In this essay we discuss the strategies and concepts behind two separate disability arts exhibitions we co-curated at Davidson College in 2009: RE/FORMATIONS: Disability, Women, and Sculpture and STARING. First, as curators who have mounted two disability arts exhibitions in the context of a small liberal arts college, we offer insights from our practical experience related to conceptualizing and producing a show focused around disability and art: its shape, funding, and display. It is our hope these will be useful to curators, but also to those who have little or no curatorial experience. Our comments will emphasize the context of the liberal arts college, but many of the central issues we confronted would be relevant to mounting such exhibitions in other settings. Second, in discussing the dialogues about disability that emerged within and from our two exhibitions, we want to provide some answers from our own experience to the question: what compelling issues and ideas emerge at the intersection of access, disability aesthetics, and art when creating such exhibitions?

Let us start, appropriately, with an image, specifically Chris Rush's conté crayon drawing "The Accomplice," (Fig. 1) which was displayed in STARING, one of the art exhibitions to be discussed in this essay. In it, two young men with intellectual disabilities stand side by side; the one in the center is slightly taller, with brown hair and an orange shirt; a young man with Down syndrome stands to his left, with blonde hair and a blue shirt. The white space to the right of the center figure is empty; both young men stare at us calmly and forthrightly, as though inviting our returned look. We like this image as a start to what we will discuss for a number of reasons. It renders disability visible in a way that resists pity, exoticism, or demonization; rather, this appealing portrait represents intellectual disability as ordinary lived experience. As the title suggests, it invites us to know these young men as friends to one another and also to become the accomplice not yet pictured. After all, that blank space next to them is also a place to stare at, one in which we are invited to imagine ourselves inserted, and thus becomes a symbol for the potential we all have to enter into community with them. But that space has a double meaning: if it is potential presence, it is also palpable absence, a place to mark whose experience has not been recognized, whose history has been neither understood nor recorded, whose existence has been erased because their disabled life was not considered worth living. That all these elements combine so richly through one disability image begins to suggest some of the transformative power of creating exhibitions centered at the nexus of disability and art.

Figure 1. Chris Rush, The Accomplice, 2009, conté crayon on paper, 25 x 19 in. (63.5 x 48.3 cm). Collection of the artist

This essay was motivated by a plenary presentation we gave for the symposium "In/Visible: Disability in the Arts" at Haverford College, and two central ideas motivate it. 1 First, as curators who have mounted two disability arts exhibitions in the context of a small liberal arts college, we want to offer insights from our practical experience related to conceptualizing and producing exhibitions focused around disability and art: its shape, funding, and display. It is our hope these will be useful to curators, but also to those who have little or no curatorial experience. Our comments will emphasize the context of the liberal arts college, but many of the central issues we confronted would be relevant to mounting such exhibitions in other settings. Second, in discussing the dialogues that emerged within and from our two exhibitions, RE/FORMATIONS: Disability, Women, and Sculpture (Fig. 2) and STARING (Fig. 3), we want to provide some answers from our own experience over the last few years to some central questions about disability aesthetics, namely, what is at stake in terms of access, aesthetics, and art when creating such exhibitions? We have written this essay as a conversation, the better to reflect our experiences as co-curators, both where they converged and diverged. 2

Figure 2. Installation view of RE/FORMATIONS: Disability, Women, and Sculpture, Van Every Gallery, Davidson College, 2009

JESSICA: The planning for the first exhibition that Ann and I co-curated, RE/FORMATIONS: Disability, Women, and Sculpture, began in 2007 while I was the assistant curator for the Van Every/Smith Galleries at Davidson College. At the time, I was investigating the role of female artists represented in sculpture gardens in the United States and also beginning to explore the field of disability studies. These seemingly disparate projects began to merge as questions raised in the field of disability studies started to inform the questions I was asking about the role of female artists in sculpture gardens: for whom are certain art-making materials (specifically those associated with public sculpture such as bronze, steel, or marble) physically and financially accessible? Who has been able to claim the public sphere as an artist? How do physical and mental differences, as well as gender differences, inform who we are, what we create, and how others perceive us?

It struck me that creating an exhibition addressing some of these questions is exactly what a small liberal arts gallery should be doing. Museums and galleries not associated with institutions of higher education sometimes find it difficult to present exhibitions with particular political and social points of view because of indirect push back, if not outright censorship, from their private funders, public officials, or the local community. 3 RE/FORMATIONS and STARING affirm the role of college and university art galleries to exhibit underrepresented, politically unpopular, or socially stigmatized points of view in order to fulfill the primary purpose of institutions like Davidson College, the stated mission of which is to "assist students in developing humane instincts and disciplined and creative minds for lives of leadership and service." 4 What could be more humane than recognizing the diverse embodiments that constitute our world? What could be more important for those poised to lead lives of leadership and service than to recognize the multiple ways in which access to healthcare, employment, and independence has been apportioned in our society according to ability?

RE/FORMATIONS required a level of scholarship and expertise that was first attained with the involvement of Ann Fox, a Davidson College faculty member and disability studies scholar. She graciously agreed to act as co-curator, and together we selected five artists to feature in RE/FORMATIONS: Nancy Fried, Harriet Sanderson, Rebecca Horn, Judith Scott, and Laura Splan, all of whom created art that we found compelling and who represented various manifestations of disability identity. Conceptualizing disability identity not as a monolith, but as variegated and nuanced, was essential to our curatorial process. We wanted to feature artists who were physically and cognitively disabled, canonical artists who could be re-read from a disability perspective, and also artists who while not personally claiming disability identity, still wanted to engage with aspects of it through art. RE/FORMATIONS opened in January of 2009 at Davidson College's Van Every Gallery and then traveled in April of that year to The National Institute for Art and Disabilities in Richmond, California.

The collaboration between Ann and me rendered such successful results in creating a well-attended and well-received exhibition that it seemed productive to continue this collaboration. The next opportunity came after I read Rosemarie Garland-Thomson's book, Staring: How We Look. A book that critically investigated the productive possibilities of the act of staring, it was filled with evocative works of art that I yearned to see in person. I brought the proposal for a project based on the book to Ann and we decided to create a second exhibition that drew on the scholarship of Garland-Thomson. In the process of doing so, we also looked to the Davidson College permanent art collection for new examples of the kinds of engagement with staring she had described in her book. The result was our next collaborative exhibition, STARING. We featured over thirty artists, including numerous works from Doug Auld and Chris Rush, and a smaller selection from Diane Arbus, Weegee, Nan Goldin, and Andy Warhol. Although not intentional, STARING consisted entirely of two-dimensional works (painting, photography, and drawing) in contrast to RE/FORMATIONS's three-dimensional focus on sculpture and installation work.

ANN:The exhibitions were a place to shape our own explorations of disability; Jessica wanted to learn more about the intersection of disability and gender in sculpture, while I wanted to extend my work understanding disability's deployment in culture beyond literary texts. This is not meant to downgrade the importance of the literary, but rather to model for our viewers the kind of "visual activism" and "activist museum practice" to which Garland-Thomson and Richard Sandell have respectively referred, and to complicate the ways in which disability studies scholars and activists can get inadvertently trapped by a search for examples that might only reflect our own contemporary sense of what a politically efficacious depiction of disability might look like. 5 We think it is importance to take a multivaried approach to disability in the visual arts, emphasizing nuance and context in considering the implications of diverse representations.

The multiple kinds of artistic presence in both exhibitions were important for reinforcing the complexity and variation within disability identity. For example, including work in RE/FORMATIONS such as Rebecca Horn's allowed for the re-reading of a canonical feminist artist's work through her disability experience, eschewing the more traditional notion that she succeeded simply "in spite of" her impairment. Beyond that switch in how the biographical disability experience is cast, however, other artists' inclusion in both exhibitions became an opportunity for further invigorating thinking about how disability is both embodied and represented.

Figure 4. Judith Scott, Untitled (JS 27), 1997, mixed media (fiber and found objects), 31 x 30 x 30 in. (78.7 x 76.2 x 76.2 cm). Creative Growth Art Center

One question we engaged across both exhibitions was who represents disability and how: why, for instance, might it be important to include an artist like Judith Scott, whose intricately layered and wrapped sculptures posit a challenge to the traditional materials of sculpture through experimenting with shape and form, yet whose intellectual disability and inability to articulate an artistic intent would seem to preclude her from familiar ways of identifying who makes art? For example, in one of her untitled sculptures (Fig. 4) featured in RE/FORMATIONS, we see how multilayered her work is: here, two cardboard spools are lashed together, and sit atop a mound of intricately interwoven ribbon and yarn in pink, blue, green, black, and white; the spools are themselves wrapped in white yarn and are intersected by a paper towel tube. At the back are a computer monitor shade and a round biscuit tin; the whole piece is mounted on a cardboard box that is smaller than the diameter of the sculpture, and echoes the play with circles and squares repeated again and again in the work. Scott, although unable to directly articulate her disability experience or artistic philosophy, still suggests both in the creation of the works. The intense binding of objects both secured and secreted away seems to suggest the years and experiences obscured within her history of institutionalization; the repetition of patterns and shapes suggests the articulation of a complex sense of time and space.

Figure 5. Laura Splan, Trousseau Series, 2009, machine embroidery with thread on cosmetic facial peel, bamboo, mixed media, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist

Figure 6. Laura Splan, Trousseau Series, detail of embroidery hoop, Subcutaneous, 2009, hand embroidery with thread on cosmetic facial peel, wood embroidery hoop, diameters range from 6" - 7". Collection of the artist

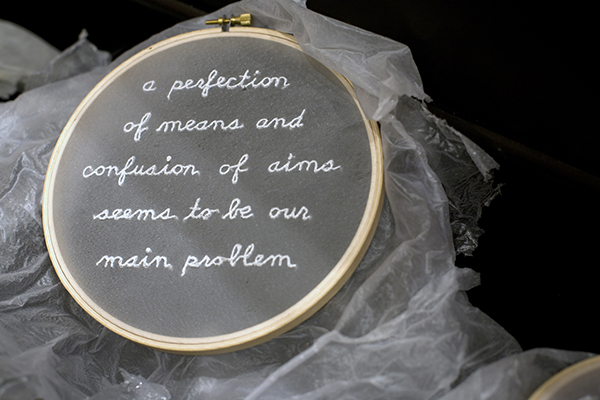

What does it mean to encounter art that does not emerge from its creator's disability identity, yet still engages the hegemony of normalcy? Laura Splan's work for RE/FORMATIONS does so, with its understanding of the artificially constructed, potentially constricting systems of science and gender classification. In the Trousseau Series (Fig. 5), commissioned for RE/FORMATIONS, Splan created a hope chest's worth of delicate female items out of the residue of facial chemical peel: a purse, fan, negligée, gloves, and other totems of hyperfemininity meant to be put on. Closer examination of one of these items suggests this interconnection: an embroidery hoop, holding "fabric" made of facial chemical peel, it is embroidered with images of chromosomes (Fig. 6). Totems of the beauty myth, the domestic, and genetic identity merge here strikingly, as Splan suggests the extent to which we attempt, through social convention and scientific knowledge, to embroider identity into place as a fixed and defined thing. What, after all, do we then do with the knowledge we seem to have settled upon? Another embroidery hoop suggested this dilemma, its fabric inscribed with a quotation from Albert Einstein: "A perfection of means, and confusion of aims, seems to be our main problem" (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Laura Splan, Trousseau Series, detail of embroidery hoop, Subcutaneous, 2009, hand embroidery with thread on cosmetic facial peel, wood embroidery hoop, diameters range from 6" - 7". Collection of the artist

Figure 8. Doug Auld, Brian, 2005, oil on linen, 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm). Collection of the artist

What might it mean to encounter work like that of Doug Auld (Fig. 8), an artist featured prominently in STARING, whose series of paintings of burn survivors expresses his personal connection with their community, and belies the simplistic reduction of their lives to narratives of tragedy and suffering? Time and time again, viewers of the exhibit expressed sadness for the burn survivors pictured. Yet upon closer inspection, observing Auld's brilliant colors and bold brushstrokes, they could see that he was investing these subjects with vitality, inviting the viewer to move outside her presumptions about what life with a disability might be like. What is more, the luminosity and dignity of the subjects, and Auld's brilliant and vivid depiction of their scars, constantly destabilized the line between the kinds of scarification or body modification we see as beautiful and that which we see as ugly or tragic. It is important to note as well that the presence of Splan and Auld (among others) in the shows as nondisabled artists who did not claim to be embracing disability activism, compels us to ask: why might it matter to see disability presence in art as more than the exclusive creation or purview of the disabled artist? How might it open up our understanding of the way disability's presence is interwoven into the history of modern and contemporary art, as Tobin Siebers avers in Disability Aesthetics? How might it suggest the ways in which disability thinking, and its retort against normalcy, connects to all kinds of experiences?

JESSICA: RE/FORMATIONS and STARING are exhibitions that shared the theoretical framework of disability studies, but were logistically very different projects. For RE/FORMATIONS we had two years to plan the exhibition, lending us the time to submit grants to various local and national organizations, which yielded us a substantial budget. 6 In contrast, we organized STARING in six months, not enough time to apply for most grants, so we relied on generous funding from Davidson College. We were fortunate to get the funding we did, but our budget for STARING was less than one-quarter of the budget we had for RE/FORMATIONS.

Often curators organize exhibitions around artists they've heard about from other curators, or seen at previous exhibitions, or read about in art journals and scholarly books. However, because there have been so few art exhibitions organized around the concept of disability identity and because categories like "disabled artist" or "disability art" cannot yet be found in most journals and books, the curatorial process for both RE/FORMATIONS and STARING is best characterized as broad and organic. Our alternative methods for locating artists combined word-of-mouth with Google searches and ultimately being flexible enough to allow accidents to turn into opportunities. Connecting with other disability artists and disability art organizations was certainly one of the highlights of the entire process. We were, and are, particularly indebted to the advice of disability artist, curator, and activist, Riva Lehrer.

Figure 9. Harriet Sanderson, Molt, with Scurs, detail of shoe, 2008, shoes and altered wood walking canes. Collection of the artist

Figure 10. Nancy Fried, Torso with Hands on Hips, 1994, terra-cotta, 12 x 17.25 x 7 in. (30.48 x 43.82 x 17.78 cm). Collection of the artist

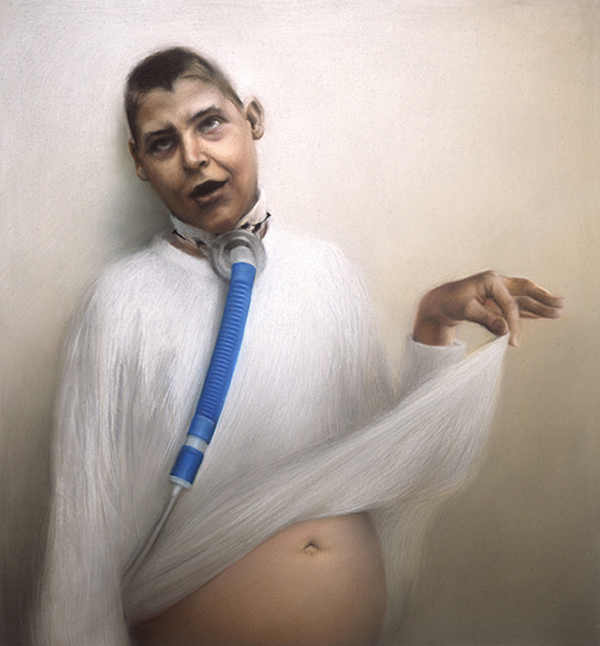

ANN: As Jessica suggests, putting disability and art into conversation caused a kind of multiplicity of effects. We saw both exhibitions creating an understanding of how disability embodiment informs the creativity of the artists in our exhibitions, whether through expressing how physicality influences their artistic creation, or underscoring their ways of expressing a fuller range of human embodiment. Disability's interface with art also challenged the traditional viewing experiences for our audience members. Some visitors passing through the galleries on a campus tour, upon being told RE/FORMATIONS was an exhibit on disability art, wondered where the wheelchairs were. We delighted in such a response; it meant these accidental attendees had been compelled to reconsider their own expectations about what the representation of disability in art meant. Encountering a piece like the blue, high-heeled shoe where the curved handle of a cane replaces the shoe's "amputated" original heel, a detail in Harriet Sanderson's installation Molt, with Scurs, (Fig. 9) meant understanding the cane not as medical object but as disability couture, disability-as-sexy, and disability cool. For some, the same image could alternately invoke empowerment or anxiety. So for example, the Nancy Fried sculpture entitled Torso with Hands on Hips (Fig. 10) figured prominently in RE/FORMATIONS and its publicity. The image is of a white terra-cotta bust of a woman that cuts off at the neck and hips; she is a breast cancer survivor who has her left breast and a mastectomy scar on the right side of her torso. Her hands are on her slightly torqued hips, and her posture seems one of defiance. This sculpture alternately invokes and answers back to the Venus de Milo, refusing to render what is missing by the distraction of an idealized torso. The sculpture elicited both an outraged call from one viewer who found it offensive, and a delighted email from a breast cancer survivor who had recently had a mastectomy, and laughed out loud with joy when she saw embodied in Fried's work the potential of what her new body could be. Clearly the former response said everything about the fear of disability still circulating so pervasively in our society. But in response, our exhibits claimed visibility for disability; they said: it is real, it is here, it exists as an identity, and we are going to show it to you. We are going to be frank, and frankly playful, as in the Chris Rush portrait Blue Tube (Fig. 11) featured in STARING: a conté crayon drawing which recasts the medical model as a kind of "medical drag." In it, we see a young man with short brown hair who is wearing a white hospital gown, which is suggested by long, luxurious white crayon strokes. A breathing tube, in a deep aqua blue, cuts across his chest to connect at his throat as he delicately and coyly lifts one corner of his hospital gown to reveal warm belly flesh underneath. As in this image, we placed front and center the real bodies that so often either get metaphorized out of existence or outright ignored, and also challenged the ways of viewing that direct us to recognize disability in highly specific, directed ways. As Siebers has written, "The figure of disability checks out of the asylum, the sick house, and the hospital to take up residence in the art gallery, the museum, and the public square". 7

Figure 11. Chris Rush, Blue Tube, 2006, conté crayon on paper, 36 x 32 in. (91.44 x 81.28 cm). Collection of the artist

JESSICA: Putting art and disability together in an exhibition is not new. The 2006 exhibition, Humans Being: Disability in Contemporary Art that Riva Lehrer co-curated with Sofia Zutautas at the Chicago Cultural Center provided an important model for disability art exhibitions. 8 The continued importance of Lehrer's exhibition is exemplified by its recent and spectacular sequel, Humans Being II, featured prominently as a part of the 2013 Bodies of Work Festival in Chicago. 9 Lehrer's skillful work as a curator with the disability arts community-at-large, and as an artist, continues to motivate others like Ann Fox and myself to create exhibitions and initiatives rooted in the investigation of disability identity. 10

Yet, other exhibitions address disability and art in less productive ways, more interested in the spectacle of disability or fulfilling common tropes about disability art and identity. In order to avoid any misconceptions about the nature of RE/FORMATIONS and STARING, mailings were sent out prior to the gallery openings to inform the public that these exhibitions did not address therapy or charity, but presented art born out of disability culture that is both activist and aesthetically innovative. For example, and as Ann discussed earlier, Nancy Fried's Torso with Hands on Hips (Fig. 10) was published in Davidson College's monthly arts calendar, and generated conflicting reactions from some of the readers. To most people living in the age of what Barbara Ehrenreich calls "the cult of pink kitsch," we are more accustomed to seeing a pink ribbon pinned over missing breasts than Nancy Fried's Torso with Hands on Hips. 11 We hoped that Fried's unexpected conceptualization of breast cancer on the cover of Davidson College's arts calendar would signal to our audience that this was not an exhibition to raise money for charities, but one that would openly defy the typical stereotypes about disability identity.

Figure 12. Anne and Marco Cibola, of Studio Ours Inc., RE/FORMATIONS: Disability, Women, and Sculpture logo, 2008.

All of the mailings and literature generated for RE/FORMATIONS included the branded logo (Fig. 12) for the exhibition created by the Ontario-based design team Anne and Marco Cibola. Working with the themes and artwork presented in RE/FORMATIONS, the Cibolas created a logo using their own slightly modified version of Helvetica font. Helvetica, they explained to us, is recognized as the normative font on which many other contemporary fonts are based. The Cibolas made the perceptive connection that Helvetica might also function as the symbolic equivalent to the normative human body. By making slight modifications to Helvetica — extending the right side of the letter "M", cutting off the bottom of the letter "O", and shortening the top of the letter "T", for example — they subtly connected the beauty of typographic variation to the beauty of human variation.

STARING confronted the spectacle of disability directly by way of Rosemarie Garland-Thomson's critical rethinking of the act of staring, inverting our expectations, telling us it's okay to stare and that in this once forbidden act we could learn something new, something valuable. The first work visitors encountered in the galleries when visiting the exhibition was Doug Auld's painting Brian (Fig. 8), a painting we hung so that the piercing blue eyes of the burn survivor met the stare of the spectator. On the walls facing Brian were works of art depicting socially acceptable forms of staring: the gaze of the tourist at Mount Rushmore, the doctor as he probes a patient's body, or the scientist intently examining a microscopic specimen. This first room of STARING created the implicit question: why are some staring encounters considered acceptable, and others not? The remaining rooms of the exhibition were filled with paintings and photographs that invited staring encounters, openly playing on the concept of disability as spectacle, but as in Garland-Thomson's book, subverting it.

ANN: Works in both exhibitions revealed intriguing and promising strategies for calling attention to invisible disabilities and the interior spaces of the body. These strategies were complicated; for example, sometimes there was not a strict line between visible and invisible disability. What might seem a difficulty of representing interiority however was for us full of great possibilities for creativity, as what appears to be a limiting process is actually quite open. The works in our exhibitions explored pain, brain injury, and intellectual disability; they also explored how art can mediate against stereotype or the conventional representation of pain and mental difference in art. Doug Auld's painting Maria (Fig. 13), for example, represents a Latina woman who is lushly enfleshed, and who has scars on her face and arms from burns; she is sitting leaning forward on her folded arms, staring at us directly. She has long brown hair, polished nails, earrings, and delicate bra straps appearing out from underneath her tank top. Conversations with Auld revealed to us that Maria had a brain impairment from smoke inhalation; he expressed frustration at trying to capture that with a "flatness" in her eyes. But to us, her identity did not read in such a limited way, rather we saw her portrayed as having a strong sense of femininity, a fierce presence, and engagement with us as viewers.

Figure 13. Doug Auld, Maria, 2006, oil on linen, 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm). Collection of the artist

JESSICA: The process of incorporating universal design to create an accessible exhibition is a curatorial one. It is curatorial because access shapes the audience and therefore determines an exhibition's intention. We must ask ourselves who is important enough to include in the audience and how will we design an exhibition to realize that inclusion? For example, if we exclude large print, audio guides, or tactile pieces, then we exclude people with visual impairments. This is also curatorial because accessible exhibitions are a matter of choice. These choices are sometimes negotiated by financial constraints, but that assumes that all access costs money. Printing wall text in large font, hanging paintings a little lower, and leaving space between sculptures for wheelchair access does not cost money and resistance to creating a space like this usually emanates from aesthetic sensibilities and not financial ones. So what choices did we make with and without a budget for access? In the case of STARING where we had no money, we did just what I spoke of: used large print wall text, lowered the hanging height of works, and kept the floor open so that it was easy to navigate.

Figure 14. Harriet Sanderson, Molt, with Scurs, 2008, found mattress pads, chairs, shoes, ink, altered wood walking canes, and light. Collection of the artist

In the case of RE/FORMATIONS we had a larger budget and could include more accessibility features. The first step was to incorporate some of the artists into the process of accessibility. We commissioned new works for the exhibition from Laura Splan and Harriet Sanderson and asked that they think about making their works tactile. Harriet Sanderson's installation was completely tactile and moveable (Fig. 14). Visitors could pick up the cane pieces and the cane shoes to hold and also put somewhere else in the room. Every morning our gallery attendants would re-stage the room the way Sanderson originally installed it. Laura Splan's work is generally not tactile because she works with such delicate materials, however, for RE/FORMATIONS she invited the audience to touch her series of doilies that mimicked the viral structure of various diseases (Fig. 15). We also hired Joel Snyder to create an audio described tour of the exhibition, which was available to all gallery visitors and remains available for download on the RE/FORMATIONS website: www.davidson.edu/reformations.

Figure 15. Laura Splan, installation view of doilies, from left to right: HIV, Hepadna, SARS, Herpes, Influenza, 2004, freestanding computerized machine-embroidered lace mounted on velvet, 16.75 x 16.75 in. (42.5 x 42.5 cm) each (framed dimensions). Collection of the artist

Figure 16. Installation view of RE/FORMATIONS: Disability, Women, and Sculpture, Van Every Gallery, Davidson College, 2009

Because this was a sculpture exhibition the floor space had to be rethought, as did the height of the pedestals. These were cut down to no taller than thirty-six inches and spaced out so that people would be able to easily navigate between them. Wood strips were added around each pedestal to help orient visually impaired visitors who use canes (Fig. 16). The print materials we mailed out were all printed in large font and some included Braille inserts produced for us by the National Braille Press. For the opening night panel discussion we hired a sign language interpreter, made sure that all the panelists had microphones, and had a wheelchair accessible van available to transport anyone who needed a ride from the lecture hall to the gallery. Finally, our exhibition catalogue was made both physically and financially accessible as well as environmentally friendly because instead of printing a traditional paper catalogue, we created a website.

Access became part of the aesthetic experience of both exhibitions by allowing visitors, disabled and nondisabled, to look in new ways. When we installed the art at a lower height people of all statures commented on having a more intimate experience with it. Now, rather than the painting or sculpture being above and beyond the body, it was with the body. We also received numerous appreciative comments for the large font wall text because frankly, everyone has a hard time reading 14-point font from a distance. The access in RE/FORMATIONS also opened up new ways of viewing. People who used Joel Snyder's audio guide found that it enhanced the exhibition because it helped them to look closer and longer, to notice details they had missed, and that it led to a deeper reading of the works as visitors contemplated what the audio describer believed important enough to mention versus what they considered important. The conclusion is that accessibility features are not for and appreciated by people with disabilities alone, but the entire audience (although you don't need to justify the use of accessibility features on the basis that even non-disabled people can use them). Most important is the recognition that accessibility is not simply a function; accessibility is an aesthetic that enlivens and enriches the experiences of all people.

ANN: There were several curatorial and intellectual challenges and opportunities presented by our exhibits. In order to make each accessible in the way you want to do it, you have to have time and money, two of the most difficult things to get. As Jessica described just now, particularly for RE/FORMATIONS, we were able to implement several different kinds of accessibility features that invigorated the representation of the work. Some of those features directly challenged convention: for example, our wall text was not only bigger, we had more of it. Where some curators do not like a lot of wall text, seeing it as too instructive or taking away the freedom of the viewer, we pushed against this notion that the viewer was a neutral tabula rasa. We wanted to use that wall text to invite people to think from the very political perspective that informed our curatorial efforts. In the case of STARING, it was necessary to introduce them to the ideas of Rosemarie Garland-Thomson that were the underpinning of our exhibition through both the wall text and the art. This speaks to a larger curatorial challenge/opportunity with both exhibitions: a disability perspective is new for most people. So, you have to have context, or people will keep looking — or not looking — in the way they have been taught to view work depicting physical disability or ideas about normalcy. You can present these ideas in the best way you know how, and you will still get resistant viewers; I had several encounters with people in the gallery where STARING was on display where they remarked how sorry they felt for some of the figures, suggesting how deeply ingrained pity is as an initial response to disability in our society. But this puts the onus on museums and galleries, then, to foreground such challenges, resisting the drive toward ostensible neutrality so popular in curatorial convention that actually renders invisible ableist attitudes, and therefore caters to them. And after all,it is only through more self-conscious approaches to representation, grounded in genuinely collaborative practice with disabled people, that museums [and, we would add, galleries] can begin to tap their potential to contribute towards broader social changes. 12

Some of our curatorial features worked to underscore our exhibitions' efforts to create such social change. In STARING we had, for example, groupings of images of similar kinds, in order to create a kind of visual intertextuality among them. And so Chris Rush's soft image of a child with limb difference (he had no hands) was imagined separate from the typical medicalized or sentimentalized gaze in the context of other images of similar disability, including a Rembrandt drawing that hid such difference, and a Doug Auld painting in which an African-American burn survivor proudly displayed his; in such juxtaposition, there was an invitation to see these subjects' place in the full range of human embodiments differently.

Some of our best—and missed—opportunities came in interactions with the public. We originally were going to title the first exhibition DE/FORMATIONS as a way of deconstructing that pejorative word. But we got pushback from the parents of disabled children with whom we were speaking about coming to the exhibition, who, quite understandably, objected to bringing their children to an exhibition that identified disability as a deformation. While that was not our intent, it showed how this title resisted access; its intended meaning firmly ensconced in the realm of academic wordplay, it seemed to reinforce the idea that the exhibit would be a freak show of some kind. And in the end, listening to this challenge made our title and thinking so much better—what expectations and attitudes were we re/forming and re/shaping? This is a more forward looking notion, one emphasizing creation rather than recirculating the tired old idea that disability equals disfigurement.

We are still thinking about ways we could have pushed at the organizing ideas of each exhibition more deeply. What would it have meant, for example, to have more sculpture with which people could interact? That was not permanent? To have art in nontraditional spaces around campus other than the galleries and the college union? We also wish we had been more proactive in bringing in more disability organizations. We worked with LifeSpan, a local arts organization that makes art with community members with intellectual disabilities in a way that emphasizes their vision, not art therapy, and that was very successful. Members of that community toured the exhibitions, had their work shown in the campus union, and created some amazing work in response to what they saw when they visited Davidson. But while we contacted other organizations, their members did not come, and we think that rests on us. Never having done this before, we didn't think about alternative media, as well as going more out into the community to recruit audience members. The exhibitions were well attended, but there was not as strong a presence of the disability community. And while it is great that the exhibitions challenged the thinking and ideas of a typical Davidson art-going audience, we wish we had used the opportunity better to connect disabled and nondisabled community members from the greater Charlotte region.

In the end, however, the intimacy and interdisciplinarity of the liberal arts environment lends itself to developing exhibits of this kind. When Rosemarie Garland-Thomson visited the exhibitions, she said to me: "Now you're a curator." I am an English professor, and I was both encouraged and struck by this comment, and it reminded me that our small college setting was what had allowed me to envision and reinvent myself in this way. Jessica and I might never have encountered each other except for being at a small institution in which our paths could cross. Indeed, because disability studies is so interdisciplinary, exhibits featuring disability art and culture are ideally suited for the liberal arts context. In the space of the liberal arts college, the exhibitions became simultaneously point of arrival and place of further genesis. We had genetics classes and medical humanities classes visit our exhibitions in equal measure, facilitating conversations between the sciences and humanities in the gallery space. The aftereffects of the cross-disciplinary exchanges that took place within the exhibit are palpable; for example, I have twice now team-taught course with a with Davidson College Biology Professor Dr. David Wessner on representations of HIV/AIDS that grew directly out of his bringing students in his genetics seminar to see the exhibition, and our subsequent discussions about how we could use the arts to collaborate. (In fact, we are currently planning an exhibition of our own exploring the intersection of art and science slated for 2014). Indeed, there have been cross-institutional exchanges outside Davidson; we have been fortunate to work with our colleagues at Haverford College and share our experiences with them as they planned their own disability and art exhibition. While we realize not everyone reading this article has the setting of the small liberal arts college as a milieu within which to work, we encourage our audience to think about the ways in which they could seek out new kinds of collaboration within the context of their own organizational structures to make similar exhibitions happen.

We invited people to think about disability as an identity and an aesthetic, not simply a theme for an exhibition. We took theoretical and intellectual ideas and debates from within disability studies and translated them for a wider public. We invigorated our own art space as a place that could be challenged and reimagined through access. For both exhibitions, we reinvigorated our understanding of Davidson College permanent art collection by drawing on it for works to include that could be productively understood through locating the ways in which a disability aesthetic was made manifest in them. In the visibility of disability came for us and our community a space of excitement, invigoration, and access to an aesthetic unlike any we had considered on our campus until that point. What better role for an art gallery housed at an institution of higher learning?

Figure 17. Reconstructed installation view from STARING, Van Every Gallery, Davidson College, 2009. Left to right: Doug Auld, Jelani, 2005, oil on linen, 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm), collection of the artist; Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Jan Asselyn, Painter, ca. 1647, etching, 14 x 15 in. (35.56 x 38.1 cm), Davidson College Art Collection; Chris Rush, Paper Crown, 2001, conté crayon on paper, 19 x 14 in. (48.26 x 35.56 cm), collection of Steve Johnstone and Adam Geary; John Sandlin, Lt. W.W. Cooke, 1973, lithograph, 30 x 40 in. (76.2 x 101.6 cm) unframed, Davidson College Art Collection.

Works Cited

- "Davidson College - Statement of Purpose." Accessed January 12, 2013. http://www3.davidson.edu/cms/x924.xml.

- Ehrenreich, Barbara. "Welcome to Cancerland: A Mammogram Leads to a Cult of the Pink Kitsch." Harper's Magazine 303, no. 1818 (November 2001): 43-53.

- Itzkoff, Dave. "Video Deemed Offensive Pulled by Portrait Gallery." The New York Times, December 2, 2010, sec. C3.

- Lehrer, Riva. "Woman Made Gallery — Humans Being II." Accessed May 24, 2013. http://womanmade.org/show.html?type=group&gallery=humansbeing2013&pic=1.

- Lehrer, Riva, Sofia Zutautas, Chicago (Ill.). Dept. of Cultural Affairs, and Chicago Cultural Center. Humans Being: Disability in Contemporary Art. Chicago, IL: Chicago Cultural Center, 2006.

- Sandell, Richard, Jocelyn Dodd, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, eds. Re-Presenting Disability: Activism and Agency in the Museum. London; New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Siebers, Tobin. Disability Aesthetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010.

Endnotes

- We want to thank Kristin Lindgren and Debora Sherman, our hosts at Haverford College, and our co-presenters, Georgina Kleege, Katherine Sherwood, and Tobin Siebers for the intellectually invigorating exchanges of that symposium, meant as a prelude to the exhibition Haverford College hosted in fall 2012. We would also like to thank Brad Thomas and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson for their expertise, ideas, unfailing support, and encouragement as we created both exhibitions.

Return to Text - The exhibition catalog for RE/FORMATIONS: DISABILITY, WOMEN, AND SCULPTURE can be viewed at http://www.davidson.edu/reformations; the exhibition images for STARING can be viewed at http://www3.davidson.edu/cms/x39519.xml.

Return to Text - One recent example of this is the 2010 controversy over the exhibition "Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in Portraiture" at the National Portrait Gallery, in which David Wojnarowicz's four-minute video "A Fire in My Belly" was censored because of accusations that it was anti-Christian. Dave Itzkoff, "Video Deemed Offensive Pulled by Portrait Gallery," The New York Times, December 2, 2010, C3.

Return to Text - "Davidson College - Statement of Purpose," accessed January 12, 2013, http://www3.davidson.edu/cms/x924.xml.

Return to Text -

Richard Sandell, Jocelyn Dodd, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, eds., Re-Presenting Disability: Activism and Agency in the Museum (London; New York: Routledge, 2010), 93, 3.

Return to Text - We would like to thank Jay Everett for his advice and support as well as the sponsors for RE/FORMATIONS: The Mary Duke Biddle Foundation; The Ethel Louise Armstrong Foundation, Inc.; Wachovia Corporation (now Wells Fargo); Davidson College Friends of the Arts; Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, PLLC; Anonymous; LifeSpan Incorporated; The Arts & Science Council and the Grassroots Program of the North Carolina Arts Council (a state agency); The National Endowment for the Arts; North Carolina Arts Council with funding from the state of North Carolina and the National Endowment for the Arts, which believes that a great nation deserves great art; Davidson College The Public Lectures Committee; Davidson College German Department; Davidson College Gender Studies Concentration; Davidson College English Department; Davidson College Medical Humanities; Davidson College Dean of Students Office.

Return to Text - Tobin Siebers, Disability Aesthetics (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 139.

Return to Text - Riva Lehrer et al., Humans Being: Disability in Contemporary Art. (Chicago, IL: Chicago Cultural Center, 2006).

Return to Text - Riva Lehrer, "Woman Made Gallery - Humans Being II," accessed May 24, 2013, http://womanmade.org/show.html?type=group&gallery=humansbeing2013&pic=1.

Return to Text - Other disability exhibitions have happened more recently than ours which should be noted for how they, too, have modeled innovative ways for representing disability and art, including Medusa's Mirror: Fears, Spells, and Other Transfixed Positions (Pro Arts Gallery, September 13, 2011 - October20, 2011); Yelling Clinic: Art, War & Disability (Berkeley Art Center, April 14, 2012 - June 3, 2012); What Can a Body Do? (Haverford College, Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, October 26 - December 16, 2012).

Return to Text - Barbara Ehrenreich, "Welcome to Cancerland: A Mammogram Leads to a Cult of the Pink Kitsch," Harper's Magazine 303, no. 1818 (November 2001): 43 - 53.

Return to Text - Sandell, Dodd, and Garland-Thomson, Re-presenting Disability, 110.

Return to Text