of the Web pages maintained by member-led groups was counter-intuitive as it clashed with their longstanding opposition to the use of such narratives due to their association with stigmatizing disability stereotypes such as those of 'victim' and 'able-disabled' (Barnes 1992b, 12; Barnett and Hammond 1999). Nevertheless, it ought to be noted that the majority of personal stories on the websites of self-advocacy groups concentrated on pages that dealt primarily with disability policy (40%) and discrimination issues (30%). Furthermore, these accounts were also consistently framed in accordance with the principles of the social model, meaning that they used individual examples to make points about broader disability 'themes' rather than focusing on single episodes per se (Iyengar, 1991).

Thus, the distribution of personal stories on the websites of Scottish disability organizations broadly matched initial expectations by mirroring the traditional rhetoric of different group typologies and supporting their specific objectives (Kenix, 2007). That said, it would be premature to assume that such accounts also provided 'ordinary' disabled users with an un-mediated online 'voice.' In fact, while a number of these stories were presented in the first person, organizational staff and group leaders were ultimately responsible for their publication on all the websites under scrutiny (Table 4). In other words, editorial control over personal narratives remained in the hands of the organizations. This cast severe doubts over the possibility to regard these stories as 'direct' disability accounts.

Table 4 - Sources of disability stories per organization type

|

Member-led Groups |

Traditional Charities |

Hybrid Bodies |

Posted directly by users |

-- |

-- |

-- |

Posted by staff |

40% |

29.7% |

60% |

Posted by staff |

50% |

67.6% |

35% |

Linked/embedded from other sites |

10% |

2.7% |

5% |

Indeed, there was no reason for which the veracity of these narratives should be questioned, as interviews confirmed that they had been volunteered by disabled supporters whose consent was also granted prior to publication. Nonetheless, this system still failed to challenge the traditional power differential that exists between leaders and ordinary users, who were prevented from sharing their own experiences free of editorial control as it has instead become common place on independent blogs and other interactive platforms (Goggin & Noonan, 2007; Thoreau, 2006).

Thus, all types of groups were aware of the value of highly 'personalized' messages in digital communications, but at the same time reluctant to delegate control to online supporters. From an organizational point of view, member-led groups did not behave any differently from disability charities and hybrid bodies, nor from political and media organizations more generally (Kensicki, 2001). They acted as communication 'filters' by selecting, contextualizing, and publishing personal stories on the basis of their potential contribution to a pre-determined agenda. For these reasons, and despite providing alternative portrayals of disability, these accounts failed to boost intra-organizational pluralism. This practice was at odds with user-oriented online technology, which in turn was also approached by these groups with extreme caution, as discussed in detail below.

User-engagement features

Overall, the Web presence of all the groups under investigation was characterized by a severe lack of interactive features. While Tables 5a and 5b provide an overview of the 'minimalist' approach to participatory technology that cut across all types of groups, a notable exception was represented by the presence of what could be labeled as 'clicktivism' tools on some websites.

Table 5a - User-engagement features per website as of end 2010 (member-led groups and traditional charities)

Feature |

Member-led groups |

Traditional charities |

||||

Inclusion Scotland |

GCIL |

GDA |

Quarriers |

Enable |

SAMH |

|

Online contact details |

Personal |

Personal |

Personal |

Generic |

Generic |

Generic |

Members-only area |

-- |

-- |

YES |

-- |

YES |

-- |

Forum |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

Chat room |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

Online polls |

YES |

-- |

YES |

YES |

-- |

-- |

Cyber-activism |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

YES |

-- |

Consultation space |

-- |

-- |

Email only |

Email only |

Email only |

-- |

Blogs |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

YES |

-- |

Table 5b - User-engagement features per website as of end 2010 (hybrid bodies)

Feature |

Hybrid bodies |

||

SSBA |

Capability Scotland |

SIS |

|

Online contact details |

Generic |

Generic |

Personal |

Members-only area |

-- |

- |

-- |

Forum |

-- |

-- |

-- |

Chat room |

-- |

-- |

-- |

Online polls |

-- |

YES |

-- |

Cyber-activism |

-- |

-- |

YES |

Consultation space |

-- |

Email only |

-- |

Blogs |

-- |

-- |

YES |

In particular, two out of three member-led groups included opinion polls on their websites. Furthermore, Enable and Spinal Injuries Scotland sponsored cyber-activism facilities such as e-postcards and online petitions. Nevertheless, each of these applications was arranged around pre-determined issues. This crucially restricted the choice available to users, preventing them from pushing forward their priorities and pursuing campaigns based on their own interests. This practice was consistent with the findings of previous work on the use of cyber-activism and e-consultation tools by other activist and institutional actors (Schlosberg, Zavestoski, & Shulman, 2007; Tomkova, 2009). As such, it amounted to a very basic level of user-input in e-advocacy, falling short of involving online supporters in agenda-setting.

The quest for interactive features also provided some preliminary insights into the views of Scottish disability organizations on social media. As expected of organizations that have often been described as resource-stretched and cash-strapped in both scholarly literature and media coverage of disability, it was unsurprising to find that no-one provided a custom-built forum or chat room (Tables 5a and 5b). Yet, for this very same reason, readily available social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube were expected to provide a low-cost, ubiquitous, and therefore attractive alternative for the pursuit of user-engagement. Nevertheless, at the time of data collection only traditional charities and hybrid bodies maintained a social media presence (Table 6). These results contradicted initial expectations, showing that self-advocacy groups were in fact lagging behind other disability organizations and non-profits more generally with regard to participatory technology (NTEN, 2012).

Table 6 - Connections to social networking sites (as of end 2010)

Organization Type |

Website |

Links to Social Media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) |

Predominant Type of Links to Social Media |

Member-led Group |

Inclusion Scotland |

NO |

-- |

GCIL |

NO |

-- |

|

GDA |

NO |

-- |

|

Traditional Charity |

Quarriers |

YES |

Other Disability Pages |

Enable |

YES |

Own Official Pages |

|

SAMH |

NO |

-- |

|

Hybrid Body |

SSBA |

YES |

Own Official Pages |

Capability Scotland |

YES |

Other Disability Pages |

|

SIS |

NO |

-- |

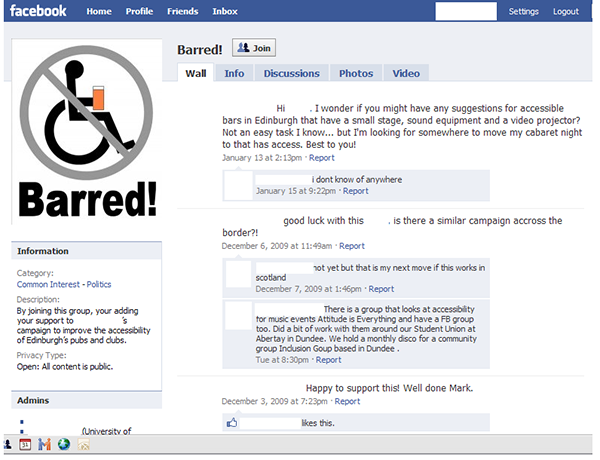

In recent years, individual disabled Internet users have started to address the absence of self-advocacy groups from social media platforms by launching independent, user-driven initiatives on relevant issues. Most notably, this was the case of several groups that sprung up on Facebook in the wake of the radical disability welfare reform introduced by the UK government between 2010 and 2012 (Trevisan, 2013). An important precursor to these spontaneous e-advocacy ventures was the Barred! campaign that took place in Scotland between 2009 and 2010. Created as a Facebook group by a "lone-wolf" activist (Earl & Kimpert, 2011) to raise the issue of poor accessibility standards in Scotland's bars and clubs, this campaign succeeded in pushing a key amendment to accessibility regulations for licensed premises through the Scottish Parliament in June 2010. Following an initial period, this user-driven campaign was eventually "adopted" by one of the organizations considered in this study: Capability Scotland. It is therefore particularly useful to discuss what lay behind this endorsement. Did this signal a genuine, pioneering opening from a leading disability organization towards participatory campaigning on social media, or was it rather just an attempt to neutralize an emerging competitor in the area of disability advocacy?

Social media campaigning: Disability advocacy in flux

Although this is not the place for a detailed analysis of group structure and Facebook use in Barred!, it ought to be noted that its founders were no strangers to the Scottish political game. In fact, one of them even stood as a Labour parliamentary candidate in the 2010 UK general election. This resonates with the findings of previous work on online activism that revealed how leading figures in digital dissent networks tend to be individuals who are already "rich" in political capital and involved in offline politics (Gillan, Pickerill & Webster, 2008). Undoubtedly, this clashes with the idea that online self-organizing may be equally as open to any Internet user. In addition, in the case of Barred! one also has to ask why its founders, after working to gather thousands of supporters on Facebook, chose to "franchise" their campaign out to Capability Scotland, whose logo suddenly appeared on the group's Facebook in June 2010 (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. - Barred! Facebook page in January (top) and June (bottom) 2010

(Personal information deleted to preserve user-privacy)

(Click images to enlarge.)

Interviews with those responsible for the Barred! Facebook page as well as Capability Scotland representatives revealed that the organization had become involved in the campaign after hiring one of its founders as an intern. Indeed, one may be cynically inclined to regard this as a cunning way for an established non-profit to co-opt an alternative online group into "mainstream" disability advocacy (Brainard and Siplon, 2002). Yet, interview participants explained that it was in fact Barred! founders who approached Capability Scotland for input. As one of the campaign leaders stated, this was necessary because

"an entirely online campaign would not have been so effective; it can only work as part of a package […] having the backing of a major charity with a good track record on campaigning did help: it enabled contacts that otherwise would have been impossible."

(Barred! founder)

Viewed in this light, Capability Scotland's involvement amounted to more than a mere attempt to jump on the bandwagon or, worse, hijack a successful user-driven campaign. Rather, it reflected the awareness that citizen-initiated online campaigning is unlikely to go far enough on its own legs and instead can benefit greatly from the endorsement of established organizations, which can act as fundamental support catalysts and credibility boosters in the public arena (Davey, 1999). Indeed, this type of arrangement requires "self-made" activists

"to think about the campaign in a different way, taking into account the organization's brand and priorities."

(Barred! founder)

However, this can be a relatively small price to pay in return for enhanced policy influence. In other words, by actively pursuing the support of a formal organization, Barred! founders explicitly recognised that in online campaigning there tends to be a trade-off between independence and overall efficacy. This example delineated an emerging e-advocacy context in which online citizen campaigners and established organizations are incentivized to join forces in the name of policy results. This will inevitably require both sides to compromise on certain things. For example, in the case of Barred! Capability Scotland's website linked to the campaign's Facebook page, but not vice-versa. This was part of a deliberate choice

"not to link pages on social networking sites to the main website since this way it all seems less corporate and gives people that personal touch that many are looking for."

(Capability Scotland, communications executive)

This revealed familiarity with user-expectations of spontaneity and 'amateurishness' on social media rather than a context dominated by household names.

Despite its significance as a successful collaborative campaign between online citizen-activists and a major disability organization, Barred! represented an exception in the emerging context of Scottish disability e-advocacy. As mentioned above, four out of six of the traditional charities and hybrid organizations considered for this study maintained links with social networking pages, especially Facebook. However, these invariably prevented users from initiating discussion threads or, in extreme cases, posting new content altogether. This was at odds with the participatory nature of social media (boyd & Ellison, 2007), signalling a seemingly paradoxical attempt to apply vertical control mechanisms to social networking platforms. Interviews provided rich insights into the reasons behind these choices, shading light onto the rationale that underpinned the approach of each type of disability group to online communications.

Looking beyond screens: Making sense of apparent contradictions

A first key finding was that paid staff were in complete control of all online communications across the entire organizational spectrum. Moreover, only two out of nine participants identified themselves as disabled, while everyone confirmed that they held either formal qualifications in media and communications management for the non-profit sector or considerable work experience in a similar role. Such preliminary observations echoed the growing tendency for member-led groups to become 'professionalized,' and thus somewhat 'distant' from those whom they seek to represent and empower (Oliver & Barnes 2006; Barnes, 2007). While in fact it would have been reasonable to expect paid members of staff to be responsible for day-to-day website maintenance, it was rather surprising to find that

"as little as possible is negotiated with the board of trustees because […] if we sought to engage them they would probably interfere too much,"

(Traditional charity, director)

and that

"trustees are generally presented with plans in a way that makes it difficult for them to say no."

(Traditional charity, director)

Participants from all types of organizations sanctioned this practice, specifying that they considered themselves — and not their members — to be in charge of the strategic aims of their group's Web presence. For these reasons, interviews revealed that all groups, regardless of their founding principles and overarching aims, shared an 'experts know best' approach to the Internet, which can be reasonably assumed to have contributed to the top-down control model outlined above.

It could have been tempting to assume that such centralized approach to online communications stemmed from an equally patronizing and disempowering attitude towards ordinary users and supporters. However, further analysis of interview accounts demonstrated that behind similar online media choices lay in fact very different rationales. Representatives of both traditional charities and hybrid bodies repeatedly stressed that

"we have a position, we have a view and we need to promote and defend that. We are not here to facilitate debate, […] so it is not as flexible as it might be for other organizations […] that can instead encourage debate and be the mediator; I mean, there is nothing wrong with debate but we have already taken a side."

(Hybrid organization, communications manager)

This resonated with the idea that the approach of these groups to different online platforms and applications was primarily guided by the potential of such tools to contribute to the realization of a pre-determined organizational agenda. Furthermore, this provided an additional demonstration of the fact that traditional charities and hybrid bodies were indeed aware of the 'democratizing' potential of Web 2.0, but also wary of embracing this technology in ways that could undermine their leadership and challenge their hierarchical structure. Although the Barred! campaign provided a glimpse of what the future of disability advocacy may look like, the bulk of social networking pages maintained by traditional charities and hybrid bodies presented a rather more 'conservative' picture. With regard to the purpose of Facebook, Twitter, and the others, participants clarified that

"[online] social networking is useful for fundraising,"

with the additional benefit that

"being more informal than the [organization's official] website, people could respond better to it."

(Traditional charity, communications manager)

Furthermore, representatives of traditional charities and hybrid bodies explicitly dismissed the possibility that disabled Internet users may wish to contribute their own content and take part in online debates, stating instead that their respective Web outlets constituted

"mainly an information board, another way to facilitate access to important resources for disabled members."

(Traditional charity, communications manager)

This led them to believing to be

"doing the best interest of disabled members by providing them with all the information they need and they are looking for."

(Hybrid body, communications manager)

This corroborated the impression that charitable organizations and hybrid bodies regarded disabled Internet users as information recipients rather than content producers, an assumption that continues to underpin social media communications for non-profits operating across a series of different areas (Lovejoy, Waters & Saxton, 2012). As such, social media were mainly interpreted as additional marketing and PR tools or, at best, channels to mobilize users around pre-arranged, vertically controlled initiatives. This recalled the online strategy pursued until very recently by major European political parties, which combined the adoption of Web 2.0 features with a more traditional approach to online communications, falling short of promoting internal pluralism and ultimately resulting in what Lilleker and Jackson (2011) have described as 'Web 1.5.'

Conversely, interviews with member-led groups revealed that these were characterized by an opposite perspective on disabled users. In particular, these were invariably seen as

"very interested in IT, above all those with mobility impairments"

(Member-led group, communications officer)

and consistently referred to them as the "main target audience" of these groups' Web outlets. Furthermore, self-advocacy groups were also keen on stressing that

"it is important to provide more opportunities for direct interaction: if disabled people don't see the website as just an information board they will be more likely to participate."

(Member-led group, communications officer)

This and similar remarks implicitly acknowledged the aspiration of disabled users to be more than passive information recipients.

Indeed, this type of statements were in open contradiction with the lack of participatory features on the websites of member-led groups and, even more so, their reluctance to embark on social media platforms. Nevertheless, this apparent paradox was also explained by references to the obstacles that prevented these very same groups from engaging in more sophisticated forms of online communication. As explained by interview participants, these included lack of resources, barriers to Internet access and IT literacy for many disabled people, as well as accessibility issues. These elements persuaded the leadership of member-led groups that it would be somewhat

"pointless to try and communicate with them via the Internet."

(Member-led group, chair)

Ultimately, these views encouraged member-led groups to invest their limited resources in other, less innovative but at the same time more reliable forms of communication to ensure that their message would reach as many disabled people as possible. Given the long-term experience of these groups in communicating with the Scottish disability community, statements like the last one above invite a reflection on whether their 'minimalistic' approach to Web 2.0 technology should in fact be considered 'pragmatic' rather than out-dated or potentially disempowering. Nonetheless, the choice to keep out of social media also meant that these groups traded off important opportunities to reach and engage new 'audiences,' particularly among young disabled people.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the promise of 'enhanced' pluralism and representativeness through interactive online media was generally not realized for Scottish disability organizations. All the groups under scrutiny, irrespective of their structure and underpinning ethos, had embraced only very basic participatory tools. Websites were primarily understood as information boards, social media regarded with skepticism, and efforts deployed to ensure top-down control over online communications. Furthermore, all groups were also found to be acting as alternative 'filters' of online content by disallowing direct user-control and arbitrarily selecting, editing, and integrating personal disability narratives on their websites in accordance with pre-determined objectives. This constituted a potentially disempowering practice as it could be argued that disability organizations were effectively appropriating the online voices of disabled users to pursue their own strategic aims.

Yet, at the same time it would be misleading to assume that such 'minimalist' approach to interactive media was the result of the same underlying strategy for all the groups considered in this study. Instead, basic differences between member-led groups on one side and traditional as well as hybrid organizations on the other emerged as key determinants for seemingly identical online media choices. Despite traditional charities and hybrid bodies had embarked upon social media platforms, they also perceived and tentatively used those applications as top-down mobilization tools. In contrast, member-led groups showed awareness of the empowering potential of interactive technology for disabled users, but their experience in communicating with the Scottish disability community suggested that investing resources in an extensive presence on participatory media would be ineffective, at least for the time being.

Overall, this study revealed that the approach of Scottish disability organizations to the Internet was at odds with Finkelstein's technological utopia cited at the beginning of this paper. More broadly, this investigation provided a powerful reminder that the realization of the Internet's potential for citizen empowerment is strongly conditioned by both environmental constraints and incentives to online participation. Indeed, the results of this study are limited by the fast pace of technological development in the online realm, which makes online activism a moving target and sweeping generalizations ill-advised. However, the Barred! campaign, while constituting an isolated case in the Scottish disability advocacy landscape so far, showed that social media may provide disabled Internet users dissatisfied with the ways in which existing organizations represent their interests in the public arena with alternative channels to make their voice heard. Thus, while continuing to monitor the Web presence of existing disability organizations, it is of paramount importance that researchers watch out for innovation in this area from 'self-made' activists and emerging online networks that have nothing but to gain from an intense social media presence.

The author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Economic and Social Research Council, award nr. ES/G01213X/1 — Disabled people, the Internet, and participation: Building a better society?

References

- Anderberg, P., & Jönsson, B. (2005). Being There. Disability & Society, 20(7): 719-33.

- Barber, B. R. (1984). Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Barnes, C. (1992a). Qualitative research: Valuable or irrelevant? Disability, Handicap & Society, 7(2): 115-24

- Barnes, C. (1992b). Disabling imagery and the media. Halifax: BCODP/Ryburn Publishing.

- Barnes, C. (2007). Disability Activism and the Struggle for Change. Education, Citizenship, and Social Justice, 2(3): 203-21.

- Barnes, M., Newman, J., & Sullivan, H. (2007). Power, participation and political renewal. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Barnett, J., & Hammond, S. (1999). Representing disability in charity promotions. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 9: 309-14.

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2011). Digital Media and the Personalization of Collective Action: Social Technology and the Organization of Protest Against the Global Economic Crisis. Information, Communication and Society, 14(6): 770-99.

- Bimber, B., Flanagin, A., & Stohl, C. (2012). Collective Action in Organizations: Interaction and Engagement in an Era of Technological Change. Cambridge: CUP.

- Boyd, D., & Ellison, N. (2007). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1).

- Brainard, L. A., & Siplon, P. D. (2002). Cyberspace challenges to mainstream nonprofit health organisations. Administration & Society, 34(2): 141-75.

- Brainard, L. A., & Siplon, P. D. (2004). Toward Nonprofit Organization Reform in the Voluntary Spirit: Lessons from the Internet. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(3):435-57.

- Burt, E., & Taylor, J. (2008). How well do voluntary organisations perform on the web as democratic actors? Towards an evaluative framework. Information, Communication and Society, 11(8): 1047-67.

- Campbell, J., & Oliver, M. (1996). Disability politics: Understanding our past, changing our future. London/New York: Routledge.

- Chadwick, A. (2007). Digital Network Repertoires and Organisational Hybridity. Political Communication, 24: 283-301.

- Craig, G., & Taylor, M. (2002). Dangerous liaisons: Local government and the voluntary and community sector. In Glendinning, C., Powell, C., & Rummery, K., (Eds.), Partnerships, New Labour and the governance of welfare, Bristol: The Policy Press, pp. 131-48.

- Davey, B. (1999). Solving Economic, Social and Environmental Problems Together: An Empowerment Strategy for Losers. In Barnes, M., & Warren, L. (Eds.), Paths to Empowerment, Bristol: The Policy Press, pp. 37-49.

- Dobransky, K., Hargittai, E. (2006). The disability divide in internet access and use. Information, Communication, and Society, 9(3): 313-34.

- Drake, R. F. (1994). The exclusion of disabled people from positions of power in British voluntary organizations. Disability & Society, 9(4): 461-80.

- Drake, R. F. (1996). Charities, authority and disabled people: A qualitative study. Disability & Society, 11(1): 5-23.

- Drake, R. F. (2002). Disabled people, voluntary organisations and participation in policy making. Policy & Politics, 30(3): 373-85.

- Dutton, W., & Blank, G. (2011). Next Generation Users: The Internet in Britain. Oxford: Oxford Internet Institute.

- Earl, J., & Kimpert, K. (2011). Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Ellis, K., & Kent, M. (2011). Disability and New Media. London: Routledge.

- Finkelstein, V. (1980). Attitudes and disabled people. Washington,DC: World Rehabilitation Fund.

- Foot, J. (2009). Citizen involvement in local governance. Round Ups, June 2009,York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Gibson, R., & Ward, S. (2000). A proposed methodology for studying the function and effectiveness of party and candidate web sites. Social Science Computer Review, 18(3): 301-19.

- Gillan, K. (2009). The UKAnti-War Movement Online: Uses and Limitations of Internet Technologies for Contemporary Activism. Information, Communication, and Society, 12(1): 25-43.

- Gillan, K., Pickerill, J., & Webster, F. (2008). Anti-war activism: New media and protest in the information age. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goggin, G. (2011). Disability, Mobiles, and Social Policy: New Modes of Communication and Governance. In Katz, J. (ed.), Mobile Communication: Dimensions of Social Policy, New Brunswick: Transaction, pp. 259-72.

- Goggin, G., & Newell, C. (2003). Digital disability: The social construction of disability in new media. Lanham: Rowan & Littlefield.

- Goggin, G., & Newell, C. (2004). Disabled E-nation: Telecommunications, Disability and National Policy. Prometheus, 22(4): 411-22.

- Goggin, G., & Noonan, T. (2007). Blogging Disability: The Interface between New Cultural Movements and Internet Technology. In Bruns, A., & Jacobs, J. (Eds.), Uses of Blogs. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 161-72.

- Keating, M. (2010), The government of Scotland: Public policy making after devolution (2nd Ed.), Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Kenix, L. J. (2007). In search of utopia: An analysis of non-profit web pages. Information, Communication and Society, 10(1): 69-94.

- Kenix, L. (2008). Nonprofit Organisations' Perceptions and Uses of the Internet. Television & New Media, 9(5): 407-28.

- Kensicki, L. J. (2001). Deaf president now! Positive media framing of a social movement within a hegemonic political environment, Journal of communication enquiry 25(2): 147-66.

- Introna, L. D., & Nissenbaum, H. (2000). Shaping the Web: Why the Politics of Search Engines Matters. The Information Society, 16(3): 169-85.

- Iyengar, S. (1991). Is anyone responsible? How television frames political issues. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Lievrouw, L. (2011). Alternative and Activist New Media — Cambridge: Polity.

- Lilleker, D., & Jackson, N. (2011). Political Campaigning, Elections and the Internet: Comparing the US, UK, France, and Germany. London: Routledge.

- Lovejoy, K., Waters, R., & Saxton , G. (2012). Engaging Stakeholders through Twitter: How Nonprofit Organizations Are Getting More Out of 140 Characters or Less. Public Relations Review, 38(2): 313-8.

- Maxwell, S. (2007). The voluntary sector and social democracy in devolved Scotland. In Keating, M. (Ed.). Scottish social democracy: Progressive ideas for public policy. Brussels: Peter Lang, pp. 213-36.

- Morris, J. (2005). Citizenship and disabled people: A scoping paper prepared for the Disability Rights Commission. Leeds: University of Leeds Centre for Disability Studies.

- Mourdant, J. (2006). The emperor's new clothes: Why boards and managers find accountability difficult. Public Policy and Administration, 21(3): 120-34.

- Nonprofit Technology Network — NTEN (2012). 4th Annual Nonprofit Social Network Benchmark Report. Available online at:

- http://www.nten.org/research/the-2012-nonprofit-social-networking-benchmarks-report

- (accessed 10th May 2013)

- Norris, P. (2001). The Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P. (2002). Democratic phoenix: Reinventing political activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oliver, M. (1990). The politics of disablement. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education.

- Oliver, M. (1997). The disability movement is a new social movement! Community Development Journal, 32(3): 244-51.

- Oliver, M., & Barnes, C. (2006). Disability policy and the disability movement in Britain: Where did it all go wrong?. Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People, August 2006.

- Oliver, M., & Barnes, C. (2012). The New Politics of Disablement. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Olsson, T. (2008). The practices of internet networking — A resource for alternative political movements. Information, Communication and Society, 11(5): 659-74.

- Pickerill, J. (2004). Rethinking political participation: Experiments in internet activism in Australiaand Britain. In Gibson, R., Römmele, A., & Ward, S. (Eds.), Electronic democracy: Mobilisation, organisation and participation via new ICTs, London: Routledge, pp. 170-93.

- Pilling, D., Barrett, P., & Floyd, M. (2004). Disabled people and the internet: Experiences, barriers and opportunities. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Rasmussen, K. B. (2008). General approaches to data quality and internet-generated data. In Fielding, N., Lee, R. M., & Blank, G., (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods, London: SAGE, pp. 76-96.

- Roulstone, A. (1998). Enabling Technology: Disabled People, Work, and New Technology. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Saxton, G., Guo, C., & Brown, W. (2007). New Dimensions of Nonprofit Responsiveness: The Application and Promise of Internet-Based Technologies. Public Performance and Management Review, 31(2): 144-73.

- Schlosberg, D., Zavestoski, S., & Shulman, S. (2007). Democracy and e-rulemaking: Web-based technologies, participation, and the potential for deliberation. Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 4(1): 37-55

- Schur, L., Shields, T., & Schriner, K. (2005). Generational cohorts, group membership and political participation by people with disabilities. Political Research Quarterly, 58(3): 487-96.

- Shakespeare, T. (2006). Disability rights and wrongs. London: Routledge.

- Sheldon, A. (2004). Changing technology. In Swain, J., French, S., Barnes, C., & Thomas, C. (Eds.), Disabling barriers — Enabling environments. London: SAGE, pp. 155-60.

- Stromer-Galley, J. (2006). Online Interaction and Why Candidates Avoid It. Journal of Communication, 50(4): 111-32.

- Thoreau, E. (2006). Ouch!: An Examination of the Self-representation of Disabled People on the Internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2): 442-468.

- Tomkova, J. (2009). E-consultations: New tools for political engagement of facades for political correctness?. European Journal of E-Practice 7, March.

- Trevisan, F. (2013). Disabled People, Digital Campaigns, and Contentious Politics: Upload Successful or Connection Failed? In Scullion, R., Lilleker, D., Jackson, D., & Gerodimos, R. (Eds.), The Media, Political Participation, and Empowerment, London: Routledge, pp. 175-91.

- Vicente, M., & Lopez, A. (2010). A Multidimentional Analysis of the Disability Digital Divide: Some Evidence for Internet Use. The Information Society, 26(1): 48-64.

- Warschauer, M. (2003), Technology and Social Inclusion: Re-thinking the digital divide. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Watson, N. (2012). Researching Disablement. In Watson, N., Roulstone, A., & Thomas, C. (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, London: Routledge, pp. 93-105.

- Williams, B., Copestake, P., Eversley, J., & Stafford, B. (2008). Experiences and expectations of disabled people. London: Office for Disability Issues.

- Witschge, T. (2008). Examining Online Public Discourse in Context: A Mixed Method Approach. Javnost/The Public, 15(2): 75-92.