Comics, a relatively understudied medium for representations of disability, have enormous potential for providing important critical perspectives in disability studies. This article examines two recent comics that portray individuals with autism: The Ride Together by Paul and Judy Karasik and Circling Normal, a compilation of the comic strip Clear Blue Water by Karen Montague-Reyes. I argue that these comics' unique narrative geometries make them ideally suited for depicting cognitive disabilities in the nuanced context of embodied life. Through their reworking of stereotypes and their unique portrayals of autism, Circling Normal and The Ride Together demonstrate the power of comics to rewrite (and redraw) traditional scripts of cognitive disability and break the confining cultural framework through which some people are seen and others overlooked.

"We haven't even begun to explore what comics are capable of, and I want that fact on an emotional level to be received by my readers….Because we do have a tendency to assume that the world as we see it…is pretty much the only world there is."

Introduction

In the recent renewal of interest in writing comics and graphic novels, a number of new works have included representations of disability. From a storyline about disabled teenager Shannon Lake in the popular syndicated strip For Better or For Worse2 to the wheelchair-bound protagonist of the web comic dizABLED,3 comics are literally making visible the stories of individuals and groups who have largely been excluded from our social and political narratives. The unique forms of comics are especially promising for representing the experiences of people with cognitive disabilities, who often find the traditional linear narrative of the autonomous subject difficult, if not impossible, to construct and communicate. Because this traditional narrative format is often seen as an essential component of constructing one's selfhood, difficulties in cognition or communication often lead to the perpetuation of stereotypes about the loss or lack of intelligence and personhood in those without "normal" brain function. These factors make issues of representation that much more important for people with neurological differences whose experiences may not best be expressed using traditional narrative forms.

Although a visual medium might not initially seem most appropriate for representations of disabilities that are often termed "invisible" (because they cannot immediately be read by looking at a person), comics are able to represent aspects of disability that text alone cannot, such as the crucial importance of embodiment in the lived experiences of people with disabilities. The physical body cannot be isolated in the attempt to understand and include people with disabilities in every aspect of society, nor can the individual be separated from their numerous attachments and relationships in the world. Comics' ability to represent complex interactions of emotions, thoughts, movements, and social relationships creates a promising opportunity for remedying the inadequacy of many contemporary representations of cognitive disability. In this study I will focus on representations of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) by examining two comics that portray families' experiences with young children who are diagnosed with autism: The Ride Together by Paul and Judy Karasik and Circling Normal, a compilation of the comic strip Clear Blue Water by Karen Montague-Reyes. 4 By outlining innovative narrative geometries of text and image that can more flexibly represent both the embodied and social experiences of people with autism, I will demonstrate that comics have a crucial role to play in the field of disability studies as scholars attempt to become more inclusive in their considerations of cognitive disabilities.

Disability Studies and the Emphasis on the Physical

An important area of disability studies scholarship is the ongoing discussion over how to conceptualize and describe disability. The historical (and still common) understanding of disability describes it as a medical condition, which implies that disabilities can (and should) be treated if possible. As disability scholar and activist Simi Linton describes, "the medicalization of disability casts human variation as deviance from the norm, as pathological condition, as deficit, and, significantly, as an individual burden and personal tragedy" (11). The growing field of disability studies largely rejects the dominance of this medical model and instead considers disability within a social-constructionist framework. Under the social model, a physical or cognitive impairment only becomes a disability when society fails to fully include the person, who may face obstacles such as physical barriers, prejudice, or exclusion from social justice.

The current social model cannot fully account for all aspects of disability, however. Despite promising developments in recent years such as alterations to the built environment resulting in increased accessibility, our society still frequently excludes and stigmatizes disability. In particular, the social model does not provide adequate understanding of cognitive disabilities, which do not disappear with the alteration of the disabled person's environment (though they often do become less limiting when cultural perceptions are altered). As Mark Osteen observes in Autism and Representation, disability scholars have perhaps overemphasized the social construction of disability, leading to a lack of studies of cognitive disability in the field. The majority of scholarship on disability thus far has focused on physical disabilities, a fact Osteen links to several possible factors: the strong and important ties of disability studies with disability activism, which has concentrated on increasing accommodations such as curb cuts, ramps, and accessible architecture; the difficulty of fitting current theories of representation to people with "invisible" disabilities; or the fact that people with cognitive disabilities often have difficulty communicating, which makes assessment of abilities difficult and advocacy by nondisabled caregivers necessary (5-6).

Because of the lack of perspectives on cognitive disabilities (and autism in particular) in the disability studies field, Osteen calls for more "empathetic scholarship," which entails both working on representations of autism in dialogue with autistic persons and combining rigorous scholarship with the experiential knowledge non-autistic writers have gained as family members and friends of autistic persons (8). Following philosopher Martha Nussbaum's description of empathy as the "imaginative reconstruction of another's experience, without any particular evaluation of that experience," Osteen argues that most popular representations of people with autism are not truly empathetic, but instead reinforce neurotypical experiences (for example, by placing value on "overcoming" autism), thereby silencing rather than valuing the autistic perspective (8).

Autism in Comics: Circling Normal and The Ride Together

Comics are a prime medium for the type of empathetic scholarship Osteen describes, particularly for studies of cognitive disabilities such as autism. Graphic artist and comics scholar Scott McCloud believes that part of the value of comics lies in their ability to bridge minds, to connect people despite our many differences. Elements of comics such as frame size, layout, and a wide range of pictorial styles can be used to invite identification and engagement as the reader visualizes the thoughts of another. As McCloud observes, "We all live in a state of profound isolation. No other human being can ever know what it's like to be you from the inside....The wall of ignorance that prevents so many human beings from seeing each other clearly can only be breached by communication" (194, 198). As a popular form that is both entertaining and widely accessible, comics can help us to breach the "wall of ignorance" that damaging stereotypes build up around people with autism.

Although The Ride Together is marketed as a memoir and Clear Blue Water is not, both forms of graphic art demonstrate the type of empathetic representation Osteen seeks: Paul and Judy Karasik describe their experience of growing up with their autistic brother David, and Karen Montague-Reyes explains in an interview that she has loosely based her strips about Seth on her life with her autistic son, Sawyer. These authors take care to create realistic representations of autism that reflect their lived experiences. They use the medium of the comic strip to bring their characters to life, deploying images to complement the textual narratives that may not always be readily available to people with autism. The specifics of the form allow for a range of representations of specific features of autism: for example, the overwhelming chaos of intensified or unfiltered sensory inputs can be displayed with glaring colors, overlapping borders, and jagged lines; they can be described textually, through clinical or parental voices; and they can also be described through the gestures, embodied responses, or redirections of focus that the person with autism might employ to cope with their environments.

One of the many interesting features of Circling Normal is its ability to depict the complicated and communal experience of disability as shared by an entire family. Circling Normal follows the experiences of a multiracial American family whose son Seth is diagnosed with autism at the age of two. As she explains in an interview, Montague-Reyes wants to show that a family that was funny and happy before learning that their child has autism can still be funny and happy afterwards: autism alone does not define them ("New Cartoon Strip"). Portraying autism as an entire family's experience moves away from the oversimplified perspective of disability as either a solely medical issue that should be cured or a socially constructed phenomenon with little biological basis. Circling Normal challenges these disability stereotypes, portraying Seth more realistically as a complex human being with various abilities as well as weaknesses. Seth's family's narratives also resist traditional depictions, representing disability neither as a blessing to inspire them nor as a medical condition to be cured. Instead, the family struggles to sort through the cultural narratives of disability available to them, seeking their own definitions of meaning and personhood for Seth. The comic demonstrates that the experience of autism is not the individual burden that Linton describes; it is also reflected in and influenced by the family members and other individuals with whom the autistic person interacts.

The potential for comics to demonstrate intense emotional experiences produced by Seth's autism can be seen in an early Clear Blue Water strip that shows Seth's parents receiving Seth's initial test results (they take him to the doctor because of unusual behavior such as hand-flapping, lack of speech, and extreme agitation) (Fig. 1). In the four frames of this comic strip, we not only read Eve and Manny's verbal responses to the news that the tests are normal, we are able to see their physical and emotional responses as well. Joy is evident upon their faces, and they sing and dance in relief at the news. However, for a brief moment (or an extended one, depending on how long we study the third frame), we as readers are allowed a more complicated glimpse into Eve and Manny's emotions as they ask each other, "But if he's so normal, why doesn't he talk?...and why is he licking the couch?" Scott McCloud describes the depiction of temporally disparate moments in a single sequence as a "landscape of time" upon which viewers can gaze. The relationship between time and space in comics is not simple, as we see in this strip — the last frame of celebration is wider than the third frame, a technique that typically creates an extended moment in the rhythm of our reading experience. However, here the shorter third frame draws our attention as it indicates a disruption in Eve and Manny's experience — their celebrations are interrupted by a moment of doubt about the diagnosis. Though the extended action of the last frame attempts to assuage this disturbance, it cannot replace it. Each moment remains static, immune to the inconsistencies of memory, and Eve and Manny's fears are permanently drawn in tension with the joyful behavior through which they attempt to repress their anxieties.

Figure 1. "That was Dr. Ross with Seth's Test Results." Karen Montague-Reyes, Circling Normal (Kansas City: Universal Press Syndicate, 2007): 13.

Figure 1. "That was Dr. Ross with Seth's Test Results." Karen Montague-Reyes, Circling Normal (Kansas City: Universal Press Syndicate, 2007): 13.

The following strip demonstrates even more visual and emotional density. While the doctor tells her that early intervention will improve Seth's "long-term outcome," Eve is isolated by her inability to see beyond the normative roles of football player, college graduate, husband, and father that dominate her expectations for her child (Fig. 2). Montague-Reyes compacts the entire narrative of Seth's life as Eve imagines it to a single thought bubble, a visual story that for the reader is almost simultaneously written and erased as the dream-bubble pops above Eve's head in a starry "POOF." Although anxiety over an unknown future overwhelms the mood of the scene, the frame also represents the first moment in which Eve begins to develop her expectations for Seth by connecting with him, rather than scripting his life in advance based on cultural dictates for measuring human value.

Figure 2. "Aggressive early intervention will really help Seth's long-term outcome." Ibid. p. 16.

Figure 2. "Aggressive early intervention will really help Seth's long-term outcome." Ibid. p. 16.

An important aspect of the representation of cognitive disability in comics is what Will Eisner calls "the non-verbal 'language' of sequential art" (44). In an absorbing strip composed of entirely silent frames, Montague-Reyes depicts the emotional impact of the diagnosis on each member of Seth's family (Fig. 3). The gutter, the space between the frames, disappears, creating a circular strip of closely connected frames that demonstrates the extreme emotional tension of the situation. Here we see both the intense need for and desperate rejection of emotional and physical connection — the various family members alternately cling to and push each other away as they feel despair, anger, frustration, and fear. The experience of pain in this strip is both individual and shared. The exception to the chaotic activity seems to be Seth himself, who is shown in the first and last frames as completely removed from his family's anguish — in the first frame he stares out the car window while his mother and sisters are tense with worry, and in the last frame he is shown alone and smiling as he plays with a toy, oblivious to the emotional scene surrounding him. However, because the gutters are removed between frames, creating a circular layout, Seth's frames do not close the strip — literally surrounded by the members of his family, Seth cannot be read in isolation.

Figure 3. Silent panel. Ibid. p. 17.

Figure 3. Silent panel. Ibid. p. 17.

The format of this strip mirrors Seth's disability itself through its silence. Even though he is almost three, Seth has yet to speak, making gestures, sounds, and body language important components of his vocabulary. As Susan Squier observes, comics have enormous potential for "the full encounter with the experience of disability," making the narrative of that experience "most fully possible because they include its pre-verbal components: the gestural, embodied physicality of disabled alterity in its precise and valuable specificity" (86). The importance of embodiment is further enhanced by the particular communicative difficulties of those with autism. At times, as in this strip, their story must be told entirely through the body, multiplying emotion across the surface of both the characters and the strip as a whole and emphasizing the importance of empathy without language.

Embodiment and alternative forms of communication are also highlighted in the nonfiction book The Ride Together, a memoir written by siblings Paul and Judy Karasik about their experiences with their autistic brother David. In alternating comics and prose sections, Judy Karasik writes descriptive chapters about events that took place during her childhood while Paul Karasik draws chapters that allow us to visually delve into the characters' psyches.5 In the following scene, Paul reluctantly takes David to a Three Stooges film festival (Fig. 4). He is constantly embarrassed by David's excited hand-flapping, vocal enthusiasm, and disregard for other audience members, and he repeatedly tells David to be quiet (125). After he is the one that is hushed by the audience, not David, Paul realizes that David's excitement is not only not bothering anyone, but is also part of David's enviably powerful interaction with the film.

Figure 4. "Ahem, perhaps YOU should be quiet, young man." Paul and Judy Karasik, The Ride Together (New York: Washington Square Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc., NY, 2004): 126.

Figure 4. "Ahem, perhaps YOU should be quiet, young man." Paul and Judy Karasik, The Ride Together (New York: Washington Square Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc., NY, 2004): 126.

In this imaginative full-page series of images, Karasik uses a number of techniques to vividly represent the energy of David and Paul's theatre experience. Slanted frames portray the disjunction with Paul's previously composed attitude (represented by more conventional rectangular frames), and motion lines, detailed gestures, and varied character positions show the dynamic movements of the action as Karasik blurs the distinction between viewer and viewed. In the middle of the page, a thrown pie literally breaks the traditionally square frame as it moves from the movie screen to the audience, inciting a fanciful pie fight (punctuated by sounds like "SPLAT!") that Paul enjoys just as much David.

Like Montague-Reyes's experiments that merge the experience of disability with the form through which it is depicted, Karasik's strips are exciting in their transcendence of both the traditional narrative form and typical interpersonal relationships. Paul begins to understand that for David, they are not in a theatre; they are actually participating in the film itself. By making an effort to look at things from a new perspective (which he is simultaneously allowing and encouraging his readers to do), Paul's character begins to see that his brother's way of experiencing the film might actually be stimulating and exciting in a way that his own disinterested view is not. Paul is now interacting with David in David's world, and the resulting action provides the men with a more intense connection with the film and with each other. In this way, The Ride Together demonstrates to its readers that while people with disabilities may have unusual ways of interacting, this does not mean they are incapable of communication or enjoying close relationships, or that their experience of the world is somehow inferior to others.

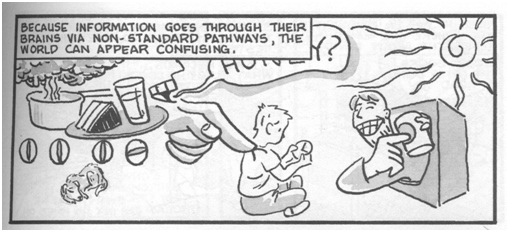

The Ride Together uses additional comics techniques to more directly convey the intensity of external stimuli as they are experienced by many people with autism. The reader is presented with the following frame:

Figure 5. "Because information goes through their brains via nonstandard pathways, the world can appear confusing." Ibid. p. 15.

Figure 5. "Because information goes through their brains via nonstandard pathways, the world can appear confusing." Ibid. p. 15.

In this frame we read about the confusion of information received by the brains of many with autism. Simultaneously, we see distorted ratios of objects and sounds surrounding a young boy who concentrates on a clock, a focus on the orderly system of time-keeping that likely allows him to minimize the stimuli to which he attends. The touch of a giant hand collaged with portrayals of food and faces represents the disruption he feels at being questioned, while a dog sleeping in the background emphasizes the striking disjunction between the relative calm of the boy's external environment with his intensified and confusing internal states. By presenting this scene in a single frame with no internal borders, the author conveys the flood of sensations that bombard the boy: depictions of a blazing sun, smells, and voices from both television and someone in the room compete for attention and fill the scene, held at bay only by the boy's attention to his clock.

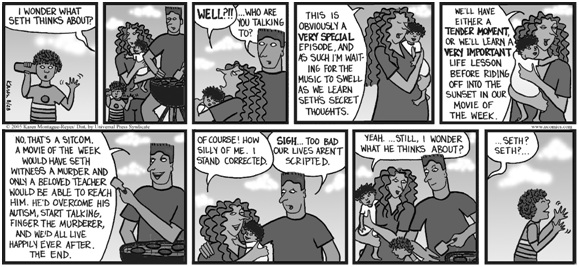

The importance of perspective is also demonstrated in Circling Normal, as Montague-Reyes shows Seth's mother attempting to guess his thoughts (Fig. 6). In this strip, Seth is older and his family has begun to recognize the limited options and restricting nature of the cultural scripts available for the stories of people with disabilities. Nevertheless, Eve chooses to read her son as a person with cognitive capacities despite his inability to describe them to her, asking her husband, "I wonder what Seth thinks about?" Recognizing the futility of appealing to traditional disability narratives to provide any kind of empathetic answer to this question, she and Manny joke about what would happen next if their lives played out according to typical media accounts of disability. Eve says that in their movie of the week she is waiting "for the music to swell as we learn Seth's secret thoughts. We'll either have a tender moment, or we'll learn a very important life lesson." Likely referencing the 1994 Beresford film Silent Fall, Manny responds, "A movie of the week would have Seth witness a murder and only a beloved teacher would be able to reach him. He'd overcome his autism, start talking, finger the murderer, and we'd all live happily ever after. The End." Laughing, Eve notices Seth again and says "Still, I wonder what he thinks about," calling his name as Seth closes his eyes and (seemingly happily) flaps his hands at some stimulus only he notices. Any understanding of what he is really thinking will have to come from an empathetic attempt to see him in a fully lived context, connecting with him on his own terms and becoming receptive to forms of communication that go beyond traditional narrative scripts.

Figure 6. "I wonder what Seth thinks about?" Montague-Reyes p. 41.

Figure 6. "I wonder what Seth thinks about?" Montague-Reyes p. 41.

Imagination is what comics are all about, and thus they enact the very process of imagining other minds that I am advocating. Comics necessitate interactions between reader and text that allow for fuller understanding of disabilities as they exist in relation to society. Several scholars have noted this interactive aspect of comics, often described as a fragmented or unstable surface that requires an active reading experience. As Charles Hatfield puts it, "the very discontinuity of the page urges readers to do the work of inference, to negotiate over and over the passage from submissive reading to active interpreting" (xiv). When we read comics, we are constantly "observing the parts but perceiving the whole," as McCloud defines the phenomenon of closure (63). Closure is essential to comics, which present distinct moments with gaps outside and between frames that the reader must fill by imagining the missing pieces of the narrative in what McCloud calls "a silent dance of the seen and the unseen, the visible and the invisible" (92). Connecting the experience of reading comics to the experience of living in the world, McCloud stresses the importance of imaginative engagement and "reading" for interaction with others, writing that "in recognizing and relating to other people, we all depend heavily on our learned ability of closure" (63). Using inference and imagination to read other minds is an ordinary and daily event for many people, but one that is crucial to extend to those who cannot tell us their thoughts through ordinary means.

Superheroes and Supercrips

A final unique characteristic of these comic strips is their ability to subvert the classic comic theme of the superhero and use it in new ways that promote the cause of disability rights. There has been much discussion in the last decade of the "supercrip," a common representation of a person with a disability who overcomes all of his/her "obstacles" (i.e., disabilities or differences) and achieves normal or supernormal feats such as climbing mountains or sailing ships. The supercrip is seen by most disability rights scholars and activists as an impediment to the process of promoting an accurate understanding of disability for people both with and without disabilities. As mass media and disability scholar Beth Haller describes,

the power of the Supercrip is a false power….These beliefs tie into societal attitudes. Society holds few expectations for people with disabilities — so anything they do becomes "amazing." Any disabled person who does any basic task of living becomes "inspirational." And any disabled person who does more than daily living, such as competing as a professional golfer or playing pro baseball with one arm, becomes a Supercrip. (2000)

Disability and comics scholar José Alaniz summarizes his critique of the supercrip by writing, "the stereotype of the supercrip, in the eyes of its critics, represents a sort of overachieving, overdetermined self-enfreakment that distracts from the lived daily reality of most disabled people" (305).

In his article "Supercrip: Disability and the Marvel Silver Age Superhero," Alaniz explores the origin of the supercrip concept by analyzing comic superheroes and their reliance on an invisible, disabled, structuring Other, without which they could not exist (305). Citing numerous examples from comics, Alaniz demonstrates that comic book superheroes must first "overcome" a disability to achieve their status. At times, according to Alaniz, "the super-power will erase the disability, banishing it to the realm of the invisible, replacing it with raw power and heroic acts of derring-do in a hyper-masculine frame" (307). Like the supercrip, superheroes often overcompensate for their physical or psychological differences. Another common comic-book figure is the Supervillain, a character in which the superpower itself functions as a disability that threatens to escape the character's control, causing him or her to be shunned or attacked by society (313). As Alaniz observes, "supervillains — following the Gothic tradition of revealing the inner disfigurement of the soul by showcasing the disfigurement or spectacular otherness of the body — simplistically reify the ablist reader's unconscious anxieties and prejudices regarding difference (be it racial, gender-related, nationalist, class-based, or physical)" (313).

The Ride Together and Clear Blue Water reconfigure the historically disabling representation of the superhero and present an alternative to the disabling stereotype of the supercrip that is so pervasive in contemporary representations of disability. Both of these comics portray autism realistically; David and Seth are shown as ordinary people with lives, preferences, and various abilities as well as weaknesses. Not only do these comics dismantle the supercrip fantasy by eliminating it from their storylines, but they also allow for a new type of hero who is, in fact, a person (un)like any other. By placing "ordinary" individuals (I use scare quotes to emphasize that all so-called ordinary people are anything but) in roles the Superhero would traditionally fill, these comic strips eliminate the need for a disabled Other to compose their heroes against. The Ride Together and Clear Blue Water present superheroes that do not hide difference, but instead embrace it.

In Clear Blue Water, superhero characters which occasionally drop into the script play on comics' frequent reliance on these figures to provide external commentary on the scene at hand. The superheroes in this comic, however, do not have superpowers; they have very particular (and often annoying) personality traits. For example, the strip's "heroes" include Right Wing, who argues an extremely conservative viewpoint with anyone who will listen, and Easily Offended Man, who flies in to save the day whenever anyone commits a blunder of speech by saying something politically incorrect (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. "Remember that really awful picture of you?" Karen Montague-Reyes, Clear Blue Water (July 25, 2004).

Figure 7. "Remember that really awful picture of you?" Karen Montague-Reyes, Clear Blue Water (July 25, 2004).

Easily Offended Man calls attention to debates affecting disability, as his corrections are essentially matters of categorization. In this strip, for example, he interrupts Manny, who is telling his wife she looks "retarded," with "You used the 'R" word! It's 2004! You may not use that word! This is a serious breach," instructing Manny to instead use the word "exceptional." Through the humorous meta-commentary on both the traditional "lessons" of comic book heroes and the debates over appropriate disability terminology, Montague-Reyes demonstrates that one can use a different term for "retarded," but without changing people's understanding of disability itself, the harmful stereotypes will persist no matter what language is used to describe them. In this case, "exceptional" is just as derogatory as "retarded" as Manny (apparently unaware of the potential harm of these stereotypes for his own son) insultingly associates the cognitively disabled with looking "really awful" and having a "vacant stare."

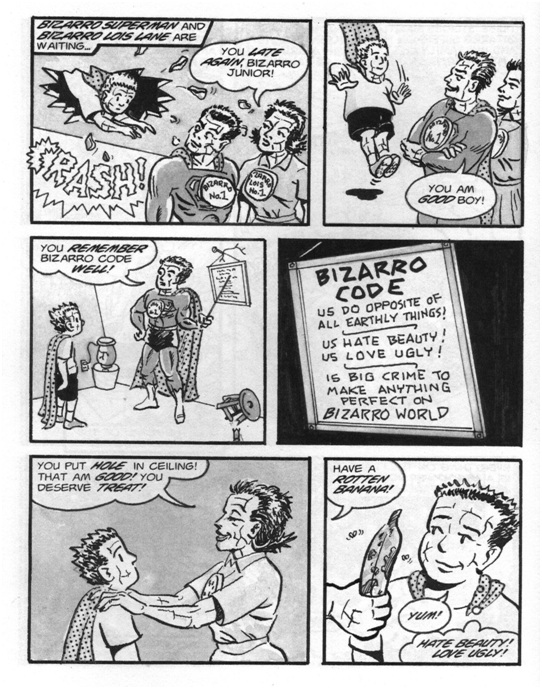

The Ride Together also presents the reader with superheroes that celebrate difference. After fighting with David and being punished by his mother, Paul mentally retreats into his favorite comic, "Tales of the Bizarro World" (Fig. 8). In Bizarro World, Paul becomes the Bizarro-son of Bizarro Superman and Bizarro Lois:

Figure 8. "Bizarro Superman and Bizarro Lois Lane are waiting…." Karasik and Karasik p. 70.

Figure 8. "Bizarro Superman and Bizarro Lois Lane are waiting…." Karasik and Karasik p. 70.

In these strips, Bizarro Paul is not constrained by social laws of order, perfection, or stability. In Bizarro World, it is actually ugliness that is good and imperfection and difference that are privileged. The original Bizarro himself is described by comics fan Don Markstein as a disabled figure: "'Bizarro was a pathetic, quasi-living creature' with 'a brain that functioned at a child's level, behind a face that looked like crumpled-up paper'" ("Bizarro"). The Ride Together distorts the traditional image of the superhero by giving value to the Bizarro World comics, where people with disabilities are the norm rather than the ostracized. Simultaneously, the comic demonstrates that behavioral norms are socially established and often arbitrary, as shown in a scene where Bizarro Paul is chastised for getting perfect grades (71).

Like Clear Blue Water, The Ride Together refigures the superhero in a commentary on perspective. The superheroes in these comics are neither bad nor good, and although they do present a social commentary on certain actions, this commentary largely serves the disability rights movement's purposes by demonstrating that our understanding of people (and superheroes) is largely determined by the way they are presented to us and not by the actual figures themselves. As Squier describes in her discussion of Karasik's Bizarro strips, "In this comic book world of opposites, where the ugly is loved, beauty is hated, and perfection is a crime, Paul sees himself through a new lens, as the one whose perception is faulty. And as readers we are offered a similar opportunity for self-reassessment" (86). These new heroes critique both the superhero and supercrip, promoting an acceptance of difference rather than a need to compensate for it.

Conclusion

As Osteen notes in his descriptions of empathetic scholarship, understanding autism requires an appreciation for unusual and diverse modes of communication (298), a goal which will require humanities scholars to incorporate many different forms and perspectives in studies of disability. Scholarship focusing primarily on written texts may overprivilege traditional discursive forms, excluding gestural, bodily, collaborative or other understudied ways of interacting with the world and with others. Studies of comics, in contrast, emphasize the importance of multiple embodied and cognitive styles of living, by portraying, for example, the powerful communicativeness of silence and other nonverbal forms of expression. Because of features such as the ability to depict both temporal and spatial relationships simultaneously, comics can powerfully convey the experience of disability in a lived context. The flexibility of the comic strip allows the author to demonstrate both the impact of autism on a family and, paradoxically, the "ordinariness" of the same family, which has ups and downs just like any other. The families in Circling Normal and The Ride Together do not constantly revolve around Seth and David — the other children and the parents' interactions are all important to how the family gets along in the world. Each member has their own character flaws, and each brings important styles of communicating and caretaking to the family circle. Seen from this perspective, autism becomes part of the family's collective identity rather than something the family must "face." Weighty topics of debate such as whether to accept or normalize children are directly addressed in the strips, but more often these macroscopic concerns are particularized in the pleasures and trials of everyday life.

Comics provide a means by which to see into another's life, and therein recognize our own. As graphic artists such as Eisner and McCloud have often noted, the comic style itself is particularly engaging because of the level of participation it requires from its audience. Gutters, the space between the frames of comics, invite the reader to create the passage of time, the social dynamics, and the specific events that have occurred between frames. Unlike text, whose symbols are usually limited to a single font throughout, the very lines of comics can convey quickly changing emotions, for example, by using jagged lines to demonstrate anxiety. Through these and other techniques such as the relative fullness or sparseness of single panels, thought bubbles, and sound effects, comics can affectively represent the experiences of their characters. These techniques make comics an important form for academic studies that wish to incorporate the fullness of the experience of people with autism. Comics can depict combinations of motor, sensory, emotional, social, or cognitive factors affecting a person, thereby avoiding the reduction of that person to a stereotype of one particular facet of his or her identity. The incorporation of these features into the comic Circling Normal and the graphic and narrative memoir The Ride Together make them excellent examples of empathetic representations of autism: these comics reveal both the ordinariness of aberration and the value of difference.

Works Cited

- Alaniz, José. "Supercrip: Disability and the Marvel Silver Age Superhero." International Journal of Comic Art 6.2 (Fall 2004): 304-324.

- Eisner, Will. Comics and Sequential Art: Principles and Practice of the World's Most Popular Art Form. Tamarac, Florida: Poorhouse Press, 2004.

- Haller, Beth. "False Positive." Ragged Edge Online. (January/February 2000). <http://www.ragged-edge-mag.com/0100/c0100media.htm>.

- Hatfield, Charles. Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2005.

- Karasik, Paul and Judy Karasik. The Ride Together: A Brother and Sister's Memoir of Autism in the Family. New York: Washington Square Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc., NY, 2004.

- Linton, Simi. Claiming Disability: Knowledge and Identity. New York: New York UP, 1998.

- Markstein, Don. "Bizarro." Don Markstein's Toonopedia, 2005. <http://www.toonopedia.com/bizarro1.htm>.

- McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperPerennial, 1993.

- Montague-Reyes, Karen. Circling Normal: A Book about Autism. Kansas City: Universal Press Syndicate, 2007.

- ---. Clear Blue Water. Comic strip from July 25, 2004. Copyright Karen Montague-Reyes. Available at http://www.gocomics.com/clearbluewater/ and http://clearbluewatercomic.wordpress.com/.

- "New Cartoon Strip 'Clear Blue Water' Addresses Autism." Universal Press Syndicate, 2004. <www.amuniversal.com/ups/newsrelease/?view=162>.

- Osteen, Mark, ed. Autism and Representation. New York: Routledge, 2008.

- Squier, Susan. "So Long As They Grow Out of It: Comics, The Discourse of Developmental Normalcy, and Disability." Journal of Medical Humanities 29 (2008): 71-88.

- Wiater, Stanley and Stephen R. Bissette, eds. Comic Book Rebels: Conversations with the Creators of the New Comics. New York: Donald I. Fine, 1993.

Endnotes

-

Quoted in Comic Book Rebels: Conversations with the Creators of the New Comics. Stanley Wiater and Stephen R. Bissette., eds. New York: D.I. Fine, 1993.

Return to Text -

http://www.fborfw.com/features/shannon/

Return to Text -

http://www.dizabled.com

Return to Text -

In this analysis I use the titles Circling Normal and Clear Blue Water interchangeably. While Circling Normal reprints the strips of Clear Blue Water unaltered, it excludes the strips of the comic that do not deal directly with autism.

Return to Text -

Although the power of the memoir results from the combination of the comics and prose together, I will focus solely on Paul Karasik's chapters of the book, which demonstrate my claims about the potential of comics for representing disability.

Return to Text