Introduction

Israel is a country with a relatively short and somewhat unusual history. Having been created by the United Nations in 1947, it is a highly militarized and relatively developed country which has experienced a number of wars since it was created. This paper examines ways in which this history, and resulting social structure and culture, have affected disability policies and, in turn, disability protests.

Protests are political reactions to policies. As such, they are one type of tactic used by social movements (Tarrow, 1996; Tilly, 1978). Protests are organized attempts to change an aspect of the social or political situation in which groups find themselves through the use of means that are non-normative. Not all social movement actions are at this non-institutionalized, disruptive end of the action continuum, and not all social movements use protests. (This is true particularly of social movements that focus on post-modern and post-materialistic values, life styles, and self-actualization, rather than on political issues.)

This paper analyzes protests that are related to disability and are in reaction to disability policies that have arisen in Israel since its inception as a country. These policies are reviewed, and then the patterns of protests that occurred in reaction [we must assume] to these policies are discussed. This paper examines data about protests which occurred in Israel, but, unlike those papers which analyzed one or a few important protests (Rimmerman and Herr, 2004; Rimon-Greenspan, 2006a, 2006b), this paper analyzes 36 protests which occurred between 1970 and 2006. These analyses paint a different picture of the relationship between disability protests and disability policies than has been painted in the past.

Background: Disability Policy and Politics in Israel

Social policy regarding disability in Israel has separated "needed' from 'needy' disabled people. Those who were "needed" disabled are those who served the State in some way. Included in this category, initially, were people disabled during the first war — the War of Independence — that produced approximately 2,000 disabled veterans. Later, other categories of "needed" disabled were added, including disabled police officers, Jews injured while serving in any army which fought against the Nazis during World War II, Jews injured while fighting the British during the period of the British Mandate, civilian victims of the Nazis who were not eligible for reparations from Germany, Jews persecuted for Zionist beliefs, families with children while one family member served in the armed forces, and, in 1969, civilians injured in terrorist attacks against Israeli targets — in Israel or anywhere else in the world (Gal and Bar, 2000: 587).

While policies were not created at the same time for all of these groups, they all followed the model of extremely generous access and benefits, which were established for war-disabled veterans beginning in 1949. These benefits include — for those with at least a 10% disability — a relatively generous pension, which is higher than all of the 11 countries — except the US — with which Gal and Bar (2000: 583) compared Israeli policies; a variety of rehabilitation services; loans; and even discretionary benefits. Benefits for the other groups of "needed" disabled people were not as generous, but they were similar — and they were also structurally located within the Ministry of Defense (MOD), which also has responsibility for the benefits programs for disabled war veterans.

Attention to people with work-related disabilities did not even appear in Israeli law until 1953. And attention to people with disabilities which were considered to be "natural," meaning not caused either by war or industrial accidents, did not emerge into separate law until 1973, although people with disabilities were covered under local welfare services/public assistance programs. This latter law, the General Disability Act, 1973, and its successors, provide access to disability benefits for people whose medical disability is rated as being 40 % or more. However, the amount of money it provides is much less than that provided for war veterans — usually around the official poverty line (Gal, 2001).

The principles of allocation upon which the programs are based also differ. The Disabled Veterans program is based upon the principle of compensation, while the General Disability program is based upon the principle of need. There is also a small Work Injury program which combines the allocative principles of the other two and which is more generous than the General Disability Program (Gal, 2001).

Disability has been a marginal political issue (Rimmerman et al., 2005) which had been explicitly dismissed as being unimportant during the 1960's (Gal and Bar, 2000: 590). Organizationally, disabled war veterans were also quite separate from all other groups of people with disabilities. ZDVO, the Zahal Disabled Veterans Organization, began in 1949. While it did engage in one strike in 1950 — to demand employment for veterans (Gal and Bar, 2000: 580), contentious collective action was not its purpose. Nor did it need to engage in such action. In 1956, a single disabled person received 9,700 Israeli liras from general public assistance while a disabled veteran received 91,200 (Gal and Bar, 2000: 591). In addition to these comparatively more generous cash benefits and to the non-cash benefits its members receive, ZDVO has yearly meetings with the Ministry of Defense to discuss these benefit levels. Furthermore, it is partially funded by the MOD. It has had no reason to form a coalition with other groups of people with disabilities — nor has it done so. In fact, it has "pointedly refrained from seeking more general legislation or addressing the needs of the disabled population as a whole" (Gal and Bar, 2000: 592). "Needy" people with disabilities had no national umbrella organization until 1980 (Yishai, 1991: 79), although disability-specific organizations (For a definition of the term see Barnartt and Scotch, 2000) existed before that. A national organization that focuses on the rights of persons with disabilities did not emerge until 1992 (Rimon-Greenspan, 2006b).

If we assume that there are issues related to rights which are different issues than economic survival or services,1 we can say that rights-based laws which relate to people with disabilities first emerged with the Special Education Law of 1988, which emphasized mainstreaming (Rimmerman et al., 2005). A few other laws dealt with relatively small issues, such as the one mandating sign language captioning for television, passed in 1992. A general law relating to equal rights for persons with disabilities [the Equal Rights for People with Disabilities law] was passed in 1998, although only a few of the rights provisions — those mandating non-discrimination in employment and the right to public transport, primarily thorough para-transit, were actually signed into law.

Given the inequalities of this two-tiered system regarding disability policy, in a society at least partially formed with the goal of promoting equality (Spiro, 1965), one might expect that people with disabilities would have become quite vocal in expressing their grievances through contentious politics. A few commentators (Rimmerman and Herr, 2004; Rimon-Greenspan, 2006a, 2006b) have argued that this has happened only quite recently, in the late 1990's, with the development of a new disability rights movement in Israel. However, the data about protests show that discontent with Israeli disability policy began much earlier than that. These data also cast doubt upon the contention that these later protests focus only, or primarily, on disability rights.

Methodology

This paper is based upon event-history analysis, a research technique that has been used in studies of social movements in the US (e.g. Gamson, 1990; McAdam, 1997; Olzak, 1989) and other societies (Mueller, 1997).2 This methodology analyzes characteristics of protest events, not of activists, and it often presents quantitative, rather than qualitative, results. The use of this technique in this paper is not meant to discuss or measure the entirety of one or more social movements related to disability. Rather, this paper analyses protests as one type of collective activity in which social movements engage.3 It does not analyze organizations or specific protest incidents but rather looks at patterns of protests over time.

For this paper, reports of protests were collected from a number of newspapers using print indices and Lexis Nexis as searching tools. Information was also gathered from interviews conducted with several disability activists in Israel during the summer of 2006 and from World Wide Web sites of organizations involved in protests. Based upon the information gathered, for each incident of protest, variables were coded and data were entered into an SPSS/Windows system file for analysis. Variables ranged from date and place to the type of disability demand being made, the specific protest demand; if organizations were involved; types of tactics used; protest target; protest duration and size; and whether there were police, violence, or arrests. Only a few of the variables are reported here. The variables and coding used here are those used by the author and colleague (Barnartt and Scotch 2000) in the study of protests in the American context. Some of these variables and categories do not fit the Israeli social structural or cultural context very well. However, for this paper, variables and categories that were seen to fit were selected, and, in a few cases, comparisons are made between the Israeli situation and others that the author has studied in a similar fashion.

This methodology requires the use of very clear operational definitions. In this research, protests, in general, were defined as being: collective, hence including more than one person; contentious, meaning angry, demanding and ideologically based; political, so challenging the power structure and seeking social, as opposed to individual, change; and non-normative, so excluding actions such as lobbying or law-suits, which are normative political activities in American society.4 Collective activities whose goal was fund-raising were not included. Disability-related protests were further defined to include the above-mentioned characteristics but also: 1) to be protests conducted by persons with disabilities or others (assumed to be allies) and 2) to be about an issue with relevance to people with disabilities.5

The type of disability demand being made in the protest was based both upon the types of protesters and the types of demand being made. Based upon these two pieces of information, a judgment was made about the disability group(s) to which the demand was most likely to relate.6 If a demand was related to many or most types of disabilities, it was coded as "cross-disability," following the terminology used by Longmore (1997) and Young (1998). Otherwise, it was coded into a disability-specific category. Up to two disability types could be coded for each protest.7

Disability protests make demands that span a gamut of issues, from accessibility, para-transit and support payments of various types to telethons, education, and assisted suicide. Up to two demands were coded for each protest. In order to reduce complexity, for this paper the demands were recoded into four categories: those related to rights, those related to services, those related to education, and all others. Demands dealing with rights related to issues of accessibility or discrimination, rights, policies, and laws.8 Demands dealing with services were comprised of monetary issues or characteristics or types of services. Demands related to education apply to any aspect of education at any level. Other types of demands included those relating to telethons, assisted suicide, and other issues.

The type of target towards which the protesters addressed their demands was usually clear from the media coverage of the protest. In a few cases it was not, and then decisions were made as to the most likely target. The category of "the public" was only chosen when the public was the explicit — and only — target of the protest.

Because of the inherent limitations of using newspaper data,9 it is not assumed that these protests constitute the entire universe of protests that have occurred. Nor is it assumed that these constitute all of the social movement activity related to disability that has occurred. Rather, it is assumed that contentious protests form one of the many types of collective actions in which social movement engage.10

Results

Some writers are impressed with how frequent protest seems to be in Israel. Lehman-Wilzig (1991) found that, from 1947 to 1991, almost 4,500 protests, related to all types of issues, were documented in the Jerusalem Post. He estimates [but without any basis for this estimation] that this number constitutes about half of all protests which occurred during this period. He also cites polls that show that one out of every four Israeli adults had participated in a protest during the 1980's.11 He refers to the Biblical passage which describes Jews as a "stiff-necked people" (Exodus 32:9) and quotes others in his attempt to prove that this is why there is so much protest in Israel — although some political scientists, cited below, disagree.

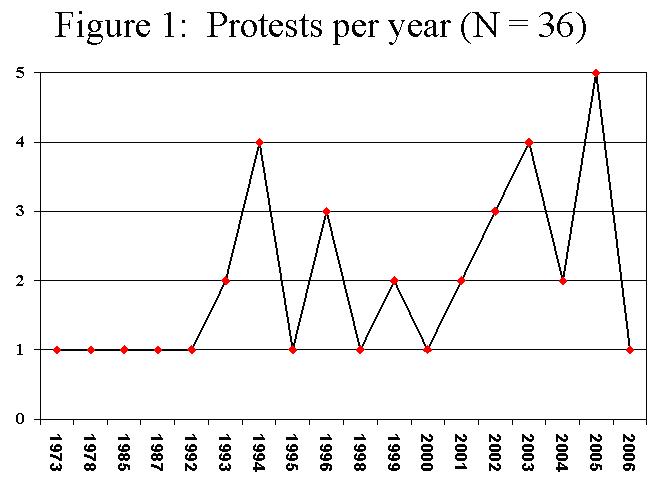

Even if Israel is a "social movement society" (Meyer and Tarrow, 1998), its protests were not, by and large, related to disability. The methodology described above produced indications of only 34 protests, the dates of which are shown in Figure 1. This figure shows that there was one protest each in 1973, 1978, 1985, and 1987; the latter two of these occurred before protests in Israel became more common. There was also one protest in 1992; after that, in many years there was more than one protest. The year in which there were the most protests (5) was 2005, although in both 1994 and 2003 there were 4 protests. Thus we see a pattern of increasing numbers of protests, primarily since 1992.

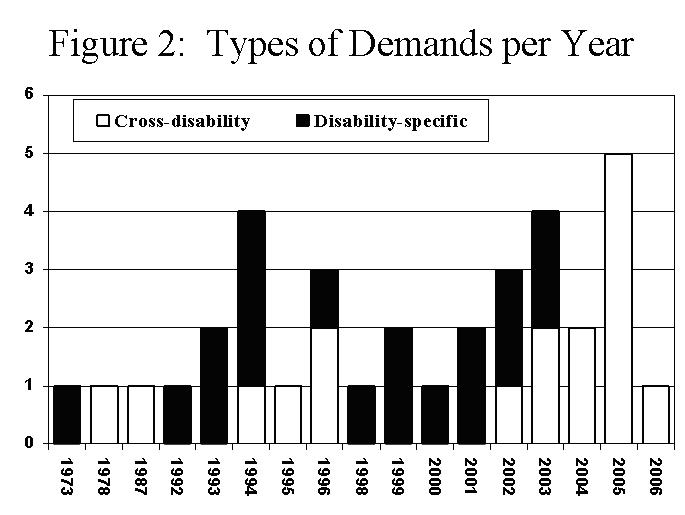

Figure 2 shows how the types of disability demands being made in the protests changed by year. Overall, about 70% of the protest demands were cross-disability as opposed to being disability-specific (not shown). Figure 2 shows that more protest demands were disability specific than were cross-disability in most years. It is only in the last three years that all disability demands were cross-disability.

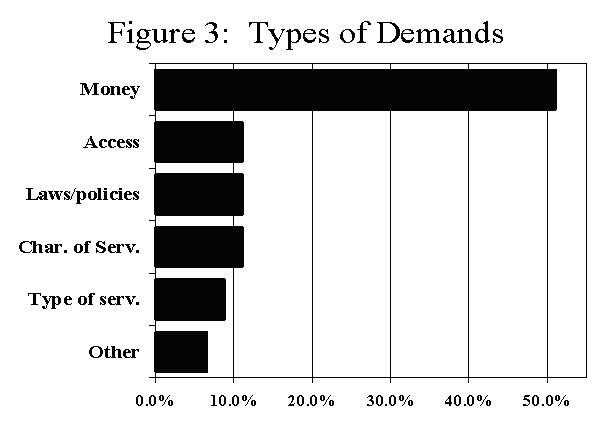

Protests make many demands. Two demands could be coded for each protest. In total, over 75% of all demands made fit into the general category of services, which includes education, while about 13% were related to rights and about 11% related to other demands (data not shown). Figure 3 shows that demands specifically relating to money are by far the most common, comprising over 50% of all demands. Less than 12% of demands fit into any other specific category.

Demands related to money included those related to direct payments as well as those related to governmental or organizational budgets.

Services include any type of assistance provided by governments or organizations. Characteristics of services included location, amount, control over, and other aspects of services.

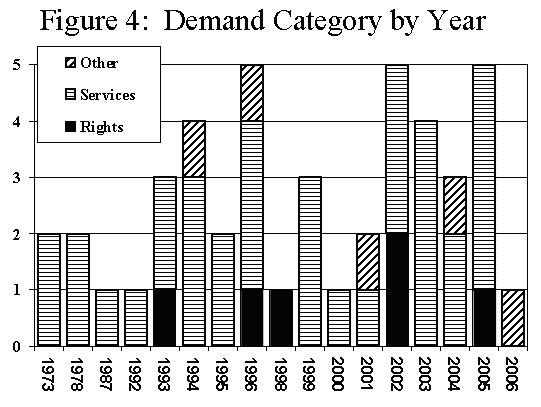

The patterning of the demands should have changed over time, if the authors cited above are correct in their assertion that we have seen the recent formation of a disability rights movement in Israel. Figure 4 shows the pattern of demand type over time. This figure shows that all protest demands before 1993 were related to services. Since then there has been more variability in demand categories, but "services" remains the most common demand category in all years except 1998, 2001, and 2006. It is not empirically true, based upon numbers of protests, that a disability rights movement has formed, but it appears that protests are not just about services any more. As has occurred in the United States (Barnartt and Scotch, 2000) and other countries, the protest picture is not as clear as the rhetoric of "Disability Rights" would suggest.

N = 45 demands. Two demands could be coded for each protest.

Unlike disability protests in the United States (Barnartt and Scotch, 2000), Canada (Barnartt, 2007 forthcoming), and the United Kingdom (Barnartt, 2005), in Israel the target of the protests was almost always the national-level government. In fact, this was true in about 80% of all protests. Additionally, almost all of the protests took place in one of the two largest cities — Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. No protests that we could find occurred in Haifa, the third largest city, and only one occurred in a smaller town. (Data not shown).

One characteristic, which is quite notable about disability protests in Israel, is their length. Of the 8 protests for which the data are clear, 6 lasted for one day or longer. The longest one, which began in December 2001 and continued until March 2002, lasted for 77 days.12 This protest followed, by two years, a protest that lasted for 37 days; it was followed, by a protest by the deaf community, related to deafness issues, which lasted for 39 days.13 As discussed below, it was likely the successes of those three protests together in having their demands met, as much as their length, which are notable for future patterns.14

Thus, we see a fairly consistent pattern to the disability protests. Beginning in 1992, there were small numbers of protests per year, several being quite lengthy. These protests were usually making demands related to money and targeting the national government, and they were almost always cross-disability.

Disability protests were somewhat different than the approximately 450 incidents of non-disability protests studied by Wolfsfeld (1988: 94 - 5), which occurred between 1979 and 1984. The majority of non-disability protests in Israel were either strikes or workers' sanctions conducted by organized groups. Disability protests could not conduct a strike against employers [since many people with disabilities are not employed], and almost 2/3 of the disability protests did not have an organization involved. About one quarter of non-disability protests occurred in smaller towns or villages, but all of the disability protests occurred either in Tel Aviv or Jerusalem. Finally, non-disability protests tended to be short (i.e. lasted only a few hours); disability protests were twice as likely as non-disability protests to last a week or more. Thus, the disability protests differed from other protests in these ways, also.

Discussion

There seem to be two important issues that these results raise:

- Why the protests increased in frequency when they did and not before; and

- Why the protests have not formed a "disability rights" movement.

Regarding the first point, Rimon-Greenspan (2006b) suggests that the legal struggle, which resulted in, the 1998 law led to the emergence of grassroots activism. These data suggest a slightly different picture, since activism had actually started much before that. We suggest it was the successes that were experienced by some of the early activism that engendered the more recent upsurge in protest activity.

The issue of protest success is important when discussing a pattern of protest. The ease with which one can determine the success of a protest depends partially upon the type of demand being made. A protest can have very limited demands, such as being able to meet with an official to discuss an issue. In that case, the meeting is evidence of success. A demand can be for a limited policy change, such as the hiring (or nonhiring) or firing (or nonfiring) of a specific person or specific category of person. Again, success or failure is easily determined. If the demand is broader and involves, for example, the passage of a specific law, it seems as if the success is easily determined: If the law is passed, the social movement is successful. But direct linkage between one or several specific contentious actions and the passage of a law is often not so obvious and usually cannot be determined empirically. Finally, if the demand is extremely broad and somewhat nebulous, for example if the demand is for equality or justice, it is difficult to determine the degree to which any one protest or groups of protests contribute to the success.

In fact, only a little more than one quarter of the Israeli disability protests completely or partially attained their demands. However, this seems to be a relatively high percentage, since in the United States, that number is closer to 15%, and in Canada and the United Kingdom it is lower (Barnartt and Scotch, 2000; Barnartt, 2005; Barnartt, 2007 forthcoming).

Successful protests can have a number of consequences. Successes may lead to similar claims by other claimants (Meyer and Tarrow, 1998: 1), a "revolution of rising expectations" in which early gains won by the protesting group lead to a desire for more gains in other areas, and therefore increased willingness to join a social movement (Payne, 1990: 161). In an example of this phenomenon, Groch (1994: 385) cites the case of a woman who passively observed disability activists protesting for transportation accessibility for several years. After riding an accessible bus won by those protesters, she said, "Now I believe we have to be more forceful" (emphasis added).

Wolfsfeld (1988: 154 - 161) shows that protests in Israel were generally extremely successful in attaining their goals. Only 13% were completely unsuccessful (P. 155). The fact that some of the disability-related protests, especially the longer protests, were also successful predisposed the disability community to attempt to continue its success (and, as noted above, the success of the long, cross-disability protest may have mobilized the deaf community.)

The other question these results raise is why the disability protests are not now focusing on rights. In part, this may have been because the 1998 law was widely perceived to have provided a legislative solution to access and discrimination problems. (Since only a few of its provisions were enacted into law, it seems unlikely that it has been successful, but the perception is that it has.). Additionally, people under the General Disability program — who number more than twice as many as those whose benefits come from the Disabled Veterans program15 — experience both relative and absolute deprivation when compared to those under the Disabled Veterans program (Gal, 2001). The vets, as noted above, are less likely to need services, but they are not organized for protest in any case. Thus, the major focus of the "general disabled" is on their own financial needs as well as their needs for services; demanding rights may be a luxury they can't yet afford. Rimon-Greenspan (2006a) describes the most recent protests as attempting to "thicken" needs-related claims. An additional reason might come from the characteristics of other protests in Israel. Wolfsfeld (1988: 92 - 3) found that over half of protest groups were concerned with economic or material issues and a further one quarter were concerned with education or welfare issues; only about 20% were concerned with political issues. Thus, in this area the disability protests were following in the footsteps of other protests and groups.

Finally, if protests about rights do not loom large on the Israeli protest horizon, it may be because there is no general rights frame into which to insert "disability rights," as occurred in the US (Barnartt and Scotch, 2000; Altman and Barnartt, 1993).

Resource mobilization theory (Jenkins, 1983; McCarthy and Zald, 1973) tells us that a grievance is not enough to fuel a social movement in the absence of a variety of types of resources. Proponents of this theory would say that the policy situation that put disabled people at an extreme disadvantage compared both to veterans and to the non-disabled population was not, by itself, enough to engender the protesting aspects of a social movement. When other conditions make protests become more possible, the grievance can be expressed through protest.

However, even then, one major resource necessary for a disability rights movement seemed to be lacking — an organization. This changed with the formation of a new organization, Bizchut, whose name means "by right"# (Rimon-Greenspan, 2006a, 2006b). But even this organization's activities seem, based upon their newsletters, to deal primarily with getting services.

Conclusion

These results and the discussion show that the patterns of disability protest in Israel were strongly related to the history, political culture, and social structure of the country. Despite, with only a few exceptions, coming later to political protest than did the rest of Israeli society — or perhaps because of it — disability protests followed in the materially based protest tradition. Perhaps the most important aspect of these protests is that, without a strong rights-based protest tradition within Israeli society, the protests focused on services and money but not on demanding rights, except insofar as services should be given "by right," rather than "from charity"

References

- Altman, B. and Barnartt, S. 1993. Moral entrepreneurship and the promise of the ADA. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 4(1): 21-40.

- Barnartt, S. 2005 (June). Trends in disability protests in the US and the UK 1970 - 2004. Presented at the First Annual Conference on Disability and History, Manchester, UK.

- Barnartt, S. 2007 (forthcoming). Social movement diffusion? The case of disability protests in the US and Canada. Disability Studies Quarterly.

- Barnartt, S. and Scotch, R. 2000. Disability protests: Contentious politics 1970 - 1999. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Gal, J. and Bar, M. 2000. The needed and the needy: The policy legacies of benefits for disabled war veterans in Israel. Journal of Social Policy 29(4): 577-598.

- Gal, J. 2001. The perils of compensation in social welfare policy: Disability policy in Israel. Social Service Review 75(2): 225-243.

- Gamson, W. 1990. The strategy of social protest (second edition). Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth.

- Groch, S. 1994. Oppositional consciousness, its manifestations and development: The case of people with disabilities. Sociological Inquiry 64(4), 369-95.

- Jenkins, J. C. 1983. Resource mobilization theory and the study of social movements.

- Annual Review of Sociology (9):99B-122.

- Kasnitz, D. 2001. Life event histories and the US Independent Living Movement. Pp. 67-78 in M. Priestly (ed), Disability and the life course. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lehman-Wilzig, S. 1991 (April 4). The country does protest too much? The Jerusalem Post, P.1.

- Longmore, P. 1997. Political movements of people with disabilities: The League of the Physically Handicapped, 1935-1938. Disability Studies Quarterly 17(2), 94-98.

- McAdam, D. 1997. Tactical innovation and the pace of insurgency. Pp. 340B56 in D. McAdam and D. Snow (eds.), Social movements: Readings on their emergence, mobilization and dynamics. Los Angeles: Roxbury.

- McCarthy, J., and Zald, M. 1973. The trend of social movements in America: Professionalization and resource mobilization. Morristown, N.J.: General Learning Press.

- McCarthy, J., McPhail, C. and Smith, J. 1996. Images of protest: Dimensions of selection bias in media coverage of Washington demonstrations, 1982 and 1991. American Sociological Review 61(3), 478-99.

- Meyer, D. and Tarrow, S. 1998. A movement society: Contentious politics for a new century. Pp. 1 - 28 in D. Meyer and S. Tarrow (eds.), The social movement society: Contentious politics for a new century. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Mueller, C. 1997. International press coverage of East German protest events, 1989. American Sociological Review 62:820-32.

- Olzak, S. 1989. Analysis of events in the study of collective action. Annual Review of Sociology 15:119-41.

- Payne, C. 1990. Men led, but women organized: Movement participation of women in the Mississippi delta. Pp. 156-65 in G. West and R. L. Blumberg (eds.), Women and Social Protest. NY: Oxford University Press.

- Pfeiffer, D. 1988. Divisions in the disability community. Disability Studies Quarterly 8(2):1B3.

- Rimon-Greenspan, H. 2006a (May). The Israeli disability movement between needs and rights. Presented at the Canadian Disability Studies Association Meeting, Toronto.

- Rimon-Greenspan, H. 2006b (June). Claiming a place in the public sphere: Israeli disability politics between advocacy and contentious politics. Presented at the Society for Disability Studies Meeting, Washington, DC.

- Rimmerman, A. Araten-Bergman, T., Avrami, S, and Azaiza, F. 2005. Israel's Equal Rights for Persons with Disabilities law: Current status and future directions. Disability Studies Quarterly 25(4).

- Rimmerman, A. and Herr, S. 2004. The power of the powerless. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 15(1): 12 - 19.

- Snyder, D. and. Kelly, W. R. 1977. Conflict intensity, media sensitivity and the validity of newspaper data. American Sociological Review 42(1):105-23.

- Spiro, M. 1965. Children of the Kibbutz. NY: Schocken Books.

- Tarrow, S. 1996. Social movements in contentious politics: A review article. American Political Science Review 90(4): 874-83.

- Tilly, C. 1978. From mobilization to revolution. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- Yishai, Y. 1991. Land of paradoxes: Interest politics in Israel. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Young, J. 1998. The President's Committee on the Handicapped and the origins of cross-disability organizing. Paper presented at the Society for Disability Studies meeting, Oakland, CA.

Endnotes

- The distinction is frequently made in the American context between what Pfeiffer (1988) called rights and services. While there is clearly overlap between the two, and perhaps the amount of overlap differs in different social contexts, they are also still separable analytically.

Return to Text - Event history analysis in social movements is different from the analysis of life event histories, even when applied to participation in social movements, as was done by Kasnitz (2001).

Return to Text - Social movements exist an extended period of time, can use different tactics, and can be conducted by different groups of activists. Social movements commonly fight on many fronts at the same time. Participants may conduct marches, sit-ins, or strikes at the same time they are involved in lawsuits, voter-registration campaigns, and petition drives.

Return to Text - This is one definition that might change the results when applied to other societies. While lobbying or lawsuits are normative political activities in the US, they may not be in other societies-or they may not be when conducted by social stigmatized groups such as people with disabilities. This issue should be analyzed in a larger study of disability movements in many societies.

Return to Text - Thus, not all protests in which people with disabilities take part are included. In the British context, a protest by Stephen Hawking, who has significant disabilities, against the American invasion of Iraq would have been rejected on two grounds: It was not collective, and it was not explicitly linked to people with disabilities. In another context, a protest by athletes at the Special Olympics related to the apartheid situation in South Africa would also not have been included, since it was not a disability-related issue. There was no specific case which was excluded from the Israeli data base because of such issues, however.

Return to Text - The type of disability demand was not always the same as the type of protesters. For example, if the article referred to "protesters in wheelchairs (sic)," even though the issue was related to personal assistance or home health care, the type of disability was not coded to represent the characteristics of the protesters [mobility impairment] but rather to represent the type of demand being made [cross-disability (affecting people with many or most types of disabilities)].

Return to Text - It must be noted that all such coding is being done by an external source (the researcher), not participants. It is possible that participants in the specific actions might disagree with the characterization made by the coding decisions. That limitation must be accepted in the current type of research and must be seen to affect the results. One reason why different research comes to different conclusions is that each methodology has its own premises and those may lead to different conclusions.

Return to Text - Even though not all laws and policies are rights-related, it was not possible to separate them further.

Return to Text - A number of scholars of social movements argue that media reports substantially under-represent the actual number of protests that occur. McCarthy et al. (1996), Mueller (1997), and Snyder and Kelly (1977) argue that newspaper coverage is biased towards more disruptive protests--those that are longer, larger, and more violent.

Return to Text - See Barnartt and Scotch (2000), Tarrow (1996), and Tilly (1978) for further discussion of these definitions.

Return to Text - However, Wolfsfeld, writing about an earlier period, found that only 16 % did (1988: 24).

Return to Text - This protest was a demand for increased money for disability support. It was not a demand for increased civil rights or accessibility. Nor was it a demand for new laws, in part because a new law had been passed in 1998-although only two of the eleven sections had been set to become implemented at that point. See Rimmerman and Herr (2004) and Rimon-Greenspan (2006a, 2006b) for thorough analyses of this protest.

Return to Text - It appears quite clear that the long protest, which was a cross-disability protest, energized the deaf community that had not, by itself, protested before. In the two months following the long protest, there were two protests related to deafness; there was one more in 2005. Unlike the majority of other protests, the deafness protests were about rights and discrimination-although one did also include a money-related demand. Only one was partially successful.

Return to Text - Obviously, the lengths of protests are related to their success, because longer protests are more disruptive and so have more power (Barnartt and Scotch, 2000).

Return to Text - Gal (2001) notes that almost 120,000 receive benefits from the General Disability program compared to about 50,000 whose benefits come from the Disabled Veterans program.

Return to Text