Disability arts in the United Kingdom and disability culture in the United States play important roles in expressing a positive disability identity. This paper reports on expressions about identity, in both artwork and reflective words, of 47 young artists with disabilities who were finalists in the VSA arts / Volkswagen arts competition between 2002 and 2005. As part of an evaluation of this program, we reviewed the artists' application essays and artwork. In doing so, we found a wealth of information on their perceptions of what it means to be a person with a disability and an artist, and how these two identities intersect. The findings provide insights into the role of the arts in identity formation for young people with disabilities, and point to the potential for future research on how arts and disability interact.

Introduction

Over the past 30 years, there has been a considerable evolution in the ways that disability is conceptualized as a social phenomenon. The social model of disability, which first emerged in the 1980s, introduced the idea that disability is socially created rather than being rooted in the individual (Hahn, 1993; Oliver, 2000). The idea that disability was created by social oppressive elements rather than by individuals' impairments was revolutionary and empowering to people with disabilities.

More recently, new models have emerged that seek to more fully encompass individuals' experience of impairment (Crow, 1996; Hughes and Patterson, 1997; Swain and French, 2000). For example, Hughes and Patterson (1997), in calling for a sociology of impairment, argue for an expansion of the social model, and propose "an embodied, rather than a disembodied, notion of disability" (p. 326).

Disability and Identity

With this emerging focus on individual experience comes an emphasis on disability identity as central to disability theory. Siebers (2008) states that "to call disability an identity is to recognize that it is not a biological or natural property but an elastic social category both subject to social control and capable of effecting social change" (p. 4).

Identity is also central to the affirmative model of disability proposed by Swain and French (2000). Rather than situating the "problem" of disability in impaired bodies (as in the medical model of disability) or a disabling society (as in the social model of disability), the affirmative model "encompasses positive social identities, both individual and collective, for disabled people grounded in the benefits of life style and life experiences of being impaired and disabled" (Swain and French, 2000, p. 569).

In a similar vein, Gill (1997) describes a process of disability-identity formation that involves a progression from "coming to feel we belong" (assertion of the right to inclusion in society) to "coming out" (developing a proud disability identity).

Darling (2003), however, argues that while some people with disabilities have adopted disability pride or the affirmation model, others "continue to accept the older views and regard themselves as victims of personal misfortune" (p. 884). She proposes a typology of disability identity encompassing seven types:

- Normalization (acceptance and achievement of the norms of the larger society, with or without acceptance of disability stigma)

- Crusadership (involvement in a disability subculture in an attempt to achieve normalization)

- Affirmation (involvement in a disability subculture and viewing disability as a primary identity and source of pride; "coming out")

- Situational Identification (adopting multiple identities in different situations, e.g., normalization when with those without disabilities but affirmation when with others with disabilities)

- Resignation (unable to achieve normalization but lacking resources to access the disability subculture)

- Apathy (completely uninformed)

- Isolated Affirmation (affirmation orientation arrived at without exposure to disability subculture)

Darling (2003) goes on to describe a process of identity "careers" involving movement from one identity to another, emphasizing the importance of societal context for such movement. For example, if a person with a disability succeeds in gaining the access he/she seeks through crusadership, that person may cease being a crusader and shift to a normalization identity. Another example is that exposure to the disability community can lead to a change from another type, such as resignation or normalization, to affirmation.

The Role of Disability Arts

The arts can play an important role in the progression of the disability identity over time, or the identity "career" (Darling, 2003). Swain and French (2000) describe the importance of the UK disability arts movement in developing and expressing a positive group identity for people with disabilities:

Through song lyrics, poetry, writing drama and so on, disabled people have celebrated difference and rejected the ideology of normality in which disabled people are devalued as 'abnormal.' They are creating images of strength and pride, the antithesis of dependency and helplessness. (pp. 577-578)

Similarly, in the United States, Gill (1995) notes that

"disability culture" has become a popular term among our people whether activist or not, young or old, scholarly or undereducated. I detected an underlying assertion in this embrace of the term that goes something like, Yes, we have learned something important about life from being disabled that makes us unique yet affirms our common humanity. We refuse any longer to hide our differences. Rather, we will explore, develop and celebrate our distinctness and offer its lessons to the world."

Likewise, Walker (1998) describes the importance of the arts in disability culture:

Disability Culture is made up of artists who are not trying to pass, artists who don't buy into societies [sic] rule that we should be ashamed of our disabilities, artists who often show in their art a self-acceptance and a pride about who they are, not in spite of a disability, not because of a disability, but including a disability.

Research on artists has further explicated the positive role of the arts with respect to disability identity and culture. Evaluations of arts-based instruction, for example, have found that arts-based teaching and learning (among other things) enhanced self-esteem and built self-confidence on an individual level for artists (Rooney, 2004) including those with disabilities (Mason, Thormann, and Steedly, 2004; Mason, Steedly, and Thormann, 2005).

Taylor (2005) explored the role that visual-arts education plays in the transition experience of college students with disabilities from school to work or to higher education. Stating that "identity dilemma is at the heart of the transition that all adolescents and young people experience" (p. 764), Taylor highlighted the importance of the arts in helping young people come to terms with typical transition issues (e.g., parental relationships, social class, and maturational issues).

Perhaps more importantly, Taylor found that engaging with the arts could also help with issues of disability and impairment that affect transition and the identity-forming process. Specifically, Taylor found that arts education helped these youth "to engage in a process of self-realization" in which they identify and address "negative and oppressive perceptions of disability via their artwork" (p. 763). As a result, the young artists adopted a more "positive, inclusive and potentially multi-identity perspective" (p. 763).

The VSA arts / Volkswagen Program

This paper reports on expressions about identity, in both artwork and reflective words, of 47 young artists with disabilities. These 47 artists were finalists in the VSA arts/Volkswagen of America, Inc. (Volkswagen) Program for program years 2002-2005.

VSA arts is an international nonprofit organization, established in 1974, that develops programs to increase access to the arts and educational inclusion with and for individuals with disabilities. The primary goal of the organization is to create opportunities and events that allow artists of all ages to share their voice and message through the arts. Locally and internationally, VSA arts provides educators, parents, family members, and artists with the resources and tools they need to support literacy, school readiness, career development, and arts programming in different school systems and communities. In particular, the program creates opportunities for artists in the United States and in other areas of the world to showcase their work by promoting increased access to the mainstream arts community.

In 2002, VSA arts and Volkswagen of America, Inc. partnered to create the yearly juried VSA arts/Volkswagen competition for young visual artists with disabilities. The overarching goal of the competition has been to recognize and encourage young artists with disabilities at an important time in their lives. The program is intended to boost the participants' professional development so that more people with disabilities will enter art professions.

The program targets artists ages 16 to 25 for two reasons. First, this is a critical time period during which young people are making the transition from school to college and/or careers, so providing both recognition and financial awards is seen as a way to help them choose a career path in the arts at this juncture. Second, most previously existing VSA arts programs were focused on either adults or younger children, with few opportunities for teenagers or youth. The exclusive focus on artists with disabilities is intended to address the general under-representation of people with disabilities in the arts.

Each year the program selects a theme that reflects its corporate sponsorship. It then uses the theme to announce the arts competition and to invite applications from visual artists with disabilities. Artists are requested to submit up to five pieces of artwork and a personal statement that includes a brief description of each piece of artwork. Applicants are also encouraged to submit artwork that reflects the program theme for that year.

The winning artists are chosen each year by a panel of distinguished jurors. Program finalists are awarded cash awards of between $2,000 and $20,000; attend a reception on Capitol Hill; and are included in an art exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution and an exhibit that travels across the country for two years.

The authors were contracted by VSA arts in 2005 to conduct an evaluation of the program to determine its impact on the finalists' personal and professional development. The overall findings of the evaluation are reported in a previous article (Boeltzig, Sulewski, and Hasnain, 2009). The present article relies on the same data but examines those data through a different lens, focusing on the young artists' sense of and development of their identities both as artists and as people with disabilities.

Methods

The purpose of the original evaluation was to determine the VSA arts/Volkswagen program's impact on the program finalists' personal and professional lives, and to recommend program improvements. Three research questions guided this evaluation:

- What impact did the VSA arts/Volkswagen program have on finalists' personal development?

- What impact did the VSA arts/Volkswagen program have on finalists' educational, work, and artistic pathways?

- What are the implications of the evaluation findings, and what recommendations can be made to further improve the program?

Research staff used a multi-method design to conduct the evaluation. This included a review of relevant source material and documents (described in further detail below), a survey of program finalists who won awards between 2002 and 2005, and in-depth case studies of five of those finalists.

While the original intent of the study was to evaluate the program, some interesting findings emerged from the review of the participants' application materials regarding how they formed identities both as people with disabilities and as artists. The present paper explores those emerging themes in greater detail than our previous publication. Since the paper is focused only on findings from the source-material review, this method section addresses only that component of the data collection.

Description of the Data

Between 2002 and 2005, the program gave awards to 47 emerging artists. We reviewed the application information for each of the 47 finalists, which was provided to us by VSA arts. Each application packet included:

- a competition entry form including (a) contact information, (b) date of birth, (c) disability type, (d) prior involvement with VSA arts, (e) academic background, and (f) the name of an art teacher or instructor instrumental to the artist's artistic development;

- a 400-word artist statement describing (a) the artist's motivation to begin creating artwork, (b) techniques and media used, (c) the relationship between the artist's disability and his/her art, and (d) the role of art in the artist's education;

- a personal statement reflecting on how the artist's artwork related to that year's theme;

- images of up to five pieces of artwork; and

- a written description of each piece of artwork and how it related to the theme.

The 47 finalists had diverse disabilities including physical disabilities, learning disabilities, sensory disabilities, mental illnesses, and chronic illnesses. They came from 26 states across the country, were evenly split by gender (24 women and 23 men), and had an average age of 21. Most finalists had been making art since they were young children. At the time they applied for the competition, more than half of the young artists (at least 28) were attending or had completed college or university; almost all were pursuing a degree in the arts. Finalists were pursuing their studies in a range of fields including painting and drawing, photography, graphic arts, and digital imaging. Before they applied for the VSA arts/Volkswagen program, many had gained some experience in the arts (apart from the academic study of art), although only a few finalists (three or four) were working as artists or in an arts profession.

Data Analysis

The textual and visual data were imported into ATLAS.ti Version 5.2 for PC, a qualitative data-analysis software package, in preparation for analysis. To analyze the data, we used two techniques: coding (attaching meaningful labels that denote concepts, actions, or recurrent themes to data or pieces of data) and memo-writing (systematically writing about the data during the coding process), as described by Miles and Huberman (1994). The research team developed operational definitions or codes for each theme, as those themes emerged, so that we could share meanings of the codes as a team. These definitions described the codes as the themes emerged. Memo-writing further helped to organize themes from the data. These themes were further developed as the research staff interpreted and analyzed the results (Creswell, 1998).

The research team met on a regular basis, first to reconcile codes and then to discuss the emerging categories and themes. We simultaneously coded and analyzed the data, continually compared specific incidents, refined our concepts, and explored the relationships between various themes, as recommended by Charmaz (2000). We also discussed findings with colleagues, inviting their alternative explanations. Drafts of the findings were compiled using the themes organized during the memo-writing process. In this way, the memos served as an outline for the results that are presented in this paper.

Findings

This section presents our findings about the participating young artists' sense of identity, both as artists and as people with disabilities. The fact that these young people entered an arts competition for people with disabilities indicates that each of them identified to at least some extent as both an artist and a person with a disability. Our examination of their application materials provided more detailed information on how they developed those identities and how the two identities — disability identity and artist identity — intersected (or not) for these young artists.

First we describe various participants' experiences of identity formation as artists and factors influencing their identification as an artist. We then explore finalists' descriptions of their identities as people with disabilities. Finally, we examine the intersection of art and disability in finalists' lives, including how finalists described this dual identity, how disability affected their art-making and vice versa, and how they expressed their experiences of impairment and disability in their art.

Artist Identity

Exposure to art and art-making, and the circumstances and people that connected finalists with the arts, played an important role in these young people becoming artists. Many of them (35 in total) had been making art since early childhood. Although their pathways varied, we discovered a few common themes in the way they discovered art in their early years.

The role and influence of family. About a third of the young finalists came from families where at least one member was an artist (e.g., a painter, a photographer, a musician). One finalist wrote: "I have always been involved with art. My uncle and my grandfather are professional artists and have taught me a lot throughout my life."

Parents who were artists often exposed their children to art from an early age. Two of the finalists whose mothers were art teachers said that art materials were always around and that it was inevitable for them to explore the arts. Several finalists became interested in the arts by observing those family members. One finalist wrote in her application essay, "Drawing was always something I did just for the fun of it. My older sister is an artist and I always admired her work, but I never thought I could be as good as her and I never had serious thoughts about becoming an artist until recently."

Families often encouraged finalists to pursue the arts beyond high school. For example, one finalist wrote, "My family always has positive and encouraging things to say about my work." Likewise, a finalist who was home-schooled believed that the whole process of home schooling and the artistic talents of her parents and sister were essential to her growth as a painter.

Finalists' mothers often served as mentors. For example, one finalist wrote, "My mother has been the greatest source of motivation. For 20 years, she has encouraged my pursuits and served as a tireless teacher. Her dedication to helping me live with diabetes and her uncompromising faith that I will be able to accomplish anything (artistic or otherwise) in spite of its challenges is most amazing."

A few finalists wrote that their fathers played a significant role in their pursuit of the arts. For example, one wrote, "I am blessed to have innate talent for art, apparently inherited from my father, who always nurtured and supported my family. One of the earliest pieces is a self-portrait I did with my father at age five which still hangs in our den."

The role and influence of educators and other (art) professionals. More than half of the finalists (27 in total) wrote about the role that teachers played in recognizing their artistic talents and helping channel these talents in an artistic way and/or in a pedagogical way. One finalist, for example, had started creating artwork at age five, motivated by his kindergarten special-education teacher. Many teachers recognized the potential of art in helping students, especially those with learning disabilities, overcome barriers to academic achievement.

Five finalists said art professionals (such as painters, illustrators, or curators) were involved in their lives and uncovered their emerging artistic talent. One shared her experiences of being diagnosed with a visual impairment while in college. Her mentor relationship with another artist who also had a visual impairment helped her overcome her fears of no longer being able to draw and paint. Another artist described how various local painters had mentored her.

Other circumstances and life situations. The finalists also shared a variety of environmental influences that helped them cultivate their artistic skills and talent. A few (three) were inspired by famous artists, which influenced the way they approached their own art. One finalist, known for his creativity and imagination in creating his own characters and situations, credited his many hours watching cartoons.

For two artists, one whose parents were immigrants and the other one who was born outside of the United States, the immigrant experience had a strong impact. One of them described her journey in the arts despite her parents' strong resistance to her choosing the arts as a profession. Traveling to different parts of the country or abroad influenced two other young artists to share their experience using art. Gaining practical experiences in the arts (through internships, college jobs, or part-time work) and public exposure of the artists and the artwork (through art exhibitions, competitions, awards, publications) also seemed to have helped finalists progress in their development as emerging artists.

Meanings and purposes of art and art-making. Almost all of the finalists commented on the importance and purposes of art in their lives. A number of them used broad statements such as, "Art is a large part of my life," or, "The arts define who I am," while others were more specific. One wrote, "Art gives me a reason to live. It is an outlet for me to feel good about myself and do something well. It has given me purpose and guidance throughout my life involving education, socialization, and dealing with life's challenges." Another said that photography was "an essential part of me," and still another wrote, "Art was the driving force and the reason to further my education." Others noted specific benefits of their arts involvement related to everything from their academic success to their self-confidence to their financial well-being.

Many finalists were drawn to the arts and art-making by the desire to learn and to pursue arts education. For example, one wrote, "I was motivated most by my very first oil painting class and also from being introduced to the history of art." Academically, finalists said they benefited from arts education in a variety of other ways. These included enhanced reading, writing, and math skills, improved critical and creative thinking, and increased commitment to learning and heightened understanding of worldviews and issues. Others had never thought of art as part of their formal education. As one wrote, "It has always been my favorite thing to do, and my future career, not a subject in school."

Another essential factor for many of these young artists was the ability to develop strong connections with varied audiences. One finalist wrote, "Ever since I was little, I have learned to communicate how I feel by the act of creating. I felt safe to explore and to be who I am, by being able to work on a piece of art without ever feeling like I was doing or saying something wrong." For another artist, art was a way of giving to his community: "My skill allows me to continuously give back to my community — the most rewarding aspect of art." In general, finalists were able to connect with schools and colleges, but also with the arts and disability communities: "Art helps me to get to know people better and make a lot of new friends."

Emerging as a young artist meant different things to the finalists. Some became more cognizant of their artistic talent and skill; others became more aware of their disability and incorporated the body, impairment, and disability more thematically into their artwork. Still others experimented with various art media and techniques. However, almost all of these emerging young artists were dealing in some way with figuring out how to incorporate art into their lives and what role art is supposed to play and should play — a hobby, academic study, and/or a profession.

Disability Identity

Being an artist with a disability was an important part of most finalists' identity. Most of them talked about their impairments and disabilities in their application essays (36 finalists) and the descriptions of their artwork (nine finalists). Several described what it was like for them to live with their impairment. In addition, some described the process of taking on a disability identity, whether through becoming more accepting of a disability they had always had or through acquiring a disability and/or impairment.

Living with impairment. Describing the effect of impairment on her life, one finalist said that a combination of two genetic disorders has "drastically affected my life and caused my disability." An artist with a physical disability described learning to

…separate the disability of my body from the ability of my mind. I prefer to live in the mind, to understand the reality of my world from the inside out…I feel that my physical impairment has attuned my senses not toward what can be physically felt, but instead to what can be intuitively understood.

Finalists with learning disabilities (one of the most common disability types among finalists) particularly noted the challenges their impairments posed in their education. For example, one artist described how having a learning disability affected him in his school years:

During my childhood, it became evident through testing and obvious problems in the classroom that I had short-term memory loss, dyslexia, and processing difficulties. Later in my schooling, especially through high school, the academics became much more laborious.

Another expressed the frustration of living with a learning disability that was not diagnosed until after high school:

I study for hours, I sacrifice my time playing with friends in my childhood just to try to get a passing C-. I never did get that C-. I could never figure out why I could study days for a test and still turn out getting a F. Frustrating as this would be after going through my inter school years with a disability that I didn't even know that I had. Many are not aware of this problem, and I was one of them. To this day I still suffer from a bad low comprehension level and I can't read small books.

Claiming disability identity. Several artists described a process of claiming their identity as people with disabilities and learning to take pride in that identity. One artist wrote, "My disability is a burden I wear with pride." Another said that her disability/impairment is something "I live with… as I do all else that defines me as me: gender, appearance, likes/dislikes, intellect, sexuality, talent and so on." She went on to describe a stage in her life when she took control of her disability experience and stopped being dependent on others:

I abandoned the wheelchair. Got myself a cane and some New Balance [sneakers]. Though I had to depart for classes a lot earlier than those days of being pushed I made the way on my own. My course was not dictated by the whims or wants of others. I abandoned the role of pretty girl in the wheelchair… My body slowly became my own.

An artist with a developmental disability stated that she is "still trying to discover more about who I am and what [my disability] means for me."

A few artists described the somewhat different experience of taking on a disability identity after acquiring an impairment in the teenage or young-adult years. One artist with a visual impairment wrote, "After being diagnosed with histoplasmosis, I felt as though my doors were being closed to the world. However, I've always been told, when one door closes, another door opens." Another finalist talked of the effects of lupus and avascular necrosis on her life as a young adult:

Because of avascular necrosis, which gave me unbearable pain in my hips and below, I would limp some days and be unable to walk others. I had to undergo a total hip replacement. Lupus has affected me in many ways, especially with the chronic fatigue that inhibits me from doing much in one day. I had to learn how to let many of my artistic visions go. But after the hip replacement, I was able to attend school again and take my time to achieve my BFA [Bachelor of Fine Arts degree].

Whether through the acquisition of an impairment or through taking on a disability identity, these young people were incorporating disability and their experiences of living with an impairment into their identities. At the same time they were coming to identify themselves more as artists. The next section addresses the intersection of those two identities and how each affected the other.

Intersecting Identities

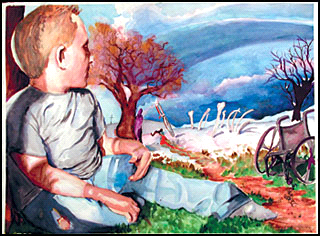

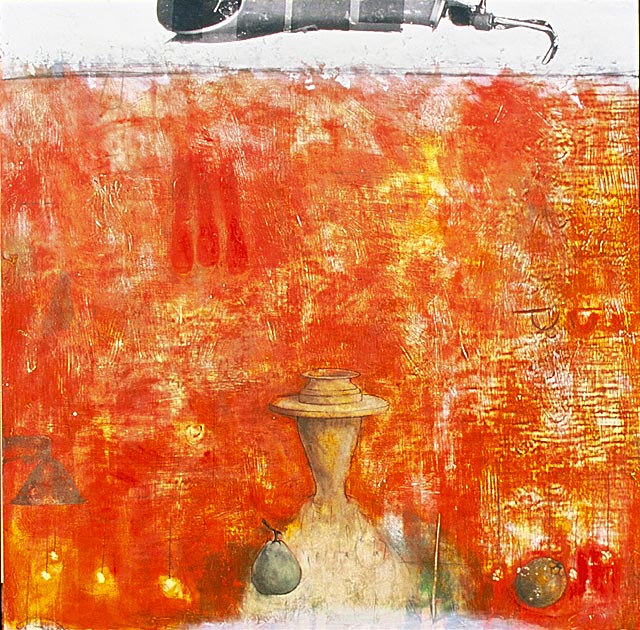

Artwork as a way of claiming disability identity. For a couple of artists, making art played a role in their taking on a disability identity. For example, one artist's self portrait reflected on his journey or "road trip" as a person with a disability. He wrote, "This piece [see Figure 1] I believe it is a road trip through my past. Going through my past helps to figure out who I have become." Another finalist found that his art helped him talk more openly about his disability: "I have never worn my prosthetic. Very few people know that I own one. After seeing the image occur in a body of work, people now confront me with questions. This allows my disability to come into more conversations" [Figure 2].

Identifying as an artist first. A few (three) artists emphasized the primacy of their artist identity over their disability identity. In an extension of the "people first" language espoused by many people with disabilities in the United States, these young artists considered themselves "artists first" and people with disabilities second. For example, one young man wrote, "I like people seeing me more as an artist and less as a person with a disability." Another finalist said that participating in an earlier VSA arts/Volkswagen competition "helped me to shift into a new mind set and past the self title I had in my mind, of the 'one handed artist.' Now, confidently I am 'an artist that just happens to be one handed.'" Reflecting a similar sentiment, an artist with a visual impairment wrote, "I really don't look at myself as having a disability. Artistically speaking, it hasn't hindered me in anyway."

Art and disability as mutually beneficial. Nine finalists described disability as a factor in choosing to be an artist and/or as an asset to their artwork. For several artists with mobility or fatigue issues, art provided a substitute for other pursuits. For example, one chose the art profession because after the onset of her disability she could no longer work a 45-hour-per-week job. Teaching art accommodated her needs and interests. Others said that from childhood they compensated for their inability to participate in physical activities such as sports or outdoor play by pursuing art. One finalist wrote, "I was never good at sports; my disability made it difficult. Instead, I developed and proceeded to explore the other areas that were open to me [such as music, writing, and art]." Another said that art "almost completely replaces the fact that I can't walk." A third artist wrote, "I do not dance and I do not run - when I'm driven to express all that is within I pick up a brush and this girl's life force pours out."

Several finalists with learning disabilities or mental illness felt that although these disabilities were barriers in other areas (such as academics) they actually enhanced their artistic ability. One young man with dyslexia and learning disabilities used his "strengths in perceptual organization, and began to incorporate his talent with 'mirroring imaging' into his artwork by including images that weren't usually noted by viewers unless the work was turned upside down." Another finalist said attention deficit disorder enhanced his creativity and Asperger's syndrome drove him to communicate through art. A finalist with obsessive compulsive disorder felt that her "obsessive nature was also my driving force for creating one of my favorite pieces. This made me realize that anxiety can be a positive driving force as well as a negative."

Art as a way of coping with negative aspects of disability. A number of finalists (21 in total) said that art helped them deal with depression, anxiety, fear, pain, and/or stigma associated with their disabilities. An artist who had had cancer used art to manage her fears about death. An artist with a physical disability used art to openly address his fears and discomfort about his disability. An artist with mental illness found art to be the only effective way of escaping her symptoms for a while. She wrote,

Painting is an escape from living with my disabilities. It is the physical release from the bi-polar disorder, allowing my emotions to drain on canvas. It is the mental exercise for multiple sclerosis, making me continually think. I feel a drive to create, to overcome the disability.

Another wrote,

Since I was very young I have found refuge in artistic expression. When I couldn't play like other kids and was terrified by certain situations and places, I could connect with the world through drawings and pictures. When I was hospitalized I drew pictures about my pain. When I felt isolated from others, I painted my loneliness and fear. My art has become my best friend and my sanctuary.

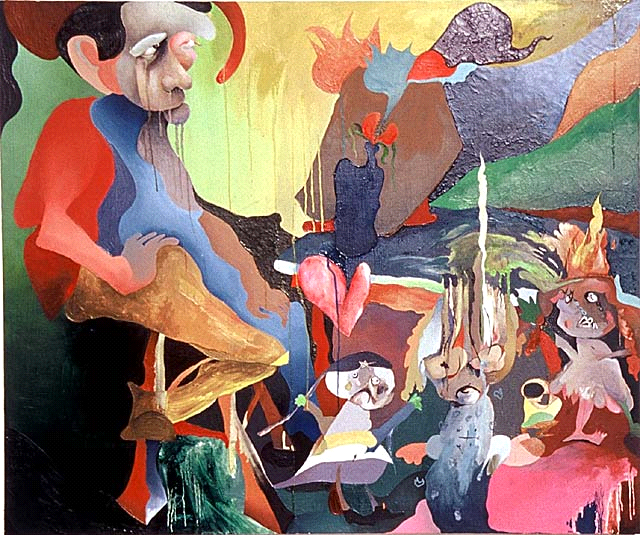

Two artists talked of using art as a way to express their experience of pain by drawing pictures of their pain while in the hospital. For example, one of them (see Figure 3) used distorted and fragmented figures to illustrate the experience of living with pain.

Finally, making art and being an artist often provided an escape from disability-related stigma and its effects on the young people's self-confidence. For several artists with learning disabilities, art provided an opportunity to excel when other school pursuits were challenging, and thereby to gain confidence and a sense of accomplishment. One finalist wrote,

Dealing with a learning disability all my life I have always been cast lower than others, pitied, or done worse than my peers. But in art, I can compete on an equal playing field and excel past those who can read better or faster or even spell all their words correctly. Having success with art gives me confidence that I am just as good as the others. It helps me realize I just have other areas of expertise.

Another artist wrote,

While having dyslexia and a learning disability in reading sets me behind others, my obsession for drawing puts me in front of everyone else at the same time…As my school years progressed my artistic abilities overshadowed my disabilities. My teachers and other students associated me with art. I was the kid who could draw and I earned top awards on the work I created. Teachers would ask me to design special projects and my classmates would ask me to create drawings for them. I was recognized for what I was able to contribute rather than what I was lacking.

This role of art in boosting confidence and managing stigma was also apparent with artists with physical and sensory disabilities. An artist with a visual disability expressed a similar sentiment to those quoted above:

I find that I have more confidence in areas throughout life because of the competence I have gained in art. Feeling accomplished in visual art has helped me live my life, work and enjoy it like everybody else without worrying too much about my disability.

A few artists with obvious impairments spoke of how art enabled them to show what was on the inside and get past the initial impression of inability that others took from their appearance. For example, one young woman wrote,

I want to show off my photography to everyone because I want them to see the real me, not what they see at first. Looks can be deceiving, and it seems my looks deceive everyone into thinking that I can't do anything.

Art as a way of communicating about disability. Several finalists described their artwork as either literally or figuratively depicting their disability or impairment and how they felt about it. For these artists, creating such artwork was a way of processing or understanding the role of disability in their identity.

The artists used disability in their artwork in a range of ways. Not all of them conveyed a message of disability identity; many preferred to leave it up to the viewer to identify a message in the artwork. The messages varied as much as the artists, but some artwork portrayed disability in more literal ways while other pieces portrayed it more symbolically. Symbolic representations of disability were particularly prevalent with nine artists describing their artwork as representing disability in this way. For example, one finalist created an art in which a bird in a cage reflected his culture, which tends to protect people with disabilities rather than to empower them. In another part of the same work he shows the bird flying free, no longer caged; for him this symbolizes being in America and having a new perception of disability that he depicts through his art.

Six artists incorporated literal depictions of their or others' disability in their art. As an example, one finalist created a literal depiction of her experiences with having lupus and undergoing a hip replacement at age 23 [Figure 4]. In her application essay, she wrote, "For six months straight I sat down at a coffeehouse with my pen and ink and worked on a 56-page graphic novel called 'Morning Star' that best expressed my journey so far with lupus."

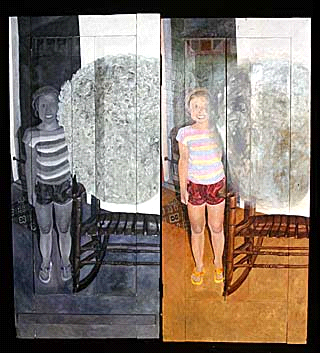

Some finalists intentionally focused their art on aspects of their body, illness, and disability to get a reaction from the viewer as a way to raise peoples' awareness about these issues. Seven submitted self-portraits that depicted impairment or disability in some way. For example, one finalist depicted herself mixing and pulling medication into a syringe. Another finalist used his self-portrait to represent his struggles with short-term memory loss, dyslexia, and processing difficulties. Another shared a self-portrait with a literal depiction of disability. In a diptych of painted self-portraits, she stands in front of a door. She wrote that she felt as though the doors to the world were being closed when she received her diagnosis. In her submitted artwork a large circle is smeared in the middle of the portrait to represent how she sees with her left eye (Figure 5): "Doctors know what histoplasmosis looks like from behind a scope, looking from outside in, but from my view, it's [a] completely different view from the inside looking out."

Another finalist shared her extreme desire to talk about her illness through images. Diagnosed with Hodgkin's disease, she created a symbolic image of herself as a movie star. Still another was interested in creating a symbolic "normal" image of herself as another person might see her. She feared losing her sight to diabetes, but her two self-portraits dealt with the tension and consequences of appearing unaffected by disease and the fear of no longer being able to see the beauty of places. "Much of my art deals with the challenges of my ambivalence toward being perceived as healthy in spite of having a hidden disability," she wrote in her application essay.

Another artist clearly depicted her impairment in a self-portrait titled "Interstitial Cystitis": the image represented her experience of a painful and incurable bladder disease. The finalist wrote, "Most of the time my bladder feels completely raw (symbolized by the blood) or feels as if there are shards of broken glass inside… and never feels empty."

Other artists' messages were concerned with the beauty of nature, human life and existence, and human frailty, and of "turning a negative into a positive, turning an illness into a beautiful art piece." One wrote, "The artwork is symbolic and literal in that a prosthetic interacts on the surface with other images of nature (leaves, flowers, hands) in this illustration of imperfections."

Discussion

The applications of the 47 VSA Arts/Volkswagen competition finalists provide interesting insights into the role of the arts in the evolving identities of young artists with disabilities. These evolving identities often reflected Darling's (2003) concept of identity careers in which people with disabilities move among the seven types of disability identity (normalization, crusadership, affirmation, situational Identification, resignation, apathy, and isolated affirmation).

For some artists, art helped them move toward more of a normalization identity. For example, some artists with learning disabilities described using art as a way of fitting in or demonstrating their value despite difficulties with other aspects of school, indicating that art helped them achieve normalization. Those who described themselves as "artists first," indicating that disability was a part of, but not the defining aspect of, their identities, also demonstrated a normalization identity. Still others used art to facilitate normalization by coping with the negative aspects of disability, such as pain and stigma. For the most part, these individuals seemed to fit into the category of those who "define themselves in normalized terms [but] do not accept the stigmatized image of disability that typically accompanies this perspective" (Darling, 2003, p. 886).

For other young artists, their own art-making and/or exposure to the world of disability arts and culture helped them move more toward an affirmation identity. Some artists used their artwork to illustrate their disability or to communicate a message about disability. Others used characteristics of their disability as artistic strengths.

In general, the arts seemed to help these young people move toward more positive types of disability identities. Their experiences reflects Walker's (1998) description of disability culture as "made up of artists … who often show in their art a self-acceptance and a pride about who they are." Moreover, a number of them are, as Swain and French (2000) said of the Disability Arts movement, "creating images of strength and pride, the antithesis of dependency and helplessness" (p. 578).

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

These findings are, however, only preliminary. Since this paper is based on secondary analysis of data collected to serve a different purpose (judging in an arts competition, rather than research on identity formation), there are multiple limitations to the findings.

First, the sample studied was not selected to be representative of the population of artists with disabilities. As such, the findings are generalizable only to the specific population studied (finalists in the VSA arts/Volkswagen competition) and not to the larger population of all artists with disabilities.

Second, the artists' application essays were intended to serve the purpose of selecting the competition winners, not specifically to learn about identity and identity formation. Therefore, the topics of identity and identity formation do not appear uniformly across all finalists. Several of the themes related to identity only showed up in a few artists' statements; we still consider those themes important as emerging concepts. The emergence of these ideas, unprompted, among even a few artists points to a need for more research to more deliberately explore those ideas.

Third, the data on which this manuscript is based are now close to six years old. The issues covered in this paper (identity formation and the intersection of disability and the arts), however, are enduring enough, and the words of the young artists quoted herein compelling enough, that it still seems worthwhile to share these findings.

These weaknesses point to a need for further research to examine the intersecting identities of artists with disabilities. Such research would contribute to disability culture and society more broadly by raising awareness of the role of the arts in the evolution of the identities of people with disabilities. Such research would also help to further develop the theoretical concept of identity by highlighting the complexities of identity development that cut across art, disability, and impairment.

The authors would like to thank VSA arts for the grant that made this research possible. The development of this manuscript was in part funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), US Department of Education (Grants # H133P060003 and H133A040007).

References

- Boeltzig, H., Sulewski, J. S., and Hasnain, R. (2009). Career development among young disabled artists. Disability & Society, 24(6), 753-769.

- Crow, L. (1996). Including all of our lives: Renewing the social model of disability. In C. Barnes and G. Mercer (Eds.), Exploring the divide, 55-72. Leeds, United Kingdom: The Disability Press.

- Darling, R. B. (2003). Toward a model of changing disability identities: A proposed typology and research agenda. Disability and Society, 18(7), 881-895.

- Gill, C. J. (1995). A psychological view of disability culture. Disability Studies Quarterly, 15(4), 16-19.

- Gill, C. J. (1997). Four types of integration in disability identity development. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 9, 39-46.

- Gill, C. J. (1998). Developmental obstacles to careers in the arts for young persons with disabilities. Concept paper presented at the National Forum on Careers in the Arts for People with Disabilities, which took place June 14-16, 1998 at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC.

- Hahn, H. (1993). The political implications of disability definitions and data. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 4(2), 42-55.

- Hughes, B. and Paterson, K. (1997). The social model of disability and the disappearing body: Towards a sociology of impairment. Disability & Society, 12(3), 325-340.

- Mason, C. Y., Thormann, M. S., and Steedly, K. M. (2004). How students with disabilities learn in and through the arts: An investigation of educator perceptions. Washington, DC: VSA arts.

- Mason, C. Y., Steedly, K. M., and Thormann, M. S. (2005). Arts integration: How do the arts impact social, cognitive, and academic skills. Washington, DC: VSA arts.

- Miles, M. B. and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Oliver, M. (2000). The politics of disablement: A sociological approach. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Raynor, O. and Hayward, K. (2004). 2003 statewide forums on careers in the arts for people with disabilities. Report submitted to the National Endowment for the Arts and VSA arts. Los Angeles, CA: National Arts and Disability Center, University of California Los Angeles.

- Raynor, O. (2003). 2002 statewide forums on careers in the arts: Report and recommendations. Report submitted to the National Endowment for the Arts and VSA arts. Los Angeles, CA: National Arts and Disability Center, University of California Los Angeles.

- Rooney, R. (2004). Arts-based teaching and learning: Review of literature. Washington, D.C.: VSA arts.

- Siebers (2008). Disability theory. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

- Swain, J. and French, S. (2000). Towards an affirmation model of disability. Disability & Society, 15(4), 569-582.

- Taylor, M. (2005). Self-identity and the arts—Education of disabled young people. Disability & Society, 20(7), 763-778.

- Walker, P. (1998). Artists with disabilities: A cultural explosion. Paper presented at ArtsACCESS, the National Arts and Disability Center online conference, September 1998. Retrieved from http://nadc.ucla.edu/ArtistswithDisabilitiesPamWalker.pdf.

List of Figures and Captions

Figure 1

© 2002 Jonathan Wos, Self Introspection, watercolor (22.5" x 30")

2002 Road Trip: A Journey of Discovery, Grand Prize

A man in blue jeans sits near a tree, looking down a road to where some bones and a knife are scattered in a white field. An empty wheelchair stands nearby.

Figure 2

© 2004 Isaac Powell, Questions of Symmetry, acrylic, graphite and ink on panel (48" x 48" x 3.75")

2004 Driving Force Exhibit, First Award

At the top of the panel is an illustration of a prosthetic arm. Underneath it, a vase or urn is centered in a red background, with a pear, an orange, and other more abstract objects floating in the foreground.

Figure 3

© 2003 Katherine Skipper, Under the Table, oil on canvas (42" x 50")

2004 Driving Force Exhibit, Award of Excellence

A character in a joker's costume dominates the left side of the canvas, with three smaller human-like figures to the right. The entire canvas is full of bright colors, blurred images, and dripping paint.

Figure 4

© 2004 Angelica Busque, Morning Star, graphic novel (pen and ink)

2005 Shifting Gears Exhibit, Second Award

A young woman with glasses and dark hair dances in a crowd of people.

Figure 5

© 2002 Catron Peterson Burdette, Self Portrait Diptych, oil on wooden door panels (68" x 60")

2002 Road Trip: A Journey of Discovery Exhibit, Award of Excellence

Two door panels are presented side by side. On the left panel is a black and white illustration of a girl in shorts standing next to a rocking chair. Part of the picture is blurred out. The right panel shows the same scene in color.